Causes of the Latin American Revolution

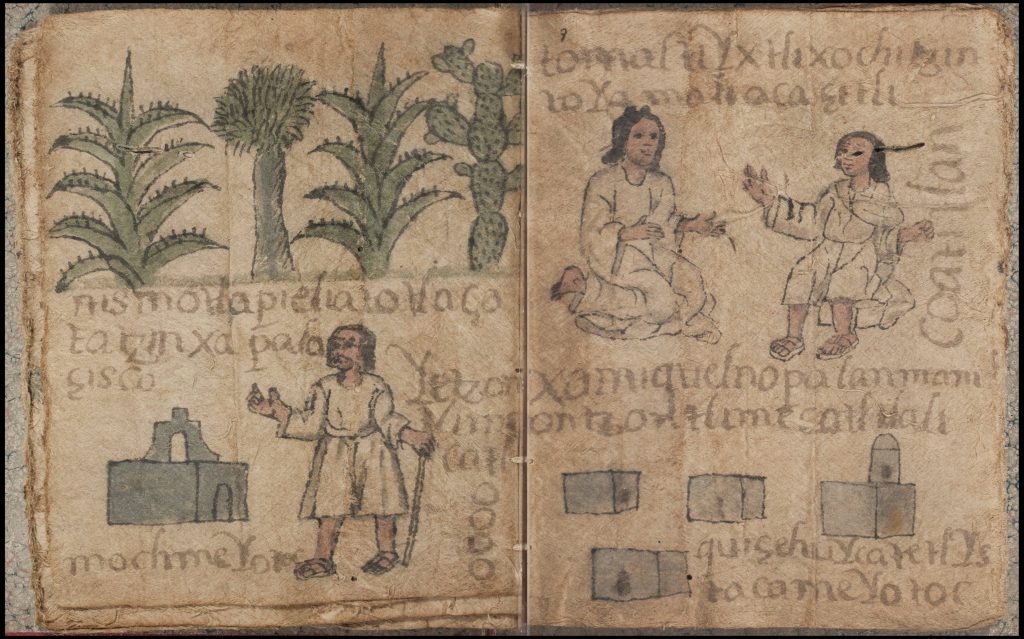

- History Before Columbus

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Caribbean History

- Central American History

- South American History

- Mexican History

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

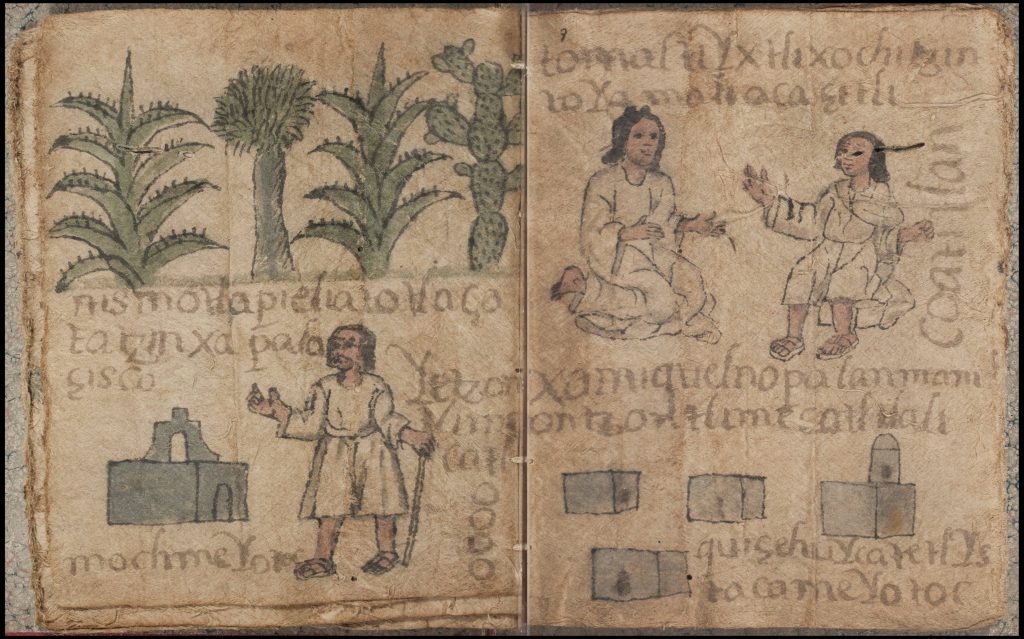

As late as 1808, Spain's New World Empire stretched from parts of the present-day western U.S. to Tierra del Fuego in South America, from the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean. By 1825, it was all gone, except for a handful of islands in the Caribbean—broken into several independent states. How could Spain's New World Empire fall apart so quickly and completely? The answer is long and complicated, but here are some of the essential causes of the Latin American Revolution.

Lack of Respect for the Creoles

By the late eighteenth century, the Spanish colonies had a thriving class of Creoles (Criollo in Spanish), wealthy men and women of European ancestry born in the New World. The revolutionary hero Simon Bolivar is a good example, as he was born in Caracas to a well-to-do Creole family that had lived in Venezuela for four generations, but as a rule, did not intermarry with the locals.

Spain discriminated against the Creoles, appointing mostly new Spanish immigrants to important positions in the colonial administration. In the audiencia (court) of Caracas, for example, no native Venezuelans were appointed from 1786 to 1810. During that time, ten Spaniards and four Creoles from other areas did serve. This irritated the influential Creoles who correctly felt that they were being ignored.

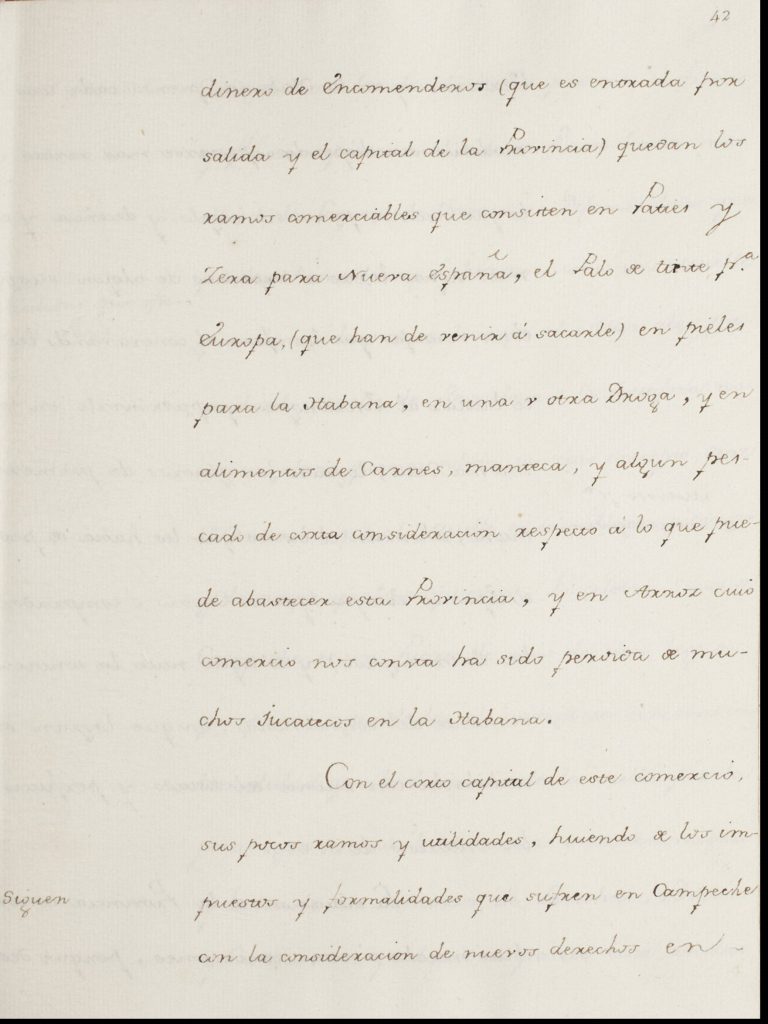

No Free Trade

The vast Spanish New World Empire produced many goods, including coffee, cacao, textiles, wine, minerals, and more. But the colonies were only allowed to trade with Spain, and at rates advantageous for Spanish merchants. Many Latin Americans began selling their goods illegally to the British colonies and, after 1783, U.S. merchants. By the late 18th century, Spain was forced to loosen some trade restrictions, but the move was too little, too late, as those who produced these goods now demanded a fair price for them.

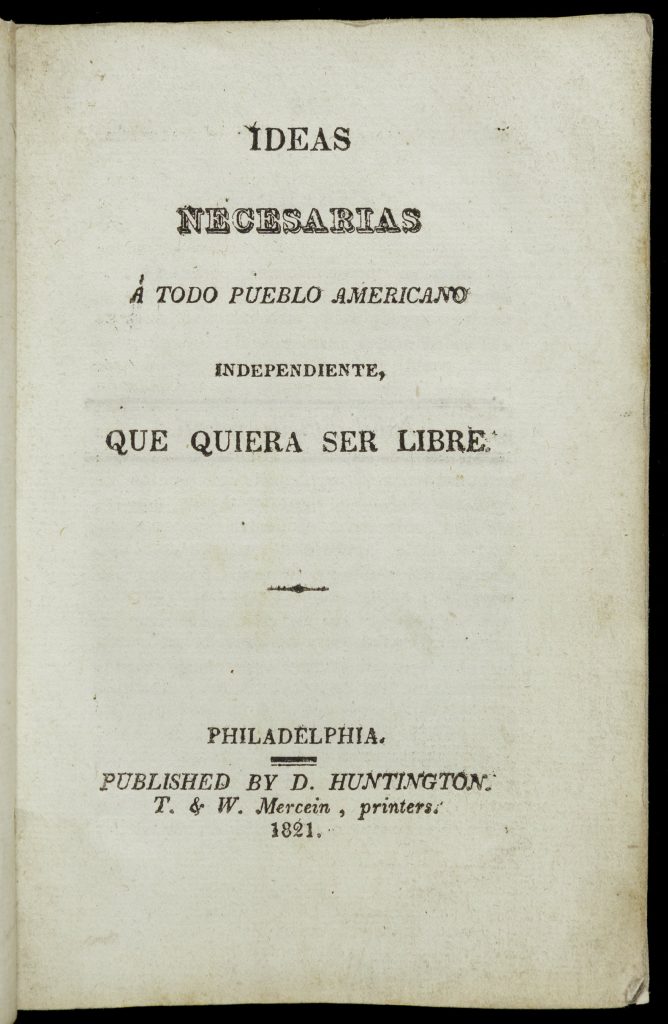

Other Revolutions

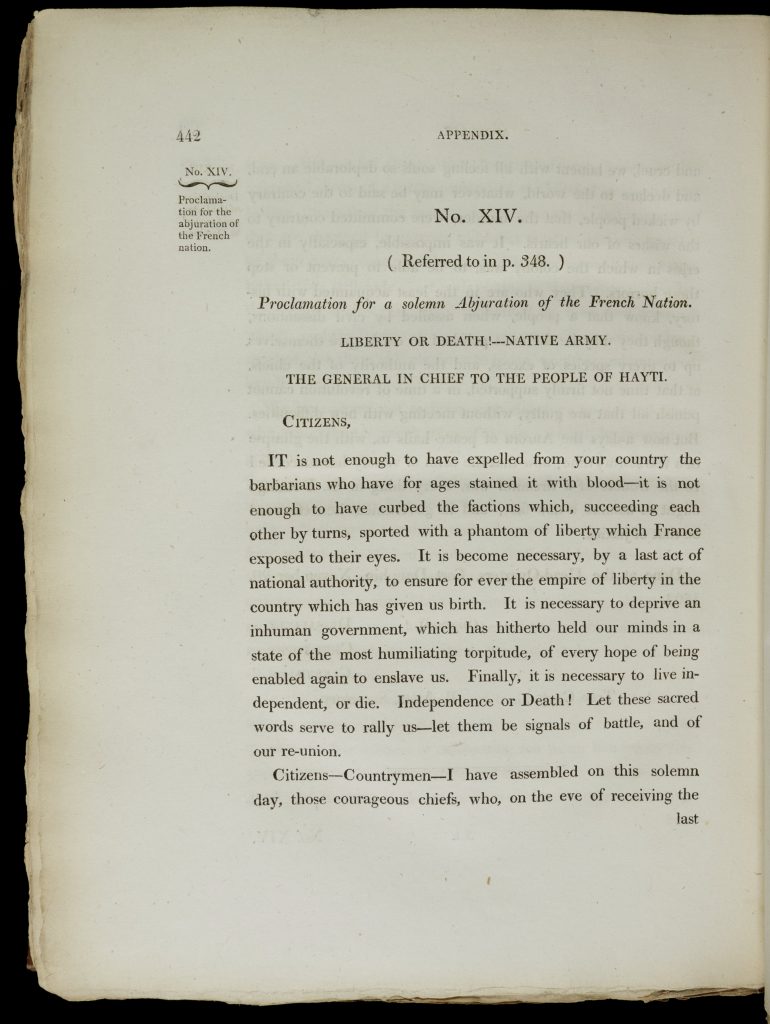

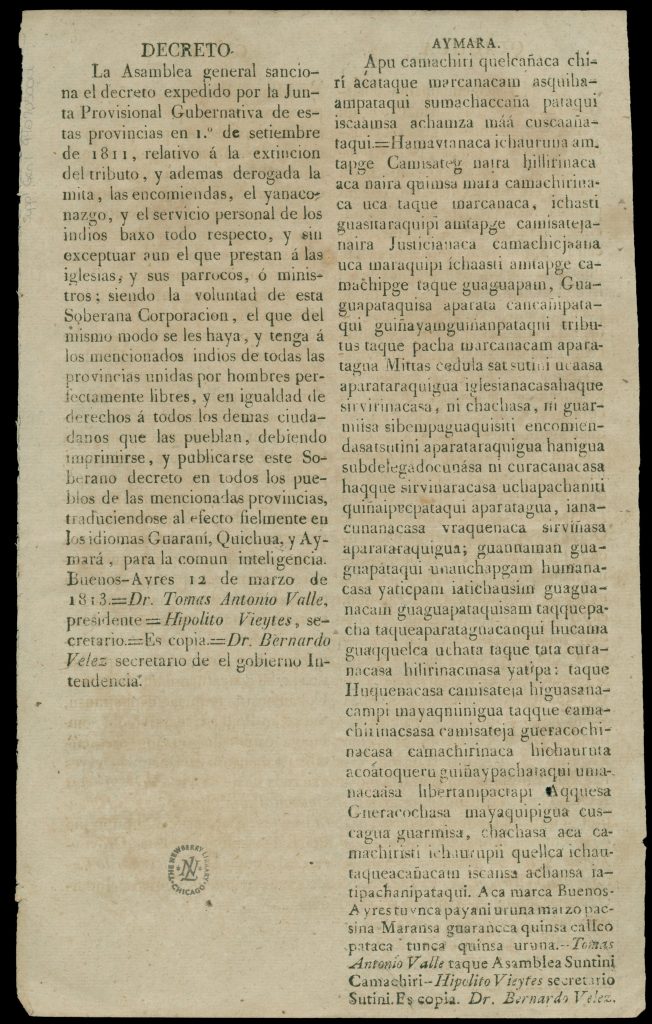

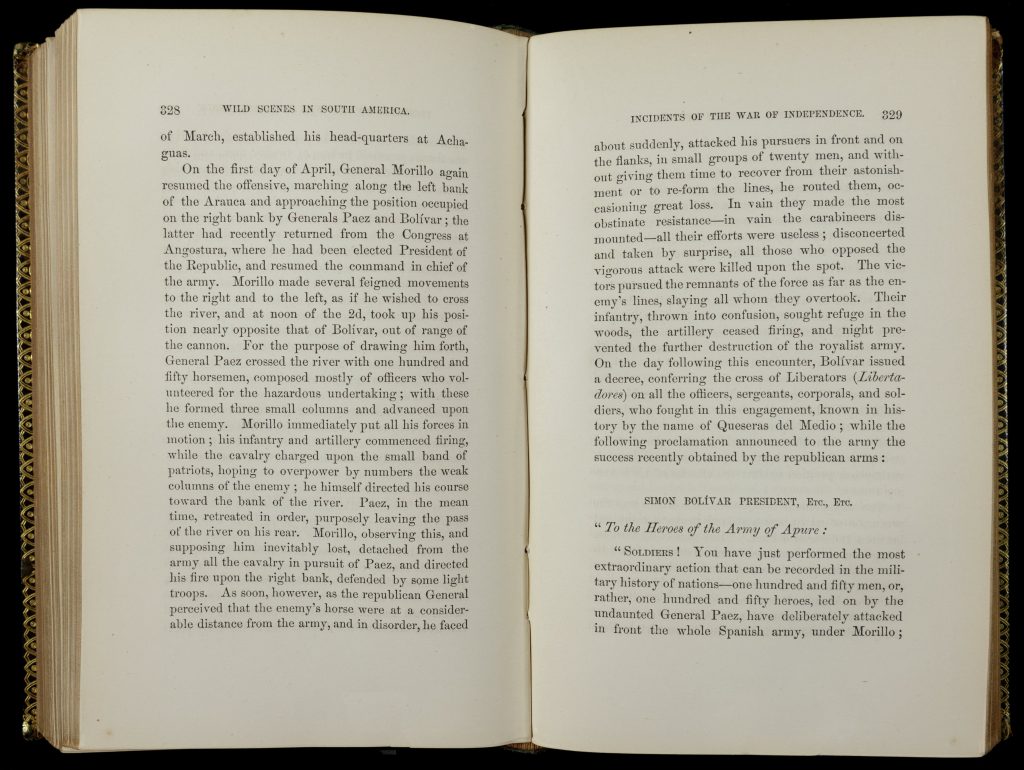

By 1810, Spanish America could look to other nations to see revolutions and their results. Some were a positive influence: The American Revolution (1765–1783) was seen by many in South America as a good example of elite leaders of colonies throwing off European rule and replacing it with a more fair and democratic society—later, some constitutions of new republics borrowed heavily from the U.S. Constitution. Other revolutions were not as positive. The Haitian Revolution, a bloody but successful uprising of enslaved people against their French colonial enslavers (1791–1804), terrified landowners in the Caribbean and northern South America, and as the situation worsened in Spain, many feared that Spain could not protect them from a similar uprising.

A Weakened Spain

In 1788, Charles III of Spain, a competent ruler, died, and his son Charles IV took over. Charles IV was weak and indecisive and mostly occupied himself with hunting, allowing his ministers to run the Empire. As an ally of Napoleon's First French Empire, Spain willingly joined with Napoleonic France and began fighting the British. With a weak ruler and the Spanish military tied up, Spain's presence in the New World decreased markedly and the Creoles felt more ignored than ever.

After Spanish and French naval forces were crushed at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, Spain's ability to control the colonies lessened even more. When Great Britain attacked Buenos Aires in 1806–1807, Spain could not defend the city and a local militia had to suffice.

American Identities

There was a growing sense in the colonies of being separate from Spain. These differences were cultural and often a source of great pride among Creole families and regions. By the end of the eighteenth century, the visiting Prussian scientist Alexander Von Humboldt (1769–1859) noted that the locals preferred to be called Americans rather than Spaniards. Meanwhile, Spanish officials and newcomers consistently treated Creoles with disdain, maintaining and further widening the social gap between them.

While Spain was racially "pure" in the sense that the Moors, Jews, Romani people, and other ethnic groups had been kicked out centuries before, the New World populations were a diverse mixture of Europeans, Indigenous people (some of whom were enslaved), and enslaved Black people. The highly racist colonial society was extremely sensitive to minute percentages of Black or Indigenous blood. A person's status in society could be determined by how many 64ths of Spanish heritage one had.

To further muddle things up, Spanish law allowed wealthy people of mixed heritage to "buy" whiteness and thus rise in a society that did not want to see their status change. This caused resentment within the privileged classes. The "dark side" of the revolutions was that they were fought, in part, to maintain a racist status quo in the colonies freed of Spanish liberalism.

Final Straw: Napoleon Invades Spain 1808

Tired of the waffling of Charles IV and Spain's inconsistency as an ally, Napoleon invaded in 1808 and quickly conquered not only Spain but Portugal as well. He replaced Charles IV with his own brother, Joseph Bonaparte . A Spain ruled by France was an outrage even for New World loyalists. Many men and women who would have otherwise supported the royalist side now joined the insurgents. Those who resisted Napoleon in Spain begged the colonials for help but refused to promise to reduce trade restrictions if they won.

The chaos in Spain provided a perfect excuse to rebel without committing treason. Many Creoles said they were loyal to Spain, not Napoleon. In places like Argentina, colonies "sort of" declared independence, claiming they would only rule themselves until such time as Charles IV or his son Ferdinand was put back on the Spanish throne. This half-measure was much more palatable to those who did not want to declare independence outright. But in the end, there was no real going back from such a step. Argentina was the first to formally declare independence on July 9, 1816.

The independence of Latin America from Spain was a foregone conclusion as soon as the creoles began thinking of themselves as Americans and the Spaniards as something different from them. By that time, Spain was between a rock and a hard place: The creoles clamored for positions of influence in the colonial bureaucracy and for freer trade. Spain granted neither, which caused great resentment and helped lead to independence. Even if Spain had agreed to these changes, they would have created a more powerful, wealthy colonial elite with experience in administering their home regions—a road that also would have led directly to independence. Some Spanish officials must have realized this and so the decision was taken to squeeze the utmost out of the colonial system before it collapsed.

Of all of the factors listed above, the most important is probably Napoleon 's invasion of Spain. Not only did it provide a massive distraction and tie up Spanish troops and ships, it pushed many undecided Creoles over the edge in favor of independence. By the time Spain was beginning to stabilize—Ferdinand reclaimed the throne in 1813—colonies in Mexico, Argentina, and northern South America were in revolt.

- Lockhart, James, and Stuart B. Schwartz. "Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil." Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Lynch, John. Simón Bolívar: A Life. 2006: Yale University Press.

- Scheina, Robert L. " Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899." Washington: Brassey's, 2003.

- Selbin, Eric. "Modern Latin American Revolutions," 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2018.

- Venezuela’s Declaration of Independence in 1810

- Chile's Independence Day: September 18, 1810

- How Latin America Gained Independence from Spain

- Biography of Francisco de Miranda, Venezuelan Leader

- The History of Venezuela

- The 10 Most Important Events in the History of Latin America

- Mexico's Independence Day: September 16

- The "Cry of Dolores" and Mexican Independence

- Biography of José Francisco de San Martín, Latin American Liberator

- Civil Wars and Revolutions in Latin American History

- Spain's American Colonies and the Encomienda System

- Foreign Intervention in Latin America

- Top Ten Villains of Latin American History

- 10 Myths About Spanish and the People Who Speak It

- American Revolution: Treaty of Alliance (1778)

- Effects of the American Revolutionary War on Britain

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

AP®︎/College US History

Course: ap®︎/college us history > unit 3.

- Women in the American Revolution

- Social consequences of revolutionary ideals

Latin American independence movements

Want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Video transcript

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 Independence in Latin America

Jeremy Adelman is the Walter Samuel Carpenter III Professor in Spanish Civilization and Culture at Princeton University, where he is also the Director of the Council for International Teaching and Research. The author of several books and articles on nineteenth- and twentieth-century Latin American history, his most recent study is Sovereignty and Revolution in the Iberian Atlantic (Princeton University Press, 2006). Also, he has coauthored a textbook in world history, Worlds Together, Worlds Apart: A History of the World from the Origins of Humankind to the Present (W.W. Norton, 2008).

- Published: 18 September 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article bridges the colonial and the national period in a discussion of the independence movements. This topic, part of foundational narratives in the region, once represented the core of Latin American history. The shift to structural and socioeconomic analysis after the 1960s led to a period neglect of a topic that came to be considered too Whiggish and celebratory or, at best, not particularly consequential. But a renewed interest in political history and, more recently, the expectation of several bicentenaries in 2010, have brought a new crop of studies of the emancipation process. By following historians' changing attitudes on the theme, the article also tells us much about the intellectual climate in Latin America during the last half century.

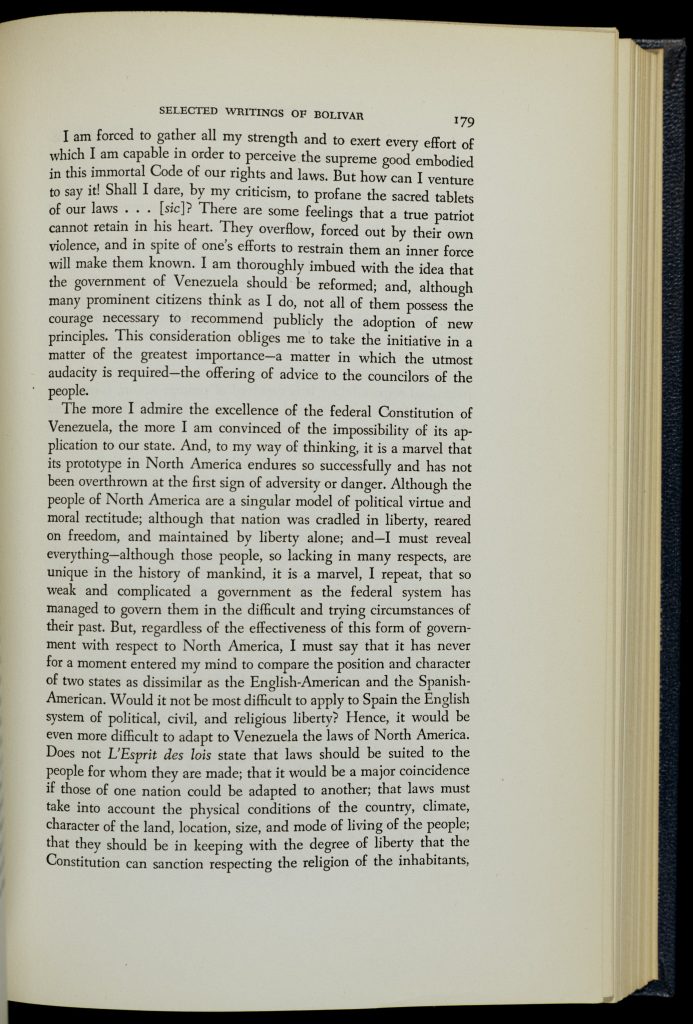

L atin America's secession from Spain and Portugal occupies an important yet enigmatic place in the region's historiography. Like many epochal struggles, it has been the source of endless romanticizing and heroic storytelling. But it has also been singled out as a period in which things that might have happened, often presuming that these would have been for the good, did not. The result is a distinctive blend of worshiping and bashing of the principal figures of the age, and conclusions that the struggles for sovereignty were redeeming, lamentable, or simply inconsequential. Simon Bolívar, who more than any other founder shouldered this polarized view of the independence period, pronounced to the Colombian assemblymen in 1830: “Fellow citizens! I blush to say this: Independence is the only benefit we have acquired, to the detriment of all the rest.” As if to ensure that his handiwork could cut both ways, he also added: “But independence opens the door to us to win back the others under your sovereign authority, in all the splendor of glory and freedom.” 1 It is easy to let the stirring invocations of glory dominate the final sentence of what was one of Bolívar's adieus to Colombians. But from the historian's vantage point, the notion of recovering what was lost evokes what has been so thorny about this period. After all, wasn't independence about realizing something new, not retrieving what was gone?

The writing of modern history has been tied up with the fortunes and visions of the nation-state. For colonial societies especially, decolonization or independence is the epochal moment in which nations come into being; at the hands of historians, it is the quintessential subject for epic nationalist tales. What has been distinctive about Latin America, however, is that the rather unsettled (some might say dismal) view of the “national question” has translated into an unresolved debate over how to write the history of the moment that gave birth to Latin American nations. While other countries and regions created triumphal narratives of the struggle for sovereignty, such a formulation was never easily accepted or universalized in Latin America. National creation myths, even the best ones, condense potential narratives into one or a few privileged stories with an eye to assimilating a national people with and into their history. The task of integrating histories, like integrating peoples, has not fared as well as Latin American nationalists of all shapes and sizes would have liked. Instead of a historical consensus, there has been a contest—at times more explicit than others—over the significance of independence to Latin America. Indeed, Latin America's historiography of the making of its sovereignty is the history of a debate over the region's somewhat complicated experience of modern life.

What this means is that the founding epics of national history in Latin America were less constrained but more confused than narratives of national purpose and realization in other corners of the Atlantic world. Thomas Bender has recently noted of the United States that the bounded unity of the nation inspired, while limiting, history writing in the “other” America. Quite the opposite has been true, as this essay will illustrate, of Latin American historiography. The disunity of nationhood was more often the departure point for narratives of Latin American independence. Even recent historians' efforts to transcend nation-centric stories are less discontinuous with a heritage of almost two centuries of Latin American history writing premised on—and often vexed by—the unbounded sovereignty of the Latin American nation-states. 2

Nation Building and National Histories

By definition, there was no history of independence until it happened. Accordingly, the writing of Latin America's secession from Spain and Portugal emerged just as a particular brand of history was coming into vogue in the 1820s and 1830s: grand narratives written in the idiom of the nation. Thomas Macaulay, Jules Michelet, and George Bancroft were more than great epic writers—with the revolutions in England, France, and the United States being the charmed sujets du jour —they were great national synthesizers; revolutions were epochal moments of nations coming into being. Nations had a collective past, shared a cathartic and bonding experience in toppling an old order, and were thus poised for a common future.

Much the same spirit inspired the first generation of Latin American historians, but they had quite different views of their subject. On the heels of the declarations of independence, letrados rushed to pen their epics of “Colombian,” “Mexican,” or “Brazilian” histories. The stories they told were never divorced from the ideological or partisan struggles that endured after independence. Indeed many of these letrados were combatants in these brawls, and their histories were scarcely disguised tomes to lend legitimacy to one side or the other. But they did conform to some common models of what “history” was supposed to look like. First and foremost, the language of the nation was hard to disentangle from the language of history—few details were spared for stories that did not fit the nation-building enterprise. Secondly, the history of independence was associated with models of constitutionalism, so that narratives of independence dwelled on the fortunes of centralism, federalism, and democracy as the legal principles needed in order to attach civil society to its nation-state.

Epic-writing about Latin American nationhood lent itself to a plurality of narratives because so many of the first great accounts began from the premise that the nations were themselves still works in progress. This was as true for liberal pessimists like José Manuel Restrepo and liberal optimists like Bartolomé Mitre as it was for conservative authors like Lucás Alamán. While fixating on the great men of the era of Colombian, Argentine, or Mexican independence, they also had to contend with the flawed characters of the liberators and the liberated in order to point to the unfinished business of the struggles they unleashed. 3 The nineteenth century was the classic age for writing about independence as a national saga through the martyred efforts of great men: Bolívar, San Martín, Hidalgo, and even Iturbide. This vision has echoed to the present in the cultish views of many of these leaders, as Germán Carrera Damas has shown provocatively in the case of Bolívar. 4 It may well be that images of sacrifice, and the notion that the revolutions remained unfulfilled, gave these leaders a significance that could be easily adapted to contemporary valences (so Peronists could trace a genealogy from San Martín to Perón; and of course Hugo Chávez is distinctly unabashed in his self-portraits as a reincarnation of Bolívar). Brazilian independence was more difficult to fit into this personalized mold of national history, but there were nonetheless efforts to portray Pedro I, for instance, as a national hero, guided by the pragmatic visionary, José Bonifacio, in making the decisive break with Lisbon. And if the continued popularity of Oliveira Lima's 1922 study, published on the centenary of Brazilian independence, is any gauge, the preeminent role of sagacious men who personified a national spirit resonated in Brazil too. 5

While flawed leaders dominated the foreground, there had to be something to personify. The nation that was born with independence took the stage along with its heroic “fathers.” While there was not much examination of the history of this “nation,” it was assumed that a popular consensus and spirit were coherent enough to reject colonialism and follow a prophet to a new land. For the uplifting national historians, this was the formulation. But it was never wholly accepted; it never yielded to a bounded unity to the region's historiography, one which mapped itself onto the visions of the nation it was supposed to serve. Thus, while there was a celebratory streak in the classical historiography, there was also much more discord and disunity regarding the properties of the nation that came into being with independence. Not even the pomp and ceremony of the centenaries of independence could drown out the uneasy feelings that writing the history of independence was not the same thing as celebrating it. It did not help that 1910 was a climactic year in Latin America as social revolution, anarchism, and millenarianism swept the region.

Personalizing history did not mean simplifying it; whereas American history continues to be bogged down in the celebration of the “character” of the founding fathers, historians of Latin America have not been given to the euphoric (or distempered) style. If Karen Racine's wonderful biography of Francisco de Miranda, David Bushnell's of Bolívar, Iván Jaksic's on Andrés Bello, Timothy Anna's of Iturbide, and Neill Macaulay's on Dom Pedro I are any gauge, this genre enabled historians to take a close look at the internal contradictions and agonies of movements that did anything but move in a straight, cohesive line. Perhaps this also explains why the saga of Latin American revolutions has also provided material for novelistic renditions by Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, and others. For Jorge Luis Borges, the political upheaval was the setting for a drama of the mind. In Borges's “A Page to Commemorate Colonel Suárez, Victor at Junín,” his subject reflects thus:

What does my battle at Junín matter if it is only a glorious memory, or a date learned by rote for an examination, or a place in the atlas? The battle is everlasting and can do without the pomp of actual armies and of trumpets. Junín is two civilians cursing a tyrant on a street corner, or an unknown man somewhere, dying in prison. 9

The Structuralist Moment

If the epics of the classic age stressed the agency of great—and not so great—men as flawed prophets of imperfect nations, it was not very clear why Portuguese and Spanish colonies should give way to nations without recourse to explanations that relied on a natural, almost preordained logic. It was, ironically, the turn in Latin American nationalism during the 1930s that compelled historians to query some of the precepts of the classic age without dislodging the centrality of the national question. What emerged was a much more structuralist style of history that distanced itself from many of the earlier narratives that had emphasized the voluntarism of its great actors. The revisionist work took place against the backdrop of a world economic crisis, rising anticolonial sentiment around the world, and increasing awareness across the political spectrum that the liberal ideas, intellectual styles, and accompanying political and social regimes of the previous century were more than simply exhausted. Liberalism was, in a sense, the ideology that perpetuated fragmentation of national communities rather than transcending it.

The 1930s was the heyday of revisionism and a self-conscious effort to reject much of the official, “centenary”-style history. In Argentina, revisionistas went to work to debunk the illusory world that Mitre, as President and as historian, had concocted. Not only did the revolutions fail, their progeny, and especially the landowning classes and merchants of Buenos Aires, delivered the vital interests of the patria to foreign, imperialist interlopers waving the Union Jack. “Independence” was thus a formal sham covering up an underlying informal process of reconquest by industrial powers. Peruvian historians echoed José Carlos Mariátegui and Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre and denounced the oligarchic republics for having betrayed the national and popular interests. In Mexico, after the Revolution of 1910, nationalists decried liberals and conservatives alike; as elsewhere, they began to examine the “nation” in a distinctly indigenous and autochthonous idiom.

By the 1940s and 1950s, independence began to look less like a national climacteric than one, albeit dramatic, point in a series of clashing tendencies nested within colonial and postcolonial societies. Indeed, many were beginning to wonder whether “independence” had a seismic logic at all. For Marxists like Mariátegui and many of his readers, capitalism was still locking horns with persistent feudalism; for writers influenced by Max Weber and what later became called “modernization theory,” the basic contradiction was between traditional, ascriptive, personalizing forces and the forces of modernity—rational, impersonal, and prescriptive. Both views found themselves combined into, or adapted to, the third-worldist vocabulary of “underdevelopment.”

Elite Crisis of the Ancien Régime

With the maturing of a more structuralist view of history and the shift away from nation-centric approaches to independence, a generation of historians began to look closely at the crisis of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as the breakdown of long-lasting colonial pacts—an elite crisis that induced some creoles to devise national frameworks to supplant old imperial ones once the ancien régime was on its last legs. The corrosion of elite fealty and integration set the stage for the implosion of the state. Yet even here there was a basic enigma. Doris Ladd's important study of the Mexican high elite illustrated the degree of elite integration through extended Active and real kin networks, as well as the sharp creolization of the aristocracy (in contrast to the view that creoles were marginalized by the Bourbon reforms) in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Other works on late colonial elites in Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires, for example, concurred. Indeed, as the political scientist Jorge Domínguez noted in his study of the crisis of a “patrimonial” Spanish empire, elite competition was accommodated within ancien régime rules—except where emergent elites displayed “incipiently modernizing” orientations. But this was, he concluded, rare. 14 So, given the integration of elites and unprecedented incorporation of American fractions, how did the elite crisis transpire?

For some, ideology and the effects of the Enlightenment fractured an elite whose cohesion could not rest only on common interests or fears. Simon Collier, for instance, wrote a peerless study of the breakdown of consensus among Chilean elites (who ranked among the most tightly knit and stable of the colonial outposts) and the struggle to forge a new alliance, emboldened perhaps more by political conviction than by economic interests—a book which would inaugurate an important series of monographs published by Cambridge University Press (and which Collier himself edited). At the same time, Carlos Guilherme Mota looked at the mentalités of Brazilian plutocrats to show the uneven and partial local consumption and adaptation of European ideas, which confirmed Brazilians' sense of prospective modernization while fueling an anxiety that they were falling short of some universal (read: Europeanized) norm. The result was a simultaneous fascination with and revulsion against the idea of revolution. On the whole, however, the intellectual history of the period was surprisingly scant, in contrast to the current of idealism that so decisively shaped North American historiography. 15 There is one important exception: Renán Silva's recent study of education, libraries, books, and reading in the half century before 1808 follows the recent turn in the history of learned cultures to take a fresh look at figures of the New Granadan Enlightement without assuming that an interpretive community synthesized into a nationalist elite bursting to topple the ancien régime. 16

Closer examinations of colonial elites did suggest that the story of independence required a prior account of the breakdown of colonialism and elite fealty to the Iberian systems. Conflict over ideas paled beside a more “realist” conflict over power, accentuated once its central bastion, the monarchy, collapsed. Timothy Anna, Brian Hamnett, and John Fisher contributed important accounts of the administrative, social, and economic decomposition of elite unity in Mexico and Lima—but while they looked closely at the capitals of the two major viceroyalties, the struggles they charted operated within the imperial frameworks that held local elites together. Writing in the wake of the sesquicentennials of Mexican and Peruvian independence, and in response to what was then becoming a more open debate about whether revolutions were national or not, the issue was not the rise of a new elite to challenge the old order but rather the collapse of the old order, which drove wedges into colonial alliances and thus yielded new elites. For Hamnett and Anna, independence could not be separated from the larger effects of the French Revolution and the hammer blows to the Spanish monarchy. These were crises caused by Napoleon's invasion, which occasioned elite defection and then provoked a failure of governmental structures. Both historians also opened up peninsular archives for systematic reference (something earlier nationalists had not done, because they were looking for the autochthonous aspects of independence). Fisher examined the ways in which regional forces, while still loyal to the crown, fought for autonomy within Peru. Later, Anna, joined by Michael Costeloe, argued that “independence” put the historical cart before the horse—for far from bringing new nations into being, Spain's crisis or mismanagement (depending on how you look at it) “lost” American possessions; nations were the aftereffects of an imperial crisis. This was a perspective shared by Kenneth Maxwell in what has become a classic study of Brazil, with the rather obvious point that the “loss” of Brazil was much more anticipated, as Maxwell noted in the failure of the Braganza monarchy to hang on to the metropolis. More recently, Roderick Barman synthesized a much broader period, going back to the 1790s and reaching forward to the 1850s, to chart the more extended breakdown of elite pacts, whose ultimate effects were to yield something new, the nation. What all these historians argued was that the birth of the “nation” per se did not anticipate or cause a change in ruling systems, but the other way around. 17

It is tempting to see this counter-national history of independence as a vision that could be most easily grasped by non-Latin Americans, especially in the high tide of revolutionary nationalism among intellectual circles in the 1960s and 1970s. But this would be too simple. For the Brazilian economic historian Fernando Novais, independence was not a story about decolonization; it was the effect of a crisis of the ancien régime and its elites, social regimes that could no longer sustain mercantilist colonialism and absolutism and whose colonial elites had already began making the transition to something more than just primitive accumulation, so that independence was a de jure conclusion to de facto developments. Indeed, the edited volume in which Novais's influential essay appeared, edited by Carlos Guilherme Mota, was an important touchstone among Brazilian historians who wanted to advance accounts of independence that marginalized or at least contextualized the national question. 18 Peruvians began to argue that independence was less a conquest than a concession, something motivated from without by industrial powers dueling with a moribund Spain or by San Martín's and Bolívar's “foreign” armies. Peruvian elites, driven more by fear, simply switched allegiance. Heraclio Bonilla and Karen Spalding, in part reacting to the hoopla of the sesquicentennial, published a polemical and influential 1972 essay, “La Independencia en el Perú: Las palabras y los hechos,” which argued that the large structures of the world economy, and not national aspirations, caused independence. Notable was the rising sense among historians that the classical framework confused a postdictive rhetoric of nation builders with the causes and course of the breakdown of Iberian empires. 19

Perhaps the most influential study of the elite crisis that led to independence came from the pen of the Argentine historian Tulio Halperín Donghi. In a series of important articles, and subsequently in his majestic monograph Revolutión y guerra: Formatión de una élite dirigente en la Argentina criolla , he detailed the complex unwinding of systems of rulership, the opening of the centrifugal forces contained by elite unity, and the cascade into revolutionary militarization and civil war. In the dense political narrative, it is sometimes easy to forget that Halperín Donghi was attentive to the underlying social and economic shifts in trade and production that made it harder and harder to keep old mercantilists and new commercial interests within the same bloc. Halperín Donghi later expanded to a general level the notion of elite crisis in response to the schisms unleashed by empires struggling to cope with war and commercial competition; in Reforma y disolución de los imperios ibéricos, 1750–1850 he argued, along with Anna and others, that independence was intricately linked with, if not caused by, imperial dissolution. 20 Fernando Novais and other Brazilian historians were even more insistent that independence was driven by underlying structural forces and had little to do with national aspirations, and using an approach like Halperín Donghi's they argued that Brazil's secession was a response to a broader crisis of the Portuguese empire, a crisis that had sundered the consensus among ruling elites and propelled them to secede, albeit with far less friction and discord than in Spanish America.

Structural models of history transcended personalized narratives and national teleologies; they did not dismiss them, but contextualized people and movements within more sociological frames. The focus tended to be on political and economic elites, and how their collaboration extracted revenues and rents from colonial societies. It was when the institutional conditions that supported these alliances broke down, either under the weight of the fiscal and commercial pressures of Atlantic warfare or faced with changing ideological precepts of rulership and rights, that revolutions erupted. And when colonial agents could no longer see their interests upheld within a framework of empire, they broke loose. Thus it was that the idyll of a coherent “nation” pursuing liberation stepped aside in favor of a more instrumental approach to history, one which conformed to a more general turn in history and the social sciences towards “realist” approaches that accentuated the struggle for political power in the absence of a dominant legitimating system, or Marxian approaches that dwelled on the conflict of material interests between old mercantilist peninsular concerns and a rising, possibly even “bourgeois,” class in the colonies. As one suggestive synthesis recently argued, independence was simply one dimension of a more general crisis of the Spanish state which broke the institutional fetters on capitalist development. As such, Peter Guardino and Charles Walker argued, the period qualifies as a bourgeois revolution (albeit without a thoroughbred bourgeoisie to lead it). 21

The Failed Revolution?

The view of a revolution that failed, or that never was, found the most currency in a series of important monographs about popular insurrections for a different, more inclusive new order that were crushed by peninsular reactionaries and scared creole elites whose visions of a new order stopped short of spreading the social dividends of change more broadly. For Marxists looking for a bourgeoisie to topple a feudal system, as well as for liberals looking for enlightened penseurs determined to bring reason to a backward regime of estates, there may have been a break with independence, but not a social revolution. For Bonilla and Spalding, the rupture of independence was decisive because it enabled a fundamentally colonial society to subsist precisely because it declared independence. What limeño elites did was to cash in the formal rule of Spain for the informal domain of Great Britain. For Indians, rural folk, and the great majority, “independence” was a word, little more—Túpac Amaru's rebellion, far from being one of the protonational precursors, represented a terminal defeat (that is, until the specter of a socialist revolution came along) for aspirants of a new order, whose spectral presence frightened elites into clinging onto old systems. 23

It may be argued that Peruvians were especially inclined to view independence as less than a triumphal moment because of the lateness of secession and the prevalence of outside armies. But they were not. The shift can best be seen in the emergence of important studies of rural folk who seized upon the political rupture to effect a different social order. In 1966, Hugh Hamill published a pioneering study of Father Hidalgo, recasting him less as a national (or protonational) hero or misguided lunatic than as a prophetic leader of a people who were fed up with the violations of their moral economy—and who carried an anti-Spanish flag not because they were “Mexicans” but because they objected to their colonial status and its burdens. Hidalgo therefore helped inaugurate the regime's legitimacy crisis and thus usher in independence, even though the social order that eventuated bore little resemblance to the one he and his followers would have wanted. 24 Another example of a failed, or foiled, movement that articulated something different was Carlos Guilherme Mota's study of the 1817 uprising in Pernambuco. While Mota put greater stress on the interethnic and cross-class alliances that challenged the old order than did Hamill, what was important was the opposition to rulers in Rio de Janeiro and not Lisbon. Mota argued that the movement was less successful at realizing its own affirmative goals than at crippling an already wobbly Braganza dynasty. Yet what the federalist spirit of 1817 expressed was a localized, and not national, concept of sovereignty. Indeed, one of the running concerns for the rebels was a struggle against “monopoly” of all sorts. 25 Like Hamill's study, Mota's explored a failed revolution, but one that ensured that there was no return to the status quo ante.

It should be stressed that failure did not mean permanent defeat. What these case studies showed was that there was a latent meaning to independence that had been crushed, but whose legacies survived. For Mota, the Pernambucan rebels, especially the more populist elements, lived on to rally behind the 1824 creation of the Confederation of the Equator; for Hamill, there endured an Indian and mestizo resistance to any restoration, which informed liberals across the nineteenth-century Mexican political landscape; and for Sala de Touron and her coauthors, Artigas lived on in the spirit of federalist insurgents, which could be read, not unreasonably, as a genealogical founding of the Tupamaro guerrillas fighting for a cause that had not been won in 1810.

After the Revolution

By the early 1980s there existed a plenitude of narratives about the significance and meaning of independence in Latin American history. In a sense, this was already implicit in the classical formulation, which had never managed to stabilize a bounded unity to national histories. What changed was how historians were choosing to see the disunity within the national framework, or giving bounded structures to struggles that decentered national aspirations. But as the 1980s unfolded, in a context in which the region emerged from years of dictatorship and civil war, historians returned to the political content of independence. They were now less dismissive of some of the formal changes that accompanied it. After all the traumas of the repression, the formalities of citizenship acquired new, and vital, significance. What is more, as intellectual life became less radical, the urge to find hidden transformative possibilities within the upheavals of the early nineteenth century lost its charm. Indeed, a historiographical preference once so resolutely dismissed, military history, showed signs of some recovery. Clément Thibaud, for instance, shows—at some length—how the military played a central role in nation making, not as a result of its triumphant feats but out of the sociability within colonial militias that evolved into standing armies. 28

And yet, despite the historiographical turns of the 1980s, the “national question” remained as fractured and unresolved as ever. This change within continuity is expressed in two major directions in which historians pursued their research on independence. The first was a return to the study of the formal political arena cast across a broad “Atlantic” framework. The second involved a closer examination of some of the social and cultural developments that were associated with independence but had very little to do with any process of nation building.

It could be argued that the restorations (or, in some cases, the first instantiations) of democracy in the 1980s motivated historians to look at formal politics in the early nineteenth century. But this, as with so many other historiographical shifts, had its pioneering anticipators. To begin with, the classical histories, anthologies of documents, and constitutional collections had explored state formation, albeit from a somewhat rigid perspective. But there were many historians who defied the simplifying nationalist mold. Among them was the Texas-based scholar Nettie Lee Benson, who authored several important articles and compiled a formative group of essays written by a group of graduate students that centered on the effects that the convocation of deputies to the Spanish Cortes, with the Junta reeling from the pressures of Napoleon's armies. Mexico and the Spanish Cortes, 1810–1822 was published in 1966, and in a sense looked back to an earlier constitutional history. However, it also anticipated by several decades a fascination with the sudden intervention of electoral and representative activity in Spain and the empire. To be sure, as Benson argued, the Cortes for the first time claimed to represent the parts of the empire (provinces, colonies, estates) as a single “Spanish” nation, thereby forcing the national question into the political arena, but it also charted a new course for resolving the regime's legitimacy, elections. For all the studies of political leadership, Benson struck a nerve when she wrote that “few developments in the history of the Spanish colonial system have been more carelessly treated or more misinterpreted than the attempt to establish constitutional government under the Spanish monarchy …” What emerged from the essays, and in her later monograph The Provincial Deputation in Mexico (originally published in Mexico in 1955), was how the rupture in the fundaments of political rule sent riptides across the Spanish dominions that altered the practice of politics and gave rise to understandings of political identity that could not be reduced to social class, economic interest, or location in the world economy. 29 And if the efforts to create new foundations for political legitimacy within the Spanish empire had been overlooked, the situation was even more obscure in the Portuguese empire.

There was a reason why constitutionalism under the Spanish monarchy had been so ill treated: in the rush to establish a narrative of a colony becoming a nation and repudiating its overlords, there was little room for examining how the empires broke up, since the result was so foreordained. The structural emphasis on inevitable decay was no more illuminating than the classical approach it sought to replace. With relatively few exceptions, most historians were willing to accept at face value the language of rebels who believed that nothing Spanish or Portuguese could ever accommodate itself to a more reasoned and representative system. It did not help that this often dovetailed with an Anglo-American propensity to think of constitutionalism as a uniquely Anglo-Saxon art. What Benson called for, and what historians began to pick up in the 1980s, was thus the long history of imperial crisis which presaged independence. Accordingly, there proliferated a great many case studies of elections.

One important collection of essays, edited by Antonio Annino, explored the effects of electoral life in a wide array of settings, from Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro to the Yucatan peninsula. One of the goals of this work is to dispense with the bacilli of the Black Legend which presumed that the experience of modern political representation in Latin America had (and has) been a failure, a view reinforced by the overwhelming echo of nineteenth-century elite voices that decried the disorder and anarchy of voting. Greater attention to suffrage dislodged the more familiar story about caudillos and caciques as the political inheritors of the Liberators' efforts. This direction of research, it is worth saying, paid less attention to “parties” and electoral outcomes (whose polls were, in any event, very uneven predictors of who actually won these contests) and more on electoral practices as “inputs” contributing to political cultures in formation, and this being a conditioning force for state formation. The result is that political citizenship conditioned states as much as the other way around. What this meant for how historians understand independence is clear enough: it was one of a series of larger unresolved questions about sovereignty, and making sense of independence requires a prior analysis of some of the ways in which political life changed in the wake of an imperial crisis in the metropolis. In the case of Mexico, for instance, Virginia Guedea has charted the manifold ways in which insurgents and loyalists alike turned to elections to rally support and popular practices of suffrage coexisted with military activity to sort out allegiances and alignments across New Spain between 1810 and 1821. And as Karen Caplan has observed, it was not just Spaniards and creoles who turned to elections; Indians in Oaxaca and Yucatán also embraced voting as a means to resolve disputes over municipal leadership. If Mexicans developed a national consciousness, they did so during, or perhaps because of, a fundamental rupture in the practice of politics. 30

There have also been a series of very important studies of the deliberative work of the Cortes itself, showing how the parliament wrestled with reintegrating the components of an empire or monarchy into a single, multicontinental, and multiethnic “nation.” Márcia Regina Berbel, for instance, has published an account of how the elected deputies to the Cortes in Lisbon went to the metropolis to defend the unity of the Portuguese nation and the consequential equality of subjects within it. Almost two years of deliberation yielded to divergent notions of what it meant to belong to a single nation. As Berbel's book shows, the justifications for “Brazilian” secession did not mean that “Brazilians” subscribed to a common framework of national membership; some of the very same fissures that opened in Lisbon remained open when sovereignty was repatriated to Rio de Janeiro. 31 Other historians have taken seriously the political theory, or theories, that informed what became an increasingly polarized set of positions over the statehood that was supposed to sustain nationhood within empire or monarchy. To José Carlos Chiaramonte, for instance, rebellious and reactionary proponents of sovereignty operated within a doctrinal framework of natural rights and a cult of civic virtue, not national rights, equally defensible at subnational (municipal or provincial) levels and at supranational ones (like a “monarchy”). In this way, ancient norms could give way to new political forms. Brazil's constitutional break was therefore with Lisbon, not with monarchy, and was not a mere outlier, simply one expression of a new combination of political sentiments, which relocated the spatial boundaries of the political community with independence without repudiating empire or monarchy as the means to bond a political regime to its social composition. Nationhood was therefore but one of the progeny of a shift in models of citizenship; Chiaramonte made explicit what was becoming an implicit recognition: it was the state that created the conditions for the nation, and not a maturing national esprit that created new states. 32

In the 1980s, therefore, historians were turning full circle to the analysis of the institutional structures of rulership, restoring the autonomy of the political field but sidelining the heroes of the nations they were supposed to personify. There was also another important departure from the classical legacies: greater attention was paid to the contingencies of political decomposition and recomposition of empire before the independence of its colonies, thus sparing the analysis of its predestined, nationalizing outcome. Independence was becoming a political effect, not a cause of political change. For María de Lourdes Viana Lyra, Brazilian secession came after several decades of imperial tinkering and efforts on the part of colonists and metropolitans alike to reimagine the empire before ditching it in favor of something else, like the nation-state—or, to be more accurate, to reinvent the empire as a nation-state. Roberto Breña's important recent study of Mexico goes a step further: it argues that the crisis within the Spanish empire evolved within the understandings of liberalism in all corners of Madrid's dominion, which had itself evolved from Bourbon Enlightenment trends; the crisis was internal to the ideological makeup of the system itself. 33

Indeed, there has been a full reevaluation of loyalism and the stresses and strains of the ancien régime before its final collapse as conditions of rebellion. John Fisher for Peru and Christon Archer for Mexico, for instance, have shown how much loyalists feuded and wrangled over what to do after 1808—a dimension of the conflict which had been completely occluded by the nationalist accounts, which preferred to leave loyalists as an undifferentiated mass of reactionaries. Scarlett OʼPhelan Godoy has compiled an important collection of essays specifically dealing with life in Peru from 1808 to the 1820s, that is, the years between the monarchy's collapse and the final defeat of peninsular armies. What becomes clear is that Peru did not conform to the image of unflinching loyalty and stasis. Indeed, as OʼPhelan Godoy remarked in a critique of Bonilla and Spalding's view that independence was simply “conceded” rather than achieved, there was a great deal more unrest and discontinuity even within the most “loyal” of Iberian viceroyalties than historians have admitted—in large part because they have been so obsessed with locating the origins of a national quest for sovereign redemption rather than conflict and violence over what it meant to persist in empire and monarchy. In a nuanced study by Víctor Peralta of José Fernández de Abascal, the formidable viceroy in Lima from 1806 to 1816, it is clear that for all the Spaniard's cunning, he was running a tough gauntlet between subjects itching to try on new liberties and loyalists who despised the change but were reluctant to fund the suppression of its more radical proponents. Gustavo Montoya, in a fine-grained essay, explored the waverings of limeño dominant classes during San Martín's occupation of the city, with royalist armies camped just outside. In these circumstances, it was not at all clear what to do—and to slap simplified causal models onto complex contingencies seems increasingly ahistorical (though perhaps no less tempting just because the scenarios of collapsing systems are so complex). 34

There is now a welter of very good studies of what it meant to be on the “other,” loyalist, side of the political line to complement the increasingly complex view of the divisions and changes within the patriot cause. In a sense, Germán Carrera Damas's study of the Venezuelan loyalist Boves, while still a blood-curdling read, no longer stands alone in urging readers to take the defenders of empire seriously as historical subjects. Valentim Alexandre charted the step-by-step ways in which the “colonial question” was magnified into the powder keg of the Portuguese regime. Maria de Lourdes Viana Lyra has shown how conservative reformers struggled from the 1790s to shore up the Portuguese empire by recasting it as a grand trans-Atlantic utopia whose inheritors were José Bonfacio and the Brazilian Empire born in 1822. Kirsten Schultz's close study of urban political culture in Rio de Janeiro between 1808 and 1821 shows just how much potentates of all inclinations labored to recombine traditional notions of monarchy and empire with newer principles of representation and newer realities of the Americanization of power. 35

The most important and provocative intervention has come from Jaime E. Rodríguez O., who in a series of essays and edited books, and finally in The Independence of Spanish America , has recast the breakup of the Spanish empire as a civil war among Spaniards, many of whom happened to live in the Americas. The 1998 edition of The Independence of Spanish America winnows out references to colony and empire to make way for an image of a “heterogeneous confederation” of more or less equal parts bound by a “Spanish Monarchy.” There was friction but no colonial identity brewing in the peripheries, waiting, as the classical historians had argued, for the apposite moment for their birth into a national form. The problem came when Spanish subjects were forced to deal with the absence of their monarch. Spanish Americans and Spaniards could not agree on what kind of structure to put in his stead. As a result, independence was not only the end of a long political process, nation-states were the “fragments and survivals of a shattered whole” (in Octavio Paz's words) of a multicontinental cosmopolitan kingdom.

What is important to underscore about Rodríguez's argument is that colonies did not secede from an empire; it was the protracted metropolitan crisis of the ancien régime that eventuated in nations. Rodriguez crystallized a growing historical view of independence as anything but inevitable, the old regime as anything but a brittle framework incapable of adapting old practices to new ways, the nation being “Hispanic” before labels like “Colombian” or “Argentine” were assigned to the post-Hispanic shards. If the national teleology is gone, Rodríguez fills the narrative vacuum with the idea of an enduring “Spanish” and “monarchical” imagined community of preference. Here, the revisionism runs into some problems. It downplays the multiple legal principles and practices involved in being a Spanish subject on the peripheries that membership in the Monarchy did not resolve, or at least explains conflict as a contingent clash and not a structural dilemma. Sidelining the words “empire” and “colony” certainly creates more room to think about the ancien régime without presuming its demise. But dispensing with structured notions of asymmetry and inequity makes it hard to explain the violence and discord that followed the crisis of 1808. While Rodríguez challenges both the view that creoles were bound to defy imperial authority and the structuralist assumption that the old regime could not adapt to modern mores, he is forced to restore the Liberators back to the center of the political stage, albeit shorn of their heroic vestments, as the saboteurs of the system. 36

Rodríguez's works comprise a landmark in the making of modern Latin American history, having crystallized a growing view that there was a political logic to imperial change that was not reducible to underlying structural drives and their inevitability. He, and others, located the emergence of nationhood as a more truly revolutionary outcome precisely because it was so unforeseen, and not the result of a preexisting propensity.

The Unbounded Unity of Independence