Tate Papers ISSN 1753-9854

Meyer Schapiro, Abstract Expressionism, and the Paradox of Freedom in Art Historical Description

C. Oliver O’Donnell

This article analyses a talk given by the American art historian Meyer Schapiro in 1956 that was broadcast on BBC radio as a review of an exhibition at Tate Gallery titled Modern Art in the United States . It reveals that Schapiro’s broadcast was funded by the US State Department and argues that this unrecognised historical detail exposes a paradox about the relation between facts and values in art historical description.

In January 1956 the American art historian Meyer Schapiro was sent by the US State Department to London where he gave a talk titled ‘The Younger American Painters of Today’, which was broadcast on BBC radio in conjunction with an exhibition at Tate Gallery. 1 While the substance of the talk was in many ways typical of Schapiro’s writing, the background to it speaks directly to a controversy surrounding the relationship between Schapiro’s scholarship and the wider circumstances of the art world at the time. In his broadcast Schapiro repeatedly described the abstract expressionist paintings in the exhibition as evidencing freedom, a quality that he had associated with abstract painting since at least the 1930s and that played a pivotal part of his defence of the avant-garde, not to mention of his Marxist-inflected research. The exhibition that Schapiro described, however, as well as the educational exchange program in which Schapiro himself was at that very moment participating were deeply embroiled in the anti-communist campaigns of the US cultural establishment during the Cold War, campaigns that deliberately leveraged the ‘freedom’ of American society and culture into anti-Soviet propaganda. This paradoxical situation raises two primary questions. First, why would the US State Department risk sending a known and avowed Marxist to London as a kind of cultural diplomat? Second, why would Schapiro agree to be an official representative of the US government even though he was often critical of the values that that government represented?

In order to investigate these questions it will first be necessary to lay out the historical context for Schapiro’s broadcast, fleshing out the particulars that led Schapiro to London as well as the State Department’s presumed rationale for working with Schapiro as a member of the anti-Stalinist left. Schapiro’s broadcast will be analysed in relation to the specific reception of the Tate exhibition and in relation to the wider intellectual milieu within which Schapiro’s thinking was forged. This broader context is key for understanding Schapiro’s trip because it reveals what political economist Joseph Schumpeter once described as the ‘inconveniently large expanse of common ground’ between Marxism and American liberalism – namely and most obviously, that both the US government as a capitalist world power and Meyer Schapiro as an independent Marxist intellectual were for ‘freedom’. 2 Even though Schapiro would have almost certainly distanced his use of the term from his government’s, such congruence meant that his Marxist-inflected project was especially vulnerable to being separated from the particular means that he advocated for achieving that end. However, insofar as Schapiro’s actual broadcast reflected what he took to be his Marxist principles, the US State Department can also be said to have supported the dissemination of Schapiro’s political intentions. The ruse cuts both ways. What Schapiro actually meant when he described abstract expressionist paintings as ‘free’ and how his description could be interpreted in 1956 in London are two independent and equally important historical questions. It would be a simplification, therefore, to treat Schapiro’s trip to London at the behest of the US State Department as further evidence for what some have seen as his de-Marxification, as much as it would be a simplification to treat the funding source of the trip as inconsequential to the historical significance of Schapiro’s broadcast. 3 Rather, this essay contends that what Schapiro’s trip more accurately exposes is a general paradox at the heart of art historical interpretation: the words that art historians use to describe the visual qualities of works of art are almost by necessity indirect or oblique, a tact that is at once necessary to capture the visual interest of works of art but also precarious in that it makes the intentions behind art historical interpretation easily muted. 4

The historical background to Schapiro’s BBC broadcast

Here is Schapiro’s own account of his trip to London in 1956:

I left New York by plane on January 20 at 5 PM and arrived in London the next day at 1 PM. I gave four lectures: on recent American art, particularly the abstract work, at the Arts Council, the Slade School, the Hampstead Art Society (in the town hall of Hampstead); and on “Leonardo and Freud” at the Warburg Institute of the University of London. I also had numerous discussions with artists, critics and scholars, and saw the work of younger English artists. I found some time, too, to consult several mediaeval manuscripts in the British Museum, relating to my studies in the field. I left London by plane on January 29 at 8 PM and arrived in New York the next day at 9 PM. We were grounded in Shannon over night. 5

This report was composed for and sent to Harold Howland, Chief of the Specialists Division of the International Educational Exchange Service, a subdivision of the International Exchange Service (IES) of the US State Department. It was written in accordance with a contract that Schapiro entered into with the State Department to serve for fifteen days as a Specialist in the International Educational Exchange Program, for which he was paid $256.63. 6 As is clear from Schapiro’s description of the trip, he did more than just give his BBC broadcast while in London, a broadcast that he omits from his description to Howland, presumably because it was the initial reason he was sent to London and because it formed the basis for his other lectures on recent American art while there. Indeed, Schapiro’s earliest extant correspondence about the trip was with Leonie Cohn of the BBC, more than two months before the show at the Tate had even opened. 7 And Schapiro’s wife later described the trip as a ‘rescue mission’ because the travelling show had been ‘panned by reviewers’. 8 Schapiro likely mentioned his additional professional activities to Howland because of the official mission of the IES. The program was described to Schapiro as ‘increasing international understanding and good will toward the United States through the exchange with other countries of students, professors, specialists, and leaders’. 9 Thus Schapiro’s additional interaction with members of the London art world only furthered the ‘international understanding’ that the program was designed to increase. However, the ‘understanding’ that Schapiro helped to create on his trip to London was not as innocuous as the program’s stated mission might seem. William Johnstone, a director of the IES from 1948 to 1952, was unequivocal and less euphemistic when testifying to Congress about the nature of the program: ‘In its simplest form’, Johnstone declared, ‘the job of this program is to implant a set of ideas or facts in the mind of a person. When this is done effectively, it results in action favorable to the achievement of American foreign policy.’ 10 Following Johnstone’s description, Schapiro’s actions in London were deemed part of the expansion of the United States’ ‘soft power’, or perhaps even more hyperbolically, part of a campaign of psychological warfare. 11 While Schapiro no doubt believed his trip to be educational, the distance or discontinuity between Johnstone’s description and the official mission statement of the IES that Schapiro received gives credence to public relations theorist Edward Bernays’s observation that ‘the only difference between “propaganda” and “education”, really, is in the point of view. The advocacy of what we believe in is called education. The advocacy of what we don’t believe in is propaganda’. 12

The likely reasons why Schapiro, despite his political leanings, was selected to go to London are manifold and, in their entirety, admittedly overdetermined. First, there are some circumstantial details that likely played a part. Schapiro had requested funds from the IES two years earlier to fund a research trip to Holland. 13 Even though this request was denied, the program’s officials obviously ascertained that he was interested in and open to such an exchange. Second, according to Schapiro’s wife’s later recollections, the Museum of Modern Art, which organised and loaned the works for the exhibition at Tate, had recommended Schapiro to the State Department, most likely because of his ability and reputation. And third – again according to Schapiro’s wife – Schapiro learned that a State Department official had once heard him speak against the proposal to invite a Nazi official to lecture at Columbia University, which prompted the official to second MoMA’s recommendation. 14

Beyond these immediate circumstances, perhaps a more important factor behind the decision to support Schapiro’s trip – and the International Educational Exchange Program in general – was the research on the formation of public opinion conducted by the eminent sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld. In his book The People’s Choice (1944) Lazarsfeld analysed several years of voting behaviour and noted that people were much more swayed through direct contact with an expert than by hearing that expert’s conclusions through a media outlet. 15 Accordingly, the International Educational Exchange Service facilitated direct contact between experts and various publics by funding the travel of American experts abroad as well as the travel of foreign experts to the United States. In short, Lazarsfeld’s findings provided new empirical justification for exchanges that had previously existed on a more ad hoc basis and his research was ultimately used to support the creation of the more permanent and well-funded program in which Schapiro participated. 16

The actual legislation that created that program was the Informational and Educational Exchange Act, otherwise known as the Smith-Mundt Act of 1950. This led to the creation of the Foreign Leader and Specialist Program, run by the IES, and was an extension of the Truman administration’s ‘campaign for truth’ and policy of containment. 17 US diplomats repeatedly praised the program ‘as a highly successful tool in changing perspectives of key individuals’ and its effectiveness rested largely on the willing involvement of its participants and on the US government not restricting, let alone dictating, what they said. 18 Thus, there is little reason to suspect that Schapiro was coerced in any way in terms of the content of his broadcast. Rather, it is more likely that Schapiro’s earlier description of abstract painting as an embodiment of the universal value of freedom – a description discussed in detail below – made him an especially fitting candidate as the whole premise of the exchange program was not to promote specifically American values but rather to promote American values as universal values. It would therefore seem that, despite his Marxist background, Schapiro’s commitment to the modernist project combined with his status as an expert within the art world made him a perfect candidate.

Of course, Schapiro was also an anti-Stalinist and in this sense was at least in partial agreement with US foreign policy. His anti-Stalinism, however, was much more tempered and independent than that of the majority of his colleagues on the left. As is well known, after the public exposure of Stalin’s purges and crimes in the 1930s, many of Schapiro’s peers moved sharply away from radical leftist politics, some of them even ending up conservatives later in life. 19 One of the most visible outcomes of this shift was the Committee for Cultural Freedom, which was founded by prominent New York intellectuals in 1939, and whose purpose was to promote opposition to totalitarian regimes. Schapiro refused to join the committee not because he did not oppose totalitarianism but because he recognised that the committee was not ‘a “Committee for Cultural Freedom” but an organization for fighting the world Communist movement’. 20 Schapiro, in other words, refused to participate in red-baiting. Even though his politics did shift from a more explicitly Marxist position in the early 1930s – best exemplified in his writing for the New Masses under the pseudonym John Kwait – to a more democratic socialism in the 1950s, throughout his life Schapiro maintained a commitment to Marx’s theories. 21 Like so many independent Marxists, both then as today, Schapiro upheld a separation between Marxism as a set of theoretical propositions and Soviet-style communism, which he saw as a totalitarian corruption of Marx’s ideas.

Considering such commitments, an additional and final motivation for sending Schapiro to London is important to note. In addition to the official legislation that created the IES, President Truman’s National Security Council also passed several executive directives in 1947 and 1948 – named NSC-4, NSC-4A, and NSC-10/2 – which gave the CIA authority to use ‘covert psychological activities’ as well as propaganda to further US interests abroad. 22 To this end the CIA funded cultural programs in Europe, including travelling exhibitions from MoMA, which furthered the message that the US was a free society. 23 Such directives, however, came with the caveat of plausible deniability, a caveat which made working with members of the non-Stalinist left especially appealing. Moreover, as was later revealed by Thomas Braden, one of the CIA officers who was instrumental in such operations, during the height of McCarthyism, sending independent Marxists like Schapiro abroad as cultural ambassadors also functioned as an important countermeasure to the frequent anti-Communist hysteria in Congress. 24 McCarthyism risked undermining the message that the US actually was a free society, thus Schapiro’s trip to London can also be understood as a public display to the international community.

Modern Art in the United States

The actual exhibition that Schapiro reviewed on the BBC was titled Modern Art in the United States: A Selection from the Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York . It had been organised by MoMA director Alfred Barr and curator Dorothy Miller and had opened at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris on 31 March 1955. Between July 1955 and August 1956 the exhibition travelled to Zurich, Barcelona, Frankfurt and London – where it was on view at the Tate Gallery from 5 January to 12 February 1956 – then The Hague, Vienna, Linz and Belgrade. 25 Modern Art in the United States proved to be a major historical event as it did much to introduce abstract expressionism to London, and British critics such as David Sylvester acknowledged that it marked a turning point in their views. 26 This being said, the selection of works for the exhibition was much more diverse than Schapiro’s focus on abstract expressionism would suggest. Realist painters such as Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth as well as figurative sculptors such as Elie Nadelman and Gaston Lachaise were also included. 27

This fact makes Schapiro’s focus on the abstract expressionist canvases in his broadcast all the more noteworthy and further testifies to his commitment to their work and to the values that he saw it embodying. While he was not the only critic with such a focus – Patrick Heron writing in Arts , for instance, as well as Basil Taylor in the Spectator , also devoted considerable attention to the abstract expressionists – the reviews that appeared in the Sunday Times , the Observer and the Manchester Guardian did not. 28 The latter three were either mildly critical of the show or took the artworks as evidence of an unease or lack in American society itself. Moreover, and perhaps more importantly, the reviews by Heron and Taylor that did focus on the abstract expressionists did not emphasise or even mention the quality of freedom that these canvases evidenced for Schapiro.

Unsurprisingly, the examples that Schapiro most emphatically pointed to in his radio address were works by Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning – the latter’s Woman I 1950–2 was used to illustrate the published version of the broadcast (fig.1) – but he also discussed the work of Mark Rothko, Arshile Gorky and Franz Kline, and was sensitive to the diversity of the painting produced by the so-called New York School. Despite this diversity, however, Schapiro repeatedly characterised those paintings as exhibiting ‘a quality of freedom’ – four times in the course of two pages – and as being united by a ‘freedom of composition realised through ambiguous or random forms’. 29 He even went as far as to say that in abstract expressionist painting, ‘[t]he artist’s freedom is located more narrowly and more forcefully than ever before within the self, and opposed to the set, impersonal order of the external world’. 30 Such a description reveals several important presuppositions about Schapiro’s understanding of these paintings.

Fig.1 Meyer Schapiro, ‘The Younger American Painters of Today’, Listener , 26 January 1956, p.146

First, by focusing on the free individual or self in the above statement, Schapiro reveals a central tenet of his understanding of freedom in general, one that is often, although not necessarily, taken to be more indebted to the existentialist philosophies that were prevalent at the time than to Schapiro’s known Marxist commitments. For instance, in The New York School , a 1978 monograph by art historian Irving Sandler, Schapiro’s writing on the abstract expressionists is grouped together with that of Harold Rosenberg and described as reflecting a general period of engagement with existentialist ideas. 31 Such observations are certainly warranted as the very publications for which Schapiro and Rosenberg often wrote engaged heavily with existentialism and Rosenberg himself even originally wrote his seminal essay ‘The American Action Painters’ (1952) for that most famous organ of existentialist thought, Les Temps Modernes . 32 Thus, Schapiro would have been aware and was likely even well versed in existentialist arguments.

Whether Schapiro actually adopted such views himself, however, is not so clear cut. On the one hand, when Schapiro subsequently lectured on the abstract expressionists at Columbia he did acknowledge that there were real historical connections between their work and existentialism, specifically by way of the commonalities between their paintings and those of the surrealist André Masson, whose book The Anatomy of My Universe (1943), which Schapiro himself translated in 1939, betrayed Masson’s reading of Søren Kierkegaard and Martin Heidegger. 33 On the other hand, in the very same lecture, in seeking to understand what he termed the ‘conversions’ of Pollock and de Kooning from their earlier more figurative work to their more abstract compositions of 1947–9, Schapiro stated that ‘[o]ne should turn to William James’s Varieties of Religious Experience ’. 34 It would seem, then, that James’s pragmatist psychology was as much if not more of a touchstone in Schapiro’s thinking about these painters as existentialist philosophy. Marginal notes in Schapiro’s copy of William Barrett’s Irrational Man (1958) – one of the standard introductions to existentialist thought in English at the time – reinforce this point and show that Schapiro thought about existentialism itself through John Dewey’s pragmatist social psychology. Schapiro had studied with Dewey as an undergraduate in the early 1920s and next to a passage in Barrett’s book that positions Heidegger’s existential ontology as a critique of a Cartesian understanding of subjectivity, Schapiro wrote ‘cf. Dewey and Mead’, an interpretation of Heidegger that foreshadows pragmatist interpretations of Heidegger put forward by more recent analytic philosophers. 35

Much in line with this pragmatist tradition, in his 1956 broadcast Schapiro frames his understanding of freedom in relation to the ‘self’ and thereby holds on to a traditional humanistic and holistic understanding of the individual, one where the agency of the artist remains intact. Such an understanding on Schapiro’s part is especially important to note in the case of abstract expressionist paintings for a variety of reasons. First, those paintings are, as Schapiro himself acknowledged, heavily indebted to surrealist sources and are often understood as being in dialogue with the unconscious. As art historian Michael Schreyach has pointed out, this situation has led to an oft unrecognised tension within descriptions of abstract expressionist painting as both automatic and spontaneous, two terms that pull artistic intentionality in opposite directions. Whereas the former fractures the individual agency of the artist by turning him into an automaton – a being of no will of its own – the latter keeps the free will of the artist intact. Indeed, the word spontaneity derives from the Latin sua sponte meaning of one’s own accord. 36 Importantly, in holding to the latter position, Schapiro positions his understanding of the freedom that abstract expressionist paintings evidence as being in basic agreement with the individualism that is stereotypically taken to oppose the collectivism of communist thought, thereby revealing an important commonality between his Marxist scholarship and US Cold War rhetoric.

Of course, Schapiro’s description of abstract expressionist painting in such terms does not necessarily entail a wholesale rejection of collective forces or social circumstances. Art historian David Craven has convincingly framed the intentions behind Schapiro’s general interpretation of abstract expressionism as part of a broader critique of Taylorism and of mid-century workplace management. 37 Under Craven’s interpretation, Schapiro’s description of these painting as ‘free’ becomes a statement about their conditions of production: they were made outside of the dominant economic order; they were not produced explicitly as part of a commodity production line and often (perhaps usually) were left unsold and earned the painter no profit. Here the ‘freedom’ of these paintings reflects the abstract expressionists’ own romantic anti-capitalism, a position that Craven clarifies through de Kooning’s statement that the abstract expressionists had ‘no position in the world – absolutely no position except that we just insist[ed] upon being around’. 38

In relation to the outsider and critical politics of this interpretation, in his BBC broadcast Schapiro characterises the ‘freedom’ of abstract expressionist paintings in an especially superlative way – that is, by noting that in these paintings ‘freedom is located more narrowly and more forcefully than ever before within the self’. 39 Here Schapiro positions the abstract expressionist as a pivotal culmination of wider period developments and suggests that the ‘freedom’ that their paintings express exists at the end of a teleological development. Such an interpretation fits well with the future directed, progressive politics of avant-garde art in general and in its teleological structure parallels the more well-known theories of Clement Greenberg, which Schapiro opposed. 40 In making this point, however, Schapiro was also sure to head off any claims that these paintings were nationalistic. To this end, while he observes that these artists ‘often say that the centre of art has shifted from Paris to New York’ he also notes that:

It is easy to suppose that this new confidence of American artists is merely a reflex of national economic and political strength; but the artists in question are not at all chauvinist or concerned with politics. They would reject any proposal that they use their brushes for a political end. They know that many government officials and Congressmen disapprove of their work and they have experienced, too, the absurd charge that their art is subversive – a survival of the attacks made on modern art in the nineteen-twenties and nineteen-thirties as cultural bolshevism. 41

Schapiro’s plain rejection of the popular charge that abstract expressionist paintings represent a kind of ‘cultural bolshevism’ reveals a fact that Craven’s interpretation downplays: there is a continuity between Schapiro’s anti-Soviet position and official US foreign policy. Schapiro’s denial was much in line with the State Department’s goal of promoting American values as universal values and thus even though Schapiro may have been unaware of the politics of the program in which he was participating, his denial of the politics of these paintings was fittingly and effectively political.

In contrast to Schapiro, one critic did see the abstract expressionist paintings in the Tate exhibition in bold political terms. The British writer John Berger, who reviewed the exhibition in the New Statesman and Nation and titled his review ‘The Battle’, interpreted the gestural marks of abstract expressionist painting as violent and destructive and as representing the anguish of an unlived life and of the oppression of American society. According to Berger:

These works, in their creation and appeal, are a full expression of the suicidal despair of those who are completely trapped within their own dead subjectivity. Erich Fromm, in his most important book, The Fear of Freedom , wrote: ‘Destructiveness is the result of unlived life.’ Behind these works is the same motive of revenge against subjective fears as there is behind the political policy of clinging to the ‘protection’ of the H. Bomb. 42

Needless to say, such an interpretation is quite the reverse of Schapiro’s and calls attention to the differences between certain members of the left. Moreover, by citing a Frankfurt School psychoanalyst like Erich Fromm, Berger highlights that a Marxist reading of the shared gestural marks that are often taken to bind these paintings into a coherent school need not be interpreted as a sign of freedom at all, but rather as a kind of cry for help. Clearly, Berger could not ignore the nationalistic framing of the exhibition – that these works were made in the USA – and the political valence that that point of origin gave to the exhibition as a cultural export in 1956. Fittingly, Berger’s rather feverish review was positioned next to a large sensationalist advertisement about ‘the frightening story of investigation agencies in America’, which was titled ‘Big Brother Will Watch You for £2 or Less’. On this page of the New Statesman and Nation , Cold War politics and their relation to visual art were on full display.

Schapiro’s freedom

Given such an indictment and considering the official circumstances that brought Schapiro to London in 1956, we might well challenge Schapiro’s ostensible blindness to the political background of the exhibition. Schapiro was not, however, as naïve as the contrast between his own review and Berger’s might seem. Indeed, Schapiro had himself even once written that we only notice and describe certain qualities in paintings because those qualities appeal to our own interest:

It may … be asked, to what extent is there knowledge of qualities without an act of valuation? This is important, because the act of valuation is so notoriously private that the attribution of quality associated with it may well be rationalization. This is apparent in works of art, of which the most diverse characters have been predicated with the same emotional instancy. An archaic statue is simply a rigid object to one person, a rigorous form to another. These imply valuations; and the analysis of these two perceptions must take into account the fact that the statement of quality is here posterior to a value judgment … The notion that quality is unique and inherent in the object assumes that there is such a thing as quality apart from the perceiver; and that the latter has the means of grasping it directly. It seems more likely to me that the character of a thing is known to us only in relation to ourselves, and that the assumption of a pervasive quality restricts the nature of an object to those aspects in which we participate because of our own interests. 43

Schapiro was convinced that there was no such thing as a completely disinterested description, that there are no facts without values. Along such lines he confessed that he especially admired John Dewey’s Theory of Valuation (1939), and his wide reading in both pragmatist and Marxist literature no doubt continued to reinforce this claim in his mind. 44 Given this belief, the distance between the freedom that Schapiro noted in abstract expressionist paintings and the lack of freedom that Berger noted in them is not as large as it initially seems. Much like Berger, Schapiro was well aware of the political valence that accompanied his characterisation of abstract expressionist paintings. His point in refusing to identify these paintings with any political ideology in his review, therefore, is more accurately taken to be that the paintings by themselves – that is, independent of any judgement or criticism or even perception of them – are not inherently political; it is rather the ends to which we can put them that are. Considering the divergent political ideologies of the New York School artists themselves – let alone those of the US government and Schapiro – such an assertion is difficult to deny. 45

Schapiro’s own interests in recognising such canvases as evidencing freedom had been well articulated. In his 1937 essay ‘The Nature of Abstract Art’ Schapiro made similar observations about the work of Kazimir Malevich and Wassily Kandinsky – that their abstract paintings were ‘free’ in the sense that they were free of subject matter, of the task of representing the external world. In making such an observation in 1937, however, Schapiro was more forceful in his Marxist political bent and that is at least partially because those observations appeared in the short-lived Marxist Quarterly . Therein, Schapiro observed that both Malevich and Kandinsky ‘justify themselves by ethical and metaphysical standpoints, or in defense of their art attack the preceding style as the counterpart of a detested social or moral position. Not the processes of imitating nature were exhausted but the valuation of nature itself had changed’. 46 Here Schapiro points out in no uncertain terms that there was indeed a moral, social or political dimension to abstraction and the freedom that came with it. That political dimension stemmed from a ‘detest’ for the current reality and a desire to change it.

While the historical distance between that essay and Schapiro’s 1956 broadcast should not be ignored, neither should it be exaggerated. A year after his BBC broadcast, in his address to the American Federation of the Arts titled ‘The Liberating Quality of the Avant-Garde’, Schapiro did much to define his understanding of freedom by repeatedly contrasting recent abstract painting with the ‘mechanical products’ and ‘industrial production’ of the modern world. 47 In so doing, Schapiro reveals that even well into the 1950s his understanding of freedom reflected more of Marx’s definition of the term than that of classical liberalism. As is well known, whereas classical liberalism defines freedom negatively as independence from the coercive will of another, Marx broadened the scope of freedom to include the positive ability to act and achieve certain goals and desires. 48 For Marx, the means of production and capital in particular were constraining forces on an individual’s ability to act in certain ways and because such forces were man-made economic conditions they could and should also be understood as constraints on individual liberty. By positioning the ‘freedom’ of recent abstract paintings against the restraints imposed on individual personality and expression that accompanied modern, industrialised labour conditions, Schapiro can be understood as implicitly evoking Marx’s definition of the term.

By the time of Schapiro’s trip to London, however, other very different notions of freedom were being expounded through US government channels. In November 1955 the Department of Defense published and distributed a booklet titled Militant Liberty , which encouraged the development of a rather crude political stance in the public to ward off the threat of communism. 49 Hollywood films were proposed as the main means of accomplishing this goal and directors such as John Ford and Merian Cooper, as well as actors such as John Wayne and Ward Bond, were recruited and took up the program’s ideals. While the messages conveyed by these films were stereotypical and rather bland, they were also effective: America is a prosperous society, competition is healthy, the ‘Free World’ is superior to Moscow. 50 In these films freedom became a slogan for resisting communism and preserving the capitalist status quo rather than as a plea for change.

The contradiction between this popular political background and Schapiro’s intentions speaks well to a more general tension at the heart of art historical interpretation: the words that are used to describe works of art often take on meaning in relation to the values that are read into them. This is partly because it is only in oblique and demonstrative writing – rather than in purely descriptive writing – that the visual interest of works of art emerges. As art historian Michael Baxandall pointed out, it is an obvious but nevertheless difficult fact that the purpose of art writing is not merely to come up with a list of objective visual qualities that artworks have but to point or direct viewers’ attention to qualities that are interesting . To clarify his observation Baxandall divided the vocabulary of art criticism into three categories: comparative and metaphorical words that are used to identify visual interest; words that describe the action or agent that created the work; and words that characterise the work’s effect on the beholder. 51 If we apply this typology to Schapiro’s broadcast it is clear that the ‘freedom’ that he describes in abstract expressionist painting shifts back and forth between these three word types. Complicating matters even further, because the ‘freedom’ that Schapiro evokes is demonstrative rather than purely descriptive – i.e. is intended to be refined by the reader in their experience of the paintings – the choice as to which of the three types of freedom Schapiro’s description conveys is partially contingent on the reader and on the values that they associate with that particular quality. Just as a reader today sympathetic to Schapiro’s politics can recuperate Schapiro’s socialist intentions from his description, so too can we imagine a sympathetic listener in London in 1956 – someone like Patrick Heron for example – doing the same. And just as a reader critical of Schapiro’s politics can understand Schapiro’s description as evidence of his de-Marxification, so too can we imagine a listener in 1956 with more orthodox Marxists leanings – someone like John Berger – understanding Schapiro’s description as little more than a furthering of anti-Soviet propaganda.

Fully aware of these ambiguities, Schapiro’s commitment to describing abstract paintings as evidencing freedom remained steadfast and nuanced. In a later lecture course on abstract art, Schapiro was asked about the role of chance in Jackson Pollock’s work, the empirical quality that in 1937 he had already pointed to as corresponding ‘to a feeling of freedom’. 52 After a long, rich answer which ranged from probability theory to the very possibility of randomness in the universe to our perception of chance in certain forms, Schapiro ended by noting that he had once read a sad book by the self-taught French philosopher Pierre Camille Revel which claimed that

good and evil are like heads and tails – they are two opposite values of our actions. Now, [Revel] said, according to the law of large numbers in statistics, the more often you throw the coin, the more the results approach equality. Well, the more actions you perform, the more good and evil approach equality. Therefore there is no need to make choices, or to have any kind of morality or ethics, because in the long run – that famous word – the amount of evil in the world and the amount of good will be just about equal. His notion of chance was an unanalyzed one; he assumed that we could distinguish good and evil as distinctly as we can distinguish heads and tails, and that the conditions are uniform in action, so that the two will eventually equalize. 53

By ending his discussion of chance in Jackson Pollock’s painting with this anecdote, Schapiro again subtly points out the intractable relationship between facts and values in art historical description. And by extrapolating his point a bit further, we can almost hear him say that while randomness and chance are clearly key qualities of Jackson Pollock’s paintings, merely observing the importance of those qualities in his painting does not excuse us from the need to make a value judgment about those qualities. Schapiro’s point is, thus, quite simple: as viewers of art we cannot and should not excuse ourselves from the act of valuation.

Such a position, I believe, helps make some sense of why Schapiro agreed to go to London, why he had applied for money from the IES already in 1953, and why he would request to participate in the program again later in 1956, a request that was denied. 54 Schapiro was a firm believer in the importance and inescapability of value judgments in his scholarship and by going to London he can well be said to have upheld his self-imposed responsibility to identify the values – the morality, we might say – that he had observed in abstract paintings as early as the 1930s. Even though Schapiro’s silence in his BBC broadcast about his Marxist bent certainly reflects the gradual tempering of his politics, to read that silence as a wholesale abdication of his previously and subsequently stated political beliefs goes too far. Moreover, for us to read Schapiro as if he were merely a kind of unwitting Cold Warrior because his writing, voice and authority were co-opted or put to use by the United States’ propaganda campaign against the Soviet Union is only a partial truth, one that reflects our own biased understanding of the word freedom based on its current use in international politics and one that constrains the meaning of Schapiro’s words to an understanding of them that Schapiro himself no doubt opposed. Considered more fully, what Schapiro’s trip to London reveals is that the value of freedom that he associated with the quality of randomness in abstract expressionist paintings was separable from the morality that led him to identify that quality in those paintings in the first place. The lesson of Schapiro’s trip to London, therefore, is a lesson that Schapiro himself knew well. As he wrote in 1937, ‘[t]he fact that a work of art has a politically radical content therefore does not assure its revolutionary value’. 55 By themselves abstract expressionist paintings evidence neither freedom nor repression, represent neither capitalism nor Marxism, but rather serve as a powerful reminder that there is no such thing as free art historical description.

- Publisher Home

- About the Journal

- Editorial Team

- Article Processing Fee

- Privacy Statement

- Crossmark Policy

- Copyright Statement

- GDPR Policy

- Open Access Policy

- Publication Ethics Statement

- Author Guidelines

- Announcements

A Causal Analysis of the Promotion of Abstract Expressionism: On the Foreign Policy of the United States

- Jingjing Shi

Jingjing Shi

Search for the other articles from the author in:

Abstract Views 186

Downloads 141

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.sidebar##

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.main##

It is well known that during the Cold War the United States focused on the promotion of Abstract Expressionism and regarded it as a powerful weapon for the improvement of its cultural status and capacity to compete with the USSR. An analysis of this phenomenon – its causes, characteristics, and effects – would be incomplete without studying the foreign policy efforts of that time and the special traits of Abstract Expressionism’s artistic influence. It can be concluded that the rise of Abstract Expressionism after the Second World War was aligned with the goals of American policy instructions and outward cultural promotion during the Cold War. In turn, the powerful implementation of foreign policy actively enhanced the international influence of American Abstract Expressionism during that historical period. This paper undertakes an analysis of the causes for Abstract Expressionism’s successful promotion, through the study of abundant first-hand literature and documents, historical analysis as well as complex analysis. The use of case studies is also applied to further explain the phenomenon from the perspective of American foreign policy in the Cold War.

Abstract Expressionism, an introduction

Mark Rothko, No. 16 (Red, Brown, and Black) , 1958, oil on canvas, 8′ 10 5/8″ x 9′ 9 1/4″ (The Museum of Modern Art) (photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The group of artists known as Abstract Expressionists emerged in the United States in the years following World War II. As the term suggests, their work was characterized by non-objective imagery that appeared emotionally charged with personal meaning. The artists, however, rejected these implications of the name.

What’s in a name?

They insisted their subjects were not “abstract,” but rather primal images, deeply rooted in society’s collective unconscious. Their paintings did not express mere emotion. They communicated universal truths about the human condition. For these reasons, another term—the New York School—offers a more accurate descriptor of the group, for although some eventually relocated, their distinctive aesthetic first found form in New York City.

The rise of the New York School reflects the broader cultural context of the mid-Twentieth Century, especially the shift away from Europe as the center of intellectual and artistic innovation in the West. Much of Abstraction Expressionism’s significance stems from its status as the first American visual art movement to gain international acclaim.

Art for a world in shambles

Barnet Newman, an artist associated with the movement, wrote:

“We felt the moral crisis of a world in shambles, a world destroyed by a great depression and a fierce World War, and it was impossible at that time to paint the kind of paintings that we were doing—flowers, reclining nudes, and people playing the cello.”¹

Although distinguished by individual styles, the Abstract Expressionists shared common artistic and intellectual interests. While not expressly political, most of the artists held strong convictions based on Marxist ideas of social and economic equality. Many had benefited directly from employment in the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. There, they found influences in Regionalist styles of American artists such as Thomas Hart Benton, as well as the Socialist Realism of Mexican muralists including Diego Rivera and José Orozco.

The growth of Fascism in Europe had brought a wave of immigrant artists to the United States in the 1930s, which gave Americans greater access to ideas and practices of European Modernism. They sought training at the school founded by German painter Hans Hoffmann, and from Josef Albers, who left the Bauhaus in 1933 to teach at the experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina, and later at Yale University. This European presence made clear the formal innovations of Cubism, as well as the psychological undertones and automatic painting techniques of Surrealism.

Whereas Surrealism had found inspiration in the theories of Sigmund Freud, the Abstract Expressionists looked more to the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung and his explanations of primitive archetypes that were a part of our collective human experience. They also gravitated toward Existentialist philosophy, made popular by European intellectuals such as Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Given the atrocities of World War II, Existentialism appealed to the Abstract Expressionists. Sartre’s position that an individual’s actions might give life meaning suggested the importance of the artist’s creative process. Through the artist’s physical struggle with his materials, a painting itself might ultimately come to serve as a lasting mark of one’s existence. Each of the artists involved with Abstract Expressionism eventually developed an individual style that can be easily recognized as evidence of his artistic practice and contribution.

What does it look like?

Although Abstract Expressionism informed the sculpture of David Smith and Aaron Siskind’s photography, the movement is most closely linked to painting. Most Abstract Expressionist paintings are large scale, include non-objective imagery, lack a clear focal point, and show visible signs of the artist’s working process, but these characteristics are not consistent in every example.

In the case of Willem de Kooning’s Woman I, the visible brush strokes and thickly applied pigment are typical of the “Action Painting” style of Abstract Expressionism also associated with Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline. Looking at Woman I, we can easily imagine de Kooning at work, using strong slashing gestures, adding gobs of paint to create heavily built-up surfaces that could be physically worked and reworked with his brush and palette knife. De Kooning’s central image is clearly recognizable, reflecting the tradition of the female nude throughout art history. Born in the Netherlands, de Kooning was trained in the European academic tradition unlike his American colleagues. Although he produced many non-objective works throughout his career, his early background might be one factor in his frequent return to the figure.

In contrast to the dynamic appearance of de Kooning’s art, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman exemplify what is sometimes called the “Color Imagist” or “Color Field” style of Abstract Expressionism. These artists produced large scale, non-objective imagery as well, but their work lacks the energetic intensity and gestural quality of Action Painting. Rothko’s mature paintings exemplify this tendency. His subtly rendered rectangles appear to float against their background. For artists like Rothko, these images were meant to encourage meditation and personal reflection.

Adolph Gottlieb, writing with Rothko and Newman in 1943, explained, “We favor the simple expression of the complex thought.”²

Barnett Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis illustrates this lofty goal. In this painting, Newman relied on “zips,” vertical lines that punctuate the painted field of the background to serve a dual function. While they visually highlight the expanse of contrasting color around them, they metaphorically reflect our own presence as individuals within our potentially overwhelming surroundings. Newman’s painting evokes the 18th century notion of the Sublime, a philosophical concept related to spiritual understanding of humanity’s place among the greater forces of the universe.

Abstract Expressionism’s legacy

Throughout the 1950s, Abstract Expressionism became the dominant influence on artists both in the United States and abroad. The U.S. government embraced its distinctive style as a reflection of American democracy, individualism, and cultural achievement, and actively promoted international exhibitions of Abstract Expressionism as a form of political propaganda during the years of the Cold War. However, many artists found it difficult to replicate the emotional authenticity implicit in the stylistic innovations of de Kooning and Pollock. Their work appeared studied and lacked the same vitality of the first generation pioneers. Others saw the metaphysical undertones of Abstract Expressionism at odds with a society increasingly concerned with a consumer mentality, fueled by economic success and proliferation of the mass media. Such reactions would inevitably lead to the emergence of Pop, Minimalism, and the rise of a range of new artistic developments in the mid 20th century.

1. Barnett Newman, “Response to the Reverend Thomas F. Mathews,” in Revelation, Place and Symbol (Journal of the First Congress on Religion, Architecture and the Visual Arts) , 1969.

2. Letter from Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb to Edward Alden Jewell Art Editor, New York Times , June 7, 1943.

Additional resources:

Abstract Expressionism on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”One31,”]

More Smarthistory images…

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Pricing Revolution: From Abstract Expressionism to Pop Art

Abstract Expressionism famously shifted the center of the advanced art world from Paris to New York. The triumph of Abstract Expressionism, and its subsequent abrupt decline in the face of Pop Art, are familiar tales in the literature of art history. Econometric analysis of evidence from auction markets now provides a basis for dating precisely the greatest innovations of the leading Abstract Expressionists, and of the leaders of the cohort that succeeded them. These data demonstrate how fundamentally each of these revolutions affected the nature of painting, by showing how greatly the creative life cycles of the experimental old masters of Abstract Expressionism differed from those of the conceptual young geniuses who followed them. The innovations of the Abstract Expressionists were based on extended experimentation, as they searched for novel visual images; Pop artists rejected this open-ended search for personal forms, and instead treated painting as the impersonal transcription of preconceived ideas. Accumulation of experience was critical for the Abstract Expressionists, who produced their most valuable art late in their lives, whereas lack of experience allowed the next generation the freedom to imagine radically new approaches, and they produced their most valuable art early in their careers.

More Research From These Scholars

Experimental entrepreneurs, revising the canon: how andy warhol became the most important american modern artist, hidden genius.

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion? You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Abstract Expressionism: Works on Paper. Selections from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Abstract Expressionist works on paper from the permanent collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art are presented in this volume, which documents the wealth of the Museum's holdings in that area. Many of them are published here for the first time, and several are recent additions to the collection. All are illustrated in full-page color reproductions that show the nuances of each work in great detail.

The Abstract Expressionists are best known for their paintings and sculptures, and virtually all of the many publications about these artists concentrate on those large-scale works. This unique catalogue deals exclusively with their smaller, more intimate works on paper, providing many new insights about the routes that led to the Abstract Expressionists' innovative artistic accomplishments. The nineteen artists included are William Baziotes, James Brooks, Elaine de Kooning, Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Adolph Gottlieb, Philip Guston, Gerome Kamrowski, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Richard Pousette-Dart, Theodore Roszak, Mark Rothko, Anne Ryan, David Smith, Theodoros Stamos, and Mark Tobey. Each of them is discussed in a separate essay, which encompasses information about the artist's background and development, commentary about the importance of drawing in his or her oeuvre, and an analysis of each work in the selection. Also included in the essays is technical information about a number of the individual works that enhances understanding of the variety and originality of these artists' media and techniques.

The text is by Lisa Mintz Messinger, Assistant Curator, Department of Twentieth Century Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Met Art in Publication

You May Also Like

Abstract Expressionism and Other Modern Works: The Muriel Kallis Steinberg Newman Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Anselm Kiefer: Works on Paper in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, Fifty Years

"The Abstract Expressionists"

Contemporary Ceramics: Selections from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Related content.

- Essay Modern Materials: Plastics

- Essay Abstract Expressionism

———. 1992. Abstract Expressionism: Works on Paper ; Selections from The Metropolitan Museum of Art ; [the Exhibition Held at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, from January 26, 1993, through April 4, 1993, and at The Metropolitan Museum of Art from May 4, 1993 through September 12, 1993] . Edited by Lisa Mintz Messinger. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art [u.a.].

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 14 May 2024

2023 summer warmth unparalleled over the past 2,000 years

- Jan Esper ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3919-014X 1 , 2 ,

- Max Torbenson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2720-2238 1 &

- Ulf Büntgen 2 , 3 , 4

Nature ( 2024 ) Cite this article

912 Accesses

2038 Altmetric

Metrics details

We are providing an unedited version of this manuscript to give early access to its findings. Before final publication, the manuscript will undergo further editing. Please note there may be errors present which affect the content, and all legal disclaimers apply.

- Climate change

- Palaeoclimate

Including an exceptionally warm Northern Hemisphere (NH) summer 1 ,2 , 2023 has been reported as the hottest year on record 3-5 . Contextualizing recent anthropogenic warming against past natural variability is nontrivial, however, because the sparse 19 th century meteorological records tend to be too warm 6 . Here, we combine observed and reconstructed June-August (JJA) surface air temperatures to show that 2023 was the warmest NH extra-tropical summer over the past 2000 years exceeding the 95% confidence range of natural climate variability by more than half a degree Celsius. Comparison of the 2023 JJA warming against the coldest reconstructed summer in 536 CE reveals a maximum range of pre-Anthropocene-to-2023 temperatures of 3.93°C. Although 2023 is consistent with a greenhouse gases-induced warming trend 7 that is amplified by an unfolding El Niño event 8 , this extreme emphasizes the urgency to implement international agreements for carbon emission reduction.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Large-scale emergence of regional changes in year-to-year temperature variability by the end of the 21st century

Cooler Arctic surface temperatures simulated by climate models are closer to satellite-based data than the ERA5 reanalysis

Warming events projected to become more frequent and last longer across Antarctica

Author information, authors and affiliations.

Department of Geography, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany

Jan Esper & Max Torbenson

Global Change Research Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Brno, Czech Republic

Jan Esper & Ulf Büntgen

Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Ulf Büntgen

Department of Geography, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jan Esper .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Esper, J., Torbenson, M. & Büntgen, U. 2023 summer warmth unparalleled over the past 2,000 years. Nature (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07512-y

Download citation

Received : 16 January 2024

Accepted : 02 May 2024

Published : 14 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07512-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Abstract expressionism

Related Papers

Catherine Timotei

Temara Prem

Film studies have been conventionally paired with literature or studies of the dramatic arts. Film, however, is an incredibly visual medium. The filmmaker encodes their frame with visual content, as does the painter with their canvas. Since antiquity visual rhetoricians have discussed the significance of images and art, and there have been many contributions to the existential debate of where the medium of film situates itself in the arts. This research aims to contribute to the overarching question of how, and to what extent fine art has influenced the development of film, focussing specifically on the pioneer of the Baroque movement, the infamous painter Caravaggio, and his Baroque aesthetic associated with German Expressionist films of the Weimar era. Therefore, a literary review of aesthetics and art theory is established, as well as the trajectory and style of the artist Caravaggio. This research also defines the components of cinematic mise-en-scène, of which is analysed in a case study. The case study itself presents a textual analysis of the German Expressionist films Nosferatu (1922) and Metropolis (1927) utilizing the framework of Panofsky’s iconographic analysis, thereby not only treating the film as a text to be analysed, but also as an art image to be decoded. This particular mode of enquiry allows this research to thoroughly answer the research question of ‘how does the Caravaggesque Baroque fine art aesthetics, applied to the cinematic mise-en-scène, contribute to the developments of the visual style of the post-war Expressionist cinema?’

Sayna Sabbaghpour

An Introduction to Abstract Art

Science in Context

Robin Curtis

Despite the fact that “empathy” is often simply used as a translation of Einfühlung, the two terms have distinct meanings and distinct disciplinary affiliations. This text considers the manner in which the moving image (whether within a film, video, or art installation) invites spatial forms of engagement akin to those described both by historical accounts of Einfühlung, a form of engagement that pertains not only to the activities of humans represented within images, but also to the aesthetic qualities of images in a more abstract sense and to the forms to be found there.

Kevin G Barnhurst

Formal theories reveal a visual dimension underlying better-known picture theories. Patterns of elements such as lines, shapes, and spaces, along with their properties, generate emotional responses and follow visual styles in society. The elements combine into systems that create perspectives on the world. Formal awareness may generate an understanding of visual philosophies and their inherent values and consequences. Picture theories start from the tension between scientific invention and artistic expression. From linguistics and philosophy, semiotics provides terms for analyzing pictures as signs that mediate among mind, eye, and reality, operate within codes, and reproduce mythology. From film and literary aesthetics, narrative theory offers analytical structures that reproduce realism through supposed objectivity, rationality, and autonomy in dialogue with conventions and genres. Critical, cultural, and poststructural theories assert the inauthenticity of pictures, social construction of representation, and instability of meaning. Visual aesthetics, analysis, criticism, and ethics have entered flux in digital times.

Sjoerd van Tuinen

Megan Walch

Dijo Mathews

RELATED PAPERS

Amanda Katherine Rath

Ariane Fabreti

Gregory Galligan, PhD

Ulrich de Balbian

Eugenio Carmona

Beyond Mimesis and Convention

Manuel García-Carpintero

Russell Re Manning

Meliza Viquez Salazar

The Living Line: Modern Art and the Economy of Energy

Robin Veder

https://courtauld.ac.uk/research/courtauld-books-online/a-reader-in-east-central-european-modernism-1918-1956

Klara Kemp-Welch

Eziwho Azunwo

Journal of Art Historiography

Kathryn Simpson

Millennium: Journal of International Studies

Roland Bleiker

Los Modernos. México: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Museo Nacional de Arte, Ediciones El Viso

Paulina Bravo Villarreal

The Occult in Modernist Art, Literature, and Cinema. Eds. Tessel M. Baduin & Henrik Johnsson. [Palgrave Studies in New Religions and Alternative Spiritualities]. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 49-66.

Gisli Magnusson

Medien & Zeit

Art in transfer in the Era of Pop. Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies, edited by Annika Öhrner and Charlotte Bydler. Stockholm: Södertörn University, 2016.

Catherine Dossin

Anna Polishchuk

Rolando M Gripaldo

Viorica Patea

andrew johnson

Joseph Nechvatal

Sabrina Fredes

Proceedings of the Estonian Academy of Arts

Virve Sarapik

Hélène Trespeuch

aris sarafianos

Neil Davidson

wilson hurst

Paul Helliwell

Neb Kujundzic

Petra Šobáňová , Tereza Hrubá

Maria Chester

thorsten botz-bornstein

Richard Shiff

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2024

Sexual and reproductive health implementation research in humanitarian contexts: a scoping review

- Alexandra Norton 1 &

- Hannah Tappis 2

Reproductive Health volume 21 , Article number: 64 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

85 Accesses

Metrics details

Meeting the health needs of crisis-affected populations is a growing challenge, with 339 million people globally in need of humanitarian assistance in 2023. Given one in four people living in humanitarian contexts are women and girls of reproductive age, sexual and reproductive health care is considered as essential health service and minimum standard for humanitarian response. Despite growing calls for increased investment in implementation research in humanitarian settings, guidance on appropriate methods and analytical frameworks is limited.

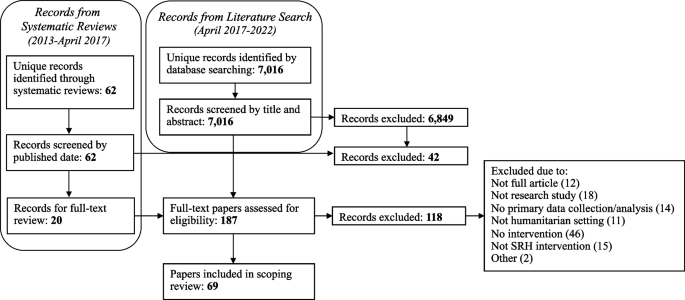

A scoping review was conducted to examine the extent to which implementation research frameworks have been used to evaluate sexual and reproductive health interventions in humanitarian settings. Peer-reviewed papers published from 2013 to 2022 were identified through relevant systematic reviews and a literature search of Pubmed, Embase, PsycInfo, CINAHL and Global Health databases. Papers that presented primary quantitative or qualitative data pertaining to a sexual and reproductive health intervention in a humanitarian setting were included.

Seven thousand thirty-six unique records were screened for inclusion, and 69 papers met inclusion criteria. Of these, six papers explicitly described the use of an implementation research framework, three citing use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Three additional papers referenced other types of frameworks used in their evaluation. Factors cited across all included studies as helping the intervention in their presence or hindering in their absence were synthesized into the following Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research domains: Characteristics of Systems, Outer Setting, Inner Setting, Characteristics of Individuals, Intervention Characteristics, and Process.

This review found a wide range of methodologies and only six of 69 studies using an implementation research framework, highlighting an opportunity for standardization to better inform the evidence for and delivery of sexual and reproductive health interventions in humanitarian settings. Increased use of implementation research frameworks such as a modified Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research could work toward both expanding the evidence base and increasing standardization.

Plain English summary

Three hundred thirty-nine million people globally were in need of humanitarian assistance in 2023, and meeting the health needs of crisis-affected populations is a growing challenge. One in four people living in humanitarian contexts are women and girls of reproductive age, and provision of sexual and reproductive health care is considered to be essential within a humanitarian response. Implementation research can help to better understand how real-world contexts affect health improvement efforts. Despite growing calls for increased investment in implementation research in humanitarian settings, guidance on how best to do so is limited. This scoping review was conducted to examine the extent to which implementation research frameworks have been used to evaluate sexual and reproductive health interventions in humanitarian settings. Of 69 papers that met inclusion criteria for the review, six of them explicitly described the use of an implementation research framework. Three used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, a theory-based framework that can guide implementation research. Three additional papers referenced other types of frameworks used in their evaluation. This review summarizes how factors relevant to different aspects of implementation within the included papers could have been organized using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. The findings from this review highlight an opportunity for standardization to better inform the evidence for and delivery of sexual and reproductive health interventions in humanitarian settings. Increased use of implementation research frameworks such as a modified Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research could work toward both expanding the evidence base and increasing standardization.

Peer Review reports

Over the past few decades, the field of public health implementation research (IR) has grown as a means by which the real-world conditions affecting health improvement efforts can be better understood. Peters et al. put forward the following broad definition of IR for health: “IR is the scientific inquiry into questions concerning implementation – the act of carrying an intention into effect, which in health research can be policies, programmes, or individual practices (collectively called interventions)” [ 1 ].

As IR emphasizes real-world circumstances, the context within which a health intervention is delivered is a core consideration. However, much IR implemented to date has focused on higher-resource settings, with many proposed frameworks developed with particular utility for a higher-income setting [ 2 ]. In recognition of IR’s potential to increase evidence across a range of settings, there have been numerous reviews of the use of IR in lower-resource settings as well as calls for broader use [ 3 , 4 ]. There have also been more focused efforts to modify various approaches and frameworks to strengthen the relevance of IR to low- and middle-income country settings (LMICs), such as the work by Means et al. to adapt a specific IR framework for increased utility in LMICs [ 2 ].

Within LMIC settings, the centrality of context to a health intervention’s impact is of particular relevance in humanitarian settings, which present a set of distinct implementation challenges [ 5 ]. Humanitarian responses to crisis situations operate with limited resources, under potential security concerns, and often under pressure to relieve acute suffering and need [ 6 ]. Given these factors, successful implementation of a particular health intervention may require different qualities than those that optimize intervention impact under more stable circumstances [ 7 ]. Despite increasing recognition of the need for expanded evidence of health interventions in humanitarian settings, the evidence base remains limited [ 8 ]. Furthermore, despite its potential utility, there is not standardized guidance on IR in humanitarian settings, nor are there widely endorsed recommendations for the frameworks best suited to analyze implementation in these settings.

Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is a core aspect of the health sector response in humanitarian settings [ 9 ]. Yet, progress in addressing SRH needs has lagged far behind other services because of challenges related to culture and ideology, financing constraints, lack of data and competing priorities [ 10 ]. The Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for SRH in Crisis Situations is the international standard for the minimum set of SRH services that should be implemented in all crisis situations [ 11 ]. However, as in other areas of health, there is need for expanded evidence for planning and implementation of SRH interventions in humanitarian settings. Recent systematic reviews of SRH in humanitarian settings have focused on the effectiveness of interventions and service delivery strategies, as well as factors affecting utilization, but have not detailed whether IR frameworks were used [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. There have also been recent reviews examining IR frameworks used in various settings and research areas, but none have explicitly focused on humanitarian settings [ 2 , 16 ].

Given the need for an expanded evidence base for SRH interventions in humanitarian settings and the potential for IR to be used to expand the available evidence, a scoping review was undertaken. This scoping review sought to identify IR approaches that have been used in the last ten years to evaluate SRH interventions in humanitarian settings.

This review also sought to shed light on whether there is a need for a common framework to guide research design, analysis, and reporting for SRH interventions in humanitarian settings and if so, if there are any established frameworks already in use that would be fit-for-purpose or could be tailored to meet this need.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews was utilized to guide the elements of this review [ 17 ]. The review protocol was retrospectively registered with the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/b5qtz ).

Search strategy

A two-fold search strategy was undertaken for this review, which covered the last 10 years (2013–2022). First, recent systematic reviews pertaining to research or evaluation of SRH interventions in humanitarian settings were identified through keyword searches on PubMed and Google Scholar. Four relevant systematic reviews were identified [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ] Table 1 .

Second, a literature search mirroring these reviews was conducted to identify relevant papers published since the completion of searches for the most recent review (April 2017). Additional file 1 includes the search terms that were used in the literature search [see Additional file 1 ].

The literature search was conducted for papers published from April 2017 to December 2022 in the databases that were searched in one or more of the systematic reviews: PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, CINAHL and Global Health. Searches were completed in January 2023 Table 2 .

Two reviewers screened each identified study for alignment with inclusion criteria. Studies in the four systematic reviews identified were considered potentially eligible if published during the last 10 years. These papers then underwent full-text review to confirm satisfaction of all inclusion criteria, as inclusion criteria were similar but not fully aligned across the four reviews.

Literature search results were exported into a citation manager (Covidence), duplicates were removed, and a step-wise screening process for inclusion was applied. First, all papers underwent title and abstract screening. The remaining papers after abstract screening then underwent full-text review to confirm satisfaction of all inclusion criteria. Title and abstract screening as well as full-text review was conducted independently by both authors; disagreements after full-text review were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and synthesis

The following content areas were summarized in Microsoft Excel for each paper that met inclusion criteria: publication details including author, year, country, setting [rural, urban, camp, settlement], population [refugees, internally displaced persons, general crisis-affected], crisis type [armed conflict, natural disaster], crisis stage [acute, chronic], study design, research methods, SRH intervention, and intervention target population [specific beneficiaries of the intervention within the broader population]; the use of an IR framework; details regarding the IR framework, how it was used, and any rationale given for the framework used; factors cited as impacting SRH interventions, either positively or negatively; and other key findings deemed relevant to this review.

As the focus of this review was on the approach taken for SRH intervention research and evaluation, the quality of the studies themselves was not assessed.

Twenty papers underwent full-text review due to their inclusion in one or more of the four systematic reviews and meeting publication date inclusion criteria. The literature search identified 7,016 unique papers. After full-text screening, 69 met all inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Figure 1 illustrates the search strategy and screening process.

Flow chart of paper identification

Papers published in each of the 10 years of the review timeframe (2013–2022) were included. 29% of the papers originated from the first five years of the time frame considered for this review, with the remaining 71% papers coming from the second half. Characteristics of included publications, including geographic location, type of humanitarian crisis, and type of SRH intervention, are presented in Table 3 .

A wide range of study designs and methods were used across the papers, with both qualitative and quantitative studies well represented. Twenty-six papers were quantitative evaluations [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ], 17 were qualitative [ 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ], and 26 used mixed methods [ 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 ]. Within the quantitative evaluations, 15 were observational, while five were quasi-experimental, five were randomized controlled trials, and one was an economic evaluation. Study designs as classified by the authors of this review are summarized in Table 4 .

Six papers (9%) explicitly cited use of an IR framework. Three of these papers utilized the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [ 51 , 65 , 70 ]. The CFIR is a commonly used determinant framework that—in its originally proposed form in 2009—is comprised of five domains, each of which has constructs to further categorize factors that impact implementation. The CFIR domains were identified as core content areas influencing the effectiveness of implementation, and the constructs within each domain are intended to provide a range of options for researchers to select from to “guide diagnostic assessments of implementation context, evaluate implementation progress, and help explain findings.” [ 87 ] To allow for consistent terminology throughout this review, the original 2009 CFIR domains and constructs are used.