- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

15 Scathing Book Reviews

History and/or admiring readers ultimately may have been kind to these works -- but these particular reviews sure weren't!

Tina is an Editor at Large for EW

FREEDOM, by Jonathan Franzen ''...a 576-page monument to insignificance.'' — The Atlantic , October 2010

THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO, by Stieg Larsson ''This is easily one of the worst books I've ever read. And bear in mind that I've read John Grisham.'' — Charleston City Paper , Aug. 13, 2008

BREAKING DAWN, by Stephenie Meyer ''The most devoted readers will no doubt try to make excuses for this botched novel, but Meyer has put a stake through the heart of her own beloved creation.'' — The Washington Post , Aug. 10, 2008

THE LOST SYMBOL, by Dan Brown ''The writing is as bad as Brown's admirers have come to expect: imagine Coke gone flat.'' — The Guardian , Sept. 20, 2009

CHRONIC CITY, by Jonathan Lethem Take your pick: The novel is variously described as ''this tedious, overstuffed novel,'' ''an insipid, cartoon version of Manhattan'' ''an irritating bore,'' and ''lame and unsatisfying.'' — The New York Times , Oct. 12, 2009

ISLAND BENEATH THE SEA, by Isabel Allende ''For all the pizzazz of the promotion and the bewitching conceit of the story, Island Beneath the Sea is abysmal.'' — The New Republic , April 28, 2010

DIARY, by Chuck Palahniuk ''Reading this is like being cornered by a dim-witted and semi-belligerent drunk possessed by an idée fixe he keeps reciting over and over again, jabbing your shoulder each time.'' — Salon , Aug. 20, 2003

BRIGHT-SIDED, by Barbara Ehrenreich ''But this short book is also padded with cheap shots, easy examples, research recycled from her earlier books and caustic reportorial stalking.'' — The New York Times , Oct. 11, 2009

TOWARD THE END OF TIME, by John Updike ''It is, of the total 25 Updike books I've read, far and away the worst, a novel so mind-bendingly clunky and self-indulgent that it's hard to believe the author let it be published in this kind of shape.'' — The New York Observer , Oct. 12, 1997

SATURDAY, by Ian McEwan '' Saturday is a dismayingly bad book. The numerous set pieces — brain operations, squash games, the encounters with Baxter, etc. — are hinged together with the subtlety of a child's Erector Set. The characters too, for all the nuzzling and cuddling and punching and manhandling in which they are made to indulge, drift in their separate spheres, together but never touching, like the dim stars of a lost galaxy.'' — The New York Review of Books , May 2005

THE WORLD IS FLAT, by Thomas Friedman ''On an ideological level, Friedman's new book is the worst, most boring kind of middlebrow horse----.'' — New York Press , April 26, 2005

DIRTY SEXY POLITICS, by Megan McCain ''It is impossible to read Dirty Sexy Politics and come away with the impression that you have read anything other than the completely unedited ramblings of an idiot.'' — The New Ledger , Sept. 13, 2010

BUSH AT WAR, by Bob Woodward ''The book does not try to be objective. It contains shifty untruths from those who collude, and represses basic factual material, gleanable from aides or from the public record, from the side of those who do not. It despises history and, as a partially ironic consequence, is outpaced by the present.'' — The Atlantic , June 2003

FALSE IMPRESSION, by Jeffrey Archer ''Jeffrey Archer poses something of a problem for reviewers. On the one hand, his popularity makes bad notices seem like high-handed snobbery; on the other, novels like this are so unspeakably awful that they elicit nothing short of anger.'' — The Guardian , March 12, 2006

THE HOUSE AT POOH CORNER, by A.A. Milne Dorothy Parker, who reviewed for The New Yorker under the nom de plume Constant Reader, dismissed Milne's sugary concoction with the famous line, ''Tonstant Weader fwowed up.'' — The New Yorker , Oct. 20, 1928

Related Articles

- Digital Media Help

- Learn at Home | Homework Center

- Meeting and Study Rooms

- Wifi & Wireless Printing

- Log In / Register

- My Library Dashboard

- My Borrowing

- Checked Out

- Borrowing History

- ILL Requests

- My Collections

- For Later Shelf

- Completed Shelf

- In Progress Shelf

- My Suggestions

- My Settings

Scathing book reviews

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

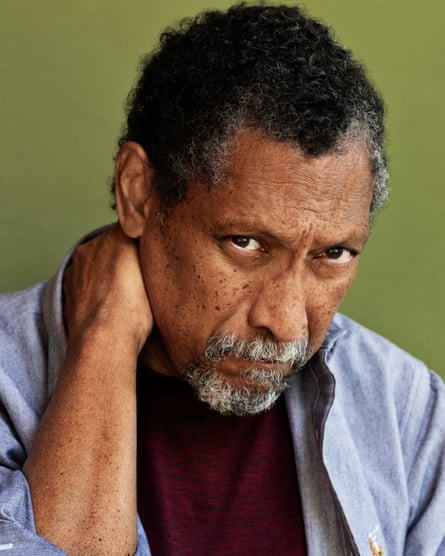

‘I’d love a scathing review’: novelist Percival Everett on American Fiction and rewriting Huckleberry Finn

His work triumphed at the Oscars, but the Booker-shortlisted author isn’t interested in acclaim. He talks to the Guardian about race, taking on Mark Twain and why there’s nothing worse than preaching to the choir

I t’s 10am on the morning of the Oscars, and Percival Everett is nowhere to be seen. We’re supposed to be meeting at his neighbourhood coffee shop in leafy South Pasadena, a suburb of Los Angeles, before he makes his way across the city for the ceremony, which begins its long march towards best picture just after lunch.

American Fiction, the film of his novel Erasure, is nominated for best adapted screenplay, up against Barbie , but tipped to win. The hour went forward last night, but surely he knows that? At 10.25am I WhatsApp him, but the message remains unread. Eventually I call. “Yes, this is Percival Everett. We’re meeting in half an hour?” The clocks, Percival, the clocks. “Ah,” he chuckles, “my fault.” He’s there in a couple of minutes, in khaki pants, grey shirt and a baseball cap, looking as if he has nothing much on today – a man not only in his own world, but his own time. When I ask why his phone didn’t update like they all do now, he says he never looks at it, and raises his wrist to flaunt a distinctively analogue watch. Hasn’t he got quite an important date later? “Oh,” he shrugs, “my wife would’ve made sure I got there on time.” That’s the novelist Danzy Senna, with whom he has two sons, aged 17 and 15.

Despite having lived in LA for more than three decades, Everett, 67, who teaches literature at the University of Southern California, doesn’t see being invited to the Oscars as somehow getting the keys to the city. It’s more like “visiting someone’s garden shed”, he says, a little bizarrely. “I’ll feel ‘Oh that’s a nice lawnmower’ and never go back.” I suggest that’s quite a prosaic image for what lots of people consider to be the most glamorous event in the universe. “I guess that betrays my feelings about glamour.”

Not that he’s ostentatiously professorial, his otherwordliness just a different way of showing off. He genuinely doesn’t seem to care: about the red carpet, accolades, critics. “I don’t go online,” he tells me. No social media? No, and no reviews. Is he not curious to see how others interpret his work? “Oh I do read scholarship – I think I learn stuff from that – but reviews I just never have any interest in.” Is it a case of protecting himself from comments that might sow doubt, or sting? “In fact, I might be interested in a really scathing review.” Why? “It might be fun? That’s gonna be kind of crazy, to be upset about a bad review. Like, what else can you expect in the world? Not everybody is gonna like my shirt.”

Acclaim isn’t a big motivator, then – instead he writes when he gets fascinated by something, which has happened often enough to produce 24 dazzlingly different novels, stories of baseball players, ranchers, mathematicians, cops and philosophising babies. And, despite his output, he finds time for plenty of other interests. Painting is the big one, and we stroll the short distance from the cafe to his studio, a windowless room in a basement complex bedecked with frenetic, abstract canvases, half-squeezed tubes of paint and impasto-slathered palettes. He’s also a skilled woodworker (he recently became obsessed with buying and repairing old mandolins), a jazz musician, and a horse and mule trainer. (Everett once told Bookforum that when he was being hired by USC a member of the faculty saw his name and exclaimed: “The last thing we need is another 50-year-old Brit,” only to be told by the receptionist that the newest professor was in fact a “black cowboy”).

Horses are no longer a part of his life – he combined working on ranches with teaching much earlier in his career – but they taught him some transferable skills. “I don’t get stressed out,” he tells me. “I think that’s from being on horses. You can’t calm down a 1,200-pound animal by getting excited.” That’s handy, because others in his position might be getting a little wound up by their work being judged in the most public way possible in just a few hours time. It’s a big day, no? “I mean, sort of. It’s not my film,” he laughs. “So, I’m excited for the director.”

He means Cord Jefferson , the former journalist who also adapted the novel, and who described showing Everett the movie as “the most frightening screening I did”. The plot differences are relatively minor, though Erasure is more complex, less certain in its conclusions. Both works tell the story of Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, a writer of abstruse fiction who fumes when he finds his retelling of Aeschylus’s The Persians filed under “African American studies” in a bookstore (“The only thing ostensibly African American [about it] was my jacket photograph”). But his commercial fortunes are transformed when he decides to submit a “ghetto” novel, ramping up the stereotypes to an obscene degree that white liberal editors nevertheless find irresistible.

Everett has spoken in the past with frustration about Erasure looming so large in his body of work. Does he still feel that way? “The only thing that ever pissed me off is that everyone agreed with it. No one took issue, or said: ‘It’s not like that.’” Why was that annoying? “I like the blowback. It’s interesting. There’s nothing worse than preaching to the choir, right?” Erasure came out in 2001, but people have taken American Fiction as a satire of modern publishing. Are the double standards he satirised still as pervasive? “There is a much greater range of work [now], and that was what I was addressing. So in some ways, there’s been a lot of change. The problem I had wasn’t with particular works, just with the fact that those were the only ones available.”

On the other hand, the thinking that led to that narrow range still very much exists. “For example, I have a friend, a director, who had some success with a film. And the next call he got was someone wanting him to direct a biopic of George Floyd. Why? Because he’s black.” That could be very irritating, of course. But it could also be a dream project. “Well,” Everett considers the point. “It’s like you’re at the office and they say: ‘We need a black person.’ Why? ‘Well, we need diversity in this room, so would you come in here?’ That’s not why you want to be invited.”

In any case, he isn’t feeling proprietorial about American Fiction: “I view it as a different work,” he tells me, though I get the impression he’s making a statement of artistic fact, rather than attempting to distance himself from the production. “I appreciate it as a different work. In spirit it’s much like the novel, but being a film, it’s not as dark.” It could have been worse: he entirely disowned the TV movie of his second book, Walk Me to the Distance. “I never saw it. I read the script, and I didn’t like it. The changes that they made were so grotesque, there was no way to embrace that at all.”

Regardless, more Everett will be coming soon to a screen near you. In 2022 he published The Trees , a genre-busting comedy about lynching, if you can imagine such a thing – part police procedural, part zombie-horror, part solemn testament to the victims of racial murder. It has been optioned for a possible “limited series” and “people are working on it” but he can’t say any more. While not surprising (the novel was shortlisted for the Booker), it will be interesting to see how a big entertainment company deals with the taboo imagery and extensive gore – “Yeah, well that’s their problem!” he laughs.

His new novel, James, is at least as likely to pique the interest of producers – partly because it adapts a cornerstone of American culture, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. While I’m teasing him about his lack of interest in Hollywood glitz, I ask if there are any writers he would be starstruck by. “[All] dead,” he replies – but offers up Samuel Butler, Chester Himes and, of course, Mark Twain. What would they talk about in any ethereal meeting? “You know, I’ve thought about that,” he says. “I don’t know if we would say much. We’d probably just talk about the landscape or something. I’d just kind of like to hear what he sees.”

In the meantime, Everett has taken the initiative with Twain’s most famous text, which tells the story of 13-year-old Huck as he navigates the Mississippi River accompanied by an enslaved man, Jim. “It’s kind of a cliche to say how important it is to American letters. It’s the first time that a novel tried to deal with the very centre of the American psyche – and that is race.” There were protest novels about slavery before then, he says, but they were narrower, focused on the institution itself. “Huck Finn, picaresque adventures aside, is really about a young American, representing America, trying to navigate this landscape, and understand how someone – his friend, actually the only father figure in the book – is also property.”

“He’s got this moral conundrum: ‘He belongs to someone and I’m doing something illegal by helping him run, but he’s my friend and a person, and he shouldn’t be a slave.’ There’s nothing more American.” Whereas Twain’s focus is tightly on Huck’s moral universe, Everett tells the other half of the story, making Jim the narrator, restoring his full name, James, and turning him into an erudite intellectual. Characteristically, one of the major plot devices is linguistic. The hokey dialect that, in Twain, renders Jim rustic and unthreatening, is revealed as a feint – a survival mechanism that the slaves use to disguise their real capacities in front of white people. One evening, James sits down in his cabin to teach some of the enslaved children a language lesson. “White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them,” he explains, the children chanting: “The better they feel, the safer we are.” He asks a little girl to translate, and is reassured when she produces a sentence in amped-up vernacular: “Da mo’ betta dey feels, da mo’ safer we be.”

Everett’s novels make abundant use of language games, conceits and disquisitions. Erasure contains a passage from Monk’s inpenetrable post-structuralist novel, and snippets of conversations between Wittgenstein and Derrida. This could be off-putting were it not for the fact that they’re often spliced with much more conventional, pacey writing, and many darkly hilarious moments – 2022’s Dr No , for example, mixes head-scratching maths with a lot of wild, Bond-inspired action. James, likewise, combines dreamed visitations from Voltaire and Locke with page-turning jeopardy. Is that kind of juxtaposition a tactic on Everett’s part, a way of licensing the intellectual gymnastics? “I don’t know if I think about it a lot. I think that any kind of intellectual understanding of the world is generated by a physical location in the world.” And by stuff happening? “Yes, by stuff happening.

It’s why I like teaching – because I get to go out into the world and be reminded that there are other people thinking different thoughts. My inclination is to stay at home and never leave. What would I write if I did that?”

L eave he does, though, and one of his more important outposts is an office in the humanities building of the University of Southern California. Unusually for LA, it’s an easy trip by metro from South Pasadena, which is why a lot of professors choose to live there. The day after the Academy Awards, the campus is glorious, its terracotta tiles and pink-brick modernist halls warming in the sun. Everett is running late, but only by a few minutes. He catches me in the lobby and we walk upstairs to a room with a view of the skyscrapers of downtown and, in the distance, the San Gabriel Mountains. American Fiction won its Oscar, and I ask if he got into the spirit of things. “Oh, that was fine. We had fun going, but we don’t need to go to that again.” No parties, then? “We went to the so-called Governors ball, which is in the ballroom right after the event. We could take it for about 10 minutes and we found a way out.”

If Everett sounds ungrateful, or grumpy, he’s not – though he’s in a little pain because of a bad back. No, he’s quick to smile, generous with his time, and simply “not the most extroverted person in the world”. He suspects that, like several of his characters, he’s “on the spectrum”. Today, we’re surrounded by another typically Everettian assortment – a framed photograph of a beloved mule, lots of books and some awards, including one from the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame. “Oxymoronic” he jokes, before explaining that, though he grew up in South Carolina, he was born in the neighbouring state. He got out of the south quickly, moving west after his undergraduate degree. “I don’t want to return and live in the south,” he told one interviewer. “I want to see the sun set on the ocean.” But when I suggest he’s no fan of that part of the world, he demurs. “That’s a little unfair. The American inclination is to find a region and blame it so it doesn’t have to feel bad as a whole. There are lots of good people there, and lots of people I’d rather not spend time with. But that’s true of everywhere.”

My attention is drawn to what looks like an elaborate sewing box. “Oh, it’s a fly tying kit.” Is fishing another one of his things? “Yes.” So you make the flies yourself? “Usually while I’m talking to students.” I find it interesting that he likes to distract part of his brain from the task at hand, and it turns out to be something of a theme. James, he says, was written “on the coffee table with Mission: Impossible going the entire time”. What? “Some network would just play the same episodes over and over. It’s just white noise for me.” We’re talking the original 1960s series, by the way, not the movie. “I don’t remember them from being a kid,” he says, and then, for perhaps the first time, becomes really animated: “but the bongo part of the [theme] is fantastic. And that’s really what got me watching. It’s an OK song but the bongo part of it, the percussive part, is incredible – the counting of it. It’s just completely mesmerising.” I’m amazed he can concentrate, but he says: “I don’t really watch. I just know what’s there. And I look up, and my game would be how quickly could I identify the episode. Just from a shot of a hand or anything.” In fact, it makes the writing easier: “It’s a distraction that allows my mind to run instead of trying to … to figure out the story.”

It remains to be seen whether critics will pick up on any subliminally incorporated plotlines from Mission: Impossible in the new book. The reviews for James, published in the US a few weeks ago, are beginning to trickle in. I mention that the Washington Post seemed to like it . “They also told me there was a New York Times review today,” Everett says, without affect. It’s only afterwards that I take a look: it’s a spectacular rave .

We return, briefly, to that Oscar. “Awards are what they are. They don’t make anything better” – unlike bongos, clearly. Being unimpressed by the event is one thing, but this is going to have a concrete effect on his life. The tour he’s about to embark on – “against my better judgment, 12 cities in 13 days” – will doubtless be sold out. There will be more interest in his work, more sales, more scrutiny. And Erasure will potentially define him far more than it did before. Does he worry, given the sheer variety of his writing, about the gravitational pull of that “African American studies” bookshelf – of, ironically, being reduced to the stereotype of “race writer”? “When people come to the work, they get what the work offers. And however you get them there, it’s OK. I don’t much worry about that. If people read anything , I’m happy. It doesn’t even have to be my work. Because if they just become readers, that’s a much better culture.”

“What is it Walt Whitman says in By Blue Ontario’s Shore?” he continues. “I’m paraphrasing, but since it’s Whitman, it doesn’t matter: if you want a better society, produce better people.” (The phrase in the poem is “Produce great Persons, the rest follows.”)

So how do you produce better people? “By helping make them smarter. Education, so they’re interested in ideas. It’d be great if somehow literary fiction could affect popular culture.” But isn’t that precisely what Erasure has done, via American Fiction? “A little bit,” he concedes. “We’ll see”. And with a bemused and friendly laugh, he’s ready to turn his attention to the next thing.

James by Percival Everett is published by Mantle. To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply.

- Percival Everett

- Film adaptations

- Oscars 2024

Most viewed

Meta Filter

"it’s his 19th book… here’s hoping it’s his last." december 22, 2022 7:47 am subscribe.

« Older The Traitor - Hunger Games in the Scottish... | It can slosh around, it can stretch, and it can... Newer »

This thread has been archived and is closed to new comments

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The Most Scathing Book Reviews of 2020

"there are no pleasures to be had here, only a reminder of things that once produced pleasure.".

In a year this bruising, this unrelentingly grim, do we really need a list of vicious pans? Doesn’t this exercise in festive schadenfreude, now in its forth year, demean us all? Can’t we just let Woody Allen, Michael Cohen, and Lionel Shriver enjoy the holiday season in peace?

The answers to those very reasonable questions are as follows: yes, no, and no.

We are permitted only one (1) day of abject villainy a year here at Book Marks —a normally kindhearted institution dedicated to helping readers find the books they’ll love by spotlighting the best in contemporary literary criticism—and, by God, we have no intention of wasting it.

Among the tarred and feathered tomes this year: Woody Allen’s exercise in toxic self-exoneration, Ernest Cline’s pop-culture shopping list, and John Bolton’s doorstopper of fatuous braggadocio. (Sadly, Sean Penn did not publish a new Bob Honey novel in 2020 so he will not making his third appearance in a row on this ignoble list. Maybe next year, Sean.)

Here they are, then, for your reading pleasure: 2020’s dirty dozen of diatribes.

Please imbibe responsibly.

“Many readers will be grateful that Woody Allen’s memoir has arrived in a time of face masks and latex gloves. So toxic is the volume that some may be tempted to rinse it in chloroxylenol before placing on a lectern 2m distant … so much of the book is harmless … Was there nobody around to tell 21st-century Woody it’s no longer all right to introduce every female acquaintance with an assessment of her physical charms?… It’s as if he’s writing from the judging panel of a Miss World competition during the Nixon administration … The more general lauding of collaborators has, at least, the virtue of being unintentionally hilarious. Every actor is wonderful. Every technician is a genius … The sense of sub-journalistic carelessness is heightened by a series of weird repetitions … The big questions are knocked back with glib quips. His outrage at the abuse accusations drowns out all other objections … Still, the stuff about his jazz band is nice.”

–Donald Clarke on Woody Allen’s Apropos of Nothing ( The Irish Times )

“DeLillo’s The Silence is downright skinny, only 116 pages, with typeface and margins a middle-schooler might use to pad his term paper … The Silence digresses, and I mean this quite literally, into a series of overlapping, stream-of-consciousness monologues … What makes The Silence such a letdown is that if the future is coming for us—and it is—it’s DeLillo who I most expected to nail the tenor of how that feels … DeLillo is so obsessed with what his characters might theorize about the disconnecting world that he forgets they might feel some things, too. They’re malfunctioning holograms, sputtering their lines, supposed avatars from the future who fail to pass themselves off as human. ”

–Hillary Kelly on Don DeLillo’s The Silence ( Vulture )

“Woodward’s writing has the mouthfeel of gravel. In Rage , he serves up heaps of that inimitable Woodward prose … He doesn’t do depth. People shuffle in and out of the Oval Office and other rooms of great importance bearing little more than fourth-rate Homeric epithets … A lack of anything remotely resembling literary ability has long been excused on the grounds that Woodward is a first-rate reporter, and first-rate reporters cannot afford the luxury of craftsmanship. The reliance on cliché is a necessity. But nobody wins when we go easy on the Bob Woodwards of this world. Lazy writing is lazy thinking, and lazy thinking is what got us into this whole mess. The greatest achievement of Rage is that its deadening incoherence is a pretty close approximation of what it has felt like to be in Washington in 2020 . To be perfectly clear, he has no feel for the city itself, or for anyone who doesn’t have a West Wing pass … The senseless drumbeat of news—that Woodward does gets right, page after page … If anything, the chaos should have pushed Woodward to condense, clarify, forge a cohesive story … Need it even be said that the challenge in interviewing Trump is not getting him to talk, but gleaning anything meaningful from the conversation? Credit goes to whoever on Woodward’s ‘team’ figured out how to season a series of nothing-burgers into what looks and smells like filet mignon … Woodward is an access journalist … Such a lack of moral curiosity is especially troubling in our debased times, when the cover of neutrality is daily abused by partisans and charlatans. Only it should not be surprising, for it has marked Woodward’s approach for ages … Rage …is a testament to what Woodward thinks of himself.”

–Alexander Nazaryan on Bob Woodward’s Rage ( The Los Angeles Times )

“The extreme tension in Warhol’s work between meaning and non-meaning has to do with random gestures, accidents, and visual noise carrying as much weight as design. Likewise, a lot that happened in Warhol’s life just sort of happened, the way lots of things happen in every life. This obvious fact, and much else that would occur to most sentient beings, has entirely eluded Blake Gopnik, whose elephantine, ill-written, nearly insensible Warhol has now been unleashed, weighing in at nine hundred pages, any of which suggests nothing so much as an incredibly prolonged, masturbatory trance of graphomania … None of this effort has produced anything resembling a fresh idea. Information that has been available for decades is rolled out as startling news, embedded in a dense lard of fatuous pedantry and vapid generalizations. Gopnik’s writing generally reads like boilerplate cribbed from bygone reviews and magazine articles, recast in a squirmy, sophomoric prose that deadens everything it touches … Gopnik’s ideal reader is someone who has never read a word about Warhol or contemporary art, seen a movie, or formed two consecutive thoughts without assistance … Warhol would shrink to about twenty pages if he simply stated what happened and left it at that … This book could appear only at a time when the bohemian mobility, sexual freedom, and cultural ferment of New York in the Sixties, Seventies, and early Eighties are not simply being forgotten, as people who were there die off, but becoming unimaginable.”

–Gary Indiana on Blake Gopnik’s Warhol ( Harper’s )

“If there is anything relevant to praise about Ready Player Two , it is how Cline inadvertently nails the inner monologue of entitled, out-of-touch tech moguls, particularly their limited understanding of how human beings actually work, their belief that deep, systematic problems have simple technological solutions, and their conviction that despite all evidence to the contrary, they are a still a hero whose haters would stop them from changing the world for the better. The book’s ostensibly happy ending feels more like a grim twist in a rejected Black Mirror episode where the characters force their faces into strained, rictus grins while eerie strings play over the credits … It feels almost redundant to say that the rest of the plot feels like a Wikipedia list of ’80s media loosely assembled into a story; that is the point of Ernest Cline’s books … There are no pleasures to be had here, only a reminder of things that once produced pleasure … Nothing about what Ready Player Two serves up is satisfying, in the same way that reading a shopping list isn’t as satisfying as eating a meal. You will never eat the meal. There is no meal. As with its predecessor, Ready Player Two will simply come to your table, tell you the names of delicious dishes cooked by other chefs, recite the ingredients they used, and then shake your hand and thank you for coming. This time, you will leave even hungrier, emptier, and poorer for the experience.”

–Laura Hudson on Ernest Cline’s Ready Player Two ( Slate )

“ It has all the same clunky, leaden sentences you remember from the first time Twilight came out in 2005 , and the same bizarre pacing, where nothing really happens until maybe 50 pages from the ending. It has the same insistence that stalking and emotional abuse is romantic, the same casual racism toward Indigenous people, and every other fault that made the franchise a general pop culture punching bag when it was at the height of its cultural saturation 10 years ago … something in this franchise spoke deeply to the hearts of thousands of girls. That something is valuable, and worth a closer look. I can only find traces of it in Midnight Sun … Meyer’s boredom is palpable. She has absolutely no interest in writing about a vampire-on-vampire game of cat-and-mouse through the wilderness … we already saw…Bella’s point of view. And it was sexier and more interesting there. There’s a reason that the first time Stephenie Meyer told this story, she chose to tell it through Bella’s eyes and not Edward’s. Once you get inside Edward’s head, you’re stuck with a serious case of diminishing returns.”

–Constance Grady on Stephanie Meyer’s Midnight Sun ( Vox )

“There are so many instances and varieties of awkward syntax I developed a taxonomy … the writing grows so lumpy and strange it sounds like nonsense poetry. I found myself flinching as I read, not from the perils the characters face, but from the mauling the English language receives … Cummins has put in the research, as she describes in her afterword, and the scenes on La Bestia are vividly conjured. Still, the book feels conspicuously like the work of an outsider. The writer has a strange, excited fascination in commenting on gradients of brown skin … The real failures of the book, however, have little to do with the writer’s identity and everything to do with her abilities as a novelist … What thin creations these characters are—and how distorted they are by the stilted prose and characterizations. The heroes grow only more heroic, the villains more villainous. The children sound like tiny prophets … The tortured sentences aside, American Dirt is enviably easy to read. It is determinedly apolitical. The deep roots of these forced migrations are never interrogated; the American reader can read without fear of uncomfortable self-reproach. It asks only for us to accept that ‘these people are people,’ while giving us the saintly to root for and the barbarous to deplore—and then congratulating us for caring.”

–Parul Sehgal on Jeaninne Cummins’s American Dirt ( The New York Times )

“The sex scenes are both startling and pedestrian, frank and prim. They’re titillating, like celebrity gossip, and excruciating, like walking in on your parents … The narration is so stilted, so dorky, it inspires fondness … [a] subplot, pitting white feminism against racial justice, feels dutiful, an acknowledgment that no political career could be stainless … characterization feels undermotivated, bloodless—as if anyone would believe that such aspirations are something a person can fall into accidentally, or by some providence, rather than by her own design. This idea of political striving, parked at the intersection of Tracy Flick and Leslie Knope, is possibly endearing and conspicuously small-bore. It refuses to admit anything that might be termed ideology. But perhaps that’s to be expected. More peculiarly, Rodham lacks drama. In the age of the #Girlboss, when appetite and excess are lauded as feminist ends in themselves, is it possible to make women’s ambition seem not just benign but even inert? … With deft economy, Sittenfeld demonstrates how easy it is to get stuck in even the dumbest traps … But blown up to the scale of professional politics, her fine-grained observations lose resolution. In Rodham , the characters walk around radiating divine simplicity … Bland, faultless equanimity constitutes the book’s dominant tone … The…revisionism just ends up insulting everybody’s intelligence. ”

–Sophia Nguyen on Curtis Sittenfeld’s Rodham ( The Nation )

“… a would-be-funny novel were it not so obviously constructed as a platform for Shriver’s ideological positions. All of Shriver’s gripes with the world, about wokeness and political correctness and affirmative action, are in there—tedious long bits relished by the writer but not the reader. In using her characters and circumstances as a launchpad for her invective, Shriver seems to have forgotten a basic rule of fiction writing: the author’s allegiance is to the reader rather than to the authorial self … Behind the faux-bravado, the feckless provocateur, I would bet, is a very frightened woman, scared of losing her money, her entitlement, and her relevance, a Shriver becoming merely shriveled, unable to deliver the authenticity she claims to craves in others … As many fans of the Shriver oeuvre like to reminisce, a New York Times review of The Mandibles called her the Cassandra of American Letters. A more apt, more relevant characterization of Lionel Shriver as she exists today would be the Karen of American Letters, a disgruntled literary scold who uses her privilege against others who are seen as threats. She brings the I would like to speak with the manager attitude to the publishing world. Her voice cries out for a return to the days when whiteness was great, its dominance unquestioned.”

–Rafia Zakaria on Lionel Shriver’s The Motion of the Body Through Space ( The Baffler )

“The ‘lost memoir’ of Lou Gehrig is like a bowl of lukewarm oatmeal. It can fortify innocent youths, and it might soothe cranky dyspeptics. But it is bland mush … Some of the worst baseball writing over the past century and a half has trafficked in such sentimentality, casting athletes as exemplars of character. Gehrig’s account is full of such goop … In Gehrig’s defense, he was not writing for posterity … Gaff’s discovery offers a glance at Gehrig as he burst into the American consciousness at the height of the Roaring Twenties … But the memoir offers little insight into Gehrig … Gehrig’s ghostwritten account stays at the surface, coating the sport in myth … In his introduction and biographical essay, Gaff fails to probe how and why ghostwriting journalists crafted these popular columns. Instead he offers unsubstantiated reassurances about the authenticity of Gehrig’s tale … That naive slushiness belongs in the 1920s, not the 2020s.”

–Aram Goudsouzian on Lou Gherig’s The Lost Memoir ( The Washington Post )

“ [A] revolting, contradictory, redundant and transparently faux-penitent memoir … While he does proffer the eye-popping details and anecdotes required in any Trump tell-all, Cohen reveals little about Trump that is not already widely understood. Disloyal is an exercise in affirmation, not revelation … Cohen revels in how much they share in common, and still channels The Art of the Deal … The book is getting attention for its criticisms of the president. But Disloyal doubles as Cohen’s unwitting homage to the ways of Donald Trump … The whole thing is written as a lament—but it’s really a lament that it’s over, a lament that he got caught.”

–Carlos Lozada on Michael Cohen’s Disloyal ( The Washington Post )

“… almost five hundred pages of bumptious recitation, fatuous braggadocio, and lame attempts at wit … It’s hard to be cool when you’re John Bolton, and evidently almost as hard not to be outright offensive. This emerges in his painfully maladroit efforts to lend color to a turgid narrative preoccupied with self-flattery and score-settling … Bolton also has an unfortunate penchant for defensive self-justification … Even more trying are his sour, stilted witticisms, some of which he feels compelled to point out are supposed to be funny … He’s (a little) funnier when he caricatures himself by casually playing the curmudgeon … If Bolton has shown a dash of rectitude, he has also revealed a surfeit of blinding egomania.”

–Jonathan Stevenson on John Bolton’s The Room Where It Happened ( The New York Review of Books )

Craving more bilious book reviews? Reacquaint yourself with The Most Scathing Book Reviews of 2017 , 2018 , and 2019

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Previous Article

Next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Sarah Broom: 'We Are Making Art for Each Other and for Our Survival'

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Picture This

George takei 'lost freedom' some 80 years ago – now he's written that story for kids.

Samantha Balaban

George Takei was just 4 years old when when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066:

"I hereby authorize and direct the Secretary of War, and the Military Commanders... to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded..."

It was Feb. 19, 1942. Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor two months earlier; For looking like the enemy, Japanese and Japanese American people in the U.S. were now considered "enemy combatants" and the executive order authorized the government to forcibly remove approximately 125,000 people from their homes and relocate them to prison camps around the country.

Book Reviews

George takei recalls time in an american internment camp in 'they called us enemy'.

Star Trek actor George Takei has written about this time in his life before — once in an autobiography, then in a graphic memoir, and now in his new children's book, My Lost Freedom.

It's about the years he and his mom, dad, brother and baby sister spent in a string of prison camps: swampy Camp Rohwer in Arkansas, desolate Tule Lake in northern California. But first, they were taken from their home, driven to the Santa Anita racetrack and forced to live in horse stalls while the camps were being built.

"The horse stalls were pungent," Takei remembers, "overwhelming with the stench of horse manure. The air was full of flies, buzzing. My mother, I remember, kept mumbling 'So humiliating. So humiliating.'"

He says, "Michelle's drawing really captured the degradation our family was reduced to."

Michelle is Michelle Lee, the illustrator — and researcher — for the book. Lee relied heavily on Takei's text and his excellent memory, but it was the research that both agree really brought the art to life.

"I'm telling it from the perspective of a senior citizen," Takei, 87, laughs. "I really had to wring my brains to try to remember some of the details."

So Takei took Lee to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, where he is a member of the board. They had lunch in Little Tokyo, got to know each other, met with the educational director, and looked at the exhibits. Then Lee started digging into the archives.

Movie Interviews

From 'star trek' to lgbt spokesman, what it takes 'to be takei'.

"I looked for primary sources that showed what life was like because I feel like that humanizes it a lot more," Lee explains. She found some color photographs taken by Bill Manbo, who had smuggled his camera into the internment camp at Heart Mountain in Wyoming. "While I was painting the book, I tried as much to depict George and his family just going about their lives under these really difficult circumstances."

Takei says he was impressed with how Lee managed to capture his parents: his father, the reluctant leader and his mother, a fashion icon in her hats and furs. "This has been the first time that I've had to depict real people," Lee adds.

To get a feel for 1940s fashion, Lee says she looked at old Sears catalogues. "What are people wearing? All the men are wearing suits. What kind of colors were clothes back then."

But a lot of information has also been lost — Lee wasn't able to see, for example, where Takei and his family lived in Arkansas because the barracks at Camp Rohwer have been torn down — there's a museum there now. "I didn't actually come across too many photos of the interior of the barracks," says Lee. "The ones I did come across were very staged."

She did, however, find the original floor plans for the barracks at Jerome Camp, also in Arkansas. "I actually printed the floorplan out and then built up a little model just to see what the space was actually like," Lee says. "I think it just emphasized how small of a space this is that whole families were crammed into."

One illustration in the book shows the work that Takei's mother put in to make that barrack — no more than tar paper and boards stuck together — a home.

"She gathered rags and tore them up into strips and braided them into rugs so that we would be stepping on something warm," Takei remembers. She found army surplus fabrics and sewed curtains for the windows. She took plant branches that had fallen off the nearby trees and made decorative sculptures. She asked a friendly neighbor to build a table and chairs.

"You drew the home that my mother made out of that raw space, Takei tells Lee. "That was wonderful."

Michelle Lee painted the art for My Lost Freedom using watercolor, gouache and colored pencils. Most of the illustrations have a very warm palette, but ever-present are the barbed wire fences and the guard towers. "There's a lot of fencing and bars," Lee explains. "That was kind of the motif that I was using throughout the book... A lot of vertical and horizontal patterns to kind of emphasize just how overbearing it was."

Takei says one of his favorite drawings in the book is a scene of him and his brother, Henry, playing by a culvert.

Asian American And Pacific Islander Heritage Month 2022

George takei got reparations. he says they 'strengthen the integrity of america'.

"Camp Rohwer was a strange and magical place," Takei writes. "We'd never seen trees rising out of murky waters or such colorful butterflies. Our block was surrounded by a drainage ditch, home to tiny, wiggly black fishies. I scooped them up into a jar.

One morning they had funny bumps. Then they lost their tails and their legs popped out. They turned into frogs!"

"They're just two children among many children who were imprisoned at these camps," says Lee, "and to them, perhaps, aspects of being there were just fun." The illustration depicts both childlike wonder and — still, always — a sense of foreboding. Butterflies fly around a barbed wire fence. A bright sun shines on large, dark swamp trees. Kids play in the shadow of a guard tower.

"There's so much that you tell in that one picture," says Takei. "That's the art."

"So many of your memories are of how perceptive you are to things that are going on around you," adds Lee, "but also still approaching things from a child's perspective."

Even though the events in My Lost Freedom took place more than 80 years ago, illustrator Michelle Lee and author George Takei say the story is still very relevant today.

"These themes of displacement and uprooting of communities from one place to another — these are things that are constantly happening," says Lee. Because of war and because of political decisions ... those themes aren't uncommon. They're universal."

Takei agrees. "People need to know the lessons and learn that lesson and apply it to hard times today. And we hope that a lot of people get the book and read it to their children or read it to other children and act on it."

He's done his job, he says, now the readers have their job.

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

- Japanese internment

- picture books

- children's books

- George Takei

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Today's FT newspaper for easy reading on any device. This does not include ft.com or FT App access.

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- Videos & Podcasts

- FT App on Android & iOS

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Premium newsletters

- Weekday Print Edition

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Premium Digital

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Everything in Print

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

Challengers

Tashi, a former tennis prodigy turned coach is married to a champion on a losing streak. Her strategy for her husband's redemption takes a surprising turn when he must face off against his f... Read all Tashi, a former tennis prodigy turned coach is married to a champion on a losing streak. Her strategy for her husband's redemption takes a surprising turn when he must face off against his former best friend and Tashi's former boyfriend. Tashi, a former tennis prodigy turned coach is married to a champion on a losing streak. Her strategy for her husband's redemption takes a surprising turn when he must face off against his former best friend and Tashi's former boyfriend.

- Luca Guadagnino

- Justin Kuritzkes

- Josh O'Connor

- 35 User reviews

- 91 Critic reviews

- 85 Metascore

- 1 nomination

- Tashi Donaldson

- Art Donaldson

- Patrick Zweig

- Umpire (New Rochelle Final)

- Art's Physiotherapist

- Art's Security Guard

- (as a different name)

- Tashi's Mother

- Line Judge (New Rochelle Final)

- TV Sports Commentator (Atlanta 2019)

- Leo Du Marier

- Woman With Headset (Atlanta 2019)

- Motel Front Desk Clerk

- Motel Husband

- New Rochelle Parking Lot Guard

- USTA Official …

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

More like this

Did you know

- Trivia To prepare for her role, Zendaya spent three months with pro tennis player-turned-coach, Brad Gilbert .

Tashi Donaldson : I'm taking such good care of my little white boys.

- Connections Referenced in OWV Updates: The Seventh OWV Awards - Last Update of 2022 (2022)

User reviews 35

- PedroPires90

- Apr 22, 2024

- When will Challengers be released? Powered by Alexa

- April 26, 2024 (United States)

- United States

- Những Kẻ Thách Đấu

- Boston, Massachusetts, USA

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM)

- Pascal Pictures

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Technical specs

- Runtime 2 hours 11 minutes

- Dolby Digital

- Dolby Atmos

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed

- Victor Mukhin

Victor M. Mukhin was born in 1946 in the town of Orsk, Russia. In 1970 he graduated the Technological Institute in Leningrad. Victor M. Mukhin was directed to work to the scientific-industrial organization "Neorganika" (Elektrostal, Moscow region) where he is working during 47 years, at present as the head of the laboratory of carbon sorbents. Victor M. Mukhin defended a Ph. D. thesis and a doctoral thesis at the Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia (in 1979 and 1997 accordingly). Professor of Mendeleev University of Chemical Technology of Russia. Scientific interests: production, investigation and application of active carbons, technological and ecological carbon-adsorptive processes, environmental protection, production of ecologically clean food.

Title : Active carbons as nanoporous materials for solving of environmental problems

Quick links.

- Conference Brochure

- Tentative Program

Evil Does Not Exist is an eerie, modern-day fable by Oscar-winning director Ryusuke Hamaguchi

Eerie and entrancing in equal measure, this contemporary sylvan fable from Ryusuke Hamaguchi is one of the most deceptively beautiful movies of the year so far.

Its glacial, near-wordless opening act documents the routines of Takumi (Hitoshi Omika), a widower keenly attuned to a lifestyle of quiet subsistence. In the icy mountains surrounding Mizubiki (a fictional Japanese village that's driving distance from Tokyo), Takumi spends his days chopping wood for his hearth and gathering crystalline spring water for the local udon shop.

Hamaguchi's depiction of this picture-book idyll gently unravels: first, with the distant gunshots of unseen deer hunters; second, with the realisation that Takumi's forgotten to pick up his daughter Hana (Ryo Nishikawa) from school again.

The film's story soon comes into focus with the announcement of a more pressing existential threat: the creation of a glamping site in Mizubiki for nearby city-slickers.

While the set-up suggests a familiar David-versus-Goliath battle across city lines and class divisions, the resulting social drama fractures into a series of unexpected, increasingly precarious turns – all culminating in a disquieting finale that evades straightforward interpretation.

At the centre of Evil Does Not Exist is an extended community meeting between the village's inhabitants and two representatives of the proposed development, Mayuzumi (Ayaka Shibutani; Happy Hour) and Takahashi (Ryuji Kosaka). In a brief dig at showbiz, it's revealed that both are employees of a talent agency whose boss is looking to cash in on a pandemic subsidy; needless to say, they're in embarrassingly over their heads.

Ryusuke Hamaguchi's films share a keenly observational quality. His previous feature, Drive My Car (which took home best international feature film in 2022 and earned the very first best picture nomination for a Japanese film among its four Oscar nominations), follows another quietly grieving widower who directs a production of Uncle Vanya.

The auditions and rehearsals in the film are played out with a documentary-like attention to procedure that often recalled Louis Malle's recording of Vanya on 42nd Street.

The community meeting in Evil Does Not Exist has a similar effect in its unfussy filming, which employs longer takes and minimal camera movement — though the spectacle of Mizubiki's inhabitants excoriating the agency's ill-conceived plans crosses over into cringe comedy.

Beyond the inherent contradiction of conducting a serious dialogue about glamping – a deeply unattractive portmanteau with no Japanese equivalent – the session sees arguments erupt over fire risks, promises of boosting the local economy, and the amount of sewage that should be allowed to pollute a town's fresh water supply.

While there's more than a tinge of schadenfreude to the near-ritualistic humiliation of the representatives, it's undercut by a disheartening inevitability. Impassioned pleas are stonewalled by feeble pledges to take feedback on board; the conversation is all but a formality.

The film isn't unsympathetic to Mayuzumi and Takahashi, though, whose actions drive the film's second half. Hamaguchi understands that his audience's perspective (as well as his own) is better reflected by the hapless urbanite reps than a self-sufficient survivalist like Takumi.

Evil Does Not Exist can be funny in the director's signature offhand manner – a quality evoked from the title itself – and its commentary is made stronger by his resistance to caricature. Even its most overt antagonist, a team project leader fluent in corporate speak who's glimpsed calling into a Google Hangout from his car, is presented with a scathing accuracy.

As the film progresses, concerns over the immediate threat posed by the agency are eclipsed by a troubled reflection on Mizubiki's delicate ecosystem. The camera lingers on the mountain's suffocating vastness, its rotting animal corpses and its piercing thorns, lacing the lush imagery with a subtle but unmistakeable menace; the methodical pacing gradually oozes with dread.

Evil Does Not Exist was initially conceived as a visual accompaniment to a live performance by musician Eiko Ishibashi so, unsurprisingly, her music is intrinsic to the film's uniquely haunting tone. Initially recalling the sonorous string compositions of Max Richter, the score descends into jarring dissonance and incorporates sparse electronic sounds. Just as important to the score is the film's sudden, razor-sharp cuts, which mercilessly disrupt its lull.

At times, the film recalls The Curse, Nathan Fielder and Benny Safdie's recent Paramount+ miniseries. Despite being completely different in tone, both narratives of class warfare, guilt and a perversion of the natural world are approached with a refreshing strangeness. Such themes have become rocket fuel for the recent cultural landscape, yet rarely is this material allowed to feel genuinely, menacingly abstract.

It's hard to imagine that Evil Does Not Exist will attain the status of Hamaguchi's previous Oscar darling film – which is precisely what makes the film so exciting. It's a daring creative pivot that spells out a rich future for the director.

But for all its surprises and enigmas, it's not an inaccessible film. Audiences who let themselves submit to its irresistible, hypnotic rhythms will be rewarded by a film that inspires genuine contemplation, however troubling its conclusions may be.

Evil Does Not Exist is in cinemas now.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

New sexy tennis film challengers a 'libidinous spectacle' and 'unabashed pleasure'.

When Saigon fell in 1975, Vietnamese movie star Kieu Chinh began calling her famous friends

Late Night with the Devil invites a demon onto a 70s talk show, with disastrous consequences

- Arts, Culture and Entertainment

- Film (Arts and Entertainment)

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

The Most Scathing Book Reviews of 2022

"reading this book reminded me of watching a cat lick a dog’s eye goo".

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

‘Tis the season for schadenfreude. Yes, for the sixth year running, we’ve emerged from the bowels of the book review mines trailing behind us an oozing sack of pans—each one riper and more wince-inducing that the last.

Among the books being gored and devoured by feral hogs this year: Jared Kushner’s soulless work of sycophancy, John Boyne’s shameless sequel to The Boy in the Striped Pajamas , and Hanya Yanighara’s “anti-accomplishment” doorstopper.

So here they are, in their fabulously festering fulsomeness: the most scathing book reviews of 2022.

“It’s a title that, in its thoroughgoing lack of self-awareness, matches this book’s contents … He betrays little cognizance that he was in demand because, as a landslide of other reporting has demonstrated, he was in over his head, unable to curb his avarice, a cocky young real estate heir who happened to unwrap a lot of Big Macs beside his father-in-law … Breaking History is an earnest and soulless—Kushner looks like a mannequin, and he writes like one—and peculiarly selective appraisal of Donald J. Trump’s term in office. Kushner almost entirely ignores the chaos, the alienation of allies, the breaking of laws and norms, the flirtations with dictators, the comprehensive loss of America’s moral leadership … This book is like a tour of a once majestic 18th-century wooden house, now burned to its foundations, that focuses solely on, and rejoices in, what’s left amid the ashes … Reading this book reminded me of watching a cat lick a dog’s eye goo … The tone is college admissions essay … Kushner, poignantly, repeatedly beats his own drum … A therapist might call these cries for help … The bulk of Breaking History —at nearly 500 pages, it’s a slog—goes deeply into the weeds … What a queasy-making book to have in your hands.”

–Dwight Garner on Jared Kushner’s Breaking History: A White House Memoir ( The New York Times )

“ The Philosophy of Modern Song is a mouthful, a phrase that puts on airs. It asserts that the book is an important work, a tome that merits a place on your loftiest library shelf, up in the thin air where you keep the leather-bound, gilt-edged stuff … But the title is also a wisecrack, too puffed up and self-important to be taken at face value … As a work of prose, The Philosophy of Modern Song is relentless. It rip-snorts along, charging from song to song, idea to idea. Dylan can write what journalists call a great lede: a first sentence that detonates like a hand grenade … What does all this add up to? Not quite a philosophy of modern song, or at least not a coherent one. But coherence isn’t what you want from Bob Dylan … You have to plow through 46 chapters before encountering a song by a female artist … Yet women loom large in his consciousness and are omnipresent in his pages—appearing in such monstrous form, evoked in language so marinated in misogyny, that, reading The Philosophy of Modern Song, I began to feel like a therapist, sneaking glances at my watch while the crackpot on the couch blurts one creepy fantasy after another … It’s a bummer, to put it mildly, to find a Nobel laureate…mixing metaphors and spouting nonsense like an elderly uncle who bulk-emails links to Fox News segments.”

–Jody Rosen on Bob Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song ( The Los Angeles Times )

“ Moshfegh’s own sacraments involve a different orifice, so you will forgive her if her search has led her up her own ass … At first glance, Lapvona is the most disgusting thing Moshfegh has ever written…Yet Moshfegh’s trusty razor can feel oddly blunted in Lapvona . In part, her characteristic incisiveness is dulled by her decision to forgo the first person, in favor of more than a dozen centers of consciousness. This diminishment is also a curious effect of Lapvona itself … Lapvona is the clearest indication yet that the desired effect of Moshfegh’s fiction is not shock but sympathy. Like Hamlet, she must be cruel in order to be kind. Her protagonists are gross and abrasive because they have already begun to molt; peel back their blistering misanthropy and you will find lonely, sensitive people who are in this world but not of it, desperate to transform, ascend, escape … This is the problem with writing to wake people up: Your ideal reader is inevitably asleep. Even if such readers exist, there is no reason to write books for them—not because novels are for the elite but because the first assumption of every novel must be that the reader will infinitely exceed it. Fear of the reader, not of God, is the beginning of literature. Deep down, Moshfegh knows this….Yet the novelist continues to write as if her readers are fundamentally beneath her; as if they, unlike her, have never stopped to consider that the world may be bullshit; as if they must be steered, tricked, or cajoled into knowledge by those whom the universe has seen fit to appoint as their shepherds … It’s a shame. Moshfegh dirt is good dirt. But the author of Lapvona is not an iconoclast; she is a nun. Behind the carefully cultivated persona of arrogant genius, past the disgusting pleasures of her fiction and bland heresies of her politics, wedged just above her not inconsiderable talent, there sits a small, hardened lump of piety. She may truly be a great American novelist one day, if only she learns to be less important. Until then, Moshfegh remains a servant of the highest god there is: herself.”

–Andrea Long Chu on Ottessa Moshfegh’s Lapvona ( Vulture )

“Reading it is like immersive theatre: one of those elaborate warehouse productions where you stumble about from tableau to tableau, trying to piece the story together … The novel is long on atmosphere and short on sense. There are slick, movie-style conversations with a private investigator, a Vietnam vet, and a trans woman; long lunches with a garrulous criminal friend; flashbacks to Alicia’s hallucinations; the obligatory bit of survivalism (would it even be a McCarthy novel without an episode involving tinned foods and roadkill?) … James Joyce is invoked. An oblique reminder that great literature requires hard work? But McCarthy’s difficulty is perverse. The decision to open The Passenger with an impenetrable conversation between Alicia and her hallucinations; the quantum mechanics; the pinball structure; the confusing dialogue—all this just makes the novel hard to read. Nothing meaningful is gained. It’s a shame because at times these books are more interesting than McCarthy’s key works … We think these books are unflinching. Really, they are kitsch: McCarthy’s is an art of exaggeration. A con trick is being practised … That’s how you garner comparisons to Hemingway and Faulkner—when, in fact, you’re a mediocre hybrid of both .”

–Claire Lowdon on Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger ( The Sunday Times )

“With his latest treacly tome All the Broken Places— complete with title so maudlin it preempts all mockery—Boyne has gifted us with a Holocaust novel so self-indulgent, so grossly stereotyped, so shameless and insipid that one is almost astonished that he has dared … This is not literature. As a grown-up sequel to children’s trash, All the Broken Places serves two roles. First, to demonstrate that Boyne definitely did not think that the Germans were innocent, definitely knew they were ‘complicit’ and ‘guilty’ and that history is ‘complicated,’ etc, thanks very much. Second, to serve as a sort of fan fiction for those peculiar adults who long for the comfort of a childhood favorite. As to this first goal, at least, it is a consummate failure, a wildly simplified narrative that misrepresents the extent of Nazi ideology. As in The Boy in the Striped Pajamas , Boyne underestimates the family’s awareness of the Holocaust, lending his German characters an exaggerated naivety, or implausible deniability … Boyne flaunts a teenager’s understanding of the causes and consequences of the Second World War … As with so much Holocaust fiction All the Broken Places utterly fails in its stated purpose: making the next generation slightly less likely to participate in the next genocide…Boyne’s reduction of Nazi ideology to a fringe belief, expressed in infrequent outbursts—’those filthy Jews’—is all the more absurd now that he’s writing for grown-ups … We don’t need anyone to teach us how to recognize the barefaced devil; the danger is the insidious and gradual creep of violence into the civilised and everyday. This is what the philosopher Theodor Adorno’s dictum—’To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’—warned of: art unable to recognise the break the Holocaust represented with the past, afraid to apprehend the failure of the civilising project. With this childish drivel in which the villains and victims come labelled and sorted, Boyne yet again seems immune to its lessons.”

–Ann Manov on John Boyne’s All the Broken Places ( The New Statesman )

“99 years old, but still, still pushing out the kind of platitudes that not only can be used to excuse the most evil people in the history of the species but that are designed to do exactly that…This rhetoric-as-strategy is obvious right from this book’s cast of characters…A reader might first wonder what Konrad Adenauer is doing drawn among these heartless hinds, but eyebrows might raise at de Gaulle and even Sadat as well…A moment’s thought reveals the beady-eyed rationale behind this grouping; it’s not to pull down good men, it’s to raise up genuine fire-eyed black-pelted yellow-fanged monsters…Henry Kissinger might not be able to climb a flight of stairs anymore, but he’s still capable of telling a lie before he’s even finished his Table of Contents…As he’s winding up this ghastly, conscienceless book, Kissinger contentedly admits that his subjects weren’t always popular…Not everyone admired them or ‘subscribed to their policies’…Sometimes, in fact, they faced resistance, and their separate memories still sometimes face such resistance…Almost like there might be debate about their legacies, or something… Leadership might very well be Kissinger’s most mandarin-hateful book, even surpassing 2014’s truly odious World Power … It’s his 19th book…Here’s hoping it’s his last. ”

–Steve Donoghue on Henry Kissinger’s Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy ( Open Letters Review )

“ To Paradise is so unusually terrible that it is a sort of anti-accomplishment, the rare book that manages to combine the fey simplicity of a children’s tale with near unreadable feats of convolution . It is too juvenile to attract serious adult readers and too obtuse to aspire to popular appeal. If A Little Life dragged and self-dramatized, at least it did so via a welter of readily legible, melodramatic thrills. But soap opera fanatics will fare no better with To Paradise ’s contortions than will seasoned belletrists. There is nothing to recommend it to anyone. As I trudged through the novel’s 700 pages, I found myself nostalgic for books plagued only by quaint defects, such as confusing descriptions and characters who behave inconsistently – not that Yanagihara, who has a special gift for garbled metaphors and bizarrely specific yet impenetrable imagery, spares us such infelicities … it is hard to summon the will to enumerate To Paradise ’s thematic or even stylistic shortcomings, for its basic construction is so irretrievably botched as to eclipse the rest of its defects. The fundamental problem is simple and devastating: the book does not make any sense … Aside from its sheer incoherence, its most notable feature is only its punishing length. On and on it goes, sprouting new subplots, amassing new contrivances. Anyone must have a brain of stone to finish it without shedding tears of relief.”

–Becca Rothfeld on Hanya Yanagihara’s To Paradise ( Times Literary Supplement )

“Viral success has emboldened [Taddeo] to abandon everything patient and methodical in her investigation of women’s darker appetites in favour of the literary equivalent of chasing clicks … Ghost Lover is a nine-course tasting menu that is all spice and no flavour … The main dish is always the same facile serving of female jealousy. In every effortfully flippant tale, self-conscious women compete to be the most desirable female in the room … At least the proper nouns denote actual things. When Taddeo attempts metaphor, we run into more serious trouble … Throughout, Taddeo rams words together in unexpected ways. ‘His voice turned throaty, filled with wetness and trees.’ Trees? … Perhaps Taddeo has read Lolita and feels excited about experimenting with the English language. Only it feels more as if she has done the experimenting in another tongue, Finnish or Swahili, perhaps, then run a series of untranslatable local sayings through Google Translate … In the course of producing this Goop noir, Taddeo has abandoned any interest in women as complex, conflicted humans. Her characters are myopically focused on blow-dries, blow jobs and brow tints … Inspires depression.”

–Johanna Thomas-Corr on Lisa Taddeo’s Ghost Lover ( The Sunday Times )

“ Everything in Lessons , whose story concludes within a year and a half of its publication date, gives the impression of having been written in extreme haste . Its prose, for example, is pocked with first-order clichés, second-order clichés, dull metaphors, mixed metaphors, limp similes, oxymorons, pleonasms, catachresis, jejune diction, trivializing double entendres, pomposities, flagrant abuse of self-reflexive questions, and barely-concealed cribbings from more talented stylists like Nabokov … Within the first fifty or so pages, Roland experiences no fewer than three portentous epiphanies, none of which turn out to have any bearing on the subsequent four hundred, as though they were narrative coupons McEwan cut out but forgot to cash in … McEwan’s novel is not so much an epic as it is three novellas in a trench coat … If this all sounds pat, it has less to do with the necessary evil that is plot summary in book reviewing, than to the didacticism with which McEwan imparts these and other praecepta in the novel itself. Yet perhaps worse than the way the book comes pre-interpreted for the reader is the way it comes pre-criticized … The trench coat is History. Draped loosely from the backs of these three narratives are hundreds of named political and cultural events, persons, and phenomena, starting with Dunkirk and ending with the storming of the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, which range from the genuinely consequential to the merely newsworthy to the unmentionably trivial.”

–Ryan Ruby on Ian McEwan’s Lessons ( The New Left Review )

“There is a good, though not excellent, short story hidden somewhere in the four hundred pages of A. M. Homes’s The Unfolding … But on balance, The Unfolding is depressingly shallow, arriving too late and with too little intelligence, humor, wit, or insight to be useful or entertaining … The plot is simple … The structure—dilating and contracting across a narrow band of time—works best in subtly paralleling personal and familial breakdowns with national upheaval, but at its worst, the form makes this novel feel interminable … Homes is dedicated to the idea of these men as so pickled by their own vice and privilege that there’s not an intelligent thought to be found among them. They remain static in their grumbling and their vague schemes, which prevents the irony from deepening or sharpening its critique. What ought to be a central driver of the plot or the evolution of the novel’s themes becomes an inert gimmick … Homes trades away her characters’ convictions and depth for attempted comedic effect. No contrast. No pathos. These men are hollow, which makes the story itself hollow … Homes for some reason describes any surface or object that comes into contact with her characters as though she were writing about the contours of the human soul. Do we need to know what the taxi seats feel like? … I was bored by this book. By its lazy stances, its lax politics, and its rote writing.”

–Brandon Taylor on A. M. Holmes’ The Unfolding ( 4Columns )

“The institutional tone in 21st-century humor is unequipped to deal with anything that matters. In Happy-Go-Lucky , his new collection of essays about the pandemic, aging, and the slow but inevitable death of his father, David Sedaris simultaneously asserts himself as the undisputed past master of this tone and captures its fundamental weakness, applying the style he has developed for the last 30 years to a subject matter for which it is almost eerily unsuited … It is ironic, then, that relatability also turns out to be the absolute bête fucking noire of this collection, cropping up again and again to recast Sedaris not as the antsy everyman we grew up with but rather as some kind of moneyed Aspergers case … For a different author, that would be comedy gold—or at least a bracing opportunity to try something new, to go somewhere more vulnerable and potentially less funny, but also maybe incisive and bittersweet in a way that made the late-life output of funny writers like Twain and Joan Didion so paradoxically invigorating. But Sedaris can’t seem to do it. Either he doesn’t have enough tools in the box or he just refuses to look too closely at any of these understandably difficult subjects, so instead he writes about them in the same tone he used to write about department-store Santas and being bad at French, with disastrously jarring results … Sedaris is like the social director running around the deck of a listing cruise ship, frantically playing for laughs and doing jazz hands while the reader wonders whether he doesn’t know the ship is sinking or just refuses to acknowledge what’s going on … A man with a dozen houses confronts death, the coronavirus pandemic, Black Lives Matter, and broad cultural changes that he cannot fully understand. ‘Ha ha!’ he says. It sounds just like a laugh, just like it always has, except it does not sound true.”

–Dan Brooks on David Sedaris’ Happy-Go-Lucky ( Gawker )

“Even if you’re unfamiliar with this tradition of stories about race transformation, you’ll suspect what’s coming … Tone above all distinguishes Hamid from these precursors. Whereas most of these writers bend race transformation toward satire, offering us topsy-turvy and hysterical tales, Hamid is deeply earnest about his conceit. The novel is that wan 21st-century banality, a ‘meditation,’ and it meditates on how losing whiteness is going to make white people feel. Mostly sad, as it turns out … The sex improves; the prose does not … The novel evinces the worst of Hamid’s style … As in his earlier novels about social mobility and immigration, romance supplies the plot and casts an aura of ‘love’ over the politico-speculative gimmick … This is the novel’s cure for white despair over the loss of whiteness: Keep calm and carry on … What exactly is being born—or rather, borne? Darkness in The Last White Man is an ordeal. Those who were already dark have little presence and no internal life in the novel … If Hamid’s novel were a self-aware satire of this ideology of whiteness and its violent effects, it would be pitch-perfect. But The Last White Man ’s structure affords us no way to know if this is what Hamid intends: It includes no higher judgment, no specific history, no novelistic frame against which to measure the reliability of the narration, no backdrop across which irony can dance … The Last White Man feels like a primer for mourning whiteness, not a critique of it … It’s one thing for a character to be afflicted with blurred vision or the race ‘blindness’ that grants Oona a ‘new kind of sight’; it’s another for the novel to suffer the same confusion of perspective.”

–Namwali Serpell on Mohsin Hamid’s The Last White Man ( The Atlantic )