“I Have to Be All Things to All People”: Jim Jones, Nurture Failure, and Apocalypticism

- First Online: 07 August 2019

Cite this chapter

- James L. Kelley 3

778 Accesses

6 Citations

In 1978, Jim Jones and over 900 of his followers perished in what has been called “The Jonestown Massacre”. This study uses methods of psychobiography and objection relations theory to account for Jones’ lifelong ambivalence toward those to whom he acted as caregiver. The author proposes a psychological schema he names “nurture failure” to account for Jim Jones’ style of leadership, which mixed solicitude with violence in the context of a religious organization that promised to right all of society’s wrongs. The means by which this utopia was to be brought about became more and more extreme until the infamous murder/suicide shattered the dream for good. The study’s findings expand our understanding of the motivational dynamics that undergird religious leaders’ often Januslike relations to their followers.

The chapter’s title was uttered by Jim Jones sometime in the mid-seventies, as relayed by eyewitness Hue Fortson in an interview by Guinn ( 2017a , p. 225).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Andrews, N. J. (2002). ‘La Mère Humanité’: Femininity in the romantic socialism of Pierre Leroux and the Abbé A.-L. Constant. Journal of the History of Ideas, 63 (4), 697–716.

Google Scholar

Andrews, N. J. (2003). Utopian androgyny: Romantic socialists confront individualism in July Monarchy France. French Historical Studies, 326 (3), 437–457.

Article Google Scholar

Arendt, H. (1994/1965). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the banality of evil . Revised and enlarged edition. New York: Penguin. (Original revised edition of the work published in 1965).

Bebelaar, J., & Cabral, R. (2010). Timeline: And then they were gone. The Jonestown Report , 12. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=30368 . Accessed May 5, 2018.

Beck, D. (2005). The healings of Jim Jones. The Jonestown Report , 7. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=32369 . Accessed April 24, 2018.

Billington, J. H. (1980). Fire in the minds of men: Origins of the revolutionary faith . New York: Basic Books.

Bion, W. R. (1962a). A theory of thinking. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 63, 306–310.

Bion, W. R. (1962b). Learning from experience . New York: Basic Books.

Bion, W. R. (1970). Attention and interpretation . London: Karnac.

Black, A. (1990). Jonestown-two faces of suicide: A Durkheimian analysis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 20 (4), 285–306.

PubMed Google Scholar

Chidester, D. (2003). Salvation and suicide: Jim Jones, The Peoples Temple, and Jonestown (Rev ed.). Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press.

Christian, V. (1977). Minutes of people’s rally of December 20, 1977. RYMUR 89-4286, C-11-d-11 . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13200 . Accessed April 22, 2018.

Chung, A., & Government of Guyana. (1976). Lease of state land for mixed farming purposes to The Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/GuyanaLandLease.pdf . Accessed April 17, 2018.

Dawson, L. (1996). Who joins new religious movements and why: Twenty years of research and what have we learned? Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses, 25, 141–161.

Dawson, L. (2006). Comprehending cults: The sociology of new religious movements (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford.

Dieckman, J. (2006). Murder versus suicide: What the numbers show. The Jonestown Report , 8. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=31969 . Accessed April 20, 2018.

Dreyfus, H., & Taylor, C. (2015). Retrieving realism . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Elliott, A. (2015). Psychoanalytic theory: An introduction (3rd ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1943). The repression and return of bad objects (with special reference to war neuroses). British Journal of Medical Psychology, 19, 327–341.

Ferenczi, S. (1980/1928). The elasticity of psycho-analytic technique. In M. Balint (Ed.), Final contributions to the problems and methods of psycho-analysis (Vol. 3, pp. 87–102). New York: Bruner/Mazel. (Original work published in 1928).

Fondakowski, L. (2013). Stories from Jonestown . Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Freud, A. (1946). The ego and the mechanisms of defense . New York: International Universities Press.

Freud, S. (1999a/1915). Instincts and their vicissitudes. S.E. XIV (pp. 109–140). London: Vintage.

Freud, S. (1999b/1925). The question of lay analysis. S.E. XX (pp. 183–250). London: Vintage.

Freud, S. (1959/1920). Beyond the pleasure principle . New York: Bantam. (Original work published in 1920).

Gil, E. (1988). Treatment of adult survivors of sexual abuse . Rocklin, MD: Launch Press.

Guignon, C. (2017). Self-knowledge in hermeneutic philosophy. In U. Renz (Ed.), Self-knowledge: A history (pp. 264–279). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Guinn, J. (2017a). The road to Jonestown: Jim Jones and Peoples Temple . New York: Simon and Schuster.

Guinn, J. (2017b). Author Jeff Guinn: Sept. 2017 . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-RUaVUrFk24 . Accessed April 28, 2019.

Hall, J. R. (1987). Gone from the promised land: Jonestown in American cultural history . New Brunswick, NJ and Oxford: Transaction Books.

Harris, A. (1978). Peoples Temple had history of threats, violence. The Washington Post , 21 November. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1978/11/21/peoples-temple-had-history-of-threats-violence/e2783c9f-2822-434e-af87-51c225c6b3f9/?utm_term=.7a0c288da176 . Accessed May 5, 2018.

Hermans, H. J. M., & Kempen, H. J. G. (1993). The dialogical self: Meaning as movement . San Diego: Academic Press.

Jones, J. (1974a). Q612 transcript . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27492 . Accessed April 22, 2018.

Jones, J. (1974b). Q1059-1 transcript . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27331 . Accessed April 22 2018.

Jones, J. (1975). Q784 transcript . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27585 . Accessed April 30, 2018.

Jones, J. (1977a). Jim’s commentary about himself. RYMUR 89-4286-O-1-A1 . pdf. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/JJAutobio1.pdf . Accessed April 15, 2018.

Jones, J. (1977b). An untitled collection of reminiscences by Jim Jones . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13143 . Accessed April 2, 2018.

Jones, J. (1977c). Jim Jones interview with Nouvelle Observatoire. RYMUR 89-4286-C-12-d-1. pdf. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/NouvelleObservatoireInterview.pdf . Accessed May 7, 2018.

Jones, J. (1978a). Transcript of FBI tape Q273 . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27406 . Accessed April 22, 2018.

Jones, J. (1978b). FBI tape Q594 . MP3 audio file. https://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/nas/streaming/dept/scuastaf/collections/peoplestemple/MP3/Q594.mp3 . Accessed April 27, 2018.

Jones, J. (1978c). Q636 Transcript . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27508 . Accessed May 6, 2018.

Jones, J. (1978d). Q042 Transcript, by Fielding M. McGehee III . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=29079 . Accessed May 6, 2018.

Jones, L. (1977a). Index of stories written: Jimba’s life. RYMUR 89-4286-BB-18-Z . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=65439 . Accessed April 14, 2018.

Jones, L. (1977b). Stories from Jim Jones’ childhood. RYMUR 89-4286-EE-3 , Section DDDD. pdf. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/LynettaJonesEarly.pdf . Accessed April 14, 2018.

Jones, L. (1977c). Lynetta Jones interview #2. RYMUR 89-4286-EE-3 , Section TTT. pdf. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/LynettaInterview2.pdf . Accessed April 15, 2018.

Jones, L. (1977d). Index of stories written: Town Employment Solved. RYMUR 89-4286-BB-18-Z . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=65439 . Accessed May 8, 2018.

Jones, M. (1970). Marceline Jones letter to Jim Jones . https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=14093 . Accessed April 8, 2018.

Jones, S. (2005). Marceline/Mom. The Jonestown Report , 7. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=32388 . Accessed April 27, 2018.

Jonestown. (2018). Jonestown: The women behind the massacre [Documentary Film]. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvG8iKPfUkD6GM8lfiVamlQ . Accessed April 29, 2018.

Kelley, J. (2015). Nurture failure: A psychobiographical approach to the childhood of Jim Jones. The Jonestown Report , 17. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=64878 . Accessed April 14, 2018.

Kelley, J. (2016a). A note on Jim Jones, nurture failure, and ancient gnosis. The Jonestown Report , 18. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=67368 . Accessed April 14, 2018.

Kelley, J. (2016b). Orthodoxy, history, and esotericism: New studies . Dewdney, B.C.: Synaxis Press.

Kelley, J. (2017). “You don’t know how hard it is to be God”: Rev. Jim Jones’ blueprint for nurture failure. The Jonestown Report , 19. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=70768 . Accessed April 14, 2018.

Kilduff, M., & Javers, R. (1978). The suicide cult: The inside story of the Peoples Temple sect and the massacre in Guyana . New York: Bantam.

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. International Journal of Psycho-analysis, 27, 99–110.

Kőváry, Z. (2011). Psychobiography as a method. The revival of studying lives: Perspectives in personality and creativity research. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 7 (4), 739–777.

Kőváry, Z. (2013). Matricide and creativity: The case of two Hungarian cousin-writers from the perspective of contemporary psychobiography. The International Journal of Creativity & Problem Solving, 23 (1), 103–118.

Mantzavinos, C. (2016). Hermeneutics. Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy . https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hermeneutics/#Beginnings . Accessed April 20, 2018.

Mayer, C.-H., & Maree, D. (2017). A psychobiographical study of intuition in a writer’s life: Paulo Coelho revisited. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 13 (3), 472–490.

McAdams, D. P. (1985). Power, intimacy, and the life story: Personological inquiries into identity . Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press.

McAdams, D. P. (2008). Personal narratives and the life story. In O. John, R. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 241–261). New York: Guilford Press.

Moore, R. (1985). A sympathetic history of Jonestown: The Moore family involvement in Peoples Temple . Lewiston and Queenston: Edwin Mellen.

Moore, R. (2002). Reconstructing reality: Conspiracy theories about Jonestown. Journal of Popular Culture, 36 (2), 200–220.

Nugent, J. P. (1979). White night . New York: Rawson, Wade.

Orange, D. M. (2011). The suffering stranger: Hermeneutics for everyday clinical practice . London and New York: Routledge.

Polanyi, M. (1962). Personal knowledge: Towards a post-critical philosophy . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Polanyi, M. (2009/1966). The tacit dimension . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Original work published in 1966).

Rachman, A. W. (1997). The suppression and censorship of Ferenczi’s confusion of tongues paper. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 17 , 459–485.

Reiterman, T., & Dooley, N. (1977, August 7). Rev Jones: The power broker; Political maneuverings of a preacher man. San Francisco Examiner , 37.

Reiterman, T., & Jacobs, J. (1982). Raven: The untold story of the Rev. Jim Jones and his people . New York: Dutton.

Robbins, T. (2016). Religious mass suicide before Jonestown: The Russian Old Believers. In C. M. Cusack & J. R. Lewis (Eds.), Sacred suicide (pp. 29–54). London: Routledge.

Scheeres, J. (2011). A thousand lives: The untold story of hope, deception, and survival at Jonestown . New York: Simon & Schuster.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . New York: Basic Books.

Sewell, W. H. (1980). Work and revolution in France: The language of labor from the old Regime to 1848 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Silva, L. (2007). The Civil Rights Movement in Mendocino County, California? Jim Jones, Peoples Temple and the Civil Rights Movement reconsidered. The Jonestown Report , 9. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=33222 . Accessed May 4, 2018.

Strube, J. (2017). Socialism and esotericism in July Monarchy France. History of Religions, 57 (November), 197–221.

Sugarman, S. (2016). What Freud really meant: A chronological reconstruction of his theory of the mind . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, C. (2017). Converging roads around dilemmas of modernity. In C. W. Lowney II (Ed.), Charles Taylor, Michael Polanyi and the critique of modernity: Pluralist and emergentist directions (pp. 15–26). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Taylor, M. (1998). Jones captivated S.F.’s liberal elite: They were late to discover how cunningly he curried favor. SFGate , November 12. https://www.sfgate.com/politics/article/Jones-Captivated-S-F-s-Liberal-Elite-They-were-2979186.php . Accessed May 5, 2018.

Winnicott, D. W. (1982). Primary maternal preoccupation. Through paediatrics to psychoanalysis (pp. 194–204). London: Hogarth.

Winnicott, D. W. (2005). Playing and reality . Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. (Original work published in 1971).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

810 E. Apache, Norman, OK, 73071, USA

James L. Kelley

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to James L. Kelley .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Industrial Psychology and People Management, University of Johannesburg , Johannesburg, South Africa

Claude-Hélène Mayer

Institute of Psychology, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary

Zoltan Kovary

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Kelley, J.L. (2019). “I Have to Be All Things to All People”: Jim Jones, Nurture Failure, and Apocalypticism. In: Mayer, CH., Kovary, Z. (eds) New Trends in Psychobiography. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16953-4_20

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16953-4_20

Published : 07 August 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-16952-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-16953-4

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Your browser does not support HTML5 or CSS3

To best view this site, you need to update your browser to the latest version, or download a HTML5 friendly browser. Download: Firefox // Download: Chrome

Pages may display incorrectly.

- Case studies

Case Study A: The Peoples Temple And Jonestown

On November 18, 1978, over 900 people perished in the compound of the Peoples Temple in Guyana, South America. Many of the dead had apparently willingly drunk a poisoned fruit-punch at the command of the Rev. Jim Jones, the group’s leader. However, many of the dead were children convinced (or perhaps tricked or forced) to drink by their parents or other adults, and a few people appear to have been forced to drink at gunpoint (a handful died by gunshot). This remains one of modern history’s largest murder-suicide events, and religion was one of its central components.

The Peoples Temple emerged in the 1950s in Indianapolis, Indiana, as a fairly routine Protestant Christian sect. Perhaps its distinguishing feature, especially in its early years, was its strong pursuit of racial integration, a pointed departure from the prevailing racist segregationism of the day. To the very end, the Peoples Temple membership consisted of a thorough mix of white and black followers who worshipped, worked, and lived side-by-side.

Over time, Jim Jones added to the group’s basic evangelical and mildly Pentecostal Protestantism with an increasingly idiosyncratic set of teachings including apocalyptic expectations of a nuclear holocaust. In 1965 Jones moved the group to northern California, where for a time they were welcomed, even celebrated for their anti-racist ways. However, eventually the group was suspected of abusive behaviors toward its members, as well as of committing financial fraud. Amid growing suspicion, Jones decamped the group to the northern region of Guyana where they built up a sizeable compound with extensive agricultural holdings, dormitories, and large meeting halls. The dual goals of the group at this point were to show the world an example of a socialist utopia and survive the expected arrival of Armageddon.

Jones grew increasingly erratic and authoritarian, subjecting followers to harsh punishments and public humiliations for infraction of a growing list of rules, especially for any hints of disloyalty. It appears that some members may have been restrained from leaving, and rumors started to trickle out of tensions and abuses in the community. These reports prompted a visit from Leo Ryan, a U.S. Congressman from the Peoples Temple’s old home of California. Ryan and his entourage arrived on November 17, 1978, and toured the compound. While there seem to have been some tensions between Jones and Ryan, overall the visit largely passed without major incident, until some of Jones’ followers ambushed Ryan’s group as they prepared to depart from a nearby air field. Ryan and four others were shot dead.

Expecting that this assault would prompt intervention and retaliation from U.S. authorities, Jones activated a previously-rehearsed plan for mass suicide. A chilling tape recording of his final, 45-minute speech includes his admonishments to remain calm and his command to drink the poison (the recording is linked below). The resources below help fill in many details of this complicated case, from Jones’ difficult childhood, to his developing religious teachings, to life in the Jonestown compound, and specifics of the group’s final, tumultuous day. The list of resources is followed by suggestions for employing ideas from the book in making sense of this case.

A good start

- A brief overview from the History Channel, with embedded links for more information:

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/mass-suicide-at-jonestown

- A good overview documentary video,“Great Crimes and Trials: The Jonestown Massacre” (25 min., semi-graphic):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FL2eE7914Pk

Digging deeper

The Peoples Temple/Jonestown have been studied extensively. Here is a sampling of some of the better research and reflection available:

- The (in)famous recording of the last speech by Jim Jones, including his orders to the group to kill themselves. Officially known as “FBI Q 042,” it is often called “the Jonestown Death Tape” (45 min.):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jr9WnQxZu64

- First of a multi-part documentary video from ABC News from 20 years after the events (the remaining segments can also be found on YouTube):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0B1sMfxWYw

- A thoughtful scholarly study by one of the leading experts on the group:

Moore, Rebecca. “Rhetoric, Revolution, and Resistance in Jonestown, Guyana.” Journal of Religion and Violence 1, no. 3 (2013): 303–21. Available at: https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=67381

- An updated version of a classic book presenting religious studies analysis of the Peoples Temple:

Chidester, David. Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown . Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2003 [1991].

- A book-length study form the same author as the above article:

Moore, Rebecca. Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple . Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2009.

- A classic essay from a giant of religious studies, seeking to interpret the Jonestown events in light of other episodes of religious violence:

Smith, Jonathan Z. “The Devil in Mr. Jones,” in Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1982), 102–20.

- A welcome collection of studies of the role of race in the Peoples Temple:

Moore, Rebecca, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, eds. Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America . Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004.

- The Peoples Temple and Jonestown considered in the context of apocalyptic “cults” and “new religious movements”:

Wessinger, Catherine Lowman. How the Millennium Comes Violently: From Jonestown to Heaven’s Gate . New York: Seven Bridges, 2000.

Applying the book to this case

- Ch. 3 considers the thought of Marx in relation to religious violence. The Peoples Temple’s commitment to racial equality might show some affinities with Marxist critiques of social and material injustice. Do these kinds of critiques illuminate the Peoples Temple case, including its violent end? Does the Peoples Temple add any complexity to thinking about critiques of injustice and the ways they may participate in violence?

- Victor Turner (ch. 5) focuses attention on “liminal” states outside of established social structures. The Peoples Temple appears to have sought to generate a strong sense of “communitas” among its members, and the group’s move to Guyana and the establishing of Jonestown could be seen as deliberately entering a “liminal” state. How specifically did they pursue these states, and how might those efforts have contributed to the violence of the Jonestown murder-suicide?

- The Peoples Temple is often described as a “cult” (or a “new religious movement”). Ch. 8 explores the meaning of this term in the wider context of the sociology of religion and the ways social formation of religious communities and organizations can affect religious violence (see esp. pp. 163–69). What light is shed on this case by consideration of these social dynamics?

- For instance, the Peoples Temple seems to share some features of both a “sect” and a “cult,” including in its relationship to the wider society: a sect tends to offer a doctrinal and/or moral critique of the status quo, as the Peoples Temple seems to have done regarding race. However, the group may have shifted in the direction of a “cult” as Jim Jones developed more idiosyncratic teachings and a more self-centered leadership style. How might any of these factors have contributed to the group’s violent end?

- Ch. 9 presents a set of “building blocks” of religious traditions that can readily contribute to religious violence. Apocalyptic expectations appear to have been a significant aspect of the Peoples Temple teachings; how might these contribute to violence (see pp. 192–3). What other categories discussed in the chapter (listed on p. 175) might be elements of the Jonestown case?

- Review the typology of violence discussed in ch. 1 and the appendix, and consider whish specific forms of violence have occurred as part of the Peoples Temple murder-suicide. Self-directed harm, such as suicide, raises complex questions, since the perpetrator and target of violence might be one and the same, and the harm might be intended and desired by the target. Also, how might the prevalent issues of self-defense and vengeance play out in this case? What other specific forms of violence appear in this case?

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms & Conditions

© 2024 Informa UK Ltd trading as Taylor & Francis Group

By using this website, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Cookies Policy .

Before the tragedy at Jonestown, the people of Peoples Temple had a dream

Emerita Professor of Religious Studies, San Diego State University

Disclosure statement

Rebecca Moore does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

When people hear the word “Jonestown,” they usually think of horror and death.

Located in the South American country of Guyana, the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project was supposed to be the religious group’s “promised land.” In 1977 almost 1,000 Americans had moved to Jonestown, as it was called, hoping to create a new life.

Instead, tragedy struck. When U.S. Rep. Leo J. Ryan of California and three journalists attempted to leave after a visit to the community, a group of Jonestown residents assassinated them, fearing that negative reports would destroy their communal project.

A collective murder-suicide followed, a ritual that had been rehearsed on several occasions.

This time it was no rehearsal. On Nov. 18, 1978, more than 900 men, women and children died, including my two sisters, Carolyn Layton and Annie Moore, and my nephew, Kimo Prokes.

Photojournalist David Hume Kennerly’s aerial photograph of a landscape of brightly clothed lifeless bodies captures the magnitude of the disaster of that day.

In the more than 40 years since the tragedy, most stories, books, films and scholarship have tended to focus on the leader of Peoples Temple, Jim Jones, and the community that his followers attempted to carve out of the dense jungles of northwest Guyana. They might highlight the dangers of cults or the hazards of blind obedience .

But by fixating on the tragedy – and on the Jones of Jonestown – we miss the larger story of the Temple. We lose sight of a significant social movement that mobilized thousands of activists to change the world in ways small and large, from offering legal services to people too poor to afford a lawyer, to campaigning against apartheid.

It is a disservice to the lives, labors and aspirations of those who died to simply focus on their deaths.

I know that what happened on Nov. 18, 1978 doesn’t tell the complete story of my own family’s involvement – neither what happened in the years leading up to that dreadful day, nor the four decades that followed.

The impulse to learn the whole story prompted my husband, Fielding McGehee, and me to create the website Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple in 1998 – a large digital archive documenting the movement primarily in its own words through documents, reports and audiotapes. This, in turn, led the Special Collections Department at San Diego State University to develop the Peoples Temple Collection .

The problems with Jonestown are self-evident.

But that single event shouldn’t define the movement.

The Temple began as a church in the Pentecostal-Holiness tradition in Indianapolis in the 1950s.

In a deeply segregated city, it was one of the few places where black and white working-class congregants sat together in church on a Sunday morning. Its members provided various kinds of assistance to the poor – food, clothing, housing, legal advice – and the church and its pastor, Jim Jones, gained a reputation for fostering racial integration.

Investigative journalist Jeff Guinn has described the ways early incarnations of the Temple served the people of Indianapolis. The income generated through licensed care homes, operated by Jim Jones’ wife, Marceline Jones, subsidized The Free Restaurant, a cafeteria where anyone could eat at no cost.

Church members also mobilized to promote desegregation efforts at local restaurants and businesses, and the Temple formed an employment service that placed African-Americans in a number of entry-level positions.

While it’s the kind of action some churches engage in today, it was innovative – even radical – for the 1950s.

In 1962, Jones had a prophetic vision of a nuclear catastrophe, so he urged his Indiana congregation to relocate to Northern California.

Scholars suspect that an Esquire magazine article – which listed nine parts of the world that would be safe in the event of nuclear war, and included a region of Northern California – gave Jones the idea for the move.

In the mid-1960s, more than 80 members of the group packed up and headed west together.

Under the guidance of Marceline, the Temple acquired a number of properties in the Redwood Valley and established nine residential care facilities for the elderly, six homes for foster children, and Happy Acres, a state-licensed ranch for mentally disabled adults. In addition, Temple families took in others needing assistance through informal networks.

Sociologist of religion John R. Hall has studied the various ways the Temple raised money at that time. The care homes were profitable, as were other moneymaking ventures; there was a small food truck the Temple operated, and members were also able to sell grapes from the Temple’s vineyards to Parducci Wine Cellars.

These fundraising schemes, along with more traditional donations and tithes, helped underwrite free services.

It was at this time that young, college-educated white adults began to trickle in. They used their skills as teachers and social workers to attract more members to a movement they saw as preaching the social gospel of redistribution of wealth.

My younger sister, Annie, seemed to be drawn to the Temple’s ethos of diversity and equality.

“There is the largest group of people I have ever seen who are concerned about the world and are fighting for truth and justice for the world,” she wrote in a 1972 letter to me . “And all the people have come from such different backgrounds, every color, every age, every income group.”

But the core constituency comprised thousands of urban African-Americans, as the Temple expanded south to San Francisco, and eventually to Los Angeles.

Frequently depicted as poor and dispossessed, these new African-American recruits actually came from the working and professional classes: They were teachers, postal clerks, civil service employees, domestics, military veterans, laborers and more.

The promise of racial equality and social activism operating within a Christian context enticed them. The Temple’s revolutionary politics and substantial programs sold them.

Regardless of the motives of their leader, the followers wholeheartedly believed in the possibility of change.

During an era that witnessed the collapse of the civil rights movement, the decimation of the Black Panther Party and the assassinations of black activists, the group was especially committed to a program of racial reconciliation.

But even the Temple couldn’t escape structural racism, as “ eight revolutionaries ” pointed out in a letter to Jim Jones in 1973. These eight young adults left the organization, in part, because they watched new white members advance into leadership ahead of experienced, older black members.

Nevertheless, throughout the movement’s history, African-Americans and whites lived and worked side by side. It was one of the few long-term experiments in American interracial communalism, along with Father Divine’s Peace Mission Movement , which Jim Jones emulated.

Members saw themselves as battling on the front lines against colonialism, as they listened to guests from Pan-African organizations and from the recently deposed Marxist Chilean government speak in their San Francisco gatherings. They joined coalition groups that were agitating against the Bakke case , which ruled that race-based admissions quotas were unconstitutional, and demonstrating in support of the Wilmington Ten , 10 African Americans who were wrongfully convicted of arson in North Carolina.

Members and nonmembers received a variety of free social services: rental assistance, funds for shopping trips, health exams, legal assistance and student scholarships. By pooling their resources, in addition to filling the collection plates, members received more in goods and services than they might have earned on their own. They called it “ apostolic socialism .”

Living communally not only saved money, but also built solidarity. Although communal housing existed in Redwood Valley, it was greatly expanded in San Francisco. Entire apartment buildings in the city were dedicated to accommodating unrelated Temple members – many of them senior citizens – who lived with and cared for one another.

As early as 1974, a few hardy volunteers began clearing land for an agricultural settlement in the Northwest District of Guyana , near the disputed border with Venezuela.

While the ostensible reason was to “provide food for the hungry,” the real reason was to create a community where they could escape the racism and injustice they experienced in the United States.

Even as they toiled to clear hundreds of acres of jungle, build roads and construct housing, the first settlers were filled with hope, freedom and a sense of possibility.

“My memories from 1974 till the beginning of ‘78 are many and full of love, and to this day they still bring tears to my eyes,” recalled Peoples Temple member Mike Touchette , who was working on a boat in the Caribbean as the deaths were occurring. “Not only the memories of building of Jonestown, but the friendships and camaraderie we had before 1978 is beyond words.”

But Jim Jones arrived 1977, and an influx of 1,000 immigrants – including more than 300 children and 200 senior citizens – followed. The situation changed. Conditions were primitive, and though the residents of Jonestown were no worse off than their Guyanese neighbors, it was a far cry from the lives they were used to.

The community of Jonestown is best understood as a small town in need of infrastructure, or, as one visitor described it , an “unfinished construction site.”

Everything – sidewalks, sanitation, housing, water, electricity, food production, livestock care, schools, libraries, meal preparation, laundry, security – had to be developed from scratch. Everyone but the youngest of children needed to pitch in to develop and maintain the community.

Some have described the project as a prison camp .

In several respects that is true: People weren’t free to leave. Dissidents were cruelly punished.

Others have described it as heaven on earth .

Undoubtedly it was both; it depends on who – and when – you ask.

But then there is the final day, which seems to erase all the promise of the Temple’s utopian experiment. It’s easy to identify the elements that contributed to the final tragedy: the anti-democratic hierarchy, the violence used against members, the culture of secrecy, the racism, and the inability to question the leader.

The failures are apparent. But the successes?

For years, Peoples Temple provided decent housing for hundreds of church members; it ran care homes for hundreds of mentally ill or disabled individuals; and it created a social and political space for African-Americans and whites to live and work together in California and in Guyana.

Most importantly, it mobilized thousands of people yearning for a just society.

To focus on the leader is to overlook the basic decency and genuine idealism of the members. Jim Jones would have accomplished nothing without the people of Peoples Temple. They were the activists, the foot soldiers, the letter writers, the demonstrators, the organizers.

Don Beck , a former Temple member, has written that the legacy of the movement is “to cherish the people and remember the goodness that brought us together.”

In the face of all those bodies, that’s a difficult thing to do.

But it’s worth a try.

- Social justice

- Christianity

- Social movements

- Mass murder

- Collections

Compliance Lead

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

The Psychology Behind The Jonestown Massacre Finally Explained

On November 18, 1978, more than 900 men, women, and children, died by suicide and murder at the Jonestown settlement in Guyana. As reported by History , the suicides and murders were committed under the direction of Reverend Jim Jones, who was the leader of the Peoples Temple religious sect.

Psychology Today reports, "suicide is usually an act of lonely desperation, carried out in isolation or near isolation." However, mass suicide, especially of the scale that happened at Jonestown, is extraordinarily rare.

For the last 43 years, people have questioned how one man could convince more than 900 others to knowingly kill their children and commit suicide. In addition to determining how and why the Jonestown Massacre happened, Psychologists want to make sure it never happens again.

As reported by The Washington Post , Jim Jones opened his first church in 1953, at the age of 22. Although he was not yet formally ordained, he gained respect, and a following, for his dedication to racial equality and human rights.

In the early 1960s, Jones was ordained as a Disciples of Christ minister and continued to build his following at The Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church. However, by 1965, he became obsessed with concerns about a nuclear war. He eventually convinced his congregation to move with him to California, where he believed they would all be safe if a nuclear war occurred.

By the late 1970s, History reports some sources estimated Reverend Jim Jones had up to 20,000 followers.

What actually happened in Jonestown?

In 1974, Reverend Jim Jones signed a lease for 27,000 acres of land in Guyana. History reports Jones continued to lead his church in California. However, he sent a group of his followers to Guyana to prepare the land for farming and to establish a compound.

In 1977, Jim Jones and more than 1,000 of his followers moved to Guyana to live in the newly established Jonestown settlement. A little more than one year later, more than 900 of those followers were dead. Some survivors managed to escape.

History reports the Jonestown Massacre was prompted by a congressman visiting the compound. Amid reports of ongoing abuse, the congressman traveled to the compound to check the welfare of its residents. During the visit, several members asked the congressman to help them leave. However, the group was ambushed on their way back to the plane and four people were killed.

Within hours, Jones convinced his followers to poison their children and to take their own lives. As reported by History, Jones told them they were about to be attacked in retaliation for the ambush.

Psychologists believe Reverend Jim Jones used mental and physical abuse, blackmail, humiliation, and threats to break his followers down and ultimately convince them he was their savior. Those who weren't convinced were simply too frightened to leave.

As reported by Psychology Today , Jones routinely forced his followers to sign blank power of attorney forms and false confessions to crimes, including child molestation, to prove their loyalty to him and the church.

How Jim Jones gained control of his followers

As reported by Psychology Today , Jones also used degradation and humiliation to exert control over his followers. Although couples were prohibited from having sex with each other, they were forced to have sex with Jones or other members while their spouses were forced to watch. He also humiliated his followers by making them strip naked and criticizing their bodies in front of others.

Unfortunately, children were not exempt from Reverend Jim Jones' abuse. Children were routinely beaten, "tortured with electric shocks," and left in the bottom of an abandoned well as punishment. There are also reports that they were sexually abused.

Psychology Today reports Reverend Jones used abuse and humiliation to weaken his followers' willpower. However, the threats of blackmail ensured they would remain under his control.

In addition to the blackmail, Jones routinely threatened to have any defectors killed by his "angels." Not only were many followers afraid to leave, but they were also afraid of what might happen to any loved ones they left behind.

As reported by Psychology Today, Jonestown ultimately became "a twilight-zone reality in which people pretended to be enjoying a Utopian existence while living in constant fear for their lives."

With little willpower left, Jim Jones' followers were susceptible to his assertions that he was, in fact, God, and that he had their best interests in mind. He also convinced them they would be transported to another planet, where they would live in paradise if they ever died.

Dr. David Godot

Clinical Psychologist

Jonestown and The Social Psychology of Accepted Truth

Everybody “knows” what happened in Jonestown, Guyana in 1978. At the behest of their charismatic leader, all the members of the Peoples Temple religious cult—the residents of Jonestown—“lined up in a pavilion in front of a vat containing a mixture of Kool-Aid and cyanide” and “drank willingly of the deadly solution” (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, 2005, pp.4-5). That citation is taken from a popular Social Psychology textbook, and is a resounding demonstration of the phenomenon that this paper will attempt to explore: you see, the authors of that textbook feel so secure in their knowledge of the events surrounding the deaths in Jonestown that they feel no need to provide a reference for it. It is entered into the student consciousness as common knowledge. The fact that the popularly-accepted truth that Aronson, et al are parroting in this example is plainly false is almost beside the point, although this paper will provide a brief examination of some of the evidence which contradicts that accepted truth. The problem is much broader than the debunking of a single myth, and demands that some very important and difficult questions receive systematic evaluation: how is it that entire populations “know” things that contradict all available evidence, and what can be done to mediate this effect?

In considering the events of Jonestown, we might do well to start out by questioning our own credulity. What do we actually know about Jim Jones and The Peoples Temple, and from what sources? Does our understanding of the events stand up to logical scrutiny? Furthermore, as social psychologists, let us ask ourselves this very important question: In light of our current understanding of the power of social influence, do we believe it is plausible that 900 people took their own lives, simply because they were asked to? If so, are we willing to believe that we would behave in the same manner if subjected to similar social influences? As Aronson, et al (p.14) point out in their discussion of The Peoples Temple, “it is tempting and, in a strange way, comforting to write off the victims as flawed human beings. Doing so gives the rest of us the feeling that it could never happen to us.” The problem is that they use this rationale to imply that people would behave in a way that no empirical evidence has verified. Theirs is an argument from paranoia, having arisen out of its conclusion and stating as truism that which is both counterintuitive and unsupported. The idea here is not merely to pick on the authors of a textbook, but to pinpoint a mindset that is pervasive enough that it remains largely invisible in our society.

As Eileen Barker, the President of the Society for Scientific Study of Religions, has noted, “the belief in irresistible and irreversible mind-control techniques is so widespread that the democratic societies of Western Europe and North America appear to give ‘permission’ to citizens to carry out criminal attacks on someone merely on the grounds that he or she is a member of an unpopular religious group” (1996). Her research, however, does not support this belief. Furthermore, although there is very little research into the matter aside from her own, a small number of academics have taken up careers as “expert witnesses,” providing fervent yet unsubstantiated support to the idea. In the case of Jonestown, that man’s name was Dr. Hardat Sukhdeo. Jim Hougan writes:

Dr. Sukhdeo is, or was then, “an anti-cult activist” whose principal interests (as per an autobiographical note) are “homicide, suicide, and the behavior of animals in electro-magnetic fields.” His arrival in Jonestown on November 27, 1978 came only three weeks after he had been named as a defendant in a controversial “deprogramming” case. It is not entirely surprising, then, that within hours of his arrival in the capital, Dr. Sukhdeo began giving interviews to the press, including the New York Times, “explaining” what had happened.

Jim Jones, he said, “was a genius of mind control, a master. He knew exactly what he was doing. I have never seen anything like this…but the jungle, the isolation, gave him absolute control.” Just what Dr. Sukhdeo had been able to see in his few minutes in Jonestown is unclear. But his importance in shaping the story is undoubted: he was one of the few civilian professionals at the scene, and his task was, quite simply, to help the press make sense of what had happened and to console those who had survived. He was widely quoted, and what he had to say was immediately echoed by colleagues back in the States. (1999)

The idea that a charismatic individual can completely overtake the decision-making power of random victims and use their mindless bodies to do his bidding even to the point of inciting a uniform mass suicide, with 600 adult individuals willfully—even joyously—killing themselves and their children is startling, anxiety-provoking, ambiguous, and enticing. It is, in short, good material for conversation. It is precisely the stuff of which rumors, gossip, and urban legends are made (Guerin & Miyazaki, 2006). It is not a realistic causal evaluation of plausible events, but is rather a good example of what is called “magical thinking,” the type of credulity typically associated with the pre-rational thought processes of young children. However, research indicates that as they mature, people tend to abandon magical beliefs in word only. “Indeed, in their general patterns of judgments, actions and justifications, adult participants seem to be prepared to respect both scientific and non-scientific causal explanations to an equal extent” (Subbotsky, 2001). By sharing rumors with amongst ourselves in the course of conversation and by receiving fantastical official versions through the media, this tendency toward fascination becomes manifest. Wherever mass media is the source of the information, we must also take into account the social component of individual judgement, which is a considerable influence (Joslyn, 1997). For, as McLuhan noted, sociality of mass media is profoundly experienced—when we watch television, we are influenced not only by the content of the programming but also by the knowledge that a large number of our peers are watching as well (1964).

This may help to explain why so many of us have accepted a version of the Jonestown events that are implausible. In addition to the psychological discrepancies we have already noted, let us observe that death by cyanide poisoning is a painful and grotesque affair. Central nervous system signals become scrambled, causing both voluntary and involuntary muscular systems to spasm violently. Twisted, contorted limbs and a terrible grimace known as cyanide rictus are typical of this cause of death (Jaffe, 1983 as cited in Judge, 1985). However, none of the more than 150 available photographs of the victims reveal these symptoms. Furthermore, the victims were laid out in neat rows, and some of the closer range photos reveal drag marks on the ground, indicating that the corpses were arranged in this way after their death. Based on an investigation that included the testimony of Dr. Leslie Mootoo, the top Guyanese pathologist who served as Chief Medical Examiner for the case and who personally examined many of the Jonestown bodies, a Guyanese grand jury concluded that only two of the 913 dead had committed suicide. Dr. Mootoo found fresh needle marks near the left shoulder blades of the vast majority of the victims he inspected, with some others exhibiting gunshot wounds or strangulation as the likely cause of death. The gun with which Jones himself is purported to have shot himself in the head was found lying nearly 60 feet from his body (Judge, 1985; Hougan, 1999; Schnepper, 1999). It is evident, then, that the supposed “mass suicide” was actually a massacre—but who would slaughter nearly a thousand U.S.citizens, nearly all of whom were African Americans, women, and underprivileged children?

There is a substantial body of evidence connecting Jim Jones and his Peoples Temple to the covert operations of the United States government intelligence community, not least of which are his longstanding ties with CIA operative Dan Mitrione, his adeptness at infiltrating and exploiting local governments, the suspicious circumstances surrounding the assassination of Congressman Leo Ryan in Guyana the evening before the massacre (whose escort was a high-ranking CIA officer), and the enormous cache of psychiatric drugs found on the premises of the Peoples Temple colony—all of the type being experimented with at that time under the CIA’s MKULTRA mind-control project (Judge, 1985; Hougan, 1999). Additional evidence of U.S.government involvement in the affair involves the self-proclaimed “anti-cult activist” psychiatrist Dr. Sukhdeo, whose own attorney has stated that his trip to Guyana was funded by the U.S. State Department.

The possibility exists that Jonestown, Guyana was indeed one of the many government experiments in mind-control of the 1970s. If it is, however, it would seem that the experimental subjects included not only the members of the Peoples Temple, but also the public at large. Regardless of intention, we have here a clear case of a governmental bureaucracy producing and disseminating misinformation for one reason or another, and the public—including the scientific community—accepting it without question, repeating it with authority, and even using it as a basis for social theory. The danger that this presents to free society is enormous, and the need for a concerted scientific effort to understand its limits and to develop safeguards is equally enormous.

- Aronson, Elliot, Wilson, Timothy D., & Akert, Robin M. (2005). Social Psychology, 5 th Edition .New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Barker, Eileen (1996). “The Freedom of the Cage.” Society, Vol. 33 Issue 3, pp53-59.

- Guerin, Bernard & Miiyazaki, Yoshihiko (2006). The Psychological Record, Vol. 56, pp.23-24.

- Hougan, Jim (1999). ‘‘Jonestown. The Secret Life of Jim Jones: A Parapolitical Fugue.’’ Lobster, Vol. 37, pp.2-20.

- Joslyn, Mark R. (1997). Political Behavior, Vol. 19 No. 4, pp.337-343.

- Judge, John (1985). ‘‘The Black Hole of Guyana: The Untold Story of the Jonestown Massacre.’’ In Keith, Jim (Ed.), Secret and Suppressed: Banned Ideas and Hidden History .Portland,OR: Feral House.

- McLuhan, Marshall(1964). Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Schnepper, Jeff A. (1999). “Jonestown Massacre: The unrevealed story.” USA Today Magazine, Vol. 127 Issue 2644, p26.

- Subbotsky, Eugene(2001). British Journal of Developmental Psychology, Vol. 19 , pp.23-46.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

One thought on “Jonestown and The Social Psychology of Accepted Truth”

Hi! I was surfing and found your blog post… nice! I love your blog. 🙂 Cheers! Sandra. R.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Jonestown--two faces of suicide: a Durkheimian analysis

Affiliation.

- 1 American Ethnic Studies Department, University of Washington, Seattle 98195.

- PMID: 2087766

This paper takes exception to much of the literature on Jonestown. The authors of this literature claim that an explanation of the mass suicide in Jonestown requires an understanding of how its residents came to a common consciousness. Such an analysis implies that the residents of Jonestown died for essentially the same reason. This paper, using Durkheim's typology of suicides, demonstrates that the residents of Jonestown died for very different reasons and that two types of suicide occurred simultaneously on November 18, 1978: altruistic and fatalistic. Some of the residents of Jonestown died because they put the group above the self; they committed altruistic suicide. The majority, however, died for fatalistic reasons. Jonestown in fact had become a hopeless, demeaning, and antagonistic environment. The analysis here suggests caution to those who assume that a mass suicide is necessarily a homogeneous event.

- Emigration and Immigration

- Mass Behavior*

- Religion and Psychology*

- Social Conformity*

- Suicide / psychology*

- United States / ethnology

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Durkheim's Sociological Perspectives: Mass Suicide And The Jonestown Massacre

Related Papers

Alternative Spirituality and Religion Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 155-158

Carole Cusack

Sarah Snyder

The Demise of Religion: How Religions End, Die or Dissipate, London, Bloomsbury, 2020, pp.179-190.

With regard to processes of change which are indicative of decline, loss of membership or social and political influence, weakening or fragmentation, and final demise or extinction, in the study of new religious movements (NRMs) no agreed vocabulary has emerged to map the particular trajectories of specific groups, or to craft a model that has application across either the ‘class’ of NRMs as a whole, or of certain sub-classes (UFO religions, ephemeral ‘spiritual’ clusters, or neo-Hindu guru focused groups, for example). The language used to describe such negative developments among all religions may be strong and definite (for example, death, end, eradication) or more modest, as in the use of ‘demise’ as a broad catch-all that can encompass everything from decisive, datable ends to attenuated trends and indicators that bode ill, but where no endgame has been reached (de Jong 2018). The difficulty in identifying unambiguous ends was noted by Bryan R. Wilson more than three decades ago; he linked the failure of new religions to endogenous issues (while acknowledging exogenous pressures might also contribute), and proposed ideology, leadership, organization, constituency, and institutionalization to be the crucial factors (Wilson 1987). The recognition that new religions do not come into existence ex nihilo, but rather were embedded in the culture(s) of the charismatic founder and the early convert community, and that NRMs drew upon existing religious and spiritual concepts and trends, renders beginnings and endings fluid and mixed, with ambiguity about all but the simplest types of origins and endings being the norm not the exception. The clearest case for ‘endings’ in new religions appeared to be in acts of violence, including mass suicide and mass murder (Richardson 2001), upheavals sufficient to make it impossible for the group to continue.

Durkheim 'Le suicide'. One hundred years later

Ferenc Moksony

Sundus Abdirashid

Sociology Mind

Steven Gerardi

John Rankin

irfan juliana

John R. Hall

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The Truth About Jonestown

Offers a look at the jonestown holocaust and explains why 13 years later, we should still be afraid. background; the peoples temple; the cult's founder and religious leader, reverend jim jones; the fundamental weakness of the human mind; the mass suicide of 912 people; comments from survivors; what jones talked the people into doing; discussion of many abuses; peoples' belief that he was god; how jones died..

By K. Harary published March 1, 1992 - last reviewed on June 9, 2016

THE OLD PEOPLES TEMPLE BUILDING COLLAPSED in the last big San Francisco earthquake, leaving behind nothing but an empty plot of land to mark its passing. I'd avoided the place for nearly 10 years -- it always struck me as a dark reminder of the raw vulnerability of the human mind and the superficial nature of civilized behavior. In ways that I never expected when I first decided to investigate the Jonestown holocaust, the crimes that took place within that building and within the cult itself have become a part of my personal memory . If Jim Jones has finally become a metaphor, a symbol of power-hungry insanity—if not a term for insanity itself—for me he will always remain much too human.

SUICIDE IS USUALLY an act of lonely desperation, carried out in isolation or near isolation by those who see death as an acceptable alternative to the burdens of continued existence. It can also be an act of self-preservation among those who prefer a dignified death to the ravages of illness or some perceived humiliation . It is even, occasionally, a political statement. But it is rarely, if ever, a social event. The reported collective self-extermination of 912 individuals (913 when Jim Jones was counted among their number) therefore demanded more than an ordinary explanation.

The only information I had about Jim Jones was what I could gather from news accounts of the closing scene at the Jonestown compound. The details were sketchy but deeply disturbing: The decomposing corpses were discovered in the jungle in the stinking aftermath of a suicidal frenzy set around a vat of cyanide-laced Flavor-Aid. Littered among the dead like broken dolls were the bodies of 276 children. A United States congressman and three members of the press entourage traveling with him were ambushed and murdered on an airstrip not far from the scene. It had all been done in the name of a formerly lesser-known cult called the Peoples Temple.

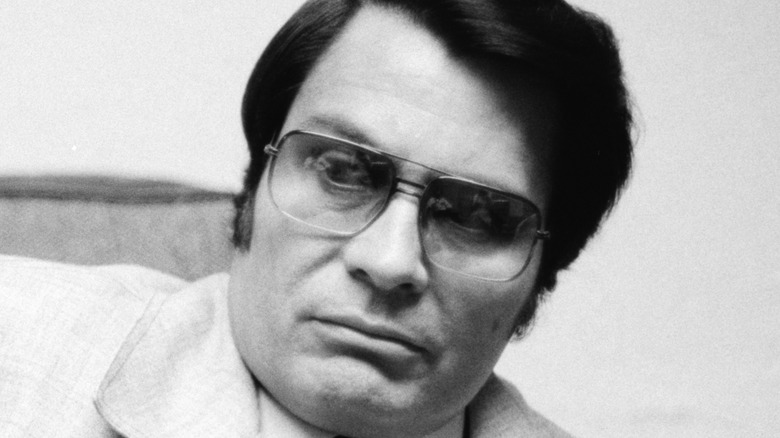

The group was started years before with the avowed vision of abolishing racism . Although it was headquartered in San Francisco, its members sought to found their own Utopia in a nondescript plot of South American jungle near Georgetown, Guyana. The commune they created was named in honor of the cult's founder and religious leader , a charismatic figure in dark glasses named the Reverend Jim Jones.

While the news media treated the Jonestown holocaust like a fluke of nature, it seemed to me a unique opportunity to learn something crucial about the fundamental weakness of the human mind. In addition to my formal education in psychology, I had recently spent four years as a suicide-prevention counselor and had helped train dozens of other counselors working in the field. But even with that experience, the slaughter that took place in Jonestown seemed incomprehensible.

No casual observer could adequately explain what was happening in the minds of the Peoples Temple members when they allowed Jones to assume ultimate power over their lives. The question of how one person—nonetheless an entire group—could be motivated to give away such power was, however, the most critical one to ask. Not only was it essential to answer that question in order to explain what became of the Peoples Temple; it was equally crucial to answer it in order to prevent a similar tragedy from happening again in the future. Had the massacre succeeded in killing all the witnesses to what occurred inside the confines of Jonestown, it would have been impossible to get a believable answer. But there were a number of survivors: An old woman sleeping in a hut slipped the minds of her fellow members who were preoccupied with dying at the time; a nine-year-old girl survived having her throat cut by a member who then committed suicide; a young man worked his way to the edge of the compound and fled into the jungle. The only other eyewitness escaped when he was sent to get a stethoscope so the bodies could be checked to make certain they were dead.

Other survivors included a man wounded by gunfire at the airstrip who managed to escape by scrambling into the bush; the official Peoples Temple basketball team (including Jones's son), which was visiting Georgetown during the holocaust; a number of members stationed at the San Francisco headquarters; and a small group of defectors and relatives of those who had remained in the cult. The last was gathered at a place called the Human Freedom Center in Berkeley—a halfway house for cult defectors founded by Jeannie and Al Mills, two Peoples Temple expatriates.

Since most of the survivors lived in and around San Francisco, it was clear that in order to get to know any of them, I would have to be willing to go where the moment took me. I resigned from my position in the psychiatry department of a New York medical center, shipped most of what I owned to a storage facility, and moved to California. Shortly after arriving, I learned that the center was looking for a director of counseling. It was exactly the position I wanted.

It is impossible to look back on my first encounter with Jeannie and Al without coloring the memory with the knowledge that both of them were murdered almost exactly one year later. We met in the same room where they had once helped Congressman Leo Ryan plan his ill-fated expedition to Jonestown, which was mounted to give him and the press a close-up look at the cult and to offer any constituents who wanted safe passage an opportunity to return to San Francisco. They had hoped the visit would precipitate the demise of the Peoples Temple, but instead of allowing his game to be raided, Jones had Ryan killed and passed out the poison. The Millses never imagined the scenic route to hell they were paving with their good intentions: Had they not convinced the congressman to go to Guyana, the massacre would most likely never have happened.

In the years that have passed since the Millses' assassination, I have never again been able to take a death threat lightly.

The pair had been members of the Planning Commission—the elite inner circle of the Peoples Temple. They had been with Jim Jones since the early days of the cult and had raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for his cause. But Jeannie wanted a bigger role in running the group than Jones was prepared to give her. His refusal to allow her to manage the affairs of the temple created a bitter falling-out between them. She and Al quit after spending six years in the cult, fearing for their lives because Jones always threatened that anyone who left would be murdered by his "angels"—a euphemism for his personal squad of thugs.

Jones had forced them to prove their loyalty by signing blank pieces of paper, blank power-of-attorney forms, and false confessions that they had molested their children, conspired to overthrow the U. S. government, and committed other crimes while members of the cult. (It was the sort of thing Jones did to control people, like the time he tricked a member into putting her fingerprints on a gun and told her he would have someone killed with it and frame her for the murder if she ever left the group.)

There was a deliberate malevolence about the way Jones treated the members of his cult that went beyond mere perversion. It was all about forcing members to experience themselves as vulgar and despicable people who could never return to a normal life outside of the group. It was about destroying any personal relationships that might come ahead of the relationship each individual member had with him. It was about terrorizing children and turning them against their parents. It was about seeing Jim Jones as an omnipotent figure who could snuff out members' lives on a whim as easily as he had already snuffed out their self-respect. In short, it was about mind control. And, after all that, it was not incidentally about Jones's own sick fantasies and sexual perversions.

Both men and women were routinely beaten, coerced into having sex with Jones in private and with other people in public. Husbands and wives were forbidden to have sex with each other, but were forced to join other members in watching their spouses being sexually humiliated and abused. In order to prove that he wasn't a racist, a white man was coerced into having oral sex in front of a gathering of members with a black woman who was having her period. Another man was made to remove all his clothes, bend over and spread his legs before the congregation while being examined for signs of venereal disease. A woman had to strip in front of the group so that Jones could poke fun at her overweight body before telling her to submerge herself in a pool of ice-cold water. Another woman was made to squat in front of 100 members and defecate into a fruit can. Children were tortured with electric shocks, viciously beaten, punished by being kept in the bottom of a jungle well, forced to have hot peppers stuffed up their rectums, and made to eat their own vomit.

Dozens of suicide drills—or "white nights" as Jim Jones called them—were rehearsed in San Francisco and in the jungle in a prelude to the final curtain he said might fall at any moment. Members were given wine to drink, then told it had been poisoned to test their loyalty and get them used to the idea that they might all be asked to take their lives as a sign of their faith. Their deaths, Jones tried to convince them, would be honored by the world as a symbolic protest against the evils of mankind -- a collective self-immolation. (This would also serve to eliminate anyone who might reveal the dirty secrets of life with the Peoples Temple.) The faithful would be "transformed," Jones claimed, and live with him forever on another planet.

The abuses had been going on for years, which made it seem all the more unbelievable. Those who underestimated the fragility of the human mind could not comprehend how anyone in California could remain a member, let alone follow Jim Jones into the jungle. Yet those who believed in him could not consider any alternatives that were not among the choices he provided. Even those who might have been capable of imagining themselves getting free of the cult knew about the stated Policy of murdering defectors. And since any loved ones who were left behind would suffer retribution, few dared escape while family members remained in Jonestown. The practical effect of that double bind was a twilight-zone reality in which people pretended to be enjoying a Utopian existence while living in constant fear for their lives.

THE HUMAN freedom Center was a beaten-up, two-story wood-and-stucco building that had once been used as a private rest home. Its long rows of odd-size rooms filled with broken-down furniture could have served as a backdrop for a 1950s horror movie set in a sanitarium. Although most of the Peoples Temple survivors who might have taken refuge there were suddenly dead, the events in Jonestown instantly made many other organizations seem potentially as dangerous. Jeannie and Al decided to open the center to defectors from all sorts of cult groups, from the Unification Church to the Hare Krishnas. I had already decided that— whatever the pay—if they offered me the director of counseling position, I was going to take it.

Al Mills gripped my hand like an old war buddy the first time we met. His square chin and warm smile all but obliterated the other features on his face. He had marched with Martin Luther King and once believed that the Peoples Temple would fulfill his dream of integration and racial equality. (That belief was trampled when he realized that Jones rarely allowed blacks to assume positions of authority within the temple.)

My first discussion with Jeannie was less like a job interview than a confrontation. She looked straight at me and said that a Peoples Temple hit squad might burst in and kill us at any moment. Jim Jones, she said, had sworn in the midst of the holocaust that she and Al and everyone associated with them would eventually pay with their lives for betraying the cult and sending Ryan to Guyana. The possibility lent a certain sense of immediacy to our interaction.

My exact response seemed less important than the fact that I didn't make an excuse to leave the building immediately and that I had already demonstrated my commitment to understanding the cult mentality by dropping everything and moving to California. By the end of the meeting, Jeannie offered me a token salary for a job that would often require more than 12 hours a day and frequently seven days a week.

Most of the center's clients were people seeking help in extricating family members from various cults, or ex-cult members who were starting to put their own lives back together. Additionally, a couple of former Peoples Temple members lived on the premises, and others came in periodically to talk about their present feelings and past experiences.

The first thing that struck me when I met the clients and got to know them was that, although the specific details of their belief systems and activities varied considerably, those who became involved in cults had a frightening underlying commonality. They described their experiences as finding an unexpected sense of purpose, as though they were becoming a part of something extraordinarily significant that seemed to carry them beyond their feelings of isolation and toward an expanded sense of reality and the meaning of life. Nobody asked if they would be willing to commit suicide the first time they attended a meeting. Nor did anyone mention that the feeling of expansiveness they were enjoying would later be used to turn them against each other.

Instead they were told about the remarkable Reverend Jones, a self-professed social visionary and prophet who apparently could heal the sick and predict the future. Jim Jones did everything within his power to perpetuate that myth: fraudulent psychic-healing demonstrations using rotting animal organs as phony tumors; searching through members' garbage for information to reveal in fake psychic readings; drugging his followers to make it appear as though he were actually raising the dead. Even Jeannie Mills, who later told me she knowingly assisted Jones in his faked demonstrations said she did so because she believed she was helping him conserve his real supernatural powers for more important matters.

Critical levels of sleep deprivation can masquerade as noble dedication. A total lack of adequate nutrition can seem acceptable when presented as a reasonable sacrifice for a worthy cause. Combining the two for a prolonged length of time will inevitably break down the ability to make rational judgments and weaken the psychological resistance of anyone. So can the not-infrequent practice of putting drugs in the members' food. The old self, the one that previously felt lonely and lacking in a sense of purpose, is gradually overcome by a new sense of self inextricably linked with the feeling of expansiveness associated with originally joining the cult and becoming intrigued with its leader.

Belonging to the group gradually becomes more important than anything else. When applied in various combinations, fear of being rejected, of doing or saying something wrong that will blow the whole illusion wide open; being punished and degraded, subjected to physical threats, unprovoked violence, and sexual abuse ; fear of never amounting to anything; and the fear of returning to an old self associated almost exclusively with feelings of loneliness and a lack of meaning will confuse almost anyone. Patricia Hearst knows all about it. So did all the members of the Peoples Temple.

Once thrown off balance (in the exclusive company of other people who already believe it) and being shown evidence that supports the conclusion, it is not difficult to become convinced that you have actually met the Living God. In the glazed and pallid stupor associated with achieving that confused and dangerous state of mind, almost any conceivable act of self-sacrifice, self-degradation, and cruelty can become possible.

The truth of that realization was brought home to me by one survivor who, finding himself surrounded by rifles, was told he could take the poison quietly or they would stick it in his veins or blow his brains out. He didn't resist. Instead, he raised his cup and toasted those dying around him without drinking. "We'll see each other in the transformation," he said. Then he walked around the compound shaking hands until he'd worked his way to the edge of the jungle, where he ran and hid until he felt certain it had to be over.

"Why did you follow Jim Jones?" I asked him.

"Because I believed he was God," he answered. "We all believed he was God."

A number of Peoples Temple survivors told me they viewed Jones in the same way—not as God metaphorically, but as God literally. They would have done anything he asked of them, they said. Or almost anything.

The fact that some members held guns on the others and handled the syringes meant that what occurred in Jonestown was not only a mass suicide but also a mass murder . According to the witnesses, more than one member was physically restrained while being poisoned. A little girl kept spitting out the poison until they held her mouth closed and forced her to swallow it -- 276 children do not calmly kill themselves just because someone who claims to be God tells them to. A woman was found with nearly every joint in her body yanked apart from trying to pull away from the people who were holding her down and poisoning her. All 912 Peoples Temple members did not die easily.

Yet even if all the victims did not take their own lives willingly, enough of them probably did so that we cannot deny the force of their Conviction. Only a small contingent of Peoples Temple members asked to return with Leo Ryan to San Francisco. The rest chose to stay behind. Jim Jones may have had less to fear from Jeannie and Al Mills than he believed.

It should also be remembered that Jones never took the poison he gave to his followers but was shot by someone else during the final death scene in Jonestown. He created a false reality around himself in which the denial of his own mortality must have made his own demise seem inconceivable. The fact that he had millions of dollars in foreign bank accounts and had often alluded to starting over elsewhere led Jeannie to speculate that he planned to escape the holocaust but was murdered by one of his guards or mistresses.

It is difficult to imagine what incomprehensible sense of insecurity must have led Jim Jones to feel that he had to convince himself and other people that he was God incarnate. It was not a delusion that he ever suffered well. Some of those who knew him personally described him to me at various times as a mere voyeur, a master con artist, a sociopath , and a demon. Al Mills once said that any private interaction between Jones and another person always felt like a "conspiracy of two." For my own part, I resist any description of the man that might make any of us feel too secure in the notion that he was one of a kind and the likes of him will never come again.

After Jeannie and Al were murdered, I went back alone for a final look inside the Peoples Temple building where Jeannie once gave me a private tour. All that remained of that particular nightmare setting was a dusty maze of dimly lit corridors, hollow rooms, and twisting stairways. The daylight seemed reluctant to come in through the windows, as though it entered more out of a sense of obligation than any real desire to be there. It was impossible to walk through the place without feeling as though somebody were coming up behind me—nearly everything about it seemed haunted.

"This may not be the best idea in the world," I remembered Jeannie saying when she took me there. "There may be some people hanging around here who want to kill me." It may have been guilt that led her to say that, or paranoia , or the realistic conclusion that the relatives and friends of many of the victims must have held her at least partly responsible for what happened. The Jonestown holocaust might have been inevitable or it might have been avoided; but by turning up the pressure on Jones in the way that they did, Jeannie and Al inextricably became accessories to the disaster.

Under the circumstances, I suggested that getting the hell out of there might be the best approach. "Life is short, Keith," Jeannie told me. She showed me where Jones's personal armed guards had once been posted, before taking me to lunch at a hamburger stand where she used to hang out in the heyday of the temple.

In many ways, Jeannie was a social relic of the best and worst aspects of a way of life that died in the jungle with Jim Jones. She said and did things designed for their disarming effect, to crawl around under your skin and keep you off guard. She was an expert at making you feel that you were a part of something important, dangerous, and utterly surrealistic—and she may have been right. It did not surprise me to learn that she was monitoring my personal telephone conversations at the Human Freedom Center from a line she had installed at her home up the street. It was exactly the way things were done in the Peoples Temple.