- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Results

Research results refer to the findings and conclusions derived from a systematic investigation or study conducted to answer a specific question or hypothesis. These results are typically presented in a written report or paper and can include various forms of data such as numerical data, qualitative data, statistics, charts, graphs, and visual aids.

Results Section in Research

The results section of the research paper presents the findings of the study. It is the part of the paper where the researcher reports the data collected during the study and analyzes it to draw conclusions.

In the results section, the researcher should describe the data that was collected, the statistical analysis performed, and the findings of the study. It is important to be objective and not interpret the data in this section. Instead, the researcher should report the data as accurately and objectively as possible.

Structure of Research Results Section

The structure of the research results section can vary depending on the type of research conducted, but in general, it should contain the following components:

- Introduction: The introduction should provide an overview of the study, its aims, and its research questions. It should also briefly explain the methodology used to conduct the study.

- Data presentation : This section presents the data collected during the study. It may include tables, graphs, or other visual aids to help readers better understand the data. The data presented should be organized in a logical and coherent way, with headings and subheadings used to help guide the reader.

- Data analysis: In this section, the data presented in the previous section are analyzed and interpreted. The statistical tests used to analyze the data should be clearly explained, and the results of the tests should be presented in a way that is easy to understand.

- Discussion of results : This section should provide an interpretation of the results of the study, including a discussion of any unexpected findings. The discussion should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Limitations: This section should acknowledge any limitations of the study, such as sample size, data collection methods, or other factors that may have influenced the results.

- Conclusions: The conclusions should summarize the main findings of the study and provide a final interpretation of the results. The conclusions should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Recommendations : This section may provide recommendations for future research based on the study’s findings. It may also suggest practical applications for the study’s results in real-world settings.

Outline of Research Results Section

The following is an outline of the key components typically included in the Results section:

I. Introduction

- A brief overview of the research objectives and hypotheses

- A statement of the research question

II. Descriptive statistics

- Summary statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation) for each variable analyzed

- Frequencies and percentages for categorical variables

III. Inferential statistics

- Results of statistical analyses, including tests of hypotheses

- Tables or figures to display statistical results

IV. Effect sizes and confidence intervals

- Effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d, odds ratio) to quantify the strength of the relationship between variables

- Confidence intervals to estimate the range of plausible values for the effect size

V. Subgroup analyses

- Results of analyses that examined differences between subgroups (e.g., by gender, age, treatment group)

VI. Limitations and assumptions

- Discussion of any limitations of the study and potential sources of bias

- Assumptions made in the statistical analyses

VII. Conclusions

- A summary of the key findings and their implications

- A statement of whether the hypotheses were supported or not

- Suggestions for future research

Example of Research Results Section

An Example of a Research Results Section could be:

- This study sought to examine the relationship between sleep quality and academic performance in college students.

- Hypothesis : College students who report better sleep quality will have higher GPAs than those who report poor sleep quality.

- Methodology : Participants completed a survey about their sleep habits and academic performance.

II. Participants

- Participants were college students (N=200) from a mid-sized public university in the United States.

- The sample was evenly split by gender (50% female, 50% male) and predominantly white (85%).

- Participants were recruited through flyers and online advertisements.

III. Results

- Participants who reported better sleep quality had significantly higher GPAs (M=3.5, SD=0.5) than those who reported poor sleep quality (M=2.9, SD=0.6).

- See Table 1 for a summary of the results.

- Participants who reported consistent sleep schedules had higher GPAs than those with irregular sleep schedules.

IV. Discussion

- The results support the hypothesis that better sleep quality is associated with higher academic performance in college students.

- These findings have implications for college students, as prioritizing sleep could lead to better academic outcomes.

- Limitations of the study include self-reported data and the lack of control for other variables that could impact academic performance.

V. Conclusion

- College students who prioritize sleep may see a positive impact on their academic performance.

- These findings highlight the importance of sleep in academic success.

- Future research could explore interventions to improve sleep quality in college students.

Example of Research Results in Research Paper :

Our study aimed to compare the performance of three different machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Neural Network) in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company. We collected a dataset of 10,000 customer records, with 20 predictor variables and a binary churn outcome variable.

Our analysis revealed that all three algorithms performed well in predicting customer churn, with an overall accuracy of 85%. However, the Random Forest algorithm showed the highest accuracy (88%), followed by the Support Vector Machine (86%) and the Neural Network (84%).

Furthermore, we found that the most important predictor variables for customer churn were monthly charges, contract type, and tenure. Random Forest identified monthly charges as the most important variable, while Support Vector Machine and Neural Network identified contract type as the most important.

Overall, our results suggest that machine learning algorithms can be effective in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company, and that Random Forest is the most accurate algorithm for this task.

Example 3 :

Title : The Impact of Social Media on Body Image and Self-Esteem

Abstract : This study aimed to investigate the relationship between social media use, body image, and self-esteem among young adults. A total of 200 participants were recruited from a university and completed self-report measures of social media use, body image satisfaction, and self-esteem.

Results: The results showed that social media use was significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem. Specifically, participants who reported spending more time on social media platforms had lower levels of body image satisfaction and self-esteem compared to those who reported less social media use. Moreover, the study found that comparing oneself to others on social media was a significant predictor of body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem.

Conclusion : These results suggest that social media use can have negative effects on body image satisfaction and self-esteem among young adults. It is important for individuals to be mindful of their social media use and to recognize the potential negative impact it can have on their mental health. Furthermore, interventions aimed at promoting positive body image and self-esteem should take into account the role of social media in shaping these attitudes and behaviors.

Importance of Research Results

Research results are important for several reasons, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research results can contribute to the advancement of knowledge in a particular field, whether it be in science, technology, medicine, social sciences, or humanities.

- Developing theories: Research results can help to develop or modify existing theories and create new ones.

- Improving practices: Research results can inform and improve practices in various fields, such as education, healthcare, business, and public policy.

- Identifying problems and solutions: Research results can identify problems and provide solutions to complex issues in society, including issues related to health, environment, social justice, and economics.

- Validating claims : Research results can validate or refute claims made by individuals or groups in society, such as politicians, corporations, or activists.

- Providing evidence: Research results can provide evidence to support decision-making, policy-making, and resource allocation in various fields.

How to Write Results in A Research Paper

Here are some general guidelines on how to write results in a research paper:

- Organize the results section: Start by organizing the results section in a logical and coherent manner. Divide the section into subsections if necessary, based on the research questions or hypotheses.

- Present the findings: Present the findings in a clear and concise manner. Use tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data and make the presentation more engaging.

- Describe the data: Describe the data in detail, including the sample size, response rate, and any missing data. Provide relevant descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations, and ranges.

- Interpret the findings: Interpret the findings in light of the research questions or hypotheses. Discuss the implications of the findings and the extent to which they support or contradict existing theories or previous research.

- Discuss the limitations : Discuss the limitations of the study, including any potential sources of bias or confounding factors that may have affected the results.

- Compare the results : Compare the results with those of previous studies or theoretical predictions. Discuss any similarities, differences, or inconsistencies.

- Avoid redundancy: Avoid repeating information that has already been presented in the introduction or methods sections. Instead, focus on presenting new and relevant information.

- Be objective: Be objective in presenting the results, avoiding any personal biases or interpretations.

When to Write Research Results

Here are situations When to Write Research Results”

- After conducting research on the chosen topic and obtaining relevant data, organize the findings in a structured format that accurately represents the information gathered.

- Once the data has been analyzed and interpreted, and conclusions have been drawn, begin the writing process.

- Before starting to write, ensure that the research results adhere to the guidelines and requirements of the intended audience, such as a scientific journal or academic conference.

- Begin by writing an abstract that briefly summarizes the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

- Follow the abstract with an introduction that provides context for the research, explains its significance, and outlines the research question and objectives.

- The next section should be a literature review that provides an overview of existing research on the topic and highlights the gaps in knowledge that the current research seeks to address.

- The methodology section should provide a detailed explanation of the research design, including the sample size, data collection methods, and analytical techniques used.

- Present the research results in a clear and concise manner, using graphs, tables, and figures to illustrate the findings.

- Discuss the implications of the research results, including how they contribute to the existing body of knowledge on the topic and what further research is needed.

- Conclude the paper by summarizing the main findings, reiterating the significance of the research, and offering suggestions for future research.

Purpose of Research Results

The purposes of Research Results are as follows:

- Informing policy and practice: Research results can provide evidence-based information to inform policy decisions, such as in the fields of healthcare, education, and environmental regulation. They can also inform best practices in fields such as business, engineering, and social work.

- Addressing societal problems : Research results can be used to help address societal problems, such as reducing poverty, improving public health, and promoting social justice.

- Generating economic benefits : Research results can lead to the development of new products, services, and technologies that can create economic value and improve quality of life.

- Supporting academic and professional development : Research results can be used to support academic and professional development by providing opportunities for students, researchers, and practitioners to learn about new findings and methodologies in their field.

- Enhancing public understanding: Research results can help to educate the public about important issues and promote scientific literacy, leading to more informed decision-making and better public policy.

- Evaluating interventions: Research results can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, such as treatments, educational programs, and social policies. This can help to identify areas where improvements are needed and guide future interventions.

- Contributing to scientific progress: Research results can contribute to the advancement of science by providing new insights and discoveries that can lead to new theories, methods, and techniques.

- Informing decision-making : Research results can provide decision-makers with the information they need to make informed decisions. This can include decision-making at the individual, organizational, or governmental levels.

- Fostering collaboration : Research results can facilitate collaboration between researchers and practitioners, leading to new partnerships, interdisciplinary approaches, and innovative solutions to complex problems.

Advantages of Research Results

Some Advantages of Research Results are as follows:

- Improved decision-making: Research results can help inform decision-making in various fields, including medicine, business, and government. For example, research on the effectiveness of different treatments for a particular disease can help doctors make informed decisions about the best course of treatment for their patients.

- Innovation : Research results can lead to the development of new technologies, products, and services. For example, research on renewable energy sources can lead to the development of new and more efficient ways to harness renewable energy.

- Economic benefits: Research results can stimulate economic growth by providing new opportunities for businesses and entrepreneurs. For example, research on new materials or manufacturing techniques can lead to the development of new products and processes that can create new jobs and boost economic activity.

- Improved quality of life: Research results can contribute to improving the quality of life for individuals and society as a whole. For example, research on the causes of a particular disease can lead to the development of new treatments and cures, improving the health and well-being of millions of people.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

How To Write The Discussion Chapter

The what, why & how explained simply (with examples).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD Cand). Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

If you’re reading this, chances are you’ve reached the discussion chapter of your thesis or dissertation and are looking for a bit of guidance. Well, you’ve come to the right place ! In this post, we’ll unpack and demystify the typical discussion chapter in straightforward, easy to understand language, with loads of examples .

Overview: Dissertation Discussion Chapter

- What (exactly) the discussion chapter is

- What to include in your discussion chapter

- How to write up your discussion chapter

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

What exactly is the discussion chapter?

The discussion chapter is where you interpret and explain your results within your thesis or dissertation. This contrasts with the results chapter, where you merely present and describe the analysis findings (whether qualitative or quantitative ). In the discussion chapter, you elaborate on and evaluate your research findings, and discuss the significance and implications of your results.

In this chapter, you’ll situate your research findings in terms of your research questions or hypotheses and tie them back to previous studies and literature (which you would have covered in your literature review chapter). You’ll also have a look at how relevant and/or significant your findings are to your field of research, and you’ll argue for the conclusions that you draw from your analysis. Simply put, the discussion chapter is there for you to interact with and explain your research findings in a thorough and coherent manner.

What should I include in the discussion chapter?

First things first: in some studies, the results and discussion chapter are combined into one chapter . This depends on the type of study you conducted (i.e., the nature of the study and methodology adopted), as well as the standards set by the university. So, check in with your university regarding their norms and expectations before getting started. In this post, we’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as this is most common.

Basically, your discussion chapter should analyse , explore the meaning and identify the importance of the data you presented in your results chapter. In the discussion chapter, you’ll give your results some form of meaning by evaluating and interpreting them. This will help answer your research questions, achieve your research aims and support your overall conclusion (s). Therefore, you discussion chapter should focus on findings that are directly connected to your research aims and questions. Don’t waste precious time and word count on findings that are not central to the purpose of your research project.

As this chapter is a reflection of your results chapter, it’s vital that you don’t report any new findings . In other words, you can’t present claims here if you didn’t present the relevant data in the results chapter first. So, make sure that for every discussion point you raise in this chapter, you’ve covered the respective data analysis in the results chapter. If you haven’t, you’ll need to go back and adjust your results chapter accordingly.

If you’re struggling to get started, try writing down a bullet point list everything you found in your results chapter. From this, you can make a list of everything you need to cover in your discussion chapter. Also, make sure you revisit your research questions or hypotheses and incorporate the relevant discussion to address these. This will also help you to see how you can structure your chapter logically.

Need a helping hand?

How to write the discussion chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear idea of what the discussion chapter is and what it needs to include, let’s look at how you can go about structuring this critically important chapter. Broadly speaking, there are six core components that need to be included, and these can be treated as steps in the chapter writing process.

Step 1: Restate your research problem and research questions

The first step in writing up your discussion chapter is to remind your reader of your research problem , as well as your research aim(s) and research questions . If you have hypotheses, you can also briefly mention these. This “reminder” is very important because, after reading dozens of pages, the reader may have forgotten the original point of your research or been swayed in another direction. It’s also likely that some readers skip straight to your discussion chapter from the introduction chapter , so make sure that your research aims and research questions are clear.

Step 2: Summarise your key findings

Next, you’ll want to summarise your key findings from your results chapter. This may look different for qualitative and quantitative research , where qualitative research may report on themes and relationships, whereas quantitative research may touch on correlations and causal relationships. Regardless of the methodology, in this section you need to highlight the overall key findings in relation to your research questions.

Typically, this section only requires one or two paragraphs , depending on how many research questions you have. Aim to be concise here, as you will unpack these findings in more detail later in the chapter. For now, a few lines that directly address your research questions are all that you need.

Some examples of the kind of language you’d use here include:

- The data suggest that…

- The data support/oppose the theory that…

- The analysis identifies…

These are purely examples. What you present here will be completely dependent on your original research questions, so make sure that you are led by them .

Step 3: Interpret your results

Once you’ve restated your research problem and research question(s) and briefly presented your key findings, you can unpack your findings by interpreting your results. Remember: only include what you reported in your results section – don’t introduce new information.

From a structural perspective, it can be a wise approach to follow a similar structure in this chapter as you did in your results chapter. This would help improve readability and make it easier for your reader to follow your arguments. For example, if you structured you results discussion by qualitative themes, it may make sense to do the same here.

Alternatively, you may structure this chapter by research questions, or based on an overarching theoretical framework that your study revolved around. Every study is different, so you’ll need to assess what structure works best for you.

When interpreting your results, you’ll want to assess how your findings compare to those of the existing research (from your literature review chapter). Even if your findings contrast with the existing research, you need to include these in your discussion. In fact, those contrasts are often the most interesting findings . In this case, you’d want to think about why you didn’t find what you were expecting in your data and what the significance of this contrast is.

Here are a few questions to help guide your discussion:

- How do your results relate with those of previous studies ?

- If you get results that differ from those of previous studies, why may this be the case?

- What do your results contribute to your field of research?

- What other explanations could there be for your findings?

When interpreting your findings, be careful not to draw conclusions that aren’t substantiated . Every claim you make needs to be backed up with evidence or findings from the data (and that data needs to be presented in the previous chapter – results). This can look different for different studies; qualitative data may require quotes as evidence, whereas quantitative data would use statistical methods and tests. Whatever the case, every claim you make needs to be strongly backed up.

Step 4: Acknowledge the limitations of your study

The fourth step in writing up your discussion chapter is to acknowledge the limitations of the study. These limitations can cover any part of your study , from the scope or theoretical basis to the analysis method(s) or sample. For example, you may find that you collected data from a very small sample with unique characteristics, which would mean that you are unable to generalise your results to the broader population.

For some students, discussing the limitations of their work can feel a little bit self-defeating . This is a misconception, as a core indicator of high-quality research is its ability to accurately identify its weaknesses. In other words, accurately stating the limitations of your work is a strength, not a weakness . All that said, be careful not to undermine your own research. Tell the reader what limitations exist and what improvements could be made, but also remind them of the value of your study despite its limitations.

Step 5: Make recommendations for implementation and future research

Now that you’ve unpacked your findings and acknowledge the limitations thereof, the next thing you’ll need to do is reflect on your study in terms of two factors:

- The practical application of your findings

- Suggestions for future research

The first thing to discuss is how your findings can be used in the real world – in other words, what contribution can they make to the field or industry? Where are these contributions applicable, how and why? For example, if your research is on communication in health settings, in what ways can your findings be applied to the context of a hospital or medical clinic? Make sure that you spell this out for your reader in practical terms, but also be realistic and make sure that any applications are feasible.

The next discussion point is the opportunity for future research . In other words, how can other studies build on what you’ve found and also improve the findings by overcoming some of the limitations in your study (which you discussed a little earlier). In doing this, you’ll want to investigate whether your results fit in with findings of previous research, and if not, why this may be the case. For example, are there any factors that you didn’t consider in your study? What future research can be done to remedy this? When you write up your suggestions, make sure that you don’t just say that more research is needed on the topic, also comment on how the research can build on your study.

Step 6: Provide a concluding summary

Finally, you’ve reached your final stretch. In this section, you’ll want to provide a brief recap of the key findings – in other words, the findings that directly address your research questions . Basically, your conclusion should tell the reader what your study has found, and what they need to take away from reading your report.

When writing up your concluding summary, bear in mind that some readers may skip straight to this section from the beginning of the chapter. So, make sure that this section flows well from and has a strong connection to the opening section of the chapter.

Tips and tricks for an A-grade discussion chapter

Now that you know what the discussion chapter is , what to include and exclude , and how to structure it , here are some tips and suggestions to help you craft a quality discussion chapter.

- When you write up your discussion chapter, make sure that you keep it consistent with your introduction chapter , as some readers will skip from the introduction chapter directly to the discussion chapter. Your discussion should use the same tense as your introduction, and it should also make use of the same key terms.

- Don’t make assumptions about your readers. As a writer, you have hands-on experience with the data and so it can be easy to present it in an over-simplified manner. Make sure that you spell out your findings and interpretations for the intelligent layman.

- Have a look at other theses and dissertations from your institution, especially the discussion sections. This will help you to understand the standards and conventions of your university, and you’ll also get a good idea of how others have structured their discussion chapters. You can also check out our chapter template .

- Avoid using absolute terms such as “These results prove that…”, rather make use of terms such as “suggest” or “indicate”, where you could say, “These results suggest that…” or “These results indicate…”. It is highly unlikely that a dissertation or thesis will scientifically prove something (due to a variety of resource constraints), so be humble in your language.

- Use well-structured and consistently formatted headings to ensure that your reader can easily navigate between sections, and so that your chapter flows logically and coherently.

If you have any questions or thoughts regarding this post, feel free to leave a comment below. Also, if you’re looking for one-on-one help with your discussion chapter (or thesis in general), consider booking a free consultation with one of our highly experienced Grad Coaches to discuss how we can help you.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

36 Comments

Thank you this is helpful!

This is very helpful to me… Thanks a lot for sharing this with us 😊

This has been very helpful indeed. Thank you.

This is actually really helpful, I just stumbled upon it. Very happy that I found it, thank you.

Me too! I was kinda lost on how to approach my discussion chapter. How helpful! Thanks a lot!

This is really good and explicit. Thanks

Thank you, this blog has been such a help.

Thank you. This is very helpful.

Dear sir/madame

Thanks a lot for this helpful blog. Really, it supported me in writing my discussion chapter while I was totally unaware about its structure and method of writing.

With regards

Syed Firoz Ahmad PhD, Research Scholar

I agree so much. This blog was god sent. It assisted me so much while I was totally clueless about the context and the know-how. Now I am fully aware of what I am to do and how I am to do it.

Thanks! This is helpful!

thanks alot for this informative website

Dear Sir/Madam,

Truly, your article was much benefited when i structured my discussion chapter.

Thank you very much!!!

This is helpful for me in writing my research discussion component. I have to copy this text on Microsoft word cause of my weakness that I cannot be able to read the text on screen a long time. So many thanks for this articles.

This was helpful

Thanks Jenna, well explained.

Thank you! This is super helpful.

Thanks very much. I have appreciated the six steps on writing the Discussion chapter which are (i) Restating the research problem and questions (ii) Summarising the key findings (iii) Interpreting the results linked to relating to previous results in positive and negative ways; explaining whay different or same and contribution to field of research and expalnation of findings (iv) Acknowledgeing limitations (v) Recommendations for implementation and future resaerch and finally (vi) Providing a conscluding summary

My two questions are: 1. On step 1 and 2 can it be the overall or you restate and sumamrise on each findings based on the reaerch question? 2. On 4 and 5 do you do the acknowlledgement , recommendations on each research finding or overall. This is not clear from your expalanattion.

Please respond.

This post is very useful. I’m wondering whether practical implications must be introduced in the Discussion section or in the Conclusion section?

Sigh, I never knew a 20 min video could have literally save my life like this. I found this at the right time!!!! Everything I need to know in one video thanks a mil ! OMGG and that 6 step!!!!!! was the cherry on top the cake!!!!!!!!!

Thanks alot.., I have gained much

This piece is very helpful on how to go about my discussion section. I can always recommend GradCoach research guides for colleagues.

Many thanks for this resource. It has been very helpful to me. I was finding it hard to even write the first sentence. Much appreciated.

Thanks so much. Very helpful to know what is included in the discussion section

this was a very helpful and useful information

This is very helpful. Very very helpful. Thanks for sharing this online!

it is very helpfull article, and i will recommend it to my fellow students. Thank you.

Superlative! More grease to your elbows.

Powerful, thank you for sharing.

Wow! Just wow! God bless the day I stumbled upon you guys’ YouTube videos! It’s been truly life changing and anxiety about my report that is due in less than a month has subsided significantly!

Simplified explanation. Well done.

The presentation is enlightening. Thank you very much.

Thanks for the support and guidance

This has been a great help to me and thank you do much

I second that “it is highly unlikely that a dissertation or thesis will scientifically prove something”; although, could you enlighten us on that comment and elaborate more please?

Sure, no problem.

Scientific proof is generally considered a very strong assertion that something is definitively and universally true. In most scientific disciplines, especially within the realms of natural and social sciences, absolute proof is very rare. Instead, researchers aim to provide evidence that supports or rejects hypotheses. This evidence increases or decreases the likelihood that a particular theory is correct, but it rarely proves something in the absolute sense.

Dissertations and theses, as substantial as they are, typically focus on exploring a specific question or problem within a larger field of study. They contribute to a broader conversation and body of knowledge. The aim is often to provide detailed insight, extend understanding, and suggest directions for further research rather than to offer definitive proof. These academic works are part of a cumulative process of knowledge building where each piece of research connects with others to gradually enhance our understanding of complex phenomena.

Furthermore, the rigorous nature of scientific inquiry involves continuous testing, validation, and potential refutation of ideas. What might be considered a “proof” at one point can later be challenged by new evidence or alternative interpretations. Therefore, the language of “proof” is cautiously used in academic circles to maintain scientific integrity and humility.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Qualitative Results and Discussion

- First Online: 20 August 2020

Cite this chapter

- Peijian Paul Sun 2

302 Accesses

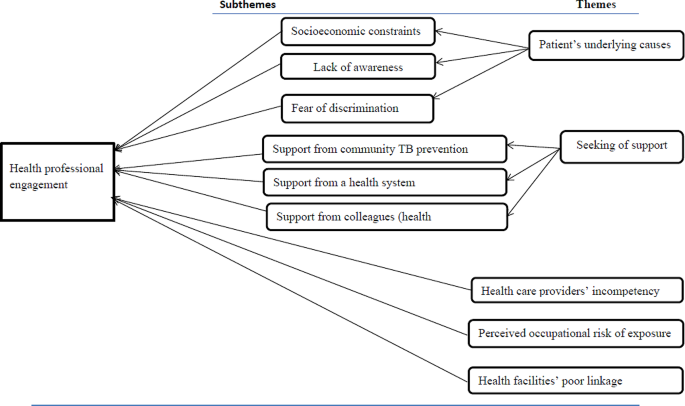

This chapter presents the results and discussion in line with the five research questions of the present study based on the qualitative data collected from the focus groups and semi-structured interviews. A total of 7 focus groups and 10 semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore the research questions from a more in-depth qualitative perspective. Two types of interviews were utilized in order to bring different lines of insights together to ensure that more profound and appropriate understandings of the research questions could be facilitated. This chapter starts with an introduction to the background information of the participants and the coding system. The qualitative findings in relation to each research question are presented sequentially followed by a summary and discussion.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Alrabai, Fakieh. 2015. The Influence of Teachers’ Anxiety-Reducing Strategies on Learners’ Foreign Language Anxiety. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 9 (2): 128–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2014.890203 .

Article Google Scholar

Amiryousefi, Mohammad. 2018. Willingness to Communicate, Interest, Motives to Communicate with the Instructor, and L2 Speaking: A Focus on the Role of Age and Gender. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 12 (3): 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2016.1170838 .

Armon-Lotem, Sharon, Susan Joffe, Hadar Abutbul-Oz, Carmit Altman, and Joel Walters. 2014. Language Exposure, Ethnolinguistic Identity and Attitudes in the Acquisition of Hebrew as a Second Language among Bilingual Preschool Children from Russian- and English-Speaking Backgrounds. In Input and Experience in Bilingual Development , edited by Theres Grüter and Johanne Paradis, 77–98. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Google Scholar

Bright, Peter, Julia Ouzia, and Roberto Filippi. 2019. Multilingualism and Metacognitive Processing. In The Handbook of the Neuroscience of Multilingualism , ed. John W. Schwieter, 355–371. Chichester, UK: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119387725.ch17 .

Caprara, Gian Vittorio, Michele Vecchione, Guido Alessandri, Maria Gerbino, and Claudio Barbaranelli. 2011. The Contribution of Personality Traits and Self-Efficacy Beliefs to Academic Achievement: A Longitudinal Study. British Journal of Educational Psychology 81 (1): 78–96. https://doi.org/10.1348/2044-8279.002004 .

Cenoz, Jasone, and Durk Gorter. 2019. Multilingualism, Translanguaging, and Minority Languages in SLA. The Modern Language Journal 103: 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12529 .

Clément, Richard, Susuan C. Baker, and Peter D. MacIntyre. 2003. Willingness to Communicate in a Second Language: The Effect of Context, Norms, and Vitality. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 22: 190–209.

Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2005. The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2009. The L2 Motivational Self System. In Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self , edited by Zoltán Dörnyei and Ema Ushioda, 9–42. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Effiong, Okon. 2016. Getting Them Speaking: Classroom Social Factors and Foreign Language Anxiety. TESOL Journal 7 (1): 132–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.194 .

Florack, Arnd, Anette Rohmann, Johanna Palcu, and Agostino Mazziotta. 2014. How Initial Cross-Group Friendships Prepare for Intercultural Communication: The Importance of Anxiety Reduction and Self-Confidence in Communication. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 43, Part B (0): 278–288. https://doi.org///dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.09.004 .

Ghorbani, Mohammad Reza, and Seyyed Ehsan Golparvar. 2019. Modeling the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status, Self-Initiated, Technology-Enhanced Language Learning, and Language Outcome. Computer Assisted Language Learning 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1585374 .

Hernández, Todd A. 2006. Integrative Motivation as a Predictor of Success in the Intermediate Foreign Language Classroom. Foreign Language Annals 22: 30–37.

Hu, Hsueh-chao Marcella, and Hossein Nassaji. 2014. Lexical Inferencing Strategies: The Case of Successful versus Less Successful Inferencers. System 45 (1): 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.04.004 .

Huang, Becky, Yung-Hsiang Shawn Chang, Luping Niu, and Mingxia Zhi. 2018. Examining the Effects of Socio-Economic Status and Language Input on Adolescent English Learners’ Speech Production Outcomes. System 73: 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.07.004 .

Hyland, Ken. 1993. Culture and Learning: A Study of the Learning Style Preferences of Japanese Students. RELC Journal 24 (2): 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368829302400204 .

Kang, Su-Ja. 2005. Dynamic Emergence of Situational Willingness to Communicate in a Second Language. System 33 (2): 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2004.10.004 .

Khajavy, Gholam Hassan, Peter D. MacIntyre, and Elyas Barabadi. 2018. Role of the Emotions and Classroom Environment in Willingness to Communicate: Applying Doubly Latent Multilevel Analysis in Second Language Acquisition Research. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 40 (3): 605–624. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263117000304 .

Kim, Tae-Young, and Yoon-Kyoung Kim. 2014. A Structural Model for Perceptual Learning Styles, the Ideal L2 Self, Motivated Behavior, and English Proficiency. System 46 (0): 14–27. https://doi.org///dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.07.007 .

Kırkgöz, Yasemin. 2018. Fostering Young Learners’ Listening and Speaking Skills. In The Routledge Handbook of Teaching English to Young Learners , ed. Sue Carton and Fiona Copland, 171–187. Routledge.

Krashen, Stephen D. 1982. Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition . Oxford, UK: Pergamon.

Liu, Meihua, and Wenhong Huang. 2011. An Exploration of Foreign Language Anxiety and English Learning Motivation. Education Research International 12: 1–8.

MacIntyre, Peter D. 2007. Willingness to Communicate in the Second Language: Understanding the Decision to Speak as a Volitional Process. The Modern Language Journal 91 (4): 564–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00623.x .

MacIntyre, Peter D., Zoltán Dörnyei, Richard Clément, and Kimberly A. Noels. 1998. Conceptualizing Willingness to Communicate in a L2: A Situational Model of L2 Confidence and Affiliation. The Modern Language Journal 82 (4): 545–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb05543.x .

Magogwe, Joel Mokuedi, and Rhonda Oliver. 2007. The Relationship Between Language Learning Strategies, Proficiency, Age and Self-Efficacy Beliefs: A Study of Language Learners in Botswana. System 35 (3): 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.01.003 .

Mahmoodzadeh, Masoud. 2012. Investigating Foreign Language Speaking Anxiety within the EFL Learner’s Interlanguage System: The Case of Iranian Learners. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 3 (3): 466–476. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.3.3.466-476 .

Minagawa, Harumi, Dallas Nesbitt, Masayoshi Ogino, Junji Kawai, and Ryoko de Burgh-Hirabe. 2019. Why I Am Studying Japanese: A National Survey Revealing the Voices of New Zealand Tertiary Students. Japanese Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2019.1678365 .

Nakatani, Yasuo. 2006. Developing an Oral Communication Strategy Inventory. The Modern Language Journal 90 (2): 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00390.x .

Nakatani, Yasuo, and Christine Goh. 2007. A Review of Oral Communication Strategies: Focus on Interactionist and Psycholinguistic Perspectives. In Language Learner Strategies: Thirty Years of Research and Practice , ed. Andrew D. Cohen and Ernesto Macaro, 207–227. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Naserieh, Farid, and Mohammad Reza Anani Sarab. 2013. Perceptual Learning Style Preferences among Iranian Graduate Students. System 41 (1): 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.01.018 .

Nicolson, Margaret, and Helga Adams. 2008. Travelling in Space and Encounters of the Third Kind: Distance Language Learner Negotiation of Speaking Activities. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 2 (2): 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501220802158859 .

Nomura, Kazuyuki, and Rui Yuan. 2019. Long-Term Motivations for L2 Learning: A Biographical Study from a Situated Learning Perspective. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40 (2): 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2018.1497041 .

Oxford, Rebecca L. 1990. Language Learning Strategies: What Every Teacher Should Know . Boston, MA: Heinle and Heinle.

Peacock, Matthew. 2001. Match or Mismatch? Learning Styles and Teaching Styles in EFL. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 11 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1473-4192.00001 .

Peng, Jian-E. 2019. The Roles of Multimodal Pedagogic Effects and Classroom Environment in Willingness to Communicate in English. System 82: 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.04.006 .

Phongsa, Manivone, Shaik Abdul Malik Mohamed Ismail, and Hui Min Low. 2018. Multilingual Effects on EFL Learning: A Comparison of Foreign Language Anxiety Experienced by Monolingual and Bilingual Tertiary Students in the Lao PDR. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 39 (3): 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2017.1371723 .

Psaltou-Joycey, Angeliki, and Zoe Gavriilidou. 2018. Language Learning Strategies of Greek EFL Primary and Secondary School Learners: How Individual Characteristics Affect Strategy Use. In Language Learning Strategies and Individual Learner Characteristics: Situating Strategy Use in Diverse Contexts , ed. Rebecca L. Oxford and Carmen M. Amerstorfer, 167–187. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2000. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist 55 (1): 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 .

Saito, Kazuya, Masatoshi Sato, and Roy Lyster. 2013. Oral Corrective Feedback in Second Language Classrooms. Language Teaching 46 (2): 1–40.

Sauer, Luzia, and Rod Ellis. 2019. The Social Lives of Adolescent Study Abroad Learners and Their L2 Development. The Modern Language Journal 103 (4): 739–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12589 .

Schauer, Gila A. 2006. The Development of ESL Learners’ Pragmatic Competence: A Longitudinal Investigation of Awareness and Production. In Pragmatics and Language Learning Volume 11 , edited by Kathleen Bardovi-Harlig, César Félix-Brasdefer, and Alwiya S. Omar, 135–64. Mānoa, HI: University of Hawaii Press.

Scovel, Thomas. 1978. The Effect of Affect on Foreign Language Learning: A Review of the Anxiety Research. Language Learning 28 (1): 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1978.tb00309.x .

Segalowitz, Norman. 2010. Cognitive Bases of Second Language Fluency . New York, NY: Routledge.

Shaikholeslami, Razieh, and Mohammad Khayyer. 2006. Intrinsic Motivation, Extrinsic Motivation, and Learning English as a Foreign Language. Psychological Reports 99 (3): 813–818.

Stewart, David W, and Prem N Shamdasani. 2015. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice . 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Taguchi, Naoko, Feng Xiao, and Shuai Li. 2016. Effects of Intercultural Competence and Social Contact on Speech Act Production in a Chinese Study Abroad Context. Modern Language Journal 100 (4): 775–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12349 .

Tarone, Elaine. 1981. Some Thoughts on the Notion of Communication Strategy. TESOL Quarterly 15 (3): 285–95. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586754 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Linguistics, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

Peijian Paul Sun

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Peijian Paul Sun .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Sun, P.P. (2020). Qualitative Results and Discussion. In: Chinese as a Second Language Multilinguals’ Speech Competence and Speech Performance. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6941-8_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-6941-8_7

Published : 20 August 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-15-6940-1

Online ISBN : 978-981-15-6941-8

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- LEARNING SKILLS

- Writing a Dissertation or Thesis

- Results and Discussion

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Learning Skills:

- A - Z List of Learning Skills

- What is Learning?

- Learning Approaches

- Learning Styles

- 8 Types of Learning Styles

- Understanding Your Preferences to Aid Learning

- Lifelong Learning

- Decisions to Make Before Applying to University

- Top Tips for Surviving Student Life

- Living Online: Education and Learning

- 8 Ways to Embrace Technology-Based Learning Approaches

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Critical Thinking and Fake News

- Understanding and Addressing Conspiracy Theories

- Critical Analysis

- Study Skills

- Exam Skills

- How to Write a Research Proposal

- Ethical Issues in Research

- Dissertation: The Introduction

- Researching and Writing a Literature Review

- Writing your Methodology

- Dissertation: Results and Discussion

- Dissertation: Conclusions and Extras

Writing Your Dissertation or Thesis eBook

Part of the Skills You Need Guide for Students .

- Research Methods

- Teaching, Coaching, Mentoring and Counselling

- Employability Skills for Graduates

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Writing your Dissertation: Results and Discussion

When writing a dissertation or thesis, the results and discussion sections can be both the most interesting as well as the most challenging sections to write.

You may choose to write these sections separately, or combine them into a single chapter, depending on your university’s guidelines and your own preferences.

There are advantages to both approaches.

Writing the results and discussion as separate sections allows you to focus first on what results you obtained and set out clearly what happened in your experiments and/or investigations without worrying about their implications.This can focus your mind on what the results actually show and help you to sort them in your head.

However, many people find it easier to combine the results with their implications as the two are closely connected.

Check your university’s requirements carefully before combining the results and discussions sections as some specify that they must be kept separate.

Results Section

The Results section should set out your key experimental results, including any statistical analysis and whether or not the results of these are significant.

You should cover any literature supporting your interpretation of significance. It does not have to include everything you did, particularly for a doctorate dissertation. However, for an undergraduate or master's thesis, you will probably find that you need to include most of your work.

You should write your results section in the past tense: you are describing what you have done in the past.

Every result included MUST have a method set out in the methods section. Check back to make sure that you have included all the relevant methods.

Conversely, every method should also have some results given so, if you choose to exclude certain experiments from the results, make sure that you remove mention of the method as well.

If you are unsure whether to include certain results, go back to your research questions and decide whether the results are relevant to them. It doesn’t matter whether they are supportive or not, it’s about relevance. If they are relevant, you should include them.

Having decided what to include, next decide what order to use. You could choose chronological, which should follow the methods, or in order from most to least important in the answering of your research questions, or by research question and/or hypothesis.

You also need to consider how best to present your results: tables, figures, graphs, or text. Try to use a variety of different methods of presentation, and consider your reader: 20 pages of dense tables are hard to understand, as are five pages of graphs, but a single table and well-chosen graph that illustrate your overall findings will make things much clearer.

Make sure that each table and figure has a number and a title. Number tables and figures in separate lists, but consecutively by the order in which you mention them in the text. If you have more than about two or three, it’s often helpful to provide lists of tables and figures alongside the table of contents at the start of your dissertation.

Summarise your results in the text, drawing on the figures and tables to illustrate your points.

The text and figures should be complementary, not repeat the same information. You should refer to every table or figure in the text. Any that you don’t feel the need to refer to can safely be moved to an appendix, or even removed.

Make sure that you including information about the size and direction of any changes, including percentage change if appropriate. Statistical tests should include details of p values or confidence intervals and limits.

While you don’t need to include all your primary evidence in this section, you should as a matter of good practice make it available in an appendix, to which you should refer at the relevant point.

For example:

Details of all the interview participants can be found in Appendix A, with transcripts of each interview in Appendix B.

You will, almost inevitably, find that you need to include some slight discussion of your results during this section. This discussion should evaluate the quality of the results and their reliability, but not stray too far into discussion of how far your results support your hypothesis and/or answer your research questions, as that is for the discussion section.

See our pages: Analysing Qualitative Data and Simple Statistical Analysis for more information on analysing your results.

Discussion Section

This section has four purposes, it should:

- Interpret and explain your results

- Answer your research question

- Justify your approach

- Critically evaluate your study

The discussion section therefore needs to review your findings in the context of the literature and the existing knowledge about the subject.

You also need to demonstrate that you understand the limitations of your research and the implications of your findings for policy and practice. This section should be written in the present tense.

The Discussion section needs to follow from your results and relate back to your literature review . Make sure that everything you discuss is covered in the results section.

Some universities require a separate section on recommendations for policy and practice and/or for future research, while others allow you to include this in your discussion, so check the guidelines carefully.

Starting the Task

Most people are likely to write this section best by preparing an outline, setting out the broad thrust of the argument, and how your results support it.

You may find techniques like mind mapping are helpful in making a first outline; check out our page: Creative Thinking for some ideas about how to think through your ideas. You should start by referring back to your research questions, discuss your results, then set them into the context of the literature, and then into broader theory.

This is likely to be one of the longest sections of your dissertation, and it’s a good idea to break it down into chunks with sub-headings to help your reader to navigate through the detail.

Fleshing Out the Detail

Once you have your outline in front of you, you can start to map out how your results fit into the outline.

This will help you to see whether your results are over-focused in one area, which is why writing up your research as you go along can be a helpful process. For each theme or area, you should discuss how the results help to answer your research question, and whether the results are consistent with your expectations and the literature.

The Importance of Understanding Differences

If your results are controversial and/or unexpected, you should set them fully in context and explain why you think that you obtained them.

Your explanations may include issues such as a non-representative sample for convenience purposes, a response rate skewed towards those with a particular experience, or your own involvement as a participant for sociological research.

You do not need to be apologetic about these, because you made a choice about them, which you should have justified in the methodology section. However, you do need to evaluate your own results against others’ findings, especially if they are different. A full understanding of the limitations of your research is part of a good discussion section.

At this stage, you may want to revisit your literature review, unless you submitted it as a separate submission earlier, and revise it to draw out those studies which have proven more relevant.

Conclude by summarising the implications of your findings in brief, and explain why they are important for researchers and in practice, and provide some suggestions for further work.

You may also wish to make some recommendations for practice. As before, this may be a separate section, or included in your discussion.

The results and discussion, including conclusion and recommendations, are probably the most substantial sections of your dissertation. Once completed, you can begin to relax slightly: you are on to the last stages of writing!

Continue to: Dissertation: Conclusion and Extras Writing your Methodology

See also: Writing a Literature Review Writing a Research Proposal Academic Referencing What Is the Importance of Using a Plagiarism Checker to Check Your Thesis?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

Published on 21 August 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 25 October 2022.

The discussion section is where you delve into the meaning, importance, and relevance of your results .

It should focus on explaining and evaluating what you found, showing how it relates to your literature review , and making an argument in support of your overall conclusion . It should not be a second results section .

There are different ways to write this section, but you can focus your writing around these key elements:

- Summary: A brief recap of your key results

- Interpretations: What do your results mean?

- Implications: Why do your results matter?

- Limitations: What can’t your results tell us?

- Recommendations: Avenues for further studies or analyses

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

What not to include in your discussion section, step 1: summarise your key findings, step 2: give your interpretations, step 3: discuss the implications, step 4: acknowledge the limitations, step 5: share your recommendations, discussion section example.

There are a few common mistakes to avoid when writing the discussion section of your paper.

- Don’t introduce new results: You should only discuss the data that you have already reported in your results section .

- Don’t make inflated claims: Avoid overinterpretation and speculation that isn’t directly supported by your data.

- Don’t undermine your research: The discussion of limitations should aim to strengthen your credibility, not emphasise weaknesses or failures.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Start this section by reiterating your research problem and concisely summarising your major findings. Don’t just repeat all the data you have already reported – aim for a clear statement of the overall result that directly answers your main research question . This should be no more than one paragraph.

Many students struggle with the differences between a discussion section and a results section . The crux of the matter is that your results sections should present your results, and your discussion section should subjectively evaluate them. Try not to blend elements of these two sections, in order to keep your paper sharp.

- The results indicate that …

- The study demonstrates a correlation between …

- This analysis supports the theory that …

- The data suggest that …

The meaning of your results may seem obvious to you, but it’s important to spell out their significance for your reader, showing exactly how they answer your research question.

The form of your interpretations will depend on the type of research, but some typical approaches to interpreting the data include:

- Identifying correlations , patterns, and relationships among the data

- Discussing whether the results met your expectations or supported your hypotheses

- Contextualising your findings within previous research and theory

- Explaining unexpected results and evaluating their significance

- Considering possible alternative explanations and making an argument for your position

You can organise your discussion around key themes, hypotheses, or research questions, following the same structure as your results section. Alternatively, you can also begin by highlighting the most significant or unexpected results.

- In line with the hypothesis …

- Contrary to the hypothesised association …

- The results contradict the claims of Smith (2007) that …

- The results might suggest that x . However, based on the findings of similar studies, a more plausible explanation is x .

As well as giving your own interpretations, make sure to relate your results back to the scholarly work that you surveyed in the literature review . The discussion should show how your findings fit with existing knowledge, what new insights they contribute, and what consequences they have for theory or practice.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Do your results support or challenge existing theories? If they support existing theories, what new information do they contribute? If they challenge existing theories, why do you think that is?

- Are there any practical implications?

Your overall aim is to show the reader exactly what your research has contributed, and why they should care.

- These results build on existing evidence of …

- The results do not fit with the theory that …

- The experiment provides a new insight into the relationship between …

- These results should be taken into account when considering how to …

- The data contribute a clearer understanding of …

- While previous research has focused on x , these results demonstrate that y .

Even the best research has its limitations. Acknowledging these is important to demonstrate your credibility. Limitations aren’t about listing your errors, but about providing an accurate picture of what can and cannot be concluded from your study.

Limitations might be due to your overall research design, specific methodological choices , or unanticipated obstacles that emerged during your research process.

Here are a few common possibilities:

- If your sample size was small or limited to a specific group of people, explain how generalisability is limited.

- If you encountered problems when gathering or analysing data, explain how these influenced the results.

- If there are potential confounding variables that you were unable to control, acknowledge the effect these may have had.

After noting the limitations, you can reiterate why the results are nonetheless valid for the purpose of answering your research question.

- The generalisability of the results is limited by …

- The reliability of these data is impacted by …

- Due to the lack of data on x , the results cannot confirm …

- The methodological choices were constrained by …

- It is beyond the scope of this study to …

Based on the discussion of your results, you can make recommendations for practical implementation or further research. Sometimes, the recommendations are saved for the conclusion .

Suggestions for further research can lead directly from the limitations. Don’t just state that more studies should be done – give concrete ideas for how future work can build on areas that your own research was unable to address.

- Further research is needed to establish …

- Future studies should take into account …

- Avenues for future research include …

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 25). How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/discussion/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a results section | tips & examples, research paper appendix | example & templates, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction.

- Open access

- Published: 29 April 2024

Pathways and identity: toward qualitative research careers in child and adolescent psychiatry

- Andrés Martin 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Madeline DiGiovanni 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Amber Acquaye 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Matthew Ponticiello 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Débora Tseng Chou 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Emilio Abelama Neto 2 , 3 , 4 ,

- Alexandre Michel 2 , 3 , 5 ,

- Jordan Sibeoni 2 , 3 , 5 ,

- Marie-Aude Piot 2 , 3 , 5 ,

- Michel Spodenkiewicz 2 , 3 , 6 &

- Laelia Benoit 1 , 2 , 3

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health volume 18 , Article number: 49 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

11 Accesses

Metrics details

Qualitative research methods are based on the analysis of words rather than numbers; they encourage self-reflection on the investigator’s part; they are attuned to social interaction and nuance; and they incorporate their subjects’ thoughts and feelings as primary sources. Despite appearing well suited for research in child and adolescent psychiatry (CAP), qualitative methods have had relatively minor uptake in the discipline. We conducted a qualitative study of CAPs involved in qualitative research to learn about these investigators’ lived experiences, and to identify modifiable factors to promote qualitative methods within the field of youth mental health.

We conducted individual, semi-structured 1-h long interviews through Zoom. Using purposive sample, we selected 23 participants drawn from the US (n = 12) and from France (n = 11), and equally divided in each country across seniority level. All participants were current or aspiring CAPs and had published at least one peer-reviewed qualitative article. Ten participants were women (44%). We recorded all interviews digitally and transcribed them for analysis. We coded the transcripts according to the principles of thematic analysis and approached data analysis, interpretation, and conceptualization informed by an interpersonal phenomenological analysis (IPA) framework.

Through iterative thematic analysis we developed a conceptual model consisting of three domains: (1) Becoming a qualitativist: embracing a different way of knowing (in turn divided into the three themes of priming factors/personal fit; discovering qualitative research; and transitioning in); (2) Being a qualitativist: immersing oneself in a different kind of research (in turn divided into quality: doing qualitative research well; and community: mentors, mentees, and teams); and (3) Nurturing : toward a higher quality future in CAP (in turn divided into current state of qualitative methods in CAP; and advocating for qualitative methods in CAP). For each domain, we go on to propose specific strategies to enhance entry into qualitative careers and research in CAP: (1) Becoming: personalizing the investigator’s research focus; balancing inward and outward views; and leveraging practical advantages; (2) Being: seeking epistemological flexibility; moving beyond bibliometrics; and the potential and risks of mixing methods; and (3) Nurturing : invigorating a quality pipeline; and building communities.

Conclusions

We have identified factors that can support or impede entry into qualitative research among CAPs. Based on these modifiable findings, we propose possible solutions to enhance entry into qualitative methods in CAP ( pathways ), and to foster longer-term commitment to this type of research ( identity ).

…we must reckon that numbers can say only so much, and that we need to better listen and better represent the voices of those under our care, especially of those who have been unheard or disenfranchised for far too long. We believe that less quantity and more quality can help us meet those aspirations [ 1 ], p.3.

Qualitative methods of research favor the analysis of words over that of numbers, which are in turn the main focus of quantitative approaches. With its preference for thoughts, ideas, feelings, and other aspects of internal life, qualitative inquiry is particularly well suited for psychiatry [ 2 ]. Moreover, with child and adolescent psychiatry’s (CAP’s) interest in exploring the interactions between groups of individuals and their role as interconnected social actors, qualitative methods are especially well suited for the discipline. The link between CAP as a subject matter and qualitative methods as a favored research approach would appear to be a natural one.