21 Research Limitations Examples

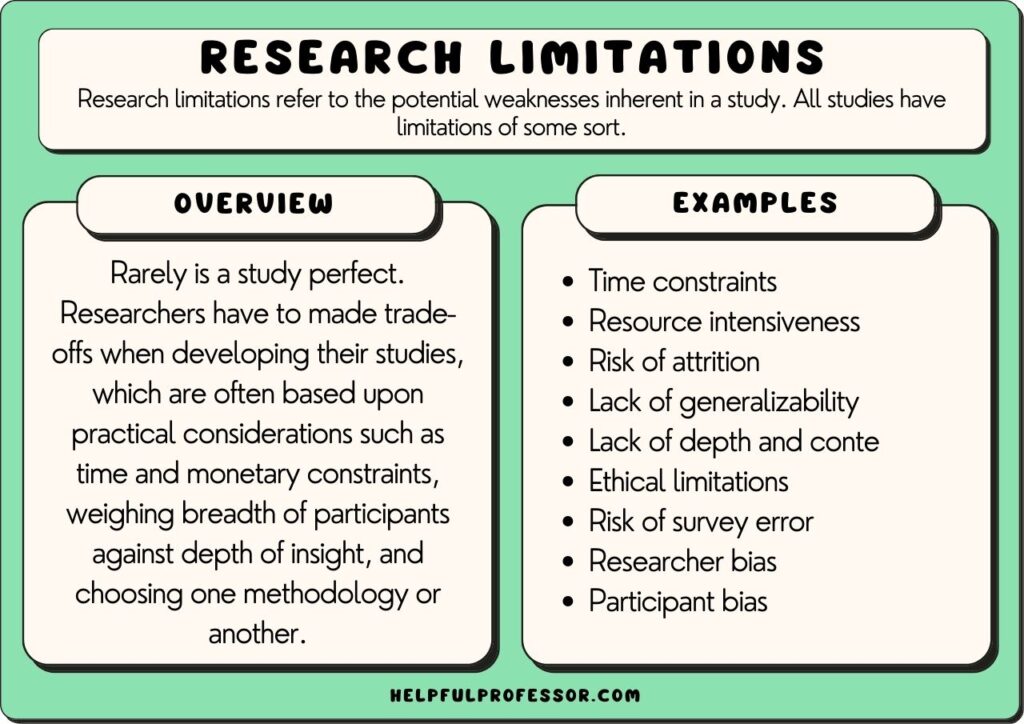

Research limitations refer to the potential weaknesses inherent in a study. All studies have limitations of some sort, meaning declaring limitations doesn’t necessarily need to be a bad thing, so long as your declaration of limitations is well thought-out and explained.

Rarely is a study perfect. Researchers have to make trade-offs when developing their studies, which are often based upon practical considerations such as time and monetary constraints, weighing the breadth of participants against the depth of insight, and choosing one methodology or another.

In research, studies can have limitations such as limited scope, researcher subjectivity, and lack of available research tools.

Acknowledging the limitations of your study should be seen as a strength. It demonstrates your willingness for transparency, humility, and submission to the scientific method and can bolster the integrity of the study. It can also inform future research direction.

Typically, scholars will explore the limitations of their study in either their methodology section, their conclusion section, or both.

Research Limitations Examples

Qualitative and quantitative research offer different perspectives and methods in exploring phenomena, each with its own strengths and limitations. So, I’ve split the limitations examples sections into qualitative and quantitative below.

Qualitative Research Limitations

Qualitative research seeks to understand phenomena in-depth and in context. It focuses on the ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions.

It’s often used to explore new or complex issues, and it provides rich, detailed insights into participants’ experiences, behaviors, and attitudes. However, these strengths also create certain limitations, as explained below.

1. Subjectivity

Qualitative research often requires the researcher to interpret subjective data. One researcher may examine a text and identify different themes or concepts as more dominant than others.

Close qualitative readings of texts are necessarily subjective – and while this may be a limitation, qualitative researchers argue this is the best way to deeply understand everything in context.

Suggested Solution and Response: To minimize subjectivity bias, you could consider cross-checking your own readings of themes and data against other scholars’ readings and interpretations. This may involve giving the raw data to a supervisor or colleague and asking them to code the data separately, then coming together to compare and contrast results.

2. Researcher Bias

The concept of researcher bias is related to, but slightly different from, subjectivity.

Researcher bias refers to the perspectives and opinions you bring with you when doing your research.

For example, a researcher who is explicitly of a certain philosophical or political persuasion may bring that persuasion to bear when interpreting data.

In many scholarly traditions, we will attempt to minimize researcher bias through the utilization of clear procedures that are set out in advance or through the use of statistical analysis tools.

However, in other traditions, such as in postmodern feminist research , declaration of bias is expected, and acknowledgment of bias is seen as a positive because, in those traditions, it is believed that bias cannot be eliminated from research, so instead, it is a matter of integrity to present it upfront.

Suggested Solution and Response: Acknowledge the potential for researcher bias and, depending on your theoretical framework , accept this, or identify procedures you have taken to seek a closer approximation to objectivity in your coding and analysis.

3. Generalizability

If you’re struggling to find a limitation to discuss in your own qualitative research study, then this one is for you: all qualitative research, of all persuasions and perspectives, cannot be generalized.

This is a core feature that sets qualitative data and quantitative data apart.

The point of qualitative data is to select case studies and similarly small corpora and dig deep through in-depth analysis and thick description of data.

Often, this will also mean that you have a non-randomized sample size.

While this is a positive – you’re going to get some really deep, contextualized, interesting insights – it also means that the findings may not be generalizable to a larger population that may not be representative of the small group of people in your study.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that take a quantitative approach to the question.

4. The Hawthorne Effect

The Hawthorne effect refers to the phenomenon where research participants change their ‘observed behavior’ when they’re aware that they are being observed.

This effect was first identified by Elton Mayo who conducted studies of the effects of various factors ton workers’ productivity. He noticed that no matter what he did – turning up the lights, turning down the lights, etc. – there was an increase in worker outputs compared to prior to the study taking place.

Mayo realized that the mere act of observing the workers made them work harder – his observation was what was changing behavior.

So, if you’re looking for a potential limitation to name for your observational research study , highlight the possible impact of the Hawthorne effect (and how you could reduce your footprint or visibility in order to decrease its likelihood).

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight ways you have attempted to reduce your footprint while in the field, and guarantee anonymity to your research participants.

5. Replicability

Quantitative research has a great benefit in that the studies are replicable – a researcher can get a similar sample size, duplicate the variables, and re-test a study. But you can’t do that in qualitative research.

Qualitative research relies heavily on context – a specific case study or specific variables that make a certain instance worthy of analysis. As a result, it’s often difficult to re-enter the same setting with the same variables and repeat the study.

Furthermore, the individual researcher’s interpretation is more influential in qualitative research, meaning even if a new researcher enters an environment and makes observations, their observations may be different because subjectivity comes into play much more. This doesn’t make the research bad necessarily (great insights can be made in qualitative research), but it certainly does demonstrate a weakness of qualitative research.

6. Limited Scope

“Limited scope” is perhaps one of the most common limitations listed by researchers – and while this is often a catch-all way of saying, “well, I’m not studying that in this study”, it’s also a valid point.

No study can explore everything related to a topic. At some point, we have to make decisions about what’s included in the study and what is excluded from the study.

So, you could say that a limitation of your study is that it doesn’t look at an extra variable or concept that’s certainly worthy of study but will have to be explored in your next project because this project has a clearly and narrowly defined goal.

Suggested Solution and Response: Be clear about what’s in and out of the study when writing your research question.

7. Time Constraints

This is also a catch-all claim you can make about your research project: that you would have included more people in the study, looked at more variables, and so on. But you’ve got to submit this thing by the end of next semester! You’ve got time constraints.

And time constraints are a recognized reality in all research.

But this means you’ll need to explain how time has limited your decisions. As with “limited scope”, this may mean that you had to study a smaller group of subjects, limit the amount of time you spent in the field, and so forth.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will build on your current work, possibly as a PhD project.

8. Resource Intensiveness

Qualitative research can be expensive due to the cost of transcription, the involvement of trained researchers, and potential travel for interviews or observations.

So, resource intensiveness is similar to the time constraints concept. If you don’t have the funds, you have to make decisions about which tools to use, which statistical software to employ, and how many research assistants you can dedicate to the study.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will gain more funding on the back of this ‘ exploratory study ‘.

9. Coding Difficulties

Data analysis in qualitative research often involves coding, which can be subjective and complex, especially when dealing with ambiguous or contradicting data.

After naming this as a limitation in your research, it’s important to explain how you’ve attempted to address this. Some ways to ‘limit the limitation’ include:

- Triangulation: Have 2 other researchers code the data as well and cross-check your results with theirs to identify outliers that may need to be re-examined, debated with the other researchers, or removed altogether.

- Procedure: Use a clear coding procedure to demonstrate reliability in your coding process. I personally use the thematic network analysis method outlined in this academic article by Attride-Stirling (2001).

Suggested Solution and Response: Triangulate your coding findings with colleagues, and follow a thematic network analysis procedure.

10. Risk of Non-Responsiveness

There is always a risk in research that research participants will be unwilling or uncomfortable sharing their genuine thoughts and feelings in the study.

This is particularly true when you’re conducting research on sensitive topics, politicized topics, or topics where the participant is expressing vulnerability .

This is similar to the Hawthorne effect (aka participant bias), where participants change their behaviors in your presence; but it goes a step further, where participants actively hide their true thoughts and feelings from you.

Suggested Solution and Response: One way to manage this is to try to include a wider group of people with the expectation that there will be non-responsiveness from some participants.

11. Risk of Attrition

Attrition refers to the process of losing research participants throughout the study.

This occurs most commonly in longitudinal studies , where a researcher must return to conduct their analysis over spaced periods of time, often over a period of years.

Things happen to people over time – they move overseas, their life experiences change, they get sick, change their minds, and even die. The more time that passes, the greater the risk of attrition.

Suggested Solution and Response: One way to manage this is to try to include a wider group of people with the expectation that there will be attrition over time.

12. Difficulty in Maintaining Confidentiality and Anonymity

Given the detailed nature of qualitative data , ensuring participant anonymity can be challenging.

If you have a sensitive topic in a specific case study, even anonymizing research participants sometimes isn’t enough. People might be able to induce who you’re talking about.

Sometimes, this will mean you have to exclude some interesting data that you collected from your final report. Confidentiality and anonymity come before your findings in research ethics – and this is a necessary limiting factor.

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight the efforts you have taken to anonymize data, and accept that confidentiality and accountability place extremely important constraints on academic research.

13. Difficulty in Finding Research Participants

A study that looks at a very specific phenomenon or even a specific set of cases within a phenomenon means that the pool of potential research participants can be very low.

Compile on top of this the fact that many people you approach may choose not to participate, and you could end up with a very small corpus of subjects to explore. This may limit your ability to make complete findings, even in a quantitative sense.

You may need to therefore limit your research question and objectives to something more realistic.

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight that this is going to limit the study’s generalizability significantly.

14. Ethical Limitations

Ethical limitations refer to the things you cannot do based on ethical concerns identified either by yourself or your institution’s ethics review board.

This might include threats to the physical or psychological well-being of your research subjects, the potential of releasing data that could harm a person’s reputation, and so on.

Furthermore, even if your study follows all expected standards of ethics, you still, as an ethical researcher, need to allow a research participant to pull out at any point in time, after which you cannot use their data, which demonstrates an overlap between ethical constraints and participant attrition.

Suggested Solution and Response: Highlight that these ethical limitations are inevitable but important to sustain the integrity of the research.

For more on Qualitative Research, Explore my Qualitative Research Guide

Quantitative Research Limitations

Quantitative research focuses on quantifiable data and statistical, mathematical, or computational techniques. It’s often used to test hypotheses, assess relationships and causality, and generalize findings across larger populations.

Quantitative research is widely respected for its ability to provide reliable, measurable, and generalizable data (if done well!). Its structured methodology has strengths over qualitative research, such as the fact it allows for replication of the study, which underpins the validity of the research.

However, this approach is not without it limitations, explained below.

1. Over-Simplification

Quantitative research is powerful because it allows you to measure and analyze data in a systematic and standardized way. However, one of its limitations is that it can sometimes simplify complex phenomena or situations.

In other words, it might miss the subtleties or nuances of the research subject.

For example, if you’re studying why people choose a particular diet, a quantitative study might identify factors like age, income, or health status. But it might miss other aspects, such as cultural influences or personal beliefs, that can also significantly impact dietary choices.

When writing about this limitation, you can say that your quantitative approach, while providing precise measurements and comparisons, may not capture the full complexity of your subjects of study.

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest a follow-up case study using the same research participants in order to gain additional context and depth.

2. Lack of Context

Another potential issue with quantitative research is that it often focuses on numbers and statistics at the expense of context or qualitative information.

Let’s say you’re studying the effect of classroom size on student performance. You might find that students in smaller classes generally perform better. However, this doesn’t take into account other variables, like teaching style , student motivation, or family support.

When describing this limitation, you might say, “Although our research provides important insights into the relationship between class size and student performance, it does not incorporate the impact of other potentially influential variables. Future research could benefit from a mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative analysis with qualitative insights.”

3. Applicability to Real-World Settings

Oftentimes, experimental research takes place in controlled environments to limit the influence of outside factors.

This control is great for isolation and understanding the specific phenomenon but can limit the applicability or “external validity” of the research to real-world settings.

For example, if you conduct a lab experiment to see how sleep deprivation impacts cognitive performance, the sterile, controlled lab environment might not reflect real-world conditions where people are dealing with multiple stressors.

Therefore, when explaining the limitations of your quantitative study in your methodology section, you could state:

“While our findings provide valuable information about [topic], the controlled conditions of the experiment may not accurately represent real-world scenarios where extraneous variables will exist. As such, the direct applicability of our results to broader contexts may be limited.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will engage in real-world observational research, such as ethnographic research.

4. Limited Flexibility

Once a quantitative study is underway, it can be challenging to make changes to it. This is because, unlike in grounded research, you’re putting in place your study in advance, and you can’t make changes part-way through.

Your study design, data collection methods, and analysis techniques need to be decided upon before you start collecting data.

For example, if you are conducting a survey on the impact of social media on teenage mental health, and halfway through, you realize that you should have included a question about their screen time, it’s generally too late to add it.

When discussing this limitation, you could write something like, “The structured nature of our quantitative approach allows for consistent data collection and analysis but also limits our flexibility to adapt and modify the research process in response to emerging insights and ideas.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will use mixed-methods or qualitative research methods to gain additional depth of insight.

5. Risk of Survey Error

Surveys are a common tool in quantitative research, but they carry risks of error.

There can be measurement errors (if a question is misunderstood), coverage errors (if some groups aren’t adequately represented), non-response errors (if certain people don’t respond), and sampling errors (if your sample isn’t representative of the population).

For instance, if you’re surveying college students about their study habits , but only daytime students respond because you conduct the survey during the day, your results will be skewed.

In discussing this limitation, you might say, “Despite our best efforts to develop a comprehensive survey, there remains a risk of survey error, including measurement, coverage, non-response, and sampling errors. These could potentially impact the reliability and generalizability of our findings.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will use other survey tools to compare and contrast results.

6. Limited Ability to Probe Answers

With quantitative research, you typically can’t ask follow-up questions or delve deeper into participants’ responses like you could in a qualitative interview.

For instance, imagine you are surveying 500 students about study habits in a questionnaire. A respondent might indicate that they study for two hours each night. You might want to follow up by asking them to elaborate on what those study sessions involve or how effective they feel their habits are.

However, quantitative research generally disallows this in the way a qualitative semi-structured interview could.

When discussing this limitation, you might write, “Given the structured nature of our survey, our ability to probe deeper into individual responses is limited. This means we may not fully understand the context or reasoning behind the responses, potentially limiting the depth of our findings.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that engage in mixed-method or qualitative methodologies to address the issue from another angle.

7. Reliance on Instruments for Data Collection

In quantitative research, the collection of data heavily relies on instruments like questionnaires, surveys, or machines.

The limitation here is that the data you get is only as good as the instrument you’re using. If the instrument isn’t designed or calibrated well, your data can be flawed.

For instance, if you’re using a questionnaire to study customer satisfaction and the questions are vague, confusing, or biased, the responses may not accurately reflect the customers’ true feelings.

When discussing this limitation, you could say, “Our study depends on the use of questionnaires for data collection. Although we have put significant effort into designing and testing the instrument, it’s possible that inaccuracies or misunderstandings could potentially affect the validity of the data collected.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will use different instruments but examine the same variables to triangulate results.

8. Time and Resource Constraints (Specific to Quantitative Research)

Quantitative research can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, especially when dealing with large samples.

It often involves systematic sampling, rigorous design, and sometimes complex statistical analysis.

If resources and time are limited, it can restrict the scale of your research, the techniques you can employ, or the extent of your data analysis.

For example, you may want to conduct a nationwide survey on public opinion about a certain policy. However, due to limited resources, you might only be able to survey people in one city.

When writing about this limitation, you could say, “Given the scope of our research and the resources available, we are limited to conducting our survey within one city, which may not fully represent the nationwide public opinion. Hence, the generalizability of the results may be limited.”

Suggested Solution and Response: Suggest future studies that will have more funding or longer timeframes.

How to Discuss Your Research Limitations

1. in your research proposal and methodology section.

In the research proposal, which will become the methodology section of your dissertation, I would recommend taking the four following steps, in order:

- Be Explicit about your Scope – If you limit the scope of your study in your research question, aims, and objectives, then you can set yourself up well later in the methodology to say that certain questions are “outside the scope of the study.” For example, you may identify the fact that the study doesn’t address a certain variable, but you can follow up by stating that the research question is specifically focused on the variable that you are examining, so this limitation would need to be looked at in future studies.

- Acknowledge the Limitation – Acknowledging the limitations of your study demonstrates reflexivity and humility and can make your research more reliable and valid. It also pre-empts questions the people grading your paper may have, so instead of them down-grading you for your limitations; they will congratulate you on explaining the limitations and how you have addressed them!

- Explain your Decisions – You may have chosen your approach (despite its limitations) for a very specific reason. This might be because your approach remains, on balance, the best one to answer your research question. Or, it might be because of time and monetary constraints that are outside of your control.

- Highlight the Strengths of your Approach – Conclude your limitations section by strongly demonstrating that, despite limitations, you’ve worked hard to minimize the effects of the limitations and that you have chosen your specific approach and methodology because it’s also got some terrific strengths. Name the strengths.

Overall, you’ll want to acknowledge your own limitations but also explain that the limitations don’t detract from the value of your study as it stands.

2. In the Conclusion Section or Chapter

In the conclusion of your study, it is generally expected that you return to a discussion of the study’s limitations. Here, I recommend the following steps:

- Acknowledge issues faced – After completing your study, you will be increasingly aware of issues you may have faced that, if you re-did the study, you may have addressed earlier in order to avoid those issues. Acknowledge these issues as limitations, and frame them as recommendations for subsequent studies.

- Suggest further research – Scholarly research aims to fill gaps in the current literature and knowledge. Having established your expertise through your study, suggest lines of inquiry for future researchers. You could state that your study had certain limitations, and “future studies” can address those limitations.

- Suggest a mixed methods approach – Qualitative and quantitative research each have pros and cons. So, note those ‘cons’ of your approach, then say the next study should approach the topic using the opposite methodology or could approach it using a mixed-methods approach that could achieve the benefits of quantitative studies with the nuanced insights of associated qualitative insights as part of an in-study case-study.

Overall, be clear about both your limitations and how those limitations can inform future studies.

In sum, each type of research method has its own strengths and limitations. Qualitative research excels in exploring depth, context, and complexity, while quantitative research excels in examining breadth, generalizability, and quantifiable measures. Despite their individual limitations, each method contributes unique and valuable insights, and researchers often use them together to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon being studied.

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative research , 1 (3), 385-405. ( Source )

Atkinson, P., Delamont, S., Cernat, A., Sakshaug, J., & Williams, R. A. (2021). SAGE research methods foundations . London: Sage Publications.

Clark, T., Foster, L., Bryman, A., & Sloan, L. (2021). Bryman’s social research methods . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Köhler, T., Smith, A., & Bhakoo, V. (2022). Templates in qualitative research methods: Origins, limitations, and new directions. Organizational Research Methods , 25 (2), 183-210. ( Source )

Lenger, A. (2019). The rejection of qualitative research methods in economics. Journal of Economic Issues , 53 (4), 946-965. ( Source )

Taherdoost, H. (2022). What are different research approaches? Comprehensive review of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method research, their applications, types, and limitations. Journal of Management Science & Engineering Research , 5 (1), 53-63. ( Source )

Walliman, N. (2021). Research methods: The basics . New York: Routledge.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Self-Actualization Examples (Maslow's Hierarchy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Forest Schools Philosophy & Curriculum, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori's 4 Planes of Development, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori vs Reggio Emilia vs Steiner-Waldorf vs Froebel

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How to Write Limitations of the Study (with examples)

This blog emphasizes the importance of recognizing and effectively writing about limitations in research. It discusses the types of limitations, their significance, and provides guidelines for writing about them, highlighting their role in advancing scholarly research.

Updated on August 24, 2023

No matter how well thought out, every research endeavor encounters challenges. There is simply no way to predict all possible variances throughout the process.

These uncharted boundaries and abrupt constraints are known as limitations in research . Identifying and acknowledging limitations is crucial for conducting rigorous studies. Limitations provide context and shed light on gaps in the prevailing inquiry and literature.

This article explores the importance of recognizing limitations and discusses how to write them effectively. By interpreting limitations in research and considering prevalent examples, we aim to reframe the perception from shameful mistakes to respectable revelations.

What are limitations in research?

In the clearest terms, research limitations are the practical or theoretical shortcomings of a study that are often outside of the researcher’s control . While these weaknesses limit the generalizability of a study’s conclusions, they also present a foundation for future research.

Sometimes limitations arise from tangible circumstances like time and funding constraints, or equipment and participant availability. Other times the rationale is more obscure and buried within the research design. Common types of limitations and their ramifications include:

- Theoretical: limits the scope, depth, or applicability of a study.

- Methodological: limits the quality, quantity, or diversity of the data.

- Empirical: limits the representativeness, validity, or reliability of the data.

- Analytical: limits the accuracy, completeness, or significance of the findings.

- Ethical: limits the access, consent, or confidentiality of the data.

Regardless of how, when, or why they arise, limitations are a natural part of the research process and should never be ignored . Like all other aspects, they are vital in their own purpose.

Why is identifying limitations important?

Whether to seek acceptance or avoid struggle, humans often instinctively hide flaws and mistakes. Merging this thought process into research by attempting to hide limitations, however, is a bad idea. It has the potential to negate the validity of outcomes and damage the reputation of scholars.

By identifying and addressing limitations throughout a project, researchers strengthen their arguments and curtail the chance of peer censure based on overlooked mistakes. Pointing out these flaws shows an understanding of variable limits and a scrupulous research process.

Showing awareness of and taking responsibility for a project’s boundaries and challenges validates the integrity and transparency of a researcher. It further demonstrates the researchers understand the applicable literature and have thoroughly evaluated their chosen research methods.

Presenting limitations also benefits the readers by providing context for research findings. It guides them to interpret the project’s conclusions only within the scope of very specific conditions. By allowing for an appropriate generalization of the findings that is accurately confined by research boundaries and is not too broad, limitations boost a study’s credibility .

Limitations are true assets to the research process. They highlight opportunities for future research. When researchers identify the limitations of their particular approach to a study question, they enable precise transferability and improve chances for reproducibility.

Simply stating a project’s limitations is not adequate for spurring further research, though. To spark the interest of other researchers, these acknowledgements must come with thorough explanations regarding how the limitations affected the current study and how they can potentially be overcome with amended methods.

How to write limitations

Typically, the information about a study’s limitations is situated either at the beginning of the discussion section to provide context for readers or at the conclusion of the discussion section to acknowledge the need for further research. However, it varies depending upon the target journal or publication guidelines.

Don’t hide your limitations

It is also important to not bury a limitation in the body of the paper unless it has a unique connection to a topic in that section. If so, it needs to be reiterated with the other limitations or at the conclusion of the discussion section. Wherever it is included in the manuscript, ensure that the limitations section is prominently positioned and clearly introduced.

While maintaining transparency by disclosing limitations means taking a comprehensive approach, it is not necessary to discuss everything that could have potentially gone wrong during the research study. If there is no commitment to investigation in the introduction, it is unnecessary to consider the issue a limitation to the research. Wholly consider the term ‘limitations’ and ask, “Did it significantly change or limit the possible outcomes?” Then, qualify the occurrence as either a limitation to include in the current manuscript or as an idea to note for other projects.

Writing limitations

Once the limitations are concretely identified and it is decided where they will be included in the paper, researchers are ready for the writing task. Including only what is pertinent, keeping explanations detailed but concise, and employing the following guidelines is key for crafting valuable limitations:

1) Identify and describe the limitations : Clearly introduce the limitation by classifying its form and specifying its origin. For example:

- An unintentional bias encountered during data collection

- An intentional use of unplanned post-hoc data analysis

2) Explain the implications : Describe how the limitation potentially influences the study’s findings and how the validity and generalizability are subsequently impacted. Provide examples and evidence to support claims of the limitations’ effects without making excuses or exaggerating their impact. Overall, be transparent and objective in presenting the limitations, without undermining the significance of the research.

3) Provide alternative approaches for future studies : Offer specific suggestions for potential improvements or avenues for further investigation. Demonstrate a proactive approach by encouraging future research that addresses the identified gaps and, therefore, expands the knowledge base.

Whether presenting limitations as an individual section within the manuscript or as a subtopic in the discussion area, authors should use clear headings and straightforward language to facilitate readability. There is no need to complicate limitations with jargon, computations, or complex datasets.

Examples of common limitations

Limitations are generally grouped into two categories , methodology and research process .

Methodology limitations

Methodology may include limitations due to:

- Sample size

- Lack of available or reliable data

- Lack of prior research studies on the topic

- Measure used to collect the data

- Self-reported data

The researcher is addressing how the large sample size requires a reassessment of the measures used to collect and analyze the data.

Research process limitations

Limitations during the research process may arise from:

- Access to information

- Longitudinal effects

- Cultural and other biases

- Language fluency

- Time constraints

The author is pointing out that the model’s estimates are based on potentially biased observational studies.

Final thoughts

Successfully proving theories and touting great achievements are only two very narrow goals of scholarly research. The true passion and greatest efforts of researchers comes more in the form of confronting assumptions and exploring the obscure.

In many ways, recognizing and sharing the limitations of a research study both allows for and encourages this type of discovery that continuously pushes research forward. By using limitations to provide a transparent account of the project's boundaries and to contextualize the findings, researchers pave the way for even more robust and impactful research in the future.

Charla Viera, MS

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.28(1); Jan-Mar 2024

- PMC10882193

Limitations in Medical Research: Recognition, Influence, and Warning

Douglas e. ott.

Mercer University, Macon, Georgia, USA.

Background:

As the number of limitations increases in a medical research article, their consequences multiply and the validity of findings decreases. How often do limitations occur in a medical article? What are the implications of limitation interaction? How often are the conclusions hedged in their explanation?

To identify the number, type, and frequency of limitations and words used to describe conclusion(s) in medical research articles.

Search, analysis, and evaluation of open access research articles from 2021 and 2022 from the Journal of the Society of Laparoscopic and Robotic Surgery and 2022 Surgical Endoscopy for type(s) of limitation(s) admitted to by author(s) and the number of times they occurred. Limitations not admitted to were found, obvious, and not claimed. An automated text analysis was performed for hedging words in conclusion statements. A limitation index score is proposed to gauge the validity of statements and conclusions as the number of limitations increases.

A total of 298 articles were reviewed and analyzed, finding 1,764 limitations. Four articles had no limitations. The average was between 3.7% and 6.9% per article. Hedging, weasel words and words of estimative probability description was found in 95.6% of the conclusions.

Conclusions:

Limitations and their number matter. The greater the number of limitations and ramifications of their effects, the more outcomes and conclusions are affected. Wording ambiguity using hedging or weasel words shows that limitations affect the uncertainty of claims. The limitation index scoring method shows the diminished validity of finding(s) and conclusion(s).

INTRODUCTION

As the number of limitations in a medical research article increases, does their influence have a more significant effect than each one considered separately, making the findings and conclusions less reliable and valid? Limitations are known variables that influence data collection and findings and compromise outcomes, conclusions, and inferences. A large body of work recognizes the effect(s) and consequence(s) of limitations. 1 – 77 Other than the ones known to the author(s), unknown and unrecognized limitations influence research credibility. This study and analysis aim to determine how frequently and what limitations are found in peer-reviewed open-access medical articles for laparoscopic/endoscopic surgeons.

This research is about limitations, how often they occur and explained and/or justified. Failure to disclose limitations in medical writing limits proper decision-making and understanding of the material presented. All articles have limitations and constraints. Not acknowledging limitations is a lack of candor, ignorance, or a deliberate omission. To reduce the suspicion of invalid conclusions limitations and their effects must be acknowledged and explained. This allows for a clearer more focused assessment of the article’s subject matter without explaining its findings and conclusions using hedging and words of estimative probability. 78 , 79

An evaluation of open access research/meta-analysis/case series/methodologies/review articles published in the Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic and Robotic Surgery ( JSLS ) for 2021 and 2022 (129) and commentary/guidelines/new technology/practice guidelines/review/SAGES Masters Program articles in Surgical Endoscopy ( Surg Endosc ) for 2022 (169) totaling 298 were read and evaluated by automated text analysis for limitations admitted to by the paper’s authors using such words as “limitations,” “limits,” “shortcomings,” “inadequacies,” “flaws,” “weaknesses,” “constraints,” “deficiencies,” “problems,” and “drawbacks” in the search. Limitations not mentioned were found by reading the paper and assigning type and frequency. The number of hedging and weasel words used to describe the conclusion or validate findings was determined by reading the article and adding them up.

For JSLS , there were 129 articles having 63 different types of limitations. Authors claimed 476, and an additional 32 were found within the article, totaling 508 limitations (93.7% admitted to and 6.3% discovered that were not mentioned). This was a 3.9 limitation average per article. No article said it was free of limitations. The ten most frequent limitations and their rate of occurrence are in Table 1 . The total number of limitations, frequency, and visual depictions are seen in Figures 1A and and 1B 1B .

( A ) Visual depiction of the ranked frequency of limitations for JSLS articles reviewed.

The Ten Most Frequent Limitations Found in JSLS and Surg Endosc Articles

There were 169 articles for Surg Endosc , with 78 different named limitations the authors claimed for a total of 1,162. An additional 94 limitations were found in the articles, totaling 1,256, or 7.4 per article. The authors explicitly stated 92.5% of the limitations, and an additional 7.5% of additional limitations were found within the article. Five claimed zero limitations (5/169 = 3%). The ten most frequent limitations and their rate of occurrence are in Table 1 . The total number of limitations and frequency is shown in Figures 1A and and 1B 1B .

Conclusions were described in hedged, weasel words or words of estimative probability 95.6% of the time (285/298).

A research hypothesis aims to test the idea about expected relationships between variables or to explain an occurrence. The assessment of a hypothesis with limitations embedded in the method reaches a conclusion that is inherently flawed. What is compromised by the limitation(s)? The result is an inferential study in the presence of uncertainty. As the number of limitations increases, the validity of information decreases due to the proliferation of uncertain information. Information gathered and conclusions made in the presence of limitations can be functionally unsound. Hypothesis testing of spurious conditions with limitations and then claiming a conclusion is not a reliable method for generating factual evidence. The authors’ reliance on limitation gathered “evidence” data and asserting that this is valid is spurious reasoning. The bridge between theory and evidence is not through limitations that unquestionably accept findings. A range of conclusion possibilities exists being some percent closer to either more correct or incorrect. Relying on leveraging the pursuit of “fact” in the presence of limitations as the safeguard is akin to the fox watching the hen house. Acknowledgment of the uncertainty limitations create in research and discounting the finding’s reliability would give more credibility to the effort. Shortcomings and widespread misuses of research limitation justifications make findings suspect and falsely justified in many instances.

The JSLS instructions to authors say that in the discussion section of the paper the author(s) must “Comment on any methodological weaknesses of the study” ( http://jsls.sls.org/guidelines-for-authors/ ). In their instructions for authors, Surg Endosc says that in the discussion of the paper, “A paragraph discussing study limitations is required” ( https://www.springer.com/journal/464/submission-guidelines ). A comment for a written article about a limitation should express an opinion or reaction. A paragraph discussing limitations, especially, if there is more than one, requires just that: a paragraph and discussion. These requirements were not met or enforced by JSLS 86% (111/129) of the time and 92.3% (156/169) for Surg Endosc . This is an error in peer reviewing, not adhering to established research publication best practices, and the journals needing to adhere to their guidelines. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, uniform requirements for manuscripts recommends that authors “State the limitations of your study, and explore the implications of your findings for future research and for clinical practice or policy. Discuss the influence or association of variables, such as sex and/or gender, on your findings, where appropriate, and the limitations of the data.” It also says, “describe new or substantially modified methods, give reasons for using them, and evaluate their limitations” and “Include in the Discussion section the implications of the findings and their limitations, including implications for future research” and “give references to established methods, including statistical methods (see below); provide references and brief descriptions for methods that have been published but are not well known; describe new or substantially modified methods, give reasons for using them, and evaluate their limitations.” 65 “Reporting guidelines (e.g., CONSORT, 1 ARRIVE 2 ) have been proposed to promote the transparency and accuracy of reporting for biomedical studies, and they often include discussion of limitations as a checklist item. Although such guidelines have been endorsed by high-profile biomedical journals, and compliance with them is associated with improved reporting quality, 3 adherence remains suboptimal.” 4 , 5

Limitations start in the methodologic design phase of research. They require troubleshooting evaluations from the start to consider what limitations exist, what is known and unknown, where, and how to overcome them, and how they will affect the reasonableness and assessment of possible conclusions. A named limitation represents a category with numerous components. Each factor has a unique effect on findings and collectively influences conclusion assessment. Even a single limitation can compromise the study’s implementation and adversely influence research parameters, resulting in diminished value of the findings, outcomes, and conclusions. This becomes more problematic as the number of limitations and their components increase. Any limitation influences a research paper. It is unknown how much and to what extent any limitation affects other limitations, but it does create a cascading domino effect of ever-increasing interactions that compromise findings and conclusions. Considering “research” as a system, it has sensitivity and initial conditions (methodology, data collection, analysis, etc.). The slightest alteration of a study due to limitations can profoundly impact all aspects of the study. The presence and influence of limitations introduce a range of unpredictable influences on findings, results, and conclusions.

Researchers and readers need to pay attention to and discount the effects limitations have on the validity of findings. Richard Feynman said in “Cargo cult science” “the first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.” 73 We strongly believe our own nonsense or wrong-headed reasoning. Buddhist philosophers say we are attached to our ignorance. Researchers are not critical enough about how they fool themselves regarding their findings with known limitations and then pass them on to readers. The competence of findings with known limitations results in suspect conclusions.

Authors should not ask for dismissal, disregard, or indulgence of their limitations. They should be thoughtful and reflective about the implications and uncertainty the limitations create 67 ; their uncertainties, blind spots, and impact on the research’s relevance. A meaningful presentation of study limitations should describe the limitation, explain its effect, provide possible alternative approaches, and describe steps taken to mitigate the limitation. This was largely absent from the articles reviewed.

Authors use synonyms and phrases describing limitations that hide, deflect, downplay, and divert attention from them, i.e., some drawbacks of the study are …, weaknesses of the study are…, shortcomings are…, and disadvantages of the study are…. They then say their finding(s) lack(s) generalizability, meaning the findings only apply to the study participants or that care, sometimes extreme, must be taken in interpreting the results. Which limitation components are they referring to? Are the authors aware of the extent of their limitations, or are they using convenient phrases to highlight the existence of limitations without detailing their defects?

Limitations negatively weigh on both data and conclusions yet no literature exists to provide a quantifiable measure of this effect. The only acknowledgment is that limitations affect research data and conclusions. The adverse effects of limitations are both specific and contextual to each research article and is part of the parameters that affect research. All the limitations are expressed in words, excuses, and a litany of mea culpas asking for forgiveness and without explaining the extent or magnitude of their impact. It is left to the writer and reader to figure out. It is not known what value writers put on their limitations in the 298 articles reviewed from JSLS and Surg Endosc . Listing limitations without comment and effect on the findings and conclusions is a compromising red flag. Therefore, a limitation scoring method was developed and is proposed to assess the level of suspicion generated by the number of limitations.

It is doubtful that a medical research article is so well designed and executed that there are no limitations. This is doubtful since there are unknown unknowns. This study showed that authors need to acknowledge all the limitations when they are known. They acknowledge the ones they know but do not consider other possibilities. There are the known known limitations; the ones the author(s) are aware of and can be measured, some explained, most not. The known unknowns: limitations authors are aware of but cannot explain or quantify. The unknown unknown limitations: the ones authors are not aware of and have unknown influence(s), i.e., the things they do not know they do not know. These are blind spots (not knowing what they do not know or black swan events). And the unknown knowns; the limitations authors may be aware of but have not disclosed, thoroughly reported, understood, or addressed. They are unexpected and not considered. See Table 2 . 74

Limitations of Known and Unknowns as They Apply to Limitations

It is possible that authors did not identify, want to identify, or acknowledge potential limitations or were unaware of what limitations existed. Cumulative complexity is the result of the presence of multiple limitations because of the accumulation and interaction of limitations and their components. Just mentioning a limitation category and not the specific parts that are the limitation(s) is not enough. Authors telling readers of their known research limitations is a caution to discount the findings and conclusions. At what point does the caution for each limitation, its ramifications, and consequences become a warning? When does the piling up of mistakes, bad and missing data, biases, small sample size, lack of generalizability, confounding factors, etc., reach a point when the findings become s uninterpretable and meaningless? “Caution” indicates a level of potential hazard; a warning is more dire and consequential. Authors use the word “caution” not “warning” to describe their conclusions. There is a point when the number of limitations and their cumulative effects surpasses the point where a caution statement is no longer applicable, and a warning statement is required. This is the reason for establishing a limitations risk score.

Limitations put medical research articles at risk. The accumulation of limitations (variables having additional limitation components) are gaps and flaws diluting the probability of validity. There is currently no assessment method for evaluating the effect(s) of limitations on research outcomes other than awareness that there is an effect. Authors make statements warning that their results may not be reliable or generalizable, and need more research and larger numbers. Just because the weight effect of any given limitation is not known, explained, or how it discounts findings does not negate a causation effect on data, its analysis, and conclusions. Limitation variables and the ramifications of their effects have consequences. The relationship is not zero effect and accumulates with each added limitation.

As a result of this research, a limitation index score (LIS) system and assessment tool were developed. This limitation risk assessment tool gives a scores assessment of the relative validity of conclusions in a medical article having limitations. The adoption of the LIS scoring assessment tool for authors, researchers, editors, reviewers, and readers is a step toward understanding the effects of limitations and their causal relationships to findings and conclusions. The objective is cleaner, tighter methodologies, and better data assessment, to achieve more reliable findings. Adjustments to research conclusions in the presence of limitations are necessary. The degree of modification depends on context. The cumulative effect of this burden must be acknowledged by a tangible reduction and questioning of the legitimacy of statements made under these circumstances. The description calculating the LIS score is detailed in Appendix 1 .

A limitation word or phrase is not one limitation; it is a group of limitations under the heading of that word or phrase having many additional possible components just as an individual named influence. For instance, when an admission of selection bias is noted, the authors do not explain if it was an exclusion criterion, self-selection, nonresponsiveness, lost to follow-up, recruitment error, how it affects external validity, lack of randomization, etc., or any of the least 263 types of known biases causing systematic distortions of the truth whether unintentional or wanton. 40 , 76 Which forms of selection bias are they identifying? 63 Limitations have branches that introduce additional limitations influencing the study’s ability to reach a useful conclusion. Authors rarely tell you the effect consequences and extent limitations have on their study, findings, and conclusions.

This is a sample of limitations and a few of their component variables under the rubric of a single word or phrase. See Table 3 .

A Limitation Word or Phrase is a Limitation Having Additional Components That Are Additional Limitations. When an Author Uses the Limitation Composite Word or Phrase, They Leave out Which One of Its Components is Contributory to the Research Limitations. Each Limitation Interacts with Other Limitations, Creating a Cluster of Cross Complexities of Data, Findings, and Conclusions That Are Tainted and Negatively Affect Findings and Conclusions

Limitations rarely occur alone. If you see one there are many you do not see or appreciate. Limitation s components interact with their own and other limitations, leading to complex connections interacting and discounting the reliability of findings. By how much is context dependent: but it is not zero. Limitations are variables influencing outcomes. As the number of limitations increases, the reliability of the conclusions decreases. How many variables (limitations) does it take to nullify the claims of the findings? The weight and influence of each limitation, its aggregate components, and interconnectedness have an unknown magnitude and effect. The result is a disorderly concoction of hearsay explanations. Table 4 is an example of just two single explanation limitations and some of their components illustrating the complex compounding of their effects on each other.

An Example of Interactions between Only Two Limitations and Some of Their Components Causes 16 Interactions

The novelty of this paper on limitations in medical science is not the identification of research article limitations or their number or frequency; it is the recognition of the multiplier effect(s) limitations and the influence they have on diminishing any conclusion(s) the paper makes. It is possible that limitations contribute to the inability of studies to replicate and why so many are one-time occurrences. Therefore, the generalizability statement that should be given to all readers is BEWARE THERE IS A REDUCTION EFFECT ON THE CONCLUSIONS IN THIS ARTICLE BECAUSE OF ITS LIMITATIONS.

Journals accept studies done with too many limitations, creating forking path situations resulting in an enormous number of possible associations of individual data points as multiple comparisons. 79 The result is confusion, a muddled mess caused by interactions of limitations undermining the ability to make valid inferences. Authors know and acknowledge but rarely explain them or their influence. They also use incomplete and biased databases, biased methods, small sample sizes, and not eliminating confounders, etc., but persist in doing research with these circumstances. Why is that? Is it because when limitations are acknowledged, authors feel justified in their conclusions? It wasn’t my poor research design; it was the limitation(s). How do peer reviewers score and analyze these papers without a method to discount the findings and conclusions in the presence of limitations? What are the calculus editors use to justify papers with multiple limitations, reaching compromised or spurious conclusions? How much caution or warning should a journal say must be taken in interpreting article results? How much? Which results? When? Under what circumstance(s)?

Since a critical component of research is its limitations, the quality and rigor of research are largely defined by, 75 these constraints making it imperative that limitations be exposed and explained. All studies have limitations admitted to or not, and these limitations influence outcomes and conclusions. Unfortunately, they are given insufficient attention, accompanied by feeble excuses, but they all matter. The degrees of freedom of each limitation influence every other limitation, magnifying their ramifications and confusion. Limitations of a scientific article must put the findings in context so the reader can judge the validity and strength of the conclusions. While authors acknowledge the limitations of their study, they influence its legitimacy.

Not only are limitations not properly acknowledged in the scientific literature, 8 but their implications, magnitude, and how they affect a conclusion are not explained or appreciated. Authors work at claiming their work and methods “overcome,” “avoid,” or “circumvent” limitations. Limitations are explained away as “Failure to prove a difference does not prove lack of a difference.” 60 Sample size, bias, confounders, bad data, etc. are not what they seem and do not sully the results. The implication is “trust me.” But that’s not science. Limitations create cognitive distortions and framing (misperception of reality) for the authors and readers. Data in studies with limitations is data having limitations. It was real but tainted.

Limitations are not a trivial aspect of research. It is a tangible something, positive or negative, put into a data set to be analyzed and used to reach a conclusion. How did these extra somethings, known unknowns, not knowns, and unknown knowns, affect the validity of the data set and conclusions? Research presented with the vagaries of explicit limitations is intensified by additional limitations and their component effects on top of the first limitation s , quickly diluting any conclusion making its dependability questionable.

This study’s analysis of limitations in medical articles averaged 3.9% per article for JSLS and 7.4% for Surg Endosc . Authors admit to some and are aware of limitations, but not all of them and discount or leave out others. Limitations were often presented with misleading and hedging language. Authors do not give weight or suggest the percent discount limitations have on the reliance of conclusion(s). Since limitations influence findings, reliability, generalizability, and validity without knowing the magnitude of each and their context, the best that can be said about the conclusions is that they are specific to the study described, context-driven, and suspect.

Limitations mean something is missing, added, incorrect, unseen, unaware of, fabricated, or unknown; circumstances that confuse, confound, and compromise findings and information to the extent that a notice is necessary. All medical articles should have this statement, “Any conclusion drawn from this medical study should be interpreted considering its limitations. Readers should exercise caution, use critical judgement, and consult other sources before accepting these findings. Findings may not be generalizable regardless of sample size, composition, representative data points, and subject groups. Methodologic, analytic, and data collection may have introduced biases or limitations that can affect the accuracy of the results. Controlling for confounding variables, known and unknown, may have influenced the data and/or observations. The accuracy and completeness of the data used to draw a conclusion may not be reliable. The study was specific to time, place, persons, and prevailing circumstances. The weight of each of these factors is unknown to us. Their effect may be limited or compounded and diminish the validity of the proposed conclusions.”

This study and findings are limited and constrained by the limitations of the articles reviewed. They have known and unknown limitations not accounted for, missing data, small sample size, incongruous populations, internal and external validity concerns, confounders, and more. See Tables 2 and and 3 . 3 . Some of these are correctible by the author’s awareness of the consequences of limitations, making plans to address them in the methodology phase of hypothesis assessment and performance of the research to diminish their effects.

Limitations in research articles are expected, but they can be reduced in their effect so that conclusions are closer to being valid. Limitations introduce elements of ignorance and suspicion. They need to be explained so their influence on the believability of the study and its conclusions is closer to meeting construct, content, face, and criterion validity. As the number of limitations increases, common sense, skepticism, study component acceptability, and understanding the ramifications of each limitation are necessary to accept, discount, or reject the author’s findings. As the number of hedging and weasel words used to explain conclusion(s) increases, believability decreases, and raises suspicion regarding claims. Establishing a systematic limitation scoring index limitations for authors, editors, reviewers, and readers and recognizing their cumulative effects will result in a clearer understanding of research content and legitimacy.

How to calculate the Limitation Index Score (LIS). See Tables 5 – 5 . Each limitation admitted to by authors in the article equals (=) one (1) point. Limitations may be generally stated by the author as a broad category, but can have multiple components, such as a retrospective study with these limitation components: 1. data or recall not accurate, 2. data missing, 3. selection bias not controlled, 4. confounders not controlled, 5. no randomization, 6. no blinding, 7. difficult to establish cause and effect, and 8. cannot draw a conclusion of causation. For each component, no matter how many are not explained and corrected, add an additional one (1) point to the score. See Table 2 .

The Limitation Scoring Index is a Numeric Limitation Risk Assessment Score to Rank Risk Categories and Discounting Probability of Validity and Conclusions. The More Limitations in a Study, the Greater the Risk of Unreliable Findings and Conclusions

Limitations May Be Generally Stated by the Author but Have Multiple Components, Such as a Retrospective Study Having Disadvantage Components of 1. Data or Recall Not Accurate, 2. Data Missing, 3. Selection Bias Not Controlled, 4. Confounders Not Controlled, 5. No Randomization, 6. No Blinding, 7 Difficult to Establish Cause and Effect, 8. Results Are Hypothesis Generating, and 9. Cannot Draw a Conclusion of Causation. For Each Component, Not Explained and Corrected, Add an Additional One (1) Point Is Added to the Score. Extra Blanks Are for Additional Limitations

An Automatic 2 Points is Added for Meta-Analysis Studies Since They Have All the Retrospective Detrimental Components. 44 Data from Insurance, State, National, Medicare, and Medicaid, Because of Incorrect Coding, Over Reporting, and Under-Reporting, Etc. Each Component of the Limitation Adds One Additional Point. For Surveys and Questionnaires Add One Additional Point for Each Bias. Extra Blanks Are for Additional Limitations

Automatic Five (5) Points for Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) Database Articles. The FDA Access Data Site Says Submissions Can Be “Incomplete, Inaccurate, Untimely, Unverified, or Biased” and “the Incidence or Prevalence of an Event Cannot Be Determined from This Reporting System Alone Due to Under-Reporting of Events, Inaccuracies in Reports, Lack of Verification That the Device Caused the Reported Event, and Lack of Information” and “DR Data Alone Cannot Be Used to Establish Rates of Events, Evaluate a Change in Event Rates over Time or Compare Event Rates between Devices. The Number of Reports Cannot Be Interpreted or Used in Isolation to Reach Conclusions” 80

Total Limitation Index Score

Each limitation not admitted to = two (2) points. A meta-analysis study gets an automatic 2 points since they are retrospective and have detrimental components that should be added to the 2 points. Data from insurance, state, national, Medicare, and Medicaid, because of incorrect coding, over-reporting, and underreporting, etc., score 2 points, and each component adds one additional point. Surveys and questionnaires get 2 points, and add one additional point for each bias. See Table 3 .

Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database articles receive an automatic five (5) points. The FDA access data site says, submissions can be “incomplete, inaccurate, untimely, unverified, or biased” and “the incidence or prevalence of an event cannot be determined from this reporting system alone due to underreporting of events, inaccuracies in reports, lack of verification that the device caused the reported event, and lack of information” and “MDR data alone cannot be used to establish rates of events, evaluate a change in event rates over time or compare event rates between devices. The number of reports cannot be interpreted or used in isolation to reach conclusions.” 80 See Table 4 . Add one additional point for each additional limitation noted in the article.

Add one additional point for each additional limitation and one point for each of its components. Extra blanks are for additional

limitations and their component scores.

Funding sources: none.

Disclosure: none.

Conflict of interests: none.

Acknowledgments: Author would like to thank Lynda Davis for her help with data collection.

References:

All references have been archived at https://archive.org/web/

How to Write about Research Limitations Without Reducing Your Impact

Being open about what you could not do in your research is actually extremely positive, and it’s viewed favorably by editors and peer reviewers. Writing about your limitations without reducing your impact is a valuable skills that will help your reputation as a researcher.

Areas you might have “failed,” in other words, your limitations, include:

- Aims and objectives (they were a bit too ambitious)

- Study design (not quite right)

- Supporting literature (you’re in uncharted territory)

- Sampling method (if only you’d snowballed it)

- Size of your study population (not enough power)

- Data collection method (bias found its way in)

- Confounding factors (didn’t see that coming!)

Your limitations don’t harm your work and reputation. Quite the opposite, they validate your work and increase your contribution to your field.

Limitations are quite easy to write about in a useful way that won’t reducing your impact. In fact, it’ll increase it.

Why are limitations so important?

Study design limitations, impact limitations, statistical or data limitations, other limitations, how to describe your limitations, where to write your limitations, structure for writing about a limitation, writing up a broader limitation, dealing with breakthroughs and niche-type limitations, dealing with critical flaws, curb your enthusiasm: manage expectations.

Regrettably, the publish-or-perish mentality has created pressure to only come up with successful results. It’s also not too much to say that journals prefer positive studies – where the findings support the hypothesis.

But success alone is not science. Science is trial and error.

So it’s important to present a well-balanced, comprehensive description of your research. That includes your limitations. Accurately reporting your limitations will:

- Help prevent research waste on repeated failures

- Lead to creation of new hypotheses

- Provide useful information for systematic reviews

- Further demonstrate the robustness of your study

Adding clear discussion of any negative results and/or outcomes as well as your study limitations makes you much better able to provide your readers (including peer reviewers ) with:

- Information about your positive results

- Explanation of why your results are credible

- Ideas for future hypothesis generation

- Understanding of why your study has impact

These are good things. There’s even a journal for failure ! That’s how important it is in science.

Some authors find it hard to write about their study limitations, seeing it as an admission of failure. You can do it, and you don’t have to overdo it, either.

Know your limitations and you can anticipate and record them

These might include the procedures, experiments, or reagents (or funding) you have available. As well as specific constraints on the study population. There may be ethical guidelines , and institutional or national policies, that limit what you can do.

These are very common limitations to medical research, for example. We refer to these kinds as study design limitations. Clinical trials, for instance, may have a restriction on interventions expected to have a positive effect. Or there may be restrictions on data collection based on the study population.

Even if your study has a strong design and statistical foundation there might be a strong regional, national, or species-based focus. Or your work could be very population- or experimental-specific.

Your entire field of study, in fact, may only be conducive to incremental findings (e.g., particle physics or molecular biology).

These are inherent limits on impact in that they’re so specific. This limits the extendibility of the findings. It doesn’t however, limit the impact on a specific area or your field. Note the impact and push forward!

Perhaps the most common kind of limitation is statistical or data-based. This category is extremely common in experimental (e.g., chemistry) or field-based (e.g., ecology, population biology, qualitative clinical research) studies.

In many situations, testing hypotheses, you simply may not be able to collect as much data or as good quality data as you want to. Perhaps enrollment was more difficult than expected, under-powering your results.

Statistical limitations can also stem from study design, producing more serious issues in terms of interpreting findings. Seeking expert review from a statistician, such as by using Edanz scientific solutions , may be a good idea before starting your study design.

The above three are often interconnected. And they’re certainly not comprehensive.

As mentioned up top, you may also be limited by the literature. By external confounders. By things you didn’t even see coming (like how long it took you to find 10 qualified respondents for a qualitative study).

Once you’ve identified possible limitations in your work, you need to get to the real point of this post – describing them in your manuscript.

Use the perspective of limitations = contribution and impact to maximize your chances of acceptance.

Reviewers, editors, and readers expect you to present your work authoritatively. You’re the expert in the field, after all. This may make them critical. Embrace that. Counter their possibly negative interpretation by explaining each limitation, showing why the results are still important and useful.

Limitations are usually listed at the end of your Discussion section, though they can also be added throughout. Especially for a long manuscript or for an essay or dissertation, the latter may be useful for the reader.

Writing on your limitations: Words and structure

- This study did have some limitations.

- Three notable limitations affected this study.

- While this study successfully x, there were some limitations.

Giving a specific number is useful for the reader and can guide your writing. But if it’s a longer list, no need to number them. For a short list, you can write them as:

But this gets tiring for more than three limitations (bad RX: reader experience).

So, for longer lists, add a bit of variety in the language to engage the reader. Like this:

- The first issue was…

- Another limitation was…

- Additionally,…

An expert editor will be happy to help you make the English more natural and readable.

After your lead-in sentence, follow a pattern of writing on your findings and related limitation(s), giving a quick interpretation, back it with support (if needed), and offer the next steps.

This provides a complete package for the reader: what happened, what it means, why this is the case, and what is now needed.

In that way, you’ve admitted what may be lacking, but you’ve further established your authority. You’ve also provided a quick roadmap for your reader. That’s an impactful contribution!

It might not always be logical or readable to give that much detail. As long as you fully describe and justify the limitation, you’ve done your job well.

Your study looked at a weight intervention over 6 months at primary healthcare clinics in Japan. The results were generally. But because you only looked at Japanese patients, these findings may not be extendible to patients of other cultures/nationalities, etc.

That’s not a failure at all. It’s a success. But it is a limitation. And other researchers can learn from it and build on it. Write it up in the limitations.

Finding: We found that, in the intervention group, BMI was reduced over 6 months.

Interpretation (and support): This suggests a regimen of routine testing and measurement followed by personalized health guidance from primary physicians had a positive effect on patients’ conditions.

Support: Yamazaki (2019) and Endo et al. (2020) found similar results in urban Japanese clinics and hospitals, respectively.

Limitation and how to use it: While these are useful findings, they are limited by only including Japanese populations. This does not ensure these interventions would be as effective in other nations or cultures. Similar interventions, adapted to the local healthcare and cultural conditions, would help to further clarify the methods.

Now you’ve stated the value of your finding, the limitation, and what to do with it. Nice impact!

Another hurdle you may hit is when your results are particularly novel or you’re publishing in a little-researched field. Those are limitations that need to be stated. In this case, you can support your findings by reinforcing the novelty of your results.

When breaking new ground, there are probably still many gaps in the knowledge base that need to be filled. A good follow-up statement for this type of limitation is to describe what, based on these results, the next steps would be to build a stronger overall evidence base.

It’s possible that your study will have a fairly “critical” flaw (usually in the study design) that decreases confidence in your findings.

Other experts will likely notice this (in peer review or perhaps on a preprint server, they should notice it), so it’s best to explain why this error or flaw occurred.

You can still explain why the study is worth repeating or how you plan to retest the phenomenon. But you may need to temper your publication goals if you still plan to publish your work.

No one expects science to be perfect the first time and while your peers can be highly critical, no one’s work is beyond limitations. This is important to keep in mind.

Edanz experts can help by giving you an Expert Scientific Review and seeking out your limitations.

Our knowledge base is built on uncovering each piece of the puzzle, one at a time, and limitations show us where new efforts need to be made. Much like peer review , don’t think of limitations as being inherently bad, but more as an opportunity for a new challenge.

Ultimately, your limitations may be someone else’s inspirations. Include them in your submission when you get published in the journal of your choice .