- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 02 October 2020

Development of a new model on utilizing online learning platforms to improve students’ academic achievements and satisfaction

- Hassan Abuhassna ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5774-3652 1 ,

- Waleed Mugahed Al-Rahmi 1 ,

- Noraffandy Yahya 1 ,

- Megat Aman Zahiri Megat Zakaria 1 ,

- Azlina Bt. Mohd Kosnin 1 &

- Mohamad Darwish 2

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education volume 17 , Article number: 38 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

178k Accesses

111 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

This research aims to explore and investigate potential factors influencing students’ academic achievements and satisfaction with using online learning platforms. This study was constructed based on Transactional Distance Theory (TDT) and Bloom’s Taxonomy Theory (BTT). This study was conducted on 243 students using online learning platforms in higher education. This research utilized a quantitative research method. The model of this research illustrates eleven factors on using online learning platforms to improve students’ academic achievements and satisfaction. The findings showed that the students’ background, experience, collaborations, interactions, and autonomy positively affected students’ satisfaction. Moreover, effects of the students’ application, remembering, understanding, analyzing, and satisfaction was positively aligned with students’ academic achievements. Consequently, the empirical findings present a strong support to the integrative association between TDT and BTT theories in relation to using online learning platforms to improve students’ academic achievements and satisfaction, which could help decision makers in universities and higher education and colleges to plan, evaluate, and implement online learning platforms in their institutions.

Introduction

Higher education organizations over the previous two decades have offered full courses online as an integral part of their curricula, besides encouraging the completion throughout the online courses. Additionally, the number of students who are not participating in any courses online has continued to drop over the past few years. Similarly, it is perfectly possible to state that learning online is obviously an educational platform (Allen, Seaman, Poulin, & Straut, 2016 ). Courses online are trying to connect social networking components, experts’ content, because online resources are growing on daily basis. Such courses depend on active participation of a significant number of learners who participate independently in accordance with their education objectives, skills, and previous background and experience (McAuley, Stewart, Siemens, & Cormier, 2010 ). Nevertheless, learners differ in their previous background and experience, along with their education techniques, which clearly influence their online courses results besides their achievement (Kauffman, 2015 ). Consequently, despite the online learning evolution, learning online possibly will not be appropriate for each learner (Bouhnik & Carmi, 2013 ). Nevertheless, while online learning application among academic world has grown rapidly, not enough is identified regarding learners’ previous background and experience in learning online. Not so long ago, investigation concentrated on particular characteristics of learners’ experiences along with beliefs, for instance collaboration with their own instructor, online course quality, or studying with a certain learning management system (LMS) (Alexander & Golja, 2007 ; (Lester & King, 2009 ). Generally, limited courses or a single institution were investigated (Coates, James, & Baldwin, 2005 ; Lee, Yoon, & Lee, 2009 ). Few studies examined bigger sample sizes between one or more particular institutes (Alexander & Golja, 2007 ). Additionally, there is a shortage of researches that examine learners’ previous background and experience comparing face-to-face along with learning online elements, e.g., (Bliuc, Goodyear, & Ellis, 2007 ). The development of learners’ previous background and experience, skills, are realized to be the major advantages for administrative level for learning online.

Similarly, learners’ satisfaction and academic achievement towards learning online attracted considerable attention from scholars who employed several theoretical models in order to evaluate learners’ satisfaction and academic achievements (Abuhassna, Megat, Yahaya, Azlina, & Al-rahmi, 2020 ; Abuhassna & Yahaya, 2018 ; Al-Rahmi, Othman, & Yusuf, 2015a ; Al-Rahmi, Othman, & Yusuf, 2015b ). This present study highlights the effects of online learning platforms on student’s satisfaction, in relation to their background and prior experiences towards online learning platforms to identify learners that are going to be satisfied toward online course. Furthermore, this research explores the effects of transactional distance theory (TDT); student collaboration, student- instructor dialogue or communication, and student autonomy in relation to their satisfaction. Accordingly, this study investigates students’ academic achievements within online platforms, utilizing Bloom theory to measure students’ achievements through four main components, namely, understanding, remembering, applying, and analyzing. This study could have a significant influence on online course design and development. Additionally, this research may influence not only academic online courses but then other educational organizations according to the fact that several organizations offer training courses and solutions online. Both researchers and Instructors will be able to utilize and elaborate in accordance with the preliminary model, which was developed throughout this research, on the effects of online platforms on student’s satisfaction and academic achievements. Advantages of online learning and along with its applications were mentioned in earlier correlated literature (Abuhassna et al., 2020 ;Abuhassna & Yahaya, 2018 ; Al-Rahmi et al., 2018 ). However, despite the growing usage of online platforms, there is a shortage of employing this technology, which creates an issue in itself (Abuhassna & Yahaya, 2018 ; Al-Rahmi et al., 2018 ). Consequently, the research problem lies in the point that a model needs to be created to locate the significant evidence based on the data of student’s background, experiences and interactions within online learning environments which influence their academic performance and satisfaction. Thus, this developed model must be as a guidance for instructors and decision makers in the online education industry in terms of using online platforms to improve students learning experience through online platforms. Bearing in mind these conditions, our major problem was: how could we enhance students online learning experience in relation to both their academic achievements and satisfaction?

Research questions

The major research question that are anticipated to be answered is:

how could we enhance students online learning experience in relation to both their academic achievements and satisfaction?

To be able to answer this question, it is required to examine numerous sub-questions which have been stated as follow:

Q1: What is the relationship between students’ background and students’ satisfaction?

Q2: What is the relationship between students’ experience and students’ satisfaction?

Q3: What is the relationship between students’ collaboration and students’ satisfaction?

Q4: What is the relationship between students’ interaction and students’ satisfaction?

Q5: What is the relationship between students’ autonomy and students’ satisfaction?

Q6: What is the relationship between students’ satisfaction and students’ academic achievements?

Q7: What is the relationship between students’ application and students’ academic achievements?

Q8: What is the relationship between students’ remembering and students’ academic achievements?

Q9: What is the relationship between students’ understanding and students’ academic achievements?

Q10: What is the relationship between students’ analyzing and students’ academic achievements?

Research theory and hypotheses development

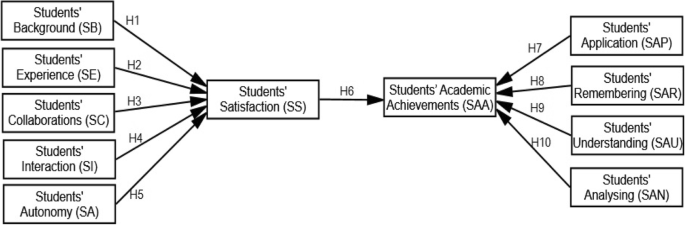

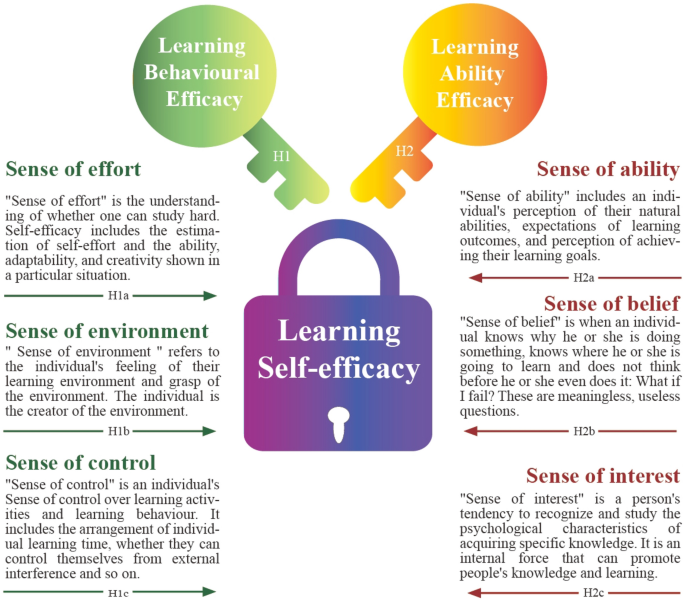

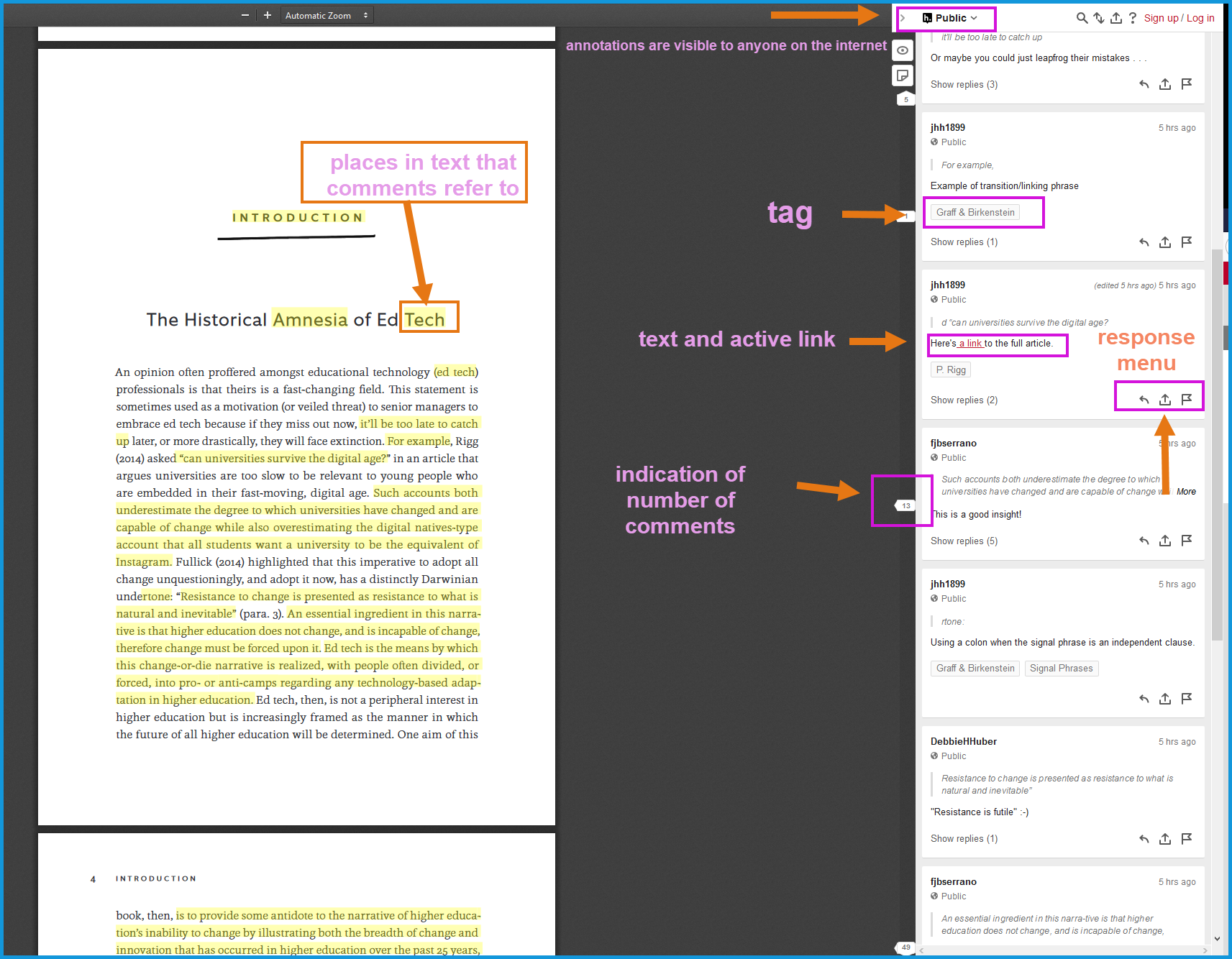

When designing web-courses within online learning instructions or mechanisms in general, educators are left with several decisions and considerations to face, which accordingly affect how students experience instruction, how they construct and process knowledge, how students could be satisfied through this experiment, and how web-based learning courses could enhance their academic achievements. In this study, we construct our theoretical framework according to Moore transactional distance theory (TDT) to measure student’s satisfaction, in addition to Bloom theory components to measure students’ academic achievements. Though the origins of TDT can be traced to the work of Dewey, it is Michael Moore who is identified as the innovator of this theory that first appeared in 1972. In his study and development of the theory, he acknowledged three main components of TDT that work as the base for much of the research on DL. Also, Bloom’s Taxonomy was established in 1956 under the direction of educational psychologist to measure students’ academic achievement (Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill, & Krathwohl, 1956 ). TDT theory has been selected in this study since Transactional distance’s term indicates the geographical space between the student and instructor. Based on the learning understanding, which happens through learner’s interaction with his environment. This theory considers the role of each of these elements (Student’s autonomy, Dialogue, and class structure) whereas these three elements could help to investigate student’s satisfaction. Moore’s ( 1990 ) notion of ‘Transactional Distance’ adopt the distance that happens in all relations in education. The distance in the theory is mainly specified the dialogue’s amount which happens between the student and the teacher, and the structure’s amount in the course design. Which serves the main goal of this study as to enhance students online learning experience in relation to their satisfaction. Whereas, Bloom Theory has been selected in this study in addition to TDT to enhance students online learning experience in relation to their student’s achievements. In a conclusion both methods were implemented to develop and hypothesis this study hypothesis. See Fig. 1 .

Research Model and Hypotheses

Hypothesis of the study

H1: There is a significant relationship between students’ background and students’ satisfaction.

H2: There is a significant relationship between students’ experience and students’ satisfaction.

H3: There is a significant relationship between students’ collaboration and students’ satisfaction.

H4: There is a significant relationship between students’ interaction and students’ satisfaction.

H5: There is a significant relationship between students’ autonomy and students’ satisfaction.

H6: There is a significant relationship between students’ satisfaction and students’ academic achievements.

H7: There is a significant relationship between students’ application and students’ academic achievements.

H8: There is a significant relationship between students’ remembering and students’ academic achievements.

H9: There is a significant relationship between students’ understanding and students’ academic achievements.

H10: There is a significant relationship between students’ analyzing and students’ academic achievements.

Hypothesis developments and literature review

This Section of the study will discuss the study hypothesis and relates each hypothesis to its related studies from the literature.

Students background toward online platforms

Students’ background regarding online platforms in this study is referred to as their readiness and willingness to use and adapt to different online platforms, providing them with the needed support and assistance. Students’ background towards online learning is a crucial component throughout this process, as prior research revealed that there are implementation issues, for instance; the deficiency of qualified lecturers, infrastructure and facilities, in addition to students’ readiness, besides students’ resistance to accept online learning platforms in addition to the Learning Management System (LMS) platforms, as educational tools (Azhari & Ming, 2015 ). However, student demand continued to increase, spreading to global audiences due to its exceptional functionality, flexibility and eventual accessibility (Azhari & Ming, 2015 ). There have been persistent apprehensions regarding online learning quality compared with traditional learning settings. In their research, (Paechter & Maier, 2010 ; Panyajamorn, Suthathip, Kohda, Chongphaisal, & Supnithi, 2018 ) have discovered that Austrian learners continue to prefer traditional learning environments due to communication goals, along with the interpersonal relations preservation. Moreover, (Lau & Shaikh, 2012 ) have discovered that Malaysian learners’ internet efficiency and computer skills, along with their personal demographics like gender, background, level of the study, as well as their financial income lead to a significant difference in their readiness towards online learning platforms. Abuhassna and Yahaya ( 2018 ) claimed that the current technologies in education play an essential role in providing a full online learning experience which is close enough to a face-to-face class in spite of the physical separation of the students from their educator, along with other students. Platforms of online learning lend themselves towards a less hierarchical methodology in education, fulfilling the learning desires of individuals which do not approach new information in a linear or a systematic manner. Platforms of online learning additionally are the most suitable ways for autonomous students (Abuhassna et al., 2020 ; Abuhassna & Yahaya, 2018 ; Paechter & Maier, 2010 ; Panyajamorn et al., 2018 ).

Students experience toward online platforms

Students’ experience in the current research indicates that learners must have prior experience in relation to utilizing online learning platform in their education settings. Thus, students experience towards online learning offers several advantages among themselves and their instructors in strengthening students’ learning experiences especially for isolated learners (Jaques & Salmon, 2007 ; Lau & Shaikh, 2012 ; Salmon, 2011 ; Salmon, 2014 ). Regardless of student recognition of the advantages towards supporting their learning throughout utilizing the technology, difficulties may occur through the boundaries about their technical capabilities and prior experiences towards utilizing the software itself from the perspective of its functionality. As demonstrated over learner’s experience and feedback from several online sessions over the years, this may frequently become a frustration source between both learners and their instructors, as this may make typically uncomplicated duties, for instance, watching a video, uploading a document, and other simple tasks to be progressively complicated for them, having no such prior experience. Furthermore, when filling out evaluations, for instance, online group presentations, the relatively limited capability to communicate face-to-face then to rely on a non-verbal signal along with audience’s body language might be a discouraging component. Nonetheless, the significance of being in a position to participate with other colleagues employing online sessions, which are occasionally nonvisual, for instance; teleconference format is a progressively significant skill in the modern workplace, thus affirming the importance of concise, clear, intensive interactions skills (Salmon, 2011 ; Salmon, 2014 ).

Student collaboration among themselves in online platforms

Students’ collaborations in the current study refers to the communication and feedback among themselves in online platforms. To refine and measure transactional distance using a survey tool, (Rabinovich, 2009 ) created a survey instrument to measure transactional distance in a higher education setting. A survey was sent to 235 students enrolled in a synchronous web-based graduate class in business regarding transactional distance and Collaborations (Rabinovich, 2009 ). The synchronous learning environment was described as a place where “live on-campus classes are conveyed simultaneously to both in-class students on campus and remote students on the Web who join via virtual classroom Web collaboration software” (Rabinovich, 2009 ). The virtual classroom software is similar to the characteristics of the two different software described by (Falloon, 2011 ; Mathieson, 2012 ) that it allows for students to interact with the educator and fellow students in real-time (Rabinovich, 2009 ). Moreover, (Kassandrinou, Angelaki, & Mavroidis, 2014 ) reported that the instructor plays a crucial role as interaction and communication helpers, as they are tasked with fostering, reassuring and assisting communication and interaction among students. Face-to-face tutorials have proven to be a vast opportunity for a multitude of students to interchange ideas, argue the content of the course and its related concerns (Vasala & Andreadou, 2010 ).

Students’ interactions with the instructor in online platforms

Purposeful interaction or (dialogue) in the current study describes communication that is learner-learner and learner-instructor which is designed to improve the understanding of the student. According to (Shearer, 2010 ) communication should also be constructive in that it builds upon ideas and work from others, as well as assists others in learning. (Moore, 1972 ) affirmed that learners also must realize that, and value the importance of the learning interactions as a vital part of the learning process. In a manner similar to (Benson & Samarawickrema, 2009 ] study of teacher preparatory students, (Falloon, 2011 ) investigated the use of digital tools in a case study at a teacher education program in New Zealand. (Mathieson, 2012 ) also explored the role dialogue plays in digital learning environments. She created a digital survey that examined students’ perception of audio-visual feedback in courses that utilize screen casting digital tools. (Moore, 2007 ) discusses autonomous learners searching for courses that do not stress structure and dialogue in order explain and enhance their learning progression. (Abuhassna et al., 2020 ; Abuhassna & Yahaya, 2018 ; Al-Rahmi et al., 2015b ; Al-Rahmi, Othman, & Yusuf, 2015d ; Furnborough, 2012 ) concluded that the feeling of cooperation that learners’ share with their fellow students effect their reaction concerning their collaboration with their peers.

Student autonomy in online platforms

Student autonomy in the current study refers to their independence and motivation towards learning. The learner is the motivation of the way toward learning, along with their expectations and requirements, thinking about everyone as a unique individual and hence investigating their own capacities and possibilities. Thus, extraordinary importance is attributed to autonomy in DL environments, since the option of instructive intercession offered in distance education empowers students towards learning autonomy (Massimo, 2014 ). In this respect, the connection between autonomy of student and explicit parts of the learning procedure are in the center of consideration as mentioned. (Madjar, Nave, & Hen, 2013 ) concluded that a learners’ autonomy-supportive environment provides these learners with adoption of a more aims guided learning, leading to more learning achievements. This is why autonomy is desired in the online settings for both individual development and greater achievement in academic environments. The researchers also indicate in their research that while autonomy supports outcomes in goals and aims guiding, educator practices mainly lead to goals which necessary cannot adapt. Thus, supportive-autonomy learning process needs to be designed with affective elements consideration as well. However, (Stroet, Opdenakker, & Minnaert, 2013 ) efficiently surveyed 71 experimental studies on the impacts of autonomy supportive teaching on motivation of learner and discovered a clear positive correlation. Similar to attribution theory, the relationship between learner control and inspiration involves the possibility of learners adjusting their own inspirations, for example, learners may be competent to change self-determined extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivation. However, (Jacobs, Renandya, & Power, 2016 ) further indicated that learners will not reach the same level of autonomy without reviewing learner’s autonomy insights, reflecting on their learning experiences, sharing these experiences and reflections with other learners, and realizing the elements influencing all these processes, and the process of learning as well.

Student satisfaction in online platforms

Student satisfaction in the current study refers to the fact that there are many factors that play a role in determining the learner’s satisfaction, such as faculty, institution, individual learner element, interaction/communication elements, the course elements, and learning environment. Discussion of the elements also related to the role of the instructor, with the learner’s attitude, social presence, usefulness, and effectiveness of Online Platforms. (Yu, 2015 ) investigated that student satisfaction was positively associated with interaction, self-efficacy and self-regulation without significant gender variations. (Choy & Quek, 2016 ). examined the relationships between the learners’ perceived teaching, social, and cognitive element. In addition, satisfaction, academic performance, and achievement can be measured using a revised form of the survey instrument. (Kirmizi, 2014 ) studied connection between 6 psychosocial scales: personal relevance, educator assistance, student interaction and collaboration, student autonomy, authentic learning, along with active learning. A moderate level of correlation was found between these mentioned variables. Learner satisfaction predictors were educator support, personal relevance and authentic learning, while authentic learning was the only academic success predictor. Findings of (Bordelon, 2013 ) determined and described a positive correlation between both achievement and satisfaction. He demonstrated that the reasons behind these conclusions could be cultural variations in learner’s satisfaction which point out learning accession Zhu ( 2012 ). Scholars in the field of student satisfaction emphasis on the delivery besides the operational side of the student’s experience in the teaching process (Al-Rahmi, Othman, & Yusuf, 2015e ).

Students’ academic achievements in online platforms

Students achievements in this study refers to Bloom’s main four components of achievements, which are remembering, understanding, applying, and analyzing. Finding in a study conducted by (Whitmer, 2013 ) revealed the relationships between student academic achievement and the LMS usage, thus the findings showed a highly systematic association ( p < .0000) in relation to every variable. These variables described 12% and 23% of variations within the final course marks, which indicates that learners who employed the LMS more often obtained higher marks than the others. Thus, the correlation techniques examined these variables separately to ascertain their association with the final mark. Moreover, it is not the technology itself; it is the educational methods in relation to which technology has been utilized that create a change in learners’ achievement. Instruments used are significant in identifying the technology impact, moreover, it is the implementation of those instruments under specific activities and for certain purposes which indicates whether or not they are effective. In contrast, a study conducted by (Barkand, 2017 ) revealed that LMS tools were not considered to have an effect on semester final grades when categorized by school year. In his study, semester final grades were a measure of student achievement, which has subjective elements. To account for the subjective elements in semester final grades, the study also included objective post test scores to evaluate student learning. Additionally, in this study, we refer to Bloom’s Taxonomy established in 1956 under the direction of educational psychologist for measuring students’ academic achievement (Bloom et al., 1956 ). Moreover, in this study, we selected fours domains of Blooms Taxonomy in order to achieve this study objectives, which are; application: which refers to using a concept in new context, for instance; applying what has been learned inside the classroom into different circumstances; remembering, which refers to recalling or retrieving prior learned knowledge; understanding, which refers to realizing the meaning, then clarification of problems instructions; analyzing, which refers to separating concepts or material into parts in such a way that its structure can be distinguished, understood among inferences and facts.

Students’ application

Applying involves “carrying out or using a procedure through executing or implementing” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001 ). Applying in this study refers to the student’s ability to use online platforms, such as how to log in, how to end session, how to download materials, how to access links and videos. Students can exchange information about a specific topic in online platforms such as Moodle, Google Documents, Wikis and apply knowledge to create and participate in online platforms.

Students’ remembering

Remembering is defined as “retrieving, recognizing, and recalling relevant knowledge from long-term memory” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001 ). In this study, remembering is referred to the ability to organize and remember online resources to easily find information on the internet. Moreover, students can easily cooperate with their colleagues and educator, contributing to the educational process and justifying their study procedure. Anderson and Krathwohl ( 2001 ) In their review of Bloom’s taxonomy, Anderson and Krathwohl ( 2001 ) recognized greater learning levels as creating, evaluating, and analyzing, with the lower learning levels as applying, understanding, and remembering.

Students’ understanding

Understanding involves “constructing meaning from oral, written, and graphic messages through interpreting, exemplifying, classifying, summarizing, inferring, comparing, and explaining” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001 ). In this study, understanding is referred to as understanding regarding a subject then putting forward new suggestions about online settings, for instance; understanding how e-learning works, or LMS. For example, students use online platforms to review concepts, courses, and prominent resources are being used inside the classroom environment.

Students’ analyzing

Analyzing includes “breaking material into constituent parts, determining how the parts relate to one another and to an overall structure or purpose through differentiating, organizing, and attributing” (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001 ). Analyzing refers to the student’s ability to connect, discuss, mark-up, then evaluate the information received into one certain workplace or playground. Solomon and Schrum ( 2010 ) claim that educators have started employing online platforms for a range of activities, since they have become more familiar and there are ways for learners to benefit from using them. Generally, the purpose and goal are to publicize the development types, innovation, as well as additional activities that their learners usually do independently. Such instruments have also provided instructors ways to encourage and promote genuine cooperation in their project’s development (Solomon & Schrum, 2010 ).

Research methodology

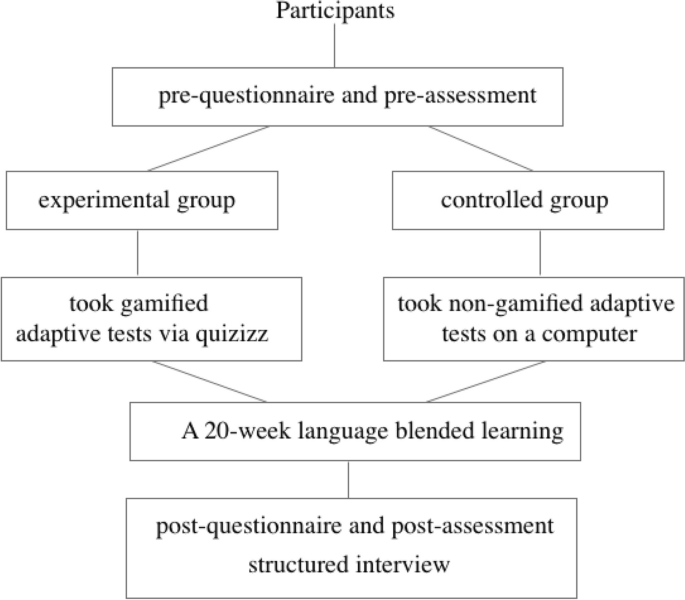

A quantitative approach was implemented in this study to provide an inclusive insight in relation to students online learning experience and how to enhance both their satisfaction and academic achievements using a questionnaire. Two experts were referred for the evaluation of the questionnaire’s content. Before the collection of the data, permission regarding the current research purpose has been obtained from Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM). In relation to the sampling and population, this research was conducted among undergraduate learners who have been online learning users. Learners, who had manually obtained the questionnaires, have been requested to fill in their details, then fill their own assessments regarding online learning platforms and its effects towards their academic achievements. Thus, for data analysis, the data that were attained from questionnaires were then analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Specifically, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM- Amos), which has been employed as a primary data analysis tool. Moreover, utilizing SEM-Amos process involves two main phases: evaluating construct validity, the convergent validity, along with the discriminant validity of the measurements; then analyzing the structural model. These mentioned two phases followed the recommendations of (Bagozzi, Yi, & Nassen, 1998; Hair, Sarstedt, Ringle, & Mena, 2012a , 2012b ).

Sample characteristics and data collection

A total of 283 questionnaires were distributed manually; of these, only 264, which make up 93.3% of the total number, were returned to the authors. Excluding the 26 incomplete questionnaires, 264 were evaluated employing SPSS. A total of 21 questionnaires have been excluded: 14 were incomplete and 7 having outliners. Thus, the overall number of valid questionnaires was 243 following this exclusion. This exclusion step is being supported by Hair et al. ( 2012a , 2012b ) . Moreover, Venkatesh, Thong, & Xu, 2012 who pointed out that this procedure is essential to be implemented as the existence of outliers could be a reason for inaccurate results. Regarding the respondent’s demographic details: 91 (37.4%) were males, and 152 (62.6%) were females. 149 (61.3%) were in the age range of 18 t0 20 years old, 77 (31.7%) were in the age range of 21 to 24 years old, and 17 (7.0%) were in the age range of 25 to 29 years old. Regarding level of study: 63 (25.9%) were from level 1, 72 (29.6%) were from level 2, 50 (20.6%) were from level 3, and 58 (23.9%) were from level 4.

Measurement instruments

The questionnaire in this study has been developed to fit the study hypothesis. Consequently, it was developed based into both theories that have been utilized in this study. The questionnaire has two main sections, first section aims to measure student satisfaction which is based on the TDT theory variables. Second section of the questionnaire has been developed to measure students’ academic achievement based on Bloom theory. According to Bloom theory there are four variables that measure students’ achievements, which are application, remembering, understanding, analyzing. On that basis the questionnaire has been developed to measure both students’ satisfaction and academic achievements . The construct items were adapted to ensure content validity. This questionnaire consisted of two main sections. First part covered the demographic details of the respondents’ including age, gender, educational level. The second part comprises 51 items which were adapted from previous researches as following; student background, five items, student experience, five items adapted from (Akaslan & Law, 2011 ), student collaborations, and, student interactions items adapted from (Bolliger & Inan, 2012 ), student autonomy, five items adapted from (Barnard et al., 2009 ; Pintrich, Smith, Garcia, & McKeachie, 1991 ), student satisfaction, six items adapted from (The blended learning impact evaluation at UCF is conducted by Research Initiative for Teaching Effectiveness, n.d. ). Moreover, effects of the students’ application, four items, students’ remembering, four items, students’ understanding, four items, students’ analyzing, four items, and students’ academic achievements, four items adapted from (Pekrun, Goetz, & Perry, 2005 ). The questionnaire has been distributed to the students after taking the online course.

Result and analysis

Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient result was 0.917 among all research model factors. Thus, the discriminant validity (DV) assessment was carried out through utilizing three criteria, which are: index between variables, which is expected to be less than 0.80 (Bagozzi, Yi, & Nassen, 1988 ); each construct AVE value must be equal to or higher than 0.50; square of (AVE) between every construct should be higher, in value, than the inter construct correlations (IC) associated with the factor [49]. Furthermore, the crematory factor analysis (CFA) findings along with factor loading (FL) should therefore be 0.70 or above although the Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) results are confirmed to be ≥0.70 [50]. Researchers have also added that composite reliability (CR) is supposed to be ≥0.70.

Model analysis

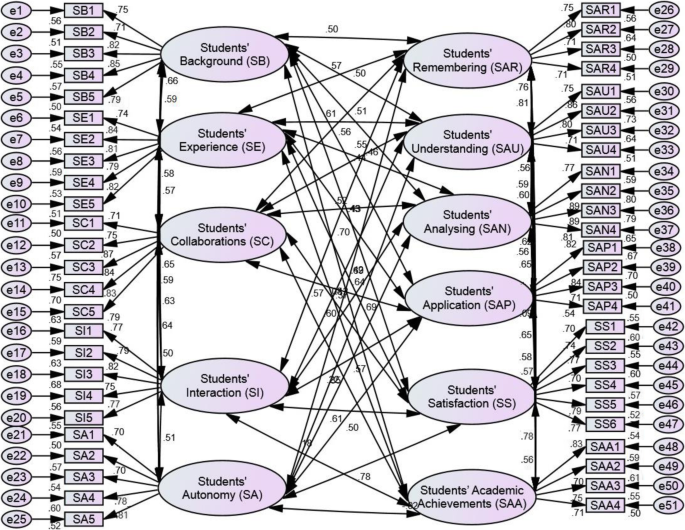

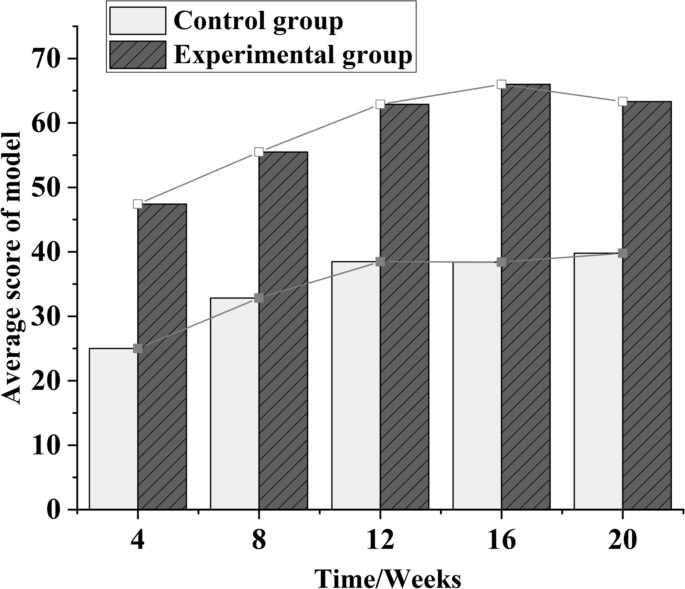

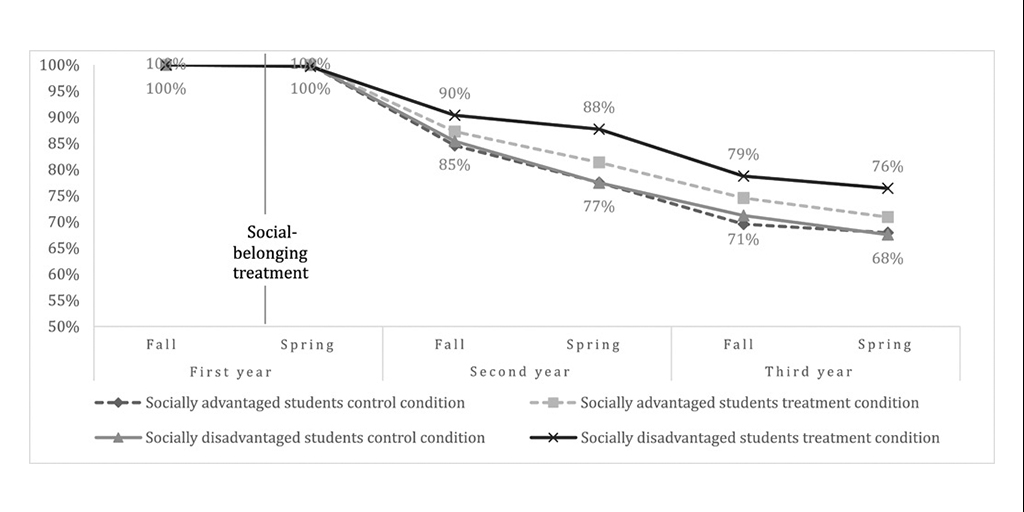

Current research employed AMOS 23 to analyze the data. Both structural equation modeling (SEM) as well as confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) have been employed as the main analysis tools. Uni-dimensionality, reliability, convergent validity along with discriminant validity have been employed to assess the measurement model. (Bagozzi et al., 1988 ; Byrne, 2010 ; Kline, 2011 ) highlighted that goodness-of-fit guidelines, such as the normed chi-square, chi-square/degree of freedom, normed fit index (NFI), relative fit index (RFI), Tucker-Lewis coefficient (TLI) comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), the parsimonious goodness of fit index (PGFI), thus, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) besides the root mean-square residual (RMR). All these are tools which could be utilized as the assessment procedures for the model estimation. See Table 1 & Fig. 2 .

Measurement Model

Measurement model

Such type of validity is commonly employed to specify the size difference between a concept and its indicators and other concepts (Hair et al., 2012a , 2012b ). Through analysis in this context, discriminant validity has proven to be positive over all concepts given that values have been over 0.50 (cut-off value) from p = 0.001 according to Fornell and Larcker ( 1981 ). In line with Hair et al. ( 2012a , 2012b ) . Bagozzi, Yi, & Nassen, (1998), the correlation between items at any two specified constructs must not exceed the square root of the average variance that is shared between them in a single construct. The outcomes values of composite reliability (CR) besides those of Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) remained about 0.70 and over, while the outcomes of the average variance extracted (AVE) remained about 0.50 and higher, indicating that all factor loadings (FL) were significant, thereby fulfilling conventions in the current assessment Bagozzi, Yi, & Nassen, (1998), and Byrne ( 2010 ). Following sections expand on the results of the measurement model. Findings of validity, reliability, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR) as well as Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) have all been accepted, which also demonstrated determining the discriminant validity. It is determined that all the values of (CR) vary between 0.812 and 0.917, meaning they are above the cut-off value of 0.70. The (CA) result values also varied between 0.839 and 0.897 exceeding the cut-off value of 0.70. Thus, the (AVE) was similarly higher than 0.50, varying between 0.610 and 0.684. All these findings are positive, thus indicating significant (FLs) and they comply with the conventional assessment guidelines Bagozzi, Yi, & Nassen, (1998), along with Fornell and Larcker ( 1981 ). See Table 2 and Additional file 1 .

Structural model analysis

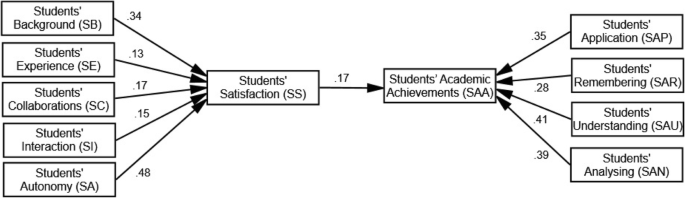

In the current study, the path modeling analysis has been utilized to examine the impact of students’ academic achievements among higher education institutions through the following factors (students’ background, students’ experience, students’ collaborations, students’ interaction, students’ autonomy, students’ remembering, students’ understanding, students’ analyzing, students’ application, students’ satisfaction), which is based on online learning. The findings are displayed then compared in hypothesis testing discussion. Subsequently, as the second stage, factor analysis (CFA) has being conducted on structural equation modeling (SEM) in order to assess the proposed hypotheses as demonstrated in Fig. 3 .

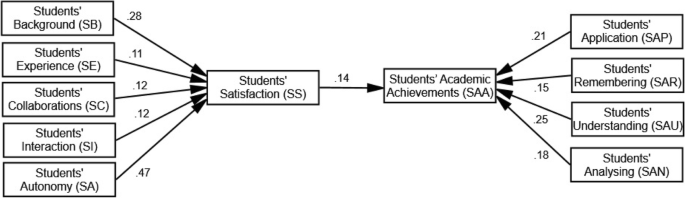

Findings for the Proposed Model Path analysis

As shown in both Figs. 3 and 4 , all hypotheses have been accepted. Moreover, Table 3 below shows that the fundamental statistics of the model was good, which indicates model validity along with the testing results of the hypotheses through demonstrating the values of unstandardized coefficients besides standard errors of the structural model.

Findings for the Proposed Model T.Values

The first direct five assumptions, students’ background, students’ experience, students’ collaborations, students’ interaction; students’ autonomy with students’ satisfaction, were addressed. In accordance with Fig. 4 and Table 3 , relations between students’ background and students’ satisfaction was (β = .281, t = 5.591, p < 0.001), demonstrating that the first hypothesis (H1) has suggested a positive and significant relationship. Following hypothesis illustrated the relationship between students’ experience and students’ satisfaction (β = .111, t = 1.951, p < 0.001), demonstrating that the second hypothesis (H2) proposed a positive and significant relationship. Third hypothesis illustrated the relationship between students’ collaborations and students’ satisfaction (β = .123, t = 2.584, p < 0.001) demonstrating that the third hypothesis (H3) has suggested a positive and significant relationship. Additionally, the relationship between students’ background and students’ satisfaction was (β = .116, t = 2.212, p < 0.001), indicating that the fourth hypothesis (H4) has suggested a positive and significant relationship. Further to the above-mentioned findings, the relationship between students’ autonomy and students’ satisfaction was (β = .470, t = 7.711, p < 0.001), demonstrating that the fifth hypothesis (H5) has suggested a positive and significant relationship. Moreover, in the second section, five assumptions were discussed, which are students’ satisfaction, students’ remembering, students’ understanding, students’ analyzing, students’ application along with students’ academic achievements.

As shown in Fig. 4 and Table 3 , the association between students’ satisfaction and students’ academic achievements was (β = .135, t = 3.473, p < 0.001), demonstrating that the sixth hypothesis (H6) has suggested a positive and significant relationship. Following hypothesis indicated the relationship between students’ application and students’ academic achievements (β = .215, t = 6.361, p < 0.001), indicating that the seventh hypothesis (H7) has suggested a positive and significant relationship. Thus, the eighth hypothesis indicated the relationship between students’ remembering and students’ academic achievements was (β = .154, t = 4.228, p < 0.001), demonstrating that the eight hypothesis (H8) has suggested a positive and significant relationship. Additionally, the correlation between students’ understanding and students’ academic achievements was (β = .252, t = 6.513, p < 0.001), demonstrating that the ninth hypothesis (H9) has suggested a positive and significant relationship. Finally, the relationship between students’ analyzing and students’ academic achievements was (β = .179, t = 6.215, p < 0.001), demonstrating that the tenth hypothesis (H10) has suggested a positive and significant relationship. Accordingly, this current model demonstrated student’s compatibility to use online learning platforms to improve students’ academic achievements and satisfaction. This is in accordance with earlier investigations (Abuhassna & Yahaya, 2018 ; Al-Rahmi et al., 2018 ; Al-rahmi, Othman, & Yusuf, 2015c ; Barkand, 2017 ; Madjar et al., 2013 ; Salmon, 2014 ).

Discussion and implications

Developing a new hybrid technology acceptance model through combining TDT and BTT has been the major objective of the current research, which aimed to investigate the guiding factors towards utilizing online learning platforms to improve students’ academic achievements and satisfaction in higher education institutions. The current research is intensifying a step forward by implementing TDT along with a BTT model. Using the proposed model, the current research examined how students’ background, students’ experience, students’ collaborations, students’ interactions, and students’ autonomy positively affected students’ satisfaction. Moreover, effects of the students’ application, students’ remembering, students’ understanding, students’ analyzing, and students’ satisfaction positively affected students’ academic achievements. The current research found that students’ background, students’ experience, students’ collaborations, students’ interactions, and students’ autonomy were influenced by students’ satisfaction. Also, effects of the students’ application, students’ remembering, students’ understanding, students’ analyzing, and students’ satisfaction positively affected students’ academic achievements. This conclusion is consistent with earlier correlated literature. Thus, this reveals that learners first make sure whether using platforms of online learning were able to meet their study requirements, or that using platforms of online learning are relevant to their study process before considering employing such technology in their study. Learners have been noted to perceive that platforms of online learning is more useful only once they discover that such a technology is actually better than the traditional learning which does not include online learning platforms (Choy & Quek, 2016 ; Illinois Online Network, 2003 ). Using the proposed model, the current research examined how to improve students’ academic achievements and satisfaction. Thus, the following section will be a comparison between this study results and previous research, as follows.

The first hypotheses of this study demonstrated a positive and significant association between students’ prior background towards online platforms with their satisfaction. As clearly investigated in Osika and Sharp ( 2002 ) study, numerous learners deprived of these main skills enroll in the courses, struggle, and subsequently drop out. In addition, Bocchi, Eastman, and Swift ( 2004 ) investigation claimed that prior knowledge of students’ concerns, demands along with their anticipations is crucial in constructing an efficient instruction. Thus, to clarify, students must have prior knowledge and background before letting them into the online platforms. On the other hand, there are constant concerns about the online learning platforms quality in comparison to a face-to-face learning environment, as students do not have the essential skills required toward using online learning platforms (Illinois Online Network, 2003 ). Moreover, a study by Alalwan et al. ( 2019 ) discovered that Austrian learners still would rather choose face-to-face learning for communication purposes, and the preservation of interpersonal relations. This is due to the fact that learners do not as yet have the background knowledge and skills needed towards using online learning platforms. Additional research by Orton-Johnson ( 2009 ) among UK learners claimed that learners have not accepted online materials, and continue to prefer traditional context materials as the medium for their learning, which also indicates the importance of prior knowledge and background towards online platforms before going through such a technology.

The second hypotheses of this study proposed a positive and significant association between students’ experience along with students’ satisfaction, which revealed that putting the students in such an experience would provide and support them with the ability to overcome all difficulties that arise through the limits around the technical ability of the online platforms. This is in line with some earlier researches regarding the reasons that lead to people’s technology acceptance behavior. One reason is the notion of “conformity,” which means the degree to which an individual take into consideration that an innovation is consistent with their existing demands, experiences, values and practices (Chau & Hu, 2002 ; Moore & Benbasat, 1991 ; Rogers, 2003 ; Taylor & Todd, 1995 ). Moreover, (Anderson & Reed, 1998 ; Galvin, 2003 ; Lewis, 2004 ) claimed that most students who had prior experience with online education tended to exhibit positive attitudes toward online education, and it affects their attitudes toward online learning platforms.

The third hypotheses of this study demonstrated a positive and significant association among student collaboration with themselves in online platforms, which indicates the key role of collaboration between students in order to make the experiment more realistic and increase their ability to feel more involved and active. This is agreement with Al-rahmi, Othman, and Yusuf ( 2015f ) who claimed that type, quality, and amount of feedback that each student received was correlated to a student’s sense of success or course satisfaction. Moreover, Rabinovich ( 2009 ) found that all types of dialogue were important to transactional distance, which make it easier for the student to adapt to online learning platform. Also, online learning platforms enable learners to share then exchange information among their colleagues Abuhassna et al., 2020 ; Abuhassna & Yahaya, 2018 ).

Students’ interaction with the instructor in online platforms

The fourth hypothesis of this study proposed a positive and significant correlation between students’ collaborations and students’ satisfaction, which indicates the significance of the communication between students and their instructor throughout the online platforms experiment. These results agree with (Mathieson, 2012 ) results, which stated that the ability of communication between students and their instructor lowered the sense of separation between learner and educator. Moreover, in line with (Kassandrinou et al., 2014 ), communication guides learners to undergo constructive emotions, for example relief, satisfaction and excitement, which assist them to achieve their educational goals. In addition, (Furnborough, 2012 ) draws conclusion that learners’ feeling of cooperating with their fellow students effects their reaction concerning their collaboration with their peers. Moreover, Kassandrinou et al., 2014 focused on the instructor as crucial part as interaction and communication helpers, as they are thought to constantly foster, reassure and assist communication and interaction amongst students.

Student’s autonomy in online platforms

The fifth hypotheses of this study proposed a positive and significant relationship between student’s autonomy and online learning platforms, which indicates that students need a sense of dependence towards online platforms, which agrees with Madjar et al. ( 2013 ) who concluded that a learners’ autonomy-supportive environment provides these learners with adoption of more aims, leading to more learning achievements. Moreover, Stroet et al. ( 2013 ) found a clear positive correlation on the impacts of autonomy supportive teaching on motivation of learner. O’Donnell, Chang, and Miller ( 2013 ) also argues that autonomy is the ability of the learners to govern themselves, especially in the process of making decisions and setting their own course and taking responsibility for their own actions.

Student’s satisfaction in online platforms

The sixth hypotheses of this study proposed a positive and significant correlation between student’s satisfaction with online learning platforms, which indicates a level of acceptance by the students to adapt into online learning platforms. This is in agreement with Zhu ( 2012 ) who reported that student’s satisfaction in online platforms is a statement of confidence with the system. Moreover, Kirmizi ( 2014 ) study revealed that the predictors of the learners’ satisfaction were educator’s support, personal relevance and authentic learning, whereas the authentic learning is only the predictor of academic success. Furthermore, the findings of Bordelon ( 2013 ) stated and determined a positive correlation between both satisfaction and achievement. In addition, the results of Mahle ( 2011 ) clarified that student satisfaction occurs when it is realized that the accomplishment has met the learners’ expectations, which is then considered a short-term attitude toward the learning procedure.

Hypotheses seven, eight, nine and ten of this study proposed a positive and significant relationship between student’s academic achievements with online learning platforms, which indicates the key main role of online platform with students’ academic achievements. This agrees with Whitmer ( 2013 ) findings, which revealed that the associations between student usage of the LMS and academic achievement exposed a highly systematic relationship. In contrast, Barkand ( 2017 ) found that there is no significant difference in students’ academic achievements in utilizing online platforms regarding students’ academic achievements, which is due to the fact that academic achievement towards online learning platforms requires a certain set of skills and knowledge as mentioned in the above sections in order to make such technology a success.

The seventh hypotheses of this study proposed a positive and significant correlation between students’ application and students’ academic achievements, which indicates the major key of applying in the learning process as an effected element. This is in line with the Computer Science Teachers’ Association (CSTA) taskforce in the U. S (Computer Science Teachers’ Association (CSTA), 2011 ), where they mentioned that applying elements of computer skills is essential in all state curricula, directing to their value for improving pupils’ higher order thinking in addition to general problem-solving abilities. Moreover, Gouws, Bradshaw, and Wentworth ( 2013 ) created a theoretical framework which drawn education computational thoughts compared to cognitive levels established from Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning Purposes. Four thinking skill levels have been utilized to assess the ‘cognitive demands’ initiated by computational concepts for instance abstraction, modelling, developing algorithms, generating automated processes. Through the iPad app, LightBot. thinking skills remained recognizing (which means recognize and recall expertise correlating to the problem); Understanding (interpret, compare besides explain the problem); whereas, applying (make use of computer skills to create a solution) then Assimilating (critically decompose and analyses the problem).

The eighth hypotheses of this study proposed a positive and significant correlation between students’ remembering and students’ academic achievements, which indicates the importance of remembering as a process of retrieving information relating to what needed to be done and/or outcome attributes) over the procedure of learning according to Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Additionally, Falloon ( 2016 ) claimed that responding to data indicated the use of general thinking skills to clarify and understand steps and stages needed to complete a task (average 29%); recalling or remembering information about a task or available tools (average 13%); and discussing and understanding success criteria (average 3%).

The ninth hypotheses of this study proposed a positive and significant correlation between students’ understanding and students’ academic achievements, which indicates its significance with the academic achievements as a process of criticizing the task or the problem faced by the students into phases or activities to help understanding of how to resolve the problem. The current results agree with Falloon ( 2016 ) who demonstrated the necessity to build understanding over the thinking processes employed by students once they are engaged in their work. In addition, Falloon ( 2016 ) suggested that the purpose and nature of questioning was broader than this, with questioning of self and others being an important strategy in solution development. In many respects, the questioning for those students was not much a perspective, although more a practice, to the degree that assisted them to understand their tasks, analyze intended or developed explanations and to evaluate their outcomes.

The tenth hypotheses of this study proposed a positive and significant correlation between students’ understanding and students’ academic achievements, which reveals the importance of analysis as a process of employing general thinking besides computational knowledge in order to realize the challenges through using online platforms, in addition to predictive thinking to categorize, explore and fix any possible errors throughout the whole process. Falloon ( 2016 ) claimed that analyzing was often a collaborative procedure between pairs receiving and giving counseling from others to assist in solving complications. On the other hand, online learning platforms are highly dependent on connecting and sharing as a basic strategy that needs to be employed over all stages of online learning settings, whether between students and students, or between students and their instructor. Moreover, Falloon ( 2016 ) findings showed that Analyzing (average 17%) was present in various phases of these online students’ work, which is based on what phase they were at together with their tasks, despite the fact that most analysis was associated with students depending on themselves during online process.

Conclusion and future work

In this investigation, both transactional distance theory (TDT) and Bloom’s Taxonomy theory (BTT) have been validated in the educational context, providing further understanding towards the students’ prospective perceptions on using online learning platforms to improve students’ academic achievement and satisfaction. The contribution that the current research might have to the field of online learning platforms have been discussed and explained. Additional insights towards students’ satisfactions and students’ academic achievements have also been presented. The current research emphasizes that the incorporation of both TDT and BTT can positively influence the research outcome. The current research has determined that numerous stakeholders, for instance developers, system designers, along with institutional users of online learning platforms reasonably consider student demands and needs, then ensure that the such a system is effectively meeting their requirements and needs. Adoption among users of online learning platforms could be broadly clarified by the eleven factor features which is based on this research model. Thus, the current research suggests more investigation be carried out to examine relationships among the complexity of online learning platforms combined with technology acceptance model (TAM).

Recommendations for stakeholders of online platforms

Based on the study findings, the first recommendation would be for administrators of higher institution. In order to implement online learning, there must be more interest given to the course structure design, whereas it should be based on theories and prior literature. Moreover, instructor and course developer need to be trained and skilled to achieve online learning platforms goals. Workshops and training sessions must be given for both instructors and students to make them more familiar in order to take the most advantages of the learning management system like Moodle and LMS. The software itself is not enough for creating an online learning environment that is suitable for students and instructors. If instructors were not trained and unaware of utilizing the software (e.g. Moodle) in the class, then the quality of education imparted to students will be jeopardized. Training and assessing the class instructor and making modifications to the software could result in a good environment for the instructor and a quality education for the student. Both students’ satisfaction and academic achievements depends on their prior knowledge and experience in relation to online learning. This current research intended to investigate student satisfaction and academic achievements in relation to online learning platforms in on of the higher education in Malaysia. Future research could integrate more in relation to blended learning settings.

Availability of data and materials

All the hardcopy questionnaires, data and statistical analysis are available.

Abuhassna, H., Megat, A., Yahaya, N., Azlina, M., & Al-rahmi, W. M. (2020). Examining Students' satisfaction and learning autonomy through web-based courses. International Journal of Advanced Trends in Computer Science and Engineering , 1 (9), 356–370. https://doi.org/10.30534/ijatcse/2020/53912020 .

Article Google Scholar

Abuhassna, H., & Yahaya, N. (2018). Students’ utilization of distance learning through an interventional online module based on Moore transactional distance theory. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education , 14 (7), 3043–3052. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/91606 .

Akaslan, D., & Law, E. L.-C. (2011). Measuring student E-learning readiness: A case about the subject of Electricity in Higher Education Institutions in Turkey. In H. Leung, E. Popescu, Y. Cao, R. W. H. Lau, & W. Nejdl (Eds.), ICWL 2011. LNCS, vol. 7048 , (pp. 209–218). Heidelberg: Springer.

Google Scholar

Alalwan, N., Al-Rahmi, W. M., Alfarraj, O., Alzahrani, A., Yahaya, N., & Al-Rahmi, A. M. (2019). Integrated three theories to develop a model of factors affecting students’ academic performance in higher education. IEEE Access , 7 , 98725–98742.

Alexander, S., & Golja, T. (2007). Using students' experiences to derive quality in an e-learning system: An institution's perspective. Educational Technology & Society , 10 (2), 17–33.

Allen, I. E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R., & Straut, T. T. (2016). Online report card: Tracking online education in the United States. Babson survey research group and the online learning consortium (OLC), Pearson, and WCET state authorization Network .

Al-Rahmi, W., Othman, M. S., & Yusuf, L. M. (2015b). The role of social media for collaborative learning to improve academic performance of students and researchers in Malaysian higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning , 16 (4). http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/2326 . https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v16i4.2326 .

Al-Rahmi, W. M., Alias, N., Othman, M. S., Alzahrani, A. I., Alfarraj, O., Saged, A. A., & Rahman, N. S. A. (2018). Use of e-learning by university students in Malaysian higher educational institutions: A case in Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. IEEE Access , 6 , 14268–14276.

Al-Rahmi, W. M., Othman, M. S., & Yusuf, L. M. (2015a). The effectiveness of using e-learning in Malaysian higher education: A case study Universiti Teknologi Malaysia. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences , 6 (5), 625–625.

Al-rahmi, W. M., Othman, M. S., & Yusuf, L. M. (2015c). Using social media for research: The role of interactivity, collaborative learning, and engagement on the performance of students in Malaysian post-secondary institutes. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences , 6 (5), 536.

Al-Rahmi, W. M., Othman, M. S., & Yusuf, L. M. (2015d). Exploring the factors that affect student satisfaction through using e-learning in Malaysian higher education institutions. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences , 6 (4), 299.

Al-Rahmi, W. M., Othman, M. S., & Yusuf, L. M. (2015e). Effect of engagement and collaborative learning on satisfaction through the use of social media on Malaysian higher education. Res. J. Appl. Sci., Eng. Technol , 9 (12), 1132–1142.

Anderson, D. K., & Reed, W. M. (1998). The effects of internet instruction, prior computer experience, and learning style on teachers’ internet attitudes and knowledge. Journal of Educational Computing Research , 19 (3), 227–246. https://doi.org/10.2190/8WX1-5Q3J-P3BW-JD61 .

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives . New York: Longman.

Azhari, F. A., & Ming, L. C. (2015). Review of e-learning practice at the tertiary education level in Malaysia. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research , 49 (4), 248–257.

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Nassen, K. D. (1988). Representation of measurement error in marketing variables: Review of approaches and extension to three-facet designs. Elsevier. Journal of Econometrics , 89 (1–2), 393–421.

Barkand, J. M. (2017). Using educational data mining techniques to analyze the effect of instructors' LMS tool use frequency on student learning and achievement in online secondary courses. Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. Retrieved from https://vpn.utm.my/docview/2007550976?accountid=41678

Barnard, L., Lan, W. Y., To, Y. M, Paton, V. O., & Lai, S. L. (2009). Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. The Internet and Higher Education , 12 (1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.10.005 .

Benson, R., & Samarawickrema, G. (2009). Addressing the context of e-learning: Using transactional distance theory to inform design. Distance Education Journal , 30 (1), 5–21.

Bliuc, A. M., Goodyear, P., & Ellis, R. A. (2007). Research focus and methodological choices in studies into students' experiences of blended learning in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education , 10 , 231–244.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook I: The cognitive domain . New York: David McKay Co Inc.

Bocchi, J., Eastman, J. K., & Swift, C. O. (2004). Retaining the online learner: Profile of students in an online MBA program and implications for teaching them. Journal of Education for Business , 79 (4), 245–253.

Bolliger, D. U., & Inan, F. A. (2012). Development and validation of the online student connectedness survey (OSCS). The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning , 13 (3), 41–65. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i3.1171 .

Bordelon, K. (2013). Perceptions of achievement and satisfaction as related to interactions in online courses (PhD dissertation) . Northcentral University.

Bouhnik, D., & Carmi, G. (2013). Thinking styles in virtual learning courses , (p. 141e145). Toronto: Proceedings of the 2013 international conference on information society (i-society) Retrieved from: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/mostRecentIssue.jsp?punumber¼6619545 .

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming , (2nd ed., ). New York: Routledge.

Chau, P. Y. K., & Hu, P. J. (2002). Examining a model of information technology acceptance by individual professionals: An exploratory study. Journal of Management Information System , 18 (4), 191–229.

Choy, J. L. F., & Quek, C. L. (2016). Modelling relationships between students’ academic achievement and community of inquiry in an online learning environment for a blended course. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology , 32 (4), 106–124 https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2500 .

Coates, H., James, R., & Baldwin, G. (2005). A critical examination of the effects of learning management systems on university teaching and learning. Tertiary Education and Management , 11 , 19–36.

Computer Science Teachers’ Association (CSTA). (2011) The computational thinking leadership toolkit. [Online] Available from: http://www.csta.acm.org/Curriculum/sub/CompThinking.html [Accessed 13 Jan 2020].

Falloon, G. (2011). Exploring the virtual classroom: What students need to know (and teachers should consider). Journal of online learning and teaching. , 7 (4), 439–451.

Falloon, G. W. (2016). An analysis of young students’ thinking when completing basic coding tasks using scratch Jnr. On the iPad. Journal of Computer-Assisted Learning , 32 , 576–379.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research , 18 (1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312 .

Furnborough, C. (2012). Making the most of others: Autonomous interdependence in adult beginner distance language learners. Distance Education , 33 (1), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012.667962 .

Galvin, T. (2003). The (22nd Annual) 2003. Industry report. Training , 40 (9), 19–45.

Gouws, L., Bradshaw, K., & Wentworth, P. (2013). Computational thinking in educational activities. In J. Carter, I. Utting, & A. Clear (Eds.), The proceedings of the 18th conference on innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education , (pp. 10–15). Canterbury: ACM.

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012a). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. , 40 (3), 414–433.

Illinois Online Network. 2003. Learning styles and the online environment. Illinois Online Network and the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois, http://illinois.online.uillinois.edu/IONresources/instructionaldesign/learningstyles.html

Jacobs, G. M., Renandya, W. A., & Power, M. (2016). Learner autonomy. In G. Jacobs, W. A. Renandya, & M. Power (Eds.), Simple, powerful strategies for student centered learning . New York: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25712-9_3 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Jaques, D., & Salmon, G. (2007). Learning in groups: A handbook for face-to-face and online environments . Abingdon: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Kassandrinou, A., Angelaki, C., & Mavroidis, I. (2014). Transactional distance among Open University students. How does it affect the learning Progress? European journal of open. Distance and e-Learning , 16 (1), 78–93.

Kauffman, H. (2015). A review of predictive factors of student success in and satisfaction with online learning. Research in Learning Technology , 23 , 1e13. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v23.26507 .

Kirmizi, O. (2014). A Study on the Predictors of Success and Satisfaction in an Online Higher Education Program in Turkey. International Journal of Education , 6 , 4.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling , (3rd ed., ). New York: The Guilford Press.

MATH Google Scholar

Lau, C. Y., & Shaikh, J. M. (2012). The impacts of personal qualities on online learning readiness at Curtin Sarawak Malaysia (CSM). Educational Research and Reviews , 7 (20), 430–444.

Lee, B. C., Yoon, J. O., & Lee, I. (2009). Learners' acceptance of e-learning in South Korea: Theories and results. Computers & Education , 53 , 1320–1329.

Lester, P. M., & King, C. M. (2009). Analog vs. digital instruction and learning: Teaching within first and second life environments. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 14 , 457–483.

Lewis, N. (2004). Military student participation in distance learning . Doctorate dissertation. Johnson & Wales University. USA.

Madjar, N., Nave, A., & Hen, S. (2013). Are teachers’ psychological control, autonomy support and autonomy suppression associated with students’ goals? Educational Studies , 39 (1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2012.667871 .

Mahle, M. (2011). Effects of interaction on student achievement and motivation in distance education. Quarterly Review of Distance Education , 12 (3), 207–215, 222.

Massimo, P. (2014). Multidimensional analysis applied to the quality of the websites: Some empirical evidences from the Italian public sector. Economics and Sociology , 7 (4), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2014/7-4/9 .

Mathieson, K. (2012). Exploring student perceptions of audiovisual feedback via screen casting in online courses. American Journal of Distance Education , 26 (3), 143–156.

McAuley, A., Stewart, B., Siemens, G., & Cormier, D. (2010). The MOOC model for digital practice (created through funding received by the University of Prince Edward Island through the social sciences and humanities research Council's “knowledge synthesis Grants on the digital economy”) .

Moore, G. C., & Benbasat, I. (1991). Development of an instrument to measure the perception of adopting an information technology innovation. Information System Research , 2 (3), 192–223.

Moore, M. (1990). Background and overview of contemporary American distance education. In M. Moore (Ed.) Contemporary issues in American distance education.

Moore, M. G. (1972). Learner autonomy: The second dimension of independent learning .

Moore, M. G. (2007). Theory of transactional distance. In M. G. Moore (Ed.), Handbook of distance education . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

O’Donnell, S. L., Chang, K. B., & Miller, K. S. (2013). Relations among autonomy, attribution style, and happiness in college students. College Student Journal .

Orton-Johnson, K. (2009). ‘I’ve stuck to the path I’m afraid’: Exploring student non-use of blended learning. British Journal of Educational Technology , 40 (5), 837–847.

Osika, R. E., & Sharp, D. P. (2002). Minimum technical competencies for distance learning students. Journal of Research on Technology in Education , 34 (3), 318–325.

Paechter, M., & Maier, B. (2010). Online or face-to-face? Students’ experiences and preferences in e-learning. Internet and Higher Education , 13 (4), 292–297.

Panyajamorn, T., Suthathip, S., Kohda, Y., Chongphaisal, P., & Supnithi, T. (2018). Effectiveness of E learning design and affecting variables in Thai public schools. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction , 15 (1), 1–34.

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., & Perry, P. R. (2005). Academic Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ): User's Manual . Munich: University of Munich, Department of Psychology; University of Manitoba Retrieved February 21, 2017. Available online at: https://de.scribd.com/doc/217451779/2005-AEQ-Manual# (Accessed 17 July 2019.

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1991). A manual for the use of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ) . Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan.

Rabinovich, T. (2009). Transactional distance in a synchronous web-extended classroom learning environment . Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Massachusetts: Boston University.

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations , (5th ed., ). New York: Free Press.

Salmon, G. (2011). E-moderating: The key to teaching and learning online , (3rd ed., ). London: Routledge.

Salmon, G. (2014). Learning innovation: A framework for transformation. European Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning , 17 (1), 219–235.

Shearer, R. L. (2010). Transactional distance and dialogue: An exploratory study to refine the theoretical construct of dialogue in online learning. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A , 71 , 800.

Solomon, G., & Schrum, L. (2010). Web 2.0 how-to for educators .

Stroet, K., Opdenakker, M. C., & Minnaert, A. (2013). Effects of need supportive teaching on early adolescents’ motivation and engagement: A review of the literature. Educational Research Review , 9 , 65–87.

Taylor, S., & Todd, P. A. (1995). Assessing IT usage: The role of prior experience. MIS Quarterly , 19 (2), 561–570.

The blended learning impact evaluation at UCF is conducted by Research Initiative for Teaching Effectiveness. (n.d.) https://digitallearning.ucf.edu/learning-analytics/ . Accessed 25 Feb 2020.

Vasala, P., & Andreadou, D. (2010). Student’s support from tutors and peer students in distance learning. Perceptions of Hellenic Open University “studies in education” postgraduate program graduates. Open Education – The Journal for Open and Distance Education and Educational Technology , 6 (1–2), 123–137 (in Greek with English abstract).

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly , 36 (1), 157–178.

Whitmer J.C. (2013). Logging on to improve achievement: Evaluating the relationship between use of the learning management system, student characteristics, and academic achievement in a hybrid large enrollment undergraduate course. Doctorate dissertation, university of California. USA.

Yu, Z. (2015). Indicators of satisfaction in clickers aided EFL class. Frontiers in Psychology , 6 , 587 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00587/full .

Zhu, C. (2012). Student satisfaction, performance, and knowledge construction in online collaborative learning. Educational Technology & Society , 15 (1), 127–136.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Declarations

The study involved both undergraduate and graduate students at unviersiti teknologi Malaysia (UTM), an ethical approve was taken before collecting any data from the participants

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Social Sciences & Humanities, School of Education, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, UTM, 81310, Skudai, Johor, Malaysia

Hassan Abuhassna, Waleed Mugahed Al-Rahmi, Noraffandy Yahya, Megat Aman Zahiri Megat Zakaria & Azlina Bt. Mohd Kosnin

Faculty of Engineering, School of Civil Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, UTM, 81310, Skudai, Johor, Malaysia

Mohamad Darwish

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The corresponding author worked in writing the paper, collecting the data, the second author done all the statistical analysis. Moreover, all authors worked collaboratively to write the literature review and discussion and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hassan Abuhassna .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

This paper is an original work, as its main objective is to develop a model to enhance students’ satisfaction and academic achievement towards using online platforms. As Universiti teknologi Malaysia (UTM) implementing a fully online courses starting from the second semester of 2020.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1..

General objective of the study

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Abuhassna, H., Al-Rahmi, W.M., Yahya, N. et al. Development of a new model on utilizing online learning platforms to improve students’ academic achievements and satisfaction. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 17 , 38 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00216-z

Download citation

Received : 10 March 2020

Accepted : 19 May 2020

Published : 02 October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00216-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Online learning platforms

- Students’ achievements

- student’s satisfaction

- Transactional distance theory (TDT)

- Bloom’s taxonomy theory (BTT)

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, study of six online learning theories shows theories should be chosen to match institutional situations and learners' backgrounds.

Human Resource Management International Digest

ISSN : 0967-0734

Article publication date: 23 August 2021

Issue publication date: 8 September 2021

The authors assessed the following six popular online theories: Cognitivism, connectivism, heutagogy, social learning, transformative learning theories and Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development (ZPD). The theories were selected because of their relevance to improving online instruction.

Design/methodology/approach

To compare them, the authors reviewed literature on adult learning theories from the following databases: Academic Search Premier, ERIC and ProQuest. They chose the most relevant articles about each theory published between 2007 and 2017, summarized them and extracted relevant information.

The theories suggest various pointers to help course designers to improve online learning. Based on cognitivism, instructors can use media-based instruction designed especially for the working memory. Similarly, connectivism informs instructors to design instruction integrated with technology. Heutagogy also promotes the integration of technology with online learning and encourages self-directed learning. Meanwhile, social learning theory informs instructors to design group discussions and activities to foster collaboration. The other three theories - cognitivism, connectivism and heutagogy – promote the integration of technology.

Originality/value