We've updated our Privacy Policy to make it clearer how we use your personal data. We use cookies to provide you with a better experience. You can read our Cookie Policy here.

Applied Sciences

Stay up to date on the topics that matter to you

What Role Does Beauty Have in the World of Science?

What is meant by “beauty” in science, how it can be studied and what are the implications of such research.

Complete the form below to unlock access to ALL audio articles.

Beauty might not necessarily be the first word that comes to mind when we think about research, but as Dr. Brandon Vaidyanathan’s work highlights, it plays a crucial role in the flourishing of scientists.

Vaidyanathan is an associate professor, chair of the department of sociology and director of the Institutional Flourishing Lab at The Catholic University of America. His research examines the cultural dimensions of religious, commercial and scientific institutions. Currently, Vaidyanathan leads Work and Well-Being in Science , the largest cross-national study investigating factors that affect the wellbeing of scientists.

While there isn’t an official term that describes this research field just yet, Vaidyanathan feels inclined to call it “aesthetics in science”: “There is a very recent and growing body of work in philosophy and sociology that looks at how aesthetic factors (e.g., beauty, awe, wonder and other aesthetic emotions) shape scientists and the practice of science,” he says.

In this interview with Technology Networks , Vaidyanathan describes what is meant by “beauty” in science, how it can be studied and the implications of such research.

Molly Campbell (MC): Can you talk about how you became interested in this research field?

Brandon Vaidyanathan (BV): I was drawn to research this area because in qualitative research interviews with scientists for a previous project, our team was surprised to hear them regularly bring up “beauty” as a key motivating factor. There is also new research that is raising concerns about how the pursuit of “mathematical beauty” in physics can be a source of bias that is derailing scientific progress.

MC: Can you talk about the current research landscape exploring the role of beauty in science, and what actionable insights it offers?

BV: My project Work and Well-Being in Science is the largest international study on the aesthetics of science. We surveyed several thousand scientists in 4 countries and also conducted 200+ in-depth interviews.

One key insight is that aesthetic factors are a major source of motivation for scientists to pursue their careers in the first place.

Our team finds that most scientists see science as an aesthetic quest – a quest for the “beauty of understanding,” which is the pleasure gained from discovering the hidden order or inner logic underlying phenomena they study.

We also find that aesthetic experience is very strongly associated with well-being among scientists. This is especially important in light of considerable research pointing to a mental health crisis in science. Our work underscores the need to preserve the intrinsic motivations and joys of doing science and address the obstacles to it (such as institutional pressures and toxic leadership) that scientists face.

Read Vaidyanathan’s published work on exploring aesthetics in science:

- Aesthetic experiences and flourishing in science: A four-country study

- Individual differences in scientists’ aesthetic disposition, aesthetic experiences, and aesthetic sensitivity in scientific work

- Beauty in biology: An empirical assessment

Besides this project, the work of Cambridge philosopher Dr. Milena Ivanova highlights the importance of aesthetics in scientific experiments in her books and articles. Prominent scientists such as Nobel Prize winner Frank Wilczek and Oxford biologist Richard Dawkins have written books about aesthetics in science ( A Beautiful Question: Finding Nature's Deep Design and Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder ). Sabine Hossenfelder published a bestselling book on the negative aspects of mathematical beauty in physics.

MC: Can it be challenging to explore the role of beauty in science?

BV: The challenge to survey research in this area is that it is increasingly difficult to get a high response rate for surveys – even with financial incentives in place, most people don’t want to take a survey, and mail servers often filter out survey invitations as spam. It is also difficult to get elite populations (e.g., scientists) to participate in research. We think increased dissemination of our results and awareness of our findings can help motivate scientists to continue participating in research so we can learn how to improve well-being in the scientific community.

MC: Are there any specific research methodologies that you view as integral to the progression of this field?

BV: So far the work that has been done is either philosophical, historical or sociological (through interviews and surveys). Longitudinal survey work would be important in order to assess causal mechanisms. More experimental and even neuropsychological work could also benefit this field in helping us understand how aesthetic experiences affect scientists and their relevance to scientific practice.

Dr. Brandon Vaidyanathan was speaking with Molly Campbell, Senior Science Writer for Technology Networks.

About the interviewee:

Dr. Brandon Vaidyanathan is associate professor, chair of the Department of Sociology and director of the Institutional Flourishing Lab at The Catholic University of America. He holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in business administration from St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia and HEC Montreal respectively, and a PhD in sociology from the University of Notre Dame. Dr. Vaidyanathan's research examines the cultural dimensions of religious, commercial and scientific institutions, and has been widely published in peer-reviewed journals. His current research examines the role of beauty in science and other domains of work.

February 2, 2021

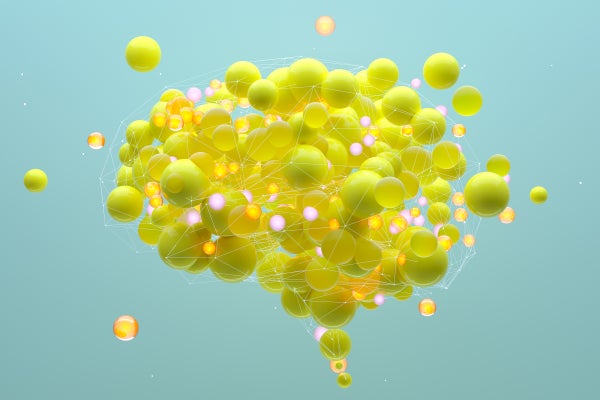

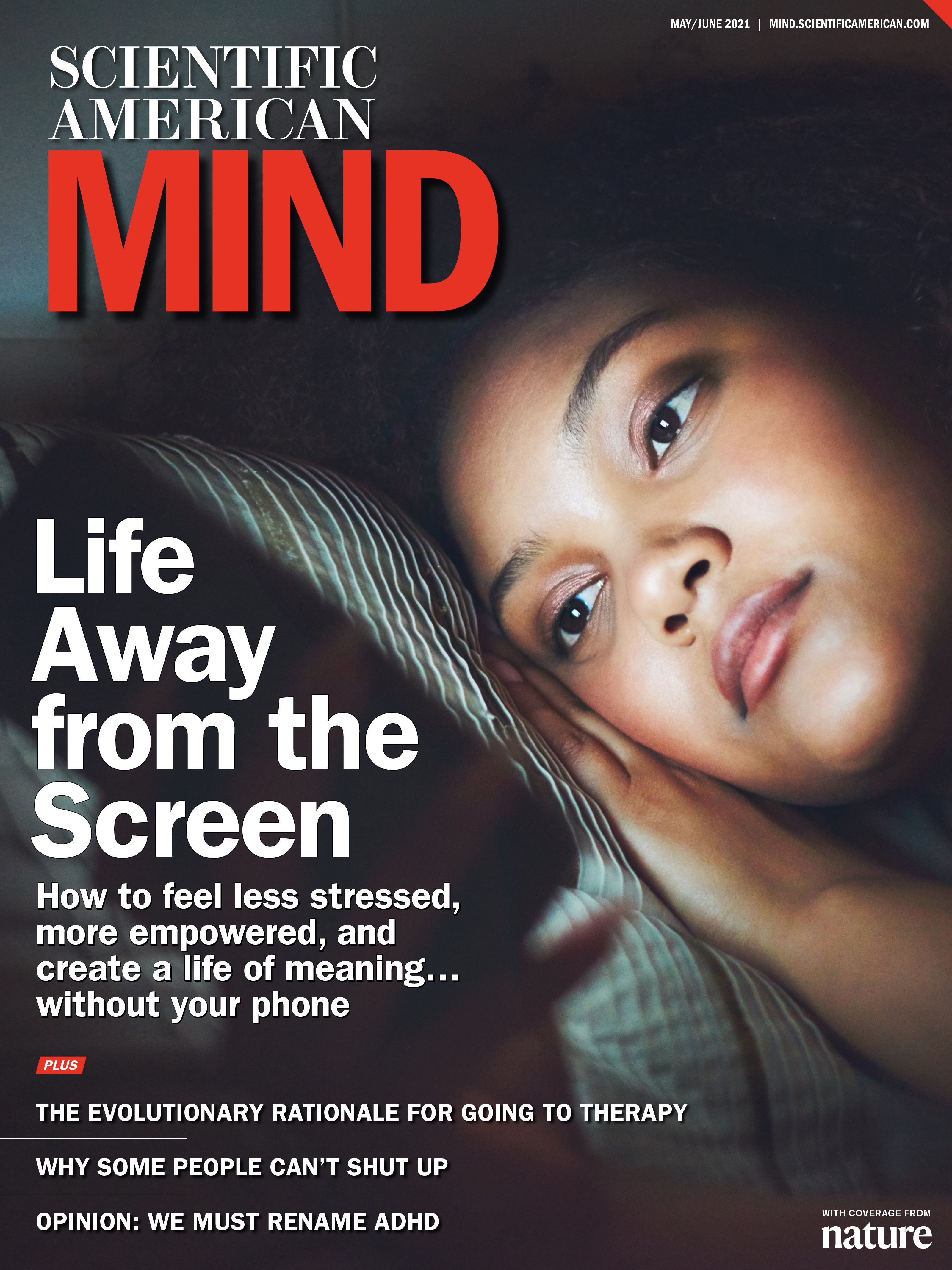

How the Brain Responds to Beauty

Scientists search for the neural basis of an enigmatic experience

By Jason Castro

Andriy Onufriyenko Getty Images

Pursued by poets and artists alike, beauty is ever elusive. We seek it in nature, art and philosophy but also in our phones and furniture. We value it beyond reason, look to surround ourselves with it and will even lose ourselves in pursuit of it. Our world is defined by it, and yet we struggle to ever define it. As philosopher George Santayana observed in his 1896 book The Sense of Beauty , there is within us “a very radical and wide-spread tendency to observe beauty, and to value it.”

Philosophers such as Santayana have tried for centuries to understand beauty, but perhaps scientists are now ready to try their hand as well. And while science cannot yet tell us what beauty is, perhaps it can tell us where it is—or where it isn’t. In a recent study, a team of researchers from Tsinghua University in Beijing and their colleagues examined the origin of beauty and argued that it is as enigmatic in our brain as it is in the real world.

There is no shortage of theories about what makes an object aesthetically pleasing. Ideas about proportion, harmony, symmetry, order, complexity and balance have all been studied by psychologists in great depth. The theories go as far back as 1876—in the early days of experimental psychology—when German psychologist Gustav Fechner provided evidence that people prefer rectangles with sides in proportion to the golden ratio (if you’re curious, that ratio is about 1.6:1).

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

At the time, Fechner was immersed in the project of “outer psychophysics ”—the search for mathematical relationships between stimuli and their resultant percepts. What both fascinated and eluded him, however, was the much more difficult pursuit of “inner psychophysics”—relating the states of the nervous system to the subjective experiences that accompany them. Despite his experiments with the golden ratio, Fechner continued to believe that beauty was, to a large degree, in the brain of the beholder.

So what part of our brain responds to beauty? The answer depends on whether we see beauty as a single category at all. Brain scientists who favor the idea of such a “beauty center” have hypothesized that it may live in the orbitofrontal cortex, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex or the insula. If this theory prevails, then beauty really could be traced back to a single region of the brain. We would experience beauty in the same way whether we were listening to Franz Schubert song, staring at a Diego Velázquez painting or seeing a doe denning under the starlight.

If the idea of a beauty center is correct, then this would be a considerable victory for theory of functional localization. Under this view—which is both widely held and widely contested—much of what the brain does is the result of highly specialized modules. To simplify the idea a bit, we could imagine assigning Post-it notes to areas of the brain with job descriptions underneath: “pleasure center,” “memory center,” “visual center,” “beauty center.” While some version of this theory is likely true, it’s certainly not the case that any kind of mental state you can describe or intuit is cleanly localized somewhere in the brain. Still, there is excellent evidence, for example, that specific parts of the visual cortex have an exquisite selectivity for motion. Other, nonoverlapping parts are quite clearly activated only by faces. But for every careful study that finds compellingly localized brain function, there are many more that have failed to match a region with a concrete job description.

Rather than potentially add to the mix of inconclusive, underpowered studies about whether the perception of beauty is localized to some specific brain area in their recent investigation, the Tsinghua University researchers opted to do a meta-analysis. They pooled data from many already published studies to see if a consistent result emerged. The team first combed the literature for all brain-imaging studies that investigated people’s neural responses to visual art and faces and that also asked them to report on whether what they saw was beautiful or not. After reviewing the different studies, the researchers were left with data from 49 studies in total, representing experiments from 982 participants. The faces and visual art were taken to be different kinds of beautiful things, and this allowed for a conceptually straightforward test of the beauty center hypothesis. If transcendent, capital-B beauty was really something common to faces and visual art and was processed in the capital-B-beauty region of the brain, then this area should show up across studies, regardless of the specific thing being seen as beautiful. If no such region was found, then faces and visual art would more likely be, as parents say of their children, each beautiful in its own way.

The technique used to analyze the pooled data is known as activation likelihood estimation (ALE). Underneath a bit of statistical formality, it is an intuitive idea: we have more trust in things that have more votes. ALE takes each of the 49 studies to be a fuzzy, error-prone report of a specific location in the brain—roughly speaking, the particular spot that “lit up” when the experiment was conducted, together with a surrounding cloud of uncertainty. The size of this cloud of uncertainty was large if the study had few participants and small if there were many of them, thus modeling the confidence that comes from collecting more data. These 49 points and their clouds were then all merged into a composite statistical map, giving an integrated picture of brain activation across many studies and a means for saying how confident we are in the consensus across experiments. If a single small region was glowing red-hot after the merge (all clouds were small and close together), that would mean it was reliably activated across all the different studies.

Performing this analysis, the research team found that beautiful visual art and beautiful faces each reliably elicited activity in well-defined brain regions. No surprises here: it is hoped that the brain is doing something when you’re looking at a visual stimulus. The regions were almost completely nonoverlapping, however, which challenged the idea that a common beauty center was activated. If we take this at face value, then the beauty of a face is not the same as the beauty of a painting. Beauty is plural, diverse, embedded in the particulars of its medium.

It’s possible the hypothesized beauty center actually does exist and just failed to show up for a variety of methodological reasons. And to be sure, this one analysis hardly settles a question as profound and difficult as this one. Yet that raises an important point: What are we trying to accomplish here? Why do we care if beauty is one thing in the brain or 10? Would the latter make beauty 10 times more marvelous or diminish it 10-fold? More pertinent: How do we understand beauty differently if we know where to point to it in the brain? It will probably be many years, perhaps even generations, before we have something like a neuroscience of aesthetics that both physiologists and humanists will find truly compelling. But we can be sure that beauty’s seductions will keep calling us back to this messy, intriguing and unmapped place in the interim.

Jason Castro is an associate professor and chair of the neuroscience program at Bates College.

You are here

The meaning of beauty in exact natural science.

Lecture delivered to the Bayerische Akademie der Schönen Künste

When a representative of natural science has to address a session of the Academy of the Fine Arts, he can hardly dare to express opinions about the topic art. For the arts are clearly remote from his own area of work. But perhaps he is entitled to take up the problem of beauty. For the adjective 'beautiful' is here indeed used to characterize the arts, but the realm of beauty reaches certainly far beyond its sphere of action. It surely encompasses also other areas of spiritual life – and the beauty of nature finds itself reflected also in the beauty of natural science. Perhaps it is good if we at first – without any attempt at a philosophical analysis of the concept 'beauty' – simply inquire where, in the area of the exact sciences, we can meet with beauty itself. Here I may perhaps begin with a personal experience. When I, as a young boy, was attending the lowest classes of the Max-Gymnasium in Munich, I took a great interest in numbers. It gave me pleasure to know their properties – for instance, to find out whether they were prime numbers or not, and to see whether they could be represented as sums of squares, or finally to prove that there had to be infinitely many prime numbers. Since my father found my knowledge of Latin much more important than my interest in numbers, he once brought to me from the State Library a treatise written in Latin by the mathematician Kronecker. In it the properties of numbers were put in relation to the geometric problem which consists in dividing a circle into a number of equal parts. I do not know how my father hit upon such a research from the middle of the past century. But the study of Kronecker's treatise made a profound impression on me. For I perceived it immediately as a thing of beauty that one could, from the problem of the division of the circle – whose simplest cases were already known to us from the classroom – come to learn something about the completely different questions of the elementary theory of numbers. In the distant background the question even presented itself briefly whether there are integers and geometric forms – that is, whether they exist outside the spirit of man, or whether they are just constructed by this spirit as instruments for the understanding of the world. But at that time I was not yet in a position to think of such problems. Only the impression of something very beautiful was quite direct, did not need any foundation or explanation. But what was beautiful here? Already in antiquity there were two definitions of beauty which stood in a certain opposition to each other. The controversy between these two definitions played a great role especially in the Renaissance. One of them designates beauty as the right concordance of the parts with each other and with the whole. The other, which goes back to Plotinus, without any reference to parts designates beauty as the translucence of the eternal splendor of the 'One' through the material phenomenon. In connection with the mathematical example we will have at first to side with the first definition. The parts are here the properties of the integers and the laws of geometric constructions. The whole is obviously the mathematical system of axioms which stands behind them, to which both arithmetic and Euclidean geometry belong. Namely, it is the great interconnection which is guaranteed by the freedom from contradiction of the axiomatic system. We realize that the single parts fit together, that they belong to this whole really as parts – and we, without any reflection, perceive as beautiful the compactness and simplicity of this axiomatic system. Beauty has therefore something to do with the age-old problem of the 'One' and the 'Many' which – once in strict connection with the problem of 'Being' and 'Becoming'– stood at the center of the early Greek philosophy.

Since also the roots of exact natural science lie precisely in this area, it will be good to sketch the thought currents of that early epoch in rough outline. At the start of Greek philosophy there is the question of the fundamental principle – of the 'One' – out of which the manifold multiplicity of the phenomena can be made understandable. Although it may sound strange to us, the well-known answer by Thales – "Water is the material principle of all things"– contains, as Nietzsche has pointed out, three basic philosophical challenges that became important in the subsequent development. They are, first, that man should seek such a unitary fundamental principle; second, that the answer could be given only rationally, that is, without reference to a myth; and finally, third, that the material aspect of the world had here a decisive role to play. Behind these challenges stands naturally the tacit admission that understanding can always just mean one thing: to become aware of interconnections, i.e. unitary features, characteristics of relatedness, in the multiplicity. If, however, there is such a unitary principle of all things, then is one unavoidably driven to the question – and this is the next step in this conceptual development – as to how change can be made understandable out of it. The difficulty is particularly to be seen in the famous paradox of Parmenides. Only being is, non-being is not. But, if only being is, then there can be nothing besides being-something, that is, that would dismember this being, that would bring about changes. Therefore being should be thought of as eternal, uniform, temporally and spatially unlimited. The changes that we experience, then, could only be an appearance. Greek thought could not stand still long because of this paradox. The eternal succession of phenomena was immediately given, and people had to explain it. In the attempt to overcome this difficulty, various directions were tried by various philosophers. One development led to the atomic doctrine of Democritos. We want to cast just a very quick look upon it. Besides being, also non-being can be there as possibility, namely as possibility for motion and form – that is, as empty space. Being is repeatable, and thus we come to the view of atoms in empty space – the view which later became so endlessly fruitful as a foundation of natural science. But of this development we are not going to speak here any further. Rather the other development will be more precisely discussed: the one which led to the ideas of Plato and which brings us directly to the problem of beauty. This development begins in the school of Pythagoras. In it must the idea have arisen that mathematics – mathematical orderliness – was the fundamental principle out of which the multiplicity of phenomena could be made understandable. About Pythagoras himself we know little. It seems that his school was somehow like a religious sect. What can be traced back to Pythagoras with certainty is only the doctrine of metempsychosis and the establishment of religious-ethical prescriptions and prohibitions. In this school, however, the occupation with music and mathematics played an important part – and this was the decisive element for future time. In this connection Pythagoras must have made the famous discovery that equally tense vibrating strings produce a harmonic sound if their lengths stand to each other in a simple rational numeric relation. Mathematical structure, namely rational numeric relation as source of harmony – that was certainly one of the most pregnant discoveries that were ever made in the history of mankind. The harmonic resonance of two strings produces a beautiful sound. The human ear perceives the dissonance that originates from the disquiet of oscillations as disturbing – but it perceives the quiet of harmony, the consonance, as beautiful. The mathematical relation was therefore also the source of beauty. Beauty is – so reads one of the ancient definitions – the right concordance of the parts with each other and with the whole. The parts are here the individual tunes, the whole is the harmonic sound. Mathematical relation can then join together into one whole two originally independent parts and thus bring forth something beautiful. It was this discovery which, in the doctrine of the Pythagoreans, produced a breakthrough toward entirely new forms of thought. It led to the view that the principle of all being was no longer seen as a sensible stuff – as water was for Thales – but as an ideal form. Thereby was a fundamental thought expressed which later constituted the foundation of all exact natural sciences. Aristotle reports in his Metaphysics about the Pythagoreans: "They busied themselves at first with mathematics, promoted it and, being reared in it, considered mathematical principles as the principles of everything that exists. And seeing in the numbers the properties and foundations of harmony ... they conceived the elements of numbers as the elements of all things, and the entire universe as harmony and number.'' The understanding of the manifold multiplicity of phenomena, then, should come about through our recognizing, in it, unitary formal principles which can be expressed in the language of mathematics. Thus also a strict interconnection is established between intelligibility and beauty. For, if beauty is known as the concordance of the parts with each other and with the whole and if, on the other hand, all understanding can first come about through this formal interconnection – then is the experience of beauty almost identical with the experience of understanding or, at least, guessing such an interconnection.

The next step in this development was undertaken, as is well known, by Plato through the formulation of his doctrine of ideas. Plato contrasts the perfect mathematical forms with the imperfect entities of the sensible world – for instance, the imperfectly circular orbits of the stars with the perfect, mathematically defined circle. Material things are the imitations, the shadows of ideal real structures. And thus – we would be tempted to continue – these ideal structures are real because and insofar as they are realizing in material events. Plato, then, distinguishes here with complete clarity a bodily being which is accessible to the senses from a purely ideal being which cannot be grasped through the senses but only through spiritual acts. However, this ideal being stands by no means in need of human thinking, so as to be brought about by it. It is, on the contrary, the authentic being after which both the corporeal world and the human thinking are patterned. The grasping of the ideas by the human spirit is – as already their name says – more of an artistic contemplation, a half conscious guessing than a rational knowing. It is the reminiscence of forms which have engrafted into this soul already before its earthly existence. The central idea is that of beauty and goodness, in which the divinity becomes visible, and at whose sight the wings of the soul grow. In one passage of the Phaedros is the thought expressed: “The soul is frightened, it shudders at the sight of beauty for it feels that something is conjured up in it which has not come to it from the outside through the senses, but has always been present in it, in a profoundly unconscious area”.

But let us return again to the understanding and therefore to natural science. The manifold multiplicity of phenomena can be understood – say Plato and Pythagoras – because and insofar as here there are underlying unitary formal principles which are amenable to a mathematical representation. With that, the entire program of modern exact natural science is already anticipated. But it could not be carried out in antiquity because the empirical knowledge of details in natural events was largely lacking. The first attempt to come to grips with such details was undertaken, as is well known, by the philosophy of Aristotle. But, given the boundless fulness which at first sight offered itself to the observer of nature, and given the total lack of any viewpoints which could have made orderliness recognizable, the unitary formal principles which had been sought by Pythagoras and Plato had now to step back before the description of details. Thus already at that time comes to the fore the opposition which has lasted until now, for instance in the discussion between experimental and theoretical physics. It is the opposition between the experimentalist who, through accurate and conscientious spade work, creates the presuppositions for the understanding of nature and the theoretician who devises mathematical schemes by which he tries to order nature and thus to understand it. These mathematical schemes prove themselves to be the true ideas which underlie natural events – and this not only because they represent correctly the data of experience but above all because of their simplicity and beauty. Already Aristotle, as an experimentalist spoke critically of the Pythagoreans who, as he put it: “did not search for explanations and theories on the basis of facts, but rather, on the basis of certain theories and pet opinions, strained the facts and – so to speak – played themselves up as co-ordinators of the universe." Looking back at the history of exact natural science one can perhaps establish that the correct representation of natural phenomena developed precisely out of the tension between these two opposite conceptions. Pure mathematical speculation is sterile because it cannot find its way back from the fulness of possible forms to the very few forms according to which nature is really constructed. And pure experimentation is sterile because finally it is smothered by endless tabulations without intrinsic interconnection. Only from the tension that arises out of the interplay between the fulness of facts and the possibly suitable mathematical forms can decisive advances come.

But this tension could not be taken up in antiquity and therefore the way to knowledge became for long time separated from the way to beauty. The meaning of beauty for the understanding of nature became clearly visible again only when people, at the beginning of modern times, succeeded in reverting from Aristotle to Plato. Only through this turn did the entire fruitfulness of the mental attitude introduced by Pythagoras and Plato reveal itself. Already the famous investigations of the fall – which Galilei did probably not carry out at the Leaning Tower of Pisa – indicate that most clearly. Galilei begins with accurate observations without taking into account the authority of Aristotle. Rather he tries, following the doctrines of Pythagoras and Plato, to find mathematical forms that correspond to the empirically obtained facts, and thus arrives at his laws of the fall. But in order to recognize the beauty of mathematical forms in the phenomena, he must – and this is a decisive point – idealize the facts or, as Aristotle had reproachfully put it, strain them. Aristotle had taught that all moving bodies come finally to rest if there is no action by external forces – and that was the common experience. Galilei asserts on the contrary that bodies without external forces persevere in the state of uniform motion. Galilei could dare to strain facts this way because he could point out that moving bodies are always exposed to the resistance of friction – and so motion lasts in actual fact the longer, the better the friction forces can be eliminated. Through this straining of facts – this idealization – he gained a simple mathematical law: and this was beginning of the modern exact natural science.

A few years later Kepler succeeded in discovering – in the results of Tycho Brahe's very precise observations of planetary orbits – new mathematical forms. Thus he formulated his famous three Keplerian laws. How close Kepler felt in these discoveries to the old conceptions of Pythagoras, and how much the beauty of the interconnections led him to their formulation – this comes to the fore already in the fact that he compared the revolutions of planets around the sun to the vibrations of a string, and spoke of a harmonious resonance of the various planetary orbits: the harmony of the spheres. Finally, at the end of his work on the harmony of the world he burst into the cry of joy: "I thank you, God our Creator, for you have made me gaze upon the beauty of your creative work." Kepler was intimately seized by the fact that he had here come across a quite central interconnection: one not thougt out by man, and one whose first cognition had been reserved for him – an interconnection of highest beauty.

A few decades later Isaac Newton in England brought this interconnection completely to light and described it in detail in his great work Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica . With that was the path of exact natural science marked out for about two centuries. But, is it not knowledge alone that is in question here – or also beauty? And if beauty, too, is in question what role has it played in the discovery of interconnections? Let us recall again the ancient definition: "Beauty is the right concordance of the parts with each other and with the whole." That this criterion applies in the highest measure to a construction like Newtonian mechanics, this hardly needs to be explained. The parts – they are the individual mechanical processes: those which we isolate accurately by means of apparatus just as those which unfold inextricably before us in the manifold play of phenomena. And the whole is precisely the unitary formal principle into which all of these processes fit the one which has been mathematically laid down by Newton in a simple system of axioms. Unitariness and simplicity are, to be sure, not exactly the same. But the fact that in such a theory the many are placed over against the one, that in the one the many are unified – this leads by itself to the consequence that the theory is simultaneously perceived by us as simple and beautiful. The meaning of beauty for the finding out of truth has been recognized and stressed at all times. The Latin motto, "simplex sigillum veri" , "Simplicity is the seal of truth" stands in large letters in the physics auditorium of the University of Gottingen as a warning for those who want to discover something new. And the other Latin motto "pulchritudo splendor veritatis" , "beauty is the splendor of truth" can also be so interpreted that the researcher first knows truth from his splendor shining forth. Still twice in the history of exact natural science has this shining-up of the great interconnection become the decisive signal for significant progress. I am thinking here of two events in the physics of our century: the rise of the theory of relativity and that of the quantum theory. In both cases, after yearlong unsuccessful striving for understanding, a bewildering abundance of details was almost suddenly ordered. This took place when an interconnection emerged which, thought largely unvisualizable, was finally simple in its substance. It convinced through its compactness and abstract beauty – it convinced all those who can understand and speak such an abstract language. But we do not want to follow any further the evolution of history. Rather we would like to ask quite directly: What shines up here? How does it happen that in this shining-up of beauty in exact natural science the great interconnection becomes cognoscible –even before it can be understood in detail, before it can be demonstrated rationally? What does the shining force consist in and what does it accomplish in the further course of science?

Perhaps at this point one should begin by recalling a phenomenon which can be called the unfolding of abstract structures. It can be clarified through the example of the theory of numbers which has already been mentioned at the beginning, but one can also point to similar processes in the development of art. For the mathematical foundation of arithmetic – the theory of numbers – a few simple axioms suffice which, properly speaking, just define exactly what counting means. But, with these few axioms, is in fact already laid down the entire fulness of forms that only in the course of a long history have entered the consciousness of mathematicians: the doctrine of prime numbers, that of square rests, that of the congruence of numbers, etc. One can say that those abstract structures, which are laid down by counting, have unfolded visibly only in the course of the history of mathematics – that is, history has brought to the fore the fulness of theorems and interconnections which make up the contents of that complicated science which is the theory of numbers. In a similar way, also at the beginning of an art style, for instance in architecture, certain simple basic forms are found, e.g. the semicircle and the square in the Romanesque architecture. Out of these basic forms emerge – in the course of history – new, more complicated, even changed forms which, however, can in some way be conceived as variations on the same theme. Thus, from such basic structures, a new manner, a new style of construction is developed. One has the feeling that the possibilities of development could be detected in these primordial forms already at the beginning. Otherwise it would be hardly understandable that many gifted artists decided quite rapidly to pursue these new possibilities.

A similar unfolding of abstract basic structures has doubtlessly taken place also in the cases I have enumerated concerning the history of the exact natural sciences. This growth, the development of continually new branches has lasted, in the case of Newtonian mechanics, until the middle of the past century. In our century we have experienced something similar in the theory of relativity and in the quantum theory – and the growth is not yet completed. Incidentally, this process has also – in science as well as in art – an important social and ethical aspect. For many persons can actively participate in it. When in the Middle Ages a large cathedral had to be built, many architects and craftsmen were employed. They were filled with the perspective of the beauty which was laid down in the primordial forms, and were obliged, by their very task, to perform precisely accurate work in the spirit of such forms. In a similar way, during the two centuries that followed Newton's discovery many mathematicians, physicists and technicians had the task of treating individual mechanical problems according to the Newtonian methods, or of carrying out experiments or of undertaking technical applications. And here, too, always the greatest accuracy was demanded in order to attain whatever was possible within the framework of Newtonian mechanics. Perhaps one may say in general that through the underlying structures – in this case, Newtonian mechanics – guidelines are drawn or even value standards set according to which it can be objectively determined whether a given task has been performed rightly or wrongly. Just because of the fact that here precise requirements can be established, that the individual can co-operate – through little contributions – to the attainment of great goals, that an objective decision can be made about the value of his contribution: from all of this the satisfaction arises which actually flows, from such a development, to the large circle of the persons involved. Consequently, one should also not underrate the ethical significance of technology for the present time.

Out of the development of natural science and technology has come forth, for instance, also the idea of the airplane. The individual technician who constructs any partial gear for the airplane – and the worker who produces it – knows that everything hinges on the extreme precision and accuracy of his work, that perhaps even the lives of many persons depend on its reliability. Consequently, he gains the pride which a job well done warrants. And he rejoices with us at the beauty of the airplane when he perceives that, in it, the technological goal has been implemented with the rightly suitable means. Beauty is – so runs the already repeatedly quoted ancient definition – the right concordance of the parts with each other and with the whole. But this requirement must also be fulfilled in a good airplane. But, by this reference to the development of a beautiful basic structure – and to the ethical values and requirements which later emerge in the historical course of such a development – the question posed before is still not yet answered. What shines up in such structures so that the great interconnection can be known, even before it is rationally understood in detail? By the way, the possibility should be excluded in advance that such a knowing may be subject to illusions. But that there is this immediate knowing, this fright in front of beauty – as Plato put in the Phaedros – it cannot be doubted at all. Among all those who have had investigated this question there seems to be a consensus that such an immediate knowing does not take place through discursive, that is, rational thinking. I would like to cite here at some length two statements. One is by Johannes Kepler of whom we have spoken before. The other, from our own time, is due to the atomic physicist of Zurich, Wolfgang Pauli, who was a friend of the psychologist C. G. Jung. The first text is to be found in Kepler's work Cosmic Harmony and reads: "That power which notices and knows the noble proportions in sensible objects and in other external things has to be ascribed to the lower region of the soul. It is very close to the power which provides the senses with their formal schemes or, even more deeply, to the purely vital power of the soul. It does not think in discursive way, that is deductively – as philosophers do – and does not employ any lofty method. Therefore it is not proper to man but also inheres in the wild beasts and domestic cattle ... One could then ask from what source that soul power which has no share in conceptual thinking and therefore also no proper cognition of harmonic relations may have the ability to know what is there, in the external world. For to know means to compare that which can be outwardly noticed through the senses with the inward primordial images and thus judge its concordance with them. Proclos has, in this connection, a very beautiful expression by using the image of waking up from a dream. The sensible things of the external world bring back to our memory those things which we have perceived before in the dream. In the same way the mathematical relationships which are present in sensible reality conjure up those intelligible primordial images which are inwardly present in advance. As a result they now shine up in the soul, efficaciously and vivaciously, while before they were present only in a nebulous way. But how have they penetrated to the interior of man? To this I answer – Kepler goes on to say – that all pure ideas or primordial formal relationships concerning the harmony of which we have been speaking inhabit interiorly those who have a capacity to apprehend them. But they are not first taken into the interior of man through a conceptual process. Rather they stem from one, as it were, instinctive and pure contemplation of sublimity. They are innate in these individuals, just as the morphological principle of plants – for instance, concerning the number of petals or the number of seed receptacles for the apple – is innate."

Kepler, then, indicates here possibilities that may be already present in the animal and vegetable realms, namely inborn primordial images which bring about the cognition of forms. In our time Portmann, in particular, has discussed such possibilities. He describes for instance certain colorful patterns which are embodied in the plumage of birds and which can have a biological sense only if they are noticed by other birds of the same kind. The ability to notice, therefore, must be inborn just as the pattern itself. Here one can also think of the singing of birds. At first what is biologically required here is only a definite acoustic signal which serves, for instance, in the search for a mate and is understood by the mate itself. But in the measure that the immediate biological function decreases in importance, it may happen that the treasure of forms – namely, the underlying melodic structure – can acquire a playful enlargement and development. This then, as song, enraptures also such a biologically unrelated being as man. The ability to recognize the play of such forms must, in any case, be inborn in the bird species involved – it certainly stands in no need of discursive rational thinking. As regards man, to cite another example, he has probably the ability inborn to understand certain basic forms of gesticulation and to decide accordingly whether his neighbor harbors friendly or hostile intentions – an ability which is of the greatest significance for the social life of people.

Ideas similar to those of Kepler are expressed in an essay by Wolfgang Pauli. Pauli writes: "The process of understanding in nature – as well as the delight that man feels in the act of understanding, that is, when he becomes aware of a new cognition – seems therefore to consist in a correspondence, a coming-to-cover-each-other: pre-existing internal images of the human psyche with external objects and their behavior. This conception of the knowledge of nature goes back to Plato, as is well known, and ... is also advocated very clearly by Kepler. He speaks in fact of ideas which pre-exist in the spirit of God and are created with the soul because of its being the image of God. These primordial images which the soul can perceive with the help of an inborn instinct Kepler calls archetypal. The agreement with the primordial images or archetypes which C. G. Jung has introduced into modern psychology as instincts of the active imagination is quite far-reaching. Modern psychology gives the proof that every understanding is a lengthy process which is attended by unconscious processes long before the consciousness content is capable of rational expression. By so doing, psychology has again directed the attention to the preconscious archaic stage of knowledge. At this stage, instead of clear concepts, images are present with a strong emotional content. They are not thought but so to speak, contemplated pictorially. The archetypes function as ordering operators and shapers of this world of symbolic images. They act as the sought-for bridge between sense perceptions and ideas and therefore are also a necessary prerequisite for the emergence of a scientific theory. However, one must beware of transposing this a priori of knowledge into the field of consciousness and relate it to definite ideas which can be formulated rationally."

In addition Pauli discusses in the further course of his researches, the fact the Kepler came to the conviction about the rightness of the Copernican system not primarily because of detailed results of astronomical observations. Rather, what moved him was the correspondence of the Copernican image with an archetype – which C. G. Jung calls Mandala – that Kepler employs also as a symbol of the holy Trinity. God stands in the center of a sphere as the First Mover. The world, in which the Son is at work, is compared to the surface of the sphere. The Holy Spirit corresponds to the rays that run from the center to the surface of the sphere. Naturally, it belongs to the essence of such primordial images that they cannot be described in a precisely rational way. Even though Kepler may have attained his conviction about the rightness of the Copernican system also from such primordial images, a decisive prerequisite for any reliable scientific theory remains that it subsequently stand the test of empirical checking and rational analysis. On this point Kepler himself was entirely agreed. Here are the natural sciences in a happier position than the arts because for science there is an inescapable and inexorable criterion of value from which no piece of research can subtract itself. The Copernican system, the Keplerian laws and Newton's mechanics have subsequently proved their worth – through the interpretation of experiences, the data of observation and technology – with such an extension and such an extreme precision that their rightness could no longer be doubted ever since the appearance of Newton's Principia . Still, what is in question here is an idealization – of the kind that Plato had considered necessary and Aristotle had reproved.

This fact came to the fore with complete clarity only about 50 years ago. Then people realized, through the experiences of atomic physics, the Newton's conceptual construction no longer sufficed to attain to the mechanical phenomena in the interior of the atom. Since the Planckian discovery of the quantum of action in 1900, a situation of bewilderment had arisen in physics. The old rules according to which man had successfully described nature for over two centuries resisted an adaptation to the new experiences. But also these experiences themselves were internally contradictory. A hypothesis which proved valuable in one experiment failed in another. The beauty and compactness of the old physics appeared destroyed. It seemed that, out of the often diverging attempts, it was not possible to obtain a genuine insight into new and different interconnections. I do not know whether it is permissible to compare the situation of physics in those 25 years after the Planckian discovery – which I still experienced as a young student – to the conditions of contemporary modern art. But I must confess that such a comparison forces itself upon me, time and again. The helplessness before the question what one should do with bewildering phenomena, the affiction over the loss of interconnections which still appeared so convincing – all this dissatisfaction has certainly determined the traits of the two so different realms and epochs in a similar way. However, what is in question here is obviously a necessary intermediate stage which cannot be skipped and which prepares a future development. For – as Pauli put it – every understanding is a lengthy process which is introduced by unconscious processes, long before the consciousness content is capable of rational formulation. Archetypes function as the sought-for bridge between sense perceptions and ideas. In the moment, however, when the right ideas emerge, a completely undescribable process of highest intensity comes to pass in the soul of the person who sees them. It is the astonished fright of which Plato speaks in the Phaedros . The soul, as it were, remembers what it had always possessed unconsciously. Kepler says: "geometria est archetypus pulchritudinis mundi". "Mathematics – we can generalize in translation – is the primordial image of the beauty of the world.'' In atomic physics this occurrence has been experienced less than fifty years ago. And it has restored exact natural science to a state of harmonious compactness under entirely new presuppositions – a state that had been lost for a quarter of a century. I do not see any reason why something similar should not happen one day in art. But one must add the warning: something like that man cannot make, it must happen by itself.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I have described to you this aspect of exact natural science because in it the kinship to the fine arts becomes most clearly visible and because here the misunderstanding can be forstalled which sees science and technology as concerned only with exact observation and rational, discursive thinking. Of course rational thinking and accurate measuring do belong to the work of the investigator of nature – just as hammer and chisel belong to the work of the sculptor. But they are in both cases just tools, not content of the work itself. Perhaps at the close I may still recall once the second definition of the concept ‘beauty’ which stems from Plotinus and in which there is no mention of parts and whole. "Beauty is the translucence of the eternal splendor of the 'One' through the material phenomenon." There are important epochs in the history of art to which this definition applies better than to the aforementioned one. Frequently we feel a nostalgia for such epochs. But in our time it is difficult to speak of this aspect of beauty – and perhaps it is a good norm to adapt oneself to the customs of the time in which one has to live, and keep silent about that which is hard to say. In fact, the two definitions are not too remote from each other. Let us therefore be satisfied with the first more prosaic definition of beauty which certainly is verified also in natural science. And let us realize that beauty is – in exact natural science just as in the arts – the most important source of illumination and clarity.

from a Lecture delivered to the Bayerische Akademie der Schönen Künste, München, July 9, 1970. Published as private paper in Stuttgart, 1971. Translation from German into English by Enrico Cantore.

Going in depth

Comments and Documents on special issues on Religion and Science

Websites on Science and Religion

Articles of Historical Interest

Documents for the 2009 Anniversary: International Year of Astronomy and II Centenary of Darwin’s birth

Survival of the Prettiest: Harvard Cognitive Scientist Nancy Etcoff on the Science of Beauty

By maria popova.

“That is the best part of beauty, which a picture cannot express,” Francis Bacon observed in his essay on the subject . And yet for as far back as humanity can peer into the past, we’ve attempted again and again to capture and define beauty. For Indian philosopher Tagore, beauty was the Truth of eternity . For Richard Feynman, it was the mesmerism of complexity . For E. B. White, it was the power of simplicity . For the influential early art theorist Denman Waldo Ross, it was a supreme instance of order. For legendary philosopher Denis Dutton, it was “a gift handed down from the intelligent skills and rich emotional lives of our most ancient ancestors.” But despite all these metaphysical explanations, we continue to strive for a concrete, tangible, material answer.

That’s precisely what Harvard’s Nancy Etcoff sets out to unearth in Survival of the Prettiest: The Science of Beauty ( public library ) — an inquiry into what we find beautiful and why that frames beauty as “the workings of a basic instinct” and explores such fascinating facets of the subject as our evolutionary wiring, the ubiquitous response to beauty across human cultures, and the universal qualities in people that evoke this response.

Etcoff begins by confronting our intellectual apologism for the cult of beauty:

Many intellectuals would have us believe that beauty is inconsequential. Since it explains nothing, solves nothing, and teaches us nothing, it should not have a place in intellectual discourse. And we are supposed to breathe a collective sigh of relief. After all, the concept of beauty has become an embarrassment. But there is something wrong with this picture. Outside the realm of ideas, beauty rules. Nobody has stopped looking at it, and no one has stopped enjoying the sight. Turning a cold eye to beauty is as easy as quelling physical desire or responding with indifference to a baby’s cry. We can say that beauty is dead, but all that does is widen the chasm between the real world and our understanding of it.

Etcoff admonishes against confusing beauty with all the manufactured — and industriously exploited — stand-ins for it:

Madison Avenue cleverly exploits universal preferences but it does not create them, any more than Walt Disney created our fondness for creatures with big eyes and little limbs, or Coca-Cola or McDonald’s created our cravings for sweet or fatty foods. Advertisers and businessmen help to define what adornments we wear and find beautiful, but … this belongs to our sense of fashion, which is not the same thing as our sense of beauty.

“If everyone were cast in the same mould, there would be no such thing as beauty,” Darwin famously reflected , and Etcoff echoes his admonition in turning to the menacing domino effect of this proposition in action and what it robs us of:

The media channel desire and narrow the bandwidth of our preferences. A crowd-pleasing image becomes a mold, and a beauty is followed by her imitator, and then by the imitator of her imitator. Marilyn Monroe was such a crowd pleaser that she’s been imitated by everyone from Jayne Mansfield to Madonna. Racism and class snobbery are reflected in images of beauty, although beauty itself is indifferent to race and thrives on diversity.

One of the most fascinating aspects of beauty, however, is how bound it is with judgment, and self-judgment in particular. One of the products of our narcissistic bias, Etcoff argues, is that we greatly exaggerate the minute fluctuations in our outward appearance:

To the outside world we vary in small ways from our best hours to our worst. In our mind’s eye, however, we undergo a kaleidoscope of changes, and a bad hair day, a blemish, or an added pound undermines our confidence in ways that equally minor fluctuations in our moods, our strength, or our mental agility usually do not.

Equally, we direct our real-time assessments of appearance towards others:

We are always sizing up other people’s looks: our beauty detectors never close up shop and call it a day. We notice the attractiveness of each face we see as automatically as we register whether or not they look familiar. Beauty detectors scan the environment like radar: we can see a face for a fraction of a second (150 msec. in one psychology experiment) and rate its beauty, even give it the same rating we would give it on longer inspection. Long after we forget many important details about a person, our initial response stays in our memory.

She traces the cross-cultural, age-old extremes to which people go for “beauty” — or, really, for control of those judgments, whether by self or others:

In Brazil there are more Avon ladies than members of the army. In the United States more money is spent on beauty than on education or social services. Tons of makeup—1,484 tubes of lipstick and 2,055 jars of skin care products—are sold every minute. During famines, Kalahari bushmen in Africa still use animal fats to moisturize their skin, and in 1715 riots broke out in France when the use of flour on the hair of aristocrats led to a food shortage. The hoarding of flour for beauty purposes was only quelled by the French Revolution.

But our fixation on beauty is so profound that it even permeates the most elevated of human spirits. Etcoff gives Eleanor Roosevelt, one of history’s most remarkable hearts and minds , and Leo Tolstoy, enduring sage of human wisdom , as tragic examples:

When Eleanor Roosevelt was asked if she had any regrets, her response was a poignant one: she wished she had been prettier. It is a sobering statement from one of the most revered and beloved of women, one who surely led a life with many satisfactions. She is not uttering just a woman’s lament. In Childhood, Boyhood, Youth , Leo Tolstoy wrote, “I was frequently subject to moments of despair. I imagined that there was no happiness on earth for a man with such a wide nose, such thick lips, and such tiny gray eyes as mine.… Nothing has such a striking impact on a man’s development as his appearance, and not so much his actual appearance as a conviction that it is either attractive or unattractive.”

(It is especially ironic and demonstrative of the oppressive power of such ideals that Roosevelt famously wrote, “When you adopt the standards and the values of someone else … you surrender your own integrity. You become, to the extent of your surrender, less of a human being.” )

Still, the mesmerism of beauty and its grip on us, Etcoff argues, is too deep-seated to be undone by its mere intellectual recognition:

Appearance is the most public part of the self. It is our sacrament, the visible self that the world assumes to be a mirror of the invisible, inner self. This assumption may not be fair, and not how the best of all moral worlds would conduct itself. But that does not make it any less true. Beauty has consequences that we cannot erase by denial. Beauty will continue to operate — outside jurisdiction, in the lawless world of human attraction. Academics may ban it from intelligent discourse and snobs may sniff that beauty is trivial and shallow but in the real world the beauty myth quickly collides with reality.

Framing beauty as a “basic pleasure,” Etcoff argues that our response to it is actually the sign of a healthy human mind. Conversely, the absence of such a response is one of the key symptoms of severe depression, one that goes hand-in-hand with anhedonia — the inability to take pleasure in things that once pleased us.

Although the object of beauty is debated, the experience of beauty is not. Beauty can stir up a snarl of emotions but pleasure must always be one (tortured longings and envy are not incompatible with pleasure). Our body responds to it viscerally and our names for beauty are synonymous with physical cataclysms and bodily obliteration — breathtaking, femme fatale, knockout, drop-dead gorgeous, bombshell, stunner, and ravishing. We experience beauty not as rational contemplation but as a response to physical urgency.

She offers some exquisite examples of beauty’s contemplation from the annals of literary history:

The most lyrical description of an encounter with beauty — solitary, spontaneous, with an unknown other—comes in James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man when Stephen Dedalus sees a young woman standing by the shore with “long, slender bare legs,” and a face “touched with the wonder of mortal beauty.” Her beauty is transformative and gives form to his sensual and spiritual longings. “Her image had passed into his soul for ever and no word had broken the holy silence of his ecstasy.… A wild angel had appeared to him, the angel of mortal youth and beauty, an envoy from the fair courts of life, to throw open before him in an instant of ecstasy the gates of all the ways of error and glory. On and on and on and on!” Ezra Pound had a moment of recognition that inspired him to write a two-line poem “In a station at the Métro,” which comprised these brief sentences: “The apparition of these faces in the crowd: Petals, on a wet, black bough.” Later, Pound described how he came to write it. “Three years ago in Paris I got out of a Métro train at La Concorde, and saw suddenly a beautiful face, and then another and another, and then a beautiful child’s face, and then another beautiful woman, and I tried all day to find words for what this had meant to me, and I could not find any words that seemed to me worthy or as lovely as that sudden emotion.… In a poem of this sort one is trying to record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself or darts into a thing inward and subjective.”

Etcoff argues that we each possess an intrinsic beauty “template” that we intuit, against which we measure everything we observe:

People judge appearances as though somewhere in their minds an ideal beauty of the human form exists, a form they would recognize if they saw it, though they do not expect they ever will. It exists in the imagination. […] The human image has been subjected to all manner of manipulation in an attempt to create an ideal that does not seem to have a human incarnation. When Zeuxis painted Helen of Troy he gathered five of the most beautiful living women and represented features of each in the hope of capturing and depicting her beauty. There are no actual descriptions of Helen, nor of other legendary beauties such as Dante’s Beatrice. Their faces are blank slates, Rorschach inkblot tests of our imaginings of the features of perfect beauty.

But as unique as we would like to think we are, these inner templates turn out to be far more uniform. Etcoff cites the work of anthropometrist Leslie Farkas, who measured the facial proportions of 200 women, including 50 models, as well as young males and kids, and asked a large sample of participants to rate their appearance, then compared the results with the conventions of the classical beauty canon. The surprising findings, Etcoff argues, illustrates how measurement systems have failed at producing a formula for beauty and instead reveal something profound about the brokenness of the prescriptive canon:

The canon did not fare well. Many of the measures did not turn out to be important, such as the relative angles of the ear and nose. Some seemed pure idealizations: none of the faces and heads in profile corresponded to equal halves or thirds or fourths. Some were inaccurate—the distance between the eyes of the beauties was greater than that suggested by the canon (the width of the nose). Farkas’s results do not mean that a beautiful face will never match the Renaissance and classical ideals. But they do suggest that classical artists might have been wrong about the fundamental nature of human beauty. Perhaps they thought there was a mathematical ideal because this fit in a general way with platonic or religious ideas about the origin of the world.

And yet beauty is a very real piece of the human experience and bespeaks some of our greatest existential tensions, such as the mortality paradox . Etcoff writes:

Attitudes toward beauty are entwined with our deepest conflicts surrounding flesh and spirit. We view the body as a temple, a prison, a dwelling for the immortal soul, a tormentor, a garden of earthly delights, a biological envelope, a machine, a home. We cannot talk about our response to our body’s beauty without understanding all that we project onto our flesh.

Though at first glance borderline reductionist in its excessive reliance on evolutionary explanations, the rest of Survival of the Prettiest: The Science of Beauty goes on demonstrate why science and philosophy need each other and how the social sciences fit into the intellectual debate on beauty. Complement it with Etcoff’s compelling TED talk on the surprising science of happiness — a fine addition to these essential reads on the art and science of happiness — in which she explores the evolutionary explanations of beauty:

— Published July 1, 2013 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2013/07/01/survival-of-the-prettiest-nancy-ectoff/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books culture psychology science women, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

May 21, 2014

Truth and beauty in science

Philip Ball who is one of my favorite science writers has a thoughtful rumination on the constant tussle between beauty and truth in science.

By Ashutosh Jogalekar

This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Philip Ball who is one of my favorite science writers has a thoughtful rumination on the constant tussle between beauty and truth in science. Ball argues that the expectation of beauty as a guide to scientific truth is quite uncertain and messy and successes are anecdotal, and I tend to agree with him. There are undoubtedly theories like general relativity which have been called 'beautiful' by both their creators and their followers, but for many other concepts in science the definition is much more tricky. Ball again raises the question asked by Keats: is beauty truth? And is truth beauty?

To begin with it's clear to me that the definition of beauty depends on the field. For instance in physics it's much easier to call the Dirac equation beautiful based on the fact that it can be written on a napkin and can explain an untold number of phenomena in a spare, lucid line of symbols. But as I pointed out in a previous post, appreciating beauty in chemistry and biology is harder since most chemical and biological phenomena cannot be boiled down to simple-looking equations. In a previous post I have also noted how simple equations in chemistry can look beautiful and yet be approximate and limited, and how complicated equations can look ugly and yet be universal, giving answers precise to six decimal places. Which equation do you then define as being the more ‘beautiful’ one?

It's also apparent to chemists that in chemistry, beauty resides significantly in the visualization of chemical structures. Line drawings of molecules and 3D representations of proteins are recognizable as beautiful, even to non-chemists. Yet this beauty might be deceptively seductive. For instance many ‘impossible’ or highly unstable molecules look beautiful when sketched out, and many beautiful-looking protein structures are actually imperfect models, built from uncertain and messy data and subjects to the whims and biases of their creators.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

I have always suspected that 'beauty' is more of a place-card or a proxy for something else, and in his article Ball quotes the well-known physicist Nima Arkani-Hamed to this effect. It's a sentiment which sounds like a cogent guideline for defining beauty:

It’s not fashion, it’s not sociology. It’s not something that you might find beautiful today but won’t find beautiful 10 years from now. The things that we find beautiful today we suspect would be beautiful for all eternity. And the reason is, what we mean by beauty is really a shorthand for something else. The laws that we find describe nature somehow have a sense of inevitability about them. There are very few principles and there’s no possible other way they could work once you understand them deeply enough. So that’s what we mean when we say ideas are beautiful.

In his quote Arkani-Hamed is alluding to many criteria of beauty cited especially by physicists and mathematicians; concision, universality, timelessness and inevitability. That's a worthy listing of qualities. Nobody expects the basic theorems of general relativity or quantum mechanics to be upended any time soon. However, Arkani-Hamed's quote also makes me suspect that it is precisely the connection of beauty with these other qualities that makes it accessible only to the most penetrating minds in the field. For instance Einstein, Paul Dirac and the mathematician Hermann Weyl are often quoted as thinkers who perpetuated howlers declaring their allegiance to beauty over truth. But another way to interpret these anecdotes is to wonder if Dirac, Weyl and Einstein were precisely the kind of superlative minds that could actually see beauty as the manifestation of these more subtle and deep qualities. If this were indeed true, then the mundane conclusion would be that beauty is indeed truth, but only when proclaimed by an Einstein, a Weyl or a Dirac.

There is one criterion among those described by Arkani-Hamed that does apply to the 3D representations of proteins that I discussed above - timelessness. For instance, Nobel Prizes have been awarded to many crystal structures of important biomolecular assemblies like the ribosome and the potassium ion channel. There is no doubt that more detailed explorations will uncover unexpected details of the structures, but the basic architecture of these fundamental molecular machines will likely never have to be revised; it is, for many purposes, timeless.

Other qualities that underlie beauty can be more controversial. For instance Ball says that the whole concept of symmetry which is not only regarded as a great test of beauty in physics but which has also led to many of the field's most fundamental advances, is also a poor guide in other fields like art and poetry. There are numerous instances of art (Picasso) and poetry (T. S. Eliot for instance) which lack elements of symmetry, and yet they are considered important classics. But that's where Ball points out that unlike the equations of relativity, art and poetry are much more subjective and therefore much more subject to the changing currents of society and fashion. But are they, really? We do consider Einstein’s field equations to be timeless, but what about ‘The Wasteland’?

Ultimately notions of beauty and its connection to truth are always going to be murky, of uncertain merit, even dubious. And yet I completely agree with Ball that scientists and artists should not give up their quest to find beauty in nature and in their works, if only because it serves to propel ideas forward and stimulate them to think in new ways. The one thing he asks is that they make their intentions and thought processes clear.

Despite all this, I don’t want scientists to abandon their talk of beauty. Anything that inspires scientific thinking is valuable, and if a quest for beauty – a notion of beauty peculiar to science, removed from art – does that, then bring it on. And if it gives them a language in which to converse with artists, rather than standing on soapboxes and trading magisterial insults like C P Snow and F R Leavis, all the better. I just wish they could be a bit more upfront about the fact that they are (as is their wont) torturing a poor, fuzzy, everyday word to make it fit their own requirements. I would be rather thrilled if the artist, rather than accepting this unified pursuit of beauty (as Ian McEwan did), were to say instead: ‘No, we’re not even on the same page. This beauty of yours means nothing to me.’

Spotlight on Science: The Evolution of Beauty

- By Megha Chawla

- April 21, 2018

The Evolution of Beauty is a compelling and insightful look at beauty in nature through the eyes of Richard O. Prum, the William Robertson Coe Professor of Ornithology at Yale. The book is Prum’s response to decades of research in the evolutionary sciences that have embraced Darwinian thought and theory of natural selection, while woefully ignoring Darwin’s theory of sexual selection. Through a lifetime of observing birds in nature and researching the evolution of ornamental beauty, Prum contends to revive the arbitrary sexual selection hypothesis, or as he calls it, “Beauty Happens.”

According to Prum, animals have subjective tastes and preferences and the agency to act upon them via mate choice. Prum compares adaptationists, who believe that all traits have evolved to provide a better chance of survival and communicate information about mate quality, to economic theorists, who expect actors in a free market to behave completely rationally and purposefully. “Of course,” Prum says, “Evolution, like markets, is spurred by the irrational and subjective choices of its actors.” He provides a motley of colorful examples from the bird world to support this hypothesis, like the evolution of the male peacock’s seemingly useless tail which may even be harmful to survival, but has nonetheless persisted because the ladies like it.

In the animal kingdom, it is often the female who chooses a mate among available males. Because of this, Prum’s argument also has a feminist flair. He describes how male and female ducks’ genitalia and the male bowerbird’s elaborate bower-building ritual might have evolved for the same purpose—to protect females from forced copulation. Prum even extends his hypothesis to the evolution of the female orgasm in great apes and the size and shape of the human penis, claiming that female sexual autonomy has led to their evolution—or, in his words, “Pleasure Happens.”

The Evolution of Beauty is interdisciplinary at its core, and Prum passionately comments on evolution from multiple perspectives. While the book has been well-received—the New York Times named it as one of the ten best books of 2017—Prum says the response from the scientific community has been mostly mute. “I’m perfectly happy to lose the battle and win the war,” he said, hoping his work will inspire further research recognizing aesthetic preference as a strong force in evolution.

On the whole, The Evolution of Beauty endures as a brilliant anthology of beauty and desire in the natural world, written in engaging prose that is vivid, graphic, and at times unexpectedly funny. Prum humorously and appropriately quotes Sean Hannity’s remarks on his research: “Don’t we really need to know about duck sex?” If you thought you, like Sean Hannity, didn’t care about the mating habits of ducks—or never gave them any thought at all—this book will make you strongly reevaluate your indifference.

[1] Interview with Richard O. Prum, PhD, Professor of Ornithology, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale University, interview on 02/02/18

[2] Darwin, F., (Ed), Letter to Asa Gray, dated 3 April 1860, The Life and Letters of Charles

Darwin, D. Appleton and Company, New York and London, Vol. 2, pp. 90–91, 1911

[3] Prum, R. O. (2017). The Evoltuion of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of Mate

Choice Shapes the Animal World – and Us.

THE NATION'S OLDEST COLLEGE SCIENCE PUBLICATION

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- ADVERTISEMENT FEATURE Advertiser retains sole responsibility for the content of this article

Recognizing the beauty of science, and the science behind beauty

Produced by

Lisa Napolione, Senior Vice President, Global Research & Development at The Estée Lauder Companies

The Estée Lauder Companies has a long history of science and innovation. Fifty years ago, the prestige beauty company created the world’s first allergy-tested, fragrance free skincare line — and it has continued to roll out transformative beauty products ever since. The Company recently partnered with Nature Research to create two new prizes designed to inspire women in science, technology, engineering or mathematics (STEM), one to honour early career female scientists making pioneering discoveries, and the other to recognize leaders — women and men — behind initiatives supporting greater equality in STEM. Biochemical engineer Lisa Napolione, who leads the Company’s R&D efforts, explains the impetus for the awards and how The Estée Lauder Companies takes a science-driven approach to skincare and beauty.

The new prizes are designed to inspire women in STEM, and focus on different things. Why put the spotlight on educators and young researchers?

Both of these areas are critical in their own right and integral to everything we do at The Estée Lauder Companies. We are a company that was founded by a pioneering woman who supported other women and who remains an inspiration to all of us — and so honouring exceptional female researchers through the Inspiring Science Award really spoke to us. We hope it not only shines a much-deserved light on the achievements of exceptional women in STEM, but also helps to establish a new generation of role models. The second award — the Innovating Science Award — recognizes a person or an organization that promotes STEM to girls and young women. I really feel strongly that young girls need role models and mentors in STEM, because without these influences we wouldn’t have the deep bench of research expertise among the next generation of scientists.

This all sounds very personal to you.

It is! I was so fortunate that early in my education, I had a mentoring role-model, Nora Kyser, who was one of the first female chemical and ceramic engineers in all of the United States. She was my high school chemistry teacher in my little hometown in western New York, and she arranged with the school district that, if she paid for her own research, she could work after hours in the school’s laboratory. She saw something in me, and hired me as her lab assistant. Her hands-on personal attention affected me so much. It was an amazing experience for which I will be forever grateful — and it inspired me to do for others what she did for me. I do what I do today because of her.

How does science inform how products are developed at The Estée Lauder Companies?