Direct Characterization

Definition of direct characterization.

Direct characterization means the way an author or another character within the story describes or reveals a character, through the use of descriptive adjectives , epithets , or phrases . In other words, direct characterization happens when a writer reveals traits of a character in a straightforward manner, or through comments made by another character involved with him in the storyline.

Direct characterization helps the readers understand the type of character they are going to read about. For instance, in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible , he describes his character John Proctor in this way: “He was the kind of man – powerful of body, even-tempered, and not easily led – who cannot refuse support to partisans without drawing their deepest resentment.”

Examples of Direct Characterization in Literature

Example #1: the most dangerous game (by richard connell).

“The first thing Rainsford’s eyes discerned was the largest man Rainsford had ever seen – a gigantic creature, solidly made and black bearded to the waist. … ” ‘Ivan is an incredibly strong fellow,’ remarked the general, ‘but he has the misfortune to be deaf and dumb. A simple fellow, but, I’m afraid, like all his race, a bit of a savage.’ “

The above passage shows a good example of a direct characterization. Here Zaroff has explicitly described another character Ivan in the story The Most Dangerous Game , leaving readers with no more questions about him. Ivan is a muscular, huge man, having a long black beard. He is deaf and dumb, yet strong, Zaroff says.

Example #2: The Old Man and the Sea (by Earnest Hemingway)

“The old man was thin and gaunt with deep wrinkles in the back of his neck. The brown blotches of the benevolent skin cancer the sun brings from its reflection on the tropic sea were on his cheek … Everything about him was old except his eyes and they were the same color as the sea and were cheerful and undefeated.”

Hemingway uses the method of direct characterization to describe the old man’s personality traits, especially the vivid eyes of his main character, the old man, Santiago in his novel .

Example #3: Hedda Gabler (by Henrik Ibsen)

“MISS JULIANA TESMAN, with her bonnet on a carrying a parasol, comes in from the hall, followed by BERTA, who carries a bouquet wrapped in paper. MISS TESMAN is a comely and pleasant- looking lady of about sixty-five. She is nicely but simply dressed in a grey walking-costume. BERTA is a middle-aged woman of plain and rather countrified appearance…GEORGE TESMAN comes from the right into the inner room … He is a middle-sized, young-looking man … He wears spectacles, and is somewhat carelessly dressed in comfortable indoor clothes.”

In this excerpt, Henrik Ibsen has described three characters: Miss Tesman, Berta, and George Tesman. He has clearly shown their personalities and mannerism through direct characterization.

Example #4: Pride and Prejudice (by Jane Austen)

“Mr. Bingley was good-looking and gentlemanlike; he had a pleasant countenance, and easy, unaffected manners. … he was discovered to be proud, to be above his company, and above being pleased; and not all his large estate in Derbyshire could then save him from having a most forbidding, disagreeable countenance, and being unworthy to be compared with his friend.”

Mr. Bingley, the romantic interest of Jane, and his friend, Mr. Darcey, are described in this excerpt through direct characterization. She has admired Mr. Bingley for his pleasant countenance, comparing him to Mr. Darcy.

Example #5: The Canterbury Tales (by Geoffrey Chaucer)

“He yaf nat of that text a pulled hen, That seith that hunters ben nat hooly men, Ne that a monk, whan he is recchelees… His heed was balled, that shoon as any glas, And eek his face, as he hadde been enoynt. His eyen stepe, and rollynge in his heed, That stemed as a forneys of a leed; His bootes souple, his hors in greet estaat.”

Through monk’s portrait, his physical and social life, readers see a satire of the religious figures that should live a proper monastic life of hard work and deprivation. This is the achievement of the description of Chaucer that he has described a character through direct characterization.

Function of Direct Characterization

Direct characterization shows traits as well as motivation of a character. Motivation can refer to desires, love, hate, or fear of the character. It is a crucial part that makes a story compelling. Descriptions about a character’s behavior, appearance, way of speaking, interests, mannerisms, and other aspects draw the interest of the readers and make the characters seem real. Also, good descriptions develop readers’ strong sense of interest in the story.

Related posts:

- Characterization

- Direct Object

- 10 Best Characterization Examples in Literature

Post navigation

Direct vs indirect characterization: How to show and tell

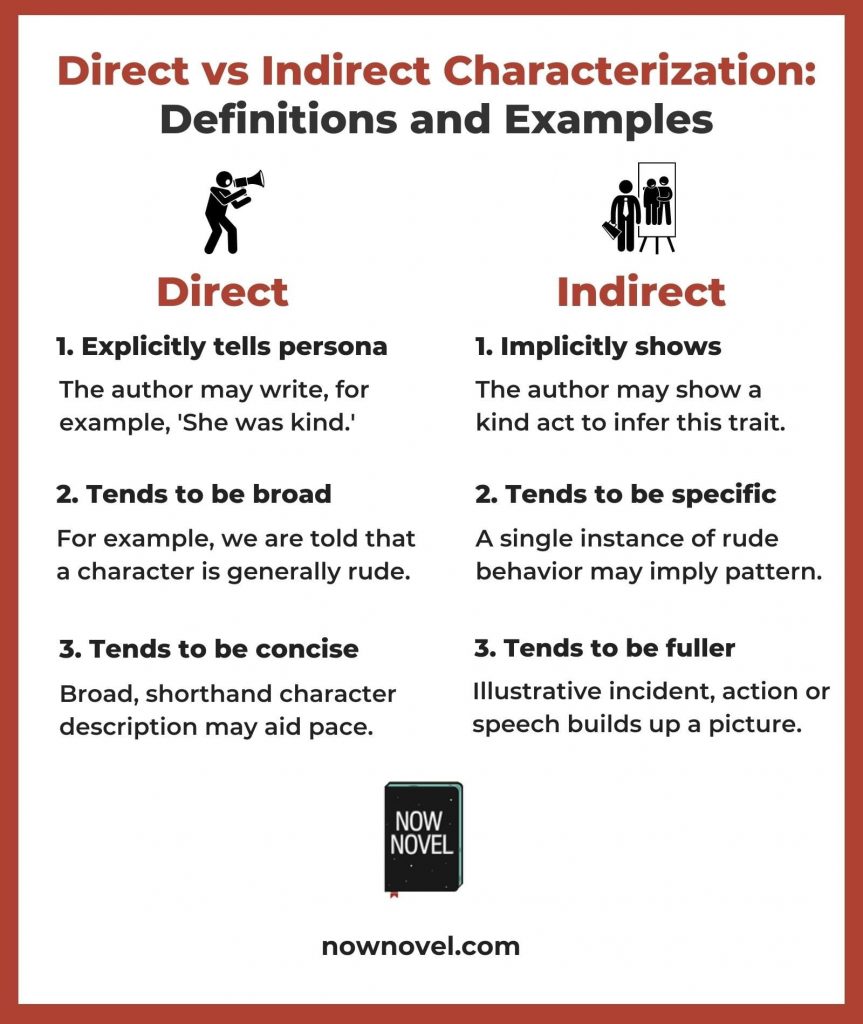

There are two main ways to reveal characters: direct characterization, and indirect characterization. What defines these two characterization types, and what are the strengths and weaknesses of each?

- Post author By Jordan

- 26 Comments on Direct vs indirect characterization: How to show and tell

Characterization describes the way a writer or actor creates or implies a character’s personality, their inner life and psyche. Two main ways to reveal your characters are direct characterization and indirect characterization. What are these character creation techniques? Read on for examples of characterization that illustrate both:

Guide to direct and indirect characterization: Contents

What is direct characterization, direct characterization example, what is indirect characterization, indirect characterization example.

- Eight tips for using direct vs indirect characterization

Let’s delve into using both characterization devices:

To begin with a definition of direct characterization, this means the author explicitly tells the reader a character’s personality .

For example, explicitly telling the reader a character is kind, funny, eccentric, and so forth.

Here’s an example of direct characterization from Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse (1925).

Woolf explicitly shows what characters think of one another . In the example, an artist staying with the Ramsay family, Lily Briscoe, thinks about Mr Ramsay whom a man Mr Bankes has just called a hypocrite:

Looking up, there he was – Mr. Ramsay – advancing towards them, swinging, careless, oblivious, remote. A bit of a hypocrite? she repeated. Oh no – the most sincere of men, the truest (here he was), the best; but, looking down, she thought, he is absorbed in himself, he is tyrannical, he is unjust… Virginia Woolf, To The Lighthouse (1927), p. 52.

This is direct characterization – through Lily, Woolf describes Mr. Ramsay’s traits directly.

It’s telling (direct characterization typically is), but because we read it as one character’s opinion of another, it also shows us how Lily feels, whether or not she agrees with the statement that Mr. Ramsay is a hypocrite.

Through Lily, we learn Ramsay is ‘absorbed in himself’ or self-absorbed, tyrannical – we read direct statements about Ramsay’s personality that help us picture him and how he comes across to others.

‘Indirect characterization’ shows readers your characters’ traits without explicitly describing them.

To give simpler examples of direct vs indirect characterization, for direct you might write, ‘Jessica was a goofy, eccentric teacher’.

For indirect revelation of Jessica’s character, you might write instead, ‘Jessica had named the stick with a hook on the end she used to open the classroom’s high windows Belinda and would regale her children with stories of Belinda’s adventures (even though they were fourteen, not four)’.

In the second example of characterization above (the indirect kind), it is inferred that Jessica is goofy and eccentric. She names inanimate objects and tells teenagers stories of make-believe that would probably be better-suited to younger children.

Indirect characterization invites your reader to deduce things about your characters, without explicitly telling them who they are.

Here, John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath (1939) shows a character’s personality indirectly.

Steinbeck doesn’t say that hitchhiker Joad is a down-and-out, blue-collar worker. Instead, the author creates indirect characterization through the items a worker in this context would perhaps have: whiskey, cigarettes, calloused hands:

Joad took a quick drink from the flask. He dragged the last smoke from his raveling cigarette and then, with callused thumb and forefinger, crushed out the glowing end. He rubbed the butt to a pulp and put it out the window, letting the breeze suck it from his fingers. John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath (1939), p. 9.

Types of indirect characterization

What types of indirect characterization are there?

Any writing that helps us infer or deduce things about a person’s psyche, emotions, values or mannerisms. For example:

- Dialogue-based inference: From the way your character speaks to others in the story, your reader may deduce that they are kind, cruel, gentle, etc.

- Implying through action: What your character does (for example jumping on a beetle to squash it) implies their character (in this case, it may imply that a character is cruel).

- Fly-on-wall description: Although what visual description implies may differ from country to country, culture to culture, neutrally-worded description may cause your reader to make specific assumptions based on what you’ve shown. We might assume, for example, an extremely pale-skinned character is reclusive or agoraphobic, like the reclusive Boo Radley in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird .

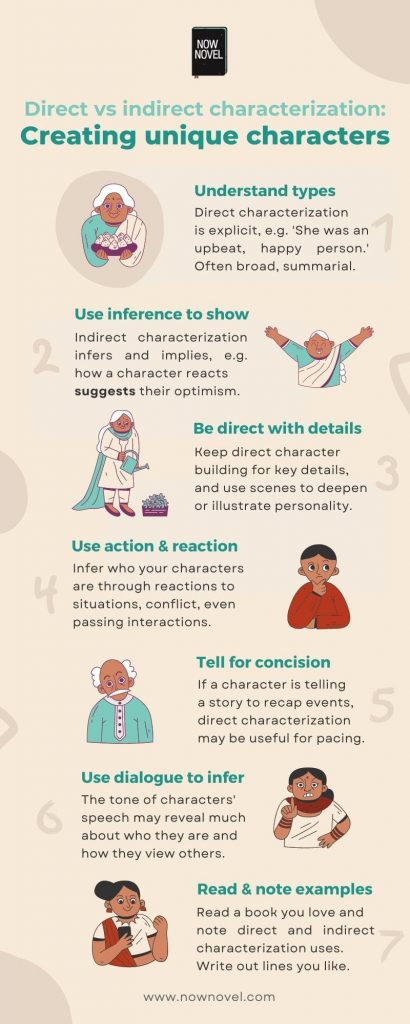

So how do you use direct and indirect characterization well? Read tips for each (and our complete guide to description for more examples):

8 tips for using direct and indirect characterization

Avoid overusing direct characterization, be direct with key details, support direct character statements with scenes, imply character through action and reaction, tell direct details that serve concision, use dialogue to characterize indirectly, let narrative voice give character, read examples of direct and indirect characterization.

Direct characterization is useful shorthand. Instead of pages showing how a character is mean, you could start with ‘He was mean.’ Balance is key, though. Overusing direct characterizing may skew the balance towards telling, not showing. Tweet This

If, for example, you wrote, ‘He was mean. He was petty and generally unkind, so that neighbors crossed the street when he passed,’ that mixes some indirect characterization with the direct type. Neighbors crossing the street is a visual that indirectly implies avoidance and discomfort or possible dislike.

If you were to only tell readers about your characters’ traits without weaving in illustrative showing (which give indirect inference about who your characters are), the effect would be:

- Hazy visuals : Crossing the street in the example above gives a more specific visual than simply saying ‘he was disliked by the community’.

- Lack of depth and color: If you tell your reader who your characters are exclusively with minimal showing or inferring, it may read as though you have a private understanding of your characters you are summarizing for the reader, rather than showing them a fuller, more detailed picture.

Make a Strong Start to your Book

Join Kickstart your Novel and get professional feedback on your first three chapters and story synopsis, plus workbooks and videos.

Example of blending direct and indirect character detail

The opening of Toni Morrison’s powerful novel Beloved characterizes a house that is haunted by the ghost of an infant.

Note how Morrison moves from the direct characterization of the first sentence to specific, visual details:

124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom. The women in the house knew it and so did the children. For years each put up with the spite in his own way, but by 1873 Sethe and her daughter Denver were its only victims. The grandmother, Baby Suggs, was dead, and the sons, Howard and Buglar, had run away by the time they were thirteen years old – as soon as merely looking in a mirror shattered it (that was the signal for Buglar); as soon as two tiny hand prints appeared in the cake (that was it for Howard). Toni Morrison, Beloved (1987), p. 17.

The trick to effective direct characterization is to reserve it for key details you want to establish upfront.

In the example of blending indirect and direct character description above, Morrison starts with direct, broad detail. A sense of spite that drives boys in the family from a home filled with the ghosts of a corrosive, violent history.

If you were to write a retelling of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol you might start with ‘Scrooge was stingy’ and then similar flesh this key detail out with the illustrative, supporting detail.

The indirect characterization you then add on to key details gives further texture, color, specificity to your characters. It helps, of course, to know your characters inside out:

The example above from Beloved shows how indirect characterization supports direct descriptive statements .

The boys Howard and Buglar fleeing from mirrors that seem to shatter by themselves or tiny hand prints appearing in a cake, for example. These specific images and incidents support the suggestion that the home at 124 is haunted by a ‘spiteful’ (or rather, determined-to-be-known) presence.

If you tell your reader a character is kind, think of dedicated scenes as well as passing moments that support the direct revelation.

Maybe your character gives up a seat on public transport for an elderly person. Maybe they help a neighbor get a pet that has run out of an open gate into a busy road to safety.

Indirect characterization is useful because it shows your reader the type of actions your character is likely to take .

This in turn enables your reader to make educated, qualified guesses about how your characters’ might react in situations whose outcome is not yet known. Through this, one ‘gets to know’ characters as though they were real people.

Action and reaction provide useful ways to tell your reader who your characters are indirectly.

For example, Sarah has a vase that belonged to her grandmother that she cherishes, and her hyperactive son knocks it over and breaks it. Does she scold him to be careful? Lash out? Show a mix of anger and understanding?

Think about what you want your reader to infer about a character from the way they react, even in incidents or situations that are trivial or secondary to your story’s main plotline . In this way every scene, every incident, will contribute toward building your characters’ personae.

One of the benefits of direct characterization is that it allows you to be concise.

Direct characterization is useful, for example, when a narrator is recapping prior events that are useful to the present story but not its main focus. For example, in the first page of Nick Hornby’s Slam , a novel about a sixteen-year-old skater named Sam:

So things were ticking along quite nicely. In fact, I’d say that good stuff had been happening pretty solidly for about six months. – For example: Mum got rid of Steve, her rubbish boyfriend. – For example: Mrs Gillet, my art and design teacher, took me to one side after a lesson and asked whether I’d thought of doing art at college. Nick Hornby, Slam (2007), p. 1

At this point in the story, the reader doesn’t need lengthy exposition about why Steve was a rubbish boyfriend. So the direct, telling characterization suits the purpose of this part of the story – catching the reader up on what has been happening in the teenaged protagonist’s life.

There is still balance between indirect and direct characterization in this example. The second example Sam gives tells us (through Mrs Gillet’s action) that the teacher is caring and sees artistic potential in Sam, without saying so explicitly. The part or unique incident suggests the whole of the teacher-student relationship.

Dialogue is a fantastic device for characterization because it may move the story forward while also telling your reader who characters are.

If, for example, there is banter and characters tease each other, it may imply an ease and familiarity (compared to stiff formality between strangers). Note, for example, how Hornby creates a sense of how awkward Rabbit is (an 18-year-old skater at Grind City, a skate park Sam frequents) in the dialogue below:

‘Yo, Sam,’ he said. Did I tell you that my name is sam? Well, now you know. ‘All right?’ ‘How’s it going, man?’ ‘OK.’ ‘Right. Hey, Sam. I know what I was gonna ask you. You know your mum?’ See what I mean about Rabbit being thick? Yes, I told him. I knew my mum. Hornby, pp. 11-12.

In this brief exchange, we see through the awkward, stop-start flow of conversation how Rabbit lacks social graces and awareness and (in the ensuing dialogue) reveals he has a crush on Sam’s mother.

Another useful way to use indirect characterization is to give an involved narrator (a narrator who is also a character in the story) a personality-filled voice .

In the above example of characterization via dialogue, for example, Sam’s asides to the reader (‘Well, now you know’ and ‘See what I mean about Rabbit being thick?’) create the sense of a streetwise, slightly jaded teenaged voice.

Think of ways to inject characters’ personalities into their narration. What subjects do they obsess over (it’s clear Sam loves skating from the first few pages of Slam )? How do they see others (Sam appears fairly dismissive and a little cocky, from referring to his mom’s ‘rubbish’ boyfriend to his blunt description of Rabbit as ‘thick’).

Use language in narration your character would use based on demographic details such as age, cultural background or class identity.

The casual, clipped language Sam uses in the example above suggests the awkward and ‘too cool’ qualities of a teenaged boy.

To really understand the uses of direct and indirect characterization (and how to blend to two to show and tell, describe and imply), look for examples in books.

You could even write out the descriptions you love, to create your own guide to dip into whenever you’re creating characters.

Create believable, developed characters. Finishing a book is easier with structured tools and encouraging support.

Related Posts:

- Indirect characterization: Revealing characters subtly

- Direct characterization: 6 tips for precise description

- Writing advice: Show, don't tell: or should you?

- Tags character description , characterization

Jordan is a writer, editor, community manager and product developer. He received his BA Honours in English Literature and his undergraduate in English Literature and Music from the University of Cape Town.

26 replies on “Direct vs indirect characterization: How to show and tell”

Well explained and helpful

Thank you, Lexi. Thanks for reading!

Thanks for this, I’ve been back a few times now but failed to post a comment. ? This is going to help a lot during this revision!

It’s a pleasure, Robin. Glad you managed in the end. We’ve been migrating our blog to https (more secure) which may have been the cause. Good luck with your revision!

Ah! Okay. Thank you! First books are hard so much to learn. I feel like I could have written two other books while fixings this one. xD (I want to, I enjoy shaping the old chapters to how I write now. ^;^) I also found a program to help speed this up; bibisco. I like it way more than the complicated expensive writing programs out there. IMO.

Where to sign up to get updates for this blog? I don’t want to forget about your blog. (I need reminders for everything. lol. A newsletter is a good way to do that.)

If you sign up for a Now Novel member account, you get subscribed to our blog newsletter too. Alternatively, drop us a line at help at now novel dot com with the email address you’d like to use to get updates and I’ll have our email guy add you to our mailing list. Thanks!

Can you please ,include a section about dynamic and static characters? Thanks for your precious help

Hi Abdou, thank you for the suggestion! I’ll add it to the list for revision ideas, thank you.

You are welcome.

This is such a great website offering very useful tools for writers. I’ve been Googling for days now about everything I wanted to learn in novel writing and I can’t believe I just found this site.

Thanks, Alexa. I’m glad you’ve found our website helpful 🙂

You shared some excellent tips on characterization. I think all writers can benefit from this blog.

Thank you so much, Derrick. I’m glad you’re finding our blog helpful! Thanks for reading.

This is very helpful and I Aced my quiz on something i’m not that good at cool when you lookat the paper it looks long but when you start reading you get lost

Glad you aced your quiz, Kimberly.

Thank You great job!

Thanks, Anna. Thank you for reading our blog!

Very useful.

Thank you so much,

Thank you for your feedback, Aleix. It’s a pleasure, thank you for reading our articles.

Thank you for a clear explanation. It is most useful.

It’s a pleasure, Vivienne. Thank you for reading our blog.

An author employs indirect characterization to avoid explicitly announcing a character’s attributes by revealing those aspects to the reader through the character’s actions, thoughts, and words. Using the phrase “John had a short fuse” as an example would be direct characterisation, but the phrase “John hissed at the man without any prior warning” would be indirect portrayal.

Thank you for sharing your example of indirect and direct characterization and for reading our blog.

[…] is direct characterization is so […]

Thank you for providing this complete reference on direct and indirect characterization. It is often difficult to strike a balance between showing and explaining in writing, and your examples and advice are quite helpful. I really like the focus on utilizing both strategies sparingly, as well as the reminder that indirect characterization may frequently result in a more detailed and compelling picture of characters. I’ll keep these tips in mind as I strive to hone my own writing style.

Thanks so very for your comment. We’re so pleased that you found it helpful. All the best with your writing!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Pin It on Pinterest

Direct Characterization

Definition of direct characterization.

Direct characterization means the way an author or another character within the story describes or reveals a character , through the use of descriptive adjectives, epithets, or phrases. In other words, direct characterization happens when a writer reveals traits of a character in a straightforward manner, or through comments made by another character involved with him in the storyline.

Direct characterization helps the readers understand the type of character they are going to read about. For instance, in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible , he describes his character John Proctor in this way: “He was the kind of man – powerful of body, even-tempered, and not easily led – who cannot refuse support to partisans without drawing their deepest resentment.”

Examples of Direct Characterization in Literature

Example #1: the most dangerous game (by richard connell).

“The first thing Rainsford’s eyes discerned was the largest man Rainsford had ever seen – a gigantic creature, solidly made and black bearded to the waist. … ” ‘Ivan is an incredibly strong fellow,’ remarked the general, ‘but he has the misfortune to be deaf and dumb. A simple fellow, but, I’m afraid, like all his race, a bit of a savage.’ “

The above passage shows a good example of a direct characterization . Here Zaroff has explicitly described another character Ivan in the story The Most Dangerous Game , leaving readers with no more questions about him. Ivan is a muscular, huge man, having a long black beard. He is deaf and dumb, yet strong, Zaroff says.

Example #2: The Old Man and the Sea (by Earnest Hemingway)

“The old man was thin and gaunt with deep wrinkles in the back of his neck. The brown blotches of the benevolent skin cancer the sun brings from its reflection on the tropic sea were on his cheek … Everything about him was old except his eyes and they were the same color as the sea and were cheerful and undefeated.”

Hemingway uses the method of direct characterization to describe the old man’s personality traits, especially the vivid eyes of his main character , the old man, Santiago in his novel.

Example #3: Hedda Gabler (by Henrik Ibsen)

“MISS JULIANA TESMAN, with her bonnet on a carrying a parasol, comes in from the hall, followed by BERTA, who carries a bouquet wrapped in paper. MISS TESMAN is a comely and pleasant- looking lady of about sixty-five. She is nicely but simply dressed in a grey walking-costume. BERTA is a middle-aged woman of plain and rather countrified appearance…GEORGE TESMAN comes from the right into the inner room … He is a middle-sized, young-looking man … He wears spectacles, and is somewhat carelessly dressed in comfortable indoor clothes.”

In this excerpt, Henrik Ibsen has described three characters: Miss Tesman, Berta, and George Tesman. He has clearly shown their personalities and mannerism through direct characterization .

Example #4: Pride and Prejudice (by Jane Austen)

“Mr. Bingley was good-looking and gentlemanlike; he had a pleasant countenance, and easy, unaffected manners. … he was discovered to be proud, to be above his company, and above being pleased; and not all his large estate in Derbyshire could then save him from having a most forbidding, disagreeable countenance, and being unworthy to be compared with his friend.”

Mr. Bingley, the romantic interest of Jane, and his friend, Mr. Darcey, are described in this excerpt through direct characterization . She has admired Mr. Bingley for his pleasant countenance, comparing him to Mr. Darcy.

Example #5: The Canterbury Tales (by Geoffrey Chaucer)

“He yaf nat of that text a pulled hen, That seith that hunters ben nat hooly men, Ne that a monk, whan he is recchelees… His heed was balled, that shoon as any glas, And eek his face, as he hadde been enoynt. His eyen stepe, and rollynge in his heed, That stemed as a forneys of a leed; His bootes souple, his hors in greet estaat.”

Through monk’s portrait, his physical and social life, readers see a satire of the religious figures that should live a proper monastic life of hard work and deprivation. This is the achievement of the description of Chaucer that he has described a character through direct characterization .

Function of Direct Characterization

Direct characterization shows traits as well as motivation of a character . Motivation can refer to desires, love, hate, or fear of the character . It is a crucial part that makes a story compelling. Descriptions about a character ’s behavior, appearance, way of speaking, interests, mannerisms, and other aspects draw the interest of the readers and make the characters seem real. Also, good descriptions develop readers’ strong sense of interest in the story.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 – Characterization

4.1 defining characterization.

Quick Links

The worlds of prose fiction are not only made of events arranged into plots and environments arranged into settings. To have a story, there must also be characters. The arrangement of characters in the story is called characterization . But what are characters? Why are they so necessary for narrative? What kinds of characters do we find in fiction stories? How are they characterized and represented? These are some of the questions that will occupy us in this last chapter dedicated to the formal elements of story .

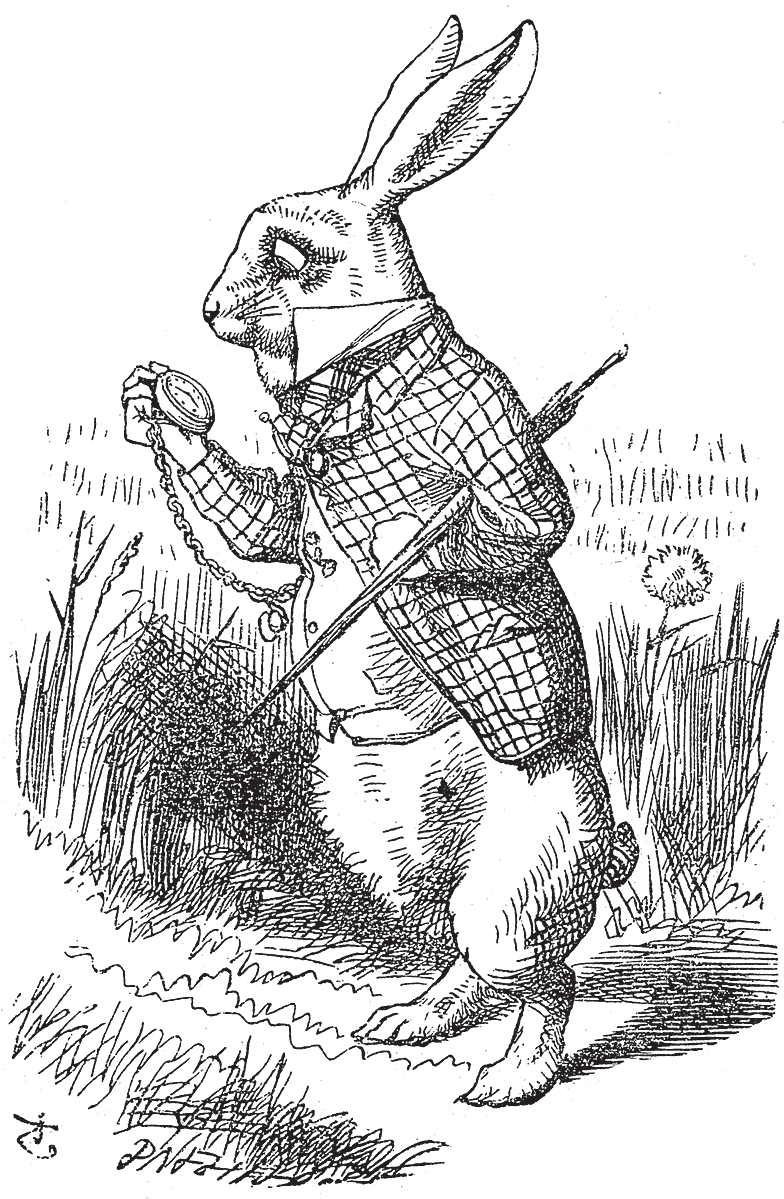

A character is any entity in the story that has agency , that is, who is able to act in the environments of the storyworld. Characters are most often individuals (e.g. Ivan Karamazov in The Brothers Karamazov , Werther in The Sorrows of Young Werther , or Henry Jekyll in Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde ), but there are some special cases where we find collective or choral characters (e.g. Thebans in Oedipus Rex , or the group of neighborhood boys in The Virgin Suicides ). Characters are most often human beings, but they can also be nonhuman animals or other entities who behave like humans (e.g. the White Rabbit in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland — Figure 4.1 — or the robots in I, Robot ).

Ben’s Bonus Bit – Literary Devices

Two related devices are relevant here: personification and dehumanization . Nonhuman characters who effectively function with agency in prose fiction may be said to be ‘personified’ or ‘humanized.’ Abstract forces or ideas may also be personified, such as Lady Liberty, Lady Justice ( lustitia in Latin), or Wisdom’s characterization as a woman in Proverbs 8:1 – 9:12. Whether these figures have agency (and are therefore characters) or whether they serve as symbols varies from text to text. Curious that women are so often dehumanized this way, transformed into abstractions for the admiration, objectification, or condemnation of male audiences 1 .

Personification as a characterization device is distinct from personification that functions as imagery (“The wind howled. Lightning danced across the sky”), which adds life, energy, or personality to setting without granting it true agency. These examples are implied metaphors , as readers understand the wind seems to howl (auditory imagery) and the lightning appears to dance (visual imagery). When writing essays about personification, keep this functional difference in mind: that personification becomes a characterization device only if the object/idea personified may take action in the storyworld.

Similar to dehumanization is zoomorphism , where human characters are given the qualities of animals. Zombies occasionally operate this way in speculative fiction , but we also frequently find zoomorphism and its inverse anthropomorphism in didactic children’s literature ( The Giving Tree , If You Give a Mouse a Cookie , Winnie-the-Pooh , Three Little Pigs , The Ugly Duckling , and so on), folklore (see Brer Rabbit, a Bugs Bunny progenitor in Joel Chandler Harris’ Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings), and in the literature of the Harlem Renaissance (Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man or Richard Wright’s Native Son ). When society treats a racial or ethnic group as less than human, authors often draw attention to that inequity via characterizing devices.

Because of the popularity of folklore and fable, be on the lookout for tricksters and tricksterism whenever zoomorphism or anthropomorphism appear. Besides the animal tricksters from classic cartoons (Bugs Bunny, Wile E Coyote, Woody Woodpecker, Tom & Jerry, and so on), consider that trickster god Loki from Norse mythology transforms into a horse and a wolf, that Reynard in medieval French allegory is an anthropomorphic fox, that Anansi, the Trickster god in Igbo culture, is a spider, that Dionysus, god of wine and madness in Greek mythology, is a shapeshifter, that in Japanese Yōkai folklore, kitsune are intelligent, shape-shifting foxes, and that Māui, a Polynesian trickster figure, is given shape-shifting powers a magic hook Macguffin in Disney’s 2016 film, Moana . There are many other examples. In this way, stories about transgression, transformation, androgyny, rebellion, justice, or disruption of social order often employ anthropomorphism, zoomorphism, or trickster characters.

Rarely are the characters of literary fiction animals or other entities without human features (e.g. the white whale in Moby Dick or the monoliths in 2001: A Space Odyssey ). In our discussion of character, therefore, we will assume that the characters of any story we’re studying are human or human-like individuals, although there are notable exceptions.

That characters are important for narrative fiction can be seen from the fact that the titles of many short stories and novels are taken from the proper names of their main characters ( protagonists ). These are sometimes called eponymous characters and are quite common in the history of literature. Some of the most famous novels are named after their protagonists, such as Don Quixote , Robinson Crusoe , Jane Eyre , Madame Bovary , or Anna Karenina . Even when characters do not appear in the title, they are still the most relevant existents in a great majority of short stories and novels. This seems to be a consequence of the nature and function of narrative. As we saw in the introduction, narrative is fundamentally a way for people to give meaning to our world. And what is more important to us than ourselves and others like us?

Fig. 4.1 Illustration of Lewis Carroll Alice in Wonderland (1865). By John Tenniel, Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia. org/wiki/Alice%27s_Adventures_in_ Wonderland#/media/File:Alice_par_ John_Tenniel_02.png

While recognizing the relevance of characters in narrative, we should not forget the intimate connections between characters and the other two existents of the story, events and environments (see Fig. 3.1, in Chapter 3 ). Stories are not simply made of characters acting in an environment. All the existents of the story are indispensable to the recreation of a convincing storyworld, just as they are in our own lifeworld. Thus, characterization, plot, and setting work together to effectively sustain narrative discourse and contribute to meaningful communication between authors and readers.

In this chapter, we will start by discussing how the nature of characters changes when we analyze them at the level of narrative , discourse , or story . We will then consider the notion of individuation to show that characterization in prose fiction is generally aimed at constructing fully individuated characters, but often also produces typical and universal characters . When analyzing fictional characters in psychological/ realistic terms, it is common to distinguish their degree of individuation ( flat vs. round characters ), as well as their degree of personal development throughout the plot ( static vs. dynamic characters ). After looking at these typologies of character, we will discuss the most common approaches to representing them in narrative: indirect and direct characterization . One vital method of direct characterization is dialogue , which will be the topic of the last section in this chapter.

4.2 The Actants of Narrative

The nature of characters varies depending on what level of the semiotic model we position ourselves in (see Figs. 1.5 and 1.7 in Chapter 1 ). At the level of narrative, characters may be seen as figments of the author , who endows them with certain features or qualities drawn from her imagination or observations, which are then recreated by readers in every reading. At the level of discourse, however, we can see characters as a construct of the text , a sort of ‘paper people’ whose features are exclusively constituted by the descriptions found in the text and the inferences that can be made from textual cues. 2 In this sense, characters are incomplete creatures, mere actants with no life beyond the text and no reason to exist other than to fulfill their function in the plot. 3 Harry Potter, for example, might appear as an almost real individual for many readers, but at the level of discourse he is simply the hero of an adventure story whose ‘life’ does not extend beyond the events narrated in the eponymous novels.

Things look different when we analyze characters as existents of the story. At that level, characters may be seen as individuals who inhabit an alternative world, the storyworld . It is a matter of some debate whether the existence of characters in the alternative world of the story should be regarded as complete or limited to text-based inferences. Here, we will assume that characters are endowed with at least a potentially complete existence in the storyworld. Of course, this existence is ultimately dependent on the narrator of the story (a figure of discourse). But within the confines of the storyworld created by narrative discourse, characters are generally agents endowed with an identity , social and personal relationships, feelings, desires and thoughts, just like any of us in our own lifeworld . Thus, Harry Potter might not be, nor could ever be, a real person in the world of readers. But, in the storyworld created by J. K. Rowling’s novels, he is a heroic and charismatic young wizard, with a multifaceted life, which includes the adventures narrated in the plots of the novels, but also, at least potentially, many other events, big and small, of which we may never hear.

Ben’s Bonus Bit – Fan Fiction, Fandoms, Negotiated Meaning, and Essay Writing

That fictional characters may carry on full lives within the storyworlds created by their authors takes on surprising cultural significance when we consider that a text’s ultimate meaning is negotiated between an author and readers . While authorial intent is a matter of great interest among readers and scholars who pour over an author’s notes, interviews, or drafts for clues about theme or message, fiction is written to be read. Because words are signs (representations) of thoughts or emotions and consist of symbols (letters), they must be translated from page to brain. Interpretive wiggle room exists in that grand game of telephone, as thousands or millions of readers bring their own biases, connotations, worldviews, and backgrounds to any text and then begin discussing, arguing, or appropriating texts for their own purposes.

Because authors cannot anticipate all potential readings (and may have no interest in appealing to wide audiences), readers are largely responsible for a text’s enduring value in society . Shakespeare’s plays, for example, could never be appreciated by modern audiences without real leg-work on the part of readers to interpret the author’s themes, helping his texts move beyond the limitations of the time period in which they were written (archaic language, lost stage directions, or female parts played by men, for example). Modern actors, directors, stage managers, and theater goers may claim real authorship over meaning in any production of Hamlet . Does stage direction of “Gertrude’s Closet” mean our scene occurs in a private room, in her bedroom, or on her bed(!) in Act 3, Scene 4? Is Lawrence Olivia wrong to suggest an Oedipal drive for Hamlet in his influential 1947 portrayal? Sigmund Freud was born nearly 300 years after Shakespeare. We must decide. What clues does the text give us?

When certain storyworlds are especially well constructed (or when they receive marketing support from large publishers) fandoms may arise with significant claim to ownership over the intellectual properties created by individual authors. In this way, Superman or Luke Skywalker or Harry Potter may take on cultural significance that outgrows the intentions, ambitions, or politics of their creators, spawning reams of fan-fiction, non-canonical sequels, and thriving, active fan communities on the Internet. If this happens during an author’s lifetime, struggle is possible between a writer and a fanbase over who controls ultimate meaning in an intellectual property. This is the case with Harry Potter, as JK Rowling’s comments on transgender rights caused significant controversy in June of 2020. For many fans, Potter’s story is about an excluded outsider who finds family and community in his new identity. This remains true despite the author’s individual politics, largely because readers play a vital role in making meaning for the text.

As students of fiction, it is therefore useful to consider meaning within a text as multiplicitous . There is indeed a matrix of plausible meanings within any single text. A specific reading is plausible if it is supported by the preponderance of textual evidence . Author’s biography or cultural studies may also contribute to plausibility, but for students of fiction, finding, reporting, and analyzing textual evidence is key to creating compelling, persuasive essays that advance the critical conversation about a piece. There may not be one, singular, authoritative reading that your essay must uncover, but positioning your argument within the matrix of plausible interpretations requires respect for the text as an authoritative source of information about meaning and a rigorous commitment to providing proof of your claims.

As existents in the storyworld, all characters have in principle the same importance. In J. K. Rowling’s fictional world, to continue with the same example, Harry is not more important than Hermione Granger or Neville Longbottom. But narrative discourse, by arranging events, environments, and characters into a plot, necessarily establishes distinctions amongst the characters, just as it does amongst the events and environments. Thus, Harry Potter becomes more relevant than all the other characters, taking on the role of the main character ( the protagonist or hero) in the story, while the rest appear as secondary characters . Some of these secondary characters, like Hermione or Ron, have a prominent role next to Harry, while many others, like Angelina Johnson or Bertha Jorkins, only appear fleetingly and play minor supporting roles in the plot. A few other characters from this storyworld, like Draco Malfoy or Dolores Umbridge, are cast as antagonists to Harry and his friends in the conflicts that drive the plot of the novels, even if, under a different arrangement of events and environments, they might have been cast in a different role. John Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius , for instance, places Hamlet’s villains in starring roles.

4.3 Individuation

Whether characters are central to the story or only play a secondary role, their characterization generally requires the narrator to directly or indirectly ascribe to them certain characteristics or properties that identify them as individuals. This is what we call individuation . In principle, a primary character will be more individuated than a secondary one. And we can expect the characters that are least relevant for the plot to be also the least individuated. But this rule has, in fact, notable exceptions. It is not uncommon to find secondary characters with characteristics so well defined that they become at least as individuated in the minds of the reader as the protagonist himself, if not more so. In Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness , for example, the elusive ivory trader Kurtz is characterized with more detail and nuance than Marlow, the protagonist of the story.

In general, individuation involves three sets of defining characteristics or traits: 4

- Physical : these are the features of the body, such as whether the character is tall or short, slim or fat, blue-eyed or brown-eyed, fair or dark, male or female, etc. Many physical characteristics are external and can be observed with the naked eye (e.g. the shape of the nose or a scar on the forehead), while others might be internal and thus difficult to perceive directly (e.g. diabetes or heartburn)

- Mental : these are the features of personality or psychology, such as whether the character is modest or arrogant, upbeat or depressive, cruel or kind, dreamy or practical, etc. These traits compose what is commonly understood as the character of a person . They might include traits that are perceptual (e.g. powers of observation), emotive (e.g. excitability), volitional (e.g. ambition), and cognitive (e.g. shrewdness), and

- Behavioral : these are the features of habits, such as whether the character is punctual or habitually tardy, whether she shouts or whispers when speaking, laughs easily or never laughs at all, drinks or avoids alcohol, etc. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish mental and behavioral traits, as they tend to be intimately connected. Behavioral traits may be related to any actions that characters undertake, including communicating and interacting with other characters.

The aim of individuation is to represent characters in such a way that they appear, speak, and act like real individuals. Just as we have verisimilitude in setting , authors often seek individuation in characterization. In the context of psychological or realistic fiction , a fully individuated character should be endowed with a particular set of physical, mental, and behavioral characteristics so as to allow readers to imagine him or her as a person living in the same kind of world in which we all live. William Faulkner in his 1949 Nobel Prize acceptance speech called good writing an exploration of “the human heart in conflict with itself,” which is an apt description for a fully individuated character. Of course, storyworlds might be quite different from our own lifeworld. It is possible, for example, to imagine a storyworld where individuality as we understand it does not exist and all ‘individuals’ are actually clones or genetic replicas of the same organism. In such a context, the notion of individuation would lose most of its sense. This kind of fiction, however, is notably difficult to create, precisely because individuality is such a central assumption in the worldviews of writers and readers.

As long as we stay within the boundaries of mimetic fiction –storyworlds that imitate or are extrapolated from our own world–it makes sense to strive for individuality in characterization. As social animals, we have evolved a set of perceptual and cognitive mechanisms that allow us to identify and distinguish other human individuals from each other. Given the importance of individuality for our own social existence, it is not surprising that our narratives attempt to represent characters as plausible and self-standing individuals, endowing them with a distinctive set of characteristics.

Not all human cultures, however, give the same importance to individuality. We should not forget that modern novels and short stories are largely the products of the individualistic culture that emerged from the European Renaissance (see Chapter 1 ), closely associated with the scientific and industrial revolutions, the expansion of capitalism, and a philosophical conception of the human being as an isolated, autonomous, and self-reflecting individual. In this culture, which has now become globalized, narrative characters that are not fully individuated seem to lack something important , as if not being properly distinguishable from other characters would make them less real. This has not always been the case. In mythical narratives , for example, the characters are not so much individuals as types (e.g. the ‘messenger’) or universals (e.g. the ‘hero’). Both typical and universal characters are still important in modern fiction, although their nature and function has been somewhat modified by the prevailing individualism of modern culture.

Fig. 4.2 Fan art representing Lord Voldemort and Nagini, from the Harry Potter saga, made with charcoal, acrylics and watercolours. By Mademoiselle Ortie aka Elodie Tihange, CC BY 4.0, https:// fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fichier:Lord_ Voldemort.jpg

Typical characters (or simply, types) represent an aspect of humanity or a particular group of humans. For example, characters representing evil in a concentrated and simplified form, like Lord Voldemort (Fig. 4.2), have become common in young adult or popular fiction. While these ‘villains’ might be individuated to a certain extent, they are not so much individuals as types. Many other typical characters, like the ‘mad professor,’ the ‘femme fatale,’ or the ‘wise old man,’ can be found in modern short stories and novels, where they tend to play secondary or supporting roles as stock characters . When types become ingrained in the psychology and culture of a society and start appearing in many different storyworlds, they are said to be archetypes .

In some respects, every character, no matter how well individuated, can be regarded as a type. 5 Even in real life we often perceive other individuals as types (e.g. blue-collar worker, lawyer, businessman, nerd), a simplification that helps us to classify and group people into categories. This is the basis of prejudice and negative bias, but it is also an evolved mechanism to cope with complex social information. Similarly, characters in fiction, even those who have been individuated with care, cannot avoid being cast as types by readers. Emma Bovary, the eponymous protagonist of Gustave Flaubert’s novel Madame Bovary , is one character in realistic fiction who has been characterized with detail and subtlety (see Fig. 4.3). Yet she is often perceived as a typical adulterer, trying to balance the social imperatives of marriage with her romantic longings.

Fig. 4.3 ‘Madame Hessel en robe rouge lisant’ (1905), oil on cardboard. By Édouard Vuillard, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File:%C3%89douard_Vuillard_-_ Madame_Hessel_en_robe_rouge_lisant_ (1905).jpg

Fig. 4.4 ‘Don Quixote and Sancho Panza at a crossroad,’ oil on canvas. By Wilhelm Marstrand (1810–1873), CC0 1.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Wilhelm_Marstrand,_Don_Quixote_og_Sancho_Panza_ved_en_skillevej,_ uden_datering_(efter_1847),_0119NMK,_Nivaagaards_Malerisamling.jpg

There are times when fictional characters transcend their individuality and typicality to attain some form of universality. Universal characters represent a general aspect of humanity or the whole human species. For example, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, the protagonists of Cervantes’ novel, have become a pair of universal characters, representing two fundamental and contrasting attitudes towards life that are generally found in human beings: idealism and materialism (Fig. 4.4). Similarly, in her desperate longing for a more fulfilling and authentic life, Emma Bovary may represent the alienation of all individuals in modern society, torn between reveries of plenitude and the unsatisfactory realities of everyday existence.

4.4 Kinds of Character

Typologies have been proposed to classify and distinguish the kinds of character most often found in fiction. Two of these typologies are still used extensively by critics and writers, even though their psychological assumptions only make them applicable to mimetic, realist fiction, that is, to storyworlds that attempt to imitate or replicate our own lifeworld. 6

The first of these typologies 7 distinguishes characters based on their degree of individuation :

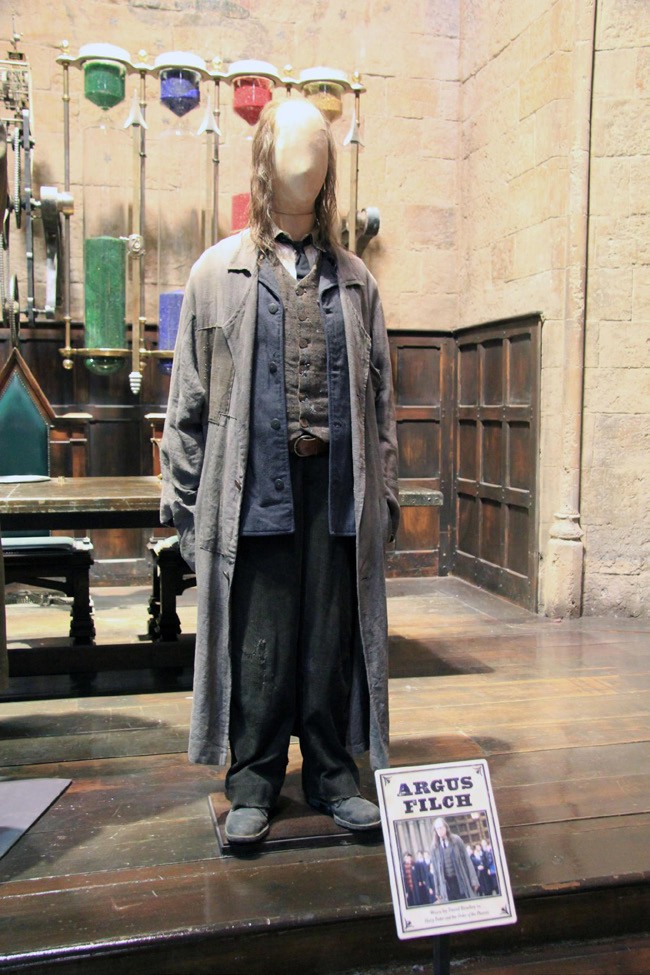

- Flat characters : these characters, which are sometimes equated to what we have called types in the previous section, are constructed around a limited number of traits or characteristics. Of course, there are varying degrees of flatness. At one extreme, we would find characters with a single characteristic or trait, such as a messenger whose only purpose in the story is to deliver a message at a certain point of the plot. Flat characters can be individuated, but their identity, personality, and purpose can often be expressed by a single sentence. They lack depth or complexity and are easily recognizable and remembered by the reader. Because of their limited qualities, however, they also seem artificial, and most readers have a hard time identifying with them or taking them for real human beings. Minor or secondary characters in fiction tend to be flat , even when the main characters in the same story are not. In genres like comedy or adventure , flat characters are quite common. And some writers, like Charles Dickens or H. G. Wells, populate their novels and short stories with flat secondary characters. An example of a flat character from the Harry Potter series is Argus Filch, the caretaker of Hogwarts, characterized almost exclusively by his love for cats and obsession with catching students who break the rules of the school (Fig. 4.5).

Fig. 4.5 Warner Bros. Studio Tour, London: The Making of Harry Potter. Source: Karen Roe, CC BY 2.0, https:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_ Making_of_Harry_Potter_29-05-2012_ (7358054268).jpg

- Round characters : these characters are endowed with many traits or characteristics, some of which might even be contradictory and cause them internal or psychological conflicts . With well-crafted characterization, round characters can appear to be as complex and multifaceted as any human being we might encounter in our world. Major characters in realist prose fiction, such as Emma Bovary, Rodion Raskolnikov, or Anna Karenina, are often round. And there are writers, like Gustave Flaubert or Jane Austen, who tend to characterize even minor characters with such nuance and complexity that they appear to be round, even though they might not have a prominent role in the story. An example of a round character in the Harry Potter novels is Hermione Granger, one of Harry’s closest friends at Hogwarts. While roundness of character is the aim of many realistic and popular stories, in modernist and postmodernist fiction the notion of character has often been questioned. In Robert Musil’s novel The Man Without Qualities , for example, the main character is presented as devoid of any of those stable characteristics, individual or typical, which would allow him to fit comfortably into the preconceived patterns of modern bourgeois society (Fig. 4.6).

Fig. 4.6 ‘Man without Qualities n°2’ (2005), oil and metal on canvas. By Erik Pevernagie, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia. org/wiki/File:Man_without_ Qualities_n%C2%B02.jpg

Another typology, also based on a psychological-realist conception of character and often confused with the previous one, distinguishes characters in terms of their ability to change or evolve throughout the plot:

- Static characters : these characters do not experience any profound change or personal evolution from the moment they appear in the plot until they disappear. Most flat characters are also static, although these classifications are based on different variables. It is possible, although relatively unusual, to have a flat character whose limited characteristics undergo a radical transformation in the story. More common is to have round characters who are static, retaining the same personality, identity, or characteristics throughout the whole narrative. In the Harry Potter novels, for example, most major characters, including Harry, Ron, and Hermione, are fairly static, evolving only superficially from their initial appearance until the end of the series, even if the author has tried to add dynamism into their characterization to take account of their growing into adulthood.

- Dynamic characters : these characters undergo profound and significant changes as the story develops, showing some degree of personal evolution or growth which transforms them at the end of the plot. This evolution is not always positive or constructive, and the changes experienced by the character may involve different forms of crisis, physical or psychological degradation, depression, and other negative or destructive changes. Given their complexity and depth, round characters experience this kind of dynamism, although there are many cases where round characters remain static. In short stories, dynamic characters are far less common than in novels , where the length of the narrative provides more opportunities to show character development and evolution. To continue with examples from the Harry Potter novels, Neville Longbottom is one of the few characters who undergoes a significant evolution throughout the series, as he develops a more confident and bold personality.

4.5 Representing Characters

Like environments, characters in literary narrative need to be represented through words. They cannot be shown directly to the audience, as in film or drama. There are basically two ways to represent characters in prose fiction: 8

- Indirect characterization : The character is presented by the narrator, who describes his or her physical, mental, or behavioral characteristics. Character descriptions are similar to environmental descriptions. They can be long and detailed or short and cursory. And they often rely on significant details that connect characters to the setting, the plot, or even the reader. In certain cases, some details in a character description might be unnecessary or insignificant, but they can serve to make the character seem more realistic. In indirect characterization, the narrator also tends to use commentary to qualify or evaluate the character, providing a subjective interpretation that goes beyond mere description. Indirect characterization has the advantage of conveying a lot of information about characters in a short time . But, as a form of ‘ telling ’ (see Chapter 5 ), it creates some distance between the reader and the character, making the latter less moving and memorable than when direct methods of characterization are used.

- Direct characterization : The character is revealed through actions, words, looks, thoughts, or effects on other characters. Here, the narrator simply records external or internal events related to the character , including words and thoughts, without undertaking a descriptive summary or evaluation of the character’s traits. Direct characterization is, therefore, a form of ‘ showing ’ (see Chapter 5 ). It leaves the reader to interpret the character based on the information provided in the narrative. This kind of characterization is more vivid and effective than the indirect method. But it also asks more from readers , who are required to participate in the construction of characters through their interpretations.

Both forms of characterization are often used in short stories and novels. But direct characterization is generally preferred in modern works of fiction, as it does not require the mediation of an intrusive narrative voice and allows characters to appear more like real people. There are five methods of direct characterization that are commonly used in narrative: speech, thoughts, effects, actions, and looks. These can be easily remembered with the acronym STEAL .

- Speech : what characters say and how they say it is one of the most important components of direct characterization. Verbal language is the fundamental semiotic system that we humans employ to communicate meanings, emotions, intentions, and so on. When it involves an interaction with other people, we call this dialogue. In prose fiction, speech is a widely used method of characterization, as it can be effective in revealing explicit and implicit information about the characters engaged in dialogue. At the same time, speech can serve to move the plot forward and provide information about events, environments, or other characters in the storyworld

- Thoughts : knowing what the characters think (or desire, want, plan, etc.) can also help to define their characteristics. Of course, in our lifeworld, we have no access to what other people think, except when they tell us about it. This is the reason why some modern writers try to avoid this method of characterization, constraining the narrator to represent what can be observed from the outside, but never entering the characters’ minds. However, in many other works of fiction, both classical and modern, readers are allowed access to the thoughts of at least some of the characters, which are necessarily expressed in words, as some form of interior speech or monologue. Modern writers often use more sophisticated techniques like free indirect speech or interior monologue ( stream of consciousness ) to try to convey the complex and fluid mental processes of characters. 9 Molly Bloom’s interior monologue at the end of James Joyce’s Ulysses is perhaps the most famous example of this technique in modern literature

- Effects : how other characters are affected or react to a character can be used to characterize–not just those characters (using speech, thought, or action) but also the character that causes the effect. For example, if the characters surrounding John laugh every time he says or does something, readers will tend to assume that John is either funny or ridiculous. This is an effective characterization technique because it replicates how we judge character in our own life. As social animals, we are always attentive to the impression people make on other people. For instance, we would tend to see as attractive someone at whom others stare with desire or interest, even without knowing what that person looks like

- Actions : what characters do, their behavior, is perhaps the most important method of direct characterization. In general, actions often involve some kind of physical movement (e.g. gesturing, walking, running, etc.), but they can also be passive states (e.g. sleeping, sitting, etc.), or even internal changes reflected in the face or body of the character (e.g. staring, frowning, etc.). Nonverbal communication , which usually accompanies and supports dialogue, is based on actions. Since the characters in fiction are almost always doing something as part of the plot, every action is an opportunity to characterize them in one way or another in the mind of the reader. This is also how we judge each other in life, not only by our words, but also by our deeds, and

- Looks : how a character looks or appears in the story can also be a useful method of direct characterization. Appearance includes the physical traits of the character’s face and body (e.g. eye color, hair length, height, skin complexion, etc.) and their way of dressing or presenting themselves in front of others. Even a character’s choices in decorating a room or a desk may reflect character. In our lifeworld, appearance provides important cues about a person’s social status, occupation, mental and physical state, intentions and thoughts, etc. In prose fiction, looks are often employed to provide the same kind of information, typically through some form of description. In some cases, it can be difficult to distinguish between descriptions that use indirect characterization (presented from the subjective perspective of the narrator) and those that use direct characterization (without any subjective intervention by the narrator).

4.7 Summary

- At the level of discourse, characters are mere actants with no features other than those defined in the text and no reason for being other than their function in the plot. At the level of story, however, we can regard them as existents of the storyworld .

- In realistic, mimetic prose fiction , characterization aims to individuate characters by ascribing to them physical, mental, and behavioral characteristics or properties that distinguish them as individuals.

- Most characters can be classified according to their degree of individuation ( flat vs. round ) or their degree of personal evolution throughout the plot ( static vs. dynamic ).

- The representation of characters in short stories and novels is generally achieved through indirect or direct methods of characterization. Direct methods involve the representation of characters’ speech, thoughts, effects (on other characters), actions , or looks .

- In prose fiction, dialogue (the representation of speech interactions between characters) is usually an important element of the story, contributing both to emplotment and characterization.

Licenses and Attributions:

CC licensed content, Shared previously:

Ignasi Ribó, Prose Fiction: An Introduction to the Semiotics of Narrative. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0187

Version History: Created new verso art. Added quick links. Bolded keywords. Made minor phrasing edits for American audiences. Adopted MLA style for punctuation. Changed paragraphing for PressBooks adaptation. Moved footnotes to endnotes. Added reference to John Updike’s Gertrude and Claudius . Added vocabulary: formal elements of a story, verisimilitude, and young adult fiction. Included “Ben’s Bonus Bits,” with a host of new vocabulary. Included therein references to African American fiction and Rowling’s recent Blog controversy, October, 2021.

Linked bolded keywords to Glossary and improved Alt-image text for accessibility, July, 2022.

- see Paxton, James. “Personification’s Gender.” Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring 1998), pp. 149-179 (31 pages). While there are many examples of ideas embodied in masculine figures (Death, Father Time, Old Man River), in Western literature the balance is tipped firmly in favor of feminine personification. Some of the earliest literary examples (Anger as ‘Ira’ and Greed as ‘Avaritia’ in Prudentius’ medieval allegory Psychomachia ) still speak to sexist stereotypes today.

- Uri Margolin, ‘Character,’ in The Cambridge Companion to Narrative , ed. by David Herman (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 66–79, https://doi. org/10.1017/ccol0521856965

- Algirdas Julien Greimas and Joseph Courtés, Semiotics and Language: An Analytical Dictionary , trans. by Larry Crist and Daniel Patte (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1982), pp. 5–8.

- Uri Margolin, ‘Individuals in Narrative Worlds: An Ontological Perspective,’ Poetics Today , 11:4 (1990), 843–71.

- H. Porter Abbott, The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008), pp. 129–31, https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511816932

- See Seymour Benjamin Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000).

- E. M. Forster, Aspects of the Novel (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985).

- Janet Burroway, Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226616728.001.0001

- Dorrit Cohn, Transparent Minds: Narrative Modes for Presenting Consciousness in Fiction (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988).

- Norman Page, Speech in the English Novel (London, UK: Macmillan, 1988).

- Mikhail M. Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics , ed. by Caryl Emerson (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), p. 6.

- Mikhail M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays , trans. by Michael Holquist and Caryl Emerson (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2011).

Abbott, H. Porter. The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008), https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511816932

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics , ed. by Caryl Emerson (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays , trans. by Michael Holquist and Caryl Emerson (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2011).

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226616728.001.0001

Chatman, Seymour Benjamin. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000).

Cohn, Dorrit. Transparent Minds: Narrative Modes for Presenting Consciousness in Fiction (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988).

Forster, E. M. Aspects of the Novel (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985).

Greimas, Algirdas Julien, and Joseph Courtés. Semiotics and Language: An Analytical Dictionary , trans. by Larry Crist and Daniel Patte (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1982).

Margolin, Uri. ‘Character’, in The Cambridge Companion to Narrative , ed. by David Herman (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 66–79, https://doi.org/10.1017/ccol0521856965

Margolin, Uri. ‘Individuals in Narrative Worlds: An Ontological Perspective,’ Poetics Today , 11:4 (1990), 843–71.

Page, Norman. Speech in the English Novel (London, UK: Macmillan, 1988).

Paxton, James. “Personification’s Gender.” Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring 1998), pp. 149-179.

An entity with agency in a storyworld.

The capacity to act in an environment.

A figure of speech that attributes personal or human characteristics to a nonhuman entity, object, or idea.

Anything that represents something else by virtue of an arbitrary association. In narrative, symbols are existents of the story that become arbitrarily associated with internal or external meanings.

Visually descriptive or figurative language. Despite its association with vision, auditory, tactile, or olfactory imagery also exists but may sometimes be labeled sensory detail.

A figure of speech that establishes a relationship of resemblance between two ideas or things by equating or replacing one with the other.

Related to dehumanization and an inverse to personification, the description of human characters as animals.

A classification of fiction based on moral content. Didactic fiction seeks to teach or enlighten readers.

The main character of a story, the one who struggles to achieve a goal.

A change of state occurring in the storyworld, including actions undertaken by characters and anything that happens to a character or its environment. Also called a “plot point.”

Everything that surrounds the characters in the storyworld.

Semiotic representation of a sequence of events, meaningfully connected by time and cause.

The means through which a narrative is communicated by the implied author to the implied reader.

A complete chronological sequence of interconnected events.

The ascription of mental, physical, or behavioral properties (characteristics) to a character.

A character that represents a particular aspect of humanity or a particular group of humans. (See also Type.)

A character that represents a general aspect of humanity or the whole human species.

Representation of verbal or speech interactions between characters, often accompanied by dialogue or speech tags.

The world of the story, which includes different types of existents (events, environments, and characters).

The figure of discourse that tells the story to a narratee.

The world experienced by writers and readers in their lives.

A character in the story that opposes the protagonist and struggles to frustrate his or her goals.

Features of narrative discourse that attempt to convince readers that the storyworld is a faithful imitation of the ‘real’ world.

The meaningful arrangement or representation of the environments in the story.

Narrative discourse that aims to construct a storyworld that is an accurate reflection of the lifeworld (i.e. the “real” world).

A classification for literature that attempts to mimic the real world. Fiction that seeks verisimilitude.

A character that represents a particular aspect of humanity or a particular group of humans. (See also Typical Character.)

A type that has become part of the psychology and culture of a society and appears in many different storyworlds.

The representation of a story through the mediation of a narrator, who gives an account and often interprets or comments on the events, environments, or characters of the storyworld.

The direct representation of the events, environments, and characters of a story without the intervention (or, in the case of narrative showing, with minimal or limited intervention) of a narrator.

The meaningful arrangement or presentation of the characters of the story.

Narrative indications that often accompany dialogue in prose fiction to provide information about the speakers, the quality and tone of speech, the environment, etc. (See also Speech Tags.)

The inclusion in narrative of a diversity of points of view and voices.

The arrangement of the events of the story into a plot.

Prose Fiction Copyright © by Miranda Rodak and Ben Storey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Dialogue Definition

What is dialogue? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Dialogue is the exchange of spoken words between two or more characters in a book, play, or other written work. In prose writing, lines of dialogue are typically identified by the use of quotation marks and a dialogue tag, such as "she said." In plays, lines of dialogue are preceded by the name of the person speaking. Here's a bit of dialogue from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland : "Oh, you can't help that,' said the Cat: 'we're all mad here. I'm mad. You're mad." "How do you know I'm mad?" said Alice. "You must be,' said the Cat, 'or you wouldn't have come here."

Some additional key details about dialogue:

- Dialogue is defined in contrast to monologue , when only one person is speaking.

- Dialogue is often critical for moving the plot of a story forward, and can be a great way of conveying key information about characters and the plot.

- Dialogue is also a specific and ancient genre of writing, which often takes the form of a philosophical investigation carried out by two people in conversation, as in the works of Plato. This entry, however, deals with dialogue as a narrative element, not as a genre.

How to Pronounce Dialogue

Here's how to pronounce dialogue: dye -uh-log

Dialogue in Depth

Dialogue is used in all forms of writing, from novels to news articles to plays—and even in some poetry. It's a useful tool for exposition (i.e., conveying the key details and background information of a story) as well as characterization (i.e., fleshing out characters to make them seem lifelike and unique).

Dialogue as an Expository Tool

Dialogue is often a crucial expository tool for writers—which is just another way of saying that dialogue can help convey important information to the reader about the characters or the plot without requiring the narrator to state the information directly. For instance:

- In a book with a first person narrator, the narrator might identify themselves outright (as in Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go , which begins "My name is Kathy H. I am thirty-one years old, and I've been a carer now for over eleven years.").

- Tom Buchanan, who had been hovering restlessly about the room, stopped and rested his hand on my shoulder. "What you doing, Nick?”

The above example is just one scenario in which important information might be conveyed indirectly through dialogue, allowing writers to show rather than tell their readers the most important details of the plot.

Expository Dialogue in Plays and Films

Dialogue is an especially important tool for playwrights and screenwriters, because most plays and films rely primarily on a combination of visual storytelling and dialogue to introduce the world of the story and its characters. In plays especially, the most basic information (like time of day) often needs to be conveyed through dialogue, as in the following exchange from Romeo and Juliet :

BENVOLIO Good-morrow, cousin. ROMEO Is the day so young? BENVOLIO But new struck nine. ROMEO Ay me! sad hours seem long.

Here you can see that what in prose writing might have been conveyed with a simple introductory clause like "Early the next morning..." instead has to be conveyed through dialogue.

Dialogue as a Tool for Characterization

In all forms of writing, dialogue can help writers flesh out their characters to make them more lifelike, and give readers a stronger sense of who each character is and where they come from. This can be achieved using a combination of:

- Colloquialisms and slang: Colloquialism is the use of informal words or phrases in writing or speech. This can be used in dialogue to establish that a character is from a particular time, place, or class background. Similarly, slang can be used to associate a character with a particular social group or age group.

- The form the dialogue takes: for instance, multiple books have now been written in the form of text messages between characters—a form which immediately gives readers some hint as to the demographic of the characters in the "dialogue."

- The subject matter: This is the obvious one. What characters talk about can tell readers more about them than how the characters speak. What characters talk about reveals their fears and desires, their virtues and vices, their strengths and their flaws.

For example, in Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen's narrator uses dialogue to introduce Mrs. and Mr. Bennet, their relationship, and their differing attitudes towards arranging marriages for their daughters:

"A single man of large fortune; four or five thousand a year. What a fine thing for our girls!” “How so? How can it affect them?” “My dear Mr. Bennet,” replied his wife, “how can you be so tiresome! You must know that I am thinking of his marrying one of them.” “Is that his design in settling here?” “Design! Nonsense, how can you talk so! But it is very likely that he may fall in love with one of them, and therefore you must visit him as soon as he comes.”

This conversation is an example of the use of dialogue as a tool of characterization , showing readers—without explaining it directly—that Mrs. Bennet is preoccupied with arranging marriages for her daughters, and that Mr. Bennet has a deadpan sense of humor and enjoys teasing his wife.

Recognizing Dialogue in Different Types of Writing

It's important to note that how a writer uses dialogue changes depending on the form in which they're writing, so it's useful to have a basic understanding of the form dialogue takes in prose writing (i.e., fiction and nonfiction) versus the form it takes in plays and screenplays—as well as the different functions it can serve in each. We'll cover that in greater depth in the sections that follow.

Dialogue in Prose

In prose writing, which includes fiction and nonfiction, there are certain grammatical and stylistic conventions governing the use of dialogue within a text. We won't cover all of them in detail here (we'll skip over the placement of commas and such), but here are some of the basic rules for organizing dialogue in prose: