MythologySource

- What Were the Hamadryads in Greek Mythology?

- The Hades and Persephone Story

- Was the Griffin a Bird from Greek Mythology?

Zeus and Hera

The king and queen of the gods were supposed to be the model of a perfect marriage, but the stories of Zeus and Hera show that their relationship was anything but divine!

According to most sources, Zeus did not originally intend to marry his sister, Hera.

He first married the Titaness Metis, but turned her into a fly and swallowed her when he learned that her son would eventually overthrow him. He then courted Thetis, but abandoned the idea of marrying that Titaness when a similar prediction was made.

For her part, Hera was not initially open to the marriage either. Zeus turned himself into a wounded bird to get close to Hera and only after earning her trust in that way was he able to make her his wife.

Some writers claimed that the couple enjoyed a few centuries of harmony and happiness together. This was not to last, however, as the pairing of a womanizing god and a jealous goddess inevitably led to conflict and unhappiness.

You might expect the king of the gods and his queen to be the epitome of a happy, or at least amicable, couple. The marriage of Zeus and Hera, however, was known more for their arguments than their joy.

The Marriage of Zeus and Hera

While some claimed that the couple were initially happy, other sources implied that Hera was prone to jealousy early in their relationship.

When Zeus had swallowed Metis, he hadn’t known that she was already pregnant with his daughter. Athena was born out of her father’s head and was generally described as not having a mother in any real sense.

According to some legends, Hera was jealous that her husband had produced such a powerful goddess without her. In return she created Hephaestus without him, but was foiled when the child was born lame and deformed.

The trend of Hera being jealous and spiteful toward her husband’s children continued throughout their reign.

Zeus was known for taking many mistresses. He fathered some gods, but more of his children were mortals who grew into great heroes, kings, and queens.

Hera was almost always depicted as being jealous of these children, to the point that she was driven to vindictiveness. Her feelings were probably exacerbated by the fact that Zeus seemed to prefer these human children over her own son, Ares.

Hera often took her anger out on the women Zeus had slept with. For example, she turned the Libyan queen Lamia into a monster when she learned that Zeus had fathered children with her.

Sometimes, her anger could be deadly. Semele, the human mother of Dionysus , was tricked by Hera into seeing Zeus in his full glory. No human could survive such an event, and Semele was burned alive.

Women who were pursued by Zeus learned to avoid Hera as well. Io, who had been turned into a cow by Zeus to hide her from his wife, spent years wandering the earth to avoid both Zeus’s advances and Hera’s punishment.

This attitude was not reserved just for mortal women. Her fellow goddesses could feel her wrath, as well.

When Leto went into labor with Apollo and Artemis, Hera prevented the goddess of childbirth from attending to her. Without Eileithya’s help, Leto’s labor was slow and painful.

Her most famous anger was directed not at one of Zeus’s mistresses, but at his son. In the legends of Heracles, his stepmother is featured as his constant antagonist.

Hera tried to kill him as an infant, but when Heracles survived and grew into a strong young man she redoubled her efforts. She drove him made so that he killed his own family, then orchestrated the twelve labors that would earn him absolution.

Even during his decade of servitude, Hera interfered to make the labors of Heracles more difficult and dangerous. For example when Hippolyta, the queen of the Amazons, was ready to help the hero Hera spread a rumor that caused the warrior women to attack him instead.

The disputes between Hera and Zeus were not limited to his extramarital affairs. In the Iliad , Hera conspired to make Zeus sleep so the gods could be free of his command to stay out of the battles of men.

In another instance, she even plotted with Poseidon to remove her husband from power. They were unsuccessful, and it was many years before Zeus forgave them for the attempt.

Despite their many problems, the two were never enemies. When Ixion planned to assault the goddess, her husband not only prevented the attack but gave Ixion a harsh punishment in Hades for the crime of attempting to violate his wife.

My Modern Interpretation

Despite their contentious marriage and her flights of jealousy, Hera was known as the goddess of marriage.

Her fury toward her husband’s indiscretions can be attributed to this domain. She ruled over the proper arrangements of marriage, and her husband’s many affairs were a direct affront not only to their marriage, but also to her role as a goddess.

Greek culture commonly accepted, however, that men often cheated on their wives. Women were bound by the laws of monogamy, but their husbands often took mistresses.

In this view of marriage, Hera really did embody the role of a Greek wife. While Zeus had dozens, if not hundreds, of children, Hera was always faithful.

Unlike Aphrodite , for example, she had no affairs during her marriage and had taken no lovers before it. Aside from the avowed virgins, she was one of the only goddesses to never have a child outside of her marriage.

In this way, the relationship between Zeus and Hera did represent an ideal, albeit one that seems horrible to modern readers.

For his part, Zeus was unfaithful but was rarely seen treating Hera with particularly cruelty. He was as well-known for his short temper as she was, but he rarely displayed this trait with his wife.

In only one story did Zeus punish Hera for her actions – when she plotted to overthrow him. This rarely-repeated story appears to be a later myth, however, and most stories show him as a protective and peaceable, albeit unfaithful, husband.

Zeus and Hera as king and queen of Olympus were not expected to have a loving relationship. Theirs was, like most rulers, a marriage of political necessity.

Thus, they represented the ideal for the nobles of Greece, who lived much different lives than the common people. While the lower classes could marry for love, the wealthy formed unions to strengthen their power and looked to Hera and Zeus as an example of a couple that married for political reasons but enjoyed a certain measure of comfort in their relationship.

Still, the Greeks seemed to realize that their goddess of marriage did not have a perfect union. It would, ironically, be her most hated stepchild who finally fit the ideal.

While Hera was famously jealous, her divine stepchildren rarely attracted particular ire. Regardless of their origins, once they were welcomed into Olympus Dionysus, Hermes, Apollo, and Artemis were her peers and above her petty attacks.

In his mortal life, Hera’s attacks on Heracles had been relentless. When his mortal life ended and he became a god, however, she ended her campaign against him.

Heracles married Hebe, the daughter of Zeus and Hera and the goddess of youth. He became Hera’s son-in-law and an official member of his father’s household.

Heracles had followed his father’s tendencies in life and had many affairs, but he was said to have settled down in a happy marriage with Hebe. Zeus and Hera’s children were able to exemplify the happy, stable relationship their father and mother had never been able to represent.

Zeus and Hera were not each other’s first choice in partners. Zeus married one Titaness and courted another before marrying Hera to ensure that their son would not be powerful enough to overthrow him.

Hera resisted the marriage at first, but eventually gave into her brother’s proposal. While they were said to have enjoyed a brief period of peace and happiness, this quickly gave way to conflict.

Zeus was notoriously unfaithful to his wife, while Hera was known for her extreme jealousy. Many of his mistresses and their children fell afoul of Hera’s terrible temper .

Most famously, she served as the antagonist in the legends of her stepson Heracles. She attempted many times to cause his death or just make his life difficult, even driving him insane and forcing him to kill his own family.

Hera occasionally worked against her husband, as well. In one story, which appears to have not been widespread, she even plotted to overthrow her husband.

The marriage of Zeus and Hera was tumultuous even though they were supposed to represent the ideal king and queen. As the goddess of marriage, Hera’s own relationship seemed unhappy and contentious.

There was a degree of idealism in how the couple was shown, however. Hera was appropriately faithful, and Zeus was both protective of his wife and remarkably even-tempered with her.

In this way Zeus and Hera represented not an average marriage, but the type of politically-motivated relationships entered into by human kings and queens. Without deep love or an expectation of fidelity on the husband’s part, the rulers who looked up to them hoped to emulate their relatively peaceful cohabitation.

Eventually, a more perfect Olympian marriage would be exemplified by Heracles and Hera’s own daughter, Hebe. Late in their history, the Greeks adapted their mythology to include a more loving and faithful couple in the household of their king.

My name is Mike and for as long as I can remember (too long!) I have been in love with all things related to Mythology. I am the owner and chief researcher at this site. My work has also been published on Buzzfeed and most recently in Time magazine. Please like and share this article if you found it useful.

More in Greek

Thero: the beastly nymph.

The people of Sparta claimed that Ares had been nursed by a nymph called Thero. Does...

Who Was Nomia in Greek Mythology?

Some nymphs in Greek mythology were famous, but others were only known in a certain time...

Connect With Us

GetGoodEssay

essay about the drama zeus and hera

Zeus and Hera is one of the most popular Greek dramas. It tells the story of the king of the gods, Zeus, and his wife, Hera. The play is full of action and suspense, and it is sure to keep you entertained from start to finish.

What is the drama Zeus and Hera about?

Zeus and Hera is a Greek tragedy written by Aeschylus. It was first performed in 458 BC, at the City Dionysia festival. The play is based on the myth of the affair between Zeus and Hera, and her subsequent revenge on Zeus.

The play begins with Zeus and Hera arguing over who is more powerful. Zeus insists that he is more powerful, because he is the king of the gods. Hera argues that she is more powerful, because she is the queen of heaven. They agree to settle their disagreement by each telling a story about their most recent exploits.

Zeus tells the story of how he disguised himself as an old man , in order to seduce a young woman named Io. Hera tells the story of how she punished a mortal woman named Semele, for daring to compare herself to a god.

After hearing each other’s stories, Zeus and Hera come to an understanding of each other’s power. They declare their love for each other, and agree to never fight again.

What are the different elements of the drama?

The different elements of drama are typically thought to include plot, character, setting, theme, and symbolism. In a traditional five-act structure, the first act is considered exposition, which introduces the characters, their motivations, and the overall conflict. The second act typically features rising action as the conflict begins to intensify. The third act is often the climax of the story, in which the tension reaches its peak and is resolved. The fourth act is generally considered falling action, in which the aftermath of the climax is explored and loose ends are wrapped up. Finally, the fifth act is known as denouement or resolution, in which all remaining conflicts are resolved and the story comes to a close.

What are the pros and cons of the drama?

There are many pros and cons to the drama Zeus and Hera. On the one hand, it is a classic story that has been retold many times. It is also a very popular play, so there are likely to be many people who have already seen it. On the other hand, it can be very violent and may not be suitable for younger audiences. Additionally, the plot can be difficult to follow if you are not familiar with Greek mythology.

What is the moral of the story?

There are many different interpretations of the moral of the story of Zeus and Hera. One popular interpretation is that it is important to be true to yourself and stay true to your beliefs, even when others may not agree with you. Another interpretation is that it is important to be mindful of the power dynamics in any relationship, and to make sure that you are not being taken advantage of. Ultimately, it is up to the reader to decide what they believe the moral of the story is.

How can the drama be improved?

The drama Zeus and Hera can be improved in a number of ways. One way would be to make the characters more three-dimensional and believable. Another way would be to make the plot more interesting and suspenseful. Finally, the dialogue could be made more natural and realistic.

The drama Zeus and Hera is a story that highlights the importance of communication and understanding in a relationship. Although the couple faces challenges, they are ultimately able to overcome them by working together. This essay has shown how the drama can be used to teach valuable lessons about relationships .

- How To Write A Contention In An Essay | Guide

- Recent Posts

- Essay On The Glass Menagerie: Unraveling Symbolism - September 21, 2023

- Essay On The Role of UDF Against Apartheid - September 13, 2023

- Essay On Hendrik Verwoerd’s Speech and the Apartheid Regime - September 12, 2023

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Zeus and Hera: infidelity and revenge

Hera, the mean girl of Mt. Olympus. Zeus, the wayward philanderer. So hey, how did they meet? How was their relationship? And what does that say about greek mythology? Author and Greek mythology expert Liv Albert answers all.

As the king and queen of the Olympian gods, you might expect Zeus and Hera to have a nice, healthy, loving relationship…But then, that wouldn’t be particularly fitting with the wider world of Greek mythology. Like most of the gods of Olympus, their relationship and characters are flawed and dangerous and, most importantly, interesting.

Zeus and Hera are two of the six first generation Olympian gods, both children of the famed Titans Cronos and Rhea (yes, this does mean they’re siblings but it’s best not to dwell on that). Their lives began tumultuously: Cronos famously developed a habit of devouring his children in an effort to avoid any one of them becoming more powerful than him. It was only when the last child was born, Zeus, that machinations were put into place to allow Zeus to overthrow Cronos, free his siblings, and take his place on the throne of Mount Olympus. After a couple of short-lived (but procreative!) relationships with the Titan goddesses Metis and Mnemosyne, Zeus finally settled down with the goddess, Hera. Settled is perhaps the wrong word, the couple were rarely content together and their marriage vows would not stop Zeus from spawning more gods and mortals.

Zeus spends the majority of his mythological stories finding mortal women with whom to procreate, spawning hero after hero. Many of the most famous heroes and characters of myth were the children of Zeus, but unlike movies like Disney’s Hercules might have you believe, their mother was almost never Hera. The heroes Heracles (better known as Hercules, his Roman name), Perseus, Minos, Sarpedon, and the twins Castor and Polydeuces among others, and gods like Apollo and Artemis, Athena, Hermes, Dionysus, and the Muses, were all children of Zeus with women and goddesses that were not Hera.

However, for all Zeus spawned many (hundreds wouldn’t be a stretch!) famous mythological figures with other women, goddesses, and nymphs, Hera and her husband did have a few famous children of their own. The god of war, Ares, the goddess of childbirth, Eileithyia, and the goddess of youth, Hebe, were all the product of the king and queen of the gods’ marriage. In some sources the god Hephaestus was another of their children, though other sources quite convincingly attribute his parentage to Hera alone.

Together the pair ruled over Mount Olympus and the rest of the deities and humans of Greek mythology. Zeus was the king of the gods, the god of the weather, the sky, fate, and the rule of law. He loved to wield a lightning bolt and send thunderous echoes throughout the mortal world. Hera, meanwhile, was queen of the gods and goddess of marriage and women.

It is not lost of feminists of the modern world that the goddess of women was so often spending her time punishing mortal women for the actions of her husband. To say the ancient Greek sources were a product of their time is the understatement of a lifetime! Some of the couples’ most famous stories revolve around such punishments. When Zeus impregnated the mortal princess Semele with the god Dionysus, Hera caused her tragic death before her son was even born (Zeus sewed the premature baby into his thigh to continue to gestate!). When Zeus 'fell in love' with a woman named Io and transformed her into a cow to avoid Hera’s wrath, Hera found out the truth anyway and caused her to wander the earth pursued by a very annoying gadfly! But Hera didn’t always direct her wrath at the women: the most famous subject of her ire was the hero Heracles who was born to Zeus and a mortal woman named Alcmene. Hera devoted Heracles’ entire lifetime to attempting to kill him with varying degrees of creativity. Eventually, though, she had to give up when he was deified in death and brought to live on Mount Olympus and marry Hera’s own daughter, the goddess Hebe. Hera’s attempts to punish these mortals and heroes might be the most famous of her stories, but there was one instance where she went even further in her fury. She attempted a coup on Olympus! Hera, frustrated for all her husband’s infidelities and general tyranny, colluded with a number of other Olympians who felt similarly and attempted to overthrow her husband. She was thwarted by the nymph-goddess Thetis who saved Zeus with the help of one of the monstrous Hecatonchires (the “Hundred-Handers”!), Briareus.

The stories of Hera and Zeus were nothing if not dramatic. Passed on through oral storytelling practices (and later, Greek tragedy) these mythologies provided a certain type of entertainment and in some instances, status. The children that resulted from Zeus’ many relationships spanned the Greek world, not only connecting individual regions to the deities they worshipped but also to each other. While today Zeus’ actions are understood to be abhorrent, his legendary status in Ancient Greece meant that if your local region was connected to him through his lineage then he put you on the map. While his infidelity and Hera’s revenge may not seem particularly godlike by modern standards, the myths and stories of Ancient Greece weren’t used as moral guides like we might expect. The gods were complex and flawed and very human in their nature. Mortals, rather than looking to the gods as an example, feared their wrath and worked to keep them happy to avoid their scorn, no matter how unfairly this landed across the genders. If we can learn anything about Hera and Zeus, it’s that you wouldn’t want to cross them and the Greeks knew just that!

- Old World Gods

Zeus And Hera Marriage: A Powerful Union of Gods

Zeus and Hera marriage is a prominent and powerful union in Greek mythology . Their relationship, rooted in power and politics rather than love, is characterized by infidelity, jealousy, and vengeance.

Despite these challenges, their marriage produced notable divine offspring. Zeus , as the king of the gods, chose Hera as his wife, despite her being his sister. Together, they represent the ultimate authority among the gods and their marriage holds a significant impact in Greek mythology .

Today, we explore the captivating story of Zeus and Hera ’s union. Stay tuned for an in-depth analysis of their mythological journey.

Content of this Article

The Story of Zeus and Hera

The mythological couple of Zeus and Hera holds a significant place in Greek mythology .

Their story, filled with intrigue and drama, unveils a complex relationship embedded in power dynamics and divine politics.

Zeus and Hera : A Mythological Couple

Zeus , the mighty king of the gods, and Hera , his sister, were brought together in a union that transcended the boundaries of mere mortal love. Their marriage was not forged out of affection, but rather as a means to establish power and political alliances among the gods.

The Marriage of Zeus and Hera

The matrimonial bond between Zeus and Hera originated from Zeus ’ decision to choose Hera as his wife, despite her being his sister. The wedding ceremony, held in the mythical Garden of the Hesperides , witnessed a glorious night that spanned an incredible 300 years.

The Nature of Their Relationship

However, the union between Zeus and Hera was far from harmonious. Zeus , known for his numerous affairs with both mortal women and goddesses, constantly tested Hera ’s patience, evoking her wrath and fueling her jealousy.

Despite the challenges they faced, their marriage endured, each holding their own position of power and authority within the divine hierarchy.

Hera : The Queen of the Gods

Hera , known as the Queen of the Gods in Greek mythology , plays a significant role in the pantheon. She is the wife and sister of Zeus , the king of the gods.

Download for FREE here our best selection of Images of the Mythology Gods and Goddesses!

As the goddess of marriage and childbirth, Hera is associated with women’s roles and the sacred institution of marriage.

Hera ’s Role in Greek Mythology

Hera ’s role in Greek mythology extends beyond her position as Zeus ’ wife. She represents the idealized image of a married woman, the epitome of loyalty and devotion. As the protector of married women, Hera presides over the marriages of mortal couples and blesses them with fertility and domestic harmony.

She embodies the sanctity and societal importance placed on marital unions in ancient Greece.

Hera ’s Jealousy and Vengeance

Hera ’s most well-known characteristic is her jealousy, particularly towards Zeus ’ numerous affairs and illegitimate children. Her anger and vengeful nature are directed not only towards Zeus ’ lovers but also towards their offspring.

She takes pleasure in tormenting and punishing these individuals, ensuring that they suffer the consequences of their actions.

Hera ’s Children and Family

Hera and Zeus ’ union resulted in the birth of several prominent deities. Together, they are the parents of Hephaestus , the god of fire and craftsmanship, and Ares , the god of war.

They also have children like Eileithyia , the goddess of childbirth, and Hebe , the goddess of youth. Despite her own maternal instincts, Hera ’s vengeful nature often affects her relationship with her children.

Hera ’s familial connections extend beyond her immediate offspring. She is the sister of Zeus , as well as the daughter of Cronus and Rhea . Hera ’s lineage and position as the queen of the gods solidify her authority and power within the divine hierarchy.

Zeus : The King of the Gods

Zeus , the powerful ruler of Mount Olympus, holds the title of the king of the gods in Greek mythology . Let’s explore different aspects of Zeus ’ character and his role in the divine hierarchy.

Zeus ’ Infidelity and Affairs

Zeus is notorious for his numerous infidelities and affairs, which often involve mortal women. His charm and irresistible nature attracted many, leading to a string of relationships outside his marriage to Hera .

He pursued these affairs despite knowing the potential consequences and repercussions from his jealous wife, Hera . These affairs resulted in the birth of several demigods and other mythical beings throughout Greek mythology .

Zeus ’ Children and Lineage

Zeus ’ extensive lineage is filled with offspring from both his marriage to Hera and his affairs with various women. Many of these children played important roles in Greek mythology .

Among his famous offspring are Ares , the god of war, Athena , the goddess of wisdom, Apollo , the god of light and music, Artemis , the goddess of the hunt, Hermes , the messenger god, and Dionysus , the god of wine.

Zeus ’ children played significant roles in various myths and legends, often wielding immense power and abilities inherited from their divine father.

Zeus ’ Relationship with Hera

The relationship between Zeus and Hera was complex and tumultuous. Although Zeus chose Hera as his wife, their marriage was filled with tensions, primarily due to Zeus ’ constant infidelity.

Hera , being the queen of the gods, despised Zeus ’ affairs and sought revenge against his mortal lovers and their offspring. This continuous conflict between Zeus ’ indiscretions and Hera ’s vengeful nature created a strained dynamic within their relationship.

Despite the difficulties they faced, Zeus and Hera were bound by their roles as king and queen of the gods, representing the pinnacle of authority in Greek mythology .

Zeus ’ relationship with Hera played a significant role in shaping the dynamics of the divine hierarchy and influencing various myths and legends.

The Impact of Zeus and Hera ’s Marriage

The marriage of Zeus and Hera had a profound influence on Greek mythology , shaping various aspects of the divine world and human existence.

This section explores the significance of their union, the symbolism it embodied, and the lasting legacy it left behind.

The Influence of Zeus and Hera in Greek Mythology

Zeus and Hera ’s marriage played a pivotal role in Greek mythology , as they were considered the most authoritative and powerful couple among the gods. Their union represented the foundation of divine order and governance.

Zeus , as the king of the gods, embodied supreme authority, while Hera , as his queen, symbolized marital fidelity and the sanctity of marriage.

As the divine couple, Zeus and Hera oversaw various domains and aspects of life, including marriage, childbirth, and familial relations.

Their influence extended beyond the divine realm, permeating mortal society and shaping societal norms and values.

The Symbolism of their Union

The marriage of Zeus and Hera symbolized the interconnectedness of power, politics, and relationships. Their union demonstrated how marriages in ancient Greek society often served as power alliances between individuals and families.

It reflected the complex dynamics of marriage, where love and personal choice were often secondary to considerations of status, lineage, and strategic alliances.

Additionally, Hera ’s role as the goddess of marriage represented the importance of marital fidelity, while Zeus ’ infidelity highlighted the challenges and complexities of maintaining harmony within a marriage.

The symbolism of their union highlighted the tensions and contradictions inherent in the institution of marriage.

The Legacy of Zeus and Hera ’s Marriage

Zeus and Hera ’s marriage left a lasting impact on Greek mythology and cultural narratives. Their troubled relationship served as a cautionary tale, illustrating the consequences of infidelity, jealousy, and revenge within marriages.

Their mythical conflicts and divine interventions depicted the potential perils of straying from the boundaries of marital commitments.

Furthermore, Zeus and Hera ’s children and descendants played significant roles in Greek mythology , shaping epic narratives, heroic quests, and legendary lineages.

The prophecies, conflicts, and adventures associated with their offspring added depth and complexity to the wider mythological fabric.

The legacy of Zeus and Hera ’s marriage continues to resonate in modern interpretations of mythology and literature, highlighting enduring themes such as power dynamics, marital fidelity, and the complexities of human relationships.

The Role of Marriage and Motherhood in Greek Mythology

The realm of Greek mythology offers valuable insights into the role of marriage and motherhood. Within this ancient society, marriage was not always based on love, but rather served as a strategic power play.

It was a means for individuals, especially women, to gain status and forge alliances between families or even kingdoms.

Marriage as a Power Play in Greek Mythology

In Greek mythology , marriage was often a transaction arranged by families or political entities, with little consideration for the personal desires or emotions of the individuals involved. It served as a tool for consolidating power, advancing political agendas, and securing alliances.

For women, marriage was a critical aspect of their social and economic standing, determining their roles within society and their access to resources.

Within the context of Zeus and Hera ’s marriage, their union exemplifies the political nature of these pairings.

Zeus , as the king of the gods, selected Hera as his wife not out of affection, but to solidify his dominion and establish her as the queen. This type of arranged marriage mirrored the practices and motivations of mortal marriages within Greek society.

Motherhood and the Status of Women

Motherhood held immense significance in Greek mythology , as it was believed to carry divine lineage and shape the fates of both mortals and gods. Women’s status and worth were often tied to their ability to bear children, particularly male heirs.

Upon becoming mothers, women gained a elevated position within their families and communities, as their role was seen as essential for the continuation of lineage and the perpetuation of the gods’ favor.

In the case of Zeus and Hera , their children represented symbols of power and influence. Hera , as the mother of Ares , the god of war, and Hebe , the goddess of youth, possessed a unique role within the pantheon as the mother of notable deities.

This elevated her status and solidified her place as the queen of the gods.

Hera and the Goddesses of Marriage and Childbirth

- Hestia : The goddess of the hearth, family, and domestic life.

- Aphrodite : The goddess of love, beauty, and desire.

- Demeter : The goddess of grain, agriculture, and fertility.

These goddesses, along with Hera , were closely associated with marriage and childbirth, and they oversaw different aspects of domestic life.

They personified ideals and virtues related to women’s roles within the household and the importance of sustaining harmonious unions.

In conclusion, marriage and motherhood played significant roles in Greek mythology .

Marriage served as a means to consolidate power and forge alliances, while motherhood brought elevated status and divine importance to women. Hera , alongside other goddesses, represented the idealized versions of wives and mothers, emphasizing the societal expectations surrounding these roles.

Understanding the dynamics of marriage and motherhood in Greek mythology provides valuable insights into the social structures and beliefs of ancient Greek society.

The Presence of Zeus and Hera in Greek Epics and Literature

The mythical figures of Zeus and Hera have a significant presence in Greek epics and literature.

They are portrayed in various works of renowned authors, adding depth and complexity to their characters and their relationship. Let’s explore how Zeus and Hera are depicted in some of the most influential Greek epic poems, as well as in the works of famous poets and playwrights.

Zeus and Hera in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey

In Homer’s epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, Zeus and Hera both play significant roles. Zeus , as the supreme ruler of the gods, frequently intervenes in the affairs of mortals during the Trojan War described in the Iliad.

He sometimes supports the Greeks and sometimes favors the Trojans, causing tension and conflict among the gods on Mount Olympus. Hera , as his wife, often aids the Greeks and uses her influence to support their cause.

Her actions are driven by her desire to protect her favorites.

One memorable instance in the Iliad is when Hera seduces Zeus to distract him from the battle, allowing the Greek hero Diomedes to gain an advantage over the Trojans.

In the Odyssey, Hera ’s role is less prominent, but her presence is felt through her influence on Zeus and her support for the Greek hero Odysseus .

Zeus and Hera in Hesiod’s Works and Days

Hesiod, a Greek poet, depicts Zeus and Hera in his famous work, Works and Days.

While the main focus of the poem is on the ethical conduct of mortals, Hesiod includes references to the divine couple. Zeus is portrayed as a god who punishes those who act unjustly, while Hera is depicted as a goddess who watches over marriages and protects the sanctity of the union.

Hesiod emphasizes the importance of honoring Zeus and Hera to achieve a harmonious and prosperous life.

Zeus and Hera in Greek Tragedies and Comedies

Zeus and Hera also make appearances in Greek tragedies and comedies. Playwrights like Euripides and Aristophanes often drew inspiration from Greek mythology and incorporated the stories of Zeus and Hera into their plays.

In tragedies, Zeus and Hera ’s tumultuous relationship is often explored, highlighting themes of power, jealousy, and the consequences of human or divine defiance. Comedies, on the other hand, sometimes presented the divine couple in a more lighthearted and humorous manner, showcasing their quirks and foibles.

Overall, the presence of Zeus and Hera in Greek epics and literature adds depth and intrigue to their mythological narrative. Their interactions and dynamics influence the events of epic poems and provide insight into the complexities of human and divine relationships.

Gods and Goddesses By Pantheon

Challenge the gods in our quizzes, more than 3500 images a single click away.

Download any of our Mythology Bundles of the world!

Get your images here!

The Rocky Relationship of Zeus and Hera

Written by Greek Boston in Greek Mythology

Zeus was persistent and finally came up with a plan that would trick Hera into finally becoming his wife. Zeus was able to transform himself and turned himself into a helpless, rain-soaked bird. Hera found the poor bird and brought it to shelter and took care of it. Zeus turned himself back and Hera couldn’t help but fall in love with him. She finally agreed to be his wife.

Zeus and Hera’s wedding was the first formal marriage ceremony and was a huge occasion. It took place at the Garden of Hesperides and all of the gods and goddesses attended and brought fancy gifts. There was lots of feasting and the ceremony was the model for modern weddings.

From then on out Zeus and Hera endured a rocky relationship, caused mostly by Zeus becoming involved with and falling in love with other women. He constantly had affairs with goddesses, nymphs, and mortals. Hera became extremely jealous and spent much of her time on Mount Olympus spying on Zeus and plotting revenge if she found out that Zeus spent time with another woman. She had a violent temper and went out of her way to punish the women and their children that Zeus fathered.

When Zeus fell in love with Calisto and fathered her child, Hera turned her into a bear. To save her from being hunted by her own son (part of Hera’s plan), Zeus turned her into a constellation of stars, which became known as “Big Bear”. Their son later became the constellation “Little Bear”. When Zeus tried to disguise his lover Io to hide her from Hera, he turned her into a cow. Hera saw through the ruse and sent a biting fly to repeatedly sting her. Other notable mistresses include Danae; mother of her Perseus, Alcmena; mother of Heracles, Leda; mother of Helen of Troy and Pollux, Europa; mother of King Minos of Crete, and Ganymede; a mortal male and Trojan prince.

In addition to being very jealous, Hera was also very vain. In a competition as to who was “the fairest goddess”, Hera was extremely angry that the title went to Aphrodite. Since it was Paris of Troy that chose the winner, Hera’s reaction led to the Trojan War.

Zeus once consulted a wise man when Hera was angry with him and wanted to know how to win back her love. The wise man recommended making a wooden statue of a woman, draping it in cloth, and announcing that she was his bride. Hera removed the drapery and was delighted to see that it was a statue instead of an actual woman.

Categorized in: Greek Mythology

This post was written by Greek Boston

Share this Greek Mythology Article:

Related History and Mythology Articles You Might Be Interested In...

All About the First Hellenic Republic

Sophocles – Ancient Greek Dramatist

About Sarpedon – Hero of the Trojan War

Erato – Greek Mythological Muse of Love Poetry

- Literature Notes

- The Beginnings — Loves of Zeus

- About Mythology

- About Egyptian Mythology

- Summary and Analysis: Egyptian Mythology

- The Creation

- About Babylonian Mythology

- Summary and Analysis: Babylonian Mythology

- The Creation, the Flood, and Gilgamesh

- About Indian Mythology

- Summary and Analysis: Indian Mythology

- Indra and the Dragon

- Bhrigu and the Three Gods

- Rama and Sita and Buddha

- About Greek Mythology

- Summary and Analysis: Greek Mythology

- The Beginnings — Creation

- The Beginnings — Prometheus and Man, and The Five Ages of Man and the Flood

- The Beginnings — Poseidon, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Hermes, Demeter, and Dionysus

- The Heroes — Perseus, Bellerophon, and Heracles

- The Heroes — Jason and Theseus

- The Heroes — Meleager and Orpheus

- The Tragic Dynasties — Crete: The House Of Minos

- The Tragic Dynasties — Mycenae: The House Of Atreus

- The Tragic Dynasties — Thebes: The House of Cadmus

- The Tragic Dynasties — Athens: The House of Erichthonius

- The Trojan War — The Preliminaries, The Course of the War, The Fall of Troy, and The Returns

- The Trojan War — Odysseus' Adventures

- Other Myths

- About Roman Mythology

- Summary and Analysis: Roman Mythology

- Patriotic Legends — Aeneas and Romulus and Remus

- Love Tales — Pyramus and Thisbe, Baucis and Philemon, Pygmalion, Vertumnus and Pomona, Hero and Leander, Cupid and Psyche

- About Norse Mythology

- Summary and Analysis: Norse Mythology

- The Norse Gods — Odin, Thor, Balder, Frey, Freya, and Loki

- Beowulf, The Volsungs, and Sigurd

- About Arthurian Legends

- Summary and Analysis: Arthurian Legends

- Merlin, King Arthur, Gawain, Launcelot, Geraint, Tristram, Percivale, the Grail Quest, and the Passing of Arthur's Realm

- Critical Essays

- A Brief Look at Mythology

- Essay Questions

- Cite this Literature Note

Summary and Analysis: Greek Mythology The Beginnings — Loves of Zeus

After deposing Cronus, Zeus and his brothers drew lots to see which portion of the world would be ruled by each. Zeus thus gained the mastery of the sky, Poseidon of the seas, and Hades of the underworld. It was also decreed that earth, and Olympus in particular, would be common to all three. In addition to having the most power, Zeus gained another advantage from his position as, a sky god, since it allowed him free access to any beauty that took his fancy. Indeed, as a sky god it was expected of him to fecundate the earth; and neither goddess, nymph, nor mortal was able to resist his advances, for the most part.

Zeus had had other wives before Hera. The first was Metis (Wisdom), whom Zeus swallowed just before she gave birth to Athena because he knew that her second child would dethrone him. Yet in order to allow Athena to live, as Metis' firstborn, Zeus (in some Greek sources) had Hephaestus take an axe and cleave his forehead open, and from Zeus's head sprang Athena, fully armed. By swallowing Metis, however, Zeus had gained wisdom as part of his intrinsic nature.

His second wife, Themis (Divine Justice), gave birth to the Seasons, to Wise Laws, to Human Justice, to Peace, and to the Fates. His third wife was Eurynome, an ocean nymph, and she bore the three Graces. Zeus then was attracted by his sister Demeter, who resisted him. But he violated her in the form of a bull, and from their union came Persephone. His next wife was the Titaness Mnemosyne (Memory), who produced the Nine Muses. Leto was said to be one of Zeus's consorts. She gave birth to Artemis and Apollo after a good deal of persecution at Hera's hands.

Zeus finally became enamored of the goddess who was to become his permanent wife — Hera. After courting her unsuccessfully he changed himself into a disheveled cuckoo. When Hera took pity on the bird and held it to her breast, Zeus resumed his true form and ravished her. Hera then decided to marry him to cover her shame, and the two had a resplendent wedding worthy of the gods. It took no great foresight to see that their marriage was bound to be quarrelsome and unhappy, given Zeus's lust and Hera's jealousy.

Their union brought forth four children: Hebe, the cupbearer to the gods; Ares, the god of war; Ilithyia, a goddess of childbearing; and Hephaestus, the craftsman of the gods. Perhaps in retaliation for Zeus's giving birth to Athena. Hera claimed that Hephaestus was virgin-born. Zeus never cared much for his two legitimate sons, Ares and Hephaestus. And his two legitimate daughters were almost nonentities. One time Hephaestus interfered in a quarrel between Zeus and Hera, siding with his mother. In a rage Zeus hurled his ugly son down from Olympus to the isle of Lemnos, crippling him forever.

The arguments between Zeus and Hera were fairly frequent As Zeus continued to have one affair after another, Hera could not punish him because he was much stronger than she was. But she could avenge herself on the females with whom Zeus dallied, and she often took full advantage of this.

A number of Zeus's affairs resulted in new gods and godesses. His liaison with Metis, of course, produced the warrior goddess of wisdom and courage, Athena. One night as Hera slumbered, Zeus made love to one of the Pleiades, Maia, who gave birth to the tricky messenger of the gods, Hermes. By some accounts Zeus begat the goddess of love, Aphrodite, on the Titaness Dione. And when he took Leto as his consort he must have been married to Hera, for Hera persecuted Leto by condemning her to bear her children in a land of complete darkness. After traveling throughout Greece, Leto finally gave birth painlessly to Artemis, the virgin huntress, on the isle of Ortygia. Nine days later she gave birth to Apollo, the god of light and inspiration, on the island of Delos. Each of these new gods and goddesses were full-fledged Olympians, having had two divine parents.

One important god, however, had Zeus as a father and a mortal woman as a mother. This was Dionysus, the vine god of ecstasy, who was never granted Olympian status. His mother was the Theban princess, Semele. Zeus visited her one night in the darkness, and she knew a divine being was present and she slept with him. When it turned out that Semele was pregnant she boasted that Zeus was the father. Hera learned of this and came to Semele disguised as her nurse. Hera asked how she knew the father was Zeus, and Semele had no proof. So Hera suggested that Semele ask to see this god in his full glory. The next time Zeus visited the girl he was so delighted with her that he promised her anything she wanted. She wanted to see Zeus fully revealed. Since Zeus never broke his word, he sadly showed himself forth in his true essence, a burst of glory that utterly destroyed Semele, burning her up. Yet Zeus spared her unborn infant, sewing it up inside his thigh until it was able to emerge as the god Dionysus. His birth from Zeus's thigh alone conferred immortality on him.

Among Zeus's offspring were great heroes such as Perseus, Castor and Polydeuces, the great Heracles. Some were founders of cities or countries, like Epaphus, who founded Memphis; Arcas, who became king of Arcadia; Lacedaemon, the king of Lacedaemon and founder of Sparta. One was the wisest law-giver of his age, the first Minos. Another was a fabulous beauty, the famous Helen of Troy. And one was a monster of depravity: Tantalus, who served up his son Pelops as food to the gods. As a general rule Zeus's mortal children were distinguished for one reason or another.

On occasion their mothers were notable for something besides merely attracting Zeus with their beauty. Leda, for example, after being visited by Zeus in the form of a swan, gave birth to an egg from which came Helen and Clytemnestra, and Castor and Polydeuces. But since Leda's husband Tyndarus also made love to her shortly after Zeus, the exact paternity of these quadruplets was subject to question.

Poor Io was famous for her long persecution at the hands of Hera. Zeus fell in love with Io and seduced her under a thick blanket of cloud to keep Hera from learning of it. But Hera was no fool; she flew down from Olympus, dispersed the cloud, and found Zeus standing by a white heifer, who of course was Io. Hera calmly asked Zeus if she could have this animal, and Zeus gave it to her, reluctant to go into an explanation. But Hera knew it was Io, so she put her under guard. The watchman Argus with a hundred eyes was put in charge. Eventually Zeus sent his son Hermes to deliver lo from Argus, which was very difficult because Argus never slept. In disguise Hermes managed to put Argus to sleep with stories and flute-playing, and then Hermes killed him. As a memorial to Argus, Hera set his eyes in the tail of her pet bird, the peacock. But Hera was furious and sent a gadfly to chase Io over the earth. Still in the form of a heifer, Io ran madly from country to country, tormented by the stinging insect. At one point she came across Prometheus chained to his rock in the Caucasus, and the two victims of divine injustice discussed her plight. Prometheus pointed out that her sufferings were far from over, but that after long journeying she would reach the Nile, be changed back into human shape, give birth to Epaphus, the son of Zeus, and receive many honors. And from her descendants would come Heracles, the man who would set Prometheus free.

If Hera was diligent about punishing lo, Europa escaped her wrath scotfree. One morning this lovely daughter of the king of Sidon had a dream in which two continents in female form laid claim to her. Europa belonged to Asia by birth, but the other continent, which was nameless, said that Zeus would give Europa to her. Later, while Europa and her girl companions were frolicking by the sea, Zeus was smitten with the princess and changed himself into a marvelous bull of great handsomeness. He approached the girls so gently that they ran to play with him. Zeus knelt down and Europa climbed on his back. Then the bull charged into the sea, and on the sea journey Europa and Zeus were accompanied by strange sea creatures: Nereids, Tritons, and Poseidon himself. Europa then realized that the bull was a god in disguise and she begged Zeus not to desert her. Zeus replied that he was taking her to Crete, his original home, and that her sons from this union would be grand kings who would rule all men. In time Europa gave birth to Minos and Rhadamanthus, wise rulers who became judges in the netherworld after death. And Europa gave her name to a continent.

Despite his conquests Zeus was not always successful in his amorous pursuits. The nymph Asteria managed to resist him only by the most desperate means — changing herself into a quail, flinging herself into the sea, and becoming the floating island of Ortygia. On one occasion Zeus himself renounced the nymph Thetis when he learned that she would give birth to a son greater than its father. Further, Zeus's infatuations were not limited to women, for when he fell in love with the youthful Ganymede he had the boy abducted by his eagle and brought up to Olympus to serve as cupbearer.

In previous sections we have seen Zeus's power as king of the gods and a dispenser of justice to men, but here we see him as a procreator. As H. J. Rose has pointed out, the Greeks had a choice of making Zeus either polygamous or promiscuous because the role of All-Father was indispensable to him. Zeus had acquired wives as his worship spread from locality to locality and he had to marry each provincial earth goddess. However, polygamy was foreign to the Greeks and unacceptable, so they had to make him promiscuous. The same majestic god who fathered seven of the great Olympians also fathered a number of human beings, and many ruling or powerful families traced their lineage to Zeus. So if his battles with Hera and his deceptions lessened his dignity, that was the price the Greeks paid for their illustrious family trees.

The myths about Zeus are primarily concerned with establishing his mastery over gods and men. His predominance in the Olympian pantheon is largely asserted by the fact that he fathered seven of the major gods. Once again we see the humanization of the gods. Zeus and Hera have distinct personalities and a realistic family situation. Everything they do has an understandable motive. Thus, when Zeus changes himself into bestial forms he does so to satisfy his lust. The Greeks had a driving passion for order. They continually rationalized their myths, tried to explain obscurities, and attempted to make the fantastic elements more believable. However, in making their gods humanly comprehensible they tended to trivialize them as well, depriving them of some of their original power and mystery. One could fill several gossip columns with spicy anecdotes about the Greek gods, as though they were immortal versions of the International Set. The following myths about the gods show human qualities projected onto divinities, and many of those qualities are not of a very high moral level. Pride, greed, lust, trickery are prominent features of the Greek gods.

Previous The Beginnings — Prometheus and Man, and The Five Ages of Man and the Flood

Next The Beginnings — Poseidon, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Hermes, Demeter, and Dionysus

Hera - Queen of the Gods in Greek Mythology

- Mythology & Religion

- Figures & Events

- Ancient Languages

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- M.A., Linguistics, University of Minnesota

- B.A., Latin, University of Minnesota

In Greek mythology , the beautiful goddess Hera was queen of the Greek gods and the wife of Zeus , the king. Hera was goddess of marriage and childbirth. Since Hera's husband was Zeus, king not only of gods, but of philanderers, Hera spent a lot of time in Greek mythology angry with Zeus. So Hera is described as jealous and quarrelsome.

Hera's Jealousy

Among the more famous victims of Hera's jealousy is Hercules (aka "Heracles," whose name means the glory of Hera). Hera persecuted the famous hero from before the time he could walk for the simple reason that Zeus was his father, but another woman -- Alcmene -- was his mother. Despite the fact that Hera was not Hercules' mother, and despite her hostile actions -- such as sending snakes to kill him when he was a newborn baby, she served as his nurse when he was an infant.

Hera persecuted many of the other women Zeus seduced, in one way or another.

" The anger of Hera, who murmured terrible against all child-bearing women that bare children to Zeus.... " Theoi Hera : Callimachus, Hymn 4 to Delos 51 ff (trans. Mair) " Leto had relations with Zeus, for which she was hounded by Hera all over the earth. " Theoi Hera : Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1. 21 (trans. Aldrich)

Hera's Children

Hera is usually counted single parent mother of Hephaestus and the normal biological mother of Hebe and Ares. Their father is usually said to be her husband, Zeus, although Clark ["Who Was the Wife of Zeus?" by Arthur Bernard Clark; The Classical Review , (1906), pp. 365-378] explains the identities and births of Hebe, Ares, and Eiletheiya, goddess of childbirth, and sometimes named child of the divine couple, otherwise.

Clark argues that the king and queen of the gods had no children together.

- Hebe may have been fathered by a lettuce. The association between Hebe and Zeus may have been sexual rather than familial.

- Ares might have been conceived via a special flower from the fields of Olenus. Zeus' free admission of his paternity of Ares, Clark hints, may be only to avoid the scandal of being a cuckold.

- On her own, Hera gave birth to Hephaestus.

Parents of Hera

Like brother Zeus, Hera's parents were Cronos and Rhea, who were Titans .

In Roman mythology, the goddess Hera is known as Juno.

- Meet Hera, the Queen of the Greek Gods

- Goddesses of Greek Mythology

- Drawings of the Greco-Roman Gods and Goddesses

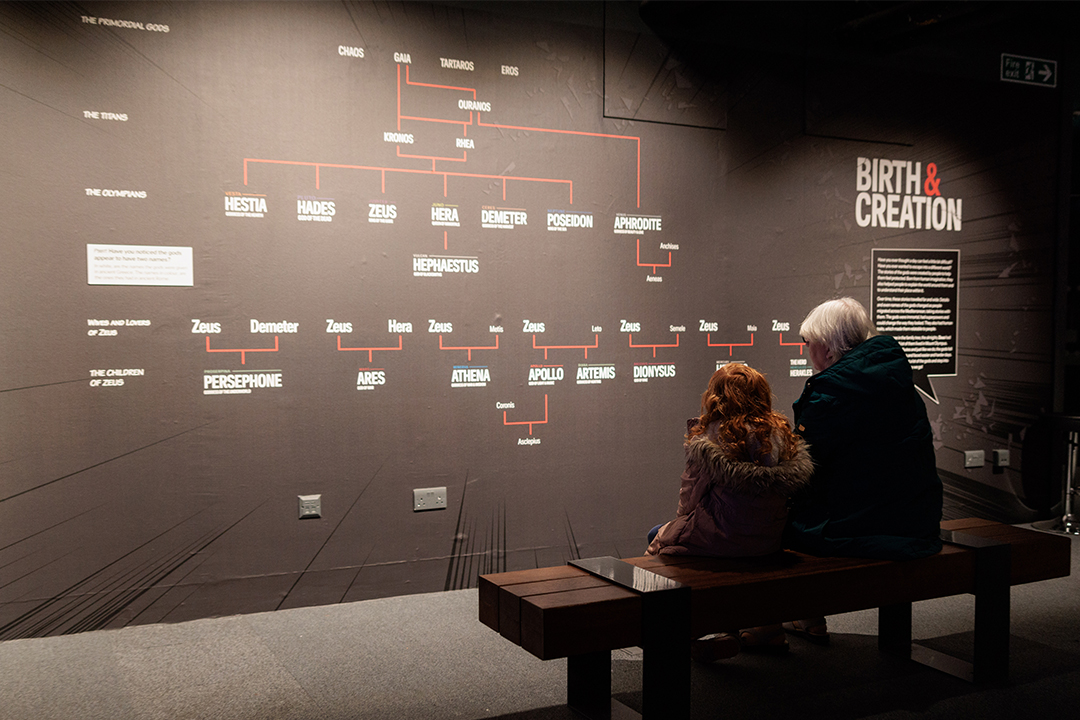

- Genealogy of the Olympic Gods

- Who Was Hercules?

- Genealogy of the First Gods

- Gods and Goddesses in Homer's Epic Poem The Iliad

- Birth of the Olympian Gods and Goddesses

- What You Need to Know About the Greek God Zeus

- Aphrodite, the Greek Goddess of Love and Beauty

- Profile of the Roman God Jupiter

- Who Are the Nymphs in Greek Mythology?

- The 10 Greatest Heroes of Greek Mythology

- A Biography of the Greek God Hades

- The Greek God Hades, Lord of the Underworld

Zeus and Hera

In the ancient pantheon of Greek gods, Zeus and Hera reign as the supreme deity couple, their names evoking the grandeur and complexity of divine relationships within the annals of mythological lore. Zeus, revered as the mighty ruler of the gods and the master of thunder and lightning, finds his eternal counterpart in Hera, the queen of the heavens and the goddess of marriage and childbirth, embodying the essence of matrimonial sanctity and familial harmony.

Table of Contents

Story of Zeus and Hera

The mythic saga of Zeus and Hera traces its origins to the tumultuous annals of ancient Greek mythology, highlighting the intricate dynamics of their divine relationship and the multifaceted nature of their immortal bond. As siblings within the pantheon of Olympian deities, Zeus and Hera shared a complex and tumultuous history, characterized by moments of both fervent passion and vehement discord, encapsulating the eternal struggle between matrimonial fidelity and the capricious nature of divine authority.

Zeus and Hera Children

The union between Zeus and Hera engendered a pantheon of legendary offspring, each bearing the imprint of their divine lineage within the realms of ancient Greek mythology. Notable among their progeny were Ares, the god of war, Hephaestus, the esteemed blacksmith of the gods, and Hebe, the goddess of youth, each embodying distinctive facets of divine prowess and mythical prowess within the cosmic hierarchy of the Olympian pantheon.

How Did Zeus and Hera Get Married

The divine union between Zeus and Hera was forged in the celestial realms of Mount Olympus, a testament to the intricate tapestry of divine diplomacy and matrimonial symbolism within the pantheon of Greek gods. According to mythic lore, Zeus, enamored by Hera’s celestial grace and regal demeanor, sought her hand in marriage as a means to solidify his reign over the Olympian deities and establish a harmonious balance within the cosmic hierarchy. Despite the tempestuous nature of their relationship, their matrimonial bond served as a celestial cornerstone, fostering a sense of stability and cosmic order within the realms of the divine pantheon.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Enable JavaScript and refresh the page to view the Center for Hellenic Studies website.

See how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

- Language/Literature

- Art/Archaeology

- Philosophy/Science

- Epigraphy/Papyrology

- Mythology/Religion

- Publications

The Center for Hellenic Studies

Seeing hera in the iliad.

Citation with persistent identifier:

Ali, Seemee. “Seeing Hera in the Iliad .” CHS Research Bulletin 3, no. 2 (2015). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:AliS.Seeing_Hera_in_the_Iliad.2015

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kFEtZF1TKHw

§1 Hera’s name appears early in the Iliad . Well before she herself speaks or even appears in the epic, she acts. Quietly and seemingly imperceptibly, she places an idea directly in Achilles’ phrénes :

ἐννῆμαρ μὲν ἀνὰ στρατὸν ᾤχετο κῆλα θεοῖο, τῇ δεκάτῃ δ’ ἀγορὴν δὲ καλέσσατο λαὸν Ἀχιλλεύς· τῷ γὰρ ἐπὶ φρεσὶ θῆκε θεὰ λευκώλενος Ἥρη κήδετο γὰρ Δαναῶν, ὅτι ῥα θνήσκοντας ὁρᾶτο. Nine days up and down the host ranged [Apollo’s] arrows, On the tenth, Achilleus called the people into assembly, A thing put into his [ phrénes ] by the goddess of the white arms, Hera: Who had pity on the Danaans when she saw them dying. (I 53-56) [1]

Hera’s final action in the epic, like her first, is similarly subtle and gentle; it is likewise easy to miss. Again, her gesture involves the phrén, a term more commonly found in the plural ( phrénes , as above), which signifies a realm of experience that is at once physiological, intellectual, and emotional. [2] In Iliad XXIV when Achilles’ divine mother, Thetis, ascends to Olympus, Hera offers her hospitality and speaks tender words to comfort Thetis’ phrén : [3]

Ἥρη δὲ χρύσεον καλὸν δέπας ἐν χερὶ θῆκε καί ῥ’ εὔφρην’ ἐπέεσσι: Θέτις δ’ ὤρεξε πιοῦσα. Hera put into her hand a beautiful golden goblet and spoke to her to comfort her [ phrén ] , and Thetis accepting drank from it. (XXIV 101-102)

Hera’s first and last actions in the Iliad are deeply interior. In the first instance, she moves the mind and heart of a young warrior to introduce civil discussion to a panicked army. In the last, she offers genuine solace to a goddess mourning the imminent death of her mortal child. The intense interiority of Hera’s divine influence, her action upon the phrénes , means that her role in an epic of such monumental scale as the Iliad can be difficult to discern. Moreover, Hera can be purposely elusive. As she herself declares, “It is hard for gods to be shown in their true shape” (χαλεποὶ δὲ θεοὶ φαίνεσθαι ἐναργεῖς, XXI, 131).

§2 Indeed, throughout the Iliad , Hera is subtle and manifold in her self-presentation. Within an instant, she can tremble like a dove (V 778) and then immediately transform herself into the bronze-voiced warrior, Stentor, whose cry has the force of fifty men’s (V 784-6). Hera’s bibliography is astonishingly slight, however; [4] her depth and complexity seem to have passed unnoticed. Her critics, particularly those writing in English, most often characterize her as a divine shrew. One recent study of Hera’s Iliadic character denounces her as “savage” and argues that the Iliad intentionally presents her as a figure of “demonic degeneracy.” [5] Another recent critic characterizes Hera as “a needy, dependent spouse.” [6]

§3 This essay departs emphatically from the communis opinio. I hope to show here that Hera in the Iliad is a seeing goddess, one who also bestows insight. Indeed, Hera’s creative vision enlarges the imaginative scope of the epic––for her noetic mode of seeing brings unity to what is otherwise disparate and heterogeneous, including the community of gods themselves.

§4 Ruth Padel defines the phr é nes as part of the “equipment of consciousness” in ancient Greek poetics . [7] Both concrete and abstract in signification, the phr é nes , she writes, “contain emotion, practical ideas, and knowledge. . . . Phr é nes are containers: they fill with menos ‘anger,’ or thūmós , ‘passion.’ . . . They are the holding center, folding the heart, holding the liver.” [8] Hera’s divine work in the Iliad focuses directly and insistently upon these vessels of mental and physical consciousness. Wherever the goddess appears, the word phr é n and its cognates also seem reliably to attend her – words such as φρονέω, “have understanding; think; comprehend”; πρόφρων, “with forward mind”; εὐφραίνω, “cheer, gladden, comfort”; and, perhaps more tangentially, φράζω, “understanding, explaining”; φράζομαι, “take counsel with.” [9]

§5 In Iliad I 53-56 (quoted above), the language describing Hera’s action is noteworthy: ἐπὶ φρεσὶ θῆκε. The verb θῆκε here means to “set, put, place.” Hera’s gesture of setting or placing clearly happens in Achilles’ phrénes . To revise only slightly Nietzsche’s formulation, the hero’s thought comes to him not when he wants, in this case, but when Hera wants. [10]

§6 What Hera places in Achilles’ phrénes is a political idea: to summon an assembly. This Hera-inspired gathering is the first deliberative assembly that takes place in the Iliad ; it is at this meeting, called to discover the cause of the devastating plague, that Agamemnon fatefully insults Achilles. Hera sees the mortal dispute and once again decisively determines its outcome from afar. Once more, the goddess quietly shapes Achilles’ calculated and reasoned response in order to avert catastrophe; she prevents Achilles from killing Agamemnon. In this instance, however, instead of remaining the invisible and anonymous author of Achilles’ thoughts and feelings, Hera begins to move into the foreground of the epic action. Thus at I 193-196, the master narrator of the Iliad shows Achilles contemplating in his phrénes and his thūmós (ὥρμαινε κατὰ φρένα καὶ κατὰ θυμόν, I 193) whether he should kill Agamemnon immediately, or, rather, whether he should check his anger (χόλον, I 192). “This is a fundamentally political decision,” David Elmer observes. [11] Because it is a political decision, one that requires deliberation and self-control, Hera intervenes.

§7 At the crucial moment, just as Achilles begins to draw his sword (I 194), Hera sends Athena to urge restraint:

ἕως ὃ ταῦθ’ ὥρμαινε κατὰ φρένα καὶ κατὰ θυμόν , ἕλκετο δ’ ἐκ κολεοῖο μέγα ξίφος, ἦλθε δ’ Ἀθήνη οὐρανόθεν: πρὸ γὰρ ἧκε θεὰ λευκώλενος Ἥρη ἄμφω ὁμῶς θυμῷ φιλέουσά τε κηδομένη τε: Now as he weighed in [ phrénes ] and [ thūmós ] these two courses and was drawing from its scabbard the great sword, Athene descended from the sky. For Hera the goddess of the white arms sent her, who loved both men equally in her heart and cared for them. (I 193-196)

The epic deliberately emphasizes Hera’s role by repeating these lines when Athena explains her sudden appearance to Achilles (I 195-6):

ἦλθον ἐγὼ παύσουσα τὸ σὸν μένος, αἴ κε πίθηαι, οὐρανόθεν: πρὸ δέ μ’ ἧκε θεὰ λευκώλενος Ἥρη ἄμφω ὁμῶς θυμῷ φιλέουσά τε κηδομένη τε: ‘I have come down to stay your anger––but will you obey me?–– from the sky; and the goddess of the white arms Hera sent me, who loves both of you equally in her heart and cares for you. (I.207-209)

Here, once again, Hera acts without being seen. We can now observe a pattern established early in the epic: In the first passage (I 53-56), Hera manifests invisibly in Achilles’ phrénes . Meanwhile, in the second and third passages quoted above (I 193-196 and I 207-209), Hera decisively intervenes in the internal drama unfolding, invisibly, within Achilles’ phrénes and in his thūmós – both in his mind and in his heart, we might say . It appears that Achilles learns of Hera’s involvement in his own interior life only when Athena explicitly tells him. [12]

§8 In each of these passages, Hera enters into the hero’s internal deliberations to instigate expressly political action. The goddess shapes Achilles’ imagination in order to achieve ends that are not obviously for his own good. Indeed, the master narrator of the epic repeatedly stresses that Hera acts through Achilles not because she loves or pities him, particularly. Rather, Hera intervenes for the Danaans and through Achilles because she pities the Greeks, generally (κήδετο γὰρ Δαναῶν, ὅτι ῥα θνήσκοντας ὁρᾶτο I 56), or, in what may amount to the same, because she loves Achilles and Agamemnon equally (ἄμφω ὁμῶς θυμῷ φιλέουσά I 196, I 207). The thoughts and feelings Hera inspires in Achilles aim at some larger, communal good––an end, moreover, that may not necessarily be good for Achilles himself, even though he is the chosen bearer of Hera’s messages. Hera’s aims are collective, political in the fundamental sense.

§9 Hera’s first intervention in Achilles’ phrénes –motivated by her care for the Greek army as a whole–necessarily illuminates her second intervention, when she prevents him from killing Agamemnon, the commander of the army. What does it mean, after all, to love equally men who are as different as Achilles and Agamemnon? In the latter event, Hera’s love for Agamemnon seems to have less to do with who Agamemnon is as an individual than with what Agamemnon represents , namely the Greek host as a whole. (Notably neither Hera nor Athena offer any reasons why Achilles himself should love Agamemnon.) Despite his manifest failings, Agamemnon is the single, unifying leader of the heterogeneous Argive host; as the lord of men, ἄναξ ἀνδρῶν (I 5), he folds many disparate constituencies into one–clumsily, to be sure, as his haplessness in Iliad II makes abundantly clear. [13] If Hera loves the leader of all the Greeks, Agamemnon, as much as she loves the one who represents what is best in all of them, Achilles, it is because she loves Greeks as such , that is, as a people, rather than as individuals.

§10 In Book II, Hera again sends Athena as her proxy to change the will of angry men by means of persuasive words. When the Greek host begins a massive, frantic retreat, it is Hera who turns them around:

ἔνθά κεν Ἀργείοισιν ὑπέρμορα νόστος ἐτύχθη εἰ μὴ Ἀθηναίην Ἥρη πρὸς μῦθον ἔειπεν: Then for the Argives a homecoming beyond fate might have been accomplished, had not Hera spoken a word to Athene (II 155-156)

Hera directs Athena to speak gentle words (ἀγανοῖς ἐπέεσσιν II 164) to each Greek soldier in order to draw him back from the ships. As in the earlier intervention with Achilles, Athena reports Hera’s words verbatim to Odysseus (II 174-181); Odysseus then effectively restores order to the troops.

§11 In Book VIII, Hera once more protects the Greeks from disaster by placing a political idea in the phrénes of a hero. This time, it is Agamemnon:

καί νύ κ’ ἐνέπρησεν πυρὶ κηλέῳ νῆας ἐΐσας, εἰ μὴ ἐπὶ φρεσὶ θῆκ’ Ἀγαμέμνονι πότνια Ἥρη αὐτῷ ποιπνύσαντι θοῶς ὀτρῦναι Ἀχαιούς. And now [Hektor] might have kindled their balanced ships with the hot flame, had not the lady Hera set it in Agamemnon’s [ phrénes ] to rush in with speed himself and stir the Achaians. (VIII 217-219)

Again, Hera’s quiet intrusion into a hero’s phrénes keeps disaster at bay for the Greek army, collectively. Agamemnon effectively rallies his men in this scene. Agamemnon’s efficacy here, with Hera’s active, if invisible, aid, stands in stark contrast to his miserable failure to rally the troops earlier, in Book II, when he is motivated by an evil dream sent by Zeus. (As we will see below, that dream presents a false image of Hera as supplicant.)

§12 Consistently in these passages, Hera’s action suggests an overlooked dimension of her character–her ability to contain and channel the passions of an army. The goddess exerts her restraining force by engaging a singular individual (Achilles at I 53-6, Odysseus at II 155-6, Agamemnon at VIII 217-219) through his phrénes . In each of the instances we have examined above, the Greek army remains an army rather than devolving into a mob, because Hera sees what is happening and knowingly, creatively acts.

§13 The hero Achilles, for his part, is well aware of Hera’s potency. In his understanding, however, she appears as a dangerous, destabilizing force on Olympus. After he breaks with Agamemnon and quits the war, Achilles reminds his divine mother, Thetis, of a story she has told him many times (πολλάκι, I 396). He recalls that Thetis once averted cosmic disaster by coming between Hera and Zeus; he now wants her to come between them once more, although he does not say so explicitly. Instead, Achilles recalls:

πολλάκι γάρ σεο πατρὸς ἐνὶ μεγάροισιν ἄκουσα εὐχομένης ὅτ’ ἔφησθα κελαινεφέϊ Κρονίωνι οἴη ἐν ἀθανάτοισιν ἀεικέα λοιγὸν ἀμῦναι, ὁππότε μιν ξυνδῆσαι Ὀλύμπιοι ἤθελον ἄλλοι Ἥρη τ’ ἠδὲ Ποσειδάων καὶ Παλλὰς Ἀθήνη: ἀλλὰ σὺ τόν γ’ ἐλθοῦσα θεὰ ὑπελύσαο δεσμῶν . . . many times in my father’s halls I have heard you making claims, when you said you only among the immortals beat aside shameful destruction from Kronos’ son the dark-misted, that time when all the other Olympians sought to bind him, Hera and Poseidon and Pallas Athene. Then you, goddess, went and set him free from his shackles . . . (I. 396-401)

Thetis has told and retold this story in Peleus’ house; now, Achilles cannily repeats it, perhaps to arouse a predictable reaction from his mother. In the story, Hera, together with Poseidon and Athena, almost succeeds in overthrowing Zeus. The ruler of the cosmos is already in shackles when Thetis arrives to liberate him. A cosmic revolution is thus forestalled.

§14 Achilles further reminds Thetis that she freed Zeus easily with the help of the hundred-handed monster Briareus. He describes Briareus (presumably just as Thetis has described him in earlier recitations) as a son who “is greater in strength than his father” (ὃ γὰρ αὖτε βίῃ οὗ πατρὸς ἀμείνων, I 404). But, in the story, Briareus actively does nothing. He simply stands next to Thetis and Zeus and rejoices in his own glory (κύδεϊ γαίων, I 405). His menacing physicality, juxtaposed with Thetis’ far less tangible power, her intelligence, deters Hera and her rebellious allies from overthrowing an otherwise impotent Zeus.

§15 As Laura Slatkin shows, [14] Thetis’ oft-repeated story is a displacement of a myth preserved by Pindar. According to a prophecy, an immortal son born to Thetis will be stronger than his immortal father; this mighty, immortal son will overthrow his no-longer-mighty father. To avert such catastrophe–which would end their cosmic power–the Olympian gods force Thetis into marriage with the mortal Peleus. [15] It seems that the tale that Thetis repeats “many times” (I 396)–a tale in which she upholds the rule of Zeus against all odds–here appears as a refracted version of her own autobiography. Briareus figures as “a sort of nightmarish variant of Achilles himself,” as Gregory Nagy observes, [16] the son who might have been stronger than his father. As with Briareus, Achilles’ mere presence is a sign that the Olympians can “read” clearly, since his mortal condition signifies Thetis’ surrender to Zeus.

§16 The cosmic truce among the gods at the beginning of the Iliad is hardly stable, it appears. Thetis’ concession to Zeus’ rule was never entirely voluntary, after all. Her cooperation with the Olympian regime remains always precarious. In the dream-logic of the story Thetis tells Achilles so many times, and which Achilles now mirrors back to her, it is Hera who rebels against Zeus. But this Hera, the Hera of Thetis’ imagination, also serves as a nightmare version of Thetis herself. Like Hera, even after Thetis concedes to Zeus’ power, she (Thetis) remains near at hand. Thetis, like Hera, does not disappear; nor does the threat she poses to Zeus vanish, either. As a goddess, Thetis is always fertile, always capable of bearing another child–even a divine one, mightier than his father. Thus Thetis, like Hera, still remains a threat to Zeus; the threat she poses is just as ominous as Hera’s in the tale Thetis repeats so “many times” to her son. She too can summon the power to overthrow Zeus. In Achilles imagination, perhaps, as well as in his mother’s, this fantasy-Hera easily transmutes into a fictive double, or twin, to Thetis. Humiliated, she still simmers with resentment; her divine power is not (or, is not yet) what it could be.

§17 The doubling of Hera and Thetis will necessarily frame the terms of Zeus’ plan to honor Achilles. Zeus cannot plausibly remember his debt to Thetis without simultaneously thinking of Hera; indeed, on both occasions when he articulates his plan, he directs his speech specifically to Hera (VIII 470-484 and XV 49-77). When Thetis comes to Olympus to plead her son’s cause, she herself is too discreet to name her opposite, Hera. But Zeus understands immediately that her appeal requires his direct confrontation with his divine spouse. Even so, as if reconciling a zero-sum account, Zeus simply cannot take into account one goddess’ (Thetis’) appeal for timē , honor, without accounting for the response of the other–Hera. [17]

§18 Zeus therefore responds to Thetis’ supplication, first, with a long and pregnant silence (I 511-512). Then, he offers his first speech in the epic. He names Hera prominently:

τὴν δὲ μέγ’ ὀχθήσας προσέφη νεφεληγερέτα Ζεύς: ἦ δὴ λοίγια ἔργ’ ὅτε μ’ ἐχθοδοπῆσαι ἐφήσεις Ἥρῃ ὅτ’ ἄν μ’ ἐρέθῃσιν ὀνειδείοις ἐπέεσσιν: ἣ δὲ καὶ αὔτως μ’ αἰεὶ ἐν ἀθανάτοισι θεοῖσι νεικεῖ, καί τέ μέ φησι μάχῃ Τρώεσσιν ἀρήγειν. σὺ μὲν νῦν αὖτις ἀπόστιχε μή σε νοήσῃ Ἥρη : ἐμοὶ δέ κε ταῦτα μελήσεται ὄφρα τελέσσω: Deeply disturbed Zeus who gathers the clouds answered her: ‘This is a disastrous matter when you set me in conflict with Hera , and she troubles me with recriminations. Since even as things are, forever among the immortals she is at me and speaks of how I help the Trojans in battle. Even so, go back again now, go away, for fear [ Hera ] see [νοήσῃ] us. I will look to these things that they be accomplished. (I 517-523)

Previously Achilles reminded Thetis of her claim that she not only saved Zeus from Hera, she saved the cosmos itself from disaster (λοιγὸν, I 398). Here, Zeus pointedly repeats Achilles’ language in describing Hera’s potential reaction to Thetis’ request as itself disastrous (λοίγια, I 518). [18] Hera’s anger, Zeus implies, will be disastrous, cosmic in its scale should she discover Zeus and Thetis together. Indeed, Zeus urges Thetis to leave Olympus before Hera sees them. The verb Zeus uses is νοήσῃ (I 532), from νοέω; it signifies mental perception or insight as well as physical seeing. At this moment, Zeus’ concern is hardly the banal anxiety of an errant husband worried that he has been discovered in a dalliance. Rather, it is a political concern, a concern for the future of his rule. And because Zeus is the ruler of the universe, it is also a cosmic concern. He wants very much to control what Hera sees and knows.

§19 The ongoing threat Hera poses to Zeus, in the “now” of the Iliad ’s story, becomes vividly clear in Book I. In the immediate instant following Thetis’ departure from Olympus, Hera makes her first appearance in propria persona . Before Hera speaks, however, the master narrator establishes the full force of her presence by means of a careful–and witty– grammatical construction:

. . . οὐδέ μιν Ἥρη ἠγνοίησεν ἰδοῦσ’ ὅτι οἱ συμφράσσατο βουλὰς ἀργυρόπεζα Θέτις θυγάτηρ ἁλίοιο γέροντος. . . . yet Hera was not ignorant, having seen how [Zeus] had been plotting counsels with Thetis the silver-footed, the daughter of the sea’s ancient, (I 536-538)

Here, once again, the epic suggests an interiority, a knowingness particular to Hera well before the audience of the epic sees or hears her. The verse first negates (with οὐδέ) the negative verb “ἠγνοίησεν” (I 537, from ἀγνοέω, “to be ignorant”; “not to perceive”) and then juxtaposes the double negative with an affirming verb of perception, ἰδοῦσ (I 537, from εἶδον, “to see, to perceive”). As with the language of phrénes and noesis above, the verb εἶδον conflates the physical and cerebral; it can mean both to see with the eyes and to perceive with the mind. Thus, before Hera speaks or acts, the master narrator makes clear that the goddess understands what is happening, in every way possible, both mentally and physically. Decidedly and emphatically, Hera is not ignorant; the language suggests that it is laughable even to imagine that she could be. She sees fully–she knows –that Zeus deliberately excludes her from his planning, even as (she reveals later) she also knows exactly what he has planned.

§20 As she addresses Zeus with her first words in the epic, Hera claims that it is the secrecy of Zeus’ planning that offends her. Hera is angry, she announces to Zeus and the assembled gods, because Zeus does not himself share with her what he thinks (νοήσῃς I 543). Throughout the epic, as we have observed, Hera works as a powerful agent in the phrénes . In the first words she utters, however, she complains to Zeus that he is thinking without her. The specific verb she uses is φρονέοντα, another phrén cognate :

τίς δ’ αὖ τοι δολομῆτα θεῶν συμφράσσατο βουλάς; αἰεί τοι φίλον ἐστὶν ἐμεῦ ἀπονόσφιν ἐόντα κρυπτάδια φρονέοντα δικαζέμεν: οὐδέ τί πώ μοι πρόφρων τέτληκας εἰπεῖν ἔπος ὅττι νοήσῃς . [Crafty] one, what god has been plotting [συμφράσσατο] counsels with you? Always it is dear to your heart in my absence to think [φρονέοντα] of secret things and decide upon them. Never have you patience frankly [πρόφρων] to speak forth to me the thing that you purpose [νοήσῃς].’ (I 540-3)

This passage is typical of those involving Hera. Again, as in the earlier scenes involving Achilles, words signifying thought and perceptivity cluster around the goddess’s name as they do in her own speech. This short passage offers συμφράσσατο (from συμ – φράζομαι, “take counsel with”) φρονέοντα (from φρονέω, to “have understanding”; to “think”; to “comprehend”); πρόφρων (“with forward mind”); νοήσῃς (“perceive, think”). [19]