Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to write a dbq essay: key strategies and tips.

Advanced Placement (AP)

The DBQ, or document-based-question, is a somewhat unusually-formatted timed essay on the AP History Exams: AP US History, AP European History, and AP World History. Because of its unfamiliarity, many students are at a loss as to how to even prepare, let alone how to write a successful DBQ essay on test day.

Never fear! I, the DBQ wizard and master, have a wealth of preparation strategies for you, as well as advice on how to cram everything you need to cover into your limited DBQ writing time on exam day. When you're done reading this guide, you'll know exactly how to write a DBQ.

For a general overview of the DBQ—what it is, its purpose, its format, etc.—see my article "What is a DBQ?"

Table of Contents

What Should My Study Timeline Be?

Preparing for the DBQ

Establish a Baseline

Foundational Skills

Rubric Breakdown

Take Another Practice DBQ

How Can I Succeed on Test Day?

Reading the Question and Documents

Planning Your Essay

Writing Your Essay

Key Takeaways

What Should My DBQ Study Timeline Be?

Your AP exam study timeline depends on a few things. First, how much time you have to study per week, and how many hours you want to study in total? If you don't have much time per week, start a little earlier; if you will be able to devote a substantial amount of time per week (10-15 hours) to prep, you can wait until later in the year.

One thing to keep in mind, though, is that the earlier you start studying for your AP test, the less material you will have covered in class. Make sure you continually review older material as the school year goes on to keep things fresh in your mind, but in terms of DBQ prep it probably doesn't make sense to start before February or January at the absolute earliest.

Another factor is how much you need to work on. I recommend you complete a baseline DBQ around early February to see where you need to focus your efforts.

If, for example, you got a six out of seven and missed one point for doing further document analysis, you won't need to spend too much time studying how to write a DBQ. Maybe just do a document analysis exercise every few weeks and check in a couple months later with another timed practice DBQ to make sure you've got it.

However, if you got a two or three out of seven, you'll know you have more work to do, and you'll probably want to devote at least an hour or two every week to honing your skills.

The general flow of your preparation should be: take a practice DBQ, do focused skills practice, take another practice DBQ, do focused skills practice, take another practice DBQ, and so on. How often you take the practice DBQs and how many times you repeat the cycle really depends on how much preparation you need, and how often you want to check your progress. Take practice DBQs often enough that the format stays familiar, but not so much that you've done barely any skills practice in between.

He's ready to start studying!

The general preparation process is to diagnose, practice, test, and repeat. First, you'll figure out what you need to work on by establishing a baseline level for your DBQ skills. Then, you'll practice building skills. Finally, you'll take another DBQ to see how you've improved and what you still need to work on.

In this next section, I'll go over the whole process. First, I'll give guidance on how to establish a baseline. Then I'll go over some basic, foundational essay-writing skills and how to build them. After that I'll break down the DBQ rubric. You'll be acing practice DBQs before you know it!

#1: Establish a Baseline

The first thing you need to do is to establish a baseline— figure out where you are at with respect to your DBQ skills. This will let you know where you need to focus your preparation efforts.

To do this, you will take a timed, practice DBQ and have a trusted teacher or advisor grade it according to the appropriate rubric.

AP US History

For the AP US History DBQ, you'll be given a 15-minute reading period and 45 minutes of writing time.

A selection of practice questions from the exam can be found online at the College Board, including a DBQ. (Go to page 136 in the linked document for the practice prompt.)

If you've already seen this practice question, perhaps in class, you might use the 2015 DBQ question .

Other available College Board DBQs are going to be in the old format (find them in the "Free-Response Questions" documents). This is fine if you need to use them, but be sure to use the new rubric (which is out of seven points, rather than nine) to grade.

I advise you to save all these links , or even download all the Free Response Questions and the Scoring Guides, for reference because you will be using them again and again for practice.

AP European History

The College Board has provided practice questions for the exam , including a DBQ (see page 200 in the linked document).

If you've already seen this question, the only other questions available through the College Board are in the old format, because the 2016 DBQ is in a new, seven-point format identical to the AP US History exam. Just be sure to use the new DBQ rubric if you want to use any of the old prompts provided by the College Board . (DBQs are in the documents titled "Free-Response Questions.")

I advise you to save all these links (or even download all the Free Response Questions and the Scoring Guides) for reference, because you will be using them again and again for practice.

Who knows—maybe this will be one of your documents!

AP World History

For this exam, you'll be given a 15-minute reading period and 45 minutes of writing time . As for the other two history exams, the College Board has provided practice questions . See page 166 for the DBQ.

If you've already seen this question, the only other questions available through the College Board are in the old format, because the 2017 World History DBQ is in a new, seven-point format identical to the AP US History and AP European History exams. So be sure to use the new DBQ rubric if you want to use any of the old prompts provided by the College Board . (DBQs are in the documents titled "Free-Response Questions.")

Finding a Trusted Advisor to Look at Your Papers

A history teacher would be a great resource, but if they are not available to you in this capacity, here are some other ideas:

- An English teacher.

- Ask a librarian at your school or public library! If they can't help you, they may be able to direct you to resources who can.

- You could also ask a school guidance counselor to direct you to in-school resources you could use.

- A tutor. This is especially helpful if they are familiar with the test, although even if they aren't, they can still advise—the DBQ is mostly testing academic writing skills under pressure.

- Your parent(s)! Again, ideally your trusted advisor will be familiar with the AP, but if you have used your parents for writing help in the past they can also assist here.

- You might try an older friend who has already taken the exam and did well...although bear in mind that some people are better at doing than scoring and/or explaining!

Can I Prepare For My Baseline?

If you know nothing about the DBQ and you'd like to do a little basic familiarization before you establish your baseline, that's completely fine. There's no point in taking a practice exam if you are going to panic and muddle your way through it; it won't give a useful picture of your skills.

For a basic orientation, check out my article for a basic introduction to the DBQ including DBQ format.

If you want to look at one or two sample essays, see my article for a list of DBQ example essay resources . Keep in mind that you should use a fresh prompt you haven't seen to establish your baseline, though, so if you do look at samples don't use those prompts to set your baseline.

I would also check out this page about the various "task" words associated with AP essay questions . This page was created primarily for the AP European History Long Essay question, but the definitions are still useful for the DBQ on all the history exams, particularly since these are the definitions provided by the College Board.

Once you feel oriented, take your practice exam!

Don't worry if you don't do well on your first practice! That's what studying is for. The point of establishing a baseline is not to make you feel bad, but to empower you to focus your efforts on the areas you need to work on. Even if you need to work on all the areas, that is completely fine and doable! Every skill you need for the DBQ can be built .

In the following section, we'll go over these skills and how to build them for each exam.

You need a stronger foundation than this sand castle.

#2: Develop Foundational Skills

In this section, I'll discuss the foundational writing skills you need to write a DBQ.

I'll start with some general information on crafting an effective thesis , since this is a skill you will need for any DBQ exam (and for your entire academic life). Then, I'll go over outlining essays, with some sample outline ideas for the DBQ. After I'll touch on time management. Finally, I'll briefly discuss how to non-awkwardly integrate information from your documents into your writing.

It sounds like a lot, but not only are these skills vital to your academic career in general, you probably already have the basic building blocks to master them in your arsenal!

Writing An Effective Thesis

Writing a good thesis is a skill you will need to develop for all your DBQs, and for any essay you write, on the AP or otherwise.

Here are some general rules as to what makes a good thesis:

A good thesis does more than just restate the prompt.

Let's say our class prompt is: "Analyze the primary factors that led to the French Revolution."

Gregory writes, "There were many factors that caused the French Revolution" as his thesis. This is not an effective thesis. All it does is vaguely restate the prompt.

A good thesis makes a plausible claim that you can defend in an essay-length piece of writing.

Maybe Karen writes, "Marie Antoinette caused the French Revolution when she said ‘Let them eat cake' because it made people mad."

This is not an effective thesis, either. For one thing, Marie Antoinette never said that. More importantly, how are you going to write an entire essay on how one offhand comment by Marie Antoinette caused the entire Revolution? This is both implausible and overly simplistic.

A good thesis answers the question .

If LaToya writes, "The Reign of Terror led to the ultimate demise of the French Revolution and ultimately paved the way for Napoleon Bonaparte to seize control of France," she may be making a reasonable, defensible claim, but it doesn't answer the question, which is not about what happened after the Revolution, but what caused it!

A good thesis makes it clear where you are going in your essay.

Let's say Juan writes, "The French Revolution, while caused by a variety of political, social, and economic factors, was primarily incited by the emergence of the highly educated Bourgeois class." This thesis provides a mini-roadmap for the entire essay, laying out that Juan is going to discuss the political, social, and economic factors that led to the Revolution, in that order, and that he will argue that the members of the Bourgeois class were the ultimate inciters of the Revolution.

This is a great thesis! It answers the question, makes an overarching point, and provides a clear idea of what the writer is going to discuss in the essay.

To review: a good thesis makes a claim, responds to the prompt, and lays out what you will discuss in your essay.

If you feel like you have trouble telling the difference between a good thesis and a not-so-good one, here are a few resources you can consult:

This site from SUNY Empire has an exercise in choosing the best thesis from several options. It's meant for research papers, but the general rules as to what makes a good thesis apply.

About.com has another exercise in choosing thesis statements specifically for short essays. Note, however, that most of the correct answers here would be "good" thesis statements as opposed to "super" thesis statements.

- This guide from the University of Iowa provides some really helpful tips on writing a thesis for a history paper.

So how do you practice your thesis statement skills for the DBQ?

While you should definitely practice looking at DBQ questions and documents and writing a thesis in response to those, you may also find it useful to write some practice thesis statements in response to the Free-Response Questions. While you won't be taking any documents into account in your argument for the Free-Response Questions, it's good practice on how to construct an effective thesis in general.

You could even try writing multiple thesis statements in response to the same prompt! It is a great exercise to see how you could approach the prompt from different angles. Time yourself for 5-10 minutes to mimic the time pressure of the AP exam.

If possible, have a trusted advisor or friend look over your practice statements and give you feedback. Barring that, looking over the scoring guidelines for old prompts (accessible from the same page on the College Board where past free-response questions can be found) will provide you with useful tips on what might make a good thesis in response to a given prompt.

Once you can write a thesis, you need to be able to support it—that's where outlining comes in!

This is not a good outline.

Outlining and Formatting Your Essay

You may be the greatest document analyst and thesis-writer in the world, but if you don't know how to put it all together in a DBQ essay outline, you won't be able to write a cohesive, high-scoring essay on test day.

A good outline will clearly lay out your thesis and how you are going to support that thesis in your body paragraphs. It will keep your writing organized and prevent you from forgetting anything you want to mention!

For some general tips on writing outlines, this page from Roane State has some useful information. While the general principles of outlining an essay hold, the DBQ format is going to have its own unique outlining considerations.To that end, I've provided some brief sample outlines that will help you hit all the important points.

Sample DBQ Outline

- Introduction

- Thesis. The most important part of your intro!

- Body 1 - contextual information

- Any outside historical/contextual information

- Body 2 - First point

- Documents & analysis that support the first point

- If three body paragraphs: use about three documents, do deeper analysis on two

- Body 3 - Second point

- Documents & analysis that support the second point

- Use about three documents, do deeper analysis on two

- Be sure to mention your outside example if you have not done so yet!

- Body 4 (optional) - Third point

- Documents and analysis that support third point

- Re-state thesis

- Draw a comparison to another time period or situation (synthesis)

Depending on your number of body paragraphs and your main points, you may include different numbers of documents in each paragraph, or switch around where you place your contextual information, your outside example, or your synthesis.

There's no one right way to outline, just so long as each of your body paragraphs has a clear point that you support with documents, and you remember to do a deeper analysis on four documents, bring in outside historical information, and make a comparison to another historical situation or time (you will see these last points further explained in the rubric breakdown).

Of course, all the organizational skills in the world won't help you if you can't write your entire essay in the time allotted. The next section will cover time management skills.

You can be as organized as this library!

Time Management Skills for Essay Writing

Do you know all of your essay-writing skills, but just can't get a DBQ essay together in a 15-minute planning period and 40 minutes of writing?

There could be a few things at play here:

Do you find yourself spending a lot of time staring at a blank paper?

If you feel like you don't know where to start, spend one-two minutes brainstorming as soon as you read the question and the documents. Write anything here—don't censor yourself. No one will look at those notes but you!

After you've brainstormed for a bit, try to organize those thoughts into a thesis, and then into body paragraphs. It's better to start working and change things around than to waste time agonizing that you don't know the perfect thing to say.

Are you too anxious to start writing, or does anxiety distract you in the middle of your writing time? Do you just feel overwhelmed?

Sounds like test anxiety. Lots of people have this. (Including me! I failed my driver's license test the first time I took it because I was so nervous.)

You might talk to a guidance counselor about your anxiety. They will be able to provide advice and direct you to resources you can use.

There are also some valuable test anxiety resources online: try our guide to mindfulness (it's focused on the SAT, but the same concepts apply on any high-pressure test) and check out tips from Minnesota State University , these strategies from TeensHealth , or this plan for reducing anxiety from West Virginia University.

Are you only two thirds of the way through your essay when 40 minutes have passed?

You are probably spending too long on your outline, biting off more than you can chew, or both.

If you find yourself spending 20+ minutes outlining, you need to practice bringing down your outline time. Remember, an outline is just a guide for your essay—it is fine to switch things around as you are writing. It doesn't need to be perfect. To cut down on your outline time, practice just outlining for shorter and shorter time intervals. When you can write one in 20 minutes, bring it down to 18, then down to 16.

You may also be trying to cover too much in your paper. If you have five body paragraphs, you need to scale things back to three. If you are spending twenty minutes writing two paragraphs of contextual information, you need to trim it down to a few relevant sentences. Be mindful of where you are spending a lot of time, and target those areas.

You don't know the problem —you just can't get it done!

If you can't exactly pinpoint what's taking you so long, I advise you to simply practice writing DBQs in less and less time. Start with 20 minutes for your outline and 50 for your essay, (or longer, if you need). Then when you can do it in 20 and 50, move back to 18 minutes and 45 for writing, then to 15 and 40.

You absolutely can learn to manage your time effectively so that you can write a great DBQ in the time allotted. On to the next skill!

Integrating Citations

The final skill that isn't explicitly covered in the rubric, but will make a big difference in your essay quality, is integrating document citations into your essay. In other words, how do you reference the information in the documents in a clear, non-awkward way?

It is usually better to use the author or title of the document to identify a document instead of writing "Document A." So instead of writing "Document A describes the riot as...," you might say, "In Sven Svenson's description of the riot…"

When you quote a document directly without otherwise identifying it, you may want to include a parenthetical citation. For example, you might write, "The strikers were described as ‘valiant and true' by the working class citizens of the city (Document E)."

Now that we've reviewed the essential, foundational skills of the DBQ, I'll move into the rubric breakdowns. We'll discuss each skill the AP graders will be looking for when they score your exam. All of the history exams share a DBQ rubric, so the guidelines are identical.

Don't worry, you won't need a magnifying glass to examine the rubric.

#3: Learn the DBQ Rubric

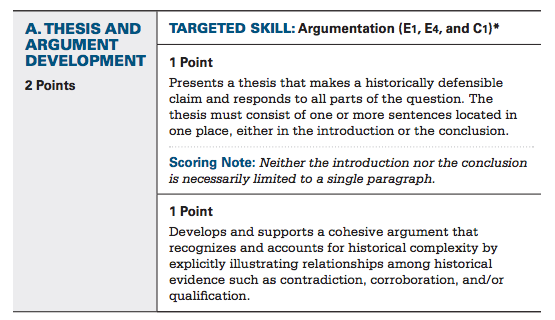

The DBQ rubric has four sections for a total of seven points.

Part A: Thesis - 2 Points

One point is for having a thesis that works and is historically defensible. This just means that your thesis can be reasonably supported by the documents and historical fact. So please don't make the main point of your essay that JFK was a member of the Illuminati or that Pope Urban II was an alien.

Per the College Board, your thesis needs to be located in your introduction or your conclusion. You've probably been taught to place your thesis in your intro, so stick with what you're used to. Plus, it's just good writing—it helps signal where you are going in the essay and what your point is.

You can receive another point for having a super thesis.

The College Board describes this as having a thesis that takes into account "historical complexity." Historical complexity is really just the idea that historical evidence does not always agree about everything, and that there are reasons for agreement, disagreement, etc.

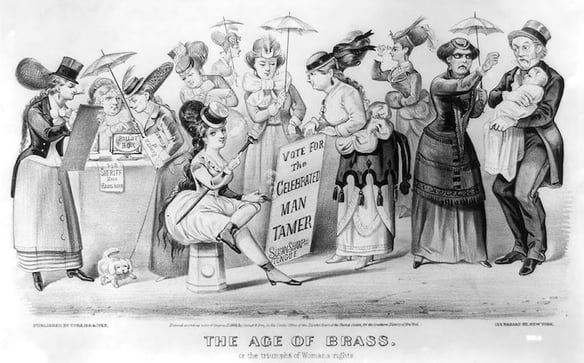

How will you know whether the historical evidence agrees or disagrees? The documents! Suppose you are responding to a prompt about women's suffrage (suffrage is the right to vote, for those of you who haven't gotten to that unit in class yet):

"Analyze the responses to the women's suffrage movement in the United States."

Included among your documents, you have a letter from a suffragette passionately explaining why she feels women should have the vote, a copy of a suffragette's speech at a women's meeting, a letter from one congressman to another debating the pros and cons of suffrage, and a political cartoon displaying the death of society and the end of the ‘natural' order at the hands of female voters.

A simple but effective thesis might be something like,

"Though ultimately successful, the women's suffrage movement sharply divided the country between those who believed women's suffrage was unnatural and those who believed it was an inherent right of women."

This is good: it answers the question and clearly states the two responses to suffrage that are going to be analyzed in the essay.

A super thesis , however, would take the relationships between the documents (and the people behind the documents!) into account.

It might be something like,

"The dramatic contrast between those who responded in favor of women's suffrage and those who fought against it revealed a fundamental rift in American society centered on the role of women—whether women were ‘naturally' meant to be socially and civilly subordinate to men, or whether they were in fact equals."

This is a "super" thesis because it gets into the specifics of the relationship between historical factors and shows the broader picture —that is, what responses to women's suffrage revealed about the role of women in the United States overall.

It goes beyond just analyzing the specific issues to a "so what"? It doesn't just take a position about history, it tells the reader why they should care . In this case, our super thesis tells us that the reader should care about women's suffrage because the issue reveals a fundamental conflict in America over the position of women in society.

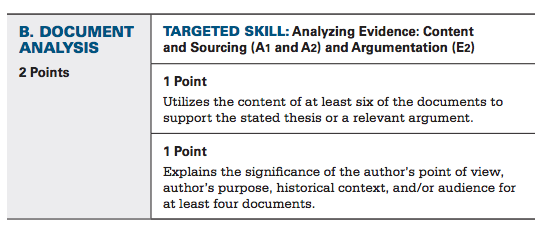

Part B: Document Analysis - 2 Points

One point for using six or seven of the documents in your essay to support your argument. Easy-peasy! However, make sure you aren't just summarizing documents in a list, but are tying them back to the main points of your paragraphs.

It's best to avoid writing things like, "Document A says X, and Document B says Y, and Document C says Z." Instead, you might write something like, "The anonymous author of Document C expresses his support and admiration for the suffragettes but also expresses fear that giving women the right to vote will lead to conflict in the home, highlighting the common fear that women's suffrage would lead to upheaval in women's traditional role in society."

Any summarizing should be connected a point. Essentially, any explanation of what a document says needs to be tied to a "so what?" If it's not clear to you why what you are writing about a document is related to your main point, it's not going to be clear to the AP grader.

You can get an additional point here for doing further analysis on 4 of the documents. This further analysis could be in any of these 4 areas:

Author's point of view - Why does the author think the way that they do? What is their position in society and how does this influence what they are saying?

Author's purpose - Why is the author writing what they are writing? What are they trying to convince their audience of?

Historical context - What broader historical facts are relevant to this document?

Audience - Who is the intended audience for this document? Who is the author addressing or trying to convince?

Be sure to tie any further analysis back to your main argument! And remember, you only have to do this for four documents for full credit, but it's fine to do it for more if you can.

Practicing Document Analysis

So how do you practice document analysis? By analyzing documents!

Luckily for AP test takers everywhere, New York State has an exam called the Regents Exam that has its own DBQ section. Before they write the essay, however, New York students have to answer short answer questions about the documents.

Answering Regents exam DBQ short-answer questions is good practice for basic document analysis. While most of the questions are pretty basic, it's a good warm-up in terms of thinking more deeply about the documents and how to use them. This set of Regent-style DBQs from the Teacher's Project are mostly about US History, but the practice could be good for other tests too.

This prompt from the Morningside center also has some good document comprehensions questions about a US-History based prompt.

Note: While the document short-answer questions are useful for thinking about basic document analysis, I wouldn't advise completing entire Regents exam DBQ essay prompts for practice, because the format and rubric are both somewhat different from the AP.

Your AP history textbook may also have documents with questions that you can use to practice. Flip around in there!

This otter is ready to swim in the waters of the DBQ.

When you want to do a deeper dive on the documents, you can also pull out those old College Board DBQ prompts.

Read the documents carefully. Write down everything that comes to your attention. Do further analysis—author's point of view, purpose, audience, and historical context—on all the documents for practice, even though you will only need to do additional analysis on four on test day. Of course, you might not be able to do all kinds of further analysis on things like maps and graphs, which is fine.

You might also try thinking about how you would arrange those observations in an argument, or even try writing a practice outline! This exercise would combine your thesis and document-analysis skills practice.

When you've analyzed everything you can possibly think of for all the documents, pull up the Scoring Guide for that prompt. It helpfully has an entire list of analysis points for each document.

Consider what they identified that you missed.

Do you seem way off-base in your interpretation? If so, how did it happen?

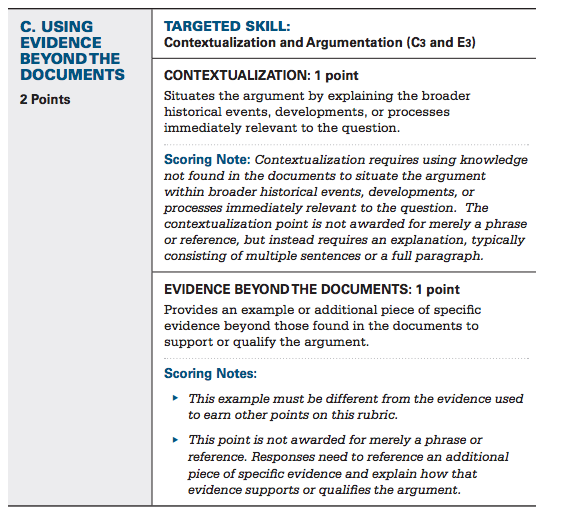

Part C: Using Evidence Beyond the Documents - 2 Points

Don't be freaked out by the fact that this is two points!

One point is just for context—if you can locate the issue within its broader historical situation. You do need to write several sentences to a paragraph about it, but don't stress; all you really need to know to be able to get this point is information about major historical trends over time, and you will need to know this anyways for the multiple choice section. If the question is about the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression, for example, be sure to include some of the general information you know about the Great Depression! Boom. Contextualized.

The other point is for naming a specific, relevant example in your essay that does not appear in the documents.

To practice your outside information skills, pull up your College Board prompts!

Read through the prompt and documents and then write down all of the contextualizing facts and as many specific examples as you can think of.

I advise timing yourself—maybe 5-10 minutes to read the documents and prompt and list your outside knowledge—to imitate the time pressure of the DBQ.

When you've exhausted your knowledge, make sure to fact-check your examples and your contextual information! You don't want to use incorrect information on test day.

If you can't remember any examples or contextual information about that topic, look some up! This will help fill in holes in your knowledge.

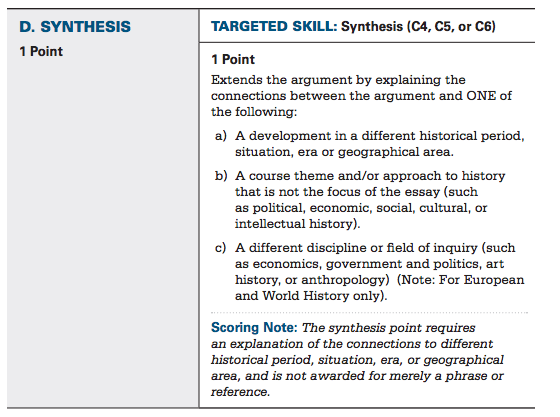

Part D: Synthesis - 1 Point

All you need to do for synthesis is relate your argument about this specific time period to a different time period, geographical area, historical movement, etc. It is probably easiest to do this in the conclusion of the essay. If your essay is about the Great Depression, you might relate it to the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

You do need to do more than just mention your synthesis connection. You need to make it meaningful. How are the two things you are comparing similar? What does one reveal about the other? Is there a key difference that highlights something important?

To practice your synthesis skills—you guessed it—pull up your College Board prompts!

- Read through the prompt and documents and then identify what historical connections you could make for your synthesis point. Be sure to write a few words on why the connection is significant!

- A great way to make sure that your synthesis connection makes sense is to explain it to someone else. If you explain what you think the connection is and they get it, you're probably on the right track.

- You can also look at sample responses and the scoring guide for the old prompts to see what other connections students and AP graders made.

That's a wrap on the rubric! Let's move on to skill-building strategy.

I know you're tired, but you can do it!

#5: Take Another Practice DBQ

So, you established a baseline, identified the skills you need to work on, and practiced writing a thesis statement and analyzing documents for hours. What now?

Take another timed, practice DBQ from a prompt you haven't seen before to check how you've improved. Recruit your same trusted advisor to grade your exam and give feedback. After, work on any skills that still need to be honed.

Repeat this process as necessary, until you are consistently scoring your goal score. Then you just need to make sure you maintain your skills until test day by doing an occasional practice DBQ.

Eventually, test day will come—read on for my DBQ-test-taking tips.

How Can I Succeed On DBQ Test Day?

Once you've prepped your brains out, you still have to take the test! I know, I know. But I've got some advice on how to make sure all of your hard work pays off on test day—both some general tips and some specific advice on how to write a DBQ.

#1: General Test-Taking Tips

Most of these are probably tips you've heard before, but they bear repeating:

Get a good night's sleep for the two nights preceding the exam. This will keep your memory sharp!

Eat a good breakfast (and lunch, if the exam is in the afternoon) before the exam with protein and whole grains. This will keep your blood sugar from crashing and making you tired during the exam.

Don't study the night before the exam if you can help it. Instead, do something relaxing. You've been preparing, and you will have an easier time on exam day if you aren't stressed from trying to cram the night before.

This dude knows he needs to get a good night's rest!

#2: DBQ Plan and Strategies

Below I've laid out how to use your time during the DBQ exam. I'll provide tips on reading the question and docs, planning your essay, and writing!

Be sure to keep an eye on the clock throughout so you can track your general progress.

Reading the Question and the Documents: 5-6 min

First thing's first: r ead the question carefully , two or even three times. You may want to circle the task words ("analyze," "describe," "evaluate," "compare") to make sure they stand out.

You could also quickly jot down some contextual information you already know before moving on to the documents, but if you can't remember any right then, move on to the docs and let them jog your memory.

It's fine to have a general idea of a thesis after you read the question, but if you don't, move on to the docs and let them guide you in the right direction.

Next, move on to the documents. Mark them as you read—circle things that seem important, jot thoughts and notes in the margins.

After you've passed over the documents once, you should choose the four documents you are going to analyze more deeply and read them again. You probably won't be analyzing the author's purpose for sources like maps and charts. Good choices are documents in which the author's social or political position and stake in the issue at hand are clear.

Get ready to go down the document rabbit hole.

Planning Your Essay: 9-11 min

Once you've read the question and you have preliminary notes on the documents, it's time to start working on a thesis. If you still aren't sure what to talk about, spend a minute or so brainstorming. Write down themes and concepts that seem important and create a thesis from those. Remember, your thesis needs to answer the question and make a claim!

When you've got a thesis, it's time to work on an outline . Once you've got some appropriate topics for your body paragraphs, use your notes on the documents to populate your outline. Which documents support which ideas? You don't need to use every little thought you had about the document when you read it, but you should be sure to use every document.

Here's three things to make sure of:

Make sure your outline notes where you are going to include your contextual information (often placed in the first body paragraph, but this is up to you), your specific example (likely in one of the body paragraphs), and your synthesis (the conclusion is a good place for this).

Make sure you've also integrated the four documents you are going to further analyze and how to analyze them.

Make sure you use all the documents! I can't stress this enough. Take a quick pass over your outline and the docs and make sure all of the docs appear in your outline.

If you go over the planning time a couple of minutes, it's not the end of the world. This probably just means you have a really thorough outline! But be ready to write pretty fast.

Writing the Essay - 45 min

If you have a good outline, the hard part is out of the way! You just need to make sure you get all of your great ideas down in the test booklet.

Don't get too bogged down in writing a super-exciting introduction. You won't get points for it, so trying to be fancy will just waste time. Spend maybe one or two sentences introducing the issue, then get right to your thesis.

For your body paragraphs, make sure your topic sentences clearly state the point of the paragraph . Then you can get right into your evidence and your document analysis.

As you write, make sure to keep an eye on the time. You want to be a little more than halfway through at the 20-minute mark of the writing period, so you have a couple minutes to go back and edit your essay at the end.

Keep in mind that it's more important to clearly lay out your argument than to use flowery language. Sentences that are shorter and to the point are completely fine.

If you are short on time, the conclusion is the least important part of your essay . Even just one sentence to wrap things up is fine just so long as you've hit all the points you need to (i.e. don't skip your conclusion if you still need to put in your synthesis example).

When you are done, make one last past through your essay. Make sure you included everything that was in your outline and hit all the rubric skills! Then take a deep breath and pat yourself on the back.

You did it!! Have a cupcake to celebrate.

Key Tips for How to Write a DBQ

I realize I've bombarded you with information, so here are the key points to take away:

Remember the drill for prep: establish a baseline, build skills, take another practice DBQ, repeat skill-building as necessary.

Make sure that you know the rubric inside and out so you will remember to hit all the necessary points on test day! It's easy to lose points just for forgetting something like your synthesis point.

On test day, keep yourself on track time-wise !

This may seem like a lot, but you can learn how to ace your DBQ! With a combination of preparation and good test-taking strategy, you will get the score you're aiming for. The more you practice, the more natural it will seem, until every DBQ is a breeze.

What's Next?

If you want more information about the DBQ, see my introductory guide to the DBQ .

Haven't registered for your AP test yet? See our article for help registering for AP exams .

For more on studying for the AP US History exam, check out the best AP US History notes to study with .

Studying for World History? See these AP World History study tips from one of our experts.

Ellen has extensive education mentorship experience and is deeply committed to helping students succeed in all areas of life. She received a BA from Harvard in Folklore and Mythology and is currently pursuing graduate studies at Columbia University.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Find what you need to study

AP World Document-Based Question (DBQ) Overview

19 min read • november 18, 2021

Melissa Longnecker

Mixed AP Review

Endless stimulus-based MCQs for all units

Overview of the Document-Based Question (DBQ)

The one thing you need to know about this question:

Section II of the AP Exam includes the one required Document-Based Question (DBQ.) Unlike the other free-response sections (SAQ and LEQ), there isn’t any choice in what you write about for this essay.

You will be given a prompt and a set of seven documents to help you respond to the prompt. The documents will represent various perspectives relating to the prompt, and they will always include a mixture of primary source text documents and primary or secondary source visuals . Your task is to use these documents, and your knowledge of history, to answer the prompt.

The DBQ is designed to test your knowledge of history, your ability to analyze a variety of sources, and your skill in crafting and supporting a clear and complex argument. It is the single most complicated task on the exam; however, it is very doable with practice and preparation.

Your answer should include the following:

A valid thesis

A discussion of relevant historical context

Use of evidence from the documents (all) and evidence not found in the documents to support your thesis

A discussion of relevant factors that affect the document

Complex understanding of the topic of the prompt.

We will break down each of these aspects in the next section. For now, the gist is that you need to write an essay that answers the prompt, using the documents and your knowledge as evidence. You will also need to discuss some additional factors that impact your use of the documents.

Many of the skills you need to write a successful DBQ essay are the same skills you will use on the LEQ. In fact, some of the rubric points are identical, so you can use a lot of the same strategies on both writing tasks!

The topic of your DBQ will come from the following time periods, depending on your course:

AP World History: Modern - 1200-1900

AP US History - 1754-1980

AP European History - 1600-2001

The writing time on the AP Exam includes both the DBQ and the Long Essay Question (LEQ), but it is suggested that you spend 60 minutes completing the DBQ. You will need to read and analyze the documents and write your essay in that time.

A good breakdown would be: 15 min. (reading & analysis) + 45 min. (writing) = 60 min.

The DBQ is scored on a rubric out of seven points and is weighted at 25% of your overall exam score. We’ll break down the rubric next.

The DBQ is scored on a seven-point rubric, and each point can be earned independently. That means you can miss a point on something and still earn other points with the great parts of your essay.

Let’s break down each rubric component...

The thesis is a brief statement that introduces your argument or claim and can be supported with evidence and analysis. This is where you answer the prompt.

This is the only element in the essay that has a required location. The thesis needs to be in your introduction or conclusion of your essay. It can be more than one sentence, but all of the sentences that make up your thesis must be consecutive in order to count.

The most important part of your thesis is the claim , which is your answer to the prompt. The description the College-Board gives is that it should be “historically defensible,” which really means that your evidence must be plausible. On the DBQ, your thesis needs to be related to information from the documents, as well as connected to the topic of the prompt.

Your thesis should also establish your line of reasoning. Translation: address why or how something happened - think of this as the “because” to the implied “how/why” of the prompt. This sets up the framework for the body of your essay since you can use the reasoning from your thesis to structure your body paragraph topics later.

The claim and reasoning are the required elements of the thesis. And if that’s all you can do, it will earn you the point.

Going above-and-beyond to create a more complex thesis can help you in the long run, so it’s worth your time to try. One way to build in complexity to your thesis is to think about a counter-claim or alternate viewpoint that is relevant to your response. If you are thinking about using one of the course reasoning processes to structure your essay (and you should!) think about using that framework for your thesis too.

In a causation essay, a complex argument addresses causes and effects .

In a comparison essay, a complex argument addresses similarities and differences.

In a continuity and change over time essay, a complex argument addresses change and continuity.

This counterclaim or alternate viewpoint can look like an “although” or “however” phrase in your thesis.

Sample complex thesis: While some cultural traditions and belief systems, such as Confucianism, actively warned against the accumulation of wealth through trade, other societies reliant on trade used their belief systems to rationalize the behavior of merchants despite moral concerns. Still, others used religion as a means to promote trade and the activities of merchants.

👉🏾 Watch Patrick Lasseter break down the thesis and craft this sample here!

Contextualization

Contextualization is a brief statement that lays out the broader historical background relevant to the prompt.

There are a lot of good metaphors out there for contextualization, including the “previously on…” at the beginning of some TV shows, or the famous text crawl at the beginning of the Star Wars movies.

Both of these examples serve the same function: they give important information about what has happened off-screen that the audience needs to know to understand what is about to happen on-screen.

In your essay, contextualization is the same. You give your reader information about what else has happened, or is happening, in history that will help them understand the specific topic and argument you are about to make.

There is no specific requirement for where contextualization must appear in your essay. The easiest place to include it, however, is in your introduction . Use context to get your reader acquainted with the time, place, and theme of your essay, then transition into your thesis.

Good contextualization doesn’t have to be long, and it doesn’t have to go into a ton of detail, but it does need to do a few very specific things.

Your contextualization needs to refer to events, developments and/or processes outside the time and place of the prompt. It could address something that occurred in an earlier era in the same region as the topic of the prompt, or it could address something happening at the same time as the prompt, but in a different place. Briefly describe this outside information.

Then, connect it to your thesis/argument. The language from the College Board is that contextualization must be “relevant to the prompt,” and in practical terms; this means you have to show the connection. A transition sentence or phrase is useful here (plus, this is why contextualization makes the most sense in the introduction!).

Also, contextualization needs to be multiple consecutive sentences, so it’s all one argument (not sprinkled around in a paragraph). The introduction is the best place for contextualization, but not the only place.

Basically, choose a connected topic that “sets the stage” for your thesis, and briefly describe it in a couple of sentences. Then, make a clear connection to the argument of your thesis from that outside information.

Sample contextualization: The period 1200-1600 saw the growth of centralized empires such as the Song in China or the Ottoman Empire. These empires promoted trade and growth as state policy, and this economic growth created new economic elites. In response to this change, religious leaders, thinkers, and scholars weighed in to promote, criticize, or simply comment on the moral aspects of trade and economic growth.

👉🏾 Watch Evan Liddle break down contextualization and write an example here!

Evidence is the historical detail, the specific facts, and examples that prove your argument. In the DBQ, your evidence comes from two places: the documents themselves, and your outside knowledge of history. You should plan to use all seven documents as evidence AND bring in your knowledge on top of that.

Having evidence is important, and one of the rubric points on the DBQ is just about having evidence. Of course, it’s not enough just to know the facts. You also need to use those facts to support your argument/claim/thesis, and the other two possible rubric points for evidence on the DBQ are about using the evidence you have to support what you’re trying to say.

Evidence goes in your body paragraphs. In fact, the bulk of your body paragraphs will be made up of evidence and supporting analysis or commentary that connects that evidence to other evidence and/or to the argument you are making.

Good evidence is specific, accurate, and relevant to the prompt.

Don’t simply summarize the documents. Use a specific idea or argument from the document as your evidence.

Evidence from the documents should come directly from part or all of a document, ideally without quoting.

Paraphrasing allows you to transition directly into your argument without all the work of embedding a quote like you might for an English essay. Take a specific idea from the document, phrase it in your own words, and use it in support of your argument.

You earn a point of using evidence from at least three of the documents. There’s an additional point up for grabs for using evidence from at least six documents and supporting your argument with that evidence, which means you should always link your evidence back to your topic sentence or thesis.

Example: Ibn Khaldun observed that trade benefitted merchants at the expense of their customers, and he feared that participating in trade, though legal under Islamic law, would weaken the moral integrity of merchants.

Evidence from your outside knowledge is much the same, except that you won’t have a document to structure it for you. Describe a specific example of something you know that is relevant to the prompt, and use it to support your argument. Using course-specific vocabulary is a great strategy here to know that you are writing specific evidence.

Example: Muhammad himself was a merchant before becoming the Prophet of Islam, which accounts for the support of merchants and trade by Muslim societies.

👉🏾 Watch Caroline Castellanos break down the sample DBQ and pull out key pieces of evidence here.

Analysis and Reasoning: Sourcing

What is it? For at least three of the documents, you need to analyze the source of the document as well as the content. There are four acceptable categories of sourcing analysis:

Historical situation - this is like a miniature version of contextualization. Ask: when/where was this document created? How does that historical situation influence what the document is or what it says?

Intended audience - every document was created with an audience in mind. A document created for a king will likely be very different from a document created for a lover. Ask: for whom was this document created? How would that person have understood it? What did they know or understand that the creator could leave unsaid? What did they need to be explained?

Point of view - every document was created by someone, and that person has specific knowledge, opinions, and limitations that impact what they create. Ask: who created this document? How well did they understand the topic of the document? What would limit their understanding or reliability on this topic? What characteristics might influence them (race, gender, age, religion, status, etc.)

Purpose - all documents were created for a reason. Figure out the reason and understand why a document says or shows what it does. Ask: why was this document created, and how does that impact what it is?

Any of these characteristics will have an impact on how you use a document to support your argument. Sometimes a characteristic will weaken a document’s reliability. Sometimes a characteristic will strengthen a document’s usefulness. In addition to describing the relevant characteristic of a document, you should also explain how or why it impacts your argument.

Where do I write it? You should connect sourcing directly to your discussion of evidence from a particular document. This will occur throughout your body paragraphs.

How do I know if mine is good? Your sourcing should describe a relevant characteristic of the document and explain why/how that characteristic is relevant to your argument.

Sample sourcing statement: As a Muslim scholar, Ibn Khaldun would have had a deep understanding of religious laws, but perhaps limited knowledge of common trade practices in his day and culture. This could factor into his low view of the morality of merchants, whom he saw as less moral than someone devoting their life to their faith.

The second part of the Analysis and Reasoning scoring category is complexity. This is by far the most challenging part of the DBQ, and the point earned by the fewest students. It isn’t impossible, just difficult. Part of the difficulty comes in that it is the least concrete skill to teach and practice.

If you’re already feeling overwhelmed by the magnitude of the DBQ, don’t stress about complexity. Focus on writing the best essay you can that answers the prompt. Plenty of students earn 5’s without the complexity point.

If you are ready to tackle this challenge, keep reading!

The College Board awards this point for essays that “demonstrate a complex understanding” of the topic of the prompt.

Complexity cannot be earned with a single sentence or phrase. It must show up throughout the essay.

A complex argument starts with a complex thesis. A complex thesis must address the topic of the prompt in more than one way. Including a counter-claim or alternate viewpoint in the thesis is a good way to set up a complex argument because it builds in room within the structure of your essay to address more than one idea (provided your body paragraphs follow the structure of your thesis!)

A complex argument may include corroboration - evidence that supports or confirms the premise of the argument. A clear explanation that connects each piece of evidence to the thesis will help do this. In the DBQ, documents may also corroborate or support one another, so you could also include evidence that shows how documents relate to one another.

A complex argument may also include qualification - evidence that limits or counters an initial claim. This isn’t the same as undoing or undermining your claim. Qualifying a claim shows that it isn’t universal. An example of this might be including continuity in an essay that is primarily about change.

A final way to introduce complexity to your argument is through modification - using evidence to change your claim or argument as it develops. Modification isn’t quite as extreme as qualification, but it shows that the initial claim may be too simple to encompass the reality of history.

Since no single sentence can demonstrate complexity on its own, it’s difficult to show examples of complex arguments. Fully discussing your claim and its line of reasoning, and fairly addressing your counterclaim or alternate view is the strongest structure to aim for a complexity point!

Watch Melissa Longnecker break down documents and describe Analysis and Reasoning here.

Understanding the Process of Writing a DBQ

Before you start writing....

Because the DBQ has so many different components, your prep work before writing is critical. Don’t feel like you have to start writing right away. You are allotted a 15 min. “reading period” as part of your DBQ time - you should use it!

The very first thing you should do with any prompt is to be sure you understand the question . Misunderstanding the time period, topic, or geographic region of a prompt can kill a thoughtful and well-argued essay. When you’re practicing early in the year, go ahead and rewrite the prompt as a question. Later on, you can re-phrase it mentally without all the work.

As you think about the question, start thinking about which reasoning skill might apply best for this prompt: causation, comparison, or continuity and change over time. You don’t necessarily have to choose one of these skills to organize your writing, but it’s a good starting place if you’re feeling stuck.

Original prompt : Evaluate the extent to which cultural traditions or belief systems affected attitudes toward merchants and trade in the period 1200-1600.

Revised : How much did religion and culture impact attitudes about merchants/trade 1200-1600?

Once you know what to write about, take one minute to brainstorm what you already know about this time period and topic. This will help you start thinking about contextualization and outside knowledge as you read the documents.

Now it’s time to read the documents . As you read, pay attention to the source line that introduces the author, date, etc. about each document. It should contain information that will help you with your sourcing analysis. Mark this info with a symbol that is relevant for you, such as H for the historical situation, I for the intended audience, etc.

If the source line doesn’t give you much, it’s ok to skip sourcing for some of the documents. Try to analyze each one though, since you have to choose at least three to write about sourcing in your essay.

Read the document for content next. Think about what the document is saying or showing. Summarize it briefly in the margin or in your head and note how it connects to the prompt and to other documents in the set.

Example (download modified DBQ prompts here ):

Documents that reject merchants on moral grounds: 2, 3, (4?)

Confucianism = mistrust of merchants: 2, 7

Documents that permit trade, despite dishonesty of merchants: 4, 6 Documents that see wealth a religious blessing: 1, 5

Islam = support of trade as a custom: 4, 6

Rationalizing/compromising morals in areas that rely on trade: 1, 4, 5, 6

Note: you wouldn’t use all of these groupings in one essay. This list shows a sample of different ways the documents might connect to build a thesis and structure an essay. The three bolded notations here correspond to the topics selected for the sample thesis.

After reading all of the documents, take a minute to organize your thinking and plan your thesis. Decide which documents fit best to support the topics of your body paragraphs and choose your three or more documents for sourcing analysis.

Once you have a plan you like, start writing!

How to Write The DBQ

Your introduction should include your contextualization and thesis. Start with a statement that establishes your time and place in history, and follow that with a brief description of the historical situation. Connect that broader context to the theme

and topic of the prompt. Then, make a claim that answers the prompt, with an overview of your reasoning and any counterclaim you plan to address.

Body paragraphs will vary in length, depending on how many documents or other pieces of evidence you include, but should follow a consistent structure. Start with a topic sentence that introduces the specific aspect of the prompt that paragraph will address. There aren’t specific points for topic sentences, but they will help you stay focused.

Follow your topic sentence with a piece of evidence from one of the documents. This should be paraphrased in your own words, and you should explain how that evidence specifically supports your argument.

After 1-2 sentences of evidence, make an argument about sourcing . This is where you explain the specific characteristic and how it impacts your argument (“because...” or “in order to…” are good phrases here.)

Follow the sourcing with additional pieces of evidence, sourcing, and explanation. Ideally, you would do this with 2-3 documents relating to one topic sentence per paragraph. Somewhere in your body paragraph, you should also introduce a piece of outside evidence and connect it back to your topic sentence as well.

Each body paragraph will follow this general format, and there are no set number of paragraphs for the DBQ (minimum or maximum.) Write as many paragraphs as you need to both use all seven documents and fully answer the prompt by developing the argument (and counter-argument if applicable) from your thesis.

If you have time, you may choose to write a conclusion . It isn’t necessary, so you can drop it if you’re rushed. BUT, the conclusion is the only place where you can earn the thesis point outside the introduction, so it’s not a bad idea. You could re-state your thesis with different words, or give any final thoughts in terms of analysis about your topic. You might solidify your complexity point in the conclusion if written well.

When you finish, it’s time to write the Long Essay Question (if you haven’t already), so turn the page in your prompt booklet and keep going!

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

6 APUSH DBQ Examples to Review

Every subject is easier to study using concrete examples; APUSH essays are no exception. The data-based question, or DBQ, differs from typical essays in only one way – the inclusion of five to seven historical documents. Your goal is to read through each historical document, then write an essay that clearly answers the given prompt while demonstrating your overall understanding of APUSH content. The following sources for APUSH DBQ examples are helpful to review before beginning your own writing .

What should I look in each APUSH DBQ sample?

In each sample, study how each author:

- formulates a thesis

- constructs an argument

- analyzes historical documents

- provides additional examples

- uses evidence to support argument

- synthesizes information

APUSH DBQ Example #1: AP College Board

College Board is always the best source for up-to-date information and resources. This APUSH DBQ sample is from 2016 , but provides three different variations of student responses. You can see how and why which writing sample scored best, as well as determine how to incorporate those elements into your own writing. ( Examples from 2015 are also available.)

APUSH DBQ Example #2: AP US History Notes

Although this site doesn’t explain why each sample is successful, it does offer a large selection of examples to choose from. You can get a good sense of what type of writing goes into a high-quality essay. Read through both the DBQ and long essay examples.

APUSH DBQ Example #3: Kaplan Test Prep

Kaplan only provides one APUSH DBQ sample , but does go through the essay point by point, explaining how the author develops a well-supported argument. Another good view into the inner workings of a quality writing example.

APUSH DBQ Example #4: Khan Academy

If you haven’t already, visit Khan Academy. Khan’s Historian’s Toolkit is a four-part video series that not only explains how to approach the DBQ, but also deconstructs the thinking behind a question example. Definitely worth a look.

APUSH DBQ Example #5: Apprend

Although rather lengthy, the DBQ and rubric breakdown from Apprend is a comprehensive look into how a DBQ response can earn top points and why. Options are given for each step of the writing process, enabling you to see the best possible answer for all sections of the essay.

APUSH DBQ Example #6: Your Classroom

Looking for more examples? One of the easiest places to find APUSH DBQ samples is in your own classroom. Ask your current APUSH teacher to view previous students’ writing samples. As you know by now, reviewing other students’ work can be a very powerful and effective way to study for DBQ.

Beth is an educator and freelance creative designer who devises innovative and fun-loving solutions for clients. She works with families, students, teachers and small businesses to create and implement programs, campaigns and experiences that help support and maximize efforts to grow communities who critically think, engage and continue to learn.

View all posts

More from Magoosh

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

AP® US History

Ensuring your students earn the contextualization point on the dbq.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

The redesign has brought a great deal of uncertainty and confusion amongst APUSH teachers. In many ways, we are all “rookie” teachers, as all of us have the challenge of implementing fundamental curricular and skills-based changes into our classrooms.

One of the more significant changes is to the structure of one essay on the AP® exam, the Document Based question (DBQ). The rubric for the DBQ was previously a more holistic essay that combined a strong thesis, and use of documents and outside information to support the argument. This has been transformed into a much more structured and formulaic skills-based rubric. The change has led to a healthy debate about the pros and cons of both types of essays, but in general the core of the essay has remained the same: write a thesis and support it with evidence in the form of documents and outside information. If students continue to apply these basic writing skills, they are likely to earn 3 or 4 out of the seven total points for the Document Based Question .

In this post, we will explore one of these points students will be looking to earn to help their chances at passing the APUSH exam this May: the Contextualization point.

What is Contextualization?

According to the College Board, contextualization refers to a:

Historical thinking skill that involves the ability to connect historical events and processes to specific circumstances of time and place as well as broader regional, national, or global processes. ( College Board AP® Course and Exam Description, AP® US History, Fall 2015 )

Contextualization is a critical historical thinking skill that is featured in the newly redesigned course. In my opinion, this is a skill of fundamental importance for students to utilize in the classroom. Often times, students find history difficult or boring because they don’t see connections between different historical time periods and the world they live in today. They assume that events occur in a vacuum, and don’t realize that the historical context is critical in helping explain people’s beliefs and points of view in that period of time. Putting events into context is something I always thought was important, but now that the College Board explicitly has established the skill, it has forced me to be more proactive in creating lessons and assignments that allow students to utilize this way of thinking.

The place that contextualization is most directly relevant on the actual AP® exam itself is the Document Based Question. In order to earn the point for contextualization, students must:

Situate historical events, developments, or processes within the broader regional, national, or global context in which they occurred in order to draw conclusions about their relative significance. (College Board AP® Course and Exam Description, AP® US History, Fall 2015)

In other words, students are asked to provide background before jumping right into their thesis and essay and paint a picture of what is going on at the time of the prompt. Although there is no specific requirement as to where contextualization should occur, it makes natural sense to place it in the introduction right before a thesis point. Placing this historical background right at the beginning sets the stage for the argument that will occur in the body of the essay, and is consistent with expectations many English teachers have in how to write an introduction paragraph.

I explain contextualization to students by using the example of Star Wars. Before the movie starts, the film begins with “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” and continues with background information on the characters, events, and other information that is crucial to understanding the film. Without this context, the viewer would not know what is going on, and might miss key events or be lost throughout the film. This is what contextualization aims to do in student essays. It sets the stage for their thesis, evidence, and argument that is to follow.

Contextualization vs. Historical Context

One aspect of the DBQ rubric that can be a bit confusing initially is that students are asked to do this contextualization, but there is also another area which gives them the option to use historical context. So what is the difference?

Contextualization refers to putting the entire essay into a broader context (preferably in the introduction). However, when writing their essays, students are also required to analyze four of the documents that they utilize by either examining the author’s point of view, describing the intended audience of the source, identifying the author’s purpose or putting the source into historical context. The latter sounds similar to contextualization (and it is essentially the same skill), but historical context is only focused on the specific document being analyzed, not the entire essay, like the contextualization point. For example, if a document is a map that shows slavery growing dramatically from 1820 to 1860, a student might point out that this growth can be explained in the context of the development of the cotton gin, which made the production of cotton much more profitable and let to the spread of slavery in the Deep South. While essentially the same skill, historical context focuses on one specific document’s background.

Examples of Successful Student Contextualization Points

One of the biggest pitfalls that prevent students from earning the contextualization point is that they are too brief or vague. In general, it would be difficult for students to earn the point if they are writing only a sentence or two. Early in the year, I assigned students a DBQ based on the following prompt:

Evaluate the extent in which the Civil War was a turning point in the lives of African Americans in the United States. Use the documents and your knowledge of the years 1860-1877 to construct your response.

This was the third DBQ we had written, and students were now getting brave enough to move beyond a thesis and document analysis and started attempting to tackle the contextualization point. However, the attempts were all over the map. One student wrote:

The Civil War was a bloody event that led to the death of thousands of Americans.

Of course this is a true statement, but is extremely vague. What led to the Civil War? Why was it so deadly? Without any specific detail, this student could not earn the contextualization point.

Another student wrote:

Slavery had existed for hundreds of years in the United States. It was a terrible thing that had to be abolished.

Again, this is a drive-by attempt at earning contextualization. It mentions things that are true, but lacks any meaningful details or explanation that would demonstrate understanding of the time period in discussion. What led to the beginning of slavery in the colonies? How did it develop? What made it so horrible? How did individuals resist and protest slavery? These are the types of details that would add meaning to contextualization.

One student nailed it. She wrote:

The peculiar institution of slavery had been a part of America’s identity since the founding of the original English colony at Jamestown. In the early years, compromise was key to avoiding the moral question, but as America entered the mid 19th century sectional tensions and crises with popular sovereignty, Kansas, and fugitive slaves made the issue increasingly unavoidable. When the Civil War began, the war was transformed from one to simply save the Union to a battle for the future of slavery and freedom in the United States.

Now THAT is contextualization! It gives specific details about the beginning of slavery and its development. It discusses attempts at compromise, but increasing sectional tensions that led to the Civil War. The writer paints a vivid and clear picture of the situation, events, and people that set the stage for the Civil War. Students don’t want to write a 6-8 sentence paragraph (they will want to save time for their argument in the body), but they need to do more than write a vague sentence that superficially addresses the era.

Strategies for Teaching Contextualization to Students

Analyze Lots of Primary Sources One of the best ways to prepare for the DBQ is for students to practice reading and comprehending primary source texts, particularly texts that are written by people who use very different language and sentence structure from today. This helps them understand and analyze documents, but it also can be helpful in practicing contextualization. Looking at different perspectives and points of view in the actual historical time periods they are learning is key in allowing students to understand how the era can impact beliefs, values and events that occur.

Assign Many DBQ Assessments and Share Specific Examples The more often students write DBQs, the more comfortable students will get with the entire process and skill set involved, including contextualization. One thing that has been especially successful in my classroom is to collect a handful of student attempts at the contextualization point and share them with students. Students then get to examine them and look at effective and less effective attempts at earning contextualization. Often the best way for students to learn what to do or how to improve is to see what their classmates have done.

Incorporating In-Class Activities The course is broken into nine distinct time periods from 1491 to present. In each period or unit students are assigned activities that force them to put a specific policy, event, or movement into context. For example, we did lecture notes on the presidency of JFK, learning about the Man on the Moon Speech, Cuban Missile Crisis, and creation of the Peace Corps. Students had to write 3-4 sentences that asked them to put these events in historical context using the Cold War. This allowed students to understand that each of these seemingly unrelated historical events were shaped by the tension between the United States and Soviet Union: winning the space race, stopping a communist nuclear threat less than 100 miles from Florida, and spreading goodwill into nations that might otherwise turn to communism all are strategies the United States used to thwart the Soviet threat. By doing this activity, students gain an appreciation for how historical context shapes events and decisions of the day.

Teach Cause and Effect in United States History It is very easy to get caught up as a teacher in how to best get lots of minutia and factoids into students heads quickly and efficiently. However, if we can teach history not as a series of independent and unrelated events, but as a series of events that have a causal relationship that impact what happens next, this helps students grasp and understand contextualization. For example, in the lead-up to World War I, students create a timeline of events that led to America entering the conflict. As students examine the torpedoing of the Lusitania, unrestricted submarine warfare, the Zimmermann telegram, etc., they gain an understanding that it was not a random decision by President Wilson, but rather a series of events that precipitated the declaration of war. This is what contextualization is: the background that sets the stage for a particular moment in American history.

Examine Contextualization with Current Events I know what you are thinking, I have one school year (less if your school year starts in September) to get through 1491 to Present and now I am supposed to make this a current events class as well? The answer is yes and no. Will stuff from the news pages be content the students need to know for the exam: absolutely not. However, it is a great opportunity for students to understand that our past explains why our country is what it is today.

For example, President Obama’s decision to work towards normalizing relations with Cuba makes more sense if students think about it through the lens of contextualization. The United States invaded Cuba in 1898 in the Spanish-American War and set up a protectorate. Cubans, upset with what they perceived as U.S. meddling and intervention led a communist revolution in 1959, ousting the American-backed government and setting the stage for one of the scariest moments in the Cold War : the Cuban Missile Crisis. Looking at how the past shapes current events today helps students understand this skill, and it also helps them gain a deeper appreciation of how important history is in shaping the world around them.