- Previous Article

- Next Article

Case Presentation

Case study: a patient with diabetes and weight-loss surgery.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

Sue Cummings; Case Study: A Patient With Diabetes and Weight-Loss Surgery. Diabetes Spectr 1 July 2007; 20 (3): 173–176. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.20.3.173

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

A.W. is a 65-year-old man with type 2 diabetes who was referred by his primary care physician to the weight center for an evaluation of his obesity and recommendations for treatment options, including weight-loss surgery. The weight center has a team of obesity specialists, including an internist, a registered dietitian (RD), and a psychologist, who perform a comprehensive initial evaluation and make recommendations for obesity treatment. A.W. presented to the weight center team reluctant to consider weight-loss surgery;he is a radiologist and has seen patients who have had complications from bariatric surgery.

Pertinent medical history. A.W.'s current medications include 30 and 70 units of NPH insulin before breakfast and before or after dinner, respectively, 850 mg of metformin twice daily, atorvastatin,lisinopril, nifedipine, allopurinol, aspirin, and an over-the-counter vitamin B 12 supplement. He has sleep apnea but is not using his continuous positive airway pressure machine. He reports that his morning blood glucose levels are 100–130 mg/dl, his hemoglobin A 1c (A1C) level is 6.1%, which is within normal limits, his triglyceride level is 201 mg/dl, and serum insulin is 19 ulU/ml. He weighs 343 lb and is 72 inches tall, giving him a BMI of 46.6 kg/m 2 .

Weight history. A.W. developed obesity as a child and reports having gained weight every decade. He is at his highest adult weight with no indication that medications or medical complications contributed to his obesity. His family history is positive for obesity; his father and one sister are also obese.

Dieting history. A.W. has participated in both commercial and medical weight-loss programs but has regained any weight lost within months of discontinuing the programs. He has seen an RD for weight loss in the past and has also participated in a hospital-based, dietitian-led, group weight-loss program in which he lost some weight but regained it all. He has tried many self-directed diets, but has had no significant weight losses with these.

Food intake. A.W. eats three meals a day. Dinner, his largest meal of the day, is at 7:30 p . m . He usually does not plan a mid-afternoon snack but will eat food if it is left over from work meetings. He also eats an evening snack to avoid hypoglycemia. He reports eating in restaurants two or three times a week but says his fast-food consumption is limited to an occasional breakfast sandwich from Dunkin'Donuts. His alcohol intake consists of only an occasional glass of wine. He reports binge eating (described as eating an entire large package of cookies or a large amount of food at work lunches even if he is not hungry) about once a month, and says it is triggered by stress.

Social history. Recently divorced, A.W. is feeling depressed about his life situation and has financial problems and stressful changes occurring at work. He recently started living with his girlfriend, who does all of the cooking and grocery shopping for their household.

Motivation for weight loss. A.W. says he is concerned about his health and wants to get his life back under control. His girlfriend, who is thin and a healthy eater, has also been concerned about his weight. His primary care physician has been encouraging him to explore weight-loss surgery; he is now willing to learn more about surgical options. He says that if the weight center team's primary recommendation is for weight-loss surgery,he will consider it.

Does A.W. have contraindications to weight-loss surgery, and, if not, does he meet the criteria for weight-loss surgery?

What type of weight-loss surgery would be best for A.W.?

Roles of the obesity specialist team members

The role of the physician as an obesity specialist is to identify and evaluate obesity-related comorbidities and to exclude medically treatable causes of obesity. The physician assesses any need to adjust medications and,if possible, determines if the patient is on a weight-promoting medication that may be switched to a less weight-promoting medication.

The psychologist evaluates weight-loss surgery candidates for a multitude of factors, including the impact of weight on functioning, current psychological symptoms and stressors, psychosocial history, eating disorders,patients' treatment preferences and expectations, motivation, interpersonal consequences of weight loss, and issues of adherence to medical therapies.

The RD conducts a nutritional evaluation, which incorporates anthropometric measurements including height (every 5 years), weight (using standardized techniques and involving scales in a private location that can measure patients who weigh > 350 lb), neck circumference (a screening tool for sleep apnea), and waist circumference for patients with a BMI < 35 kg/m 2 . Other assessments include family weight history,environmental influences, eating patterns, and the nutritional quality of the diet. A thorough weight and dieting history is taken, including age of onset of overweight or obesity, highest and lowest adult weight, usual weight, types of diets and/or previous weight-loss medications, and the amount of weight lost and regained with each attempt. 1

Importance of type of obesity

Childhood- and adolescent-onset obesity lead to hyperplasic obesity (large numbers of fat cells); patients presenting with hyperplasic and hypertrophic obesity (large-sized fat cells), as opposed to patients with hypertrophic obesity alone, are less likely to be able to maintain a BMI < 25 kg/m 2 , because fat cells can only be shrunk and not eliminated. This is true even after weight-loss surgery and may contribute to the variability in weight loss outcomes after weight loss surgery. Less than 5% of patients lose 100% of their excess body weight. 2 , 3

Criteria and contraindications for weight-loss surgery

In 1998, the “Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation,and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report” 4 recommended that weight-loss surgery be considered an option for carefully selected patients:

with clinically severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m 2 or ≥ 35 kg/m 2 with comorbid conditions);

when less invasive methods of weight loss have failed; and

the patient is at high risk for obesity-associated morbidity or mortality.

Contraindications for weight-loss surgery include end-stage lung disease,unstable cardiovascular disease, multi-organ failure, gastric verices,uncontrolled psychiatric disorders, ongoing substance abuse, and noncompliance with current regimens.

A.W. had no contraindications for surgery and met the criteria for surgery,with a BMI of 46.6 kg/m 2 . He had made numerous previous attempts at weight loss, and he had obesity-related comorbidities, including diabetes,sleep apnea, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia.

Types of procedures

The roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery is the most common weight-loss procedure performed in the United States. However, the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) procedure has been gaining popularity among surgeons. Both procedures are restrictive, with no malabsorption of macronutrients. There is,however, malabsorption of micronutrients with the RYGB resulting from the bypassing of a major portion of the stomach and duodenum. The bypassed portion of the stomach produces the intrinsic factor needed for the absorption of vitamin B 12 . The duodenum is where many of the fat-soluble vitamins, B vitamins, calcium, and iron are absorbed. Patients undergoing RYGB must agree to take daily vitamin and mineral supplementation and to have yearly monitoring of nutritional status for life.

Weight loss after RYGB and LAGB

The goal of weight-loss surgery is to achieve and maintain a healthier body weight. Mean weight loss 2 years after gastric bypass is ∼ 65% of excess weight loss (EWL), which is defined as the number of pounds lost divided by the pounds of overweight before surgery. 5 When reviewing studies of weight-loss procedures, it is important to know whether EWL or total body weight loss is being measured. EWL is about double the percentage of total body weight loss; a 65% EWL represents about 32% loss of total body weight.

Most of the weight loss occurs in the first 6 months after surgery, with a continuation of gradual loss throughout the first 18–24 months. Many patients will regain 10–15% of the lost weight; a small number of patients regain a significant portion of their lost weight. 6 Data on long-term weight maintenance after surgery indicate that if weight loss has been maintained for 5 years, there is a > 95% likelihood that the patient will keep the weight off over the long term.

The mean percentage of EWL for LAGB is 47.5%. 3 Although the LAGB is considered a lower-risk surgery, initial weight loss and health benefits from the procedure are also lower than those of RYGB.

Weight-loss surgery and diabetes

After gastric bypass surgery, there is evidence of resolution of type 2 diabetes in some individuals, which has led some to suggest that surgery is a cure. 7 Two published studies by Schauer et al. 8 and Sugarman et al. 9 reported resolution in 83 and 86% of patients, respectively. Sjoström et al. 10 published 2-and 10-year data from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study of 4,047 morbidly obese subjects who underwent bariatric surgery and matched control subjects. At the end of 2 years, the incidence of diabetes in subjects who underwent bariatric surgery was 1.0%, compared to 8.0% in the control subjects. At 10 years, the incidence was 7.0 and 24.0%, respectively.

The resolution of diabetes often occurs before marked weight loss is achieved, often days after the surgery. Resolution of diabetes is more prevalent after gastric bypass than after gastric banding (83.7% for gastric bypass and 47.9% for gastric banding). 5 The LAGB requires adjusting (filling the band through a port placed under the skin),usually five to six times per year. Meta-analysis of available data shows slower weight loss and less improvement in comorbidities including diabetes compared to RYGB. 5

A.W. had diabetes; therefore, the weight center team recommended the RYGB procedure.

Case study follow-up

A.W. had strong medical indications for surgery and met all other criteria outlined in current guidelines. 4 He attended a surgical orientation session that described his surgical options,reviewed the procedures (including their risks and possible complications),and provided him the opportunity to ask questions. This orientation was led by an RD, with surgeons and post–weight-loss surgical patients available to answer questions. After attending the orientation, A.W. felt better informed about the surgery and motivated to pursue this treatment.

The weight center evaluation team referred him to the surgeon for surgical evaluation. The surgeon agreed with the recommendation for RYGB surgery, and presurgical appointments and the surgery date were set. The surgeon encouraged A.W. to try to lose weight before surgery. 11

Immediately post-surgery. The surgery went well. A.W.'s blood glucose levels on postoperative day 2 were 156 mg/dl at 9:15 a . m . and 147 mg/dl at 11:15 a . m . He was discharged from the hospital on that day on no diabetes medications and encouraged to follow a Stage II clear and full liquid diet( Table 1 ). 12

Diet Stages After RYBG Surgery

On postoperative day 10, he returned to the weight center. He reported consuming 16 oz of Lactaid milk mixed with sugar-free Carnation Instant Breakfast and 8 oz of light yogurt, spread out over three to six meals per day. In addition, he was consuming 24 oz per day of clear liquids containing no sugar, calories, or carbonation. A.W.'s diet was advanced to Stage III,which included soft foods consisting primarily of protein sources (diced,ground, moist meat, fish, or poultry; beans; and/or dairy) and well-cooked vegetables. He also attended a nutrition group every 3 weeks, at which the RD assisted him in advancing his diet.

Two months post-surgery. A.W. was recovering well; he denied nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation. He was eating without difficulty and reported feeling no hunger. His fasting and pre-dinner blood glucose levels were consistently < 120 mg/dl, with no diabetes medications. He continued on allopurinol and atorvastatin and was taking a chewable daily multivitamin and chewable calcium citrate (1,000 mg/day in divided doses) with vitamin D (400 units). His weight was 293 lb, down 50 lb since the surgery. A pathology report from a liver biopsy showed mild to moderate steatatosis without hepatitis.

One year post-surgery. A.W.'s weight was 265 lb, down 78 lb since the surgery, and his weight loss had significantly slowed, as expected. He was no longer taking nifedipine or lisinipril but was restarted at 5 mg daily to achieve a systolic blood pressure < 120 mmHg. His atorvastatin was stopped because his blood lipid levels were appropriate (total cholesterol 117 mg/dl, triglycerides 77 mg/dl, HDL cholesterol 55 mg/dl, and LDL cholesterol 47 mg/dl). His gastroesophageal reflux disease has been resolved, and he continued on allopurinol for gout but had had no flare-ups since surgery. Knee pain caused by osteoarthritis was well controlled without anti-inflammatory medications, and he had no evidence of sleep apnea. Annual medical follow-up and nutritional laboratory measurements will include electrolytes, glucose,A1C, albumin, total protein, complete blood count, ferritin, iron, total iron binding capacity, calcium, parathyroid hormone, vitamin D, magnesium, vitamins B 1 and B 12 , and folate, as well as thyroid, liver, and kidney function tests and lipid measurements.

In summary, A.W. significantly benefited from undergoing RYBP surgery. By 1 year post-surgery, his BMI had decreased from 46.6 to 35.8 kg/m 2 ,and he continues to lose weight at a rate of ∼ 2 lb per month. His diabetes, sleep apnea, and hypercholesterolemia were resolved and he was able to control his blood pressure with one medication.

Clinical Pearls

Individuals considering weight loss surgery require rigorous presurgical evaluation, education, and preparation, as well as a comprehensive long-term postoperative program of surgical, medical, nutritional, and psychological follow-up.

Individuals with diabetes should consider the RYBP procedure because the data on resolution or significant improvement of diabetes after this procedure are very strong, and such improvements occur immediately. Resolution in or improvement of diabetes with the LAGB procedure are more likely to occur only after excess weight has been lost.

Individuals with diabetes undergoing weight loss surgery should be closely monitored; an inpatient protocol should be written regarding insulin regimens and sliding-scale use of insulin if needed. Patients should be educated regarding self-monitoring of blood glucose and the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia. They should be given instructions on stopping or reducing medications as blood glucose levels normalize.

Patient undergoing RYGB must have lifetime multivitamin supplementation,including vitamins B 1 , B 12 , and D, biotin, and iron, as well as a calcium citrate supplement containing vitamin D (1,000–1,500 mg calcium per day). Nutritional laboratory measurements should be conducted yearly and deficiencies repleted as indicated for the duration of the patient's life.

Sue Cummings, MS, RD, LDN, is the clinical programs coordinator at the MGH Weight Center in Boston, Mass.

Email alerts

- Online ISSN 1944-7353

- Print ISSN 1040-9165

- Diabetes Care

- Clinical Diabetes

- Diabetes Spectrum

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes

- Scientific Sessions Abstracts

- BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care

- ShopDiabetes.org

- ADA Professional Books

Clinical Compendia

- Clinical Compendia Home

- Latest News

- DiabetesPro SmartBrief

- Special Collections

- DiabetesPro®

- Diabetes Food Hub™

- Insulin Affordability

- Know Diabetes By Heart™

- About the ADA

- Journal Policies

- For Reviewers

- Advertising in ADA Journals

- Reprints and Permission for Reuse

- Copyright Notice/Public Access Policy

- ADA Professional Membership

- ADA Member Directory

- Diabetes.org

- X (Twitter)

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

- © Copyright American Diabetes Association

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 27 January 2020

Epidemiology and Population Health

Evidence from big data in obesity research: international case studies

- Emma Wilkins 1 ,

- Ariadni Aravani 1 ,

- Amy Downing 1 ,

- Adam Drewnowski 2 ,

- Claire Griffiths 3 ,

- Stephen Zwolinsky 3 ,

- Mark Birkin 4 ,

- Seraphim Alvanides 5 , 6 &

- Michelle A. Morris ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9325-619X 1

International Journal of Obesity volume 44 , pages 1028–1040 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

952 Accesses

4 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Risk factors

- Signs and symptoms

Background/objective

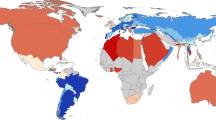

Obesity is thought to be the product of over 100 different factors, interacting as a complex system over multiple levels. Understanding the drivers of obesity requires considerable data, which are challenging, costly and time-consuming to collect through traditional means. Use of ‘big data’ presents a potential solution to this challenge. Big data is defined by Delphi consensus as: always digital , has a large sample size, and a large volume or variety or velocity of variables that require additional computing power (Vogel et al. Int J Obes. 2019). ‘Additional computing power’ introduces the concept of big data analytics. The aim of this paper is to showcase international research case studies presented during a seminar series held by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Strategic Network for Obesity in the UK. These are intended to provide an in-depth view of how big data can be used in obesity research, and the specific benefits, limitations and challenges encountered.

Methods and results

Three case studies are presented. The first investigated the influence of the built environment on physical activity. It used spatial data on green spaces and exercise facilities alongside individual-level data on physical activity and swipe card entry to leisure centres, collected as part of a local authority exercise class initiative. The second used a variety of linked electronic health datasets to investigate associations between obesity surgery and the risk of developing cancer. The third used data on tax parcel values alongside data from the Seattle Obesity Study to investigate sociodemographic determinants of obesity in Seattle.

Conclusions

The case studies demonstrated how big data could be used to augment traditional data to capture a broader range of variables in the obesity system. They also showed that big data can present improvements over traditional data in relation to size, coverage, temporality, and objectivity of measures. However, the case studies also encountered challenges or limitations; particularly in relation to hidden/unforeseen biases and lack of contextual information. Overall, despite challenges, big data presents a relatively untapped resource that shows promise in helping to understand drivers of obesity.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 20,95 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Non-traditional data sources in obesity research: a systematic review of their use in the study of obesogenic environments

Julia Mariel Wirtz Baker, Sonia Alejandra Pou, … Laura Rosana Aballay

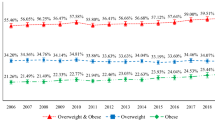

Trends in the prevalence of adult overweight and obesity in Australia, and its association with geographic remoteness

Syed Afroz Keramat, Khorshed Alam, … Rubayyat Hashmi

Best practices for analyzing large-scale health data from wearables and smartphone apps

Jennifer L. Hicks, Tim Althoff, … Scott L. Delp

Davison KK, Birch LL. Childhood overweight: a contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obes Rev. 2001;2:159–71.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Egger G, Swinburn B. An “ecological” approach to the obesity pandemic. BMJ. 1997;315:477–80.

Harrison K, Bost KK, McBride BA, Donovan SM, Grigsby-Toussaint DS, Kim J, et al. Toward a developmental conceptualization of contributors to overweight and obesity in childhood: the six-Cs model. Child Dev Perspect. 2011;5:50–8.

Article Google Scholar

Butland B, Jebb S, Kopelman P, McPherson K, Thomas S, Mardell J et al. Foresight. Tackling obesities: future choices—project report. Government Office for Science; 2007.

Rutter HR, Bes-Rastrollo M, de Henauw S, Lahti-Koski M, Lehtinen-Jacks S, Mullerova D, et al. Balancing upstream and downstream measures to tackle the obesity epidemic: a position statement from the European association for the study of obesity. Obes Facts. 2017;10:61–3.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mittelstadt BD, Floridi L. The ethics of big data: current and foreseeable issues in biomedical contexts. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22:303–41.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kaisler S, Armour F, Espinosa JA, Money W. Big data: issues and challenges moving forward. In: Proceedings of the 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Association for Computing Machinery Digital Library; 2013. p. 995–1004.

Herland M, Khoshgoftaar TM, Wald R. A review of data mining using big data in health informatics. J Big Data. 2014;1: https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-1115-1-2 .

Vogel C, Zwolinsky S, Griffiths C, Hobbs M, Henderson E, Wilkins E. A Delphi study to build consensus on the definition and use of big data in obesity research. Int J Obes. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-018-0313-9 .

Morris M, Birkin M. The ESRC strategic network for obesity: tackling obesity with big data. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1948–50.

Timmins K, Green M, Radley D, Morris M, Pearce J. How has big data contributed to obesity research? A review of the literature. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1951–62.

Monsivais P, Francis O, Lovelace R, Chang M, Strachan E, Burgoine T. Data visualisation to support obesity policy: case studies of data tools for planning and transport policy in the UK. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1977–86.

Morris M, Wilkins E, Timmins K, Bryant M, Birkin M, Griffiths C. Can big data solve a big problem? Reporting the obesity data landscape in line with the Foresight obesity system map. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1963–76.

Vayena E, Salathé M, Madoff LC, Brownstein JS. Ethical challenges of big data in public health. PLOS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1003904.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Silver LD, Ng SW, Ryan-Ibarra S, Taillie LS, Induni M, Miles DR, et al. Changes in prices, sales, consumer spending, and beverage consumption one year after a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages in Berkeley, California, US: a before-and-after study. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002283.

Gore RJ, Diallo S, Padilla J. You are what you tweet: connecting the geographic variation in america’s obesity rate to Twitter content. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0133505.

Nguyen QC, Li D, Meng H-W, Kath S, Nsoesie E, Li F, et al. Building a national neighborhood dataset from geotagged Twitter data for indicators of happiness, diet, and physical activity. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016;2:e158.

Hirsch JA, James P, Robinson JR, Eastman KM, Conley KD, Evenson KR, et al. Using MapMyFitness to place physical activity into neighborhood context. Front Public Health. 2014;2:1–9.

Althoff T, Hicks JL, King AC, Delp SL, Leskovec J. Large-scale physical activity data reveal worldwide activity inequality. Nature. 2017;547:336–9.

Kerr NL. HARKing: hypothesizing after the results are known. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 1998;2:196–217.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380:219–29.

Bennett JE, Li G, Foreman K, Best N, Kontis V, Pearson C, et al. The future of life expectancy and life expectancy inequalities in England and Wales: Bayesian spatiotemporal forecasting. Lancet. 2015;386:163–70.

World Health Organisation. Report of the Commission on ending childhood obesity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. Atlanta, GA, U.S.: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009.

Local Government Association. Building the foundations: tackling obesity through planning and development. London, UK: Local Government Association; 2016.

Burgoine T, Alvanides S, Lake AA. Creating ‘obesogenic realities’; Do our methodological choices make a difference when measuring the food environment? Int J Health Geogr. 2013;12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-12-33 .

Wilkins E, Morris M, Radley D, Griffiths C. Methods of measuring associations between the Retail Food Environment and weight status: Importance of classifications and metrics. SSM Popul Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100404 .

Bardou M, Barkun AN, Martel M. Obesity and colorectal cancer. Gut. 2013;62:933–47.

Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104–17.

Derogar M, Hull MA, Kant P, Östlund M, Lu Y, Lagergren J. Increased risk of colorectal cancer after obesity surgery. Ann Surg. 2013;258:983–8.

Kant P, Hull MA. Excess body weight and obesity—the link with gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:224–38.

Östlund MP, Lu Y, Lagergren J. Risk of obesity-related cancer after obesity surgery in a population-based cohort study. Ann Surg. 2010;252:972–6.

Sainsbury A, Goodlad RA, Perry SL, Pollard SG, Robins GG, Hull MA. Increased colorectal epithelial cell proliferation and crypt fission associated with obesity and roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17:1401–10.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Aravani A, Downing A, Thomas JD, Lagergren J, Morris EJA, Hull MA. Obesity surgery and risk of colorectal and other obesity-related cancers: an English population-based cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;53:99–104.

Openshaw S. The modifiable areal unit problem. In: Concepts and techniques in modern geography. Norwich: Geo Books; 1984. p. 1–41.

Kwan M-P. The uncertain geographic context problem. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2012;102:958–68.

Di Zhu X, Yang Y, Liu X. The importance of housing to the accumulation of household net wealth. Harvard, USA: Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University; 2003.

Rehm CD, Moudon AV, Hurvitz PM, Drewnowski A. Residential property values are associated with obesity among women in King County, WA, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:491–5.

Drewnowski A, Buszkiewicz J, Aggarwal A. Soda, salad, and socioeconomic status: findings from the Seattle Obesity Study (SOS). SSM Popul Health. 2019;7:e100339.

Birkin M, Morris MA, Birkin TM, Lovelace R. Using census data in microsimulation modelling. In: Stillwell J, Duke-Williams O, editors. The Routledge handbook of census resources, methods and applications. 1st ed. Routledge: IJO publication; 2018.

Jiao J, Drewnowski A, Moudon AV, Aggarwal A, Oppert J-M, Charreire H, et al. The impact of area residential property values on self-rated health: a cross-sectional comparative study of Seattle and Paris. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:68–74.

Nguyen DM, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterol Clinics. 2010;39:1–7.

Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2001;55:111–22.

Timperio A, Salmon J, Telford A, Crawford D. Perceptions of local neighbourhood environments and their relationship to childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Obes. 2005;29:170–5.

Roda C, Charreire H, Feuillet T, Mackenbach JD, Compernolle S, Glonti K, et al. Mismatch between perceived and objectively measured environmental obesogenic features in European neighbourhoods. Obes Rev. 2016;17 S1:31–41.

Drewnowski A, Arterburn D, Zane J, Aggarwal A, Gupta S, Hurvitz PM, et al. The Moving to Health (M2H) approach to natural experiment research: a paradigm shift for studies on built environment and health. SSM Popul Health. 2019;7:100345.

Bourassa SC, Cantoni E, Hoesli M. Predicting house prices with spatial dependence a comparison of alternative methods. J Real Estate Res. 2010;32:139–60.

Google Scholar

Wilkins EL, Radley D, Morris MA, Griffiths C. Examining the validity and utility of two secondary sources of food environment data against street audits in England. Nutr J. 2017;16:1–13.

Nevalainen J, Erkkola M, Saarijarvi H, Nappila T, Fogelholm M. Large-scale loyalty card data in health research. Digit Health. 2018;4:2055207618816898.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Aiello L, Schifanello R, Quercia D, Del Prete L. Large-scale and high-resolution analysis of food purchases and health outcomes. EPJ Data Sci. 2019;8:14.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95.

Zwolinsky S, McKenna J, Pringle A, Widdop P, Griffiths C, Mellis M, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior clustering: segmentation to optimize active lifestyles. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:921–8.

Bauman A, Ainsworth BE, Sallis JF, Hagströmer M, Craig CL, Bull FC, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of sitting: a 20-country comparison using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:228–35.

Guerin PB, Diiriye RO, Corrigan C, Guerin B. Physical activity programs for refugee somali women: working out in a new country. Women & Health. 2003;38:83–99.

Pope L, Harvey J. The efficacy of incentives to motivate continued fitness-center attendance in college first-year students: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Health. 2014;62:81–90.

Cetateanu A, Jones A. Understanding the relationship between food environments, deprivation and childhood overweight and obesity: evidence from a cross sectional England-wide study. Health Place. 2014;27:68–76.

Harrison F, Burgoine T, Corder K, van Sluijs EM, Jones A. How well do modelled routes to school record the environments children are exposed to? A cross-sectional comparison of GIS-modelled and GPS-measured routes to school. Int J Health Geogr. 2014;13:5.

Ells LJ, Macknight N, Wilkinson JR. Obesity surgery in England: an examination of the health episode statistics 1996–2005. Obes Surg. 2007;17:400–5.

Nielsen JDJ, Laverty AA, Millett C, Mainous AG, Majeed A, Saxena S. Rising obesity-related hospital admissions among children and young people in England: National time trends study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65764.

Smittenaar C, Petersen K, Stewart K, Moitt N. Cancer incidence and mortality projections in the UK until 2035. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1147–55.

Wallington M, Saxon EB, Bomb M, Smittenaar R, Wickenden M, McPhail S, et al. 30-day mortality after systemic anticancer treatment for breast and lung cancer in England: a population-based, observational study. The Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1203–16.

Smolina K, Wright FL, Rayner M, Goldacre MJ. Determinants of the decline in mortality from acute myocardial infarction in England between 2002 and 2010: Linked national database study. BMJ. 2012;344:d8059.

Hanratty B, Lowson E, Grande G, Payne S, Addington-Hall J, Valtorta N, et al. Transitions at the end of life for older adults–patient, carer and professional perspectives: A mixed-methods study. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2014. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr02170 .

Aggarwal A, Monsivais P, Cook AJ, Drewnowski A. Does diet cost mediate the relation between socioeconomic position and diet quality? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65:1059–66.

Drewnowski A, Aggarwal A, Tang W, Moudon AV. Residential property values predict prevalent obesity but do not predict 1-year weight change. Obesity. 2015;23:671–6.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The ESRC Strategic Network for Obesity was funded via ESRC grant number ES/N00941X/1. The authors would like to thank all of the network investigators ( https://www.cdrc.ac.uk/research/obesity/investigators/ ) and members ( https://www.cdrc.ac.uk/research/obesity/network-members/ ) for their participation in network meetings and discussion which contributed to the development of this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Leeds Institute for Data Analytics and School of Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

Emma Wilkins, Ariadni Aravani, Amy Downing & Michelle A. Morris

Center for Public Health Nutrition, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Adam Drewnowski

School of Sport, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, UK

Claire Griffiths & Stephen Zwolinsky

Leeds Institute for Data Analytics and School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

- Mark Birkin

Engineering and Environment, Northumbria University, Newcastle, UK

Seraphim Alvanides

GESIS—Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Cologne, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michelle A. Morris .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wilkins, E., Aravani, A., Downing, A. et al. Evidence from big data in obesity research: international case studies. Int J Obes 44 , 1028–1040 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-0532-8

Download citation

Received : 23 May 2019

Revised : 20 December 2019

Accepted : 07 January 2020

Published : 27 January 2020

Issue Date : May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-020-0532-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

- Julia Mariel Wirtz Baker

- Sonia Alejandra Pou

- Laura Rosana Aballay

International Journal of Obesity (2023)

Creating a long-term future for big data in obesity research

- Emma Wilkins

- Michelle A. Morris

International Journal of Obesity (2019)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 21 June 2021

The lived experience of people with obesity: study protocol for a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies

- Emma Farrell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7780-9428 1 ,

- Marta Bustillo 2 ,

- Carel W. le Roux 3 ,

- Joe Nadglowski 4 ,

- Eva Hollmann 1 &

- Deirdre McGillicuddy 1

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 181 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

6046 Accesses

9 Altmetric

Metrics details

Obesity is a prevalent, complex, progressive and relapsing chronic disease characterised by abnormal or excessive body fat that impairs health and quality of life. It affects more than 650 million adults worldwide and is associated with a range of health complications. Qualitative research plays a key role in understanding patient experiences and the factors that facilitate or hinder the effectiveness of health interventions. This review aims to systematically locate, assess and synthesise qualitative studies in order to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the lived experience of people with obesity.

This is a protocol for a qualitative evidence synthesis of the lived experience of people with obesity. A defined search strategy will be employed in conducting a comprehensive literature search of the following databases: PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, PsycArticles and Dimensions (from 2011 onwards). Qualitative studies focusing on the lived experience of adults with obesity (BMI >30) will be included. Two reviewers will independently screen all citations, abstracts and full-text articles and abstract data. The quality of included studies will be appraised using the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) criteria. Thematic synthesis will be conducted on all of the included studies. Confidence in the review findings will be assessed using GRADE CERQual.

The findings from this synthesis will be used to inform the EU Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI)-funded SOPHIA (Stratification of Obesity Phenotypes to Optimize Future Obesity Therapy) study. The objective of SOPHIA is to optimise future obesity treatment and stimulate a new narrative, understanding and vocabulary around obesity as a set of complex and chronic diseases. The findings will also be useful to health care providers and policy makers who seek to understand the experience of those with obesity.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42020214560 .

Peer Review reports

Obesity is a complex chronic disease in which abnormal or excess body fat (adiposity) impairs health and quality of life, increases the risk of long-term medical complications and reduces lifespan [ 1 ]. Operationally defined in epidemiological and population studies as a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 30, obesity affects more than 650 million adults worldwide [ 2 ]. Its prevalence has almost tripled between 1975 and 2016, and, globally, there are now more people with obesity than people classified as underweight [ 2 ].

Obesity is caused by the complex interplay of multiple genetic, metabolic, behavioural and environmental factors, with the latter thought to be the proximate factor which enabled the substantial rise in the prevalence of obesity in recent decades [ 3 , 4 ]. This increased prevalence has resulted in obesity becoming a major public health issue with a resulting growth in health care and economic costs [ 5 , 6 ]. At a population level, health complications from excess body fat increase as BMI increases [ 7 ]. At the individual level, health complications occur due to a variety of factors such as distribution of adiposity, environment, genetic, biologic and socioeconomic factors [ 8 ]. These health complications include type 2 diabetes [ 9 ], gallbladder disease [ 10 ] and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [ 11 ]. Excess body fat can also place an individual at increased cardiometabolic and cancer risk [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] with an estimated 20% of all cancers attributed to obesity [ 15 ].

Although first recognised as a disease by the American Medical Association in 2013 [ 16 ], the dominant cultural narrative continues to present obesity as a failure of willpower. People with obesity are positioned as personally responsible for their weight. This, combined with the moralisation of health behaviours and the widespread association between thinness, self-control and success, has resulted in those who fail to live up to this cultural ideal being subject to weight bias, stigma and discrimination [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Weight bias, stigma and discrimination have been found to contribute, independent of weight or BMI, to increased morbidity or mortality [ 20 ].

Thomas et al. [ 21 ] highlighted, more than a decade ago, the need to rethink how we approach obesity so as not to perpetuate damaging stereotypes at a societal level. Obesity research then, as now, largely focused on measurable outcomes and quantifiable terms such as body mass index [ 22 , 23 ]. Qualitative research approaches play a key role in understanding patient experiences, how factors facilitate or hinder the effectiveness of interventions and how the processes of interventions are perceived and implemented by users [ 24 ]. Studies adopting qualitative approaches have been shown to deliver a greater depth of understanding of complex and socially mediated diseases such as obesity [ 25 ]. In spite of an increasing recognition of the integral role of patient experience in health research [ 25 , 26 ], the voices of patients remain largely underrepresented in obesity research [ 27 , 28 ].

Systematic reviews and syntheses of qualitative studies are recognised as a useful contribution to evidence and policy development [ 29 ]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this will be the first systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies focusing on the lived experience of people with obesity. While systematic reviews have been carried out on patient experiences of treatments such as behavioural management [ 30 ] and bariatric surgery [ 31 ], this review and synthesis will be the first to focus on the experience of living with obesity rather than patient experiences of particular treatments or interventions. This focus represents a growing awareness that ‘patients have a specific expertise and knowledge derived from lived experience’ and that understanding lived experience can help ‘make healthcare both effective and more efficient’ [ 32 ].

This paper outlines a protocol for the systematic review of qualitative studies based on the lived experience of people with obesity. The findings of this review will be synthesised in order to develop an overview of the lived experience of patients with obesity. It will look, in particular, at patient concerns around the risks of obesity and their aspirations for response to obesity treatment.

The review protocol has been registered within the PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42020214560) and is being reported in accordance with the reporting guidance provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement [ 33 , 34 ] (see checklist in Additional file 1 ).

Information sources and search strategy

The primary source of literature will be a structured search of the following electronic databases (from January 2011 onwards—to encompass the increase in research focused on patient experience observed over the last 10 years): PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, PsycArticles and Dimensions. There is no methodological agreement as to how many search terms or databases out to be searched as part of a ‘good’ qualitative synthesis (Toye et al. [ 35 ]). However, the breadth and depth of the search terms, the inclusion of clinical and personal language and the variety within the selected databases, which cover areas such as medicine, nursing, psychology and sociology, will position this qualitative synthesis as comprehensive. Grey literature will not be included in this study as its purpose is to conduct a comprehensive review of peer-reviewed primary research. The study’s patient advisory board will be consulted at each stage of the review process, and content experts and authors who are prolific in the field will be contacted. The literature searches will be designed and conducted by the review team which includes an experienced university librarian (MB) following the methodological guidance of chapter two of the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [ 36 ]. The search will include a broad range of terms and keywords related to obesity and qualitative research. A full draft search strategy for PubMed is provided in Additional file 2 .

Eligibility criteria

Studies based on primary data generated with adults with obesity (operationally defined as BMI >30) and focusing on their lived experience will be eligible for inclusion in this synthesis (Table 1 ). The context can include any country and all three levels of care provision (primary, secondary and tertiary). Only peer-reviewed, English language, articles will be included. Studies adopting a qualitative design, such as phenomenology, grounded theory or ethnography, and employing qualitative methods of data collection and analysis, such as interviews, focus groups, life histories and thematic analysis, will be included. Publications with a specific focus, for example, patient’s experience of bariatric surgery, will be included, as well as studies adopting a more general view of the experience of obesity.

Screening and study selection process

Search results will be imported to Endnote X9, and duplicate entries will be removed. Covidence [ 38 ] will be used to screen references with two reviewers (EF and EH) removing entries that are clearly unrelated to the research question. Titles and abstracts will then be independently screened by two reviewers (EF and EH) according to the inclusion criteria (Table 1 ). Any disagreements will be resolved through a third reviewer (DMcG). This layer of screening will determine which publications will be eligible for independent full-text review by two reviewers (EF and EH) with disagreements again being resolved by a third reviewer (DMcG).

Data extraction

Data will be extracted independently by two researchers (EF and EH) and combined in table format using the following headings: author, year, title, country, research aims, participant characteristics, method of data collection, method of data analysis, author conclusions and qualitative themes. In the case of insufficient or unclear information in a potentially eligible article, the authors will be contacted by email to obtain or confirm data, and a timeframe of 3 weeks to reply will be offered before article exclusion.

Quality appraisal of included studies

This qualitative synthesis will facilitate the development of a conceptual understanding of obesity and will be used to inform the development of policy and practice. As such, it is important that the studies included are themselves of suitable quality. The methodological quality of all included studies will be assessed using the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) checklist, and studies that are deemed of insufficient quality will be excluded. The CASP checklist for qualitative research comprises ten questions that cover three main issues: Are the results of the study under review valid? What are the results? Will the results help locally? Two reviewers (EF and EH) will independently evaluate each study using the checklist with a third and fourth reviewer (DMcG and MB) available for consultation in the event of disagreement.

Data synthesis

The data generated through the systematic review outlined above will be synthesised using thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden [ 39 ]. Thematic synthesis enables researchers to stay ‘close’ to the data of primary studies, synthesise them in a transparent way and produce new concepts and hypotheses. This inductive approach is useful for drawing inference based on common themes from studies with different designs and perspectives. Thematic synthesis is made up of a three-step process. Step one consists of line by line coding of the findings of primary studies. The second step involves organising these ‘free codes’ into related areas to construct ‘descriptive’ themes. In step three, the descriptive themes that emerged will be iteratively examined and compared to ‘go beyond’ the descriptive themes and the content of the initial studies. This step will generate analytical themes that will provide new insights related to the topic under review.

Data will be coded using NVivo 12. In order to increase the confirmability of the analysis, studies will be reviewed independently by two reviewers (EF and EH) following the three-step process outlined above. This process will be overseen by a third reviewer (DMcG). In order to increase the credibility of the findings, an overview of the results will be brought to a panel of patient representatives for discussion. Direct quotations from participants in the primary studies will be italicised and indented to distinguish them from author interpretations.

Assessment of confidence in the review findings

Confidence in the evidence generated as a result of this qualitative synthesis will be assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (GRADE CERQual) [ 40 ] approach. Four components contribute to the assessment of confidence in the evidence: methodological limitations, relevance, coherence and adequacy of data. The methodological limitations of included studies will be examined using the CASP tool. Relevance assesses the degree to which the evidence from the primary studies applies to the synthesis question while coherence assesses how well the findings are supported by the primary studies. Adequacy of data assesses how much data supports a finding and how rich this data is. Confidence in the evidence will be independently assessed by two reviewers (EF and EH), graded as high, moderate or low, and discussed collectively amongst the research team.

Reflexivity

For the purposes of transparency and reflexivity, it will be important to consider the findings of the qualitative synthesis and how these are reached, in the context of researchers’ worldviews and experiences (Larkin et al, 2019). Authors have backgrounds in health science (EF and EH), education (DMcG and EF), nursing (EH), sociology (DMcG), philosophy (EF) and information science (MB). Prior to conducting the qualitative synthesis, the authors will examine and discuss their preconceptions and beliefs surrounding the subject under study and consider the relevance of these preconceptions during each stage of analysis.

Dissemination of findings

Findings from the qualitative synthesis will be disseminated through publications in peer-reviewed journals, a comprehensive and in-depth project report and presentation at peer-reviewed academic conferences (such as EASO) within the field of obesity research. It is also envisaged that the qualitative synthesis will contribute to the shared value analysis to be undertaken with key stakeholders (including patients, clinicians, payers, policy makers, regulators and industry) within the broader study which seeks to create a new narrative around obesity diagnosis and treatment by foregrounding patient experiences and voice(s). This synthesis will be disseminated to the 29 project partners through oral presentations at management board meetings and at the general assembly. It will also be presented as an educational resource for clinicians to contribute to an improved understanding of patient experience of living with obesity.

Obesity is a complex chronic disease which increases the risk of long-term medical complications and a reduced quality of life. It affects a significant proportion of the world’s population and is a major public health concern. Obesity is the result of a complex interplay of multiple factors including genetic, metabolic, behavioural and environmental factors. In spite of this complexity, obesity is often construed in simple terms as a failure of willpower. People with obesity are subject to weight bias, stigma and discrimination which in themselves result in increased risk of mobility or mortality. Research in the area of obesity has tended towards measurable outcomes and quantitative variables that fail to capture the complexity associated with the experience of obesity. A need to rethink how we approach obesity has been identified—one that represents the voices and experiences of people living with obesity. This paper outlines a protocol for the systematic review of available literature on the lived experience of people with obesity and the synthesis of these findings in order to develop an understanding of patient experiences, their concerns regarding the risks associated with obesity and their aspirations for response to obesity treatment. Its main strengths will be the breadth of its search remit—focusing on the experiences of people with obesity rather than their experience of a particular treatment or intervention. It will also involve people living with obesity and its findings disseminated amongst the 29 international partners SOPHIA research consortium, in peer reviewed journals and at academic conferences. Just as the study’s broad remit is its strength, it is also a potential challenge as it is anticipated that searchers will generate many thousands of results owing to the breadth of the search terms. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this will be the first systematic review and synthesis of its kind, and its findings will contribute to shaping the optimisation of future obesity understanding and treatment.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Body mass index

Critical appraisal skills programme

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research

Innovative Medicines Initiative

Medical Subject Headings

Population, phenomenon of interest, context, study type

Stratification of Obesity Phenotypes to Optimize Future Obesity Therapy

Wharton S, Lau DCW, Vallis M, Sharma AM, Biertho L, Campbell-Scherer D, et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. Can Med Assoc J. 2020;192(31):E875–91. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.191707 .

Article Google Scholar

World Health Organisation. Fact sheet: obesity and overweight. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2020.

Google Scholar

Mechanick J, Hurley D, Garvey W. Adiposity-based chronic disease as a new diagnostic term: the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College Of Endocrinology position statement. Endocrine Pract. 2017;23(3):372–8. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP161688.PS .

Garvey W, Mechanick J. Proposal for a scientifically correct and medically actionable disease classification system (ICD) for obesity. Obesity. 2020;28(3):484–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22727 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Biener A, Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The high and rising costs of obesity to the US health care system. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(Suppl 1):6–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3968-8 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Department of Health and Social Care. Healthy lives, healthy people: a call to action on obesity in England. London: Department of Health and Social Care; 2011.

Di Angelantonio E, Bhupathiraju SN, Wormser D, Gao P, Kaptoge S, de Gonzalez AB, et al. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet. 2016;388(10046):776–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30175-1 .

Sharma AM. M, M, M & M: a mnemonic for assessing obesity. Obesity Reviews. 2010;11(11):808–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00766.x .

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Asnawi A, Peeters A, de Courten M, Stoelwinder J. The magnitude of association between overweight and obesity and the risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;89:309-19. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:309–19.

Dagfinn A, Teresa N, Lars JV. Body mass index, abdominal fatness and the risk of gallbladder disease. 2015;30(9):1009.

Longo M, Zatterale F, Naderi J, Parrillo L, Formisano P, Raciti GA, et al. Adipose tissue dysfunction as determinant of obesity-associated metabolic complications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9).

Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, Westfall AO, Allison DB. Years of life lost due to obesity. 2003;289(2):187-193.

Grover SA, Kaouache M, Rempel P, Joseph L, Dawes M, Lau DCW, et al. Years of life lost and healthy life-years lost from diabetes and cardiovascular disease in overweight and obese people: a modelling study. 2015;3(2):114-122.

Ackerman S, Blackburn O, Marchildon F, Cohen P. Insights into the link between obesity and cancer. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6(2):195–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0263-x .

Wolin K, Carson K, Colditz G. Obesity and cancer. Oncol. 2010;15(6):556–65. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285 .

Resolution 420: Recognition of obesity as a disease [press release]. 05/16/13 2013.

Brownell KD. Personal responsibility and control over our bodies: when expectation exceeds reality. 1991;10(5):303-10.

Puhl RM, Latner JD, O'Brien K, Luedicke J, Danielsdottir S, Forhan M. A multinational examination of weight bias: predictors of anti-fat attitudes across four countries. 2015;39(7):1166-1173.

Browne NT. Weight bias, stigmatization, and bullying of obese youth. 2012;7(3):107-15.

Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Weight discrimination and risk of mortality. 2015;26(11):1803-11.

Thomas SL, Hyde J, Karunaratne A, Herbert D, Komesaroff PA. Being “fat” in today’s world: a qualitative study of the lived experiences of people with obesity in Australia. 2008;11(4):321-30.

Ogden K, Barr J, Rossetto G, Mercer J. A “messy ball of wool”: a qualitative study of the dimensions of the lived experience of obesity. 2020;8(1):1-14.

Ueland V, Furnes B, Dysvik E, R¯rtveit K. Living with obesity-existential experiences. 2019;14(1):1-12.

Avenell A, Robertson C, Skea Z, Jacobsen E, Boyers D, Cooper D, et al. Bariatric surgery, lifestyle interventions and orlistat for severe obesity: the REBALANCE mixed-methods systematic review and economic evaluation. 2018;22(68).

The PLoS Medicine Editors. Qualitative research: understanding patients’ needs and experiences. Plos Med. 2007;4(8):1283–4.

Boulton M, Fitzpatrick R. Qualitative methods for assessing health care doi:10.1136/qshc.3.2.107. Qual Health Care. 1994;3:107–13.

Johnstone J, Herredsberg C, Lacy L, Bayles P, Dierking L, Houck A, et al. What I wish my doctor really knew: the voices of patients with obesity. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(2):169–71. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2494 .

Brown I, Thompson J, Tod A, Jones G. Primary care support for tackling obesity: a qualitative study of the perceptions of obese patients. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(530):666–72.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brown I, Gould J. Qualitative studies of obesity: a review of methodology. Health. 2013;5(8A3):69–80.

Garip G, Yardley L. A synthesis of qualitative research on overweight and obese people’s views and experiences of weight management. Clin Obes. 2011;1(2-3):10–126.

Coulman K, MacKichan F, Blazeby J, Owen-Smith A. Patient experiences of outcomes of bariatric surgery: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Obes Rev. 2017;18(5):547–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12518 .

European Patients’ Forum. “Patients’ Perceptions of Quality in Healthcare”: Report of a survey conducted by EPF in 2016 Brussels: European Patients’ Forum; 2017.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 .

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349(jan02 1):g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647 .

Toye F, et al. Meta-ethnography 25 years on: challenges and insights for synthesising a large number of qualitative studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(80).

Lockwood C, Porrit K, Munn Z, Rittenmeyer L, Salmond S, Bjerrum M, et al. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis: JBI; 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-03 .

Methley AM, et al. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of spcificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Res. 2014;14.

Covidence. Cochrane Community; 2020. Available from: https://www.covidence.org .

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 .

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Rashidian A, Wainwright M, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0688-3 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Any amendments made to this protocol when conducting the study will be outlined in PROSPERO and reported in the final manuscript.

This project has received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (JU) under grant agreement No 875534. The JU receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme and EFPIA and T1D Exchange, JDRF and Obesity Action Coalition. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and will not have a role in collection, analysis and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

Emma Farrell, Eva Hollmann & Deirdre McGillicuddy

University College Dublin Library, Dublin, Ireland

Marta Bustillo

Diabetes Complications Research Centre, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

Carel W. le Roux

Obesity Action Coalition, Tampa, USA

Joe Nadglowski

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

EF conceptualised and designed the protocol with input from DMcG and MB. EF drafted the initial manuscript. EF and MB defined the concepts and search items with input from DmcG, CleR and JN. MB and EF designed and executed the search strategy. DMcG, CleR, JN and EH provided critical insights and reviewed and revised the protocol. All authors have approved and contributed to the final written manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Emma Farrell .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:..

PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols) 2015 checklist: recommended items to address in a systematic review protocol*.

Additional file 2: Table 1

. Search PubMed search string.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Farrell, E., Bustillo, M., le Roux, C.W. et al. The lived experience of people with obesity: study protocol for a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Syst Rev 10 , 181 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01706-5

Download citation

Received : 28 October 2020

Accepted : 14 May 2021

Published : 21 June 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01706-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Lived experience

- Patient experience

- Obesity treatment

- Qualitative

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Case Studies

Curricular case studies.

These case studies are intended to showcase real-world competency integration strategies that might inspire leaders in each profession to prioritize obesity education across the continuum of training.

We developed a series of profession-specific case studies to highlight programs and institutions that have demonstrated a commitment to equipping students, trainees, and/or practicing health professionals with the skills and knowledge needed to care competently and compassionately for persons with obesity. The case studies are intended to provide examples of how the Provider Competencies for the Prevention and Management of Obesity can be integrated into the formative training and continuing education of nurses, physicians, physician assistants, dietitians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists, dentists, psychologists, exercise physiologists, public health practitioners, and social workers in the United States.

The case studies were authored by STOP Obesity Alliance staff using information obtained through material reviews and interviews. Case studies were selected to reflect diverse experiences across professions, geographies, institution types, interventional approaches, and care settings. Eligible participants:

- were accredited health professional training programs OR other entities authorized to oversee and/or deliver provider education

- addressed one or more of the Provider Competencies for the Prevention & Management of Obesity

- promoted evidence-based practices consistent with national obesity care guidelines (e.g. USPSTF, TOS, ENDO, AHA, CMS)

Embedding Weight Sensitivity in the Nursing Care Practicum

Villanova University , M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing

FOODS-C: A 3-Year Integrated Obesity Curriculum for Medical Trainees

Touro University – California , College of Osteopathic Medicine

Enhanced Oral Health Training Curriculum to Address Obesity in Early Childhood and Adults

University of Washington , School of Dentistry

Pharmacist-Driven Disease Management: Delivering an On-Campus Weight Management Service

Auburn University , Harrison School of Pharmacy

mHealth Curriculum: Training in Use of Medical and Patient Mobile Apps for Weight Management

University of Texas Southwestern , School of Health Professions

Obesity-Focused Clinical Public Health Summit: Experiential Learning to Improve Community Health

George Washington University , School of Medicine & Health Sciences

Obesity and Health: An Interdisciplinary Undergraduate Minor for Future Health Professionals

Indiana University Bloomington , School of Public Health

Improving Obesity Education Through Policy: Mandated Continuing Education on Nutrition and Obesity

Council of the District of Columbia

Healthy Homes, Healthy Futures: A Home Visitation Curriculum for Pediatric Residents

Children’s National Health System , Department of General & Community Pediatrics

Lifestyle Redesign®: Preparing Trainees to Implement Occupational Therapy Interventions for Obesity

University of Southern California , Division of Occupational Therapy

Childhood obesity treatment: case studies

Resources Policy Dossiers Childhood Obesity Treatment Childhood obesity treatment: case studies

- Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax

- Digital Marketing

- School-based interventions

- Community-level interventions

- Pregnancy & Obesity

- Childhood Obesity Treatment

- Front-of-pack nutrition labelling

- Obesity & COVID-19

- Physical Activity

- Food Systems

- Weight Stigma

Family-Based Interventions in the Prevention and Management of Childhood Overweight and Obesity: An International Review of Best Practices, and a Review of current Irish Interventions

The aim of this review is "to identify current family-based practice internationally for the prevention and treatment of childhood overweight and obesity and to examine current Irish Programmes so that best practice recommendations can be drawn up."

Cost-effectiveness of intensive inpatient treatment for severely obese children and adolescents in the Netherlands; a randomized controlled trials (HELIOS)

This paper presents "the design of a randomized controlled trial comparing the cost-effectiveness of two itnensive one-year inpatient treatments to each other and to usual are for severely obese children and adolescents."

Family-based behavioural treatment of childhood obesity in a UK National Health Service setting: randomized controlled trial

The objective of this randomised controlled trial was "to examine the acceptability and effectiveness of 'family-based behavioural treatment' (FBBT) for childhood obesity in an ethnically and social diverse sample of families in a UK National Health Service (NHS) setting."

Reducing childhood obesity in Poland by effective policies

The purpose of this report was "to faciliate the development of an action plan and implementation of the strategy dimensions around childhood obesity by providing evidence-based policy options adapted to the national context." https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2017-2977-42735-59610

The Malaysian Childhood Obesity Treatment Trial (MASCOT)

The primary aim of the study is "to describe a behavioural family-centred, group-based treatment programme for childhood obesity in Malaysia - the MASCOT."

Process evaluation of an up-scaled community-based child obesity treatment program: NSW Go4Fun®

This paper "describes the up-scaling of Go4Fun in New South Wales and the characteristics of the population it has reached and retained since inception in 2009,including characteristics of children who completed and did not copmlete the programme."

Randomized Controlled Trial of the MEND Program: A Family-Based Community Intervention for Childhood Obesity

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the Mind, Exercise, Nutrition, Do it (MEND) Programme.

Assessing the short-term outcomes of a community-based intervention for overweight and obese children: the MEND 5-7 programme

The aim of this study was "to report outcomes from the UK service level delivery of MEND 5-7."

Effectiveness of a Multi-Component Intervention for Overweight and Obese Children (Nereu Program): A Randomized Controlled Trial

The objective of this study was "to evaluate the effectiveness of the Nereu Program in improving anthropometric parameters, physical activity and sedentary behaviours, and dietary intake."

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents with severe obesity: a prospective five-year Swedish nationwide study (AMOS)

The objective of this study was "to report outcomes over 5 years in adolescents follow Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or conservative treatment in a Swedish nationwide prospective non-randomised controlled study, with an additional matched adult comparison group undergoing RYGB."

Mapping the health system response to childhood obesity in the WHO European Region. An overview and country perspectives

This project aimed "to assess the response of health care delivery systems in 19 countries in the WHO European Region to the childhood obesity epidemic."

An Integrated Clinic-Community Partnership for Child Obesity Treatment: A Randomized Pilot Trial

This study aims “to describe the implementation of an integrated clinic-community partnership for child obesity treatment and [...] to evaluate the effectiveness of integrated treatment on child BMI and health outcomes” in a lower-income area. Enrolled children were between 5 and 11 years of age, over the 95th percentile for BMI, and referred to clinic by their paediatrician.

Adapting Pediatric Obesity Treatment Delivery for Low-Income Families: A Public–Private Partnership

The aim of this study was to “evaluate the feasibility of delivering a paediatric weight management intervention adapted for low-income families.”

Challenges and results of a school-based intervention to manage excess weight among school children in Tunisia 2012-2014

This study intended to “demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of a school-based weight management program based on healthy lifestyle promotion for obese and overweight adolescents in Sousse, Tunisia.”

The Effect of a Multidisciplinary Lifestyle Intervention on Obesity Status, Body Composition, Physical Fitness, and Cardiometabolic Risk Markers in Children and Adolescents with Obesity

The aim of this study was to develop a “moderate-intensity multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention program” to treat obesity in the “real world” and evaluate its effectiveness through anthropometric measures.

The GReat-Child™ Trial: A Quasi-Experimental Intervention on Whole Grains with Healthy Balanced Diet to Manage Childhood Obesity in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Scientists designed the GReat-Child™ trial to determine if increasing whole grain consumption could effectively impact health parameters in Malaysian children.

Impact of readiness to change behaviour on the effects of a multidisciplinary intervention in obese Brazilian children and adolescents

This study examined how the success of a multifaceted obesity treatment was related to a child’s willingness to alter their lifestyle using Stages of Readiness for Behavior Change (SRBC).

Sacbe, a Comprehensive Intervention to Decrease Body Mass Index in Children with Adiposity: A Pilot Study

The aim of this study was to “to achieve a higher percentage of success in lowering the BMI z-score in children with adiposity and their parents through a pilot program "Sacbe" based on HLS, sensitive to the sociocultural context previously explored and with the active participation of parents.”

A Novel Home-Based Intervention for Child and Adolescent Obesity: The Results of the Whānau Pakari Randomized Controlled Trial

The aim of this study was to “report 12‐month outcomes from a multidisciplinary child obesity intervention program, targeting high‐risk groups” in New Zealand.

Systematic reviews

Cost studies

Government guidelines & recommendations

Share this page.

Training & Events

SCOPE E-Learning

We offer the only internationally recognised course on obesity management. Read more here.

Global Obesity Observatory

We offer various statistics, maps and key data around the topic of obesity. You can find all that and more here.

Policy & Advocacy

Our Policy Priorities

We have developed five key areas of policy that are a priority to us. Want to know more? Check them out here!

- Our Members

- Partnerships

- Patient Portal

- Membership Application Form

- Member Benefits

- Finance Committee

- Annual Report and Financials

- Prevalence of Obesity

- Causes of Obesity

- Obesity Classification

- Prevention of Obesity

- Obesity as a disease

- Commercial determinants of obesity

- Childhood Obesity

- Obesity in Universal Health Coverage

- The ROOTS of Obesity

- World Obesity Day

- Healthy Venues

- Reinventing the Food System: A Report

- The Spotlight Project

- SCOPE Examination

- Guide to SCOPE Certification

- SCOPE Schools

- Accreditation

- SCOPE Fellows

- Leadership Programme

- SCOPE Pricing

- SCOPE Accredited Events

- Event Archive

- International Congress on Obesity

Sign up for notifications

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search