Parental Care in Amphibia (With Diagram) | Vertebrates | Chordata | Zoology

In amphibians there are many devices for the protection of the eggs during the early stages of development and the youngs. In this way nature has practised economy in the number of eggs, which varies in direct proportion to the chances of destruction. Parental care is the care of the eggs or the youngs until they become able to protect themselves from the predators.

These devices fail under two heads:

(1) Protection by the parents by means of nests, nurseries, or shelters and

(2) Direct caring or nursing by parents.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The different modes of protection are given below in the three important orders of class Amphibia.

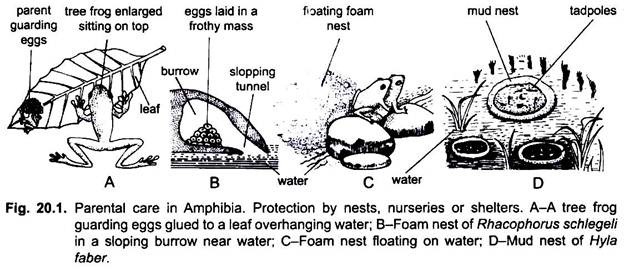

1. Protection by Means of Nests, Nurseries and Shelters:

A number of different species of frogs and toads construct nests or shelters of leaves or other materials in which the eggs are deposited and the youngs are developed.

A. In Enclosures in the Water (Mud Nests):

A large tree frog (Hyla faber) known in Brazil as the “Ferreiro”. It protects its progeny by building a basin-shaped nest or nursery in shallow water on the border of the pond. The female scoops mud to a depth of 7.5 or 10 cm and with the mud, thus, removed a circular wall is built around the nest, which emerges above the surface of the water.

The inside wall is smoothened by the flattened webbed hands and the bottom is also levelled by belly and hands. The eggs and early larvae are, thus, protected from predators (insects and fishes, etc.) until they are able to defend themselves. Heavy rains later on destroy the wall and larvae go to the water.

B. In Holes Near Water (Foam Nests):

A still better mode of protecting the offspring during the early stages of development has been adopted by a Japanese tree frog Rhacophonis schlegelii. The male and female in embrace bury themselves in the damp earth on the edge of ditch or flooded rice field, and make a hole or chamber, a few centimetres above water level. The walls of this chamber are polished and during this process the gallery by which they enter into that chamber gets obliterated and then oviposition begins.

The female first produces a secretion from cloaca which is beaten into a froth. The eggs are deposited into the froth. Now the inactive male impregnates them, and then both of them separate and make an exit gallery towards the ditch. It is obliquely downwards towards the water, later on this is used by the larvae who come to the water to complete the development.

The bubbles collapse, the froth liquefies and this liquid acts as an efficient vehicle for transporting the larvae down the tunnel into the water. Similarly female of South American tree frog, Leptodactylus mystacinus stirs up a frothy mass of mucus which is filled up in holes near water and then eggs are laid in it. The tadpoles from these nests easily enter water. Some anuran females discharge huge mucus and beat it into a foam with their hindlegs and then eggs are laid. Later on hatching tadpoles drop into water from the foam.

C. In Nests on Trees (Tree Nests):

Some tree frogs like Phyllomedusa in South America, Rhacophorus malabaricus in India, and Chiromantis in tropical Africa glues the eggs to foliage hanging over water, and after hatching, the tadpoles drop straight into the water. Hyla resinfictrix (tree frog) lines a shallow cavity of the tree by bees wax brought from the hives of stingless bees. Eggs are laid there when it is filled with rain water. Tadpoles develop here safely.

Autodax (Urodela) lay 10-20 eggs in a dry hole in ground or in a hole on a tree, up to 10 metres above the ground. Both parents remain in the hole to protect the eggs and larvae and also provide them moisture. Youngs remain within the hole for a considerable period with their parents.

D. In Transparent Gelatinuous Bags:

The eggs of Phtynixalus biroi are large which are enclosed in sausage-shaped transparent common membranous bag secreted by the female and is left in the mountain streams. The whole development takes place within the eggs and little frogs go out in perfect condition. No gills have been observed and the large tail serves as a breathing organ of young ones. Salamandrella keyserlingi (urodele) deposits its small eggs in a gelatinous bag which is attached to an aquatic plant below the water level.

E. On Trees or in Moss away from Water:

Several species of tropical American genus Hylodes lay their large eggs in damp places under stones or moss or plant leaves. The metamorphosis is hurried up within the egg. Due to plenty of yolk in the egg the entire development takes place within the egg and young frogs hop out as an air breather with a vestige of tail.

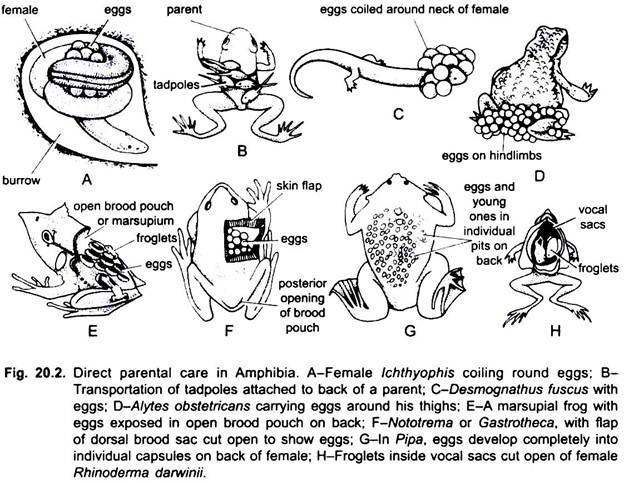

2. Direct Nursing by the Parent:

A. Tadpoles Transported from One Place to Another:

Small South American frogs Phyllobates and Dendrobates and tropical African frogs Arthroleptis and Pelobates lay their eggs on ground. The hatched tadpoles adhere by their sucker-like lips and flattened abdomen to the back of one of their parents and, thus, they are carried from one place to the other and in this way they can even go from one pool to the other and this is particularly when one pond is to dry up.

B. Eggs Protected by Male:

The eggs (17 in number) of Mantophryne robusta are strung together by an elastic gelatinous envelope forming a clump over which the male sits for development. It may be outside water .The larvae have no gills, well developed legs, large tail which is vascular and respiratory.

C. Eggs Carried by the Parents:

In Obstetric toad (Alytes obstetricans) of Europe, the male winds the strings of eggs-formed by adhesion of their gelatinuous investment-round his body and hindlegs. Here they are retained until the tadpoles are ready to be hatched.

Female Rhacophorus reticulatus (Sri Lankan tree frog) carries the eggs glued to her belly.

In Desmognathus fusca (urodele) the eggs are laid in the form of rosary-like strings. The string is bound round the body and the female nourishes them at a comparatively dry spot.

D. Eggs in Back Pouches:

(i) Exposed:

In a Brazilian tree-frog, Hyla goeldii, the female carries the eggs on the back within an incipient brood pouch in which the eggs remain exposed. How they reached there is not known but probably male does it. In Nototrema also the eggs are placed over the back in a single large brood pouch covered by the skin and opened posteriorly in front of cloacal aperture.

(ii) In Cell-Like Pouches:

In Pipa americana (Surinam toad) the eggs are carried on the back of the mother. In breeding season the back skin of female becomes thick, vascular, soft and gelatinous. The male places and spaces the eggs. Each egg sinks into a small pouch, over which develops an operculum, which comes from a remnant of the egg envelope, reinforced by integumental secretions.

Thus, the young develop moist and safe in maternal tissue. Between the invaginated pits arises a rich vascularisation. In each larva there develops a broad and vascular tail. It is suspected that metabolic exchanges take place between maternal and embryonic tissues in the manner of a primitive placenta. The larva does not develop gills, and has been reported to be born as a tadpole about eighty days after egg-deposition.

E. In the Mouth or Gular Pouch:

(i) By the Male:

In Rhinoderma darwini, small South American frog, the eggs (few and large) are transferred by the male to the relatively immense vocal sacs that extend over its ventral surface. There the eggs develop. In Arthroleptis, male frog keeps the larvae in his mouth.

(ii) By the Female:

The female of a West African tree-frog, Hylambates breviceps, carries the eggs in her mouth. Female Rheobatrachus silus (Australian frog) keeps her eggs in her stomach. The tadpoles are expelled through mouth after metamorphosis.

F. Coiling Around Eggs:

In Plethodon (urodele) the eggs are laid in small packages of about five beneath the stones or in the hollow of rotten log, and the mother coils round them. In Megalobatrachus maximus (urodele) the male coils round the eggs.

Female Amphiuma (urodele) also coils round the eggs laid in burrows in damp soil.

Coecilians Ichthyophis and Hypogeophis are oviparous, lay eggs in burrows in damp soil and coil round them until they hatch.

G. Viviparous or Viviparity:

Two small East African toads, Pseudophryne vivipara and Nectophryne tornieri, are known to be viviparous, but no observations have yet been made on them beyond the fact that larvae are found in the uteri. Caecilians like Typhlonectes, Geotrypetes, Schistometopum, Chthonerpeton, Gymnopis are ovoviviparous.

Related Articles:

- Parental Care in Fishes (With Diagram) | Vertebrates | Chordata | Zoology

- Parental Care in Fishes | Zoology

- Representative Types of Amphibia | Vertebrates | Chordata | Zoology

- Habit and Habitat of Indian Bull Frog | Vertebrates | Chordata | Zoology

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Leaping forward for reptiles and amphibians

Parental care in amphibians: research findings from 1705 to the present day

November 30, 2021 by admin

Writen by Roger Downie, University of Glasgow and Froglife

Croaking Science does not usually urge its readers to study a particular scientific paper, but this is an exception. The paper is Schulte et al. ’s (2020) review of research into amphibian parental care, a fascinating and essential read for all amphibian enthusiasts. Parental care is usually defined as ‘non-gametic investments in offspring that incur a cost to the parent’ and which provide some benefit to the offspring. Common examples are egg-guarding, and provisioning of young after hatching. Although some authors restrict discussions of parental care to actions that occur after fertilisation, others include activities like nest-building in preparation for egg laying. For example, we generally consider UK amphibians as lacking parental care: they deposit their eggs in water, then leave. But Schulte et al include the behaviour of female newts that wrap their eggs individually in leaves: this behaviour takes a substantial amount of time, so is costly to the female, and contributes to offspring survival by reducing predation.

Research into parental care tends to focus disproportionately on birds and mammals. Stahlschmidt (2011) in a review of what he termed ‘taxonomic chauvinisn’ found amphibian and reptile parental care much less studied than cases from birds, mammals and even fish. Schulte at al. redress this situation through a vast historically-based review, identifying 685 studies spanning the period 1705-2017. Early studies were mainly simply descriptive, but since 1950, there has been a greater focus on the investigation of explanations: what does parental care achieve, and what does it cost?

The paper’s Table 1 lists each of the parental care modes so far described: four in Caecilians; eight in Urodeles; 28 in Anurans. Some modes occur in all three Orders e.g. terrestrial egg guarding; others occur in only one Order e.g. wrapping of individual eggs in leaves by newts; foam-nest construction by many frogs. Overall, parental care is known from 56 (74%) of the amphibian Families. It is not really surprising that more parental care modes occur in the Anurans than in the other two Orders, since anuran species diversity is so high (Frost, 2021 lists 7406 anurans, 768 urodeles and 212 caecilians).

The first known report of parental care in an amphibian, remarkably, was by a German female natural historian and artist, Maria Sibylla Merian in 1705. Her book was mainly devoted to meticulous drawings of the insects she observed in Suriname, but she also included an illustration and observations on an aquatic frog, later named the Suriname toad ( Pipa pipa ), which incubates its eggs in individual pockets on its back: she saw the metamorphosed juveniles emerging from the pockets. I was lucky, on my first visit to Trinidad, to see this for myself. We captured a ‘pregnant’ female and the babies later hatched into the water, some still with tail stumps, others fully metamorphosed. Female biologists have been prominent in the study of amphibian parental care: in addition to Maria Sibylla Merian, Martha Crump (1996) and Bertha Lutz (1947) come to mind, as well as the four authors of the review under discussion.

Among the 500 or so papers that Schulte et al . cite, I was pleased to see two from the work we have done in Trinidad (Downie et al ., 2001; Downie et al ., 2005). These are about the Trinidad stream frog Mannophryne trinitatis (see Croaking Science September 2020), where the fathers guard the eggs on land then transport hatchlings on their backs to a pool where they can complete development to metamorphosis. Tadpole transportation is a common aspect of parental care in the neotropical families Dendrobatidae and Aromobatidae. We found that the fathers are choosy over where to deposit their tadpoles, avoiding pools that contain potential predators, and therefore contributing to their survival. The search could take up to four days. We wondered how costly this might be to fathers: to our surprise, transporting a relatively heavy load of tadpoles did not appear to reduce the fathers’ jumping ability, nor did it prevent them from finding food. However, four days away from their territory must count as at least some cost in terms of lost mating opportunities.

Schulte et al . conclude with a timely plea for a revival of teaching and research in natural history. As they say, natural history observations – on the distribution, numbers and habits of organisms- form the basis of all new ideas and hypotheses in ecology and evolutionary biology. They note that there remain many amphibian species whose habits are poorly known and that many novel observations have been made on parental care in recent years. They therefore expect that much could be discovered, as long as effort is put into new field work. Over 20 years ago, I wrote lamenting the modern status of natural history (Downie 1997, 1999), and Schulte et al. report that the loss of organism-based teaching and research is widespread. In the UK, there are moves to create a natural history curriculum, to complement biology in schools. I feel that it is much needed.

Crump (1996). Parental care among the amphibia. Advances in the Study of Behaviour 25, 109-144.

Downie (1997). Are the naturalists dying off? The Glasgow Naturalist 23 (2), 1.

Downie (1999). What is natural history, and what is its role? The Glasgow Naturalist 23 (4), 1.

Downie et al . (2001). Selection of tadpole deposition sites by male Trinidadian stream frogs ( Mannophryne trinitatis ; Dendrobatidae): an example of anti-predator behaviour. Herpetological Journal 11, 91-100.

Downie et al . (2005). Are there costs to extended larval transport in the Trinidadian stream frog ( Mannophryne trinitatis , Dendrobatidae)? Journal of Natural History 39, 2023-2034.

Frost (2021). Amphibian species of the world : an online reference. Version 6.1 (accessed 29/9/21). Electronic database accessible at http://amphibiansoftheworld.amnh.org/index.php. American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA.

Lutz (1947). Trends towards non-aquatic and direct development in frogs. Copeia 1947, 242-252.

Schulte et al . (2020). Developments in amphibian parental care research: history, present advances, and future perspectives. Herpetological Monographs 34, 71-97.

Stahlschmidt (2011). Taxonomic chauvinism revisited: insight from parental care research. PLoS ONE 6, e24192.

- Info & advice

- What’s new

- Become a Friend

- Our supporters

- Privacy Information

Froglife (Head Office) Brightfield Business Hub Bakewell Road Peterborough PE2 6XU [email protected]

Please click "Accept" to use cookies on this website. More information Accept

The cookie settings on this website are set to "allow cookies" to give you the best browsing experience possible. If you continue to use this website without changing your cookie settings or you click "Accept" below then you are consenting to this.

The evolution of parental care diversity in amphibians

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Biological and Marine Sciences, University of Hull, Cottingham Road, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK. [email protected].

- 2 Energy and Environment Institute, University of Hull, Cottingham Road, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK. [email protected].

- 3 Department of Biological and Marine Sciences, University of Hull, Cottingham Road, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK. [email protected].

- 4 Energy and Environment Institute, University of Hull, Cottingham Road, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK. [email protected].

- 5 School of Biological Sciences, Queen's University Belfast, 19 Chlorine Gardens, Belfast, BT9 5DL, UK. [email protected].

- PMID: 31624263

- PMCID: PMC6797795

- DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-12608-5

Parental care is extremely diverse across species, ranging from simple behaviours to complex adaptations, varying in duration and in which sex cares. Surprisingly, we know little about how such diversity has evolved. Here, using phylogenetic comparative methods and data for over 1300 amphibian species, we show that egg attendance, arguably one of the simplest care behaviours, is gained and lost faster than any other care form, while complex adaptations, like brooding and viviparity, are lost at very low rates, if at all. Prolonged care from the egg to later developmental stages evolves from temporally limited care, but it is as easily lost as it is gained. Finally, biparental care is evolutionarily unstable regardless of whether the parents perform complementary or similar care duties. By considering the full spectrum of parental care adaptations, our study reveals a more complex and nuanced picture of how care evolves, is maintained, or is lost.

- Adaptation, Physiological / physiology

- Amphibians / classification

- Amphibians / physiology*

- Biodiversity

- Biological Evolution*

- Maternal Behavior / physiology*

- Paternal Behavior / physiology*

- Reproduction / physiology

- Species Specificity

- Help & FAQ

The evolution of parental care diversity in amphibians

- Queen's University Belfast

- Institute for Global Food Security

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

- life history theory

- Parental care

- Phylogenetic comparative analysis

ASJC Scopus subject areas

- General Chemistry

- General Biochemistry,Genetics and Molecular Biology

- General Physics and Astronomy

Access to Document

- 10.1038/s41467-019-12608-5 Licence: CC BY

Copyright 2019 the authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited.

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Adaptation Medicine and Dentistry 100%

- Evolution Medicine and Dentistry 100%

- Parental Care Neuroscience 100%

- Species Medicine and Dentistry 66%

- Behavior (Neuroscience) Neuroscience 66%

- Behavior Psychology 66%

- Parent Medicine and Dentistry 33%

- Phylogeny Medicine and Dentistry 33%

Isabella Capellini

- School of Biological Sciences - Reader

Person: Academic

T1 - The evolution of parental care diversity in amphibians

AU - Furness, Andrew I.

AU - Capellini, Isabella

PY - 2019/10/17

Y1 - 2019/10/17

N2 - Parental care is extremely diverse across species, ranging from simple behaviours to complex adaptations, varying in duration and in which sex cares. Surprisingly, we know little about how such diversity has evolved. Here, using phylogenetic comparative methods and data for over 1300 amphibian species, we show that egg attendance, arguably one of the simplest care behaviours, is gained and lost faster than any other care form, while complex adaptations, like brooding and viviparity, are lost at very low rates, if at all. Prolonged care from the egg to later developmental stages evolves from temporally limited care, but it is as easily lost as it is gained. Finally, biparental care is evolutionarily unstable regardless of whether the parents perform complementary or similar care duties. By considering the full spectrum of parental care adaptations, our study reveals a more complex and nuanced picture of how care evolves, is maintained, or is lost.

AB - Parental care is extremely diverse across species, ranging from simple behaviours to complex adaptations, varying in duration and in which sex cares. Surprisingly, we know little about how such diversity has evolved. Here, using phylogenetic comparative methods and data for over 1300 amphibian species, we show that egg attendance, arguably one of the simplest care behaviours, is gained and lost faster than any other care form, while complex adaptations, like brooding and viviparity, are lost at very low rates, if at all. Prolonged care from the egg to later developmental stages evolves from temporally limited care, but it is as easily lost as it is gained. Finally, biparental care is evolutionarily unstable regardless of whether the parents perform complementary or similar care duties. By considering the full spectrum of parental care adaptations, our study reveals a more complex and nuanced picture of how care evolves, is maintained, or is lost.

KW - EVOLUTION

KW - life history theory

KW - Amphibians

KW - Parental care

KW - Phylogenetic comparative analysis

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85073516442&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1038/s41467-019-12608-5

DO - 10.1038/s41467-019-12608-5

M3 - Article

C2 - 31624263

AN - SCOPUS:85073516442

SN - 2041-1723

JO - Nature Communications

JF - Nature Communications

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

The evolution of parental care diversity in amphibians

- Author & abstract

- 3 Citations

- Related works & more

Corrections

(University of Hull University of Hull)

(University of Hull University of Hull Queen’s University Belfast)

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Parental care in amphibia

Amphibians are known to care a lot for their young ones as well as eggs by various techniques.

Related Papers

Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological Genetics and Physiology

Alexander Kupfer

Mauro Pastorino

Natural History

David Bickford

Scientific Reports

Balazs Vagi

Complex parenting has been proposed to contribute to the evolutionary success of vertebrates. However, the evolutionary routes to complex parenting and the role of parenting in vertebrate diversity are still contentious. Although basal vertebrates provide clues to complex reproduction, these are often understudied. Using 181 species that represent all major lineages of an early vertebrate group, the salamanders and newts (Caudata, salamanders henceforth) here we show that fertilisation mode is tied to parental care: male-only care occurs in external fertilisers, whereas female-only care exclusively occurs in internal fertilisers. Importantly, internal fertilisation opens the way to terrestrial reproduction, because fertilised females are able to deposit their eggs on land, and with maternal care provision, the eggs could potentially develop outside the aquatic environment. Taken together, our results of a semi-aquatic early vertebrate group propose that the diversity and follow-up r...

Antonio Romano

Andrew J Crawford

Amphibians and reptiles strike awe and fear in the eyes of beholders. They are both loved and, more so than any other group of vertebrates, wrongfully maligned. They are a valuable economic resource for enjoyment, food, and as the sources for traditional and many modern medicines. Reproductively, they range from egg-laying species to those that give birth to live young whose embryos are nourished via placenta. Some species of amphibians feed their neonates and crocodilians provide complex parental care. Biologically, they serve ...

Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods

Stephane Milano

Applied Mathematical Sciences

Oleksandr Karelin

Marco Bernardi

RELATED PAPERS

Nate Hilberg

Journal of Bacteriology

Christopher M Sales

American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology

Giuditta Perozzi

Ajay Jaiswal

Journal of Differential Equations

massimo cicognani

Current Allergy and Asthma Reports

Erik Florvaag

Endocrinology

Martine Cohen-solal

Universidad Nacional de Córdoba. Facultad de Filosofía y Humanidades

Roque Farrán

Asian Journal of Agriculture and Food Sciences

Cristina Bravo Rozas

rahmat saputra

JOSÉ ANGEL SÁNCHEZ AGUDO

Elena Tamburini

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology

elisabetta guerzoni

Ozgur Kemik

Pediatric Transplantation

Michael Trigg

instname:Universidad Piloto de Colombia

isabella fernanda

Genes & development

Richard Morimoto

Scandinavian Journal of Public Health

Annett Arntzen

Barbara Wolfe

Maya Archaeology: Caves and Mesoamerican Cultures

Nicholas Hellmuth

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

What Happens When Abusive Parents Keep Their Children

By Naomi Schaefer Riley

Ms. Riley is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of “No Way to Treat a Child.”

In February 2023, Phoenix Castro was born in San Jose, Calif., suffering from neonatal opioid withdrawal after being exposed to fentanyl and methamphetamine in her mother’s womb.

Her mother was sent to jail and then ended up at a drug treatment facility. But her father, who had multiple drug arrests, was allowed to take the newborn to his San Jose apartment, even though a social worker had warned that the baby would be at “very high” risk if she was sent home. The county’s child protection agency had already removed the couple’s two older children because of neglect.

Three months later, Phoenix was dead from an overdose of fentanyl and methamphetamine.

The ensuing uproar, chronicled in detail by The Mercury News, focused on new efforts by the county to keep at-risk families together. In the past, children often would be removed from unsafe homes and placed in foster care, and newborns like Phoenix in all likelihood would not have been sent home.

Those policy changes led to a “ significant ” drop in removals of children from troubled homes in the San Jose area, according to the state’s social services agency. They reflected a larger shift in child welfare thinking nationwide that has upended the foster care system. Reducing the number of children placed in foster care has been hailed as an achievement. But leaving children in families with histories of abuse and neglect to avoid the trauma of removing them has had tragic results.

We need to ask whether avoiding foster care, seemingly at all costs — especially for children in families mired in violence, addiction or mental illness — is too often compromising their safety and welfare.

The use of foster care has been in decline even as more children are dying from abuse and neglect in their homes. In recent years, the number of children in foster care fell by nearly 16 percent while the fatality rate from abuse and neglect rose by almost 18 percent. Many factors were and are at work, among them caseworker inexperience, a lack of resources and the high bars for removing children from their homes that have been erected by child welfare agencies, policymakers and judges.

What is clear from a sampling of states that release fatality reports in a timely fashion is that we are seeing deaths of children in cases in which they had been allowed to remain in homes with records of violence, drug use and neglect.

In Minnesota, a children’s advocacy group’s study of 88 child fatalities in the state from 2014 to 2022 found that “many of these deaths were preventable” and were the result of a “child welfare philosophy which gave such high priority to the interests of parents and other adults in households, as well as to the goals of family preservation and reunification, that child safety and well-being were regularly compromised.”

The prioritization of family preservation has been advanced by states and the federal government and by the nation’s largest foundation focused on reducing the need for foster care, Casey Family Programs.

Three ideas seem to have guided the effort: the child welfare system is plagued by systemic racial bias, adults should not be punished for drug addiction, and a majority of children in the system are simply in need of financial support and social services.

This effort was bolstered in 2018 with the passage by Congress of the Family First Prevention Services Act , which enables states to use federal funds “to provide enhanced support to children and families and prevent foster care placements through the provision of mental health and substance abuse prevention and treatment services” and other programs.

The push certainly has been well-intentioned. There was a sense that child welfare authorities had overreacted to concerns about a crack baby epidemic in the 1980s. Mothers were arrested and babies and children taken away. The number of children in foster care more than doubled between 1985 and 2000. There was also deep concern — concern that persists — that Black children in particular were bearing the brunt of being removed from their homes and sent to foster care, which can cause its own upheaval for children.

In some states, the reductions in the number of children in foster care were drastic. But there are limits to how much those numbers can be reduced without putting children in grave danger.

In Santa Clara County, Calif., where Phoenix Castro died, an inquiry the previous year by the California Department of Social Services into the county’s child protection agency found “multiple” instances of “children placed into protective custody by law enforcement,” only to have the county agency “immediately” place “the children back in the care of the unsafe parent.” (In what appears to be an about-face by the county, The Mercury News reported that in the last two months of 2023, the number of children removed from their homes was triple the two-month average for the previous months of that year.)

In an email to Santa Clara County’s Department of Family and Children’s Services staff in 2021, explaining the new emphasis on keeping families together, the director at the time described the move as part of the county’s strong commitment “to racial justice and to healing the historical wounds underlying disproportionate representation of children of color in the child welfare system.”

As much as racial disparities in foster care are deeply troubling — Black children are twice as likely as white children to spend time in foster care — Black children also suffer fatalities from abuse and neglect at three times the rate of white children. Which means that policies intended to reduce disproportionality by reducing foster care may actually be resulting in more deaths of Black children.

Foster care is not a panacea. The trauma children suffer from suddenly being removed from their home and their siblings, to be placed in a strange home with a caregiver they don’t know, is well documented. But the alternative, allowing a child to remain in a dangerous home, should never be an alternative.

Naomi Schaefer Riley is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the author of “No Way to Treat a Child.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

It. involves looking after the eggs or the young until they are. independent, and to defend from predators, which is. important for species survival. By comparison with birds and mammals ...

In amphibians there are many devices for the protection of the eggs during the early stages of development and the youngs. In this way nature has practised economy in the number of eggs, which varies in direct proportion to the chances of destruction. Parental care is the care of the eggs or the youngs until they become able to protect themselves from the predators. These devices fail under ...

Care form, complexity and function. We have compiled a large and comprehensive dataset of parental care diversity in amphibians with information on presence or absence of care forms (attendance, transport, brooding, feeding and viviparity) at three developmental stages (egg, tadpole and juvenile) for 1322 species with no missing data (Fig. 1a; see also 'Data collection' in Methods ...

Amphibians are an ideal group in which to identify the ecological factors that have facilitated or constrained the evolution of different forms of parental care. Among, but also within, the three amphibian orders—Anura, Caudata, and Gymnophiona—there is a high level of variation in habitat use, fertilization mode, mating systems, and ...

The origin of parental care is a central question in evolutionary biology, and understating the evolution of this behaviour requires quantifying benefits and costs. To address this subject, we conducted a meta-analysis on amphibians, a group in which parental care has evolved multiple times.

In fact, more than two-thirds (456 of 685) of the papers that we found about parental care in amphibians were published since 1950 and focus on anurans. However, recent experimental work in anuran parental care is heavily biased toward Neotropical taxa, and in particular toward Dendrobatidae . This family exhibits particularly complex forms of ...

The paper is Schulte et al.'s (2020) review of research into amphibian parental care, a fascinating and essential read for all amphibian enthusiasts. Parental care is usually defined as 'non-gametic investments in offspring that incur a cost to the parent' and which provide some benefit to the offspring. ... Among the 500 or so papers ...

A recent study discovered possible parental care in the largest anuran, the charismatic and well-known goliath frog (Conraua goliath), but the details of this behaviour are unknown (Schäfer et al., 2019). This clearly shows that parental care can remain unnoticed even in familiar species and in species with non-caring close relatives.

Parental care is expected to evolve in species and in environments where the benefit to the offspring is the greatest relative to the cost (Shine, 1988; Clutton-Brock, 1991), for instance in physically harsh environments. As discussed, parental care predominates in amphibians with terrestrial modes of reproduction (Tables I and 11).

Parental care is extremely diverse across species, ranging from simple behaviours to complex adaptations, varying in duration and in which sex cares. Surprisingly, we know little about how such diversity has evolved. Here, using phylogenetic comparative methods and data for over 1300 amphibian species, we show that egg attendance, arguably one ...

First, we scored parental care as absent for a given species if it was scored as such in one or more of six recent large comparative datasets of amphibian parental care 55,62,63,64,65,66; where ...

The evolution of parental care diversity in amphibians. Parental care can take many forms but how this diversity arises is not well understood. Analyses of over 1300 amphibian species show that different forms of care evolve at different rates, prolonged care can be easily reduced, and biparental care is evolutionarily unstable.

This work has shown that parental care behavior in amphibians is influenced by environmental influences such as temperature, diet, and shellfish consumption. Abstract Despite rising interest among scientists for over two centuries, parental care behavior has not been as thoroughly studied in amphibians as it has in other taxa. The first reports of amphi...

Parental care in amphibians is most commonly found in geographical areas of correspondingly high species richness. Increased survivorship of the offspring is the main benefit of parental care, as documented quantitatively by numerous studies. Reduced fitness to the parent, measured by reduced future survival or reproductive success, is the ...

Parental care is extremely diverse across species, ranging from simple behaviours to complex adaptations, varying in duration and in which sex cares. Surprisingly, we know little about how such diversity has evolved. Here, using phylogenetic comparative methods and data for over 1300 amphibian species, we show that egg attendance, arguably one ...

Downloadable! Parental care is extremely diverse across species, ranging from simple behaviours to complex adaptations, varying in duration and in which sex cares. Surprisingly, we know little about how such diversity has evolved. Here, using phylogenetic comparative methods and data for over 1300 amphibian species, we show that egg attendance, arguably one of the simplest care behaviours, is ...

Amphibians are an excellent taxon in which to address these questions because, along with shes, they exhibit fi the greatest diversity of parental care forms of any vertebrate class, ranging from ...

Odile Oberlin. Download Free PDF. View PDF. Parental Care in Amphibia fIntroduction Methods Examples Fun ffParental care Looking after eggs/young ones fIndependent Defend from predators fSurvival Tropical region √ Anurans > Apodans ffMethods: 1.Protection by nests, nurseries/shelters f2.

Tree frog of South America (Phyllomedusa malabariens) ,Africa (Chiromatis) lts eggs on rolled up leaves hanging above water.The nest is covered by many leaves.Eggs develop into tadpoles.The tadpoles directly fall into the water.Further metamorphosis of larva take place in water.After two to three weeks tadpoles fall into water.

The use of foster care has been in decline even as more children are dying from abuse and neglect in their homes. In recent years, the number of children in foster care fell by nearly 16 percent ...

Parental care may be defined as any behavior exhibited by a parent toward its offspring that increases the }(( ]vP[ chances of survival (Trivers. 1972); this investment may reduce the v [ ability ...