Subscriber Only Resources

Access this article and hundreds more like it with a subscription to The New York TImes Upfront magazine.

LESSON PLAN

The vietnam war.

Pairing a Primary & Secondary Source

Read the Article

Fifty years ago, the U.S. ended direct military involvement in a war that tore the nation apart and fueled distrust in government.

Before reading.

1. Set Focus Pose these essential questions: Why do countries go to war? How do wars affect countries?

2. List Vocabulary Share some of the challenging vocabulary words in the article (see below) . Encourage students to use context to infer meanings as they read.

- protracted (p. 18)

- ideologies (p. 18)

- disillusioned (p. 19)

- conscripted (p. 20)

- stalemate (p. 20)

- reconciliation (p. 21)

3. Engage Have students examine the map on page 18. Ask: What did the demilitarized zone divide? Why do you think Vietnam divided into North and South Vietnam? Why do you think the two Vietnams reunified? Why do you think what used to be called Saigon is now called Ho Chi Minh City? Explain that the article answers these questions.

Analyze the Article

4. Read and Discuss Ask students to read the Upfront article about the Vietnam War. Review why the article is a secondary source. (It was written by someone who didn’t personally experience or witness the events.) Then pose these critical-thinking questions and ask students to cite text evidence when answering them:

- Which central ideas does the author introduce in the first section? Which of these ideas is developed in the first few paragraphs of the next section, “Fighting Communism”? (In the first section, the author introduces the ideas that the U.S. had been involved in Vietnam for nearly 20 years, that the involvement had turned into a war, that both North Vietnam and the U.S. were looking to end the war, and that the war had become very unpopular with Americans. The next section explains how U.S. involvement in Vietnam began.)

- What is the connection between the Cold War and the Vietnam War? (The Cold War was a conflict between the democracies of the West and the Communist nations led by the Soviet Union to spread their ideologies. President Dwight D. Eisenhower feared that if South Vietnam fell to Communist North Vietnam, then there would be a domino effect of Communist regimes taking control of the Asian continent. So he sent U.S. advisory troops to support South Vietnamese soldiers. Later presidents increased involvement.)

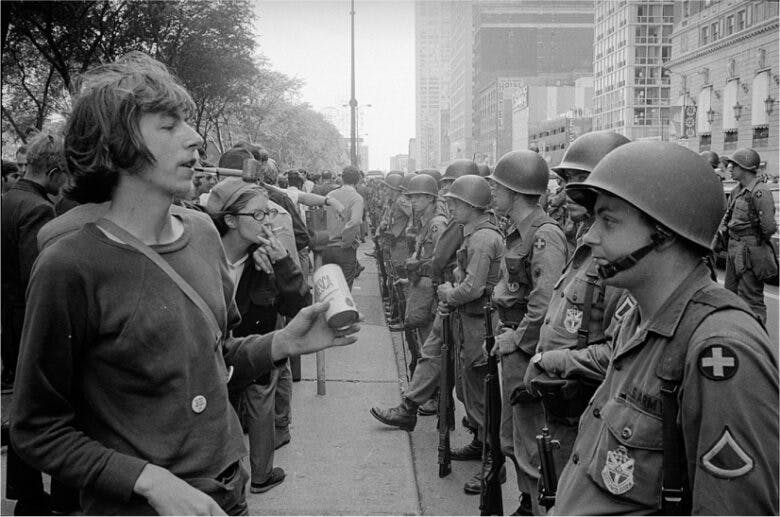

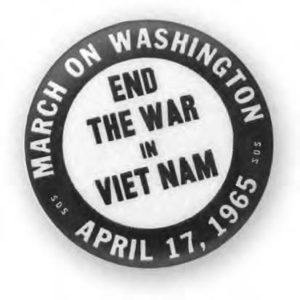

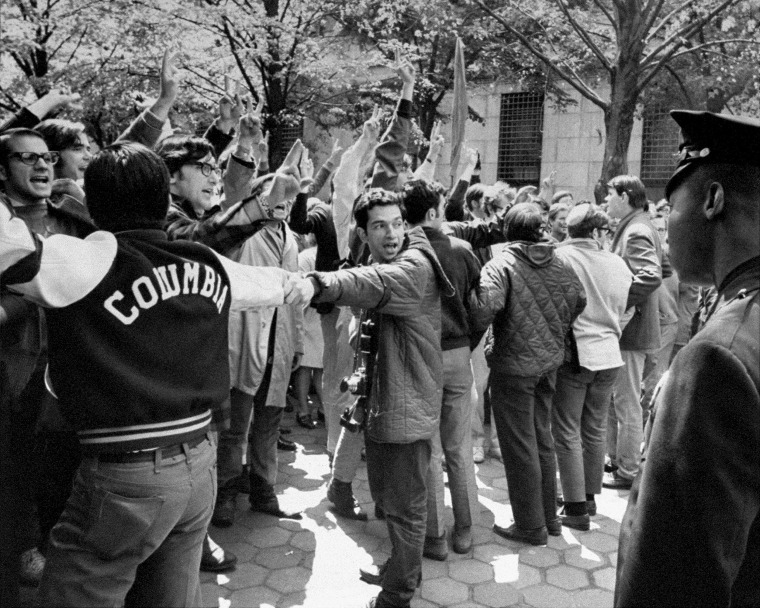

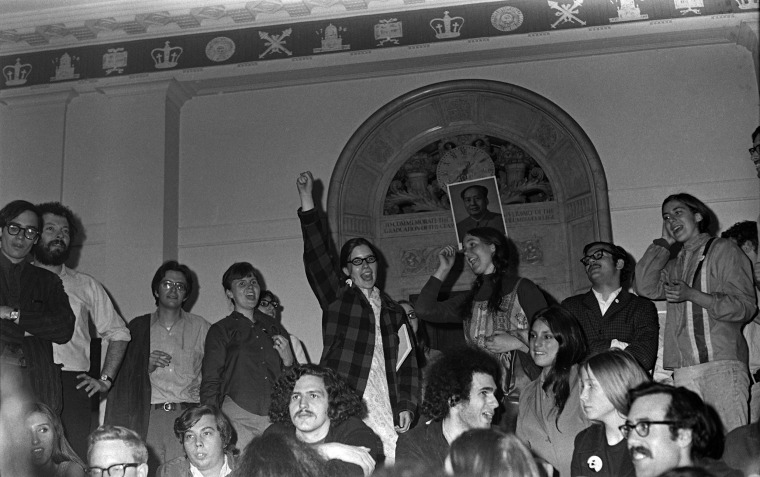

- What does the section header “The War at Home” indicate the section will be about? What caused the war at home? What effects did it have? (The section header indicates that the section will discuss some sort of conflict back in the U.S. related to the Vietnam War. The conflict was that more and more people were becoming critical of the war. Effects include protests against the war and a youth movement.)

- The last section explains that in Vietnam, the conflict is called the American War. Why do you think this is? (Responses will vary, but students should support their ideas with evidence, such as the text details about millions of U.S. soldiers being sent to fight in Vietnam, the anger Le Duc Tho expressed at the Paris Peace Accords, and North Vietnamese forces quickly overrunning the South after the cease-fire.)

5. Use the Primary Sources Use the Primary Source: Project, distribute, or assign in Google Classroom the PDF A Vietnam Veteran Remembers , which features excerpts from a personal essay published in 2017 by Phil Gioia about his experiences fighting in Vietnam. Discuss what makes the essay a primary source. (It provides firsthand evidence concerning the topic.) Have students read the excerpts and answer the questions below (which appear on the PDF without answers).

- How would you describe the tone and purpose of these excerpts from Gioia’s personal essay? (The tone can be described as reflective and straightforward as well as critical in certain parts. The purpose is to describe what it was like to fight during the Vietnam War and to provide a perspective on the effectiveness of U.S. efforts in Vietnam.)

- In the first paragraph, Gioia says “Very lofty.” What does he mean? What was the reality he encountered? (By “very lofty,” Gioia means that the goal of preventing South Vietnam from falling to Communism was noble but difficult to achieve. The reality he encountered was that most soldiers were fighting to simply survive and return home.)

- What is Gioia’s assessment of the North Vietnamese army? Which details help show why he thinks this? (Gioia saw the North Vietnamese army as the enemy because that was his job, but he also respected their skill and determination. His descriptions of them as being “good light infantry” and having an ability to “control the tempo of the war” shows that he recognized their skill. His commentary that their “ability to move troops and equipment south never seemed to slack” and that they ignored truce periods to strategic advantage shows he viewed them as determined.)

- What ideas does Gioia convey through the three questions he asks and answers at the end of his essay? (Through his three questions and responses, Gioia conveys the idea that it was very unlikely that the U.S. would have succeeded—no matter what it tried—in preventing South Vietnam from being defeated by North Vietnam and falling to Communism. He also conveys the idea that the war was so complex that even today it’s hard to recognize what lessons we should have learned from it.)

- Based on the Upfront article and the excerpts from Gioia’s personal essay, why do you think there were so many student protests against the war in the late 1960s and early 1970s? (Students’ responses will vary but should be supported by evidence from both texts.)

Extend & Assess

6. Writing Prompt Read “Escape From Cuba” in the previous issue of Upfront . Based on that article and this one, why do you think one embargo on a Communist country was lifted but not the other one? Explain in a brief essay.

7. Quiz Use the quiz to assess comprehension.

8. Classroom Debate Should the U.S. reinstate the military draft?

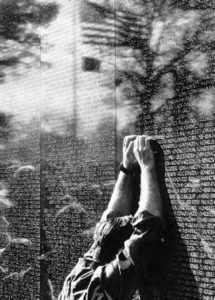

9. Speaking With Meaning Display a photo of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Ask: Why do you think the design for the memorial was originally criticized? Then have students research the memorial and Maya Lin’s vision for it. Bring the class together to discuss why today the memorial is seen as a powerful tribute to those who died in the war.

Download a PDF of this Lesson Plan

- All Teaching Materials

- New Lessons

- Popular Lessons

- This Day In People’s History

- If We Knew Our History Series

- New from Rethinking Schools

- Workshops and Conferences

- Teach Reconstruction

- Teach Climate Justice

- Teaching for Black Lives

- Teach Truth

- Teaching Rosa Parks

- Abolish Columbus Day

- Project Highlights

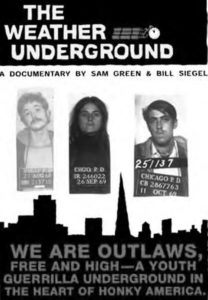

Teaching the Vietnam War: Beyond the Headlines

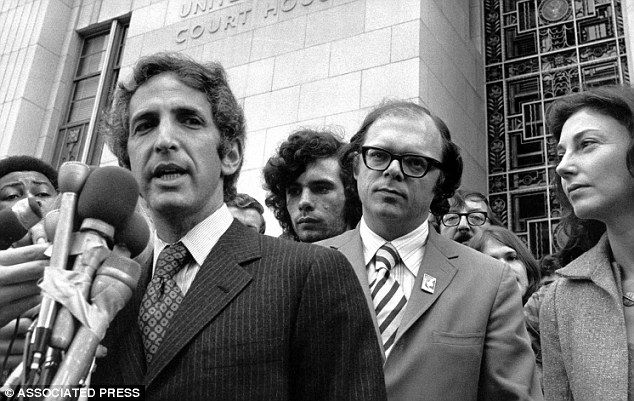

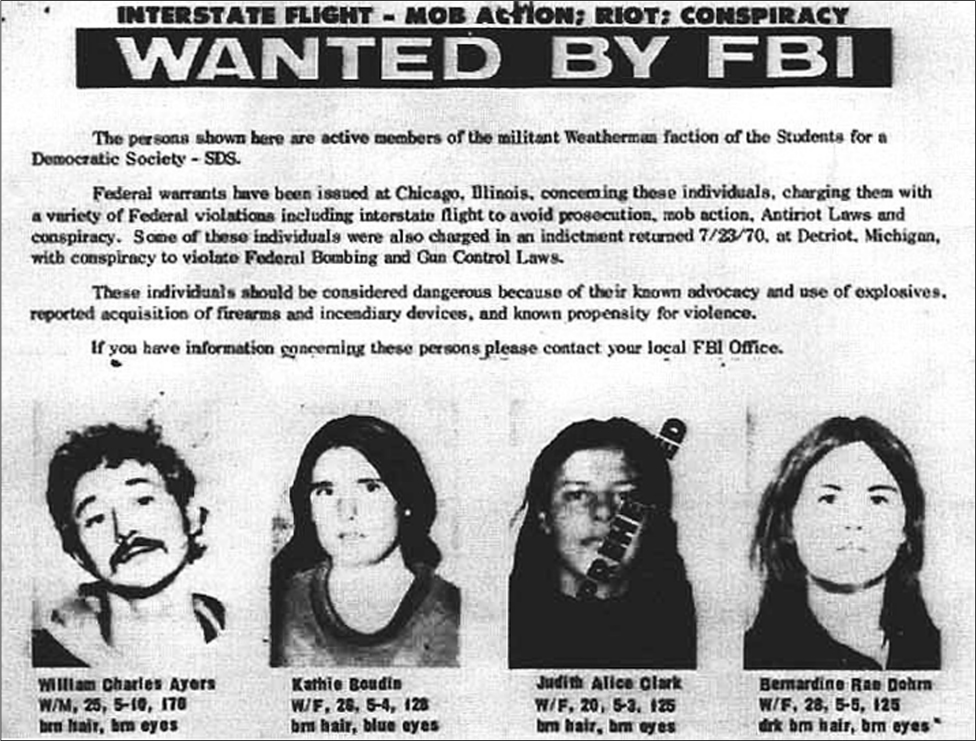

Teaching Activity. By the Zinn Education Project. 100 pages. Eight lessons about the Vietnam War, Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers, and whistleblowing.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

This 100-page teaching guide, prepared by the Zinn Education Project for middle school, high school, and college classrooms, enhances student understanding of the issues raised in the award-winning film, The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers .

The film and teaching guide are ideal resources for students trying to understand the news about WikiLeaks today. Through the story of Daniel Ellsberg, students can explore the type of information revealed by whistleblowers, the risks and motivations of whistleblowers, and the tactics used to silence whistleblowers. Daniel Ellsberg said: “EVERY attack now made on WikiLeaks and Julian Assange was made against me and the release of the Pentagon Papers at the time.”

Not only does Teaching the Vietnam War: Beyond the Headlines offer a “people’s history” approach to learning about whistleblowing and the U.S. war in Vietnam, it also engages students in thinking deeply about their own responsibility as truth-tellers and peacemakers. In the spirit of Howard Zinn, this teaching guide explodes historical myths and focuses on the efforts of people — like Daniel Ellsberg — who worked to end war.

- Lesson One: “What Do We Know About the Vietnam War? Forming Essential Questions” helps the teacher assess what students already know or think they know and surfaces essential questions that can be referenced while viewing the film.

- Lesson Two: “Rethinking the Teaching of the Vietnam War” and Lesson Three: “Questioning the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution” introduce the history of the Vietnam War that Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo sought to make public with the Pentagon Papers and is still missing from most textbooks.

- Lesson Four: “The Most Dangerous Man in America Reception” prepares students for the people, themes, events, and issues that are in The Most Dangerous Man in America through film through a simulated reception with close to 30 characters.

- Lesson Five: “Film Writing and Discussion Questions” provides a wealth of discussion questions and writing prompts.

- Lesson Six: “The Trial of Daniel Ellsberg” is a mock trial that invites students to determine what precedent might have been set with the trial of Ellsberg and Russo if the case had not been dismissed.

- Lesson Seven: “Blowing the Whistle: Personal Writing” provides students with an opportunity to explore the ways they themselves regularly make important choices about whether or not to resist injustice or remain silent.

- Lesson Eight: “Choices, Actions and Alternatives” helps students explore how human agency shapes history. Using the choice points of the Vietnam War, students can recognize the important consequences of decisions and actions by people in history and how they can be agents who can co-shape their world today.

While it would be ideal to use all the lessons, each lesson is a stand-alone activity.

The guide was developed by the Zinn Education Project in collaboration with The Most Dangerous Man in America filmmakers Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith. Written and edited by Bill Bigelow, Sylvia McGauley, Tom McKenna, Hyung Nam, and Julie Treick O’Neill. Funding for the guide provided by the Open Society Foundations.

Related Resources

- Daniel Ellsberg Warns Risk of Nuclear War Is Rising as Tension Mounts over Ukraine & Taiwan on Democracy Now! (May 1, 2023)

- Interview with Daniel Ellsberg on Democracy Now! about WikiLeaks (October 22, 2010)

- Interview with Daniel Ellsberg and others on Democracy Now! about WikiLeaks Cablegate (November 29, 2010)

- Interview with Daniel Ellsberg on The Colbert Report , part of an 8-minute segment on WikiLeaks

- Essays About the Vietnam War by Roger Peace, John Marciano, Jeremy Kuzmarov, and other contributors from Peace History

- Beautiful Souls: The Courage and Conscience of Ordinary People in Extraordinary Times . Book exploring what compels ordinary people to defy the sway of authority and convention for the greater good

- Beautiful Souls: Eyal Press on the Whistleblowers Who Risk All to “Heed the Voice of Conscience.” (March 9, 2012) Interview on Democracy Now!

More resources are listed in the free downloadable teaching guide.

Classroom Stories

I love all of the Zinn Education Project lessons that I have used in the classroom. They are a hit every time. Students have been able to connect with the subject matter at a deeper level and make connections to their current lives.

But my favorites are the Teaching the Vietnam War: Beyond the Headlines lessons. These are rich and thought-provoking. The best part of teaching them, for me, is at the end when students are challenged to think about how they too can advocate for social justice and add their voice to a cause worth fighting.

I’ve never seen a less that upholds and promotes diversity in the classroom as much as this one, Teaching the Vietnam War , allowing students to work individually and in groups to understand the people affected by war. —Hernán Eaves Cuéllar, high school social studies teacher, Portland, OR

We showed the The Most Dangerous Man film in our American Studies class as the ending to our introductory unit on “How we know what we know.” The course is thematic, and so we start our study by reading several different case studies throughout U.S. history and discuss how facts are ascertained and used in history. Questions like “what is truth?” dominate our discussion.

We watched the film along with our reading of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.” As a result, we used Dan Ellsberg’s journey from Vietnam War architect to peace activist as an illustration of the prisoners in the cave watching the shadows and then being lifted up to the light. The kids found Ellsberg’s journey to be both compelling and moving in that light. We centered our discussion on the main points of the journey of an educated person as laid out by Plato. We asked them the question as to what one’s responsibility is when they see “the light” with regard to helping others see as well or to simply go about their lives.

The discussion among the class was compelling. It was clear to them why people would choose to do nothing (i.e. Senator Fulbright), but it was equally compelling to see Ellsberg’s example of risking jail to do the right thing. What an amazing discussion!

The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers

Film. By Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith. 2009. 94 minutes. The riveting story of how a Pentagon official risks life in prison by leaking 7,000 pages of a top secret report to the New York Times to help stop the Vietnam War.

Rethinking the Teaching of the Vietnam War

Teaching Activity. By Bill Bigelow. Rethinking Schools. 8 pages. A role play on the history of the Vietnam War that is left out of traditional textbooks.

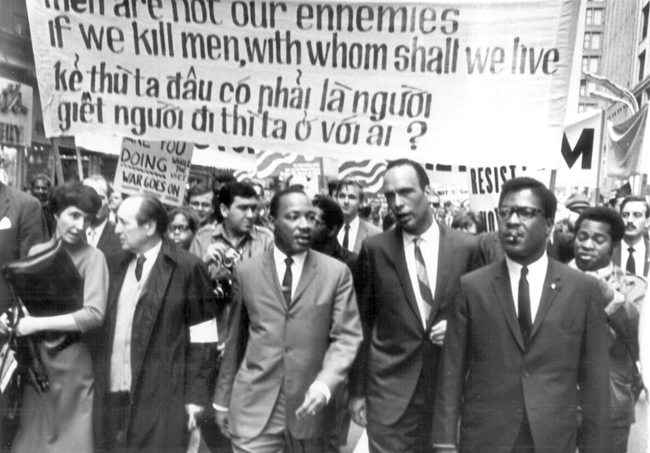

A Revolution of Values

Teaching Activity. By Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. 3 pages. Text of speech by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the Vietnam War, followed by three teaching ideas.

Camouflaging the Vietnam War: How Textbooks Continue to Keep the Pentagon Papers a Secret

Article. By Bill Bigelow. 2013. If We Knew Our History Series. While new U.S. history textbooks mention the Pentagon Papers, none grapples with the actual import of the Pentagon Papers.

Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers

Book — Non-fiction. By Daniel Ellsberg. 2003. 512 pages. A riveting behind-the-scenes account of Ellsberg’s decade of disillusionment leading up to Nixon’s resignation.

The Vietnam Wars: 1945-1990

Book — Non-fiction. By Marilyn B. Young. 1991. 448 pages. A detailed history of the Vietnam War.

Teaching the Vietnam War: A Critical Examination of School Texts and an Interpretive Comparative History Utilizing the Pentagon Papers and Other Documents

Book — Non-fiction. By William Griffen and John Marciano. 1979. 83 pages. Critique of the frameworks of U.S. history texts and engaging alternative history of the war.

Regret to Inform

Film. By Barbara Sonneborn. 1998. 72 minutes. Teaching Guide by Bill Bigelow. Chapter from A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn. A profound documentary on the impact of war, with a teaching guide and the chapter of A People’s History of the United States on the Vietnam War, “Impossible Victory.”

Sir! No Sir!

Film. By David Zeiger. 2005. 84 minutes. This award-winning film demonstrates the role soldiers and veterans played in the anti-Vietnam War movement.

Jan. 3, 1966: Sammy Younge Jr. Murdered

Samuel Younge Jr., Navy vet, Tuskegee student, activist was killed in Alabama for using a “whites-only” bathroom. SNCC issued a powerful statement about his murder and in opposition to the Vietnam War.

Dec. 30, 1971: Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo Jr. Indicted for Releasing the Pentagon Papers

Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony J. “Tony” Russo Jr. were indicted for releasing the Pentagon Papers, detailing the secret history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

May 11, 1973: Pentagon Papers Charges Dismissed

Judge Byrne dismissed all charges against Daniel Ellsberg and Anthony Russo in the Pentagon Papers trial.

9 comments on “ Teaching the Vietnam War: Beyond the Headlines ”

The lessons are so rich and though provoking. The best part for me is at the end when students are challenged to think about how they too can advocate for social justice and share their voice to a cause worth fighting. —Chris Peterson, high school social studies teacher, Minneapolis, MN

I’ve never seen a plan that upholds and promotes diversity in the classroom as much as this one, allowing students to work individually and in groups to understand the people affected by war. —Hernán Eaves Cuéllar, high school social studies teacher, Portland, OR

Thank you for your considerable contribution in helping students understand the true history of the Vietnam war!

There is no way to Peace. Peace is the way. “la lutte continue” (“the struggle continues”)

Thank you for your work.

I gave several excerpts from the Most Dangerous Man curriculum to one of my students for her National History Day project. She was interested generally in the Vietnam War, and after talking with me about this awesome topic I’d read about lately (looking at this curriculum on the Zinn Project website), she decided to research Daniel Ellsberg’s story for History Day. She found the curriculum to be an invaluable source, a great starting point for her research.

As a peace activist, since the 60s, and now a peace advocate and educator, I have witnessed much of modern history first hand. I have also hungered for the facts, which so often are not forthcoming. The Pentagon Papers was the work of one of histories foremost whistle blowers. Daniel Ellsberg helped bring about the end of the Viet Nam insurgency. His courage opened up a new reality for many, that what we are told by the government, may or may not resemble the truth.

Historically, it is never too late for the truth to come out. If we have any chance of not repeating history, it will be because of what we have learned from history!

There were no protective agencies at the time Daniel Ellsberg blew the whistle. We can learn from him not only the truth, but the courage of one man, to stand up and do the right thing.

I brought this film and teaching guide up to a class of soon to be social studies teachers and they didn’t know what the Pentagon Papers were, nor who Daniel Ellsberg is — we have our work cut out for us!

We showed the film in our American Studies class as the ending to our introductory unit on “How we know what we know.” The course is thematic, and so we start our study by reading several different case studies throughout US history and discuss how facts are ascertained and used in history. Questions like “what is truth?” dominate our discussion. We watched the film along with our reading of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.” As a result, we used Dan Ellsberg’s journey from Vietnam War architect to peace activist as an illustration of the prisoners in the cave watching the shadows and then being lifted up to the light. The kids found Ellsberg’s journey to be both compelling and moving in that light. We centered our discussion on the main points of the journey of an educated person as laid out by Plato. We asked them the question as to what one’s responsibility is when they see “the light” with regard to helping others see as well or to simply go about their lives. The discussion among the class was compelling. It was clear to them why people would choose to do nothing (i.e. Senator Fulbright), but it was equally compelling to see Ellsberg’s example of risking jail to do the right thing. What an amazing discussion!

Share a story, question, or resource from your classroom.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

More Teaching Resources

- Vietnam War Essays

The Vietnam War Essay

The dynamics of the Vietnam War make it one of the most complex wars ever fought by the United States. Every element of the war was saturated with complexities beyond the previous conceptions of war. From the critical perspective, for the first half of the twentieth century, Vietnam was of little strategic importance to the United States and, even “after World War II, Vietnam was a very small blip on a very large American radar screen” (Herring, 14). The U.S. knew very little about Vietnam outside of its rice production until the French colonized the country. Even after France’s colonization of Vietnam, a great deal of America’s perspective and the media’s perspective of Vietnam was “devoid of expertise and based on racial prejudices and stereotypes that reflected deep-seated convictions about the superiority of Western culture. In U.S. eyes, the Vietnamese were a passive and uninformed people, totally unready for self government” (Herring, 13). A survey of New York Times articles published during the First Indochina War revealed that the U.S. foreign policy analysis, media and public overwhelmingly concentrated on the French perspective of the conflict. Little attention was given to the Vietminh perspective or to the perspective of the French backed government of South Vietnam. This viewpoint continued until 1949 when China’s civil war ended and the Communist took control of China. Shortly after taking control Mao Zedong, the Communist leader acknowledged the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and the Soviet Union quickly followed suit. After that, the U.S. media placed a greater emphasis on Cold War rhetoric when dealing with Vietnam. As noted, the Cold War mindset permeated much of American culture during this time period; “it was an age of ideological consensus, and this was true above all in foreign policy” (Hallin, 50). At the conclusion of the First Indochina War, the U.S. foreign policy, public and media considered Vietnam as a nation that could spread Communism in Southeast Asia. The focus of the United States foreign policy from 1954 to 1957 looked mainly at the internal affairs of South Vietnam and at Ngo Dinh Diem, and to a smaller degree at the Refugee Crisis after the Geneva Accords. From 1957-1961 the U.S. attention shifted heavily on Vietnam’s fate in relation to the turmoil in Laos and Cambodi as well as to the Soviet threat. This perception dominated the public opinion, media and U.S. foreign policy well into President John F. Kennedy’s Administration.

Struggling with your HW?

Get your assignments done by real pros. Save your precious time and boost your marks with ease. Just fill in your HW requirements and you can count on us!

- Customer data protection

- 100% Plagiarism Free

THE VIETNAM WAR (1955-1975): ANALYSIS OF EVENTS

On August 5, 1964, Congress considered the Southeast Asia Resolution, commonly called the “Gulf of Tonkin Resolution” (Johnson, 118). After two days of debate it passed the Senate by a vote of 88-2 and the House by a resounding 416-0 (Johnson, 118). It was a resolution to deliberately allow the United States a broad hand in protecting peace and security in Southeast Asia. A second section asserted that “peace and security in southeast Asia” was vital to American national security and therefore the president, acting in accord with the Charter of the United Nations and as a member of the South East Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), would “take all necessary steps, including the use of armed force,” to assist member states of SEATO “in defense of [their] freedom” (Young, 109). Finally, the resolution would expire when the president determined “peace and security had returned to the area” (Young, 109). It could also be terminated by a subsequent congressional resolution.

On March 8, 1965, 3,500 Marines landed at Da Nang. In May the first United States Army units arrived (Westmoreland, 124). With air attacks against both North and South Vietnam being launched from bases in the South, airfields were a logical target for forces from the National Liberation Front, the Communist guerrillas fighting against the South Vietnamese, and no one placed much confidence in the protection from the forces of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) (Westmoreland, 123). The United States ambassador to the Republic of Vietnam, Maxwell Taylor, cabled the State Department on February 22, 1965, voicing his concerns about the deployment of Marines in Da Nang to protect the airfield there. In addition Taylor indicated that

Used our essay samples for inspiration ?

For more help, tap into our pool of professional writers and get expert essay editing services!

As for the use of Marines in mobile operations rather than static defense, [The] [w]hite-faced soldier, armed, equipped, and trained as he is not suitable guerrilla fighter for Asian forests and jungles…there would be [the] ever present question of how foreign soldier[s] would distinguish between a [Viet Cong] and a friendly Vietnamese farmer. When I view this array of difficulties, I am convinced that we should adhere to our past policy of keeping ground forces out of direct counterinsurgency role (Young, 139).

Between 1965 and 1967, the United States military strategy in Vietnam had two major facets. The first involved strategic bombing of North Vietnam, and the second involved killing more Viet Cong and North Vietnamese regulars fighting in South Vietnam than could be replaced by new communist troops (McNamara,, 237). President Johnson used the bombings and bombing pauses to pressure the North Vietnamese to conduct peace talks and bring the war to an end as quickly as possible.

But the war failed to end, and in early 1969, a counterattack occurred. In the opening hours of the Tet Offensive, Viet Cong troops attacked thirteen of the sixteen provincial capitals of the Mekong delta of Southern Vietnam and many of the district capitals (Oberdorfer, 113). Part of the shock of Tet was the contrast between recent official American military optimism that the war was drawing to a close and the public’s perception of the disparity between that optimism and the reality illuminated by the Tet attacks. The Viet Cong led the brunt of the communist Vietnamese attacks. In the majority of battles of the Tet Offensive throughout South Vietnam, the Viet Cong suffered crippling casualties. South Vietnamese and American casualties were proportionately less.

From tactical perspective, the Tet Offensive was a military failure for the communist Vietnamese. The main goal of the Tet Offensive was to incite a general uprising of the South Vietnamese population by demonstrating a powerful show of communist force. However, no general uprising occurred as a result of the Tet Offensive. The casualties sustained by the Viet Cong took a tremendous toll on the Viet Cong’s ability to conduct guerrilla raids on South Vietnamese and American forces for the remainder of the Vietnam War.

From the strategic viewpoint, the Tet Offensive was one of the communist Vietnamese’s greatest victories, because it severely affected the United States government’s political will to wage war in Vietnam. Prior to the offensive, the Commanding General of the United States Military Assist Command Vietnam (MACV), General William Westmoreland, had stated that the war was winding down and that the United States could “see light at the end of the tunnel” (Oberdorfer, 271). Upon hearing news reports of massed communist attacks throughout Vietnam, the existing American public support for the war eroded further. In March 1968, upon hearing of General Westmoreland’s request for 200,000 more American combat troops in Vietnam while 500,000 servicemen and women were already fighting in Vietnam, the American public not only felt deceived but believed that the situation in Vietnam was unwinable or that the cost in American lives was too high (Oberdorfer, 271). The Tet Offensive marked one of the most significant turning points in the Vietnam War (Oberdorfer, 280).

Between 1968 and 1972, strategic bombing and bombing halts continued to be used to induce the North Vietnamese to engage in significant peace talks. American combat patrols continued throughout the South Vietnamese countryside to find and eliminate the Viet Cong presence. The Viet Cong and North Vietnamese continued to erode the South Vietnamese government’s power and make the casualty toll on American forces higher and less bearable to Americans at home. Significant changes occurred in key positions on both sides of the conflict. Richard Nixon won the 1968 election. Along with President Nixon, his National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger began American troop withdrawals in 1969 (Herring, 226). Ho Chi Minh died in 1969, and First Secretary Le Duan succeeded as the head of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (Duiker, 561).

On January 23, 1973, the United States signed the nine-point proposal from the North Vietnamese delegates that called for a cease-fire to allow for the withdrawal of United States forces from Vietnam. In Vietnam itself, the North Vietnamese followed some elements of the cease-fire agreement, particularly those which included the health and well-being of the American armed forces prisoners. The release of the remaining American prisoners of war occurred simultaneously with the departure of the last combat soldier, and both sides made arrangements for search teams to continue to look for soldiers missed on the battlefields. On the sixtieth day after the truce, the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) officially closed down, declaring its mission accomplished (Young, 219). When the last American soldiers had left Camp Alpha, the processing barracks at Tan Son Nhut air base in Saigon, it was systematically dismantled by Vietnamese soldiers and civilians (Young, 220). The last American troops in Vietnam left on March 29, 1973. Nevertheless, from 1973 to 1975 the South Vietnamese continued to fight the war without United States combat troops, using only weapons and supplies. On April 30, 1975, the South Vietnamese government ordered a general cease-fire to all remaining loyal troops as North Vietnamese regulars occupied the southern capital city of Saigon. The Vietnam War was over.

THE VIETNAM WAR (1955-1975) AND THE U.S. MILITARY STRATEGY

The initial United States military strategy from 1959-1964 was to provide military advisors to train the South Vietnamese military in its war against the communist forces of the North Vietnamese and insurgents in the South, the Viet Cong. A major lesson learned from the previous conflict the United States was involved in, the Korean War, was to fight a limited war that would not provoke larger and more powerful communist countries from getting directly involved. The United States, throughout the Vietnam War up until its withdrawal in 1973, limited its actions against the Vietnamese communists in order to not provoke neighboring China or the Soviet Union from getting more involved. From 1959 to 1964, American military advisors and United States Army regular and special forces were deployed to South Vietnam and attached to South Vietnamese military units. Their mission was to train the fledgling South Vietnamese in effective combat techniques.

The United States wanted a South Vietnamese victory over the communists with minimal United States involvement. Presidents Harry S Truman, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson wanted to avoid another war and to focus American resources elsewhere (McNamara, 40). The United States government and military knew that it was highly unlikely for China or the Soviet Union to get directly involved if the United States limited its role to advising and allowed the South Vietnamese to fight their own battles. The United States understood that a military victory would be more likely were American troops deployed to Vietnam. It believed that such action would not be necessary.

The Gulf of Tonkin incident in June 1964 changed the United States’ military strategy in Vietnam. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution passed by Congress allowed President Johnson to commit military forces “to protect the interests of the United States.” Whereas prior to the Tonkin episode American soldiers could not directly engage in combat, after the Marines landed at Da Nang in March 1965, the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution authorized American soldiers to directly engage with enemy forces. This marked a significant shift in American military strategy in Vietnam. Not long after the Marines landed to defend the air base at Da Nang from local Viet Cong attacks, the commanding general of Miliatry Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) General Westmoreland shifted American forces’ posture in Vietnam from defensive to offensive.

Throughout the Vietnam War, the United States imposed several strategic limitations on its military forces to minimize the risk of broadening the war. The United States did not want to repeat having the Chinese directly enter the war militarily. The most significant limitation was the refusal to send ground troops into North Vietnam or to send any American forces including air and ground forces into neighboring Laos or Cambodia (Westmoreland, 44). The military value of sending ground troops into North Vietnam to destroy troop and supply staging areas, occupy and deny use of strategic areas, and force the communist Vietnamese to assume a defensive posture and fight on ground of the Americans choosing would have been enormous.

The United States military did not leave North Vietnam unmolested. While American ground troops were not authorized to cross the 17th parallel dividing North and South Vietnam, the United States placed relatively few restrictions on sending bombers over North Vietnam with the goal to demolish North Vietnamese military supplies and weaponry before it could be used in South Vietnam (Kissinger, 239). The American strategy regarding the air war over North Vietnam was to inflict the maximum amount of damage and casualties on the North Vietnamese necessary to make them lose their will to fight (Kissinger, 239). The objective was to kill enough soldiers, destroy enough rice, which was the main staple of all Vietnamese people’s diets, and demolish enough bridges, railways, factories that the North Vietnamese could no longer wage war effectively against the South Vietnamese and its American ally. The United States’ fury that was held in check by withholding ground troops from North Vietnam spurted out in the air campaigns conducted from 1965-1973 (Kissinger, 239).

Moving supplies during any military conflict is vital. One of the biggest challenges American and South Vietnamese forces faced throughout the Vietnam War was the North Vietnamese ability to supply their communist South Vietnamese allies, the Viet Cong, through Laos and Cambodia, a supply line dubbed the Ho Chi Minh trail after the North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh (Westmoreland, 389). The United States’ military strategy towards the Ho Chi Minh Trail centered on two facets. First was to destroy or prevent the supplies from North Vietnam aerially while they were still located in North Vietnam. Second was to position American and South Vietnamese forces along the South Vietnamese western border and so keep supplies from reaching the South.

Related Essays

Find Free Essays

We provide you with original essay samples, perfect formatting and styling

Request must contain at least 2 characters

Popular Topics

Samples by Essay Type

Cite this page

About our services

Topic Vietnam War

Level College

This sample is NOT ORIGINAL. Get 100% unique essay written under your req

- Only $11 per page

- Free revisions included

Studyfy uses cookies to deliver the best experience possible. Read more.

Studyfy uses secured cookies. Read more.

Vietnam War - Free Essay Samples And Topic Ideas

The Vietnam War was a protracted and contentious conflict from 1955 to 1975 between North Vietnam, supported by communist allies, and South Vietnam, backed by the United States and other anti-communist countries. Essays could delve into the complex geopolitics of the Cold War era that framed this conflict, examining the differing ideologies and interests that fueled this long and costly war. The discourse might extend to the military strategies, the notable battles, and the human cost endured by both civilians and military personnel. Discussions could also focus on the anti-war movement within the United States, exploring how the Vietnam War significantly impacted American politics, society, and culture. Furthermore, the lasting effects of the war on Vietnam and its relations with the U.S., along with the contemporary narratives surrounding the war and its veterans, could provide a well-rounded exploration of this crucial period in 20th-century history. A vast selection of complimentary essay illustrations pertaining to Vietnam War you can find at Papersowl. You can use our samples for inspiration to write your own essay, research paper, or just to explore a new topic for yourself.

The Civil Rights Era and the Vietnam War for the USA

The Vietnam War was a conflict between North and South Vietnam with regards to the spread of communism. The communist North was supported by other communist countries while the South was supported by anti-communist countries, among them the United States. In South Vietnam the anti-communist forces faced off against the Viet Cong, a communist front. The involvement of the United States in the Vietnam War was ironical by the civil rights movements because despite their fight for democracy abroad and […]

The Sixties Civil Rights Movement Vs. Vietnam War

The 1960s were a very turbulent time for the United States of America. This period saw the expansion of the Vietnam War, the assassination of a beloved president, the civil rights and peace movements and the uprising of many of the world’s most influential leaders; known as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Over the years, scholars have discussed the correlation between the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement. It has been argued that violence happening overseas directly […]

The Cold War: Severe Tension between the United States and the Soviet Union

The feuding began after World War II, mostly regarding political and economic power. After the destruction that World War II caused, the United States and the Soviet Union were left standing. Gaining control of countries was sought after, even if the countries weren't benefiting them in any way. During this time, it was all about power. From the years of 1957 to 1975, the Cold War was in full effect and the United States and the Soviet Union were in […]

We will write an essay sample crafted to your needs.

The Domino Theory and the Vietnam War

This investigation will explore the question: To what extent was the Domino Theory validated by the progress and outcomes of the Vietnam War? The years 1940 to 1980 will be the focus of this investigation, Vietnam War started after World War 2 and ended in 1975. More than 1 million Vietnamese soldiers and over 50,000 Americans were killed in the war. China became a communist country in 1949 and wanted to spread communism throughout Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh ( nationalist […]

American Involvement in Vietnam War

The frustration of Nixon was clearly building with the failure despite all sorts of efforts. A futile invasion of Cambodia, continued but ineffective Vietnamization policy, no cooperation from PRC, and an attempt to cripple the North into negotiations through bombing; nothing seemed to be working. This incapability to find a solution further led the Nixon administration to continue bombing on the North, with a wrong perception that raw control on the battle will gain them advantage. After this series of […]

Modern American Imperialism

By the end of the 18th century, the British Empire was one of the biggest colonial powers in the world. It had colonies in many countries across the world such as India and Australia. There were other colonial powers such as Spain, France, and the Netherlands. One of the latest countries which entered the imperialistic way was the U.S. It saw that other countries, especially Great Britain, were gaining resources, territories and most importantly dominance over the world. The U.S. […]

The Vietnam War in U.S History

The Vietnam War has been known in U.S history as the longest and most controversial war. The United States became involved in Vietnam to avoid having the country fall to a communist form of government. There were numerous fateful battles that claimed countless lives of those on both sides of the war. This war also resulted in many conflicts for the United States on the home front of the war, when the American people no longer supported the war. North […]

Comparison between World War II and Vietnam War

A half century ago the world, and most specifically America, was an extremely different place. As the world moved out of the World War II era, changes came in droves. America and the Soviet Union would move into a Cold War with a space race, while the rest of the world would watch in awe. In 1961, John F. Kennedy was inaugurated as the 35th president of the United States. Segregation was at an all-time high, so was the fight […]

Effects of the Cold War

The Cold War was a time of hostility that went on between the Soviet Union and the US from 1945 to 1990. This rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union lasted decades and created a result in anti communist accusations and international problems that led up to the two superpowers to the brink of nuclear disaster. During World War II, the Soviet Union and United States fought together as allies against the axis powers. However, the two nations […]

The Soldiers in the Vietnam War in the Things they Carrie

In Tim O'Brien's "The Things They Carried", we are told a story about what the soldiers in the Vietnam War carried with them and in particular what First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross carried with him. The way the story is told gives a glimpse of each soldier's personality based on the items that they carried with them. First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross carries letters from a girl named Martha with whom he is infatuated. Although she did not send them as love […]

The Vietnam War in History

The Vietnam war was a conflict between the north and south vietnam governments and the time span of this war began from 1954 all the way down to the year of 1975 fighting in the locations or North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. One important fact was the south of vietnam had an ally who were the United States, but also the north had help from China and the Soviet Union. With the two enemies having their own allies […]

Cold War Effects on America

The Cold War certainly changed and shaped the American economy, society, and politics from 1945 to 1992. The contrasting beliefs between Communism (the Soviet Union) and Democracy (the United States) caused the rift between the worlds top two most prominent superpowers -- Communism had established itself to be an immediate challenge to the importance of the United States of America. To stop these two world powers from becoming an even larger global conflict, a few military interventions were established in […]

The Vietnam War in the World History

Silence is all the soldiers could hear but they knew that they weren't alone. Soldiers from a foreign country attacked them from the shadows. Thousands of young American men were killed in the forests deep in Vietnam. The national interest of America that Americans developed after the Yalta Conference encouraged us to join the Korean War which led to the Vietnam War,the most regretted war in US History, guided America when it comes to foreign policies. At the end of […]

What is Vietnam War Known For?

Vietnam, a nation that had been under French colonial rule since the 19th century. During World War II, Japanese forces invaded Vietnam. To fight off both Japanese occupiers and the French colonial administration, political leader Ho Chi Minh. In 1945 the defeat in World War II, Japan withdrew its forces from Vietnam, leaving the French-educated Emperor Bao Dai in control. This was seen as an opportunity to gain control; Ho's Viet Minh forces immediately rose up to take over the […]

Depictions of the Vietnam War in the Book Things they Carried

In order to convey ideas or meanings to readers throughout their pieces of work, authors use different literary techniques. In The Things They Carried, Tim O’Brien employs a multitude of different devices to immerse the reader in his experiences during the Vietnam War. To depict the brutality and barbarity of war, O’Brien evokes images and discloses themes not only through metaphors, repetition, and irony, but also through the use of juxtaposition. By comparing seemingly contradictory and opposite ideas or images, […]

Impact of Vietnam War

The Vietnam War began in 1955 and lasted for 20 years or so. President Truman created a foreign policy that can assist countries that have instability due to communism. Truman then came up with the policy of the Truman doctrine. The causes of the Vietnam War was believed held by America that communism was going to expand all over south-east Asia. Neither of the U.S and Soviet Union could risk a war against each other because of the nuclear military […]

Yearbook of Psychology between 1961 and 1971

Introduction Prisoners go through lots of psychological processes when they are confined within the cells. They sometimes go against the orders or follow them according to the types of prisons they occupy. However, there have been various concerns about the psychological aspects of prisoners or those that serve jail terms. This therefore created the need to conduct studies on the psychological aspects of Zimbardos and Milgram? work. This study discusses the major comparisons and contrast between Zimbardo and Milgrams research […]

The Erosion of American Support for the Vietnam War

To begin, a massive amount of Americans are considered to be nationalistic and resonate with patriot appeals. A well known U.S rhetoric quote claims that America is "the greatest nation in the world". This can be used to U.S military advantage because it encourages or motivates United States citizens to support their country politically and to remain patriotic. As a result, in the 1950s, Americans had almost unconditionally support for their countries military actions and were fully on board with […]

Music and Society in Vietnam War Era

The Vietnam War is arguably the most controversial war in American history. To this day, our role and positioning in the struggle for power remains an enigma. It can be argued that we concerned ourselves in the struggle to deny the spread of communism, but it can be equally contended that we were there to suppress nationalism and independence. The publicized aesthetic showed that the war was between North and South Vietnam, but from '55 to '65 the escalation period […]

The Vietnam War and the U.S. Government

From the 1880s until World War II, France governed Vietnam as part of French Indochina, which also included Cambodia and Laos. The country was under the formal control of an emperor, Bao Dai. From 1946 until 1954, the Vietnamese struggled for their independence from France during the first Indochina War. At the end of this war, the country was temporarily divided into North and South Vietnam. North Vietnam came under the control of the Vietnamese Communists who had opposed France […]

How the Vietnam War Changed Diversity in America

The Vietnam War was a war of great controversy. The Vietnam War has the longest U.S. combat force participation to date, 17.4 years. This is closely followed by efforts in Afghanistan. U.S. combat force participation in Afghanistan is 17 years and continuing. The Vietnam War was a fatal one for U.S. armed forces. There are 58,220 total recorded military deaths from the war as of 2008 from the Defense Casualty Analysis System (U.S. Military Fatal Casualty Statistics, n.d.). Although the […]

Forest Gump as a Source for Studying History

' Life is like a box a chocolate, you never know what you are going to get ' as said in the novel Of Forest Gump I say would be as I would like to think the statement to portray the film from start to finish. In this exposition, I will expound on Forrest's life venture as a tyke to a grown-up and how his life can be contrasted with a container of chocolates. Right off the bat, the film […]

Analysis of the Vietnam War

Last Days in Vietnam shows how powerful this media can be when talented people dig deep into the often-complex history of the Vietnam War. Most convincing in the narrative is its introduction of the ethical bind confronting numerous Americans amid their most recent 24 hours in Saigon, regardless of whether to obey White House requests to clear just U.S. subjects or hazard charges of treachery to spare the lives of the greatest number of South Vietnamese partners as they could. […]

How the Hippie Movement Shaped the Anti-Vietnam War Protests

Rootsie, a young teen hippie coming of age during in the mid-1960s, saw the evils of the Vietnam War, which included the unnecessary deaths of fellow Americans who fought a war that could have been avoided, as many may argue. Hence, she overlooked the superficialities of the Vietnam War that the government imposed upon America to gain a deeper truth about the hippies: "these people were saying that spiritual enlightenment can save the world, bring an end to war and […]

American Troops in the Vietnam War

Lyndon B. Johnson was the 36th President of the United States, coming into the office after the death of President John F. Kennedy in November 1963. At the time of World War II, Johnson earned a Silver Star in the South Pacific serving in the Navy as a lieutenant administrator. Johnson was chosen to the Senate in 1948 after six terms in the White House. Before serving as Kennedy's vice president, Johnson had represented Texas in the United States Senate. […]

Vietnam War and Crisis

In 1887, France imposed a colonial system over Vietnam, Tonkin, Annam, Cochin China and Cambodia, calling it French Indochina. Laos was added in 1893. Upon the weakening of France during WWII, Japanese troops invaded French Indochina. In 1945, Japanese troops carried out a coup against French authorities and declared Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia as independent states. When Japan was defeated, a power vacuum opened over Indochina. France began to reassert its authority, and met resistance from Ho Chi Minh and […]

Sino Vietnamese Just War

The Sino-Vietnamese War, also known as the Third Indochina War, occurred in 1979 when troops from the People's Republic of China attacked the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. This war came after the First Indochina War and the Vietnam War (or the Second Indochina War). The First Indochina War lasted from 1946 to 1954 and involved a conflict between China and the Soviet Union backed Vietnam and France to control the area called Indochina. While the communist People's Republic of China […]

Entangled Histories: Unraveling the Causes of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War, a tumultuous chapter in history, was born from a tapestry of interconnected causes, each thread weaving a complex narrative of historical, ideological, and geopolitical tensions. Colonialism served as a catalyst. Vietnam, part of French Indochina, endured French colonization, fueling aspirations for independence. Nationalist movements burgeoned, fermenting resistance against foreign rule and planting seeds of self-determination. Post-World War II dynamics set the stage. With the collapse of colonial powers after Japan's occupation, Vietnamese nationalists, spearheaded by Ho Chi […]

The Longest War Fought in America’s History

The Vietnam War was iniated in November 1st 1955 and was finished on April 30 1975 because communism was starting to grow in Vietnam and the U.S wanted to keep it contained. At the time President Nixon was really worried that if Vietnam was to become communist other nations would soon follow and switch to communism. Ultimately at the end of the war there were a million plus casualties on both sides. The war officially ended in 1975 with the […]

The Cold War and U.S Diplomacy

My take on President Kennedy's doctrine ""Respond flexibly to communist expansion, especially to guerrilla warfare from 1961 to 1963"". The doctrine by President John F. Kennedy. During the Second World War, the Soviet Union and the United States worked together in fighting Nazi of Germany. The coalition between the two parties was dissolved after the end of the war in Europe. During the Potsdam conference, the tension broke up on July when the two parties decided to share Germany. The […]

Additional Example Essays

- PTSD in Veterans

- Veterans: Fight for Freedom and Rights

- Women's workforce in World War II

- Research Paper #1 – The Trail of Tears

- History of Mummification

- Christianity in the Byzantine Empire

- History: The Fall of the Roman Empire

- How the Great Depression Affected African Americans

- Was Slavery the Cause of the Civil War Essay

- The Importance of Professional Bearing in the Military

- Gender Inequality in Education

- “Allegory of the Cave”

How To Write an Essay About Vietnam War

Writing an essay on the Vietnam War is a task that combines historical research, analysis, and personal reflection. This article will guide you through the process of writing such an essay, with each paragraph focusing on a crucial aspect of the writing journey.

Initial Research and Understanding

The first step is to gain a thorough understanding of the Vietnam War. This includes its historical context, key events, major political figures involved, and the impact it had both globally and domestically in the countries involved. Start by consulting a variety of sources, including history books, scholarly articles, documentaries, and firsthand accounts. This foundational research will give you a broad view of the war and help you narrow down your focus.

Selecting a Specific Angle

The Vietnam War is a vast topic, so it's crucial to choose a specific angle or aspect to focus your essay on. This could range from political strategies, the experiences of soldiers, the anti-war movement, the role of media, to the aftermath and legacy of the war. Selecting a particular angle will not only give your essay a clear focus but also allow you to explore and present more detailed insights.

Developing a Thesis Statement

Based on your research and chosen angle, formulate a strong thesis statement. This statement should encapsulate your main argument or perspective on the Vietnam War. For instance, your thesis might focus on the impact of media coverage on public perception of the war, or analyze the strategies used by one side and how they contributed to the outcome. Your thesis will guide the structure and argument of your entire essay.

Organizing Your Essay

Structure your essay in a clear, logical manner. Start with an introduction that sets the scene for your topic and presents your thesis statement. The body of your essay should then be divided into paragraphs, each focusing on a specific point or piece of evidence that supports your thesis. This could include analysis of key battles, political decisions, personal stories from veterans, or the war's impact on domestic policies. Ensure each paragraph transitions smoothly to the next, maintaining a cohesive argument throughout.

Writing and Revising

Write your essay with clarity, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by evidence. Use a formal academic tone and cite your sources appropriately. After completing your first draft, revise it to enhance coherence, flow, and argument strength. Check for grammatical errors and ensure all information is accurately presented.

Final Touches

In the final stage, review your essay to ensure it presents a comprehensive and insightful perspective on the Vietnam War. Ensure that your introduction effectively sets the stage for your argument, each paragraph contributes to your thesis, and your conclusion effectively summarizes your findings and restates your thesis.

By following these steps, you will be able to write a compelling and insightful essay on the Vietnam War. This process will not only deepen your understanding of a pivotal historical event but also refine your skills in research, analysis, and academic writing.

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

The Vietnam War’s and Student’s Unrest Connection Essay

The involvement of U.S. combat troops in the Vietnam War led to historic incidences in the U.S. related to protest protocols. There were obviously some U.S. citizens who supported war and, on the other hand, there were some U.S. civilians who were against the war. Among the protesters of the war were college/university students. The student protests were so passionate that they eventually turned into riots that halted operations in most cities of the United States.

Efforts by guardsmen to counteract the riots led to the deaths of a number of students and protesters, and they also left a score of casualties. This had many effects on the socio-political structure of the United States with the masses losing their trust in their leaders and new anti-riot protocols being adopted (Roberts, 2005, p. 1). This paper explores the connection between the Vietnam War and student unrest and also looks into the socio-political changes that the two caused in the United States.

By the end of the 1960’s decade, American colleges and universities had become increasingly tumultuous as more American troops were killed in Vietnam. The United States government had sent troops to Vietnam at the middle of the decade to help South Vietnam in their War. South Vietnam was fighting with North Vietnam which was governed by communists.

As the decade ended, more than 38000 Americans had lost their lives in the Vietnam War. This made the war increasingly unpopular among American citizens with college students being the most vocal against the Vietnam War (Ryan, 2008, p. 1).

The reason why students were actively involved in Vietnam War protests is because the government was forcing students to go to war after completion of their college education. Male students were expected to register for military service after attaining age eighteen.

They would then wait for two years after which the probability of being drafted for the war was very high. This is because American casualties in the war were many and replacement soldiers were required (Roberts, 2005, p. 1). Young men, therefore, hid themselves in colleges and were not thrilled by the approach of their graduation dates.

The students had to find a way out. Some of them went to hide in Canada while others opted for protests aimed at making the congress end the requirement of the students to go to Vietnam after graduation. This was the main connection between the Vietnam War and Protests by students. The most remembered of the student protests against Vietnam War was the protest by Kent University students.

It all started with the announcement by President Nixon on the 30 th day of April that the United States had decided to attack Cambodia. This led to the burning down of an army training centre in the Kent State. Several stores in town were also broken into. Loaded with M-1 rifles the guards went out searching the protesters and determine to utilise the combination of their arms with tear gas. Students then called for a rally during midday to continue their protests.

This led to a teargas-versus-stones battle between the guard officers and the students. The officers were overpowered by the students and they took refuge in a nearby hill where they opened fire killing four and injuring nine. This led to a week-long protest of students all over the U.S. who were angered by the Kent state shootings, the Vietnam War and several other grievances for specific universities (Roberts, 2005, p. 2).

An example of such protests were held by the by the University of Washington during the national strikes that took an approximate one week as a reaction to the Kent University shootings and a culmination of the student unrest over the involvement of the United States government in the Vietnam war and also the sending of students to Vietnam to die in the war after the completion of their studies.

The students from the University of Washington also had their institutional needs that they wanted the government to address during the week-long protests. They particularly wanted the government to give them their status as opponents of the war in Southeast Asia. These protests had a significant change on the social and political structure of the United States government.

As mentioned earlier, the Vietnam War and the resultant student protests had a lot of socio-political effects in United States. The financial repercussions brought about by the war weighed the United States government down to the extent that President Johnson had to increase taxes to finance the additional troops that were required with increased frequency. Social programs suffered greatly as their budgetary allocations were decreased substantially to finance the war.

Prior to the Vietnam War, the American public had confidence in their leaders (Ryan, 2008, p. 2). With the involvement of the American government in the war, the public was not able to figure out why a military intervention was necessary in Vietnam. This made the public lose their trust and confidence in their leaders and thus they stopped supporting those in government. The war also impacted the polls. Most American civilians held the idea that their government ought to stop exercising control over the rest of the world.

There was therefore a change in the preference of political candidates. The masses supported politicians who promised to help in ending the war. Republicans secured more political seats in the elections that followed with their counterparts, the democrats losing most of their political seats (Bexte, 2002, p. 1). The most significant impact of the involvement of university students in war protests was an overnight change in the way protests and riots were treated in the United States.

The famous picture of a fourteen-year-old female student crying over the killing of her fellow student in the Kent state riot scene remains indelibly imprinted in the minds of the Americans who saw it at the time. Whenever protests are counteracted by the police violently in the United States, the memory of the Kent state riot and the subsequent killing of four students occupy the minds of Americans (Ryan, 2008, p. 1). It can be argued that the Vietnam War student riots revolutionized protests in the United States.

The involvement of the United States government in the Vietnam War can be viewed to have been, arguably, a good thing. The forcing of young men to be involved in the war was, indubitably a bad thing but it gave the Unites States government and the world a very important lesson: that no government can force its young citizens to go to war and escape protests.

The financial crisis and political shift that followed the war was also a lesson. It is no doubt that the United States government remembers the Vietnam War and makes several considerations based on the Vietnam War before being involved in any war. It is no doubt that if the aforementioned draft was re-introduced, the government will face a lot of protests whose effects could even be worse than the Vietnam-War student riots.

Reference List

Bexte, M. (2002). The Vietnam War protests. Web.

Roberts, K. (2005). 1970 tragedy at Kent State: with the Vietnam War escalating, Ohio National Guard Troops fired at a crowd of student protesters, killing four of them. Web.

Ryan. J. (2008). Student unrest and the Vietnam War. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, May 20). The Vietnam War’s and Student’s Unrest Connection. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-vietnam-war/

"The Vietnam War’s and Student’s Unrest Connection." IvyPanda , 20 May 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/the-vietnam-war/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'The Vietnam War’s and Student’s Unrest Connection'. 20 May.

IvyPanda . 2020. "The Vietnam War’s and Student’s Unrest Connection." May 20, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-vietnam-war/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Vietnam War’s and Student’s Unrest Connection." May 20, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-vietnam-war/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Vietnam War’s and Student’s Unrest Connection." May 20, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-vietnam-war/.

- Difficulties in Using Kent as a Historical Source

- Shooting at Kent State University

- Rally: Deaf President Now (Dpn)

- 800 Supporters of Sal Castro March on School Board

- The Kent State University May 1970 Shootings

- Kent Fire and Rescue Service: Training and Development

- Kent Chemical Company's International Strategy

- The case of Rockwell Kent and Secretary of State

- The Graphic Novel "Kent State: Four Dead in Ohio" by Derf Backderf

- Different Opinions About Riots

- The Aftermath of the American Civil War

- Effects of War on America

- Slavery, the Civil War & Reconstruction

- Los Angeles’ Chinatown: Key Features and Influence on Ideology

- Vietnam War: John Kerry's Role

Vietnam War Research Paper Topics

Welcome to iResearchNet’s comprehensive guide on Vietnam War research paper topics . This page is tailored specifically for students studying history who have been tasked with writing a research paper on this pivotal period of global conflict. Here, you will find a wealth of thought-provoking and diverse research topics that will allow you to delve into the complexities and impacts of the Vietnam War.

100 Vietnam War Research Paper Topics

The Vietnam War stands as one of the most significant and contentious conflicts of the 20th century, leaving an indelible mark on global history. For students studying this era, exploring the multitude of Vietnam War research paper topics is a compelling opportunity to gain insights into the complexities of war, diplomacy, society, and culture. In this section, we present an extensive and diverse list of research paper topics, meticulously organized into ten categories. Each category offers ten thought-provoking Vietnam War research paper topics, inviting students to delve into various facets of the conflict and its far-reaching impact. Whether you are interested in the war’s origins, military strategies, social ramifications, or the aftermath, this comprehensive list will inspire and guide you in crafting a well-informed and engaging research paper.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

Causes and Background of the Vietnam War

- French Colonialism in Vietnam: The Seeds of Conflict

- Ho Chi Minh and the Rise of Vietnamese Nationalism

- The Role of the United States in the Early Stages of the Conflict

- The Domino Theory and its Influence on U.S. Foreign Policy

- Assessing the Impact of World War II on the Vietnam War

- Roots of Anti-Communist Sentiments in the U.S. Government

- Examining the Geneva Accords and their Implications for Vietnam’s Future

- The Influence of the Cold War on the Vietnam Conflict

- The Interplay of Economic Interests and Colonial Ambitions in Indochina

- Religious and Ethnic Factors in the Conflict: Buddhism, Catholicism, and Cao Dai.

Military Strategies and Tactics

- Guerrilla Warfare and Its Impact on the Vietnam War

- The Tet Offensive: A Turning Point in the Conflict

- The Role of Media in Shaping Public Perception of the War

- Air Warfare: Operation Rolling Thunder and its Effectiveness

- The Use of Chemical Agents in the War: Agent Orange and Napalm

- The Battle of Ia Drang: Analyzing U.S. Troop Deployments

- The Ho Chi Minh Trail: A Supply Line that Shaped the War

- U.S. Strategic Bombing Campaigns and Their Consequences

- The Vietnamization Policy and Its Effects on the Conflict

- Evaluating the Role of Special Forces in Vietnam: Green Berets and Navy SEALs.

Social and Cultural Aspects of the War

- The Anti-War Movement in the United States: Origins, Key Figures, and Impact

- Media Coverage and Its Influence on Public Opinion

- Music of Protest: Folk, Rock, and the Counter-Culture Movement

- The Role of Women in the Vietnam War: Nurses, Volunteers, and Activists

- The Plight of Prisoners of War (POWs) and Missing in Action (MIAs)

- Protests and Resistance in Vietnam: Voices from the Viet Cong

- The Effects of PTSD on Veterans and Their Reintegration into Society

- Ethnic Minorities in the War: African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics

- The Impact of the Draft on American Society and Attitudes toward the War

- Artistic Expressions of the War: Literature, Film, and Photography.

Diplomacy and Peace Negotiations

- Paris Peace Accords: Negotiating an End to the Vietnam War

- The Role of Diplomacy in Resolving the Conflict: Successes and Failures

- Challenges and Obstacles to Peace Talks: Ideological, Political, and Military

- The Influence of Public Opinion on Peace Negotiations

- The Nixon-Kissinger Approach to Diplomacy: Realpolitik and Detente

- Assessing the Role of China and the Soviet Union in the Peace Process

- The Problem of Dual Recognition: North Vietnam and the Provisional Revolutionary Government

- Economic Sanctions and their Role in Negotiations

- The Impact of the Anti-War Movement on Diplomatic Efforts

- The Continuing Legacy of the Vietnam War in U.S. Foreign Policy.

Human Rights and War Crimes

- My Lai Massacre: Uncovering the Atrocities and Accountability

- Agent Orange and its Aftermath: Environmental and Human Health Impacts

- The Ethics of Targeted Killings and Assassinations during the War

- The Role of the International Red Cross and Humanitarian Efforts

- The Treatment of POWs in North Vietnamese Camps

- War Crimes Trials and the Pursuit of Justice: The Case of Lieutenant William Calley

- The Impact of the War on Children and Civilians: Orphans and Refugees

- War Crimes and Atrocities Committed by All Sides: A Balanced Perspective

- Examining the Legal and Moral Arguments of Bombing Civilian Targets

- The Ongoing Debate on War Crimes and Historical Reconciliation.

Impact and Aftermath of the Vietnam War

- Veterans’ Experiences and Challenges After the War: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- The Economic Impact of the War on Vietnam and the United States

- The Reconciliation Process between Vietnam and the United States

- The Legacy of the Vietnam War in U.S. Politics and Presidential Power

- The Vietnam War and Environmental Destruction: Deforestation and Agent Orange

- The Influence of the Vietnam War on Military Strategy and Doctrine

- The Vietnam War and the Emergence of the “Military-Industrial Complex”

- The Impact of the War on Asian-American Communities in the United States

- The Effects of the Vietnam War on American Public Opinion and Trust in Government

- The Emergence of Vietnam War Literature and its Cultural Significance.

The Role of Women in the Vietnam War

- Female Combatants in the Viet Cong: Roles and Contributions

- Nursing and Medical Care during the War: Women on the Frontlines

- Women’s Activism and Participation in the Peace Movement

- The Experience of American Military Nurses in Vietnam

- Women in Intelligence Agencies: Spies and Operatives

- The Impact of the War on Vietnamese Women: Challenges and Resilience

- Women as War Correspondents and Journalists

- Female Representation in the North Vietnamese Government and Army

- The Role of Women in the Anti-War Movement: Voices for Peace

- The Evolution of Gender Roles in Vietnamese Society during the War.

Intelligence and Counterintelligence

- The Role of the CIA and Other Intelligence Agencies in Vietnam

- Codebreaking and Communication Interception: Decrypting Enemy Messages

- Espionage and Double Agents in the Conflict: Aldrich Ames and Robert Hanssen

- Assessing the Effectiveness of Military Intelligence in Vietnam

- The Tet Offensive and Intelligence Failures: Lessons Learned

- Psychological Warfare and Propaganda: Deception in the Vietnam War

- The Phoenix Program: Intelligence-Led Counterinsurgency Efforts

- The Role of Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) in Shaping the War

- Intelligence Sharing between the United States and its Allies

- Evaluating the Role of Human Intelligence (HUMINT) in Gathering Information

Regional and Global Implications of the Vietnam War

- The Domino Theory and its Impact on U.S. Foreign Policy

- The Vietnam War’s Influence on Cold War Dynamics

- Vietnam as a Case Study in Nation-Building and Intervention

- The Impact of the Vietnam War on Southeast Asia: Regional Stability and Conflicts

- Assessing the Influence of the Vietnam War on Latin American Revolutionary Movements

- The Role of Australia and New Zealand in the Vietnam War: ANZUS Treaty Obligations

- China’s Involvement in the Vietnam War: Motives and Consequences

- The Soviet Union’s Support for North Vietnam: Political and Military Aims

- The Vietnam War and Africa: The Pan-Africanist Movement’s Response

- The Vietnam War and European Allies: NATO’s Dilemmas and Responses

Comparing the Vietnam War to Other Conflicts

- Vietnam War vs. Korean War: A Comparative Analysis of Strategies and Outcomes

- The Vietnam War and the Soviet-Afghan War: Lessons Learned and Repercussions

- Assessing the Similarities and Differences between the Vietnam and Iraq Wars

- Comparing Vietnam and World War II: The Role of Technology and Total War

- The Vietnam War and the Gulf War: Asymmetrical Warfare in Modern Conflicts

- The Vietnam War and the French-Algerian War: Colonial Legacies and Revolutions

- Vietnam War vs. The American Revolutionary War: Fighting for Independence

- The Vietnam War and the Falklands War: Island Conflicts and National Identity

- Comparing the Vietnam War to the Russo-Japanese War: Imperial Ambitions and Defeats

- The Vietnam War and the Spanish Civil War: International Interventions and Ideological Battles

You have now explored a vast array of Vietnam War research paper topics, spanning from the causes and background of the conflict to its far-reaching consequences on the global stage. By delving into these categories, you have the opportunity to uncover the multi-dimensional nature of the Vietnam War, analyze its intricacies, and grasp its profound implications. Whether you are fascinated by military strategies, diplomatic efforts, social aspects, or the aftermath, these topics will serve as a stepping stone to crafting an engaging and insightful research paper. Remember to select a topic that aligns with your interests, access credible sources, and stay objective in your analysis. Embark on your research journey with zeal, and let the knowledge you gain from these Vietnam War research paper topics contribute to a deeper understanding of this transformative period in history.

Vietnam War and Its Range of Research Paper Topics

The Vietnam War, spanning from 1955 to 1975, was a momentous conflict that not only reshaped the geopolitics of Southeast Asia but also left a profound impact on global history. Its intricate tapestry of political, military, social, and cultural dimensions provides a vast array of research paper topics for students studying history. Understanding the scope and significance of this war allows researchers to explore a myriad of intriguing themes that shed light on the complexities of human conflict, diplomacy, and societal transformation.

At the core of Vietnam War research lies the examination of its causes and background. Topics in this category delve into the historical underpinnings of the conflict, including the role of French colonialism in Vietnam, the rise of Vietnamese nationalism under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, and the interplay of major powers like the United States and the Soviet Union in shaping the conflict’s trajectory. Investigating the roots of the war not only provides insights into the events that led to the outbreak of hostilities but also highlights the significance of broader historical contexts, such as the Cold War and the post-World War II era.

Military strategies and tactics employed during the Vietnam War form another intriguing avenue for research. The war’s unique nature, characterized by guerrilla warfare and asymmetrical tactics, challenges conventional notions of military engagements. Students can explore topics such as the Tet Offensive, which marked a turning point in the conflict, the use of psychological warfare and propaganda, and the effects of chemical agents like Agent Orange and napalm. Additionally, investigating the impact of media coverage and the role of journalists during the war sheds light on how public perception can influence the outcomes of armed conflicts.