- Open access

- Published: 05 August 2024

Co-creating community wellbeing initiatives: what is the evidence and how do they work?

- Nicholas Powell 1 ,

- Hazel Dalton 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Joanne Lawrence-Bourne 1 &

- David Perkins 5

International Journal of Mental Health Systems volume 18 , Article number: 28 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1463 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Addressing wellbeing at the community level, using a public health approach may build wellbeing and protective factors for all. A collaborative, community-owned approach can bring together experience, networks, local knowledge, and other resources to form a locally-driven, place-based initiative that can address complex issues effectively. Research on community empowerment, coalition functioning, health interventions and the use of local data provide evidence about what can be achieved in communities. There is less understanding about how communities can collaborate to bring about change, especially for mental health and wellbeing.

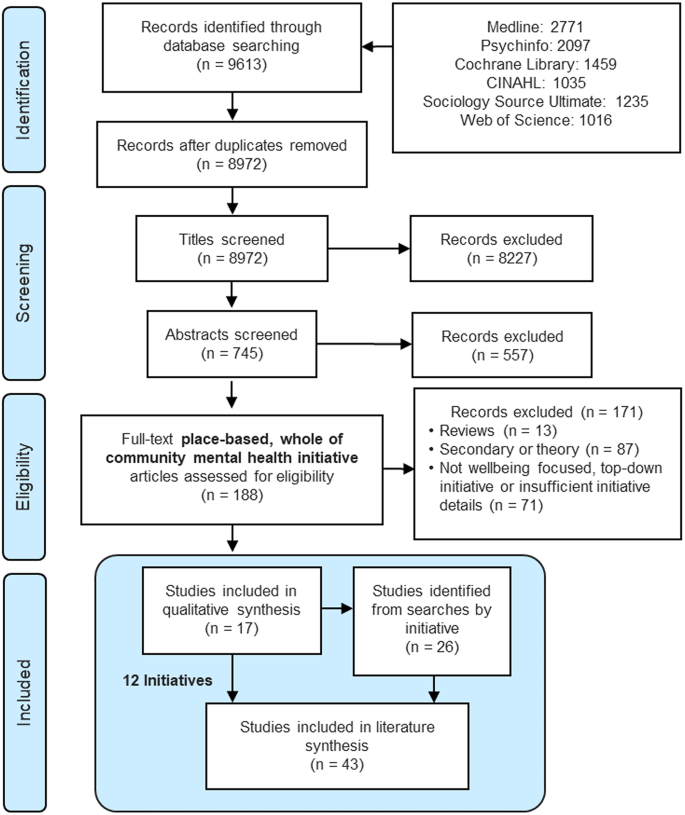

A comprehensive literature search was undertaken to identify community wellbeing initiatives that address mental health. After screening 8,972 titles, 745 abstracts and 188 full-texts, 12 exemplar initiatives were identified (39 related papers).

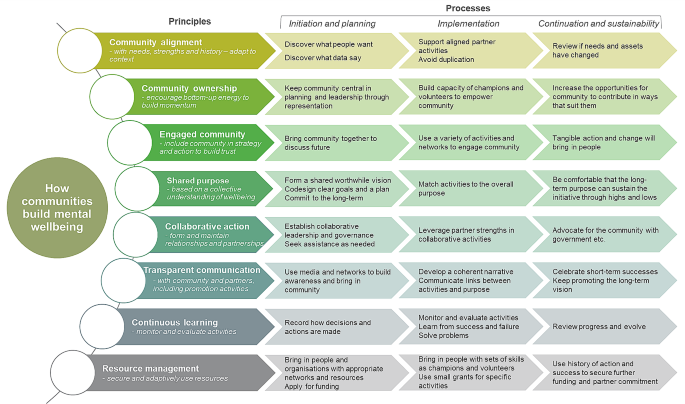

Eight key principles allowed these initiatives to become established and operate successfully. These principles related to implementation and outcome lessons that allowed these initiatives to contribute to the goal of increasing community mental health and wellbeing. A framework for community wellbeing initiatives addressing principles, development, implementation and sustainability was derived from this analysis, with processes mapped therein.

This framework provides evidence for communities seeking to address community wellbeing and avoid the pitfalls experienced by many well-meaning but short-lived initiatives.

Graphical Abstract

Despite large investments, rates of mental illness have risen for decades, particularly in western societies [ 1 ]. The reasons are varied and complex and have been the subject of intensive study [ 2 ]. Risk factors include loneliness, inequality, disempowerment, and multiple and compounding adversities, factors that have been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic [ 3 ]. There is widespread recognition of the problem and broad agreement that policy changes are needed [ 4 , 5 ]. Recovery from the pandemic and an increased focus on mental health represent an opportunity to reinvent the way society invests in mental health and wellbeing. The question becomes where and how to intervene to improve population mental health and wellbeing.

Currently, most mental health expenditure occurs in the mental illness treatment system [ 4 ]. These individualised and medicalised approaches are effective for treating mental illness in some people [ 6 , 7 ], but do little to prevent declining population mental health, promote wellbeing, or improve the conditions that contribute to mental illness [ 8 ]. It is more expensive and difficult to treat advanced illness than to intervene early or prevent the illness in the first place, thus prevention and early intervention activities are key components within a comprehensive mental health system [ 9 ]. The concept of ‘mental health’ has become stigmatized, associated with mental illness and mental health problems in the public eye [ 10 ], thereby limiting its utility in the promotion of positive mental health. Thus for the purpose of this review, we have used the concept of eudemonic wellbeing to indicate positive mental health. This is a process of living well that supports positive psychological and physical wellness, underpinned by a theory of self-determination [ 11 ].

Since the 1960s programs have been developed to empower or share power with communities to create social and health change [ 12 ]. These include the Alma Ata Declaration [ 13 , 14 ], the Ottawa Charter [ 15 ], Healthy Cities [ 16 ], community empowerment projects [ 17 , 18 , 19 ], social capital promotion [ 20 , 21 ] and action on the social determinants of health [ 22 , 23 ], and have each made impacts on human wellbeing and informed the way that public and population health interventions are conducted [ 24 ]. Short political timeframes mean interventions in particular places are often abandoned, then replaced, this loss of continuity impairs trust and limits effectiveness [ 25 ]. Working through and with communities may be the most effective way to achieve long-term, independent and sustainable change, particularly when behaviour change is needed [ 26 ]. Initiatives to create vibrant and social communities may act at an appropriate level to improve mental health and wellbeing for all [ 27 ]. Working at the community level may also help to reframe the popular understanding of wellness so that poor wellbeing is seen less as a personal failing and more as a product of a pathogenic environment [ 28 ].

While there are many models of what community initiative can do to build wellbeing, there is little information on how they can accomplish these steps, or how factors change over time. For example, a review of community coalition-driven initiatives found beneficial changes in health outcomes and behaviours, however, there was insufficient process evidence on how the effects were mediated [ 12 ]. Previous research suggests that community level work should take a grassroots, bottom-up and codesigned, and collaborative approach (variously referred to as partnerships, coalitions, teams or working groups) that acknowledges complexity, power inequalities and shared priorities [ 29 ]. Community collaborative group-based social ecological approaches have been used for decades to facilitate ownership in a context-based and culturally sensitive manner through capacity building [ 30 ]. To help engage the community, there are framing and language recommendations so that needs and objectives are understood as opportunities, not problems or vulnerabilities [ 31 , 32 ]. Top-down and overly medicalised models have been seen to fail [ 33 ]. The collective and relational nature of problems/assets such as loneliness/social capital and various social determinants of mental health reinforce the utility of a broader community focus on mental health and wellbeing.

Community wellbeing initiatives

In this review, we examine the broader concept of community wellbeing initiatives by exploring the underlying sub-concepts. Wellbeing has become a catch-all term that is often used interchangeably or in partnership with mental and physical health, happiness, life satisfaction and others.

Whilst wellbeing is a more positive concept than mental health, it is a contested concept [ 34 ], used in communities, industry, policy and practice. Wellbeing has multiple aspects including: physical, mental, intellectual, social, emotional and spiritual components. As discussed above, in this review, we use the wellbeing definition as postulated in Ryan’s theory of self-determination, which stands in the positive mental health domain [ 11 ]. This distinguishes it from other community health and wellbeing reviews that focus on physical activity and dietary interventions.

In the context of public health and health policy, ‘community’ can be difficult to define. Two key approaches highlight geographical and functional communities [ 35 ]. This study uses the definition of “community to refer to a geographically bound group of people on a local scale who are subject to either direct or indirect interaction with each other” [ 36 ]. This is a setting where local place-based resources can be found and applied. Much policy focus has been applied to geographically bound areas, e.g. the UK government national approach is still deployed at the local government area level, where local context can be addressed [ 37 ]. Moreover, place is where things happen, such as natural disasters, acute economic insults such as the closure of local enterprises, and suicide clusters [ 3 ]. Place is where the context can be understood, challenges collectively felt and local strengths recognised and mobilised. Initiatives in these settings present an opportunity to deliver wellbeing and mental health promotion activities that are not provided by local health services, who focus overwhelmingly on the treatment of acute mental illness.

Community wellbeing concerns those factors that enable or hinder a citizen’s ability to build and maintain their wellbeing in a particular place [ 38 , 39 , 40 ]. For example, social capital, goods, infrastructure and service accessibility and cultural values influence individual wellbeing and can be built at the community level [ 41 ]. Community is where people live, it is the environment that shapes their wellbeing. In short, “community” concerns the level of analysis and “well-being” describes the scope of analysis [ 36 ].

In this paper, we analyse the literature on community-built wellbeing initiatives that have mental health and wellbeing as a stated objective or key outcome. For reasons discussed above, this paper focuses on initiatives that empower the community to create the change they wish to see in their area. The identified exemplars have been subjected to detailed analysis to create a common framework for the process factors associated with community wellbeing initiatives. The purpose of the study is to assist communities to build their own interventions to address mental health and wellbeing. The research questions are as follows:

Can community wellbeing initiatives, with wellbeing as a stated objective, be identified that have some implementation success as measured by (i) duration of existence (at least two years) and (ii) have published evidence regarding the initiative (e.g. peer-reviewed article)?

For the chosen community wellbeing initiatives:

What was the context for initiation?

Which stakeholders were involved and what were their roles in the successful implementation?

What was done to promote community wellbeing by these initiatives?

How was momentum sustained and progress measured?

What were the implementation and outcome lessons that may be used by other communities?

Search strategy

An initial scoping review of the field of community wellbeing [ 42 ], informed a structured search strategy, which was refined to remove false positives (excess unrelated papers). The search strategy focused on three factors: what were initiatives trying to achieve (what), the approach or philosophy they followed (how), and the area in which they worked (where). Results were limited to 2000–2019. The search strategy was developed in Medline and adapted for CINAHL, Web of Science, Psychinfo, Sociology Source and Cochrane library. The initial search strategy was deliberately broad to encapsulate the diversity of terms commonly used in this field. The search terms used, in Boolean structure of What AND How AND Where , were: ([wellbeing OR well-being OR mental health OR social determinant OR flourishing OR resilience OR social capital OR social cohesion OR salutogen* OR positive psychology] AND [ecological approach OR grassroot OR community driven OR capacity building OR empowerment OR engagement OR collective impact OR community development OR public health] AND [communit* OR local OR neighbo* OR city OR town]).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were refined via reflective collaborative discussion. Evidence type was restricted to primary papers to enable a primary analysis of process themes for this review. This included process and outcome evaluations. Commentaries and secondary analysis or theoretical papers were excluded but reserved for consideration for inclusion in introduction and/or discussion. Community settings were included, whilst papers focused on more restrictive settings such as school, prisons and aged care were excluded. Initiatives required community involvement and a wellbeing focus. Papers were excluded if the focus was not wellbeing, if it was clearly top-down, externally applied or if there was insufficient detail to describe the initiative activities, processes and governance.

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis

Data extraction: All authors designed an analytical framework from which the data extraction tool was developed (Supplementary Table S1 ). Two authors (NP and JLB) reviewed each included paper using the data extraction tool to create a comprehensive dataset. Details of the initiatives were summarised and encompassed key details, formative and process factors.

A combination of content and thematic analysis [ 43 ] was used to identify themes and concepts within the dataset. The content analysis mapped to existing theories [ 17 , 44 , 45 , 46 ] of community health initiatives to develop themes on the factors that contributed to the functioning of the initiatives. The processes of the initiatives were thematically grouped, coded and discussed by the authors until a coding framework of eight themes was developed, with sub-coding within a matrix to illustrate developmental stages over time. This was developed iteratively with author discussion and regular comparison to the twelve exemplar initiatives and primary themes (NP, HD, DP). Each stage of the thematic analysis was conducted by at least two authors. NVivo was used to organise the themes and the included papers were reanalysed against the coding framework.

Search results

The search returned 8972 results without duplicates. Title and abstract screening excluded 8784 records. Following the search strategy (Fig. 1 ), two authors (NP and JLB) read half of the papers each and compared notes. Disagreements were resolved in discussions with a third author (HD). A total of 17 papers describing twelve separate initiatives were identified. Google Scholar was searched for all literature related to these twelve initiatives, with 26 additional papers found, primarily related to two initiatives.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) four-phase flow diagram

Context of the initiatives

The twelve exemplar initiatives employed different approaches and came from numerous countries – one each from New Zealand, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America (USA), two from Australia and six from the United Kingdom (UK). Key details of these initiatives are summarized in Table 1 .

Wellbeing approaches of the initiatives

To promote mental health and wellbeing, all initiatives encouraged the social dimensions of community, working to build social capital and many using community champions (initiatives # 3, 7, 11) and encouraging volunteerism (initiatives #2, 8, 9, 10). Typical health promotion activities were commonly used, including training (initiatives #3, 7, 9, 11, 12), raising awareness, de-stigmatising conversations, encouragement of self-reflection on what wellbeing and resilience meant to individuals, use of campaigns and tools such as ‘Five ways to wellbeing’ [ 86 ] (initiative #12) and providing opportunities for safe and social interactions (pop-up hubs, youth spaces, and community events). Others explicitly recognised the social and economic determinants of health and were also addressing those (initiatives #1, 2, 5, 10).

What assisted the initiatives to function?

We found eight key themes associated with successful community mental wellbeing initiatives (summarised under ‘principles’ in Fig. 2 ). The way that communities understood and exhibited each of these themes changed over time. For example, initial community engagement often focused on gathering community opinion and later developed into planning events and participation in working groups. The stages of the initiatives are iterative and there was no consistent developmental process – therefore these stages are more a set of component processes to be developed and monitored, rather than a definitive sequence. Each of these broad themes was found in at least eleven of the twelve initiatives and can be thought of as principles that underpinned the initiatives. Moreover, these principles were operationalised as different processes at different phases (‘initiation and planning’, ‘implementation’ and ‘continuation and sustainability’) and are summarised in Fig. 2 . The coding references for these principles and processes mapped against each initiative can be accessed in Supplementary Table S2 .

Framework for community wellbeing initiatives – key principles and processes

1. Community alignment – align with community needs, strengths, and history – adapt to context

The community initiatives included were sensitive to the context in which they operated. During initiation and planning, the collection of subjective and objective data enabled a contextual understanding of community need. The general community was asked what they wanted to change (10 of 12 initiatives), and publicly available community data was reviewed (9 of 12 initiatives), highlighting community assets and helping to prioritise needs. As some of the initiatives began to put this information into action, they took care to not duplicate existing activities (2 of 12 initiatives), which can cause wasted energy, community confusion and detract from the credibility of and support for the initiative. As the initiatives matured it was important to consult the community regularly (4 of 12 initiatives) to ensure that the initiative was adaptive and responsive to changes.

2. Community ownership – encourage bottom-up energy to build community ownership

The first step to generate community ownership, was to keep the community voice and vision as the anchor point for all planning and leadership (8 of 12 initiatives). This was achieved through community representation, but some initiatives navigated the concept of representation, with particular representatives having multiple roles. For example, if a professional member of the leadership group was appointed to represent their organisation, could they also be a resident representative? This raised considerations of conflicts of interest and how to handle them. Secondly, the ideas of empowerment and ownership are entwined. Capacity building of champions and volunteers were considered important steps to making their initiatives more acceptable and sustainable in the community (9 of 12 initiatives). Giving the community flexible opportunities to contribute to the initiative in ways that suit members was also important (8 of 12 initiatives). This allowed community members to “dial in and out” of the initiative depending on their interests and commitments.

3. Engaged community – include community in strategy and action to build trust

Five initiatives brought the community together to discuss the future, which was key to their planning and visioning, and may have played a role in engaging community members in leadership or working group positions. Diverse combinations of activities and networks were used to engage with a broad range of community members (11 of 12 initiatives). This is a recognition that not all community members can be reached through traditional networks and that not all activities will engage all community members. It was recognised that in the long term, tangible action and change in the community were key to engaging more people (3 of 12 initiatives).

4. Shared purpose – establish based on a collective understanding of wellbeing

A shared vision that reflected the community voice and aligned with the local context was an important factor in the organisation of initiatives (11 of 12 initiatives). Since wellbeing is a subjective term for individuals and communities, the visions were often based on a local understanding or definition. The desire to create an agreed community vision was undercut by concerns that many initiatives developed a vision based on influential, generally upper middle-class concerns of a subset of the community, rather than being truly representative. The shared visions were translated into specific goals or plans by at least nine of the initiatives. The importance of committing to the long term was raised, since the desired social change could not be achieved in the one to two years that were commonly funded (5 of 12 initiatives). To keep initiatives on track, the consistent linking of activities back to the overarching purpose helped get community involved and keep the leadership and working groups motivated (6 of 12 initiatives). Three initiatives recognised that the human value in the purpose of their initiative helped sustain the initiative through challenges.

5. Collaborative action – form and maintain relationships and partnerships

The selected initiatives had a locally based, collaborative leadership team (12 of 12 initiatives). The ways in which these teams arose differed, with some aided by an external organisation visiting the community and assisting in building a community leadership group (2 of 12 initiatives), others formed leadership groups as a result of local energy (3 of 12 initiatives), although they were assisted by external support to establish and legitimise their initiative.

Collaborative action was evident (11 of 12 initiatives). This included collaboration between community members, local council, health and mental health services, the education system, law enforcement, researchers, local businesses, and voluntary organisations. Many described the formation of a collaborative leadership and governance structure in the form of a steering committee (9 of 12 initiatives). The importance of partnering and supporting relevant community activities was outlined (6 of 12 initiatives). Assistance was sought for certain activities, including workshop facilitation, needs assessments, obtaining funding and evaluation (10 of 12 initiatives). Some of this external support also relied upon government intervention, especially on the issues that cannot be addressed by a community initiative. On these issues, some of the initiatives advocated to government, rather than assume responsibility for endemic issues (e.g., poor employment opportunities, housing or recreation space).

6. Transparent communication – openly communicate with community and partners, including promotion activities

Active communication between the initiative and the broader community was used to engage the community for initial discussion; to involve members as leaders, volunteers, or champions to advertise the purpose and vision of the initiative; to publicise the plan; to advertise sponsored or organised activities; and to list key community contacts for support or involvement (8 of 12 initiatives). This was achieved through promotion in traditional and new media (9 of 12 initiatives), through established networks and word of mouth. Communication between members of the initiative was important for cohesion and enabling democratic elements of decision making (8 of 12 initiatives). Development of a coherent narrative was key to the overall communication and engagement strategy (6 of 12 initiatives). Consistent explanation of the link between the activities of the initiative and the overall purpose was valued (8 of 12 initiatives). Celebrating short-term successes and promoting the long-term vision can illustrate that worthwhile change is possible and occurring (7 of 12 initiatives).

7. Continuous learning – monitor and evaluate activities

Each initiative adapted over time as they learned how to operate and be effective (12 of 12 initiatives). Continuous learning and improvement through monitoring and evaluating activities was described (11 of 12 initiatives). In the organisation stage, some made a point to record how decisions and actions were planned (4 of 12 initiatives). As the initiatives were implementing activities, solving problems and learning from success and failure were key parts of the initiative’s maturation (8 of 12 initiatives). To work towards sustainability in their community, progress reviews were central (11 of 12 initiatives) and helped initiatives to evolve as community needs and assets changed.

8. Resource management – secure and use resources flexibly

Several of the initiatives were described from the perspective of the funders, making it challenging to assess the financial resource dimension. Some initiatives were established only as funding was secured; others secured funding as they went along. Funding was often discussed, including receipt or application for funding and how relationships with funders were managed (7 of 12 initiatives). Small grants for very specific activities, often short term, were easier to obtain in some communities (5 of 12 initiatives). The gathering of non-fiscal resources was discussed by more initiatives than fiscal ones (10 of 12 initiatives). The importance of bringing in organisations and people with the networks and resources to support the initiative was identified, particularly in the early stages (9 of 12 initiatives). While networks and resources were particularly important in the planning stage, people with particular skills who could act as leaders, champions and volunteers were valuable in implementation and maturation. Finally, the importance of a history of action and success in securing new resources was discussed (2 of 12 initiatives). Grant applications were more successful if the initiative demonstrated a strong track record. Also, local organisations and individuals were more likely to contribute towards the initiative when they see that it is a realistic pathway to change.

In this study, we have sought to identify the principles and processes employed by successful community led initiatives to improve mental health and wellbeing. Success in this case was measured by duration of initiative (greater than two years) and supportive evidence of the initiative’s process development or outcomes in the literature. Twelve exemplar community-built wellbeing initiatives were identified. From these, detailed analysis yielded eight key themes (principles) associated with the factors that contributed to the functioning of the initiatives. These principles were community alignment, community ownership, community engagement, shared purpose, collaborative action, transparent communication, continuous learning, and resource management. These were expanded into a matrix to illustrate how the principles were enacted in practice (processes) over the developmental stages of initiation and planning, implementation, and continuation and sustainability. Thus, there is a matrix of component processes associated with how these initiatives were able to collaboratively address mental health and wellbeing in their communities in response to local need and with local ownership. These may be of interest and use for other collaborative initiatives aimed at addressing wellbeing.

Wellbeing is a complex phenomenon, which the twelve exemplar initiatives addressed multidimensionally, deliberately and contextually. The community alignment principle was exemplified by capturing community needs and strengths, both subjectively by listening to community members and objectively via public data sources, e.g. [ 80 ]. These included activities to enhance social connection, increase volunteering, access to support, access to leisure and hobbies, access to green and blue spaces and other social determinants of health that are supported in broader research [ 12 , 41 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 ]. Activities were chosen in response to community aspirations, the shared purpose, building both community ownership and engagement. Extensive community involvement in the initiatives was evident, providing information regarding need, collaborative planning and action, leveraging with partners and engaging with the wider community. This aligns with the weight of evidence which suggests that community codesign, empowerment or ownership are strongly linked to success, effectiveness and sustainability of health and behaviour change initiatives [ 91 ].

Community ownership was found to be a key principle; however, the evidence also suggested the importance of external support which could enable complex change in a community (bridging the principles of resource management and collaborative action). Therefore, some level of authority or decision-making power contributing top-down (outside-in) support in combination with bottom-up (inside-out) support and energy are essential for sustainability [ 92 , 93 ]. This raises an important point about power management within community initiatives [ 94 ]. The findings presented here support the broader literature, suggesting that the role of authority figures is to enable and aid the community to realise the codesigned vision [ 92 , 95 ]. The general recommendations from community public health initiatives are to enable a community to contribute and develop agency, that is, health interventions done with communities, not to communities [ 91 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 ]. As such, when the goals of an initiative are closely aligned with those of local government, cross sector collaboration flourishes (community alignment and collaborative action principles) [ 103 , 104 , 105 ].

Most of the community initiatives operated at a level between local government and the public. While power management was a consideration for most, the question of capacity and capabilities (resource management) was also relevant in deciding upon vision, goals, objectives, responsibilities and contributions [ 80 , 106 ]. Every community has local organisations with capacity to enact change at some level within the community. Whilst no single partner organisation might be essential for community initiatives, each partner opens new opportunities, and these partners may influence both ambitions and the ability to realise them (collaborative action). In order to understand community change, we must acknowledge that there are other networks, structures and systems that influence and can be leveraged to influence the overall outcome [ 107 , 108 ].

Transparent communication was a key principle, and was used by the included initiatives to traverse the developmentally vulnerable stage of initiation and planning [ 109 ]. Communication of short-term achievements and celebrations was used to build momentum, grassroots support and help reinforced a sense of realistic expectations. Active communication strategies can help build a coherent narrative and link activities to the shared purpose. However, for true change, the many factors that influence wellbeing in the community must be improved upon and be seen to be improving. There is evidence that citizens perceptions of their community and their pride in community are closely linked to the way they talk about their life satisfaction and mental wellbeing, and may be a key pragmatic measure for initiative success [ 78 , 110 , 111 ].

The challenges of evaluating the success of community-based initiatives persist [ 112 ], with attribution of causation especially difficult [ 113 , 114 ]. As noted earlier, a Cochrane review of community coalition-driven interventions [ 12 ] found evidence for positive benefit to individual health outcomes and behaviours, and care delivery systems. There was insufficient evidence on the workings of the coalitions themselves to explain how benefits were achieved, indicating a gap in process evidence. Whilst capturing both the process and the outcome is valued by the researcher, consideration should be given to the burden of documentation in a community-driven initiative should be given. There is a delicate balance between maintaining formal mechanisms and processes to track an initiative without intimidating or overpowering community voice and resourcefulness [ 114 , 115 ]. This study highlights that the documentation of initiative processes and activities supports three of the eight principles directly: the ability to share information and build the common narrative (transparent communication), to reflect and learn (continuous learning), and to leverage future funds with evidence of activity and impact (resource management). This may be a valuable strategy since short, fixed-term funding was identified as a key challenge for resource management and sustainability, which can lead to diminished trust for future initiatives [ 116 , 117 ]. By addressing documentation and evaluation of processes, activities and outcomes, further funds and resources may be secured, thus, providing the time needed to build and retain trust in the community wellbeing initiative. In recognition of the persistent challenge of short-term funding, contrasted with the acknowledged need for time to build trust and genuine collaborative action, policymakers and funders need to adjust to longer time spans. There are some relatively new philanthropic initiatives with explicitly longer time horizons of 10 or more years to address this and to genuinely work with communities for the duration of investment. These include the Hogg Foundation’s Collaborative Approaches to Well-Being in Rural Communities program in Texas [ 118 ], and the Fay Fuller Foundation’s Our Town program in South Australia [ 119 ]. These new funding approaches remain the exception, not the norm.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths: This study has focused on the processes of how community wellbeing initiatives develop and function, where most papers focus on short-term outcomes. It has covered a wide range of papers written by academics and others from a variety of disciplines using a variety of similar, overlapping, and distinct terminology. We have attempted to address temporal issues recognizing that needs for leadership, resources and engagement vary over time and due to changing circumstances. We have suggested a common language/framework which is accessible to communities, not just community development or other professionals.

Limitations: We could only analyse what has been published which is limited in many ways. Initiative processes are often poorly described or assumed, important components are missed out, and papers are written from particular perspectives or with partial perspectives. Our included initiatives had variable volumes of evidence with some having one paper, others many, and up to 14 papers for Well London. Some initiatives are not described or published and therefore there is likely a lot we don’t know. While considerable effort was made to find and select appropriate materials, we may have missed something. There is no common measurement of outcomes, although the variety of contexts may invalidate such comparisons [ 120 ]. Moreover, due to the varying reporting on outcomes, our criteria for selecting successful cases was limited to implementation success, as measured by (i) duration of existence (at least two years) and (ii) have published evidence regarding the initiative (e.g. peer-reviewed article). We also note that the initiatives included all come from Western democracies, predominantly English-speaking countries, and thus the process characteristics outlined here may not apply in other national and cultural contexts.

This review took a rigorous approach to finding twelve exemplar communities, which had successfully implemented community wellbeing initiatives. The focus on how the initiatives were implemented and sustained should aid interested communities to grow their own initiatives and may be used by other studies to design projects that can assess success and impact.

Data availability

Not applicable.

World Health Organization. Health Topics - Mental Health Burden Geneva2022 [ https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_2 .

Burke S, Enticott J, Isaacs A, Meadows G, Rosenberg SP. Critical environmental and social determinants of mental health problems and their care. In: Meadows G, Farhall J, Fossey E, Happell B, McDermott F, Rosenberg S, et al. editors. Mental Health and Collaborative Community Practice. Australia: Oxford University Press; 2020. pp. 30–47.

Google Scholar

Lawrence-Bourne J, Dalton H, Perkins D, Farmer J, Luscombe G, Oelke N, et al. What is rural adversity, how does it affect wellbeing and what are the implications for action? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:19.

Article Google Scholar

Productivity Commission. Mental Health, Report no. 95. Canberra2020.

National Mental Health Commission. Monitoring mental health and suicide prevention reform: National Report 2019. Sydney: NMHC; 2019.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10128):1357–66.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bear HA, Edbrooke-Childs J, Norton S, Krause KR, Wolpert M. Systematic review and Meta-analysis: outcomes of routine specialist Mental Health Care for Young People with Depression and/or anxiety. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(7):810–41.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Herrman H. The need for Mental Health Promotion. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(6):709–15.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Knapp M, McDaid D, Parsonage M. Mental health promotion and mental illness prevention: the economic case. London: Department of Health; 2011.

Donovan RJ, Henley N, Jalleh G, Silburn SR, Zubrick SR, Williams A. People’s beliefs about factors contributing to mental health: implications for mental health promotion. Health Promot J Austr. 2007;18(1):50–6.

Ryan RM, Huta V, Deci EL. Living well: a self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. J Happiness Stud. 2008;9:139–70.

Anderson LM, Adeney KL, Shinn C, Safranek S, Buckner-Brown J, Krause LK. Community coalition-driven interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(6):Cd009905.

International conference on. primary health care. Declaration of Alma-Ata. 1978.

No authorship i. Declaration of ALMA-ATA. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1094–5.

World Health Organization. Ottawa charter for health promotion. Geneva; 1987.

World Health Organization. Healthy Cities Effective Approach to a Changing World. Geneva; 2020.

Laverack G. Improving health outcomes through community empowerment: a review of the literature. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006:113–20.

Marmot MG. Empowering communities. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):230–1.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Douglas JA, Grills CT, Villanueva S, Subica AM. Empowerment Praxis: Community Organizing to redress systemic Health disparities. Am J Community Psychol. 2016;58(3–4):488–98.

Ehsan A, Klaas HS, Bastianen A, Spini D. Social capital and health: a systematic review of systematic reviews. SSM Popul Health. 2019;8:100425.

Ehsan AM, De Silva MJ. Social capital and common mental disorder: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(10):1021–8.

Marmot M. Universal health coverage and social determinants of health. Lancet. 2013;382(9900):1227–8.

Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, Bloomer E, Goldblatt P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380(9846):1011–29.

Stansfield J, South J, Mapplethorpe T. What are the elements of a whole system approach to community-centred public health? A qualitative study with public health leaders in England’s local authority areas. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e036044.

Boyle D. A history of community development. Linking the stories that connect community organisers across the world, from 1940–2020 [Essay]. Local Trust; 2021 [ https://longreads.localtrust.org.uk/2021/05/01/a-history-of-community-development/ .

Hystad P, Carpiano RM. Sense of community-belonging and health-behaviour change in Canada. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2012;66(3):277–83.

Kearns A, Whitley E. Are housing and neighbourhood empowerment beneficial for mental health and wellbeing? Evidence from disadvantaged communities experiencing regeneration. SSM Popul Health. 2020;12:100645.

Dooris M, Farrier A, Froggett L. Wellbeing: the challenge of ‘operationalising’ an holistic concept within a reductionist public health programme. Perspect Public Health. 2018;138(2):93–9.

King C, Gillard S. Bringing together coproduction and community participatory research approaches: using first person reflective narrative to explore coproduction and community involvement in mental health research. Health Expect. 2019;22(4):701–8.

DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC. Emerging theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. p. 624.

Roy M, Levasseur M, Dore I, St-Hilaire F, Michallet B, Couturier Y, et al. Looking for capacities rather than vulnerabilities: the moderating effect of health assets on the associations between adverse social position and health. Prev Medicine: Int J Devoted Pract Theory. 2018;110:93–9.

Roy MJ. The assets-based approach: furthering a neoliberal agenda or rediscovering the old public health? A critical examination of practitioner discourses. Crit. 2017;27(4):455–64.

Perkins D, Farmer J, Salvador-Carulla L, Dalton H, Luscombe G. The Orange Declaration on rural and remote mental health. Aust J Rural Health. 2019;27(5):374–9.

Ereaut G, Whiting RA. What do we mean by ‘wellbeing’? and why might it matter? Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF); 2008. Report No.: ISBN 978 1 84775 271 0.

Fellin P. The community and the social worker. 3rd ed. Itasca, Ill.: F.E. Peacock; 2001.

Lee S, Kim Y. Searching for the meaning of Community Well-Being. In: Lee SJ, Kim Y, Phillips R, editors. Community Well-Being and Community Development SpringerBriefs in Well-Being and Quality of Life Research Cham. Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp. 9–23.

Lee SJ, Kim Y. Achieving community well-being through community participatory governance: the case of Saemaul Undong. Handbook of community well-being research. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media; US; 2017. pp. 115–28.

Bywater T, Berry V, Blower SL, Cohen J, Gridley N, Kiernan K, et al. Enhancing Social-Emotional Health and Wellbeing in the early years (E-SEE): a study protocol of a community-based randomised controlled trial with process and economic evaluations of the incredible years infant and toddler parenting programmes, delivered in a proportionate universal model. BMJ Open. 2018;8(12):e026906.

Cox D, Frere M, West S, Wiseman J. Developing and using local community wellbeing indicators: learning from the experience of community indicators Victoria. Australian J Social Issues (Australian Council Social Service). 2010;45(1):71–88.

Kim Y, Kee Y, Lee S. An analysis of the relative importance of components in Measuring Community Wellbeing: perspectives of Citizens, Public officials, and experts. Soc Indic Res. 2015;121(2):345–69.

Hunter BD, Neiger B, West J. The importance of addressing social determinants of health at the local level: the case for social capital. Health Soc Care Community. 2011;19(5):522–30.

Powell N, Dalton H, Perkins D, Review. A collaborative approach to community mental wellbeing. Orange NSW Centre for Rural and Remote Mental Health, University of Newcastle; 2018.

Ezzy D. Qualitative analysis: practice and innovation. Crows nest. New South Wales: Allen & Unwin; 2002.

Nutbeam D. What would the Ottawa Charter look like if it were written today? Crit. 2008;18(4):435–41.

Popay J, Attree P, Hornby D, Milton B, Whitehead M, French B et al. Community engagement in initiatives addressing the wider social determinants of health A rapid review of evidence on impact, experience and process. Social Determinants Eff Rev. 2007.

Atkinson S, Bagnall A, Corcoran R, South J. What is community wellbeing? Conceptual review. Leeds, UK: Leeds Beckett University; 2017.

Adams J, Witten K, Conway K. Community development as health promotion: evaluating a complex locality-based project in New Zealand. Community Dev J. 2009;44(2):140

Cheuy S, Fawcett L, Hutchinson K, Robertson T. A citizen-led approach to enhancing community well-being. Handbook of community well-being research. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media; US; 2017. p. 129–67.

Corbie-Smith G, Yaggy SD, Lyn M, Green M, Ornelas IJ, Simmons T, et al. Development of an Interinstitutional Collaboration to Support Community-Partnered Research Addressing the Health of Emerging Latino Populations. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):728–35.

Green MA, Perez G, Ornelas IJ, Tran AN, Blumenthal C, Lyn M, et al. Amigas Latinas Motivando el ALMA (ALMA): Development and Pilot Implementation of a Stress Reduction Promotora Intervention. Calif J Health Promot. 2012;10:52–64.

Perez G, Della Valle P, Paraghamian S, Page R, Ochoa J, Palomo F, et al. A community-engaged research approach to improve mental health among latina immigrants: ALMA Photovoice. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17(3):429–39.

Ryan D, Maurer S, Lengua L, Duran B, Ornelas IJ. Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma (ALMA): an Evaluation of a Mindfulness Intervention to Promote Mental Health among Latina Immigrant Mothers. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2018;45(2):280–91.

Tran AN, Ornelas IJ, Kim M, Perez G, Green M, Lyn MJ, et al. Results from a pilot promotora program to reduce depression and stress among immigrant Latinas. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(3):365–72.

Tran AN, Ornelas IJ, Perez G, Green MA, Lyn M, Corbie-Smith G. Evaluation of Amigas Latinas Motivando el Alma (ALMA): a pilot promotora intervention focused on stress and coping among immigrant Latinas. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(2):280–9.

Draper A, Clow A, Lynch R, Jain S, Philips G, Petticrew M, et al. Building a logic model for a complex intervention: a worked example from the Well London CRCT. . In Population Health: Methods and Challenges, MRC Conference; Birmingham 2012.

Derges J, Lynch R, Clow A, Petticrew M, Draper A. Complaints about dog faeces as a symbolic representation of incivility in London, UK: a qualitative study. Crit. 2012;22(4):419–25.

Renton A, Phillips G, Daykin N, Yu G, Taylor K, Petticrew M. Think of your art-eries: arts participation, behavioural cardiovascular risk factors and mental well-being in deprived communities in London. Public Health. 2012;126 Suppl 1(5):S57–s64.

Phillips G, Renton A, Moore DG, Bottomley C, Schmidt E, Lais S, et al. The Well London program--a cluster randomized trial of community engagement for improving health behaviors and mental wellbeing: baseline survey results. Trials. 2012;13:105.

Derges J, Clow A, Lynch R, Jain S, Phillips G, Petticrew M, et al. 'Well London' and the benefits of participation: results of a qualitative study nested in a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e003596.

Phillips G, Bottomley C, Schmidt E, Tobi P, Lais S, Ge Y, et al. Measures of exposure to the Well London Phase-1 intervention and their association with health well-being and social outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(7):597–605.

Phillips G, Bottomley C, Schmidt E, Tobi P, Lais S, Yu G, et al. Well London Phase-1: results among adults of a cluster-randomised trial of a community engagement approach to improving health behaviours and mental well-being in deprived inner-city neighbourhoods. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(7):606–14.

Sheridan K, Adams-Eaton F, Trimble A, Renton A, Bertotti M. Community engagement using World Café: The well London experience. Groupwork. 2010;20(3):32–50.

Wall M, Hayes R, Moore D, Petticrew M, Clow A, Schmidt E, et al. Evaluation of community level interventions to address social and structural determinants of health: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:207.

Edmonds N. Well London: Mental well being impact assessment project report. 2009 [March, 20, 2022]. Available from: https://www.welllondon.org.uk/39/mental-well-being-impact-assessment.html .

Bertotti M, Adams-Eaton F, Sheridan K, Renton A. Key Barriers to Community Cohesion: Views from Residents of 20 London Deprived Neighbourhoods. Geo J. 2012;77(2):223–34.

Wittenberg R, Findlay G, Tobi P. Costs of the Well London programme. In: Unit PSSR, editor. Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2016. Canterbury 2016. pp.12–6.

Frostick C, Watts P, Netuveli G, Renton A, Moore D. Well London: Results of a Community Engagement Approach to Improving Health Among Adolescents from Areas of Deprivation in London. J Com Prac. 2017;25(2):235–52.

Tobi P, Kemp P, Schmidt E. Cohort differences in exercise adherence among primary care patients referred for mental health versus physical health conditions. Pri Health Care Res Dev. 2017;18(5):463–71.

Giovannini M. Indigenous community enterprises in Chiapas: a vehicle for buen vivir? Community Dev J. 2015;50(1):71–87.

Giovannini M. Social enterprises for development as. J Enterpr Com: People Place Global Eco. 2012;6(3):284–99.

Haswell-Elkins M, Reilly L, Fagan R, Ypinazar V, Hunter E, Tsey K, et al. Listening, sharing understanding and facilitating consumer, family and community empowerment through a priority driven partnership in Far North Queensland. Australas Psychiatry. 2009;17 Suppl 1:S54–8.

Mantovani N, Pizzolati M, Gillard S. Engaging communities to improve mental health in African and African Caribbean groups: a qualitative study evaluating the role of community well-being champions. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(1):167–76.

Mantovani N, Pizzolati M, Gillard S. “Using my knowledge to support people”: A qualitative study of an early intervention adopting community wellbeing champions to improve the mental health and wellbeing of African and African Caribbean communities: St George’s University of London; 2014.

Lewis S, Bambra C, Barnes A, Collins M, Egan M, Halliday E, et al. Reframing ‘participation’ and ‘inclusion’ in public health policy and practice to address health inequalities: Evidence from a major resident-led neighbourhood improvement initiative. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27(1):199–206.

McGowan VJ, Wistow J, Lewis SJ, Popay J, Bambra C. Pathways to mental health improvement in a community-led area-based empowerment initiative: evidence from the Big Local ‘Communities in Control’ study, England. J Public Health (Oxf). 2019;41(4):850–7.

Orton L, Ponsford R, Egan M, Halliday E, Whitehead M, Popay J. Capturing complexity in the evaluation of a major area-based initiative in community empowerment: what can a multi-site, multi team, ethnographic approach offer? Anthropol Med. 2019;26(1):48–64.

Saunders P, Campbell P, Webster M, Thawe M. Analysis of Small Area Environmental, Socioeconomic and Health Data in Collaboration with Local Communities to Target and Evaluate ‘Triple Win’ Interventions in a Deprived Community in Birmingham UK. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22).

Halliday E, Collins M, Egan M, Ponsford R, Scott C, Popay J. A ‘strategy of resistance’? How can a place-based empowerment programme influence local media portrayals of neighbourhoods and what are the implications for tackling health inequalities? Health Place. 2020;63:102353.

Ponsford R, Collins M, Egan M, Halliday E, Lewis S, Orton L, et al. Power, control, communities and health inequalities. Part II: measuring shifts in power. Health Promot Int. 2021;36(5):1290–9.

Powell N, Dalton H, Perkins D, Considine R, Hughes S, Osborne S, et al. Our healthy Clarence: A Community-Driven Wellbeing Initiative. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(19):30.

Richardson J, Nichols A, Henry T. Do transition towns have the potential to promote health and well-being? A health impact assessment of a transition town initiative. Public Health. 2012;126(11):982–9.

Gui X, Nardi B, editors. Sustainability begins in the street: A story of Transition Town Totnes. EnviroInfo and ICT for Sustainability 2015; 2015: Atlantis Press.

Woodall J, White J, South J. Improving health and well-being through community health champions: a thematic evaluation of a programme in Yorkshire and Humber. Perspect Public Health. 2013;133(2):96–103.

White J, South J, Woodall J, Kinsella K. Altogether Better Thematic Evaluation - Community Health Champions and Empowerment. Leeds: Centre for Health Promotion Research, Leeds Metropolitan University; 2010.

Zeidler M, Zeidler L, Lee B. Positive psychology at a city scale. The Routledge international handbook of critical positive psychology. Routledge international handbooks. New York, NY, US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2018. p. 523–31.

Aked J, Marks N, Cordon C, Thompson S. Five ways to wellbeing. UK; 2008. p. 22.

Perez E, Braen C, Boyer G, Mercille G, Rehany E, Deslauriers V et al. Neighbourhood community life and health: a systematic review of reviews. Health Place. 2019:102238.

Raphael D, Renwick R, Brown I, Steinmetz B, Sehdev H, Phillips S. Making the links between community structure and individual well-being: community quality of life in Riverdale, Toronto, Canada. Health Place. 2001;7(3):179–96.

Houlden V, Weich S, Porto de Albuquerque J, Jarvis S, Rees K. The relationship between greenspace and the mental wellbeing of adults: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0203000.

Kahana E, Bhatta T, Lovegreen LD, Kahana B, Midlarsky E. Altruism, helping, and volunteering: pathways to well-being in late life. J Aging Health. 2013;25(1):159–87.

O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, Thomas J. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:129.

Baum F. Cracking the nut of health equity: top down and bottom up pressure for action on the social determinants of health. Promot Educ. 2007;14(2):90–5.

Singer J, Bennett-Levy J, Rotumah D. You didn’t just consult community, you involved us: transformation of a ‘top-down’ Aboriginal mental health project into a ‘bottom-up’ community-driven process. Australas. 2015;23(6):614–9.

Wolff T, Minkler M, Wolfe SM, Berkowitz B, Bowen L, Butterfoss FD et al. Collaborating for equity and justice: moving beyond collective impact. Nonprofit Q. 2017:42–53.

Cooper LA, Purnell TS, Showell NN, Ibe CA, Crews DC, Gaskin DJ, et al. Progress on Major Public Health challenges: the importance of equity. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(1suppl):S15–9.

Pfefferbaum B, Pfefferbaum RL, Van Horn RL. Community resilience interventions: participatory, assessment-based, action-oriented processes. Am Behav Sci. 2015;59(2):238–53.

Bromley E, Figueroa C, Castillo EG, Kadkhoda F, Chung B, Miranda J, et al. Community Partnering for Behavioral Health Equity: Public Agency and Community leaders’ views of its Promise and Challenge. Ethn Dis. 2018;28(Suppl 2):397–406.

Holden K, Akintobi T, Hopkins J, Belton A, McGregor B, Blanks S et al. Community Engaged Leadership to Advance Health Equity and Build healthier communities. Soc Sci (Basel). 2016;5(1).

Pastor M, Terriquez V, May L. How Community Organizing Promotes Health Equity, and how Health Equity affects Organizing. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(3):358–63.

Reid A, Abraczinskas M, Scott V, Stanzler M, Parry G, Scaccia J, et al. Using Collaborative Coalition Processes to Advance Community Health, Well-Being, and equity: a multiple-case study analysis from a National Community Transformation Initiative. Health Educ Behav. 2019;46(1suppl):S100–9.

Torres S, Labonte R, Spitzer DL, Andrew C, Amaratunga C. Improving health equity: the promising role of community health workers in Canada. Healthc Policy. 2014;10(1):73–85.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Davis EJ. Collaborative processes and connection to Community Wellbeing. Eugene, Oregon: University of Oregon; 2021.

Rosen J, O’Neill M, Hutson M. The important role of government in Comprehensive Community initiatives: a Case Study Analysis of the Building Healthy communities Initiative. J Plann Educ Res. 2022;42(3):350–64.

Turner D, Martin S. Social Entrepreneurs and social inclusion: building local capacity or delivering National priorities? Int J Public Adm. 2005;28(9/10):797–806.

Gratzer D, Goldbloom D. ThriveNYC is ambitious—lessons from the International Experience with Mental Health Reform can make it successful. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:S166–7.

Hacker K, Tendulkar SA, Rideout C, Bhuiya N, Trinh-Shevrin C, Savage CP, et al. Community capacity building and sustainability: outcomes of community-based participatory research. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(3):349–60.

Hargreaves MB, Pecora PJ, Williamson G. Aligning Community Capacity, Networks, and solutions to address adverse childhood experiences and increase resilience. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(7S):S7–8.

Hargreaves MB, Verbitsky-Savitz N, Coffee-Borden B, Perreras L, White CR, Pecora PJ, et al. Advancing the measurement of collective community capacity to address adverse childhood experiences and resilience. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;76:142–53.

Butterfoss FD. Coalitions and partnerships in community health. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass; 2007. xxv, 579-xxv, p.

Halliday E, Popay J, Anderson de Cuevas R, Wheeler P. The elephant in the room? Why spatial stigma does not receive the public health attention it deserves. J Public Health (Oxf). 2018;42(1):38–43.

Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(1):125–39.

Todd H, editor. The Partners in Action Evaluation Project: A learning journey in building the evaluation capacity and evaluative culture of a local community coalition2015.

Flores EC, Fuhr DC, Bayer AM, Lescano AG, Thorogood N, Simms V. Mental health impact of social capital interventions: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(2):107–19.

Kadushin C, Lindholm M, Ryan D, Brodsky A, Saxe L. Why it is so difficult to Form Effective Community coalitions. City Community. 2005;4:255–75.

Muenchberger H, Kendall E, Rushton C. Pressure to perform: a content analysis of critical considerations in health coalition development. Leadersh Health Serv. 2012;25(3):186–202.

Hayes A, Freestone M, Day J, Dalton H, Perkins D. Collective impact approaches to promoting community health and wellbeing in a regional township: learnings for integrated care. Int J Integr Care. 2021;21(2).

Miller WD, Pollack CE, Williams DR. Healthy homes and communities: putting the pieces together. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1 Suppl 1):S48–57.

Hogg Foundation for Mental Health. Collaborative Approaches to Well-Being in Rural Communities [ https://hogg.utexas.edu/initiatives/collaborative-approaches-well-being-rural-communities .

Fay Fuller Foundation. Our Town [ https://www.fayfullerfoundation.com.au/focus/our-town .

Salvador-Carulla L, Lukersmith S, Sullivan W. From the EBM pyramid to the Greek temple: a new conceptual approach to guidelines as implementation tools in mental health. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26(2):105–14.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Debbie Booth, University of Newcastle Library, for her professional support to develop and refine our literature search strategy. We thank Centre for Rural and Remote Mental Health staff Rosie Dunnett, Corinna West, Joanna Joseph, Naomi Ruming and A/Prof Peter Simmons for providing critical and constructive feedback on the presentation of the thematic summaries in figure format. We thank the Global Leadership Exchange (GLE) – Rural Behavioral Health Collaborative for bringing new long-term funded initiatives mentioned in the discussion to our attention.

We acknowledge seed funding for the scoping review which formed the foundational concepts of this paper was provided by the NSW Mental Health Commission. From 2018 to 2021, NP, HD, JLB and DP were employed by the University of Newcastle Centre for Rural and Remote Mental Health, with core funding support from NSW Health, Mental Health Branch. HD acknowledges support for completing and publishing this paper via a grant from the Commonwealth of Australia, represented by the Department of Health (Grant Activity 4-DGEJZ1O/4-CW7UT14).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Independent researcher. Formerly Centre for Rural and Remote Mental Health, University of Newcastle, Orange, NSW, Australia

Nicholas Powell & Joanne Lawrence-Bourne

Rural Health Research Institute, Charles Sturt University, Orange, NSW, Australia

Hazel Dalton

School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

Healthy Minds Research Program, Hunter Medical Research Institute, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

Mental Health Policy Unit, Health Services Research Institute, University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Hazel Dalton & David Perkins

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

NP: conceptualization; search strategy; analysis strategy; formal analysis; draft and revised thematic summary; writing-original draft; writing-review & editing. HD: conceptualization; analysis strategy; revised thematic summary; figure preparation; writing-review & editing. JLB: formal analysis; draft thematic summary; review & editing. DP: funding acquisition; conceptualization; revised thematic summary; writing-review & editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hazel Dalton .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Powell, N., Dalton, H., Lawrence-Bourne, J. et al. Co-creating community wellbeing initiatives: what is the evidence and how do they work?. Int J Ment Health Syst 18 , 28 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-024-00645-7

Download citation

Received : 05 October 2023

Accepted : 09 July 2024

Published : 05 August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-024-00645-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Capacity building

- Collaborative

International Journal of Mental Health Systems

ISSN: 1752-4458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Community Mental Health Journal

Community Mental Health Journal is devoted to the evaluation and improvement of public sector mental health services for people affected by severe mental disorders, serious emotional disturbances and/or addictions.

- Coverage includes nationally representative epidemiologic projects, intervention research involving benefit and risk comparisons between service programs, and methodology, such as instrumentation, where particularly pertinent to public sector behavioral health evaluation or research.

- *Please note: All studies must be approved by human subjects committees (also known as institutional review boards). At the end of the Methods section, authors must state which human subject committee (IRB) approved the study.

This is a transformative journal , you may have access to funding.

- Sandra Steingard

Societies and partnerships

Latest issue

Volume 60, Issue 7

Latest articles

Bridging the gap of inequity in implementation science: adaptations of group ebps for those with serious mental illness in the public sector.

- Erika R. Carr

Programmatic and Organizational Barriers and Facilitators to Addressing High-Risk Issues in Supportive Housing and Housing First Programs

- Nick Kerman

- Timothy de Pass

- Vicky Stergiopoulos

Peer Support Workers in Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Exploration of Emotional Burden, Moral Distress and Strategies to Reduce the Risk of Mental Health Crisis

- Justyna Klingemann

- Halina Sienkiewicz-Jarosz

- Piotr Świtaj

Taking what you get or Getting what you Need: A Qualitative Study on Experiences with Mental Health and Welfare Services in Long-Term Recovery in First-Episode Psychosis

- Hanne Haavind

- Carmen Simonsen

Addressing Hispanic Veterans that Live in Rural Area’s Needs to Improve Suicide Prevention Efforts

- I. Magaly Freytes

- Nathaniel Eliazar-Macke

- Constance Uphold

Journal updates

Supporting the sustainable developmental goals.

New Article Type: Fresh Focus

Community Mental Health Journal is introducing a new article type, focusing on emerging topics of discussion within community psychiatry. The new article type, Fresh Focus, spans several possible formats and focus topics listed here.

Journal information

- Current Contents/Social & Behavioral Sciences

- Google Scholar

- Japanese Science and Technology Agency (JST)

- Norwegian Register for Scientific Journals and Series

- OCLC WorldCat Discovery Service

- Semantic Scholar

- Social Science Citation Index

- TD Net Discovery Service

- UGC-CARE List (India)

Rights and permissions

Editorial policies

© Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Community Psychology and Community Mental Health: A Call for Reengagement

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA.

- 2 Department of Psychology, DePaul University, Chicago, IL, USA.

- 3 Center for Research on Educational and Community Services, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

- PMID: 29315707

- DOI: 10.1002/ajcp.12225

Community psychology is rooted in community mental health research and practice and has made important contributions to this field. Yet, in the decades since its inception, community psychology has reduced its focus on promoting mental health, well-being, and liberation of individuals with serious mental illnesses. This special issue endeavors to highlight current efforts in community mental health from our field and related disciplines and point to future directions for reengagement in this area. The issue includes 12 articles authored by diverse stakeholder groups. Following a review of the state of community mental health scholarship in the field's two primary journals since 1973, the remaining articles center on four thematic areas: (a) the community experience of individuals with serious mental illness; (b) the utility of a participatory and cross-cultural lens in our engagement with community mental health; (c) Housing First implementation, evaluation, and dissemination; and (d) emerging or under-examined topics. In reflection, we conclude with a series of challenges for community psychologists involved in future, transformative, movements in community mental health.

Keywords: Community mental health; Community psychology; Serious mental illness; Transformative change.

© Society for Community Research and Action 2018.

Publication types

- Introductory Journal Article

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Community Mental Health Services

- Community Networks*

- Mental Health*

- Psychology, Social

- Severity of Illness Index

REVIEW article

Current insights of community mental healthcare for people with severe mental illness: a scoping review.

- 1 School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Tranzo Scientific Center for Care and Wellbeing, Tilburg University, Tilburg, Netherlands

- 2 Kwintes Housing and Rehabilitation Services, Zeist, Netherlands

- 3 Trimbos Institute, Dutch Institute of Mental Health and Addiction, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 4 HVO-Querido, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 5 Faculty of Social Sciences – HIVA, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

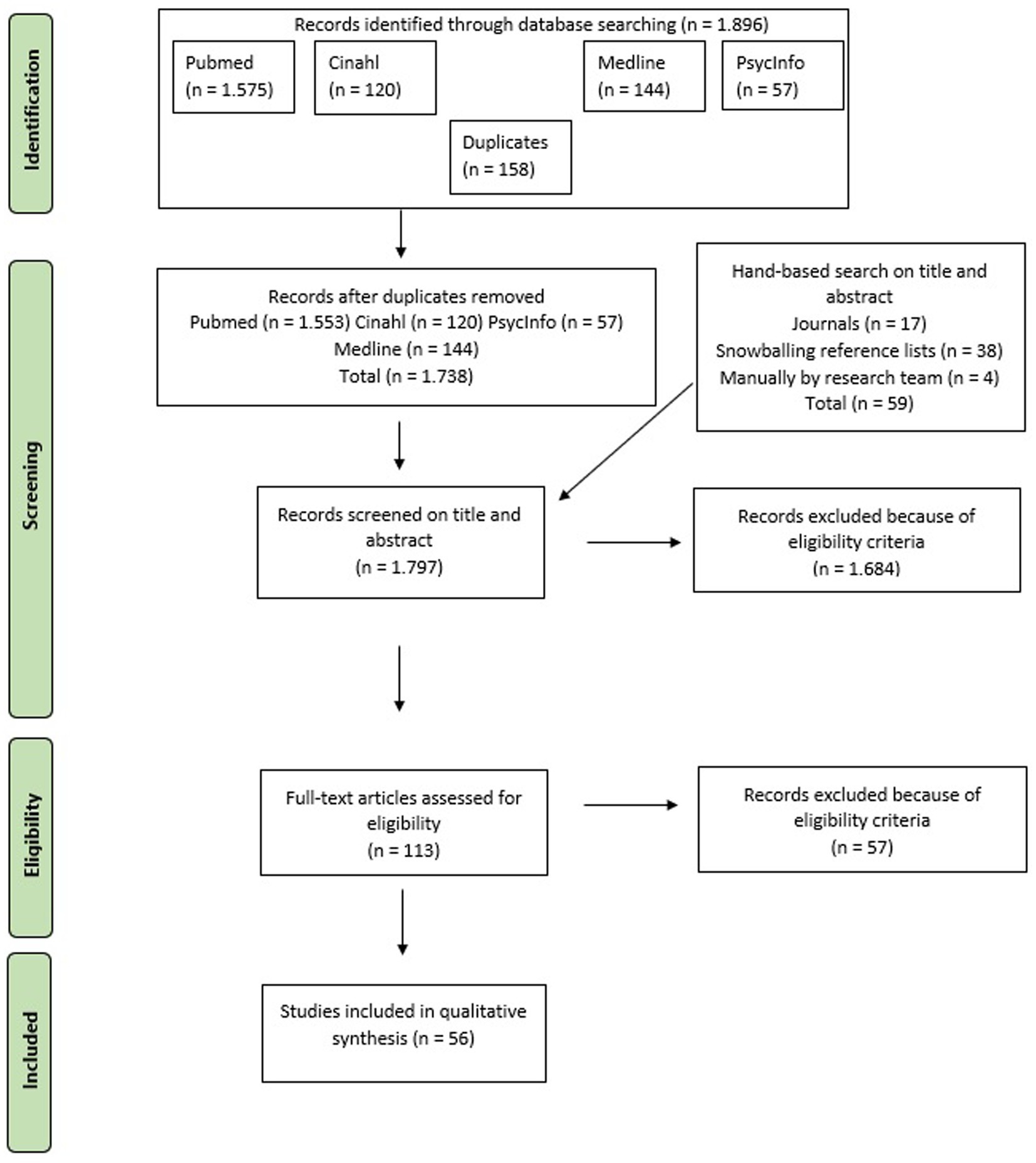

Background: For the last four decades, there has been a shift in mental healthcare toward more rehabilitation and following a more humanistic and comprehensive vision on recovery for persons with severe mental illness (SMI). Consequently, many community-based mental healthcare programs and services have been developed internationally. Currently, community mental healthcare is still under development, with a focus on further inclusion of persons with enduring mental health problems. In this review, we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of existing and upcoming community mental healthcare approaches to discover the current vision on the ingredients of community mental healthcare.

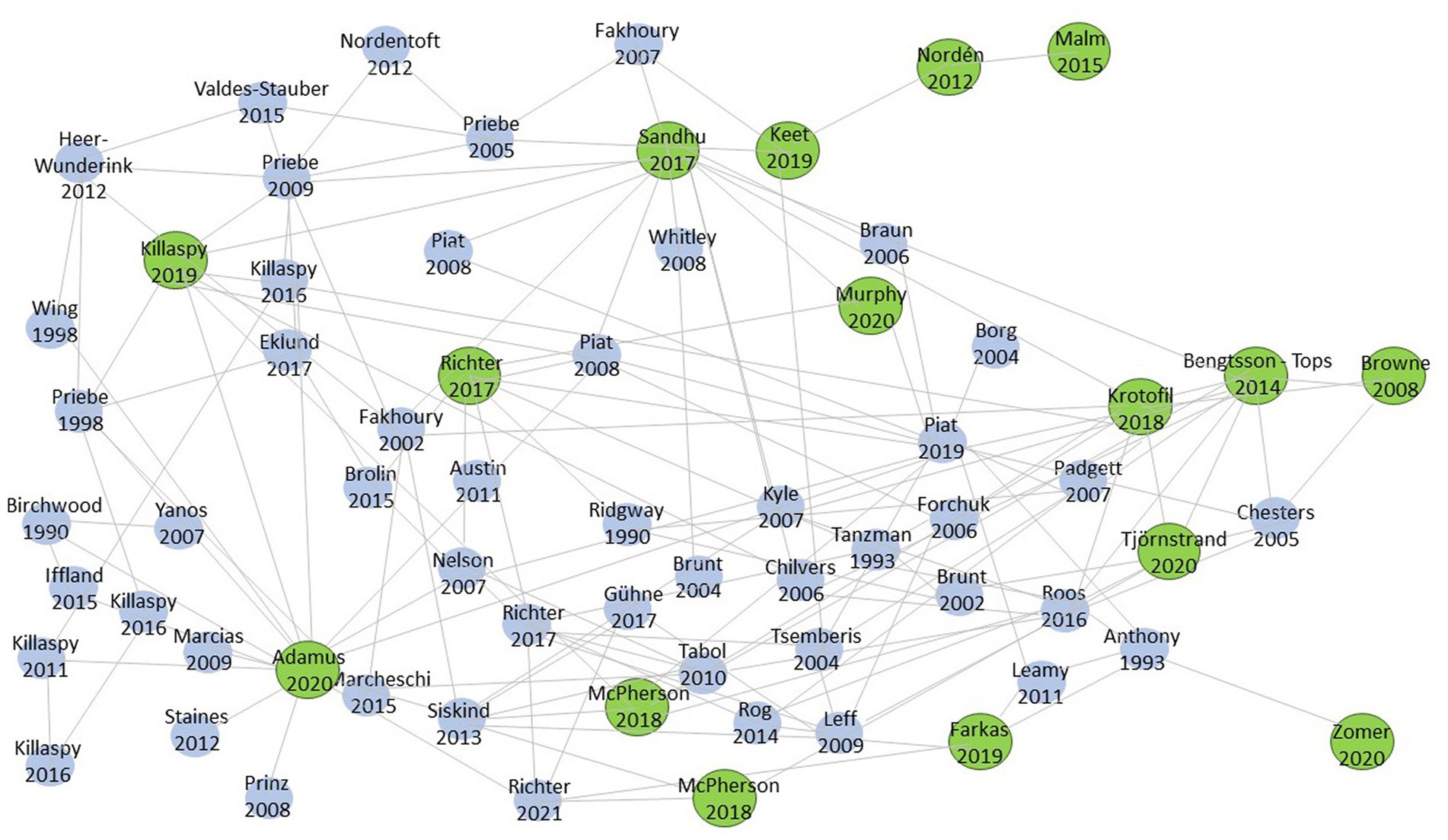

Methods: We conducted a scoping review by systematically searching four databases, supplemented with the results of Research Rabbit, a hand-search in reference lists and 10 volumes of two leading journals. We included studies on adults with SMI focusing on stimulating independent living, integrated care, recovery, and social inclusion published in English between January 2011 and December 2022 in peer-reviewed journals.

Results: The search resulted in 56 papers that met the inclusion criteria. Thematic analysis revealed ingredients in 12 areas: multidisciplinary teams; collaboration within and outside the organization; attention to several aspects of health; supporting full citizenship; attention to the recovery of daily life; collaboration with the social network; tailored support; well-trained staff; using digital technologies; housing and living environment; sustainable policies and funding; and reciprocity in relationships.

Conclusion: We found 12 areas of ingredients, including some innovative topics about reciprocity and sustainable policies and funding. There is much attention to individual ingredients for good community-based mental healthcare, but very little is known about their integration and implementation in contemporary, fragmented mental healthcare services. For future studies, we recommend more empirical research on community mental healthcare, as well as further investigation(s) from the social service perspective, and solid research on general terminology about SMI and outpatient support.

1. Introduction

For the last three decades, there has been a shift in mental healthcare from a biomedical model to a more biopsychosocial model with a focus on rehabilitation, strengths, all areas of recovery, citizenship, empowerment, autonomy, and shared decision-making as leading principles ( 1–5 ). Still, the “social aspect” of the biopsychosocial model has long remained neglected ( 6 ). In 2007, human rights for people with disabilities were covered in the convention ( 7 ), and several community-based mental healthcare programs and services have been developed in Europe for these groups, enhanced by peer-to-peer initiatives and recovery colleges ( 8 ). Over the past few years, concepts such as social inclusion, citizenship, and participation have become the heart of the deinstitutionalization movement. Additionally, more and more people with mental healthcare issues receive outreach support. An indication of the development of intensive outpatient care for people with severe mental illness (SMI) is the development of (flexible) assertive community treatment ((F)ACT) teams. For example, in Netherlands in 2020, there were an estimated 400 FACT teams ( 9 ) and about 30% of people with SMI in England receive support from a specialist mental health floating outreach service ( 10 ).

In general, the definition of SMI consists of three criteria: a psychiatric diagnosis according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, illness duration of more than 2 years, and disability in functioning ( 11 ). A subgroup of people with SMI needs intensive care and support in daily living and receives residential care, supported housing in a 24/7 facility, or floating outreach ( 12 ). Most people with SMI who live in residential supported housing facilities have a strong preference to live independently in the community with flexible support with a view to a meaningful and fulfilling life ( 13 ). Nowadays, there are several community-based support services for these people who want to live independently, such as Housing First (HF). HF is an evidence-based housing intervention in the social domain that combats homelessness ( 14 ). It combines rapid access to permanent, nonabstinence-contingent ordinary housing and recovery-oriented mental health support teams ( 15 ). Individuals with SMI are at a higher risk of homelessness, and a high proportion of individuals experiencing homelessness are also living with mental illness ( 16 ). Therefore, measures should be available to prevent those who do not make use of, or leave, supported housing from becoming homeless.

Different services for mental health conditions have traditionally been separate from other services such as physical healthcare and social services. However, there is increasing emphasis internationally on developing a whole-system approach to improve the integration of these services to maximize an individual’s quality of life and social inclusion by encouraging their skills, promoting independence and autonomy to give them hope for the future. That leads to successful community living through appropriate support, with particular focus on patient-centered development and delivery ( 17–19 ). Furthermore, following the rehabilitation and recovery movement, care should involve all areas of living ( 20 ), and community-based mental healthcare thus should be a more integrated package of services. Many studies have appeared on the development and impact of multidisciplinary teams in mental healthcare ( 21 , 22 ). A lot less research is available on supported housing services, including accommodation-based and floating outreach services, leading to a lack of evidence on what works in this area ( 23 , 24 ).

In this literature review, we focus on all services for persons with SMI which are living independently in the community. These services aim to support these people in their daily life. This includes services initiated by treatment organizations, such as ambulatory interdisciplinary teams, as well as by welfare and supported housing organizations. Following McPherson et al. ( 25 ), who developed the simple taxonomy for supported accommodation (STAX-SA) to capture the defining features of different supported accommodation models, in this study we focus on supported housing services meant for persons moving forward from a hospital admission or a full-time staffed housing accommodation in a congregate setting with high support, toward more individual accommodation with no staff on-site. These services can be low or might need to be medium or intensive to support independent living for all ( 25 ).

Currently, there is a lack of research about what is needed to successfully provide this type of intensive support for people with SMI, and especially about how this support can be organized as an integrated community-based mental healthcare approach, including housing, rehabilitation, citizenship, all areas of recovery, empowerment, autonomy, and decision-making power. We aim to provide a comprehensive overview of existing and upcoming community mental healthcare approaches to discover the current vision and empirical findings on the ingredients of community mental healthcare. To do so, we will look in this review for both empirical evidence, as well as leading concepts in this research topic. The findings of this study contribute to the further development of community-based mental healthcare for persons with SMI and high-volume healthcare needs. This paper will address the following question: What are the current insights (both leading concepts and empirical findings) regarding a community mental healthcare system to support all persons with SMI in their independent living and recovery, and stimulate further social inclusion?

This review follows the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews ( 26 ). The completed PRISMA checklist is available on request from the authors.

2.1. Study design

We performed a scoping review, following the steps of the framework of Arksey and O’Malley ( 27 ): (a) identify the research question; (b) identify relevant studies; (c) select the studies; (d) chart the data; and (e) collate, summarize and report the results. A scoping review contributes to mapping rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available ( 28 ).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

2.2.1. inclusion criteria.

We included papers published in English from January 2011 to December 2022 in peer-reviewed journals, aimed at 18 years and older adults with severe mental illness, focusing on stimulating independent living, integrated care, recovery, and social inclusion. For reasons of comparability, and fit in Western healthcare systems, studies were included if they were conducted in Western countries only (i.e., United States of America, Canada, countries in Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan). Finally, all study designs were included, and we also included papers about interventions related to collaboration.

2.2.2. Exclusion criteria