- Monthly Review Essays

- Climate & Capitalism

- Money on the Left

Lessons from the Vietnam War

John Marciano is professor emeritus of education at the State University of New York, Cortland, and a longtime activist, teacher, and trade unionist.

This article is adapted from The American War in Vietnam: Crime or Commemoration? (Monthly Review Press, 2016).

The Vietnam War was an example of imperial aggression. According to historian Michael Parenti: “Imperialism is what empires are all about. Imperialism is what empires do,” as “one country brings to bear…economic and military power upon another country in order to expropriate [its] land, labor, natural resources, capital and markets.” Imperialism ultimately enriches the home country’s dominant class. The process involves “unspeakable repression and state terror,” and must rely repeatedly “upon armed coercion and repression.” The ultimate aim of modern U.S. imperialism is “to make the world safe” for multinational corporations. When discussing imperialism, “the prime unit of analysis should be the economic class rather than the nation-state.” 1

U.S. imperial actions in Vietnam and elsewhere are often described as reflecting “national interests,” “national security,” or “national defense.” Endless U.S. wars and regime changes, however, actually represent the class interests of the powerful who own and govern the country. Noam Chomsky argues that if one wishes to understand imperial wars, therefore, “it is a good idea to begin by investigating the domestic social structure. Who sets foreign policy? What interest do these people represent? What is the domestic source of their power?” 2

The United States Committed War Crimes, Including Torture

The war was waged “against the entire Vietnamese population,” designed to terrorize them into submission. The United States “made South Vietnam a sea of fire as a matter of policy, turning an entire nation into a target. This is not accidental but intentional and intrinsic to the U.S.’s strategic and political premises.” In such an attack “against an entire people…barbarism can be the only consequence of [U.S.] tactics,” conceived and organized by “the true architects of terror,” the “respected men of manners and conventional views who calculate and act behind desks and computers rather than in villages in the field.” 3 The U.S. abuse of Vietnamese civilians and prisoners of war was strictly prohibited by the Geneva Convention, which the United States signed. U.S. officials and media pundits continue to assert that torture is a violation of “our values.” This is not true. Torture is as American as apple pie, widely practiced in wars and prisons.

Washington Lied

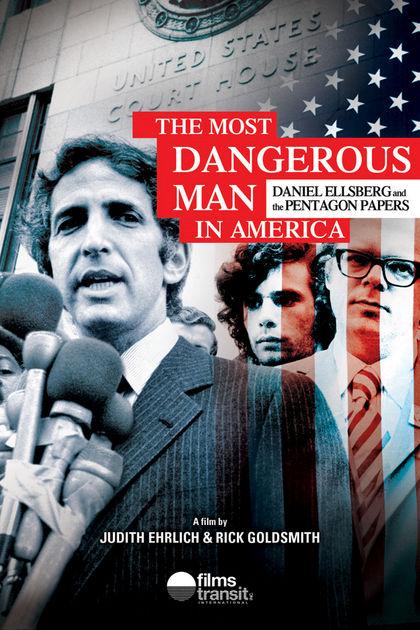

The war depended on government lies. Daniel Ellsberg exposed one such lie that had a profound impact on the eventual course of the conflict: the official story of the Tonkin Gulf crisis of August 1964. President Johnson and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara told the public that the North Vietnamese, for the second time in two days, had attacked U.S. warships on “routine patrol in international waters”; that this was clearly a “deliberate” pattern of “naked aggression”; that the evidence for the second attack, like the first, was “unequivocal”; that the attack had been “unprovoked”; and that the United States, by responding in order to deter any repetition, intended no wider war. All of these assurances were untrue. 4

The War Was a Crime, Not Just a Mistake

Since the end of the war in 1975, there has been a concerted effort by U.S. officials, the corporate media, and influential intellectuals to portray U.S. actions as a “noble cause” that went astray. American military scholar and historian Christian Appy profoundly disagrees, arguing that the findings of the Pentagon Papers and other documents provide “ample evidence to contradict this interpretation…. The United States did not inadvertently slip into the morass of war; it produced the war quite deliberately.” 5

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Condemned the War—and Was Vilified For It

In a historic speech at Riverside Church in Manhattan in April 1967, Dr. King courageously confronted bitter and uncomfortable truths about the war and U.S. society: “I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today—my own government.” 6

King’s magnificent speech, relatively unknown in the United States today, provoked an immediate backlash from the political and corporate media establishment and from civil rights leaders. Life magazine denounced it as “demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi.” A Harris poll taken in May 1967 revealed that 73 percent of Americans opposed his antiwar position, including 50 percent of African Americans. 7 The New York Times strongly condemned King, calling his effort to link civil rights and opposition to the war a “disservice to both. The moral issues in Vietnam are less clear-cut than he suggests.” The Washington Post claimed that some of his assertions were “sheer inventions of unsupported fantasy,” and that King had “diminished his usefulness to his cause, to his country and to his people.” 8

The Media Did Not Oppose the War, Only How It Was Fought

The assertion that the mainstream media opposed and undermined the war effort is one of the great myths of the Vietnam conflict. They endorsed U.S. support of French colonialism and only emerged as tactical critics of the war after the Tet Offensive in early 1968. The corporate media never challenged the fundamental premises of this imperial war.

The First Antiwar Protests Came from the Merchant Marine Services

Opposition to U.S. intervention in Vietnam did not begin with student protests in the mid-1960s, but with American merchant mariners in the fall of 1945. They had been diverted from bringing U.S. troops home from Europe to transport French troops to Vietnam to reclaim that colony. Some of these merchant mariners vigorously condemned the transport “to further the imperialist policies of foreign governments,” and a group from among the crews of four ships condemned the U.S. government for helping to “subjugate the native population of Vietnam.” 9

Some two decades later, the most important opposition to the American War would come within the military itself—including criticism by Generals Matthew Ridgeway, David Shoup, James Gavin, and Hugh Hester. The latter called the war “immoral and unjust,” an act of U.S. aggression. In 1966, Shoup stated that if the United States “had and would keep our dirty, bloody, dollar-crooked fingers out of the business of these nations so full of depressed exploited people, they will arrive at a solution of their own.” The generals all signed a New York Times antiwar advertisement in 1967, and Shoup and Hester supported and spoke at rallies sponsored by the Vietnam Veterans against the War (VVAW). Because of their efforts, the FBI investigated them under Presidents Johnson and Nixon. 10

Marine combat veteran, poet, and activist W. D. Ehrhart spoke for thousands of vets who fought in the war and came home to challenge it:

I’d learned that the eighty-eight years of French colonial rule had been harsh and cruel; that the Americans had supported Ho Chi Minh and his Vietminh guerillas with arms and equipment and training during World War Two, and in return, Ho’s forces had provided the Americans with intelligence and had helped to rescue downed American pilots; that Ho had spent years trying to gain American support for Vietnamese independence; that at the end of World War Two, the United States had supported the French claim to Indochina; that North and South Vietnam were nothing more than an artificial construction of the Western powers, created at Geneva in 1954. I’d had to learn it all on my own, most of it years after I’d left Vietnam. 11

The War Provoked Strong Working-Class Opposition

Labor studies scholar Penny Lewis counters a number of misconceptions about the anti-war movement in her Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks , particularly the false view that working-class Americans were “largely supportive of the war and largely hostile to the numerous movements for social change taking place at the time.” In fact, “Working-class opposition to the war was significantly more widespread than is remembered and parts of the movement found roots in working-class communities and politics. By and large, the greatest support for the war came from the privileged elite, despite the visible dissention of a minority of its leaders and youth.” 12

As the war deepened, so did an antiwar movement within the working class. It included the rank-and-file union members, working-class veterans who joined and helped “to lead the movement when they returned stateside; [and] working-class GIs who refused to fight; and the deserters who walked away.” Especially after the Tet Offensive in early 1968, the antiwar movement “formed deeper roots among people of color, religious communities,” and students who attended non-elite campuses. 13

The domestic antiwar movement was the largest in U.S. history, and the October 1969 Moratorium Against the War alone was the greatest single antiwar protest ever recorded in this country. The movement was deepened and strengthened by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), that in January 1966 issued a public statement against the war—a courageous dissent that nearly bankrupted it financially. SNCC called U.S. involvement “racist and imperialist.” The murder of SNCC activist and Navy veteran Sammy Younge showed that the organization’s role was not to fight in Vietnam, but to struggle within the United States for freedoms denied to African Americans. SNCC accordingly affirmed its support for draft resisters. Reflecting the national view at the time, most African Americans strongly disagreed with SNCC’s stand on the war and draft resistance. 14

Though miniscule when compared to the astronomical level of violence in Vietnam, antiwar violence by college youth received more attention from the media and the public. In fact, however, it was an extremely small part of an activist antiwar movement that “numbered more than 9,400 protest incidents recorded during the Vietnam era, as well as thousands of demonstrations, vigils, letter writing [campaigns], teach-ins, mass media presentations, articles and books [and petitioning] congressional representatives.” 15 Added to these activities was an explosion of antiwar news sources across the country, beyond college campuses. There were countless antiwar papers published by active-duty soldiers and veterans who opposed the war, such as Vietnam GI , the VVAW paper.

Appeals to Support the Troops Should Be Critically Examined

President Obama and the 2015 official commemoration have urged citizens to support and honor those who served in Vietnam—an appeal that certainly does not extend to the antiwar activists of the VVAW. This charge to support the military in Vietnam—and all wars since—implicitly asks citizens to support uncritically any U.S. conflict. As the war continued, the VVAW rejected such a view, in the face of condemnation from prominent public officials, the American Legion, and Veterans of Foreign Wars.

For example, although President Ronald Reagan called on Americans to honor the troops, he showed his true colors when it came to programs to aid those scarred by the Vietnam conflict. His “first act in office was to freeze hiring in the [Veterans] Readjustment Counseling Program. He soon moved to eliminate all Vietnam veteran outreach programs, including an employment-training program for disabled veterans.” 16

The My Lai massacre offers a concrete case to test the official charge that citizens should support the military in times of war. Kenneth Hodge, one of the U.S. soldiers who participated in the massacre, insisted years later that “there was no crime committed”:

As a professional soldier I had been taught and instructed to carry out the orders that were issued by the superiors. At no time did it ever cross my mind to disobey or to refuse to carry out an order that was issued by my superiors. I felt that they (Charlie Company) were able to carry out the assigned task, the orders, that meant killing small kids, killing women…. I feel we carried out the orders in a moral fashion, the orders of destroying the village, …killing people in the village, and I feel we did not violate any moral standards. 17

There is no bridge that can span the chasm between Hodge and those soldiers who refused orders to kill people at My Lai; and between Hodge and pilot Hugh Thompson Jr., who landed his helicopter in the midst of the massacre and saved Vietnamese who certainly would have been killed. Hodge’s defense should also be compared with journalist Jonathan Schell’s comment about My Lai: “With the report of the…massacre, we face a new situation. It is no longer possible for us to say that we did not know…. For if we learn to accept this, there is nothing we will not accept.” 18

Real support for the troops should not consist of cheap flyovers at sporting events; corporate campaigns to raise funds for veterans that are pennies on the dollar alongside vast profits from military contracts; performing empty flag-waving gestures while supporting political efforts in Washington to cut funds for wounded and disabled veterans and other needed programs; or assuring veterans that the war was a noble cause when it was not.

My Lai Was a Massacre, Not an “Incident”

The most publicized U.S. atrocity of the war, the slaughter of unarmed residents of the hamlet of My Lai in the village of Son My on March 16, 1968, was a massacre—not an “incident,” as it is called in the official Vietnam War Commemoration sponsored by the Department of Defense. It lists the death toll “at ‘more than 200,'” and singles out only Lieutenant Calley, “as if the deaths of all those Vietnamese civilians, carried out by dozens of men at the behest of higher command, could be the fault of just one junior officer.” 19

For historian Gabriel Kolko, My Lai “is simply the foot soldier’s direct expression of the…fire and terror that his superiors in Washington devise and command from behind desks…. The real war criminals in history never fire guns [and] never suffer discomfort. What is illegitimate and immoral, is the entire war and its intrinsic character.” Regarding the home front reception to the My Lai massacre, he reminds us that the “rather triumphant welcome various political and veterans organizations gave Lieutenant Calley reveals that terror and barbarism have their followers and admirers at home as well as in Vietnam.” 20

Regarding My Lai, the war, and the United States, historian Kendrick Oliver concludes: “This is not a society which really wanted to know about the violence of the war that its armed forces were waging in Vietnam.” Many Americans “perceived they had more in common with…Calley than with any of his victims…. It was the lieutenant…who became the object of public sympathy, not the inhabitants of My Lai whom he had hastened to death, and the orphans and widows he made of many of the rest.” 21

Ecocide Is an Essential Legacy of the War

The horrific and illegal chemical warfare against the Vietnamese was defined powerfully and precisely by biologist Arthur Galston: “It seems to me that the willful and permanent destruction of environment…ought…to be considered as a crime against humanity, to be designated by the term ecocide .” 22 The devastating environmental health effects of the war continue for Vietnamese and U.S. veterans. Arthur Westing, the leading U.S. authority on ecological damage during the war, addressed these effects at an Agent Orange symposium in 2002. The “Second Indochina War of 1961–1975 (the ‘Vietnam Conflict’; the ‘American War’) stands out today as the [model] of war-related environmental abuse.” 23

The U.S. Government Does Not “Hate War”—It Loves It

President Obama’s claim in his Vietnam commemoration speech—that Americans “hate war” and “only fight to protect ourselves because it’s necessary”—is the latest in a long line of fantastical pronouncements by U.S. officials. Even an elementary knowledge of U.S. wars since the founding of the nation would dispel this delusion. These include the genocidal Indian Wars that lasted more than a century until 1890; wars of aggression against Cuban, Philippine, and Puerto Rican independence struggles in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; and the overthrow of forty-one governments in Latin America between 1898 and 1994. 24 There is also Korea, Vietnam, Panama, Iraq (twice, in 1991 and 2003, in addition to genocidal economic sanctions in between), and Afghanistan, with the latter two both still underway, and many more documented in the Congressional Research Service’s important study, released in September 2014, that tallied hundreds of U.S. military interventions. As Veterans for Peace note on their website: “America has been at war 222 out of 239 years since 1776. Let that sink in for a moment.” Since the end of the shooting war in Vietnam in April 1975, virtually every calendar year has seen the presence of U.S. military forces abroad, in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe. A number of these nations have seen multiple U.S. military interventions under various presidents over the past forty years since the end of the Vietnam War. 25 The historical record, therefore, reveals a nation that is wedded to war.

Vietnamese Resistance to U.S. Aggression was Justified

Nguyen Thi Binh, head of the Vietnamese delegation to the 1968 Paris Peace Conference, declared that the war of resistance against America was “the fiercest struggle in the history of Vietnam,” forced upon a people who did not provoke or threaten the United States. During the Second World War, Vietnam “was on the side of the Allies and embedded the spirit of democracy and freedom of the Declaration of Independence of America in the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence and constitution.” Despite this fact, the United States “attempted to replace France and impose its rule over Vietnam.” The Vietnamese understood their country “was one,” and their “sacred aspiration was independence, freedom, and unification.” They always believed that they “have the right to choose the political regime for their country without foreign intervention.” 26

The History of the War Is a Struggle for Memory

A practical lesson of the war is offered by Vietnam veteran and sociologist Jerry Lembcke, author of the important book Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam , who writes that the “vast majority of Vietnam War veterans would know more about the war today if they had spent their months of deployment stateside in a classroom with Howard Zinn.” And what should be the lesson for young people who wish to understand the American war? “That the veteran…might today be a better source…had he stayed home from Vietnam and read some history books; [and] the student, whose education might be better served by reading a good history book about the war than interviewing the veteran.” 27

After every war that the United States has fought, a new chapter is added to history textbooks, one that interprets the conflict for succeeding generations. The new narratives stress the necessity of its involvement and America’s role and conduct during the war. Some describe the excesses and even the criminal behavior of the U.S. military, but never define these as such or acknowledge their central place in the conduct of the war. U.S. history textbooks essentially portray U.S. aggression against Vietnam as a failed defense of democracy and freedom; it was a “mistake” and a “tragedy,” with noble goals. The thesis that the conflict was an illegal act of state aggression is considered unworthy of critical examination. The parameters established by these texts do not allow students to consider the possibility that the Vietnamese resistance was a justifiable liberation struggle against foreign aggression and a brutally authoritarian regime.

Noam Chomsky’s conclusion on the nature of the war and its relationship to the educational system captures the essence of the past and present textbook studies. Simply replace Southeast Asia with Afghanistan or Iraq, and his thoughts in 1966 on schools and society remain accurate and relevant:

At this moment of national disgrace, as American technology is running amuck in Southeast Asia, a discussion of American schools can hardly avoid noting the fact that these schools are the first training ground for the troops that will enforce the muted, unending terror of the status quo of a projected American century; for the technicians who will be developing the means for extension of American power; for the intellectuals who can be counted on, in significant measure, to provide the intellectual justification for this particular form of barbarism and to decry the irresponsibility and lack of sophistication of those who will find all of this intolerable and revolting. 1

Forty years after the American war in Vietnam ended in 1975, the central and most critical issue is the “struggle for memory,” an ideological war over the most accurate and truthful story of the conflict. Whose ideas about the war will prevail? This struggle will help determine how we, the people, will respond to present and future U.S. international conflicts. If citizens are to understand the role of U.S. governmental and corporate elites in initiating the current endless wars, they must develop an accurate and comprehensive understanding of the history of the war in Vietnam. Such an analysis will provide the critical tools with which to counter the hyper-patriotism of the official Vietnam commemoration, whose lessons are based on the dominant and false story of U.S. beneficence: a nation forever faithful in its quest for justice that always follows a righteous path in its wartime conduct. Another story must be told: that of a decades-long reign of terror against the people of Vietnam, a shameful war that no government-sanctioned lesson or eloquent rhetoric can hide.

- ↩ Michael Parenti’s argument here is a synthesis of “ What Do Empires Do? ” 2010, http://michaelparenti.org, and Against Empire (San Francisco: City Lights, 1995), 23. Parenti documents this history in great detail in a number of other books, including The Face of Imperialism , Profit Pathology and Other Indecencies , and The Sword and the Dollar . In a note to the author, Noam Chomsky cautioned about reading the general argument about imperialism too narrowly; it was sufficient as “a general statement on imperialism, but…misleading about Vietnam. It will be read as though the US wanted to exploit Vietnam’s resources…. The concern was the usual one (Guatemala, Cuba, Nicaragua, others) that successful independent development in Vietnam might inspire others to follow the same course.”

- ↩ Noam Chomsky, Towards a New Cold War (New York: New Press, 2003), 6, 93, 98. It is a testament to the strength of the dominant view of American foreign policy that Chomsky, an internationally renowned scholar and intellectual, was virtually unknown to nearly all of the more than six thousand students I taught over the course of thirty-one years at the State University of New York, Cortland. Some had heard of him, but it was rare to find a student who had read any of his writings. In addition to Chomsky’s many books, readers should examine William Blum, Rogue State (Monroe, ME: Common Courage, 2000) and G. William Domhoff, Who Rules America? (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2013).

- ↩ Gabriel Kolko, “War Crimes and The Nature of the Vietnam War,” in Richard Falk, Gabriel Kolko, and Robert Jay Lifton, eds., Crimes of War (New York: Vintage, 1971), 412–13; Kolko, “On the Avoidance of Reality,” Crimes of War , 15.

- ↩ Daniel Ellsberg, Secrets (New York: Penguin, 2002), 12.

- ↩ Christian Appy, Working Class War (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 253.

- ↩ Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., “ Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence ,” April 4, 1967, Riverside Church, New York City, available at http://commondreams.org.

- ↩ Edward Morgan, What Really Happened to the 1960s (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2010), 76; Daniel S. Lucks, Selma to Saigon (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky Press, 2014), 203.

- ↩ New York Times , April 7, 1967; Washington Post , April 6, 1967.

- ↩ Michael Gillen, “Roots of Opposition: The Critical Response to U.S. Indochina Policy, 1945–1954,” Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, 1991, 122.

- ↩ Robert Buzzanco, “The American Military’s Rationale against the Vietnam War,” Political Science Quarterly 101, no. 4 (1986): 571.

- ↩ W. D. Ehrhart, Passing Time (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1989), 161–62.

- ↩ Penny Lewis, Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks (Ithaca, NY: ILR, 2013), 4, 7.

- ↩ Lewis, Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks , 45.

- ↩ Lewis, Hardhats, Hippies, and Hawks , 92; Lucks, Selma to Saigon , 3.

- ↩ Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS (New York: Random House, 1973), 514, 48.

- ↩ D. Michael Shafer, “The Vietnam Combat Experience: The Human Legacy,” in The Legacy: The Vietnam War in the American Imagination (Boston: Beacon, 1992), 97.

- ↩ Quoted in Michael Bolton and Kevin Sim, Four Hours in My Lai (New York: Viking, 1992), 371.

- ↩ Jonathan Schell, “Comment,” New Yorker , December 20, 1969, 27.

- ↩ Nick Turse, “ Misremembering America’s Wars, 2003–2054 ,” TomDispatch, February 18, 2014, http://tomdispatch.com.

- ↩ Kolko, “War Crimes,” 414; “Avoidance,” 12.

- ↩ Kendrick Oliver, The My Lai Massacre in American History and Memory (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2006), 8–9.

- ↩ Quoted in Erwin Knoll and Judith Nies McFadden, War Crimes and the American Conscience (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970), 71.

- ↩ Arthur Westing, “Return to Vietnam: The Legacy of Agent Orange,” lecture at Yale University, April 26, 2002; Westing, Ecological Consequences of the Second Indochina War (Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 1974), 22.

- ↩ Greg Grandin, “ The War to Start All Wars: The 25th Anniversary of the Forgotten Invasion of Panama ,” TomDispatch, December 23, 2014. See also Grandin’s excellent Empire’s Workshop (New York: Metropolitan), 2006.

- ↩ Barbara Salazar Torreon, Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798–2014 (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Office, 2014).

- ↩ Nguyen Thi Binh, “The Vietnam War and Its Lessons,” in Christopher Goscha and Maurice Vaisse, eds., The Vietnam War and Europe 1963–1973 (Brussels: Bruylant, 2003), 455–56.

- ↩ Jerry Lembcke, “ Why Students Should Stop Interviewing Vietnam Veterans ,” History News Network, May 27, 2013, http://historynewsnetwork.org.

- ↩ Noam Chomsky, “Thoughts on Intellectuals and the Schools,” Harvard Educational Review 36, no. 4 (1966): 485.

Comments are closed.

Rethinking Schools

Non-Restricted Content

Lessons of the Vietnam War

Teaching the forgotten 50th anniversary.

By Bill Bigelow

There is a startling encounter in the Vietnam war documentary, Heartsand Minds , between producer Peter Davis and Walt Rostow, former adviser to President Johnson. Davis asks Rostow why the United States got involved in Vietnam. Rostow is incredulous: “Are you really asking me this goddamn silly question?” That’s “pretty pedestrian stuff,” he complains. But after several more expressions of disgust, Rostow finally answers, “The problem began in its present phase after the Sputnik, the launching of Sputnik, in 1957, October.”

Despite Rostow’s patronizing bluster, Davis’ question is not silly at all. It’s the fundamental question that a film — or teacher — should ask about the war. What’s silly is Rostow’s answer. Sputnik? 1957?

With one blow, the former adviser erases years of history to imply that somehow the Soviet Union was behind it all.

The “present phase” caveat notwithstanding, Rostow ignores the World War II cooperation between the United States and the Viet Minh; Ho Chi Minh’s repeated requests that the U.S. acknowledge Vietnamese sovereignty; the U.S. refusal to recognize the 1945 Declaration of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam; $2 billion in U.S. military support for the restoration of French domination, including the near-use of nuclear weapons during the decisive battle of Dien Bien Phu, according to the Army’s own history of the war; and the well-documented U.S. subversion of the 1954 Geneva peace accords. All occurred before the launching of Sputnik.

Rostow’s historical amnesia is reflected in today’s major U.S. history textbooks, according to a new study by Jim Loewen of the University of Vermont [see the review of his book, LiesMyTeacherTold Me , p. 24.] Of the 12 textbooks Loewen studied, not a single one probes earlier than the 1950s to understand the origins of the war. Why was the United States at war in Vietnam, according to these texts? Loewen writes: “Most textbooks simply dodge the issue. Here is a representative analysis, from American Adventures : ‘Later in the 1950’s, war broke out in South Vietnam. This time the United States gave aid to the South Vietnamese government.’ ‘War broke out’ — what could be simpler!”

When teachers pattern our curricula after these kinds of non-explanatory explanations, we mystify the origins not just of the war in Vietnam, but of everything we teach. Students need to learn to distinguish explanations from descriptions, like “war broke out,” or “chaos erupted.” Thinking about social events as having concrete causes, constantly asking “Why?” and “In whose interests?” need to become critical habits of the mind for us and our students. It’s only through developing the tools of deep questioning that students can attempt to make sense of today’s global conflicts.

However, especially when teaching something like the war in Vietnam, bypassing explanation in favor of description can be seductive. After all, there’s so much stuff about the war in Vietnam: so many films, so many novels, short stories and poetry, so many veterans who can come in and speak to the class. These are all fine and important resources, but unless built on a foundation of causes for the war, using these can be more voyeuristic than educational; they can generate a kind of empty empathy.

The Missing Anniversary

The year 1995 is full of 50th anniversaries: the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps; the surrender of Germany, ending the war in Europe; the testing of the first atom bomb at Alamogordo, New Mexico; the first use of atomic weapons against human beings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki; the final end of World War II, with the surrender of Japan; and the birth of the United Nations. However, one anniversary likely to be overlooked in this year of remembrance also had an enormous impact

on the course of world history: the Declaration of Independence of Vietnam, announced September 2, 1945 by Ho Chi Minh. If we in the United States had spent more time considering the origins of the war, perhaps we wouldn’t experience this commemorative omission.

A video I’ve found useful in prompting students to explore a bit of the history of Vietnam and the sources of U.S. involvement is the first episode of the PBS presentation, Vietnam: A Television History [available in many libraries]. Called “Roots of a War,” it offers an overview of Vietnamese resistance to French colonialism (which began in the mid-nineteenth century) and to the Japanese occupation during World War

II. My students find the video a bit dry, so in order for students not to feel overwhelmed by information, I stop it often to talk about key incidents and issues. Some of the images are powerful: Vietnamese men carrying white-clad Frenchmen on their backs, and French picture-postcards of the severed

heads of Vietnamese resisters — cards that troops sent home to sweethearts in Paris, as the narrator tells us, inscribed, “With kisses from Hanoi.” The goal of French colonialism is presented truthfully and starkly: “To transform Vietnam into a source of profit.” The narrator explains, “Exports of rice stayed high even if it meant the peasants starved.” Significantly, many of those who tell the story of colonialism and the struggle against it are Vietnamese. Instead of the nameless generic peasants of so many Hollywood Vietnam war movies, here, at least in part, Vietnamese get to tell their own stories.

Toward the end of the episode, Dr. Tran Duy Hung recounts the Vietnamese independence celebration in Hanoi’s Ba Dinh square following the defeat of the Japanese — and occurring on the very day of the formal Japanese surrender aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, September 2, 1945: “I can say that the most moving moment was when President Ho Chi Minh

climbed the steps, and the national anthem was sung. It was the first time that the national anthem of Vietnam was sung in an official ceremony. Uncle Ho then read the Declaration of Independence, which was a short document. As he was reading, Uncle Ho stopped and asked, ‘Compatriots, can you hear me?’ This simple question went into the hearts of everyone there. After a moment of silence, they all shouted, ‘Yes, we hear you.’ And I can say that we did not just shout with our mouths, but with all our hearts. The hearts of over 400,000 people standing in the square then.” Dr. Hung recalls that moments later, a small plane began circling overhead and swooped down over the crowd. When people recognized the stars and stripes of the U.S. flag, they cheered enthusiastically, believing its presence to be a kind of independence ratification. The image of the 1945 crowd in Northern Vietnam applauding a U.S. military aircraft offers a poignant reminder of the historical could-have-beens.

Although this is not the episode’s conclusion, at this point I stop the video. What will be the response of the U.S. government? Will it recognize an independent Vietnam or stand by as France attempts to reconquer its lost colony? Or will the United States even aid France in this effort? This is a choice-point that would impact the course of human history, and through role play I want to bring it to life in the classroom. Of course, I could simply tell them what happened, or give them materials to read. But a role play that brings to life the perspectives of key social groups, allows students to experience , rather than just hear about aspects of this historical crossroads. As a prelude, we read the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence, available in the fine collection, Vietnam and America:A Documented History , edited by Marvin Gettleman, Jane Franklin, Marilyn Young, and H. Bruce Franklin [New York: Grove Press, 1985], as well as in Vietnam: A History in Documents , edited by Gareth Porter [New York: New American Library, 1981].

Role Playing a Historic Choice

I include here the two core roles of the role play: members of the Viet Minh, and French government/business leaders. In teaching this period, I sometimes include other roles: U.S. corporate executives, labor activists, farmers, and British government officials deeply worried about their own colonial interests, as well as Vietnamese landlords allied with the French — this last, to reflect the class as well as anti-colonial dimension of the Vietnamese independence movement.

Each group has been invited to a meeting with President Truman — which, as students learn later, never took place — to present its position on the question of Vietnamese independence. I portray President Truman and chair the meeting.

Members of each group must explain:

- How they were affected by World War II?

- Why the United States should care what happens in Vietnam, along with any responsibilities the U.S. might have (and in the case of the French, why the United States should care what happens in France)?

- Whether the United States should feel threatened by communism in Vietnam, or in the case of the French leaders, France?

- What they want President Truman to do about the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence — support it, ignore it, oppose it?

- Whether the United States government should grant loans to the French, and if it supports loans, what strings should be attached?

Obviously, the more knowledge students have about pre-1945 Vietnam, France, and World War II in general, as well as the principles of communism, the more

sophisticated treatment they’ll be able to give to their roles. [An excellent film on U.S. Communism, Seeing Red , produced by Jim Klein and Julia Reichert, is available from New Day Films and can be helpful.] However, even without a thorough backgrounding, the lesson works fine to introduce the main issues in this important historical choice-point.

To work students into their roles, I may ask them to create an individual persona by writing an interior monologue — one’s inner thoughts — on their post-war hopes and fears. Students can read these to a partner, or share them in a small group.

In the meeting/debate, students-as-Viet Minh argue on behalf of national independence. They may remind Truman of the help that the Viet Minh gave to the Allies during World War II, denounce French colonialism, and recall the United States’ own history in throwing off European colonialism.

The students-as-French counter that the would-be Vietnamese rulers are Communists and therefore a threat to world peace. Like the Vietnamese, the French remind Truman that they too were World War II allies and are now in need of a helping

hand. In order to revive a prosperous and capitalist France, they need access to the resources of Vietnam. Because the United States has an interest in a stable Europe, one that is non-communist and open for investment, they should support French efforts to regain control of Vietnam.

I play a cranky Truman, and poke at inconsistencies in students’ arguments. I especially prod each side to question and criticize the other directly. [For suggestions on conducting a role play, see “Role Plays: Show, Don’t Tell,” in the Rethinking Schools publication, Rethinking Our Classrooms:Teaching for Equity and Justice , pp. 114-116.]

The structure of the meeting itself alerts students to the enormous power wielded by the United States government at the end of World War II, and that the government was maneuvering on a global playing field. As students will come to realize, U.S. policymakers would not decide the Vietnam question solely, if at all, on issues of morality, or even on issues related directly to Vietnam. As historian Gabriel Kolko writes in The Roots of American Foreign Policy , “even in 1945 the United States regarded Indo-China almost exclusively as the object of Great Power diplomacy and conflict. . . [A]t no time did the desires of the Vietnamese themselves assume a role in the shaping of United States policy.”

Following the whole-group debate, we shed our roles to debrief. I ask: What were some of the points brought out in discussion that you agreed with? Do you think Truman ever met with Vietnamese representatives? What would a U.S. president take into account in making a decision like this?

What did Truman decide? What powerful groups might seek to influence Vietnam policy? How should an important foreign policy question like this one be decided?

To discover what Truman did and why, we study a timeline drawn from a number of books on Vietnam, including the one by Kolko mentioned above, his Anatomy of a War [Pantheon, 1985], Marilyn Young’s The Vietnam Wars:1945-1990 [HarperCollins, 1991], The Pentagon Papers [Bantam, 1971], as well as excerpts from Chapter 18 of Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States [HarperCollins, 1980]. It’s a complicated history involving not only the French and Vietnamese, but also Chiang Kai-shek’s nationalist Chinese forces, the British, and Japanese. What becomes clear is that at the close of World War II, the United States was in a position to end almost 100 years of French domination in Vietnam. The French government was desperate for U.S. aid and would not have defied an American decision to support Vietnamese independence. Nevertheless, U.S. leaders chose a different route, ultimately contributing about $2 billion to the French effort to reconquer Vietnam.

While a separate set of decisions led to the commitment of U.S. troops in Vietnam, the trajectory was set in the period just after World War II. The insights students glean from this role play inform our study of Vietnam throughout the unit. We follow-up with a timeline tracing U.S. economic and military aid to France; a point-by-point study of the 1954 Geneva agreement ending the war between the French and Vietnamese; and from the perspective of peasants and plantation laborers in southern Vietnam, students evaluate the 1960 revolutionary platform of the National Liberation Front. Students later read a number of quotations from scholars and politicians offering opinions on why we fought in Vietnam. Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon assert in almost identical language that the United States was safeguarding freedom and democracy in South Vietnam. President Kennedy: “For the last decade we have been helping the South Vietnamese to maintain their independence.” Johnson: “We want nothing for ourselves — only that the people of South Vietnam be allowed to guide their own country in their own way.” Students ponder these platitudes: If it were truly interested in Vietnam’s “independence,” why did the U.S. government support French colonialism?

On April 7, 1965, President Johnson gave a major policy speech on Vietnam at Johns Hopkins University. Here Johnson offered a detailed explanation for why the United States was fighting in Vietnam [included in TheViet-Nam Reader , edited by Marcus Raskin and Bernard Fall, pp. 343-350]. Embedded in the speech was his version of the origins of the war. As Johnson, I deliver large portions of the speech, and students as truth-seeking reporters pepper me with critical questions and arguments drawn from the role play and other readings and activities.

Following this session, they write a critique of LBJ’s speech. Afterwards, we evaluate how several newspapers and journals — The New York Times , The Oregonian , I.F. Stone’s Weekly — actually covered President Johnson’s address.

None of the above is meant to suggest the outlines of a comprehensive curriculum on the Vietnam war. Here, I’ve concentrated on the need for engaging students in making explanations for the origins of U.S. government policy toward Vietnam. But policy choices had intimate implications for many people’s lives, and through novels, short stories, poetry, interviews, and their own imaginations, students need also to explore the personal dimensions of diplomacy and political economy. And no study of the war would be complete without examining the dynamics of the massive movement to end that war. Especially when confronted with the horrifying images of slaughtered children in a film like Remember My Lai , or the anguished sobs of a young Vietnamese boy whose father has been killed, in Hearts and Minds , our students need to know that millions of people tried to put a stop to the suffering. And students should be encouraged to reflect deeply on which strategies for peace were most effective. [See the accompanying resource suggestions.]

If we take the advice of the Walt Rostows and the textbook writers, and begin our study of the Vietnam war in the late 1950s, it’s impossible to think intelligently about the U.S. role. The presidents said we were protecting the independence of “South Vietnam.” Students need to travel back at least as far as 1945 to think critically about the invention of the country of South Vietnam that was intended to justify its needed “protection.” The tens of thousands of U.S. deaths and the millions of Vietnamese deaths, along with the social and ecological devastation of Indochina require the harsh light of history to be viewed clearly. Among the many worthy 50th anniversaries this year, perhaps we can acknowledge another one that means so much to so many.

Included in:

Volume 9, No.3

Spring 1995.

Vietnam War: 6 personal essays describe the sting of a tragic conflict

The Vietnam War touched millions of lives. Within these personal essays from people who took part in the filming of The Vietnam War , are lessons about what happened, what it meant then and what we can learn from it now.

Long ago and far away, we fought a war in which more than 58,000 Americans died and hundreds of thousands of others were wounded. The war meant death for an estimated 3 million Vietnamese, North and South. The fighting dragged on for almost a decade, polarizing the American people, dividing the country and creating distrust of our government that remains with us today.

In one way or another, Vietnam has overshadowed every national security decision since.

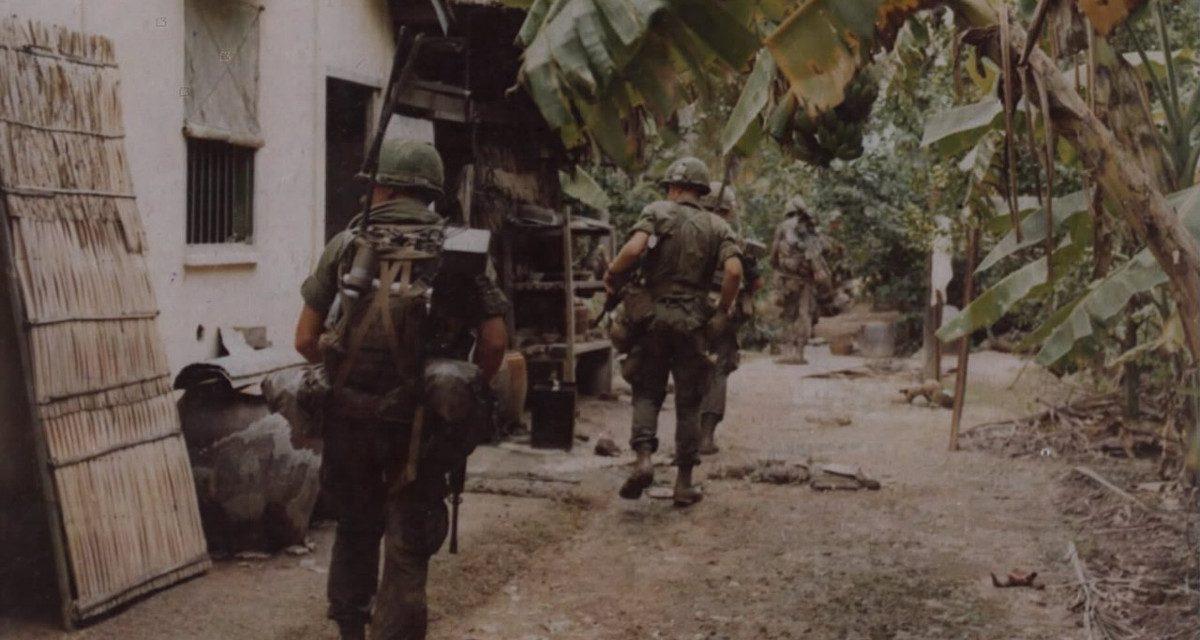

We were told that our mission was to prevent South Vietnam from falling to communism. Very lofty. But the men I led as a young infantry platoon leader and later as a company commander weren’t fighting for that mission. Mostly draftees, they were terrific soldiers. They were fighting, I realized, for each other — to simply survive their year in-country and go home.

I had grown up as an “Army brat.” To me, the Army was like a second family. In Vietnam, the radio code word for our division’s infantry companies was family . A “rucksack outfit,” my company would disappear into the jungle, moving quietly, staying in the field for weeks. We all ate the same rations and endured the same heat, humidity, mosquitoes, leeches, skin rashes, jungle itch. We were like pack animals, carrying upwards of 60 pounds of gear, water, ammunition — and even more for the radio operators and machine gunners. I was impressed by how the men endured it all, especially the draftees who had answered the call to service.

I learned much about leadership. I was once counseled by a senior officer “not to be too worried about your men.” Incredible. I was concerned about my men’s safety at all times. Even though my company lost very few, I remember each of those deaths vividly. They were all good men, in a war very few understood.

On both of my combat tours, in 1968 at Huê´ during the Tet Offensive and in 1969-70 in the triple-canopy rainforests along the Cambodian border, we fought soldiers of the North Vietnamese army. They were good light infantry; I had respect for their determination and abilities. But they were the enemy; our job was to kill or capture them.

Though we were conducting a war of attrition, we were actually fighting the enemy’s birth rate. He was prepared and determined to keep fighting as long as he had the manpower to send south.

In terms of strategy, it seemed a war out of “Alice in Wonderland.” The Ho Chi Minh Trail, the enemy’s major supply line and infiltration route, ran through Cambodia and Laos. Yet until May 1970, both of those countries were off limits to U.S. ground forces. We bombed the trail incessantly, but the enemy’s ability to move troops and equipment south never seemed to slack. We never invaded North Vietnam. As demonstrated during Tet in ’68, the enemy could control the tempo of the war when he wished. We, on the other hand, would use unilaterally declared “truce” periods and would halt bombing to signal something never clearly defined — a willingness to talk, I imagined, which the enemy ignored.

Looking back, if our strategy was intended to force the enemy to say “enough,” resulting in a stalemate situation like that at the end of the Korean War, would the South Vietnamese have been able to defend themselves, independently? Unlikely.

Would the U.S. have been willing to commit and maintain American forces in South Vietnam indefinitely? Also unlikely.

Did we learn anything from that experience, which left such an indelible mark on our national psyche? History is a harsh teacher; there are still no easy answers.

Phil Gioia entered the Army after graduating from Virginia Military Institute in 1967. He left the military in 1977 and later was mayor in Corte Madera, Calif., and worked in venture capital and the technology industry. He lives in Marin County, Calif.

Hal Kushner

When I deployed to Vietnam in August 1967, I was a young Army doctor, married five years, with a 3-year-old daughter, just potty trained, and another child due the following April. When I returned from Vietnam in late March 1973, I saw my 5-year-old son for the first time, and my daughter was in the fifth grade. In the interim, we had landed on the moon; there was women’s lib, Nixon had gone to China; Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated.

I was the only doctor captured in the 10-year Vietnam War. I was back from the dead.

We prisoners endured unspeakable horror, brutality and deprivation, and we saw and experienced things no human should ever witness. Our mortality rate was almost 50% — higher even than at the brutal Civil War prisons at Andersonville or Elmira a century earlier. I cradled 10 dying men in my arms as they breathed their last and spoke of home and family; then we buried them in crude graves, marked with stones and bamboo, and eulogized them with words of sunshine and hope, country and family. The eulogies were for the survivors, of course; they always are.

On the Fourth of July in five successive years, we sang patriotic songs, but very softly, so our captors couldn’t hear the forbidden words, and we cried. One of us had a missal issued by the Marine Corps, our only book, but our captors had torn out the pages with the American flag and The Star-Spangled Banner .

At my release in Hanoi, I was shocked by the hair and dress of the reporters there. Once home, I saw television and movies with frank profanity and sex. When I left, Lucy and Desi slept in twin beds. I left Ozzie and Harriett and returned to Taxi Driver . What had happened to my country? Why did we suffer and sacrifice?

When my aircraft crashed on Nov. 30, 1967, I collided with one planet and returned to another. The Vietnam War, which had about one-fifth of the casualties of World War II but had lasted three times as long, had changed the country as much as the greatest cataclysm in world history. It had changed forever the way we think of our government and ourselves. The country had lost its innocence — and, for a time, its confidence.

This war, which had such a great impact on my life, is a dim memory today. There are 58,000 names on that wall, and it rates but a few pages in a high school history book.

I am dismayed by how little our young people know about Vietnam, and how misunderstood it is by others. The Vietnam War is as remote to them as the War of 1812 or the War of Jenkins’ Ear. Now, 40 years later, we must try to understand.

Hal Kushner joined the Army and served as a flight surgeon in Vietnam. In 1967, he was captured by the Viet Cong after surviving a helicopter crash. He spent nearly six years as a prisoner of war. He lives in Daytona Beach, Fla.

Mai Elliott

Having lived through war and seen what it did to my family and to millions of Vietnamese, I feel grateful for the peace and stability I now enjoy in the United States.

In Vietnam, my family and I experienced what it was like to be caught in bombing and fighting, and what it was like to flee our home and survive as refugees.

During World War II, in my childhood, we huddled in shelters as Allied planes targeting Japanese positions bombed the town in the North where we lived.

In 1946, when French troops returned to try to take Vietnam back from Ho Chi Minh’s government, French soldiers attacking the village where we were taking refuge almost executed my father (who had earlier worked for the French colonial authorities).

In 1954, fearing reprisals from the communists about to enter Hanoi, we fled to Saigon with only the clothes on our backs.

In 1955, we fled again when we found ourselves caught in the fighting between the army of President Ngo Dinh Diem and the armed group he was trying to eliminate, leaving behind our home, which was about to burn to the ground in the onslaught.

In April 1975, American helicopters plucked my family out of Saigon at the last minute as communist rockets exploded nearby.

The fear we felt paled in comparison to the terror that Vietnamese in the countryside of South Vietnam experienced when bombs and artillery shells landed in their villages, or when American and South Vietnamese soldiers swept through their hamlets; or the terror my relatives in North Vietnam felt when American B-52s carpet bombed in December 1972. Yet, our brushes with war were terrifying enough.

As refugees, we could find shelter and support from middle-class friends and relatives, while destitute peasants had to move to squalid camps and depend on meager handouts and help from the government in Saigon. But we did find out, as they did, that losing everything was psychologically wrenching, and that surviving and rebuilding took fortitude of spirit.

Only those who have known war can truly appreciate peace. I am one of those people.

Mai Elliott was born in Vietnam and spent her childhood in Hanoi, where her father was a high-ranking official under the French colonial regime. Her family became divided when her older sister joined the Viet Minh resistance against French rule. In 1954, her family fled to Saigon, where Mai later did research on the Viet Cong insurgency for the RAND Corp. during the Vietnam War. She is married to American political scientist David Elliott. They live in Southern California.

Bill Zimmerman

I graduated from high school in 1958, thinking myself a patriot and aspiring to be a military pilot. Thirteen years later, I sat in a jail cell in Washington, D.C., after protesting what military pilots were doing in the skies over Vietnam.

My patriotism wilted in the South in 1963, after a short stint with the civil rights movement. Simultaneously, as the U.S. slid into war in Vietnam, skepticism nurtured in Mississippi led me to discover that we were stumbling into a quagmire.

The war escalated in 1965, and I became an ardent protester over the next six years. I was fired from two university teaching positions. But my sacrifices were trivial compared with those of young Americans forced into war, or Vietnamese civilians dying under bombs and napalm. With other antiwar activists, I anguished over them all, and seethed with rage at our inability to stop the killing. In our fury, we became more forceful, committing widespread civil disobedience.

That’s how I landed in jail in 1971, trying unsuccessfully to block traffic to shut down the federal government. But our failure that day became a turning point. Antiwar leaders realized that while we had finally convinced a majority of Americans to oppose the war, our militant tactics kept them from joining us.

We changed course. Large demonstrations ended. New organizations sprang up to educate the public and lobby Congress. The work was confrontational but did not ask participants to risk arrest. Millions took part. Richard Nixon escalated the war, but he also felt the heat from a much broader antiwar coalition. In January 1973, his administration signed the Paris Peace Accords, and over the next two years, our intense lobbying persuaded Congress to cut funding for the corrupt South Vietnamese government, leading to its collapse in 1975.

We learned that in matters of war and peace, presidents regularly lie to the American people. Every president from Truman to Ford lied about Vietnam. We learned that two presidents, Johnson and Nixon, cared more about their own political survival than the lives of the men under their command. Both sent thousands of Americans to die in a war they already knew could not be won.

We learned that our government committed crimes against humanity. Agent Orange and other chemicals were sprayed on millions of acres, leaving a legacy of cancer and birth defects.

Most important, Vietnam taught us to reject blind loyalty and to fight back. In doing so, we meet our obligation as citizens … and become patriots.

Bill Zimmerman is a Los Angeles political consultant and the author of Troublemaker: A Memoir from the Front Lines of the Sixties (Anchor Books, 2012).

Roger Harris

When I think about the Vietnam War, I am torn by personal emotions that range from anger and sadness to hope. The Vietnam War experience scarred me but also shaped and molded my perspective on life.

As a 19-year-old African American from the Roxbury section of Boston, I voluntarily joined the U.S. Marine Corps, willing to fight and die for my country. I had experienced the tough neighborhood turf battles too often prevalent in the inner city. I had a gladiator’s heart and no fear. My father, all of my uncles, including a grand-uncle who rode with Teddy Roosevelt, all served in the military. I believed that it was now my turn, and if I were to die, my mom would receive a $10,000 death benefit and be able to purchase a house. I saw the war in Vietnam as a win-win situation.

In Vietnam, I served with G Company, 2nd Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment of the 3rd Marine Division. We were called the “Hell in a Helmet” Marines. We operated in I Corps, Quang Tri Province, mainly north of Dong Ha at the Demilitarized Zone, in hot spots called Con Thien, Gio Linh, Camp Carroll and Cam Lo. I vividly remember trembling with fear from the incoming shells in the mud-filled holes at Con Thien, wishing the shelling would stop and we could fight hand-to-hand. I remember those feelings like it was yesterday.

I, along with others, witnessed deaths unimaginable. We picked up the pieces of Marine bodies obliterated by direct hits. We stacked green body bags. I often wondered why others died and I lived.

I become angry when I think about the very young lives that were lost in Vietnam and the Gold Star families who have suffered. I am saddened by the sacrifices of true heroes and the disrespect that was shown to those who were fortunate enough to come home.

When I returned from Vietnam it was March 1968 in the midst of the civil rights movement. I landed at Boston’s Logan Airport in my Marine Corps Alpha Green uniform, with the medals and ribbons I had earned proudly displayed. I approached the sidewalk to catch a taxi, hoping that I wasn’t dreaming and would not awaken back at Camp Carroll to another bombardment.

Six taxicabs passed me by and drove off. I didn’t realize what was happening until the state trooper stepped in and told the next driver, “You have got to take this soldier.” The driver, who was white, looked up at us through the passenger side window and said, “I don’t want to go to Roxbury.”

That was my initial welcome home.

I now have an appreciation for the gift of life. Since returning home and completing college, I have devoted 42 years working in Boston schools. I see it as a tribute to my fellow Marines who paid the ultimate sacrifice.

I am very proud to have served my country as a United States Marine.

I am also very proud of the young men and women who continue to volunteer to join the armed services of our country.

Roger Harris enlisted in the Marines and served in Vietnam in 1967 and 1968. Afterward, he worked in the Boston public school system for more than 40 years. He lives in New York and Boston.

Eva Jefferson Paterson

This summer, I attended the 50th reunion of my high school class in Mascoutah, Ill., across the Mississippi River from St. Louis. My dad was a career Air Force man and was stationed at Scott Air Force Base nearby in 1960.

During dinner, before we rocked out to the Beach Boys and Stevie Wonder, a group of us talked about the war in Vietnam. The men remembered the draft system that required all young men to register to serve in the military. While I was in college at Northwestern from 1967 to 1971, a draft lottery was established. Numbers were drawn out of a big bin — similar to the one used for weekly state lotteries — corresponding to the days of the year. If your birthday corresponded to the first number drawn, your draft number was 1, and you were virtually certain to be drafted and sent to war. Most men from that period remember their number.

Some at our reunion had felt that it was their patriotic duty to serve; others were just delighted that their lottery numbers were above 300 and they were unlikely to be drafted. Few of us were anti-war at that time; I fully supported the war. My dad was sent to Cam Rahn Bay and Tan Son Nhut air force bases in Vietnam in 1966, my senior year in high school.

I remember being a freshman in college and actually saying to classmates who opposed to the war, “We have to support the war because the president says the war is good, and we must support the president.” Yikes! I changed my views as I got the facts.

Much of the fervor of the anti-war movement was fueled by the slogan “Hell no, we won’t go!” There was righteous indignation about the war, but fear was a strong motivator.

Now the burden of serving in wars falls on a very small percentage of the population, one that likely mirrors the patterns in the Vietnam era, with predominantly poor white, black and Latino men and women along with those who come from military backgrounds. It would be great to have a national discussion about this, but I fear our country is quite comfortable letting poor men and women and people of color and their families bear the burden of war.

Eva Jefferson Paterson grew up on air force bases and enrolled in Northwestern University in 1967, where she became student body president and politically active against the war. A civil rights attorney, she now runs the Equal Justice Society in Northern California.

U.S. general on Vietnam War: ‘This was some enemy’

Vietnam War: A timeline of U.S. entanglement

Politics & Economy

Lessons from the việt nam war (part 1).

Published on

Lessons from the Việt Nam war ( Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 )

Lessons? For whom? They are different for the different parties. An American might be tempted to fix on who “lost” Vietnam – Congress, the executive, the military or the media. A South Vietnamese would surely name the U.S. pullout as a major factor in his country’s defeat and draw some obvious conclusions. As for the victorious North Vietnamese, Foreign Minister Nguyễn Cơ Thạch once gave an arrogant reply to Robert McNamara’s proposal for a lessons-learned symposium: “We won the war; why would we need to learn any lesson from it?” Yet the Communists, it can be said, lost the peace for the first decade after the war ended in 1975, because they suffered an embargo, were denied normalization with the U.S., and presided over a backward country that kept their people’s lives miserable for many years in comparison with other Southeast Asian nations.

For the Communists, too, there are lessons to be learned. Despite an autocratic regime which does not tolerate political dissent, and which abuses human rights, perhaps they have learned some lessons. According to the World Bank in 2018, for example:

“Vietnam’s development record over the past 30 years is remarkable. Economic and political reforms under Đổi Mới [an economic reform program], launched in 1986, have spurred rapid economic growth and development and transformed Vietnam from one of the world’s poorest nations to a lower middle-income country.” [i]

Despite the complexities, I will try to answer the lessons-learned question as a conscientious historian who was a member of South Vietnamese society and is now a grateful U.S. citizen, and as a person who looks back at his motherland with his best wishes for the people there, even as he criticizes certain Vietnamese government policies. I will try to take the long view of history.

I see five lessons from the Vietnam War of 1960 to 1975, so called to distinguish it from the 1945 to 1954 Indochina War.:

- First, changing national interests in the Vietnam war led to drastic changes in the war’s nature and the strategy needed to fight it successfully.

- War should end with a negotiated peace, and with a political solution that sees an end to the intransigence that is appropriate for war but not for peace.

- The people are the final arbiter on a war’s conduct. War should be referred to the people as the ultimate arbiter. War should not be between armed forces directed solely by generals and their leaders, but should be supported by the population as a whole, who should be consulted when war is declared and when peace is negotiated.

- If peace is to be enduring, war should end with reconciliation.

- South Vietnamese and American Presidential leadership was one factor in the Vietnam War’s outcome.

Hindsight, of course, makes the war’s lessons easier to understand. But a scholar’s well-researched views on the lessons of history can still serve policy-makers well, even during urgent deliberations, because they can enable sound solutions with fewer missteps. Confucius, Sun Yu, Aristotle and others contributed by their advice to wise statecraft, just as modern European and American governments benefit from the work of think tanks and universities. Thus, the utility of the exercise we are engaged in today. Here are my five lessons from the Vietnam War:

- The first lesson: changing national interests in the Vietnam war led to drastic changes in the war’s nature and the strategy needed to fight it successfully. In Vietnam, a civil war became uncontrollable because it became an internationalized proxy war, with outside powers intervening to suit their interests, and with the United States then abandoning the fray because its interests had changed .The saying of Lord Palmerston “nations have no permanent friends, only permanent interests” has to be modified as “nations have no permanent friends and only a few permanent interests” . [ii]

Vietnam’s protracted, bloody Communist-nationalist civil war became an internationalized conflict promoted by the two big power blocs, and the two sides in the small country of Vietnam were touted as a vanguard of the Socialist Bloc and the bulwark of the Free World. Both sides depended on the big powers’ political, military and economic support. Once the United States started cooperating with China after Kissinger’s and Nixon’s trips to Beijing, the Americans had no more national security interest in devoting resources to defend South Vietnam.

So the U.S. abandoned South Vietnam. It made many concessions to North Vietnam (the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, or DRV) in the Paris Peace Accords of 1973, agreeing to a “leopard skin” ceasefire in South Vietnam (the Republic of Vietnam, or RVN) that left North Vietnamese troops in place, jeopardizing the South’s survival, and aiming to

bring home American troops and prisoners of war to satisfy the American public. At the same time, the U.S. failed to replace lost South Vietnamese arms and ammunition on a one-for-one basis, as promised, or even to permit South Vietnam to use the American Aid Fund (Quỹ Đối Giá) to pay the salaries of its soldiers and police.

When North Vietnam’s all-out invasion caused the South to collapse in 1975, Secretary of State Kissinger hid from Congress the promise of President Nixon in his letters to President Thiệu to come to the rescue of South Vietnam with B52 bombing and arms aid; thus, both Congress and President Ford talked at the end only about the evacuation of the Americans from Vietnam. U.S Ambassador Graham Martin, visiting Washington at that time, condemned the American stance. “I think all over the world, everyone has reached a conclusion very harmful to us. That is it would be better to be an ally of Communism than to have the woe of being an ally of the United States.”

The South Vietnamese leaders, of course, should have been aware long before 1975, of the impermanency of big-power support and an eventual U.S. withdrawal due to changing national interest. The South Vietnamese leadership might have guessed that although in 1954 the U.S. wanted to replace France in South Vietnam as part of the containment policy against Communist encroachment in Asia, and although the Americans had supported the Ngô Đình Diệm regime as a “bulwark against Communism in Southeast Asia” and called President Diệm the “Churchill of Vietnam,” in later years there would likely be an American disengagement due to war weariness among the public and the surging anti-war movement. The result was President Johnson’s loss of hope and his decision not to run for re-election in 1968.

I began around that time to express, as a scholar-professor, my worry of the impact of decreased United States support for relevant South Vietnamese officials, such as the colonels and generals who studied at the National Defense College in Sài Gòn. [iii]

With the U.S. disengagement and drastically fewer supplies, the South Vietnamese had to face by themselves the continued civil war waged by the Vietnamese Communists, who launched their final offensive with maximum assistance in arms and transportation from China and the Soviet Union. After the resignation of President Thiệu in late April 1975, the successive South Vietnamese governments of Trần Văn Hương and Dương Văn Minh tried to negotiate a cease-fire, as if the civil war could be settled among “Vietnamese brothers,” with the encouragement and good offices of French Ambassador Merillon, trying to carry on for the fading Americans.

But the victorious North Vietnamese forced the Dương Văn Minh government to accept unconditional surrender on April 30, 1975. The political compromise that Thiệu could have pursued with the signing of the Paris Accords in 1973 was no longer available in the face of the now-lopsided imbalance of power (Thiệu himself had previously said that South Vietnam’s military potential had decreased by 60 percent). The South Vietnamese were now aiming mainly at a short humanitarian interregnum for those who feared for their lives under the Communists to leave Vietnam, as in 1954, when

hundreds of thousands of refugees moved from the North to South Such a cease-fire was also meant to avoid the burial of Sài Gòn under a sea of firepower (biển lửa) at the hands of Communist troops.. [iv]

The Americans, even after abandoning South Vietnam as a result of their changing view of their national strategic interests, did not abandon their humanitarian instincts. In 1975, President Ford proposed to Congress that the U.S. fund the rescue of Vietnamese refugees from inside Vietnam or from the South China Sea, and bring them halfway around the world to the United States, welcoming them to their second homeland at a time when they might have been regarded as simply the flotsam and jetsam of the Vietnam War. For this, Vietnamese in the United States will always thank the American people.

On the issue of whether the Vietnam War was a civil war or an international war by proxy, the answer is not a simple one. It was first a civil war, beginning, from 1945 and before the French attempted to return to Indochina. Then, gradually, it was internationalized by the British, the Nationalist Chinese, the French, the Americans and finally the People’s Republic of China, all injecting into Indochina their concern for their own national interests. Finally, after the 1973 Paris Peace Accords and the withdrawal of American troops and the return of American prisoners, the war returned to its civil-war status.

After the Việt Minh under Hồ Chí Minh seized power in August 1945, there was, early in September, some friction between the Việt Minh and the Vietnamese Nationalist forces. The latter accused the Việt Minh of being Communists; the Việt Minh in turn denounced their opponents — the Việt Nam Cách mệnh Đồng minh Hội (VNCMĐMH, or Vietnam Revolutionary Alliance) and the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (VNQDĐ, or Vietnam Nationalist Party) — as reactionaries. These Nationalist forces planned to rely on the support of China’s Kuomintang (the Nationalist Party of Chiang Kai Shek) – support they had enjoyed since their exile to China after the failed rebellion of Nguyễn Thái Học in 1930 — in their plot to overthrow the Provisional Coalition Government of Vietnam (Chính phủ Liên hiệp Lâm thời Việt Nam), formed by Hồ Chí Minh on January 1, 1946, even though they already had a few representatives inside that government.

But these Nationalist parties could not carry out their plan; they lacked unity and had no popular base inside Vietnamese society due to their years in exile. They had only the hoped-for support of the corrupt Chinese generals who were coming to disarm the Japanese. Moreover, in organizing demonstrations and countering propaganda, the Vietnamese Nationalists were less skilled than the Việt Minh, who had abundant experience in these matters since Hồ Chí Minh, with the approval of Nationalist Chinese General Zhang Fakui, returned from China to Vietnam in 1941 (under the name of the Vietnam Revolutionary Alliance, of which the Việt Minh was a member).

Moreover, the Việt Minh had the support of Chinese Nationalist generals Lu Han and Tieu Van, whom they bribed with opium and gold collected from the people, and these

Chinese generals forced the Vietnamese Nationalists to stay, albeit reluctantly, in the Communist-dominated Provisional Coalition Government of Vietnam. The Việt Minh also had support from the Third Communist International and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the wartime intelligence agency of the United States. The Việt Minh organized meetings, marches and exhibitions with pictures of their cadre killed by the Nationalists.

There was some restraint. A Communist party member asked Hồ Chí Minh, “Dear Uncle, why let those murderous traitors live? Please just give the order and we will liquidate all of them in one night.” Ho just smiled. ”If there was a mouse in this room, would you throw a stone at it or try to catch it? Using a stone will break precious things. To achieve great work, we must have farsightedness.”

The Nationalist-Communist friction might conceivably have stopped right there, allowing Hồ Chí Minh and the leaders of the Nationalist parties to avoid civil war. In previous times, as exiles in China, the two had shared dangers, and Nationalist leaders Nguyễn Hải Thần and Vũ Hồng Khanh had helped save the life of Hồ Chí Minh by intervening in Liuzhou, China, with the Nationalist Chinese general who detained him. After capturing power in the August 1945 Revolution, Hồ Chí Minh tried to win the cooperation of the Nationalists for the new government before the returning French sowed disunion.

Hồ embraced Nguyễn Hải Thần of the Vietnam Revolutionary Alliance (Việt Nam Cách Mệnh Đồng Minh Hội) and implored the Nationalist parties to cooperate with him. The Provisional Coalition Government of Vietnam included representatives of the Nationalists, such as Vũ Hồng Khanh of the Vietnam Nationalist Party (Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng, or VNQDĐ), Nguyễn Tường Tam of the Đại Việt (Greater Vietnam) group, and Nguyễn Hải Thần of the Vietnam Revolutionary Alliance. The government, if coupled with Hồ Chí Minh ‘s restraining his Communist cadres from assassinating the Nationalist leaders, could have avoided the civil war. [v]

Unfortunately, later in 1946, while Hồ Chí Minh was attending the Fontainebleau Conference in France and at the same time trying to invite Nationalist intellectuals in France to come home to help Vietnam, lower-level Communist leaders back in Vietnam, such as Võ Nguyên Giáp, then Minister of Interior), ordered Việt Minh assassination squads (Bạn ám sát) to kill the Nationalists and destroy their headquarters and hinterland bases. By that time, the Nationalists no longer had the protection of the Nationalist Chinese generals. The Fontainebleau Agreements were a proposed arrangement between France and the Vietminh, made in 1946 before the outbreak of the First Indochina War. The agreements affiliated Vietnam under the French Union. At these meetings Ho Chi Minh pushed for Vietnamese independence, but the French would not agree to this proposal.

In the North, the Nationalist leaders who were killed or made to disappear were Ly Dong A, and Khai Hung and Truong Tu Anh, who set the example of an ascetic life and who slept in a bed made out of a window, according to his assistant, Bùi Tường Huân, who was later a Sài Gòn Law School professor), As for Vũ Hồng Khanh and Nguyễn Hải Thần, they had to flee to China.

In the South, leaders of the Trotskyite Fourth International such as Phan Văn Hùm, Tạ Thu Thâu , Lương Đức Thiệp, Phan Văn Chánh, and Trần Văn Thạch were killed or made to disappear. Non-Communist leaders were also liquidated. These included Hồ Vân Nga, Huỳnh Vân Phương, Dương Văn, Hồ Vĩnh Ký, Henriette Bùi Quang Chiêu, and Huỳnh Phú Sổ and other Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo notables. When the South’s National Assembly met on October 28, 1946, only 291 of the 444 representatives were present, and only 37 of the 70 representatives of the Vietnam Nationalist Party and the Vietnamese Revolutionary Alliance came, the others having been arrested. Later on, the 34 attending members also disappeared. Consequently, the Nationalist parties took an anti-Communist path. Some ran for cover (“chùm chăn”) i.e., became inactive, and, later, many adopted the Bảo Đại solution, joining the camp of the ex-Emperor.

I cite this long list of victims of the Việt Minh’s liquidation campaign to provide evidence for an objective historical evaluation of the Leninist terrorist strategy the Communists used to monopolize political power, which was the root cause of Vietnam’s civil war and involved the loss of leaders who could have contributed to the nation’s development.

This terrorist strategy was not necessary for the Việt Minh ‘s ascendancy, which could have been achieved via electoral majority — as in Hitler’s takeover of the Weimar regime or Putin’s hold on power. The terrorist strategy only damaged the Việt Minh ‘s status as the standard-bearer for Vietnam’s struggle for independence against the French. After many French provocations, it was only on December 28, 1946, that the Vietnam Resistance Government, the successor to the Provisional Coalition Government, withdrew from Hanoi into the hinterland.)