Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

The conclusion of a research paper is a crucial section that plays a significant role in the overall impact and effectiveness of your research paper. However, this is also the section that typically receives less attention compared to the introduction and the body of the paper. The conclusion serves to provide a concise summary of the key findings, their significance, their implications, and a sense of closure to the study. Discussing how can the findings be applied in real-world scenarios or inform policy, practice, or decision-making is especially valuable to practitioners and policymakers. The research paper conclusion also provides researchers with clear insights and valuable information for their own work, which they can then build on and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

The research paper conclusion should explain the significance of your findings within the broader context of your field. It restates how your results contribute to the existing body of knowledge and whether they confirm or challenge existing theories or hypotheses. Also, by identifying unanswered questions or areas requiring further investigation, your awareness of the broader research landscape can be demonstrated.

Remember to tailor the research paper conclusion to the specific needs and interests of your intended audience, which may include researchers, practitioners, policymakers, or a combination of these.

Table of Contents

What is a conclusion in a research paper, summarizing conclusion, editorial conclusion, externalizing conclusion, importance of a good research paper conclusion, how to write a conclusion for your research paper, research paper conclusion examples.

- How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

A conclusion in a research paper is the final section where you summarize and wrap up your research, presenting the key findings and insights derived from your study. The research paper conclusion is not the place to introduce new information or data that was not discussed in the main body of the paper. When working on how to conclude a research paper, remember to stick to summarizing and interpreting existing content. The research paper conclusion serves the following purposes: 1

- Warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend specific course(s) of action.

- Restate key ideas to drive home the ultimate point of your research paper.

- Provide a “take-home” message that you want the readers to remember about your study.

Types of conclusions for research papers

In research papers, the conclusion provides closure to the reader. The type of research paper conclusion you choose depends on the nature of your study, your goals, and your target audience. I provide you with three common types of conclusions:

A summarizing conclusion is the most common type of conclusion in research papers. It involves summarizing the main points, reiterating the research question, and restating the significance of the findings. This common type of research paper conclusion is used across different disciplines.

An editorial conclusion is less common but can be used in research papers that are focused on proposing or advocating for a particular viewpoint or policy. It involves presenting a strong editorial or opinion based on the research findings and offering recommendations or calls to action.

An externalizing conclusion is a type of conclusion that extends the research beyond the scope of the paper by suggesting potential future research directions or discussing the broader implications of the findings. This type of conclusion is often used in more theoretical or exploratory research papers.

Align your conclusion’s tone with the rest of your research paper. Start Writing with Paperpal Now!

The conclusion in a research paper serves several important purposes:

- Offers Implications and Recommendations : Your research paper conclusion is an excellent place to discuss the broader implications of your research and suggest potential areas for further study. It’s also an opportunity to offer practical recommendations based on your findings.

- Provides Closure : A good research paper conclusion provides a sense of closure to your paper. It should leave the reader with a feeling that they have reached the end of a well-structured and thought-provoking research project.

- Leaves a Lasting Impression : Writing a well-crafted research paper conclusion leaves a lasting impression on your readers. It’s your final opportunity to leave them with a new idea, a call to action, or a memorable quote.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper is essential to leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s a step-by-step process to help you create and know what to put in the conclusion of a research paper: 2

- Research Statement : Begin your research paper conclusion by restating your research statement. This reminds the reader of the main point you’ve been trying to prove throughout your paper. Keep it concise and clear.

- Key Points : Summarize the main arguments and key points you’ve made in your paper. Avoid introducing new information in the research paper conclusion. Instead, provide a concise overview of what you’ve discussed in the body of your paper.

- Address the Research Questions : If your research paper is based on specific research questions or hypotheses, briefly address whether you’ve answered them or achieved your research goals. Discuss the significance of your findings in this context.

- Significance : Highlight the importance of your research and its relevance in the broader context. Explain why your findings matter and how they contribute to the existing knowledge in your field.

- Implications : Explore the practical or theoretical implications of your research. How might your findings impact future research, policy, or real-world applications? Consider the “so what?” question.

- Future Research : Offer suggestions for future research in your area. What questions or aspects remain unanswered or warrant further investigation? This shows that your work opens the door for future exploration.

- Closing Thought : Conclude your research paper conclusion with a thought-provoking or memorable statement. This can leave a lasting impression on your readers and wrap up your paper effectively. Avoid introducing new information or arguments here.

- Proofread and Revise : Carefully proofread your conclusion for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Ensure that your ideas flow smoothly and that your conclusion is coherent and well-structured.

Write your research paper conclusion 2x faster with Paperpal. Try it now!

Remember that a well-crafted research paper conclusion is a reflection of the strength of your research and your ability to communicate its significance effectively. It should leave a lasting impression on your readers and tie together all the threads of your paper. Now you know how to start the conclusion of a research paper and what elements to include to make it impactful, let’s look at a research paper conclusion sample.

How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

A research paper conclusion is not just a summary of your study, but a synthesis of the key findings that ties the research together and places it in a broader context. A research paper conclusion should be concise, typically around one paragraph in length. However, some complex topics may require a longer conclusion to ensure the reader is left with a clear understanding of the study’s significance. Paperpal, an AI writing assistant trusted by over 800,000 academics globally, can help you write a well-structured conclusion for your research paper.

- Sign Up or Log In: Create a new Paperpal account or login with your details.

- Navigate to Features : Once logged in, head over to the features’ side navigation pane. Click on Templates and you’ll find a suite of generative AI features to help you write better, faster.

- Generate an outline: Under Templates, select ‘Outlines’. Choose ‘Research article’ as your document type.

- Select your section: Since you’re focusing on the conclusion, select this section when prompted.

- Choose your field of study: Identifying your field of study allows Paperpal to provide more targeted suggestions, ensuring the relevance of your conclusion to your specific area of research.

- Provide a brief description of your study: Enter details about your research topic and findings. This information helps Paperpal generate a tailored outline that aligns with your paper’s content.

- Generate the conclusion outline: After entering all necessary details, click on ‘generate’. Paperpal will then create a structured outline for your conclusion, to help you start writing and build upon the outline.

- Write your conclusion: Use the generated outline to build your conclusion. The outline serves as a guide, ensuring you cover all critical aspects of a strong conclusion, from summarizing key findings to highlighting the research’s implications.

- Refine and enhance: Paperpal’s ‘Make Academic’ feature can be particularly useful in the final stages. Select any paragraph of your conclusion and use this feature to elevate the academic tone, ensuring your writing is aligned to the academic journal standards.

By following these steps, Paperpal not only simplifies the process of writing a research paper conclusion but also ensures it is impactful, concise, and aligned with academic standards. Sign up with Paperpal today and write your research paper conclusion 2x faster .

The research paper conclusion is a crucial part of your paper as it provides the final opportunity to leave a strong impression on your readers. In the research paper conclusion, summarize the main points of your research paper by restating your research statement, highlighting the most important findings, addressing the research questions or objectives, explaining the broader context of the study, discussing the significance of your findings, providing recommendations if applicable, and emphasizing the takeaway message. The main purpose of the conclusion is to remind the reader of the main point or argument of your paper and to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings and their implications. All these elements should feature on your list of what to put in the conclusion of a research paper to create a strong final statement for your work.

A strong conclusion is a critical component of a research paper, as it provides an opportunity to wrap up your arguments, reiterate your main points, and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here are the key elements of a strong research paper conclusion: 1. Conciseness : A research paper conclusion should be concise and to the point. It should not introduce new information or ideas that were not discussed in the body of the paper. 2. Summarization : The research paper conclusion should be comprehensive enough to give the reader a clear understanding of the research’s main contributions. 3 . Relevance : Ensure that the information included in the research paper conclusion is directly relevant to the research paper’s main topic and objectives; avoid unnecessary details. 4 . Connection to the Introduction : A well-structured research paper conclusion often revisits the key points made in the introduction and shows how the research has addressed the initial questions or objectives. 5. Emphasis : Highlight the significance and implications of your research. Why is your study important? What are the broader implications or applications of your findings? 6 . Call to Action : Include a call to action or a recommendation for future research or action based on your findings.

The length of a research paper conclusion can vary depending on several factors, including the overall length of the paper, the complexity of the research, and the specific journal requirements. While there is no strict rule for the length of a conclusion, but it’s generally advisable to keep it relatively short. A typical research paper conclusion might be around 5-10% of the paper’s total length. For example, if your paper is 10 pages long, the conclusion might be roughly half a page to one page in length.

In general, you do not need to include citations in the research paper conclusion. Citations are typically reserved for the body of the paper to support your arguments and provide evidence for your claims. However, there may be some exceptions to this rule: 1. If you are drawing a direct quote or paraphrasing a specific source in your research paper conclusion, you should include a citation to give proper credit to the original author. 2. If your conclusion refers to or discusses specific research, data, or sources that are crucial to the overall argument, citations can be included to reinforce your conclusion’s validity.

The conclusion of a research paper serves several important purposes: 1. Summarize the Key Points 2. Reinforce the Main Argument 3. Provide Closure 4. Offer Insights or Implications 5. Engage the Reader. 6. Reflect on Limitations

Remember that the primary purpose of the research paper conclusion is to leave a lasting impression on the reader, reinforcing the key points and providing closure to your research. It’s often the last part of the paper that the reader will see, so it should be strong and well-crafted.

- Makar, G., Foltz, C., Lendner, M., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2018). How to write effective discussion and conclusion sections. Clinical spine surgery, 31(8), 345-346.

- Bunton, D. (2005). The structure of PhD conclusion chapters. Journal of English for academic purposes , 4 (3), 207-224.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

Preflight For Editorial Desk: The Perfect Hybrid (AI + Human) Assistance Against Compromised Manuscripts

You may also like, measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, phd qualifying exam: tips for success , ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for..., 9 steps to publish a research paper, what are the different types of research papers.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Results/Findings Section in Research

What is the research paper Results section and what does it do?

The Results section of a scientific research paper represents the core findings of a study derived from the methods applied to gather and analyze information. It presents these findings in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation from the author, setting up the reader for later interpretation and evaluation in the Discussion section. A major purpose of the Results section is to break down the data into sentences that show its significance to the research question(s).

The Results section appears third in the section sequence in most scientific papers. It follows the presentation of the Methods and Materials and is presented before the Discussion section —although the Results and Discussion are presented together in many journals. This section answers the basic question “What did you find in your research?”

What is included in the Results section?

The Results section should include the findings of your study and ONLY the findings of your study. The findings include:

- Data presented in tables, charts, graphs, and other figures (may be placed into the text or on separate pages at the end of the manuscript)

- A contextual analysis of this data explaining its meaning in sentence form

- All data that corresponds to the central research question(s)

- All secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

If the scope of the study is broad, or if you studied a variety of variables, or if the methodology used yields a wide range of different results, the author should present only those results that are most relevant to the research question stated in the Introduction section .

As a general rule, any information that does not present the direct findings or outcome of the study should be left out of this section. Unless the journal requests that authors combine the Results and Discussion sections, explanations and interpretations should be omitted from the Results.

How are the results organized?

The best way to organize your Results section is “logically.” One logical and clear method of organizing research results is to provide them alongside the research questions—within each research question, present the type of data that addresses that research question.

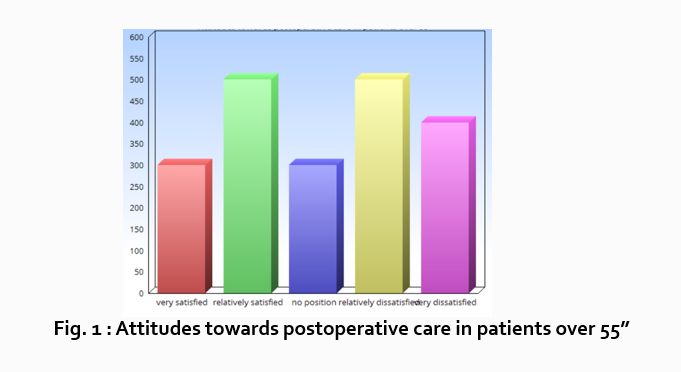

Let’s look at an example. Your research question is based on a survey among patients who were treated at a hospital and received postoperative care. Let’s say your first research question is:

“What do hospital patients over age 55 think about postoperative care?”

This can actually be represented as a heading within your Results section, though it might be presented as a statement rather than a question:

Attitudes towards postoperative care in patients over the age of 55

Now present the results that address this specific research question first. In this case, perhaps a table illustrating data from a survey. Likert items can be included in this example. Tables can also present standard deviations, probabilities, correlation matrices, etc.

Following this, present a content analysis, in words, of one end of the spectrum of the survey or data table. In our example case, start with the POSITIVE survey responses regarding postoperative care, using descriptive phrases. For example:

“Sixty-five percent of patients over 55 responded positively to the question “ Are you satisfied with your hospital’s postoperative care ?” (Fig. 2)

Include other results such as subcategory analyses. The amount of textual description used will depend on how much interpretation of tables and figures is necessary and how many examples the reader needs in order to understand the significance of your research findings.

Next, present a content analysis of another part of the spectrum of the same research question, perhaps the NEGATIVE or NEUTRAL responses to the survey. For instance:

“As Figure 1 shows, 15 out of 60 patients in Group A responded negatively to Question 2.”

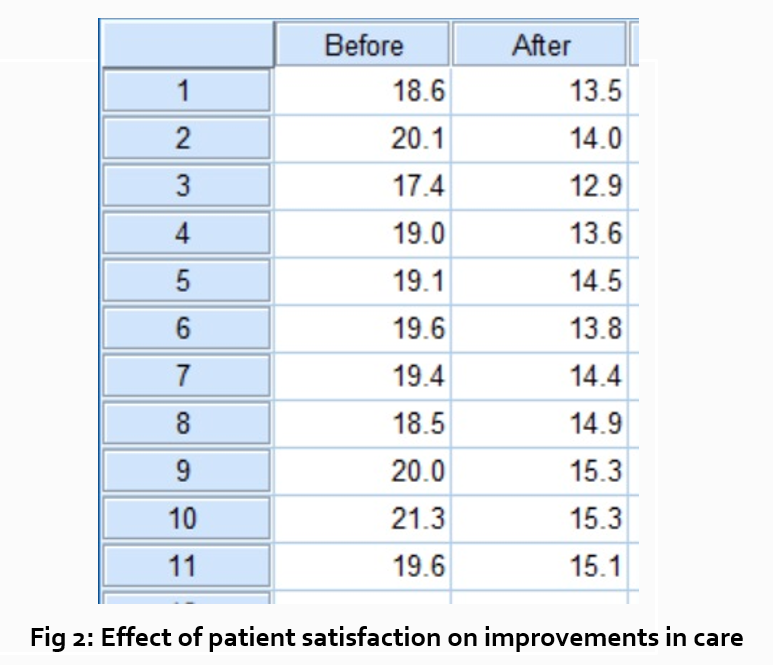

After you have assessed the data in one figure and explained it sufficiently, move on to your next research question. For example:

“How does patient satisfaction correspond to in-hospital improvements made to postoperative care?”

This kind of data may be presented through a figure or set of figures (for instance, a paired T-test table).

Explain the data you present, here in a table, with a concise content analysis:

“The p-value for the comparison between the before and after groups of patients was .03% (Fig. 2), indicating that the greater the dissatisfaction among patients, the more frequent the improvements that were made to postoperative care.”

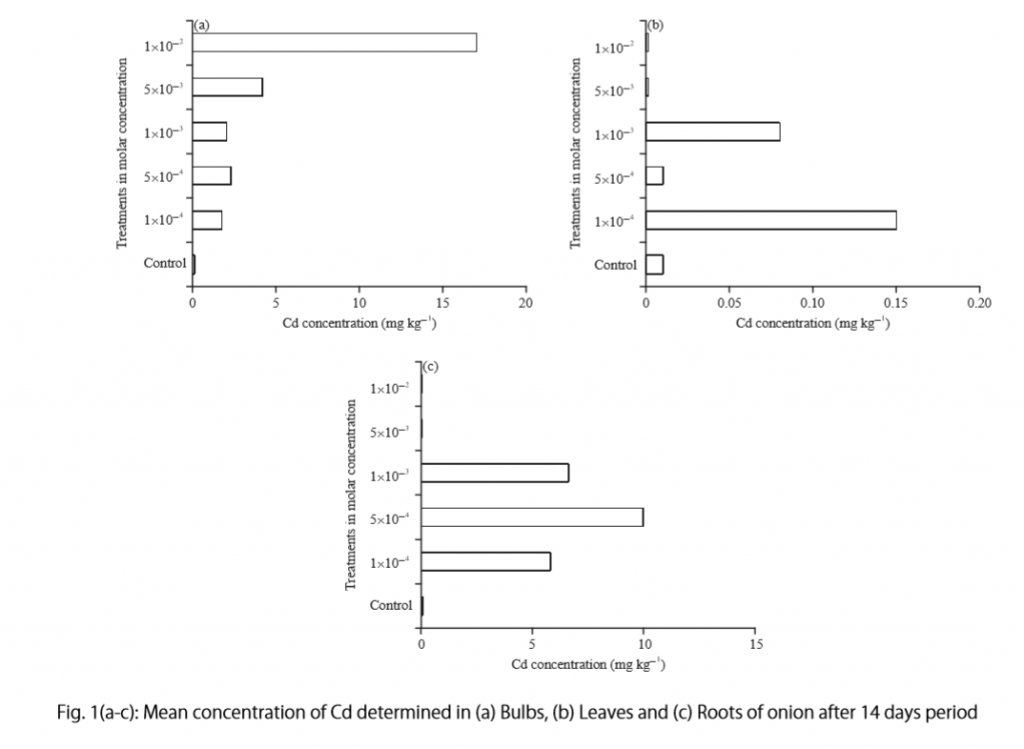

Let’s examine another example of a Results section from a study on plant tolerance to heavy metal stress . In the Introduction section, the aims of the study are presented as “determining the physiological and morphological responses of Allium cepa L. towards increased cadmium toxicity” and “evaluating its potential to accumulate the metal and its associated environmental consequences.” The Results section presents data showing how these aims are achieved in tables alongside a content analysis, beginning with an overview of the findings:

“Cadmium caused inhibition of root and leave elongation, with increasing effects at higher exposure doses (Fig. 1a-c).”

The figure containing this data is cited in parentheses. Note that this author has combined three graphs into one single figure. Separating the data into separate graphs focusing on specific aspects makes it easier for the reader to assess the findings, and consolidating this information into one figure saves space and makes it easy to locate the most relevant results.

Following this overall summary, the relevant data in the tables is broken down into greater detail in text form in the Results section.

- “Results on the bio-accumulation of cadmium were found to be the highest (17.5 mg kgG1) in the bulb, when the concentration of cadmium in the solution was 1×10G2 M and lowest (0.11 mg kgG1) in the leaves when the concentration was 1×10G3 M.”

Captioning and Referencing Tables and Figures

Tables and figures are central components of your Results section and you need to carefully think about the most effective way to use graphs and tables to present your findings . Therefore, it is crucial to know how to write strong figure captions and to refer to them within the text of the Results section.

The most important advice one can give here as well as throughout the paper is to check the requirements and standards of the journal to which you are submitting your work. Every journal has its own design and layout standards, which you can find in the author instructions on the target journal’s website. Perusing a journal’s published articles will also give you an idea of the proper number, size, and complexity of your figures.

Regardless of which format you use, the figures should be placed in the order they are referenced in the Results section and be as clear and easy to understand as possible. If there are multiple variables being considered (within one or more research questions), it can be a good idea to split these up into separate figures. Subsequently, these can be referenced and analyzed under separate headings and paragraphs in the text.

To create a caption, consider the research question being asked and change it into a phrase. For instance, if one question is “Which color did participants choose?”, the caption might be “Color choice by participant group.” Or in our last research paper example, where the question was “What is the concentration of cadmium in different parts of the onion after 14 days?” the caption reads:

“Fig. 1(a-c): Mean concentration of Cd determined in (a) bulbs, (b) leaves, and (c) roots of onions after a 14-day period.”

Steps for Composing the Results Section

Because each study is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to designing a strategy for structuring and writing the section of a research paper where findings are presented. The content and layout of this section will be determined by the specific area of research, the design of the study and its particular methodologies, and the guidelines of the target journal and its editors. However, the following steps can be used to compose the results of most scientific research studies and are essential for researchers who are new to preparing a manuscript for publication or who need a reminder of how to construct the Results section.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the target journal or publisher provides authors and read research papers it has published, especially those with similar topics, methods, or results to your study.

- The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches.

- Note length limitations on restrictions on content. For instance, while many journals require the Results and Discussion sections to be separate, others do not—qualitative research papers often include results and interpretations in the same section (“Results and Discussion”).

- Reading the aims and scope in the journal’s “ guide for authors ” section and understanding the interests of its readers will be invaluable in preparing to write the Results section.

Step 2 : Consider your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements and catalogue your results.

- Focus on experimental results and other findings that are especially relevant to your research questions and objectives and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses.

- Catalogue your findings—use subheadings to streamline and clarify your report. This will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Create appendices that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers.

- Decide how you will structure of your results. You might match the order of the research questions and hypotheses to your results, or you could arrange them according to the order presented in the Methods section. A chronological order or even a hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. Consider your audience, evidence, and most importantly, the objectives of your research when choosing a structure for presenting your findings.

Step 3 : Design figures and tables to present and illustrate your data.

- Tables and figures should be numbered according to the order in which they are mentioned in the main text of the paper.

- Information in figures should be relatively self-explanatory (with the aid of captions), and their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for readers to understand the findings without reading all of the text.

- Use tables and figures as a focal point to tell a clear and informative story about your research and avoid repeating information. But remember that while figures clarify and enhance the text, they cannot replace it.

Step 4 : Draft your Results section using the findings and figures you have organized.

- The goal is to communicate this complex information as clearly and precisely as possible; precise and compact phrases and sentences are most effective.

- In the opening paragraph of this section, restate your research questions or aims to focus the reader’s attention to what the results are trying to show. It is also a good idea to summarize key findings at the end of this section to create a logical transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows.

- Try to write in the past tense and the active voice to relay the findings since the research has already been done and the agent is usually clear. This will ensure that your explanations are also clear and logical.

- Make sure that any specialized terminology or abbreviation you have used here has been defined and clarified in the Introduction section .

Step 5 : Review your draft; edit and revise until it reports results exactly as you would like to have them reported to your readers.

- Double-check the accuracy and consistency of all the data, as well as all of the visual elements included.

- Read your draft aloud to catch language errors (grammar, spelling, and mechanics), awkward phrases, and missing transitions.

- Ensure that your results are presented in the best order to focus on objectives and prepare readers for interpretations, valuations, and recommendations in the Discussion section . Look back over the paper’s Introduction and background while anticipating the Discussion and Conclusion sections to ensure that the presentation of your results is consistent and effective.

- Consider seeking additional guidance on your paper. Find additional readers to look over your Results section and see if it can be improved in any way. Peers, professors, or qualified experts can provide valuable insights.

One excellent option is to use a professional English proofreading and editing service such as Wordvice, including our paper editing service . With hundreds of qualified editors from dozens of scientific fields, Wordvice has helped thousands of authors revise their manuscripts and get accepted into their target journals. Read more about the proofreading and editing process before proceeding with getting academic editing services and manuscript editing services for your manuscript.

As the representation of your study’s data output, the Results section presents the core information in your research paper. By writing with clarity and conciseness and by highlighting and explaining the crucial findings of their study, authors increase the impact and effectiveness of their research manuscripts.

For more articles and videos on writing your research manuscript, visit Wordvice’s Resources page.

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For qualitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD Cand). Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

So, you’ve collected and analysed your qualitative data, and it’s time to write up your results chapter – exciting! But where do you start? In this post, we’ll guide you through the qualitative results chapter (also called the findings chapter), step by step.

Overview: Qualitative Results Chapter

- What (exactly) the qualitative results chapter is

- What to include in your results chapter

- How to write up your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

What exactly is the results chapter?

The results chapter in a dissertation or thesis (or any formal academic research piece) is where you objectively and neutrally present the findings of your qualitative analysis (or analyses if you used multiple qualitative analysis methods ). This chapter can sometimes be combined with the discussion chapter (where you interpret the data and discuss its meaning), depending on your university’s preference. We’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as that’s the most common approach.

In contrast to a quantitative results chapter that presents numbers and statistics, a qualitative results chapter presents data primarily in the form of words . But this doesn’t mean that a qualitative study can’t have quantitative elements – you could, for example, present the number of times a theme or topic pops up in your data, depending on the analysis method(s) you adopt.

Adding a quantitative element to your study can add some rigour, which strengthens your results by providing more evidence for your claims. This is particularly common when using qualitative content analysis. Keep in mind though that qualitative research aims to achieve depth, richness and identify nuances , so don’t get tunnel vision by focusing on the numbers. They’re just cream on top in a qualitative analysis.

So, to recap, the results chapter is where you objectively present the findings of your analysis, without interpreting them (you’ll save that for the discussion chapter). With that out the way, let’s take a look at what you should include in your results chapter.

What should you include in the results chapter?

As we’ve mentioned, your qualitative results chapter should purely present and describe your results , not interpret them in relation to the existing literature or your research questions . Any speculations or discussion about the implications of your findings should be reserved for your discussion chapter.

In your results chapter, you’ll want to talk about your analysis findings and whether or not they support your hypotheses (if you have any). Naturally, the exact contents of your results chapter will depend on which qualitative analysis method (or methods) you use. For example, if you were to use thematic analysis, you’d detail the themes identified in your analysis, using extracts from the transcripts or text to support your claims.

While you do need to present your analysis findings in some detail, you should avoid dumping large amounts of raw data in this chapter. Instead, focus on presenting the key findings and using a handful of select quotes or text extracts to support each finding . The reams of data and analysis can be relegated to your appendices.

While it’s tempting to include every last detail you found in your qualitative analysis, it is important to make sure that you report only that which is relevant to your research aims, objectives and research questions . Always keep these three components, as well as your hypotheses (if you have any) front of mind when writing the chapter and use them as a filter to decide what’s relevant and what’s not.

Need a helping hand?

How do I write the results chapter?

Now that we’ve covered the basics, it’s time to look at how to structure your chapter. Broadly speaking, the results chapter needs to contain three core components – the introduction, the body and the concluding summary. Let’s take a look at each of these.

Section 1: Introduction

The first step is to craft a brief introduction to the chapter. This intro is vital as it provides some context for your findings. In your introduction, you should begin by reiterating your problem statement and research questions and highlight the purpose of your research . Make sure that you spell this out for the reader so that the rest of your chapter is well contextualised.

The next step is to briefly outline the structure of your results chapter. In other words, explain what’s included in the chapter and what the reader can expect. In the results chapter, you want to tell a story that is coherent, flows logically, and is easy to follow , so make sure that you plan your structure out well and convey that structure (at a high level), so that your reader is well oriented.

The introduction section shouldn’t be lengthy. Two or three short paragraphs should be more than adequate. It is merely an introduction and overview, not a summary of the chapter.

Pro Tip – To help you structure your chapter, it can be useful to set up an initial draft with (sub)section headings so that you’re able to easily (re)arrange parts of your chapter. This will also help your reader to follow your results and give your chapter some coherence. Be sure to use level-based heading styles (e.g. Heading 1, 2, 3 styles) to help the reader differentiate between levels visually. You can find these options in Word (example below).

Section 2: Body

Before we get started on what to include in the body of your chapter, it’s vital to remember that a results section should be completely objective and descriptive, not interpretive . So, be careful not to use words such as, “suggests” or “implies”, as these usually accompany some form of interpretation – that’s reserved for your discussion chapter.

The structure of your body section is very important , so make sure that you plan it out well. When planning out your qualitative results chapter, create sections and subsections so that you can maintain the flow of the story you’re trying to tell. Be sure to systematically and consistently describe each portion of results. Try to adopt a standardised structure for each portion so that you achieve a high level of consistency throughout the chapter.

For qualitative studies, results chapters tend to be structured according to themes , which makes it easier for readers to follow. However, keep in mind that not all results chapters have to be structured in this manner. For example, if you’re conducting a longitudinal study, you may want to structure your chapter chronologically. Similarly, you might structure this chapter based on your theoretical framework . The exact structure of your chapter will depend on the nature of your study , especially your research questions.

As you work through the body of your chapter, make sure that you use quotes to substantiate every one of your claims . You can present these quotes in italics to differentiate them from your own words. A general rule of thumb is to use at least two pieces of evidence per claim, and these should be linked directly to your data. Also, remember that you need to include all relevant results , not just the ones that support your assumptions or initial leanings.

In addition to including quotes, you can also link your claims to the data by using appendices , which you should reference throughout your text. When you reference, make sure that you include both the name/number of the appendix , as well as the line(s) from which you drew your data.

As referencing styles can vary greatly, be sure to look up the appendix referencing conventions of your university’s prescribed style (e.g. APA , Harvard, etc) and keep this consistent throughout your chapter.

Section 3: Concluding summary

The concluding summary is very important because it summarises your key findings and lays the foundation for the discussion chapter . Keep in mind that some readers may skip directly to this section (from the introduction section), so make sure that it can be read and understood well in isolation.

In this section, you need to remind the reader of the key findings. That is, the results that directly relate to your research questions and that you will build upon in your discussion chapter. Remember, your reader has digested a lot of information in this chapter, so you need to use this section to remind them of the most important takeaways.

Importantly, the concluding summary should not present any new information and should only describe what you’ve already presented in your chapter. Keep it concise – you’re not summarising the whole chapter, just the essentials.

Tips and tricks for an A-grade results chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear picture of what the qualitative results chapter is all about, here are some quick tips and reminders to help you craft a high-quality chapter:

- Your results chapter should be written in the past tense . You’ve done the work already, so you want to tell the reader what you found , not what you are currently finding .

- Make sure that you review your work multiple times and check that every claim is adequately backed up by evidence . Aim for at least two examples per claim, and make use of an appendix to reference these.

- When writing up your results, make sure that you stick to only what is relevant . Don’t waste time on data that are not relevant to your research objectives and research questions.

- Use headings and subheadings to create an intuitive, easy to follow piece of writing. Make use of Microsoft Word’s “heading styles” and be sure to use them consistently.

- When referring to numerical data, tables and figures can provide a useful visual aid. When using these, make sure that they can be read and understood independent of your body text (i.e. that they can stand-alone). To this end, use clear, concise labels for each of your tables or figures and make use of colours to code indicate differences or hierarchy.

- Similarly, when you’re writing up your chapter, it can be useful to highlight topics and themes in different colours . This can help you to differentiate between your data if you get a bit overwhelmed and will also help you to ensure that your results flow logically and coherently.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your results chapter (or any chapter of your dissertation or thesis), check out our private dissertation coaching service here or book a free initial consultation to discuss how we can help you.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

20 Comments

This was extremely helpful. Thanks a lot guys

Hi, thanks for the great research support platform created by the gradcoach team!

I wanted to ask- While “suggests” or “implies” are interpretive terms, what terms could we use for the results chapter? Could you share some examples of descriptive terms?

I think that instead of saying, ‘The data suggested, or The data implied,’ you can say, ‘The Data showed or revealed, or illustrated or outlined’…If interview data, you may say Jane Doe illuminated or elaborated, or Jane Doe described… or Jane Doe expressed or stated.

I found this article very useful. Thank you very much for the outstanding work you are doing.

What if i have 3 different interviewees answering the same interview questions? Should i then present the results in form of the table with the division on the 3 perspectives or rather give a results in form of the text and highlight who said what?

I think this tabular representation of results is a great idea. I am doing it too along with the text. Thanks

That was helpful was struggling to separate the discussion from the findings

this was very useful, Thank you.

Very helpful, I am confident to write my results chapter now.

It is so helpful! It is a good job. Thank you very much!

Very useful, well explained. Many thanks.

Hello, I appreciate the way you provided a supportive comments about qualitative results presenting tips

I loved this! It explains everything needed, and it has helped me better organize my thoughts. What words should I not use while writing my results section, other than subjective ones.

Thanks a lot, it is really helpful

Thank you so much dear, i really appropriate your nice explanations about this.

Thank you so much for this! I was wondering if anyone could help with how to prproperly integrate quotations (Excerpts) from interviews in the finding chapter in a qualitative research. Please GradCoach, address this issue and provide examples.

what if I’m not doing any interviews myself and all the information is coming from case studies that have already done the research.

Very helpful thank you.

This was very helpful as I was wondering how to structure this part of my dissertation, to include the quotes… Thanks for this explanation

This is very helpful, thanks! I am required to write up my results chapters with the discussion in each of them – any tips and tricks for this strategy?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Discoveries

- Right Journal

- Journal Metrics

- Journal Fit

- Abbreviation

- In-Text Citations

- Bibliographies

- Writing an Article

- Peer Review Types

- Acknowledgements

- Withdrawing a Paper

- Form Letter

- ISO, ANSI, CFR

- Google Scholar

- Journal Manuscript Editing

- Research Manuscript Editing

Book Editing

- Manuscript Editing Services

Medical Editing

- Bioscience Editing

- Physical Science Editing

- PhD Thesis Editing Services

- PhD Editing

- Master’s Proofreading

- Bachelor’s Editing

- Dissertation Proofreading Services

- Best Dissertation Proofreaders

- Masters Dissertation Proofreading

- PhD Proofreaders

- Proofreading PhD Thesis Price

- Journal Article Editing

- Book Editing Service

- Editing and Proofreading Services

- Research Paper Editing

- Medical Manuscript Editing

- Academic Editing

- Social Sciences Editing

- Academic Proofreading

- PhD Theses Editing

- Dissertation Proofreading

- Proofreading Rates UK

- Medical Proofreading

- PhD Proofreading Services UK

- Academic Proofreading Services UK

Medical Editing Services

- Life Science Editing

- Biomedical Editing

- Environmental Science Editing

- Pharmaceutical Science Editing

- Economics Editing

- Psychology Editing

- Sociology Editing

- Archaeology Editing

- History Paper Editing

- Anthropology Editing

- Law Paper Editing

- Engineering Paper Editing

- Technical Paper Editing

- Philosophy Editing

- PhD Dissertation Proofreading

- Lektorat Englisch

- Akademisches Lektorat

- Lektorat Englisch Preise

- Wissenschaftliches Lektorat

- Lektorat Doktorarbeit

PhD Thesis Editing

- Thesis Proofreading Services

- PhD Thesis Proofreading

- Proofreading Thesis Cost

- Proofreading Thesis

- Thesis Editing Services

- Professional Thesis Editing

- Thesis Editing Cost

- Proofreading Dissertation

- Dissertation Proofreading Cost

- Dissertation Proofreader

- Correção de Artigos Científicos

- Correção de Trabalhos Academicos

- Serviços de Correção de Inglês

- Correção de Dissertação

- Correção de Textos Precos

- 定額 ネイティブチェック

- Copy Editing

- FREE Courses

- Revision en Ingles

- Revision de Textos en Ingles

- Revision de Tesis

- Revision Medica en Ingles

- Revision de Tesis Precio

- Revisão de Artigos Científicos

- Revisão de Trabalhos Academicos

- Serviços de Revisão de Inglês

- Revisão de Dissertação

- Revisão de Textos Precos

- Corrección de Textos en Ingles

- Corrección de Tesis

- Corrección de Tesis Precio

- Corrección Medica en Ingles

- Corrector ingles

Select Page

How To Write the Findings Section of a Research Paper

Posted by Rene Tetzner | Sep 2, 2021 | Paper Writing Advice | 0 |

How To Write the Findings Section of a Research Paper Each research project is unique, so it is natural for one researcher to make use of somewhat different strategies than another when it comes to designing and writing the section of a research paper dedicated to findings. The academic or scientific discipline of the research, the field of specialisation, the particular author or authors, the targeted journal or other publisher and the editor making the decisions about publication can all have a significant impact. The practical steps outlined below can be effectively applied to writing about the findings of most advanced research, however, and will prove especially helpful for early-career scholars who are preparing a research paper for a first publication.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the targeted journal (or other publisher) provides for authors and read research papers it has already published, particularly ones similar in topic, methods or results to your own. The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches. Watch particularly for length limitations and restrictions on content. Interpretation, for instance, is usually reserved for a later discussion section, though not always – qualitative research papers often combine findings and interpretation. Background information and descriptions of methods, on the other hand, almost always appear in earlier sections of a research paper. In most cases it is appropriate in a findings section to offer basic comparisons between the results of your study and those of other studies, but knowing exactly what the journal wants in the report of research findings is essential. Learning as much as you can about the journal’s aims and scope as well as the interests of its readers is invaluable as well.

Step 2 : Reflect at some length on your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements while planning the findings section of your paper. Choose for particular focus experimental results and other research discoveries that are particularly relevant to your research questions and objectives, and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses. Streamline and clarify your report, especially if it is long and complex, by using subheadings that will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Consider appendices for raw data that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers. The opening paragraph of a findings section often restates research questions or aims to refocus the reader’s attention, and it is always wise to summarise key findings at the end of the section, providing a smooth intellectual transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows in most research papers. There are many effective ways in which to organise research findings. The structure of your findings section might be determined by your research questions and hypotheses or match the arrangement of your methods section. A chronological order or hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. It may be best to present all the relevant findings and then explain them and your analysis of them, or explaining the results of each trial or test immediately after reporting it may render the material clearer and more comprehensible for your readers. Keep your audience, your most important evidence and your research goals in mind.

Step 3 : Design effective visual presentations of your research results to enhance the textual report of your findings. Tables of various styles and figures of all kinds such as graphs, maps and photos are used in reporting research findings, but do check the journal guidelines for instructions on the number of visual aids allowed, any required design elements and the preferred formats for numbering, labelling and placement in the manuscript. As a general rule, tables and figures should be numbered according to first mention in the main text of the paper, and each one should be clearly introduced and explained at least briefly in that text so that readers know what is presented and what they are expected to see in a particular visual element. Tables and figures should also be self-explanatory, however, so their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for a reader to understand the findings you intend to show without returning to your text. If you construct your tables and figures before drafting your findings section, they can serve as focal points to help you tell a clear and informative story about your findings and avoid unnecessary repetition. Some authors will even work on tables and figures before organising the findings section (Step 2), which can be an extremely effective approach, but it is important to remember that the textual report of findings remains primary. Visual aids can clarify and enrich the text, but they cannot take its place.

Step 4 : Write your findings section in a factual and objective manner. The goal is to communicate information – in some cases a great deal of complex information – as clearly, accurately and precisely as possible, so well-constructed sentences that maintain a simple structure will be far more effective than convoluted phrasing and expressions. The active voice is often recommended by publishers and the authors of writing manuals, and the past tense is appropriate because the research has already been done. Make sure your grammar, spelling and punctuation are correct and effective so that you are conveying the meaning you intend. Statements that are vague, imprecise or ambiguous will often confuse and mislead readers, and a verbose style will add little more than padding while wasting valuable words that might be put to far better use in clear and logical explanations. Some specialised terminology may be required when reporting findings, but anything potentially unclear or confusing that has not already been defined earlier in the paper should be clarified for readers, and the same principle applies to unusual or nonstandard abbreviations. Your readers will want to understand what you are reporting about your results, not waste time looking up terms simply to understand what you are saying. A logical approach to organising your findings section (Step 2) will help you tell a logical story about your research results as you explain, highlight, offer analysis and summarise the information necessary for readers to understand the discussion section that follows.

Step 5 : Review the draft of your findings section and edit and revise until it reports your key findings exactly as you would have them presented to your readers. Check for accuracy and consistency in data across the section as a whole and all its visual elements. Read your prose aloud to catch language errors, awkward phrases and abrupt transitions. Ensure that the order in which you have presented results is the best order for focussing readers on your research objectives and preparing them for the interpretations, speculations, recommendations and other elements of the discussion that you are planning. This will involve looking back over the paper’s introductory and background material as well as anticipating the discussion and conclusion sections, and this is precisely the right point in the process for reviewing and reflecting. Your research results have taken considerable time to obtain and analyse, so a little more time to stand back and take in the wider view from the research door you have opened is a wise investment. The opinions of any additional readers you can recruit, whether they are professional mentors and colleagues or family and friends, will often prove invaluable as well.

You might be interested in Services offered by Proof-Reading-Service.com

Journal editing.

Journal article editing services

PhD thesis editing services

Scientific Editing

Manuscript editing.

Manuscript editing services

Expert Editing

Expert editing for all papers

Research Editing

Research paper editing services

Professional book editing services

How To Write the Findings Section of a Research Paper These five steps will help you write a clear & interesting findings section for a research paper

Related Posts

How To Write a Journal Article

September 6, 2021

Tips on How To Write a Journal Article

August 30, 2021

How To Write Highlights for an Academic or Scientific Paper

September 7, 2021

Tips on How To Write an Effective Figure Legend

August 27, 2021

Our Recent Posts

Our review ratings

- Examples of Research Paper Topics in Different Study Areas Score: 98%

- Dealing with Language Problems – Journal Editor’s Feedback Score: 95%

- Making Good Use of a Professional Proofreader Score: 92%

- How To Format Your Journal Paper Using Published Articles Score: 95%

- Journal Rejection as Inspiration for a New Perspective Score: 95%

Explore our Categories

- Abbreviation in Academic Writing (4)

- Career Advice for Academics (5)

- Dealing with Paper Rejection (11)

- Grammar in Academic Writing (5)

- Help with Peer Review (7)

- How To Get Published (146)

- Paper Writing Advice (17)

- Referencing & Bibliographies (16)

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write an “Implications of Research” Section

4-minute read

- 24th October 2022

When writing research papers , theses, journal articles, or dissertations, one cannot ignore the importance of research. You’re not only the writer of your paper but also the researcher ! Moreover, it’s not just about researching your topic, filling your paper with abundant citations, and topping it off with a reference list. You need to dig deep into your research and provide related literature on your topic. You must also discuss the implications of your research.

Interested in learning more about implications of research? Read on! This post will define these implications, why they’re essential, and most importantly, how to write them. If you’re a visual learner, you might enjoy this video .

What Are Implications of Research?

Implications are potential questions from your research that justify further exploration. They state how your research findings could affect policies, theories, and/or practices.

Implications can either be practical or theoretical. The former is the direct impact of your findings on related practices, whereas the latter is the impact on the theories you have chosen in your study.

Example of a practical implication: If you’re researching a teaching method, the implication would be how teachers can use that method based on your findings.

Example of a theoretical implication: You added a new variable to Theory A so that it could cover a broader perspective.

Finally, implications aren’t the same as recommendations, and it’s important to know the difference between them .

Questions you should consider when developing the implications section:

● What is the significance of your findings?

● How do the findings of your study fit with or contradict existing research on this topic?

● Do your results support or challenge existing theories? If they support them, what new information do they contribute? If they challenge them, why do you think that is?

Why Are Implications Important?

You need implications for the following reasons:

● To reflect on what you set out to accomplish in the first place

● To see if there’s a change to the initial perspective, now that you’ve collected the data

● To inform your audience, who might be curious about the impact of your research

How to Write an Implications Section

Usually, you write your research implications in the discussion section of your paper. This is the section before the conclusion when you discuss all the hard work you did. Additionally, you’ll write the implications section before making recommendations for future research.

Implications should begin with what you discovered in your study, which differs from what previous studies found, and then you can discuss the implications of your findings.

Your implications need to be specific, meaning you should show the exact contributions of your research and why they’re essential. They should also begin with a specific sentence structure.

Examples of starting implication sentences:

● These results build on existing evidence of…

● These findings suggest that…

● These results should be considered when…

● While previous research has focused on x , these results show that y …

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

You should write your implications after you’ve stated the results of your research. In other words, summarize your findings and put them into context.

The result : One study found that young learners enjoy short activities when learning a foreign language.

The implications : This result suggests that foreign language teachers use short activities when teaching young learners, as they positively affect learning.

Example 2

The result : One study found that people who listen to calming music just before going to bed sleep better than those who watch TV.

The implications : These findings suggest that listening to calming music aids sleep quality, whereas watching TV does not.

To summarize, remember these key pointers:

● Implications are the impact of your findings on the field of study.

● They serve as a reflection of the research you’ve conducted.

● They show the specific contributions of your findings and why the audience should care.

● They can be practical or theoretical.

● They aren’t the same as recommendations.

● You write them in the discussion section of the paper.

● State the results first, and then state their implications.

Are you currently working on a thesis or dissertation? Once you’ve finished your paper (implications included), our proofreading team can help ensure that your spelling, punctuation, and grammar are perfect. Consider submitting a 500-word document for free.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Methodology: 2023 focus groups of Asian Americans

Methodology: 2022-23 survey of asian americans, table of contents.

- About the focus groups

- Participant recruitment procedures

- Moderator and interpreter qualification

- Data analysis

- Sample design

- Data collection

- Weighting and variance estimation

- Analysis of Asians living in poverty

- Acknowledgments

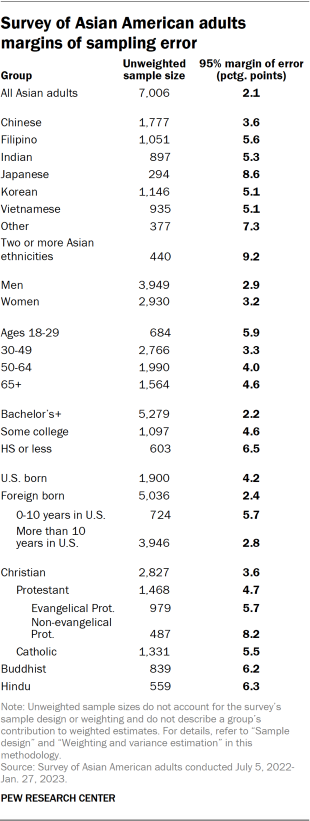

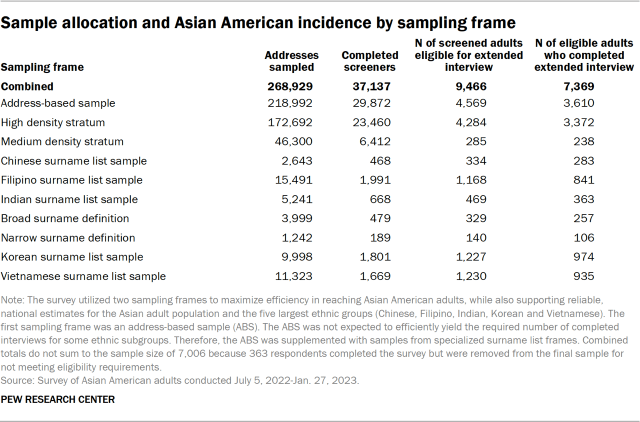

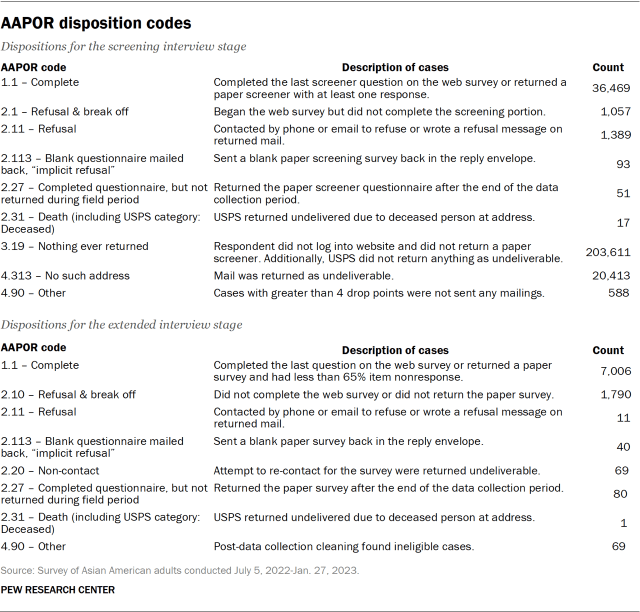

The survey analysis is drawn from a national cross-sectional survey conducted for Pew Research Center by Westat. The sampling design of the survey was an address-based sampling (ABS) approach, supplemented by list samples, to reach a nationally representative group of respondents. The survey was fielded July 5, 2022, through Jan. 27, 2023. Self-administered screening interviews were conducted with a total of 36,469 U.S. adults either online or by mail, resulting in 7,006 interviews with Asian American adults. It is these 7,006 Asian Americans who are the focus of this report. After accounting for the complex sample design and loss of precision due to weighting, the margin of sampling error for these respondents is plus or minus 2.1 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence.

The survey was administered in two stages. In the first stage, a short screening survey was administered to a national sample of U.S. adults to collect basic demographics and determine a respondent’s eligibility for the extended survey of Asian Americans. Screener respondents were considered eligible for the extended survey if they self-identified as Asian (alone or in combination with any other race or ethnicity). Note that all individuals who self-identified as Asian were asked to complete the extended survey.

To maintain consistency with the Census Bureau’s definition of “Asian,” individuals responding as Asian but who self-identified with origins that did not meet the bureau’s official standards prior to the 2020 decennial census were considered ineligible and were not asked to complete the extended survey or were removed from the final sample. Those excluded were people solely of Southwest Asian descent (e.g., Lebanese, Saudi), those with Central Asian origins (e.g., Afghan, Uzbek) as well as various other non-Asian origins. The impact of excluding these groups is small, as together they represent about 1%-2% of the national U.S. Asian population, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of the 2021 American Community Survey.

Eligible survey respondents were asked in the extended survey how they identified ethnically (for example: Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Korean, Vietnamese, or some other ethnicity with a write-in option). Note that survey respondents were asked about their ethnicity rather than nationality. For example, those classified as Chinese in the survey are those self-identifying as of Chinese ethnicity, rather than necessarily being a citizen or former citizen of the People’s Republic of China. Since this is an ethnicity, classification of survey respondents as Chinese also includes those who are Taiwanese.

The research plan for this project was submitted to Westat’s institutional review board (IRB), which is an independent committee of experts that specializes in helping to protect the rights of research participants. Due to the minimal risks associated with this questionnaire content and the population of interest, this research underwent an expedited review and received approval (approval #FWA 00005551).

Throughout this methodology statement, the terms “extended survey” and “extended questionnaire” refer to the extended survey of Asian Americans that is the focus of this report, and “eligible adults” and “eligible respondents” refer to those individuals who met its eligibility criteria, unless otherwise noted.

The survey had a complex sample design constructed to maximize efficiency in reaching Asian American adults while also supporting reliable, national estimates for the population as a whole and for the five largest ethnic groups (Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Korean and Vietnamese). Asian American adults include those who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity.

The main sample frame of the 2022-2023 Asian American Survey is an address-based sample (ABS). The ABS frame of addresses was derived from the USPS Computerized Delivery Sequence file. It is maintained by Marketing Systems Group (MSG) and is updated monthly. MSG geocodes their entire ABS frame, so block, block group, and census tract characteristics from the decennial census and the American Community Survey (ACS) could be appended to addresses and used for sampling and data collection.

All addresses on the ABS frame were geocoded to a census tract. Census tracts were then grouped into three strata based on the density of Asian American adults, defined as the proportion of Asian American adults among all adults in the tract. The three strata were defined as:

- High density: Tracts with an Asian American adult density of 10% or higher

- Medium density: Tracts with a density 3% to less than 10%

- Low density: Tracts with a density less than 3%

Mailing addresses in census tracts from the lowest density stratum, strata 3, were excluded from the sampling frame. As a result, the frame excluded 54.1% of the 2020 census tracts, 49.1% of the U.S. adult population, including 9.1% of adults who self-identified as Asian alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic ethnicity. For the largest five Asian ethnic subgroups, Filipinos had the largest percentage of excluded adults, with 6.8%, while Indians had the lowest with 4.2% of the adults. Addresses were then sampled from the two remaining strata. This stratification and the assignment of differential sampling rates to the strata were critical design components because of the rareness of the Asian American adult population.

Despite oversampling of the high- and medium-density Asian American strata in the ABS sample, the ABS sample was not expected to efficiently yield the required number of completed interviews for some ethnic subgroups. Therefore, the ABS sample was supplemented with samples from the specialized surname list frames maintained by the MSG. These list frames identify households using commercial databases linked to addresses and telephone numbers. The individuals’ surnames in these lists could be classified by likely ethnic origin. Westat requested MSG to produce five list frames: Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Korean and Vietnamese. The lists were subset to include only cases with a mailing address. Addresses sampled from the lists, unlike those sampled from the ABS frame, were not limited to high- and medium-density census tracts.

Once an address was sampled from either the ABS frame or the surname lists, an invitation was mailed to the address. The invitation requested that the adult in the household with the next birthday complete the survey.

To maximize response, the survey used a sequential mixed-mode protocol in which sampled households were first directed to respond online and later mailed a paper version of the questionnaire if they did not respond online.

The first mailing was a letter introducing the survey and providing the information necessary (URL and unique PIN) for online response. A pre-incentive of $2 was included in the mailing. This and remaining screener recruitment letters focused on the screener survey, without mentioning the possibility of eligibility for a longer survey and associated promised incentive, since most people would only be asked to complete the short screening survey. It was important for all households to complete the screening survey, not just those who identify as Asian American. As such, the invitation did not mention that the extended survey would focus on topics surrounding the Asian American experience. The invitation was generic to minimize the risk of nonresponse bias due to topic salience bias.

After one week, Westat sent a postcard reminder to all sampled individuals, followed three weeks later by a reminder letter to nonrespondents. Approximately 8.5 weeks after the initial mailing, Westat sent nonrespondents a paper version screening survey, which was a four-page booklet (one folded 11×17 paper) and a postage-paid return envelope in addition to the cover letter. If no response was obtained from those four mailings, no further contact was made.

Eligible adults who completed the screening interview on the web were immediately asked to continue with the extended questionnaire. If an eligible adult completed the screener online but did not complete the extended interview, Westat sent them a reminder letter. This was performed on a rolling basis when it had been at least one week since the web breakoff. Names were not collected until the end of the web survey, so these letters were addressed to “Recent Participant.”

If an eligible respondent completed a paper screener, Westat mailed them the extended survey and a postage-paid return envelope. This was sent weekly as completed paper screeners arrived. Westat followed these paper mailings with a reminder postcard. Later, Westat sent a final paper version via FedEx to eligible adults who had not completed the extended interview online or by paper.

A pre-incentive of $2 (in the form of two $1 bills) was sent to all sampled addresses with the first letter, which provided information about how to complete the survey online. This and subsequent screener invitations only referred to the pre-incentive without reference to the possibility of later promised incentives.

Respondents who completed the screening survey and were found eligible were offered a promised incentive of $10 to go on and complete the extended survey. All participants who completed the extended web survey were offered their choice of a $10 Amazon.com gift code instantly or $10 cash mailed. All participants who completed the survey via paper were mailed a $10 cash incentive.

In December 2022 a mailing was added for eligible respondents who had completed a screener questionnaire, either by web or paper but who had not yet completed the extended survey. It was sent to those who had received their last mailing in the standard sequence at least four weeks earlier. It included a cover letter, a paper copy of the extended survey, and a business reply envelope, and was assembled in a 9×12 envelope with a $1 bill made visible through the envelope window.

In the last month of data collection, an additional mailing was added to boost the number of Vietnamese respondents. A random sample of 4,000 addresses from the Vietnamese surname list and 2,000 addresses from the ABS frame who were flagged as likely Vietnamese were sent another copy of the first invitation letter, which contained web login credentials but no paper copy of the screener. This was sent in a No. 10 envelope with a wide window and was assembled with a $1 bill visible through the envelope window.

The mail and web screening and extended surveys were developed in English and translated into Chinese (Simplified and Traditional), Hindi, Korean, Tagalog and Vietnamese. For web, the landing page was displayed in English initially but included banners at the top and bottom of the page that allowed respondents to change the displayed language. Once in the survey, a dropdown button at the top of each page was available to respondents to toggle between languages.

The paper surveys were also formatted into all six languages. Recipients thought to be more likely to use a specific language option, based on supplemental information in the sampling frame or their address location, were sent a paper screener in that language in addition to an English screener questionnaire. Those receiving a paper extended instrument were sent the extended survey in the language in which the screener was completed. For web, respondents continued in their selected language from the screener.

Household-level weighting

The first step in weighting was creating a base weight for each sampled mailing address to account for its probability of selection into the sample. The base weight for mailing address k is called BW k and is defined as the inverse of its probability of selection. The ABS sample addresses had a probability of selection based on the stratum from which they were sampled. The supplemental samples (i.e., Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Korean and Vietnamese surname lists) also had a probability of selection from the list frames. Because all of the addresses in the list frames are also included in the ABS frame, these addresses had multiple opportunities for these addresses to be selected, and the base weights include an adjustment to account for their higher probability of selection.

Each sampled mailing address was assigned to one of four categories according to its final screener disposition. The categories were 1) household with a completed screener interview, 2) household with an incomplete screener interview, 3) ineligible (i.e., not a household, which were primarily postmaster returns), and 4) addresses for which status was unknown (i.e., addresses that were not identified as undeliverable by the USPS but from which no survey response was received).

The second step in the weighting process was adjusting the base weight to account for occupied households among those with unknown eligibility (category 4). Previous ABS studies have found that about 13% of all addresses in the ABS frame were either vacant or not home to anyone in the civilian, non-institutionalized adult population. For this survey, it was assumed that 87% of all sampled addresses from the ABS frame were eligible households. However, this value was not appropriate for the addresses sampled from the list frames, which were expected to have a higher proportion of households as these were maintained lists. For the list samples, the occupied household rate was computed as the proportion of list cases in category 3 compared to all resolved list cases (i.e., the sum of categories 1 through 3). The base weights for the share of category 4 addresses (unknown eligibility) assumed to be eligible were then allocated to cases in categories 1 and 2 (known households) so that the sum of the combined category 1 and 2 base weights equaled the number of addresses assumed to be eligible in each frame. The category 3 ineligible addresses were given a weight of zero.