How to Handle Co-authorship When Not Everyone’s Research Contributions Make It into the Paper

- Original Research/Scholarship

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2021

- Volume 27 , article number 27 , ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Gert Helgesson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0075-0165 1 ,

- Zubin Master ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3462-4546 2 &

- William Bülow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5244-6878 3

10k Accesses

6 Citations

52 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

While much of the scholarly work on ethics relating to academic authorship examines the fair distribution of authorship credit, none has yet examined situations where a researcher contributes significantly to the project, but whose contributions do not make it into the final manuscript. Such a scenario is commonplace in collaborative research settings in many disciplines and may occur for a number of reasons, such as excluding research in order to provide the paper with a clearer focus, tell a particular story, or exclude negative results that do not fit the hypothesis. Our concern in this paper is less about the reasons for including or excluding data from a paper and more about distributing credit in this type of scenario. In particular, we argue that the notion ‘substantial contribution’, which is part of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) authorship criteria, is ambiguous and that we should ask whether it concerns what ends up in the paper or what is a substantial contribution to the research process leading up to the paper. We then argue, based on the principles of fairness, due credit, and ensuring transparency and accountability in research, that the latter interpretation is more plausible from a research ethics point of view. We conclude that the ICMJE and other organizations interested in authorship and publication ethics should consider including guidance on authorship attribution in situations where researchers contribute significantly to the research process leading up to a specific paper, but where their contribution is finally omitted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Scientific authorship and intellectual involvement in the research: Should they coincide?

Gert Helgesson

Biomedical Authorship: Common Misconducts and Possible Scenarios for Disputes

Behrooz Astaneh, Lisa Schwartz & Gordon Guyatt

Authorship: from credit to accountability

F. Alfonso & Editors’ Network, European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Task Force

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research typically proceeds in less predictable ways than we like to acknowledge. While a scientific ideal is that every part of a study is well considered and planned beforehand, and the research process thereafter mainly consists in performing according to protocol, a typical experience from the field is that such description is far from the truth. Planning and execution of plans are rarely that straightforward. To the contrary, many decisions are made along the way regarding both data collection and analysis: new experiments, comparisons, interviews, and surveys may be decided as the work proceeds, and additional analyses may be added to the ones originally decided upon. Sometimes these changes are driven by peer review. Some of the research contributions eventually pass critical scrutiny and make it into the paper, while others for one reason or another end up in the waste bin or are shelved for possible future use.

There may be positive as well as negative things to say about such practice in relation to the philosophy of science and meta science, relating to curiosity and creativity on the one hand and hypothesis testing and reproducibility issues on the other. Furthermore, some of the choices made regarding what results get included in papers may be objectionable from a research ethics perspective, such as excluding ‘negative results’ because they contradict the main results of the paper or are considered unworthy of publication, hence contributing to the positive publication bias (Chalmers et al., 1990 ; Connor, 2008 ; Dirnagl & Lauritzen, 2010 ). Other exclusions may be fully acceptable, based on estimations of relevance and the consideration that you cannot include everything in the paper if it is to be readable.

The present paper does not deal with what exclusions of research results are acceptable or not, but with a related issue, namely how to handle authorship attributions in papers where plans change along the way, so that some of the results derived are not included in the final version of the paper. This topic is a special case of the larger topic of who should be included as authors on research papers, which involves ethical aspects like appropriate allocation of credit in research (and, hence, fairness), transparency and accountability (Shamoo & Resnik, 2009 ). Given the frequency of authorship disagreements (Marušić et al., 2011 ; Nylenna et al., 2014 ; Okonta & Rossouw, 2013 ), this analysis is important also because good authorship practices serve to foster positive team dynamics and collaboration and are less likely to lead to authorship disputes, which could impact interpersonal and professional relationships and possibly lead to subsequent misbehaviors (Smith et al., 2020 ; Tijdink et al., 2016 ).

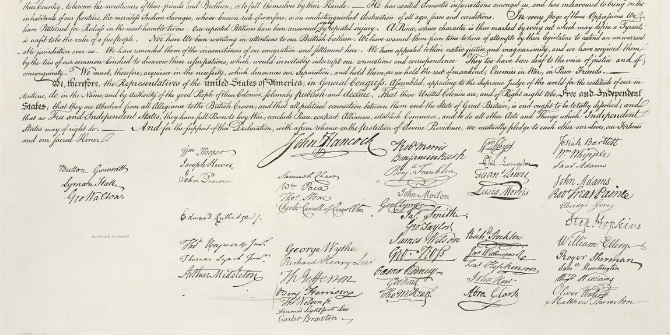

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) has produced the most widely acknowledged authorship recommendations, which serve as guidance for the biomedical sciences among other areas of scholarship (ICMJE, 2019 ). The recommendations provide a set of criteria that are jointly necessary and sufficient in order to determine authorship (see Box 1 ). While these authorship criteria have met their due share of criticism (Laflin et al. 2005 ; Osborne & Holland, 2009 ; Puljak & Sambunjak, 2000 ; Smith et al. 2014 ), we find them reasonable, although not flawless (see e.g. Helgesson & Eriksson, 2018 ; Helgesson et al 2019 ). We therefore treat the ICMJE criteria as the starting point for our discussion of whether granting authorship to someone can be justified even when that person’s specific contributions do not make it into the final version of the manuscript. However, the problem we have identified, having to do with the first criterion–that authors should have made a ‘substantial contribution’ to the work–is not clearly addressed by the ICMJE recommendations. In fact, the problem is overlooked by most suggestions for how to think about the allocation of authorship in co-researched papers (see e.g., Shamoo & Resnik, 2009 ; Hansson, 2017 ; Moffatt, 2018 ).

Hence, the aim of this paper is to determine, in relation to the ICMJE authorship criteria, how authorship should be handled in situations where researchers have contributed substantively to the research and drafting of the manuscript, but the results themselves are not included in the final manuscript. Before we discuss this issue in greater detail, we would like to flesh out the problem by providing a case.

A Case of Omitted Results

To recognize the problem we have in mind, consider the following case: Two senior researchers and three junior researchers work together on a study. One of the senior researchers take the main responsibility for conception and design of the study and assume the role of principal investigator (PI), while the other senior researcher helps substantially with suggestions and input regarding specific analyses, and also provides support in the lab, where the empirical data is obtained. The empirical work is divided among the three junior researchers Ann, Bo, and Choi in such a way that they are individually fully responsible for some part of the design and conducting the lab work, resulting in data collection, analysis and interpretation of results. As times passes, Ann, Bo, and Choi all spend many hours working hard and eventually deliver according to plan. When looking at the results and discussing the study further, all researchers on the team agree on the contents of the paper. It turns out that while the analyses made by Ann and Bo fit well with the final idea of the paper, Choi’s analyses fall outside the scope of the narrative eventually decided upon and are therefore at the end not included. This is where the discussion starts in the group. Should Choi be included as co-author? She will surely do her part in revising the manuscript and approve the final version to satisfy the second and third ICMJE criteria, but did she make a ‘substantial contribution’ to the work under the first criterion of the ICMJE recommendations? Choi has contributed to discussions throughout the life of the project at team meetings and did help in the design of her part of the experiments and conducted those studies, collected and analyzed the data, and helped interpret the results. However, she was unable to contribute to the overall conception and design of the project at this early stage of her career, similar to Ann and Bo. On an honest estimation, it can be concluded that she has not made a substantial contribution to the paper if the excluded results, her main contribution, do not make it into the final manuscript. So what to do?

Before we move on, let us notice that there are several possible reasons for not including Choi’s contribution in the paper. One reason could be that the quality of her work is too low. Another reason could be that her results are relevant but do not support the overall thesis of the paper–they are in this respect so-called negative results. As we have already indicated, omitting negative results might be problematic from a research ethics perspective, especially if the reason for omitting them is that they contradict one’s hypothesis. Footnote 1 However, another reason for not including Choi’s contribution could be that the results are taken not to be relevant (or relevant enough) to the paper eventually decided upon, meaning that her results helped shape the final story being told in the paper but were not being reported in the publication. For the sake of argument, our discussion in what follows assumes that the reason for omitting Choi’s contribution is ethically sound and does not constitute a research misbehaviour in its own right.

Substantial Contribution and Intellectual Involvement

As noted in the introduction, the problem we describe concerns the first ICMJE criterion for authorship. This criterion does two things: it tells us the broad categories of contributions that count towards authorship on the byline (conception or design, acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data), and it tells us the extent of contribution needed, namely that the contribution(s) have to be ‘substantial.’ For the sake of argument, let us assume that Choi’s research contributions would clearly have been substantial enough to grant a position on the paper if her data and analyses had been included in the manuscript. Now if they are not included, does it mean that Choi should not be listed as an author? And if she should, how is this compatible with the idea of a substantial contribution?

We believe that situations like Choi’s reveal that the ‘substantial contribution’ requirement of the ICMJE recommendations is not only vague in terms of what is required for a contribution to be large enough to be substantial (Cutas & Shaw, 2015 ; Laflin et al. 2005 ; Osborne & Holland, 2009 ), but also ambiguous in terms of what specifically counts as a contribution. In particular, we hold that we should distinguish between two interpretations of this criterion, namely whether it concerns a substantial contribution to what ends up in the paper or whether it concerns a substantial contribution to the research process leading up to the paper . While Choi does not qualify as an author in the former sense, she might do so if we accept the latter interpretation of the substantial contribution criterion. The question remains which of the two interpretations of ‘substantial contribution’ is the most plausible one.

To be certain, making a substantial contribution is not enough to qualify for authorship according to the ICMJE criteria. Critical revision and final approval of the manuscript outlined in the second and third ICMJE criteria is needed as well. The critical revision requires intellectual involvement in the paper under production. Hence, intellectual involvement in the research at hand is part of the ICMJE authorship requirements (Helgesson, 2015 ).

Before returning to our case, let us first present and consider another one in which the main point is to clearly show that one might make a substantial contribution to the research of a paper without contributing to what ends up in the paper. Assume that a group is writing a paper on research methods for accomplishing X in the research field of Z . They proceed by examining all existing methods mentioned in the literature potentially relevant for the specific purpose at hand, dividing the work among them so that each researcher involved analyzes the same number of methods each. The results from the analyses of the methods found to work are described at some length in the final paper, while failing methods are merely mentioned (although they are as completely documented by the research group). Since it is not known beforehand which methods will work and which ones will not, each analysis will be equally relevant to the fulfillment of the aim of the paper–to clarify the best methods to accomplish X . If the research contribution is substantial, and other authorship criteria are fulfilled, all researchers should be included as co-authors of the paper irrespective of whether their method is presented in the manuscript or not. Hence, there is a case to be made that substantial research contributions sometimes should count towards authorship even if they are not represented equally in the final paper.

Fairness, Transparency and Accountability

As previously detailed, we believe that cases like Choi’s reveal an ambiguity concerning the notion of ‘substantial contribution.’ It might be understood as saying that what is required is either a substantial contribution to what ends up in the paper or a substantial contribution to the research leading up to the paper. If the first interpretation is correct, then Choi should be excluded from authorship, despite the work and effort that she has put into this collaborative work. If Choi ought to be included in the paper, which we think she should, this is because it is enough, with respect to the first authorship criterion, that she has contributed in a substantial and relevant way to the research leading up to the paper, even if her specific empirical contributions did not end up in the paper. We will therefore defend this interpretation of the substantial contribution requirement of the ICMJE recommendations.

Generally, there are two sets of reasons for caring about how authorship is handled when a researcher makes a substantial contribution that is not reported in the manuscript. First, it is a matter of transparency and accountability about the research process: what happened and who were involved? From this perspective, it is misleading if people who were deeply involved in the work are not described in the paper. Also for reasons of accountability, those responsible for the work should be identifiable to others. Admittedly, both of these aspects could be fulfilled by some other means than that of attribution of authorship, such as a sufficiently detailed description of everyone’s contributions, including those not included as authors. But with present practices, including someone as co-author or merely listing that person in the contributor list or acknowledgements communicates two quite different messages about the person’s contribution and its relative importance. Our argument here for the interpretation that what counts as ground for co-authorship is a substantial contribution to the research leading to the paper is that excluding Choi would be misleading about her role in the project, hence not fulfilling the need for transparency and accountability.

Second, authorship is a matter of due scientific credit and fairness, which to our mind provides a strong reason for including Choi. In particular, our argument for the interpretation that what counts is a substantial contribution to the research leading to the paper is that excluding Choi seems unfair. After all, Choi has contributed as much to the research leading to the paper as her colleagues. Admittedly, the aim of the paper shifted, or took a form that made Choi’s contribution less relevant to what was reported in the paper, but not less relevant to the end product leading to the research publication. Also, we should note that this interpretation clearly ties Choi’s claim to authorship to the good work she has done rather than to the results being reported only. In contrast, if what is required is a substantial contribution to the research presented in the paper, then it seems that whether any of the junior researchers end up in the authorship byline will be, to some degree, a matter of luck , since neither an initial agreement or great efforts along the way is sufficient. This too seems unfair. Contributing with a considerable amount of good work and then not receiving authorship because of a change of plans seems unfair in a vein similar to misuse of the ICMJE authorship criteria by letting people contribute substantially to the work, then not offer them the opportunity to revise, and finally not include them as authors since they do not fulfill all criteria (ICMJE, 2019 ).

Counter Arguments

There are several possible counterarguments to our thesis that should be addressed. First, it might be argued that Choi’s contribution is rather general in its nature, and hence should not count towards authorship. After all, authorship is not about general research contributions, such as having contributed substantially to a large research application providing financial support for the production of many papers (reaching a level of detail that the application did not), but contributions to the specific paper (Smith & Master, 2017 ). Similarly, being a member of the research group does not mean that one should be included as co-author on every paper produced by the group. Instead, you need to contribute substantially to every paper in order to be listed as author. However, one may agree with the general thrust of this argument without agreeing that it works as an argument against including Choi. That is because it is an open question what should be meant by ‘contributions to the specific paper’–is it what the final version of the paper contains or is it the work specifically concerning and leading up to that paper? It seems to us that the better understanding of ‘research contribution’ is the work and intellectual engagement contributed in the context of a study or project around a specified research aim and/or a set of specified research questions, rather than what of that work was eventually included in the paper–as long as the work, as it was carried out, was perceived by the research group as relevant to what they were doing.

Second, one might ask why it would not be enough if Choi’s contribution were recognized through an acknowledgement, especially if it contains a clear statement of her contribution. Important contributions that do not qualify for authorship are often handled that way, so why shouldn’t we think that it is enough in this case? There are two connected responses to this inquiry. First, as already argued, Choi has made contributions qualifying her for authorship. Leaving her out would therefore be misleading in the sense that it would give a false impression about the relative value of her contribution to the research. Second, it would be utterly unfair to grant her an acknowledgement if her colleagues, making contributions of equal importance (according to our reasoning above), are included as authors. Again, as discussed above, allocation of authorship concerns transparency and accountability on the one hand, and credit and fairness on the other. Acknowledgements contribute to transparency, but are useless from a career perspective in most, if not all, research areas, hence leaving Choi with an inappropriate credit for her work. Footnote 2

Third, there is a complication with our interpretation of the substantial contribution requirement that we may call the multiplicity problem . Imagine that the overall thrust of our argument was followed by the research group and that Choi was included as co-author in the paper based on her substantial contributions to the work with the paper even though her work was not presented in the paper. Further imagine that later on, the senior researchers find it a good idea to include the previously excluded work by Choi in another paper where it becomes more relevant. The work then included is indeed substantial, which provides an argument why Choi should be included as co-author also in this second paper. But doesn’t this amount to an unfair form of double counting? In response, we think that it might be acceptable to include Choi as co-author on both papers, insofar as she fulfills the following two conditions: the contribution under the first criterion has to be different in the two papers (which is not the same thing as saying that the contribution has to concern different data sets), and the other ICMJE authorship criteria need to be fulfilled in relation to the second paper as well. Admittedly, Choi was not part of the research process, and perhaps not intellectually involved in the questions particularly addressed in this second paper, at an early stage. But once included with her empirical contribution (originally omitted and hence different from her contribution to the first paper), she could engage in the larger questions of this second paper and could contribute intellectually as well. For example, she could participate in the process of revising versions of the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, as put in the second criterion of the ICMJE authorship criteria. If so, then it seems right that she is included as an author also in the second paper since she fulfils criteria 1–4 in relation to that paper. Footnote 3

But then there seems to be a further complication with our account that we might call the backfire problem (which is a counter argument to our response to the multiplicity problem). Again, assume that Choi was included as an author on the first paper where her work was not presented in the paper itself, but that the work has also begun with the second paper based on Choi’s contribution. Ann and Bo now enter the scene and ask why they are not included in the second paper–should they be? After all, if Choi ought to be included as an author on the first paper, on the basis that her work with the omitted empirical contribution was an important part of the research process leading up to the first paper, then doesn’t this suggest that Ann and Bo can raise similar legitimate demands on being included as authors on the second paper? In response, we suggest that the answer can certainly not be a general ‘Yes,’ but that their inclusion in the second paper is justifiable if they were sufficiently involved in the second paper to be correctly described as having contributed substantially to the process leading up to that specific paper. For example, the second paper might be a natural follow-up of the first paper, covering further issues already considered while they were working on the first paper. Footnote 4 However, it all hinges on whether Ann and Bo contributed substantially, in the sense we have defended in the above.

Before concluding we should make two important remarks. First, our arguments in response to the multiplicity problem has important implications beyond the case that we are focusing on here. For example, when a biomedical researcher builds a new reagent and publishes it, the original creator does not (or at least should not) receive authorship recognition each and every time the reagent is shared and used by other scientists in subsequent studies. The reason for this, or so we would argue, is that merely providing certain substances or data is not enough to qualify as an author. What is important is rather that one has contributed substantially in the research process leading up to the paper. However, allowing people to use one’s innovation over and over does not guarantee the type of involvement required for authorship in a specific paper. Second, the focus of this paper has only been on authorship attribution, but cases like the one we discuss here also raise issues about authorship order, which is a contentious area with as yet no uniform policy or practice which guides researchers (Helgesson & Eriksson, 2019 ; Smith & Master, 2017 ). Addressing this issue is, however, beyond the scope of this paper.

Concluding Remarks

In this paper we have argued that authorship should be attributed to those who have made a substantial contribution to the specific research leading up to the publication, even if their particular contribution is not reported in the paper. Based on the principle of fairness and giving credit where credit is due, researchers who make significant contributions should be given authorship credit even if their contribution is not included in the final manuscript. We have argued that this practice is aligned with the most plausible interpretation of the first criterion of the ICMJE recommendations, and thus researchers should be afforded the opportunity to participate in fulfilling subsequent criteria including drafting or critically revising the manuscript, approving the final version of the paper, and agreeing to be accountable for the research. Based on our analysis, we suggest that ICMJE and others interested in authorship and publication ethics need to revise their proposals regarding authorship allocation for the sake of clarity.

As a suggestion for future research, further conceptual and empirical work in this area should examine and consider situations where substantive but excluded contributions deserve or not deserve authorship credit. While several studies examine gift authorship (e.g., Sauermann & Haeussler, 2017 ; Wislar et al 2011 ), less has been done to assess the nature and frequency of authorship exclusion, which is likely to be significant and affect those with less power in academic science (Cesi and Williams 2011; NASEM 2017).

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

There is much more to be said here. The handling of negative results has been discussed extensively in the research ethics literature, mainly in relation to selection bias when it comes to what studies get published and not. There are ethical issues involved here, relating to reasons for not publishing, such as researchers being misleading by withholding results, wasted resources, and introduction of bias into meta-analyses. The tendency to favor positive results is systemic (Chalmers, 1990 ; Duyx et al., 2017 ; Dwan et al., 2008 ; Fanelli, 2012 ; Song et al., 2000 ). Addressing these sorts of issues is beyond the scope of this paper, however, as our focus is to analyze the ethics of who should be included as authors in cases where not all work done has explicit impact on what ends up in print.

The fact that acknowledgements do not carry any weight from a career perspective might be a reason for ditching both acknowledgements and traditional author lists in favour of more detailed contributorship statements at the beginning of academic papers. Such a system would at best not only be more transparent, but also more accurate when it comes to the allocation of academic credit. That said, our argument here largely applies to the present situation, in which authorship is the norm.

We admit that our solution to the multiplicity problem still leaves open for disputes over authorship. After all, researchers might still disagree whether a particular contribution is sufficiently different from another one. That said, we still believe that what we say in response to the multiplicity problem is valid and should be adopted as a general starting point for how to handle this kind of disputes. Thus, we suggest that the principle is valid, even if the application of the principle can still be debated in individual cases.

We want to underline that we do not suggest that so-called salami-slicing should be acceptable. However, you do not get salami slicing just because you make more than one paper out of a data set. Salami slicing is if you separate your data into several papers merely in order to get more papers, not because it is justified for scientific considerations, such as making the content comprehensible and the story sufficiently clear for the reader to follow (not to mention managing limitations of space).

Chalmers, T. C., Frank, C. S., & Reitman, D. (1990). Minimizing the three stages of publication bias. JAMA, 263 (10), 1392–1395.

Article Google Scholar

Chalmers, I. (1990). Under reporting research is scientific misconduct. JAMA, 263 , 1405–1408.

Connor, J.T. (2008). Positive reasons for publishing negative findings. American Journal of Gastroenterology , Sep;103(9), 2181–2183.

Cutas, D., & Shaw, D. (2015). Writers blocked: On the wrongs of research co-authorship and some possible strategies for improvement. Science and Engineering Ethics, 21 (5), 1315–1329.

Dirnagl, U., & Lauritzen, M. (2010). Fighting publication bias: introducing the Negative Results section. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 30 , 1263–1264.

Duyx, B., Urlings, M. J. E., Swaen, G. H. M., Bouter, L. M., & Zeegers, M. P. (2017). Scientific citations favor positive results: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 88 , 92–101.

Dwan, K., Altman, D. G., Arnaiz, J. A., Bloom, J., Chan, A.-W., Cronin, E., et al. (2008). Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS ONE, 3 (8), e3801. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003081 .

Fanelli, D. (2012). Negative results are disappearing from most disciplines and countries. Scientometrics, 90 , 891–904.

Hansson, S. O. (2017). Who should be author? Theoria, 83 , 99–102.

Helgesson, G. (2015). Scientific authorship and intellectual involvement in the research – should they coincide? Medicine, Healthcare and Philosophy, 18 (2), 171–175.

Helgesson, G., Bülow, W., Eriksson, S., & Godskesen, T. (2019). Should the deceased be listed as authors? Journal of Medical Ethics, 45 (5), 331–338.

Helgesson, G., & Eriksson, S. (2019). Authorship order. Learned Publishing, 32 (2), 106–112.

Helgesson, G., & Eriksson, S. (2018). Revise the ICMJE Recommendations regarding authorship responsibility! Learned Publishing, 31 (3), 267–269.

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). (2019). Recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing, and publication of scholarly work in medical journals. Accessed 2 Oct, 2020 at http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/

Laflin, M. T., Glover, E. D., & McDermott, R. J. (2005). Publication ethics: An examination of authorship practices. American Journal of Health Behavior, 29 , 579–587.

Marušić, A., Bošnjak, L., & Jerončić, A. (2011). A systematic review of research on the meaning, ethics and practices of authorship across scholarly disciplines. PLoS ONE, 6 (9), e23477.

Moffatt, B. (2018). Scientific authorship, pluralism, and practice. Accountability in Research: policies and quality assurance, 25 (4), 199–211.

Academy, N., & of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM). . (2017). Fostering integrity in research . . The National Academies Press.

Google Scholar

Nylenna, M., Fagerbakk, F., & Kierulf, P. (2014). Authorship: Attitudes and practice among Norwegian researchers. BMC Medical Ethics, 15 (1), 53.

Okonta, P., & Rossouw, T. (2013). Prevalence of scientific misconduct among a group of researchers in Nigeria. Developing World Bioethics, 13 (3), 149–157.

Osborne, J. W., & Holland, A. (2009). What is authorship?, and what should it be A survey of prominent guidelines for determining authorship in scientific publications. Practical Assessment Research and Evaluation . https://doi.org/10.7275/25pe-ba85 .

Puljak, L., & Sambunjak, D. (2000). Can authorship be denied for contract work? Science and Engineering Ethics, 26 , 1031–1037.

Sauermann, H., & Haeussler, C. (2017). Authorship and contribution disclosures. Science . Advances, 3 (11), e1700404.

Shamoo, A. E., & Resnik, D. B. (2009). Responsible conduct of research . (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Book Google Scholar

Smith, E., & Williams-Jones, B. (2012). Authorship and responsibility in health sciences research: A review of procedures for fairly allocating authorship in multi-author studies. Science and Engineering Ethics, 18 (2), 199–212.

Smith, E., Hunt, M., & Master, Z. (2014). Authorship ethics in global health research partnerships between researchers from low or middle income countries and high income countries. BMC Medical Ethics, 15 , 42.

Smith, E., & Master, Z. (2017). Best practices to order authors in multi/interdisciplinary health science research publications. Accountability in Research: policies and quality assurance, 24 (4), 243–267.

Smith, E., Williams-Jones, B., Master, Z., Larivière, V., Sugimoto, C. R., Paul-Hus, A., et al. (2020). Misconduct and misbehavior related to authorship disagreements in collaborative science. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26 (4), 1967–1993.

Song, F., Eastwood, A., Gilbody, S., Duley, L., & Sutton, A. (2000). Publication and related biases: a review. Health Technology and Assessment, 4 (10), 1–115.

Tijdink, J. K., Schipper, K., Bouter, L. M., Maclaine Pont, P., de Jonge, J., & Smulders, Y. M. (2016). How do scientists perceive the current publication culture? A qualitative focus group interview study among Dutch biomedical researchers. British Medical Journal Open, 6 (2), e008681.

Wislar, J., Flanagin, A., Fontanarosa, P. B., & DeAngelis, C. D. (2011). Honorary and ghost authorship in high impact biomedical journals: a cross sectional survey. BMJ, 343 , d6128. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d6128 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

ZM’s involvement in this research project was supported by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Cancer for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS).

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. See Acknowledgements.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Stockholm Centre for Healthcare Ethics (CHE), Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Biomedical Ethics Research Program and Center for Regenerative Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Zubin Master

Department of Philosophy, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

William Bülow

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gert Helgesson .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Helgesson, G., Master, Z. & Bülow, W. How to Handle Co-authorship When Not Everyone’s Research Contributions Make It into the Paper. Sci Eng Ethics 27 , 27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00303-y

Download citation

Received : 02 October 2020

Accepted : 24 March 2021

Published : 12 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-021-00303-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Authorship criteria

- Negative results

- Substantial contribution

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- About the LSE Impact Blog

- Comments Policy

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

- Subscribe to the Impact Blog

- Write for us

- LSE comment

March 29th, 2021

A simple guide to ethical co-authorship.

7 comments | 304 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Historically the single authored paper has been a mainstay of social scientific and humanistic research writing. However, co-authorship is now for many social science disciplines the default mode of academic authorship. Reflecting on this, Helen Kara , provides some key insights and advice for authors looking to co-write and co-publish in an ethical way.

Ethical co-authorship is rarely discussed by authors and publishers, and even more rarely by research ethics committees. Yet co-authorship is a notorious site for unethical practices such as; plagiarism, citation manipulation, and ghost , guest , and gift authors. For authors setting out on a collaborative writing project, two key aspects to ethical co-authorship need consideration: ethical co-writing, and ethical co-publishing.

Ethical co-writing

Being invited to write with one or more others can feel flattering and exciting. Hold on, though, because before you co-write a single sentence, it is sensible to figure out whether you can work well together and to ask yourself some simple questions. Do you share enough priorities and values? If so, do you have similar working practices, such as attitudes to timescales and deadlines? While diversity of authorship will bring richness to your co-authored work, you need enough similarity to ensure that you can work well together. There is no shame in finding you can’t collaborate with someone; it doesn’t devalue your scholarship or theirs. But, it is worth ensuring you make that discovery early, rather than after you have already invested considerable time and effort.

Agree on the format for the work, and who will take the lead on each section or chapter. Different people can have very different ideas about format and structure, and again it is worth establishing this at the outset, rather than ending up with sections or chapters of wildly varying lengths and structures. This won’t impress reviewers and will create an unnecessarily large amount of work at the editing stage.

If you want to have everything your own way – write alone

When you decide on deadlines, always build in contingency time. Things go wrong in people’s lives, particularly during a pandemic, and those affected need time to deal with their difficulties. Be willing to compromise or, in a group collaboration, to be outvoted. If you want to have everything your own way – write alone – though you will still have to deal with others, reviewers and editors; to adapt a famous saying, the sole-authored paper is dead.

Encourage your co-authors to adopt ethical citation practices. This means avoiding citation manipulation , i.e. excessive self-citation, excessive citation of another’s work, or excessive citation of work from the journal or publisher where you want to place your own work. It also means ensuring a good level of diversity within your citations. Who are the marginalised scholars working in your field: the people of colour, the women, the Indigenous scholars, the scholars from the global South, the LGBT+ scholars, and so on? Make sure you read and cite their work, engaging in co-writing can be an opportunity to reassess what literatures have become central to your research.

When you give feedback to your co-authors, make it constructive: tell them what they are doing well, what needs improvement, and how they can make that improvement. When co-authors give you feedback on your writing, accept it gracefully, even if you don’t feel very graceful. Respond positively, or at least politely, or at worst diplomatically. Maintaining relationships with your co-authors can be more important and may even take precedence over being right.

Do what you say you’re going to do, when you say you’re going to do it. If you have a problem that is going to get in the way of your co-authoring, let your co-author(s) know as soon as possible.

Ethical co-publishing

Academic publishing is troubled by ghost, guest, and gift authors, if you are in doubt, COPE provides a useful flowchart detailing these practices. Ghost authors are those who have contributed to a publication but are not named as a co-author, perhaps because they are a doctoral student or early career academic and a senior academic has decided to take the credit for their work. This is a form of plagiarism. Guest authors are those who have not contributed to the writing of a publication, though they may have lent equipment or run the organisation where the research took place. Gift authors are those who have made no contribution at all, but are offered co-author status as a favour. None of these practices are ethical. It doesn’t matter if some co-authors do more work than others, as long as everyone involved is happy with that, but you should be clear about each co-author’s contribution to the work , and outline that in a statement in the final draft.

Another ethical issue in co-publication is the order in which authors are named. This varies between disciplines. In economics, co-authors of journal articles are named in alphabetical order, while in sociology the co-author who has made the largest contribution is named first. Heather Sarsons studied this and found that the system used in economics has an adverse effect on academic women’s career prospects, while the sociological system does not.

Acting ethically while co-writing is easier than acting ethically to co-publish, because authors have more autonomy while writing

However, this does not mean the sociology system is perfect. What if two or three authors have contributed equally? An alternative option could be to write enough articles or chapters for each co-author to have first authorship on one of them, but this isn’t always possible or desirable. Some scholars use pseudonyms to ensure that equal contributions are recognised. Economic geographers Julie Graham and Katherine Gibson published several books and journal articles under the joint name J.K. Gibson-Graham , some of which were ‘sole’ authored and some with other co-authors. Geographers Caitlin Cahill, Sara Kindon, Rachel Pain and Mike Kesby have published together under the name Mrs C. Kinpaisby-Hill , and Kindon, Pain and Kesby have collectively used the name Mrs Kinpaisby. Professors EJ Renold and Jessica Ringrose work together as EJ Ringold.

This isn’t always an option, though, as publishers are not always happy to take an unconventional route. Book publishers for instance, will usually want as first author the person whose name they consider most likely to help sell copies. And, journal editors are sometimes reluctant to name participants who have co-authored journal articles, even when they evidently want to be named .

Acting ethically while co-writing is easier than acting ethically to co-publish, because authors have more autonomy while writing. Self-publishing may present opportunities for more creative representations of co-authorship practices, but self-published work is not generally valued by academia. Bumping up against the structures and priorities of big business, whether a publisher or a university, can make it more difficult for people to maintain an ethical course. Perhaps the most ethical option is to place work with a journal or publisher that is not for profit, so you are not contributing to shareholders’ dividends but to organisations that invest any surplus back into research dissemination.

To some extent, co-authorship is an academic virtue in itself. Co-authors learn from each other and help each other develop as researchers and scholars. Co-authored work is often stronger than it would have been if sole-authored. If we can also co-author ethically, that will further improve the quality of our collaborations and our outputs.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Adapted from Gordon Johnson via Pixabay.

About the author

Dr Helen Kara has been an independent researcher since 1999 and also teaches research methods and ethics. She is not, and never has been, an academic, though she has learned to speak the language. In 2015 Helen was the first fully independent researcher to be conferred as a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences. She is also an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the Cathie Marsh Institute for Social Research, University of Manchester. She has written widely on research methods and ethics, including Research Ethics in the Real World: Euro-Western and Indigenous Perspectives (2018, Policy Press).

Thank you Dr.. Kara for these ethical guideline. Best, Ayat

Really useful post, thank you. I’d add that when you co-author you’re penalised if you surname is lower down the alphabet, as you get relegated to et al. It means it can be more ‘political’ when negotating order of names as you have to request/ask/make a case to move into first position, when someone earlier in the alphabet can assume they will be first. Maybe I should change my surname to Awoodthorpe 😀

To add, you are penalised if your surname is lower down the alphabet when co-authoring, as you have to make a case/neogitate/request to move up the order or to first author. To do so can be difficult as you have to demonstrate that you did most of the work. Those authors who are earlier in the alphabet can expect to be first otherwise, and the quick interpretation is that they are the ‘lead author’ as everyone else is relegated to et al.

- Pingback: Quick Tips on Being an Ethical Co-Writer - Social Science Space

“It also means ensuring a good level of diversity within your citations. Who are the marginalised scholars working in your field: the people of colour, the women, the Indigenous scholars, the scholars from the global South, the LGBT+ scholars, and so on? Make sure you read and cite their work, engaging in co-writing can be an opportunity to reassess what literatures have become central to your research.”

What sound ethical framework demands that one cite works based on the immutable characteristics of the author?

Is this affirmative action of scholarship? One would think that, perhaps, we should cite authors based on their contributions to their fields rather than their skin tone, country of origin, anatomy, etc.

- Pingback: A Simple Guide to Ethical Co-Authorship | LSE Review of Books

- Pingback: Uitgelicht en gespot op internet (week 12 & 13, 2021) – Vincent Bontrop

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Related Posts

CRediT Check – Should we welcome tools to differentiate the contributions made to academic papers?

January 20th, 2020.

Book Review: Research Ethics in the Real World by Helen Kara

July 21st, 2019.

Writing for edited collections represents a model for a creative academic community unfairly rejected by the modern academy

June 12th, 2020.

5 Strategies for writing in turbulent times

March 30th, 2020.

Visit our sister blog LSE Review of Books

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CORRESPONDENCE

- 24 August 2021

First authors: is co-equal genuinely equal?

- Jonathan Kipnis 0

Washington University in St. Louis, St Louis, Missouri, USA.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

‘Equal’ distribution of co-first authors on research papers should be a win–win concept — not just for those authors, but also for multi-disciplinary science. Yet some seek to reshuffle their respective positions on CVs for career purposes. How can we ensure that co-equal means genuinely equal?

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 596 , 486 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02310-2

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests

Related Articles

See more letters to the editor

Rwanda 30 years on: understanding the horror of genocide

Editorial 09 APR 24

Three ways ChatGPT helps me in my academic writing

Career Column 08 APR 24

‘Without these tools, I’d be lost’: how generative AI aids in accessibility

Technology Feature 08 APR 24

Is ChatGPT corrupting peer review? Telltale words hint at AI use

News 10 APR 24

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Postdoctoral Associate- Comparative Medicine

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Group Leader at Católica Biomedical Research Centre and Assistant or Associate Professor at Católica

Group Leader + Assistant/Associate Professor, tenure-track position in Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Data Science, Engineering, related fields.

Portugal (PT)

Católica Biomedical Research Centre

Faculty Positions at SUSTech Department of Biomedical Engineering

We seek outstanding applicants for full-time tenure-track/tenured faculty positions. Positions are available for both junior and senior-level.

Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

Southern University of Science and Technology (Biomedical Engineering)

Locum Associate or Senior Editor, Nature Cancer

To help us to build on the success of Nature Cancer we are seeking a motivated scientist with a strong background in any area of cancer research.

Berlin, Heidelberg or London - Hybrid working model

Springer Nature Ltd

Postdoctoral Research Fellows at Suzhou Institute of Systems Medicine (ISM)

ISM, based on this program, is implementing the reserve talent strategy with postdoctoral researchers.

Suzhou, Jiangsu, China

Suzhou Institute of Systems Medicine (ISM)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Defining the Role of Authors and Contributors

Page Contents

- Why Authorship Matters

- Who Is an Author?

- Non-Author Contributors

- Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology

1. Why Authorship Matters

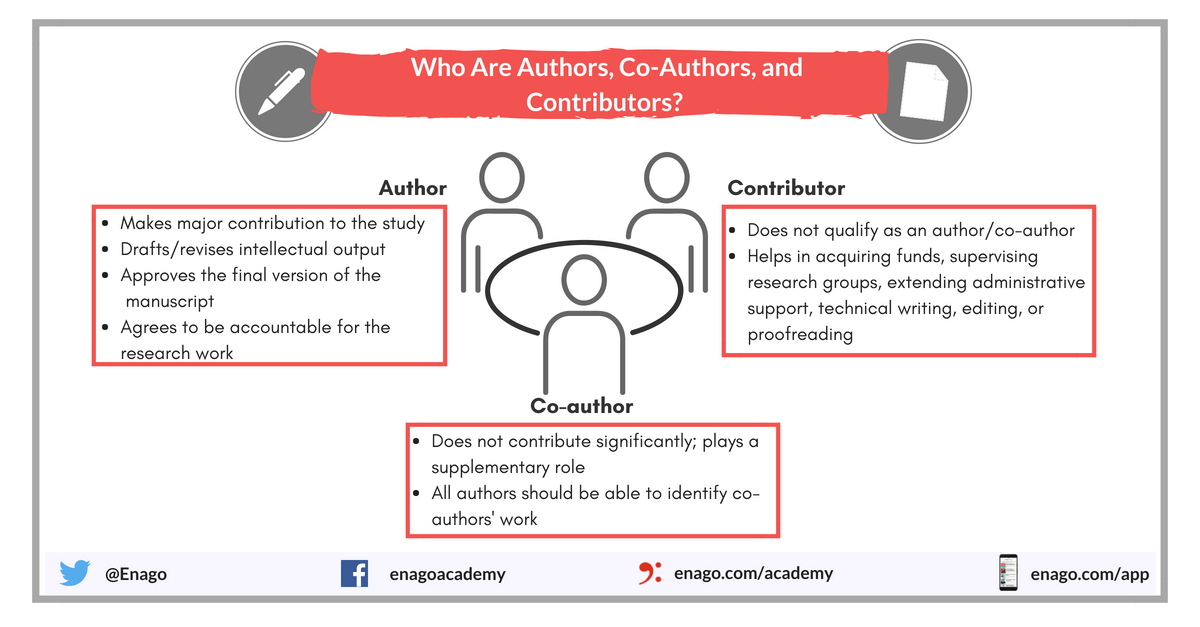

Authorship confers credit and has important academic, social, and financial implications. Authorship also implies responsibility and accountability for published work. The following recommendations are intended to ensure that contributors who have made substantive intellectual contributions to a paper are given credit as authors, but also that contributors credited as authors understand their role in taking responsibility and being accountable for what is published.

Editors should be aware of the practice of excluding local researchers from low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) from authorship when data are from LMICs. Inclusion of local authors adds to fairness, context, and implications of the research. Lack of inclusion of local investigators as authors should prompt questioning and may lead to rejection.

Because authorship does not communicate what contributions qualified an individual to be an author, some journals now request and publish information about the contributions of each person named as having participated in a submitted study, at least for original research. Editors are strongly encouraged to develop and implement a contributorship policy. Such policies remove much of the ambiguity surrounding contributions, but leave unresolved the question of the quantity and quality of contribution that qualify an individual for authorship. The ICMJE has thus developed criteria for authorship that can be used by all journals, including those that distinguish authors from other contributors.

2. Who Is an Author?

The ICMJE recommends that authorship be based on the following 4 criteria:

- Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND

- Drafting the work or reviewing it critically for important intellectual content; AND

- Final approval of the version to be published; AND

- Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

In addition to being accountable for the parts of the work done, an author should be able to identify which co-authors are responsible for specific other parts of the work. In addition, authors should have confidence in the integrity of the contributions of their co-authors.

All those designated as authors should meet all four criteria for authorship, and all who meet the four criteria should be identified as authors. Those who do not meet all four criteria should be acknowledged—see Section II.A.3 below. These authorship criteria are intended to reserve the status of authorship for those who deserve credit and can take responsibility for the work. The criteria are not intended for use as a means to disqualify colleagues from authorship who otherwise meet authorship criteria by denying them the opportunity to meet criterion #s 2 or 3. Therefore, all individuals who meet the first criterion should have the opportunity to participate in the review, drafting, and final approval of the manuscript.

The individuals who conduct the work are responsible for identifying who meets these criteria and ideally should do so when planning the work, making modifications as appropriate as the work progresses. We encourage collaboration and co-authorship with colleagues in the locations where the research is conducted. It is the collective responsibility of the authors, not the journal to which the work is submitted, to determine that all people named as authors meet all four criteria; it is not the role of journal editors to determine who qualifies or does not qualify for authorship or to arbitrate authorship conflicts. If agreement cannot be reached about who qualifies for authorship, the institution(s) where the work was performed, not the journal editor, should be asked to investigate. The criteria used to determine the order in which authors are listed on the byline may vary, and are to be decided collectively by the author group and not by editors. If authors request removal or addition of an author after manuscript submission or publication, journal editors should seek an explanation and signed statement of agreement for the requested change from all listed authors and from the author to be removed or added.

The corresponding author is the one individual who takes primary responsibility for communication with the journal during the manuscript submission, peer-review, and publication process. The corresponding author typically ensures that all the journal’s administrative requirements, such as providing details of authorship, ethics committee approval, clinical trial registration documentation, and disclosures of relationships and activities are properly completed and reported, although these duties may be delegated to one or more co-authors. The corresponding author should be available throughout the submission and peer-review process to respond to editorial queries in a timely way, and should be available after publication to respond to critiques of the work and cooperate with any requests from the journal for data or additional information should questions about the paper arise after publication. Although the corresponding author has primary responsibility for correspondence with the journal, the ICMJE recommends that editors send copies of all correspondence to all listed authors.

When a large multi-author group has conducted the work, the group ideally should decide who will be an author before the work is started and confirm who is an author before submitting the manuscript for publication. All members of the group named as authors should meet all four criteria for authorship, including approval of the final manuscript, and they should be able to take public responsibility for the work and should have full confidence in the accuracy and integrity of the work of other group authors. They will also be expected as individuals to complete disclosure forms.

Some large multi-author groups designate authorship by a group name, with or without the names of individuals. When submitting a manuscript authored by a group, the corresponding author should specify the group name if one exists, and clearly identify the group members who can take credit and responsibility for the work as authors. The byline of the article identifies who is directly responsible for the manuscript, and MEDLINE lists as authors whichever names appear on the byline. If the byline includes a group name, MEDLINE will list the names of individual group members who are authors or who are collaborators, sometimes called non-author contributors, if there is a note associated with the byline clearly stating that the individual names are elsewhere in the paper and whether those names are authors or collaborators.

3. Non-Author Contributors

Contributors who meet fewer than all 4 of the above criteria for authorship should not be listed as authors, but they should be acknowledged. Examples of activities that alone (without other contributions) do not qualify a contributor for authorship are acquisition of funding; general supervision of a research group or general administrative support; and writing assistance, technical editing, language editing, and proofreading. Those whose contributions do not justify authorship may be acknowledged individually or together as a group under a single heading (e.g. "Clinical Investigators" or "Participating Investigators"), and their contributions should be specified (e.g., "served as scientific advisors," "critically reviewed the study proposal," "collected data," "provided and cared for study patients," "participated in writing or technical editing of the manuscript").

Because acknowledgment may imply endorsement by acknowledged individuals of a study’s data and conclusions, editors are advised to require that the corresponding author obtain written permission to be acknowledged from all acknowledged individuals.

Use of AI for writing assistance should be reported in the acknowledgment section.

4. Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology

At submission, the journal should require authors to disclose whether they used artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technologies (such as Large Language Models [LLMs], chatbots, or image creators) in the production of submitted work. Authors who use such technology should describe, in both the cover letter and the submitted work in the appropriate section if applicable, how they used it. For example, if AI was used for writing assistance, describe this in the acknowledgment section (see Section II.A.3). If AI was used for data collection, analysis, or figure generation, authors should describe this use in the methods (see Section IV.A.3.d). Chatbots (such as ChatGPT) should not be listed as authors because they cannot be responsible for the accuracy, integrity, and originality of the work, and these responsibilities are required for authorship (see Section II.A.1). Therefore, humans are responsible for any submitted material that included the use of AI-assisted technologies. Authors should carefully review and edit the result because AI can generate authoritative-sounding output that can be incorrect, incomplete, or biased. Authors should not list AI and AI-assisted technologies as an author or co-author, nor cite AI as an author. Authors should be able to assert that there is no plagiarism in their paper, including in text and images produced by the AI. Humans must ensure there is appropriate attribution of all quoted material, including full citations.

Next: Disclosure of Financial and Non-Financial Relationships and Activities, and Conflicts of Interest

Keep up-to-date Request to receive an E-mail when the Recommendations are updated.

Subscribe to Changes

- New! Member Benefit New! Member Benefit

- Featured Analytics Hub

- Resources Resources

- Member Directory

- Networking Communities

- Advertise, Exhibit, Sponsor

- Find or Post Jobs

- Learn and Engage Learn and Engage

- Bridge Program

- Compare AACSB-Accredited Schools

- Explore Programs

- Advocacy Advocacy

- Featured AACSB Announces 2024 Class of Influential Leaders

- Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging

- Influential Leaders

- Innovations That Inspire

- Connect With Us Connect With Us

- Accredited School Search

- Accreditation

- Learning and Events

- Advertise, Sponsor, Exhibit

- Tips and Advice

- Is Business School Right for Me?

Ensuring Ethics and Integrity in Co-Authorship

- When faculty’s career progress relies on the number of peer-reviewed journal articles they publish, it can lead to unethical research practices such as gift authorship.

- Over the years, the number of co-authored research papers has increased considerably—a trend driven, in part, by the pressure on junior faculty to increase publications.

- To maintain the integrity of co-authored research, business schools can follow guidelines for authorship similar to those set in the medical and scientific fields.

While teaching and service are important to a professor’s career, research is the true hard currency in academe—the familiar adage “publish or perish” remains very relevant. Endowed chairs and other special appointments are often based on research output above all else, while tenure and promotions most often depend on the number of peer-reviewed journal articles that professors have published. While there are questions about the overall value of peer-reviewed articles, they are nonetheless sine qua non for a successful academic career.

Faculty scholarship also is an important pillar of AACSB’s accreditation standards . Whether professors are categorized as Scholarly Academics (SA) or another category is based on whether they are engaged in research or activities that link them to practice. According to AACSB’s standards, “normally, a minimum of 40 percent of a school’s faculty resources are SA.” That means that consistent publication output among a majority of full-time faculty is essential for a school to obtain and maintain AACSB accreditation.

Many types of research are important to AACSB-member schools. For example, to fulfill AACSB’s Standard 9, which is dedicated to societal impact, a school’s faculty can publish public policy briefs, opinion pieces, and trade articles that have an impact on practice, regulations, or society as a whole. These forms of scholarship can have tremendous reach—more people will read an opinion piece in a newspaper than will likely ever read a peer-reviewed journal article.

One especially fruitful area of research—that both supports SA qualification and often leads to societal impact—is co-authored scholarship. Co-authored research is often a product of a vibrant academic culture. When professors are excited and passionate about their research, they are more likely to share ideas among colleagues and transfer knowledge from research findings to students, which can lead to more research collaborations. And when faculty within the same school co-author articles, they create a valuable cross-pollination of ideas and an even more collaborative environment.

But if professors employ unethical co-authorship practices, it can destroy collegiality and create an antagonistic culture. That’s why it’s important for schools and their faculty to ensure that co-authoring relationships remain ethical, transparent, and productive.

Criteria for Ethical Co-Authorship

Most business schools are already well-versed in using journal rankings, impact factors, and acceptance rates to determine the “value” of different research publications. Many schools use resources such as Cabells’ Journalytics to find legitimate peer-review journals, as well as its Predatory Reports to avoid journals that do not meet their publication quality standards and practices.

But academic administrators spend less time ensuring that their faculty follow best practices concerning publication ethics. This is true even though concerns about co-authorship are held across academia.

Over the years, the number of co-authored research studies has steadily increased . One reason for this trend is likely that increased publication requirements can lead to “senior faculty feeling pressured to ‘help out’ junior faculty members,” according to a 2017 article by C.W. Von Bergen, professor of management, and Martin Bressler, professor of marketing and management, both of Southeastern Oklahoma State University in Durant. Bergen and Bressler note that author inflation in the form of gift and guest authorship, in which a co-author contributes little to no work to a scholarly paper, is increasingly common.

An increasing number of journal editors are adopting policies to ensure co-authorship integrity.

Some discipline-based associations already have published guidelines discouraging this practice. For example, the International Council of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) lists four criteria necessary for ethical co-authorship. According to the organization, to be considered a legitimate co-author, a researcher must take all four of the following actions:

- Make substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work.

- Draft the work or revise it critically for important intellectual content.

- Give final approval of the version to be published.

- Agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work and ensure that any questions related to the work’s accuracy or integrity are appropriately investigated and resolved.

“Contributors who meet fewer than all four of the above criteria for authorship should not be listed as authors, but they should be acknowledged,” the ICMJE concludes. “Examples of activities that alone (without other contributions) do not qualify a contributor for authorship are acquisition of funding; general supervision of a research group or general administrative support; and writing assistance, technical editing, language editing, and proofreading.”

Although intended for medical journal editors and authors, these criteria have since been adopted by many academic disciplines and organizations. This includes the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), which is perhaps the largest organization providing guidance on publication ethics. A nonprofit organization with more than 12,000 members, COPE is more well-known in the scientific community, but it is increasingly serving as a resource for all academic fields, including business disciplines.

COPE sets out detailed guidelines designed to help authors and editors avoid misconduct related to publishing, intellectual property, conflicts of interest, and other publishing and post-publication policies. These guidelines are largely based on ICMJE’s four criteria mentioned above. In addition, COPE provides many cases, seminars, and webinars to help journal editors and academics ensure co-authorship integrity.

An increasing number of journal editors are adopting COPE/ICMJE policies to ensure co-authorship integrity. Journals and research organizations can modify these criteria as needed or adopt them completely.

Best Practices for Co-Authored Research

There are several ways that AACSB-member business schools can ensure that their researchers follow and understand co-authorship best practices. First, administrators should educate faculty on the best practices for co-authorship outlined by ICMJE and COPE.

Second, before beginning any collaboration, potential co-authors can prepare an agreement that outlines clear expectations of each participant. Such agreements help prevent conflicts or misunderstandings later on in the research process.

Co-author agreements outline clear expectations of each participant and help prevent conflicts or misunderstandings later on in the research process.

Biologists Richard B. Primack, John A. Cigliano, and Chris Parsons provide a template for a co-author agreement in a 2019 editorial (researchers can also find other examples online). Their template includes five parts:

- First, the co-author agreement should outline the project’s goals and vision, so colleagues share the same vision and understand the scope of the plan.

- Second, the agreement should clearly define the roles and responsibilities for all parties involved.

- Third, it should address contingencies for handling potential disagreements.

- Fourth, it should include rules for governing communication of the project to ensure transparent interaction among all parties.

- Finally, all parties should disclose any real or perceived conflicts of interest.

The goal of such an agreement is to inspire trust among all parties, argue Primack, Cigliano, and Parsons. “Research tells us that trust is among the most important factors in successful collaborations—it is difficult for a team to succeed without it,” they write. “If co-authors do not trust each other, they can begin to question each other ’ s motivations and actions in every situation.” For this reason, any correspondence is best done in writing so that there is a record and contributors can review each other’s thoughts more carefully.

As research co-authorship becomes more prevalent in academia, the practice of gift authorship should be prohibited by all AACSB-member business schools. But when collaborating scholars set out clear agreements, contribute equally to the effort, communicate transparently, and remain accountable for their work, they can ensure that co-authorship remains an ethical and productive endeavor for their institutions, and for academia as a whole.

We use cookies on this site to enhance your experience

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

A link to reset your password has been sent to your email.

Back to login

We need additional information from you. Please complete your profile first before placing your order.

Thank you. payment completed., you will receive an email from us to confirm your registration, please click the link in the email to activate your account., there was error during payment, orcid profile found in public registry, download history, understanding co-authorship and managing it successfully.

- Charlesworth Author Services

- 20 May, 2022

The last few decades have seen a shift in authorship patterns, from more of single-author papers to more of multi-author papers. Evidence-based research often requires larger data sets, frequently contributed by multiple research teams. The multi-authored paper now represents the norm , especially in STEM publishing. With more authors, however, certain questions arise that need to be tackled. In this article, we discuss the various intricacies involved in co-authorship.

Need for co-authorship

These days, research projects increasingly involve the accumulation of larger datasets, complex study design, statistical analysis and extensive coordination among numerous research centres. The greater the scope, complexity and multidisciplinary collaboration and involvement of a study, the greater the need for multiple co-authors. With numerous colleagues from diverse fields contributing to a study, r esearch papers are able to put forth stronger conclusions and tend to be produced more efficiently . Ideas are shared among multiple fields, and the scientific process benefits as a whole .

Dimensions of co-authorship

However, the ‘full flavour’ of co-authorship is more than merely indicating two or more people as authors on a paper. Authorship , or co-authorship, indicates many things:

- It shows who exerted substantial effort in the design , execution of research, analysis of the data and writing of the paper.

- It denotes ownership and responsibility for the content of the paper.

- In rare circumstances, (co-)authorship can implicate specific individuals if their research is determined to be spurious or inaccurate.

Deciding co-authorship

To determine precisely who should be listed as a co-author, what constitutes authorship and the order of authors, proceed as follows.

- The IFA will also indicate how many authors can be included for a given type of manuscript.

- Contributors who don’t meet the threshold for authorship can be listed in the Acknowledgements section .

- Consult with your department chair to determine their advice on order of author placement.

Determining the order of authors

Co-authorship has some traditional conventions.

- Papers arising from Pacific Rim centres (or the Global East ) often place the senior author at the front, with successively junior authors (who often put in the most effort on the papers) afterwards.

- In the case of studies from the United States (or more broadly, the Global West ), the ‘main’ or ‘lead’ author is usually listed first, with the senior authors listed last.

Note : These conventions are constantly changing, and at the time of writing, there is no standard global guideline for listing the order of authors.

Best practices for managing co-authorship during submission and revision

- Before the paper is submitted to a journal, make sure all authors (and acknowledged contributors) are in agreement with the order of authors.

- Be sure to give credit to all appropriate study contributors by crediting them as authors or listing them in the Acknowledgments section . Be sure not to leave any significant contributors off the author (or acknowledgment) list, as adding authors after submission becomes a very difficult challenge.

- If at all possible, do not change the number or order of authors after initial submission . Do not add more authors or change the order of authors during the revision stage unless they are needed to conduct further experiments which require additional researchers.

- If you do feel the need to add authors, clearly indicate the addition and rationale to the editorial office when you resubmit the paper. Don’t give any appearance of trying to ‘sneak in’ a new author or two!

- Be very careful when using ghost authors to write your paper. Again, consult your journal’s IFA or contact their editorial office to determine correct protocols. (Having your paper edited by a professional copy-editor or editing service , however, is an acceptable practice.)

Follow these guidelines, and you will be celebrating with your entire author and research team when your paper is accepted and published!

Maximise your publication success with Charlesworth Author Services.

Charlesworth Author Services, a trusted brand supporting the world’s leading academic publishers, institutions and authors since 1928.

To know more about our services, visit: Our Services

Share with your colleagues

Related articles.

Who gets the CRediT? Authorship issues and fairness in academic writing

Charlesworth Author Services 15/07/2019 00:00:00

What to include in your Acknowledgments section

Charlesworth Author Services 02/06/2018 00:00:00

Issues of Problematic Authorship in scientific publishing

Charlesworth Author Services 23/12/2021 00:00:00

Related webinars

Bitesize Webinar: Research and Publication Ethics: Module 1 – Conducting Ethical Research

Charlesworth Author Services 23/03/2021 00:00:00

Bitesize Webinar: Research and Publication Ethics: Module 2 – Understanding Ethical Publishing

Bitesize Webinar: Research and Publication Ethics: Module 3 – Avoiding Plagiarism

Charlesworth Author Services 24/03/2021 00:00:00

Bitesize Webinar: Research and Publication Ethics: Module 5 – Conflicts of Interest and Intellectual Property

Understanding and following the Information for Authors (Author Guidelines)

Charlesworth Author Services 12/01/2022 00:00:00

Collaborating in research: Purpose and best practices

Charlesworth Author Services 24/02/2022 00:00:00

Skills needed for Multidisciplinary Research

Charlesworth Author Services 07/12/2021 00:00:00

Office of the Provost