2.2 Research Methods

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Recall the 6 Steps of the Scientific Method

- Differentiate between four kinds of research methods: surveys, field research, experiments, and secondary data analysis.

- Explain the appropriateness of specific research approaches for specific topics.

Sociologists examine the social world, see a problem or interesting pattern, and set out to study it. They use research methods to design a study. Planning the research design is a key step in any sociological study. Sociologists generally choose from widely used methods of social investigation: primary source data collection such as survey, participant observation, ethnography, case study, unobtrusive observations, experiment, and secondary data analysis , or use of existing sources. Every research method comes with plusses and minuses, and the topic of study strongly influences which method or methods are put to use. When you are conducting research think about the best way to gather or obtain knowledge about your topic, think of yourself as an architect. An architect needs a blueprint to build a house, as a sociologist your blueprint is your research design including your data collection method.

When entering a particular social environment, a researcher must be careful. There are times to remain anonymous and times to be overt. There are times to conduct interviews and times to simply observe. Some participants need to be thoroughly informed; others should not know they are being observed. A researcher wouldn’t stroll into a crime-ridden neighborhood at midnight, calling out, “Any gang members around?”

Making sociologists’ presence invisible is not always realistic for other reasons. That option is not available to a researcher studying prison behaviors, early education, or the Ku Klux Klan. Researchers can’t just stroll into prisons, kindergarten classrooms, or Klan meetings and unobtrusively observe behaviors or attract attention. In situations like these, other methods are needed. Researchers choose methods that best suit their study topics, protect research participants or subjects, and that fit with their overall approaches to research.

As a research method, a survey collects data from subjects who respond to a series of questions about behaviors and opinions, often in the form of a questionnaire or an interview. The survey is one of the most widely used scientific research methods. The standard survey format allows individuals a level of anonymity in which they can express personal ideas.

At some point, most people in the United States respond to some type of survey. The 2020 U.S. Census is an excellent example of a large-scale survey intended to gather sociological data. Since 1790, United States has conducted a survey consisting of six questions to received demographical data pertaining to residents. The questions pertain to the demographics of the residents who live in the United States. Currently, the Census is received by residents in the United Stated and five territories and consists of 12 questions.

Not all surveys are considered sociological research, however, and many surveys people commonly encounter focus on identifying marketing needs and strategies rather than testing a hypothesis or contributing to social science knowledge. Questions such as, “How many hot dogs do you eat in a month?” or “Were the staff helpful?” are not usually designed as scientific research. The Nielsen Ratings determine the popularity of television programming through scientific market research. However, polls conducted by television programs such as American Idol or So You Think You Can Dance cannot be generalized, because they are administered to an unrepresentative population, a specific show’s audience. You might receive polls through your cell phones or emails, from grocery stores, restaurants, and retail stores. They often provide you incentives for completing the survey.

Sociologists conduct surveys under controlled conditions for specific purposes. Surveys gather different types of information from people. While surveys are not great at capturing the ways people really behave in social situations, they are a great method for discovering how people feel, think, and act—or at least how they say they feel, think, and act. Surveys can track preferences for presidential candidates or reported individual behaviors (such as sleeping, driving, or texting habits) or information such as employment status, income, and education levels.

A survey targets a specific population , people who are the focus of a study, such as college athletes, international students, or teenagers living with type 1 (juvenile-onset) diabetes. Most researchers choose to survey a small sector of the population, or a sample , a manageable number of subjects who represent a larger population. The success of a study depends on how well a population is represented by the sample. In a random sample , every person in a population has the same chance of being chosen for the study. As a result, a Gallup Poll, if conducted as a nationwide random sampling, should be able to provide an accurate estimate of public opinion whether it contacts 2,000 or 10,000 people.

After selecting subjects, the researcher develops a specific plan to ask questions and record responses. It is important to inform subjects of the nature and purpose of the survey up front. If they agree to participate, researchers thank subjects and offer them a chance to see the results of the study if they are interested. The researcher presents the subjects with an instrument, which is a means of gathering the information.

A common instrument is a questionnaire. Subjects often answer a series of closed-ended questions . The researcher might ask yes-or-no or multiple-choice questions, allowing subjects to choose possible responses to each question. This kind of questionnaire collects quantitative data —data in numerical form that can be counted and statistically analyzed. Just count up the number of “yes” and “no” responses or correct answers, and chart them into percentages.

Questionnaires can also ask more complex questions with more complex answers—beyond “yes,” “no,” or checkbox options. These types of inquiries use open-ended questions that require short essay responses. Participants willing to take the time to write those answers might convey personal religious beliefs, political views, goals, or morals. The answers are subjective and vary from person to person. How do you plan to use your college education?

Some topics that investigate internal thought processes are impossible to observe directly and are difficult to discuss honestly in a public forum. People are more likely to share honest answers if they can respond to questions anonymously. This type of personal explanation is qualitative data —conveyed through words. Qualitative information is harder to organize and tabulate. The researcher will end up with a wide range of responses, some of which may be surprising. The benefit of written opinions, though, is the wealth of in-depth material that they provide.

An interview is a one-on-one conversation between the researcher and the subject, and it is a way of conducting surveys on a topic. However, participants are free to respond as they wish, without being limited by predetermined choices. In the back-and-forth conversation of an interview, a researcher can ask for clarification, spend more time on a subtopic, or ask additional questions. In an interview, a subject will ideally feel free to open up and answer questions that are often complex. There are no right or wrong answers. The subject might not even know how to answer the questions honestly.

Questions such as “How does society’s view of alcohol consumption influence your decision whether or not to take your first sip of alcohol?” or “Did you feel that the divorce of your parents would put a social stigma on your family?” involve so many factors that the answers are difficult to categorize. A researcher needs to avoid steering or prompting the subject to respond in a specific way; otherwise, the results will prove to be unreliable. The researcher will also benefit from gaining a subject’s trust, from empathizing or commiserating with a subject, and from listening without judgment.

Surveys often collect both quantitative and qualitative data. For example, a researcher interviewing people who are incarcerated might receive quantitative data, such as demographics – race, age, sex, that can be analyzed statistically. For example, the researcher might discover that 20 percent of incarcerated people are above the age of 50. The researcher might also collect qualitative data, such as why people take advantage of educational opportunities during their sentence and other explanatory information.

The survey can be carried out online, over the phone, by mail, or face-to-face. When researchers collect data outside a laboratory, library, or workplace setting, they are conducting field research, which is our next topic.

Field Research

The work of sociology rarely happens in limited, confined spaces. Rather, sociologists go out into the world. They meet subjects where they live, work, and play. Field research refers to gathering primary data from a natural environment. To conduct field research, the sociologist must be willing to step into new environments and observe, participate, or experience those worlds. In field work, the sociologists, rather than the subjects, are the ones out of their element.

The researcher interacts with or observes people and gathers data along the way. The key point in field research is that it takes place in the subject’s natural environment, whether it’s a coffee shop or tribal village, a homeless shelter or the DMV, a hospital, airport, mall, or beach resort.

While field research often begins in a specific setting , the study’s purpose is to observe specific behaviors in that setting. Field work is optimal for observing how people think and behave. It seeks to understand why they behave that way. However, researchers may struggle to narrow down cause and effect when there are so many variables floating around in a natural environment. And while field research looks for correlation, its small sample size does not allow for establishing a causal relationship between two variables. Indeed, much of the data gathered in sociology do not identify a cause and effect but a correlation .

Sociology in the Real World

Beyoncé and lady gaga as sociological subjects.

Sociologists have studied Lady Gaga and Beyoncé and their impact on music, movies, social media, fan participation, and social equality. In their studies, researchers have used several research methods including secondary analysis, participant observation, and surveys from concert participants.

In their study, Click, Lee & Holiday (2013) interviewed 45 Lady Gaga fans who utilized social media to communicate with the artist. These fans viewed Lady Gaga as a mirror of themselves and a source of inspiration. Like her, they embrace not being a part of mainstream culture. Many of Lady Gaga’s fans are members of the LGBTQ community. They see the “song “Born This Way” as a rallying cry and answer her calls for “Paws Up” with a physical expression of solidarity—outstretched arms and fingers bent and curled to resemble monster claws.”

Sascha Buchanan (2019) made use of participant observation to study the relationship between two fan groups, that of Beyoncé and that of Rihanna. She observed award shows sponsored by iHeartRadio, MTV EMA, and BET that pit one group against another as they competed for Best Fan Army, Biggest Fans, and FANdemonium. Buchanan argues that the media thus sustains a myth of rivalry between the two most commercially successful Black women vocal artists.

Participant Observation

In 2000, a comic writer named Rodney Rothman wanted an insider’s view of white-collar work. He slipped into the sterile, high-rise offices of a New York “dot com” agency. Every day for two weeks, he pretended to work there. His main purpose was simply to see whether anyone would notice him or challenge his presence. No one did. The receptionist greeted him. The employees smiled and said good morning. Rothman was accepted as part of the team. He even went so far as to claim a desk, inform the receptionist of his whereabouts, and attend a meeting. He published an article about his experience in The New Yorker called “My Fake Job” (2000). Later, he was discredited for allegedly fabricating some details of the story and The New Yorker issued an apology. However, Rothman’s entertaining article still offered fascinating descriptions of the inside workings of a “dot com” company and exemplified the lengths to which a writer, or a sociologist, will go to uncover material.

Rothman had conducted a form of study called participant observation , in which researchers join people and participate in a group’s routine activities for the purpose of observing them within that context. This method lets researchers experience a specific aspect of social life. A researcher might go to great lengths to get a firsthand look into a trend, institution, or behavior. A researcher might work as a waitress in a diner, experience homelessness for several weeks, or ride along with police officers as they patrol their regular beat. Often, these researchers try to blend in seamlessly with the population they study, and they may not disclose their true identity or purpose if they feel it would compromise the results of their research.

At the beginning of a field study, researchers might have a question: “What really goes on in the kitchen of the most popular diner on campus?” or “What is it like to be homeless?” Participant observation is a useful method if the researcher wants to explore a certain environment from the inside.

Field researchers simply want to observe and learn. In such a setting, the researcher will be alert and open minded to whatever happens, recording all observations accurately. Soon, as patterns emerge, questions will become more specific, observations will lead to hypotheses, and hypotheses will guide the researcher in analyzing data and generating results.

In a study of small towns in the United States conducted by sociological researchers John S. Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd, the team altered their purpose as they gathered data. They initially planned to focus their study on the role of religion in U.S. towns. As they gathered observations, they realized that the effect of industrialization and urbanization was the more relevant topic of this social group. The Lynds did not change their methods, but they revised the purpose of their study.

This shaped the structure of Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture , their published results (Lynd & Lynd, 1929).

The Lynds were upfront about their mission. The townspeople of Muncie, Indiana, knew why the researchers were in their midst. But some sociologists prefer not to alert people to their presence. The main advantage of covert participant observation is that it allows the researcher access to authentic, natural behaviors of a group’s members. The challenge, however, is gaining access to a setting without disrupting the pattern of others’ behavior. Becoming an inside member of a group, organization, or subculture takes time and effort. Researchers must pretend to be something they are not. The process could involve role playing, making contacts, networking, or applying for a job.

Once inside a group, some researchers spend months or even years pretending to be one of the people they are observing. However, as observers, they cannot get too involved. They must keep their purpose in mind and apply the sociological perspective. That way, they illuminate social patterns that are often unrecognized. Because information gathered during participant observation is mostly qualitative, rather than quantitative, the end results are often descriptive or interpretive. The researcher might present findings in an article or book and describe what he or she witnessed and experienced.

This type of research is what journalist Barbara Ehrenreich conducted for her book Nickel and Dimed . One day over lunch with her editor, Ehrenreich mentioned an idea. How can people exist on minimum-wage work? How do low-income workers get by? she wondered. Someone should do a study . To her surprise, her editor responded, Why don’t you do it?

That’s how Ehrenreich found herself joining the ranks of the working class. For several months, she left her comfortable home and lived and worked among people who lacked, for the most part, higher education and marketable job skills. Undercover, she applied for and worked minimum wage jobs as a waitress, a cleaning woman, a nursing home aide, and a retail chain employee. During her participant observation, she used only her income from those jobs to pay for food, clothing, transportation, and shelter.

She discovered the obvious, that it’s almost impossible to get by on minimum wage work. She also experienced and observed attitudes many middle and upper-class people never think about. She witnessed firsthand the treatment of working class employees. She saw the extreme measures people take to make ends meet and to survive. She described fellow employees who held two or three jobs, worked seven days a week, lived in cars, could not pay to treat chronic health conditions, got randomly fired, submitted to drug tests, and moved in and out of homeless shelters. She brought aspects of that life to light, describing difficult working conditions and the poor treatment that low-wage workers suffer.

The book she wrote upon her return to her real life as a well-paid writer, has been widely read and used in many college classrooms.

Ethnography

Ethnography is the immersion of the researcher in the natural setting of an entire social community to observe and experience their everyday life and culture. The heart of an ethnographic study focuses on how subjects view their own social standing and how they understand themselves in relation to a social group.

An ethnographic study might observe, for example, a small U.S. fishing town, an Inuit community, a village in Thailand, a Buddhist monastery, a private boarding school, or an amusement park. These places all have borders. People live, work, study, or vacation within those borders. People are there for a certain reason and therefore behave in certain ways and respect certain cultural norms. An ethnographer would commit to spending a determined amount of time studying every aspect of the chosen place, taking in as much as possible.

A sociologist studying a tribe in the Amazon might watch the way villagers go about their daily lives and then write a paper about it. To observe a spiritual retreat center, an ethnographer might sign up for a retreat and attend as a guest for an extended stay, observe and record data, and collate the material into results.

Institutional Ethnography

Institutional ethnography is an extension of basic ethnographic research principles that focuses intentionally on everyday concrete social relationships. Developed by Canadian sociologist Dorothy E. Smith (1990), institutional ethnography is often considered a feminist-inspired approach to social analysis and primarily considers women’s experiences within male- dominated societies and power structures. Smith’s work is seen to challenge sociology’s exclusion of women, both academically and in the study of women’s lives (Fenstermaker, n.d.).

Historically, social science research tended to objectify women and ignore their experiences except as viewed from the male perspective. Modern feminists note that describing women, and other marginalized groups, as subordinates helps those in authority maintain their own dominant positions (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada n.d.). Smith’s three major works explored what she called “the conceptual practices of power” and are still considered seminal works in feminist theory and ethnography (Fensternmaker n.d.).

Sociological Research

The making of middletown: a study in modern u.s. culture.

In 1924, a young married couple named Robert and Helen Lynd undertook an unprecedented ethnography: to apply sociological methods to the study of one U.S. city in order to discover what “ordinary” people in the United States did and believed. Choosing Muncie, Indiana (population about 30,000) as their subject, they moved to the small town and lived there for eighteen months.

Ethnographers had been examining other cultures for decades—groups considered minorities or outsiders—like gangs, immigrants, and the poor. But no one had studied the so-called average American.

Recording interviews and using surveys to gather data, the Lynds objectively described what they observed. Researching existing sources, they compared Muncie in 1890 to the Muncie they observed in 1924. Most Muncie adults, they found, had grown up on farms but now lived in homes inside the city. As a result, the Lynds focused their study on the impact of industrialization and urbanization.

They observed that Muncie was divided into business and working class groups. They defined business class as dealing with abstract concepts and symbols, while working class people used tools to create concrete objects. The two classes led different lives with different goals and hopes. However, the Lynds observed, mass production offered both classes the same amenities. Like wealthy families, the working class was now able to own radios, cars, washing machines, telephones, vacuum cleaners, and refrigerators. This was an emerging material reality of the 1920s.

As the Lynds worked, they divided their manuscript into six chapters: Getting a Living, Making a Home, Training the Young, Using Leisure, Engaging in Religious Practices, and Engaging in Community Activities.

When the study was completed, the Lynds encountered a big problem. The Rockefeller Foundation, which had commissioned the book, claimed it was useless and refused to publish it. The Lynds asked if they could seek a publisher themselves.

Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture was not only published in 1929 but also became an instant bestseller, a status unheard of for a sociological study. The book sold out six printings in its first year of publication, and has never gone out of print (Caplow, Hicks, & Wattenberg. 2000).

Nothing like it had ever been done before. Middletown was reviewed on the front page of the New York Times. Readers in the 1920s and 1930s identified with the citizens of Muncie, Indiana, but they were equally fascinated by the sociological methods and the use of scientific data to define ordinary people in the United States. The book was proof that social data was important—and interesting—to the U.S. public.

Sometimes a researcher wants to study one specific person or event. A case study is an in-depth analysis of a single event, situation, or individual. To conduct a case study, a researcher examines existing sources like documents and archival records, conducts interviews, engages in direct observation and even participant observation, if possible.

Researchers might use this method to study a single case of a foster child, drug lord, cancer patient, criminal, or rape victim. However, a major criticism of the case study as a method is that while offering depth on a topic, it does not provide enough evidence to form a generalized conclusion. In other words, it is difficult to make universal claims based on just one person, since one person does not verify a pattern. This is why most sociologists do not use case studies as a primary research method.

However, case studies are useful when the single case is unique. In these instances, a single case study can contribute tremendous insight. For example, a feral child, also called “wild child,” is one who grows up isolated from human beings. Feral children grow up without social contact and language, which are elements crucial to a “civilized” child’s development. These children mimic the behaviors and movements of animals, and often invent their own language. There are only about one hundred cases of “feral children” in the world.

As you may imagine, a feral child is a subject of great interest to researchers. Feral children provide unique information about child development because they have grown up outside of the parameters of “normal” growth and nurturing. And since there are very few feral children, the case study is the most appropriate method for researchers to use in studying the subject.

At age three, a Ukranian girl named Oxana Malaya suffered severe parental neglect. She lived in a shed with dogs, and she ate raw meat and scraps. Five years later, a neighbor called authorities and reported seeing a girl who ran on all fours, barking. Officials brought Oxana into society, where she was cared for and taught some human behaviors, but she never became fully socialized. She has been designated as unable to support herself and now lives in a mental institution (Grice 2011). Case studies like this offer a way for sociologists to collect data that may not be obtained by any other method.

Experiments

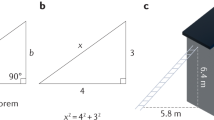

You have probably tested some of your own personal social theories. “If I study at night and review in the morning, I’ll improve my retention skills.” Or, “If I stop drinking soda, I’ll feel better.” Cause and effect. If this, then that. When you test the theory, your results either prove or disprove your hypothesis.

One way researchers test social theories is by conducting an experiment , meaning they investigate relationships to test a hypothesis—a scientific approach.

There are two main types of experiments: lab-based experiments and natural or field experiments. In a lab setting, the research can be controlled so that more data can be recorded in a limited amount of time. In a natural or field- based experiment, the time it takes to gather the data cannot be controlled but the information might be considered more accurate since it was collected without interference or intervention by the researcher.

As a research method, either type of sociological experiment is useful for testing if-then statements: if a particular thing happens (cause), then another particular thing will result (effect). To set up a lab-based experiment, sociologists create artificial situations that allow them to manipulate variables.

Classically, the sociologist selects a set of people with similar characteristics, such as age, class, race, or education. Those people are divided into two groups. One is the experimental group and the other is the control group. The experimental group is exposed to the independent variable(s) and the control group is not. To test the benefits of tutoring, for example, the sociologist might provide tutoring to the experimental group of students but not to the control group. Then both groups would be tested for differences in performance to see if tutoring had an effect on the experimental group of students. As you can imagine, in a case like this, the researcher would not want to jeopardize the accomplishments of either group of students, so the setting would be somewhat artificial. The test would not be for a grade reflected on their permanent record of a student, for example.

And if a researcher told the students they would be observed as part of a study on measuring the effectiveness of tutoring, the students might not behave naturally. This is called the Hawthorne effect —which occurs when people change their behavior because they know they are being watched as part of a study. The Hawthorne effect is unavoidable in some research studies because sociologists have to make the purpose of the study known. Subjects must be aware that they are being observed, and a certain amount of artificiality may result (Sonnenfeld 1985).

A real-life example will help illustrate the process. In 1971, Frances Heussenstamm, a sociology professor at California State University at Los Angeles, had a theory about police prejudice. To test her theory, she conducted research. She chose fifteen students from three ethnic backgrounds: Black, White, and Hispanic. She chose students who routinely drove to and from campus along Los Angeles freeway routes, and who had had perfect driving records for longer than a year.

Next, she placed a Black Panther bumper sticker on each car. That sticker, a representation of a social value, was the independent variable. In the 1970s, the Black Panthers were a revolutionary group actively fighting racism. Heussenstamm asked the students to follow their normal driving patterns. She wanted to see whether seeming support for the Black Panthers would change how these good drivers were treated by the police patrolling the highways. The dependent variable would be the number of traffic stops/citations.

The first arrest, for an incorrect lane change, was made two hours after the experiment began. One participant was pulled over three times in three days. He quit the study. After seventeen days, the fifteen drivers had collected a total of thirty-three traffic citations. The research was halted. The funding to pay traffic fines had run out, and so had the enthusiasm of the participants (Heussenstamm, 1971).

You are here

Perspectives in Social Research Methods and Analysis A Reader for Sociology

- Howard Lune - Hunter College, USA

- Enrique S. Pumar - The Catholic University of America

- Ross Koppel - University of Pennsylvania, USA

- Description

Offering accessible examples showcasing how sociologists conduct research

Comprising 22 reading from both academic journals and books, this text presents the best examples of research methodology in contemporary and classic sociology. The editors organized the readings according to the logic of a research project. Beginning with the research question, to design, data collection and analysis, to application in the world. Each section contains an introduction, serving as a mini-textbook that guides students through the steps of their own research. Discussion questions after each section further compel students to think about the lessons they have learned.

Key Features

- Real research selections show research in action that underscores the relevance for students

- Completely intact articles emphasize how the research is part of the whole sociological enterprise

- By focusing on sociology, the works strengthen the role of the methods course in the major

This book is intended as either a core book or a secondary text, primarily for use in research methods courses in sociology.

The accompanying student study site http://www.sagepub.com/lunestudy includes:

- Additional in-depth discussion questions per chapter

- A section of additional questions for further review

- Additional Web links as helpful resources

- Journal articles related to the readings in the book

- An "In the News" section that has a "real world" link to topics in the book

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

This text does not fit well with the way the course is structured and the level of ability of my students.

Sample Materials & Chapters

Section 1: Where to Begin

Section 2: Research Design

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13 Qualitative analysis

Qualitative analysis is the analysis of qualitative data such as text data from interview transcripts. Unlike quantitative analysis, which is statistics driven and largely independent of the researcher, qualitative analysis is heavily dependent on the researcher’s analytic and integrative skills and personal knowledge of the social context where the data is collected. The emphasis in qualitative analysis is ‘sense making’ or understanding a phenomenon, rather than predicting or explaining. A creative and investigative mindset is needed for qualitative analysis, based on an ethically enlightened and participant-in-context attitude, and a set of analytic strategies. This chapter provides a brief overview of some of these qualitative analysis strategies. Interested readers are referred to more authoritative and detailed references such as Miles and Huberman’s (1984) [1] seminal book on this topic.

Grounded theory

How can you analyse a vast set of qualitative data acquired through participant observation, in-depth interviews, focus groups, narratives of audio/video recordings, or secondary documents? One of these techniques for analysing text data is grounded theory —an inductive technique of interpreting recorded data about a social phenomenon to build theories about that phenomenon. The technique was developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967) [2] in their method of constant comparative analysis of grounded theory research, and further refined by Strauss and Corbin (1990) [3] to further illustrate specific coding techniques—a process of classifying and categorising text data segments into a set of codes (concepts), categories (constructs), and relationships. The interpretations are ‘grounded in’ (or based on) observed empirical data, hence the name. To ensure that the theory is based solely on observed evidence, the grounded theory approach requires that researchers suspend any pre-existing theoretical expectations or biases before data analysis, and let the data dictate the formulation of the theory.

Strauss and Corbin (1998) describe three coding techniques for analysing text data: open, axial, and selective. Open coding is a process aimed at identifying concepts or key ideas that are hidden within textual data, which are potentially related to the phenomenon of interest. The researcher examines the raw textual data line by line to identify discrete events, incidents, ideas, actions, perceptions, and interactions of relevance that are coded as concepts (hence called in vivo codes ). Each concept is linked to specific portions of the text (coding unit) for later validation. Some concepts may be simple, clear, and unambiguous, while others may be complex, ambiguous, and viewed differently by different participants. The coding unit may vary with the concepts being extracted. Simple concepts such as ‘organisational size’ may include just a few words of text, while complex ones such as ‘organizational mission’ may span several pages. Concepts can be named using the researcher’s own naming convention, or standardised labels taken from the research literature. Once a basic set of concepts are identified, these concepts can then be used to code the remainder of the data, while simultaneously looking for new concepts and refining old concepts. While coding, it is important to identify the recognisable characteristics of each concept, such as its size, colour, or level—e.g., high or low—so that similar concepts can be grouped together later . This coding technique is called ‘open’ because the researcher is open to and actively seeking new concepts relevant to the phenomenon of interest.

Next, similar concepts are grouped into higher order categories . While concepts may be context-specific, categories tend to be broad and generalisable, and ultimately evolve into constructs in a grounded theory. Categories are needed to reduce the amount of concepts the researcher must work with and to build a ‘big picture’ of the issues salient to understanding a social phenomenon. Categorisation can be done in phases, by combining concepts into subcategories, and then subcategories into higher order categories. Constructs from the existing literature can be used to name these categories, particularly if the goal of the research is to extend current theories. However, caution must be taken while using existing constructs, as such constructs may bring with them commonly held beliefs and biases. For each category, its characteristics (or properties) and the dimensions of each characteristic should be identified. The dimension represents a value of a characteristic along a continuum. For example, a ‘communication media’ category may have a characteristic called ‘speed’, which can be dimensionalised as fast, medium, or slow . Such categorisation helps differentiate between different kinds of communication media, and enables researchers to identify patterns in the data, such as which communication media is used for which types of tasks.

The second phase of grounded theory is axial coding , where the categories and subcategories are assembled into causal relationships or hypotheses that can tentatively explain the phenomenon of interest. Although distinct from open coding, axial coding can be performed simultaneously with open coding. The relationships between categories may be clearly evident in the data, or may be more subtle and implicit. In the latter instance, researchers may use a coding scheme (often called a ‘coding paradigm’, but different from the paradigms discussed in Chapter 3) to understand which categories represent conditions (the circumstances in which the phenomenon is embedded), actions/interactions (the responses of individuals to events under these conditions), and consequences (the outcomes of actions/interactions). As conditions, actions/interactions, and consequences are identified, theoretical propositions start to emerge, and researchers can start explaining why a phenomenon occurs, under what conditions, and with what consequences.

The third and final phase of grounded theory is selective coding , which involves identifying a central category or a core variable, and systematically and logically relating this central category to other categories. The central category can evolve from existing categories or can be a higher order category that subsumes previously coded categories. New data is selectively sampled to validate the central category, and its relationships to other categories—i.e., the tentative theory. Selective coding limits the range of analysis, and makes it move fast. At the same time, the coder must watch out for other categories that may emerge from the new data that could be related to the phenomenon of interest (open coding), which may lead to further refinement of the initial theory. Hence, open, axial, and selective coding may proceed simultaneously. Coding of new data and theory refinement continues until theoretical saturation is reached—i.e., when additional data does not yield any marginal change in the core categories or the relationships.

The ‘constant comparison’ process implies continuous rearrangement, aggregation, and refinement of categories, relationships, and interpretations based on increasing depth of understanding, and an iterative interplay of four stages of activities: comparing incidents/texts assigned to each category to validate the category), integrating categories and their properties, delimiting the theory by focusing on the core concepts and ignoring less relevant concepts, and writing theory using techniques like memoing, storylining, and diagramming. Having a central category does not necessarily mean that all other categories can be integrated nicely around it. In order to identify key categories that are conditions, action/interactions, and consequences of the core category, Strauss and Corbin (1990) recommend several integration techniques, such as storylining, memoing, or concept mapping, which are discussed here. In storylining , categories and relationships are used to explicate and/or refine a story of the observed phenomenon. Memos are theorised write-ups of ideas about substantive concepts and their theoretically coded relationships as they evolve during ground theory analysis, and are important tools to keep track of and refine ideas that develop during the analysis. Memoing is the process of using these memos to discover patterns and relationships between categories using two-by-two tables, diagrams, or figures, or other illustrative displays. Concept mapping is a graphical representation of concepts and relationships between those concepts—e.g., using boxes and arrows. The major concepts are typically laid out on one or more sheets of paper, blackboards, or using graphical software programs, linked to each other using arrows, and readjusted to best fit the observed data.

After a grounded theory is generated, it must be refined for internal consistency and logic. Researchers must ensure that the central construct has the stated characteristics and dimensions, and if not, the data analysis may be repeated. Researcher must then ensure that the characteristics and dimensions of all categories show variation. For example, if behaviour frequency is one such category, then the data must provide evidence of both frequent performers and infrequent performers of the focal behaviour. Finally, the theory must be validated by comparing it with raw data. If the theory contradicts with observed evidence, the coding process may need to be repeated to reconcile such contradictions or unexplained variations.

Content analysis

Content analysis is the systematic analysis of the content of a text—e.g., who says what, to whom, why, and to what extent and with what effect—in a quantitative or qualitative manner. Content analysis is typically conducted as follows. First, when there are many texts to analyse—e.g., newspaper stories, financial reports, blog postings, online reviews, etc.—the researcher begins by sampling a selected set of texts from the population of texts for analysis. This process is not random, but instead, texts that have more pertinent content should be chosen selectively. Second, the researcher identifies and applies rules to divide each text into segments or ‘chunks’ that can be treated as separate units of analysis. This process is called unitising . For example, assumptions, effects, enablers, and barriers in texts may constitute such units. Third, the researcher constructs and applies one or more concepts to each unitised text segment in a process called coding . For coding purposes, a coding scheme is used based on the themes the researcher is searching for or uncovers as they classify the text. Finally, the coded data is analysed, often both quantitatively and qualitatively, to determine which themes occur most frequently, in what contexts, and how they are related to each other.

A simple type of content analysis is sentiment analysis —a technique used to capture people’s opinion or attitude toward an object, person, or phenomenon. Reading online messages about a political candidate posted on an online forum and classifying each message as positive, negative, or neutral is an example of such an analysis. In this case, each message represents one unit of analysis. This analysis will help identify whether the sample as a whole is positively or negatively disposed, or neutral towards that candidate. Examining the content of online reviews in a similar manner is another example. Though this analysis can be done manually, for very large datasets—e.g., millions of text records—natural language processing and text analytics based software programs are available to automate the coding process, and maintain a record of how people’s sentiments fluctuate with time.

A frequent criticism of content analysis is that it lacks a set of systematic procedures that would allow the analysis to be replicated by other researchers. Schilling (2006) [4] addressed this criticism by organising different content analytic procedures into a spiral model. This model consists of five levels or phases in interpreting text: convert recorded tapes into raw text data or transcripts for content analysis, convert raw data into condensed protocols, convert condensed protocols into a preliminary category system, use the preliminary category system to generate coded protocols, and analyse coded protocols to generate interpretations about the phenomenon of interest.

Content analysis has several limitations. First, the coding process is restricted to the information available in text form. For instance, if a researcher is interested in studying people’s views on capital punishment, but no such archive of text documents is available, then the analysis cannot be done. Second, sampling must be done carefully to avoid sampling bias. For instance, if your population is the published research literature on a given topic, then you have systematically omitted unpublished research or the most recent work that is yet to be published.

Hermeneutic analysis

Hermeneutic analysis is a special type of content analysis where the researcher tries to ‘interpret’ the subjective meaning of a given text within its sociohistoric context. Unlike grounded theory or content analysis—which ignores the context and meaning of text documents during the coding process—hermeneutic analysis is a truly interpretive technique for analysing qualitative data. This method assumes that written texts narrate an author’s experience within a sociohistoric context, and should be interpreted as such within that context. Therefore, the researcher continually iterates between singular interpretation of the text (the part) and a holistic understanding of the context (the whole) to develop a fuller understanding of the phenomenon in its situated context, which German philosopher Martin Heidegger called the hermeneutic circle . The word hermeneutic (singular) refers to one particular method or strand of interpretation.

More generally, hermeneutics is the study of interpretation and the theory and practice of interpretation. Derived from religious studies and linguistics, traditional hermeneutics—such as biblical hermeneutics —refers to the interpretation of written texts, especially in the areas of literature, religion and law—such as the Bible. In the twentieth century, Heidegger suggested that a more direct, non-mediated, and authentic way of understanding social reality is to experience it, rather than simply observe it, and proposed philosophical hermeneutics , where the focus shifted from interpretation to existential understanding. Heidegger argued that texts are the means by which readers can not only read about an author’s experience, but also relive the author’s experiences. Contemporary or modern hermeneutics, developed by Heidegger’s students such as Hans-Georg Gadamer, further examined the limits of written texts for communicating social experiences, and went on to propose a framework of the interpretive process, encompassing all forms of communication, including written, verbal, and non-verbal, and exploring issues that restrict the communicative ability of written texts, such as presuppositions, language structures (e.g., grammar, syntax, etc.), and semiotics—the study of written signs such as symbolism, metaphor, analogy, and sarcasm. The term hermeneutics is sometimes used interchangeably and inaccurately with exegesis , which refers to the interpretation or critical explanation of written text only, and especially religious texts.

Finally, standard software programs, such as ATLAS.ti.5, NVivo, and QDA Miner, can be used to automate coding processes in qualitative research methods. These programs can quickly and efficiently organise, search, sort, and process large volumes of text data using user-defined rules. To guide such automated analysis, a coding schema should be created, specifying the keywords or codes to search for in the text, based on an initial manual examination of sample text data. The schema can be arranged in a hierarchical manner to organise codes into higher-order codes or constructs. The coding schema should be validated using a different sample of texts for accuracy and adequacy. However, if the coding schema is biased or incorrect, the resulting analysis of the entire population of texts may be flawed and non-interpretable. However, software programs cannot decipher the meaning behind certain words or phrases or the context within which these words or phrases are used—such sarcasm or metaphors—which may lead to significant misinterpretation in large scale qualitative analysis.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods . Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. ↵

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . New York: Aldine Pub Co. ↵

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques , Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. ↵

- Schiling, J. (2006). On the pragmatics of qualitative assessment: Designing the process for content analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment , 22(1), 28–37. ↵

Social Science Research: Principles, Methods and Practices (Revised edition) Copyright © 2019 by Anol Bhattacherjee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

Research Methods | Definitions, Types, Examples

Research methods are specific procedures for collecting and analyzing data. Developing your research methods is an integral part of your research design . When planning your methods, there are two key decisions you will make.

First, decide how you will collect data . Your methods depend on what type of data you need to answer your research question :

- Qualitative vs. quantitative : Will your data take the form of words or numbers?

- Primary vs. secondary : Will you collect original data yourself, or will you use data that has already been collected by someone else?

- Descriptive vs. experimental : Will you take measurements of something as it is, or will you perform an experiment?

Second, decide how you will analyze the data .

- For quantitative data, you can use statistical analysis methods to test relationships between variables.

- For qualitative data, you can use methods such as thematic analysis to interpret patterns and meanings in the data.

Table of contents

Methods for collecting data, examples of data collection methods, methods for analyzing data, examples of data analysis methods, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research methods.

Data is the information that you collect for the purposes of answering your research question . The type of data you need depends on the aims of your research.

Qualitative vs. quantitative data

Your choice of qualitative or quantitative data collection depends on the type of knowledge you want to develop.

For questions about ideas, experiences and meanings, or to study something that can’t be described numerically, collect qualitative data .

If you want to develop a more mechanistic understanding of a topic, or your research involves hypothesis testing , collect quantitative data .

You can also take a mixed methods approach , where you use both qualitative and quantitative research methods.

Primary vs. secondary research

Primary research is any original data that you collect yourself for the purposes of answering your research question (e.g. through surveys , observations and experiments ). Secondary research is data that has already been collected by other researchers (e.g. in a government census or previous scientific studies).

If you are exploring a novel research question, you’ll probably need to collect primary data . But if you want to synthesize existing knowledge, analyze historical trends, or identify patterns on a large scale, secondary data might be a better choice.

Descriptive vs. experimental data

In descriptive research , you collect data about your study subject without intervening. The validity of your research will depend on your sampling method .

In experimental research , you systematically intervene in a process and measure the outcome. The validity of your research will depend on your experimental design .

To conduct an experiment, you need to be able to vary your independent variable , precisely measure your dependent variable, and control for confounding variables . If it’s practically and ethically possible, this method is the best choice for answering questions about cause and effect.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Your data analysis methods will depend on the type of data you collect and how you prepare it for analysis.

Data can often be analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For example, survey responses could be analyzed qualitatively by studying the meanings of responses or quantitatively by studying the frequencies of responses.

Qualitative analysis methods

Qualitative analysis is used to understand words, ideas, and experiences. You can use it to interpret data that was collected:

- From open-ended surveys and interviews , literature reviews , case studies , ethnographies , and other sources that use text rather than numbers.

- Using non-probability sampling methods .

Qualitative analysis tends to be quite flexible and relies on the researcher’s judgement, so you have to reflect carefully on your choices and assumptions and be careful to avoid research bias .

Quantitative analysis methods

Quantitative analysis uses numbers and statistics to understand frequencies, averages and correlations (in descriptive studies) or cause-and-effect relationships (in experiments).

You can use quantitative analysis to interpret data that was collected either:

- During an experiment .

- Using probability sampling methods .

Because the data is collected and analyzed in a statistically valid way, the results of quantitative analysis can be easily standardized and shared among researchers.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square test of independence

- Statistical power

- Descriptive statistics

- Degrees of freedom

- Pearson correlation

- Null hypothesis

- Double-blind study

- Case-control study

- Research ethics

- Data collection

- Hypothesis testing

- Structured interviews

Research bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Unconscious bias

- Recall bias

- Halo effect

- Self-serving bias

- Information bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population . Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research. For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

In statistics, sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyze a large amount of readily-available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how it is generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Methodology refers to the overarching strategy and rationale of your research project . It involves studying the methods used in your field and the theories or principles behind them, in order to develop an approach that matches your objectives.

Methods are the specific tools and procedures you use to collect and analyze data (for example, experiments, surveys , and statistical tests ).

In shorter scientific papers, where the aim is to report the findings of a specific study, you might simply describe what you did in a methods section .

In a longer or more complex research project, such as a thesis or dissertation , you will probably include a methodology section , where you explain your approach to answering the research questions and cite relevant sources to support your choice of methods.

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples.

- What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

- Data Collection | Definition, Methods & Examples

More interesting articles

- Between-Subjects Design | Examples, Pros, & Cons

- Cluster Sampling | A Simple Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Confounding Variables | Definition, Examples & Controls

- Construct Validity | Definition, Types, & Examples

- Content Analysis | Guide, Methods & Examples

- Control Groups and Treatment Groups | Uses & Examples

- Control Variables | What Are They & Why Do They Matter?

- Correlation vs. Causation | Difference, Designs & Examples

- Correlational Research | When & How to Use

- Critical Discourse Analysis | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Cross-Sectional Study | Definition, Uses & Examples

- Descriptive Research | Definition, Types, Methods & Examples

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

- Explanatory and Response Variables | Definitions & Examples

- Explanatory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- External Validity | Definition, Types, Threats & Examples

- Extraneous Variables | Examples, Types & Controls

- Guide to Experimental Design | Overview, Steps, & Examples

- How Do You Incorporate an Interview into a Dissertation? | Tips

- How to Do Thematic Analysis | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Examples & Definition

- Independent vs. Dependent Variables | Definition & Examples

- Inductive Reasoning | Types, Examples, Explanation

- Inductive vs. Deductive Research Approach | Steps & Examples

- Internal Validity in Research | Definition, Threats, & Examples

- Internal vs. External Validity | Understanding Differences & Threats

- Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

- Mediator vs. Moderator Variables | Differences & Examples

- Mixed Methods Research | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Multistage Sampling | Introductory Guide & Examples

- Naturalistic Observation | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Operationalization | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Population vs. Sample | Definitions, Differences & Examples

- Primary Research | Definition, Types, & Examples

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research | Differences, Examples & Methods

- Quasi-Experimental Design | Definition, Types & Examples

- Questionnaire Design | Methods, Question Types & Examples

- Random Assignment in Experiments | Introduction & Examples

- Random vs. Systematic Error | Definition & Examples

- Reliability vs. Validity in Research | Difference, Types and Examples

- Reproducibility vs Replicability | Difference & Examples

- Reproducibility vs. Replicability | Difference & Examples

- Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques & Examples

- Semi-Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Simple Random Sampling | Definition, Steps & Examples

- Single, Double, & Triple Blind Study | Definition & Examples

- Stratified Sampling | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Survey Research | Definition, Examples & Methods

- Systematic Review | Definition, Example, & Guide

- Systematic Sampling | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Textual Analysis | Guide, 3 Approaches & Examples

- The 4 Types of Reliability in Research | Definitions & Examples

- The 4 Types of Validity in Research | Definitions & Examples

- Transcribing an Interview | 5 Steps & Transcription Software

- Triangulation in Research | Guide, Types, Examples

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

- Types of Research Designs Compared | Guide & Examples

- Types of Variables in Research & Statistics | Examples

- Unstructured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

- What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

- What Is a Controlled Experiment? | Definitions & Examples

- What Is a Double-Barreled Question?

- What Is a Focus Group? | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- What Is a Likert Scale? | Guide & Examples

- What Is a Prospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

- What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

- What Is Concurrent Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Content Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Convenience Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Convergent Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Criterion Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Data Cleansing? | Definition, Guide & Examples

- What Is Deductive Reasoning? | Explanation & Examples

- What Is Discriminant Validity? | Definition & Example

- What Is Ecological Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Ethnography? | Definition, Guide & Examples

- What Is Face Validity? | Guide, Definition & Examples

- What Is Non-Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples

- What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

- What Is Predictive Validity? | Examples & Definition

- What Is Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples

- What Is Purposive Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Qualitative Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

- What Is Quantitative Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

Unlimited Academic AI-Proofreading

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Social Research – Definition, Types and Methods

Social Research: Definition

Social Research is a method used by social scientists and researchers to learn about people and societies so that they can design products/services that cater to various needs of the people. Different socio-economic groups belonging to different parts of a county think differently. Various aspects of human behavior need to be addressed to understand their thoughts and feedback about the social world, which can be done using Social Research. Any topic can trigger social research – new feature, new market trend or an upgrade in old technology.

Select your respondents

Social Research is conducted by following a systematic plan of action which includes qualitative and quantitative observation methods.

- Qualitative methods rely on direct communication with members of a market, observation, text analysis. The results of this method are focused more on being accurate rather than generalizing to the entire population.

- Quantitative methods use statistical analysis techniques to evaluate data collected via surveys, polls or questionnaires.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

Social Research contains elements of both these methods to analyze a range of social occurrences such as an investigation of historical sites, census of the country, detailed analysis of research conducted to understand reasons for increased reports of molestation in the country etc.

A survey to monitor happiness in a respondent population is one of the most widely used applications of social research. The happiness survey template can be used by researchers an organizations to gauge how happy a respondent is and the things that can be done to increase happiness in that respondent.

Learn more: Public Library Survey Questions + Sample Questionnaire Template

Types of Social Research

There are four main types of Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Research, Primary and Secondary Research.

Qualitative Research: Qualitative Research is defined as a method to collect data via open-ended and conversational discussions, There are five main qualitative research methods- ethnographic research, focus groups, one-on-one online interview, content analysis and case study research. Usually, participants are not taken out of their ecosystem for qualitative data collection to gather information in real-time which helps in building trust. Researchers depend on multiple methods to gather qualitative data for complex issues.

Quantitative Research: Quantitative Research is an extremely informative source of data collection conducted via mediums such as surveys, polls, and questionnaires. The gathered data can be analyzed to conclude numerical or statistical results. There are four distinct quantitative research methods: survey research , correlational research , causal research and experimental research . This research is carried out on a sample that is representative of the target market usually using close-ended questions and data is presented in tables, charts, graphs etc.

For example, A survey can be conducted to understand Climate change awareness among the general population. Such a survey will give in-depth information about people’s perception about climate change and also the behaviors that impact positive behavior. Such a questionnaire will enable the researcher to understand what needs to be done to create more awareness among the public.

Learn More: Climate Change Awareness Survey Template

Primary Research: Primary Research is conducted by the researchers themselves. There are a list of questions that a researcher intends to ask which need to be customized according to the target market. These questions are sent to the respondents via surveys, polls or questionnaires so that analyzing them becomes convenient for the researcher. Since data is collected first-hand, it’s highly accurate according to the requirement of research.

For example: There are tens of thousands of deaths and injuries related to gun violence in the United States. We keep hearing about people carrying weapons attacking general public in the news. There is quite a debate in the American public as to understand if possession of guns is the cause to this. Institutions related to public health or governmental organizations are carrying out studies to find the cause. A lot of policies are also influenced by the opinion of the general population and gun control policies are no different. Hence a gun control questionnaire can be carried out to gather data to understand what people think about gun violence, gun control, factors and effects of possession of firearms. Such a survey can help these institutions to make valid reforms on the basis of the data gathered.

Learn more: Wi-Fi Security Survey Questions + Sample Questionnaire Template

Secondary Research: Secondary Research is a method where information has already been collected by research organizations or marketers. Newspapers, online communities, reports, audio-visual evidence etc. fall under the category of secondary data. After identifying the topic of research and research sources, a researcher can collect existing information available from the noted sources. They can then combine all the information to compare and analyze it to derive conclusions.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Research Questions and Questionnaires

Social Research Methods

Surveys: A survey is conducted by sending a set of pre-decided questions to a sample of individuals from a target market. This will lead to a collection of information and feedback from individuals that belong to various backgrounds, ethnicities, age-groups etc. Surveys can be conducted via online and offline mediums. Due to the improvement in technological mediums and their reach, online mediums have flourished and there is an increase in the number of people depending on online survey software to conduct regular surveys and polls.

There are various types of social research surveys: Longitudinal , Cross-sectional , Correlational Research . Longitudinal and Cross-sectional social research surveys are observational methods while Correlational is a non-experimental research method. Longitudinal social research surveys are conducted with the same sample over a course of time while Cross-sectional surveys are conducted with different samples.

For example: It has been observed in recent times, that there is an increase in the number of divorces, or failed relationships. The number of couples visiting marriage counselors or psychiatrists is increasing. Sometimes it gets tricky to understand what is the cause for a relationship falling apart. A screening process to understand an overview of the relationship can be an easy method. A marriage counselor can use a relationship survey to understand the chemistry in a relationship, the factors that influence the health of a relationship, the challenges faced in a relationship and expectations in a relationship. Such a survey can be very useful to deduce various findings in a patient and treatment can be done accordingly.

Another example for the use of surveys can be to gather information on the awareness of disasters and disaster management programs. A lot of institutions like the UN or the local disaster management team try to keep their communities prepared for disasters. Possessing knowledge about this is crucial in disaster prone areas and is a good type of knowledge that can help everyone. In such a case, a survey can enable these institutions to understand what are the areas that can be promoted more and what regions need what kind of training. Hence a disaster management survey can be conducted to understand public’s knowledge about the impact of disasters on communities, and the measures they undertake to respond to disasters and how can the risk be reduced.

Learn more: NBA Survey Questions + Sample Questionnaire Template

Experiments: An experimental research is conducted by researchers to observe the change in one variable on another, i.e. to establish the cause and effects of a variable. In experiments, there is a theory which needs to be proved or disproved by careful observation and analysis. An efficient experiment will be successful in building a cause-effect relationship while proving, rejecting or disproving a theory. Laboratory and field experiments are preferred by researchers.

Interviews: The technique of garnering opinions and feedback by asking selected questions face-to-face, via telephone or online mediums is called interview research. There are formal and informal interviews – formal interviews are the ones which are organized by the researcher with structured open-ended and closed-ended questions and format while informal interviews are the ones which are more of conversations with the participants and are extremely flexible to collect as much information as possible.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

Examples of interviews in social research are sociological studies that are conducted to understand how religious people are. To this effect, a Church survey can be used by a pastor or priest to understand from the laity the reasons they attend Church and if it meets their spiritual needs.

Observation: In observational research , a researcher is expected to be involved in the daily life of all the participants to understand their routine, their decision-making skills, their capability to handle pressure and their overall likes and dislikes. These factors and recorded and careful observations are made to decide factors such as whether a change in law will impact their lifestyle or whether a new feature will be accepted by individuals.

Learn more:

Quantitative Observation

Qualitative Observation

MORE LIKE THIS

Top 17 UX Research Software for UX Design in 2024

Apr 5, 2024

Healthcare Staff Burnout: What it Is + How To Manage It

Apr 4, 2024

Top 15 Employee Retention Software in 2024

Top 10 Employee Development Software for Talent Growth

Apr 3, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Social Research Methods

Definition of social research methods.

Social research methods are the tools that allow us to ask questions and find answers about the way people live. Imagine being a social detective, using these tools to solve the mysteries of human behavior, relationships, and communities. It’s similar to putting together a puzzle. As you gather more pieces (information), the picture of how we interact and why becomes clearer.

Another definition of social research methods is the strategies that provide us a lens to examine and understand the dynamics of society. Think of it as having a special pair of glasses that help you see the hidden connections and patterns in the everyday actions of people. With these glasses on, you can find answers to big questions, like why certain areas have more crime or what makes people happy with their jobs.

Types of Social Research Methods

There’s a range of techniques to explore various social questions. Each method is like a different detective tool, suited for certain kinds of clues.

- Surveys: You distribute a list of questions to many individuals to quickly gather standardized responses on a topic.

- Interviews: These are one-on-one conversations that provide in-depth understanding of someone’s feelings, thoughts, and experiences.

- Observations: Observations involve watching people and settings without interference to notice behaviors and interactions.

- Experiments: In this method, researchers manipulate certain conditions and observe outcomes to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Content Analysis: This involves systematically examining text or media content to identify patterns, themes, or biases.

Examples of Social Research Methods

Here are some real-life applications of these methods to help illustrate how they work:

- Reading through a celebrity’s Twitter feed: This is content analysis because you delve into their posts to uncover recurring themes and the interests of this person, revealing how public figures influence their followers.

- Standing in the corner of a cafeteria: By watching how individuals interact and choose where to sit, you’re engaging in observation. This can help you map out social networks and how spaces influence social behavior .

- Asking a bunch of high school students: Using a survey, you collect information on their studying habits. This lets you measure patterns and possibly improve educational strategies.

- Chatting with a skateboarder: This interview can unlock detailed knowledge of the skateboarding subculture and attitudes toward risk-taking in sports.

- Seeing if people are more likely to recycle: By conducting an experiment and providing more recycle bins, you can identify what actions influence environmental behavior.

Why is it Important?