- Scriptwriting

What is Intertextuality — Definition and Examples

I ntertextuality is an incredibly important concept for writers to understand – but what is intertextuality? We’re going to break down everything there is to know about intertextuality by looking at examples from film, television, literature, and games. By the end, you’ll know how to recognize intertextuality, and institute it in your own works.

Intertextuality Definition

First, let’s define intertextuality.

Intertextuality has something to do with texts. But what is a text? Your first thought might be a text message but we'll focus on a different meaning.

A text is a written or visual work; books, paintings, movies, shows, and games are all texts. Any object that can be "read" — so we can think of the lyrics of a song but also the song itself, which can be analyzed and discussed. But before we jump into our examples, let’s formally go over the intertextuality definition!

INTERTEXTUALITY DEFINITION

What is intertextuality.

Intertextuality is the relationship between texts, i.e., books, movies, plays, songs, games, etc. In other words, it’s anytime one text is referenced in another text. Intertextuality works best when it’s explained explicitly, then later alluded to implicitly. Either way, this technique is a fantastic way to share common references to us and our world. When a show like The Sopranos references The Godfather , suddenly the bridge between our reality and the reality of the show gets shorter. And, so, it can be argued that part of the appeal of bridging that gap is to make a show like The Sopranos more "real."

Types of Intertextuality:

Intertextuality may seem benign by storytelling standards, but it’s actually really important – and we’re going to show you why.

Here’s a great video on this from Nerdwriter1 to get the conversation started.

What is Intertextuality? • Hollywood’s New Currency

Now that we have a basic understanding of this concept, let's go a little deeper. We'll start with the different types and how they work.

Types of Intertextuality

What are the types of intertextuality.

Literary critics love nothing more than making terms for things that don’t really need terms. Intertextuality is no exception. Go around the web and you’ll find more than a dozen “types of intertextuality.”

The truth is: most of them are the same.

We’re going to keep it simple by sticking to three main types.

EXPLICIT INTERTEXTUALITY

Explicit intertextuality is when one text is explicitly replicated, either through a remake, reboot, or plagiarism.

Examples of explicit intertextuality:

- Disney fairy tales: Cinderella , Beauty and the Beast , The Little Mermaid .

- Movie prequels and sequels, such as those from the Star Wars franchise.

IMPLICIT INTERTEXTUALITY

Implicit intertextuality is when one text is implicitly replicated through parody or satire .

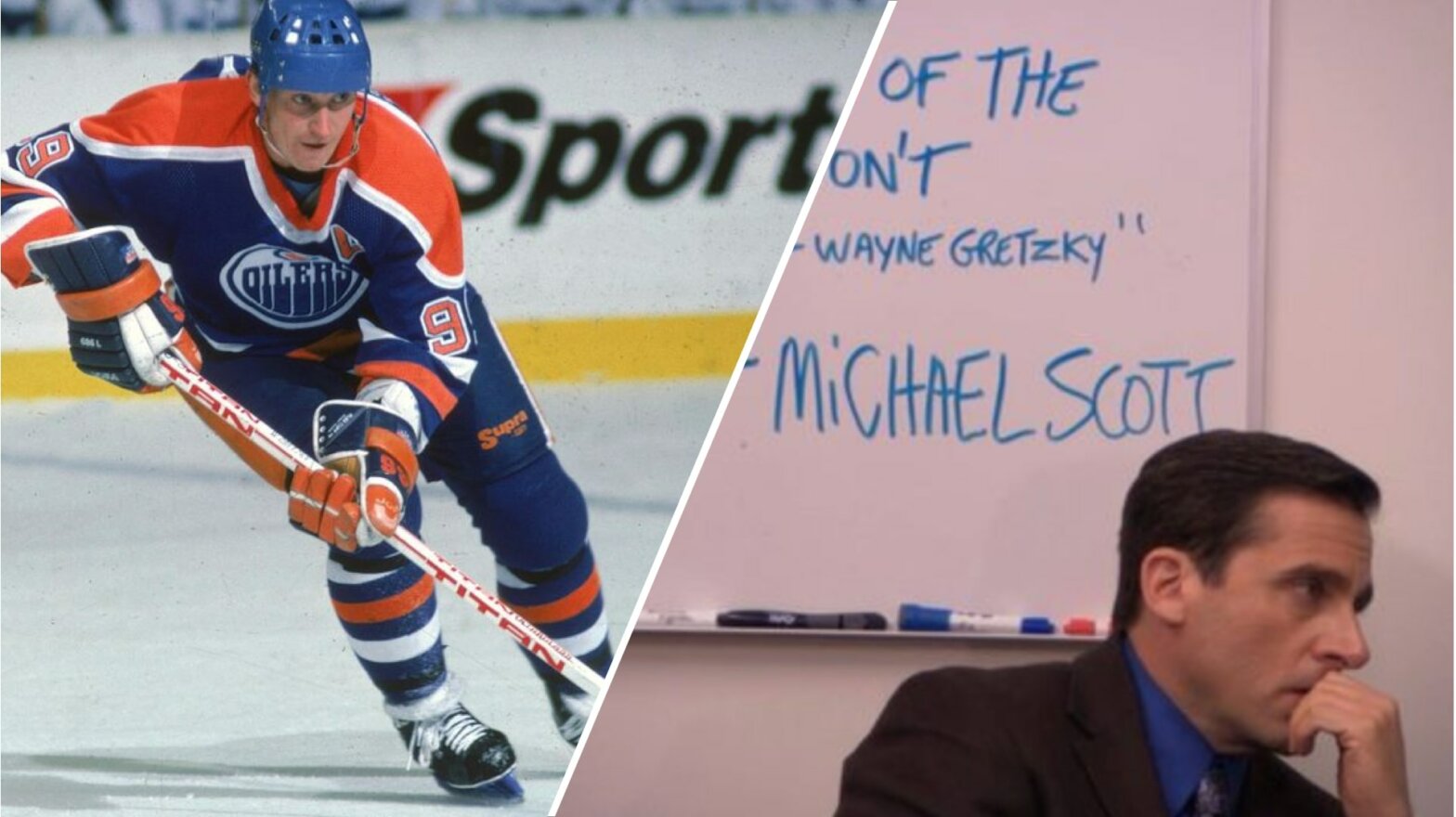

Intertextuality in Film Examples • Spaceballs Parodies Star Wars

Examples of implicit intertextuality:

- Parody movies: Spaceballs , Galaxy Quest , Meet the Spartans .

- Satire movies: The Great Dictator , Hollywood Shuffle .

ALLUSORY INTERTEXTUALITY

Allusory intertextuality is when one text alludes to other texts. This can be done through just about anything, e.g., dialogue, action, plot , imagery , character names, etc.

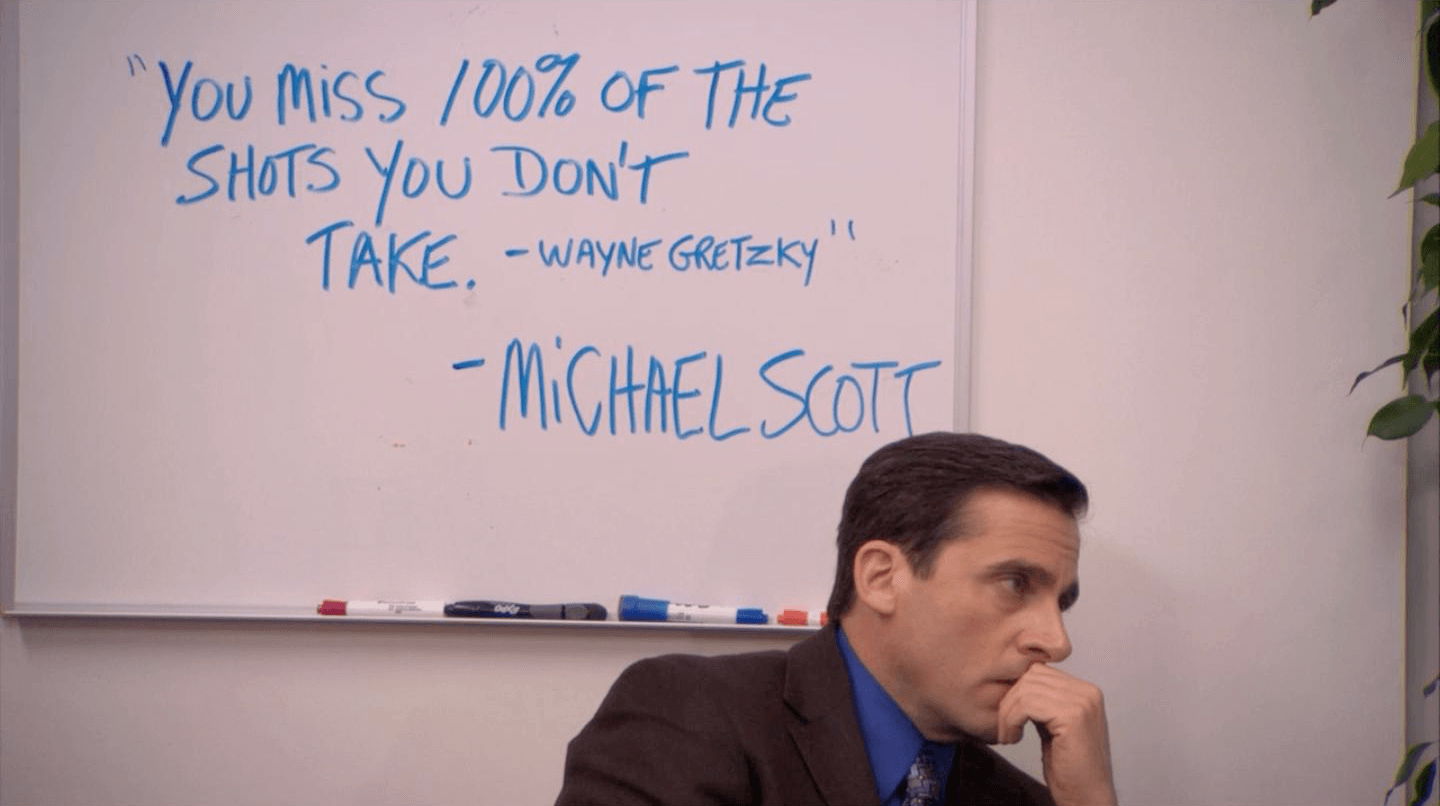

What is Intertextuality? • The Office References a Quote from Wayne Gretzky

Examples of allusion intertextuality:

- Ex Machina : Caleb references the Bhagavad Gita to suggest Nathan is a “destroyer of worlds.”

- Inside Out : one cop tells another “forget it Jake, it’s cloud town” in reference to the ending quote from Chinatown .

- The Office : Michael Scott gives himself credit for crediting the iconic Wayne Gretzky quote, “you miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.”

Intertextuality in Literature Examples

What is intertextuality in literature.

John Milton’s 1667 treatise on the Fall of Man – Paradise Lost – is one of the best intertextual works ever made. Here’s a quick video on Paradise Lost from Course Hero.

Intertextuality Examples in Literature • ‘Paradise Lost’ by John Milton

Paradise Lost takes a text ( The Bible ) and recontextualizes it through a new perspective: Satan’s. The strength of intertextuality lies in how it adds new ideas to the original’s discourse. Seeing as The Bible is one of the most read texts of all-time, it makes sense that other texts reference it intertextually; but Paradise Lost remains perhaps the most impactful of all examples.

TV Referencing Cinema

Intertextuality examples in television.

In a situational sense, intertextuality always works best when the allusion/parody/satire is referenced explicitly before it’s referenced implicitly. I know, it’s complicated.

Let’s look at a perfect example of why this is the case though. This section contains major spoilers for The Sopranos .

Throughout its six-season run, The Sopranos references gangster classics such as The Public Enemy , Goodfellas , and The Godfather . Sopranos ’ fans can probably count a dozen instances of Godfather references off the top of their head – but here’s a refresher course.

Define Intertextuality in TV • Every Godfather Reference in The Sopranos

Perhaps no Godfather reference is more important than the “gun in the bathroom” reference though. In a candid conversation with his father, AJ tells Tony “every time we watch Godfather , when Michael Corleone shoots those guys in the restaurant – those assholes who just tried to kill his dad – you sit there with your fucking bowl of ice cream and you say it’s your favorite scene of all-time.” Here, the writers tell us about an intertextual event.

That’s step one in executing an intertextual allusion.

Step two comes in the very last scene of the show when an unidentified man enters the restaurant, proceeds to the bathroom, followed by the screen cutting to black. We’re able to infer the man is retrieving a gun from the bathroom because of the intertextual reference from earlier. Check out the clip below.

What is Intertextuality? • Watch The Sopranos Ending

The fact that Tony appears on the other side of his favorite scene from The Godfather is ironic .

Intertextual Films

Intertextuality examples in movies.

Woody Allen’s best movies are full of intertextual references – but some of his best references come in Play It Again, Sam , (written by Allen, directed by Herbert Ross); heck, even the title of the movie is an intertextual reference to Casablanca !

Check out the clip below to see how Allen organically integrated intertextual references into the film’s screenplay .

Intertextuality in Film Definition • Play It Again, Sam

This clip is intertextual gold. In under two minutes, Allen expertly deconstructs Italian cinema through the lens of parody, from Le Coppie to La Strada’s denouement at the beach. The thing is: Allen doesn’t presuppose these references with the information needed to understand them, thus limiting their extended appeal.

Intertextual Examples in Games

Intertextuality examples in games.

I’ll keep this one brief because it’s a reference few are probably familiar with. In the video game Yakuza: Like a Dragon , the protagonist expresses that he wants to be a hero , like one from the Dragon Quest video game franchise. Hence, the sub-title “Like a Dragon.”

Here’s the scene where Ichiban lays out his intertextual dreams:

What is Intertextuality? • Intertextuality in Video Games: Yakuza: Like a Dragon

Video games are emerging as a legitimate medium for storytelling; literary techniques included. Yakuza: Like a Dragon contains one of the best-executed examples of intertextuality I’ve seen in gaming to date.

What is Subtext?

Intertextuality is the relationship between texts – but what is subtext? Simply, subtext is the unspoken truths between-the-lines. Up next, we break down subtext, with examples from The Squid and the Whale , Cat on a Hot Tin Roof , and more. By the end, you’ll know what subtext is and how to implement it in your own work!

Up Next: Subtext in Screenwriting →

Write and produce your scripts all in one place..

Write and collaborate on your scripts FREE . Create script breakdowns, sides, schedules, storyboards, call sheets and more.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- The Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets (with FREE Call Sheet Template)

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- TV Script Format 101 — Examples of How to Format a TV Script

- Best Free Musical Movie Scripts Online (with PDF Downloads)

- What is Tragedy — Definition, Examples & Types Explained

- What are the 12 Principles of Animation — Ultimate Guide

- What is Pacing in Writing — And Why It’s So Important

- 0 Pinterest

Literary Devices

Literary devices, terms, and elements, intertextuality, definition of intertextuality.

Intertextuality is the way that one text influences another. This can be a direct borrowing such as a quotation or plagiarism, or slightly more indirect such as parody , pastiche , allusion , or translation. The function and effectiveness of intertextuality can often depend quite a bit on the reader’s prior knowledge and understanding before reading the secondary text; parodies and allusions depend on the reader knowing what is being parodied or alluded to. However, there also are many examples of intertextuality that are either accidental on the part of the author or optional, in the sense that the reader is not required to understand the similarities between texts to fully grasp the significance of the secondary text.

The definition of intertextuality was created by the French semiotician Julia Kristeva in the 1960s. She created the term from the Latin word intertexto , which means “to intermingle while weaving.” Kristeva argued that all works of literature being produced contemporarily are intertextual with the works that came before it. As she stated, “[A]ny text,” she argues, “is constructed of a mosaic of quotations; any text is the absorption and transformation of another.”

Common Examples of Intertextuality

We use different examples of intertextuality frequently in common speech, such as allusions like the following:

- He was lying so obviously, you could almost see his nose growing.

- He’s asking her to the prom. It’s like a happy version of Romeo and Juliet.

- It’s hard being an adult! Peter Pan had the right idea.

The concept of intertextuality can also be expanded to music, film, advertising, and so on in the way that everything produced now is influenced by what came before. References to pop culture in advertising, films that are made from books, and diss tracks in rap can all be considered intertextual, though they are not strictly texts.

Significance of Intertextuality in Literature

As Kristeva wrote, any text can be considered a work of intertextuality because it builds on the structures that existed before it. There are countless examples of authors borrowing from the Bible and from Shakespeare, from titles (William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses and The Sound and the Fury ) to story lines (John Steinbeck’s East of Eden and Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres ). However, Kristeva’s point was more profound than examples of authors knowingly and directly borrowing themes, names, plot lines. Her argument was that all systems of signifying, from the meaning of body language to the structure of a novel, are predicated upon the systems of signifying that came before. A single novel or poem can never be considered independent of the system of meanings in which it relays its message; indeed, each new work of literature transforms and displaces discourse which predated it.

Examples of Intertextuality in Literature

Those who have insinuated that Menard devoted his life to writing a contemporary Quixote besmirch his illustrious memory. Pierre Menard did not want to compose another Quixote, which surely is easy enough—he wanted to compose the Quixote. Nor, surely, need one have to say that his goal was never a mechanical transcription of the original; he had no intention of copying it. His admirable ambition was to produce a number of pages which coincided—word for word and line for line—with those of Miguel de Cervantes.

(“Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote ” by Jorge Borges)

Borges’s short story “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote ” can be considered an aesthetic exploration of intertextuality, and contains intertextuality on multiple levels. The main idea is that an author named Pierre Menard is reconstructing Cervantes’s novel Don Quixote word by word. He is not translating it, not updating it, but instead writing it again. Menard—and, ultimately, Borges—argues that the act of writing the Quixote story again, even word for word, creates a new text. Borges uses intertextuality by assuming the reader understands the importance of Cervantes’s Don Quixote , though the reader does not have to have actually read that novel.

So. The Spear-Danes in days gone by And the kings who ruled them had courage and greatness. We have heard of those princes’ heroic campaigns.

( Beowulf , as translated by Seamus Heaney)

Beowulf is an interesting example of intertextuality because the monster, Grendel, is said to be a descendant of the Biblical figure of Cain. The first Beowulf poet would probably have assumed his reader would have understood this allusion and, indeed, know a great deal about the Bible stories. Our contemporary reading of Beowulf is necessarily intertextual as well because the original poem was written in Old English, which is unintelligible to Modern English speakers. Seamus Heaney used the original text to produce his translation, of course, but his resulting work is his own creation. In the introduction to the new text, Heaney explains many choices he made, including how he decided to translate the first word of the text, “Hwaet!” and “So,” instead of choices other translators made such as “Listen,” “Lo,” and “Attend.”

“Even God can have a preference, can he? Let’s suppose God liked lamb better than vegetables. I think I do myself. Cain brought him a bunch of carrots maybe. And God said, ‘I don’t like this. Try again. Bring me something I like and I’ll set you up alongside your brother.’ But Cain got mad. His feelings were hurt. And when a man’s feelings are hurt he wants to strike at something, and Abel was in the way of his anger.”

( East of Eden by John Steinbeck)

John Steinbeck’s East of Eden is another work of literature based on the story of Biblical story of Cain and Abel. Steinbeck makes this allusion abundantly clear, as proven by the excerpt above. Steinbeck both references the story directly, and also reworks the story through his contemporary characters of Cal and Aron.

CLAUDIUS: Welcome, dear Rosencrantz… (he raises a hand at GUIL while ROS bows – GUIL bows late and hurriedly.)… and Guildenstern. (He raises a hand at ROS while GUIL bows to him – ROS is still straightening up from his previous bow and half way up he bows down again. With his head down, he twists to look at GUIL, who is on the way up.) Moreover that we did much long to see you, The need we have to use you did provoke Our hasty sanding. (ROS and GUIL still adjusting their clothing for CLAUDIUS’s presence.)

( Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead by Tom Stoppard)

Tom Stoppard’s absurdist play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead is an excellent intertextuality example, because Stoppard rewrites Shakespeare’s Hamlet story from the point of view of two previously unimportant characters (note that Shakespeare did not create Hamlet from scratch, but instead based it on a legend of Amleth—more intertextuality). For the most part, Stoppard composes his own lines, but at times lifts text directly from Shakespeare’s version. In a humorous way, the above excerpt contains the exact speech from Claudius to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, yet with Stoppard’s added stage notes. A reader would be required to at least know something about Shakespeare’s Hamlet to understand the purpose of Stoppard’s commentary on it.

After all, to the well-organized mind, death is but the next great adventure.

( Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling)

In a moment of subtle intertextuality, the mentor figure of Dumbledore tells Harry Potter not to pity a dying wizard. The wizard in question has been living for hundreds of years due to the “sorcerer’s stone,” and is not afraid of death. J.K. Rowling is hinting back at the line in J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, who once uttered, “to die would be an awfully big adventure.” There are themes in common between these two fantasy stories of Harry Potter and Peter Pan , yet the reader does not need to pick up on the influence to J.M. Barrie’s work to appreciate J.K. Rowling’s work. J.K. Rowling also borrowed from other sources, such as from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy and from the horrors of real-life Nazi Germany, yet once again the reader can appreciate the story without thinking about its influences.

Test Your Knowledge of Intertextuality

1. Which of the following statements is the best intertextuality definition? A. The relationship between texts. B. Allusions from one text to another. C. The translation of a text into a different language.

2. Which of the following would not be an example of intertextuality? A. A translation of one work into a different language. B. A poetic homage to an earlier writer by adopting that writer’s theme and tone. C. The main characters of two unrelated works coincidentally both named Bob.

3. Which of the following statements is not an example of intertextuality in Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead? A. Tom Stoppard used the same character names as in Shakespeare’s original play. B. The Disney movie The Lion King is also based somewhat on Shakespeare’s Hamlet. C. Parts of the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead are exact quotes from Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Intertextuality

Definition of intertextuality.

Intertextuality is a sophisticated literary device making use of a textual reference within some body of text, which reflects again the text used as a reference. Instead of employing referential phrases from different literary works, intertextuality draws upon the concept, rhetoric , or ideology from other writings to be merged in the new text. It may be the retelling of an old story , or the rewriting of popular stories in modern context for instance, James Joyce retells The Odyssey in his very famous novel Ulysses .

Difference Between Intertextuality and Allusion

Although both these terms seem similar to each other, they are slightly different in their meanings. An allusion is a brief and concise reference that a writer uses in another narrative without affecting the storyline. Intertextuality, on the other hand, uses the reference of the full story in another text or story as its backbone.

Examples of Intertextuality in Literature

Example #1: wide sargasso sea (by jean rhys).

In his novel, Wide Sargasso Sea , Jean Rhys gathers some events that occurred in Charlotte Bronte ’s Jane Eyre . The purpose is to tell readers an alternative tale. Rhys presents the wife of Mr. Rochester, who played the role of a secondary character in Jane Eyre . Also, the setting of this novel is Jamaica, not England, and the author develops the back-story for his major character. While spinning the novel, Jane Eyre , Rhys gives her interpretation amid the narrative by addressing issues such as the roles of women, colonization, and racism that Bronte did not point out in her novel otherwise.

Example #2: A Tempest (By Aime Cesaire)

Aime Cesaire’s play A Tempest is an adaptation of The Tempest by William Shakespeare . The author parodies Shakespeare’s play from a post-colonial point of view . Cesaire also changes the occupations and races of his characters. For example, he transforms the occupation of Prospero, who was a magician, into a slave-owner, and also changes Ariel into a Mulatto, though he was a spirit. Cesaire, like Rhys, makes use of a famous work of literature, and put a spin on it in order to express the themes of power , slavery, and colonialism.

Example #3: Lord of the Flies (By William Golding)

William Golding , in his novel Lord of the Flies , takes the story implicitly from Treasure Island , written by Robert Louis Stevenson . However, Golding has utilized the concept of adventures , which young boys love to do on the isolated island they were stranded on. He, however, changes the narrative into a cautionary tale, rejecting the glorified stories of Stevenson concerning exploration and swash buckling. Instead, Golding grounds this novel in bitter realism by demonstrating negative implications of savagery and fighting that could take control of human hearts, because characters have lost the idea of civilization.

Example #4: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (By C. S. Lewis)

In this case, C. S. Lewis adapts the idea of Christ’s crucifixion in his fantasy novel, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe . He, very shrewdly, weaves together the religious and entertainment themes for a children’s book. Lewis uses an important event from The New Testament , transforming it into a story about redemption. In doing so, he uses Edmund, a character that betrays his savior, Aslan. Generally, the motive of this theme is to introduce other themes, such as evil actions, losing innocence, and redemption.

Example #5: For Whom the Bell Tolls (By Earnest Hemingway)

In the following example, Hemingway uses intertextuality for the title of his novel. He takes the title of a poem , Meditation XVII , written by John Donne . The excerpt of this poem reads:

“No man is an island … and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls ; it tolls for thee.”

Hemingway not only uses this excerpt for the title of his novel, he also makes use of the idea in the novel, as he clarifies and elaborates the abstract philosophy of Donne by using the concept of the Spanish Civil War. By the end, the novel expands other themes, such as loyalty, love, and camaraderie.

Function of Intertextuality

A majority of writers borrow ideas from previous works to give a layer of meaning to their own works. In fact, when readers read the new text with reflection on another literary work, all related assumptions, effects, and ideas of the other text provide them a different meaning, and changes the technique of interpretation of the original piece. Since readers take influence from other texts, and while reading new texts they sift through archives, this device gives them relevance and clarifies their understanding of the new texts. For writers, intertextuality allows them to open new perspectives and possibilities to construct their stories. Thus, writers may explore a particular ideology in their narrative by discussing recent rhetoric in the original text.

Post navigation

Intertextuality

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Intertextuality refers to the interdependence of texts in relation to one another (as well as to the culture at large). Texts can influence, derive from, parody, reference, quote, contrast with, build on, draw from, or even inspire each other. Intertextuality produces meaning . Knowledge does not exist in a vacuum, and neither does literature.

Influence, Hidden or Explicit

The literary canon is ever-growing. All writers read and are influenced by what they read, even if they write in a genre different than their favorite or most recent reading material. Authors are influenced cumulatively by what they've read, whether or not they explicitly show their influences in their writing or on their characters' sleeves. Sometimes they do want to draw parallels between their work and an inspirational work or influential canon—think fan fiction or homages. Maybe they want to create emphasis or contrast or add layers of meaning through an allusion. In so many ways, literature can be interconnected intertextually, on purpose or not.

Professor Graham Allen credits French theorist Laurent Jenny (particularly in "The Strategy of Forms") for drawing a distinction between "works which are explicitly intertextual—such as imitations , parodies , citations , montages and plagiarisms—and those works in which the intertextual relation is not foregrounded," (Allen 2000).

A central idea of contemporary literary and cultural theory, intertextuality has its origins in 20th-century linguistics , particularly in the work of Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913). The term itself was coined by the Bulgarian-French philosopher and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva in the 1960s.

Examples and Observations

Some say that writers and artists are so deeply influenced by the works they consume that the creation of any completely new work is rendered impossible. "Intertextuality seems such a useful term because it foregrounds notions of relationality, interconnectedness and interdependence in modern cultural life. In the Postmodern epoch, theorists often claim, it is not possible any longer to speak of originality or the uniqueness of the artistic object, be it a painting or novel, since every artistic object is so clearly assembled from bits and pieces of already existent art," (Allen 2000).

Authors Jeanine Plottel and Hanna Charney give more of a glimpse into the full scope of intertextuality in their book, Intertextuality: New Perspectives in Criticism. "Interpretation is shaped by a complex of relationships between the text, the reader, reading, writing, printing, publishing and history: the history that is inscribed in the language of the text and in the history that is carried in the reader's reading. Such a history has been given a name: intertextuality," (Plottel and Charney 1978).

A. S. Byatt on Redeploying Sentences in New Contexts

In The Biographer's Tale, A.S. Byatt broaches the subject of whether intertextuality can be considered plagiarism and raises good points about the historical use of inspiration in other art forms. "Postmodernist ideas about intertextuality and quotation have complicated the simplistic ideas about plagiarism which were in Destry-Schole's day. I myself think that these lifted sentences, in their new contexts , are almost the purest and most beautiful parts of the transmission of scholarship.

I began a collection of them, intending, when my time came, to redeploy them with a difference, catching different light at a different angle. That metaphor is from mosaic-making. One of the things I learned in these weeks of research was that the great makers constantly raided previous works—whether in pebble, or marble, or glass, or silver and gold—for tesserae which they rewrought into new images," (Byatt 2001).

Example of Rhetorical Intertextuality

Intertextuality also appears often in speech, as James Jasinski explains. "[Judith] Still and [Michael] Worton [in Intertextuality: Theories and Practice , 1990] explained that every writer or speaker 'is a reader of texts (in the broadest sense) before s/he is a creator of texts, and therefore the work of art is inevitably shot through with references, quotations, and influences of every kind' (p. 1). For example, we can assume that Geraldine Ferraro, the Democratic congresswoman and vice presidential nominee in 1984, had at some point been exposed to John F. Kennedy's 'Inaugural Address.'

So, we should not have been surprised to see traces of Kennedy's speech in the most important speech of Ferraro's career—her address at the Democratic Convention on July 19, 1984. We saw Kennedy's influence when Ferraro constructed a variation of Kennedy's famous chiasmus , as 'Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country' was transformed into 'The issue is not what America can do for women but what women can do for America,'" (Jasinski 2001).

Two Types of Intertextuality

James Porter, in his article "Intertextuality and the Discourse Community", delineates variations of intertextuality. "We can distinguish between two types of intertextuality: iterability and presupposition . Iterability refers to the 'repeatability' of certain textual fragments, to citation in its broadest sense to include not only explicit allusions, references, and quotations within a discourse , but also unannounced sources and influences, clichés , phrases in the air, and traditions. That is to say, every discourse is composed of 'traces,' pieces of other texts that help constitute its meaning. ...

Presupposition refers to assumptions a text makes about its referent , its readers, and its context—to portions of the text which are read, but which are not explicitly 'there.' ... 'Once upon a time' is a trace rich in rhetorical presupposition, signaling to even the youngest reader the opening of a fictional narrative . Texts not only refer to but in fact contain other texts," (Porter 1986).

- Byatt, A. S. The Biographer's Tale. Vintage, 2001.

- Graham, Allen. Intertextuality . Routledge, 2000.

- Jasinski, James. Sourcebook on Rhetoric . Sage, 2001.

- Plottel, Jeanine Parisier, and Hanna Kurz Charney. Intertextuality: New Perspectives in Criticism . New York Literary Forum, 1978.

- Porter, James E. “Intertextuality and the Discourse Community.” Rhetoric Review , vol. 5, no. 1, 1986, pp. 34–47.

- Definition and Examples of Text in Language Studies

- What is Metadiscourse?

- What Is Foregrounding?

- Context in Language

- The Meaning of Rhetor

- The Difference Between a Speech and Discourse Community

- Semiotics Definition and Examples

- What Is the Second Persona?

- Understanding the Use of Language Through Discourse Analysis

- Rhetorical Move

- Oration (Classical Rhetoric)

- Expressive Discourse in Composition

- Rhetorical Analysis Definition and Examples

- Informal Logic

- Coherence in Composition

- Definitions and Discussions of Medieval Rhetoric

- Literary Terms

- When & How to Use Intertextuality

- Definition & Examples

How to Use Intertextuality

How you employ another text in your work depends on what you want to do with it. Do you want to pay homage to a great author like Homer or Shakespeare? Then try re-staging their stories in a new setting. If, on the other hand, you want to spoof those authors, then take whatever is silly or humorous about them and exaggerate it in a parody.

Remember that intertextuality is not limited to texts of the same type . This is important since many of the most sophisticated uses of deliberate intertextuality are those that cut across different mediums and styles . For example, have you ever tried to paint a piece of music? Or write a story based on a philosophical idea? Getting inspiration in this way is a great way to include intertextuality in your writing or art.

When to Use Intertextuality

Obviously, your writing and art will be intertextual whether you want them to be or not. Latent intertextuality is inescapable! But when should you employ deliberate intertextuality?

Deliberate intertextuality has a place both in creative writing and formal essays . In creative writing, it’s a great way to get inspiration for stories. You can draw on other authors’ stories and characters , or you can use other art forms to get inspiration. Either way, when you make deliberate references to these other works you are employing intertextuality.

In formal essays, deliberate intertextuality is a key part of the research process. When you cite a source, you are taking a little chunk of someone else’s text and building it into your own argument. Obviously, you want this intertextuality to be deliberate – if it’s latent, then that means you’re not citing your sources, which is very poor form in an essay!

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

39 “Intertextuality”: A Reference Guide on Using Texts to Produce Texts

- Ways Texts “Connect” or Reference Each Other

- How to Reference Completely and Ethically

by Clint Johnson

“Intertextuality” is the term for how the meaning of one text changes when we relate it to another text. It is one way to understand how writing is contingent upon other factors: in this case, how another text influences the way we understand, or struggle to understand, a given text.

Scholars debate the extent and significance of intertextuality in how we understand language. Some literary theorists argue that any text is just a combination of other texts. Julia Kristeva, for example, writes, “Any text is the absorption and transformation of another.”

How you typically experience intertextuality in your reading and writing is likely to be far simpler than such theories suggest. After all, texts combine with other texts all the time to create meaning, and they do so in specific ways. Understanding these ways helps us better understand what we read and better achieve our goals when we write.

WAYS TEXTS “CONNECT” OR REFERENCE EACH OTHER

What it is:.

When one text uses ideas and words of another text.

How to do it:

A quotation is literally copied language from one text that is used in another. The copied words are put within quotation marks to show the language originally comes from another source. The source is also cited.

Why do it:

Quotation is common in many genres because it allows us to adopt others’ language for a variety of purposes. We quote others for their eloquent use of language, or to distance ourselves from statements we need to communicate but do not want to own, or to acknowledge the existence of other perspectives and voices. As a general rule, we only quote when both the words and ideas of a source are valuable to our writing.

Paraphrasing

When one text includes ideas from another text put in new words.

When paraphrasing, a writer uses their own language to communicate an idea found in another text. Paraphrasing does not require quotation marks because the words are not borrowed from another source. Paraphrasing references specific ideas from a text rather than all ideas in the text. The original source is cited.

We paraphrase others to give credit or assign responsibility for ideas and to use others’ identities in our writing. Paraphrasing can also allow us to easily integrate important ideas from other sources into our writing without changing our style. This creates a consistent feel for the reader. As a general rule, we paraphrase whenever we wish to use the ideas of a source but don’t feel that the source’s words add additional value. We might also paraphrase if the source’s words somehow detract from our work, such as if their language is too technical or biased for our purposes.

Summarizing

When one text uses the main ideas of another text in the order they are originally presented. The source is cited.

A summary presents another text’s major ideas in their original order but without minor details. It essentially condenses a text, shrinking it down by communicating only the most important information. To preserve confidence that the writer summarizing the text hasn’t changed the meaning, summaries are typically written in an objective style. Summaries can be various lengths, from as short as a sentence to as long as needed without giving unnecessary detail.

We summarize to give our reader a sense of another text in its entirety, at least in terms of main ideas, in a short time and space. As a general rule, we summarize whenever we wish to demonstrate that we comprehend a text’s overall meaning or when we ask a reader to interact with the text extensively in our writing.

What is it :

An indirect reference to another text.

The writer does not quote, paraphrase, or in other ways explicitly communicate how the text alludes to, or indirectly connects to, what they are writing. Instead, they trust the reader to be able to identify the connection using their own knowledge.

We allude to a text when we are confident our audience is familiar with the text mentioned. As a general rule, we allude when we want our reader to relate their own knowledge to what we are writing. If our readers are not familiar with the text we allude to, we will likely confuse them.

HOW TO REFERENCE COMPLETELY AND ETHICALLY

Attribution.

Specifying who originated a statement, idea, or text, either by authoring or publishing it. Occasionally, we attribute by citing a text’s title.

Writers attribute by including the name of the person or organization that authored the text they are using in their piece. The name of the author of the original text is connected to the language or ideas the writer references. This may take the form of a parenthetical citation, a signal phrase (e.g., according to ), or a speech tag ( John says ). Attribution is routinely combined with quotes, paraphrases, summaries, and more (but not allusion).

Why do it :

We attribute when we want readers to know where a statement or idea comes from or who it belongs to. Attribution allows us to give people credit for their work, to use others’ credibility in our own writing to increase our own authority, and to separate what we say and believe from what others say and believe. As a general rule, we always attribute the first time we reference a text and often again for texts we reference multiple times.

[Find more attributions in the rest of the example sections above.]

Avoid Plagiarism

What plagiarism is:.

Using someone else’s words and/or ideas and, intentionally or unintentionally, passing them off as one’s own.

How NOT to do it:

There are a number of ways to plagiarize, including quoting or paraphrasing without giving credit to the original author, failing to use quotation marks for language taken from other texts, summarizing without attributing, or using someone else’s reasoning or organizational structure as your own. When using exact language from a source, always put that language in quotation marks. Similarly, when using language or ideas from a source, use attribution to give credit to the author of the text. At Salt Lake Community College we stress that writers should never plagiarize intentionally and must be willing to correct unintentional plagiarism if it occurs by revising their writing.

Why NOT do it:

In the United States and much of the rest of the world, especially the west, words and ideas are considered intellectual property, similar in many regards to physical property. Because language and ideas can be trademarked, much like inventions, using them without obeying fair-use rules is considered theft. Plagiarism is a dishonest act and is considered a form of cheating in the academic and professional worlds. While plagiarism is a serious academic offense for which a student may fail an assignment or class, unintentional plagiarism will usually be met with correction and instruction on how to ethically and effectively reference other texts. Intentional plagiarism is cheating and will not be tolerated.

Works Cited

Dalton, Kathleen. “Theodore Roosevelt: The Making of a Progressive Reformer.” History Now, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/politics-reform/essays/theodore-roosevelt-making-progressive-reformer

Golodryga, Brianna. “‘No More Backbone Than a Chocolate Eclair’: The Best Political Insults of All Time.” The Huffington Post , 2 Nov. 2016, www.huffingtonpost.com/bianna-‘golodryga/no-more-backbone-than-a-c_b_12774594.html

Kristeva, Julia. The Kristeva Reader . Edited by Toril Moi. Columbia University Press, 1986.

“Theodore Roosevelt Quotes.” Brainyquote, n.d., www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/t/theodorero122699.html

Essentials for ENGL-121 Copyright © 2016 by David Buck is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- African Literatures

- Asian Literatures

- British and Irish Literatures

- Latin American and Caribbean Literatures

- North American Literatures

- Oceanic Literatures

- Slavic and Eastern European Literatures

- West Asian Literatures, including Middle East

- Western European Literatures

- Ancient Literatures (before 500)

- Middle Ages and Renaissance (500-1600)

- Enlightenment and Early Modern (1600-1800)

- 19th Century (1800-1900)

- 20th and 21st Century (1900-present)

- Children’s Literature

- Cultural Studies

- Film, TV, and Media

- Literary Theory

- Non-Fiction and Life Writing

- Print Culture and Digital Humanities

- Theater and Drama

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Intertextuality.

- Graham Allen Graham Allen Department of English, University College Cork

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.1072

- Published online: 23 May 2019

Intertextuality is a concept first outlined in the work of poststructuralist theorists Julia Kristeva and Roland Barthes and refers to the emergence of and understanding of any individual text out of the vast network of discourses and languages that make up culture. No text, in the light of intertextuality, stands alone; all texts have their existence and their meaning in relation to a practically infinite field of prior texts and prior significations. Such a vision of textuality emerges from 20th-century developments in our understanding of what it means to use and to be in language. No speaker creates their language from scratch; all linguistic utterances depend upon the employment and redeployment of already existent utterances. Intertextuality is part, then, of a radical rethinking of human subjectivity and human expression, a rethinking that at its most extreme argues it is language rather than human intention that generates meaning.

Having found expression in the radical texts of early poststructuralism, intertextuality became a popular concept within literary criticism, often reimagined in ways that appear far less skeptical about authorial intentionality. A survey of literary theory and practice from the 1970s onward will show a host of critics and theorists employing the term to foreground formalist, political, psychoanalytical, feminist, postcolonial, postmodernist, and other modes of interpretation and commentary. At times these approaches bring the concept much closer to ideas centered in the humanistic subject, such as influence, allusion, citation, and appropriation, while at other times they continue and extend the deconstruction of traditional models of intention. What all theories and practices of intertextuality seem to share, however, is a need to reimagine the act of reading, given that reading can no longer be confined to the reader’s encounter with a single, stable, inviolable text. Taken together, intertextual theories and practices have demonstrated in a myriad of ways the need to move beyond the

Author—Text—Reader

model to models of reading which, by treating all texts as intertexts, confront the limits of interpretation itself.

- structuralism

- poststructuralism

- deconstruction

- interpretation

- digital culture

- remediation

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Literature. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 28 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.39.149.46]

- 185.39.149.46

Character limit 500 /500

Intertextuality As A Literary Device

by Sophie Novak | 31 comments

Free Book Planning Course! Sign up for our 3-part book planning course and make your book writing easy . It expires soon, though, so don’t wait. Sign up here before the deadline!

Do you borrow phrases and concepts from other works in your own? If yes, then you’re using intertextuality, perhaps even without knowing it.

Though it sounds intimidating at first, it’s quite a simple concept really:

Intertextuality denotes the way in which texts (any text, not just literature) gain meaning through their referencing or evocation of other texts.

Photo by fotologic

What Is Intertextuality?

When writers borrow from previous texts, their work acquires layers of meaning. In addition, when a text is read in the light of another text, all the assumptions and effects of the other text give a new meaning and influence the way of interpreting the original text.

It serves as a subtheme, and reminds us of the double narratives in allegories .

This term was developed by the poststructuralist Julia Kristeva in the 1960s, and since then it’s been widely accepted by postmodern literary critics and theoreticians.

Her invention was a response to Ferdinand de Saussure ’s theory and his claim that signs gain their meaning through structure in a particular text. She opposed his to her own, saying that readers are always influenced by other texts, sifting through their archives, when reading a new one.

In a recent short story I was writing, I included a quote by Turgenev at the beginning, which served as a sum-up of my main premise in the story.

Intertextuality Example:

A famous example of intertextuality in literature is James Joyce’s Ulysses as a retelling of The Odyssey , set in Dublin. Ernest Hemingway used the language of the metaphysical poet John Donne in naming his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Even the Bible is considered an instance of intertextuality, since the New Testament quotes passages from the Old Testament.

Beware of Plagiarism

One thing you need to absolutely remember when evoking a reference to another work is to make it clear it’s a reference. Once intertextuality has gained popularity, there were cases of authors using phrases of other works, without indicating what they are doing. There’s a thin line between using intertextuality as a literary device and plagiarising, even if not intended.

Intertextuality as a Sophisticated Concept

A complex use of intertextuality is considered a sophisticated tool in writing. Rather than referencing phrases from other works, a refined use of intertextuality involves drawing upon an ideology, a concept, or even rhetoric from others.

Thus, you may explore the political ideology in your story by drawing upon the current rhetoric in politics. Alternatively, you may use a text source and explore it further.

Looked at it this way, the popular rewriting of fairy tales in modern contexts can be viewed as a highly cultured use of intertextuality.

To be sure, intertextuality is a powerful writing tool that shouldn’t be overlooked. It opens new possibilities and perspectives for constructing a story.

What other uses of intertextuality can you think of? Have you explored this literary device? Share your thoughts below.

Need more grammar help? My favorite tool that helps find grammar problems and even generates reports to help improve my writing is ProWritingAid . Works with Word, Scrivener, Google Docs, and web browsers. Also, be sure to use my coupon code to get 25 percent off: WritePractice25

Freewrite for fifteen minutes and include a reference (a word, phrase, concept, quotation etc.) of another work in your practice. When you’re done, post it in the comments.

As always, be supportive to the others.

Sophie Novak

Sophie Novak is an ultimate daydreamer and curious soul, who can be found either translating or reading at any time of day. She originally comes from the sunny heart of the Balkans, Macedonia, and currently lives in the UK. You can follow her blog and connect with her on Twitter and Facebook .

31 Comments

“They were able to compose only by bringing themselves to attacks of inspiration, an extinct form of epilepsy.” – Yevgeny Zamyatin in We.

“[Goethe] leaned down, opened the drawer, and found a pile of rotten apples. The smell was so overpowering that he became light-headed. […] Schiller had deliberately let the apples spoil. The aroma, somehow, inspired him, and according to his spouse, he ‘could not live or work without it.'” – Goethe, cited in Odd Type Writers

Inspiration isn’t just a fickle mistress, it’s also an unnatural mental state. It’s an intoxication that disrupts the normal functions of the brain. It’s accompanied by a release of endorphins and dopamine, producing a sense of euphoria and invincibility in the artist and making the whole experience addictive.

Once the effects wear out, the victim is left deflated with a sense of guilty elation. Then, withdrawal kicks in with a bout of “the blues”.

The victim will then actively seek out inspiration through various methods, both rational, like reproducing the setting in which inspiration struck, and irrational, like calling upon the forces of the occult, and everything in between, with various degrees of failure. Others will simply wait for inspiration to strike again, which can take from days to months, and longer.

A more reliable way to get your fix is to work for it. Start creating without inspiration, and it will eventually manifest itself spontaneously. Creation breeds inspiration. More so than the other way around.

Inspiration isn’t all that fickle when you get to know her.

I found your comments very insightful.

‘Creation breeds inspiration’. Amen. It gets easier, once you push through, for sure.

“Nothing is easy.” – Zeddicus Z’ul Zorrander in the Sword of Truth series.

I strode to where Angriz lay. Looking down on him from this position, I noticed what I had missed before: his jaw was unhinged. I squatted down to determine how I might best grab his jaw to fix it. The sight of his massive fangs caused me to swallow hard. They were intimidating. They were triangular and serrated like a shark’s teeth, but on a much larger scale. My fingers were going to get cut pretty bad by them. The worst part was I had no idea how the Bloodtaste worked. He might be overtaken by it once more. I sighed as a line from my favorite book series, “The Sword of Truth”, came to mind; ‘Nothing is ever easy.’

Knowing that nothing could be gained by further delay, I reached out and grasped Angriz by his jaw. The fingers of my right hand went into his mouth over his teeth as I grasped the point of his jawbone. I used my left hand for leverage and guidance and I tugged his jaw outward and swung it back into alignment. I turned the air blue when his razor sharp fangs sliced my fingers open. His jaw went back into place with an audible click and I released the pressure. I took my hand out of his mouth and without thinking, placed the lacerated digits into my own to comfort them. Swearing like a sailor denied shore leave, I got up and went to the packs to get cloth for my fingers.

I wrapped my fingers, not thinking about anything, when a gasping growl gave me a start. I whirled around to find Angriz sitting up with his hands clutching his head.

“By Vashara, my head hurts!” he cried.

I felt a huge grin grow on my face. I strode over to him, speaking as I went. “It is good you’re awake, Angriz!” I said. I lowered my voice so I didn’t wake Dearbhaile.

He turned to look at me, dropping his hands and dropping his jaw. “What has happened to you, Carter?” he whispered.

I blinked in confusion, and followed his eyes to where he was looking. I discovered I was covered in a silvery white fluid. I then remembered being sprayed with Belial’s blood after decapitating the half-demon. That must be what it was.

“That can wait until later, Angriz,” I said. “Right now we have bigger problems.”

“What is going on, Carter?”

“Keeper Dearbhaile is hurt. Come, I’ll show you.”

I lead Angriz to where she lay. I knelt and pointed out the wounds I had noticed from my preliminary examination. The half-dragon growled, eyes flashing, at what had been done to our friend. He squatted down and stared at her injuries.

“They tortured her,” he said without inflection.

“This is more than I know how to heal. Can you do anything?”

“Some. I’ll need your assistance.”

He nodded in agreement. I directed him to gather wood to build a large fire not far from where she lay. I gathered our blankets and placed them near her. After the fire was going, we began with the easy stuff. I had Angriz bring her awake.

“Keeper Dearbhaile,” I said to her. “I need to learn where you are hurt. I need you conscious in order to do so, but you don’t have to speak unless necessary. Nod if you understand me.” A slow nod. “We need to remove your clothing to better examine you for injury.”

She nodded again. I directed Angriz in cutting away her robes. Though we were as gentle as we could be, she cried out from the pain of our movements.

“Carter,” Angriz whispered, “Why do we need her clothing off?”

“Because I can’t look through them to see what injuries might be hidden by her clothes. Can you?”

He shook his head. I turned from him and skimmed my fingers over Keeper Dearbhaile’s body. I began at her skull and went downward, relying on her flinching to tell me where her injuries were. There was no reaction until I touched the area on her right side just beneath her breast. She arched her body, hard, away from my touch. I peered at the area. All I was able to detect was a dark red mark. There didn’t appear to be any bruising, but I wanted to be certain. I pulled Angriz closer and had him to look. I knew his vision was sharper than mine in low light.

That’s a proper use of intertextuality. Well done.

I am not sure if I am doing it right. Please correct me if I misunderstood.

ONE, TWO, START! The annual race has started. This is a 24 hour race among many the members of the club. The person who loses will be served as a slave for an entire day to the club members. Immediately within minutes, we see John Feller running past the rest of the members. In fact, he was an all time Olympic Champion in the 400-yard dash. Everyone else is following behind him, scrubbing along to catch up to him. Within 8 hours, John finished 60% of the race while the close second Gene Jackson is only at 40% completion. Behind Gene, there are other members ranging from 35%-40% completion. As we can see, John definitely is the winner. However, there is no reward for the winner but only punishment for the loser. After another 4 hours, John is at 90% while the rest are at 52-60% completion. There are still 12 hours left in the race and John can clearly finish within a few hours. However, it is already 9:00 PM.

John, feeling powerfully illustrious, decided to stop by and take a quick nap before he continues. Even if he sleep for 4 hours, the rest of the group will only be 70-80% complete. He will still be way ahead of them. So John decided to take a quick nap before he sprints to the finish.

One hour, two hours, three hours, four hours. Like John planned, the group is only at 70-80% completion. Two more hours went by, now the group is at 78-90% with Gene leading the pack. Out of the corner of his eyes, he still see John wresting and turning. Next to him, he saw that John actually took some sleeping pill to help him take a nap. Thinking it would be fun, Gene slipped over and mixed the leftover pills and created an airborne solution. He carefully placed the medication under John’s nostrils, and off he went.

after six more hours went by, everyone had finished the race besides John. Everyone was worried what happened. Another 18 hours went by before we saw John running toward the club. John loudly proclaimed, “WTF, how did you guys finished the race in 18 hours? Did you guys cheat?” It turned out, John didn’t realize a full day has already passed since they started the race. Looks like John is doomed to be slave for the next 24 hours…or the next 6 hours if the club members are nice about it.

Hmmm, I did get confused. Have you included somebody’s text/work in the practice?

I try to make it an analogy to the tortoise and the hair concept. Is that the right way of doing it?

Oh right, now I see. Yeah, of course – there’s no strict use, so you’re pretty free in doing as you wish. Smart, by the way.

“The darkest places in hell are reserved for those who maintain their neutrality in times of moral crisis” –so quoted Dante in his Divine Comedy.

It is a fact, that there are two sides to any coin. And these two sides are not right or wrong, nay…they are the two views, two opinions that two different people, two different societies, two different countries hold, and if you were a stranger to their customs and traditions, you would agree with both of them, perhaps without wanting to.

But it is the opinion that wins (through war or debate) that is declared as the right opinion, the right view. In reality, it may not be so.

Taking sides in a battle does not mean that you agree to the battle, but not taking any sides does mean that you will follow the one who wins, which shows your lack of decision making, your lack of exercising the power which you, quite unknowingly hold.

A single opinion can make a drastic difference, perhaps even a bad one, but a single opinion matters. If it didn’t then there would have much more sorrow and injustice in this world (as if the sorrow and injustice we already have is little!).

Being neutral means being indifferent, not diplomatic, because diplomats have an ulterior motive too. Nay, diplomats are not neutral, never! They prefer not to disclose their deepest thoughts.

It is the person who does not exercise the power he holds effectively, the person who is unsure about his conscience, about his upbringing that fails, and in the fact that he must be taken to the deepest circle of hell (as Dante mentions), there exists no doubt.

Being opinionated does count. Even if the opinion is wrong, believing in the wrong with the right motive can even change the wrong and turn it into the right!

Yes, leadership does take quite a lot of confidence, but a leader has with himself the fellowship of hundreds of followers to boost his confidence. But the true soul is the one that follows the leader only after deciding for himself whether the leader is right. He is the person who trusts his conscience first and then the words of a leader. And if his conscience advises that the leader is wrong, then he stands up for himself, maybe alone and fights against all odds to proclaim his righteousness – that is the true hero.

And then, isn’t it better to have a true enemy rather than a doubtful follower?!

I really like this Saunved, and I tend to agree on the neutrality not being the way to go. Dante can be used quite prolifically. 🙂

Dante really was (and is) an influential figure! I’m reading Inferno right now and the words seem to pierce right through the heart! I’m glad you liked this! 😉

I’ve read it such a long time ago, so you gave me a push to give it another go, perhaps with grown-up and critical eyes this time. 🙂

🙂 I hope I’ll grow up and say the same! 😀

Sophie sat down at her desk, determined to start her new practice of writing every day. She opened a new file on her laptop and created a new folder for daily writing exercises, then set a fresh pad of paper with blue, red and black pens to the right side of her desk, and carefully placed The Elements of Style to the left, on top of her latest copy of Writer’s Digest. She checked her watch. Seven minutes used up. Still eight to go. She removed the tea bag from her cup and paused to smell the apple cinnamon scent and gaze out the window at the tree across the street, just starting to show its fall colours. What should she write? Eight minutes was too short to start on the novel she had always wanted to author. It was too short to write a short story, even. Maybe some brainstorming for tomorrow’s session, or maybe a poem. She could get a start on a poem. She glanced at her watch again. Six minutes. Well, maybe she could find some good writing prompts for the rest of the week. Google, where will you lead today? thewritepractice.com. Sophie navigated to their latest daily prompt, on Intertextuality as a Literary Device, and decided that would be a good place to start, tomorrow.

Very cute! I’ve been intertextualized. 🙂

Thanks! First post 🙂

Glad to have you here.

This was so much fun. Your truth mixed with humor had me chuckling.

I’m glad! Thanks for the feedback.

I think you just invented meta-intertextuality. Hats off to you.

Thanks! By the way, I really enjoyed your perspective on inspiration.

I’ve come across intertextuality before but never knew it had a name! Here’s my effort. (I’ve had Melville’s “Moby Dick” on my mind for months now.)

That shopping trip yesterday gave Lewis a new angle on his wip. Bored housewives, eager for a cup of tea and gossip would be just the backdrop to set up and ignite that elusive scene of the desperate daughter meeting her scheming widowed mother in an upmarket coffee shop. Outside the sea had crashed noisily onto the rocks, falling away from the steel and chrome shopping mall that defied the storm. Its roar muted by the thick layer of glass that made him feel like an uninvolved spectator sitting in a comfortable sitting room watching it on television. They had said this building would turn out to be a white elephant. Who would want to shop with sharp smell of ozone in your nose while the wind snatched at your hair? They say nights when the place has emptied one can see a peg-legged old sea-captain stomping about angrily on the rocks, all the while looking out to the restless sea. What is he hoping to see? No craft would brave a sea whipped into such an angry cauldron. A creature of the deep, perhaps? One large enough to survive this maelstrom? Lewis had found the right amount of conflict for the scene..

Good article, Sophie. One of the problems with intertextuality – at least, in a commercial novel – is that the lay reader is unlikely to detect those buried allusions. Especially if the reader is not steeped in western culture. Kristeva made the point that all creative writing is a ‘mosaic of quotations’. Each carries its own baggage of assumptions and associations. To import those sub-texts into a novel can be great fun but will the average reader ‘get’ them, even at a subliminal level?

That said, biblical and mythic intertexts, in western culture, always pull their weight 🙂

How can someone’s eyes ‘look like coming home’? I never really understood this; until now, of course. How do I explain it? Someone once said that the eyes are a window to the soul, and that is exactly what they are. Windows work both ways. Troubled souls look for comfort through the eyes of one person into another’s. Often they don’t find it in their usual confidantes. But when they find what they’re looking for in the eyes of another, there’s a calmness that washes over those two souls: calm and understanding. When a troubled soul discovered this peace, its last wish is to lose it. Its owner finds themselves constantly thinking of that particular pair of eyes, or windows, and conjuring up their image; often going into detail the richness or depth of the color. A connection is formed. There doesn’t have to be prior emotional connection for someone’s eyes to “look like coming home”. There doesn’t have to be any emotional connection at all. It’s simply the feeling one gets of knowing they can trust someone; along with the urge to share everything with that person, knowing they would listen, encourage you, and understand. But one’s brain knows to keep quiet. It’s good to keep emotions down to a minimum. No one wants to hear it anyway. So the soul uses the eyes to speak. At the same time the other soul uses their eyes to listen. And when the two peoples eyes meet, even for a brief moment, the restless souls relax. These two people are true soulmates. Soulmates don’t have to know the full story. They don’t have to be emotionally connected or even be destined to get married. They are just someone whose very presence seems to brighten the room or whose soul satisfies your own without speaking, and without spending extensive amount of time with them; just by simply looking through that special person’s eyes. Because once your soul shares itself with another, that person does, indeed, become special. ———————————— This is a bit of expository writing. I intertextualized the phrase “your eyes look like coming home” which I’ve heard in various songs on the radio and I kind of just explored the meaning behind it through my writing.

Chin up little girl. Show the world your tear-streaked face and smiling eyes. Let her hear your words and the sobs in between. Tell your story from the beginning to the climax down to the perennially desired denouement. Stand proud in your ripped clothes and mended soul because there is no punch you cannot roll with. Your scars are your cartouche, intricate and permanent.

Look into a mirror, into a still lake or into a murky puddle . it doesn’t matter because the truth is little one , you are beautiful. Put on your white dress and dance to your heart’s content and don your black frock and finally say goodbye . Learn , make blunders , understand , and learn. It’s a vicious cycle indeed.

On days your entire being says “I am tired”, sit on a hammock and sip some tea. Feel your cheeks lift and your soul grow . You hear Veronica Shoffstall written soliloquy loud and clear now ; “And you begin to accept your defeats with your head up and your eyes open with the grace of a woman not the grief of a child.”

‘Sing, Goddess, of the anger of…’ well, not Achilles. I’m not much of an athlete, or a warrior. I suppose I’m more like Paris, but he doesn’t get angry as much as scared. It’s not really singing either, not in the classical sense or the modern one. I never could rhyme. As for goddess, well, the gender of divinity not withstanding, I’m an atheist. So I suppose I can really relate to the anger in the opening words of the Iliad.

Still, anger it is. The same kind of anger as well. I kind of anger at having one you love, one you considered your, taken away from you by someone who decided that they had a better claim to her than you. Anger so deep, so all-consuming that you take to your tent and sulk until the Trojans try to burn your ships and kill your best friend. Ok, well it’s not a perfect analogy, but you get my drift.

My Brisais was not a slave-girl stolen in a raid, but the details are not important. What is important is that she’s gone now. All thanks to him. My Agamemnon is not a king, or a great leader of men. He actually seemed like a perfectly nice guy. Well, she clearly thought so too. Better than me anyway, although that’s not hard. Even so, like Agamemnon, he just strolled in and took what he decided was his, without even consulting me.

Things, I have to confess, were not exactly going well. Our relationship was sailing between a Scylla of not spending enough time together and Charybdis of often fighting when we did spend time together, and I had been finding it increasingly difficult to resist certain harpies who I suppose I’m now at liberty to pursue, but that is a different epic all together. It doesn’t do to mix one’s metaphors; I hear you can do yourself some serious damage if you don’t know what you’re doing.

So, Agamemnon. What do I do? Unlike Achilles, my withdrawal to my tent does not seriously hamper my antagonist’s war effort. As I said, more like Paris. I could confront him, but again, more like Paris, and I would have no Aphrodite to spirit me away as I was about to be defeated, but again, I’m mixing my classical references.

This is some powerful freaking thing that measures the beauty of words with the evanescent bloom of a summer day in the everlasting sunshine of sunsets and marigolds and seems to suggest that life is the final resting place for those who understand the importunate misfortunes and enduring grief of time when long ago we sat on the rocks and watched the sea rise in the late afternoon as the golden fingers of the sun cast their lines over the shadows of passing destinies and left us enthralled with the wonder of friendship in collegial groups that waded in the waves at the ends of the earth and left us full of the tiresome tirades of mad old men drunk with metaphor and cold drafts of beer in the taverns by the small lane where Joyce penned his magnum opus and mused on human frailty and the mutinous revolts of the discontented who disturb the sleep of mankind with dreams of world domination notwithstanding the probability that some future utopia of grace and peace will end with a whimper when a Messianic figure, bent on fate’s dictate, engages in the pursuit of some other paradise, some other murky domain where the insects flit among the daffodils and disease takes its toll on luxuriant hopes of better days wherever those days might lead us onward to the slow drift of time where the cycle of death and rebirth under the tall oaks of Central Park on the outskirts of Fifth Avenue exist not far from President Obama’s new home in Kalorama toward the bleak outcome of ISIS victories in the deserts of the Middle East lurching toward the caliphate longed for by Muslims and other seekers of wisdom and truth, but it can never end, you say, you say with a winsome glance at history and bibliographic data that surrounds us in the library overflowing with books written by the great Irish authors like Connor McGuire and Ronen Connelly who were awarded prizes for their deft insights and loquacious rants that evaporated amid the political campaigns that drearily dwindled before the electorate in the waning days of the Republic while Greek scholars read Plato and Sophocles expressed sorrow o’er the fate of Oedipus and Homer cast his spell over Odysseus while the sirens sang of better days into the dreary nights that hovered over the Gates of Hercules on moonlit evenings in the summer casting magic spells and unfortunate outcomes bemoaned by warriors bent on ransacking Rome within the watchful gaze of Nero who fiddled while Rome burned and led his people to disastrous catastrophes in the decades after Caesar was stabbed to death in the Senate building not far from the graves of Romulus and Remus who were reared by a wolf in the forests outside the city gates in the ancient days that predated even more ancient days and wearied British school boys who had to cope with names like Tiberius and Claudius later made famous by public broadcasting or the BBC after the fall of Richard Nixon who promoted lasting relations with the Chinese Communists and bragged about his support for Section 8 housing as if his past history as an arch conservative under the mentorship of Dwight Eisenhower could ever persuade the masses that Republican politicians cared one wit for the poor suffering immigrants who made their way from Mexican towns on the U.S. border until a great wall was built that would prevent an invasion of migrants and starving antelopes into Texas, all the while relaxing in a bed of roses on the Pedernales where LBJ predicted that no one would ever understand James Joyce’s greatest creation until a District Court in Manhattan declared that Molly Bloom’s narrative of an orgasm did not constitute obscenity under federal law.

I used the phrase “the golden fingers of the sun.” This is an allusion to Homer’s Illiad. Homer repeats the phrase, “the rosy fingers of dawn.”

The dawn goddess Eos was almost always described with rosy fingers (ῥοδοδάκτυλος, rhododáktylos) or rosy forearms (ῥοδόπηχυς, rhodópēkhys) as she opened the gates of heaven for the Sun to rise. In Homer, her saffron-coloured robe is embroidered or woven with flowers; rosy-fingered and with golden arms, she is pictured on Attic vases as a beautiful woman, crowned with a tiara or diadem and with the large white-feathered wings of a bird.

From The Iliad:

Now when Dawn in robe of saffron was hastening from the streams of Oceanus, to bring light to mortals and immortals, Thetis reached the ships with the armor that the god had given her.

— Iliad xix.1

But soon as early Dawn appeared, the rosy-fingered, then gathered the folk about the pyre of glorious Hector.

— Iliad xxiv.776

‘We are the hollow men.’

Haunted by the words of an ancient poet, whose name I could not remember, I stood at the edge of Today and watched the world shiver. Oblivion was coming, second by second… and the earth could do nothing but shiver; a trembling, whimpering orb suspended in space, awaiting its inevitable doom.

‘Shape without form, shade without colour, Paralysed force, gesture without motion;’

I had awaited this time for centuries, staring down on humanity with searching eyes. The end was coming. It had always been coming. And finally it was about to appear. Tomorrow had faded into dust. Yesterday was nothing but a vague memory. And Today was doomed.

‘Between the essence And the descent Falls the Shadow For Thine is the Kingdom’

And suddenly, it was there. The darkness that had been withheld over the ages, unravelling across the trembling blue sphere with hands of merciless ice. I stood aloft from it all, seperate from the fate of the nations. Swiftly, like a shadow leaking across the floor, the darkness seeped across the surface of that wretched planet.

‘This is the way the world ends’

Thick, inky blackness smothered the land and the sea. I could only imaging the view from below. Darkness tumbling down highways, across empty lots and flooding through farmlands. Darkness wrapping itself around the tallest buildings, and coursing into the smallest homes. Darkness, infiltrating everything. Darkness, everywhere.

A sigh, a groan of mourning and agony was lifted from the dying world. It reached my ears and I only turned a blind eye. I had been waiting, and finally the end was here.

Then the darkness lifted, and there was Nothing. A small utterance of something unfamiliar seemed to linger at the back of my mind. But what use was guilt? The deed had been done. Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, all lost in Oblivion and replaced with Nothing. And silently, surely, without exclamation or bravado, it was over. The world had ended.

‘Not with a bang but a whimper.’

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- David Lodge’s Chapter “Intertextuality” in reference to “Maps” (Sabrina) « Literature, Language, and Life - […] https://thewritepractice.com/intertextuality-as-a-literary-device/ […]

- Hello World! | ninabharadwajaplit - […] https://thewritepractice.com/intertextuality-as-a-literary-device/ […]

- 100 Writing Practice Lessons & Exercises - […] Intertextuality As A Literary Device […]

- Intertextuality – The Lion, the Witch & the Wardrobe – Chloe Gay - […] S. (2017).Intertextuality As A Literary Device. [online] The Write Practice. Available at: https://thewritepractice.com/intertextuality-as-a-literary-device/ [22 February, […]

- Intertextual Ripples in the ‘Isle Of The Dead’ – Database Of Earaches - […] Novak, S. (2013, September 30). Intertextuality As A Literary Device. Retrieved March 1, 2018, from https://thewritepractice.com/intertextuality-as-a-literary-device/ […]

- Bibliophile in Techland - […] texts. This a technique known as intertextuality. It is, essentially, a “way in which texts…gain meaning through their referencing…

- horrifyinghorse.jpeg | ohitsjuni - […] Novak, S. (2018). Intertextuality As A Literary Device – The Write Practice. Retrieved from https://thewritepractice.com/intertextuality-as-a-literary-device/ […]

- Past Postmodernism? - […] Novak, S. (2018). Intertextuality As A Literary Device – The Write Practice. Retrieved from https://thewritepractice.com/intertextuality-as-a-literary-device/ […]