How to write a conclusion for a history essay

Every essay needs to end with a concluding paragraph. It is the last paragraph the marker reads, and this will typically be the last paragraph that you write.

What is a ‘concluding paragraph?

The conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay that reminds the reader about the points you have made and how it proves the argument which you stated in your hypothesis .

By the time your marker reads your conclusion, they have read all the evidence you have presented in your body paragraphs . This is your last opportunity to show that you have proven your points.

While your conclusion will talk about the same points you made in your introduction , it should not read exactly the same. Instead, it should state the same information in a more developed form and bring the essay to an end.

In general, you should never use quotes from sources in your conclusion.

Concluding paragraph structure

While the concluding paragraph will normally be shorter than your introductory and body paragraphs , it still has a specific role to fulfil.

A well-written concluding paragraph has the following three-part structure:

- Restate your key points

- Restate your hypothesis

- Concluding sentence

Each element of this structure is explained further, with examples, below:

1. Restate your key points

In one or two sentences, restate each of the topic sentences from your body paragraphs . This is to remind the marker about how you proved your argument.

This information will be similar to your elaboration sentences in your introduction , but will be much briefer.

Since this is a summary of your entire essay’s argument, you will often want to start your conclusion with a phrase to highlight this. For example: “In conclusion”, “In summary”, “To briefly summarise”, or “Overall”.

Example restatements of key points:

Middle Ages (Year 8 Level)

In conclusion, feudal lords had initially spent vast sums of money on elaborate castle construction projects but ceased to do so as a result of the advances in gunpowder technology which rendered stone defences obsolete.

WWI (Year 9 Level)

To briefly summarise, the initially flood of Australian volunteers were encouraged by imperial propaganda but as a result of the stories harsh battlefield experience which filtered back to the home front, enlistment numbers quickly declined.

Civil Rights (Year 10 Level)

In summary, the efforts of important First Nations leaders and activist organisations to spread the idea of indigenous political equality had a significant effect on sway public opinion in favour of a ‘yes’ vote.

Ancient Rome (Year 11/12 Level)

Overall, the Marian military reforms directly changed Roman political campaigns and the role of public opinion in military command assignments across a variety of Roman societal practices.

2. Restate your hypothesis

This is a single sentence that restates the hypothesis from your introductory paragraph .

Don’t simply copy it word-for-word. It should be restated in a different way, but still clearly saying what you have been arguing for the whole of your essay.

Make it clear to your marker that you are clearly restating you argument by beginning this sentence a phrase to highlight this. For example: “Therefore”, “This proves that”, “Consequently”, or “Ultimately”.

Example restated hypotheses:

Therefore, it is clear that while castles were initially intended to dominate infantry-dominated siege scenarios, they were abandoned in favour of financial investment in canon technologies.

This proves that the change in Australian soldiers' morale during World War One was the consequence of the mass slaughter produced by mass-produced weaponry and combat doctrine.

Consequently, the 1967 Referendum considered a public relations success because of the targeted strategies implemented by Charles Perkins, Faith Bandler and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.

Ultimately, it can be safely argued that Gaius Marius was instrumental in revolutionising the republican political, military and social structures in the 1 st century BC.

3. Concluding sentence

This is the final sentence of your conclusion that provides a final statement about the implications of your arguments for modern understandings of the topic. Alternatively, it could make a statement about what the effect of this historical person or event had on history.

Example concluding sentences:

While these medieval structures fell into disuse centuries ago, they continue to fascinate people to this day.

The implications of the war-weariness produced by these experiences continued to shape opinions about war for the rest of the 20 th century.

Despite this, the Indigenous Peoples had to lobby successive Australian governments for further political equality, which still continues today.

Ancient Rome (Year 11/12 Level)

The impact of these changes effectively prepared the way for other political figures, like Pompey, Julius Caesar and Octavian, who would ultimately transform the Roman republic into an empire.

Putting it all together

Once you have written all three parts of, you should have a completed concluding paragraph. In the examples above, we have shown each part separately. Below you will see the completed paragraphs so that you can appreciate what a conclusion should look like.

Example conclusion paragraphs:

In conclusion, feudal lords had initially spent vast sums of money on elaborate castle construction projects but ceased to do so as a result of the advances in gunpowder technology which rendered stone defences obsolete. Therefore, it is clear that while castles were initially intended to dominate infantry-dominated siege scenarios, they were abandoned in favour of financial investment in canon technologies. While these medieval structures fell into disuse centuries ago, they continue to fascinate people to this day.

To briefly summarise, the initially flood of Australian volunteers were encouraged by imperial propaganda, but as a result of the stories harsh battlefield experience which filtered back to the home front, enlistment numbers quickly declined. This proves that the change in Australian soldiers' morale during World War One was the consequence of the mass slaughter produced by mass-produced weaponry and combat doctrine. The implications of the war-weariness produced by these experiences continued to shape opinions about war for the rest of the 20th century.

In summary, the efforts of important indigenous leaders and activist organisations to spread the idea of indigenous political equality had a significant effect on sway public opinion in favour of a ‘yes’ vote. Consequently, the 1967 Referendum considered a public relations success because of the targeted strategies implemented by Charles Perkins, Faith Bandler and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Despite this, the Indigenous Peoples had to lobby successive Australian governments for further political equality, which still continues today.

Overall, the Marian military reforms directly changed Roman political campaigns and the role of public opinion in military command assignments across a variety of Roman societal practices. Ultimately, it can be safely argued that Gaius Marius was instrumental in revolutionising the republican political, military and social structures in the 1st century BC. The impact of these changes effectively prepared the way for other political figures, like Pompey, Julius Caesar and Octavian, who would ultimately transform the Roman republic into an empire.

Additional resources

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

Introductions & Conclusions

The introduction and conclusion serve important roles in a history paper. They are not simply perfunctory additions in academic writing, but are critical to your task of making a persuasive argument.

A successful introduction will:

- draw your readers in

- culminate in a thesis statement that clearly states your argument

- orient your readers to the key facts they need to know in order to understand your thesis

- lay out a roadmap for the rest of your paper

A successful conclusion will:

- draw your paper together

- reiterate your argument clearly and forcefully

- leave your readers with a lasting impression of why your argument matters or what it brings to light

How to write an effective introduction:

Often students get slowed down in paper-writing because they are not sure how to write the introduction. Do not feel like you have to write your introduction first simply because it is the first section of your paper. You can always come back to it after you write the body of your essay. Whenever you approach your introduction, think of it as having three key parts:

- The opening line

- The middle “stage-setting” section

- The thesis statement

“In a 4-5 page paper, describe the process of nation-building in one Middle Eastern state. What were the particular goals of nation-building? What kinds of strategies did the state employ? What were the results? Be specific in your analysis, and draw on at least one of the scholars of nationalism that we discussed in class.”

Here is an example of a WEAK introduction for this prompt:

“One of the most important tasks the leader of any country faces is how to build a united and strong nation. This has been especially true in the Middle East, where the country of Jordan offers one example of how states in the region approached nation-building. Founded after World War I by the British, Jordan has since been ruled by members of the Hashemite family. To help them face the difficult challenges of founding a new state, they employed various strategies of nation-building.”

Now, here is a REVISED version of that same introduction:

“Since 1921, when the British first created the mandate of Transjordan and installed Abdullah I as its emir, the Hashemite rulers have faced a dual task in nation-building. First, as foreigners to the region, the Hashemites had to establish their legitimacy as Jordan’s rightful leaders. Second, given the arbitrary boundaries of the new nation, the Hashemites had to establish the legitimacy of Jordan itself, binding together the people now called ‘Jordanians.’ To help them address both challenges, the Hashemite leaders crafted a particular narrative of history, what Anthony Smith calls a ‘nationalist mythology.’ By presenting themselves as descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, as leaders of the Arab Revolt, and as the fathers of Jordan’s different tribal groups, they established the authority of their own regime and the authority of the new nation, creating one of the most stable states in the modern Middle East.”

The first draft of the introduction, while a good initial step, is not strong enough to set up a solid, argument-based paper. Here are the key issues:

- This first sentence is too general. From the beginning of your paper, you want to invite your reader into your specific topic, rather than make generalizations that could apply to any nation in any time or place. Students often run into the problem of writing general or vague opening lines, such as, “War has always been one of the greatest tragedies to befall society.” Or, “The Great Depression was one of the most important events in American history.” Avoid statements that are too sweeping or imprecise. Ask yourself if the sentence you have written can apply in any time or place or could apply to any event or person. If the answer is yes, then you need to make your opening line more specific.

- Here is the revised opening line: “Since 1921, when the British first created the mandate of Transjordan and installed Abdullah I as its emir, the Hashemite rulers have faced a dual task in nation-building.”

- This is a stronger opening line because it speaks precisely to the topic at hand. The paper prompt is not asking you to talk about nation-building in general, but nation-building in one specific place.

- This stage-setting section is also too general. Certainly, such background information is critical for the reader to know, but notice that it simply restates much of the information already in the prompt. The question already asks you to pick one example, so your job is not simply to reiterate that information, but to explain what kind of example Jordan presents. You also need to tell your reader why the context you are providing matters.

- Revised stage-setting: “First, as foreigners to the region, the Hashemites had to establish their legitimacy as Jordan’s rightful leaders. Second, given the arbitrary boundaries of the new nation, the Hashemites had to establish the legitimacy of Jordan itself, binding together the people now called ‘Jordanians.’ To help them address both challenges, the Hashemite rulers crafted a particular narrative of history, what Anthony Smith calls a ‘nationalist mythology.’”

- This stage-setting is stronger because it introduces the reader to the problem at hand. Instead of simply saying when and why Jordan was created, the author explains why the manner of Jordan’s creation posed particular challenges to nation-building. It also sets the writer up to address the questions in the prompt, getting at both the purposes of nation-building in Jordan and referencing the scholar of nationalism s/he will be drawing on from class: Anthony Smith.

- This thesis statement restates the prompt rather than answers the question. You need to be specific about what strategies of nation-building Jordan’s leaders used. You also need to assess those strategies, so that you can answer the part of the prompt that asks about the results of nation-building.

- Revised thesis statement: “By presenting themselves as descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, as leaders of the Arab Revolt, and as the fathers of Jordan’s different tribal groups, they established the authority of their regime and the authority of the new nation, creating one of the most stable states in the modern Middle East.”

- It directly answers the question in the prompt. Even though you will be persuading readers of your argument through the evidence you present in the body of your paper, you want to tell them at the outset exactly what you are arguing.

- It discusses the significance of the argument, saying that Jordan created an especially stable state. This helps you answer the question about the results of Jordan’s nation-building project.

- It offers a roadmap for the rest of the paper. The writer knows how to proceed and the reader knows what to expect. The body of the paper will discuss the Hashemite claims “as descendants from the Prophet Muhammad, as leaders of the Arab Revolt, and as the fathers of Jordan’s different tribal groups.”

If you write your introduction first, be sure to revisit it after you have written your entire essay. Because your paper will evolve as you write, you need to go back and make sure that the introduction still sets up your argument and still fits your organizational structure.

How to write an effective conclusion:

Your conclusion serves two main purposes. First, it reiterates your argument in different language than you used in the thesis and body of your paper. Second, it tells your reader why your argument matters. In your conclusion, you want to take a step back and consider briefly the historical implications or significance of your topic. You will not be introducing new information that requires lengthy analysis, but you will be telling your readers what your paper helps bring to light. Perhaps you can connect your paper to a larger theme you have discussed in class, or perhaps you want to pose a new sort of question that your paper elicits. There is no right or wrong “answer” to this part of the conclusion: you are now the “expert” on your topic, and this is your chance to leave your reader with a lasting impression based on what you have learned.

Here is an example of an effective conclusion for the same essay prompt:

“To speak of the nationalist mythology the Hashemites created, however, is not to say that it has gone uncontested. In the 1950s, the Jordanian National Movement unleashed fierce internal opposition to Hashemite rule, crafting an alternative narrative of history in which the Hashemites were mere puppets to Western powers. Various tribes have also reasserted their role in the region’s past, refusing to play the part of “sons” to Hashemite “fathers.” For the Hashemites, maintaining their mythology depends on the same dialectical process that John R. Gillis identified in his investigation of commemorations: a process of both remembering and forgetting. Their myth remembers their descent from the Prophet, their leadership of the Arab Revolt, and the tribes’ shared Arab and Islamic heritage. It forgets, however, the many different histories that Jordanians champion, histories that the Hashemite mythology has never been able to fully reconcile.”

This is an effective conclusion because it moves from the specific argument addressed in the body of the paper to the question of why that argument matters. The writer rephrases the argument by saying, “Their myth remembers their descent from the Prophet, their leadership of the Arab Revolt, and the tribes’ shared Arab and Islamic heritage.” Then, the writer reflects briefly on the larger implications of the argument, showing how Jordan’s nationalist mythology depended on the suppression of other narratives.

Introduction and Conclusion checklist

When revising your introduction and conclusion, check them against the following guidelines:

Does my introduction:

- draw my readers in?

- culminate in a thesis statement that clearly states my argument?

- orient my readers to the key facts they need to know in order to understand my thesis?

- lay out a roadmap for the rest of my paper?

Does my conclusion:

- draw my paper together?

- reiterate my argument clearly and forcefully?

- leave my readers with a lasting impression of why my argument matters or what it brings to light?

Download as PDF

6265 Bunche Hall Box 951473 University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90095-1473 Phone: (310) 825-4601

Other Resources

- UCLA Library

- Faculty Intranet

- Department Forms

- Office 365 Email

- Remote Help

Campus Resources

- Maps, Directions, Parking

- Academic Calendar

- University of California

- Terms of Use

Social Sciences Division Departments

- Aerospace Studies

- African American Studies

- American Indian Studies

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Asian American Studies

- César E. Chávez Department of Chicana & Chicano Studies

- Communication

- Conservation

- Gender Studies

- Military Science

- Naval Science

- Political Science

College of Arts and Sciences

History and American Studies

- What courses will I take as an History major?

- What can I do with my History degree?

- History 485

- History Resources

- What will I learn from my American Studies major?

- What courses will I take as an American Studies major?

- What can I do with my American Studies degree?

- American Studies 485

- For Prospective Students

- Student Research Grants

- Honors and Award Recipients

- Phi Alpha Theta

Alumni Intros

- Internships

Introduction and Conclusion

INTRODUCTIONS The introduction of a paper must introduce its thesis and not just its topic. Readers will lose some—if not much—of what the paper says if the introduction does not prepare them for what is coming (and tell them what to look for and how to evaluate it).

For example, an introduction that says, “The British army fought in the battle of Saratoga” gives the reader virtually no guidance about the paper’s thesis (i.e., what the paper concludes/argues about the British army at Saratoga).

History papers are not mystery novels. Historians WANT and NEED to give away the ending immediately. Their conclusions—presented in the introduction—help the reader better follow/understand their ideas and interpretations.

In other words, an introduction is a MAP that lays out “the trip the author is going to take [readers] on” and thus “lets readers connect any part of the argument with the overall structure. Readers with such a map seldom get confused or lost.”1

Introductions do four things:

attract the ATTENTION of the reader convince the reader that he/she NEEDS TO READ what the author has to say define the paper’s SPECIFIC TOPIC state and explain the paper’s THESIS Writing the introduction: Consider writing the introduction AFTER finishing your paper. By then, you will know what your paper says. You will have thought it through and provided arguments and supporting evidence; therefore, you will know what the reader needs to know—in brief form—in the introduction. (Always think of your initial introduction as “getting started” and as something that “won’t count.” It is for your eyes only; discard it when you know exactly what your paper says.) A common technique is to turn your conclusion into an introduction. It usually reflects what is in the paper—topic, thesis, arguments, evidence—and can be easily adjusted to be a clear and useful introduction.

Some types of introductions:

Quotation Historical overview (provides introduction to topic AND background so that fewer explanations are needed later in paper) Review of literature or a controversy Statistics or startling evidence Anecdote or illustration Question From general to specific OR specific to general Avoid:

“The purpose of this paper is . . .” OR “This paper is about . . . .” First person (e.g., “I will argue that”) Too many questions Dictionary definitions Length: There is no rule other than to be logical. Short papers require short introductions (e.g., a short paragraph); longer ones may require a page or more to provide all that a reader needs. Longer papers require ELABORATION of the thesis; a sentence is not sufficient to prepare the reader for the many pages of arguments and evidence that follow.

CONCLUSIONS Conclusions are the last thing that readers read; they define readers’ final impression of a paper. A flat, boring conclusion means a flat, boring (or, at least, disappointing) paper.

Conclusions should be a climax, not an anti-climax. They do not just restate what has already been said; they interpret, speculate, and provoke thinking.

Some types of conclusions:

Statement of subject’s significance Call for further research Recommendation or speculation Comparison of part to present Anecdote Quotation Questions (with or without answers) Avoid:

“In conclusion”; “finally”; “thus” Additional or new ideas that introduce a new paper First person Length: Again, there is no rule, although too short conclusions should definitely be avoided. Short conclusions leave the reader on the edge of a cliff with no directions on how to get down.

You are the expert – help your reader pull together and appreciate what he/she has read.

____________________________ 1Howard Becker, Writing for Social Scientists (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986).

How have History & American Studies majors built careers after earning their degrees? Learn more by clicking the image above.

Recent Posts

- Fall 2024 Courses

- Fall 2023 Symposium – 12/8 – All Welcome!

- Spring ’24 Course Flyers

- Internship Opportunity – Chesapeake Gateways Ambassador

- Congratulations to our Graduates!

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 21, 2023

- The Poe Museum Internships (Richmond, VA)

- View umwhistory’s profile on Facebook

- View umwhistory’s profile on Twitter

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to conclude an essay | Interactive example

How to Conclude an Essay | Interactive Example

Published on January 24, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay . A strong conclusion aims to:

- Tie together the essay’s main points

- Show why your argument matters

- Leave the reader with a strong impression

Your conclusion should give a sense of closure and completion to your argument, but also show what new questions or possibilities it has opened up.

This conclusion is taken from our annotated essay example , which discusses the history of the Braille system. Hover over each part to see why it’s effective.

Braille paved the way for dramatic cultural changes in the way blind people were treated and the opportunities available to them. Louis Braille’s innovation was to reimagine existing reading systems from a blind perspective, and the success of this invention required sighted teachers to adapt to their students’ reality instead of the other way around. In this sense, Braille helped drive broader social changes in the status of blindness. New accessibility tools provide practical advantages to those who need them, but they can also change the perspectives and attitudes of those who do not.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: return to your thesis, step 2: review your main points, step 3: show why it matters, what shouldn’t go in the conclusion, more examples of essay conclusions, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing an essay conclusion.

To begin your conclusion, signal that the essay is coming to an end by returning to your overall argument.

Don’t just repeat your thesis statement —instead, try to rephrase your argument in a way that shows how it has been developed since the introduction.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Next, remind the reader of the main points that you used to support your argument.

Avoid simply summarizing each paragraph or repeating each point in order; try to bring your points together in a way that makes the connections between them clear. The conclusion is your final chance to show how all the paragraphs of your essay add up to a coherent whole.

To wrap up your conclusion, zoom out to a broader view of the topic and consider the implications of your argument. For example:

- Does it contribute a new understanding of your topic?

- Does it raise new questions for future study?

- Does it lead to practical suggestions or predictions?

- Can it be applied to different contexts?

- Can it be connected to a broader debate or theme?

Whatever your essay is about, the conclusion should aim to emphasize the significance of your argument, whether that’s within your academic subject or in the wider world.

Try to end with a strong, decisive sentence, leaving the reader with a lingering sense of interest in your topic.

The easiest way to improve your conclusion is to eliminate these common mistakes.

Don’t include new evidence

Any evidence or analysis that is essential to supporting your thesis statement should appear in the main body of the essay.

The conclusion might include minor pieces of new information—for example, a sentence or two discussing broader implications, or a quotation that nicely summarizes your central point. But it shouldn’t introduce any major new sources or ideas that need further explanation to understand.

Don’t use “concluding phrases”

Avoid using obvious stock phrases to tell the reader what you’re doing:

- “In conclusion…”

- “To sum up…”

These phrases aren’t forbidden, but they can make your writing sound weak. By returning to your main argument, it will quickly become clear that you are concluding the essay—you shouldn’t have to spell it out.

Don’t undermine your argument

Avoid using apologetic phrases that sound uncertain or confused:

- “This is just one approach among many.”

- “There are good arguments on both sides of this issue.”

- “There is no clear answer to this problem.”

Even if your essay has explored different points of view, your own position should be clear. There may be many possible approaches to the topic, but you want to leave the reader convinced that yours is the best one!

- Argumentative

- Literary analysis

This conclusion is taken from an argumentative essay about the internet’s impact on education. It acknowledges the opposing arguments while taking a clear, decisive position.

The internet has had a major positive impact on the world of education; occasional pitfalls aside, its value is evident in numerous applications. The future of teaching lies in the possibilities the internet opens up for communication, research, and interactivity. As the popularity of distance learning shows, students value the flexibility and accessibility offered by digital education, and educators should fully embrace these advantages. The internet’s dangers, real and imaginary, have been documented exhaustively by skeptics, but the internet is here to stay; it is time to focus seriously on its potential for good.

This conclusion is taken from a short expository essay that explains the invention of the printing press and its effects on European society. It focuses on giving a clear, concise overview of what was covered in the essay.

The invention of the printing press was important not only in terms of its immediate cultural and economic effects, but also in terms of its major impact on politics and religion across Europe. In the century following the invention of the printing press, the relatively stationary intellectual atmosphere of the Middle Ages gave way to the social upheavals of the Reformation and the Renaissance. A single technological innovation had contributed to the total reshaping of the continent.

This conclusion is taken from a literary analysis essay about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein . It summarizes what the essay’s analysis achieved and emphasizes its originality.

By tracing the depiction of Frankenstein through the novel’s three volumes, I have demonstrated how the narrative structure shifts our perception of the character. While the Frankenstein of the first volume is depicted as having innocent intentions, the second and third volumes—first in the creature’s accusatory voice, and then in his own voice—increasingly undermine him, causing him to appear alternately ridiculous and vindictive. Far from the one-dimensional villain he is often taken to be, the character of Frankenstein is compelling because of the dynamic narrative frame in which he is placed. In this frame, Frankenstein’s narrative self-presentation responds to the images of him we see from others’ perspectives. This conclusion sheds new light on the novel, foregrounding Shelley’s unique layering of narrative perspectives and its importance for the depiction of character.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Your essay’s conclusion should contain:

- A rephrased version of your overall thesis

- A brief review of the key points you made in the main body

- An indication of why your argument matters

The conclusion may also reflect on the broader implications of your argument, showing how your ideas could applied to other contexts or debates.

For a stronger conclusion paragraph, avoid including:

- Important evidence or analysis that wasn’t mentioned in the main body

- Generic concluding phrases (e.g. “In conclusion…”)

- Weak statements that undermine your argument (e.g. “There are good points on both sides of this issue.”)

Your conclusion should leave the reader with a strong, decisive impression of your work.

The conclusion paragraph of an essay is usually shorter than the introduction . As a rule, it shouldn’t take up more than 10–15% of the text.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 23). How to Conclude an Essay | Interactive Example. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/conclusion/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, example of a great essay | explanations, tips & tricks, what is your plagiarism score.

How to Write a History Essay, According to a History Professor

Editor & Writer

www.bestcolleges.com is an advertising-supported site. Featured or trusted partner programs and all school search, finder, or match results are for schools that compensate us. This compensation does not influence our school rankings, resource guides, or other editorially-independent information published on this site.

Turn Your Dreams Into Reality

Take our quiz and we'll do the homework for you! Compare your school matches and apply to your top choice today.

- History classes almost always include an essay assignment.

- Focus your paper by asking a historical question and then answering it.

- Your introduction can make or break your essay.

- When in doubt, reach out to your history professor for guidance.

In nearly every history class, you'll need to write an essay . But what if you've never written a history paper? Or what if you're a history major who struggles with essay questions?

I've written over 100 history papers between my undergraduate education and grad school — and I've graded more than 1,500 history essays, supervised over 100 capstone research papers, and sat on more than 10 graduate thesis committees.

Here's my best advice on how to write a history paper.

How to Write a History Essay in 6 Simple Steps

You have the prompt or assignment ready to go, but you're stuck thinking, "How do I start a history essay?" Before you start typing, take a few steps to make the process easier.

Whether you're writing a three-page source analysis or a 15-page research paper , understanding how to start a history essay can set you up for success.

Step 1: Understand the History Paper Format

You may be assigned one of several types of history papers. The most common are persuasive essays and research papers. History professors might also ask you to write an analytical paper focused on a particular source or an essay that reviews secondary sources.

Spend some time reading the assignment. If it's unclear what type of history paper format your professor wants, ask.

Regardless of the type of paper you're writing, it will need an argument. A strong argument can save a mediocre paper — and a weak argument can harm an otherwise solid paper.

Your paper will also need an introduction that sets up the topic and argument, body paragraphs that present your evidence, and a conclusion .

Step 2: Choose a History Paper Topic

If you're lucky, the professor will give you a list of history paper topics for your essay. If not, you'll need to come up with your own.

What's the best way to choose a topic? Start by asking your professor for recommendations. They'll have the best ideas, and doing this can save you a lot of time.

Alternatively, start with your sources. Most history papers require a solid group of primary sources. Decide which sources you want to use and craft a topic around the sources.

Finally, consider starting with a debate. Is there a pressing question your paper can address?

Before continuing, run your topic by your professor for feedback. Most students either choose a topic so broad it could be a doctoral dissertation or so narrow it won't hit the page limit. Your professor can help you craft a focused, successful topic. This step can also save you a ton of time later on.

Step 3: Write Your History Essay Outline

It's time to start writing, right? Not yet. You'll want to create a history essay outline before you jump into the first draft.

You might have learned how to outline an essay back in high school. If that format works for you, use it. I found it easier to draft outlines based on the primary source quotations I planned to incorporate in my paper. As a result, my outlines looked more like a list of quotes, organized roughly into sections.

As you work on your outline, think about your argument. You don't need your finished argument yet — that might wait until revisions. But consider your perspective on the sources and topic.

Jot down general thoughts about the topic, and formulate a central question your paper will answer. This planning step can also help to ensure you aren't leaving out key material.

Step 4: Start Your Rough Draft

It's finally time to start drafting! Some students prefer starting with the body paragraphs of their essay, while others like writing the introduction first. Find what works best for you.

Use your outline to incorporate quotes into the body paragraphs, and make sure you analyze the quotes as well.

When drafting, think of your history essay as a lawyer would a case: The introduction is your opening statement, the body paragraphs are your evidence, and the conclusion is your closing statement.

When writing a conclusion for a history essay, make sure to tie the evidence back to your central argument, or thesis statement .

Don't stress too much about finding the perfect words for your first draft — you'll have time later to polish it during revisions. Some people call this draft the "sloppy copy."

Step 5: Revise, Revise, Revise

Once you have a first draft, begin working on the second draft. Revising your paper will make it much stronger and more engaging to read.

During revisions, look for any errors or incomplete sentences. Track down missing footnotes, and pay attention to your argument and evidence. This is the time to make sure all your body paragraphs have topic sentences and that your paper meets the requirements of the assignment.

If you have time, take a day off from the paper and come back to it with fresh eyes. Then, keep revising.

Step 6: Spend Extra Time on the Introduction

No matter the length of your paper, one paragraph will determine your final grade: the introduction.

The intro sets up the scope of your paper, the central question you'll answer, your approach, and your argument.

In a short paper, the intro might only be a single paragraph. In a longer paper, it's usually several paragraphs. The introduction for my doctoral dissertation, for example, was 28 pages!

Use your introduction wisely. Make a strong statement of your argument. Then, write and rewrite your argument until it's as clear as possible.

If you're struggling, consider this approach: Figure out the central question your paper addresses and write a one-sentence answer to the question. In a typical 3-to-5-page paper, my shortcut argument was to say "X happened because of A, B, and C." Then, use body paragraphs to discuss and analyze A, B, and C.

Tips for Taking Your History Essay to the Next Level

You've gone through every step of how to write a history essay and, somehow, you still have time before the due date. How can you take your essay to the next level? Here are some tips.

- Talk to Your Professor: Each professor looks for something different in papers. Some prioritize the argument, while others want to see engagement with the sources. Ask your professor what elements they prioritize. Also, get feedback on your topic, your argument, or a draft. If your professor will read a draft, take them up on the offer.

- Write a Question — and Answer It: A strong history essay starts with a question. "Why did Rome fall?" "What caused the Protestant Reformation?" "What factors shaped the civil rights movement?" Your question can be broad, but work on narrowing it. Some examples: "What role did the Vandal invasions play in the fall of Rome?" "How did the Lollard movement influence the Reformation?" "How successful was the NAACP legal strategy?"

- Hone Your Argument: In a history paper, the argument is generally about why or how historical events (or historical changes) took place. Your argument should state your answer to a historical question. How do you know if you have a strong argument? A reasonable person should be able to disagree. Your goal is to persuade the reader that your interpretation has the strongest evidence.

- Address Counterarguments: Every argument has holes — and every history paper has counterarguments. Is there evidence that doesn't fit your argument? Address it. Your professor knows the counterarguments, so it's better to address them head-on. Take your typical five-paragraph essay and add a paragraph before the conclusion that addresses these counterarguments.

- Ask Someone to Read Your Essay: If you have time, asking a friend or peer to read your essay can help tremendously, especially when you can ask someone in the class. Ask your reader to point out anything that doesn't make sense, and get feedback on your argument. See whether they notice any counterarguments you don't address. You can later repay the favor by reading one of their papers.

Congratulations — you finished your history essay! When your professor hands back your paper, be sure to read their comments closely. Pay attention to the strengths and weaknesses in your paper. And use this experience to write an even stronger essay next time.

Explore More College Resources

How to write a research paper: 11-step guide.

Ask a Professor: How to Ask for an Extension on a Paper

The value of a history degree.

BestColleges.com is an advertising-supported site. Featured or trusted partner programs and all school search, finder, or match results are for schools that compensate us. This compensation does not influence our school rankings, resource guides, or other editorially-independent information published on this site.

Compare Your School Options

View the most relevant schools for your interests and compare them by tuition, programs, acceptance rate, and other factors important to finding your college home.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a History Essay

Last Updated: December 27, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA . Emily Listmann is a private tutor in San Carlos, California. She has worked as a Social Studies Teacher, Curriculum Coordinator, and an SAT Prep Teacher. She received her MA in Education from the Stanford Graduate School of Education in 2014. There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 242,992 times.

Writing a history essay requires you to include a lot of details and historical information within a given number of words or required pages. It's important to provide all the needed information, but also to present it in a cohesive, intelligent way. Know how to write a history essay that demonstrates your writing skills and your understanding of the material.

Preparing to Write Your Essay

- The key words will often need to be defined at the start of your essay, and will serve as its boundaries. [2] X Research source

- For example, if the question was "To what extent was the First World War a Total War?", the key terms are "First World War", and "Total War".

- Do this before you begin conducting your research to ensure that your reading is closely focussed to the question and you don't waste time.

- Explain: provide an explanation of why something happened or didn't happen.

- Interpret: analyse information within a larger framework to contextualise it.

- Evaluate: present and support a value-judgement.

- Argue: take a clear position on a debate and justify it. [3] X Research source

- Your thesis statement should clearly address the essay prompt and provide supporting arguments. These supporting arguments will become body paragraphs in your essay, where you’ll elaborate and provide concrete evidence. [4] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Your argument may change or become more nuanced as your write your essay, but having a clear thesis statement which you can refer back to is very helpful.

- For example, your summary could be something like "The First World War was a 'total war' because civilian populations were mobilized both in the battlefield and on the home front".

- Pick out some key quotes that make your argument precisely and persuasively. [5] X Research source

- When writing your plan, you should already be thinking about how your essay will flow, and how each point will connect together.

Doing Your Research

- Primary source material refers to any texts, films, pictures, or any other kind of evidence that was produced in the historical period, or by someone who participated in the events of the period, that you are writing about.

- Secondary material is the work by historians or other writers analysing events in the past. The body of historical work on a period or event is known as the historiography.

- It is not unusual to write a literature review or historiographical essay which does not directly draw on primary material.

- Typically a research essay would need significant primary material.

- Start with the core texts in your reading list or course bibliography. Your teacher will have carefully selected these so you should start there.

- Look in footnotes and bibliographies. When you are reading be sure to pay attention to the footnotes and bibliographies which can guide you to further sources a give you a clear picture of the important texts.

- Use the library. If you have access to a library at your school or college, be sure to make the most of it. Search online catalogues and speak to librarians.

- Access online journal databases. If you are in college it is likely that you will have access to academic journals online. These are an excellent and easy to navigate resources.

- Use online sources with discretion. Try using free scholarly databases, like Google Scholar, which offer quality academic sources, but avoid using the non-trustworthy websites that come up when you simply search your topic online.

- Avoid using crowd-sourced sites like Wikipedia as sources. However, you can look at the sources cited on a Wikipedia page and use them instead, if they seem credible.

- Who is the author? Is it written by an academic with a position at a University? Search for the author online.

- Who is the publisher? Is the book published by an established academic press? Look in the cover to check the publisher, if it is published by a University Press that is a good sign.

- If it's an article, where is published? If you are using an article check that it has been published in an academic journal. [8] X Research source

- If the article is online, what is the URL? Government sources with .gov addresses are good sources, as are .edu sites.

- Ask yourself why the author is making this argument. Evaluate the text by placing it into a broader intellectual context. Is it part of a certain tradition in historiography? Is it a response to a particular idea?

- Consider where there are weaknesses and limitations to the argument. Always keep a critical mindset and try to identify areas where you think the argument is overly stretched or the evidence doesn't match the author's claims. [9] X Research source

- Label all your notes with the page numbers and precise bibliographic information on the source.

- If you have a quote but can't remember where you found it, imagine trying to skip back through everything you have read to find that one line.

- If you use something and don't reference it fully you risk plagiarism. [10] X Research source

Writing the Introduction

- For example you could start by saying "In the First World War new technologies and the mass mobilization of populations meant that the war was not fought solely by standing armies".

- This first sentences introduces the topic of your essay in a broad way which you can start focus to in on more.

- This will lead to an outline of the structure of your essay and your argument.

- Here you will explain the particular approach you have taken to the essay.

- For example, if you are using case studies you should explain this and give a brief overview of which case studies you will be using and why.

Writing the Essay

- Try to include a sentence that concludes each paragraph and links it to the next paragraph.

- When you are organising your essay think of each paragraph as addressing one element of the essay question.

- Keeping a close focus like this will also help you avoid drifting away from the topic of the essay and will encourage you to write in precise and concise prose.

- Don't forget to write in the past tense when referring to something that has already happened.

- Don't drop a quote from a primary source into your prose without introducing it and discussing it, and try to avoid long quotations. Use only the quotes that best illustrate your point.

- If you are referring to a secondary source, you can usually summarise in your own words rather than quoting directly.

- Be sure to fully cite anything you refer to, including if you do not quote it directly.

- Think about the first and last sentence in every paragraph and how they connect to the previous and next paragraph.

- Try to avoid beginning paragraphs with simple phrases that make your essay appear more like a list. For example, limit your use of words like: "Additionally", "Moreover", "Furthermore".

- Give an indication of where your essay is going and how you are building on what you have already said. [15] X Research source

- Briefly outline the implications of your argument and it's significance in relation to the historiography, but avoid grand sweeping statements. [16] X Research source

- A conclusion also provides the opportunity to point to areas beyond the scope of your essay where the research could be developed in the future.

Proofreading and Evaluating Your Essay

- Try to cut down any overly long sentences or run-on sentences. Instead, try to write clear and accurate prose and avoid unnecessary words.

- Concentrate on developing a clear, simple and highly readable prose style first before you think about developing your writing further. [17] X Research source

- Reading your essay out load can help you get a clearer picture of awkward phrasing and overly long sentences. [18] X Research source

- When you read through your essay look at each paragraph and ask yourself, "what point this paragraph is making".

- You might have produced a nice piece of narrative writing, but if you are not directly answering the question it is not going to help your grade.

- A bibliography will typically have primary sources first, followed by secondary sources. [19] X Research source

- Double and triple check that you have included all the necessary references in the text. If you forgot to include a reference you risk being reported for plagiarism.

Sample Essay

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.historytoday.com/robert-pearce/how-write-good-history-essay

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/writing-a-good-history-paper

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/thesis_statement_tips.html

- ↑ http://history.rutgers.edu/component/content/article?id=106:writing-historical-essays-a-guide-for-undergraduates

- ↑ https://guides.lib.uw.edu/c.php?g=344285&p=2580599

- ↑ http://www.hamilton.edu/documents/writing-center/WritingGoodHistoryPaper.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/

- ↑ https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/hppi/publications/Writing-History-Essays.pdf

About This Article

To write a history essay, read the essay question carefully and use source materials to research the topic, taking thorough notes as you go. Next, formulate a thesis statement that summarizes your key argument in 1-2 concise sentences and create a structured outline to help you stay on topic. Open with a strong introduction that introduces your thesis, present your argument, and back it up with sourced material. Then, end with a succinct conclusion that restates and summarizes your position! For more tips on creating a thesis statement, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Lea Fernandez

Nov 23, 2017

Did this article help you?

Matthew Sayers

Mar 31, 2019

Millie Jenkerinx

Nov 11, 2017

Oct 18, 2019

Shannon Harper

Mar 9, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

How should I write a conclusion to a history essay?

A conclusion should be a summary of everything you have said previously in your essay. Have a sentence stating your answer to the question, then a sentence summarising each of your points, before reinforcing your answer again.

59134 Views

Related History A Level answers

How do i get the higher marks in an a level history essay, can you help me plan an essay with the title: 'winston churchill's iron curtain speech started the cold war', to what extent was the emergence of the nsdap in germany, 1923-1945, a result of international factors, "evaluate the causes of the korean war.", we're here to help, company information, popular requests, © mytutorweb ltd 2013– 2024.

Internet Safety

Payment Security

How to Write a History Essay with Outline, Tips, Examples and More

Before we get into how to write a history essay, let's first understand what makes one good. Different people might have different ideas, but there are some basic rules that can help you do well in your studies. In this guide, we won't get into any fancy theories. Instead, we'll give you straightforward tips to help you with historical writing. So, if you're ready to sharpen your writing skills, let our history essay writing service explore how to craft an exceptional paper.

What is a History Essay?

A history essay is an academic assignment where we explore and analyze historical events from the past. We dig into historical stories, figures, and ideas to understand their importance and how they've shaped our world today. History essay writing involves researching, thinking critically, and presenting arguments based on evidence.

Moreover, history papers foster the development of writing proficiency and the ability to communicate complex ideas effectively. They also encourage students to engage with primary and secondary sources, enhancing their research skills and deepening their understanding of historical methodology.

History Essay Outline

.png)

The outline is there to guide you in organizing your thoughts and arguments in your essay about history. With a clear outline, you can explore and explain historical events better. Here's how to make one:

Introduction

- Hook: Start with an attention-grabbing opening sentence or anecdote related to your topic.

- Background Information: Provide context on the historical period, event, or theme you'll be discussing.

- Thesis Statement: Present your main argument or viewpoint, outlining the scope and purpose of your history essay.

Body paragraph 1: Introduction to the Historical Context

- Provide background information on the historical context of your topic.

- Highlight key events, figures, or developments leading up to the main focus of your history essay.

Body paragraphs 2-4 (or more): Main Arguments and Supporting Evidence

- Each paragraph should focus on a specific argument or aspect of your thesis.

- Present evidence from primary and secondary sources to support each argument.

- Analyze the significance of the evidence and its relevance to your history paper thesis.

Counterarguments (optional)

- Address potential counterarguments or alternative perspectives on your topic.

- Refute opposing viewpoints with evidence and logical reasoning.

- Summary of Main Points: Recap the main arguments presented in the body paragraphs.

- Restate Thesis: Reinforce your thesis statement, emphasizing its significance in light of the evidence presented.

- Reflection: Reflect on the broader implications of your arguments for understanding history.

- Closing Thought: End your history paper with a thought-provoking statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

References/bibliography

- List all sources used in your research, formatted according to the citation style required by your instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago).

- Include both primary and secondary sources, arranged alphabetically by the author's last name.

Notes (if applicable)

- Include footnotes or endnotes to provide additional explanations, citations, or commentary on specific points within your history essay.

History Essay Format

Adhering to a specific format is crucial for clarity, coherence, and academic integrity. Here are the key components of a typical history essay format:

Font and Size

- Use a legible font such as Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri.

- The recommended font size is usually 12 points. However, check your instructor's guidelines, as they may specify a different size.

- Set 1-inch margins on all sides of the page.

- Double-space the entire essay, including the title, headings, body paragraphs, and references.

- Avoid extra spacing between paragraphs unless specified otherwise.

- Align text to the left margin; avoid justifying the text or using a centered alignment.

Title Page (if required):

- If your instructor requires a title page, include the essay title, your name, the course title, the instructor's name, and the date.

- Center-align this information vertically and horizontally on the page.

- Include a header on each page (excluding the title page if applicable) with your last name and the page number, flush right.

- Some instructors may require a shortened title in the header, usually in all capital letters.

- Center-align the essay title at the top of the first page (if a title page is not required).

- Use standard capitalization (capitalize the first letter of each major word).

- Avoid underlining, italicizing, or bolding the title unless necessary for emphasis.

Paragraph Indentation:

- Indent the first line of each paragraph by 0.5 inches or use the tab key.

- Do not insert extra spaces between paragraphs unless instructed otherwise.

Citations and References:

- Follow the citation style specified by your instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago).

- Include in-text citations whenever you use information or ideas from external sources.

- Provide a bibliography or list of references at the end of your history essay, formatted according to the citation style guidelines.

- Typically, history essays range from 1000 to 2500 words, but this can vary depending on the assignment.

How to Write a History Essay?

Historical writing can be an exciting journey through time, but it requires careful planning and organization. In this section, we'll break down the process into simple steps to help you craft a compelling and well-structured history paper.

Analyze the Question

Before diving headfirst into writing, take a moment to dissect the essay question. Read it carefully, and then read it again. You want to get to the core of what it's asking. Look out for keywords that indicate what aspects of the topic you need to focus on. If you're unsure about anything, don't hesitate to ask your instructor for clarification. Remember, understanding how to start a history essay is half the battle won!

Now, let's break this step down:

- Read the question carefully and identify keywords or phrases.

- Consider what the question is asking you to do – are you being asked to analyze, compare, contrast, or evaluate?

- Pay attention to any specific instructions or requirements provided in the question.

- Take note of the time period or historical events mentioned in the question – this will give you a clue about the scope of your history essay.

Develop a Strategy

With a clear understanding of the essay question, it's time to map out your approach. Here's how to develop your historical writing strategy:

- Brainstorm ideas : Take a moment to jot down any initial thoughts or ideas that come to mind in response to the history paper question. This can help you generate a list of potential arguments, themes, or points you want to explore in your history essay.

- Create an outline : Once you have a list of ideas, organize them into a logical structure. Start with a clear introduction that introduces your topic and presents your thesis statement – the main argument or point you'll be making in your history essay. Then, outline the key points or arguments you'll be discussing in each paragraph of the body, making sure they relate back to your thesis. Finally, plan a conclusion that summarizes your main points and reinforces your history paper thesis.

- Research : Before diving into writing, gather evidence to support your arguments. Use reputable sources such as books, academic journals, and primary documents to gather historical evidence and examples. Take notes as you research, making sure to record the source of each piece of information for proper citation later on.

- Consider counterarguments : Anticipate potential counterarguments to your history paper thesis and think about how you'll address them in your essay. Acknowledging opposing viewpoints and refuting them strengthens your argument and demonstrates critical thinking.

- Set realistic goals : Be realistic about the scope of your history essay and the time you have available to complete it. Break down your writing process into manageable tasks, such as researching, drafting, and revising, and set deadlines for each stage to stay on track.

Start Your Research

Now that you've grasped the history essay topic and outlined your approach, it's time to dive into research. Here's how to start:

- Ask questions : What do you need to know? What are the key points to explore further? Write down your inquiries to guide your research.

- Explore diverse sources : Look beyond textbooks. Check academic journals, reliable websites, and primary sources like documents or artifacts.

- Consider perspectives : Think about different viewpoints on your topic. How have historians analyzed it? Are there controversies or differing interpretations?

- Take organized notes : Summarize key points, jot down quotes, and record your thoughts and questions. Stay organized using spreadsheets or note-taking apps.

- Evaluate sources : Consider the credibility and bias of each source. Are they peer-reviewed? Do they represent a particular viewpoint?

Establish a Viewpoint

By establishing a clear viewpoint and supporting arguments, you'll lay the foundation for your compelling historical writing:

- Review your research : Reflect on the information gathered. What patterns or themes emerge? Which perspectives resonate with you?

- Formulate a thesis statement : Based on your research, develop a clear and concise thesis that states your argument or interpretation of the topic.

- Consider counterarguments : Anticipate objections to your history paper thesis. Are there alternative viewpoints or evidence that you need to address?

- Craft supporting arguments : Outline the main points that support your thesis. Use evidence from your research to strengthen your arguments.

- Stay flexible : Be open to adjusting your viewpoint as you continue writing and researching. New information may challenge or refine your initial ideas.

Structure Your Essay

Now that you've delved into the depths of researching historical events and established your viewpoint, it's time to craft the skeleton of your essay: its structure. Think of your history essay outline as constructing a sturdy bridge between your ideas and your reader's understanding. How will you lead them from point A to point Z? Will you follow a chronological path through history or perhaps dissect themes that span across time periods?

And don't forget about the importance of your introduction and conclusion—are they framing your narrative effectively, enticing your audience to read your paper, and leaving them with lingering thoughts long after they've turned the final page? So, as you lay the bricks of your history essay's architecture, ask yourself: How can I best lead my audience through the maze of time and thought, leaving them enlightened and enriched on the other side?

Create an Engaging Introduction

Creating an engaging introduction is crucial for capturing your reader's interest right from the start. But how do you do it? Think about what makes your topic fascinating. Is there a surprising fact or a compelling story you can share? Maybe you could ask a thought-provoking question that gets people thinking. Consider why your topic matters—what lessons can we learn from history?

Also, remember to explain what your history essay will be about and why it's worth reading. What will grab your reader's attention and make them want to learn more? How can you make your essay relevant and intriguing right from the beginning?

Develop Coherent Paragraphs

Once you've established your introduction, the next step is to develop coherent paragraphs that effectively communicate your ideas. Each paragraph should focus on one main point or argument, supported by evidence or examples from your research. Start by introducing the main idea in a topic sentence, then provide supporting details or evidence to reinforce your point.

Make sure to use transition words and phrases to guide your reader smoothly from one idea to the next, creating a logical flow throughout your history essay. Additionally, consider the organization of your paragraphs—is there a clear progression of ideas that builds upon each other? Are your paragraphs unified around a central theme or argument?

Conclude Effectively

Concluding your history essay effectively is just as important as starting it off strong. In your conclusion, you want to wrap up your main points while leaving a lasting impression on your reader. Begin by summarizing the key points you've made throughout your history essay, reminding your reader of the main arguments and insights you've presented.

Then, consider the broader significance of your topic—what implications does it have for our understanding of history or for the world today? You might also want to reflect on any unanswered questions or areas for further exploration. Finally, end with a thought-provoking statement or a call to action that encourages your reader to continue thinking about the topic long after they've finished reading.

Reference Your Sources

Referencing your sources is essential for maintaining the integrity of your history essay and giving credit to the scholars and researchers who have contributed to your understanding of the topic. Depending on the citation style required (such as MLA, APA, or Chicago), you'll need to format your references accordingly. Start by compiling a list of all the sources you've consulted, including books, articles, websites, and any other materials used in your research.

Then, as you write your history essay, make sure to properly cite each source whenever you use information or ideas that are not your own. This includes direct quotations, paraphrases, and summaries. Remember to include all necessary information for each source, such as author names, publication dates, and page numbers, as required by your chosen citation style.

Review and Ask for Advice

As you near the completion of your history essay writing, it's crucial to take a step back and review your work with a critical eye. Reflect on the clarity and coherence of your arguments—are they logically organized and effectively supported by evidence? Consider the strength of your introduction and conclusion—do they effectively capture the reader's attention and leave a lasting impression? Take the time to carefully proofread your history essay for any grammatical errors or typos that may detract from your overall message.

Furthermore, seeking advice from peers, mentors, or instructors can provide valuable insights and help identify areas for improvement. Consider sharing your essay with someone whose feedback you trust and respect, and be open to constructive criticism. Ask specific questions about areas you're unsure about or where you feel your history essay may be lacking.

History Essay Example

In this section, we offer an example of a history essay examining the impact of the Industrial Revolution on society. This essay demonstrates how historical analysis and critical thinking are applied in academic writing. By exploring this specific event, you can observe how historical evidence is used to build a cohesive argument and draw meaningful conclusions.

FAQs about History Essay Writing

How to write a history essay introduction, how to write a conclusion for a history essay, how to write a good history essay.

- Plagiarism Report

- Unlimited Revisions

- 24/7 Support

How to Write a History Essay?

04 August, 2020

10 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

There are so many types of essays. It can be hard to know where to start. History papers aren’t just limited to history classes. These tasks can be assigned to examine any important historical event or a person. While they’re more common in history classes, you can find this type of assignment in sociology or political science course syllabus, or just get a history essay task for your scholarship. This is Handmadewriting History Essay Guide - let's start!

Purpose of a History Essay

Wondering how to write a history essay? First of all, it helps to understand its purpose. Secondly, this essay aims to examine the influences that lead to a historical event. Thirdly, it can explore the importance of an individual’s impact on history.

However, the goal isn’t to stay in the past. Specifically, a well-written history essay should discuss the relevance of the event or person to the “now”. After finishing this essay, a reader should have a fuller understanding of the lasting impact of an event or individual.

Need basic essay guidance? Find out what is an essay with this 101 essay guide: What is an Essay?

Elements for Success

Indeed, understanding how to write a history essay is crucial in creating a successful paper. Notably, these essays should never only outline successful historic events or list an individual’s achievements. Instead, they should focus on examining questions beginning with what , how , and why . Here’s a pro tip in how to write a history essay: brainstorm questions. Once you’ve got questions, you have an excellent starting point.

Preparing to Write

Evidently, a typical history essay format requires the writer to provide background on the event or person, examine major influences, and discuss the importance of the forces both then and now. In addition, when preparing to write, it’s helpful to organize the information you need to research into questions. For example:

- Who were the major contributors to this event?

- Who opposed or fought against this event?

- Who gained or lost from this event?

- Who benefits from this event today?

- What factors led up to this event?

- What changes occurred because of this event?

- What lasting impacts occurred locally, nationally, globally due to this event?

- What lessons (if any) were learned?

- Why did this event occur?

- Why did certain populations support it?

- Why did certain populations oppose it?

These questions exist as samples. Therefore, generate questions specific to your topic. Once you have a list of questions, it’s time to evaluate them.

Evaluating the Question

Seasoned writers approach writing history by examining the historic event or individual. Specifically, the goal is to assess the impact then and now. Accordingly, the writer needs to evaluate the importance of the main essay guiding the paper. For example, if the essay’s topic is the rise of American prohibition, a proper question may be “How did societal factors influence the rise of American prohibition during the 1920s? ”

This question is open-ended since it allows for insightful analysis, and limits the research to societal factors. Additionally, work to identify key terms in the question. In the example, key terms would be “societal factors” and “prohibition”.

Summarizing the Argument

The argument should answer the question. Use the thesis statement to clarify the argument and outline how you plan to make your case. In other words. the thesis should be sharp, clear, and multi-faceted. Consider the following tips when summarizing the case:

- The thesis should be a single sentence

- It should include a concise argument and a roadmap

- It’s always okay to revise the thesis as the paper develops

- Conduct a bit of research to ensure you have enough support for the ideas within the paper

Outlining a History Essay Plan

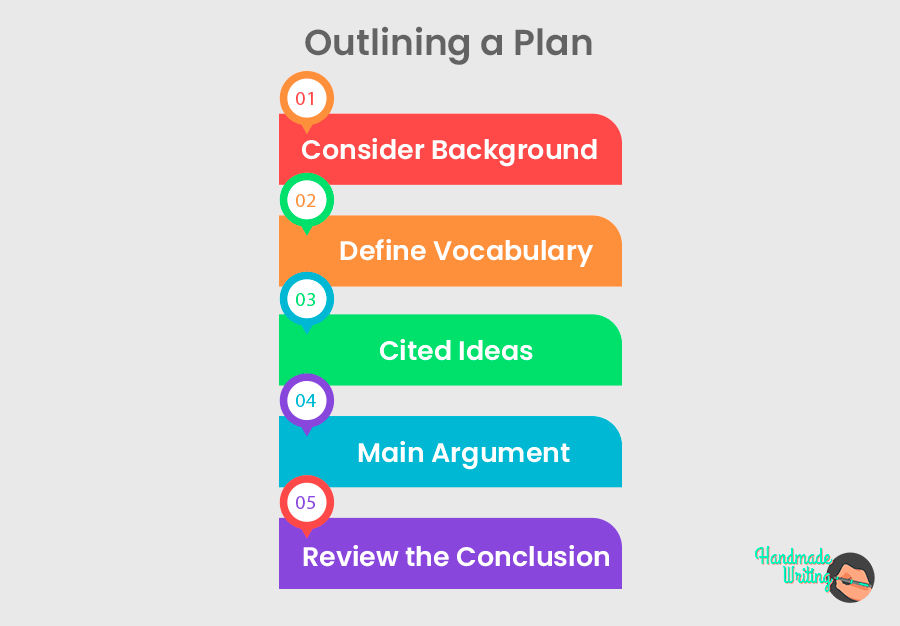

Once you’ve refined your argument, it’s time to outline. Notably, many skip this step to regret it then. Nonetheless, the outline is a map that shows where you need to arrive historically and when. Specifically, taking the time to plan, placing the strongest argument last, and identifying your sources of research is a good use of time. When you’re ready to outline, do the following:

- Consider the necessary background the reader should know in the introduction paragraph

- Define any important terms and vocabulary

- Determine which ideas will need the cited support

- Identify how each idea supports the main argument

- Brainstorm key points to review in the conclusion

Gathering Sources

As a rule, history essays require both primary and secondary sources . Primary resources are those that were created during the historical period being analyzed. Secondary resources are those created by historians and scholars about the topic. It’s a good idea to know if the professor requires a specific number of sources, and what kind he or she prefers. Specifically, most tutors prefer primary over secondary sources.

Where to find sources? Great question! Check out bibliographies included in required class readings. In addition, ask a campus Librarian. Peruse online journal databases; In addition, most colleges provide students with free access. When in doubt, make an appointment and ask the professor for guidance.

Writing the Essay

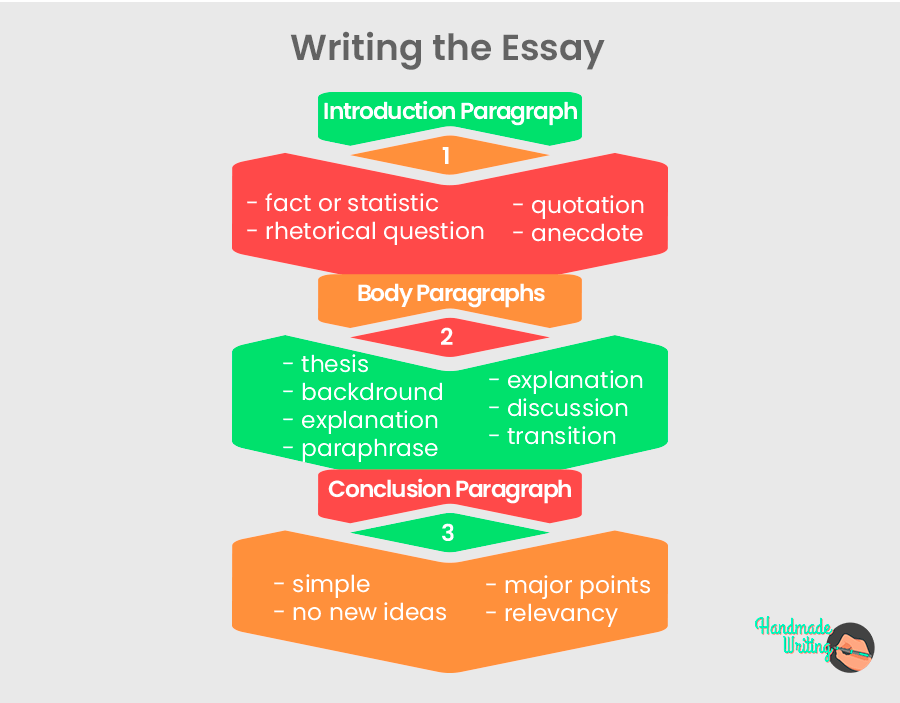

Now that you have prepared your questions, ideas, and arguments; composed the outline ; and gathered sources – it’s time to write your first draft. In particular, each section of your history essay must serve its purpose. Here is what you should include in essay paragraphs.

Introduction Paragraph

Unsure of how to start a history essay? Well, like most essays, the introduction should include an attention-getter (or hook):

- Relevant fact or statistic

- Rhetorical Question

- Interesting quotation

- Application anecdote if appropriate