Home → Get Published → How to Publish a Research Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Publish a Research Paper: A Step-by-Step Guide

Jordan Kruszynski

- January 4, 2024

You’re in academia.

You’re going steady.

Your research is going well and you begin to wonder: ‘ How exactly do I get a research paper published?’

If this is the question on your lips, then this step-by-step guide is the one for you. We’ll be walking you through the whole process of how to publish a research paper.

Publishing a research paper is a significant milestone for researchers and academics, as it allows you to share your findings, contribute to your field of study, and start to gain serious recognition within the wider academic community. So, want to know how to publish a research paper? By following our guide, you’ll get a firm grasp of the steps involved in this process, giving you the best chance of successfully navigating the publishing process and getting your work out there.

Understanding the Publishing Process

To begin, it’s crucial to understand that getting a research paper published is a multi-step process. From beginning to end, it could take as little as 2 months before you see your paper nestled in the pages of your chosen journal. On the other hand, it could take as long as a year .

Below, we set out the steps before going into more detail on each one. Getting a feel for these steps will help you to visualise what lies ahead, and prepare yourself for each of them in turn. It’s important to remember that you won’t actually have control over every step – in fact, some of them will be decided by people you’ll probably never meet. However, knowing which parts of the process are yours to decide will allow you to adjust your approach and attitude accordingly.

Each of the following stages will play a vital role in the eventual publication of your paper:

- Preparing Your Research Paper

- Finding the Right Journal

- Crafting a Strong Manuscript

- Navigating the Peer-Review Process

- Submitting Your Paper

- Dealing with Rejections and Revising Your Paper

Step 1: Preparing Your Research Paper

It all starts here. The quality and content of your research paper is of fundamental importance if you want to get it published. This step will be different for every researcher depending on the nature of your research, but if you haven’t yet settled on a topic, then consider the following advice:

- Choose an interesting and relevant topic that aligns with current trends in your field. If your research touches on the passions and concerns of your academic peers or wider society, it may be more likely to capture attention and get published successfully.

- Conduct a comprehensive literature review (link to lit. review article once it’s published) to identify the state of existing research and any knowledge gaps within it. Aiming to fill a clear gap in the knowledge of your field is a great way to increase the practicality of your research and improve its chances of getting published.

- Structure your paper in a clear and organised manner, including all the necessary sections such as title, abstract, introduction (link to the ‘how to write a research paper intro’ article once it’s published) , methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Adhere to the formatting guidelines provided by your target journal to ensure that your paper is accepted as viable for publishing. More on this in the next section…

Step 2: Finding the Right Journal

Understanding how to publish a research paper involves selecting the appropriate journal for your work. This step is critical for successful publication, and you should take several factors into account when deciding which journal to apply for:

- Conduct thorough research to identify journals that specialise in your field of study and have published similar research. Naturally, if you submit a piece of research in molecular genetics to a journal that specialises in geology, you won’t be likely to get very far.

- Consider factors such as the journal’s scope, impact factor, and target audience. Today there is a wide array of journals to choose from, including traditional and respected print journals, as well as numerous online, open-access endeavours. Some, like Nature , even straddle both worlds.

- Review the submission guidelines provided by the journal and ensure your paper meets all the formatting requirements and word limits. This step is key. Nature, for example, offers a highly informative series of pages that tells you everything you need to know in order to satisfy their formatting guidelines (plus more on the whole submission process).

- Note that these guidelines can differ dramatically from journal to journal, and details really do matter. You might submit an outstanding piece of research, but if it includes, for example, images in the wrong size or format, this could mean a lengthy delay to getting it published. If you get everything right first time, you’ll save yourself a lot of time and trouble, as well as strengthen your publishing chances in the first place.

Step 3: Crafting a Strong Manuscript

Crafting a strong manuscript is crucial to impress journal editors and reviewers. Look at your paper as a complete package, and ensure that all the sections tie together to deliver your findings with clarity and precision.

- Begin by creating a clear and concise title that accurately reflects the content of your paper.

- Compose an informative abstract that summarises the purpose, methodology, results, and significance of your study.

- Craft an engaging introduction (link to the research paper introduction article) that draws your reader in.

- Develop a well-structured methodology section, presenting your results effectively using tables and figures.

- Write a compelling discussion and conclusion that emphasise the significance of your findings.

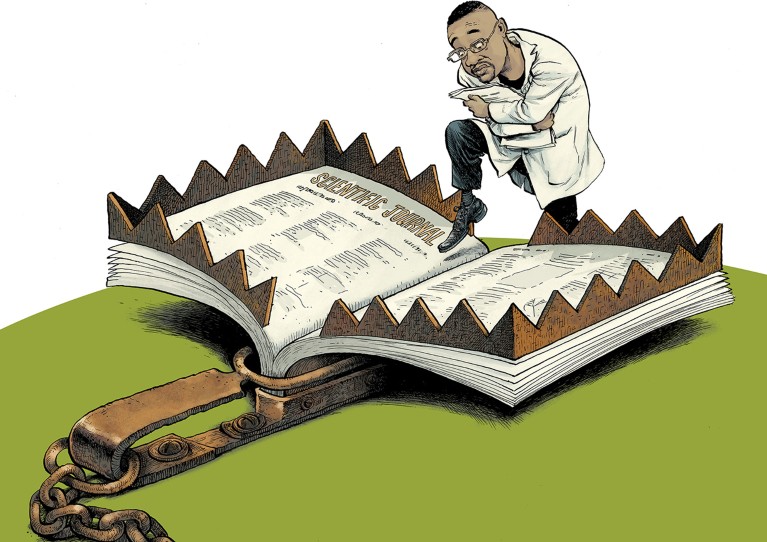

Step 4: Navigating the Peer-Review Process

Once you submit your research paper to a journal, it undergoes a rigorous peer-review process to ensure its quality and validity. In peer-review, experts in your field assess your research and provide feedback and suggestions for improvement, ultimately determining whether your paper is eligible for publishing or not. You are likely to encounter several models of peer-review, based on which party – author, reviewer, or both – remains anonymous throughout the process.

When your paper undergoes the peer-review process, be prepared for constructive criticism and address the comments you receive from your reviewer thoughtfully, providing clear and concise responses to their concerns or suggestions. These could make all the difference when it comes to making your next submission.

The peer-review process can seem like a closed book at times. Check out our discussion of the issue with philosopher and academic Amna Whiston in The Research Beat podcast!

Step 5: Submitting Your Paper

As we’ve already pointed out, one of the key elements in how to publish a research paper is ensuring that you meticulously follow the journal’s submission guidelines. Strive to comply with all formatting requirements, including citation styles, font, margins, and reference structure.

Before the final submission, thoroughly proofread your paper for errors, including grammar, spelling, and any inconsistencies in your data or analysis. At this stage, consider seeking feedback from colleagues or mentors to further improve the quality of your paper.

Step 6: Dealing with Rejections and Revising Your Paper

Rejection is a common part of the publishing process, but it shouldn’t discourage you. Analyse reviewer comments objectively and focus on the constructive feedback provided. Make necessary revisions and improvements to your paper to address the concerns raised by reviewers. If needed, consider submitting your paper to a different journal that is a better fit for your research.

For more tips on how to publish your paper out there, check out this thread by Dr. Asad Naveed ( @dr_asadnaveed ) – and if you need a refresher on the basics of how to publish under the Open Access model, watch this 5-minute video from Audemic Academy !

Final Thoughts

Successfully understanding how to publish a research paper requires dedication, attention to detail, and a systematic approach. By following the advice in our guide, you can increase your chances of navigating the publishing process effectively and achieving your goal of publication.

Remember, the journey may involve revisions, peer feedback, and potential rejections, but each step is an opportunity for growth and improvement. Stay persistent, maintain a positive mindset, and continue to refine your research paper until it reaches the standards of your target journal. Your contribution to your wider discipline through published research will not only advance your career, but also add to the growing body of collective knowledge in your field. Embrace the challenges and rewards that come with the publication process, and may your research paper make a significant impact in your area of study!

Looking for inspiration for your next big paper? Head to Audemic , where you can organise and listen to all the best and latest research in your field!

Keep striving, researchers! ✨

Table of Contents

Related articles.

You’re in academia. You’re going steady. Your research is going well and you begin to wonder: ‘How exactly do I get a

Behind the Scenes: What Does a Research Assistant Do?

Have you ever wondered what goes on behind the scenes in a research lab? Does it involve acting out the whims of

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction: Hook, Line, and Sinker

Want to know how to write a research paper introduction that dazzles? Struggling to hook your reader in with your opening sentences?

Blog Podcast

Privacy policy Terms of service

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Discover more from Audemic: Access any academic research via audio

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 7. The Results

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The results section is where you report the findings of your study based upon the methodology [or methodologies] you applied to gather information. The results section should state the findings of the research arranged in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation. A section describing results should be particularly detailed if your paper includes data generated from your own research.

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070.

Importance of a Good Results Section

When formulating the results section, it's important to remember that the results of a study do not prove anything . Findings can only confirm or reject the hypothesis underpinning your study. However, the act of articulating the results helps you to understand the problem from within, to break it into pieces, and to view the research problem from various perspectives.

The page length of this section is set by the amount and types of data to be reported . Be concise. Use non-textual elements appropriately, such as figures and tables, to present findings more effectively. In deciding what data to describe in your results section, you must clearly distinguish information that would normally be included in a research paper from any raw data or other content that could be included as an appendix. In general, raw data that has not been summarized should not be included in the main text of your paper unless requested to do so by your professor.

Avoid providing data that is not critical to answering the research question . The background information you described in the introduction section should provide the reader with any additional context or explanation needed to understand the results. A good strategy is to always re-read the background section of your paper after you have written up your results to ensure that the reader has enough context to understand the results [and, later, how you interpreted the results in the discussion section of your paper that follows].

Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Brett, Paul. "A Genre Analysis of the Results Section of Sociology Articles." English for Specific Speakers 13 (1994): 47-59; Go to English for Specific Purposes on ScienceDirect;Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit; "Reporting Findings." In Making Sense of Social Research Malcolm Williams, editor. (London;: SAGE Publications, 2003) pp. 188-207.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Organization and Approach

For most research papers in the social and behavioral sciences, there are two possible ways of organizing the results . Both approaches are appropriate in how you report your findings, but use only one approach.

- Present a synopsis of the results followed by an explanation of key findings . This approach can be used to highlight important findings. For example, you may have noticed an unusual correlation between two variables during the analysis of your findings. It is appropriate to highlight this finding in the results section. However, speculating as to why this correlation exists and offering a hypothesis about what may be happening belongs in the discussion section of your paper.

- Present a result and then explain it, before presenting the next result then explaining it, and so on, then end with an overall synopsis . This is the preferred approach if you have multiple results of equal significance. It is more common in longer papers because it helps the reader to better understand each finding. In this model, it is helpful to provide a brief conclusion that ties each of the findings together and provides a narrative bridge to the discussion section of the your paper.

NOTE : Just as the literature review should be arranged under conceptual categories rather than systematically describing each source, you should also organize your findings under key themes related to addressing the research problem. This can be done under either format noted above [i.e., a thorough explanation of the key results or a sequential, thematic description and explanation of each finding].

II. Content

In general, the content of your results section should include the following:

- Introductory context for understanding the results by restating the research problem underpinning your study . This is useful in re-orientating the reader's focus back to the research problem after having read a review of the literature and your explanation of the methods used for gathering and analyzing information.

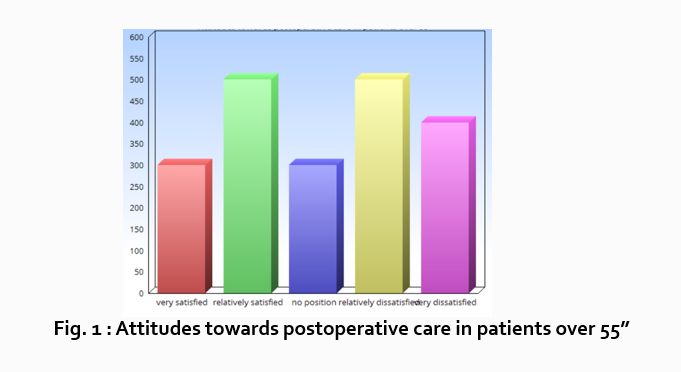

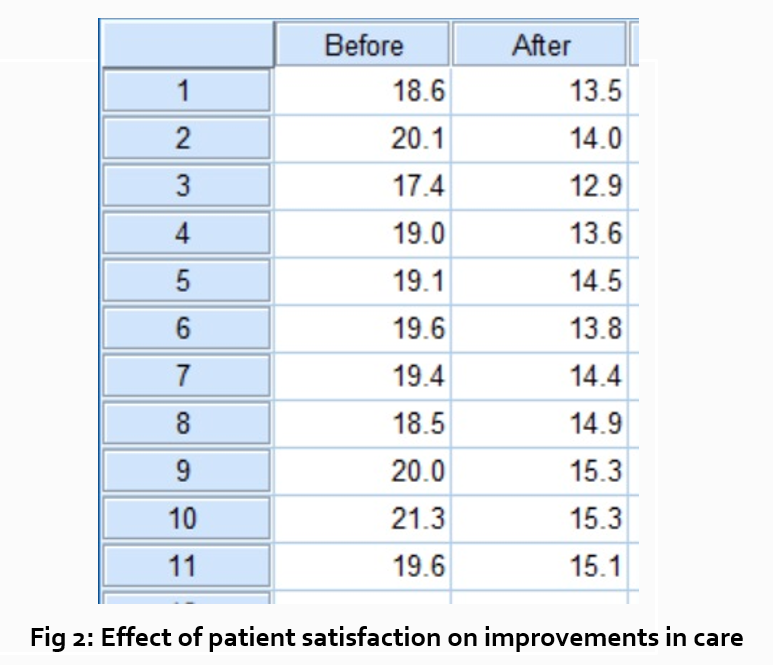

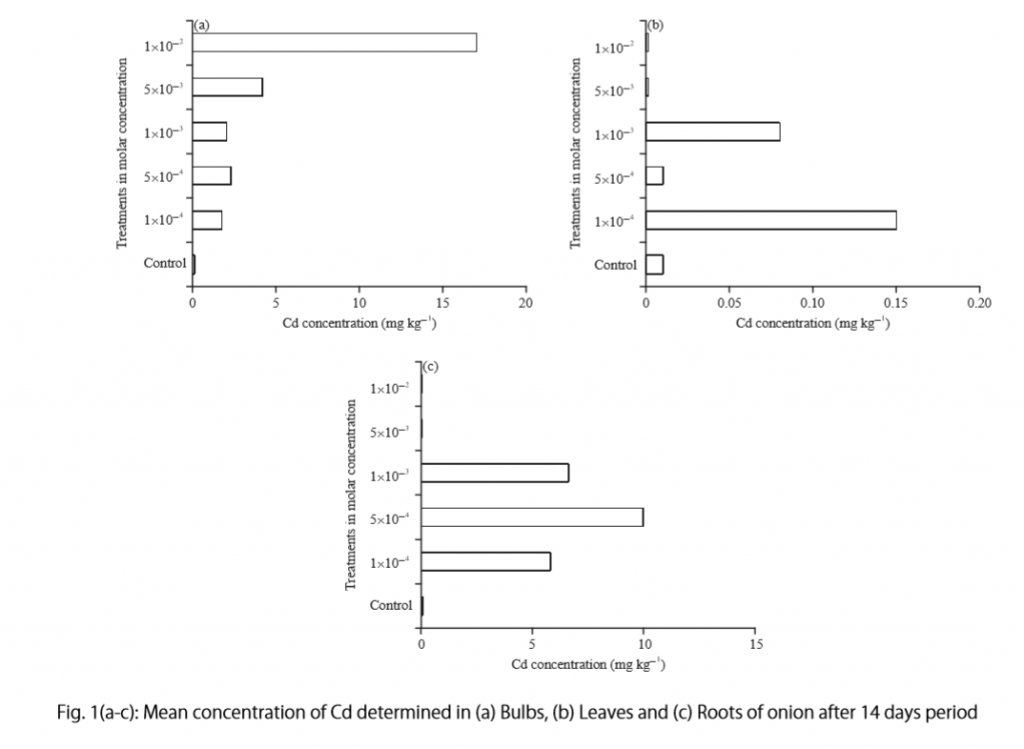

- Inclusion of non-textual elements, such as, figures, charts, photos, maps, tables, etc. to further illustrate key findings, if appropriate . Rather than relying entirely on descriptive text, consider how your findings can be presented visually. This is a helpful way of condensing a lot of data into one place that can then be referred to in the text. Consider referring to appendices if there is a lot of non-textual elements.

- A systematic description of your results, highlighting for the reader observations that are most relevant to the topic under investigation . Not all results that emerge from the methodology used to gather information may be related to answering the " So What? " question. Do not confuse observations with interpretations; observations in this context refers to highlighting important findings you discovered through a process of reviewing prior literature and gathering data.

- The page length of your results section is guided by the amount and types of data to be reported . However, focus on findings that are important and related to addressing the research problem. It is not uncommon to have unanticipated results that are not relevant to answering the research question. This is not to say that you don't acknowledge tangential findings and, in fact, can be referred to as areas for further research in the conclusion of your paper. However, spending time in the results section describing tangential findings clutters your overall results section and distracts the reader.

- A short paragraph that concludes the results section by synthesizing the key findings of the study . Highlight the most important findings you want readers to remember as they transition into the discussion section. This is particularly important if, for example, there are many results to report, the findings are complicated or unanticipated, or they are impactful or actionable in some way [i.e., able to be pursued in a feasible way applied to practice].

NOTE: Always use the past tense when referring to your study's findings. Reference to findings should always be described as having already happened because the method used to gather the information has been completed.

III. Problems to Avoid

When writing the results section, avoid doing the following :

- Discussing or interpreting your results . Save this for the discussion section of your paper, although where appropriate, you should compare or contrast specific results to those found in other studies [e.g., "Similar to the work of Smith [1990], one of the findings of this study is the strong correlation between motivation and academic achievement...."].

- Reporting background information or attempting to explain your findings. This should have been done in your introduction section, but don't panic! Often the results of a study point to the need for additional background information or to explain the topic further, so don't think you did something wrong. Writing up research is rarely a linear process. Always revise your introduction as needed.

- Ignoring negative results . A negative result generally refers to a finding that does not support the underlying assumptions of your study. Do not ignore them. Document these findings and then state in your discussion section why you believe a negative result emerged from your study. Note that negative results, and how you handle them, can give you an opportunity to write a more engaging discussion section, therefore, don't be hesitant to highlight them.

- Including raw data or intermediate calculations . Ask your professor if you need to include any raw data generated by your study, such as transcripts from interviews or data files. If raw data is to be included, place it in an appendix or set of appendices that are referred to in the text.

- Be as factual and concise as possible in reporting your findings . Do not use phrases that are vague or non-specific, such as, "appeared to be greater than other variables..." or "demonstrates promising trends that...." Subjective modifiers should be explained in the discussion section of the paper [i.e., why did one variable appear greater? Or, how does the finding demonstrate a promising trend?].

- Presenting the same data or repeating the same information more than once . If you want to highlight a particular finding, it is appropriate to do so in the results section. However, you should emphasize its significance in relation to addressing the research problem in the discussion section. Do not repeat it in your results section because you can do that in the conclusion of your paper.

- Confusing figures with tables . Be sure to properly label any non-textual elements in your paper. Don't call a chart an illustration or a figure a table. If you are not sure, go here .

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070; Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Caprette, David R. Writing Research Papers. Experimental Biosciences Resources. Rice University; Hancock, Dawson R. and Bob Algozzine. Doing Case Study Research: A Practical Guide for Beginning Researchers . 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press, 2011; Introduction to Nursing Research: Reporting Research Findings. Nursing Research: Open Access Nursing Research and Review Articles. (January 4, 2012); Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit ; Ng, K. H. and W. C. Peh. "Writing the Results." Singapore Medical Journal 49 (2008): 967-968; Reporting Research Findings. Wilder Research, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Human Services. (February 2009); Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Results. Thesis Writing in the Sciences. Course Syllabus. University of Florida.

Writing Tip

Why Don't I Just Combine the Results Section with the Discussion Section?

It's not unusual to find articles in scholarly social science journals where the author(s) have combined a description of the findings with a discussion about their significance and implications. You could do this. However, if you are inexperienced writing research papers, consider creating two distinct sections for each section in your paper as a way to better organize your thoughts and, by extension, your paper. Think of the results section as the place where you report what your study found; think of the discussion section as the place where you interpret the information and answer the "So What?" question. As you become more skilled writing research papers, you can consider melding the results of your study with a discussion of its implications.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn and Aleksandra Kasztalska. Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

- << Previous: Insiderness

- Next: Using Non-Textual Elements >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

You are using an outdated browser . Please upgrade your browser today !

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper in 7 Steps

What comes next after you're done with your research? Publishing the results in a journal of course! We tell you how to present your work in the best way possible.

This post is part of a series, which serves to provide hands-on information and resources for authors and editors.

Things have gotten busy in scholarly publishing: These days, a new article gets published in the 50,000 most important peer-reviewed journals every few seconds, while each one takes on average 40 minutes to read. Hundreds of thousands of papers reach the desks of editors and reviewers worldwide each year and 50% of all submissions end up rejected at some stage.

In a nutshell: there is a lot of competition, and the people who decide upon the fate of your manuscript are short on time and overworked. But there are ways to make their lives a little easier and improve your own chances of getting your work published!

Well, it may seem obvious, but before submitting an academic paper, always make sure that it is an excellent reflection of the research you have done and that you present it in the most professional way possible. Incomplete or poorly presented manuscripts can create a great deal of frustration and annoyance for editors who probably won’t even bother wasting the time of the reviewers!

This post will discuss 7 steps to the successful publication of your research paper:

- Check whether your research is publication-ready

- Choose an article type

- Choose a journal

- Construct your paper

- Decide the order of authors

- Check and double-check

- Submit your paper

1. Check Whether Your Research Is Publication-Ready

Should you publish your research at all?

If your work holds academic value – of course – a well-written scholarly article could open doors to your research community. However, if you are not yet sure, whether your research is ready for publication, here are some key questions to ask yourself depending on your field of expertise:

- Have you done or found something new and interesting? Something unique?

- Is the work directly related to a current hot topic?

- Have you checked the latest results or research in the field?

- Have you provided solutions to any difficult problems?

- Have the findings been verified?

- Have the appropriate controls been performed if required?

- Are your findings comprehensive?

If the answers to all relevant questions are “yes”, you need to prepare a good, strong manuscript. Remember, a research paper is only useful if it is clearly understood, reproducible and if it is read and used .

2. Choose An Article Type

The first step is to determine which type of paper is most appropriate for your work and what you want to achieve. The following list contains the most important, usually peer-reviewed article types in the natural sciences:

Full original research papers disseminate completed research findings. On average this type of paper is 8-10 pages long, contains five figures, and 25-30 references. Full original research papers are an important part of the process when developing your career.

Review papers present a critical synthesis of a specific research topic. These papers are usually much longer than original papers and will contain numerous references. More often than not, they will be commissioned by journal editors. Reviews present an excellent way to solidify your research career.

Letters, Rapid or Short Communications are often published for the quick and early communication of significant and original advances. They are much shorter than full articles and usually limited in length by the journal. Journals specifically dedicated to short communications or letters are also published in some fields. In these the authors can present short preliminary findings before developing a full-length paper.

3. Choose a Journal

Are you looking for the right place to publish your paper? Find out here whether a De Gruyter journal might be the right fit.

Submit to journals that you already read, that you have a good feel for. If you do so, you will have a better appreciation of both its culture and the requirements of the editors and reviewers.

Other factors to consider are:

- The specific subject area

- The aims and scope of the journal

- The type of manuscript you have written

- The significance of your work

- The reputation of the journal

- The reputation of the editors within the community

- The editorial/review and production speeds of the journal

- The community served by the journal

- The coverage and distribution

- The accessibility ( open access vs. closed access)

4. Construct Your Paper

Each element of a paper has its purpose, so you should make these sections easy to index and search.

Don’t forget that requirements can differ highly per publication, so always make sure to apply a journal’s specific instructions – or guide – for authors to your manuscript, even to the first draft (text layout, paper citation, nomenclature, figures and table, etc.) It will save you time, and the editor’s.

Also, even in these days of Internet-based publishing, space is still at a premium, so be as concise as possible. As a good journalist would say: “Never use three words when one will do!”

Let’s look at the typical structure of a full research paper, but bear in mind certain subject disciplines may have their own specific requirements so check the instructions for authors on the journal’s home page.

4.1 The Title

It’s important to use the title to tell the reader what your paper is all about! You want to attract their attention, a bit like a newspaper headline does. Be specific and to the point. Keep it informative and concise, and avoid jargon and abbreviations (unless they are universally recognized like DNA, for example).

4.2 The Abstract

This could be termed as the “advertisement” for your article. Make it interesting and easily understood without the reader having to read the whole article. Be accurate and specific, and keep it as brief and concise as possible. Some journals (particularly in the medical fields) will ask you to structure the abstract in distinct, labeled sections, which makes it even more accessible.

A clear abstract will influence whether or not your work is considered and whether an editor should invest more time on it or send it for review.

4.3 Keywords

Keywords are used by abstracting and indexing services, such as PubMed and Web of Science. They are the labels of your manuscript, which make it “searchable” online by other researchers.

Include words or phrases (usually 4-8) that are closely related to your topic but not “too niche” for anyone to find them. Make sure to only use established abbreviations. Think about what scientific terms and its variations your potential readers are likely to use and search for. You can also do a test run of your selected keywords in one of the common academic search engines. Do similar articles to your own appear? Yes? Then that’s a good sign.

4.4 Introduction

This first part of the main text should introduce the problem, as well as any existing solutions you are aware of and the main limitations. Also, state what you hope to achieve with your research.

Do not confuse the introduction with the results, discussion or conclusion.

4.5 Methods

Every research article should include a detailed Methods section (also referred to as “Materials and Methods”) to provide the reader with enough information to be able to judge whether the study is valid and reproducible.

Include detailed information so that a knowledgeable reader can reproduce the experiment. However, use references and supplementary materials to indicate previously published procedures.

4.6 Results

In this section, you will present the essential or primary results of your study. To display them in a comprehensible way, you should use subheadings as well as illustrations such as figures, graphs, tables and photos, as appropriate.

4.7 Discussion

Here you should tell your readers what the results mean .

Do state how the results relate to the study’s aims and hypotheses and how the findings relate to those of other studies. Explain all possible interpretations of your findings and the study’s limitations.

Do not make “grand statements” that are not supported by the data. Also, do not introduce any new results or terms. Moreover, do not ignore work that conflicts or disagrees with your findings. Instead …

Be brave! Address conflicting study results and convince the reader you are the one who is correct.

4.8 Conclusion

Your conclusion isn’t just a summary of what you’ve already written. It should take your paper one step further and answer any unresolved questions.

Sum up what you have shown in your study and indicate possible applications and extensions. The main question your conclusion should answer is: What do my results mean for the research field and my community?

4.9 Acknowledgments and Ethical Statements

It is extremely important to acknowledge anyone who has helped you with your paper, including researchers who supplied materials or reagents (e.g. vectors or antibodies); and anyone who helped with the writing or English, or offered critical comments about the content.

Learn more about academic integrity in our blog post “Scholarly Publication Ethics: 4 Common Mistakes You Want To Avoid” .

Remember to state why people have been acknowledged and ask their permission . Ensure that you acknowledge sources of funding, including any grant or reference numbers.

Furthermore, if you have worked with animals or humans, you need to include information about the ethical approval of your study and, if applicable, whether informed consent was given. Also, state whether you have any competing interests regarding the study (e.g. because of financial or personal relationships.)

4.10 References

The end is in sight, but don’t relax just yet!

De facto, there are often more mistakes in the references than in any other part of the manuscript. It is also one of the most annoying and time-consuming problems for editors.

Remember to cite the main scientific publications on which your work is based. But do not inflate the manuscript with too many references. Avoid excessive – and especially unnecessary – self-citations. Also, avoid excessive citations of publications from the same institute or region.

5. Decide the Order of Authors

In the sciences, the most common way to order the names of the authors is by relative contribution.

Generally, the first author conducts and/or supervises the data analysis and the proper presentation and interpretation of the results. They put the paper together and usually submit the paper to the journal.

Co-authors make intellectual contributions to the data analysis and contribute to data interpretation. They review each paper draft. All of them must be able to present the paper and its results, as well as to defend the implications and discuss study limitations.

Do not leave out authors who should be included or add “gift authors”, i.e. authors who did not contribute significantly.

6. Check and Double-Check

As a final step before submission, ask colleagues to read your work and be constructively critical .

Make sure that the paper is appropriate for the journal – take a last look at their aims and scope. Check if all of the requirements in the instructions for authors are met.

Ensure that the cited literature is balanced. Are the aims, purpose and significance of the results clear?

Conduct a final check for language, either by a native English speaker or an editing service.

7. Submit Your Paper

When you and your co-authors have double-, triple-, quadruple-checked the manuscript: submit it via e-mail or online submission system. Along with your manuscript, submit a cover letter, which highlights the reasons why your paper would appeal to the journal and which ensures that you have received approval of all authors for submission.

It is up to the editors and the peer-reviewers now to provide you with their (ideally constructive and helpful) comments and feedback. Time to take a breather!

If the paper gets rejected, do not despair – it happens to literally everybody. If the journal suggests major or minor revisions, take the chance to provide a thorough response and make improvements as you see fit. If the paper gets accepted, congrats!

It’s now time to get writing and share your hard work – good luck!

If you are interested, check out this related blog post

[Title Image by Nick Morrison via Unsplash]

David Sleeman

David Sleeman worked as Senior Journals Manager in the field of Physical Sciences at De Gruyter.

You might also be interested in

Academia & Publishing

Library Community Gives Back: 2023 Webinar Speakers’ Charity Picks

From error to excellence: embracing mistakes in library practice, the impact of transformative agreements on scholarly publishing, visit our shop.

De Gruyter publishes over 1,300 new book titles each year and more than 750 journals in the humanities, social sciences, medicine, mathematics, engineering, computer sciences, natural sciences, and law.

Pin It on Pinterest

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Writing a scientific paper.

- Writing a lab report

- INTRODUCTION

Writing a "good" results section

Figures and Captions in Lab Reports

"Results Checklist" from: How to Write a Good Scientific Paper. Chris A. Mack. SPIE. 2018.

Additional tips for results sections.

- LITERATURE CITED

- Bibliography of guides to scientific writing and presenting

- Peer Review

- Presentations

- Lab Report Writing Guides on the Web

This is the core of the paper. Don't start the results sections with methods you left out of the Materials and Methods section. You need to give an overall description of the experiments and present the data you found.

- Factual statements supported by evidence. Short and sweet without excess words

- Present representative data rather than endlessly repetitive data

- Discuss variables only if they had an effect (positive or negative)

- Use meaningful statistics

- Avoid redundancy. If it is in the tables or captions you may not need to repeat it

A short article by Dr. Brett Couch and Dr. Deena Wassenberg, Biology Program, University of Minnesota

- Present the results of the paper, in logical order, using tables and graphs as necessary.

- Explain the results and show how they help to answer the research questions posed in the Introduction. Evidence does not explain itself; the results must be presented and then explained.

- Avoid: presenting results that are never discussed; presenting results in chronological order rather than logical order; ignoring results that do not support the conclusions;

- Number tables and figures separately beginning with 1 (i.e. Table 1, Table 2, Figure 1, etc.).

- Do not attempt to evaluate the results in this section. Report only what you found; hold all discussion of the significance of the results for the Discussion section.

- It is not necessary to describe every step of your statistical analyses. Scientists understand all about null hypotheses, rejection rules, and so forth and do not need to be reminded of them. Just say something like, "Honeybees did not use the flowers in proportion to their availability (X2 = 7.9, p<0.05, d.f.= 4, chi-square test)." Likewise, cite tables and figures without describing in detail how the data were manipulated. Explanations of this sort should appear in a legend or caption written on the same page as the figure or table.

- You must refer in the text to each figure or table you include in your paper.

- Tables generally should report summary-level data, such as means ± standard deviations, rather than all your raw data. A long list of all your individual observations will mean much less than a few concise, easy-to-read tables or figures that bring out the main findings of your study.

- Only use a figure (graph) when the data lend themselves to a good visual representation. Avoid using figures that show too many variables or trends at once, because they can be hard to understand.

From: https://writingcenter.gmu.edu/guides/imrad-results-discussion

- << Previous: METHODS

- Next: DISCUSSION >>

- Last Updated: Aug 4, 2023 9:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/scientificwriting

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

The Ultimate Guide to Getting Your Thesis Published in a Journal

7-minute read

- 25th February 2023

Writing your thesis and getting it published are huge accomplishments. However, publishing your thesis in an academic journal is another journey for scholars. Beyond how much hard work, time, and research you invest, having your findings published in a scholarly journal is vital for your reputation as a scholar and also advances research findings within your field.

This guide will walk you through how to make sure your thesis is ready for publication in a journal. We’ll go over how to prepare for pre-publication, how to submit your research, and what to do after acceptance.

Pre-Publication Preparations

Understanding the publishing process.

Ideally, you have already considered what type of publication outlet you want your thesis research to appear in. If not, it’s best to do this so you can tailor your writing and overall presentation to fit that publication outlet’s expectations. When selecting an outlet for your research, consider the following:

● How well will my research fit the journal?

● Are the reputation and quality of this journal high?

● Who is this journal’s readership/audience?

● How long does it take the journal to respond to a submission?

● What’s the journal’s rejection rate?

Once you finish writing, revising, editing, and proofreading your work (which can take months or years), expect the publication process to be an additional three months or so.

Revising Your Thesis

Your thesis will need to be thoroughly revised, reworked, reorganized, and edited before a journal will accept it. Journals have specific requirements for all submissions, so read everything on a journal’s submission requirements page before you submit. Make a checklist of all the requirements to be sure you don’t overlook anything. Failing to meet the submission requirements could result in your paper being rejected.

Areas for Improvement

No doubt, the biggest challenge academics face in this journey is reducing the word count of their thesis to meet journal publication requirements. Remember that the average thesis is between 60,000 and 80,000 words, not including footnotes, appendices, and references. On the other hand, the average academic journal article is 4,000 to 7,000 words. Reducing the number of words this much may seem impossible when you are staring at the year or more of research your thesis required, but remember, many have done this before, and many will do it again. You can do it too. Be patient with the process.

Additional areas of improvement include>

· having to reorganize your thesis to meet the section requirements of the journal you submit to ( abstract, intro , methods, results, and discussion).

· Possibly changing your reference system to match the journal requirements or reducing the number of references.

· Reformatting tables and figures.

· Going through an extensive editing process to make sure everything is in place and ready.

Identifying Potential Publishers

Many options exist for publishing your academic research in a journal. However, along with the many credible and legitimate publishers available online, just as many predatory publishers are out there looking to take advantage of academics. Be sure to always check unfamiliar publishers’ credentials before commencing the process. If in doubt, ask your mentor or peer whether they think the publisher is legitimate, or you can use Think. Check. Submit .

If you need help identifying which journals your research is best suited to, there are many tools to help. Here’s a short list:

○ Elsevier JournalFinder

○ EndNote Matcher

○ Journal/Author Name Estimator (JANE)

○ Publish & Flourish Open Access

· The topics the journal publishes and whether your research will be a good fit.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

· The journal’s audience (whom you want to read your research).

· The types of articles the journal publishes (e.g., reviews, case studies).

· Your personal requirements (e.g., whether you’re willing to wait a long time to see your research published).

Submitting Your Thesis

Now that you have thoroughly prepared, it’s time to submit your thesis for publication. This can also be a long process, depending on peer review feedback.

Preparing Your Submission

Many publishers require you to write and submit a cover letter along with your research. The cover letter is your sales pitch to the journal’s editor. In the letter, you should not only introduce your work but also emphasize why it’s new, important, and worth the journal’s time to publish. Be sure to check the journal’s website to see whether submission requires you to include specific information in your cover letter, such as a list of reviewers.

Whenever you submit your thesis for publication in a journal article, it should be in its “final form” – that is, completely ready for publication. Do not submit your thesis if it has not been thoroughly edited, formatted, and proofread. Specifically, check that you’ve met all the journal-specific requirements to avoid rejection.

Navigating the Peer Review Process

Once you submit your thesis to the journal, it will undergo the peer review process. This process may vary among journals, but in general, peer reviews all address the same points. Once submitted, your paper will go through the relevant editors and offices at the journal, then one or more scholars will peer-review it. They will submit their reviews to the journal, which will use the information in its final decision (to accept or reject your submission).

While many academics wait for an acceptance letter that says “no revisions necessary,” this verdict does not appear very often. Instead, the publisher will likely give you a list of necessary revisions based on peer review feedback (these revisions could be major, minor, or a combination of the two). The purpose of the feedback is to verify and strengthen your research. When you respond to the feedback, keep these tips in mind:

● Always be respectful and polite in your responses, even if you disagree.

● If you do disagree, be prepared to provide supporting evidence.

● Respond to all the comments, questions, and feedback in a clear and organized manner.

● Make sure you have sufficient time to make any changes (e.g., whether you will need to conduct additional experiments).

After Publication

Once the journal accepts your article officially, with no further revisions needed, take a moment to enjoy the fruits of your hard work. After all, having your work appear in a distinguished journal is not an easy feat. Once you’ve finished celebrating, it’s time to promote your work. Here’s how you can do that:

● Connect with other experts online (like their posts, follow them, and comment on their work).

● Email your academic mentors.

● Share your article on social media so others in your field may see your work.

● Add the article to your LinkedIn publications.

● Respond to any comments with a “Thank you.”

Getting your thesis research published in a journal is a long process that goes from reworking your thesis to promoting your article online. Be sure you take your time in the pre-publication process so you don’t have to make lots of revisions. You can do this by thoroughly revising, editing, formatting, and proofreading your article.

During this process, make sure you and your co-authors (if any) are going over one another’s work and having outsiders read it to make sure no comma is out of place.

What are the benefits of getting your thesis published?

Having your thesis published builds your reputation as a scholar in your field. It also means you are contributing to the body of work in your field by promoting research and communication with other scholars.

How long does it typically take to get a thesis published?

Once you have finished writing, revising, editing, formatting, and proofreading your thesis – processes that can add up to months or years of work – publication can take around three months. The exact length of time will depend on the journal you submit your work to and the peer review feedback timeline.

How can I ensure the quality of my thesis when attempting to get it published?

If you want to make sure your thesis is of the highest quality, consider having professionals proofread it before submission (some journals even require submissions to be professionally proofread). Proofed has helped thousands of researchers proofread their theses. Check out our free trial today.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Results

Research results refer to the findings and conclusions derived from a systematic investigation or study conducted to answer a specific question or hypothesis. These results are typically presented in a written report or paper and can include various forms of data such as numerical data, qualitative data, statistics, charts, graphs, and visual aids.

Results Section in Research

The results section of the research paper presents the findings of the study. It is the part of the paper where the researcher reports the data collected during the study and analyzes it to draw conclusions.

In the results section, the researcher should describe the data that was collected, the statistical analysis performed, and the findings of the study. It is important to be objective and not interpret the data in this section. Instead, the researcher should report the data as accurately and objectively as possible.

Structure of Research Results Section

The structure of the research results section can vary depending on the type of research conducted, but in general, it should contain the following components:

- Introduction: The introduction should provide an overview of the study, its aims, and its research questions. It should also briefly explain the methodology used to conduct the study.

- Data presentation : This section presents the data collected during the study. It may include tables, graphs, or other visual aids to help readers better understand the data. The data presented should be organized in a logical and coherent way, with headings and subheadings used to help guide the reader.

- Data analysis: In this section, the data presented in the previous section are analyzed and interpreted. The statistical tests used to analyze the data should be clearly explained, and the results of the tests should be presented in a way that is easy to understand.

- Discussion of results : This section should provide an interpretation of the results of the study, including a discussion of any unexpected findings. The discussion should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Limitations: This section should acknowledge any limitations of the study, such as sample size, data collection methods, or other factors that may have influenced the results.

- Conclusions: The conclusions should summarize the main findings of the study and provide a final interpretation of the results. The conclusions should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Recommendations : This section may provide recommendations for future research based on the study’s findings. It may also suggest practical applications for the study’s results in real-world settings.

Outline of Research Results Section

The following is an outline of the key components typically included in the Results section:

I. Introduction

- A brief overview of the research objectives and hypotheses

- A statement of the research question

II. Descriptive statistics

- Summary statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation) for each variable analyzed

- Frequencies and percentages for categorical variables

III. Inferential statistics

- Results of statistical analyses, including tests of hypotheses

- Tables or figures to display statistical results

IV. Effect sizes and confidence intervals

- Effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d, odds ratio) to quantify the strength of the relationship between variables

- Confidence intervals to estimate the range of plausible values for the effect size

V. Subgroup analyses

- Results of analyses that examined differences between subgroups (e.g., by gender, age, treatment group)

VI. Limitations and assumptions

- Discussion of any limitations of the study and potential sources of bias

- Assumptions made in the statistical analyses

VII. Conclusions

- A summary of the key findings and their implications

- A statement of whether the hypotheses were supported or not

- Suggestions for future research

Example of Research Results Section

An Example of a Research Results Section could be:

- This study sought to examine the relationship between sleep quality and academic performance in college students.

- Hypothesis : College students who report better sleep quality will have higher GPAs than those who report poor sleep quality.

- Methodology : Participants completed a survey about their sleep habits and academic performance.

II. Participants

- Participants were college students (N=200) from a mid-sized public university in the United States.

- The sample was evenly split by gender (50% female, 50% male) and predominantly white (85%).

- Participants were recruited through flyers and online advertisements.

III. Results

- Participants who reported better sleep quality had significantly higher GPAs (M=3.5, SD=0.5) than those who reported poor sleep quality (M=2.9, SD=0.6).

- See Table 1 for a summary of the results.

- Participants who reported consistent sleep schedules had higher GPAs than those with irregular sleep schedules.

IV. Discussion

- The results support the hypothesis that better sleep quality is associated with higher academic performance in college students.

- These findings have implications for college students, as prioritizing sleep could lead to better academic outcomes.

- Limitations of the study include self-reported data and the lack of control for other variables that could impact academic performance.

V. Conclusion

- College students who prioritize sleep may see a positive impact on their academic performance.

- These findings highlight the importance of sleep in academic success.

- Future research could explore interventions to improve sleep quality in college students.

Example of Research Results in Research Paper :

Our study aimed to compare the performance of three different machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Neural Network) in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company. We collected a dataset of 10,000 customer records, with 20 predictor variables and a binary churn outcome variable.

Our analysis revealed that all three algorithms performed well in predicting customer churn, with an overall accuracy of 85%. However, the Random Forest algorithm showed the highest accuracy (88%), followed by the Support Vector Machine (86%) and the Neural Network (84%).

Furthermore, we found that the most important predictor variables for customer churn were monthly charges, contract type, and tenure. Random Forest identified monthly charges as the most important variable, while Support Vector Machine and Neural Network identified contract type as the most important.

Overall, our results suggest that machine learning algorithms can be effective in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company, and that Random Forest is the most accurate algorithm for this task.

Example 3 :

Title : The Impact of Social Media on Body Image and Self-Esteem

Abstract : This study aimed to investigate the relationship between social media use, body image, and self-esteem among young adults. A total of 200 participants were recruited from a university and completed self-report measures of social media use, body image satisfaction, and self-esteem.

Results: The results showed that social media use was significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem. Specifically, participants who reported spending more time on social media platforms had lower levels of body image satisfaction and self-esteem compared to those who reported less social media use. Moreover, the study found that comparing oneself to others on social media was a significant predictor of body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem.

Conclusion : These results suggest that social media use can have negative effects on body image satisfaction and self-esteem among young adults. It is important for individuals to be mindful of their social media use and to recognize the potential negative impact it can have on their mental health. Furthermore, interventions aimed at promoting positive body image and self-esteem should take into account the role of social media in shaping these attitudes and behaviors.

Importance of Research Results

Research results are important for several reasons, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research results can contribute to the advancement of knowledge in a particular field, whether it be in science, technology, medicine, social sciences, or humanities.

- Developing theories: Research results can help to develop or modify existing theories and create new ones.

- Improving practices: Research results can inform and improve practices in various fields, such as education, healthcare, business, and public policy.

- Identifying problems and solutions: Research results can identify problems and provide solutions to complex issues in society, including issues related to health, environment, social justice, and economics.

- Validating claims : Research results can validate or refute claims made by individuals or groups in society, such as politicians, corporations, or activists.

- Providing evidence: Research results can provide evidence to support decision-making, policy-making, and resource allocation in various fields.

How to Write Results in A Research Paper

Here are some general guidelines on how to write results in a research paper:

- Organize the results section: Start by organizing the results section in a logical and coherent manner. Divide the section into subsections if necessary, based on the research questions or hypotheses.

- Present the findings: Present the findings in a clear and concise manner. Use tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data and make the presentation more engaging.

- Describe the data: Describe the data in detail, including the sample size, response rate, and any missing data. Provide relevant descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations, and ranges.

- Interpret the findings: Interpret the findings in light of the research questions or hypotheses. Discuss the implications of the findings and the extent to which they support or contradict existing theories or previous research.

- Discuss the limitations : Discuss the limitations of the study, including any potential sources of bias or confounding factors that may have affected the results.

- Compare the results : Compare the results with those of previous studies or theoretical predictions. Discuss any similarities, differences, or inconsistencies.

- Avoid redundancy: Avoid repeating information that has already been presented in the introduction or methods sections. Instead, focus on presenting new and relevant information.

- Be objective: Be objective in presenting the results, avoiding any personal biases or interpretations.

When to Write Research Results

Here are situations When to Write Research Results”

- After conducting research on the chosen topic and obtaining relevant data, organize the findings in a structured format that accurately represents the information gathered.

- Once the data has been analyzed and interpreted, and conclusions have been drawn, begin the writing process.

- Before starting to write, ensure that the research results adhere to the guidelines and requirements of the intended audience, such as a scientific journal or academic conference.

- Begin by writing an abstract that briefly summarizes the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

- Follow the abstract with an introduction that provides context for the research, explains its significance, and outlines the research question and objectives.

- The next section should be a literature review that provides an overview of existing research on the topic and highlights the gaps in knowledge that the current research seeks to address.

- The methodology section should provide a detailed explanation of the research design, including the sample size, data collection methods, and analytical techniques used.

- Present the research results in a clear and concise manner, using graphs, tables, and figures to illustrate the findings.

- Discuss the implications of the research results, including how they contribute to the existing body of knowledge on the topic and what further research is needed.

- Conclude the paper by summarizing the main findings, reiterating the significance of the research, and offering suggestions for future research.

Purpose of Research Results

The purposes of Research Results are as follows:

- Informing policy and practice: Research results can provide evidence-based information to inform policy decisions, such as in the fields of healthcare, education, and environmental regulation. They can also inform best practices in fields such as business, engineering, and social work.

- Addressing societal problems : Research results can be used to help address societal problems, such as reducing poverty, improving public health, and promoting social justice.

- Generating economic benefits : Research results can lead to the development of new products, services, and technologies that can create economic value and improve quality of life.

- Supporting academic and professional development : Research results can be used to support academic and professional development by providing opportunities for students, researchers, and practitioners to learn about new findings and methodologies in their field.

- Enhancing public understanding: Research results can help to educate the public about important issues and promote scientific literacy, leading to more informed decision-making and better public policy.

- Evaluating interventions: Research results can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, such as treatments, educational programs, and social policies. This can help to identify areas where improvements are needed and guide future interventions.

- Contributing to scientific progress: Research results can contribute to the advancement of science by providing new insights and discoveries that can lead to new theories, methods, and techniques.

- Informing decision-making : Research results can provide decision-makers with the information they need to make informed decisions. This can include decision-making at the individual, organizational, or governmental levels.

- Fostering collaboration : Research results can facilitate collaboration between researchers and practitioners, leading to new partnerships, interdisciplinary approaches, and innovative solutions to complex problems.

Advantages of Research Results

Some Advantages of Research Results are as follows:

- Improved decision-making: Research results can help inform decision-making in various fields, including medicine, business, and government. For example, research on the effectiveness of different treatments for a particular disease can help doctors make informed decisions about the best course of treatment for their patients.

- Innovation : Research results can lead to the development of new technologies, products, and services. For example, research on renewable energy sources can lead to the development of new and more efficient ways to harness renewable energy.

- Economic benefits: Research results can stimulate economic growth by providing new opportunities for businesses and entrepreneurs. For example, research on new materials or manufacturing techniques can lead to the development of new products and processes that can create new jobs and boost economic activity.

- Improved quality of life: Research results can contribute to improving the quality of life for individuals and society as a whole. For example, research on the causes of a particular disease can lead to the development of new treatments and cures, improving the health and well-being of millions of people.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

How to get your research published - hints and tips

With journal submissions increasing year on year, editors review a huge number of research papers, so it is important for your manuscript to stand out for the right reasons. This is an overview of the different factors to consider when writing your research papers and submitting them to journals.

Study design

Thinking about writing up your research is crucial at the study-design stage, before you set sample sizes, select your methods, consider your analyses and request relevant approvals. Things to consider include:

- Is your study telling the ‘whole story’?

- Is there anything missing from your study design that referees might ask for?

- What is different and unique about your study?

- What guidelines should your research conform to and do you need to seek any permissions or approvals (e.g. ethical approval)?

- How many papers will you write from the study and which journals might you send them to?

Selecting a large enough sample size is crucial as no matter how good your paper is, if you have a sample size that is too small to produce significant results, you will find it difficult to publish your findings. Sound methodology is another important aspect of study design. If you are using non-standard methods, you will need to justify them to the referees and editors. You should get feedback from your colleagues to help identify aspects that you might have overlooked; it can help you to avoid mistakes that are difficult to correct once the study is underway.

Resources for authors

There are many free resources available online that give you guidance on study design, paper writing and journal submission:

- ARRIVE guidelines 1 and checklist 2

- CONSORT statement 3

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recommendations (formerly known as the ‘Uniform requirements for manuscripts’) 4

- EASE Toolkit for Authors 5

- The EASE Guidelines for Authors and Translators of Scientific Articles to be Published in English 6 is published in over 20 different languages

- Equator Network 7 has links to many useful resources, including the STROBE statement, 8 STROBE checklists 9 and STARD initiative 10

Writing up research

Editors look for concisely written, interesting papers that have a clear message. They want to understand what you’ve done, why, what you found and what it means in the context of other work. They also want to know the weaknesses, the future directions and applications of your research. Editors like a complete story, so be wary of trying to publish several papers out of one study – publishing one or two high impact papers is preferable to several lower impact papers.

A few further points to consider:

- Display items should be relevant, useful, well put together, and easy to read and understand

- Figures should have accompanying legends that are detailed enough for the figure to stand-alone without referencing the paper

- Discussion section should be interesting, engaging, discuss limitations and outline future directions

- The abstract/summary should be logically structured and concise, highlighting the key aspects of the study and most interesting outcomes

- All published work referred to in the paper should be cited in the reference list, which should be up to date and listed citations must be complete

Get as much feedback as possible from friends and colleagues before submitting your paper. Most journals operate a strict triage system and papers need to ‘stand out’ for the right reasons just to be selected for peer review.

Selecting a journal

Selecting your target journal is an important step; it is a good idea to list candidate journals. In addition to a journal’s impact factor, there are many different metrics used to assess journal impact. Journals indexed in PubMed and listed in Thompson ISI will have a wider reach than those not listed. Remember that newly launched journals will have a time lag of a few years before they are eligible for PubMed indexing or Thompson ISI listing; so if a journal does not have an impact factor or is not indexed in PubMed now, it might be in a few years. If you are considering submitting to a new journal, check whether it has any related journals and what their reputation is, and whether it has a well-known publisher and also see who is on the editorial board.

Additionally, investigate factors such as page charges, publication fees, open access publishing options (and their relative cost), availability of altmetrics data, and whether a journal will archive papers in PubMed Central following the embargo period.

Criteria for selecting a journal

- Journal scope – is your paper relevant to the journal scope?

- Journal audience – is the journal audience appropriate (national or international, general with a broad scope or specialist with a narrow scope)?

- Journal visibility – is the publication listed in Thompson ISI and indexed in PubMed? Does it have a social medial presence?

- Journal impact and reputation – the impact a journal has is not just based on its impact factor but also on its reputation in the scientific/medical community.

- Journal turnaround times – how quick is the peer-review process and how long does it take for an article to be published after acceptance?

- Open access publishing options and costs, and publication charges – does the journal have a page charge?

Submitting to a journal

Before submitting your manuscript, check the journal guidelines and format the paper correctly; check word counts and gather any relevant forms or additional items. Some journals have submission checklists, which can be helpful points of reference.

Use the abstract or summary to ‘sell’ your paper, but do not ‘oversell’ your findings. It is usually the only thing that a referee will see when deciding whether to review your paper, so highlight the important and interesting aspects of your work in a clear and concise way.

Also, ensure that all the relevant permissions and approvals are in place, including copyright permission and check that sections of text are not copied – most journals use plagiarism software to check text against previously published articles. Double-check your paper and remove any notes to your co-authors; you do not want to repeat the infamous mistake made by Culumber et al. 11 “Should we cite the crappy Gabor paper here?”. Most manuscript submission websites allow you to review a manuscript pdf to ensure the files are correct and appear in the right order.

You should list contributions made by each author to the study, and any competing or conflicting interests. Journals have criteria for what constitutes an author and when it is more appropriate to list a contributor in the acknowledgements section. Many journals will ask you to suggest suitable referees to peer review your paper, but avoid suggesting anyone who is a friend, colleague or someone you have worked with. If your study is multidisciplinary or in a subject area that has few experts, it can be difficult for journals to identify referees and doing so could speed up the peer-review process. You should avoid requesting that certain individuals are excluded as reviewers. If you feel strongly that particular people should not be considered as referees, you will need to explain why. Some journals request a submission letter be included with the manuscript; this is an opportunity to explain to the editors and referees why your research is both interesting and important. It is best to keep these letters short and informative.

Handling revisions and rejection

If your paper has been peer reviewed, comments from the referees will likely be sent to you along with the editor’s decision. You may be invited to revise your paper, or you might receive a decision of rejection or acceptance. Before you make any revisions, consider whether they are appropriate for your paper – if you choose not to address a comment, it is important to explain why.

The revisions stage is also an opportunity to check the writing style, grammar and improve your figures and tables. Check whether any relevant studies have been published that did not make it into the first version of the paper, and update your manuscript accordingly. Most journals only give you one chance to make major revisions, so the paper must be in the best shape possible when it is resubmitted and it should be accompanied by a clear rebuttal letter. The rebuttal letter should contain all the comments made by the referees and editors (preferably numbered) with a response inserted below each original comment.

Revised papers will often be reassessed by the same referees that scrutinised the original, and they might feel further changes are required or that the initial comments have not been addressed fully. Some revisions might be too extensive to undertake. In this case, you could submit elsewhere or you might need to undertake further experiments before resubmitting your paper. It is worth discussing your options with the editorial office before making a final decision to withdraw a paper.

If your paper is rejected and you have the referee reports, try to revise the paper in line with any appropriate comments before submitting it elsewhere to improve your chances of acceptance by another journal. The same referees might also be invited to review the paper by a different journal, and it is important that they see an improvement in the manuscript. If your paper is rejected before peer review, it is rare that you will receive detailed comments. If you feel strongly that the decision to reject your paper is wrong, you can appeal. Appeals rarely lead to a change in the decision but will prompt the editor(s) to look at the paper again.

Accepted, what next?

Once your paper is accepted, many journals employ copy-editors to edit papers before publication; you might be sent queries or requests for more information or new versions of figure files. You should respond to these quickly to ensure publication is not delayed. All journals should give you the opportunity to check the proofs of your paper before final publication. This is an important stage and although, ordinarily, only small changes can be made, it is your last chance to make amendments. After this, changes need to be submitted and published as errata or corrigenda.