Selecting a Research Topic: Overview

- Refine your topic

- Background information & facts

- Writing help

Here are some resources to refer to when selecting a topic and preparing to write a paper:

- MIT Writing and Communication Center "Providing free professional advice about all types of writing and speaking to all members of the MIT community."

- Search Our Collections Find books about writing. Search by subject for: english language grammar; report writing handbooks; technical writing handbooks

- Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation Online version of the book that provides examples and tips on grammar, punctuation, capitalization, and other writing rules.

- Select a topic

Choosing an interesting research topic is your first challenge. Here are some tips:

- Choose a topic that you are interested in! The research process is more relevant if you care about your topic.

- If your topic is too broad, you will find too much information and not be able to focus.

- Background reading can help you choose and limit the scope of your topic.

- Review the guidelines on topic selection outlined in your assignment. Ask your professor or TA for suggestions.

- Refer to lecture notes and required texts to refresh your knowledge of the course and assignment.

- Talk about research ideas with a friend. S/he may be able to help focus your topic by discussing issues that didn't occur to you at first.

- WHY did you choose the topic? What interests you about it? Do you have an opinion about the issues involved?

- WHO are the information providers on this topic? Who might publish information about it? Who is affected by the topic? Do you know of organizations or institutions affiliated with the topic?

- WHAT are the major questions for this topic? Is there a debate about the topic? Are there a range of issues and viewpoints to consider?

- WHERE is your topic important: at the local, national or international level? Are there specific places affected by the topic?

- WHEN is/was your topic important? Is it a current event or an historical issue? Do you want to compare your topic by time periods?

Table of contents

- Broaden your topic

- Information Navigator home

- Sources for facts - general

- Sources for facts - specific subjects

Start here for help

Ask Us Ask a question, make an appointment, give feedback, or visit us.

- Next: Refine your topic >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2021 2:50 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mit.edu/select-topic

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

VII. Researched Writing

7.1 Developing a Research Question

Emilie Zickel and Terri Pantuso

I write out of ignorance. I write about the things I don’t have any resolutions for, and when I’m finished, I think I know a little bit more about it. I don’t write out of what I know. It’s what I don’t know that stimulates me . I merely know enough to get started. —Toni Morrison [1]

Think of a research paper as an opportunity to deepen (or create) knowledge about a topic that matters to you. Just as Toni Morrison states that she is stimulated by what she doesn’t yet know, a research paper assignment can be interesting and meaningful if it allows you to explore what you don’t know.

Research, at its best, is an act of knowledge creation, not just an extended book report. This knowledge creation is the essence of any great educational experience. Instead of just listening to lectures, you get to design the learning project that will ultimately result in you experiencing, and then expressing, your own intellectual growth. You get to read what you choose, thereby becoming an expert on your topic.

That sounds, perhaps, like a lofty goal. But by spending some quality time brainstorming, reading, thinking or otherwise tuning into what matters to you, you can end up with a workable research topic that will lead you on an enjoyable research journey.

The best research topics are meaningful to you; therefore, you should:

- Choose a topic that you want to understand better;

- Choose a topic that you want to read about and devote time to;

- Choose a topic that is perhaps a bit out of your comfort zone;

- Choose a topic that allows you to understand others’ opinions and how those opinions are shaped;

- Choose something that is relevant to you, personally or professionally;

- Do not choose a topic because you think it will be “easy” – those can end up being quite challenging.

Brainstorming Ideas for a Research Topic

There are many ways to come up with a good topic. The best thing to do is to give yourself time to think about what you really want to commit days and weeks to reading, thinking, researching, more reading, writing, more researching, reading and writing on.

It can be difficult to come up with a topic from scratch, so consider looking at some information sources that can give you some ideas. Check out your favorite news sources or take a look at a library databases like CQ Researcher or Point of Review Reference Center.

As you browse through databases or news sources , ask yourself some of the following questions: Which question(s) below interest you? Which question(s) below spark a desire to respond? A good topic is one that moves you to think, to do, to want to know more, to want to say more. Here are some questions you might use in your search for topics:

- What news stories do you often see, but want to know more about?

- What (socio-political) argument do you often have with others that you would love to work on strengthening?

- What are the key controversies or current debates in the field of work that you want to go into?

- What is a problem that you see at work that needs to be better publicized or understood?

- What is the biggest issue facing [specific group of people: by age, by race, by gender, by ethnicity, by nationality, by geography, by economic standing? choose a group]

- What area/landmark/piece of history in your home community are you interested in?

- What local problem do you want to better understand?

- Is there some element of the career that you would like to have one day that you want to better understand?

- What would you love to become an expert on?

- What are you passionate about?

From Topic to Research Question

Once you have decided on a research topic, an area for academic exploration that matters to you, it is time to start thinking about what you want to learn about that topic.

The goal of college-level research assignments is never going to be to simply “go find sources” on your topic. Instead, think of sources as helping you to answer a research question or a series of research questions about your topic. These should not be simple questions with simple answers, but rather complex questions about which there is no easy or obvious answer.

A compelling research question is one that may involve controversy, or may have a variety of answers, or may not have any single, clear answer. All of that is okay and even desirable. If the answer is an easy and obvious one, then there is little need for argument or research.

Make sure that your research question is clear, specific, researchable and limited (but not too limited). Most of all, make sure that you are curious about your own research question. If it does not matter to you, researching it will feel incredibly boring and tedious.

This section contains material from:

Zickel, Emilie. “Developing a Research Question.” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing , by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/developing-a-research-question/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

- Toni Morrison, “Toni Morrison,” in Black Women Writers at Work , ed. Claudia Tate (Continuum Publish Company, 1983), 130. ↵

A database is an organized collection of data in a digital format. Library research databases are often composed of academic publications like journal articles and book chapters, although there are also specialty databases that have data like engineering specifications or world news articles.

A news source is a story or article that runs in a journalism publication or outlet. News sources tend to be about current events, but there are also opinion pieces and investigative journalism pieces that may cover broader topics over a longer period of time.

7.1 Developing a Research Question Copyright © 2022 by Emilie Zickel and Terri Pantuso is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Chapter 9: The Research Process

9.1 Developing a Research Question

Emilie Zickel

“I write out of ignorance. I write about the things I don’t have any resolutions for, and when I’m finished, I think I know a little bit more about it. I don’t write out of what I know. It’s what I don’t know that stimulates me .” – Toni Morrison , author and Northeast Ohio native

Think of a research paper as an opportunity to deepen (or create!) knowledge about a topic that matters to you. Just as Toni Morrison states that she is stimulated by what she doesn’t yet know, a research paper assignment can be interesting and meaningful if it allows you to explore what you don’t know.

Research, at its best, is an act of knowledge creation, not just an extended book report. This knowledge creation is the essence of any great educational experience. Instead of being lectured at, you get to design the learning project that will ultimately result in you experiencing and then expressing your own intellectual growth. You get to read what you choose, and you get to become an expert on your topic.

That sounds, perhaps, like a lofty goal. But by spending some quality time brainstorming, reading, thinking or otherwise tuning into what matters to you, you can end up with a workable research topic that will lead you on an enjoyable research journey.

The best research topics are meaningful to you

- Choose a topic that you want to understand better.

- Choose a topic that you want to read about and devote time to

- Choose a topic that is perhaps a bit out of your comfort zone

- Choose a topic that allows you to understand others’ opinions and how those opinions are shaped.

- Choose something that is relevant to you, personally or professionally.

- Do not choose a topic because you think it will be “easy” – those can end up being even quite challenging

The video below offers ideas on choosing not only a topic that you are drawn to, but a topic that is realistic and manageable for a college writing class.

“Choosing a Manageable Research Topic” by PfaulLibrary is licensed under CC BY

Brainstorming Ideas for a Research Topic

Which question(s) below interest you? Which question(s) below spark a desire to respond? A good topic is one that moves you to think, to do, to want to know more, to want to say more.

There are many ways to come up with a good topic. The best thing to do is to give yourself time to think about what you really want to commit days and weeks to reading, thinking, researching, more reading, writing, more researching, reading and writing on.

- What news stories do you often see, but want to know more about?

- What (socio-political) argument do you often have with others that you would love to work on strengthening?

- What would you love to become an expert on?

- What are you passionate about?

- What are you scared of?

- What problem in the world needs to be solved?

- What are the key controversies or current debates in the field of work that you want to go into?

- What is a problem that you see at work that needs to be better publicized or understood?

- What is the biggest issue facing [specific group of people: by age, by race, by gender, by ethnicity, by nationality, by geography, by economic standing? choose a group]

- If you could interview anyone in the world, who would it be? Can identifying that person lead you to a research topic that would be meaningful to you?

- What area/landmark/piece of history in your home community are you interested in?

- What in the world makes you angry?

- What global problem do you want to better understand?

- What local problem do you want to better understand?

- Is there some element of the career that you would like to have one day that you want to better understand?

- Consider researching the significance of a song, or an artist, or a musician, or a novel/film/short story/comic, or an art form on some aspect of the broader culture.

- Think about something that has happened to (or is happening to) a friend or family member. Do you want to know more about this?

- Go to a news source ( New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Christian Science Monitor, etc) and skim the titles of news stories. Does any story interest you?

From Topic to Research Question

Once you have decided on a research topic, an area for academic exploration that matters to you, it is time to start thinking about what you want to learn about that topic.

The goal of college-level research assignments is never going to be to simply “go find sources” on your topic. Instead, think of sources as helping you to answer a research question or a series of research questions about your topic. These should not be simple questions with simple answers, but rather complex questions about which there is no easy or obvious answer.

A compelling research question is one that may involve controversy, or may have a variety of answers, or may not have any single, clear answer. All of that is okay and even desirable. If the answer is an easy and obvious one, then there is little need for argument or research.

Make sure that your research question is clear, specific, researchable, and limited (but not too limited). Most of all, make sure that you are curious about your own research question. If it does not matter to you, researching it will feel incredibly boring and tedious.

The video below includes a deeper explanation of what a good research question is as well as examples of strong research questions:

“Creating a Good Research Question” by CII GSU

A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing by Emilie Zickel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Feedback/Errata

Comments are closed.

9.1 Developing a Research Question

Emilie Zickel

Think of a research paper as an opportunity to deepen (or create!) knowledge about a topic that matters to you. Just as Toni Morrison states that she is stimulated by what she doesn’t yet know, a research paper assignment can be interesting and meaningful if it allows you to explore what you don’t know.

Research, at its best, is an act of knowledge creation, not just an extended book report. This knowledge creation is the essence of any great educational experience. Instead of being lectured at, you get to design the learning project that will ultimately result in you experiencing and then expressing your own intellectual growth. You get to read what you choose, and you get to become an expert on your topic.

That sounds, perhaps, like a lofty goal. But by spending some quality time brainstorming, reading, thinking, or otherwise tuning into what matters to you, you can end up with a workable research topic that will lead you on an enjoyable research journey.

The best research topics are meaningful to you:

- Choose a topic that you want to understand better.

- Choose a topic that you want to read about and devote time to

- Choose a topic that is perhaps a bit out of your comfort zone

- Choose a topic that allows you to understand others’ opinions and how those opinions are shaped.

- Choose something that is relevant to you, personally or professionally.

- Do not choose a topic because you think it will be “easy”—those can end up being even quite challenging

The video below offers ideas on choosing not only a topic that you are drawn to, but a topic that is realistic and manageable for a college writing class.

“Choosing a Manageable Research Topic” by Pfaul Library is licensed under CC BY

Brainstorming Ideas for a Research Topic

Which question(s) below interest you? Which question(s) below spark a desire to respond? A good topic is one that moves you to think, to do, to want to know more, to want to say more.

There are many ways to come up with a good topic. The best thing to do is to give yourself time to think about what you really want to commit days and weeks to reading, thinking, researching, more reading, writing, more researching, reading, and writing on.

- What news stories do you often see, but want to know more about?

- What (socio-political) argument do you often have with others that you would love to work on strengthening?

- What would you love to become an expert on?

- What are you passionate about?

- What are you scared of?

- What problem in the world needs to be solved?

- What are the key controversies or current debates in the field of work that you want to go into?

- What is a problem that you see at work that needs to be better publicized or understood?

- What is the biggest issue facing [specific group of people: by age, by race, by gender, by ethnicity, by nationality, by geography, by economic standing? choose a group]

- If you could interview anyone in the world, who would it be? Can identifying that person lead you to a research topic that would be meaningful to you?

- What area/landmark/piece of history in your home community are you interested in?

- What in the world makes you angry?

- What global problem do you want to better understand?

- What local problem do you want to better understand?

- Is there some element of the career that you would like to have one day that you want to better understand?

- Consider researching the significance of a song, or an artist, or a musician, or a novel/film/short story/comic, or an art form on some aspect of the broader culture.

- Think about something that has happened to (or is happening to) a friend or family member. Do you want to know more about this?

- Go to a news source ( New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Christian Science Monitor, etc. ) and skim the titles of news stories. Does any story interest you?

From Topic to Research Question

Once you have decided on a research topic, an area for academic exploration that matters to you, it is time to start thinking about what you want to learn about that topic.

The goal of college-level research assignments is never going to be to simply “go find sources” on your topic. Instead, think of sources as helping you to answer a research question or a series of research questions about your topic. These should not be simple questions with simple answers, but rather complex questions about which there is no easy or obvious answer.

A compelling research question is one that may involve controversy, or may have a variety of answers, or may not have any single, clear answer. All of that is okay and even desirable. If the answer is an easy and obvious one, then there is little need for argument or research.

Make sure that your research question is clear, specific, researchable, and limited (but not too limited). Most of all, make sure that you are curious about your own research question. If it does not matter to you, researching it will feel incredibly boring and tedious.

The video below includes a deeper explanation of what a good research question is as well as examples of strong research questions:

“Creating a Good Research Question” by CII GSU

9.1 Developing a Research Question Copyright © 2022 by Emilie Zickel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Published on October 26, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research question pinpoints exactly what you want to find out in your work. A good research question is essential to guide your research paper , dissertation , or thesis .

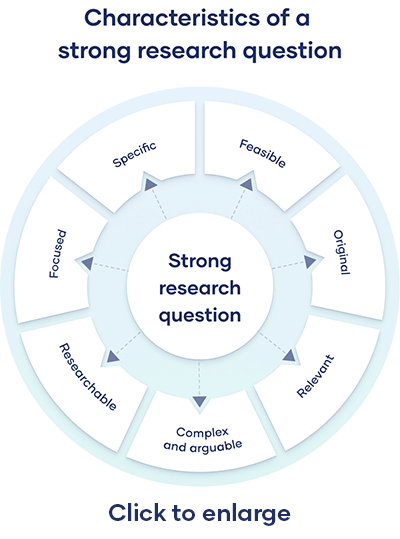

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Table of contents

How to write a research question, what makes a strong research question, using sub-questions to strengthen your main research question, research questions quiz, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research questions.

You can follow these steps to develop a strong research question:

- Choose your topic

- Do some preliminary reading about the current state of the field

- Narrow your focus to a specific niche

- Identify the research problem that you will address

The way you frame your question depends on what your research aims to achieve. The table below shows some examples of how you might formulate questions for different purposes.

Using your research problem to develop your research question

Note that while most research questions can be answered with various types of research , the way you frame your question should help determine your choices.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them. The criteria below can help you evaluate the strength of your research question.

Focused and researchable

Feasible and specific, complex and arguable, relevant and original.

Chances are that your main research question likely can’t be answered all at once. That’s why sub-questions are important: they allow you to answer your main question in a step-by-step manner.

Good sub-questions should be:

- Less complex than the main question

- Focused only on 1 type of research

- Presented in a logical order

Here are a few examples of descriptive and framing questions:

- Descriptive: According to current government arguments, how should a European bank tax be implemented?

- Descriptive: Which countries have a bank tax/levy on financial transactions?

- Framing: How should a bank tax/levy on financial transactions look at a European level?

Keep in mind that sub-questions are by no means mandatory. They should only be asked if you need the findings to answer your main question. If your main question is simple enough to stand on its own, it’s okay to skip the sub-question part. As a rule of thumb, the more complex your subject, the more sub-questions you’ll need.

Try to limit yourself to 4 or 5 sub-questions, maximum. If you feel you need more than this, it may be indication that your main research question is not sufficiently specific. In this case, it’s is better to revisit your problem statement and try to tighten your main question up.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

As you cannot possibly read every source related to your topic, it’s important to evaluate sources to assess their relevance. Use preliminary evaluation to determine whether a source is worth examining in more depth.

This involves:

- Reading abstracts , prefaces, introductions , and conclusions

- Looking at the table of contents to determine the scope of the work

- Consulting the index for key terms or the names of important scholars

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (“ x affects y because …”).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses . In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Formulating a main research question can be a difficult task. Overall, your question should contribute to solving the problem that you have defined in your problem statement .

However, it should also fulfill criteria in three main areas:

- Researchability

- Feasibility and specificity

- Relevance and originality

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 21). Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-questions/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to define a research problem | ideas & examples, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, 10 research question examples to guide your research project, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Writing and Rhetoric II

- Get Started

- News & Magazine Articles

- Scholarly Articles

- Books & Films

- Background Information

Choosing a Topic

Narrowing your topic, developing strong research questions, sample research questions.

- Types of Sources

- Evaluate Sources

- Social Media & News Literacy

- Copyright This link opens in a new window

- MLA Citations

A useful way to think about your project is to describe it in a three-step sentence that states your TOPIC + QUESTION + SIGNIFICANCE (or TQS):

Don’t worry if at first you can’t think of something to put as the significance in the third step. As you develop your answer, you’ll find ways to explain why your question is worth asking!

TQS sentence example:

I am working on the topic of the Apollo mission to the moon , because I want to find out why it was deemed so important in the 1960s , so that I can help my classmates understand the role of symbolic events in shaping national identity .

Note: The TQS formula is meant to prime your thinking. Use it to plan and test your question, but don’t expect to put it in your paper in exactly this form.

Adapted from Kate L. Turabian, Student’s Guide to Writing College Papers , 5th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), pp. 14–15.

Start researching your topic more broadly to help you narrow your topic.

Think about:

- Which aspects am I most interested in?

- Is there a particular group of people to focus on?

- Is there a particular place to focus on?

- Is there a particular time period to focus on?

- What's the right scope for this particular research project? (For example, how much can I meaningfully address in this many pages?)

Background information can help with these questions before you dive in to more focused research.

- Research Guides Curated guides for a variety of topics and subject areas. Use them to find subject-specific resources.

Now use your narrowed topic to develop a research question!

Your research question should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your subject area and/or society more broadly

Adapted from Shona McCombes, "Developing strong research questions." Scribbr , March 2021.

Adapted from: George Mason University Writing Center. (2008). How to write a research question. Retrieved from http://writingcenter.gmu.edu/?p=307.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Types of Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jan 12, 2024 1:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.colum.edu/wrII

Explaining ambiguity in scientific language

- Original Research

- Published: 19 August 2022

- Volume 200 , article number 354 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Beckett Sterner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5219-7616 1

663 Accesses

8 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The idea that ambiguity can be productive in data science remains controversial. Efforts to make scientific publications and data intelligible to computers generally assume that accommodating multiple meanings for words, known as polysemy, undermines reasoning and communication. This assumption has nonetheless been contested by historians, philosophers, and social scientists, who have applied qualitative research methods to demonstrate the generative and strategic value of polysemy. Recent quantitative results from linguistics have also shown how polysemy can actually improve the efficiency of human communication. I present a new conceptual typology based on a synthesis of prior research about the aims, norms, and circumstances under which polysemy arises and is evaluated. The typology supports a contextual pluralist view of polysemy’s value for scientific research practices: polysemy does both substantial positive and negative work in science, but its utility is context-sensitive in ways that are often overlooked by the norms people have formulated to regulate its use, including prior scholars researching polysemy. I also propose that historical patterns in the use of partial synonyms, i.e. terms with overlapping meanings, provide an especially promising phenomenon for integrative research addressing these issues.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Communicating Science: Heterogeneous, Multiform and Polysemic

On the Role of Language in Scientific Research: Language as Analytic, Expressive, and Explanatory Tool

Language, Thought, and the History of Science

Carmela Chateau-Smith

Data availability

Not applicable.

Alagić, D., & Šnajder, J. (2021). Representing word meaning in context via lexical substitutes. Automatika . https://doi.org/10.1080/00051144.2021.1928437 .

Article Google Scholar

Ali-Khan, S. E., Jean, A., MacDonald, E., et al. (2018). Defining Success in Open Science. Mni Open Research . https://doi.org/10.12688/mniopenres.12780.1 .

Altomonte, G. (2020). Exploiting ambiguity: A moral polysemy approach to variation in economic practices. American Sociological Review, 85 (1), 76–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419895986 .

Arp, R., Smith, B., & Spear, A. D. (2015). Building ontologies with basic formal ontology . MIT Press.

Beltagy, I., Lo, K., & Cohan, A. (2019). SciBERT: A pretrained language model for scientific text. http://arxiv.org/abs/1903.10676 [cs]

Bertone, M. A., Miko, I., Yoder, M. J., et al. (2013). Matching arthropod anatomy ontologies to the Hymenoptera Anatomy Ontology: Results from a manual alignment. Database, 2013, bas057–bas057. https://doi.org/10.1093/database/bas057 .

Bowen, G. A. (2006). Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5 (3), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500304 .

Bowker, G. C. (2000). Biodiversity datadiversity. Social Studies of Science, 30 (5), 643–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631200030005001 .

Bowker, G. C., & Star, S. L. (1999). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences . MIT Press.

Brandom, R. B. (2008). Between saying and doing: Towards an analytic pragmatism . Oxford University Press.

Carr, J. W., Smith, K., Culbertson, J., et al. (2020). Simplicity and informativeness in semantic category systems. Cognition, 202 (104), 289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104289 .

Català, N., Baixeries, J., Ferrer-Cancho, R., et al. (2021). Zipf’s laws of meaning in Catalan. http://arxiv.org/abs/2107.00042

Ceccarelli, L. (2001). Shaping science with rhetoric: The cases of Dobzhansky, Schrödinger, and Wilson . University of Chicago Press.

Ceusters, W., Smith, B., & Goldberg, L. (2005). A terminological and ontological analysis of the NCI thesaurus. Methods of Information in Medicine, 44 (04), 498–507. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1634000 .

Currie, A. (2015). Marsupial lions and methodological omnivory: Function, success and reconstruction in paleobiology. Biology & Philosophy, 30 (2), 187–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-014-9470-y .

Cusimano, S., & Sterner, B. (2019). Integrative pluralism for biological function. Biology & Philosophy, 34 (6), 55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-019-9717-8 .

Davenport, S., & Leitch, S. (2005). Circuits of power in practice: Strategic ambiguity as delegation of authority. Organization Studies, 26 (11), 1603–1623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605054627 .

DeFries, R., & Nagendra, H. (2017). Ecosystem management as a wicked problem. Science, 356 (6335), 265–270. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1950 .

Del Tredici, M., Nissim, M., & Zaninello, A. (2016). Tracing metaphors in time through self-distance in vector spaces. http://arxiv.org/abs/1611.03279 [cs]

Denis, J. L., Dompierre, G., Langley, A., et al. (2011). Escalating indecision: Between reification and strategic ambiguity. Organization Science, 22 (1), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0501 .

Devlin, J., Chang, M.W., Lee, K., et al. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. http://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805

Dietz, B. (2012). Contribution and co-production: The collaborative culture of Linnaean botany. Annals of Science, 69 (4), 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/00033790.2012.680982 .

Dourish, P. (2001). Process descriptions as organisational accounting devices: the dual use of workflow technologies. In: Proceedings of the 2001 International ACM SIGGROUP conference on supporting group work. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, GROUP ’01 (pp 52–60), https://doi.org/10.1145/500286.500297

Dragisic, Z., Ivanova, V., Li, H., et al. (2017). Experiences from the anatomy track in the ontology alignment evaluation initiative. Journal of Biomedical Semantics, 8 (1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13326-017-0166-5 .

Duncan, M. (2020). Terminology version control discussion paper. http://mrtablet.co.uk/chocolate_teapot_lite.htm

Eisenberg, E. M. (1984). Ambiguity as strategy in organizational communication. Communication Monographs, 51 (3), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758409390197 .

Ferraro, F., Etzion, D., & Gehman, J. (2015). Tackling grand challenges pragmatically: Robust action revisited. Organization Studies, 36 (3), 363–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840614563742 .

Ferrer-i Cancho, R., Bentz, C., & Seguin, C. (2020). Optimal coding and the origins of Zipfian laws. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics . https://doi.org/10.1080/09296174.2020.1778387 .

Fokkens, A., Ter Braake, S., Maks, I., et al. (2016). On the semantics of concept drift: Towards formal definitions of semantic change. Proceedings of Drift-a-LOD (2016): 247–265.

Franz, N. M., & Sterner, B. W. (2018). To increase trust, change the social design behind aggregated biodiversity data. Database . https://doi.org/10.1093/database/bax100 .

Galison, P. (1996). Computer simulations and the trading zone. In P. Galison & D. J. Stump (Eds.), The disunity of science: Boundaries, contexts, and power (pp. 118–57). Stanford University Press.

Garnett, S. T., Christidis, L., Conix, S., et al. (2020). Principles for creating a single authoritative list of the world’s species. PLoS Biology, 18 (7), e3000736. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000736 .

Garson, J. (2016). A critical overview of biological functions . Springer.

Geeraerts, D. (1997). Diachronic prototype semantics: A contribution to historical lexicology . Clarendon Press.

Gentner, D., & Grudin, J. (1985). The evolution of mental metaphors in psychology: A 90-year retrospective. American Psychologist, 40 (2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.40.2.181 .

Germain, P. L., Ratti, E., & Boem, F. (2014). Junk or functional DNA? ENCODE and the function controversy. Biology & Philosophy, 29 (6), 807–831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-014-9441-3 .

Gerson, E. M. (2008). Reach, bracket, and the limits of rationalized coordination: Some challenges for CSCW. Resources, co-evolution and artifacts (pp. 193–220). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84628-901-9_8 .

Gibson, E., Futrell, R., Piantadosi, S. P., et al. (2019). How efficiency shapes human language. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23 (5), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.02.003 .

Giroux, H. (2006). ‘It was such a handy term’: Management fashions and pragmatic ambiguity. Journal of Management Studies, 43 (6), 1227–1260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00623.x .

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78 (6), 1360–1380. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469 .

Grantham, T. A. (2004). Conceptualizing the (dis)unity of science. Philosophy of Science, 71 (2), 133–155. https://doi.org/10.1086/383008 .

Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., et al. (2005). Storylines of research in diffusion of innovation: A meta-narrative approach to systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 61 (2), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.001 .

Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation, syntax and semantics. Speech Acts, 3, 41–58.

Google Scholar

Grosholz, E. (2007). Representation and productive ambiguity in mathematics and the sciences . Oxford University Press.

Gross, A. G. (2006). Starring the text: The place of rhetoric in science studies . Southern Illinois University Press.

Hamilton, W.L., Leskovec, J., & Jurafsky, D. (2016). Diachronic word embeddings reveal statistical laws of semantic change. In: Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, Berlin, Germany (pp 1489–1501). https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P16-1141

Hauer, B., & Kondrak, G. (2020). Synonymy = Translational Equivalence. http://arxiv.org/abs/2004.13886 [cs]

Hesse, M. (1988). The cognitive claims of metaphor. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 2 (1), 1–16.

Higuera, C. R. (2018). Productive perils: On metaphor as a theory-building device. Linguistic Frontiers, 1 (2), 102–111.

Hirsch, P. M., & Levin, D. Z. (1999). Umbrella advocates versus validity police: A life-cycle model. Organization Science, 10 (2), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.2.199 .

Jarzabkowski, P., Sillince, J. A., & Shaw, D. (2010). Strategic ambiguity as a rhetorical resource for enabling multiple interests. Human Relations, 63 (2), 219–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709337040 .

Johansen, Winni. (2018). Strategic Ambiguity. In: The International Encyclopedia of Strategic Communication, edited by Robert L Heath, Winni Johansen, et al., 1st ed. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119010722.iesc0170.

Karjus, A., Blythe, R.A., Kirby, S., et al. (2020). Communicative need modulates competition in language change. http://arxiv.org/abs/2006.09277 [cs]

Kemp, C., Xu, Y., & Regier, T. (2018). Semantic typology and efficient communication. Annual Review of Linguistics, 4 (1), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011817-045406 .

Keuchenius, A., Törnberg, P., & Uitermark, J. (2021). Adoption and adaptation: A computational case study of the spread of Granovetter’s weak ties hypothesis. Social Networks, 66, 10–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2021.01.001 .

Kilgarriff, A. (1997). I don’t believe in word senses. Computers and the Humanities, 31 (2), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1000583911091 .

L’ Homme, M.C., Robichaud, B., & Subirats, C. (2020). Building multilingual specialized resources based on FrameNet: Application to the field of the environment. In: Proceedings of the International FrameNet Workshop 2020: Towards a Global, Multilingual FrameNet. European Language Resources Association, Marseille, France (pp 85–92) https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/2020.framenet-1.12

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2008). Metaphors we live by . University of Chicago press.

Laubichler, M. D., Prohaska, S. J., & Stadler, P. F. (2018). Toward a mechanistic explanation of phenotypic evolution: The need for a theory of theory integration. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution, 330 (1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.b.22785 .

Lean, O. M. (2021). Are bio-ontologies metaphysical theories? Synthese . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03303-4 .

Leon-Arauz, P., Martin, A. S., & Reimerink, A. (2018). The EcoLexicon English corpus as an open corpus in sketch engine. http://arxiv.org/abs/1807.05797 [cs]

Leonelli, S. (2012). Classificatory theory in data-intensive science: The case of open biomedical ontologies. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 26 (1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02698595.2012.653119 .

Leonelli, S. (2016). Data-centric biology: A philosophical study . University of Chicago Press.

Leonelli, S., & Tempini, N. (2020). Data journeys in the sciences. Springer . https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37177-7 .

Lidgard, S., & Love, A. C. (2018). Rethinking living fossils. BioScience, 68 (10), 760–770. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biy084 .

Li, J., & Joanisse, M. F. (2021). Word senses as clusters of meaning modulations: A computational model of polysemy. Cognitive Science, 45 (4), e12955. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12955 .

Linquist, S., Doolittle, W. F., & Palazzo, A. F. (2020). Getting clear about the F-word in genomics. PLoS Genetics, 16 (4), e1008702. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008702 .

Loureiro, D., Rezaee, K., Pilehvar, M. T., et al. (2021). Analysis and evaluation of language models for word sense disambiguation. Computational Linguistics (pp 1–57). https://doi.org/10.1162/coli_a_00405

McMahan, P., & Evans, J. (2018). Ambiguity and engagement. American Journal of Sociology, 124 (3), 860–912. https://doi.org/10.1086/701298 .

Meyer, F., & Lewis, M. (2020). Modelling lexical ambiguity with density matrices. http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.05670 [cs]

Miller, G. A. (1995). WordNet: A lexical database for English. Communications of the ACM, 38 (11), 39–41. https://doi.org/10.1145/219717.219748 .

Monckton, S., Johal, S., Packer, L., et al. (2020). Inadequate treatment of taxonomic information prevents replicability of most zoological research. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 98 (9), 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2020-0027 .

Mons, B., Schultes, E., Liu, F., et al. (2019). The FAIR principles: First generation implementation choices and challenges. Data Intelligence, 2 (1–2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1162/dint_e_00023 .

Nakazawa, T. (2020). Species interaction: Revisiting its terminology and concept. Ecological Research, 35 (6), 1106–1113. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1703.12164 .

Nerlich, B., & Clarke, D. D. (2001). Ambiguities we live by: Towards a pragmatics of polysemy. Journal of Pragmatics, 33 (1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00132-0 .

Neto, C. (2020). When imprecision is a good thing, or how imprecise concepts facilitate integration in biology. Biology & Philosophy, 35 (6), 58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10539-020-09774-y .

Oliveira, D., & Pesquita, C. (2018). Improving the interoperability of biomedical ontologies with compound alignments. Journal of Biomedical Semantics, 9 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13326-017-0171-8 .

Olson, M. E., Arroyo-Santos, A., & Vergara-Silva, F. (2019). A user’s guide to metaphors in ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34 (7), 605–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.03.001 .

Ortony, A. (1993). Metaphor and thought (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Panchenko, A., Ruppert, E., Faralli, S., et al. (2017). Unsupervised does not mean uninterpretable : the case for word sense induction and disambiguation. In: 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics : proceedings of conference, volume 1: Long Papers. Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, pp 86–98.Stroudsburg, PA, pp 86–98. https://ub-madoc.bib.uni-mannheim.de/42007

Perrault, S. T., & O’Keefe, M. (2019). New metaphors for new understandings of genomes. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 62 (1), 1–19.

Piantadosi, S. T., Tily, H., & Gibson, E. (2012). The communicative function of ambiguity in language. Cognition, 122 (3), 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2011.10.004 .

Pimentel, T., Maudslay, R.H., Blasi, D., et al. (2020). Speakers fill lexical semantic gaps with context. http://arxiv.org/abs/2010.02172

Poesio,M. (2020).”Ambiguity".In: The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Semantics, edited by Daniel Gutzmann, Lisa Matthewson, et al., 1st ed., 1–38. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118788516.sem098

Poirier, L. (2019). Classification as catachresis: Double binds of representing difference with semiotic infrastructure. Canadian Journal of Communication . https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2019v44n3a3455 .

Ribes, D., & Bowker, G. C. (2009). Between meaning and machine: Learning to represent the knowledge of communities. Information and Organization, 19 (4), 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2009.04.001 .

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4, 155–169.

Schlechtweg, D., Eckmann, S., Santus, E., et al. (2017). German in flux: Detecting metaphoric change via word entropy. http://arxiv.org/abs/1706.04971

Sennet, A. (2021). Ambiguity. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (fall 2021). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Shavit, A., & Griesemer, J. (2011). Transforming objects into data: How minute technicalities of recording “species location” entrench a basic challenge for biodiversity. In: M. Carrier & A. Nordmann, Science in the context of application (Vol. 274, pp. 169–193). Springer. Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9051-5_12 .

Shipman, F. M., & Marshall, C. C. (1999). Formality considered harmful: Experiences, emerging themes, and directions on the use of formal representations in interactive systems. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 8 (4), 333–352. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008716330212 .

Stankowski, S., & Ravinet, M. (2021). Quantifying the use of species concepts. Current Biology, 31 (9), R428–R429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.060 .

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, “translations’’ and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s museum of vertebate zoology, 1907–39. Social Studies of Science, 19, 387–420.

Sterner, B. W., & Franz, N. M. (2017). Taxonomy for Humans or Computers? Cognitive Pragmatics for Big Data. Biological Theory 12 (2), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13752-017-0259-5

Sterner, B. W., Gilbert, E. E., & Franz, N. M. (2020). Decentralized but globally coordinated biodiversity data. Frontiers in Big Data, 3 (519), 133. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2020.519133 .

Sterner, B. W., Witteveen, J., & Franz, N. M. (2020). Coordinating dissent as an alternative to consensus classification: Insights from systematics for bio-ontologies. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 42 (1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-020-0300-z .

Swedberg, R. (2020). Using metaphors in sociology: Pitfalls and potentials. The American Sociologist, 51, 240–257.

Tahmasebi, N., Borin, L., Jatowt, A., et al. (2021). Computational approaches to semantic change. Language Science Press. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5040241.

Takacs, D. (1996). The idea of biodiversity: Philosophies of paradise . Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ustalov, D., Chernoskutov, M., Biemann, C., et al. (2018). Fighting with the sparsity of synonymy dictionaries for automatic synset induction. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. In W. M. van der Aalst, D. I. Ignatov, M. Khachay, et al. (Eds.), Analysis of images, social networks and texts (pp. 94–105). Springer International Publishing.

Volanschi, A., & Kübler, N. (2011). The impact of metaphorical framing on term creation in biology. Terminology International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Issues in Specialized Communication, 17 (2), 198–223. https://doi.org/10.1075/term.17.2.02vol .

Wilkinson, M. D., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I. J., et al. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18 .

Wilson, M. (2006). Wandering significance: An essay on conceptual behavior . Oxford University Press.

Winkler, S. (2015). Exploring ambiguity and the ambiguity model from a transdisciplinary perspective. In: Winkler, S. Ambiguity. De Gruyter . https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110403589-002/html .

Download references

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by NSF Science and Technology Studies Grant STS-1827993. My thanks to Joeri Witteveen, Elizabeth Lerman, Nico Franz, and Manfred Laubichler for their conversations and feedback about the ideas presented here. My special thanks also to the reviewers whose constructive comments helped improve the manuscript significantly. All mistakes are entirely my own.

Funding was provided by NSF STS-1827993.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, PO Box 873301, Tempe, AZ, 85287, USA

Beckett Sterner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Corresponding author.

Correspondence to Beckett Sterner .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Consent to participate, consent for publication, code availability, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Sterner, B. Explaining ambiguity in scientific language. Synthese 200 , 354 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03792-x

Download citation

Received : 22 October 2021

Accepted : 23 June 2022

Published : 19 August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-022-03792-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Lexical semantics

- Computer ontologies

- Philosophy of science

- Strategic ambiguity

Advertisement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Importance of Narrowing the Research Topic

Whether you are assigned a general issue to investigate, must choose a problem to study from a list given to you by your professor, or you have to identify your own topic to investigate, it is important that the scope of the research problem is not too broad, otherwise, it will be difficult to adequately address the topic in the space and time allowed. You could experience a number of problems if your topic is too broad, including:

- You find too many information sources and, as a consequence, it is difficult to decide what to include or exclude or what are the most relevant sources.

- You find information that is too general and, as a consequence, it is difficult to develop a clear framework for examining the research problem.

- A lack of sufficient parameters that clearly define the research problem makes it difficult to identify and apply the proper methods needed to analyze it.

- You find information that covers a wide variety of concepts or ideas that can't be integrated into one paper and, as a consequence, you trail off into unnecessary tangents.

Lloyd-Walker, Beverly and Derek Walker. "Moving from Hunches to a Research Topic: Salient Literature and Research Methods." In Designs, Methods and Practices for Research of Project Management . Beverly Pasian, editor. ( Burlington, VT: Gower Publishing, 2015 ), pp. 119-129.

Strategies for Narrowing the Research Topic

A common challenge when beginning to write a research paper is determining how and in what ways to narrow down your topic . Even if your professor gives you a specific topic to study, it will almost never be so specific that you won’t have to narrow it down at least to some degree [besides, it is very boring to grade fifty papers that are all about the exact same thing!].

A topic is too broad to be manageable when a review of the literature reveals too many different, and oftentimes conflicting or only remotely related, ideas about how to investigate the research problem. Although you will want to start the writing process by considering a variety of different approaches to studying the research problem, you will need to narrow the focus of your investigation at some point early in the writing process. This way, you don't attempt to do too much in one paper.

Here are some strategies to help narrow the thematic focus of your paper :

- Aspect -- choose one lens through which to view the research problem, or look at just one facet of it [e.g., rather than studying the role of food in South Asian religious rituals, study the role of food in Hindu marriage ceremonies, or, the role of one particular type of food among several religions].

- Components -- determine if your initial variable or unit of analysis can be broken into smaller parts, which can then be analyzed more precisely [e.g., a study of tobacco use among adolescents can focus on just chewing tobacco rather than all forms of usage or, rather than adolescents in general, focus on female adolescents in a certain age range who choose to use tobacco].

- Methodology -- the way in which you gather information can reduce the domain of interpretive analysis needed to address the research problem [e.g., a single case study can be designed to generate data that does not require as extensive an explanation as using multiple cases].

- Place -- generally, the smaller the geographic unit of analysis, the more narrow the focus [e.g., rather than study trade relations issues in West Africa, study trade relations between Niger and Cameroon as a case study that helps to explain economic problems in the region].

- Relationship -- ask yourself how do two or more different perspectives or variables relate to one another. Designing a study around the relationships between specific variables can help constrict the scope of analysis [e.g., cause/effect, compare/contrast, contemporary/historical, group/individual, child/adult, opinion/reason, problem/solution].

- Time -- the shorter the time period of the study, the more narrow the focus [e.g., restricting the study of trade relations between Niger and Cameroon to only the period of 2010 - 2020].

- Type -- focus your topic in terms of a specific type or class of people, places, or phenomena [e.g., a study of developing safer traffic patterns near schools can focus on SUVs, or just student drivers, or just the timing of traffic signals in the area].

- Combination -- use two or more of the above strategies to focus your topic more narrowly.

NOTE : Apply one of the above strategies first in designing your study to determine if that gives you a manageable research problem to investigate. You will know if the problem is manageable by reviewing the literature on your more narrowed problem and assessing whether prior research is sufficient to move forward in your study [i.e., not too much, not too little]. Be careful, however, because combining multiple strategies risks creating the opposite problem--your problem becomes too narrowly defined and you can't locate enough research or data to support your study.

Booth, Wayne C. The Craft of Research . Fourth edition. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2016; Coming Up With Your Topic. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College; Narrowing a Topic. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Narrowing Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Strategies for Narrowing a Topic. University Libraries. Information Skills Modules. Virginia Tech University; The Process of Writing a Research Paper. Department of History. Trent University; Ways to Narrow Down a Topic. Contributing Authors. Utah State OpenCourseWare.

- << Previous: Reading Research Effectively

- Next: Broadening a Topic Idea >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 1:38 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Ind Psychiatry J

- v.32(1); Jan-Jun 2023

- PMC10236658

Selecting a thesis topic: A postgraduate’s dilemma

Rajiv k. saini.

Department of Psychiatry, Command Hospital (EC) Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Mohan Issac

1 Department of Psychiatry, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia

K. J. D. Kumar

2 Department of Psychiatry, Military Hospital, Pathankot, Punjab, India

Suprakash Chaudhury

3 Department of Psychiatry, D. Y. Patil Medical College, Dr. D. Y. Patil Vidyapeeth, Pimpri, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Rachit Sharma

4 Department of Psychiatry, Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra, India

Ankit Dangi

5 Department of Psychiatry, Command Hospital, Panchkula, Haryana, India

It is said that well begun is half done. Choosing a thesis topic and submitting a research protocol is an essential step in the life cycle of a postgraduate resident. National Medical Commission of India mandates that all postgraduate trainees must submit at least one original research work (dissertation), one oral paper, one poster, and one publication to be eligible for final year examination. It is the duty of the faculty to ensure that trainees take active interest and submit their theses on time. However, their journey is often marred by multiple challenges and hurdles. The literature was searched from year 2000 onwards till 2011 using Pubmed, ResearchGate, MEDLINE, and the Education Resources Information Centre databases with terms related to residency training, selecting thesis topic, challenges or hurdles, and conversion of thesis into journal article. Existing literature on the subject matter is sparse. Current article advocates promotion of ethical and original research during postgraduation and proposes a checklist for residents before submission of their proposals.

INTRODUCTION

Residency is an extremely important period in the life cycle of a modern medical graduate. During this period, a resident learns to practice and acquire proficiency in a subject under guidance of a teacher. Along with acquiring new skills, it is also expected that they learn to critically analyze clinical scenarios and reach a rational conclusion. They are also expected to formulate and conduct original research which is submitted in form of a dissertation or thesis. Research work by a postgraduate should eventually translate into a scientific publication in a peer-reviewed medical journal, which helps in dissemination of thesis findings to the community and scientists. It is essential toward furthering medical knowledge, clinical practice, and the progression of science.[ 1 ] The National Medical Commission has stated the aims of completing this task as “Writing the thesis is aimed at contributing to the development of a spirit of inquiry, besides exposing the candidate to the techniques of research, critical analysis, acquaintance with the latest advances in medical science and the manner of identifying and consulting available literature.”[ 2 ]

CHOOSING THE TOPIC

The most intriguing question while conducting research is “How do I choose the right topic and will I be able to find the right answer?” Starting off with fire in the belly gives the best chance of seeing one’s work through. So, it is important to choose something that entices one’s mind and promises a gratifying result. Existing literature on the topic suggests that the journey of choosing the right topic is often marred by multiple challenges and dilemmas at various stages of this tumultuous journey. There are constraints of time, availability of resources, and support network.[ 3 ]

Therefore, students must remain open to suggestions from within and outside their minds. It is also important to allow the research area to simmer inside their mind for some time so that they can analyze various facets of the chosen area. It is at deeper layer of learning where higher order thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation reside. This then justifies the longer period it takes to arrive at a meaningful thesis title as it represents the highest order of cognitive reasoning referred to as “create” stage.[ 2 ] Short of this, novice researchers operate at lower order and remain “copy-paste” type of researchers.[ 4 ]

Lord “Dhanwantri” also known Physician of Gods brought “ Amrit ” elixir of life after “Samudra Manthan,” which was the result of intensive deliberations.[ 5 ] A systematic stepwise approach for answering any research question offers the best chance of finding the right answer. Succeeding paragraphs in this article shall delve into an enriching scientific journey toward zeroing onto a suitable thesis title.

Area of interest

A journey into an area of one’s interest is bound to be fulfilling. It is a good idea to review one’s past works and experiences, which may be intriguing. A frank and one-to-one discussion with the guide further helps in unravelling novel ideas. Starting with an open and fertile mind promises novel ideas and helps to sustain long-term interest and enthusiasm.[ 6 ] Tendency to merely replicate similar studies should be avoided as they fail to ignite the zest for newer information.[ 7 ] Think about why you got into your field of study. Consider what you like to read about in your free time, especially things related to your field.

From general to specific

A dissertation topic in medicine needs to be captivating and must intrigue the reader to look closer into the research work.[ 8 ] At the outset, it is a good strategy to just define a broad area and a dissertation topic need not be very specific or restrictive. The defined general area must be studied thoroughly and all its facets analyzed in detail. Look for gaps in knowledge which offer an avenue for research. For example, while studying factors responsible for relapse in alcohol dependence, doing a research on employment status of the spouse may be a good idea as it may not have been studied as extensively as other factors. It is needless to say that the student must first be familiar with the disease and all the variables which define its long-term trajectory. Medical science is an evolving field . There are factors of significance that can crop up during course of the study. Therefore, some scope for minor modifications must be kept for unexpected spinoffs. Most of the institutional review board permit minor revision of the protocols though they adhere to their own standards to safeguard interests of the patients. Authors conducted a survey and found that out of 184 submitted, 96 (52%) received requests for minor revision of research protocols. The acceptance resulted in further refinements in research methodology and outcomes.[ 9 ] Therefore, while submitting any protocol, some scope for minor change with probable reasons must be endorsed so that there are no complications while submitting final draft. After discussion with the guide, a suitable title can be given to the research proposal. Selection of the title should be such that it reflects the gist of the whole research and must attract attention of the reader. The title has a long shelf life and may be the first (and many a times, also the only) part of an article that readers see or read. Based on their understanding of the title, readers decide if the article is relevant to them or not.[ 8 ]

Do not bite more than you can chew

The average time allotted for completion of the MD/MS/DNB thesis is 2 years. It may be further reduced due to administrative delays like allotment of thesis guides and selection of topic. It is safe to assume that it takes around 1 month to finalize and submit the protocol and 2 months to write, print, and submit the complete thesis. That leaves just around year and nine months for actual and adequate data collection. All these facts must be kept in mind to ensure genuineness of data.[ 10 ]

A bird in hand is worth two in the bush

Modern medical science thrives on multispecialty approach, and it is not uncommon that students may end up with a research topic involving more than one department or more than one facility of the institution. Studies conducted during Covid pandemic are perfect examples owing to multiple facets of the illness in terms of prevention, pathophysiology, and long-term sequele.[ 11 ] A realistic check for the available resources in terms of infrastructure, availability of study materials, and support from affiliated departments must be done before finalizing the research topic. It is highly unlikely that your thesis is the first or the last research work in a particular area. Negotiating with other department/institution to regularly avail their facilities is often challenging. It is because of the difference in timing, priorities, work culture, and administrative barriers. One way to deal with it is to have a co-guide from that facility/institution. Dissertation reviewers have noticed that students often select topics that become unmanageable during course of their study. It can lead to development of stress and uncertainty about findings at the time of analysis. It was found that institutional support in terms of guidance, access to other departments, and statistical guidance improved overall performance of students and led to timely submission of thesis for publication in journals.[ 12 ]

Avoid controversy

Getting into controversy during initial years of residency is bound to raise stress levels and may dissuade the worker from continuing the research work. Field of medicine is fast evolving on the wheels of technology. Moral and ethical boundaries are slowly getting blurred. Many a times, laws are not revised and many laws are land specific. Therefore, it is a sound practice to familiarize oneself with existing laws and to take care that they are not violated. Central Drug Standard and Control Organization is the regulatory authority responsible for clinical trial oversight, approval, and inspections in India. It functions under Director General of Health Servicesand part of Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The information is available online on their website and it is updated regularly. It is a good idea to visit the website and familiarize oneself about the existing laws before undertaking any research work. The website also gives information about National Ethical Guidelines for biomedical and health research involving human participants. Similarly, informed consent needs to be spelt out quite clearly and should be devoid of incomplete information or concealment of vital health related information. It is now mandatory that all research proposals be vetted by institutional ethical committee prior to submission to the university.[ 13 - 15 ]

Conformation with national health policy

Young medical professionals can contribute immensely by their research designs and valuable inputs in ratifying existing health-related measures or to suggest further refinements. This concept must always be kept in mind while formulating any research designs. Researchers of today are planners for tomorrow and their work is reflection of their goal toward health of the nation. In a comprehensive report, it was found that merely 0.5% of the 4230 thesis citations were quoted in policy decision.[ 16 ] The figures may be even lower for this country. The figures are abysmal compared to the magnitude of the research undertaken in centers of higher learning. The success of National Iodine Deficiency Disorder Control Program in India owes credit to sound scientific inquiries beginning in 1956. Despite stiff opposition and cultural bias, the program gained strength and helped in significantly reducing burden of iodine deficiency disorders.[ 17 ] The findings led to significant policy change and legislation supporting sale of only iodized salt in the country.

Scope for publication

Any research work is considered futile if it does not reach the stage of publication in a reputed journal. A genuine research must eventually translate into a research article. It has become increasingly difficult to translate thesis into a scientific publication in an indexed journal due to stringent standards and peer review. In a retrospective analysis of 85 theses, it was found that the conversion rate to peer-reviewed publication was 32.5%. The most common reasons for not publishing were a lack of originality and poor design. The authors further encouraged publication of full length articles as it helped residents in long term.[ 18 ] Originality of research, sound methodology, and analysis of data besides cogency in manuscript writing have been defining factors that promote acceptance of an article in a reputed journal.[ 19 ] Lure of quick publishing in a predatory journal can be damaging in the long run. Young and inexperienced authors publishing in a predatory journal must be aware of the damage of their reputation, of inadequate peer-review processes and that these journals might get closed any time for variety of reasons. Such publishing harms the scientific community in the long run, and hence such an approach is best avoided.[ 20 ] It is prudent practice to check whether an intended journal is predatory or not from the https://predatoryjournals.com/journals/or Beall’s list (https://beallslist.net/). Similarly, increasing the score by “salami” publication is unethical and should be avoided.

Familiarization with research methodology

Imagine you are gifted a do-it-yourself kit to build a plane which can fly. It is meant for an age group of 18 years or more and should take 1 h to assemble. It has all the wheels, gears, levers, motors, wires, motherboard, etc., required to assemble it into a functioning plane. The kit also has a manual. How long should it take to assemble? 60 min? Now imagine trying to assemble without the manual. It may be extremely difficult if not impossible to assemble the plane and is surely bound to take much longer. Research methodology is exactly like a manual for research. A major confounding factor in medical research is student’s conceptual understanding and comfort level with research methodology.[ 21 ] Findings indicate that there were noticeable differences in perspectives regarding what constitutes research methodology and its utility at least during the first year of residency.[ 21 ] Familiarizing with basic research methods is now mandated for all the medical postgraduates before they submit their research proposals, and free certificate online courses are available on their website. Writing a thesis during MD/MS and DNB courses, without having a correct research methodology planning, is practically impossible. Some of the prominent causes of rejection of submitted manuscripts are poor methodology, small sample size, and poor statistical analysis.[ 22 ] Furthermore, postgraduate students choose research methodology based on a number of factors such as familiarity with a method, methodological orientation of the primary supervisor, the domain of study, and the nature of research problems pursued. Participants reported key challenges that they faced in understanding research methodology include framing research questions, understanding the theory or literature and its role in shaping research outcomes, and difficulties in performing data analysis.[ 23 ]

Motivation level of the researcher

Dr APJ Abdul Kalam, former president of India, quoted that “Dream is not that you see in sleep but it is something that doesn’t let you sleep.” No research work will reach its logical conclusion till the time a researcher has strong motivation to pursue it. Another factor that defines sustained interest in thesis topic is motivation. As described by David Langford, there exists a continuum from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation.[ 24 ] Extrinsic motivation basically refers to a situation wherein the students are ordered (to study). As we move along this continuum, the quality of learning improves consistently with the maturing of the relationship between teacher and student. The culmination of the relationship occurs when the teacher becomes an enabler while the student becomes an active self-learner (intrinsic motivation). The process involves a definitive element of mentorship. In traditional Indian context, Gurukul envisages a firm and enduring relationship between “Guru” (teacher) and “Shishya” (student). Vedas in ancient times were combined with prepared commentaries in the form of “Upanisads.” The term upanisad refers to “Sitting down near a teacher in order to learn.” Though many students have inherent intrinsic motivation, a dynamic “Guru” can really shape the “Shishya.” Though the concept is old, it still remains relevant in modern times because learning medical practice is both art and science and best habits are still passed on to the next generation by trained and experienced teachers.[ 25 ]

WHAT CAN HELP POSTGRADUATE THESIS SELECTION?