Health Disparities

Ai generator.

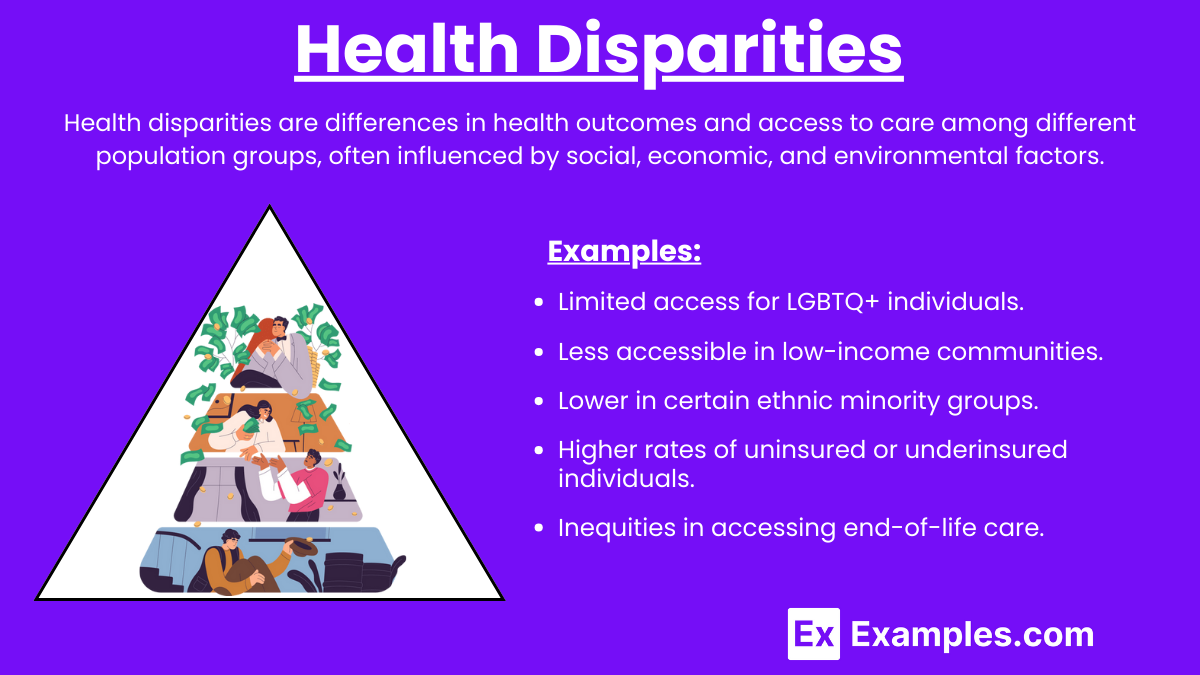

Health disparities are differences in health outcomes and access to healthcare among various population groups, often influenced by socioeconomic factors .

What Are Health Disparities?

Health disparities are differences in health outcomes among different populations, often due to socioeconomic factors. A Disparity Impact Statement highlights these inequities, while a Health Thesis Statement addresses their causes and solutions. Effective Health Communication is essential to mitigate these disparities.

Examples of Health Disparities

- Access to Healthcare : Rural areas often have fewer healthcare facilities compared to urban areas.

- Infant Mortality Rates : Higher in African American communities than in white communities.

- Life Expectancy : Shorter in low-income populations compared to higher-income groups.

- Chronic Diseases : Higher rates of diabetes in Hispanic and Native American populations.

- Mental Health Services : Limited access for LGBTQ+ individuals.

- Cancer Screening : Lower rates of breast cancer screening in uninsured women.

- Obesity : Higher prevalence in low-income neighborhoods.

- Vaccination Rates : Lower in certain ethnic minority groups.

- Heart Disease : Higher rates in African American men compared to white men.

- Substance Abuse Treatment : Less accessible in low-income communities.

Examples of Health Disparities in Rural Areas

- Limited Healthcare Facilities : Fewer hospitals and clinics compared to urban areas.

- Access to Specialists : Less availability of specialized medical care.

- Emergency Services : Longer response times for emergency medical services.

- Chronic Disease Management : Higher rates of unmanaged chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension. Mental Health Services : Scarcity of mental health professionals and facilities.

- Preventive Care : Lower rates of screenings and vaccinations.

- Health Education : Limited access to health education and resources.

- Transportation : Difficulties in accessing healthcare due to long distances and lack of public transportation.

- Health Insurance : Higher rates of uninsured or underinsured individuals.

- Substance Abuse : Increased rates of substance abuse with fewer treatment options.

Examples of Health Disparities in the Elderly

- Medication Management : Difficulty in accessing and affording necessary medications.

- Mobility Issues : Limited access to physical therapy and mobility aids.

- Nutrition : Higher risk of malnutrition due to financial constraints or limited availability of healthy food.

- Social Isolation : Increased risk of loneliness and mental health issues.

- Chronic Pain : Less effective pain management and treatment options.

- Dental Care : Limited access to dental services and higher rates of untreated dental issues.

- Vision and Hearing Care : Reduced access to eye and hearing examinations and corrective devices.

- In-Home Care : Limited availability of affordable in-home health care services.

- Palliative and Hospice Care : Inequities in accessing end-of-life care.

- Technology Access : Challenges in using telehealth services due to lack of familiarity with technology.

Examples of Health Disparities in Minority

- Language Barriers : Difficulty accessing healthcare due to lack of language services.

- Cultural Competence : Healthcare providers may lack understanding of cultural differences affecting treatment.

- Maternal Health : Higher rates of complications and mortality in pregnancy among African American and Native American women.

- HIV/AIDS : Disproportionately higher infection rates in minority populations.

- Asthma : Higher prevalence and severity in African American and Hispanic children.

- Mental Health Stigma : Greater stigma around mental health issues, leading to underutilization of mental health services.

- Environmental Health : Greater exposure to pollution and environmental hazards in minority communities.

- Hypertension : Higher rates and poorer management in African American and Latino populations.

- Diabetes : Increased prevalence and complications in Hispanic, African American, and Native American groups.

- Access to Healthy Food : Limited availability of fresh, affordable food in predominantly minority neighborhoods.

Examples of Health Disparities in Global

- Access to Clean Water : Many developing countries struggle with access to safe drinking water.

- Vaccination Rates : Lower vaccination rates in low-income countries, leading to preventable diseases.

- Maternal Mortality : Higher maternal mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

- Malnutrition : Widespread malnutrition in parts of Africa and Asia.

- Infectious Diseases : Higher prevalence of diseases like malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS in developing countries.

- Healthcare Infrastructure : Poor healthcare infrastructure in rural and low-income regions.

- Chronic Diseases : Rising rates of diabetes and heart disease in low- and middle-income countries.

- Child Mortality : Higher child mortality rates in poorer nations.

- Mental Health Services : Limited access to mental health care in many parts of the world.

- Health Education : Lack of health education and preventive care awareness in many global regions.

Potential Solutions for Health Disparities

1. Increase Access to Healthcare

- Expand Health Insurance Coverage: Ensure that everyone has access to affordable health insurance.

- Mobile Clinics: Use mobile clinics to reach remote and underserved areas.

- Telehealth Services: Promote the use of telehealth to provide healthcare services to people in rural and underserved areas.

2. Improve Health Education

- Community Health Programs: Implement health education programs in communities to raise awareness about preventive care and healthy lifestyles.

- School Health Education: Include comprehensive health education in school curriculums to teach children about nutrition, exercise, and disease prevention.

3. Address Social Determinants of Health

- Improve Housing: Ensure safe and affordable housing for all.

- Increase Income Support: Provide financial support to low-income families to reduce economic stress.

- Access to Healthy Foods: Promote access to affordable and nutritious foods in all communities.

4. Enhance Cultural Competence in Healthcare

- Cultural Training: Provide cultural competence training for healthcare providers to improve communication and trust with patients from diverse backgrounds.

- Diverse Healthcare Workforce: Increase diversity in the healthcare workforce to better reflect and understand the communities they serve.

5. Strengthen Community Partnerships

- Community Involvement: Engage community leaders and organizations in health planning and decision-making.

- Local Health Initiatives: Support local health initiatives that address specific community needs.

6. Implement Policy Changes

- Health Equity Policies: Advocate for policies that promote health equity and reduce disparities.

- Funding for Disparity Reduction Programs: Secure funding for programs specifically designed to address health disparities.

7. Improve Data Collection and Research

- Comprehensive Data Collection: Collect detailed data on health outcomes across different population groups to identify and address disparities.

- Research on Health Disparities: Fund research focused on understanding and finding solutions for health disparities.

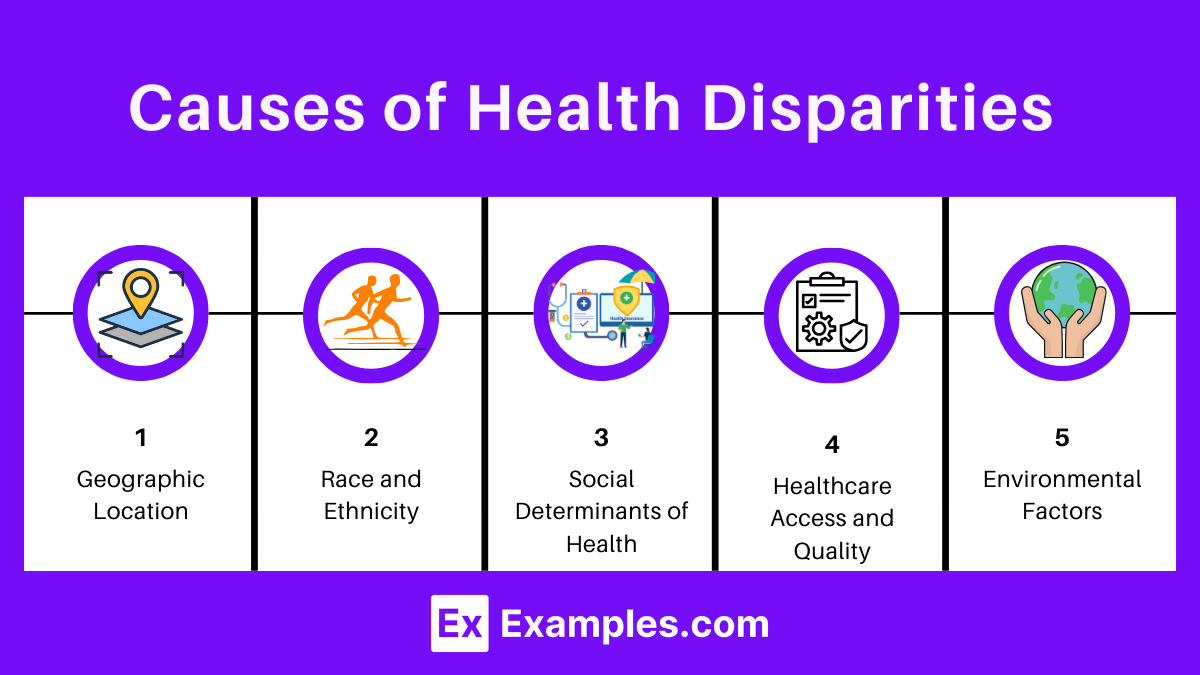

Causes of Health Disparities

1. Socioeconomic Status

- Income: Lower-income individuals often have limited access to healthcare services and healthy lifestyle choices.

- Education: Limited educational opportunities can lead to a lack of health knowledge and poor health behaviors.

- Employment: Unemployment or jobs without health benefits can restrict access to healthcare and preventive services.

2. Geographic Location

- Rural Areas: People living in rural areas may face barriers such as fewer healthcare facilities, longer travel distances to access care, and limited healthcare professionals.

- Urban Areas: In some urban areas, especially underserved neighborhoods, there can be a lack of healthcare resources and higher exposure to environmental health risks.

3. Race and Ethnicity

- Discrimination: Systemic racism and discrimination can lead to unequal treatment in healthcare settings.

- Cultural Barriers: Language differences and cultural beliefs can hinder effective communication and access to care.

- Genetic Factors: Some health conditions may be more prevalent in certain racial or ethnic groups due to genetic predispositions.

4. Social Determinants of Health

- Housing: Poor housing conditions, such as overcrowding and exposure to pollutants, can negatively impact health.

- Food Security: Lack of access to affordable, nutritious food can lead to poor health outcomes.

- Education and Literacy: Lower levels of education and health literacy can result in a lack of understanding of health information and how to navigate the healthcare system.

5. Healthcare Access and Quality

- Insurance Coverage: Lack of health insurance or underinsurance can limit access to necessary medical care.

- Healthcare Facilities: Inequitable distribution of healthcare facilities can create access issues for certain populations.

- Provider Availability: Shortages of healthcare providers, particularly in underserved areas, can lead to delays in receiving care.

6. Behavioral Factors

- Health Behaviors: Differences in lifestyle choices, such as diet, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption, can contribute to health disparities.

- Stress: Chronic stress, often more prevalent in disadvantaged communities, can have significant negative health effects.

7. Environmental Factors

- Exposure to Pollutants: Communities located near industrial areas or with poor environmental regulations may face higher exposure to harmful pollutants.

- Climate and Weather: Extreme weather conditions and climate-related events can disproportionately affect vulnerable populations.

8. Genetics and Biology

- Inherited Conditions: Certain genetic conditions can be more common in specific population groups.

- Biological Differences: Biological factors, such as age and sex, can influence health outcomes and susceptibility to diseases.

Types of Health Disparities

1. Racial and Ethnic Disparities

- Differences in health outcomes and healthcare access among racial and ethnic groups.

- Examples: Higher rates of diabetes in African Americans, higher rates of asthma in Hispanic communities.

2. Socioeconomic Disparities

- Differences in health based on income, education, and occupation.

- Examples: Low-income individuals having higher rates of chronic diseases, less access to preventive care for those with lower educational attainment.

3. Geographic Disparities

- Differences in health outcomes based on where people live.

- Examples: Rural areas having less access to hospitals and specialists, urban areas with high pollution affecting respiratory health.

4. Gender Disparities

- Differences in health outcomes between men and women.

- Examples: Women having higher rates of certain cancers (like breast cancer), men having higher rates of heart disease.

5. Age Disparities

- Differences in health based on age groups.

- Examples: Older adults experiencing more chronic conditions, children having higher rates of certain infectious diseases.

6. Disability Disparities

- Differences in health outcomes between those with and without disabilities.

- Examples: People with disabilities facing higher rates of obesity and depression.

7. LGBTQ+ Disparities

- Differences in health outcomes among LGBTQ+ individuals compared to the general population.

- Examples: Higher rates of mental health issues and HIV/AIDS in LGBTQ+ communities.

8. Insurance Status Disparities

- Differences in health outcomes based on whether individuals have health insurance.

- Examples: Uninsured individuals having less access to preventive services and higher mortality rates.

Health Disparities Synonym

- Health inequalities

- Health inequities

- Health differences

- Health gaps

- Health imbalances

- Health divides

- Health discrepancies

Health Disparities vs Health Inequities

| Differences in health outcomes among different population groups. | Unjust and avoidable differences in health outcomes among groups. | |

| Broad differences, can be measured. | Ethical and fairness aspects of health differences. | |

| Higher rates of diabetes in one ethnic group compared to another. | Lack of access to healthcare in low-income communities. | |

| Can be due to genetics, behavior, environment, etc. | Rooted in social, economic, and environmental disadvantages. | |

| Identifies where differences exist. | Highlights the need for systemic change to address unfairness. | |

| Targeted health programs, increased access to healthcare. | Policy changes, addressing social determinants of health. | |

| Statistical analysis of health data. | Examination of policies, practices, and social factors. |

Reasons for Health Disparities

- Economic Status : People with less money often have limited access to healthcare, healthy food, and safe housing.

- Education : Lower education levels are linked to poorer health outcomes because education influences job opportunities and health knowledge.

- Healthcare Access : Not having nearby healthcare facilities, insurance, or culturally competent care can prevent people from receiving proper health services.

- Neighborhood and Physical Environment : Living in areas with pollution, unsafe housing, and lack of parks or grocery stores can lead to health problems.

- Racial and Ethnic Background : Discrimination and systemic racism can lead to worse health outcomes for certain racial and ethnic groups.

- Gender : Health risks can vary between genders due to biological differences, social roles, and unequal power relations.

- Language Barriers : Non-native speakers may struggle to get good healthcare if they can’t communicate effectively with providers.

Addressing Health Disparities

- Improve Access to Healthcare : Make healthcare more available and affordable for everyone. This can include more clinics in underserved areas and better health insurance options.

- Educate the Community : Teach people about healthy habits and preventive care. Schools and community centers can offer classes on nutrition, exercise, and managing chronic diseases.

- Promote Fair Employment : Support policies that provide good jobs and fair pay to everyone. Healthy work environments and fair wages can greatly improve a person’s health.

- Enhance Local Environments : Make neighborhoods safer and more livable. This can involve cleaning up pollution, creating parks, and ensuring that everyone has access to healthy food.

- Support Research and Data Collection : Study health disparities and understand their causes. This can help tailor solutions to the specific needs of different communities.

- Cultural Competence in Healthcare : Train healthcare providers to understand and respect cultural differences. This helps in providing care that meets the unique needs of each patient.

- Advocate for Policy Changes : Support laws and policies that aim to reduce inequalities. This includes efforts to reduce poverty, discrimination, and improve education.

Maternal Health Disparities

- African American Women: Higher rates of maternal mortality and complications during pregnancy.

- Hispanic Women: Higher rates of gestational diabetes and lower access to prenatal care.

- Low-Income Women: Less access to quality prenatal and postnatal care, higher risk of complications.

- Uninsured Women: Limited access to necessary healthcare services during pregnancy.

- Rural Areas: Fewer healthcare facilities and specialists, longer travel times to receive care.

- Urban Underserved Areas: Limited access to quality maternity care and higher stress environments.

4. Age Disparities

- Teen Mothers: Higher risk of complications and lower access to prenatal care.

- Older Mothers: Increased risk of complications such as high blood pressure and diabetes.

5. Access to Healthcare

- Lack of Providers: Shortage of obstetricians and midwives in some areas.

- Insurance Issues: High costs and lack of coverage can limit access to care.

- Health Behaviors: Smoking, alcohol use, and poor nutrition can negatively impact maternal health.

- Mental Health: Stress and mental health issues can lead to poor pregnancy outcomes.

Tips for Health Disparities

- Increase Access to Care: Ensure everyone can access affordable, quality healthcare.

- Promote Health Education: Educate communities about preventive care and healthy lifestyles.

- Support Community Programs: Fund local health initiatives targeting underserved populations.

- Enhance Cultural Competence: Train healthcare providers in cultural awareness and sensitivity.

- Expand Insurance Coverage: Advocate for policies that provide comprehensive health insurance for all.

- Improve Data Collection: Collect and use data to identify and address disparities.

- Engage Local Leaders: Involve community leaders in health planning and decision-making.

What causes health disparities?

Health disparities are caused by factors such as socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, geographic location, and access to healthcare.

Who is affected by health disparities?

Health disparities affect racial and ethnic minorities, low-income individuals, rural residents, and other underserved groups.

How can health disparities be reduced?

Health disparities can be reduced by increasing access to healthcare, improving health education, addressing social determinants of health, and implementing equitable policies.

What role does education play in health disparities?

Education impacts health disparities by influencing health knowledge, behaviors, and access to resources for better health outcomes.

How does socioeconomic status affect health disparities?

Lower socioeconomic status often leads to limited access to healthcare, nutritious food, and safe living conditions, contributing to poorer health outcomes.

What are social determinants of health?

Social determinants of health include factors like income, education, employment, housing, and access to healthcare that influence health outcomes.

Can health disparities be completely eliminated?

While it may be challenging to completely eliminate health disparities, significant improvements can be made through targeted interventions and policy changes.

How does geographic location affect health disparities?

Geographic location impacts health disparities by limiting access to healthcare services, especially in rural and underserved urban areas.

What strategies can healthcare providers use to address health disparities?

Healthcare providers can use cultural competence training, provide language services, and engage with community leaders to address health disparities.

How does policy influence health disparities?

Policy influences health disparities by shaping access to healthcare, funding for health programs, and addressing social determinants of health.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

- < Previous

Home > Public Health > IPH_THESES > 761

Public Health Theses

Examining health disparities related to foodborne illnesses across racial and ethnic groups.

Reese Tierney Follow

Author ORCID Identifier

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5896-664X

Date of Award

Degree type, degree name.

Master of Public Health (MPH)

Public Health

First Advisor

Dr. Christine Stauber, PhD

Second Advisor

Dr. Erica Rose, PhD

Third Advisor

Dr. Daniel Weller, PhD

INTRODUCTION: Over the past decade, changes to surveillance systems and increased research studies examining health inequities across foodborne illnesses have created a new opportunity for additional research on this topic. There is a growing interest in using this lens to understand foodborne illness in the United States and the inclusion of variables such as race and ethnicity in active surveillance systems can help.

AIM: The purpose of this thesis was to identify current trends of documenting disparities of foodborne illness across populations and evaluate the mechanism of data representations through a literature review. To further explore the topics identified in the literature review, an analysis of salmonellosis data on the county level was conducted.

METHODS: The literature review was conducted as a pseudo-systematic review with the use of keywords and a restricted year timeline. For the salmonellosis analyses, the Laboratory-based Enteric Disease Surveillance (LEDS) system dataset was aggregated to the county-level for each year between 1997 and 2018, and joined with relevant metadata, including census data on race and ethnicity, CDC data on county urbanicity and social vulnerability indices (SVI), and USDA data on food environment.

RESULTS: Disparities of foodborne illnesses across racial and minority populations are prevalent across studies included in the literature review. Of the 35 studies reviewed, methods of racial and ethnic representation were inconsistent throughout with practices of collapsing and removal of different minority and ethnic groupings due to low numbers. The salmonellosis analysis found disparities of geometric mean salmonellosis incidence across both social vulnerability index themes and food insecurity variables when examined across levels of urbanicity.

DISCUSSION: Evidence of disparities in the burden of foodborne illnesses are prevalent in literature. The categorization of race and ethnicity is inconsistent across studies which may cause misrepresentation of these disparities. Understanding the influence of these socioeconomic, geographical, and environmental factors on the incidence of salmonellosis may help us understand the reason for differences in burden across populations with different community demographics.

https://doi.org/10.57709/28913861

Recommended Citation

Tierney, Reese, "Examining Health Disparities Related to Foodborne Illnesses Across Racial and Ethnic Groups." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2022. doi: https://doi.org/10.57709/28913861

File Upload Confirmation

Since April 29, 2022

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

- Submit ETD (Thesis/Dissertation)

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Downloadable Content

Qualitative Analysis of the Health Disparities within Public Health Policies that Affect Disadvantaged Communities

- Masters Thesis

- Aguirre, Nayely

- Valiquette L'Heureux, Anais

- Nufrio, Philip

- Clark, Shauna

- California State University, Northridge

- Public Sector Management and Leadership

- cultural competency

- health policies

- disadvantaged communities

- health disparities

- Dissertations, Academic -- CSUN -- Public Administration.

- 2019-08-21T16:15:38Z

- http://hdl.handle.net/10211.3/212836

- by Nayely Aguirre

- vii, 28 pages

| Thumbnail | Title | Date Uploaded | Visibility | Actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-10-05 | Public |

Items in ScholarWorks are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

25 Thesis Statement Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

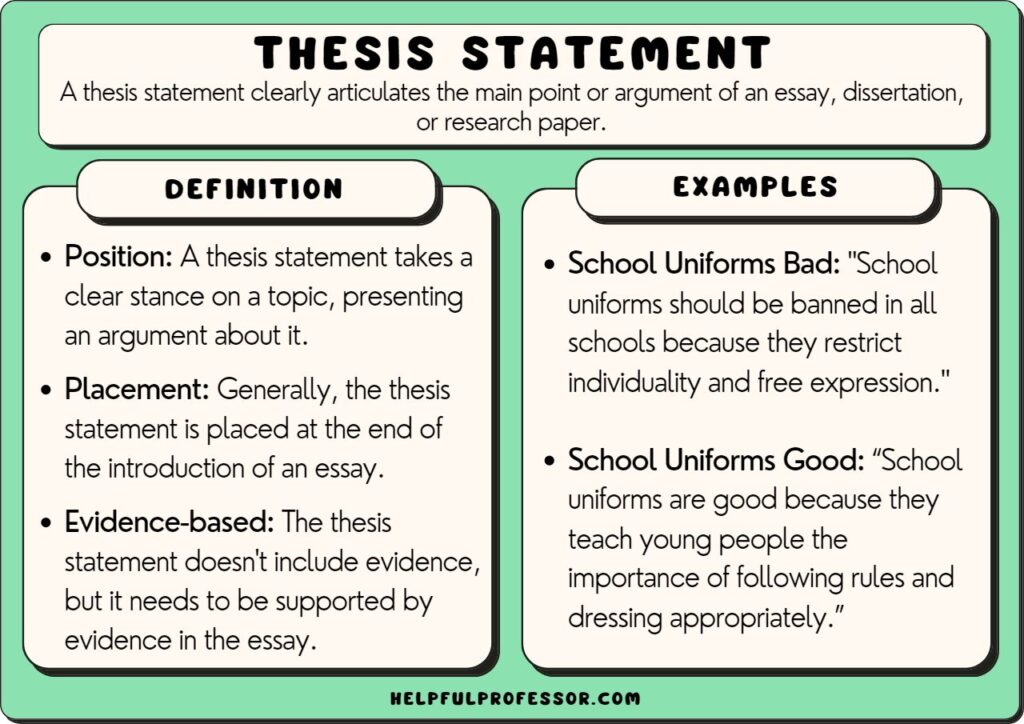

Learn about our Editorial Process

A thesis statement is needed in an essay or dissertation . There are multiple types of thesis statements – but generally we can divide them into expository and argumentative. An expository statement is a statement of fact (common in expository essays and process essays) while an argumentative statement is a statement of opinion (common in argumentative essays and dissertations). Below are examples of each.

Strong Thesis Statement Examples

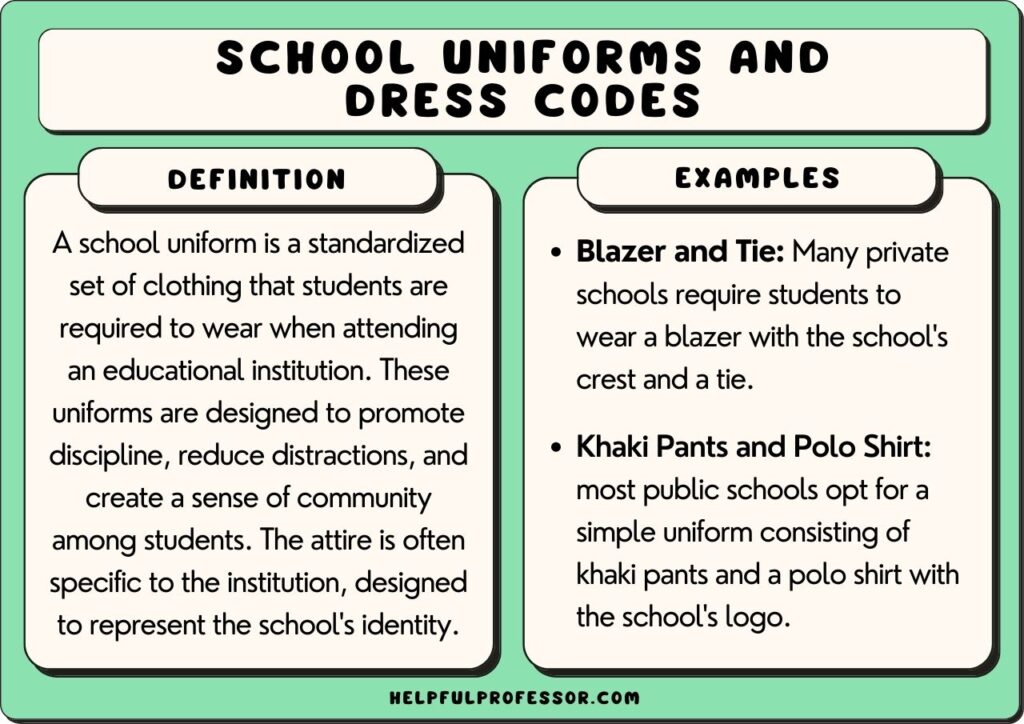

1. School Uniforms

“Mandatory school uniforms should be implemented in educational institutions as they promote a sense of equality, reduce distractions, and foster a focused and professional learning environment.”

Best For: Argumentative Essay or Debate

Read More: School Uniforms Pros and Cons

2. Nature vs Nurture

“This essay will explore how both genetic inheritance and environmental factors equally contribute to shaping human behavior and personality.”

Best For: Compare and Contrast Essay

Read More: Nature vs Nurture Debate

3. American Dream

“The American Dream, a symbol of opportunity and success, is increasingly elusive in today’s socio-economic landscape, revealing deeper inequalities in society.”

Best For: Persuasive Essay

Read More: What is the American Dream?

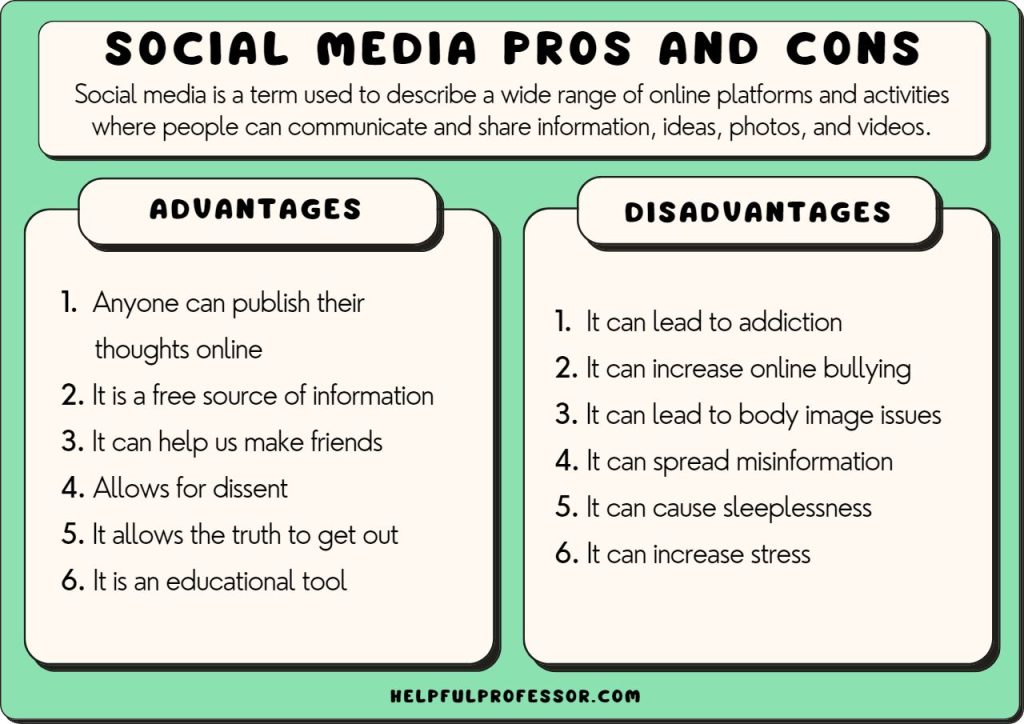

4. Social Media

“Social media has revolutionized communication and societal interactions, but it also presents significant challenges related to privacy, mental health, and misinformation.”

Best For: Expository Essay

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Social Media

5. Globalization

“Globalization has created a world more interconnected than ever before, yet it also amplifies economic disparities and cultural homogenization.”

Read More: Globalization Pros and Cons

6. Urbanization

“Urbanization drives economic growth and social development, but it also poses unique challenges in sustainability and quality of life.”

Read More: Learn about Urbanization

7. Immigration

“Immigration enriches receiving countries culturally and economically, outweighing any perceived social or economic burdens.”

Read More: Immigration Pros and Cons

8. Cultural Identity

“In a globalized world, maintaining distinct cultural identities is crucial for preserving cultural diversity and fostering global understanding, despite the challenges of assimilation and homogenization.”

Best For: Argumentative Essay

Read More: Learn about Cultural Identity

9. Technology

“Medical technologies in care institutions in Toronto has increased subjcetive outcomes for patients with chronic pain.”

Best For: Research Paper

10. Capitalism vs Socialism

“The debate between capitalism and socialism centers on balancing economic freedom and inequality, each presenting distinct approaches to resource distribution and social welfare.”

11. Cultural Heritage

“The preservation of cultural heritage is essential, not only for cultural identity but also for educating future generations, outweighing the arguments for modernization and commercialization.”

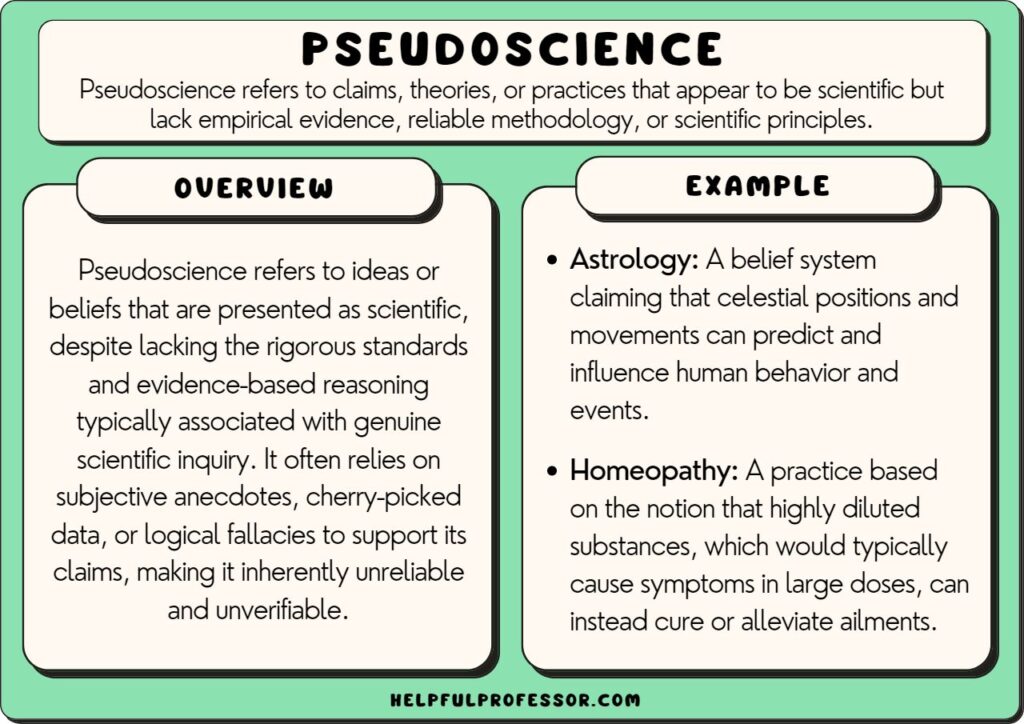

12. Pseudoscience

“Pseudoscience, characterized by a lack of empirical support, continues to influence public perception and decision-making, often at the expense of scientific credibility.”

Read More: Examples of Pseudoscience

13. Free Will

“The concept of free will is largely an illusion, with human behavior and decisions predominantly determined by biological and environmental factors.”

Read More: Do we have Free Will?

14. Gender Roles

“Traditional gender roles are outdated and harmful, restricting individual freedoms and perpetuating gender inequalities in modern society.”

Read More: What are Traditional Gender Roles?

15. Work-Life Ballance

“The trend to online and distance work in the 2020s led to improved subjective feelings of work-life balance but simultaneously increased self-reported loneliness.”

Read More: Work-Life Balance Examples

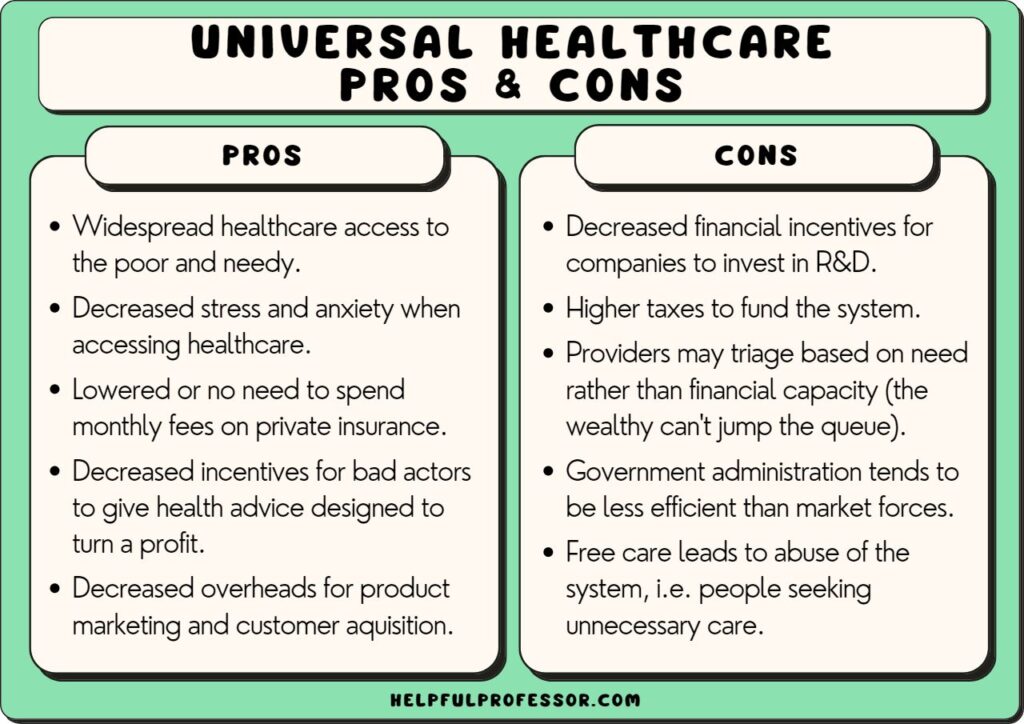

16. Universal Healthcare

“Universal healthcare is a fundamental human right and the most effective system for ensuring health equity and societal well-being, outweighing concerns about government involvement and costs.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Universal Healthcare

17. Minimum Wage

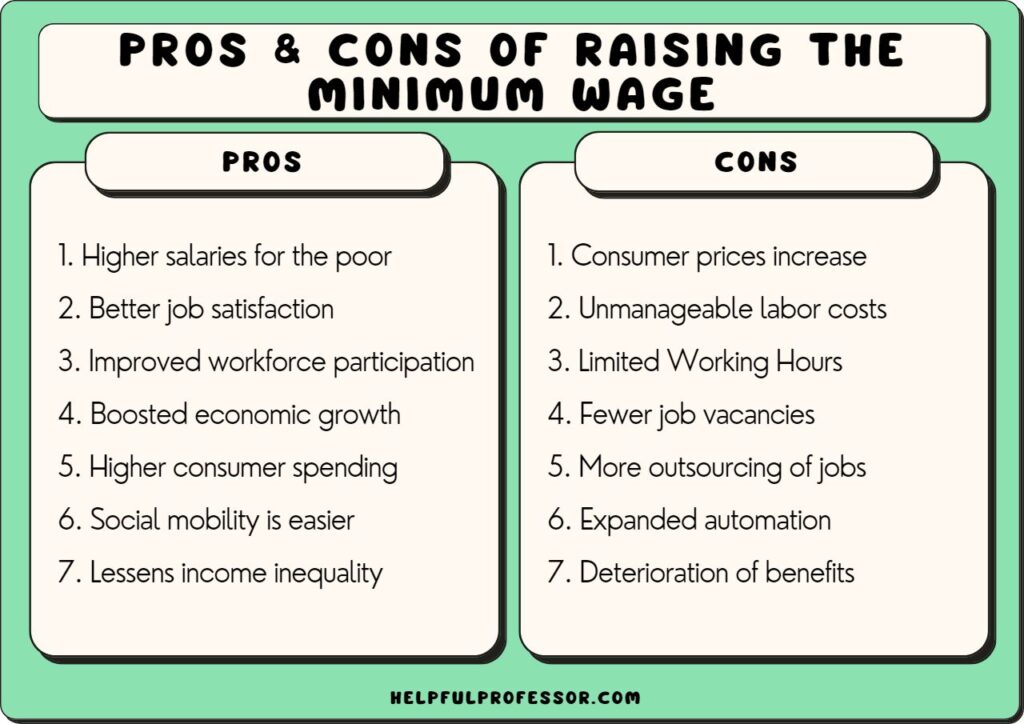

“The implementation of a fair minimum wage is vital for reducing economic inequality, yet it is often contentious due to its potential impact on businesses and employment rates.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Raising the Minimum Wage

18. Homework

“The homework provided throughout this semester has enabled me to achieve greater self-reflection, identify gaps in my knowledge, and reinforce those gaps through spaced repetition.”

Best For: Reflective Essay

Read More: Reasons Homework Should be Banned

19. Charter Schools

“Charter schools offer alternatives to traditional public education, promising innovation and choice but also raising questions about accountability and educational equity.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of Charter Schools

20. Effects of the Internet

“The Internet has drastically reshaped human communication, access to information, and societal dynamics, generally with a net positive effect on society.”

Read More: The Pros and Cons of the Internet

21. Affirmative Action

“Affirmative action is essential for rectifying historical injustices and achieving true meritocracy in education and employment, contrary to claims of reverse discrimination.”

Best For: Essay

Read More: Affirmative Action Pros and Cons

22. Soft Skills

“Soft skills, such as communication and empathy, are increasingly recognized as essential for success in the modern workforce, and therefore should be a strong focus at school and university level.”

Read More: Soft Skills Examples

23. Moral Panic

“Moral panic, often fueled by media and cultural anxieties, can lead to exaggerated societal responses that sometimes overlook rational analysis and evidence.”

Read More: Moral Panic Examples

24. Freedom of the Press

“Freedom of the press is critical for democracy and informed citizenship, yet it faces challenges from censorship, media bias, and the proliferation of misinformation.”

Read More: Freedom of the Press Examples

25. Mass Media

“Mass media shapes public opinion and cultural norms, but its concentration of ownership and commercial interests raise concerns about bias and the quality of information.”

Best For: Critical Analysis

Read More: Mass Media Examples

Checklist: How to use your Thesis Statement

✅ Position: If your statement is for an argumentative or persuasive essay, or a dissertation, ensure it takes a clear stance on the topic. ✅ Specificity: It addresses a specific aspect of the topic, providing focus for the essay. ✅ Conciseness: Typically, a thesis statement is one to two sentences long. It should be concise, clear, and easily identifiable. ✅ Direction: The thesis statement guides the direction of the essay, providing a roadmap for the argument, narrative, or explanation. ✅ Evidence-based: While the thesis statement itself doesn’t include evidence, it sets up an argument that can be supported with evidence in the body of the essay. ✅ Placement: Generally, the thesis statement is placed at the end of the introduction of an essay.

Try These AI Prompts – Thesis Statement Generator!

One way to brainstorm thesis statements is to get AI to brainstorm some for you! Try this AI prompt:

💡 AI PROMPT FOR EXPOSITORY THESIS STATEMENT I am writing an essay on [TOPIC] and these are the instructions my teacher gave me: [INSTUCTIONS]. I want you to create an expository thesis statement that doesn’t argue a position, but demonstrates depth of knowledge about the topic.

💡 AI PROMPT FOR ARGUMENTATIVE THESIS STATEMENT I am writing an essay on [TOPIC] and these are the instructions my teacher gave me: [INSTRUCTIONS]. I want you to create an argumentative thesis statement that clearly takes a position on this issue.

💡 AI PROMPT FOR COMPARE AND CONTRAST THESIS STATEMENT I am writing a compare and contrast essay that compares [Concept 1] and [Concept2]. Give me 5 potential single-sentence thesis statements that remain objective.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Health Disparities: Analysis and Possible Solutions Essay

Introduction, potential solutions, ethical principles.

Social, economic, political, geographic factors, and much more affect people’s wellbeing. As individuals have different access to financial resources, housing, and healthy foods, some encounter health-related problems. The combination of these factors is called a health disparity, and it disproportionately impacts minority groups. The root of healthcare inequity is challenging to pinpoint, as it is connected to several historical and geographical factors. However, in most cases, the cause of health disparities lies in the various elements it includes, such as socioeconomic status and one’s physical environment. The present analysis is concerned with the problem of health disparities and potential solutions based on current research and a community approach.

The healthcare research on health disparities contains many studies that consider a specific problem or population, such as minorities or low-income households. Nevertheless, some articles also present general descriptions of interventions and ways to approach this issue systematically. For instance, Agurs-Collins et al. (2019) discuss the process of designing multilevel interventions to reduce health disparities among minorities. According to the authors, addressing racial/ethnic and socioeconomic inequalities is often difficult as they require healthcare professionals to collaborate with other specialists (Agurs-Collins et al., 2019). Therefore, it can be argued that programs for interventions have to have robust planning and participation to succeed.

Furthermore, it is necessary to highlight the recent role of COVID-19 in the issue of health inequity. Greenaway et al. (2020) present an outlook on how COVID-19 has exacerbated many groups’ disparities – racial/ethnic minorities have experienced higher rates of infection and worse access to care and vaccination. Examples of health disparity interventions can be taken from the review by Haldane et al. (2019), who focus on community participation. The listed papers are used in the following analysis and are credible and relevant to the discussion due to their focus.

Health disparities can affect people from all nations, but they affect disadvantaged populations. Therefore, the setting in which one lives is a crucial determinant of potential health risks. For instance, such factors as poverty, environmental hazards, access to proper nutrition and healthcare, housing, education quality, and access to it influence one’s wellbeing. These elements of one’s life can be changed, but they often are affected by other underlying problems. These immutable characteristics include one’s race/ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation and identity, disability. They are linked to discrimination risk or different health-related needs. These vulnerable groups are at higher risk of poverty, violence, and prejudice, which negatively affects their physical and mental health (Agurs-Collins et al., 2019). As health disparities affect whole communities rather than individuals, this problem is fundamental for modern healthcare research, which seeks systematic solutions.

For example, COVID-19 has shown the impact of health disparities on ethnic minorities and migrants. While the infection is dangerous for all people, health inequities have made COVID-19 a great risk for the health and survival of vulnerable groups. Greenaway et al. (2020) reported that, in New York City, African Americans and Latinos were twice as likely to die from the infection in comparison to white people. In the United Kingdom, the risk among Asian and Black residents was also higher than that of the white population (Greenaway et al., 2020). Based on these statistics, the connection between ethnicity and COVID-19-related deaths lies in minorities’ poor socioeconomic standing, healthcare barriers, and higher comorbidities rates (Greenaway et al., 2020). Thus, one can see how ethnicity is among the factors that influence health inequity through the combination of other contributing elements.

To address health disparities, an intervention has to acknowledge and manage a variety of underlying problems that lead to inequities affecting vulnerable communities. Therefore, significant resources and interprofessional collaboration are necessary for any program to succeed. According to Brown et al. (2019), a structural intervention is the best approach for reducing health disparities – it should include authentic engagement and a disease-agnostic view. Therefore, community organizing, planning, issue prioritization, and other tactics are vital for developing a program that appropriately recognizes the weak and strong points in the current setting.

Ignoring the issue of health disparities can further exacerbate its risks for affected populations. As noted by Greenaway et al. (2020), the lack of preparedness to address the spread of COVID-19 among minorities has led to higher mortality and infection rates – people with no access to healthcare and medications have to deal with severe cases on their own. This example demonstrates why interventions on a wide scale are necessary to implement as soon as possible. Haldane et al. (2019) suggest that community-based programs are a viable solution for lowering the impact of health disparities. The potential benefit of this approach is the higher engagement of the affected groups, which increases their knowledge and leads to higher participation rates (Haldane et al., 2019). However, a community participation program also requires significant time for preparation, planning, and implementation, as the community’s needs are not dictated by health agencies but by the affected members.

To implement a community participation health improvement program, one has to create a planning team that includes professionals and community representatives. Then, several meetings are held to determine which issues the affected population deems the most important to resolve (Haldane et al., 2019). Based on this information, goals and strategies are formulated, implemented, monitored, and analyzed. In this case, one needs time, funding, and an appropriate and rigorous evaluation system. A robust organizational process is crucial to the outcome of such interventions, which rely on the ideas shared by community members.

The proposed intervention’s implementation aligns with the four ethical principles in healthcare. First, following the principle of beneficence, this program aims to improve population health and reduce the impact of health disparities on vulnerable groups. Second, as the reduction of health disparities allows people to get better access to healthcare and improves their overall wellbeing, it is in agreement with the idea of nonmaleficence. Community participation is inspired by people’s right to autonomy and justice – vulnerable groups are given the tools to find factors that affect their health and improve them. Research presents a plethora of examples that show positive outcomes of community-based interventions for reducing health inequities. Haldane et al. (2019) present a review of such cases, demonstrating better health education, higher vaccination and medication rates, overall satisfaction with the intervention, and more. The results of community participation have been recorded in several countries, including the United States.

Health disparities are a complex issue based on many socioeconomic and immutable factors. Affected groups include racial/ethnic minorities, disabled people, migrants, low-income households, and other minority communities. It is necessary to address health inequities with a multilayered intervention as it needs to simultaneously target several spheres of one’s life. Therefore, a community participation solution is proposed to correctly assess the needs of the vulnerable group and develop a program based on their view of the issue. This approach supports the ethical principles of health care and gives people autonomy over their wellbeing.

Agurs-Collins, T., Persky, S., Paskett, E. D., Barkin, S. L., Meissner, H. I., Nansel, T. R., Arteaga, S., Zhang, X., Das, R., & Farhat, T. (2019). Designing and assessing multilevel interventions to improve minority health and reduce health disparities. American Journal of Public Health , 109 (S1), S86-S93. Web.

Brown, A. F., Ma, G. X., Miranda, J., Eng, E., Castille, D., Brockie, T., Jones, P., Airhihenbuwa, C., Farhat, T., Zhu, L., & Trinh-Shevrin, C. (2019). Structural interventions to reduce and eliminate health disparities. American Journal of Public Health , 109 (S1), S72-S78. Web.

Greenaway, C., Hargreaves, S., Barkati, S., Coyle, C. M., Gobbi, F., Veizis, A., & Douglas, P. (2020). COVID-19: Exposing and addressing health disparities among ethnic minorities and migrants. Journal of Travel Medicine , 27 (7), taaa113. Web.

Haldane, V., Chuah, F. L., Srivastava, A., Singh, S. R., Koh, G. C., Seng, C. K., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2019). Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: A systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PloS One , 14 (5), e0216112. Web.

- Reducing Tobacco Usage Among the Single Males

- Health Hazard: Source, Awareness, and Protection

- Addressing Health Disparities During COVID-19

- Health Disparities Among Minorities in the US

- The Concept of Healthcare Disparities

- Advanced Directive Legislation in Healthcare

- Impact of Disparity on People’s Health

- Health Policy to Solve Premature Death Inequality

- Lifestyle Choices and Mental Health

- Accelerating Access to Critical Therapies Policy

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, March 6). Health Disparities: Analysis and Possible Solutions. https://ivypanda.com/essays/health-disparities-analysis-and-possible-solutions/

"Health Disparities: Analysis and Possible Solutions." IvyPanda , 6 Mar. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/health-disparities-analysis-and-possible-solutions/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Health Disparities: Analysis and Possible Solutions'. 6 March.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Health Disparities: Analysis and Possible Solutions." March 6, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/health-disparities-analysis-and-possible-solutions/.

1. IvyPanda . "Health Disparities: Analysis and Possible Solutions." March 6, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/health-disparities-analysis-and-possible-solutions/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Health Disparities: Analysis and Possible Solutions." March 6, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/health-disparities-analysis-and-possible-solutions/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- Flashes Safe Seven

- FlashLine Login

- Faculty & Staff Phone Directory

- Emeriti or Retiree

- All Departments

- Maps & Directions

- Building Guide

- Departments

- Directions & Parking

- Faculty & Staff

- Give to University Libraries

- Library Instructional Spaces

- Mission & Vision

- Newsletters

- Circulation

- Course Reserves / Core Textbooks

- Equipment for Checkout

- Interlibrary Loan

- Library Instruction

- Library Tutorials

- My Library Account

- Open Access Kent State

- Research Support Services

- Statistical Consulting

- Student Multimedia Studio

- Citation Tools

- Databases A-to-Z

- Databases By Subject

- Digital Collections

- Discovery@Kent State

- Government Information

- Journal Finder

- Library Guides

- Connect from Off-Campus

- Library Workshops

- Subject Librarians Directory

- Suggestions/Feedback

- Writing Commons

- Academic Integrity

- Jobs for Students

- International Students

- Meet with a Librarian

- Study Spaces

- University Libraries Student Scholarship

- Affordable Course Materials

- Copyright Services

- Selection Manager

- Suggest a Purchase

Library Locations at the Kent Campus

- Architecture Library

- Fashion Library

- Map Library

- Performing Arts Library

- Special Collections and Archives

Regional Campus Libraries

- East Liverpool

- College of Podiatric Medicine

- Kent State University

- Health Disparities

- Choosing a Topic

Health Disparities: Choosing a Topic

- Important General Information

- Literature Search Tips

- Data, Statistics, and Government Information

- Need More Help?

- APA Resources and Citation Help

Health Disparities Reports and Information

- CDC Health Disparities and Inequalities Report, United States, 2013 This second CDC report addresses health differences relative to race, ethnicity, and more!

- 2021 Health Disparities Report From the United Health Foundation

- 2019 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report From AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

- Healthy People 2030

- Health Disparities from MedlinePlus.gov

Explore the many facets of health disparities using the links to high-quality information on these topical pages from MedlinePlus.gov produced by the National Library of Medicine:

- Population Groups Explore health issues experienced by specific population groups. Some examples include: groups based on age range, race and ethnicity, veteran status, and LGBTQ+ status.

Social Determinants of Health

- What are Social Determinants of Health? (CDC)

- NCHHSTP Social Determinants of Health From The National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention

- Social Determinants of Health Index from the CDC

- Healthy People 2030 Social Determinants of Health

Intervention Information

- CDC Strategies for Reducing Health Disparities 2016

- HHS Action Plan to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities

- 2020 Update to HHS Action Plan

- Healthy People 2030 Objectives Information on health conditions, health behaviors, populations, settings and systems, and social determinants of health

- << Previous: Important General Information

- Next: Literature Search Tips >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2024 3:13 PM

- URL: https://libguides.library.kent.edu/PH44000

Street Address

Mailing address, quick links.

- How Are We Doing?

- Student Jobs

Information

- Accessibility

- Emergency Information

- For Our Alumni

- For the Media

- Jobs & Employment

- Life at KSU

- Privacy Statement

- Technology Support

- Website Feedback

Making the Elimination of Health Disparities a Personal Priority

Published April 30, 2013, last updated on April 9, 2018 under Voices of DGHI

By Jocelyn Streid This essay is a winner in the Duke School of Nursing’s Global Health Essay Contest .

“When most people think about crime, poverty, and hunger, they picture the inner city. They picture dirty streets and gangs and chain link fences. They don’t picture rolling hills or clear brooks or houses nestled in the woods. They don’t think rural. They don’t think about us.”

The words of one of my research mentors has stuck with me three years after I spent a summer with her in a Appalachian town about the size of my high school. I was teaching smoking cessation classes and studying how faith communities might serve as important social networks for preventative health interventions to target, but I was also learning about a culture that was not my own. The town was a hub of extraordinary Appalachian oral history, art, and music, but it was also a place where fast food dominated the restaurant scene. It was a place where many lacked health insurance but everyone knew friends, family members, and neighbors who had died of preventable and treatable illnesses. It was a place where diabetes and lung cancer ran rampant, where hospitals were half a day away, where food stamps didn’t cut it, and where many I knew dreaded the monthly onslaught of bills. In the Appalachian town, I learned that health isn’t just about malignant cells or defunct immune systems or viral invasions – it’s also about food accessibility, whether or not your friends smoke, HIV/AIDS education, and the poverty line. It’s a place that broke my heart, but it’s also a place that taught me I want to be a doctor who will serve the underserved.

Since that summer, I’ve used my college career to explore issues of health equity and fairness in various forms. The summer after my sophomore year, I explored rural health abroad. After interning in a public hospital in middle-of-nowhere South Africa for two months, I learned how the residues of structural racism, combined with crippling poverty and poor government policy, perpetuate conditions that produce HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malnutrition. Healthcare was free to all, but when hospital staff complained about patients as if they weren’t there and the “good” doctors were the ones who had to falsify patients’ CD4 counts to get them the government anti-retroviral medications they needed but didn’t quite yet qualify for, the hospital was an alienating institution for those of low income and little education – one that scared people off as often as it helped them.

Soon after, I spent a semester studying global health disparities in both India and China through the Global Semester Abroad program. By conducting interviews and listening to narratives of villagers in rural Rajasthan and migrant laborers on the outskirts of Beijing, I learned how the nuances of culture can serve as impediments to good health. My research informed the policies of a local health NGO, and my photography helped them publicize their mission. I’m currently working with a Duke professor to share my photo essays with a larger audience.

Unable to forget my experiences in South Africa, I spent last summer in London, conducting research on palliative care in sub-Saharan Africa. Lack of resources has placed the burden of end-of-life care on family members of the dying, who often lack the time, education, money, and emotional strength to bear the strain of their responsibilities. I’m working with King’s College of London to submit my research for publication. Meanwhile, my work in health disparities continues here at Duke, as I write a senior thesis on palliative care in America.

As I become a doctor dedicated to palliative care for the underserved, I’ll move forward with the conviction that neither a good life or a good death ought to be denied to anyone on the basis of geographical location, socioeconomic status, social capital, or education. I suspect that my career will take me to rural areas with few doctors and academic institutions where there are many; wherever I am, I know that my time in the Appalachian town will forever shape the way I think about medicine, community, policy, and equality.

- Health care access ,

- Occupational health

Related News

Around DGHI

Turning AI's Hype into a Realistic Hope for Global Healthcare

October 7, 2024

Education News

New Global Health Students Bring International Flavor

August 23, 2024

Student Stories

Notes from the Field: Tobenna Ndulue MS’25

August 8, 2024

Warning: The NCBI web site requires JavaScript to function. more...

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003.

Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISPARITIES IN HEALTH CARE: AN ETHICAL ANALYSIS OF WHEN AND HOW THEY MATTER

Madison Powers and Ruth Faden

The Kennedy Institute of Ethics

Georgetown University

- Introduction

Recent health services research literature has called attention to the existence of a variety of disparities in the health services received by racial and ethnic minorities. As well, racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes from various health services, including screening, diagnosis, and treatment for specific diseases or medical conditions have also been noted. Such findings provide the impetus for the consideration of two primary moral questions in this paper. First, when do ethnic and racial disparities in the receipt of health services matter morally? Second, when do racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes among patient groups matter morally?

Our approach in answering these questions takes the form of two theses. Our first thesis, the neutrality thesis , is that disparities in health outcomes among patient groups with presumptively similar medical conditions should trigger moral scrutiny. Our second thesis, the anti-discrimination thesis, is that disparities in receipt of health care or adverse health outcomes among racial, ethnic or other disadvantaged patient groups should trigger heightened moral scrutiny. The theses are presented as lenses through which the morally salient features of health services can be viewed. Most theories of justice can accept some version of both the neutrality thesis and the anti-discrimination thesis. However, as we shall see, these theories differ in the nature and strength of their moral conclusions and in the reasoning they employ in reaching those conclusions.

The bulk of this paper will focus on the foundations of the theses, their relation to competing accounts of justice, and the considerations relevant to their moral analysis. In Section II, we articulate the moral foundations for the neutrality and anti-discrimination theses, and in Section III, we examine some potentially morally relevant considerations that inform the conclusions from the perspectives of alternative theoretical frameworks. Finally, in Section IV, we consider the moral implications of these findings for physicians and other health care providers.

The preliminary task, however, is to clarify several conceptual issues lurking in the formulation of the theses. Although the theses overlap in certain important respects, it is even more important to be clear about how they differ.

Differences Between the Neutrality Thesis and the Anti-Discrimination Thesis

The first conceptual distinction has to do with who is covered under the thesis. The neutrality thesis covers disparities in health outcomes among any patient groups with presumptively similar medical conditions and prognoses. By contrast, the anti-discrimination thesis refers specifically to a subset of what falls under the neutrality thesis–the special case in which the outcome disparities involve racial, ethnic or other disadvantaged patient groups.

The second conceptual distinction has to do with what is covered. The neutrality thesis covers only disparities in health outcomes. But the anti-discrimination thesis, which specifies that the disparity must occur in a disadvantaged social group, means that disparities in the health care services people receive, and not just the outcomes they experience, also matter.

The neutrality thesis is thus intended to cover any instance in which it is established that there are differences in outcomes among patient groups that are in relevant respects otherwise medically similar. If it was determined, for example, that white men with colon cancer had poorer survival rates than African- American men with colon cancer, then the neutrality thesis should trigger the same moral scrutiny as if the situation was reversed. In addition, this claim would hold even if it was clear that there were no differences in the medical services the two groups received. However, what if it was determined that white men were less likely than African- American men to have screening colonoscopies after age 50? As long as this disparity did not result in different medical outcomes, there are no moral implications under the neutrality thesis.

In contrast, the anti-discrimination thesis assumes that disparities in both health services received and disparities in health outcomes are independent and distinct reasons for moral concern when the disparities disfavor racial and ethnic groups. These groups are “morally suspect categories,” understood here as analogous to legally suspect categories in equal protection law. Under the anti-discrimination thesis, either type of disparity-- alone or in combination is treated as morally problematic as long as the disparity disfavors a morally suspect group. This is markedly different from the neutrality thesis, in which disparities in utilization are only problematic if they have a disparate impact on health outcomes.

Underlying the neutrality thesis is the implicit assumption that the moral value of medical interventions is generally instrumental. In other words, whether it is good or bad to receive or fail to receive-- a medical intervention depends on the impact each option would have on individual health and well-being. . In the case of racial and ethnic minorities, however, a different moral value is at stake. The very fact that a minority population might receive fewer services believed to be beneficial suggests the potential for morally culpable discrimination. This is a significant moral concern in its own right, regardless of the medical consequences. Under the anti-discrimination thesis, disparities of either sort trigger an additional or heightened level of moral scrutiny beyond that warranted by health outcomes disparities generally. i

- Moral Foundations for the Two Theses

Thus far, we have merely articulated some of the implications of and analytic differences between the two theses and the implications of the differing forms of moral judgment that can flow from the use of either moral lens. In this section, we offer a philosophical defense of the two theses and link them to the more general theoretical foundations on which they rest.

A principle that has come to be known as the formal principle of equality is often the starting point for discussions as to when some sort of disparity or inequality in the way persons are treated (in a more general sense than meant in health care contexts) is morally problematic. It is a minimal conception of equality attributed to Aristotle, who argued that persons ought to be treated equally unless they differ in virtue of some morally relevant attributes. It is, of course, critical to determine in any particular context just which attributes are morally relevant and which are not. Often these determinations are matters of disagreement and controversy that can be traced to significant differences in rival theories of justice. The degree of agreement across theories of justice on the matters under discussion in this paper is, therefore, surprising.

Libertarian Theories

Consider first a type of theory of justice many would think least likely to agree with either the neutrality thesis or the anti-discrimination thesis. The libertarian theorist rejects any pattern of distribution as the proper aim of justice, arguing instead that whatever pattern of distribution emerges from un-coerced contracts and agreements is morally justified (Nozick, 1974). Moreover, coercive attempts by the state to enforce a preferred pattern of distribution are themselves viewed as unjust. To the libertarian, inequalities are counted as merely unfortunate and not unjust, unless they are the product of some intentional harm or injury.

Initially, one might think that the libertarian position leaves little room for objecting to disparities in health outcomes among patient groups, whether defined along racial lines or otherwise, or to disparities in the receipt of health services among racial and ethnic groups. As long as patient preferences are not overridden and no harm to those patients was intended, no injustice or other moral failing would obtain. Indeed, it seems highly unlikely that the libertarian could accept the neutrality thesis, failing to see any basis for demanding moral scrutiny merely because some patient groups fare less well than other patient groups.

The libertarian conclusion may well be different, however, when, as contemplated by the anti-discrimination thesis, the patient groups involve morally suspect categories. Some conceptual room is left open for endorsement of the anti-discrimination thesis, and that room is a consequence of the limited domain of moral judgment for which the libertarian theory is meant to apply. The libertarian view is primarily a theory of societal obligation, or what society collectively owes its members, and not a comprehensive moral doctrine spelling out the full range of individual or other non-governmental moral obligations. Libertarians often assert that particular individuals have duties of mutual aid, even fairly stringent ones, even though state coercion to enforce them would be unjust (Engelhardt, 1996), as do certain non-governmental institutions and professional bodies that assume certain social functions as part of their self-defined moral missions. Thus, even in the libertarian view, the failure of individuals and institutions to offer health services to all racial groups on an equal basis can be a significant basis for moral condemnation.

A point of particular significance for this discussion is that nothing in the libertarian view necessarily excludes the existence of parallel moral obligations that are rolespecific, such as those ordinarily obtaining between physician and patient. Such special obligations are often referred to as agent-relative obligations. Some libertarians have argued that because of the existence of these agent-relative obligations, which in their view form the core of our moral requirements, coercive state action is morally condemnable. Such interference is said to be morally condemnable insofar as it may interfere with an individual's most basic agent-relative moral duties (Mack, 1991). The libertarian, therefore, may limit what government may do to enforce cer tain individual moral obligations, but it does not purport to be a comprehensive moral doctrine that effaces those individual obligations.

The upshot is that the libertarian view, even in its strictest form, need not reject a thesis asserting that disparities involving racial and ethnic minorities should trigger special moral scrutiny. However, libertarians will locate their judgment of moral failing in the failure of specific individuals or institutions to discharge their moral duties, not in the society at large. Nor would the libertarian necessarily see the moral problem as a failure of government to enforce neutrality in the receipt of care or achievement of the outcomes that specific individuals and institutions are properly committed to achieving.

In sum, even libertarianism, the theory of justice least compatible with the neutrality thesis, can substantially endorse the anti-discrimination thesis as applied to disparities in the receipt of services and in health outcomes. When using the lens of the anti-discrimination thesis, a libertarian might reach a more modest moral conclusion than the one we shall defend,and a libertarian does not endorse the more inclusive moral concern shown for disparities in health outcomes embodied in the neutrality thesis. However, in Section III, we explore some instances in which the libertarian view might agree with our conclusion that some patterns of racial and ethnic disparities should be counted as injustices, and not simply moral failings.

Egalitarian Theories

A family of justice theories known as egalitarian theories offers more solid support for both the neutrality thesis and the anti-discrimination thesis, even as those theories diverge substantially in their theoretical foundations. Egalitarians, unlike libertarians, are intrinsically concerned with the existence of inequalities. Egalitarians themselves differ as to how much inequality they find morally tolerable, the reasons they find inequalities to be morally problematic, and the kinds of inequalities they consider to be the central job of justice to combat.

One strand of egalitarianism prominent in the bioethics and health policy literature borrows heavily from the work of John Rawls (Rawls, 1971). The first principle of the Rawlsian theory is that everyone should be entitled first to an equal bundle of civil liberties (e.g., political and voting rights, freedom of religion, freedom of expression, etc), which shall not be abridged even for the sake of the greater welfare of society overall. Secondarily, everyone should be guaranteed a fair equality of opportunity. That principle of fair equality is given a robust, substantive interpretation such that permissible inequalities in such things as income and wealth work to the advantage of the least well-off segments of society. Fair equality of opportunity is thus a term of art, signaling more than a formal commitment to non-discrimination, but also an affirmative commitment to resources necessary to ensure that all citizens of comparable abilities can compete on equal terms. For Rawls, this commitment means a guarantee of educational resources sufficient for all persons to pursue opportunities such as jobs and positions of authority available to others within society.

Norman Daniels seizes on Rawls's core arguments (Daniels,1985). He accepts the core Rawlsian framework but offers a friendly amendment to the Rawlsian theory. Daniels claims that once we acknowledge that there are considerable differences in the health of individuals and that the consequence of those differences is that individuals differ substantially in their opportunities to pursue lifeplans, we must relax Rawls's own assumption about the rough equality of persons. Once this assumption is relaxed, the theory has implications for how we think about healthcare resources. If, as Daniels argues, health is especially strategic in the realization of fair equality of opportunity, and that healthcare services (broadly construed by Daniels) make a limited but important contribution to health, then we derive a right to healthcare sufficient to pursue reasonable life opportunities. The logic of Daniels' account clearly lends support to the neutrality thesis in as much as disparities in health outcomes are precisely the sort of consequences that the principle of fair equality of opportunity treats as unjust and therefore, as proper objects of remedial governmental action.

In addition, Daniels' version of the Rawlsian theory can be seen as lending support for the anti-discrimination thesis, although this is not an element of Daniels' theory that he himself highlights. For example, the theoretical support for treating inequalities in health outcomes among racial groups as unjust, as distinguished from a rationale that makes inequalities among persons generally unjust because of their adverse impact on equality of opportunity, lies in its endorsement of Rawls' core notion of a formal principle of equality. Rawls and Daniels both start their discussion of equality of opportunity with the formal principle that morally irrelevant distinctions should not be employed as a basis for determining the range of life opportunities open to persons. Matters of race, gender, and the like are counted as irrelevant, so if their claims are plausible, then even disparities in services received ( as well as disparities in health outcomes) based on racial and ethnic categories warrant some moral scrutiny.

Other members of the egalitarian family of justice theories offer more direct support for both theses. The “capabilities” approach argues that it is the job of justice to protect and facilitate a plurality of irreducibly valuable capabilities or functionings (Sen, 1992; Nussbaum, 2000). Capabilities theorists, led by Amartya Sen, generate slightly different lists of the core human capabilities central to the job of justice, but all converge on the idea that a variety of health functionings, including longevity and absence of morbidity, are among those centrally important human capabilities. Unlike the modified Rawlsian concept, which makes the importance of health and hence healthcare derivatively important because of health'se specially strategic role in preserving equality of opportunity, the capabilities approach reaches similar conclusions about the intrinsic importance of health, and more directly, the goods instrumental to its realization. Based on Sen's theory, inequalities among any of the core capabilities are matters of moral concern. Thus, as the neutrality thesis asserts, any finding of disparities in health outcomes should trigger moral scrutiny.

Among the core capabilities included on Sen's list are capacities for all to live their lives with the benefit of mutual respect and free from invidious discrimination.Thus, support for the anti-discrimination thesis also flows naturally from the capabilities approach inasmuch as the value of equal human dignity and respect is of fundamental moral importance, as is health. Disparities in services received, no less than disparities in health outcomes, therefore trigger a heightened moral scrutiny under a theory that renders inequalities of both sorts morally problematic.

Democratic Political Theory

Libertarian and egalitarian theories are two broad theoretical traditions that at face value seem to have the greatest divergence in their implications. However, they have been shown to result in greater convergence, at least on the anti-discrimination thesis, than might otherwise be suspected. Apart from the (perhaps) unexpected convergence of two quite different comprehensive moral theories on the interpretation of the formal principle of equality, there are additional philosophical arguments favoring the anti-discrimination thesis that do not require taking sides with any comprehensive moral views.

Recent work in political philosophy by John Rawls begins with the assumption of what he calls a reasonable pluralism of comprehensive moral views (Rawls, 1993). In a democratic nation, persons motivated to reach agreement on the basic social structure, understood as shared basis for social cooperation, will seek an overlapping consensus on some evaluative questions. That consensus will necessarily include a commitment to the view of each person as a free and equal citizen. While critics have questioned how much substantive moral content can be derived from this perspective, they generally agree that some underlying commitments are widely shared in any democracy (Gutmann and Thompson, 1996). Among them are the ideas that the interests of all should be given equal weight regardless of race, creed, color, gender or other attributes deemed morally irrelevant. Although such a notion does not settle the deeper moral question of which attributes are morally irrelevant, the crucial point is that such views form the bedrock of most Western democracies. Underlying this desire for equal respect and concern is the vague but powerful idea of human dignity and the importance we attach to equality of treatment for the least advantaged that the more powerful members of society have secured for themselves (Harris, 1988).

Thus, although there is a diversity of possible justifications for the importance of health and healthcare services, there is widespread basis for agreement that inequalities in health outcomes that track racial and ethnic lines, especially when racial and ethnic lines also track other indices of social disadvantage, are ethically problematic. This feature of democratic theory, reflected also in equal protection law, justifies at minimum the added moral scrutiny required by the anti-discrimination thesis.

- The Relevance of Causal Stories

So far we have established that egalitarian theories, and in particular capability theory, provide moral justification for the neutrality thesis. Thus, even with a libertarian view, the failure of individuals and institutions to offer health services to all racial groups on an equal basis can be a significant basis for moral condemnation. Even if the moral scrutiny demanded by the neutrality thesis and the added moral scrutiny demanded by the anti-discrimination thesis are warranted, this is not the final word. All that has been established thus far is that governments and health care institutions have a moral obligation to investigate identified disparities. The key questions are how governments and health care institutions should interpret the moral meaning of the results of such an investigation, whether disparities should be considered injustices, and under what conditions. On many moral accounts, an evaluation of the explanations for the disparities is needed to make a judgment about whether the disparities represent an injustice. In other words, whether disparities in health outcomes or in the services patients receive constitute an injustice depends for some on the causal story that stands behind the disparity. Thus, while there may be wide agreement about the moral imperative to investigate identified disparities, at least with respect to morally suspect groups, there is far less agreement about how to interpret the moral significance of the results of such an investigation.

The moral significance of causality is a difficult sticking point in moral philosophy. There is a natural inclination in theories of individual morality, as there is in law, to bind moral responsibility and causal responsibility together. We do not ordinarily think, for example, in law or morality, that an individual is morally culpable for adverse consequences arising from circumstances over which that individual had no control. Lack of causal efficacy is the end of the story for many assessments of moral and legal responsibility. Moreover, a judgment of causal responsibility is a threshold concern for many accounts of individual moral and legal responsibility, and the presence of some causal contribution to the harm of others opens the door to legal analysis. Theories of justice, however, are more varied and often more controversial than the individual model in their understandings of the relation between causal and moral responsibility.

Libertarian Views of the Relevance of Causal Explanations