Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

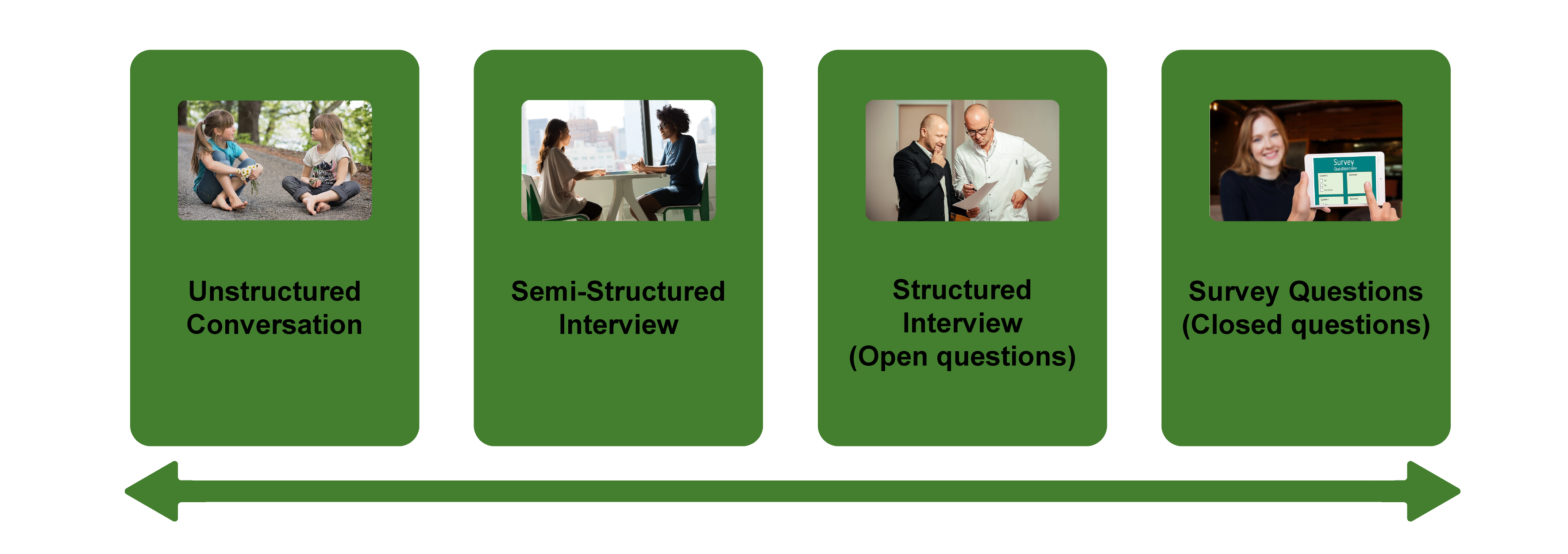

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

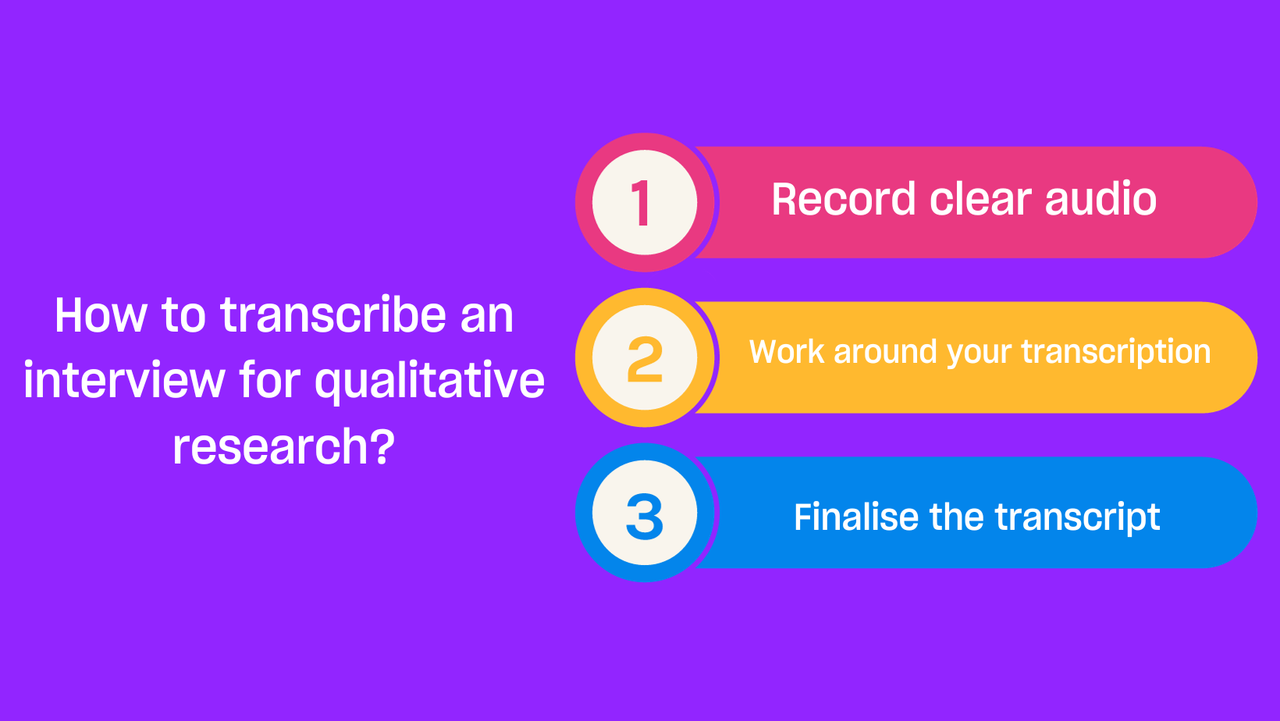

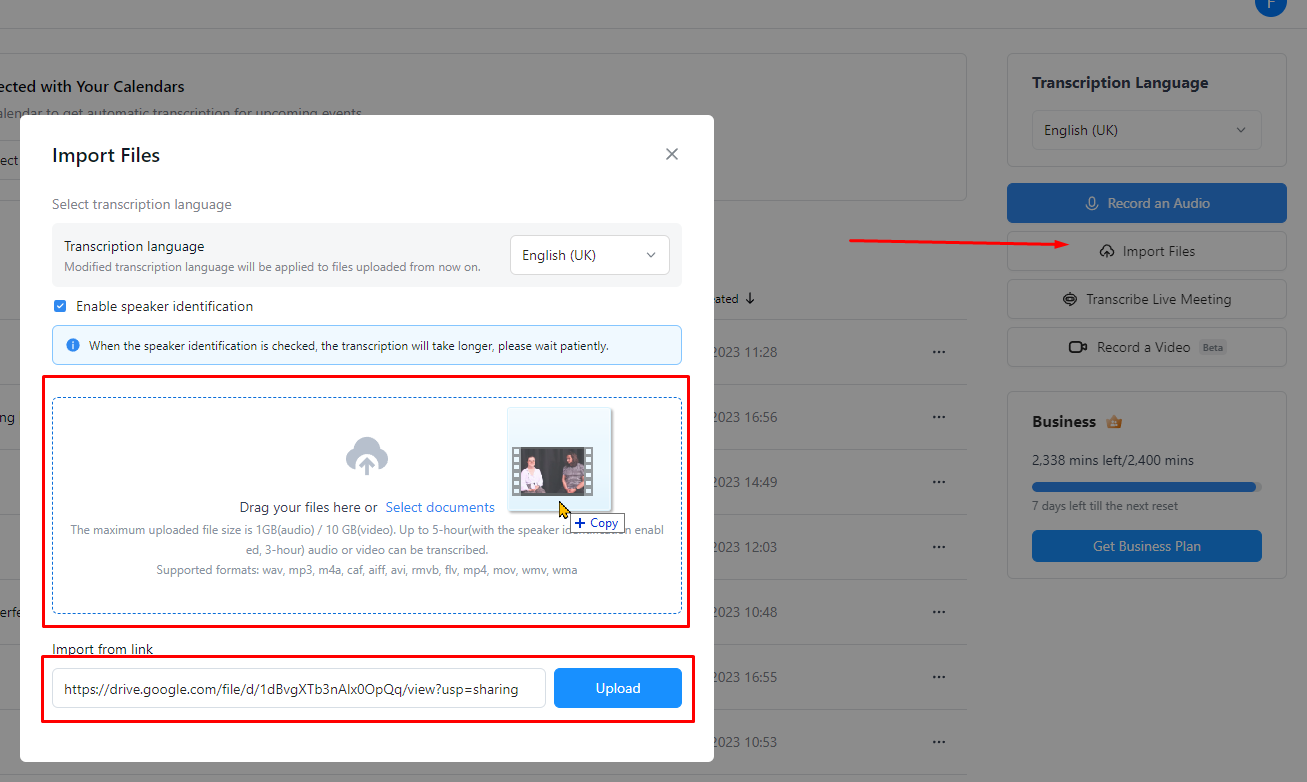

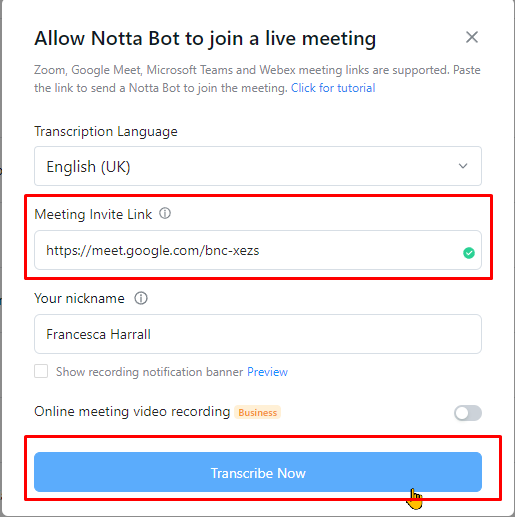

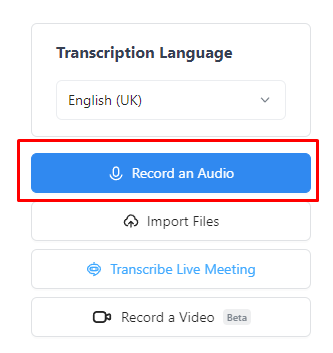

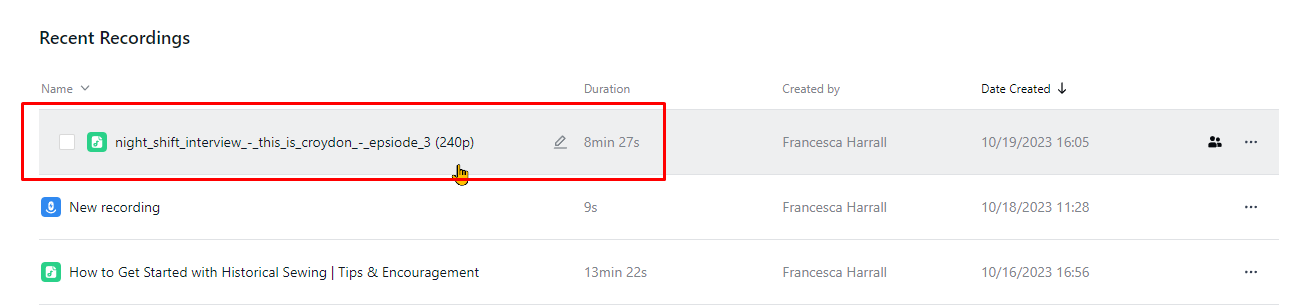

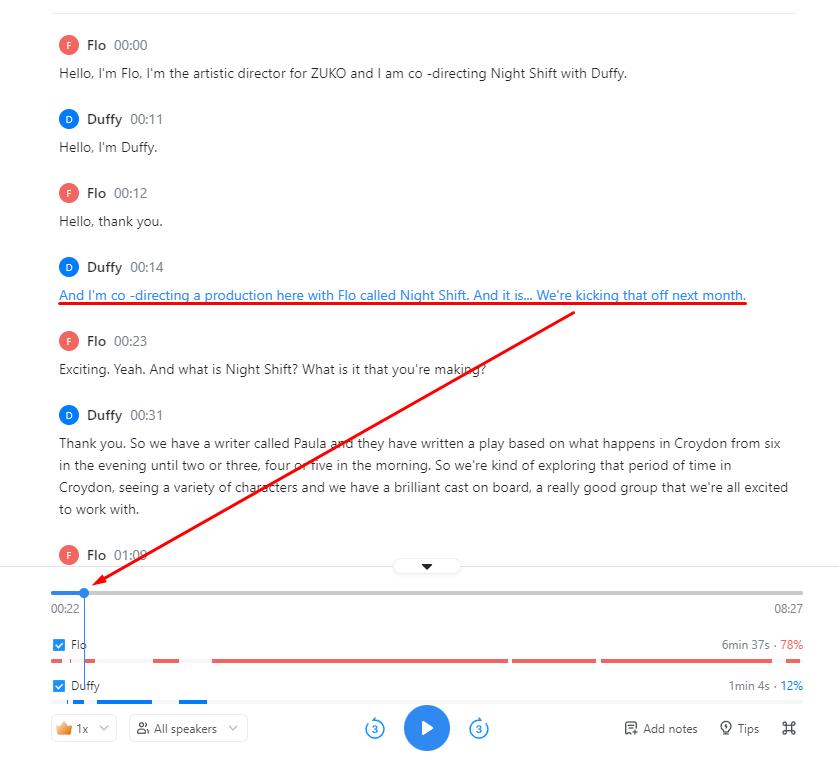

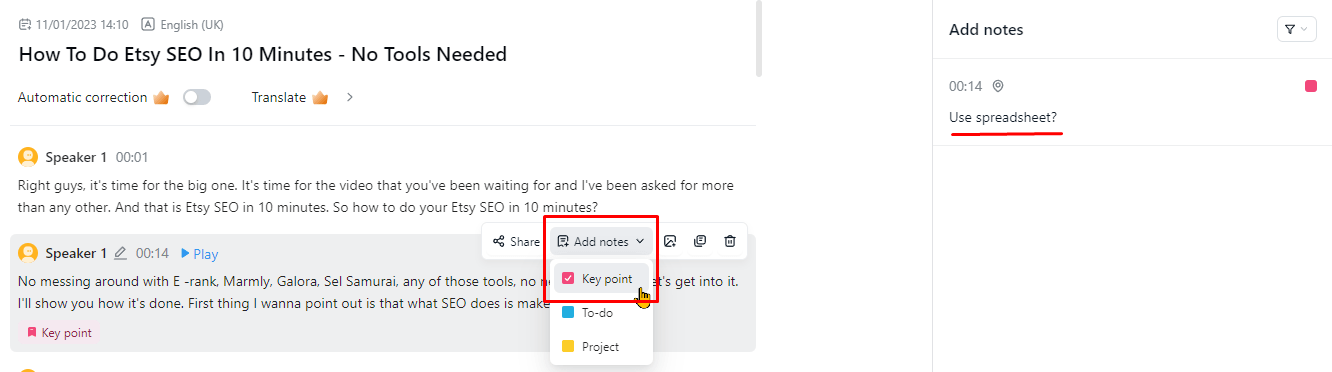

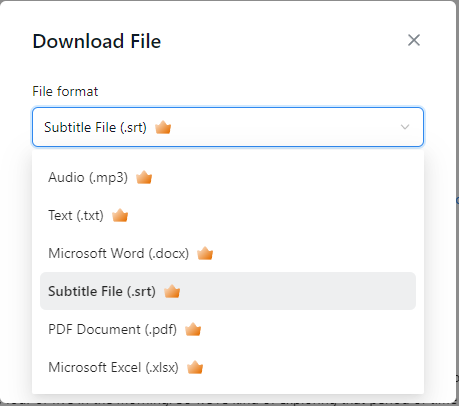

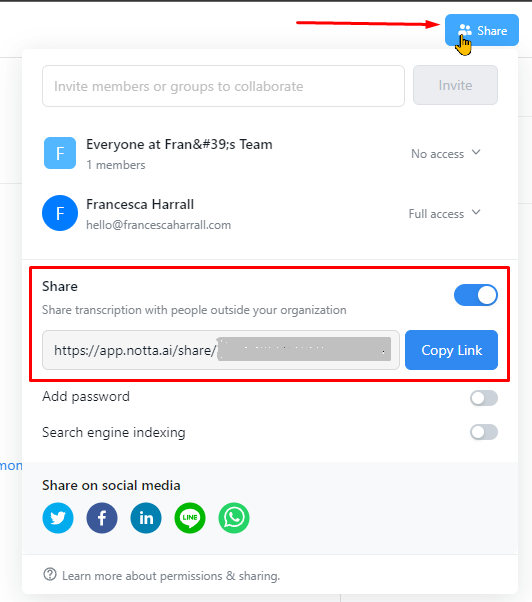

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

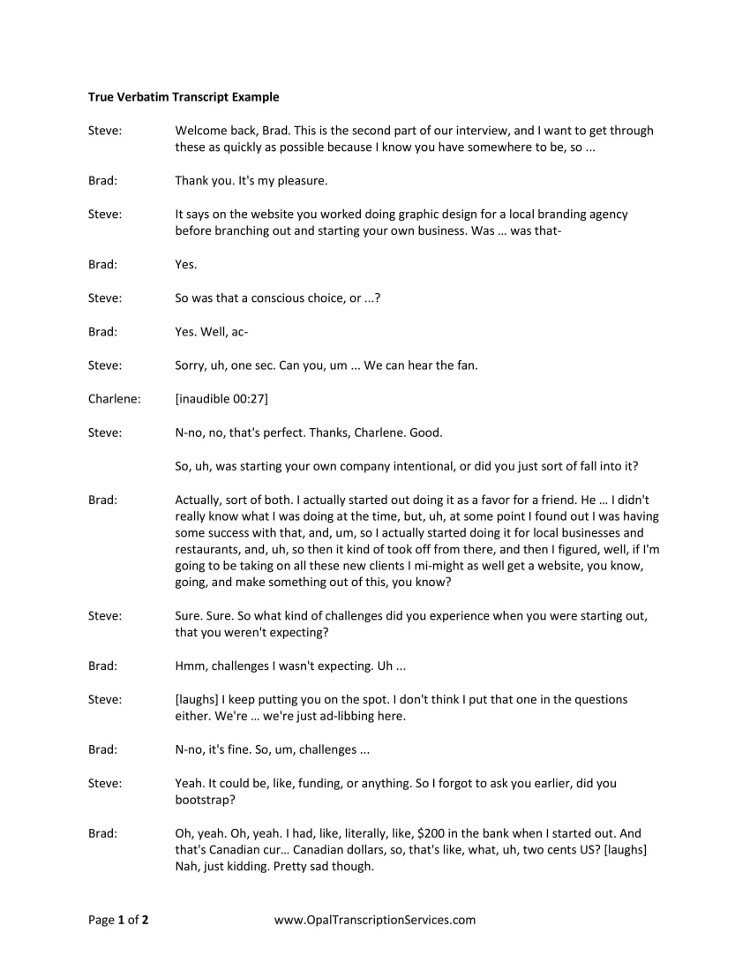

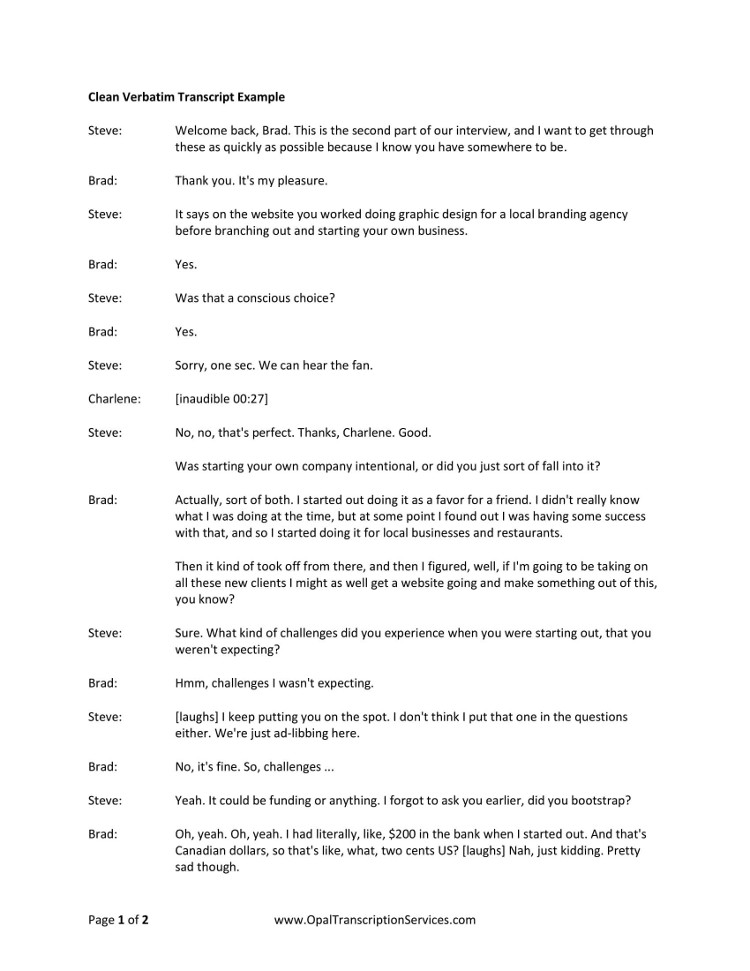

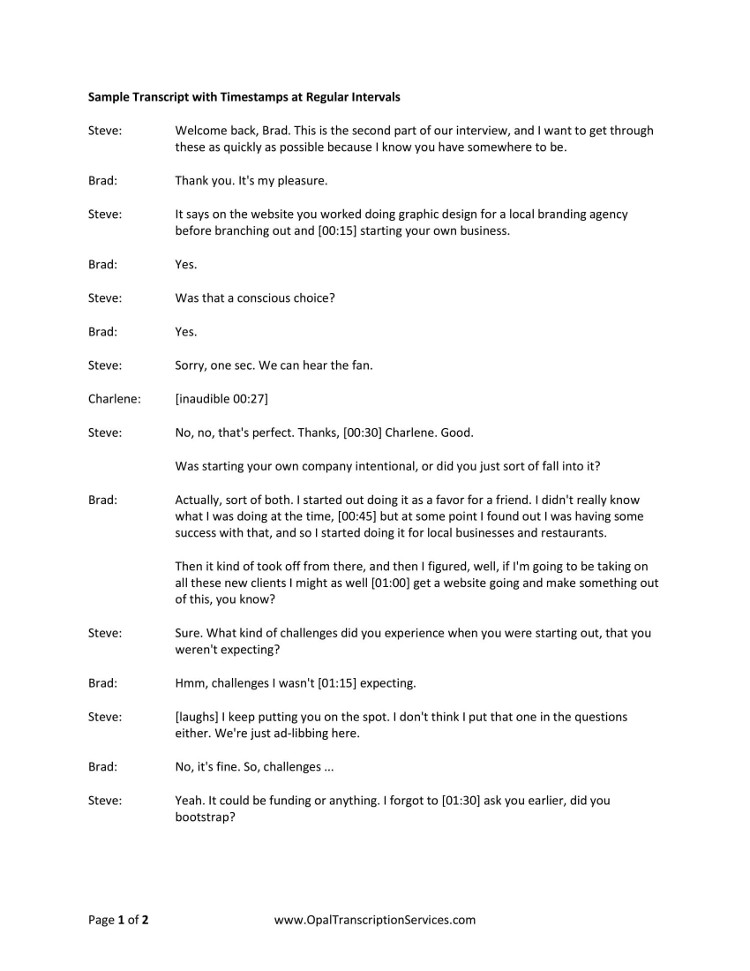

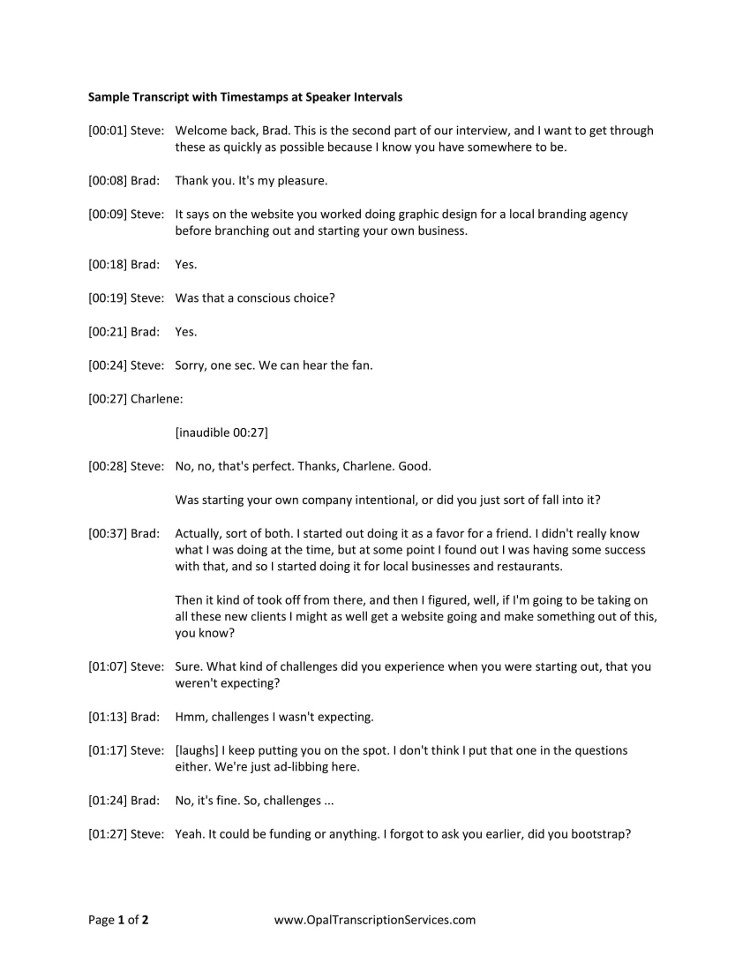

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Qualitative Data Coding 101

How to code qualitative data, the smart way (with examples).

By: Jenna Crosley (PhD) | Reviewed by:Dr Eunice Rautenbach | December 2020

As we’ve discussed previously , qualitative research makes use of non-numerical data – for example, words, phrases or even images and video. To analyse this kind of data, the first dragon you’ll need to slay is qualitative data coding (or just “coding” if you want to sound cool). But what exactly is coding and how do you do it?

Overview: Qualitative Data Coding

In this post, we’ll explain qualitative data coding in simple terms. Specifically, we’ll dig into:

- What exactly qualitative data coding is

- What different types of coding exist

- How to code qualitative data (the process)

- Moving from coding to qualitative analysis

- Tips and tricks for quality data coding

What is qualitative data coding?

Let’s start by understanding what a code is. At the simplest level, a code is a label that describes the content of a piece of text. For example, in the sentence:

“Pigeons attacked me and stole my sandwich.”

You could use “pigeons” as a code. This code simply describes that the sentence involves pigeons.

So, building onto this, qualitative data coding is the process of creating and assigning codes to categorise data extracts. You’ll then use these codes later down the road to derive themes and patterns for your qualitative analysis (for example, thematic analysis ). Coding and analysis can take place simultaneously, but it’s important to note that coding does not necessarily involve identifying themes (depending on which textbook you’re reading, of course). Instead, it generally refers to the process of labelling and grouping similar types of data to make generating themes and analysing the data more manageable.

Makes sense? Great. But why should you bother with coding at all? Why not just look for themes from the outset? Well, coding is a way of making sure your data is valid . In other words, it helps ensure that your analysis is undertaken systematically and that other researchers can review it (in the world of research, we call this transparency). In other words, good coding is the foundation of high-quality analysis.

What are the different types of coding?

Now that we’ve got a plain-language definition of coding on the table, the next step is to understand what overarching types of coding exist – in other words, coding approaches . Let’s start with the two main approaches, inductive and deductive .

With deductive coding, you, as the researcher, begin with a set of pre-established codes and apply them to your data set (for example, a set of interview transcripts). Inductive coding on the other hand, works in reverse, as you create the set of codes based on the data itself – in other words, the codes emerge from the data. Let’s take a closer look at both.

Deductive coding 101

With deductive coding, we make use of pre-established codes, which are developed before you interact with the present data. This usually involves drawing up a set of codes based on a research question or previous research . You could also use a code set from the codebook of a previous study.

For example, if you were studying the eating habits of college students, you might have a research question along the lines of

“What foods do college students eat the most?”

As a result of this research question, you might develop a code set that includes codes such as “sushi”, “pizza”, and “burgers”.

Deductive coding allows you to approach your analysis with a very tightly focused lens and quickly identify relevant data . Of course, the downside is that you could miss out on some very valuable insights as a result of this tight, predetermined focus.

Inductive coding 101

But what about inductive coding? As we touched on earlier, this type of coding involves jumping right into the data and then developing the codes based on what you find within the data.

For example, if you were to analyse a set of open-ended interviews , you wouldn’t necessarily know which direction the conversation would flow. If a conversation begins with a discussion of cats, it may go on to include other animals too, and so you’d add these codes as you progress with your analysis. Simply put, with inductive coding, you “go with the flow” of the data.

Inductive coding is great when you’re researching something that isn’t yet well understood because the coding derived from the data helps you explore the subject. Therefore, this type of coding is usually used when researchers want to investigate new ideas or concepts , or when they want to create new theories.

A little bit of both… hybrid coding approaches

If you’ve got a set of codes you’ve derived from a research topic, literature review or a previous study (i.e. a deductive approach), but you still don’t have a rich enough set to capture the depth of your qualitative data, you can combine deductive and inductive methods – this is called a hybrid coding approach.

To adopt a hybrid approach, you’ll begin your analysis with a set of a priori codes (deductive) and then add new codes (inductive) as you work your way through the data. Essentially, the hybrid coding approach provides the best of both worlds, which is why it’s pretty common to see this in research.

Need a helping hand?

How to code qualitative data

Now that we’ve looked at the main approaches to coding, the next question you’re probably asking is “how do I actually do it?”. Let’s take a look at the coding process , step by step.

Both inductive and deductive methods of coding typically occur in two stages: initial coding and line by line coding .

In the initial coding stage, the objective is to get a general overview of the data by reading through and understanding it. If you’re using an inductive approach, this is also where you’ll develop an initial set of codes. Then, in the second stage (line by line coding), you’ll delve deeper into the data and (re)organise it according to (potentially new) codes.

Step 1 – Initial coding

The first step of the coding process is to identify the essence of the text and code it accordingly. While there are various qualitative analysis software packages available, you can just as easily code textual data using Microsoft Word’s “comments” feature.

Let’s take a look at a practical example of coding. Assume you had the following interview data from two interviewees:

What pets do you have?

I have an alpaca and three dogs.

Only one alpaca? They can die of loneliness if they don’t have a friend.

I didn’t know that! I’ll just have to get five more.

I have twenty-three bunnies. I initially only had two, I’m not sure what happened.

In the initial stage of coding, you could assign the code of “pets” or “animals”. These are just initial, fairly broad codes that you can (and will) develop and refine later. In the initial stage, broad, rough codes are fine – they’re just a starting point which you will build onto in the second stage.

How to decide which codes to use

But how exactly do you decide what codes to use when there are many ways to read and interpret any given sentence? Well, there are a few different approaches you can adopt. The main approaches to initial coding include:

- In vivo coding

Process coding

- Open coding

Descriptive coding

Structural coding.

- Value coding

Let’s take a look at each of these:

In vivo coding

When you use in vivo coding, you make use of a participants’ own words , rather than your interpretation of the data. In other words, you use direct quotes from participants as your codes. By doing this, you’ll avoid trying to infer meaning, rather staying as close to the original phrases and words as possible.

In vivo coding is particularly useful when your data are derived from participants who speak different languages or come from different cultures. In these cases, it’s often difficult to accurately infer meaning due to linguistic or cultural differences.

For example, English speakers typically view the future as in front of them and the past as behind them. However, this isn’t the same in all cultures. Speakers of Aymara view the past as in front of them and the future as behind them. Why? Because the future is unknown, so it must be out of sight (or behind us). They know what happened in the past, so their perspective is that it’s positioned in front of them, where they can “see” it.

In a scenario like this one, it’s not possible to derive the reason for viewing the past as in front and the future as behind without knowing the Aymara culture’s perception of time. Therefore, in vivo coding is particularly useful, as it avoids interpretation errors.

Next up, there’s process coding , which makes use of action-based codes . Action-based codes are codes that indicate a movement or procedure. These actions are often indicated by gerunds (words ending in “-ing”) – for example, running, jumping or singing.

Process coding is useful as it allows you to code parts of data that aren’t necessarily spoken, but that are still imperative to understanding the meaning of the texts.

An example here would be if a participant were to say something like, “I have no idea where she is”. A sentence like this can be interpreted in many different ways depending on the context and movements of the participant. The participant could shrug their shoulders, which would indicate that they genuinely don’t know where the girl is; however, they could also wink, showing that they do actually know where the girl is.

Simply put, process coding is useful as it allows you to, in a concise manner, identify the main occurrences in a set of data and provide a dynamic account of events. For example, you may have action codes such as, “describing a panda”, “singing a song about bananas”, or “arguing with a relative”.

Descriptive coding aims to summarise extracts by using a single word or noun that encapsulates the general idea of the data. These words will typically describe the data in a highly condensed manner, which allows the researcher to quickly refer to the content.

Descriptive coding is very useful when dealing with data that appear in forms other than traditional text – i.e. video clips, sound recordings or images. For example, a descriptive code could be “food” when coding a video clip that involves a group of people discussing what they ate throughout the day, or “cooking” when coding an image showing the steps of a recipe.

Structural coding involves labelling and describing specific structural attributes of the data. Generally, it includes coding according to answers to the questions of “ who ”, “ what ”, “ where ”, and “ how ”, rather than the actual topics expressed in the data. This type of coding is useful when you want to access segments of data quickly, and it can help tremendously when you’re dealing with large data sets.

For example, if you were coding a collection of theses or dissertations (which would be quite a large data set), structural coding could be useful as you could code according to different sections within each of these documents – i.e. according to the standard dissertation structure . What-centric labels such as “hypothesis”, “literature review”, and “methodology” would help you to efficiently refer to sections and navigate without having to work through sections of data all over again.

Structural coding is also useful for data from open-ended surveys. This data may initially be difficult to code as they lack the set structure of other forms of data (such as an interview with a strict set of questions to be answered). In this case, it would useful to code sections of data that answer certain questions such as “who?”, “what?”, “where?” and “how?”.

Let’s take a look at a practical example. If we were to send out a survey asking people about their dogs, we may end up with a (highly condensed) response such as the following:

Bella is my best friend. When I’m at home I like to sit on the floor with her and roll her ball across the carpet for her to fetch and bring back to me. I love my dog.

In this set, we could code Bella as “who”, dog as “what”, home and floor as “where”, and roll her ball as “how”.

Values coding

Finally, values coding involves coding that relates to the participant’s worldviews . Typically, this type of coding focuses on excerpts that reflect the values, attitudes, and beliefs of the participants. Values coding is therefore very useful for research exploring cultural values and intrapersonal and experiences and actions.

To recap, the aim of initial coding is to understand and familiarise yourself with your data , to develop an initial code set (if you’re taking an inductive approach) and to take the first shot at coding your data . The coding approaches above allow you to arrange your data so that it’s easier to navigate during the next stage, line by line coding (we’ll get to this soon).

While these approaches can all be used individually, it’s important to remember that it’s possible, and potentially beneficial, to combine them . For example, when conducting initial coding with interviews, you could begin by using structural coding to indicate who speaks when. Then, as a next step, you could apply descriptive coding so that you can navigate to, and between, conversation topics easily.

Step 2 – Line by line coding

Once you’ve got an overall idea of our data, are comfortable navigating it and have applied some initial codes, you can move on to line by line coding. Line by line coding is pretty much exactly what it sounds like – reviewing your data, line by line, digging deeper and assigning additional codes to each line.

With line-by-line coding, the objective is to pay close attention to your data to add detail to your codes. For example, if you have a discussion of beverages and you previously just coded this as “beverages”, you could now go deeper and code more specifically, such as “coffee”, “tea”, and “orange juice”. The aim here is to scratch below the surface. This is the time to get detailed and specific so as to capture as much richness from the data as possible.

In the line-by-line coding process, it’s useful to code everything in your data, even if you don’t think you’re going to use it (you may just end up needing it!). As you go through this process, your coding will become more thorough and detailed, and you’ll have a much better understanding of your data as a result of this, which will be incredibly valuable in the analysis phase.

Moving from coding to analysis

Once you’ve completed your initial coding and line by line coding, the next step is to start your analysis . Of course, the coding process itself will get you in “analysis mode” and you’ll probably already have some insights and ideas as a result of it, so you should always keep notes of your thoughts as you work through the coding.

When it comes to qualitative data analysis, there are many different types of analyses (we discuss some of the most popular ones here ) and the type of analysis you adopt will depend heavily on your research aims, objectives and questions . Therefore, we’re not going to go down that rabbit hole here, but we’ll cover the important first steps that build the bridge from qualitative data coding to qualitative analysis.

When starting to think about your analysis, it’s useful to ask yourself the following questions to get the wheels turning:

- What actions are shown in the data?

- What are the aims of these interactions and excerpts? What are the participants potentially trying to achieve?

- How do participants interpret what is happening, and how do they speak about it? What does their language reveal?

- What are the assumptions made by the participants?

- What are the participants doing? What is going on?

- Why do I want to learn about this? What am I trying to find out?

- Why did I include this particular excerpt? What does it represent and how?

Code categorisation

Categorisation is simply the process of reviewing everything you’ve coded and then creating code categories that can be used to guide your future analysis. In other words, it’s about creating categories for your code set. Let’s take a look at a practical example.

If you were discussing different types of animals, your initial codes may be “dogs”, “llamas”, and “lions”. In the process of categorisation, you could label (categorise) these three animals as “mammals”, whereas you could categorise “flies”, “crickets”, and “beetles” as “insects”. By creating these code categories, you will be making your data more organised, as well as enriching it so that you can see new connections between different groups of codes.

Theme identification

From the coding and categorisation processes, you’ll naturally start noticing themes. Therefore, the logical next step is to identify and clearly articulate the themes in your data set. When you determine themes, you’ll take what you’ve learned from the coding and categorisation and group it all together to develop themes. This is the part of the coding process where you’ll try to draw meaning from your data, and start to produce a narrative . The nature of this narrative depends on your research aims and objectives, as well as your research questions (sounds familiar?) and the qualitative data analysis method you’ve chosen, so keep these factors front of mind as you scan for themes.

Tips & tricks for quality coding

Before we wrap up, let’s quickly look at some general advice, tips and suggestions to ensure your qualitative data coding is top-notch.

- Before you begin coding, plan out the steps you will take and the coding approach and technique(s) you will follow to avoid inconsistencies.

- When adopting deductive coding, it’s useful to use a codebook from the start of the coding process. This will keep your work organised and will ensure that you don’t forget any of your codes.

- Whether you’re adopting an inductive or deductive approach, keep track of the meanings of your codes and remember to revisit these as you go along.

- Avoid using synonyms for codes that are similar, if not the same. This will allow you to have a more uniform and accurate coded dataset and will also help you to not get overwhelmed by your data.

- While coding, make sure that you remind yourself of your aims and coding method. This will help you to avoid directional drift , which happens when coding is not kept consistent.

- If you are working in a team, make sure that everyone has been trained and understands how codes need to be assigned.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

31 Comments

I appreciated the valuable information provided to accomplish the various stages of the inductive and inductive coding process. However, I would have been extremely satisfied to be appraised of the SPECIFIC STEPS to follow for: 1. Deductive coding related to the phenomenon and its features to generate the codes, categories, and themes. 2. Inductive coding related to using (a) Initial (b) Axial, and (c) Thematic procedures using transcribe data from the research questions

Thank you so much for this. Very clear and simplified discussion about qualitative data coding.

This is what I want and the way I wanted it. Thank you very much.

All of the information’s are valuable and helpful. Thank for you giving helpful information’s. Can do some article about alternative methods for continue researches during the pandemics. It is more beneficial for those struggling to continue their researchers.

Thank you for your information on coding qualitative data, this is a very important point to be known, really thank you very much.

Very useful article. Clear, articulate and easy to understand. Thanks

This is very useful. You have simplified it the way I wanted it to be! Thanks

Thank you so very much for explaining, this is quite helpful!

hello, great article! well written and easy to understand. Can you provide some of the sources in this article used for further reading purposes?

You guys are doing a great job out there . I will not realize how many students you help through your articles and post on a daily basis. I have benefited a lot from your work. this is remarkable.

Wonderful one thank you so much.

Hello, I am doing qualitative research, please assist with example of coding format.

This is an invaluable website! Thank you so very much!

Well explained and easy to follow the presentation. A big thumbs up to you. Greatly appreciate the effort 👏👏👏👏

Thank you for this clear article with examples

Thank you for the detailed explanation. I appreciate your great effort. Congrats!

Ahhhhhhhhhh! You just killed me with your explanation. Crystal clear. Two Cheers!

D0 you have primary references that was used when creating this? If so, can you share them?

Being a complete novice to the field of qualitative data analysis, your indepth analysis of the process of thematic analysis has given me better insight. Thank you so much.

Excellent summary

Thank you so much for your precise and very helpful information about coding in qualitative data.

Thanks a lot to this helpful information. You cleared the fog in my brain.

Glad to hear that!

This has been very helpful. I am excited and grateful.

I still don’t understand the coding and categorizing of qualitative research, please give an example on my research base on the state of government education infrastructure environment in PNG

Wahho, this is amazing and very educational to have come across this site.. from a little search to a wide discovery of knowledge.

Thanks I really appreciate this.

Thank you so much! Very grateful.

This was truly helpful. I have been so lost, and this simplified the process for me.

Just at the right time when I needed to distinguish between inductive and

deductive data analysis of my Focus group discussion results very helpful

Very useful across disciplines and at all levels. Thanks…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers

Student resources, three sample interview transcripts.

The following three transcripts have been provided to help you test your coding skills. Please note these will open in a new window.

Interview Transcript: Digestive Disorders – Brenda

Interview transcript – a teacher’s observations of child oppression, interview transcript: digestive disorders – sam.

The following interview with Brenda [pseudonym] was conducted in April 2013 by Cody Goulder, a graduate student researching people with digestive disorders. Brenda is 25 years old and the transcription is as verbatim as possible.

As a coding and analysis exercise, review the transcript several times to become acquainted with the contents. Make jottings about passages that strike you and pre-code your initial work. Then separate the extended interview transcript into stanzas. Determine the most appropriate coding method(s) for the transcript to help examine the general research questions:

- What are the experiences of people with digestive disorders?

- How do people with digestive disorders cope with them?

Also consider comparing or combining the analysis of this transcript with Sam, the other case interview on digestive disorders.

B: Bowel disorders, it is what it is.

I: How old were you when you first started to realize you were having problems with your digestion?

B: I was, uh, 21 and a half, to be exact, yeah.

I: And do you suffer from celiac or, how would you define your discomfort?

B: My colonoscopy says no celiac and not inflammatory bowel disease. My blood marker test says I have inflammatory bowel disease. I would label myself definitely gluten intolerant.

I: And for the record, can you describe what that means? Gluten intolerance? As you would describe it.

B: Gluten intolerance means that you, your body just does not digest or break down or really absorb gluten. And that is a protein that is found in wheat. I would also say that I don’t handle processed wheat well either. Um, and the symptoms are across the board. For me personally, um, I get, I’ll get joint pains, exhaustion, um, and I just feel incredibly full. After four or five bites, if I’m having, say, pasta or something where it’s just, after four or five bites, I can’t eat anymore, feel nauseous. That’s actually where the symptoms really first started.

I: Was there anything else beyond that? Say migraine headaches or …

B: Headaches. I have, and it’s gotten a lot better, I had, um, pretty bad hormonal acne, is what they would call it. Went across the board trying to treat it. I tried creams and antibiotics, retin-As, all that stuff. When I started to cut out gluten and wheats, my skin cleared up the best it’s ever been. I even went on Accutane and, I was on Accutane for five months and that is exactly when my symptoms would appear. I’ve been completely healthy my entire life.

I: Do you think there is a connection between …

B: Yes. I, well, studies have shown that if you possibly have Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis and you go on Accutane, there is research coming out that, it can set those diseases off. Um, and I just, I can’t, I think that’s what happened to me because of, like I said, I was completely healthy and then one day I’m having bowel issues and medications.

I: You said you’ve seen doctors, medical doctors, what was that process like of getting tested? What was the response?

B: Well, I went to, when I first got sick, I went to my internal medicine doctor and he’s like, “I don’t know if it’s acid reflux or what, so I’m gonna do a blood test on you.” And he did a blood panel, that’s when he said, “OK, according to these markers you have IBD, go to a gastrologist.” And, I went to one that was recommended, um, and she was just like, “OK, I wanna scope you.” I told her about all these symptoms and when I told her I’d been on Accutane, she kind of made a look like, “Oh, OK.” And then I have a family history, unfortunately, with inflammatory bowel disease. Both of my younger sisters have ulcerative colitis. I have an uncle who is deceased who had ulcerative colitis, and two or three second cousins that have ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s.

I: Can you describe what ulcerative colitis is, as you would describe it?

B: Um, it’s just your intestines not really absorbing the proper nutrients and inflammation, um, and that can be where, um, in any part of your gut. All the way to, Crohn’s can even burn your esophagus and mouth, all the way down through the rest of your body. It’s pretty intense. I was the healthy one. I didn’t have asthma or, not like my little sisters. The hell they went through in middle school with getting sick, I never had that.

I: Would you be willing to talk a little more about that?

B: So, my first sister got sick right around middle school. Her symptoms were, any time she’d eat, she immediately would have to go to the bathroom, instant diarrhea. She’d break out in a sweat. She’d get [ unable to transcribe ], which is a kind of skin lesion, which is, we talked to the dermatologist and, but until you treat really the underlying problem, you don’t know what’s going on. Um, what else did she have? And just going from doctor to doctor. Um, they did a scope and there was a little inflammation that they did find. Um, but they still were very hesitant of saying, “Yes, you have ulcerative colitis” because she wasn’t on, your typical textbook case. I found that really hard for doctors. If it’s not black and white, they …

I: We’ve discussed in other interviews, before this, the fear of using labels in …

B: They’re terrified. I mean, I went through several doctors and then finally, um, I think kinda, and going through puberty, I and, while my sisters were going through puberty, it was really hard. With all the hormones and changing, It just kinda, I think, throws a lot of things off. And then my sister, she’s what would you call remission, but it’s never really going away. You’ll always still have it, but she been in remission for a while now. Um, found the right doctor and he didn’t label her until he started treating her.

I: So it was sort of a trial by fire?

B: Yeah, we’d kind of tell them, “Hey, can we try this? It’s not getting better.” And then my youngest sister, right around the same time, about sixth grade, she got sick as well. Different symptoms. Um, she didn’t have, she had ulcerative colitis. But, there can come blood when you go to the bathroom. And she went in, was severely sick, she went to the hospital. And filled up the little cup they have, completely, with blood. And when they went in to scope, they couldn’t find anything. But she had the blood. She had the joint ache. She has the rash. She’s trying to eat as much as she could, but her belly would distend. And they wanted to send my sister to the psych unit. They thought it was a mental thing and we’re like, “No, she’s filling up the cup.” Like, really? And it was just their reaction because they couldn’t figure out why because the gold standard in diagnosing these things is the colonoscopy. But it’s so hard with these diseases to find it.

I: Why do you think there seems to be a reluctance or a unwillingness in wanting to just get right to the point?

B: I’m not really sure. I don’t, I don’t know. I don’t know if they’re taught that in med school that, you know, that it’s not black and white. And we have found also that, when you are in a hospital setting, you don’t see the same doctor. You have a doctor for a week and then, you know, in all honesty, they weren’t all on the same page. They had their own egos and their own agendas. My sister was in there 21 days. Still, we were finally like, “This is enough. It’s not a psych problem, discharge her now.” And she was still bleeding, two weeks later, she was anemic. We ended up, by chance, being able to get into a different doctor at a different practice who would treat her as if. She was in remission for about three years, she’s out of it now, but she’s got good doctors. She’s still trying to figure out how to beat this beast.

I: Are both your sisters, and you as well, on prescription medication?

B: Um, yes. My little sister Tammy now, I think because she’s been in remission is on like a, something for acid reflux. My younger sister, she’s not on any medication. And my one sister, yes, but I don’t remember what she’s on.

I: And, none of these symptoms have been shown in your parents?

B: My mom, yeah. I remember growing up and her having bowel issues, yeah. And, it’s all on my mom’s side. My dad’s side doesn’t have any bowel issues. This gluten intolerance thing, I didn’t really understand it until I was taking a class with a friend and I was just telling her, “God, I really don’t like.” They labeled me as having GERD and put me on severe, pretty intense medication. I just don’t like the fact I have to take this medication.

I: What is GERD?

B: It’s similar to the acid reflux disease. So, a lot of it is by diet. Little things can set it off.

I: Before all this, what was your favorite food?

B: I loved pizza and burgers.

I: Would you say you ate a pretty balanced diet? Not loading up on pasta …

B: No, but it’s funny ‘cause when I was sick, that’s all I wanted, you know? That sounded really good to eat bread and crackers.

I: Is that because it was a comfort basis?

B: No, um, I think people with that, like sugars and complex stuff, especially like all the sugar that’s really not good for you, it’s addicting, you know? The longer you are away from it, it’s easier to stay away. Have a little and it’s like I gotta have more. It’s difficult.

I: When you started to cut out gluten and bad sugars, what was the response?

B: From like a friend?

I: Yeah. Were you a partier?