Zeroes or Zeros: Noun, Verb, Adjective, and Plural Forms

By: Author Dr. Patrick Capriola

Posted on Published: March 4, 2021

Ones and zeros, everything in life is just ones and zeros, or is it ones and zeroes? We can make things either incredibly simple or incredibly difficult by reducing everything to ones and zeros, whatever that means, but, for now, we need to decide, is it “zeros” or “zeroes”?

Zero can be used as either a noun, verb, or adjective. The adjective is not conjugated, and just the base form of ‘zero’ is used. As a noun, it can be pluralized as either “zeros” or “zeroes.” Both spellings are indicated in American English but not in British English. The verb is conjugated by adding -es to the third-person singular.

Although these differences can seem tricky at first, they are quite simple when the distinctions are clarified. Let’s delve into the different ways that the word zero can be conjugated.

Zero Is a Number

If you look for “zero” in a dictionary, it is first and foremost a noun. It is the number 0 written out and indicates the absence of a magnitude or quantity.

It is the numerical value between all the negative and all the positive numbers — a cipher. As a noun, it can, of course, be pluralized, and that is where the spelling woes start ( source ).

Pluralizing a Noun

The majority of nouns need to be altered in some way to create the plural noun. There is a general set of rules, based upon the letters or letters on which a word ends, that make pluralization easier.

As is usually the case with something as fluid and complicated as language, the rules are not always clear-cut, and there are numerous exceptions to every rule, as in the following example.

Rule: If a word ends on an -f or -fe, remove the -f or -fe, replace it with a -ve, and add an -s.

However, as with most rules in English, there are exceptions.

When it comes to words ending in an -o, there are also rules. Different sources will explain either one or two rules and then add some examples of exceptions. We will have a look at both of the rules one can find, as well as the exceptions:

Rule 1: For words ending -o where a vowel precedes it, we add -s:

Note that most English words ending in an -o will be pluralized by adding -s, but the other consideration is:

Rule 2: For words ending on an -o preceded by a consonant , we add -es.

However, this is not always provided as a rule but, rather, as part of the exception. The reasoning is that there are far fewer words that have -es added. Moreover, it is becoming even less popular to spell plural o-words like this.

The Exceptions

We cannot always explain the reason for exceptions to spelling rules, and we simply must learn them, which can make it difficult for second-language speakers.

Words ending in an -o preceded by a consonant, for example, can only have an -s for the plural, like “photos,” “pianos,” and “solos” ( source ).

Although the rules for plurals ending in -o follow largely the addition of an -s to the end, some pluralized exceptions have their own categories and, as a result, we have irregular nouns that don’t follow any of the rules as noted above:

Other nouns have a zero plural, which means that they don’t undergo any type of change.

This is often the case with animals, and the phenomenon has its roots in Old English, where some animals never had plural forms to begin with. In certain situations, the plural naming of other animals followed suit:

Apart from these exceptions, we also have many words ending in -o that can be written with either an -s or -es to mark it as plural. It is into this category that we have to place “zero.” Other examples include:

The traditional rule would dictate that we write the plural of “zero” by adding an -es, so the plural would be “zeroes.” However, many dictionaries will indicate that both “zeros” and “zeroes” are correct.

If this is the case, how you write it will depend on personal preference, and both of the following sentences will be perfectly fine to use:

There are six zeros in the figure 1,000,000.

There are six zeroes in the figure 1,000,000.

For more information on zero, have a look at our article, “ Is 0 an Irrational or Rational Number? ”

The British Zero

A wonderful but potentially complicated phenomenon of language in general is the fact that we sometimes have to contend with different dialects. In this regard, English is no different, and American English can often differ from British English.

The question as to how “zero” is pluralized is one instance of such a difference.

When you search for “zero” in the Oxford English Dictionary, arguably the most authoritative source of British English, you will find that they only provide “zeros” as a pluralization option.

It means that “zeros” is the only spelling of the plural, and “zeroes” is not an acceptable alternative for this dialect ( source ).

“Zeroes” does exist in British English but only as a verb that is conjugated for the present third-person singular. We will take a closer look at this later.

The Cambridge Dictionary is similar to the Oxford English Dictionary in that the online version’s first entry also provides “zeros” as the sole plural form of the noun.

However, note that once the word is qualified as being used in Business English, the “zeroes” alternative is also provided ( source ).

The Plural of Zero

“Zeros” is the correct plural form of the word zero in both American English and British English ( source ). The reasons why only “zeros” seems to be correct in British English while we can use either “zeros” or “zeroes” in American English is unclear.

This means that it is a matter of personal preference for users of American English as to whether they choose to write the plural of “zero” as “zeros” or “zeroes.”

“Zero” as other Parts of Speech

Apart from the fact that “zero” is a number, it also functions as other parts of speech, i.e., it is a verb and an adjective as well.

“Zero” as a Verb

When used as a verb, “zero” is often written as a phrasal verb with “in” and refers to either aiming a weapon, adjusting a weapon, or focusing your attention. Consider the following:

When the phrasal verb is “zero out,” it means that you reduce something to zero or to remove something completely:

When used as a verb, “zero” follows the normal rules of a verb in its different tenses and persons. Let’s use the first example above with the verb in its various forms.

In the present simple tense, the verb changes according to its subject, and for the third-person singular, it usually means adding an -es. For “zero,” it means the spelling is the same as one of the plural versions of American English:

The present continuous requires the verb “to be” to undergo conjugation according to the person plus the present participle (verb ending in -ing):

In the past tense, we simply use the verb in its past form, meaning we usually add -ed:

“Zero” as an Adjective

Nouns can often act as adjectives, and “zero” is no different. As such, it is defined as relating to or being zero. When this adjective modifies a noun, it will indicate that there is nothing of that noun ( source ).

The adjective is not conjugated in any way and remains in the root form of the word.

Consider the following:

The economy showed zero growth.

The students made zero progress on their project.

The verb “zero in” can also be used as an adjective. In this case, however, it will be conjugated:

The zeroed in rifle shot perfectly every time.

In Summary: A Comparison

The summary below provides a quick overview of the different parts of speech and formats that are applicable to “zero”:

Synonym Options

Due to the different parts of speech that “zero” can be used in, there are many synonym options that mean almost exactly the same thing, while others have a slight difference in meaning but convey the same idea.

Final Thoughts

“Zero” functions as a noun, verb, and adjective. As a result, it has a number of different suffixes that can be added to it as well as a lengthy list of possible synonyms that can be used.

In American English, pluralizing the number “zero” by adding -s (“zeros”) or adding -es (“zeroes”) are both correct. In British English, it is only correct to add -s (“zeros”), and -es (“zeroes”) is only used for the conjugation of the verb in the third-person singular.

If you are writing an English competency test based on British English, it would be wise to remember this distinction and avoid “zeroes” as a plural form.

The Story of Zero

The number zero denotes no objects. The number 0 was first used in the Indian subcontinent. Its use can be traced back to the 3rd Century A.D. in the Bakhshali manuscript. This new number was called ‘Shunya’ or ‘Sunyata’ in Sanskrit which means nothingness or the void which points to the lack of something that was represented by this new number. Zero has no. of uses; zero has become very crucial part of our modern systems as it is used in the binary numerical system which is the foundation of our computers today.

Zero. A number that wasn’t always a number has become the most important number in mathematics and many other subjects today. The invention of zero or rather the realisation that it was a number just like any other, was one of the most important moment and one of the greatest leap in the history of mathematics, one that would encourage the rise of modern science. Today, the number zero forms an integral part of not just Physics, but also a part of Chemistry, Astronomy and even Computer Science!

Zero, as we know, was the last number ever to be discovered. In ancient times, people couldn’t understand the idea of denoting nothing with something! They simply expressed it with nothing. To the Greeks, the zero simply hadn’t existed. However, to the Egyptians, the Mesopotamians and even the Chinese the number existed but simply as a place holder. Similarly, even the Babylonians and the Mayans did in fact use zero but as a place holder. A place holder here means something that occupies a certain given space. But they never used a symbol. They would just leave it blank; an empty space to show a zero inside a number. This was a very ancient idea.

For example: How would you write the number hundred and one? Today, everyone would write it as “101”.

However, the Babylonians and the Mayans would write it with a space in between the two ‘1’s like so- “1 1”

So then where did the number zero really come from? Let’s find out!

The number 0 was first used in the Indian subcontinent. Its use can be traced back to the 3 rd Century A.D. in the Bakhshali manuscript. It was, at this time used by merchants in their calculations. However, zero did not have the same shape as it does today. It was simply a dot that was used to denote the ‘nothing’.

The zero in the form of a dot did not just appear in the Bakhshali manuscript but it can also be found in an inscription engraved on the wall of a small temple in the fort of Gwalior in the heart of India, Madhya Pradesh. This inscription dates back to the 9 th century A.D. Thus, this dot that denoted a zero was being used for centuries in India before it was ever introduced to the world.

So, taking from our previous example where the Babylonians kept a space, the Indians used a dot instead. It would have looked something like this “1.1”. However that is just one of the uses of the number zero. Brahmagupta, a mathematician in India, in the 7 th Century A.D., developed rules to use zero in calculations such as addition and subtraction. This opened up the use of numbers in a whole new way! In this way, the Indians transformed the number zero from being a mere place holder into a number that made sense in its own place. Now with the 10 digits including the number zero, it became increasingly easy to count large numbers efficiently.

Are you wondering where the idea to use a dot to denote the absence of a number came from? I sure am.

One theory is that this idea came from the use of stones for calculations. When a stone was moved from its place, it left a round hole in its place representing the change from something to nothing. That round hole or dent looked like a dot which probably led to its use as a place holder. Thus the dot came to represent the nothingness that was present or rather the absence of a number within a larger number.

This new number was called ‘Shunya’ or ‘Sunyata’ in Sanskrit which means nothingness or the void which points to the lack of something that was represented by this new number.

The number zero became a number for calculation, for investigation and thus changed the face of mathematics. It was a revolutionary finding for the world. After this new number began to spread to different parts of the world beginning with China and the Arab countries, over the centuries, its use became more widespread and more widely accepted.

Zero has many uses, two of which we have already become privy to. One is its use as a place holder, and the other being in calculations of addition, subtraction and even multiplication. In this way zero stands as a number in itself and so its position in the number system has the important function of separating the negative numbers from the positive ones by standing in between -1 and +1.

Zero later went on to form the cornerstone, that is, the most important part of Calculus which allows one to break down systems into smaller and smaller numbers approaching zero but never having to divide by zero which is an impossible thing to do. Finally, zero has become an important part of our modern systems as it is used in the binary numerical system which is the foundation of our computers today. This makes zero, the number that means nothing, the most important number we have today as it opened up the scope of mathematics.

You should not Miss This:

- Why cant you divide by zero?

- Single Digit Addition Workbook

- Space Crafts For Kids

- Fruits Connect the Dot Worksheets for Kids

- Prime Numbers Math Worksheets for Kids

- Add 3 numbers on a number line Printable Worksheets for Grade 1

GK Quiz for Class 3

- Number lines & Equations Printable Worksheets for Grade 1

Related Articles

Q: A polygon with 5 sides is called a _________. (A) Nonagon (B) Octagon (C) Hexagon (D) Pentagon Q: What is the young one…

Colorful Rainbow Crafts for Kids

Craftwork is not limited to kids, in fact, it’s not confined to any age limit. By doing craftwork our creativity increases. We are in school,…

GK Quiz for Class 4

Q: Which is the largest island in the world? (A) Iceland (B) Greenland (C) Andaman & Nicobar (D) Maldives Q: What is the name…

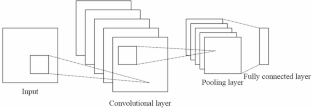

How to Teach Kids About Computer in a Delightful Way

Computers are one of most seen thing in present time. They’re things we use for almost every function, to send mail, write a story, talk to…

GK Quiz for Class 2

Q: Name the shape with three sides. (A) Circle (B) Triangle (C) Square (D) Rectangle Q: What is the smallest two-digit number? (A) 10…

You must be logged in to post a comment.

How to Say Zero in English.

by Shanthi Streat | 9 Apr, 2013 | Business English , Financial English | 0 comments

A strange topic for a blog? Or is it?

Consequently, I often find myself dedicating part of a Business English lesson on the different ways the English Language has of saying this apparently simple figure.

In this blog post, I’m going to consider the British English (BrE) and American (AE) versions. I’d be very interested to know if there are any other versions in other parts of the English-speaking world.

0 is zero and in British English, it’s sometimes known as nought .

In telephone numbers , room numbers , bus numbers and dates (years), we say oh .

Here are some examples:

- The meeting is in Room 502 (five oh two)

- You need to take Bus 205 (two oh five)

- She was born in 1907 (nineteen oh seven)

- My telephone number is 07781 020 560 ( oh double seven eight one oh two oh five six oh OR zero seven seven eight one zero two zero five six zero)

For football scores we say nil : ‘The score was three nil (3-0) to Barcelona’.

For temperatures we say zero : ‘It’s zero degrees celsius today (0°)

The decimal point (Notice that in English we say decimal point, and not a dot as in internet addresses). In British English, zero and nought are used before and after a decimal point. American English does not use nought.

Oh can be used after the decimal point. Here are some examples:

- 0.05 zero point zero five OR nought point nought five

- 0.5% zero point five percent OR nought point five percent.

- 0.501 zero point five zero one OR nough t point five nought one OR nought / zero point five oh one

Over to you now. Try saying the following:

- Can I have my bill please? I’m in Room 204.

- The exact figure is 0.002.

- Can you get back to me on 0208 775 3001.

- Look, it’s less than 0.0001! Let’s not worry about it.

- 0.75% won’t make a lot of difference.

What do you find the hardest when saying zero in English?

I hope you found this blog post useful. Please share it if you think your friends and colleagues would find it beneficial, too.

Ciao for now.

If you’d like to receive my blog posts on a regular basis, why not subscribe to my blog?

Source: Financial English, Ian MacKenzie (2012) Heinle Cengage Learning

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Download Your FREE E-Book

Privacy Overview

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of zero in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- Temperatures rarely rise above zero in winter .

- Plus 8 is eight more than zero.

- The temperature has fallen below zero.

- The temperature could fall below zero overnight .

- I missed out a zero when dialling her number .

- duodecillion

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

- We strive for zero accidents . Every accident is a terrible tragedy .

- To me and many Americans he has zero credibility .

- We got zero applause between songs , and the sketches went over so poorly we abandoned one in the middle .

- He had zero experience of running a big organization .

zero | American Dictionary

Zero number ( number ), zero noun [u] ( nothing ), zero adjective [not gradable] ( not any ), zero | business english, examples of zero, translations of zero.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

a large amount of ice, snow, and rock falling quickly down the side of a mountain

Keeping up appearances (Talking about how things seem)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Number Adjective

- zero (NUMBER)

- zero (NOTHING)

- zero (NOT ANY)

- Business Noun

- Translations

- All translations

To add zero to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add zero to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Speak Languages Better

We value your privacy. We won't spam your wall with selfies.

To learn more see our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service .

Free Language Learning Tools

Free Audio Dictionary

How to say "Zero"

We have audio examples from both a male and female professional voice actor.

English (US)

Practice saying this sentence

Female Voice

English (uk), how to say "zero" in other languages, more resources.

Most Common Phrases

Share us on social media:

- google+

Speechling Comprehensive User Guide Our Mission Speechling Scholarships Meet the Team White Paper Pricing Community

Spanish Blog French Blog English Blog German Blog Italian Blog Portuguese Blog Russian Blog Korean Blog Japanese Blog Chinese Blog

Free Dictation Practice Free Listening Comprehension Practice Free Vocabulary Flashcards Free Language Quiz Free Fill in the Blank Exercises Free Audio Dictionary All Tools

Social Links

Privacy Policy Terms of Service Speechling uses Flaticon for icons.

Speechling for Education Careers Affiliate Marketing Contact

[email protected]

+01 424 645 5957

+39 347 378 8169.

Home / Blog /

Zero Article in English Grammar

- Parts Of Speech

Zero: credit Pixabay (license)

The Zero Article does not exist. But it is very useful nonetheless.

Talking about the zero article is useful when we’re describing how to use articles. But essentially when we talk about the zero article we mean that we do not use any article in front of a noun. In other words, we do not use a/an or the .

This article (excuse the pun) talks about when we do not use an article with a noun.

Articles and Nouns

Normally we use articles with nouns:

Did you see a dog chasing the cow who was eating an apple?

The rules for using articles are fairly straightforward. However, sometimes we don’t use any article at all. In other words, we use a zero article . These rules are explained below.

General/Non-Countable Nouns

We don’t use an article if we’re talking about things in general (i.e. we’re not talking about a specific example) or with non-countable nouns:

Do you like cheese ?

He adores dancing .

But if we want to talk about a specific piece of cheese we can use an article and say:

Pass me the cheese please!

OMG the dancing in the show was terrible!

Proper Nouns

Proper nouns – or names – don’t usually take an article:

I saw Rhianna in the high street!

* I saw the Rhianna in the high street!

* An asterisk denotes an ungrammatical sentence.

However, if we want to distinguish a specific person (as oppose to someone else with the same name) then we can use the definite article:

A: I met Jennifer Lopez this morning.

B: What? The Jennifer Lopez?

A: No! My flatmate’s sister is also called Jennifer Lopez; I’m not talking about the singer.

Noun + Preposition

When we use a noun with a preposition we often do not use an article (that is, we just use the noun on its own):

I went to school but left my books at home . Mother was in church and father at sea ; Grandfather came to dinner later by train and Grandmother managed to escape from prison to join us.

Institutions

When we talk about an institution , we use the zero article. When we talk about it as a physical building , however, we use the :

He was taken to court to be tried; in the court he met an old friend.

Nouns in this group include: bed, church, class, college, court, home, hospital, market, prison, school, sea, town, university, work .

The Planets

In general we use the zero article (i.e. no article) with planets.

Mars has 2 known moons while Saturn has 62 known moons.

When it comes to our planet, we can take or leave the article:

The Earth is getting over populated. The Challenger returned to Earth successfully.

(NB We use the about half the time when we talk about Earth.)

However, we almost always use an article when we talk about the sun in our solar system (or a sun in general) and the moon which circles the Earth.

The Sun is about 150 million km from the Earth but the moon is only 385,000 km.

In general then:

- use a zero article (i.e. no article) with planets

- optionally use the with Earth

- use the to talk about the Sun

- use the to talk about the moon around our Earth

Also…

We also don’t use an article with:

Exceptions include: the Hague; the Matterhorn; the Mall; the White House, the United States of America.

Useful Links

Articles in English Grammar – an overview of articles in English

Definite Articles in English Grammar – a more detailed look at Definite Articles

Indefinite Articles in English Grammar – a more detailed look at Indefinite Articles

ICAL TEFL Resources

6 tips to make your esl classes more effective, hear some tips and advice from samantha: for current tefl students.

- How To Use Competition to Motivate Your TEFL Students

- Tips for Teaching Academic Writing to Non-Native Students

- Country Guides

- English Usage

- Finding TEFL Jobs

- Foreign Languages vs English

- How To Teach English

- Language Functions

- Language Skills

- Lesson Plans & Activities

- Linguistics

- Past Graduates

- Qualifications for Students

- Qualifications For TEFL Teachers

- Sentence Structure

- Teaching Around The World

- Teaching Materials

- Teaching Young Learners

- Technology & TEFL

- TEFAL (Teaching English for a Laugh)

- TEFL Schools

- The ICAL TEFL Blog

- Varieties Of English

- Vocabulary & Spelling

Related Articles

The ICAL TEFL site has thousands of pages of free TEFL resources for teachers and students. These include: The TEFL ICAL Grammar Guide. Country Guides for teaching around the world. How to find TEFL jobs. How to teach English. TEFL Lesson Plans....

Teaching is undeniably a challenging job, in fact many consider it one of the most difficult careers you could choose. Nevertheless, being a teacher is an enriching experience. Through quality education and effective teaching methodologies,...

Samantha is a previous student of ICAL TEFL on the 120-hour course. Based in USA at the moment, Samantha is looking forward to the future and where she could be using her certificate next ... Before completing your course, what were your...

Very useful

before the names of planets we have been using the….are we wrong?

I’m afraid, yes. Yuo see, we don’t use articles in front of names of planets. So, for example, we don’t say “The Mars” but simply “Mars”.

Privacy Overview

Breaking News English

Home | help this site, 5-speed listening (zero - level 6).

Written zero 500 years older than scientists thought

Medium (British English)

Medium (N. American English)

Try Zero - Level 4 | Zero - Level 5

See a sample

- pre-reading and listening

- while-reading and listening

- post-reading and listening

- using headlines

- working with words

- moving from text to speech

- role plays,

- task-based activities

- discussions and debates

More Listening

20 Questions | Spelling | Dictation

Scientists from Oxford University in England have discovered that the written use of the zero is 500 years older than previously thought. The scientists used carbon dating to trace the symbol's origins to a famous ancient Indian scroll called the Bakhshali Manuscript. Scientists found the scroll dates back to the third century, which makes it the oldest script using the symbol. Before the carbon dating of the scroll, scientists believed the manuscript was created in the eighth century. It was found in the village of Bakhshali in 1881. The zero symbol that we use today evolved from a round dot frequently used in India. This symbol can be seen several times on the manuscript.

Marcus Du Santoy, a mathematics professor at Oxford University, explained the significance of the zero in our lives. He told Britain's 'Guardian' newspaper that: "Today, we take it for granted that the concept of zero is used across the globe and is a key building block of the digital world. But the creation of zero as a number in its own right, which evolved from the placeholder dot symbol found in the Bakhshali manuscript, was one of the greatest breakthroughs in the history of mathematics." Zero has many names in English, including nought, nil (in football) and love (in tennis). It is often said as "oh" in the context of telephone numbers. Informal or slang terms for zero include nowt, nada, zilch and zip.

- E-mail this to a friend

Easier Levels

Try easier levels. The listening is a little shorter, with less vocabulary.

Zero - Level 4 | Zero - Level 5

This page has all the levels, listening and reading for this lesson.

← Back to the zero lesson .

Online Activities

- 26-page lesson (40 exercises)

- 2-page MINI lesson

- Speed Read (4 speeds)

- Text jumble

- Prepositions

- Missing letters

- Initials only

- Listen & spell

- Missing words

Help Support This Web Site

- Please consider helping Breaking News English.com

Sean Banville's Book

- Download a sample of my book "1,000 Ideas & Activities for Language Teachers".

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of zero verb from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

Definitions on the go

Look up any word in the dictionary offline, anytime, anywhere with the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary app.

Nearby words

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Zero that -clauses in the history of English. A historical sociolinguistic approach (1424–1681)

The present paper traces the history of zero and that as competing links for object clauses in the history of English from chronological and sociolinguistic perspectives. Even though the zero link is sporadically attested in Old English, the rise of the zero complementizer takes place in late Middle English and is well-established in the second half of the sixteenth century, becoming more frequent in speech-based text types (trials, sermons) or in texts representing the oral mode of expression (fiction, comedies). The use of this construction is then observed to diminish drastically in the eighteenth century, plausibly as a result of the prescriptive bias of grammarians ( Warner 1982 ; Fanego 1990 ; Rissanen 1991 , Rissanen 1999 ; Finegan and Biber 1995 ). Our analysis is based on five high frequency verbs, to know , to think , to say , to tell and to hope , and their syntactic behaviour in the Parsed Corpus of Early English Correspondence , especially in the periods 1424–1499, 1500–1569, 1570–1639 and 1640–1681. Our approach aims at showing progress of the zero link along the S curve in these four periods, before it became thwarted in the eighteenth century. We also aim at plotting the diffusion of zero that -clauses against the social hierarchy of the period in order to detect (i) the existence of social stratification for this variant, and, if such be the case, (ii) the social group or groups that were leading the diffusion of the change in the different chronological stages, thus (iii) tracing the social origin and direction of the change as diffusing from below or from above in sociolinguistic terms.

1 Introduction

An object clause, also sporadically referred to as a comment clause in the literature ( Warner 1982 ; Huddleston and Pullum 2002 : 951), is the kind of clause functioning as the direct object of the matrix verb. In English the most common type of object clause is introduced by the complementizer that , as in I know that Peter will arrive soon , traditionally labelled as a that -clause ( Quirk et al. 1985 : 1049). It can be omitted, except in formal contexts, leaving an asyndetic zero that -clause, i.e. I know Peter will arrive soon . [1]

Both constructions can nowadays be used interchangeably and with no apparent difference in meaning, even though various factors have been considered to account for the choice between the two alternatives. Elsness (1984 : 519) lists four conditioning factors directly influencing the use of that or the zero link: (i) style , whether formal or informal, the former consistently favouring the use of that ; (ii) the matrix verb , there being particular preferences towards the syndetic or the asyndetic construction depending on the nature and frequency of the matrix verb; (iii) potential ambiguity , that being preferred in cases where zero might lead to ambiguity, particularly when there are intervening elements between the matrix verb and the clause; and (iv) semantic contrast , that chosen where “the connective points to the preceding context”, thus retaining some of the anaphoric force that it used to have when it functioned as a demonstrative in previous stages of the history of English ( Elsness 1984 : 519). There have been other insights into the topic providing further evidence on the semantics of the construction ( Storms 1966 ; Dor 2005 ), its discourse features ( Thompson and Mulac 1991 ) or register variation ( Biber 1999 ).

From a historical perspective, Jespersen justified the use of this complementizer in view of the existence of two originally independent sentences: I think: he is dead and I think that [demonstrative pronoun pointing to what follows, namely]: he is dead . Jespersen’s (1933 : 350–351) historical explanation considered that “in the course of time that was accentually weakened […] and this weak that was eventually felt to belong to the clause instead of to what precedes, and by that very fact became what we now call a conjunction”. In the light of this, two questions are implicitly answered. The first one has to do with the nature of the original object clause link in English: it is not possible to consider the absence of that as a mere dropping of the conjunctive element (the terms omission or deletion being then inaccurate), but rather as the typical speech-based object link in the history of English ( Rissanen 1991 : 287–288; cf. Bolinger 1972 : 14). The second has to do with the function of the zero link, as the use of that “helps to mark a clause boundary, and it tends to be deleted more as this function is less useful” ( Warner 1982 : 175). Therefore, zero is favoured in those contexts in which the boundaries of the clause are transparent, i.e. before other conjunctions and before pronouns. On the contrary, if a non-finite form of the verb or any other intervening element appears between the matrix verb and the clause, the use of that becomes more than expected. In this sense, some grammatical contexts of the matrix verb have been seen as constraints on the use of that or zero: the syndetic connector being often preferred if the verb occurs in a non-finite form ( Rissanen 1991 : 286), in the passive voice ( Rohdenburg 1996 , Rohdenburg 2006 : 143–166) or when the matrix verb is negated ( Suárez Gómez 2000 : 193).

Zero that -clauses may be traced back to the early English written records ( Mustanoja 1960 ; Fischer 1992 : 313). In Old English, their frequency is low, the asyndetic forms mainly used when the subjects of the main and the subordinate clause are the same or before a complement representing the exact words of the reported proposition ( Mitchell 1985 : §1976ff; Traugott 1992 ; Palander-Collin 1997 ; Hosaka 2010 ). In Middle English, in turn, Warner estimates a rough figure of 4% of that -clauses with a zero link in John Wycliffe’s sermons (late fourteenth century), and observes that the phenomenon was governed by the following syntactic factors: the removal of the clause subject; the particular preferences of the matrix verb; the existence of intervening elements between the matrix verb and the clause; and/or the nature of the clause initial element, whether a noun phrase, a pronominal or a conjunction ( Warner 1982 : 170–173). The most detailed corpus-based historical survey of zero/ that as complementizers, in our opinion, is Rissanen’s (1991) . The use of the Helsinki Corpus allows him to show that the definite rise of zero in English takes place from the second half of the sixteenth century to the early seventeeth century, being more frequent in speech-based text types (trials, sermons) or in texts representing the oral mode of expression (comedies). After reaching its peak at the end of this century, the use of the asyndetic construction diminishes drastically in the eighteenth, plausibly as a result of the pronouncements of prescriptive grammarians ( Rissanen 1991 ; 1999 : 284–285; see also Sundby et al. 1991 ; Finegan and Biber 1995 ; López Couso 1996 ; Görlach 2001 : 125–126).

In her study on “Finite complement clauses in Shakespeare’s English” ( 1990 ), Fanego also deals, among other aspects, with the use of that or the zero link in four plays by William Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet (1597), The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602), King Lear (1606) and The Winter’s Tale (1623). The percentages obtained from the analysis reach 79.49% for zero and 20.51% for that , with a tendency for the former to increase in prose texts (84.17%) and diminish in verse (68.53%), in connection with formality/informality ( Fanego 1990 : 143). A similar pattern is observed when one or more constituents separate the subject of the complement clause from its matrix predicate, with a percentage of 92.59% when no elements intervene in contrast to 66.66% whenever they appear ( Fanego 1990 : 144–146). Such a high level of occurrences of the zero link lead Fanego to conclude that “Shakespeare’s predilection for the zero-clause is idiosyncratic and seems to have no parallels in either earlier or later periods” ( Fanego 1990 : 147). Suárez Gómez (2000) has also studied the behaviour of that and zero in the Helsinki Corpus between 1420 and 1710. She thoroughly analyses a number of internal linguistic constraints, such as frequency and specificity of meaning of the matrix verb, grammatical context –finite vs. non-finite, ditransitivity, use of auxiliary verbs – and presence or absence of intervening material, among others. She focuses on text-types within the most informal end of the register cline: drama and private letters. Rates of zero are high in both, but a higher incidence is found in the former (67.2%) when compared to the latter (53.1%), thus confirming the tendency for the zero link to be used in text-types approaching the spoken language. Interestingly, she also notices that the use of one connector or the other often depends on the addressee: “in letters addressed to a person considered inferior by the writer, object complement clauses are introduced by the complementizer zero” ( Suárez Gómez 2000 : 187).

Some of the remarks by Rissanen (1991) , Fanego (1990) and Suárez Gómez (2000) point to the possibility that the diffusion of zero that -clauses followed the pattern of a typical change from below . In sociolinguistic terms, it is meant to be a “spontaneous process” ( Guy 1990 : 51) which is not consciously borrowed from external prestigious norms, as in the case of so-called changes from above . It appears in the vernacular in connection with internal linguistic factors, operating below the level of social awareness. Unlike changes from above , which in contemporary western societies tend to be initiated by members of the middle ranks, the leaders of changes from below usually belong to the upper working-classes ( Labov 1994 : 78).

There is not, to our knowledge, an empirical sociolinguistic corpus-based study of the phenomenon in the history of English. With this aim, the present paper studies the distribution of the syndetic and the asyndetic constructions between 1424 and 1681, covering the periods of the history of English known as late Middle English and early Modern English. Our aim is to shed some light on the sociolinguistic dimension of the phenomenon. As such, our paper is organised into five different sections. After this introduction, section two describes the scope and the corpus data upon which this study is based. Section three presents the distribution of this type of complementation in terms of the type of verb, while section four presents the models of social stratification for sociolinguistc research adopted in the analysis of early English and the results obtained when one of them is plotted on the relevant data. Finally, section five contains the conclusions.

2 Methodology

The present study deals with the use and distribution of that -clauses in the light of the following verbs, i.e. to know , to think , to say , to tell and to hope , which have been chosen in view of their high frequency in the corpus. According to some previous approaches to the topic ( Elsness 1984 ; Rissanen 1991 ; Suárez Gómez 2000 ), that -deletion is found to be more widespread in combination with high-frequency verbs rather than low-frequency matrices. Since the present study considers the sociolinguistic dimension of the phenomenon, it becomes a must for us to select high-frequency items as the ideal input to witness the difussion of the phenomenon in late Middle English and early Modern English. Following Rissanen’s classification ( 1991 : 274), these items come to represent three verb types, namely verbal expression ( say and tell ), non-verbal mental activity or state ( know and think ), and modal mental activity ( hope ).

The analysis is exclusively concerned with those object clauses in which the subordinate clause immediately follows the matrix verb since it is the context in which the alternative zero/ that is bound to occur, as shown in examples 1–2 below.

I suppose his sone woll say I have done hym some plesure in thes partes ( wyatt , 159.026.893). [2]

Trulie I doe verily thinke that I shall not goe out of my chamber this long time ( oxinde , I,182.109.1613).

Other positional combinations have been excluded insofar as “zero is impossible when the object clause precedes the main clause and that is practically impossible when the subject of the main clause begins with a push down element of the object clause” ( Rissanen 1991 : 274). Constructions like those shown in the examples below have also been disregarded from our analysis considering that the verb to think is not really followed by the subordinator that , which functions as a demonstrative or a relativiser instead:

I think that will bee best ( osborne , 55.025.1260).

[…] and that was it I think that spoiled it ( osborne , 106.046.2471).

The data used as source of evidence come from the Parsed Corpus of Early English Correspondence (text version, henceforth abbreviated as PCEEC ), a corpus especially compiled for sociolinguistic research, covering nearly three hundred years of the history of English, from 1410 to 1681. [3] The use of private letters is vital for historical sociolinguistic research for the following reasons. On the one hand, as non-anonymous texts, letters allow the reconstruction of psycho-biographical information about their authors and addressees and this favours a reproduction of the sociolinguistic variables that can be correlated with linguistic production: age, gender, education, professional background, social status, social network, mobility, etc. On the other hand, correspondence is accepted as the historical genre more likely to approach the oral vernacular, showing some characteristics that belong more to the spoken than to the written register: personal involvement, interaction or personal stance, among others ( Biber 1995 , Biber 2001 ; Biber and Finegan 1997 : 265–267). Letters, therefore, and especially those compiled in the PCEEC , can confidently be used in reconstructing the linguistic processes from the past, such as variation and change, that are often bred in this medium ( Nevalainen et al. 1996a ; Nevala and Palander-Collin 2005 ; Nevalainen 2007 ; Conde-Silvestre 2007 ; Palander-Collin 2010 ; Elspaß 2012 ). The present study makes use of the late Middle English and early Modern English collections of letters in the corpus. The former covers a span of eighty years (1420–1499), although we have focused on the four well-known collections of fifteenth century private correspondence, the Cely Letters , the Paston Letters , the Plumpton Letters and the Stonor Letters , which, with a total of 377,414 running words, afford specific data on a varied range of informants from the period 1424–1499. The early Modern English part of the corpus is divided into three subperiods: 1500–1569 (309,220 words), 1570–1639 (910,675 words), and 1640–1681 (555,415), amounting up to 1,775,310 words altogether ( Taylor and Santorini 2006 ). All collections of correspondence from each of these three subperiods have been analysed.

The automatic retrieval of the instances has been carried out with the use of a freeware concordance program, AntConc 3.2.2 . ( Anthony 2011 ). The process was not straightforward, however. Even though the use of the root of the verb prompted the automatic generation of many of the instances (i.e. hop *), other searches were needed on account of morphological variation (e.g. think ~ thinks ~ thinketh ~ thought ) and spelling inconsistency ( think ~ thynk ~ þink ~ þynk ). Once the complete set of instances was generated, further disambiguation was required so as to select the examples complying with the scope of our research.

3 Historical analysis

This section deals with the chronological distribution of that -clauses in late Middle English and early Modern English, by looking at the corpus instances in the period 1424–1681 while it also intends to shed some light on the likely influence of the type of verb on the phenomenon.

The material from the Parsed Corpus of Early English Correspondence provides us with a total of 7,048 instances of object clauses for this period, of which 4,458 are zero that -clauses and the remaining 2,590 instances appear with the complementizer that . The periods 1424–1499 and 1500–1569 amount to 1,695 and 755 examples of object clauses respectively, small figures if compared with the periods 1570–1639 and 1640–1681, with a total of 2,152 and 2,446 instances each. Table 1 below reproduces the distribution of instances in terms of period, type of verb, and whether a syndetic or an asyndetic construction is involved.

Distribution of zero/ that object clauses in PCEEC , 1424–1681 (absolute figures).

Historically speaking, these data allow us to trace the development of that and zero in late Middle and early Modern English. Figure 1 reproduces the occurrence of both constructions in the four periods under scrutiny, where the figures have been normalized to a text of 10,000 words for comparison. In line with Rissanen’s (1991 : 272–289) and Suárez-Gómez’s (2000 : 182) approaches, the syndetic construction is preponderant in the earliest periods (24.60), although the use of zero is not as low as expected (20.24) and by the mid-sixteenth century it already predominates over that clauses. The definite rise of zero in English is found to take place in the latter part of the sixteenth century, the moment in which it clearly separates from the syndetic construction, to such extent that it amounts to 16.71 occurences in the period 1570–1640, if compared with just 6.91 instances of the syndetic construction. This picture is also mirrored in the period 1640–1681 where the zero link is observed to gain a wider acceptance, almost tripling the number of that -clauses, as they amount to 32.12 and 11.91 occurrences, respectively. Interestingly enough, that -clauses undertake the opposite line of development since they begin to decrease in the late sixteenth century, coinciding with the spread of the zero link, perhaps as a result of a “stylistic shift towards less formal ways of writing” ( Rissanen 1991 : 286). The asyndetic construction seems to have gained ground considerably, to the point that it concomitantly produced a push shift which restricted the scope of that -clauses, setting aside other linguistic aspects like the nature of the subject, which undoubtedly could have also played a role.

Distribution of zero/ that object clauses in PCEEC , 1424–1681 ( nf ).

Distribution of zero/ that object clauses in PCEEC, S -curve 1424–1681 (%).

Figure 2 , reflecting the same patterning in percentage, positively shows that the diffusion of zero that -clauses in the early Modern period (from 1500 onwards) was moulded in the S -like shape accepted by many linguists as typically followed by changes diffusing in time. Different stages have recently been considered within S curves: (a) incipient, at the beginning i.e. below 15% of progress; (b) new and vigorous, once the lower central part of the curve is reached (15–40%) and diffusion is accelerated; (c) mid-range changes, which have got as far as the central part (41–65%) and start to lose momentum; (d) nearly completed (66–85%); and (e) completed, at the very end of the curve (over 85%) ( Labov 1994 : 79–83). Within this patterning, the diffusion of zero that -clauses – once it actuates and surpasses the connector that as a variant in competition – seems to have been well-advanced at mid-range in the second period, and nearly completed in the last two periods analysed, almost reaching the upper part of the S curve in 1681. Our data, therefore, corroborates Fanego’s findings as regards the use of zero in Shakespeare’s plays; rather than an idiosyncratic predilection for it, the playwright seems to be accommodating to a general trend already well-advanced in the vernacular.

Table 2 and Figure 3 reproduce the chronological distribution of the syndetic and the asyndetic constructions as regards the type of main verb. The figures have also been normalized to a text of 10,000 words.

Chronological distribution according to verb type, 1424–1681 ( nf ).

In the period 1424–1499 all verbs – except to tell – show slightly higher occurrences with the zero link than with that . Particularly outstanding is the number of object clauses with the main verb to say , reaching 12.6 and 11.89 with zero and that , respectively. This distribution contrasts with the other verb of saying, to tell , which shows a higher occurrence with that -clauses (8.24) than with zero (2.41). In his analysis Rissanen (1991 : 288) pointed out that the relative frequency of a particular verb may have a direct bearing on the use of the zero link as they “adopt the variation pattern only when they are well established in the language” (see also: Suárez Gómez 2000 : 187–188). Comparing the behaviour of say and tell in this respect may confirm this proposal, insofar as the former, which clearly favours the innovation, is notably more frequent than the latter. In fact, it is the very high figure for that -clauses after the main verb to tell which explains the preponderance of the syndetic construction over the asyndetic one. All in all, the analysis of private correspondence shows that zero that -clauses were already widespread in the latter part of Middle English, thus contradicting previous analyses – such as Warner’s (1982) based on texts written to be orally delivered, like the Wycliff sermons.

Chronological distribution according to verb type, 1500–1681 ( nf ).

The same pattern appears in the second period, 1500–1569, with a more balanced distribution of occurrences: that -clauses still predominate after the main verb to tell (1.39), but the zero link is widespread with to hope (0.35) and specially with the high frequency verb to think , which amounts up to 5.33 instances compared with 3.46 of the syndetic link. The behaviour of to say is also remarkable, because the conspicuous pattern of Middle English is here reversed, and the use of that is slightly ahead of zero (4.85 and 4.39, respectively).

The period 1570–1639, in turn, marks off a widespread use of zero with object clauses, therefore shedding clearer light on the intrinsic preferences for one type of construction depending on the type of verb. In this vein, the verbs to think , to hope and to say are found to favour the use of zero, as they more than double the occurrence of that : the verb to think , for instance, reaches 5.2 and 1.3 occurrences with both types of constructions. Finally, the period 1640–1681 further confirms this trend insofar as these three verbs ( to think , to hope and to say ) show higher instances of zero. The verb to think shows 9.63 and 1.18 occurrences with the asyndetic and the syndetic construction respectively, and similar rates are found with the verb to hope , with 9.05 and 0.99 instances, respectively. The verbs to know and to tell , on the other hand, do not reach the level of the other items in the adoption of the innovation, showing similar figures for both the syndetic and the asyndetic construction. The latter, for instance, is found to be the most conservative main verb, appearing with 5.05 and 4.6 occurrences of that and zero links respectively. This picture confirms Rissanen’s and Suárez-Gómez’s remark that the variation pattern is adopted differently depending on the type of verb.

4 Sociolinguistic analysis

4.1 sociolinguistic framework.

The rationale behind the historical sociolinguistic enterprise lies in the application of the well-known uniformitarian principle: the idea that languages varied in the same patterned ways in the past as they have been observed to do today ( Labov 1972 , Labov 1994 ; Conde-Silvestre 2007 ; Bergs 2012 : 81–82). In the context of this general principle –notwithstanding the difficulties inherent in the conceptualization of social structure, both in the present and, especially, in the past– it is a common assumption that social differences between speakers are among the driving forces for the diffusion of new linguistic elements among populations, and that “on the basis of what we know of the relationship between social order and language change in present-day societies, there is every reason to believe that similar phenomena existed in the past” ( Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 2003 : 139). Accordingly, in this section, the distribution of that -clauses and zero that -clauses in late Middle English and early Modern English is analysed in connection with the reconstructed social structure of the periods, in an attempt to confirm (i) the existence of social stratification for this variable, and, if such be the case, (ii) the social group or groups that lead the change in the different chronological stages of its diffusion, thus (iii) tracing the social direction of the change as actually diffusing from below , in sociolinguistic terms, or not.

In historical sociolinguistic research the risks of anachronism should also be carefully observed: the reconstruction of the external variable social structure being specially sentitive to them ( Bergs 2012 : 85–88). The concept of class itself, for instance, is a post-industrial revolution construct which can hardly be applied to the sociolinguistic analysis of pre-1800 texts. Kiełkiewicz-Janowick (2012 : 307) sensibly remarks in this respect:

In reconstructing the past, sociolinguists have to rely in concepts that will adequately describe historical realities and, most importantly, capture the complex relationship between language and society, without falsely assuming that for any historical period the relationships are comparable to those of the present-day. In other words, present-day description and understandings of social variables and relations should not be too readily taken as valid for historical periods. Instead, the meaning of a variable has to be recovered from the historical text that is the subject of linguistic analysis, as well as from the background writings of the historical period under study.

We wholly endorse this tenet and assume, for methodological purposes (i) that the criteria for assigning individuals to different social groups are necessarily different in different societies in different periods, and (ii) that the internal evidence of the texts analysed, together with the findings of social historians for given periods are key instruments in reconstructing social structures from the past for the purposes of historical sociolinguistic study ( Conde-Silvestre 2007 ; Kiełkiewicz-Janowick 2012 : 311–313). The idea is succintly expressed by Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg (2003 : 134): “[i]f one succeeds in singling out groups that are real, the emerging sociolects will also be real”.

In their seminal Historical Sociolinguistics. Language Change in Tudor and Stuart England ( 2003 ), these two authors discuss several proposals to reconstruct social stratification in late Middle and early Modern English. Out of the different models that they discuss, we have chosen a realistic one as the basis for our approach ( Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 2003 : 32–37, 136–137; see also Nevalainen 1996 ). It is a hierarchical model (reproduced in Table 3 ), which aims at reconstructing ranks. Anachronism is avoided by considering several factors in combination: property rights, social function, social evaluation, lifestyle, legal position, among others. In this way, the possibility that “people developed multiple identities, defining their own positions in terms of different models at the same time” is contemplated ( Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 2003 : 37). [4]

Social stratification in England in the 15th–16th centuries ( Nevalainen 1996 : 58).

It draws a fundamental distinction between nobility , gentry and non-gentry , together with a side division for the clergy . In addition to this, further subdivisions are found within some of these levels, particularly based on the evidence of titles and forms of address. For instance, in the group of the gentry and the clergy , upper and lower ranks may be established for knights, baronets (entitled sir or dame ) and bishops, who formed the upper gentry or upper clergy , and for squires, gentlemen (entitled master or mistress ) and ordinary clergymen, who may be considered part of the lower gentry or lower clergy . Similarly, a rank for the royalty is added at the very top of the chart, whilst at the same time further subdivisions are provided for the non-gentry , both urban (including merchants, craftsmen and artificers) and rural, although no definite evidence is available in this respect. Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg also propose a rank for the professional order, which includes doctors, lawyers, government officials, army officers and teachers, among others. The model is sensible, in sociolinguistic terms, insofar as it reconstructs the four intermediate orders or interior social groups which, following the curvilinear hypothesis, are relevant for the study of linguistic changes in progress ( Nevalainen et al. 1996b ; Labov 2001 : 31–33). In view of this universal sociolinguistic principle, we have concentrated on the evidence afforded by informants from the four intermediate levels: upper gentry, lower gentry, professionals and urban non-gentry, and have disregarded data from the very upper and lower ranks –nobility and rural non-gentry. In this way, the possibility of distortions derived from the urban vs. rural habitat of speakers is also avoided. Correspondents have been allocated to one rank or another both on the basis of the information extracted from the parameter codings given in the PCEEC as well as on external biographical data. [5]

The uniformitarian principle also allows historical sociolinguists to consider the role of women from the past in the diffusion of linguistic changes in progress. A universal sociolinguistic principle well known in present-day western societies is that, in changes from above women go ahead of males in the adoption of the prestige forms, and in changes from below they use higher frequencies of innovative forms than men do. This principle was formulated by Labov as the “gender paradox” and contemplates that the interaction between gender and social status tends to be noticeable once the diffusion of changes in progress is well advanced and “the stigmatized or prestige form is recognized and discussed in the speech community” ( Labov 2001 : 293; see also Labov 1990 ; Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 2003 ; Conde-Silvestre 2007 ; Kiełkiewicz-Janowick 2012 : 321). Confirmation of this principle in historical sociolinguistic research is difficult. Female leadership of changes from above was conditioned by their access to the “learned and literary domains of language use” ( Nevalainen 2006 : 208–209) and it is well known that access to education was limited to women from the high echelons of society. This is reflected in the structure of the Corpus of Early English Correspondence itself, with a mere 20% of letters by women, overwhelmingly from the upper ranks, so that “gender differentiation below the gentry is restricted” ( Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 2003 : 115). The scarcity of female correspondents from the other ranks also complicates the task of detecting their behaviour in connection with changes from below . Despite this difficulty, Suárez Gómez (2000 : 198–199), in her analysis of drama and private letters from the Helsinki Corpus , has noticed that women resorted more commonly to zero (54%) than to that (46%), while men preferred to use the latter (69.2%) more often than the zero-link (39.8%). In order to confirm these tendencies – checking the possibility that, in accordance with present-day practices, women behaved differently from men as regards the diffusion of zero that -clauses – a group of female informants from the upper gentry has also been considered in our analysis.

4.2 Sociolinguistic analysis: results

The results for late Middle English (1424–1499) confirm that the zero link is a typical change diffusing from below . As Figure 4 shows, the innovation was led in this period by members of the urban non-gentry (60.3%) and, at this stage, the zero link had already been accepted by the lower gentry (53%). The behaviour of the upper gentry and the professionals also complies with this characterization of zero that -clauses as a change from below , insofar as both groups present the lowest rates, 39% and 39.3% respectively. This is particularly symptomatic in the case of the professional order – especially lawyers – who would have been aware of the written norms enjoying overt prestige in the community and would, therefore, be reluctant to adopt a change coming from below . Finally, from a sociolinguistic point of view, women from the upper gentry (39.7%) do not seem to be ahead of men from the same group (39%), at least at this stage, when the use of that as a connector was still the norm (see also Calle-Martín and Conde-Silvestre 2014 : 127).

Zero that -clauses in late ME: 1424–1499 (%).

Figure 5 reproduces the distribution of zero that object clauses across three oustanding social groups participating in its diffusion in this period: the urban non-gentry, the lower gentry and the upper gentry (see appendix). There is no doubt of the advance of the construction with the main verbs to say and to think , which show a regular progress in the acceptance of the innovation down the social scale: 46.9%, 65.7% and 85.7% respectively for the upper gentry, the lower gentry and the urban non-gentry, in the case of to think , and 40.4%, 61.3% and 63.5% for the same groups in the case of the verb to say . Interestingly, the upper gentry shows higher occurrences of the zero link with the main verbs to hope and to know , although the total number of instances is low to establish a definite profile here. Finally, as regards the verb to tell , the innovation is not clearly adopted by members of any of the three groups, although an increasing cline is manifested down the social scale: from upper gentry (20.7%) down to urban non-gentry (39%).

Distribution of zero that -clauses across social groups and type of verb (1424–1499).

Data from the period 1500–1569 ( Figure 6 ) confirms some of the tendencies already detected in late Middle English. Despite the low input by informants from the urban non-gentry, they still appear as leaders of this change from below (66.7%), followed, as in the preceding period, by the lower gentry (58.3%). In the same vein, the information drawn from male members of the upper gentry shows that they still lagged behind the rest as regards the acceptance of this innovation (46.6%). The linguistic behaviour of members from the professional group is interesting: our data shows that their rates of acceptance of the innovation increased from 39.3% in late Middle English to 54.2% in 1500–1569, becoming the third group from the top. Absence of reliable data makes it difficult to interpret the linguistic behaviour of female informants from the upper gentry. They show the highest rate of occurrences (68.75%), but this evidence is only based on sixteen items and it is doubtful whether it points to a genuine case of female leadership or is just a mere distortion of the scarce available data. Still, if that were the case, a clear contrast with the late Middle English behaviour of the same group arises, insofar as their rates were at the time similar to those of the male members from the gentry. This could be taken as a clue that gender affiliation of changes in progress – both in the present and in the past – only manifests itself when they start to be noticeable in chronological and social terms – at mid-range in this case – although often gender advantage by women is independent of social embedding, as Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg (2003 : 131) have shown for a number of changes in Tudor and Stuart England. In the case of zero that -clauses, the results obtained in later periods may be useful to confirm or reject this hypothesis.

Zero that -clauses in early Modern English: 1500–1569 (%).

Distribution of zero that -clauses across social groups and type of verb: to say , to think and to know (1500–1569) (%).

Regarding progress of the innovation in connection to type of verb (see Figure 7 ), to say , to think and to know seem to have behaved as the anchor verbs for this innovation to develop in the period 1500–1569, especially among members of the professional group who, in comparison with the ME data, show the highest increase in the use of the zero link: 50.6%, 65.4% and 54.9% respectively. Avoidance of that with these verbs is also outstanding among the upper gentry, particularly in the case of to say (45.8%) and to think (55.75%). In contrast, the main verbs to hope and, especially, to tell are more resistant to this syntactic innovation (see appendix). The behaviour of each type of verb among the lower gentry and the urban non-gentry does not present a clear patterning, possibly due again to the scarcity of evidence available. The same applies to the verbs to hope and to tell , which, as a result, are not represented in Figure 7 .

In the period 1570–1639 the zero link spread from mid-range to the nearly complete stage, reaching the upper central part of the S curve representing diffusion of changes in time. This means that wider awareness among members of the community would have been expected. William Labov (2001 : 171) has studied the behaviour of changes from below in present-day American English in connection with socio-economic status and has noticed a tendency for them to remain stable or even decline among their natural leaders – the upper working classes –, while they spread faster among the middle classes, in accordance with widespread levels of acceptance. Zero in the early seventeenth century seems to have behaved like this ( Figure 8 ): it reaches 72.1% among the upper gentry, 66.7% among correspondents from the lower gentry and remains at 63.6% among the informants from the urban non-gentry. Even members of the professional orders increased their production of subordinate clauses without the connector that to 77.5%, thus showing that the original change from below was reaching a stage of acceptance by the speech community at large, which started to threaten the maintenance of the syndetic construction. Data by female informants from the upper gentry – reaching 83.6% in this period – could confirm the gender affiliation of this change, which, therefore, is only noticeable once the change in progress “has passed its incipient phase” ( Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 2003 : 130). If this is the case, gender affiliation would be expected to remain constant until the near completion of the change. As such, this is the historically expected behaviour of women that participate in changes from below : they show a conspicuous pattern of diffusion from the lower to the higher ranks, with female speakers leading the process before upper-rank male ones ( Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 2003 : 115–116). James Milroy and Lesley Milroy (1993) have proposed that women, rather than adopting forms which are already prestigious, by actually adopting innovations endow the affected forms with prestige and promote their subsequent spread. The extent to which the prominent pattern found in our data confirms this hypothesis for the past is an insoluble question (also Kiełkiewicz-Janowick 2012 : 323). [6]

Zero that -clauses: comparative of the periods 1570–1639 and 1640–1681 (%).

In general, data from the fourth period (1640–1681) points to the early phase of decline of the zero link. Rissanen (1991 , 1999 : 284–285) had already noticed that the phenomenon reached its peak in the seventeenth century and then plunged down in the eighteenth as a result of a prescriptive bias. Our results show a noticeable reduction in the repertoire of most groups when the periods 1570–1639 and 1640–1681 are contrasted ( Figure 8 ): from 72.1% to 63.4% among males of the upper gentry, from 66.7% to 63.5% among the lower gentry and from 77.5% to 61.6% among the professionals. Only female informants from the upper gentry seem to have kept a stable use of zero as complementizer in this period (84.1%). Data from the urban non-gentry is again scarce at this stage, but it points to the maintenance of the asyndetic structure among members of the group where it originated, with figures raising from 63.6% to 77.7%. This patterning is typical of a change from below that becomes thwarted once it has surpassed the mid-range stage in the S curve. A similar recessive behavior has been noticed for other changes in progress in Early Modern English –like third person singular -s (which later would catch on) or the relativizer the which – and confirms the historical validity of the observation that “for a new form to be generalized […] it had to be adopted by the upper strata” ( Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg 2003 : 150). Reluctance by male informants from the upper gentry could, in this case, be the reason behind the decline of the zero link in the first place. Our findings also show that in private correspondence – i.e. the genre most clearly approaching the vernacular – zero that -clauses started to decline in the late seventeenth century, much earlier than Rissanen had noticed in the multi-genred Helsinki Corpus . Incidentally, this observation could dissociate the decline of the asyndetic link from the expressed prescription by eighteenth-century grammarians and be taken as another clue that their pronouncements were often the sequel to changes already in progress, so that, as Tieken-Boon van Ostade (2006 : 270) has remarked, they were often sanctioning natural tendencies in the language.

Distribution of zero that -clauses across social groups and type of verbs (1570–1639) (%).

Figure 9 shows the behaviour of each type of verb for each group of informants at the mid-range to “nearly-completed” stages; in this case, to hope – which in the two previous periods was still resistant to the spread of the innovation – shows the highest rates, especially among the upper gentry (89.3%), the professionals (95.6%) and the urban non-gentry (100%). The main verb to tell , which had systematically lagged behind the rest in late Middle English and the first half of the sixteenth century, also shows a high increase in the third period analysed, with percentages of 75% for the urban non-gentry, 65.3% among the professionals and 48.4% among member of the upper gentry. A snowball effect, like the one recognized by Ogura and Wang (1996) in lexical diffusion, is clearly manifested in the last stages of progress of the asyndetic construction. Data for 1640–1681 in Figure 10 is also useful to detect the main verbs first affected by the recession of zero: a tendency for that to be omitted with the verbs to know and to say – which had led the pattern in previous periods – is noticeable among the lower gentry and the professionals, with percentages for to know declining from 66.7% in 1570–1639 to 22.2% in 1640–1681 among the former, and from 64.5% to 32% and from 66.7% to 63.1% for the same two groups for the latter.

Distribution of zero that -clauses across social groups and type of verbs (1640–1681) (%).

5 Conclusions

The interpretation of data from the Parsed Corpus of Early English Correspondence allows us to reach the following conclusions.

From a purely chronological perspective, we think that our analysis complements previous ones based on different materials. Data extracted from private correspondence – a genre generally thought to reflect the vernacular in the past – affords a new perspective, which may remain hidden when more formal text-types are dealt with. Particularly, we have detected higher rates of the zero link in late Middle English, when that was still the main complementizer, in comparison with earlier estimates, like Warner’s (1982) . Our data, however, confirms the early sixteenth century as the period when the use of the zero link overtook that , in line with Rissanen’s and Suárez-Gómez’s observations. The PCEEC also supports their proposal that the absence of a connector was well advanced in the seventeenth century. In this sense, we have been able to locate the zero link at the mid-range to nearly completed stages of diffusion along the S curve in the period 1570–1639 and throughout the seventeenth century when it reached a percentage of 70% in the corpus – in parallel to a decline of that . Previous studies, and present-day observation, confirm that the zero link declined in the eighteenth century, when its diffusion as a change in progress was thwarted, possibly due to the pronouncements of prescriptive grammarians against it. Our data has also shown that, in chronological terms, the decay of the asyndetic construction in private correspondence – i.e. in the vernacular – predates this calculation: it actually seems to have started to decline among all social ranks in the late seventeenth century. We believe that this could support the idea that prescriptive grammarians sometimes were just sanctioning general tendencies spreading in the language ( Tieken-Boon van Ostade 2006 : 270).