An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Introduction to qualitative research methods – Part I

Shagufta bhangu, fabien provost, carlo caduff.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Prof. Carlo Caduf, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2022 Nov 28; Accepted 2022 Nov 29; Issue date 2023 Jan-Mar.

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Qualitative research methods are widely used in the social sciences and the humanities, but they can also complement quantitative approaches used in clinical research. In this article, we discuss the key features and contributions of qualitative research methods.

Keywords: Qualitative research, social sciences, sociology

INTRODUCTION

Qualitative research methods refer to techniques of investigation that rely on nonstatistical and nonnumerical methods of data collection, analysis, and evidence production. Qualitative research techniques provide a lens for learning about nonquantifiable phenomena such as people's experiences, languages, histories, and cultures. In this article, we describe the strengths and role of qualitative research methods and how these can be employed in clinical research.

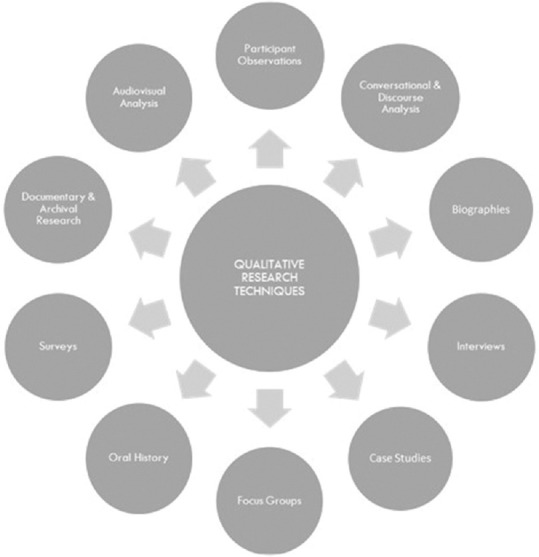

Although frequently employed in the social sciences and humanities, qualitative research methods can complement clinical research. These techniques can contribute to a better understanding of the social, cultural, political, and economic dimensions of health and illness. Social scientists and scholars in the humanities rely on a wide range of methods, including interviews, surveys, participant observation, focus groups, oral history, and archival research to examine both structural conditions and lived experience [ Figure 1 ]. Such research can not only provide robust and reliable data but can also humanize and add richness to our understanding of the ways in which people in different parts of the world perceive and experience illness and how they interact with medical institutions, systems, and therapeutics.

Examples of qualitative research techniques

Qualitative research methods should not be seen as tools that can be applied independently of theory. It is important for these tools to be based on more than just method. In their research, social scientists and scholars in the humanities emphasize social theory. Departing from a reductionist psychological model of individual behavior that often blames people for their illness, social theory focuses on relations – disease happens not simply in people but between people. This type of theoretically informed and empirically grounded research thus examines not just patients but interactions between a wide range of actors (e.g., patients, family members, friends, neighbors, local politicians, medical practitioners at all levels, and from many systems of medicine, researchers, policymakers) to give voice to the lived experiences, motivations, and constraints of all those who are touched by disease.

PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS

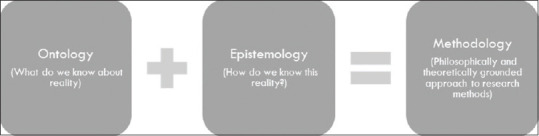

In identifying the factors that contribute to the occurrence and persistence of a phenomenon, it is paramount that we begin by asking the question: what do we know about this reality? How have we come to know this reality? These two processes, which we can refer to as the “what” question and the “how” question, are the two that all scientists (natural and social) grapple with in their research. We refer to these as the ontological and epistemological questions a research study must address. Together, they help us create a suitable methodology for any research study[ 1 ] [ Figure 2 ]. Therefore, as with quantitative methods, there must be a justifiable and logical method for understanding the world even for qualitative methods. By engaging with these two dimensions, the ontological and the epistemological, we open a path for learning that moves away from commonsensical understandings of the world, and the perpetuation of stereotypes and toward robust scientific knowledge production.

Developing a research methodology

Every discipline has a distinct research philosophy and way of viewing the world and conducting research. Philosophers and historians of science have extensively studied how these divisions and specializations have emerged over centuries.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] The most important distinction between quantitative and qualitative research techniques lies in the nature of the data they study and analyze. While the former focus on statistical, numerical, and quantitative aspects of phenomena and employ the same in data collection and analysis, qualitative techniques focus on humanistic, descriptive, and qualitative aspects of phenomena.[ 4 ]

For the findings of any research study to be reliable, they must employ the appropriate research techniques that are uniquely tailored to the phenomena under investigation. To do so, researchers must choose techniques based on their specific research questions and understand the strengths and limitations of the different tools available to them. Since clinical work lies at the intersection of both natural and social phenomena, it means that it must study both: biological and physiological phenomena (natural, quantitative, and objective phenomena) and behavioral and cultural phenomena (social, qualitative, and subjective phenomena). Therefore, clinical researchers can gain from both sets of techniques in their efforts to produce medical knowledge and bring forth scientifically informed change.

KEY FEATURES AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS

In this section, we discuss the key features and contributions of qualitative research methods [ Figure 3 ]. We describe the specific strengths and limitations of these techniques and discuss how they can be deployed in scientific investigations.

Key features of qualitative research methods

One of the most important contributions of qualitative research methods is that they provide rigorous, theoretically sound, and rational techniques for the analysis of subjective, nebulous, and difficult-to-pin-down phenomena. We are aware, for example, of the role that social factors play in health care but find it hard to qualify and quantify these in our research studies. Often, we find researchers basing their arguments on “common sense,” developing research studies based on assumptions about the people that are studied. Such commonsensical assumptions are perhaps among the greatest impediments to knowledge production. For example, in trying to understand stigma, surveys often make assumptions about its reasons and frequently associate it with vague and general common sense notions of “fear” and “lack of information.” While these may be at work, to make such assumptions based on commonsensical understandings, and without conducting research inhibit us from exploring the multiple social factors that are at work under the guise of stigma.

In unpacking commonsensical understandings and researching experiences, relationships, and other phenomena, qualitative researchers are assisted by their methodological commitment to open-ended research. By open-ended research, we mean that these techniques take on an unbiased and exploratory approach in which learnings from the field and from research participants, are recorded and analyzed to learn about the world.[ 5 ] This orientation is made possible by qualitative research techniques that are particularly effective in learning about specific social, cultural, economic, and political milieus.

Second, qualitative research methods equip us in studying complex phenomena. Qualitative research methods provide scientific tools for exploring and identifying the numerous contributing factors to an occurrence. Rather than establishing one or the other factor as more important, qualitative methods are open-ended, inductive (ground-up), and empirical. They allow us to understand the object of our analysis from multiple vantage points and in its dispersion and caution against predetermined notions of the object of inquiry. They encourage researchers instead to discover a reality that is not yet given, fixed, and predetermined by the methods that are used and the hypotheses that underlie the study.

Once the multiple factors at work in a phenomenon have been identified, we can employ quantitative techniques and embark on processes of measurement, establish patterns and regularities, and analyze the causal and correlated factors at work through statistical techniques. For example, a doctor may observe that there is a high patient drop-out in treatment. Before carrying out a study which relies on quantitative techniques, qualitative research methods such as conversation analysis, interviews, surveys, or even focus group discussions may prove more effective in learning about all the factors that are contributing to patient default. After identifying the multiple, intersecting factors, quantitative techniques can be deployed to measure each of these factors through techniques such as correlational or regression analyses. Here, the use of quantitative techniques without identifying the diverse factors influencing patient decisions would be premature. Qualitative techniques thus have a key role to play in investigations of complex realities and in conducting rich exploratory studies while embracing rigorous and philosophically grounded methodologies.

Third, apart from subjective, nebulous, and complex phenomena, qualitative research techniques are also effective in making sense of irrational, illogical, and emotional phenomena. These play an important role in understanding logics at work among patients, their families, and societies. Qualitative research techniques are aided by their ability to shift focus away from the individual as a unit of analysis to the larger social, cultural, political, economic, and structural forces at work in health. As health-care practitioners and researchers focused on biological, physiological, disease and therapeutic processes, sociocultural, political, and economic conditions are often peripheral or ignored in day-to-day clinical work. However, it is within these latter processes that both health-care practices and patient lives are entrenched. Qualitative researchers are particularly adept at identifying the structural conditions such as the social, cultural, political, local, and economic conditions which contribute to health care and experiences of disease and illness.

For example, the decision to delay treatment by a patient may be understood as an irrational choice impacting his/her chances of survival, but the same may be a result of the patient treating their child's education as a financial priority over his/her own health. While this appears as an “emotional” choice, qualitative researchers try to understand the social and cultural factors that structure, inform, and justify such choices. Rather than assuming that it is an irrational choice, qualitative researchers try to understand the norms and logical grounds on which the patient is making this decision. By foregrounding such logics, stories, fears, and desires, qualitative research expands our analytic precision in learning about complex social worlds, recognizing reasons for medical successes and failures, and interrogating our assumptions about human behavior. These in turn can prove useful in arriving at conclusive, actionable findings which can inform institutional and public health policies and have a very important role to play in any change and transformation we may wish to bring to the societies in which we work.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- 1. Shapin S, Schaffer S. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1985. Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Uberoi JP. Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1978. Science and Culture. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Poovey M. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1998. A History of the Modern Fact: Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences of Wealth and Society. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Creswell JW. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Bhangu S, Bisshop A, Engelmann S, Meulemans G, Reinert H, Thibault-Picazo Y. Feeling/Following: Creative Experiments and Material Play, Anthropocene Curriculum, Haus der Kulturen der Welt. Max Planck Institute for the History of Science; The Anthropocene Issue. 2016 [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (583.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Qualitative study.

Steven Tenny ; Janelle M. Brannan ; Grace D. Brannan .

Affiliations

Last Update: September 18, 2022 .

- Introduction

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. [1] Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypothenar to further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a standalone study, purely relying on qualitative data, or part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and applications of qualitative research.

Qualitative research, at its core, asks open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers, such as "how" and "why." [2] Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions, qualitative research design is often not linear like quantitative design. [2] One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. [3] Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be complex to capture accurately and quantitatively. In contrast, a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a particular time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify, and it is essential to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore "compete" against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each other, qualitative and quantitative work are neither necessarily opposites, nor are they incompatible. [4] While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites and certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated.

Qualitative Research Approaches

Ethnography

Ethnography as a research design originates in social and cultural anthropology and involves the researcher being directly immersed in the participant’s environment. [2] Through this immersion, the ethnographer can use a variety of data collection techniques to produce a comprehensive account of the social phenomena that occurred during the research period. [2] That is to say, the researcher’s aim with ethnography is to immerse themselves into the research population and come out of it with accounts of actions, behaviors, events, etc, through the eyes of someone involved in the population. Direct involvement of the researcher with the target population is one benefit of ethnographic research because it can then be possible to find data that is otherwise very difficult to extract and record.

Grounded theory

Grounded Theory is the "generation of a theoretical model through the experience of observing a study population and developing a comparative analysis of their speech and behavior." [5] Unlike quantitative research, which is deductive and tests or verifies an existing theory, grounded theory research is inductive and, therefore, lends itself to research aimed at social interactions or experiences. [3] [2] In essence, Grounded Theory’s goal is to explain how and why an event occurs or how and why people might behave a certain way. Through observing the population, a researcher using the Grounded Theory approach can then develop a theory to explain the phenomena of interest.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is the "study of the meaning of phenomena or the study of the particular.” [5] At first glance, it might seem that Grounded Theory and Phenomenology are pretty similar, but the differences can be seen upon careful examination. At its core, phenomenology looks to investigate experiences from the individual's perspective. [2] Phenomenology is essentially looking into the "lived experiences" of the participants and aims to examine how and why participants behaved a certain way from their perspective. Herein lies one of the main differences between Grounded Theory and Phenomenology. Grounded Theory aims to develop a theory for social phenomena through an examination of various data sources. In contrast, Phenomenology focuses on describing and explaining an event or phenomenon from the perspective of those who have experienced it.

Narrative research

One of qualitative research’s strengths lies in its ability to tell a story, often from the perspective of those directly involved in it. Reporting on qualitative research involves including details and descriptions of the setting involved and quotes from participants. This detail is called a "thick" or "rich" description and is a strength of qualitative research. Narrative research is rife with the possibilities of "thick" description as this approach weaves together a sequence of events, usually from just one or two individuals, hoping to create a cohesive story or narrative. [2] While it might seem like a waste of time to focus on such a specific, individual level, understanding one or two people’s narratives for an event or phenomenon can help to inform researchers about the influences that helped shape that narrative. The tension or conflict of differing narratives can be "opportunities for innovation." [2]

Research Paradigm

Research paradigms are the assumptions, norms, and standards underpinning different research approaches. Essentially, research paradigms are the "worldviews" that inform research. [4] It is valuable for qualitative and quantitative researchers to understand what paradigm they are working within because understanding the theoretical basis of research paradigms allows researchers to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the approach being used and adjust accordingly. Different paradigms have different ontologies and epistemologies. Ontology is defined as the "assumptions about the nature of reality,” whereas epistemology is defined as the "assumptions about the nature of knowledge" that inform researchers' work. [2] It is essential to understand the ontological and epistemological foundations of the research paradigm researchers are working within to allow for a complete understanding of the approach being used and the assumptions that underpin the approach as a whole. Further, researchers must understand their own ontological and epistemological assumptions about the world in general because their assumptions about the world will necessarily impact how they interact with research. A discussion of the research paradigm is not complete without describing positivist, postpositivist, and constructivist philosophies.

Positivist versus postpositivist

To further understand qualitative research, we must discuss positivist and postpositivist frameworks. Positivism is a philosophy that the scientific method can and should be applied to social and natural sciences. [4] Essentially, positivist thinking insists that the social sciences should use natural science methods in their research. It stems from positivist ontology, that there is an objective reality that exists that is wholly independent of our perception of the world as individuals. Quantitative research is rooted in positivist philosophy, which can be seen in the value it places on concepts such as causality, generalizability, and replicability.

Conversely, postpositivists argue that social reality can never be one hundred percent explained, but could be approximated. [4] Indeed, qualitative researchers have been insisting that there are “fundamental limits to the extent to which the methods and procedures of the natural sciences could be applied to the social world,” and therefore, postpositivist philosophy is often associated with qualitative research. [4] An example of positivist versus postpositivist values in research might be that positivist philosophies value hypothesis-testing, whereas postpositivist philosophies value the ability to formulate a substantive theory.

Constructivist

Constructivism is a subcategory of postpositivism. Most researchers invested in postpositivist research are also constructivist, meaning they think there is no objective external reality that exists but instead that reality is constructed. Constructivism is a theoretical lens that emphasizes the dynamic nature of our world. "Constructivism contends that individuals' views are directly influenced by their experiences, and it is these individual experiences and views that shape their perspective of reality.” [6] constructivist thought focuses on how "reality" is not a fixed certainty and how experiences, interactions, and backgrounds give people a unique view of the world. Constructivism contends, unlike positivist views, that there is not necessarily an "objective"reality we all experience. This is the ‘relativist’ ontological view that reality and our world are dynamic and socially constructed. Therefore, qualitative scientific knowledge can be inductive as well as deductive.” [4]

So why is it important to understand the differences in assumptions that different philosophies and approaches to research have? Fundamentally, the assumptions underpinning the research tools a researcher selects provide an overall base for the assumptions the rest of the research will have. It can even change the role of the researchers. [2] For example, is the researcher an "objective" observer, such as in positivist quantitative work? Or is the researcher an active participant in the research, as in postpositivist qualitative work? Understanding the philosophical base of the study undertaken allows researchers to fully understand the implications of their work and their role within the research and reflect on their positionality and bias as it pertains to the research they are conducting.

Data Sampling

The better the sample represents the intended study population, the more likely the researcher is to encompass the varying factors. The following are examples of participant sampling and selection: [7]

- Purposive sampling- selection based on the researcher’s rationale for being the most informative.

- Criterion sampling selection based on pre-identified factors.

- Convenience sampling- selection based on availability.

- Snowball sampling- the selection is by referral from other participants or people who know potential participants.

- Extreme case sampling- targeted selection of rare cases.

- Typical case sampling selection based on regular or average participants.

Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative research uses several techniques, including interviews, focus groups, and observation. [1] [2] [3] Interviews may be unstructured, with open-ended questions on a topic, and the interviewer adapts to the responses. Structured interviews have a predetermined number of questions that every participant is asked. It is usually one-on-one and appropriate for sensitive topics or topics needing an in-depth exploration. Focus groups are often held with 8-12 target participants and are used when group dynamics and collective views on a topic are desired. Researchers can be participant-observers to share the experiences of the subject or non-participants or detached observers.

While quantitative research design prescribes a controlled environment for data collection, qualitative data collection may be in a central location or the participants' environment, depending on the study goals and design. Qualitative research could amount to a large amount of data. Data is transcribed, which may then be coded manually or using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software or CAQDAS such as ATLAS.ti or NVivo. [8] [9] [10]

After the coding process, qualitative research results could be in various formats. It could be a synthesis and interpretation presented with excerpts from the data. [11] Results could also be in the form of themes and theory or model development.

Dissemination

The healthcare team can use two reporting standards to standardize and facilitate the dissemination of qualitative research outcomes. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research or COREQ is a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. [12] The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is a checklist covering a more comprehensive range of qualitative research. [13]

Applications

Many times, a research question will start with qualitative research. The qualitative research will help generate the research hypothesis, which can be tested with quantitative methods. After the data is collected and analyzed with quantitative methods, a set of qualitative methods can be used to dive deeper into the data to better understand what the numbers truly mean and their implications. The qualitative techniques can then help clarify the quantitative data and also help refine the hypothesis for future research. Furthermore, with qualitative research, researchers can explore poorly studied subjects with quantitative methods. These include opinions, individual actions, and social science research.

An excellent qualitative study design starts with a goal or objective. This should be clearly defined or stated. The target population needs to be specified. A method for obtaining information from the study population must be carefully detailed to ensure no omissions of part of the target population. A proper collection method should be selected that will help obtain the desired information without overly limiting the collected data because, often, the information sought is not well categorized or obtained. Finally, the design should ensure adequate methods for analyzing the data. An example may help better clarify some of the various aspects of qualitative research.

A researcher wants to decrease the number of teenagers who smoke in their community. The researcher could begin by asking current teen smokers why they started smoking through structured or unstructured interviews (qualitative research). The researcher can also get together a group of current teenage smokers and conduct a focus group to help brainstorm factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke (qualitative research).

In this example, the researcher has used qualitative research methods (interviews and focus groups) to generate a list of ideas of why teens start to smoke and factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke. Next, the researcher compiles this data. The research found that, hypothetically, peer pressure, health issues, cost, being considered "cool," and rebellious behavior all might increase or decrease the likelihood of teens starting to smoke.

The researcher creates a survey asking teen participants to rank how important each of the above factors is in either starting smoking (for current smokers) or not smoking (for current nonsmokers). This survey provides specific numbers (ranked importance of each factor) and is thus a quantitative research tool.

The researcher can use the survey results to focus efforts on the one or two highest-ranked factors. Let us say the researcher found that health was the primary factor that keeps teens from starting to smoke, and peer pressure was the primary factor that contributed to teens starting smoking. The researcher can go back to qualitative research methods to dive deeper into these for more information. The researcher wants to focus on keeping teens from starting to smoke, so they focus on the peer pressure aspect.

The researcher can conduct interviews and focus groups (qualitative research) about what types and forms of peer pressure are commonly encountered, where the peer pressure comes from, and where smoking starts. The researcher hypothetically finds that peer pressure often occurs after school at the local teen hangouts, mostly in the local park. The researcher also hypothetically finds that peer pressure comes from older, current smokers who provide the cigarettes.

The researcher could further explore this observation made at the local teen hangouts (qualitative research) and take notes regarding who is smoking, who is not, and what observable factors are at play for peer pressure to smoke. The researcher finds a local park where many local teenagers hang out and sees that the smokers tend to hang out in a shady, overgrown area of the park. The researcher notes that smoking teenagers buy their cigarettes from a local convenience store adjacent to the park, where the clerk does not check identification before selling cigarettes. These observations fall under qualitative research.

If the researcher returns to the park and counts how many individuals smoke in each region, this numerical data would be quantitative research. Based on the researcher's efforts thus far, they conclude that local teen smoking and teenagers who start to smoke may decrease if there are fewer overgrown areas of the park and the local convenience store does not sell cigarettes to underage individuals.

The researcher could try to have the parks department reassess the shady areas to make them less conducive to smokers or identify how to limit the sales of cigarettes to underage individuals by the convenience store. The researcher would then cycle back to qualitative methods of asking at-risk populations their perceptions of the changes and what factors are still at play, and quantitative research that includes teen smoking rates in the community and the incidence of new teen smokers, among others. [14] [15]

Qualitative research functions as a standalone research design or combined with quantitative research to enhance our understanding of the world. Qualitative research uses techniques including structured and unstructured interviews, focus groups, and participant observation not only to help generate hypotheses that can be more rigorously tested with quantitative research but also to help researchers delve deeper into the quantitative research numbers, understand what they mean, and understand what the implications are. Qualitative research allows researchers to understand what is going on, especially when things are not easily categorized. [16]

- Issues of Concern

As discussed in the sections above, quantitative and qualitative work differ in many ways, including the evaluation criteria. There are four well-established criteria for evaluating quantitative data: internal validity, external validity, reliability, and objectivity. Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability are the correlating concepts in qualitative research. [4] [11] The corresponding quantitative and qualitative concepts can be seen below, with the quantitative concept on the left and the qualitative concept on the right:

- Internal validity: Credibility

- External validity: Transferability

- Reliability: Dependability

- Objectivity: Confirmability

In conducting qualitative research, ensuring these concepts are satisfied and well thought out can mitigate potential issues from arising. For example, just as a researcher will ensure that their quantitative study is internally valid, qualitative researchers should ensure that their work has credibility.

Indicators such as triangulation and peer examination can help evaluate the credibility of qualitative work.

- Triangulation: Triangulation involves using multiple data collection methods to increase the likelihood of getting a reliable and accurate result. In our above magic example, the result would be more reliable if we interviewed the magician, backstage hand, and the person who "vanished." In qualitative research, triangulation can include telephone surveys, in-person surveys, focus groups, and interviews and surveying an adequate cross-section of the target demographic.

- Peer examination: A peer can review results to ensure the data is consistent with the findings.

A "thick" or "rich" description can be used to evaluate the transferability of qualitative research, whereas an indicator such as an audit trail might help evaluate the dependability and confirmability.

- Thick or rich description: This is a detailed and thorough description of details, the setting, and quotes from participants in the research. [5] Thick descriptions will include a detailed explanation of how the study was conducted. Thick descriptions are detailed enough to allow readers to draw conclusions and interpret the data, which can help with transferability and replicability.

- Audit trail: An audit trail provides a documented set of steps of how the participants were selected and the data was collected. The original information records should also be kept (eg, surveys, notes, recordings).

One issue of concern that qualitative researchers should consider is observation bias. Here are a few examples:

- Hawthorne effect: The effect is the change in participant behavior when they know they are being observed. Suppose a researcher wanted to identify factors that contribute to employee theft and tell the employees they will watch them to see what factors affect employee theft. In that case, one would suspect employee behavior would change when they know they are being protected.

- Observer-expectancy effect: Some participants change their behavior or responses to satisfy the researcher's desired effect. This happens unconsciously for the participant, so it is essential to eliminate or limit the transmission of the researcher's views.

- Artificial scenario effect: Some qualitative research occurs in contrived scenarios with preset goals. In such situations, the information may not be accurate because of the artificial nature of the scenario. The preset goals may limit the qualitative information obtained.

- Clinical Significance

Qualitative or quantitative research helps healthcare providers understand patients and the impact and challenges of the care they deliver. Qualitative research provides an opportunity to generate and refine hypotheses and delve deeper into the data generated by quantitative research. Qualitative research is not an island apart from quantitative research but an integral part of research methods to understand the world around us. [17]

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Qualitative research is essential for all healthcare team members as all are affected by qualitative research. Qualitative research may help develop a theory or a model for health research that can be further explored by quantitative research. Much of the qualitative research data acquisition is completed by numerous team members, including social workers, scientists, nurses, etc. Within each area of the medical field, there is copious ongoing qualitative research, including physician-patient interactions, nursing-patient interactions, patient-environment interactions, healthcare team function, patient information delivery, etc.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Steven Tenny declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Janelle Brannan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Grace Brannan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Tenny S, Brannan JM, Brannan GD. Qualitative Study. [Updated 2022 Sep 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022] Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. Crider K, Williams J, Qi YP, Gutman J, Yeung L, Mai C, Finkelstain J, Mehta S, Pons-Duran C, Menéndez C, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Feb 1; 2(2022). Epub 2022 Feb 1.

- Macromolecular crowding: chemistry and physics meet biology (Ascona, Switzerland, 10-14 June 2012). [Phys Biol. 2013] Macromolecular crowding: chemistry and physics meet biology (Ascona, Switzerland, 10-14 June 2012). Foffi G, Pastore A, Piazza F, Temussi PA. Phys Biol. 2013 Aug; 10(4):040301. Epub 2013 Aug 2.

- The future of Cochrane Neonatal. [Early Hum Dev. 2020] The future of Cochrane Neonatal. Soll RF, Ovelman C, McGuire W. Early Hum Dev. 2020 Nov; 150:105191. Epub 2020 Sep 12.

- Review Invited review: Qualitative research in dairy science-A narrative review. [J Dairy Sci. 2023] Review Invited review: Qualitative research in dairy science-A narrative review. Ritter C, Koralesky KE, Saraceni J, Roche S, Vaarst M, Kelton D. J Dairy Sci. 2023 Sep; 106(9):5880-5895. Epub 2023 Jul 18.

- Review Participation in environmental enhancement and conservation activities for health and well-being in adults: a review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016] Review Participation in environmental enhancement and conservation activities for health and well-being in adults: a review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Husk K, Lovell R, Cooper C, Stahl-Timmins W, Garside R. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 May 21; 2016(5):CD010351. Epub 2016 May 21.

Recent Activity

- Qualitative Study - StatPearls Qualitative Study - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Relevance of Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Traditional, quantitative concepts of validity and reliability are frequently used to critique qualitative research, often leading to criticisms of lacking scientific rigor, insufficient methodological justification, lack of transparency in analysis, and potential for researcher bias.

Alternative terminology is proposed to better capture the principles of rigor and credibility within the qualitative paradigm :

Validity in Qualitative Research

Validity focuses on the truthfulness and accuracy of findings.

Quantitative research, with its focus on objectivity and generalizability, prioritizes internal validity to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

This involves carefully controlling extraneous factors to ensure the observed effects can be confidently attributed to the independent variable.

Qualitative research embraces a different epistemological framework, emphasizing subjectivity, contextual understanding, and the exploration of lived experiences.

In this paradigm, validity focuses on faithfully representing the perspectives, meanings, and interpretations of the participants.

The underlying goal remains to produce research that is rigorous, credible, and insightful, contributing meaningfully to our understanding of complex social phenomena.

This involves ensuring the research process and findings are trustworthy, authentic, and rigorous.

1. Trustworthiness

Validity in qualitative research, often referred to as trustworthiness , assesses the accuracy of findings as representations of the data, participants’ lives, cultures, and contexts.

Trustworthiness is an overarching concept that encompasses both credibility and transferability , reflecting the overall quality and integrity of the research process and findings. It signifies that the research is conducted ethically, rigorously, and transparently.

A central concept in achieving trustworthiness is methodological integrity , which emphasizes the importance of using methods and procedures that are consistent with the research question, goals, and inquiry approach.

Methodological integrity focuses on two key components: fidelity to the subject matter and utility of research contributions .

Fidelity to the Subject Matter

Fidelity to the subject matter emphasizes collecting data that capture the diversity and complexity of the phenomenon under study.

Qualitative research underscores the commitment to representing participants’ authentic perspectives and experiences faithfully and respectfully.

This goes beyond simply recording their words; it involves capturing the depth, complexity, and meaning embedded within their narratives.

Fidelity to the subject matter must demonstratee that the data is adequate to answer the research question and that the researcher’s perspectives were managed during both data collection and analysis to minimize bias.

Researchers should show that the findings are grounded in the evidence by using rich quotes and detailed descriptions of their engagement with the data. This is also referred to as thick, lush description.

Thick description involves going beyond surface-level observations to provide rich, detailed accounts of the data. This includes not just what participants say but also the context of their utterances, their emotional tone, and the nonverbal cues that contribute to meaning.

Thick description enhances authenticity by painting a vivid picture of the participants’ lived experiences, allowing readers to grasp the nuances and complexities of their perspectives.

For instance, if studying a phenomenon like “pain,” researchers should acknowledge whether they perceive it as a real, tangible experience or a socially constructed one.

This understanding shapes data collection and analysis, ensuring the findings remain true to the participants’ realities.

Utility of Research Contributions

Utility refers to the usefulness and value of the research findings.

Studies with high utility introduce new insights, expand upon existing knowledge, or offer practical applications for researchers and practitioners.

The utility of a study’s findings is evaluated in relation to its aims and tradition of inquiry. For example, studies with a critical approach should contribute to an awareness of power dynamics and oppression.

A study might have high fidelity by providing compelling descriptions of student study challenges, but if it only offers obvious or commonly known study strategies, it would have low utility.

Ideally, a study would possess both high fidelity and utility, providing a clear understanding of the phenomenon while also offering valuable contributions to the field.

Strategies to enhance trustworthiness and methodological integrity:

- Using rigorous research methods: Selecting and justifying the chosen qualitative method based on its established rigor enhances credibility and demonstrates a commitment to methodological soundness.

- Reflexivity: Critically examining personal biases, values, and experiences helps researchers identify potential influences on their interpretations and ensure that findings are not solely a product of their own perspectives.

- Promoting authentic voice: Researchers should strive to create conditions that allow participants to express themselves openly and honestly.

- Truth Value: Acknowledging the existence of multiple perspectives and ensuring that the findings accurately represent the participants’ views and experiences.

- Member checking: Involving participants in the research process by sharing findings with them to confirm the accuracy of interpretations.

- Triangulation: Utilizing multiple data sources, methods, or researchers to corroborate findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

- Prolonged engagement: Spending sufficient time in the field to develop a deep understanding of the context and build rapport with participants, which can lead to more insightful and trustworthy data.

- Using thick, rich descriptions: Providing detailed narratives, representative quotes, and thorough descriptions of the context helps readers understand the phenomenon and assess the credibility and transferability of the findings.

- Ensuring continuous data saturation : Immersing oneself in the data, constantly refining understanding, and remaining open to gathering more data if needed ensure that the data adequately captures the complexity and diversity of the phenomenon under study.

2. Transferability

Transferability in qualitative research is similar to external validity in quantitative research. It refers to the extent to which the findings can be applied or transferred to other contexts, settings, or groups.

While generalizability in the statistical sense is not a primary goal of qualitative research, providing sufficient details about the study context, sample, and methods can enhance the transferability of the findings.

Qualitative research prioritizes transferability over generalizability. Transferability acknowledges the context-specific nature of findings and encourages readers to consider the potential applicability of the research to other settings.

Researchers can promote transferability by providing thick descriptions of the context, the participants, and the research process.

Transferability is an external consideration, inviting readers to evaluate the potential applicability of the findings to other settings.

Promoting Transferability :

- Providing thick description: Offering detailed contextual information about the setting, participants, and findings, allowing readers to assess the potential relevance to other settings.

- Purposive sampling: Selecting participants who represent a range of perspectives and experiences relevant to the research question. This can enhance the applicability of the findings to a broader population.

- Discussing limitations: Openly acknowledging the specificities of the research context and the potential limitations of applying the findings to other settings.

Barriers to Validity in Qualitative Research

Researchers should be aware of potential threats to validity and take steps to mitigate them. Some common pitfalls include:

Researcher Bias and Perspective

Researchers’ own beliefs, values, and assumptions can influence data collection, analysis, and interpretation, potentially distorting the findings.

Acknowledging and managing these perspectives is crucial for ensuring fidelity to the subject matter.

This aligns with the concept of reflexivity in qualitative research, which encourages researchers to critically examine their own positionality and its potential impact on the research process.

Inadequate Sampling and Representation

If the sample of participants is not representative of the population of interest or if the data collected are incomplete or insufficiently detailed, the findings might lack conceptual heterogeneity and fail to capture the full range of perspectives and experiences relevant to the research question.

This emphasizes the importance of purposive sampling in qualitative research, aiming to select participants who can provide rich and diverse insights into the phenomenon under study.

Superficial Data and Lack of Thick Description

When data are presented in a cursory or overly simplistic manner, without sufficient detail and context, the validity of the findings can be questioned.

This reductionism can stem from a lack of thorough data analysis or a tendency to prioritize brevity over depth in reporting the results

Thick description , a cornerstone of qualitative research, involves providing rich, detailed accounts of the data, capturing the nuances of the participants’ experiences and the context in which they occur.

Selective Anecdotalism and Cherry-Picking

Choosing to focus on specific anecdotes or data points that support the researcher’s preconceived notions while ignoring contradictory evidence can severely undermine validity.

This selective reporting distorts the overall picture and presents a biased view of the findings.

Qualitative researchers are expected to analyze and present data comprehensively, acknowledging all relevant themes and perspectives, even those that challenge their initial assumptions.

Perceived Coercion and Power Dynamics

In qualitative research, especially when dealing with sensitive topics or vulnerable populations, power imbalances between the researcher and participants can influence the data obtained.

If participants feel pressured or coerced to provide certain answers, their responses might lack authenticity and fail to reflect their genuine perspectives.

This underscores the importance of establishing trust and rapport with participants, ensuring they feel safe and comfortable to share their experiences openly and honestly.

Attrition in Longitudinal Studies

In qualitative studies that involve multiple data collection points over time, participant attrition can threaten validity.

If participants drop out of the study for reasons related to the research topic, the remaining sample might become biased, and the findings might not accurately reflect the experiences of the original group.

Addressing attrition requires careful planning and implementation of strategies to maintain participant engagement and minimize drop-out rates.

Reliability in Qualitative Research

Traditional quantitative definition, focused on the replicability of results, is not directly applicable to qualitative inquiry.

This is because qualitative research often explores complex, context-specific phenomena that are influenced by multiple subjective interpretations.

In qualitative research, reliability refers to the consistency and stability of the research proces s and findings.

Reliability in qualitative research concerns consistency and dependability in data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Dependability

Instead of striving for replicability, qualitative research prioritizes dependability , which focuses on the consistency and trustworthiness of the research process itself.

This involves demonstrating that the methods used were appropriate, that the data were collected and analyzed systematically, and that the interpretations are well-supported by the evidence.

Researchers can establish dependability using methods such as audit trails so readers can see the research process is logical and traceable (Koch, 1994).

Strategies for promoting reliability in qualitative research:

- Standardized procedures: Establishing clear and consistent protocols for data collection, analysis, and interpretation can help ensure that the research process is systematic and replicable.

- Rigorous training for researchers in qualitative methodologies, data analysis techniques, and reflexive practices to manage their own perspectives and biases.

- Audit trails: An audit trail provides evidence of the decisions made by the researcher regarding theory, research design, and data collection, as well as the steps they have chosen to manage, analyze, and report data. This includes maintaining detailed field notes, documenting coding decisions, and preserving raw data for future reference.

- Transparency in reporting: Clearly articulating the research design, data collection methods, analytical procedures, and the researcher’s own reflexivity allows readers to assess the trustworthiness of the findings and understand the logic behind the interpretations.

- Interrater reliability (optional): While not universally employed in qualitative research, involving multiple coders to analyze the data can provide insights into the consistency of interpretations. However, it’s important to note that complete agreement might not be the goal, as differing perspectives can enrich the analysis. Discrepancies can be discussed and resolved, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the data.

Barriers to Reliability in Qualitative Research

Subjectivity in data collection and analysis.

One of the main barriers to reliability stems from the subjective nature of qualitative data collection and analysis.

Unlike quantitative research with its standardized procedures, qualitative research often involves a deep engagement with participants and data, relying on the researcher’s interpretation and judgment.

This introduces potential for inconsistency in data coding and interpretation, especially when multiple researchers are involved.

Researchers’ personal backgrounds, experiences, and theoretical orientations can influence their interpretation of the data.

What one researcher considers significant or meaningful may differ from another researcher’s perspective.

This subjectivity can lead to variations in how data is collected, coded, and analyzed, especially when multiple researchers are involved in a study.

Lack of Detailed Documentation

Qualitative studies often involve complex and iterative processes of data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Without a clear and comprehensive record of these processes, it becomes challenging for others to assess the dependability and consistency of the findings.

Insufficient documentation of data collection methods, coding schemes, analytical decisions, and researcher reflexivity can hinder the ability to establish reliability.

A detailed audit trail, which provides a transparent account of the research process, is crucial for demonstrating the trustworthiness and credibility of qualitative findings.

Lack of detailed documentation of the research process, including data collection methods, coding schemes, and analytical decisions, can hinder reliability.

Without such documentation, it becomes difficult for other researchers to replicate the study or assess the reliability of the conclusions drawn.

Reductionism in Data Representation

Reductionism, or oversimplifying complex data by relying on short quotes and superficial descriptions, can also compromise reliability.

Such reductive practices can distort the richness and nuance of the data, leading to potentially misleading interpretations.

Qualitative research often yields rich, nuanced, and context-specific data that cannot be easily reduced to simple categories or short quotes.

However, in an effort to present findings concisely, researchers may resort to reductive practices that distort the true nature of the data.

Relying on short quotes or superficial descriptions without providing sufficient context can lead to misinterpretations and oversimplification.

Such reductive practices fail to capture the complexity and depth of the participants’ experiences and perspectives.

As a result, the reliability of the findings may be questioned, as they may not accurately represent the full range of data collected.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Learn how to apply deductive and inductive strategies to qualitative data analysis, with examples and tips. Deductive analysis involves applying predetermined codes or theory to the data, while inductive analysis involves allowing codes and concepts to emerge from the data.

A general inductive approach for analysis of qualitative evaluation data is described. The purposes for using an inductive approach are to (a) condense raw textual data into a brief, summary format; (b) establish clear links between the evaluation or research objectives and the summary findings derived from the raw data; and (c) develop a framework of the underlying structure of experiences or ...

Deductive and inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. In C. Vanover, P. Mihas, & J. Saldaña (Eds.), Analyzing and interpreting qualitative data: After the interview: SAGE. ... I teach intermediate and advanced qualitative research methods, as well as policy analysis and evaluation at the doctoral level, and I teach research methods ...

Inductive analysis is a key characteristic and strength of qualitative research. Inductive analysis involves reading through the data and identifying codes, categories, patterns, and themes as they emerge (Saldaña and Omasta, 2017; Miles et al., 2020). In other words, codes and categories are not predetermined, but are instead identified and ...

To this end, qualitative work tends to be inductive, that is, research questions are intentionally open ended to allow the researcher to collect information even when its relevance to understanding the phenomenon of interest may have been unforseen. 8 Rather than investigate a predetermined theory through hypothesis testing, inductive inquiry ...

Qualitative research is a methodology for scientific inquiry that emphasizes the depth and richness of context and voice in understanding social phenomena. 3 This methodology is constructive or interpretive , aiming to unveil the "what," "why," "when," "where," "who," and "how" (or the "5W1H") behind social behaviors ...

Qualitative research methods refer to techniques of investigation that rely on nonstatistical and nonnumerical methods of data collection, analysis, and evidence production. ... Rather than establishing one or the other factor as more important, qualitative methods are open-ended, inductive (ground-up), and empirical. ...

Inductive research approach. When there is little to no existing literature on a topic, it is common to perform inductive research, because there is no theory to test. The inductive approach consists of three stages: ... Qualitative research is expressed in words to gain understanding. 8579. Explanatory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

In qualitative research, the term deductive generally refers to a systematic approach wherein codes or categories of meaning are predetermined, derived from an explicit theoretical framework in order to confirm, expand, or refine the framing theory, whereas in an inductive approach, categories and structure of meaning emerge from the dataset ...

The inductive approach reflects frequently reported patterns used in qualitative data analysis. Most inductive studies report a model that has between three and eight main categories in the ...

An outline of a general inductive approach for qualitative data analysis is described and details provided about the assumptions and procedures used. The purposes for using an inductive approach are to (1) to condense extensive and varied raw text data into a brief, summary format; (2) to establish clear links between the research objectives ...

Inductive reasoning is commonly linked to qualitative research, but both quantitative and qualitative research use a mix of different types of reasoning. Tip Due to its reliance on making observations and searching for patterns, inductive reasoning is at high risk for research biases , particularly confirmation bias .

Revised on September 5, 2024. Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research. Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research, which ...

Qualitative research is a method of inquiry used in various disciplines, including social sciences, education, and health, to explore and understand human behavior, experiences, and social phenomena. ... Two different approaches are used to generate themes: inductive and deductive. An inductive approach allows themes to emerge from the data. In ...

Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research. January 2013. Organizational Research Methods 16 (1):15-31. 16 (1):15-31. DOI: 10.1177/1094428112452151. Authors: Dennis A. Gioia. Penn State Great ...

Qualitative research draws from interpretivist and constructivist paradigms, seeking to deeply understand a research subject rather than predict outcomes, as in the positivist paradigm (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). ... Their analysis follows the inductive type of the phenomenological approach. The first step of their analysis is to read the entire ...

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems.[1] Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypothenar to further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences ...

Qualitative research can be defined as a study which is conducted in a natural setting. The researcher, in effect, becomes the instrument for data collection. ... use of the inductive approach to research, the researcher begins with specific observations and measures, and then moves to detecting themes and patterns in the data. This allows the

Inductive content analysis (ICA), or qualitative content analysis, is a method of qualitative data analysis well-suited to use in health-related research, particularly in relatively small-scale ...

qualitative researchers D. F. Vears1, 2 & L. Gillam2, 3 Abstract Inductive content analysis (ICA), or qualitative content analysis, is a method of qualitative data analysis well-suited to use in health-related research, particularly in relatively small-scale, non-complex research done by health professionals undertaking research-focused degree ...

This paper reports these findings, presents this grounded theory of inductive qualitative research education, and discusses the implications of the findings of this meta-analysis for those teaching and researching qualitative research. Keywords: Qualitative Research, Student Experience, Learning, Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, Constructivist ...

In its purest form qualitative analysis is led by an inductive approach (see Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Simply put, "Inductive analysis means that the patterns, themes, and categories of analysis come from the data; they emerge out of the data rather than being imposed on them prior to data collection and analysis" (Patton, 1980, p. 306 ...

Traditional, quantitative concepts of validity and reliability are frequently used to critique qualitative research, often leading to criticisms of lacking scientific rigor, insufficient methodological justification, lack of transparency in analysis, and potential for researcher bias.. Alternative terminology is proposed to better capture the principles of rigor and credibility within the ...