BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

The use of new technologies for improving reading comprehension.

- 1 Department of General Psychology, University of Padova, Padua, Italy

- 2 Azienda Sociosanitaria Ligure 5 Spezzino, La Spezia, Italy

Since the introduction of writing systems, reading comprehension has always been a foundation for achievement in several areas within the educational system, as well as a prerequisite for successful participation in most areas of adult life. The increased availability of technologies and web-based resources can be a really valid support, both in the educational and clinical field, to devise training activities that can also be carried out remotely. There are studies in current literature that has examined the efficacy of internet-based programs for reading comprehension for children with reading comprehension difficulties but almost none considered distance rehabilitation programs. The present paper reports data concerning a distance program Cloze , developed in Italy, for improving language and reading comprehension. Twenty-eight children from 3rd to 6th grade with comprehension difficulties were involved. These children completed the distance program for 15–20 min for at least three times a week for about 4 months. The program was presented separately to each child, with a degree of difficulty adapted to his/her characteristics. Text reading comprehension (assessed distinguishing between narrative and informative texts) increased after intervention. These findings have clinical and educational implications as they suggest that it is possible to promote reading comprehension with a distance individualized program, avoiding the need for the child displacements, necessary for reaching a rehabilitation center.

Introduction

Reading comprehension is a fundamental cognitive ability for children, that supports school achievement and successively participation in most areas of adult life ( Hulme and Snowling, 2011 ). Therefore, children with learning disabilities (LD) and special educational needs who show difficulties in text comprehension, sometimes also in association with other problems, may have an increased risk of life and school failure ( Woolley, 2011 ). Reading comprehension is, indeed, a complex cognitive ability which involves not only linguistic (e.g., vocabulary, grammatical knowledge), but also cognitive (such as working memory, De Beni and Palladino, 2000 ), and metacognitive skills (both for the aspects of knowledge and control, Channa et al., 2015 ), and, more specifically, higher order comprehension skills such as the generation of inferences ( Oakhill et al., 2003 ).

Recently, due to the diffusion of technology in many fields of daily life, text comprehension at school, at home during homework, and at work is based on an increasing number of digital reading devices (computers and laptops, e-books, and tablet devices) that can become a fundamental support to improve traditional reading comprehension and learning skills (e.g., inference generation).

Some authors contrasted in children with typical development the effects of the technological interface on reading comprehension vs printed texts ( Kerr and Symons, 2006 ; Rideout et al., 2010 ; Mangen et al., 2013 ; Singer and Alexander, 2017 ; Delgado et al., 2018 ). Results were consistent and showed a worse comprehension performance in screen texts compared to printed texts for children ( Mangen et al., 2013 ; Delgado et al., 2018 ) and adolescents who nonetheless showed a preference for digital texts compared to printed texts ( Singer and Alexander, 2017 ). Regarding children with learning problems, only few studies considered the differences between printed texts and digital devices ( Chen, 2009 ; Gonzalez, 2014 ; Krieger, 2017 ) finding no significant differences, suggesting that the use of compensative digital tools for children with a learning difficulty could be a valid alternative with respect to the traditional written texts in facilitating their academic and work performance. This conclusion is also supported by the results of a meta-analysis ( Moran et al., 2008 ), regarding the use of digital tools and learning environments for enhancing literacy acquisition in middle school students, which demonstrates that technology can improve reading comprehension.

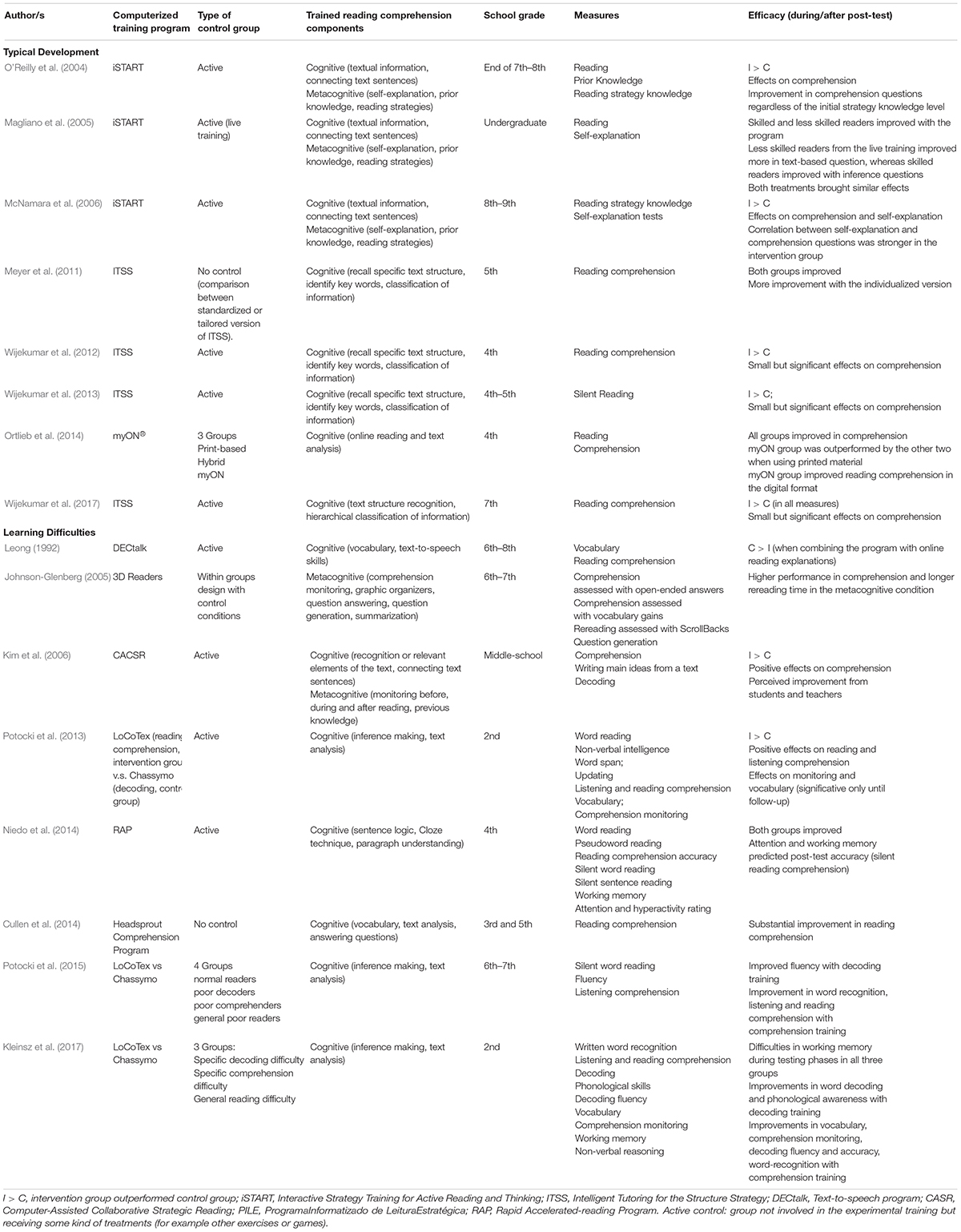

Different procedures and abilities are targeted in the international literature concerning computerized training programs for reading comprehension. In particular, various studies include activities promoting cognitive (e.g., vocabulary, inference making) and metacognitive (e.g., the use of strategies, comprehension monitoring, and identification of relevant parts in a text) components of reading comprehension. Table 1 reports the list of papers proposing computerized training programs with a summary of the findings encountered. Participants involved cover different ages and school grades, the majority belonging to middle school and high school. The general outcome of the studies is positive due to a significant improvement in comprehension skills after the training program with long-lasting effects also during follow-up; indeed, the majority of participants involved in training programs outperformed their peers assigned to comparison groups and maintained their improvements. Specifically, several studies ( O’Reilly et al., 2004 ; Magliano et al., 2005 ; McNamara et al., 2006 ) used the iSTART program with adolescents and young adults. This program promotes self-explanation, prior knowledge and reading strategies to enhance understanding of descriptive scientific texts. Results demonstrated that students who followed the iSTART program received more benefits than their peers, improving self-explanation and summarization. Additionally, strategic knowledge was a relevant factor for the outcome in comprehension tasks including multiple choice questions: students who already possessed good strategic knowledge improved their accuracy when answering to bridging inference questions, whereas students with low strategic knowledge became more accurate with text-based questions. Another program, ITSS, was used with younger students ( Meyer et al., 2011 ; Wijekumar et al., 2012 , 2013 , 2017 ), with the objective to support activities based on identifying main parts and key words in a text and classifying information in a hierarchical order. Positive outcomes were found also with such program since students who followed the ITSS program significantly improved text comprehension compared to their peers in the control group.

Table 1. Synthesis of the main results of the computerized training programs on comprehension present in the literature.

Although most of the literature deals with typical development, also cases of students with learning difficulties were considered. For example, Potocki et al. (2013) (see also Potocki et al., 2015 ) examined the effects of two different computerized programs with specific aims: one focusing on comprehension features, such as inference making and the analysis of text structure, the other considering decoding skills. Both training programs brought some benefits to reading comprehension, however larger effects were found with the program focused on comprehension with long-lasting effects in listening and reading comprehension (see also Kleinsz et al., 2017 ). Studies by Johnson-Glenberg (2005) and Kim et al. (2006) , using respectively the programs 3D Readers and CACSR, were able to promote reading comprehension abilities in middle school students through metacognitive activities. Thanks to these programs students also became more aware of reading strategies and implemented them more successfully during text comprehension. In particular, a study by Niedo et al. (2014) , obtained positive results on silent reading in a small group of children struggling with reading using the “cloze” procedure. This procedure proposes exercises in which parts of a text, typically words, are missing and participants are required to complete the text guessing what is missing.

Thus, computerized programs generally seem to improve reading comprehension skills. However, it should be noticed that, in most cases, students were trained at school, without the personalized support of a clinician taking into consideration the cognitive and psychological needs of the child. In particular, to our knowledge, no program examined the effects of an internet-based distance reading comprehension program which allows the child to be trained at home in a personalized way. A useful aspect of an internet-based distance training is that the psychologist can monitor with the application ( app ) the child’s results and activities and write him/her some motivational messages, reducing the attritions present in programs carried out at home with the only supervision of parents. Literature concerning distance trainings is still rare, however, some evidence suggests that these programs may represent a good integration to other types of intervention, usually carried out at school, in a rehabilitation center or at home (e.g., Mich et al., 2013 ).

Therefore, despite still preliminary, we think that it is relevant to present data about a distance program developed in Italy named Cloze ( Cornoldi and Bertolo, 2013 ), devised for rehabilitation purposes but with potential implication also for educational contexts. Cloze has been developed to promote inferential abilities both at a sentence- and discourse-level using the “cloze” procedure. Several findings in the literature demonstrate that abilities, such as anticipating text parts and inference making, bring improvements in text comprehension (e.g., Yuill and Oakhill, 1988 ) and it has been shown that one way to promote inferential competences is to improve the ability to predict parts of the text that are missing or that follow, considering the available information: the “cloze” technique appears to be one of the most successful ways for this purpose (e.g., Greene, 2001 ).

In the current study the effectiveness of this training program has been tested on a clinical population who exhibited, for various reasons, difficulties in reading comprehension. Participants were 28 children (16 male and 12 female) attending a private practice for learning difficulties in the city of La Spezia, in the north-west of Italy, from 3rd to 6th school grade (5 of 3rd, 9 of 4th, 11 of 5th and 3 of 6th grade), with a mean age of children of M = 9.79 years (SD = 1.03). Seventeen children had a current or past speech disorder: of these children 10 also had a LD (Learning Disabilities) and one was bilingual (speech problems were not due to bilingualism). The other 11 children had a LD or important learning difficulties, and one of them had also ADHD (Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder). For the goals of the study, all these children were considered together as they all presented a severe reading comprehension difficulty as reported by parents and teachers and confirmed by the initial assessment.

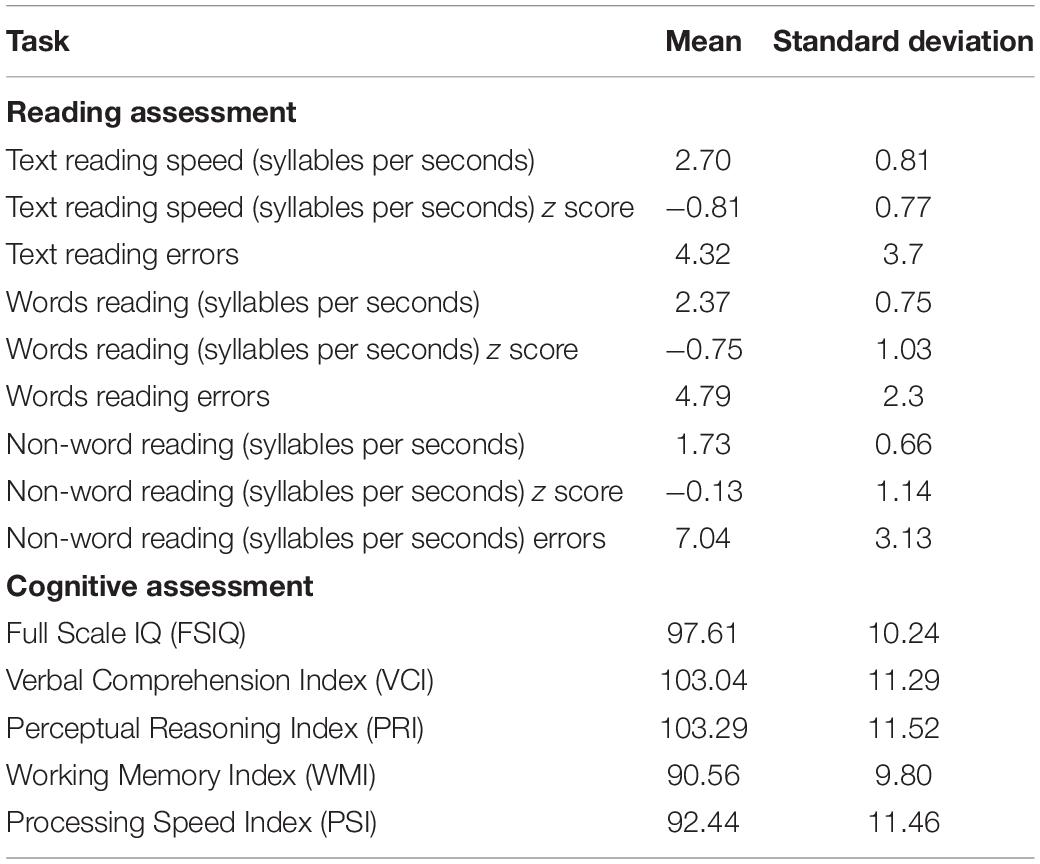

All children had received a comprehensive psychological assessment (see Table 2 ), adapted to their particular needs and ages. In particular all children had an IQ >80 assessed with the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV (WISC-IV; Wechsler, 2003 ) and did not have anxiety disorders, mood affective disorders or other developmental disorders, with the exception of the cases with language disorder and the case with ADHD. Children were not receiving any additional treatment, including medication. Written consent was obtained from the children’s parents in the context of the private practice.

Table 2. Main characteristics of the sample in terms of reading and cognitive abilities.

Materials and Methods

Pre-/post-test assessment and procedure of the training.

Each child started a training program through the distance rehabilitation platform Ridinet, using the Cloze app, after the assessment of learning and cognitive abilities, including comprehension assessment with two texts, one narrative and one informative ( Cornoldi and Carretti, 2016 ; Cornoldi et al., 2017 ). Connection to the Ridinet web site was required in order to access to the app, three or four times a week for more or less 15/20 min. The period of use was of 3 months for 6 children and 4 months for 22 children. After this period children’s comprehension was assessed again. Additionally, some questions were asked to parents and children about the app’s utility and pleasantness. In particular, children were asked: “Do you think the program helped you improve your text comprehension skills?,” “Did you like doing this program instead of the same exercises on paper?”; and parents were asked: “Was it difficult to start the Cloze activities on days when it had to be done?,” “Compared to the beginning of the treatment, how do you currently judge the ability of your child to understand the texts?”. For all questions, except the last one, the answer had to be given on a 5-point scale with 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = enough, 4 = very, 5 = very much. For the last question the answer changed on a 4-point scale with 1 = got worse, 2 = unchanged, 3 = slightly improved, and 4 = greatly improved.

Comprehension Tasks

Reading comprehension was assessed with two texts, the first narrative and the other informative, taken from Italian batteries for the assessment of reading ( Cornoldi and Carretti, 2016 ; Cornoldi et al., 2017 ). The texts range between 226 and 455 words in length, and their length increases with school grade (in order to have texts and questions matching the degrees of expertise at different grades the batteries include a different pair of texts for each grade). Students read the text in silence at their own pace, then answer a variable number of multiple-choice questions (depending on school grade), choosing one of four possible answers. There is no time limit, and students can reread the text whenever they wish. The final score is calculated as the total number of correct answers for each text. Alpha coefficients, as reported by the manuals, range between 0.61 and 0.83. For the purposes of the study we decided to use the same two comprehension texts, at pre-test and post-test, as the procedure offered the opportunity of directly examining and showing to parents changes in comprehension and previous evidence had shown the absence of relevant retest effects with this material in a retest carried out after 3 months ( Viola and Carretti, 2019 ).

Distance Rehabilitation Program: Cloze

Cloze ( Cornoldi and Bertolo, 2013 ) is an app for the promotion of text comprehension with the specific aim to recover processes of lexical and semantic inference. At each work session the child works with texts that lack words and must complete the empty spaces by choosing the correct alternative from those automatically proposed by the app, so that the text becomes congruent. The program is adaptive, as text complexity and proportion of missing words vary according to the previous level of response, and is designed for children who have weaknesses in written text comprehension, mainly due to poor skills in lexical and semantic inferential processes. The app also allows to enhance a set of language skills (phonology, syntax, semantics) which contribute to ensuring the fluidity of text and production processing. The recommended age range for the use of this program is between 7 and 14 years. In this study the semantic mode (only content words may be missing and no syntactic cues can be used for deciding between the alternatives) was proposed to 21 children and the syntactic mode (where all words may be missing) to 7 children. The mode type selected for each child depends from the performance at pre-test and diagnosis. A clinician, co-author of the present study (LB), monitored the child’s results and activities with the app and sent him/her from time to time some motivational messages. The motivational messages were typically sent once a week for congratulating with children for the work done and check with him/her possible problems emerged. Training lasted from 3 to 4 months and involved between 3 and 4 sessions of 15–20 min per week. The variation in duration depended on the decision of each individual family. In fact, children were required to use the software for about 4 months or in any case for a minimum period of 3 months (choice made by six families).

Effects on Reading Comprehension of Cloze Training

All analyses were carried out with SPSS 25 ( IBM Corp, 2017 ). A preliminary analysis found that all the examined variables met the assumptions of normality (K-S between 0.106 and 0.143, p > 0.05). Then, we compared the reading comprehension performance of children before and after the computerized training with Cloze . For this analysis, a repeated measure Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted on comprehension scores to examine the differences in the whole group of children between the scores obtained before and after the training. A significant difference was found for both comprehension texts [ F (1,27) = 22.37, p < 0.001, η 2 p = 0.453 and F (1,27) = 38.90, p < 0.001, η 2 p = 0.599, respectively]. Possible differences between the two training modalities (semantic vs syntactic) and between different training periods (3 months vs 4 months) were then analyzed; no significant differences emerged between groups in both cases [ F (1,27) < 1].

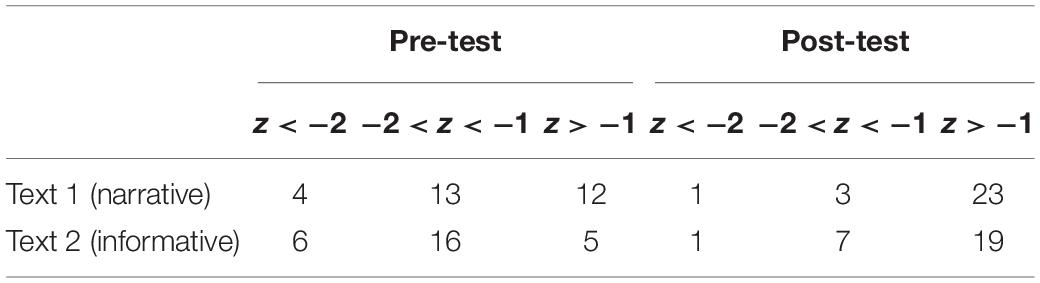

Secondly, to analyze the role of individual differences at pre-test, the standardized training gain score (STG; Jaeggi et al., 2011 ) – computed by subtracting post-test score minus pre-test score, divided by the SD of the pre-test – was calculated for the two texts comprehension. Pearson correlations were computed between the STG and the variable collected at pre-test (reading speed and errors, WISC IV – Full scale IQ, Verbal Comprehension, Perceptual Reasoning, Working Memory and Processing Speed indexes). The only significant correlation was between STG of the narrative text and Verbal Comprehension Index of the WISC-IV Scale ( r = 0.38, p = 0.048). Finally, individual improvements from pre- to post-test were also confirmed considering changes in performance in terms of standard deviation in relations to norms (provided by the manual). Table 3 shows the number of children for each comprehension text who improved their performance moving from a performance at least 2 standard deviations or between 1 and 2 negative standard deviations under the mean to a performance above one negative standard deviation.

Table 3. Changes in performance in relations to norms (provided by the manual) after the training program Cloze.

Perceived Utility, Pleasantness, Parents and Child’s Improvements of Cloze

Results concerning the answers of parents and children about utility, pleasantness and self-perceived efficacy of the app, were also analyzed. At the first question, addressing children’s perceived improvement in comprehension skills, more than half of the sample chose the alternatives “very” or “very much” (15 “very” and 5 “very much”), only 1 child answered “a little” and the others chose “enough.” At the second question, about the pleasure of doing this kind of activity instead of pen and paper activities, all children answered “very” or “very much.” Concerning parents’ questions, at the first question about the difficulty to start the Cloze activity, only one parent answered “enough,” a quarter of the sample chose “a little” (seven families) and all the other 20 families chose the alternative “not at all.” At the last question about the perceived training efficacy on their child’s performance, the large majority of the families chose “slightly improved” or “greatly improved” and only three parents thought their children’s ability had remained unchanged. However, no correlations between parents and child’s perceived improvements and STG in reading comprehension were found.

The present study examined the effects of the use of Cloze , a distance rehabilitation program focused on inference skills, for improving reading comprehension, on the basis of the hypothesis that, being inference making related to reading comprehension at different ages (e.g., Oakhill and Cain, 2012 ), positive effects of the training activities on reading comprehension should be found.

Concerning the efficacy of computer-assisted training programs, literature highlights that many training programs are devised for an educational context. Results are generally encouraging with positive effects on reading comprehension, measured with materials different from those practiced during the training. However, few studies analyzed the efficacy in children with specific reading comprehension problems, and no studies considered the possibility of carrying out a training at home under the distance supervision of an expert. The latter characteristics are those that make the Cloze peculiar compared to the existent literature. Cloze is indeed based on a rehabilitation online platform which allows the child to complete personalized training activities several times a week, without moving from his/her home, and concurrently enabling the clinician to monitor the child’s progress or manage activities’ characteristics. The advantage of this procedure is twofold: on one hand it increases the potential number of training sessions per week, on the other hand it permits to save the necessary time to reach the center for rehabilitation and to reduce the costs of the intervention.

The preliminary data on Cloze were generally positive: children, working on either two slightly different versions of the same program, showed a generalized improvement in reading comprehension tasks and, together with their families, expressed appreciation for the pleasantness and the efficacy of the program. Encouraging results emerged also from the analysis of individual improvements referring to normative scores, as reported in Table 3 : most of the children’s performance migrated from a highly negative level to an average level.

It is noticeable that the efficacy of the training was assessed with materials different from those practiced during the training sessions, since reading comprehension tasks required to read a paper text and complete a series of multiple-choice questions. In future studies it would be interesting to analyze the effects of the program on skills known to be related to text comprehension, such as vocabulary or comprehension monitoring, for example. There is good reason to believe that since these variables are highly predictive of comprehension skills (and given that training in these skills sometimes improve comprehension; e.g., Beck et al., 1982 ; see also Hulme and Snowling, 2011 ), training that specifically targets comprehension might, in turn, lead to improvements in vocabulary or comprehension monitoring skills. Further studies are needed to explore this hypothesis.

A second relevant finding of the present study is the presence of a positive correlation between the gain obtained in one of the reading comprehension text (the narrative one) and the Verbal Comprehension Intelligence Quotient (VCIQ) index of the WISC-IV battery, showing that children who started with more resources in verbal intelligence achieved greater improvements in text comprehension at least with one type of text through the Cloze . The activities probably required to develop some kind of strategies, and for this reason students with larger verbal intellectual resources, who were presumably more able to develop new strategies, were more advantaged. Indeed, this amplification effect is usually found when training activities require the development of strategies ( von Bastian and Oberauer, 2014 ). Such result has clinical and educational implications, inviting professionals and teachers to consider children’s starting resources and, if necessary, to combine activities conducted through distance rehabilitation programs with personal intervention sessions that could teach strategies and promote a metacognitive approach to reading comprehension. However, some limitations of the present study must be acknowledged. Firstly, study did not include a control group, therefore findings should be taken with caution, although normative data and previous results obtained with the same test offer support to the robustness of our results and the use of normative data offers a control measure of how reading comprehension skills are acquired in typically developing children without specific training, therefore functioning as a sort of passive control group. Secondly, the treated group, although characterized by a common reading comprehension difficulty, was partly heterogeneous, as children attended different grades and could have different diagnoses. Unfortunately, the limited number of subjects, with the consequence that it was not possible to form groups defined both by the grade and the diagnosis, did not permit to make analyses taking into account the grade and the diagnosis as between-subjects factors. Future studies should examine a more homogeneous population or consider a larger sample of children, giving more information about the efficacy of training in different children population. Additionally, the fact that the treatment was concluded with the post-training assessment did not offer the opportunity to further examine the procedure and maintenance effects with a follow-up. Despite the limitations, this study offers evidence concerning the efficacy of new methods, based on computer-assisted training programs that could be beneficial in training high-level skills such as comprehension and inference generation. Such tools can be extremely worthwhile for struggling readers who may need to receive further attention in mastering higher level reading comprehension.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

AC, CC and BC contributed to the design and implementation of the research. LB provided the data. BC organized the database. AC performed the statistical analysis. ED did the literature research and wrote the section about the review of the literature. AC and BC wrote the other sections. CC contributed to the manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

The present work was carried out within the scope of the research program Dipartimenti di Eccellenza (art.1, commi 314-337 legge 232/2016), which was supported by a grant from MIUR to the Department of General Psychology, University of Padua and partially supported by a grant (PRIN 2015, 2015AR52F9_003) to Cesare Cornoldi funded by the Italian Ministry of Research and Education (MIUR).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Beck, I. L., Perfetti, C. A., and McKeown, M. G. (1982). Effects of long-term vocabulary instruction on lexical access and reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 74, 506–521. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.74.4.506

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Channa, M. A., Nordin, Z. S., Siming, I. A., Chandio, A. A., and Koondher, M. A. (2015). Developing reading comprehension through metacognitive strategies: a review of previous studies. Eng. Lang. Teach. 8, 181–186. doi: 10.5539/elt.v8n8p181

Chen, H. (2009). Online reading comprehension strategies among fifth- and sixth-grade general and special education students. Educ. Res. Perspect. 37, 79–109.

Google Scholar

Cornoldi, C., and Bertolo, L. (2013). Cloze Ridinet. Bologna: Anastasis.

Cornoldi, C., and Carretti, B. (2016). Prove MT-3-Clinica. Firenze: Giunti Edu.

Cornoldi, C., Carretti, B., and Colpo, C. (2017). Prove MT-Kit Scuola. Dalla valutazione degli Apprendimenti di Lettura E Comprensione Al Potenziamento. [MT-Kit for the Assessment In The School. From Reading Assessment To Its Enhancement]. Firenze: Giunti Edu.

Cullen, J. M., Alber-Morgan, S. R., Schnell, S. T., and Wheaton, J. E. (2014). Improving reading skills of students with disabilities using headsprout comprehension. Remed. Spec. Educ. 35, 356–365. doi: 10.1177/0741932514534075

De Beni, R., and Palladino, P. (2000). Intrusion errors in working memory tasks: are they related to reading comprehension ability? Learn. Individ. Differ. 12, 131–143. doi: 10.1016/s1041-6080(01)00033-4

Delgado, P., Vargas, C., Ackerman, R., and Salmerón, L. (2018). Don’t throw away your printed books: a meta-analysis on the effects of reading media on reading comprehension. Educ. Res. Rev. 25, 23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2018.09.003

Gonzalez, M. (2014). The effect of embedded text-to-speech and vocabulary eBook scaffolds on the comprehension of students with reading disabilities. Intern. J. Spec. Educ. 29, 111–125.

Greene, B. (2001). Testing reading comprehension of theoretical discourse with cloze. J. Res. Read. 24, 82–98. doi: 10.1111/1467-9817.00134

Hulme, C., and Snowling, M. J. (2011). Children’s reading comprehension difficulties: nature, causes, and treatments. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 20, 139–142. doi: 10.1177/0963721411408673

IBM Corp (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Jonides, J., and Shah, P. (2011). Short-and long-term benefits of cognitive training. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 10081–10086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103228108

Johnson-Glenberg, M. C. (2005). Web-based training of metacognitive strategies for text comprehension: focus on poor comprehenders. Read. Writ. 18, 755–786. doi: 10.1007/s11145-005-0956-5

Kerr, M. A., and Symons, S. E. (2006). Computerized presentation of text: effects on children’s reading of informational material. Read. Writ. 19, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11145-003-8128-y

Kim, A. H., Vaughn, S., Klingner, J. K., Woodruff, A. L., Klein Reutebuch, C., and Kouzekanani, K. (2006). Improving the reading comprehension of middle school students with disabilities through computer-assisted collaborative strategic reading. Remed. Spec. Educ. 27, 235–249. doi: 10.1177/07419325060270040401

Kleinsz, N., Potocki, A., Ecalle, J., and Magnan, A. (2017). Profiles of French poor readers: underlying difficulties and effects of computerized training programs. Learn. Individ. Differ. 57, 45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2017.05.009

Krieger, R. (2017). The Effect of Electronic Text Reading on Reading Comprehension Scores of Students with Disabilities. Master thesis, Governors State University, Park, IL.

Leong, C. K. (1992). Enhancing reading comprehension with text-to-speech (DECtalk) computer system. Read. Writ. 4, 205–217. doi: 10.1007/bf01027492

Magliano, J. P., Todaro, S., Millis, K., Wiemer-Hastings, K., Kim, H. J., and McNamara, D. S. (2005). Changes in reading strategies as a function of reading training: a comparison of live and computerized training. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 32, 185–208. doi: 10.2190/1ln8-7bqe-8tn0-m91l

Mangen, A., Walgermo, B. R., and Brønnick, K. (2013). Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: effects on reading comprehension. Intern. J. Educ. Res. 58, 61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2012.12.002

McNamara, D. S., O’Reilly, T. P., Best, R. M., and Ozuru, Y. (2006). Improving adolescent students’ reading comprehension with iSTART. Intern. J. Educ. Res. 34, 147–171. doi: 10.2190/1ru5-hdtj-a5c8-jvwe

Meyer, B. J., Wijekumar, K. K., and Lin, Y. C. (2011). Individualizing a web-based structure strategy intervention for fifth graders’ comprehension of nonfiction. J. Educ. Psychol. 103, 140–168. doi: 10.1037/a0021606

Mich, O., Pianta, E., and Mana, N. (2013). Interactive stories and exercises with dynamic feedback for improving reading comprehension skills in deaf children. Comput. Educ. 65, 34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.01.016

Moran, J., Ferdig, R. E., Pearson, P. D., Wardrop, J., and Blomeyer, R. L. Jr. (2008). Technology and reading performance in the middle-school grades: a meta-analysis with recommendations for policy and practice. J. Liter. Res. 40, 6–58. doi: 10.1080/10862960802070483

Niedo, J., Lee, Y. L., Breznitz, Z., and Berninger, V. W. (2014). Computerized silent reading rate and strategy instruction for fourth graders at risk in silent reading rate. Learn. Disabil. Q. 37, 100–110. doi: 10.1177/0731948713507263

Oakhill, J. V., and Cain, K. (2012). The precursors of reading ability in young readers: evidence from a four-year longitudinal study. Sci. Stud. Read. 162, 91–121. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2010.529219

Oakhill, J. V., Cain, K., and Bryant, P. E. (2003). The dissociation of word reading and text comprehension: evidence from component skills. Lang. Cogn. Process. 18, 443–468. doi: 10.1080/01690960344000008

O’Reilly, T. P., Sinclair, G. P., and McNamara, D. S. (2004). “iSTART: A web-based reading strategy intervention that improves students’ science comprehension,” in Proceedings of the IADIS International Conference Cognition and Exploratory Learning in Digital Age: CELDA 2004 , eds D. G. Kinshuk and P. Isaias (Lisbon: IADIS), 173–180.

Ortlieb, E., Sargent, S., and Moreland, M. (2014). Evaluating the efficacy of using a digital reading environment to improve reading comprehension within a reading clinic. Read. Psychol. 35, 397–421. doi: 10.1080/02702711.2012.683236

Potocki, A., Ecalle, J., and Magnan, A. (2013). Effects of computer-assisted comprehension training in less skilled comprehenders in second grade: a one-year follow-up study. Comput. Educ. 63, 131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.12.011

Potocki, A., Magnan, A., and Ecalle, J. (2015). Computerized trainings in four groups of struggling readers: specific effects on word reading and comprehension. Res. Dev. Disabil. 45, 83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.07.016

Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., and Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M 2: Media in the Lives of 8-to 18-Year-Olds. San Francisco, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Singer, L. M., and Alexander, P. A. (2017). Reading on paper and digitally: what the past decades of empirical research reveal. Rev. Educ. Res. 87, 1007–1041. doi: 10.3102/0034654317722961

Viola, F., and Carretti, B. (2019). Cambiamentinelleabilità di letturanelcorso di unostesso anno scolastico [Changes in readingskillsduring the sameschoolyear]. Dislessia 16, 147–159. doi: 10.14605/DIS1621902

von Bastian, C. C., and Oberauer, K. (2014). Effects and mechanisms of working memory training: a review. Psychol. Res. 78, 803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00426-013-0524-526

Wechsler, D. (2003). Wechsler Intelligence Scale For Children–Fourth Edition (WISC-IV). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Wijekumar, K. K., Meyer, B. J., and Lei, P. (2012). Large-scale randomized controlled trial with 4th graders using intelligent tutoring of the structure strategy to improve nonfiction reading comprehension. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 60, 987–1013. doi: 10.1007/s11423-012-9263-4

Wijekumar, K. K., Meyer, B. J., and Lei, P. (2013). High-fidelity implementation of web-based intelligent tutoring system improves fourth and fifth graders content area reading comprehension. Comput. Educ. 68, 366–379. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.05.021

Wijekumar, K. K., Meyer, B. J., and Lei, P. (2017). Web-based text structure strategy instruction improves seventh graders’ content area reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 109, 741–760. doi: 10.1037/edu0000168

Woolley, G. (2011). “Reading comprehension,” in Reading Comprehension: Assisting Children With Learning Difficulties , ed Springer Science+Business Media (Dordrecht, NL: Springer), doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-1174-7_2

Yuill, N., and Oakhill, J. (1988). Effects of inference awareness training on poor reading comprehension. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2, 33–45. doi: 10.1002/acp.2350020105

Keywords : reading comprehension, training, distance rehabilitation program, digital device, Cloze app

Citation: Capodieci A, Cornoldi C, Doerr E, Bertolo L and Carretti B (2020) The Use of New Technologies for Improving Reading Comprehension. Front. Psychol. 11:751. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00751

Received: 20 November 2019; Accepted: 27 March 2020; Published: 23 April 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Capodieci, Cornoldi, Doerr, Bertolo and Carretti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Agnese Capodieci, [email protected] ; Laura Bertolo, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children (1998)

Chapter: part i: introduction to reading, part i introduction to reading.

Reading is a complex developmental challenge that we know to be intertwined with many other developmental accomplishments: attention, memory, language, and motivation, for example. Reading is not only a cognitive psycholinguistic activity but also a social activity.

Being a good reader in English means that a child has gained a functional knowledge of the principles of the English alphabetic writing system. Young children gain functional knowledge of the parts, products, and uses of the writing system from their ability to attend to and analyze the external sound structure of spoken words. Understanding the basic alphabetic principle requires an awareness that spoken language can be analyzed into strings of separable words, and words, in turn, into sequences of syllables and phonemes within syllables.

Beyond knowledge about how the English writing system works, though, there is a point in a child's growth when we expect "real reading" to start. Children are expected, without help, to read some unfamiliar texts, relying on the print and drawing meaning from it. There are many reasons why children have difficulty learning to read. These issues and problems led to the initiation of this study.

Even though quite accurate estimates can be made on the basis of known risk factors, it is still difficult to predict precisely which young children will have difficulty learning to read. We therefore propose that prevention efforts must reach all children. To wait to initiate treatment until the child has been diagnosed with a specific disability is too late. However, we can begin treatment of conditions associated with reading problems, for example, hearing impairments.

Ensuring success in reading requires different levels of effort for different segments of the population. The prevention and intervention efforts described in this report can be thought of in terms of three levels (Caplan and Grunebaum, 1967, cited in Simeonsson, 1994; Pianta, 1990; and Needlman, 1997). Primary prevention is concerned with reducing the number of new cases (incidence) of an identified condition or problem in the population, such as ensuring that all children attend schools in which instruction is coherent and competent.

Secondary prevention is concerned with reducing the number of existing cases (prevalence) of an identified condition or problem in the population. Secondary prevention likewise involves the promotion of compensatory skills and behaviors. Children who are growing up in poverty, for example, may need excellent, enriched preschool environments or schools that address their particular learning needs with highly effective and focused instruction. The extra effort is focused on children at higher risk of developing reading difficulties but before any serious, long-term deficit has emerged.

Tertiary prevention is concerned with reducing the complications associated with identified problem, or conditions. Programs, strategies, and interventions at this level have an explicit remedial or rehabilitative focus. If children demonstrate inadequate progress under secondary prevention conditions, they may need instruction that is specially designed and supplemental—special education, tutoring from a reading specialist—to their current instruction.

While most children learn to read fairly well, there remain many young Americans whose futures are imperiled because they do not read well enough to meet the demands of our competitive, technology-driven society. This book explores the problem within the context of social, historical, cultural, and biological factors.

Recommendations address the identification of groups of children at risk, effective instruction for the preschool and early grades, effective approaches to dialects and bilingualism, the importance of these findings for the professional development of teachers, and gaps that remain in our understanding of how children learn to read. Implications for parents, teachers, schools, communities, the media, and government at all levels are discussed.

The book examines the epidemiology of reading problems and introduces the concepts used by experts in the field. In a clear and readable narrative, word identification, comprehension, and other processes in normal reading development are discussed.

Against the background of normal progress, Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children examines factors that put children at risk of poor reading. It explores in detail how literacy can be fostered from birth through kindergarten and the primary grades, including evaluation of philosophies, systems, and materials commonly used to teach reading.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Levels of Reading Comprehension in Higher Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Cristina de-la-peña.

1 Departamento de Métodos de Investigación y Diagnóstico en Educación, Universidad Internacional de la Rioja, Logroño, Spain

María Jesús Luque-Rojas

2 Department of Theory and History of Education and Research Methods and Diagnosis in Education, University of Malaga, Málaga, Spain

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Higher education aims for university students to produce knowledge from the critical reflection of scientific texts. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a deep mental representation of written information. The objective of this research was to determine through a systematic review and meta-analysis the proportion of university students who have an optimal performance at each level of reading comprehension. Systematic review of empirical studies has been limited from 2010 to March 2021 using the Web of Science, Scopus, Medline, and PsycINFO databases. Two reviewers performed data extraction independently. A random-effects model of proportions was used for the meta-analysis and heterogeneity was assessed with I 2 . To analyze the influence of moderating variables, meta-regression was used and two ways were used to study publication bias. Seven articles were identified with a total sample of the seven of 1,044. The proportion of students at the literal level was 56% (95% CI = 39–72%, I 2 = 96.3%), inferential level 33% (95% CI = 19–46%, I 2 = 95.2%), critical level 22% (95% CI = 9–35%, I 2 = 99.04%), and organizational level 22% (95% CI = 6–37%, I 2 = 99.67%). Comparing reading comprehension levels, there is a significant higher proportion of university students who have an optimal level of literal compared to the rest of the reading comprehension levels. The results have to be interpreted with caution but are a guide for future research.

Introduction

Reading comprehension allows the integration of knowledge that facilitates training processes and successful coping with academic and personal situations. In higher education, this reading comprehension has to provide students with autonomy to self-direct their academic-professional learning and provide critical thinking in favor of community service ( UNESCO, 2009 ). However, research in recent years ( Bharuthram, 2012 ; Afflerbach et al., 2015 ) indicates that a part of university students are not prepared to successfully deal with academic texts or they have reading difficulties ( Smagorinsky, 2001 ; Cox et al., 2014 ), which may limit academic training focused on written texts. This work aims to review the level of reading comprehension provided by studies carried out in different countries, considering the heterogeneity of existing educational models.

The level of reading comprehension refers to the type of mental representation that is made of the written text. The reader builds a mental model in which he can integrate explicit and implicit data from the text, experiences, and previous knowledge ( Kucer, 2016 ; van den Broek et al., 2016 ). Within the framework of the construction-integration model ( Kintsch and van Dijk, 1978 ; Kintsch, 1998 ), the most accepted model of reading comprehension, processing levels are differentiated, specifically: A superficial level that identifies or memorizes data forming the basis of the text and a deep level in which the text situation model is elaborated integrating previous experiences and knowledge. At these levels of processing, the cognitive strategies used, are different according to the domain-learning model ( Alexander, 2004 ) from basic coding to a transformation of the text. In the scientific literature, there are investigations ( Yussof et al., 2013 ; Ulum, 2016 ) that also identify levels of reading comprehension ranging from a literal level of identification of ideas to an inferential and critical level that require the elaboration of inferences and the data transformation.

Studies focused on higher education ( Barletta et al., 2005 ; Yáñez Botello, 2013 ) show that university students are at a literal or basic level of understanding, they often have difficulties in making inferences and recognizing the macrostructure of the written text, so they would not develop a model of a situation of the text. These scientific results are in the same direction as the research on reading comprehension in the mother tongue in the university population. Bharuthram (2012) indicates that university students do not access or develop effective strategies for reading comprehension, such as the capacity for abstraction and synthesis-analysis. Later, Livingston et al. (2015) find that first-year education students present limited reading strategies and difficulties in understanding written texts. Ntereke and Ramoroka (2017) found that only 12.4% of students perform well in a reading comprehension task, 34.3% presenting a low level of execution in the task.

Factors related to the level of understanding of written information are the mode of presentation of the text (printed vs. digital), the type of metacognitive strategies used (planning, making inferences, inhibition, monitoring, etc.), the type of text and difficulties (novel vs. a science passage), the mode of writing (text vs. multimodal), the type of reading comprehension task, and the diversity of the student. For example, several studies ( Tuncer and Bahadir, 2014 ; Trakhman et al., 2019 ; Kazazoglu, 2020 ) indicate that reading is more efficient with better performance in reading comprehension tests in printed texts compared to the same text in digital and according to Spencer (2006) college students prefer to read in print vs. digital texts. In reading the written text, metacognitive strategies are involved ( Amril et al., 2019 ) but studies ( Channa et al., 2018 ) seem to indicate that students do not use them for reading comprehension, specifically; Korotaeva (2012) finds that only 7% of students use them. Concerning the type of text and difficulties, for Wolfe and Woodwyk (2010) , expository texts benefit more from the construction of a situational model of the text than narrative texts, although Feng (2011) finds that expository texts are more difficult to read than narrative texts. Regarding the modality of the text, Mayer (2009) and Guo et al. (2020) indicate that multimodal texts that incorporate images into the text positively improve reading comprehension. In a study of Kobayashi (2002) using open questions, close, and multiple-choice shows that the type and format of the reading comprehension assessment test significantly influence student performance and that more structured tests help to better differentiate the good ones and the poor ones in reading comprehension. Finally, about student diversity, studies link reading comprehension with the interest and intrinsic motivation of university students ( Cartwright et al., 2019 ; Dewi et al., 2020 ), with gender ( Saracaloglu and Karasakaloglu, 2011 ), finding that women present a better level of reading comprehension than men and with knowledge related to reading ( Perfetti et al., 1987 ). In this research, it was controlled that all were printed and unimodal texts, that is, only text. This is essential because the cognitive processes involved in reading comprehension can vary with these factors ( Butcher and Kintsch, 2003 ; Xu et al., 2020 ).

The Present Study

Regardless of the educational context, in any university discipline, preparing essays or developing arguments are formative tasks that require a deep level of reading comprehension (inferences and transformation of information) that allows the elaboration of a situation model, and not having this level can lead to limited formative learning. Therefore, the objective of this research was to know the state of reading comprehension levels in higher education; specifically, the proportion of university students who perform optimally at each level of reading comprehension. It is important to note that there is not much information about the different levels in university students and that it is the only meta-analytic review that explores different levels of reading comprehension in this educational stage. This is a relevant issue because the university system requires that students produce knowledge from the critical reflection of scientific texts, preparing them for innovation, employability, and coexistence in society.

Materials and Methods

Eligibility criteria: inclusion and exclusion.

Empirical studies written in Spanish or English are selected that analyze the reading comprehension level in university students.

The exclusion criteria are as follows: (a) book chapters or review books or publications; (b) articles in other languages; (c) studies of lower educational levels; (d) articles that do not identify the age of the sample; (e) second language studies; (f) students with learning difficulties or other disorders; (g) publications that do not indicate the level of reading comprehension; (h) studies that relate reading competence with other variables but do not report reading comprehension levels; (i) pre-post program application work; (j) studies with experimental and control groups; (k) articles comparing pre-university stages or adults; (l) publications that use multi-texts; (m) studies that use some type of technology (computer, hypertext, web, psychophysiological, online questionnaire, etc.); and (n) studies unrelated to the subject of interest.

Only those publications that meet the following criteria are included as: (a) be empirical research (article, thesis, final degree/master’s degree, or conference proceedings book); (b) university stage; (c) include data or some measure on the level of reading comprehension that allows calculating the effect size; (d) written in English or Spanish; (e) reading comprehension in the first language or mother tongue; and (f) the temporary period from January 2010 to March 2021.

Search Strategies

A three-step procedure is used to select the studies included in the meta-analysis. In the first step, a review of research and empirical articles in English and Spanish from January 2010 to March 2021. The search is carried out in online databases of languages in Spanish and English, such as Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, Medline, and PsycINFO, to review empirical productions that analyze the level of reading comprehension in university students. In the second step, the following terms (titles, abstracts, keywords, and full text) are used to select the articles: Reading comprehension and higher education, university students, in Spanish and English, combined with the Boolean operators AND and OR. In the last step, secondary sources, such as the Google search engine, Theseus, and references in publications, are explored.

The search reports 4,294 publications (articles, theses, and conference proceedings books) in the databases and eight records of secondary references, specifically, 1989 from WoS, 2001 from Scopus, 42 from Medline, and 262 of PsycINFO. Of the total (4,294), 1,568 are eliminated due to duplications, leaving 2,734 valid records. Next, titles and abstracts are reviewed and 2,659 are excluded because they do not meet the inclusion criteria. The sample of 75 publications is reduced to 40 articles, excluding 35 because the full text cannot be accessed (the authors were contacted but did not respond), the full text did not show specific statistical data, they used online questionnaires or computerized presentations of the text. Finally, seven articles in Spanish were selected for use in the meta-analysis of the reading comprehension level of university students. Data additional to those included in the articles were not requested from the selected authors.

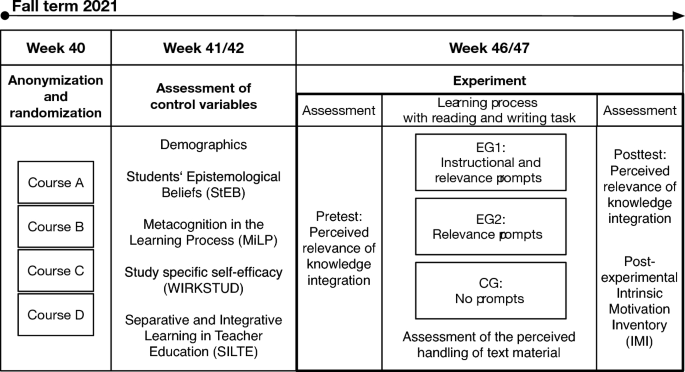

The PRISMA-P guidelines ( Moher et al., 2015 ) are followed to perform the meta-analysis and the flow chart for the selection of publications relevant to the subject is exposed (Figure 1) .

Flow diagram for the selection of articles.

Encoding Procedure

This research complies with what is established in the manual of systematic reviews ( Higgins and Green, 2008 ) in which clear objectives, specific search terms, and eligibility criteria for previously defined works are established. Two independent coders, reaching a 100% agreement, carry out the study search process. Subsequently, the research is codified, for this, a coding protocol is used as a guide to help resolve the ambiguities between the coders; the proposals are reflected and discussed and discrepancies are resolved, reaching a degree of agreement between the two coders of 97%.

For all studies, the reference, country, research objective, sample size, age and gender, reading comprehension test, other tests, and reading comprehension results were coded in percentages. All this information was later systematized in Table 1 .

Results of the empirical studies included in the meta-analysis.

In relation to the type of reading comprehension level, it was coded based on the levels of the scientific literature as follows: 1 = literal; 2 = inferential; 3 = critical; and 4 = organizational.

Regarding the possible moderating variables, it was coded if the investigations used a standardized reading comprehension measure (value = 1) or non-standardized (value = 0). This research considers the standardized measures of reading comprehension as the non-standardized measures created by the researchers themselves in their studies or questionnaires by other authors. By the type of evaluation test, we encode between multiple-choice (value = 0) or multiple-choices plus open question (value = 1). By type of text, we encode between argumentative (value = 1) or unknown (value = 0). By the type of career, we encode social sciences (value = 1) or other careers (health sciences; value = 0). Moreover, by the type of publication, we encode between article (value = 1) or doctoral thesis (value = 0).

Effect Size and Statistical Analysis

This descriptive study with a sample k = 7 and a population of 1,044 university students used a continuous variable and the proportions were used as the effect size to analyze the proportion of students who had an optimal performance at each level of reading comprehension. As for the percentages of each level of reading comprehension of the sample, they were transformed into absolute frequencies. A random-effects model ( Borenstein et al., 2009 ) was used as the effect size. These random-effects models have a greater capacity to generalize the conclusions and allow estimating the effects of different sources of variation (moderating variables). The DerSimonian and Laird method ( Egger et al., 2001 ) was used, calculating raw proportion and for each proportion its standard error, value of p and 95% confidence interval (CI).

To examine sampling variability, Cochran’s Q test (to test the null hypothesis of homogeneity between studies) and I 2 (proportion of variability) were used. According to Higgins et al. (2003) , if I 2 reaches 25%, it is considered low, if it reaches 50% and if it exceeds 75% it is considered high. A meta-regression analysis was used to investigate the effect of the moderator variables (type of measure, type of evaluation test, type of text, type of career, and type of publication) in each level of reading comprehension of the sample studies. For each moderating variable, all the necessary statistics were calculated (estimate, standard error, CI, Q , and I 2 ).

To compare the effect sizes of each level (literal, inferential, critical, and organizational) of reading comprehension, the chi-square test for the proportion recommended by Campbell (2007) was used.

Finally, to analyze publication bias, this study uses two ways: Rosenthal’s fail-safe number and regression test. Rosenthal’s fail-safe number shows the number of missing studies with null effects that would make the previous correlations insignificant ( Borenstein et al., 2009 ). When the values are large there is no bias. In the regression test, when the regression is not significant, there is no bias.

The software used to classify and encode data and produce descriptive statistics was with Microsoft Excel and the Jamovi version 1.6 free software was used to perform the meta-analysis.

The results of the meta-analysis are presented in three parts: the general descriptive analysis of the included studies; the meta-analytic analysis with the effect size, heterogeneity, moderating variables, and comparison of effect sizes; and the study of publication bias.

Overview of Included Studies

The search carried out of the scientific literature related to the subject published from 2010 to March 2021 generated a small number of publications, because it was limited to the higher education stage and required clear statistical data on reading comprehension.

Table 1 presents all the publications reviewed in this meta-analysis with a total of students evaluated in the reviewed works that amounts to 1,044, with the smallest sample size of 30 ( Del Pino-Yépez et al., 2019 ) and the largest with 570 ( Guevara Benítez et al., 2014 ). Regarding gender, 72% women and 28% men were included. Most of the sample comes from university degrees in social sciences, such as psychology and education (71.42%) followed by health sciences (14.28%) engineering and a publication (14.28%) that does not indicate origin. These publications selected according to the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis come from more countries with a variety of educational systems, but all from South America. Specifically, the countries that have more studies are Mexico (28.57%) and Colombia, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador with 14.28% each, respectively. The years in which they were published are 2.57% in 2018 and 2016 and 14.28% in 2019, 2014, and 2013.

A total of 57% of the studies analyze four levels of reading comprehension (literal, inferential, critical, and organizational) and 43% investigate three levels of reading comprehension (literal, inferential, and critical). Based on the moderating variables, 57% of the studies use standardized reading comprehension measures and 43% non-standardized measures. According to the evaluation test used, 29% use multiple-choice questions and 71% combine multiple-choice questions plus open questions. 43% use an argumentative text and 57% other types of texts (not indicated in studies). By type of career, 71% are students of social sciences and 29% of other different careers, such as engineering or health sciences. In addition, 71% are articles and 29% with research works (thesis and degree works).

Table 2 shows the reading comprehension assessment instruments used by the authors of the empirical research integrated into the meta-analysis.

Reading comprehension assessment tests used in higher education.

Meta-Analytic Analysis of the Level of Reading Comprehension

The literal level presents a mean proportion effect size of 56% (95% CI = 39–72%; Figure 2 ). The variability between the different samples of the literal level of reading comprehension was significant ( Q = 162.066, p < 0.001; I 2 = 96.3%). No moderating variable used in this research had a significant contribution to heterogeneity: type of measurement ( p = 0.520), type of test ( p = 0.114), type of text ( p = 0.520), type of career ( p = 0.235), and type of publication ( p = 0.585). The high variability is explained by other factors not considered in this work, such as the characteristics of the students (cognitive abilities) or other issues.

Forest plot of literal level.

The inferential level presents a mean proportion effect size of 33% (95% CI = 19–46%; Figure 3 ). The variability between the different samples of the inferential level of reading comprehension was significant ( Q = 125.123, p < 0.001; I 2 = 95.2%). The type of measure ( p = 0.011) and the type of text ( p = 0.011) had a significant contribution to heterogeneity. The rest of the variables had no significance: type of test ( p = 0.214), type of career ( p = 0.449), and type of publication ( p = 0.218). According to the type of measure, the proportion of students who have an optimal level in inferential administering a standardized test is 28.7% less than when a non-standardized test is administered. The type of measure reduces variability by 2.57% and explains the differences between the results of the studies at the inferential level. According to the type of text, the proportion of students who have an optimal level in inferential using an argumentative text is 28.7% less than when using another type of text. The type of text reduces the variability by 2.57% and explains the differences between the results of the studies at the inferential level.

Forest plot of inferential level.

The critical level has a mean effect size of the proportion of 22% (95% CI = 9–35%; Figure 4 ). The variability between the different samples of the critical level of reading comprehension was significant ( Q = 627.044, p < 0.001; I 2 = 99.04%). No moderating variable used in this research had a significant contribution to heterogeneity: type of measurement ( p = 0.575), type of test ( p = 0.691), type of text ( p = 0.575), type of career ( p = 0.699), and type of publication ( p = 0.293). The high variability is explained by other factors not considered in this work, such as the characteristics of the students (cognitive abilities).

Forest plot of critical level.

The organizational level presents a mean effect size of the proportion of 22% (95% CI = 6–37%; Figure 5 ). The variability between the different samples of the organizational level of reading comprehension was significant ( Q = 1799.366, p < 0.001; I 2 = 99.67%). The type of test made a significant contribution to heterogeneity ( p = 0.289). The other moderating variables were not significant in this research: type of measurement ( p = 0.289), type of text ( p = 0.289), type of career ( p = 0.361), and type of publication ( p = 0.371). Depending on the type of test, the proportion of students who have an optimal level in organizational with multiple-choices tests plus open questions is 37% higher than while using only multiple-choice tests. The type of text reduces the variability by 0.27% and explains the differences between the results of the studies at the organizational level.

Forest plot of organizational level.

Table 3 shows the difference between the estimated effect sizes and the significance. There is a larger proportion of students having an optimal level of reading comprehension at the literal level compared to the inferential, critical, and organizational level; an optimal level of reading comprehension at the inferential level vs. the critical and organizational level.

Results of effect size comparison.

Analysis of Publication Bias

This research uses two ways to verify the existence of bias independently of the sample size. Table 4 shows the results and there is no publication bias at any level of reading comprehension.

Publication bias results.

This research used a systematic literature search and meta-analysis to provide estimates of the number of cases of university students who have an optimal level in the different levels of reading comprehension. All the information available on the subject at the international level was analyzed using international databases in English and Spanish, but the potentially relevant publications were limited. Only seven Spanish language studies were identified internationally. In these seven studies, the optimal performance at each level of reading comprehension varied, finding heterogeneity associated with the very high estimates, which indicates that the summary estimates have to be interpreted with caution and in the context of the sample and the variables used in this meta-analysis.

In this research, the effects of the type of measure, type of test, type of text, type of career, and type of publication have been analyzed. Due to the limited information in the publications, it was not possible to assess the effect of any more moderating variables.

We found that some factors significantly influence heterogeneity according to the level of reading comprehension considered. The type of measure influenced the optimal performance of students in the inferential level of reading comprehension; specifically, the proportion of students who have an optimal level in inferential worsens if the test is standardized. Several studies ( Pike, 1996 ; Koretz, 2002 ) identify differences between standardized and non-standardized measures in reading comprehension and a favor of non-standardized measures developed by the researchers ( Pyle et al., 2017 ). The ability to generate inferences of each individual may difficult to standardize because each person differently identifies the relationship between the parts of the text and integrates it with their previous knowledge ( Oakhill, 1982 ; Cain et al., 2004 ). This mental representation of the meaning of the text is necessary to create a model of the situation and a deep understanding ( McNamara and Magliano, 2009 ; van den Broek and Espin, 2012 ).

The type of test was significant for the organizational level of reading comprehension. The proportion of students who have an optimal level in organizational improves if the reading comprehension assessment test is multiple-choice plus open questions. The organizational level requires the reordering of written information through analysis and synthesis processes ( Guevara Benítez et al., 2014 ); therefore, it constitutes a production task that is better reflected in open questions than in reproduction questions as multiple choice ( Dinsmore and Alexander, 2015 ). McNamara and Kintsch (1996) identify that open tasks require an effort to make inferences related to previous knowledge and multidisciplinary knowledge. Important is to indicate that different evaluation test formats can measure different aspects of reading comprehension ( Zheng et al., 2007 ).

The type of text significantly influenced the inferential level of reading comprehension. The proportion of students who have an optimal level in inferential decreases with an argumentative text. The expectations created before an argumentative text made it difficult to generate inferences and, therefore, the construction of the meaning of the text. This result is in the opposite direction to the study by Diakidoy et al. (2011) who find that the refutation text, such as the argumentative one, facilitates the elaboration of inferences compared to other types of texts. It is possible that the argumentative text, given its dialogical nature of arguments and counterarguments, with a subject unknown by the students, has determined the decrease of inferences based on their scarce previous knowledge of the subject, needing help to elaborate the structure of the text read ( Reznitskaya et al., 2007 ). It should be pointed out that in meta-analysis studies, 43% use argumentative texts. Knowing the type of the text is relevant for generating inferences, for instance, according to Baretta et al. (2009) the different types of text are processed differently in the brain generating more or fewer inferences; specifically, using the N400 component, they find that expository texts generate more inferences from the text read.

For the type of career and the type of publication, no significance was found at any level of reading comprehension in this sample. This seems to indicate that university students have the same level of performance in tasks of literal, critical inferential, and organizational understanding regardless of whether they are studying social sciences, health sciences, or engineering. Nor does the type of publication affect the state of the different levels of reading comprehension in higher education.

The remaining high heterogeneity at all levels of reading comprehension was not captured in this review, indicating that there are other factors, such as student characteristics, gender, or other issues, that are moderating and explaining the variability at the literal, inferential, critical, and organizational reading comprehension in university students.

To the comparison between the different levels of reading comprehension, the literal level has a significantly higher proportion of students with an optimal level than the inferential, critical, and organizational levels. The inferential level has a significantly higher proportion of students with an optimal level than the critical and organizational levels. This corresponds with data from other investigations ( Márquez et al., 2016 ; Del Pino-Yépez et al., 2019 ) that indicate that the literal level is where university students execute with more successes, being more difficult and with less success at the inferential, organizational, and critical levels. This indicates that university students of this sample do not generate a coherent situation model that provides them with a global mental representation of the read text according to the model of Kintsch (1998) , but rather they make a literal analysis of the explicit content of the read text. This level of understanding can lead to less desirable results in educational terms ( Dinsmore and Alexander, 2015 ).

The educational implications of this meta-analysis in this sample are aimed at making universities aware of the state of reading comprehension levels possessed by university students and designing strategies (courses and workshops) to optimize it by improving the training and employability of students. Some proposals can be directed to the use of reflection tasks, integration of information, graphic organizers, evaluation, interpretation, nor the use of paraphrasing ( Rahmani, 2011 ). Some studies ( Hong-Nam and Leavell, 2011 ; Parr and Woloshyn, 2013 ) demonstrate the effectiveness of instructional courses in improving performance in reading comprehension and metacognitive strategies. In addition, it is necessary to design reading comprehension assessment tests in higher education that are balanced, validated, and reliable, allowing to have data for the different levels of reading comprehension.

Limitations and Conclusion

This meta-analysis can be used as a starting point to report on reading comprehension levels in higher education, but the results should be interpreted with caution and in the context of the study sample and variables. Publications without sufficient data and inaccessible articles, with a sample of seven studies, may have limited the international perspective. The interest in studying reading comprehension in the mother tongue, using only unimodal texts, without the influence of technology and with English and Spanish has also limited the review. The limited amount of data in the studies has limited meta-regression.

This review is a guide to direct future research, broadening the study focus on the level of reading comprehension using digital technology, experimental designs, second languages, and investigations that relate reading comprehension with other factors (gender, cognitive abilities, etc.) that can explain the heterogeneity in the different levels of reading comprehension. The possibility of developing a comprehensive reading comprehension assessment test in higher education could also be explored.

This review contributes to the scientific literature in several ways. In the first place, this meta-analytic review is the only one that analyzes the proportion of university students who have an optimal performance in the different levels of reading comprehension. This review is made with international publications and this topic is mostly investigated in Latin America. Second, optimal performance can be improved at all levels of reading comprehension, fundamentally inferential, critical, and organizational. The literal level is significantly the level of reading comprehension with the highest proportion of optimal performance in university students. Third, the students in this sample have optimal performance at the inferential level when they are non-argumentative texts and non-standardized measures, and, in the analyzed works, there is optimal performance at the organizational level when multiple-choice questions plus open questions are used.

The current research is linked to the research project “Study of reading comprehension in higher education” of Asociación Educar para el Desarrollo Humano from Argentina.

Data Availability Statement

Author contributions.

Cd-l-P had the idea for the article and analyzed the data. ML-R searched the data. Cd-l-P and ML-R selected the data and contributed to the valuable comments and manuscript writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a shared affiliation though no other collaboration with one of the authors ML-R at the time of the review.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Funding. This paper was funded by the Universidad Internacional de la Rioja and Universidad de Málaga.

- Afflerbach P., Cho B.-Y., Kim J.-Y. (2015). Conceptualizing and assessing higher-order thinking in reading . Theory Pract. 54 , 203–212. 10.1080/00405841.2015.1044367 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alexander P. A. (2004). “ A model of domain learning: reinterpreting expertise as a multidimensional, multistage process ,” in Motivation, Emotion, and Cognition: Integrative Perspectives on Intellectual Functioning and Development. eds. Dai D. Y., Sternberg R. J. (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; ), 273–298. [ Google Scholar ]