- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

Business Management Case Study: A Complete Breakdown

Gain a comprehensive understanding of the "Business Management Case Study" as we break down the concept from start to finish. Discover the incredible journeys of companies like Apple Inc., Tesla and Netflix as they navigate innovation, global expansion, and transformation. This detailed analysis will provide insights into the dynamic world of business management.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- PMP® Certification Training Course

- Introduction to Management

- Introduction to Managing People

- CAPM® Certification Training Course

- Business Management Training Course

Case studies play a pivotal role in understanding real-world challenges, strategies, and outcomes in the ever-evolving field of Business Management. This blog dives into the intricacies of a compelling Business Management Case Study, dissecting its components to extract valuable insights for aspiring managers, entrepreneurs, and students alike. Learn the study behind some of the most significant Business Management Case Studies & how an online business degree can help you learn more in this article.

Table of Contents

1) What is Business Management?

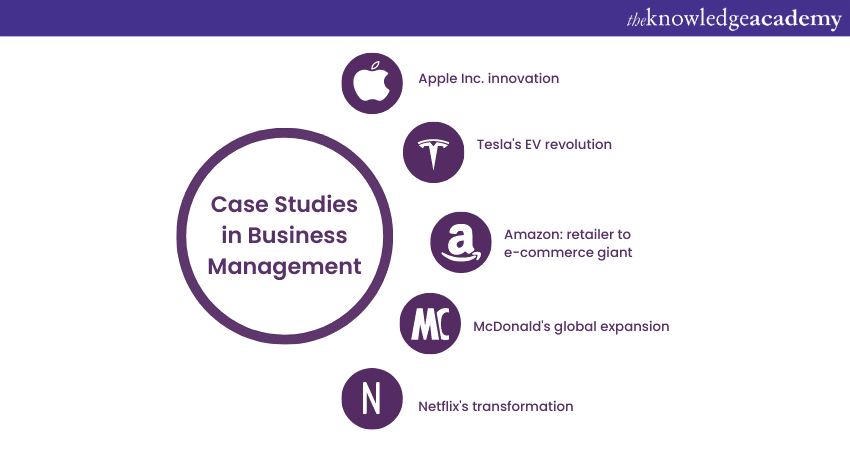

2) Case Studies in Business Management

a) Apple Inc. Innovation

b) Tesla’s EV revolution

c) Amazon retailer to e-commerce giant

d) McDonald’s global expansion

e) Netflix’s transformation

3) Conclusion

What is Business Management?

Business Management refers to the set of activities, strategies, and practices employed to oversee and coordinate an organisation's operations, resources, and personnel to achieve specific goals and objectives. It encompasses a wide range of responsibilities to ensure an organisation's efficient and effective functioning across various functional areas.

Try our Business Case Training Course today and start your career!

Case Studies in Business Management

Here are some of the notable case studies in the field of Business Management that have garnered attention due to their complexity, innovative strategies, and significant impact on their respective industries:

Apple Inc. innovation

a) Background: Apple Inc. is a global technology giant noted for its innovative products and design-driven approach. In the early 2000s, Apple faced intense competition and declining market share. The company needed to reinvent itself to remain relevant and competitive.

b) Problem statement: Apple's challenge was revitalising its product line and regaining market leadership while navigating a rapidly changing technological world.

c) Analysis of the situation: The Case Study dives into Apple's design thinking and customer-centric innovation to develop products that seamlessly blend form and function. The company's focus on user experience, ecosystem integration, and attention to detail set it apart from its competitors.

d) Proposed solutions: Apple's strategy involved launching breakthrough products like the iPod, iPhone, and iPad that redefined their respective markets. The company also invested heavily in creating a robust ecosystem through iTunes and the App Store.

e) Chosen strategy: Apple's commitment to user-centred design and innovation became the cornerstone of its success. The strategy encompassed cutting-edge technology, minimalist design, and exceptional user experience.

f) Implementation process: Apple's implementation involved rigorous research and development, collaboration among various teams, and meticulous attention to detail. The company also established a loyal customer base through iconic product launches and marketing campaigns.

g) Results and outcomes: Apple's strategy paid off immensely, leading to a resurgence in its market share, revenue, and brand value. The company's products became cultural touchstones, and its ecosystem approach set new standards for the technology industry.

Tesla’s EV revolution

a) Background: Tesla, led by Elon Musk, aimed to disrupt the traditional automotive industry by introducing electric vehicles (EVs) that combined sustainability, performance, and cutting-edge technology.

b) Problem statement: Tesla faced challenges related to the production, scalability, and market acceptance of electric vehicles in an industry dominated by internal combustion engine vehicles.

c) Analysis of the situation: This Case Study examines Tesla's unique approach, which combines innovation in electric powertrains, battery technology, and software. The company also adopted a direct-to-consumer sales model, bypassing traditional dealership networks.

d) Proposed solutions: Tesla's solutions included building a network of Supercharger stations, developing advanced autonomous driving technology, and leveraging over-the-air software updates to improve vehicle performance and features.

e) Chosen strategy: Tesla focused on high-quality engineering, creating a luxury brand image for EVs, and promoting a community of passionate supporters. The company also bet on long-term sustainability and energy innovation beyond just manufacturing cars.

f) Implementation process: Tesla faced production challenges, supply chain issues, and scepticism from traditional automakers. The company's determination to continuously refine its vehicles and technology resulted in incremental improvements and increased consumer interest.

g) Results and outcomes: Tesla's innovative approach catapulted it into the forefront of the EV market. The Model S, Model 3, Model X, and Model Y gained popularity for their performance, range, and technology. Tesla's market capitalisation surged, and the company played a significant part in changing the perception of electric vehicles.

Amazon retailer to e-commerce giant

a) Background: Amazon started as an online bookstore in the 1990s and quickly expanded its offerings to become the world's largest online retailer. However, its journey was riddled with challenges and risks.

b) Problem statement: Amazon faced difficulties in achieving profitability due to its aggressive expansion, heavy investments, and price competition. The company needed to find a way to sustain its growth and solidify its position in the e-commerce market.

c) Analysis of the situation: This Case Study explores Amazon's unique business model, which prioritises customer satisfaction, convenience, and diversification. The company continuously experimented with new ideas, services, and technologies.

d) Proposed solutions: Amazon's solutions included the introduction of Amazon Prime, the Kindle e-reader, and the development of its third-party seller marketplace. These initiatives aimed to enhance customer loyalty, expand product offerings, and increase revenue streams.

e) Chosen strategy: Amazon's strategy revolved around long-term thinking, customer obsession, and a willingness to invest heavily in innovation and infrastructure, even at the expense of short-term profits.

f) Implementation process: Amazon's implementation involved building a vast network of fulfilment centres, investing in advanced technology for logistics and supply chain management, and expanding its services beyond e-commerce into cloud computing (Amazon Web Services) and entertainment (Amazon Prime Video).

g) Results and outcomes: Amazon's strategy paid off as it transformed from an online bookstore to an e-commerce behemoth. The company not only achieved profitability but also diversified into various sectors, making Jeff Bezos the richest person in the world for a time.

McDonald’s global expansion

a) Background: McDonald's is one of the world's largest and most recognisable fast-food chains. The Case Study focuses on the company's global expansion strategy and challenges in adapting to diverse cultural preferences and market conditions.

b) Problem statement: McDonald's challenge was maintaining its brand identity while tailoring its menu offerings and marketing strategies to suit different countries' preferences and cultural norms.

c) Analysis: The Case Study analyses McDonald's localisation efforts, menu adaptations, and marketing campaigns in different countries. It explores how the company balances standardisation with customisation to appeal to local tastes.

d) Solutions and outcomes: McDonald's successfully combines global branding with localized strategies, resulting in sustained growth and customer loyalty in various markets. The Case Study demonstrates the importance of understanding cultural nuances in international business.

Netflix’s evolution

a) Background: Netflix started as a DVD rental-by-mail service and became a leading global streaming platform. The Case Study explores Netflix's strategic evolution, content production, and influence on the entertainment industry.

b) Problem statement: Netflix's challenge was transitioning from a traditional DVD rental business to a digital streaming service while competing with established cable networks and other streaming platforms.

c) Analysis: The Case Study analyses Netflix's shift to online streaming, its investment in original content production, and its use of data analytics to personalise user experiences and content recommendations.

d) Solutions and outcomes: Netflix's strategic pivot and focus on content quality and user experience contributed to its dominance in the streaming market. The Case Study illustrates how embracing digital disruption and customer-centric strategies can drive success.

Conclusion

These case studies offer valuable insights into different facets of Business Management, including innovation, strategic decision-making, customer-centric approaches, and market disruption. Analysing these cases provides aspiring managers and entrepreneurs with real-world examples of how effective strategies, risk-taking, and adaptability can lead to remarkable success in the dynamic business world.

Try our Business Analyst Training today for a rewarding career!

Frequently Asked Questions

Upcoming business skills resources batches & dates.

Fri 31st May 2024

Fri 26th Jul 2024

Fri 27th Sep 2024

Fri 29th Nov 2024

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Our biggest spring sale.

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Business Analysis Courses

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel Courses

- Microsoft Project

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Management →

- 26 Apr 2024

Deion Sanders' Prime Lessons for Leading a Team to Victory

The former star athlete known for flash uses unglamorous command-and-control methods to get results as a college football coach. Business leaders can learn 10 key lessons from the way 'Coach Prime' builds a culture of respect and discipline without micromanaging, says Hise Gibson.

- 02 Apr 2024

- What Do You Think?

What's Enough to Make Us Happy?

Experts say happiness is often derived by a combination of good health, financial wellbeing, and solid relationships with family and friends. But are we forgetting to take stock of whether we have enough of these things? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Research & Ideas

Employees Out Sick? Inside One Company's Creative Approach to Staying Productive

Regular absenteeism can hobble output and even bring down a business. But fostering a collaborative culture that brings managers together can help companies weather surges of sick days and no-shows. Research by Jorge Tamayo shows how.

- 12 Mar 2024

Publish or Perish: What the Research Says About Productivity in Academia

Universities tend to evaluate professors based on their research output, but does that measure reflect the realities of higher ed? A study of 4,300 professors by Kyle Myers, Karim Lakhani, and colleagues probes the time demands, risk appetite, and compensation of faculty.

- 29 Feb 2024

Beyond Goals: David Beckham's Playbook for Mobilizing Star Talent

Reach soccer's pinnacle. Become a global brand. Buy a team. Sign Lionel Messi. David Beckham makes success look as easy as his epic free kicks. But leveraging world-class talent takes discipline and deft decision-making, as case studies by Anita Elberse reveal. What could other businesses learn from his ascent?

- 16 Feb 2024

Is Your Workplace Biased Against Introverts?

Extroverts are more likely to express their passion outwardly, giving them a leg up when it comes to raises and promotions, according to research by Jon Jachimowicz. Introverts are just as motivated and excited about their work, but show it differently. How can managers challenge their assumptions?

- 05 Feb 2024

The Middle Manager of the Future: More Coaching, Less Commanding

Skilled middle managers foster collaboration, inspire employees, and link important functions at companies. An analysis of more than 35 million job postings by Letian Zhang paints a counterintuitive picture of today's midlevel manager. Could these roles provide an innovation edge?

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

Aggressive cost cutting and rocky leadership changes have eroded the culture at Boeing, a company once admired for its engineering rigor, says Bill George. What will it take to repair the reputational damage wrought by years of crises involving its 737 MAX?

- 16 Jan 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

How SolarWinds Responded to the 2020 SUNBURST Cyberattack

In December of 2020, SolarWinds learned that they had fallen victim to hackers. Unknown actors had inserted malware called SUNBURST into a software update, potentially granting hackers access to thousands of its customers’ data, including government agencies across the globe and the US military. General Counsel Jason Bliss needed to orchestrate the company’s response without knowing how many of its 300,000 customers had been affected, or how severely. What’s more, the existing CEO was scheduled to step down and incoming CEO Sudhakar Ramakrishna had yet to come on board. Bliss needed to immediately communicate the company’s action plan with customers and the media. In this episode of Cold Call, Professor Frank Nagle discusses SolarWinds’ response to this supply chain attack in the case, “SolarWinds Confronts SUNBURST.”

- 02 Jan 2024

Do Boomerang CEOs Get a Bad Rap?

Several companies have brought back formerly successful CEOs in hopes of breathing new life into their organizations—with mixed results. But are we even measuring the boomerang CEOs' performance properly? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 12 Dec 2023

COVID Tested Global Supply Chains. Here’s How They’ve Adapted

A global supply chain reshuffling is underway as companies seek to diversify their distribution networks in response to pandemic-related shocks, says research by Laura Alfaro. What do these shifts mean for American businesses and buyers?

- 05 Dec 2023

What Founders Get Wrong about Sales and Marketing

Which sales candidate is a startup’s ideal first hire? What marketing channels are best to invest in? How aggressively should an executive team align sales with customer success? Senior Lecturer Mark Roberge discusses how early-stage founders, sales leaders, and marketing executives can address these challenges as they grow their ventures in the case, “Entrepreneurial Sales and Marketing Vignettes.”

.jpg)

- 31 Oct 2023

Checking Your Ethics: Would You Speak Up in These 3 Sticky Situations?

Would you complain about a client who verbally abuses their staff? Would you admit to cutting corners on your work? The answers aren't always clear, says David Fubini, who tackles tricky scenarios in a series of case studies and offers his advice from the field.

- 12 Sep 2023

Can Remote Surgeries Digitally Transform Operating Rooms?

Launched in 2016, Proximie was a platform that enabled clinicians, proctors, and medical device company personnel to be virtually present in operating rooms, where they would use mixed reality and digital audio and visual tools to communicate with, mentor, assist, and observe those performing medical procedures. The goal was to improve patient outcomes. The company had grown quickly, and its technology had been used in tens of thousands of procedures in more than 50 countries and 500 hospitals. It had raised close to $50 million in equity financing and was now entering strategic partnerships to broaden its reach. Nadine Hachach-Haram, founder and CEO of Proximie, aspired for Proximie to become a platform that powered every operating room in the world, but she had to carefully consider the company’s partnership and data strategies in order to scale. What approach would position the company best for the next stage of growth? Harvard Business School associate professor Ariel Stern discusses creating value in health care through a digital transformation of operating rooms in her case, “Proximie: Using XR Technology to Create Borderless Operating Rooms.”

- 28 Aug 2023

The Clock Is Ticking: 3 Ways to Manage Your Time Better

Life is short. Are you using your time wisely? Leslie Perlow, Arthur Brooks, and DJ DiDonna offer time management advice to help you work smarter and live happier.

- 15 Aug 2023

Ryan Serhant: How to Manage Your Time for Happiness

Real estate entrepreneur, television star, husband, and father Ryan Serhant is incredibly busy and successful. He starts his days at 4:00 am and often doesn’t end them until 11:00 pm. But, it wasn’t always like that. In 2020, just a few months after the US began to shut down in order to prevent the spread of the Covid-19 virus, Serhant had time to reflect on his career as a real estate broker in New York City, wondering if the period of selling real estate at record highs was over. He considered whether he should stay at his current real estate brokerage or launch his own brokerage during a pandemic? Each option had very different implications for his time and flexibility. Professor Ashley Whillans and her co-author Hawken Lord (MBA 2023) discuss Serhant’s time management techniques and consider the lessons we can all learn about making time our most valuable commodity in the case, “Ryan Serhant: Time Management for Repeatable Success.”

- 08 Aug 2023

The Rise of Employee Analytics: Productivity Dream or Micromanagement Nightmare?

"People analytics"—using employee data to make management decisions—could soon transform the workplace and hiring, but implementation will be critical, says Jeffrey Polzer. After all, do managers really need to know about employees' every keystroke?

- 01 Aug 2023

Can Business Transform Primary Health Care Across Africa?

mPharma, headquartered in Ghana, is trying to create the largest pan-African health care company. Their mission is to provide primary care and a reliable and fairly priced supply of drugs in the nine African countries where they operate. Co-founder and CEO Gregory Rockson needs to decide which component of strategy to prioritize in the next three years. His options include launching a telemedicine program, expanding his pharmacies across the continent, and creating a new payment program to cover the cost of common medications. Rockson cares deeply about health equity, but his venture capital-financed company also must be profitable. Which option should he focus on expanding? Harvard Business School Professor Regina Herzlinger and case protagonist Gregory Rockson discuss the important role business plays in improving health care in the case, “mPharma: Scaling Access to Affordable Primary Care in Africa.”

- 05 Jul 2023

How Unilever Is Preparing for the Future of Work

Launched in 2016, Unilever’s Future of Work initiative aimed to accelerate the speed of change throughout the organization and prepare its workforce for a digitalized and highly automated era. But despite its success over the last three years, the program still faces significant challenges in its implementation. How should Unilever, one of the world's largest consumer goods companies, best prepare and upscale its workforce for the future? How should Unilever adapt and accelerate the speed of change throughout the organization? Is it even possible to lead a systematic, agile workforce transformation across several geographies while accounting for local context? Harvard Business School professor and faculty co-chair of the Managing the Future of Work Project William Kerr and Patrick Hull, Unilever’s vice president of global learning and future of work, discuss how rapid advances in artificial intelligence, machine learning, and automation are changing the nature of work in the case, “Unilever's Response to the Future of Work.”

How Are Middle Managers Falling Down Most Often on Employee Inclusion?

Companies are struggling to retain employees from underrepresented groups, many of whom don't feel heard in the workplace. What do managers need to do to build truly inclusive teams? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies of 2017

We generated a list of the 40 most popular Yale School of Management case studies in 2017 by combining data from our publishers, Google analytics, and other measures of interest and adoption. In compiling the list, we gave additional weight to usage outside Yale

We generated a list of the 40 most popular Yale School of Management case studies in 2017 by combining data from our publishers, Google analytics, and other measures of interest and adoption. In compiling the list, we gave additional weight to usage outside Yale.

Case topics represented on the list vary widely, but a number are drawn from the case team’s focus on healthcare, asset management, and sustainability. The cases also draw on Yale’s continued emphasis on corporate governance, ethics, and the role of business in state and society. Of note, nearly half of the most popular cases feature a woman as either the main protagonist or, in the case of raw cases where multiple characters take the place of a single protagonist, a major leader within the focal organization. While nearly a fourth of the cases were written in the past year, some of the most popular, including Cadbury and Design at Mayo, date from the early years of our program over a decade ago. Nearly two-thirds of the most popular cases were “raw” cases - Yale’s novel, web-based template which allows for a combination of text, documents, spreadsheets, and videos in a single case website.

Read on to learn more about the top 10 most popular cases followed by a complete list of the top 40 cases of 2017. A selection of the top 40 cases are available for purchase through our online store .

#1 - Coffee 2016

Faculty Supervision: Todd Cort

Coffee 2016 asks students to consider the coffee supply chain and generate ideas for what can be done to equalize returns across various stakeholders. The case draws a parallel between coffee and wine. Both beverages encourage connoisseurship, but only wine growers reap a premium for their efforts to ensure quality. The case describes the history of coffee production across the world, the rise of the “third wave” of coffee consumption in the developed world, the efforts of the Illy Company to help coffee growers, and the differences between “fair” trade and direct trade. Faculty have found the case provides a wide canvas to discuss supply chain issues, examine marketing practices, and encourage creative solutions to business problems.

#2 - AXA: Creating New Corporate Responsibility Metrics

Faculty Supervision: Todd Cort and David Bach

The case describes AXA’s corporate responsibility (CR) function. The company, a global leader in insurance and asset management, had distinguished itself in CR since formally establishing a CR unit in 2008. As the case opens, AXA’s CR unit is being moved from the marketing function to the strategy group occasioning a thorough review as to how CR should fit into AXA’s operations and strategy. Students are asked to identify CR issues of particular concern to the company, examine how addressing these issues would add value to the company, and then create metrics that would capture a business unit’s success or failure in addressing the concerns.

#3 - IBM Corporate Service Corps

Faculty Supervision: David Bach in cooperation with University of Ghana Business School and EGADE

The case considers IBM’s Corporate Service Corps (CSC), a program that had become the largest pro bono consulting program in the world. The case describes the program’s triple-benefit: leadership training to the brightest young IBMers, brand recognition for IBM in emerging markets, and community improvement in the areas served by IBM’s host organizations. As the program entered its second decade in 2016, students are asked to consider how the program can be improved. The case allows faculty to lead a discussion about training, marketing in emerging economies, and various ways of providing social benefit. The case highlights the synergies as well as trade-offs between pursuing these triple benefits.

#4 - Cadbury: An Ethical Company Struggles to Insure the Integrity of Its Supply Chain

Faculty Supervision: Ira Millstein

The case describes revelations that the production of cocoa in the Côte d’Ivoire involved child slave labor. These stories hit Cadbury especially hard. Cadbury's culture had been deeply rooted in the religious traditions of the company's founders, and the organization had paid close attention to the welfare of its workers and its sourcing practices. The US Congress was considering legislation that would allow chocolate grown on certified plantations to be labeled “slave labor free,” painting the rest of the industry in a bad light. Chocolate producers had asked for time to rectify the situation, but the extension they negotiated was running out. Students are asked whether Cadbury should join with the industry to lobby for more time? What else could Cadbury do to ensure its supply chain was ethically managed?

#5 - 360 State Real Options

Faculty Supervision: Matthew Spiegel

In 2010 developer Bruce Becker (SOM ‘85) completed 360 State Street, a major new construction project in downtown New Haven. Just west of the apartment building, a 6,000-square-foot pocket of land from the original parcel remained undeveloped. Becker had a number of alternatives to consider in regards to the site. He also had no obligation to build. He could bide his time. But Becker worried about losing out on rents should he wait too long. Students are asked under what set of circumstances and at what time would it be most advantageous to proceed?

#6 - Design at Mayo

Faculty Supervision: Rodrigo Canales and William Drentell

The case describes how the Mayo Clinic, one of the most prominent hospitals in the world, engaged designers and built a research institute, the Center for Innovation (CFI), to study the processes of healthcare provision. The case documents the many incremental innovations the designers were able to implement and the way designers learned to interact with physicians and vice-versa.

In 2010 there were questions about how the CFI would achieve its stated aspiration of “transformational change” in the healthcare field. Students are asked what would a major change in health care delivery look like? How should the CFI's impact be measured? Were the center's structure and processes appropriate for transformational change? Faculty have found this a great case to discuss institutional obstacles to innovation, the importance of culture in organizational change efforts, and the differences in types of innovation.

This case is freely available to the public.

#7 - Ant Financial

Faculty Supervision: K. Sudhir in cooperation with Renmin University of China School of Business

In 2015, Ant Financial’s MYbank (an offshoot of Jack Ma’s Alibaba company) was looking to extend services to rural areas in China by providing small loans to farmers. Microloans have always been costly for financial institutions to offer to the unbanked (though important in development) but MYbank believed that fintech innovations such as using the internet to communicate with loan applicants and judge their credit worthiness would make the program sustainable. Students are asked whether MYbank could operate the program at scale? Would its big data and technical analysis provide an accurate measure of credit risk for loans to small customers? Could MYbank rely on its new credit-scoring system to reduce operating costs to make the program sustainable?

#8 - Business Leadership in South Africa’s 1994 Reforms

Faculty Supervision: Ian Shapiro

This case examines the role of business in South Africa's historic transition away from apartheid to popular sovereignty. The case provides a previously untold oral history of this key moment in world history, presenting extensive video interviews with business leaders who spearheaded behind-the-scenes negotiations between the African National Congress and the government. Faculty teaching the case have used the material to push students to consider business’s role in a divided society and ask: What factors led business leaders to act to push the country's future away from isolation toward a "high road" of participating in an increasingly globalized economy? What techniques and narratives did they use to keep the two sides talking and resolve the political impasse? And, if business leadership played an important role in the events in South Africa, could they take a similar role elsewhere?

#9 - Shake Shack IPO

Faculty Supervision: Jake Thomas and Geert Rouwenhorst

From an art project in a New York City park, Shake Shack developed a devoted fan base that greeted new Shake Shack locations with cheers and long lines. When Shake Shack went public on January 30, 2015, investors displayed a similar enthusiasm. Opening day investors bid up the $21 per share offering price by 118% to reach $45.90 at closing bell. By the end of May, investors were paying $92.86 per share. Students are asked if this price represented a realistic valuation of the enterprise and if not, what was Shake Shack truly worth? The case provides extensive information on Shake Shack’s marketing, competitors, operations and financials, allowing instructors to weave a wide variety of factors into a valuation of the company.

#10 - Searching for a Search Fund Structure

Faculty Supervision: AJ Wasserstein

This case considers how young entrepreneurs structure search funds to find businesses to take over. The case describes an MBA student who meets with a number of successful search fund entrepreneurs who have taken alternative routes to raising funds. The case considers the issues of partnering, soliciting funds vs. self-funding a search, and joining an incubator. The case provides a platform from which to discuss the pros and cons of various search fund structures.

40 Most Popular Case Studies of 2017

Click on the case title to learn more about the dilemma. A selection of our most popular cases are available for purchase via our online store .

How to Write a Case Study: Bookmarkable Guide & Template

Published: November 30, 2023

Earning the trust of prospective customers can be a struggle. Before you can even begin to expect to earn their business, you need to demonstrate your ability to deliver on what your product or service promises.

Sure, you could say that you're great at X or that you're way ahead of the competition when it comes to Y. But at the end of the day, what you really need to win new business is cold, hard proof.

One of the best ways to prove your worth is through a compelling case study. In fact, HubSpot’s 2020 State of Marketing report found that case studies are so compelling that they are the fifth most commonly used type of content used by marketers.

Below, I'll walk you through what a case study is, how to prepare for writing one, what you need to include in it, and how it can be an effective tactic. To jump to different areas of this post, click on the links below to automatically scroll.

Case Study Definition

Case study templates, how to write a case study.

- How to Format a Case Study

Business Case Study Examples

A case study is a specific challenge a business has faced, and the solution they've chosen to solve it. Case studies can vary greatly in length and focus on several details related to the initial challenge and applied solution, and can be presented in various forms like a video, white paper, blog post, etc.

In professional settings, it's common for a case study to tell the story of a successful business partnership between a vendor and a client. Perhaps the success you're highlighting is in the number of leads your client generated, customers closed, or revenue gained. Any one of these key performance indicators (KPIs) are examples of your company's services in action.

When done correctly, these examples of your work can chronicle the positive impact your business has on existing or previous customers and help you attract new clients.

Free Case Study Templates

Showcase your company's success using these three free case study templates.

- Data-Driven Case Study Template

- Product-Specific Case Study Template

- General Case Study Template

You're all set!

Click this link to access this resource at any time.

Why write a case study?

I know, you’re thinking “ Okay, but why do I need to write one of these? ” The truth is that while case studies are a huge undertaking, they are powerful marketing tools that allow you to demonstrate the value of your product to potential customers using real-world examples. Here are a few reasons why you should write case studies.

1. Explain Complex Topics or Concepts

Case studies give you the space to break down complex concepts, ideas, and strategies and show how they can be applied in a practical way. You can use real-world examples, like an existing client, and use their story to create a compelling narrative that shows how your product solved their issue and how those strategies can be repeated to help other customers get similar successful results.

2. Show Expertise

Case studies are a great way to demonstrate your knowledge and expertise on a given topic or industry. This is where you get the opportunity to show off your problem-solving skills and how you’ve generated successful outcomes for clients you’ve worked with.

3. Build Trust and Credibility

In addition to showing off the attributes above, case studies are an excellent way to build credibility. They’re often filled with data and thoroughly researched, which shows readers you’ve done your homework. They can have confidence in the solutions you’ve presented because they’ve read through as you’ve explained the problem and outlined step-by-step what it took to solve it. All of these elements working together enable you to build trust with potential customers.

4. Create Social Proof

Using existing clients that have seen success working with your brand builds social proof . People are more likely to choose your brand if they know that others have found success working with you. Case studies do just that — putting your success on display for potential customers to see.

All of these attributes work together to help you gain more clients. Plus you can even use quotes from customers featured in these studies and repurpose them in other marketing content. Now that you know more about the benefits of producing a case study, let’s check out how long these documents should be.

How long should a case study be?

The length of a case study will vary depending on the complexity of the project or topic discussed. However, as a general guideline, case studies typically range from 500 to 1,500 words.

Whatever length you choose, it should provide a clear understanding of the challenge, the solution you implemented, and the results achieved. This may be easier said than done, but it's important to strike a balance between providing enough detail to make the case study informative and concise enough to keep the reader's interest.

The primary goal here is to effectively communicate the key points and takeaways of the case study. It’s worth noting that this shouldn’t be a wall of text. Use headings, subheadings, bullet points, charts, and other graphics to break up the content and make it more scannable for readers. We’ve also seen brands incorporate video elements into case studies listed on their site for a more engaging experience.

Ultimately, the length of your case study should be determined by the amount of information necessary to convey the story and its impact without becoming too long. Next, let’s look at some templates to take the guesswork out of creating one.

To help you arm your prospects with information they can trust, we've put together a step-by-step guide on how to create effective case studies for your business with free case study templates for creating your own.

Tell us a little about yourself below to gain access today:

And to give you more options, we’ll highlight some useful templates that serve different needs. But remember, there are endless possibilities when it comes to demonstrating the work your business has done.

1. General Case Study Template

Do you have a specific product or service that you’re trying to sell, but not enough reviews or success stories? This Product Specific case study template will help.

This template relies less on metrics, and more on highlighting the customer’s experience and satisfaction. As you follow the template instructions, you’ll be prompted to speak more about the benefits of the specific product, rather than your team’s process for working with the customer.

4. Bold Social Media Business Case Study Template

You can find templates that represent different niches, industries, or strategies that your business has found success in — like a bold social media business case study template.

In this template, you can tell the story of how your social media marketing strategy has helped you or your client through collaboration or sale of your service. Customize it to reflect the different marketing channels used in your business and show off how well your business has been able to boost traffic, engagement, follows, and more.

5. Lead Generation Business Case Study Template

It’s important to note that not every case study has to be the product of a sale or customer story, sometimes they can be informative lessons that your own business has experienced. A great example of this is the Lead Generation Business case study template.

If you’re looking to share operational successes regarding how your team has improved processes or content, you should include the stories of different team members involved, how the solution was found, and how it has made a difference in the work your business does.

Now that we’ve discussed different templates and ideas for how to use them, let’s break down how to create your own case study with one.

- Get started with case study templates.

- Determine the case study's objective.

- Establish a case study medium.

- Find the right case study candidate.

- Contact your candidate for permission to write about them.

- Ensure you have all the resources you need to proceed once you get a response.

- Download a case study email template.

- Define the process you want to follow with the client.

- Ensure you're asking the right questions.

- Layout your case study format.

- Publish and promote your case study.

1. Get started with case study templates.

Telling your customer's story is a delicate process — you need to highlight their success while naturally incorporating your business into their story.

If you're just getting started with case studies, we recommend you download HubSpot's Case Study Templates we mentioned before to kickstart the process.

2. Determine the case study's objective.

All business case studies are designed to demonstrate the value of your services, but they can focus on several different client objectives.

Your first step when writing a case study is to determine the objective or goal of the subject you're featuring. In other words, what will the client have succeeded in doing by the end of the piece?

The client objective you focus on will depend on what you want to prove to your future customers as a result of publishing this case study.

Your case study can focus on one of the following client objectives:

- Complying with government regulation

- Lowering business costs

- Becoming profitable

- Generating more leads

- Closing on more customers

- Generating more revenue

- Expanding into a new market

- Becoming more sustainable or energy-efficient

3. Establish a case study medium.

Next, you'll determine the medium in which you'll create the case study. In other words, how will you tell this story?

Case studies don't have to be simple, written one-pagers. Using different media in your case study can allow you to promote your final piece on different channels. For example, while a written case study might just live on your website and get featured in a Facebook post, you can post an infographic case study on Pinterest and a video case study on your YouTube channel.

Here are some different case study mediums to consider:

Written Case Study

Consider writing this case study in the form of an ebook and converting it to a downloadable PDF. Then, gate the PDF behind a landing page and form for readers to fill out before downloading the piece, allowing this case study to generate leads for your business.

Video Case Study

Plan on meeting with the client and shooting an interview. Seeing the subject, in person, talk about the service you provided them can go a long way in the eyes of your potential customers.

Infographic Case Study

Use the long, vertical format of an infographic to tell your success story from top to bottom. As you progress down the infographic, emphasize major KPIs using bigger text and charts that show the successes your client has had since working with you.

Podcast Case Study

Podcasts are a platform for you to have a candid conversation with your client. This type of case study can sound more real and human to your audience — they'll know the partnership between you and your client was a genuine success.

4. Find the right case study candidate.

Writing about your previous projects requires more than picking a client and telling a story. You need permission, quotes, and a plan. To start, here are a few things to look for in potential candidates.

Product Knowledge

It helps to select a customer who's well-versed in the logistics of your product or service. That way, he or she can better speak to the value of what you offer in a way that makes sense for future customers.

Remarkable Results

Clients that have seen the best results are going to make the strongest case studies. If their own businesses have seen an exemplary ROI from your product or service, they're more likely to convey the enthusiasm that you want prospects to feel, too.

One part of this step is to choose clients who have experienced unexpected success from your product or service. When you've provided non-traditional customers — in industries that you don't usually work with, for example — with positive results, it can help to remove doubts from prospects.

Recognizable Names

While small companies can have powerful stories, bigger or more notable brands tend to lend credibility to your own. In fact, 89% of consumers say they'll buy from a brand they already recognize over a competitor, especially if they already follow them on social media.

Customers that came to you after working with a competitor help highlight your competitive advantage and might even sway decisions in your favor.

5. Contact your candidate for permission to write about them.

To get the case study candidate involved, you have to set the stage for clear and open communication. That means outlining expectations and a timeline right away — not having those is one of the biggest culprits in delayed case study creation.

Most importantly at this point, however, is getting your subject's approval. When first reaching out to your case study candidate, provide them with the case study's objective and format — both of which you will have come up with in the first two steps above.

To get this initial permission from your subject, put yourself in their shoes — what would they want out of this case study? Although you're writing this for your own company's benefit, your subject is far more interested in the benefit it has for them.

Benefits to Offer Your Case Study Candidate

Here are four potential benefits you can promise your case study candidate to gain their approval.

Brand Exposure

Explain to your subject to whom this case study will be exposed, and how this exposure can help increase their brand awareness both in and beyond their own industry. In the B2B sector, brand awareness can be hard to collect outside one's own market, making case studies particularly useful to a client looking to expand their name's reach.

Employee Exposure

Allow your subject to provide quotes with credits back to specific employees. When this is an option for them, their brand isn't the only thing expanding its reach — their employees can get their name out there, too. This presents your subject with networking and career development opportunities they might not have otherwise.

Product Discount

This is a more tangible incentive you can offer your case study candidate, especially if they're a current customer of yours. If they agree to be your subject, offer them a product discount — or a free trial of another product — as a thank-you for their help creating your case study.

Backlinks and Website Traffic

Here's a benefit that is sure to resonate with your subject's marketing team: If you publish your case study on your website, and your study links back to your subject's website — known as a "backlink" — this small gesture can give them website traffic from visitors who click through to your subject's website.

Additionally, a backlink from you increases your subject's page authority in the eyes of Google. This helps them rank more highly in search engine results and collect traffic from readers who are already looking for information about their industry.

6. Ensure you have all the resources you need to proceed once you get a response.

So you know what you’re going to offer your candidate, it’s time that you prepare the resources needed for if and when they agree to participate, like a case study release form and success story letter.

Let's break those two down.

Case Study Release Form

This document can vary, depending on factors like the size of your business, the nature of your work, and what you intend to do with the case studies once they are completed. That said, you should typically aim to include the following in the Case Study Release Form:

- A clear explanation of why you are creating this case study and how it will be used.

- A statement defining the information and potentially trademarked information you expect to include about the company — things like names, logos, job titles, and pictures.

- An explanation of what you expect from the participant, beyond the completion of the case study. For example, is this customer willing to act as a reference or share feedback, and do you have permission to pass contact information along for these purposes?

- A note about compensation.

Success Story Letter

As noted in the sample email, this document serves as an outline for the entire case study process. Other than a brief explanation of how the customer will benefit from case study participation, you'll want to be sure to define the following steps in the Success Story Letter.

7. Download a case study email template.

While you gathered your resources, your candidate has gotten time to read over the proposal. When your candidate approves of your case study, it's time to send them a release form.

A case study release form tells you what you'll need from your chosen subject, like permission to use any brand names and share the project information publicly. Kick-off this process with an email that runs through exactly what they can expect from you, as well as what you need from them. To give you an idea of what that might look like, check out this sample email:

8. Define the process you want to follow with the client.

Before you can begin the case study, you have to have a clear outline of the case study process with your client. An example of an effective outline would include the following information.

The Acceptance

First, you'll need to receive internal approval from the company's marketing team. Once approved, the Release Form should be signed and returned to you. It's also a good time to determine a timeline that meets the needs and capabilities of both teams.

The Questionnaire

To ensure that you have a productive interview — which is one of the best ways to collect information for the case study — you'll want to ask the participant to complete a questionnaire before this conversation. That will provide your team with the necessary foundation to organize the interview, and get the most out of it.

The Interview

Once the questionnaire is completed, someone on your team should reach out to the participant to schedule a 30- to 60-minute interview, which should include a series of custom questions related to the customer's experience with your product or service.

The Draft Review

After the case study is composed, you'll want to send a draft to the customer, allowing an opportunity to give you feedback and edits.

The Final Approval

Once any necessary edits are completed, send a revised copy of the case study to the customer for final approval.

Once the case study goes live — on your website or elsewhere — it's best to contact the customer with a link to the page where the case study lives. Don't be afraid to ask your participants to share these links with their own networks, as it not only demonstrates your ability to deliver positive results and impressive growth, as well.

9. Ensure you're asking the right questions.

Before you execute the questionnaire and actual interview, make sure you're setting yourself up for success. A strong case study results from being prepared to ask the right questions. What do those look like? Here are a few examples to get you started:

- What are your goals?

- What challenges were you experiencing before purchasing our product or service?

- What made our product or service stand out against our competitors?

- What did your decision-making process look like?

- How have you benefited from using our product or service? (Where applicable, always ask for data.)

Keep in mind that the questionnaire is designed to help you gain insights into what sort of strong, success-focused questions to ask during the actual interview. And once you get to that stage, we recommend that you follow the "Golden Rule of Interviewing." Sounds fancy, right? It's actually quite simple — ask open-ended questions.

If you're looking to craft a compelling story, "yes" or "no" answers won't provide the details you need. Focus on questions that invite elaboration, such as, "Can you describe ...?" or, "Tell me about ..."

In terms of the interview structure, we recommend categorizing the questions and flowing them into six specific sections that will mirror a successful case study format. Combined, they'll allow you to gather enough information to put together a rich, comprehensive study.

Open with the customer's business.

The goal of this section is to generate a better understanding of the company's current challenges and goals, and how they fit into the landscape of their industry. Sample questions might include:

- How long have you been in business?

- How many employees do you have?

- What are some of the objectives of your department at this time?

Cite a problem or pain point.

To tell a compelling story, you need context. That helps match the customer's need with your solution. Sample questions might include:

- What challenges and objectives led you to look for a solution?

- What might have happened if you did not identify a solution?

- Did you explore other solutions before this that did not work out? If so, what happened?

Discuss the decision process.

Exploring how the customer decided to work with you helps to guide potential customers through their own decision-making processes. Sample questions might include:

- How did you hear about our product or service?

- Who was involved in the selection process?

- What was most important to you when evaluating your options?

Explain how a solution was implemented.

The focus here should be placed on the customer's experience during the onboarding process. Sample questions might include:

- How long did it take to get up and running?

- Did that meet your expectations?

- Who was involved in the process?

Explain how the solution works.

The goal of this section is to better understand how the customer is using your product or service. Sample questions might include:

- Is there a particular aspect of the product or service that you rely on most?

- Who is using the product or service?

End with the results.

In this section, you want to uncover impressive measurable outcomes — the more numbers, the better. Sample questions might include:

- How is the product or service helping you save time and increase productivity?

- In what ways does that enhance your competitive advantage?

- How much have you increased metrics X, Y, and Z?

10. Lay out your case study format.

When it comes time to take all of the information you've collected and actually turn it into something, it's easy to feel overwhelmed. Where should you start? What should you include? What's the best way to structure it?

To help you get a handle on this step, it's important to first understand that there is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to the ways you can present a case study. They can be very visual, which you'll see in some of the examples we've included below, and can sometimes be communicated mostly through video or photos, with a bit of accompanying text.

Here are the sections we suggest, which we'll cover in more detail down below:

- Title: Keep it short. Develop a succinct but interesting project name you can give the work you did with your subject.

- Subtitle: Use this copy to briefly elaborate on the accomplishment. What was done? The case study itself will explain how you got there.

- Executive Summary : A 2-4 sentence summary of the entire story. You'll want to follow it with 2-3 bullet points that display metrics showcasing success.

- About the Subject: An introduction to the person or company you served, which can be pulled from a LinkedIn Business profile or client website.

- Challenges and Objectives: A 2-3 paragraph description of the customer's challenges, before using your product or service. This section should also include the goals or objectives the customer set out to achieve.

- How Product/Service Helped: A 2-3 paragraph section that describes how your product or service provided a solution to their problem.

- Results: A 2-3 paragraph testimonial that proves how your product or service specifically benefited the person or company and helped achieve its goals. Include numbers to quantify your contributions.

- Supporting Visuals or Quotes: Pick one or two powerful quotes that you would feature at the bottom of the sections above, as well as a visual that supports the story you are telling.

- Future Plans: Everyone likes an epilogue. Comment on what's ahead for your case study subject, whether or not those plans involve you.

- Call to Action (CTA): Not every case study needs a CTA, but putting a passive one at the end of your case study can encourage your readers to take an action on your website after learning about the work you've done.

When laying out your case study, focus on conveying the information you've gathered in the most clear and concise way possible. Make it easy to scan and comprehend, and be sure to provide an attractive call-to-action at the bottom — that should provide readers an opportunity to learn more about your product or service.

11. Publish and promote your case study.

Once you've completed your case study, it's time to publish and promote it. Some case study formats have pretty obvious promotional outlets — a video case study can go on YouTube, just as an infographic case study can go on Pinterest.

But there are still other ways to publish and promote your case study. Here are a couple of ideas:

Lead Gen in a Blog Post

As stated earlier in this article, written case studies make terrific lead-generators if you convert them into a downloadable format, like a PDF. To generate leads from your case study, consider writing a blog post that tells an abbreviated story of your client's success and asking readers to fill out a form with their name and email address if they'd like to read the rest in your PDF.

Then, promote this blog post on social media, through a Facebook post or a tweet.

Published as a Page on Your Website

As a growing business, you might need to display your case study out in the open to gain the trust of your target audience.

Rather than gating it behind a landing page, publish your case study to its own page on your website, and direct people here from your homepage with a "Case Studies" or "Testimonials" button along your homepage's top navigation bar.

Format for a Case Study

The traditional case study format includes the following parts: a title and subtitle, a client profile, a summary of the customer’s challenges and objectives, an account of how your solution helped, and a description of the results. You might also want to include supporting visuals and quotes, future plans, and calls-to-action.

Image Source

The title is one of the most important parts of your case study. It should draw readers in while succinctly describing the potential benefits of working with your company. To that end, your title should:

- State the name of your custome r. Right away, the reader must learn which company used your products and services. This is especially important if your customer has a recognizable brand. If you work with individuals and not companies, you may omit the name and go with professional titles: “A Marketer…”, “A CFO…”, and so forth.

- State which product your customer used . Even if you only offer one product or service, or if your company name is the same as your product name, you should still include the name of your solution. That way, readers who are not familiar with your business can become aware of what you sell.

- Allude to the results achieved . You don’t necessarily need to provide hard numbers, but the title needs to represent the benefits, quickly. That way, if a reader doesn’t stay to read, they can walk away with the most essential information: Your product works.

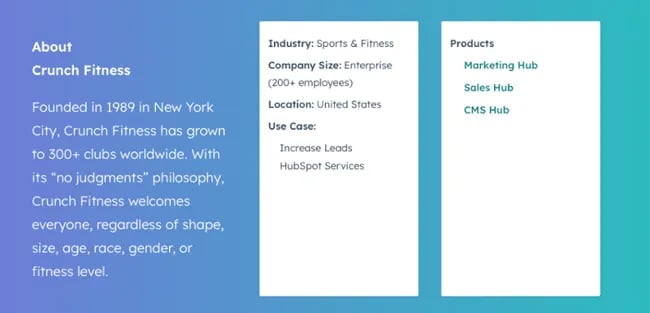

The example above, “Crunch Fitness Increases Leads and Signups With HubSpot,” achieves all three — without being wordy. Keeping your title short and sweet is also essential.

2. Subtitle

Your subtitle is another essential part of your case study — don’t skip it, even if you think you’ve done the work with the title. In this section, include a brief summary of the challenges your customer was facing before they began to use your products and services. Then, drive the point home by reiterating the benefits your customer experienced by working with you.

The above example reads:

“Crunch Fitness was franchising rapidly when COVID-19 forced fitness clubs around the world to close their doors. But the company stayed agile by using HubSpot to increase leads and free trial signups.”

We like that the case study team expressed the urgency of the problem — opening more locations in the midst of a pandemic — and placed the focus on the customer’s ability to stay agile.

3. Executive Summary

The executive summary should provide a snapshot of your customer, their challenges, and the benefits they enjoyed from working with you. Think it’s too much? Think again — the purpose of the case study is to emphasize, again and again, how well your product works.

The good news is that depending on your design, the executive summary can be mixed with the subtitle or with the “About the Company” section. Many times, this section doesn’t need an explicit “Executive Summary” subheading. You do need, however, to provide a convenient snapshot for readers to scan.

In the above example, ADP included information about its customer in a scannable bullet-point format, then provided two sections: “Business Challenge” and “How ADP Helped.” We love how simple and easy the format is to follow for those who are unfamiliar with ADP or its typical customer.

4. About the Company

Readers need to know and understand who your customer is. This is important for several reasons: It helps your reader potentially relate to your customer, it defines your ideal client profile (which is essential to deter poor-fit prospects who might have reached out without knowing they were a poor fit), and it gives your customer an indirect boon by subtly promoting their products and services.

Feel free to keep this section as simple as possible. You can simply copy and paste information from the company’s LinkedIn, use a quote directly from your customer, or take a more creative storytelling approach.

In the above example, HubSpot included one paragraph of description for Crunch Fitness and a few bullet points. Below, ADP tells the story of its customer using an engaging, personable technique that effectively draws readers in.

5. Challenges and Objectives

The challenges and objectives section of your case study is the place to lay out, in detail, the difficulties your customer faced prior to working with you — and what they hoped to achieve when they enlisted your help.

In this section, you can be as brief or as descriptive as you’d like, but remember: Stress the urgency of the situation. Don’t understate how much your customer needed your solution (but don’t exaggerate and lie, either). Provide contextual information as necessary. For instance, the pandemic and societal factors may have contributed to the urgency of the need.

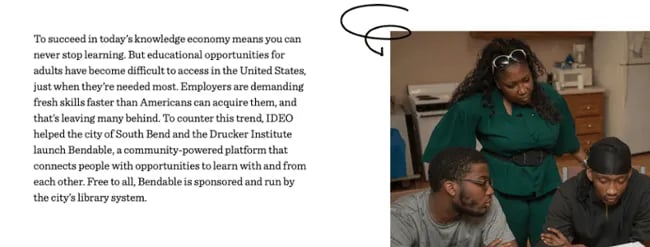

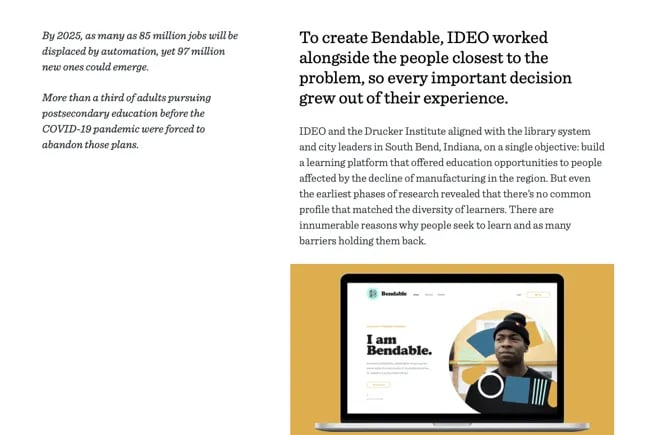

Take the above example from design consultancy IDEO:

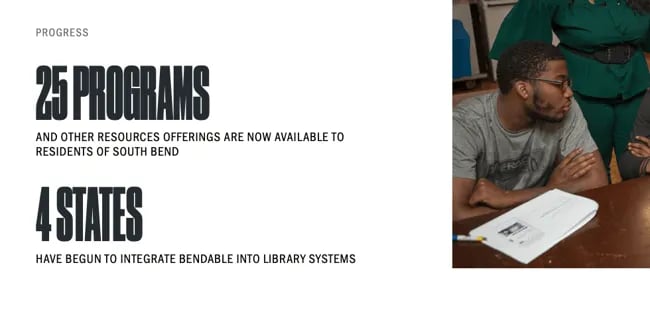

“Educational opportunities for adults have become difficult to access in the United States, just when they’re needed most. To counter this trend, IDEO helped the city of South Bend and the Drucker Institute launch Bendable, a community-powered platform that connects people with opportunities to learn with and from each other.”

We love how IDEO mentions the difficulties the United States faces at large, the efforts its customer is taking to address these issues, and the steps IDEO took to help.

6. How Product/Service Helped

This is where you get your product or service to shine. Cover the specific benefits that your customer enjoyed and the features they gleaned the most use out of. You can also go into detail about how you worked with and for your customer. Maybe you met several times before choosing the right solution, or you consulted with external agencies to create the best package for them.

Whatever the case may be, try to illustrate how easy and pain-free it is to work with the representatives at your company. After all, potential customers aren’t looking to just purchase a product. They’re looking for a dependable provider that will strive to exceed their expectations.

In the above example, IDEO describes how it partnered with research institutes and spoke with learners to create Bendable, a free educational platform. We love how it shows its proactivity and thoroughness. It makes potential customers feel that IDEO might do something similar for them.

The results are essential, and the best part is that you don’t need to write the entirety of the case study before sharing them. Like HubSpot, IDEO, and ADP, you can include the results right below the subtitle or executive summary. Use data and numbers to substantiate the success of your efforts, but if you don’t have numbers, you can provide quotes from your customers.

We can’t overstate the importance of the results. In fact, if you wanted to create a short case study, you could include your title, challenge, solution (how your product helped), and result.

8. Supporting Visuals or Quotes

Let your customer speak for themselves by including quotes from the representatives who directly interfaced with your company.

Visuals can also help, even if they’re stock images. On one side, they can help you convey your customer’s industry, and on the other, they can indirectly convey your successes. For instance, a picture of a happy professional — even if they’re not your customer — will communicate that your product can lead to a happy client.

In this example from IDEO, we see a man standing in a boat. IDEO’s customer is neither the man pictured nor the manufacturer of the boat, but rather Conservation International, an environmental organization. This imagery provides a visually pleasing pattern interrupt to the page, while still conveying what the case study is about.

9. Future Plans

This is optional, but including future plans can help you close on a more positive, personable note than if you were to simply include a quote or the results. In this space, you can show that your product will remain in your customer’s tech stack for years to come, or that your services will continue to be instrumental to your customer’s success.

Alternatively, if you work only on time-bound projects, you can allude to the positive impact your customer will continue to see, even after years of the end of the contract.

10. Call to Action (CTA)

Not every case study needs a CTA, but we’d still encourage it. Putting one at the end of your case study will encourage your readers to take an action on your website after learning about the work you've done.

It will also make it easier for them to reach out, if they’re ready to start immediately. You don’t want to lose business just because they have to scroll all the way back up to reach out to your team.

To help you visualize this case study outline, check out the case study template below, which can also be downloaded here .

You drove the results, made the connection, set the expectations, used the questionnaire to conduct a successful interview, and boiled down your findings into a compelling story. And after all of that, you're left with a little piece of sales enabling gold — a case study.

To show you what a well-executed final product looks like, have a look at some of these marketing case study examples.

1. "Shopify Uses HubSpot CRM to Transform High Volume Sales Organization," by HubSpot

What's interesting about this case study is the way it leads with the customer. This reflects a major HubSpot value, which is to always solve for the customer first. The copy leads with a brief description of why Shopify uses HubSpot and is accompanied by a short video and some basic statistics on the company.

Notice that this case study uses mixed media. Yes, there is a short video, but it's elaborated upon in the additional text on the page. So, while case studies can use one or the other, don't be afraid to combine written copy with visuals to emphasize the project's success.

2. "New England Journal of Medicine," by Corey McPherson Nash

When branding and design studio Corey McPherson Nash showcases its work, it makes sense for it to be visual — after all, that's what they do. So in building the case study for the studio's work on the New England Journal of Medicine's integrated advertising campaign — a project that included the goal of promoting the client's digital presence — Corey McPherson Nash showed its audience what it did, rather than purely telling it.

Notice that the case study does include some light written copy — which includes the major points we've suggested — but lets the visuals do the talking, allowing users to really absorb the studio's services.

3. "Designing the Future of Urban Farming," by IDEO

Here's a design company that knows how to lead with simplicity in its case studies. As soon as the visitor arrives at the page, he or she is greeted with a big, bold photo, and two very simple columns of text — "The Challenge" and "The Outcome."

Immediately, IDEO has communicated two of the case study's major pillars. And while that's great — the company created a solution for vertical farming startup INFARM's challenge — it doesn't stop there. As the user scrolls down, those pillars are elaborated upon with comprehensive (but not overwhelming) copy that outlines what that process looked like, replete with quotes and additional visuals.

4. "Secure Wi-Fi Wins Big for Tournament," by WatchGuard

Then, there are the cases when visuals can tell almost the entire story — when executed correctly. Network security provider WatchGuard can do that through this video, which tells the story of how its services enhanced the attendee and vendor experience at the Windmill Ultimate Frisbee tournament.

5. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Boosts Social Media Engagement and Brand Awareness with HubSpot

In the case study above , HubSpot uses photos, videos, screenshots, and helpful stats to tell the story of how the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame used the bot, CRM, and social media tools to gain brand awareness.

6. Small Desk Plant Business Ups Sales by 30% With Trello

This case study from Trello is straightforward and easy to understand. It begins by explaining the background of the company that decided to use it, what its goals were, and how it planned to use Trello to help them.

It then goes on to discuss how the software was implemented and what tasks and teams benefited from it. Towards the end, it explains the sales results that came from implementing the software and includes quotes from decision-makers at the company that implemented it.

7. Facebook's Mercedes Benz Success Story

Facebook's Success Stories page hosts a number of well-designed and easy-to-understand case studies that visually and editorially get to the bottom line quickly.

Each study begins with key stats that draw the reader in. Then it's organized by highlighting a problem or goal in the introduction, the process the company took to reach its goals, and the results. Then, in the end, Facebook notes the tools used in the case study.

Showcasing Your Work

You work hard at what you do. Now, it's time to show it to the world — and, perhaps more important, to potential customers. Before you show off the projects that make you the proudest, we hope you follow these important steps that will help you effectively communicate that work and leave all parties feeling good about it.

Editor's Note: This blog post was originally published in February 2017 but was updated for comprehensiveness and freshness in July 2021.

Don't forget to share this post!

Related articles.

How to Market an Ebook: 21 Ways to Promote Your Content Offers

![case study for business management 7 Pieces of Content Your Audience Really Wants to See [New Data]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/most%20popular%20types%20of%20content.jpg)

7 Pieces of Content Your Audience Really Wants to See [New Data]

![case study for business management How to Write a Listicle [+ Examples and Ideas]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/listicle-1.jpg)

How to Write a Listicle [+ Examples and Ideas]

28 Case Study Examples Every Marketer Should See

![case study for business management What Is a White Paper? [FAQs]](https://blog.hubspot.com/hubfs/business%20whitepaper.jpg)

What Is a White Paper? [FAQs]

What is an Advertorial? 8 Examples to Help You Write One

How to Create Marketing Offers That Don't Fall Flat

20 Creative Ways To Repurpose Content

16 Important Ways to Use Case Studies in Your Marketing

11 Ways to Make Your Blog Post Interactive

Showcase your company's success using these free case study templates.

Marketing software that helps you drive revenue, save time and resources, and measure and optimize your investments — all on one easy-to-use platform

How to Write a Great Business Case

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

C ase studies are powerful teaching tools. “When you have a good case, and students who are well prepared to learn and to teach each other, you get some magical moments that students will never forget,” says James L. Heskett, UPS Foundation Professor of Business Logistics, emeritus, at Harvard Business School (HBS). “They will remember the lessons they learn in that class discussion and apply them 20 years later.”

Yet, for many educators who want to pen their own case, the act of writing a great business case seldom comes easily or naturally. For starters, it’s time consuming. Case writers can spend substantial time visiting companies, securing a willing site, conducting interviews, observing operations, collecting data, reviewing notes, writing the case, revising the narrative, ensuring that teaching points come through, and then getting executives to approve the finished product.

The question, then, becomes: Where do you begin? How do you approach case writing? How do you decide which company to use as the subject of the case? And what distinguishes a well-written case from a mediocre one?

We asked three expert HBS case writers—who collectively have written and supported hundreds of cases—to share their insights on how to write a great business case study that will inspire passionate classroom discussion and transmit key educational concepts.

Insights from James L. Heskett

UPS Foundation Professor of Business Logistics, Emeritus, Harvard Business School

Keep your eyes open for a great business issue.

“I’m always on the prowl for new case material. Whenever I’m reading or consulting, I look for interesting people doing interesting things and facing interesting challenges. For instance, I was reading a magazine and came across a story about how Shouldice Hospital treated patients undergoing surgery to fix inguinal hernias—how patients would get up from the operating table and walk away on the arm of the surgeon.

6 QUALITIES OF GREAT CASE WRITERS

Comfort with ambiguity, since cases may have more than one “right” answer

Command of the topic or subject at hand

Ability to relate to the case protagonists

Enthusiasm for the case teaching method

Capacity for finding the drama in a business situation and making it feel personal to students

Build relationships with executives.