Shaping Your Legacy: How to Write a Compelling Autobiography

- The Speaker Lab

- March 12, 2024

Table of Contents

Ever thought about how your life story would read if it were a book? Writing an autobiography is like creating a map of your personal journey, each chapter representing milestones that shaped you. But where do you start and how can you ensure the tale holds interest?

This guide will help unravel those questions by delving into what makes an autobiography stand out, planning techniques to keep your narrative on track, writing tips for engaging storytelling, and even ethical considerations when revealing private aspects of your life.

We’ll also touch on refining drafts and navigating publishing options. By the end of this read, you’ll be equipped with all the insights you need to create a compelling autobiography!

Understanding the Essence of an Autobiography

An autobiography provides a comprehensive view of one’s life journey from birth to the present day. Imagine climbing into a time machine where every chapter represents different eras in your life. The goal of an autobiography is to allow readers to explore a factual, chronological telling of the author’s life.

Autobiographies aren’t merely catalogues of events, however; they need soulful introspection too. Think about why certain episodes mattered more than others and how those experiences influenced your perspectives or decisions later on.

You’ll also want to infuse emotional honesty, allowing yourself vulnerability when recalling both triumphant milestones and painful obstacles. Authenticity creates connections between authors and their audience, so let them see real human emotions behind every word written.

Distinguishing Features Of An Autobiography

The unique thing about autobiographies is they are first-person narratives . This allows readers to experience everything through your eyes, as if they’re living vicariously through you. From triumphs to trials, each page unravels another layer of who you are.

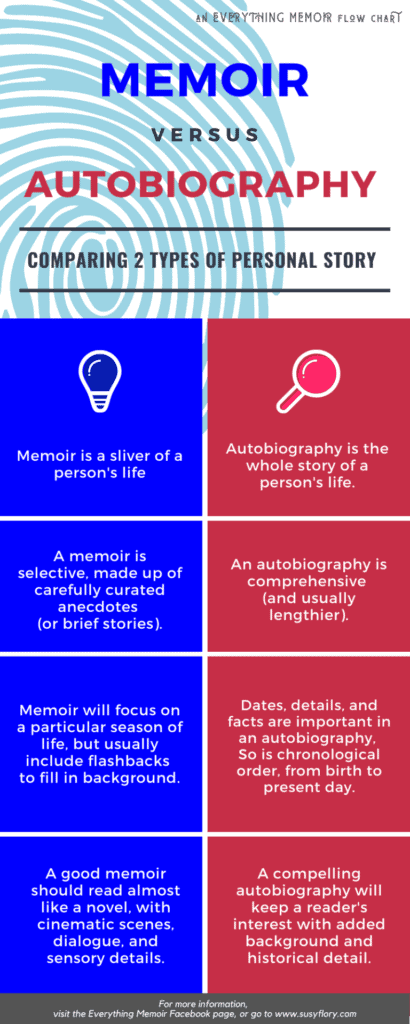

While memoirs are also first-person narratives of a person’s life, there are different from autobiographies. In a memoir, the author focuses on a particular time period or theme in their life. If you’d rather skip the details and dates needed for an autobiography and focus more on emotional truths, you might consider writing a memoir.

Find Out Exactly How Much You Could Make As a Paid Speaker

Use The Official Speaker Fee Calculator to tell you what you should charge for your first (or next) speaking gig — virtual or in-person!

Pre-Writing Stage: Planning Your Autobiography

The planning stage is a crucial part of writing your autobiography. It’s where you map out the significant events in your life, establish a timeline, and identify who will be reading your story.

Selecting Key Life Events

To start, you need to pinpoint key moments that have shaped you. While you will include plenty of factual details in your autobiography, you won’t include every single one. Rather, you’ll be spending the majority of your autobiography focusing on the transformative experiences that defined your life journey. After all, an autobiography is not just a catalogue of events; it’s also an exploration into what these experiences meant to you.

Establishing A Timeline

Next up is establishing a timeline for your narrative flow. Since you’re writing an autobiography, it’s important to first map out your story chronologically so that you can keep your events straight in your mind. MasterClass has several suggestions for key elements you might want to include in your timeline.

Identifying Your Audience

Finding out who’ll read your book helps shape its tone and style. Self-Publishing School says understanding whether it’s for close family members or broader public can guide how personal or universal themes should be presented.

While this process might feel overwhelming initially, take time with this stage. Good planning sets solid foundations for creating an engaging autobiography.

Writing Techniques for an Engaging Autobiography

If you’re on the journey to pen down your life story, let’s dive into some techniques that can help transform it from a simple narrative into a riveting read. An engaging autobiography is more than just facts and dates—it’s about weaving your experiences in such a way that they captivate readers.

Incorporating Dialogue

The first technique involves incorporating dialogue. Rather than telling your audience what happened, show them through conversations. It lets the reader experience events as if they were there with you. As renowned author Stephen King suggests , dialogue is crucial in defining a the character of a person (including yourself).

Using Vivid Descriptions

Vivid descriptions are another effective tool in creating an immersive reading experience. But remember: overdoing it might overwhelm or bore the reader, so find balance between being descriptive and concise.

Narrative Techniques

Different narrative techniques can also enhance storytelling in autobiographies. For instance, foreshadowing creates suspense; flashbacks provide deeper context; and stream of consciousness presents thoughts as they occur naturally—a powerful way to share personal reflections.

All these writing tools combined will give you a gripping account of your life journey—one where every turn of page reveals more layers of depth and dimensionality about who you are as both character and narrator.

Structuring Your Autobiography for Maximum Impact

Deciding on the right structure for your autobiography is essential to ensure your book captivates readers and keeps them engaged.

The first step towards structuring your autobiography effectively is deciding whether to organize it chronologically or thematically. A chronological approach takes readers on a journey through time, letting each event unfold as you experienced it. On the other hand, a thematic approach revolves around central themes that have defined your life—think resilience, ambition or transformation—and might jump back and forth in time.

Creating Chapters

An effective way to manage the vast amount of information in an autobiography is by dividing it into chapters. Each chapter should be structured around a specific time frame (if you’re opting for chronological order) or theme (if taking the thematic approach). The key here isn’t necessarily sticking rigidly to these categories but using them as guides to help shape and direct your narrative flow.

Crafting Compelling Beginnings and Endings

A strong beginning pulls people into your world while an impactful ending stays with them long after they’ve closed the book—a little like how memorable speeches often start with something surprising yet relatable and end leaving audiences pondering over what they’ve heard. So consider starting off with something unexpected that gives insight into who you are rather than birthplace/date details right away. For endings, look at wrapping up major themes from throughout the book instead of simply closing out on latest happenings in your life.

Remember, structuring an autobiography is as much about the art of storytelling as it is about chronicling facts. Use structure to draw readers in and take them on a journey through your life’s highs and lows—all the moments that made you who you are today.

Ethical Considerations When Writing an Autobiography

When penning your life story, it’s important to respect privacy and handle sensitive issues well. Because let’s face it, writing about others in our lives can be a slippery slope. We need to tread carefully.

Respecting Privacy: Telling Your Story Without Invading Others’

The first thing we have to consider is the right of privacy for those who cross paths with our narrative journey. While they might play crucial roles in our stories, remember that their experiences are their own too.

A good rule of thumb is to get explicit consent before mentioning anyone extensively or revealing sensitive information about them. In some cases where this isn’t possible, anonymizing details or using pseudonyms could help maintain privacy while keeping the essence of your story intact. Author Tracy Seeley sheds more light on how one should handle such situations responsibly.

Navigating Sensitive Topics With Care

Sensitive topics often make for compelling narratives but dealing with them requires tact and empathy. You’re walking a tightrope, balancing honesty and sensitivity, a fall from which can lead to hurt feelings or even legal troubles.

An excellent way around this dilemma would be by focusing on how these experiences affected you personally rather than detailing the event itself. Remember, your autobiography is an opportunity to share your life experiences, not just a platform for airing grievances or settling scores.

Maintaining Honesty: Your Authentic Self Is the Best Narrator

Above all else, stay truthful when writing your autobiography, both when you’re writing about sensitive topics and even when you’re not. While it can be tempting to bend the facts so that your audience sees you in a more positive light, maintaining honesty is the best thing you can do for yourself.

Editing and Revising Your Autobiography

Your initial draft is finished, but the job isn’t done yet. Editing and revising your autobiography can feel like a daunting task, but it’s essential for creating a polished final product.

The Importance of Self-Editing

You may feel that you have written your autobiography perfectly the first time, but there are always ways to make it better. The beauty of self-editing lies in refining your story to make sure it resonates with readers. You’re not just fixing typos or grammar mistakes; you’re looking at structure, flow, and consistency. Essentially you’re asking yourself: does this piece tell my life story in an engaging way?

Inviting Feedback from Others

No matter how meticulous we are as writers, our own work can sometimes evade us. Inviting feedback from others is invaluable during the revision process. They provide fresh eyes that can spot inconsistencies or confusing parts that may have slipped past us.

Hiring a Professional Editor

If you’re serious about publishing your autobiography and making an impact with your words, hiring a professional editor can be worth its weight in gold. An editor won’t just fix errors—they’ll help streamline sentences and enhance readability while respecting your unique voice.

Remember to approach editing and revising with patience—it’s part of the writing journey. Don’t rush through it; give each word careful consideration before moving onto publication options for your autobiography.

Free Download: 6 Proven Steps to Book More Paid Speaking Gigs in 2024

Download our 18-page guide and start booking more paid speaking gigs today!

Publishing Options for Your Autobiography

Once you’ve spent time and energy creating your autobiography, the following challenge is to make it available for others. But don’t fret! There are numerous options available for releasing your work.

Traditional Publishing Houses

A conventional path many authors take is partnering with a traditional publishing house . These industry giants have extensive resources and networks that can help boost the visibility of your book. The process may be competitive, but if accepted, they handle everything from design to distribution—letting you focus on what matters most: telling your story.

Self-Publishing Platforms

If you want more control over every aspect of publication or seek a faster route to market, self-publishing platforms like Amazon Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP), offer an accessible alternative. With this option, you manage all aspects including cover design and pricing ; however, it also means greater responsibility in promoting your book.

Bear in mind that both options have their own pros and cons, so consider them carefully before making any decisions.

Marketing Your Autobiography

Now that you’ve crafted your autobiography, it’s time to get the word out. You need a plan and strategy.

Leveraging Social Media

To start with, use your social platforms as launching pads for your book. Sites like Facebook , Twitter, and especially LinkedIn can help generate buzz about your work. And don’t underestimate the power of other platforms like Instagram and TikTok when trying to reach younger audiences. Whatever social platform you use, remember to engage with followers by responding to comments and questions about the book.

Organizing Book Signings

A physical event like a book signing not only provides readers with a personal connection but also generates local publicity. Consider partnering up with local independent stores or libraries, which are often open to hosting such events.

Securing Media Coverage

Contacting local newspapers, radio stations or even bloggers and podcasters in your field can provide much-needed visibility for your work. It might seem intimidating at first, but who better than you knows how important this story is?

FAQs on How to Write an Autobiography

How do i start an autobiography about myself.

To kick off your autobiography, jot down significant life events and pick a unique angle that frames your story differently.

What are the 7 steps in writing an autobiography?

The seven steps are: understanding what an autobiography is, planning it out, using engaging writing techniques, structuring it effectively, considering ethics, revising thoroughly, and exploring publishing options.

What are the 3 parts of an autobiography?

An autobiography generally has three parts: introduction (your background), body (major life events), and conclusion (reflections on your journey).

What is the format for writing an autobiography?

The usual format for autobiographies involves chronological or thematic structure with clear chapters marking distinct phases of life.

Writing an autobiography is a journey, a trek exploring the unique narrative of your life. Together, we’ve covered how to plan effectively, select key events, and set timelines.

Once you’re all set to write, you now have the techniques you need for engaging storytelling, including vivid descriptions and dialogues. You also learned about structuring your story for maximum impact and navigating sensitive topics while maintaining honesty.

Last but not least, you learned editing strategies, publishing options, and effective ways of promoting your book.

Now you know more than just how to write an autobiography. You know how to craft a legacy worth reading!

- Last Updated: March 22, 2024

Explore Related Resources

Learn How You Could Get Your First (Or Next) Paid Speaking Gig In 90 Days or Less

We receive thousands of applications every day, but we only work with the top 5% of speakers .

Book a call with our team to get started — you’ll learn why the vast majority of our students get a paid speaking gig within 90 days of finishing our program .

If you’re ready to control your schedule, grow your income, and make an impact in the world – it’s time to take the first step. Book a FREE consulting call and let’s get you Booked and Paid to Speak ® .

About The Speaker Lab

We teach speakers how to consistently get booked and paid to speak. Since 2015, we’ve helped thousands of speakers find clarity, confidence, and a clear path to make an impact.

Get Started

Let's connect.

Copyright ©2023 The Speaker Lab. All rights reserved.

What Is an Autobiography?

What to Consider Before You Start to Write

- Writing Research Papers

- Writing Essays

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

Your life story, or autobiography , should contain the basic framework that any essay should have, with four basic elements. Begin with an introduction that includes a thesis statement , followed by a body containing at least several paragraphs , if not several chapters. To complete the autobiography, you'll need a strong conclusion , all the while crafting an interesting narrative with a theme.

Did You Know?

The word autobiography literally means SELF (auto), LIFE (bio), WRITING (graph). Or, in other words, an autobiography is the story of someone's life written or otherwise told by that person.

When writing your autobiography, find out what makes your family or your experience unique and build a narrative around that. Doing some research and taking detailed notes can help you discover the essence of what your narrative should be and craft a story that others will want to read.

Research Your Background

Just like the biography of a famous person, your autobiography should include things like the time and place of your birth, an overview of your personality, your likes and dislikes, and the special events that shaped your life. Your first step is to gather background detail. Some things to consider:

- What is interesting about the region where you were born?

- How does your family history relate to the history of that region?

- Did your family come to that region for a reason?

It might be tempting to start your story with "I was born in Dayton, Ohio...," but that is not really where your story begins. It's better to start with an experience. You may wish to start with something like why you were born where you were and how your family's experience led to your birth. If your narrative centers more around a pivotal moment in your life, give the reader a glimpse into that moment. Think about how your favorite movie or novel begins, and look for inspiration from other stories when thinking about how to start your own.

Think About Your Childhood

You may not have had the most interesting childhood in the world, but everyone has had a few memorable experiences. Highlight the best parts when you can. If you live in a big city, for instance, you should realize that many people who grew up in the country have never ridden a subway, walked to school, ridden in a taxi, or walked to a store a few blocks away.

On the other hand, if you grew up in the country you should consider that many people who grew up in the suburbs or inner city have never eaten food straight from a garden, camped in their backyards, fed chickens on a working farm, watched their parents canning food, or been to a county fair or a small-town festival.

Something about your childhood will always seem unique to others. You just have to step outside your life for a moment and address the readers as if they knew nothing about your region and culture. Pick moments that will best illustrate the goal of your narrative, and symbolism within your life.

Consider Your Culture

Your culture is your overall way of life , including the customs that come from your family's values and beliefs. Culture includes the holidays you observe, the customs you practice, the foods you eat, the clothes you wear, the games you play, the special phrases you use, the language you speak, and the rituals you practice.

As you write your autobiography, think about the ways that your family celebrated or observed certain days, events, and months, and tell your audience about special moments. Consider these questions:

- What was the most special gift you ever received? What was the event or occasion surrounding that gift?

- Is there a certain food that you identify with a certain day of the year?

- Is there an outfit that you wear only during a special event?

Think honestly about your experiences, too. Don't just focus on the best parts of your memories; think about the details within those times. While Christmas morning may be a magical memory, you might also consider the scene around you. Include details like your mother making breakfast, your father spilling his coffee, someone upset over relatives coming into town, and other small details like that. Understanding the full experience of positives and negatives helps you paint a better picture for the reader and lead to a stronger and more interesting narrative. Learn to tie together all the interesting elements of your life story and craft them into an engaging essay.

Establish the Theme

Once you have taken a look at your own life from an outsider’s point of view, you will be able to select the most interesting elements from your notes to establish a theme. What was the most interesting thing you came up with in your research? Was it the history of your family and your region? Here is an example of how you can turn that into a theme:

"Today, the plains and low hills of southeastern Ohio make the perfect setting for large cracker box-shaped farmhouses surrounded by miles of corn rows. Many of the farming families in this region descended from the Irish settlers who came rolling in on covered wagons in the 1830s to find work building canals and railways. My ancestors were among those settlers."

A little bit of research can make your own personal story come to life as a part of history, and historical details can help a reader better understand your unique situation. In the body of your narrative, you can explain how your family’s favorite meals, holiday celebrations, and work habits relate to Ohio history.

One Day as a Theme

You also can take an ordinary day in your life and turn it into a theme. Think about the routines you followed as a child and as an adult. Even a mundane activity like household chores can be a source of inspiration.

For example, if you grew up on a farm, you know the difference between the smell of hay and wheat, and certainly that of pig manure and cow manure—because you had to shovel one or all of these at some point. City people probably don’t even know there is a difference. Describing the subtle differences of each and comparing the scents to other scents can help the reader imagine the situation more clearly.

If you grew up in the city, you how the personality of the city changes from day to night because you probably had to walk to most places. You know the electricity-charged atmosphere of the daylight hours when the streets bustle with people and the mystery of the night when the shops are closed and the streets are quiet.

Think about the smells and sounds you experienced as you went through an ordinary day and explain how that day relates to your life experience in your county or your city:

"Most people don’t think of spiders when they bite into a tomato, but I do. Growing up in southern Ohio, I spent many summer afternoons picking baskets of tomatoes that would be canned or frozen and preserved for cold winter’s dinners. I loved the results of my labors, but I’ll never forget the sight of the enormous, black and white, scary-looking spiders that lived in the plants and created zigzag designs on their webs. In fact, those spiders, with their artistic web creations, inspired my interest in bugs and shaped my career in science."

One Event as a Theme

Perhaps one event or one day of your life made such a big impact that it could be used as a theme. The end or beginning of the life of another can affect our thoughts and actions for a long time:

"I was 12 years old when my mother passed away. By the time I was 15, I had become an expert in dodging bill collectors, recycling hand-me-down jeans, and stretching a single meal’s worth of ground beef into two family dinners. Although I was a child when I lost my mother, I was never able to mourn or to let myself become too absorbed in thoughts of personal loss. The fortitude I developed at a young age was the driving force that would see me through many other challenges."

Writing the Essay

Whether you determine that your life story is best summed up by a single event, a single characteristic, or a single day, you can use that one element as a theme . You will define this theme in your introductory paragraph .

Create an outline with several events or activities that relate back to your central theme and turn those into subtopics (body paragraphs) of your story. Finally, tie up all your experiences in a summary that restates and explains the overriding theme of your life.

- 4 Teaching Philosophy Statement Examples

- How to Write a Personal Narrative

- How to Write a Narrative Essay or Speech

- The Law School Applicant’s Guide to the Diversity Statement

- Tips for Writing a "What I Did on Vacation" Essay

- Compose a Narrative Essay or Personal Statement

- The Power of Literacy Narratives

- Memorable Graduation Speech Themes

- FAQs About Writing Your Graduate Admissions Essay

- 7 Tips for Writing Personality Profiles That People Will Want to Read

- Personal Essay Topics

- Writing Prompts for 5th Grade

- Engaging Writing Prompts for 3rd Graders

- Common Application Essay, Option 1: Share Your Story

- What Are the Parts of a Short Story? (How to Write Them)

- 4th Grade Writing Prompts

Autobiography

Definition of autobiography.

Autobiography is one type of biography , which tells the life story of its author, meaning it is a written record of the author’s life. Rather than being written by somebody else, an autobiography comes through the person’s own pen, in his own words. Some autobiographies are written in the form of a fictional tale; as novels or stories that closely mirror events from the author’s real life. Such stories include Charles Dickens ’ David Copperfield and J.D Salinger’s The Catcher in The Rye . In writing about personal experience, one discovers himself. Therefore, it is not merely a collection of anecdotes – it is a revelation to the readers about the author’s self-discovery.

Difference between Autobiography and Memoir

In an autobiography, the author attempts to capture important elements of his life. He not only deals with his career, and growth as a person, he also uses emotions and facts related to family life, relationships, education, travels, sexuality, and any types of inner struggles. A memoir is a record of memories and particular events that have taken place in the author’s life. In fact, it is the telling of a story or an event from his life; an account that does not tell the full record of a life.

Six Types of Autobiography

There are six types of autobiographies:

- Autobiography: A personal account that a person writes himself/herself.

- Memoir : An account of one’s memory.

- Reflective Essay : One’s thoughts about something.

- Confession: An account of one’s wrong or right doings.

- Monologue : An address of one’s thoughts to some audience or interlocuters.

- Biography : An account of the life of other persons written by someone else.

Importance of Autobiography

Autobiography is a significant genre in literature. Its significance or importance lies in authenticity, veracity, and personal testimonies. The reason is that people write about challenges they encounter in their life and the ways to tackle them. This shows the veracity and authenticity that is required of a piece of writing to make it eloquent, persuasive, and convincing.

Examples of Autobiography in Literature

Example #1: the box: tales from the darkroom by gunter grass.

A noble laureate and novelist, Gunter Grass , has shown a new perspective of self-examination by mixing up his quilt of fictionalized approach in his autobiographical book, “The Box: Tales from the Darkroom.” Adopting the individual point of view of each of his children, Grass narrates what his children think about him as their father and a writer. Though it is really an experimental approach, due to Grass’ linguistic creativity and dexterity, it gains an enthralling momentum.

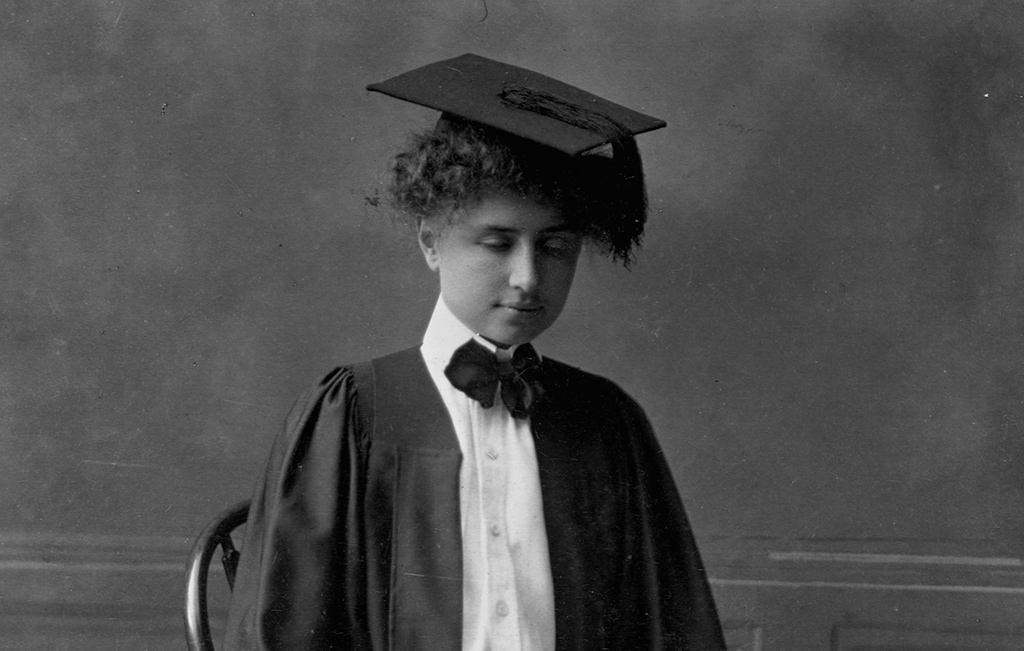

Example #2: The Story of My Life by Helen Keller

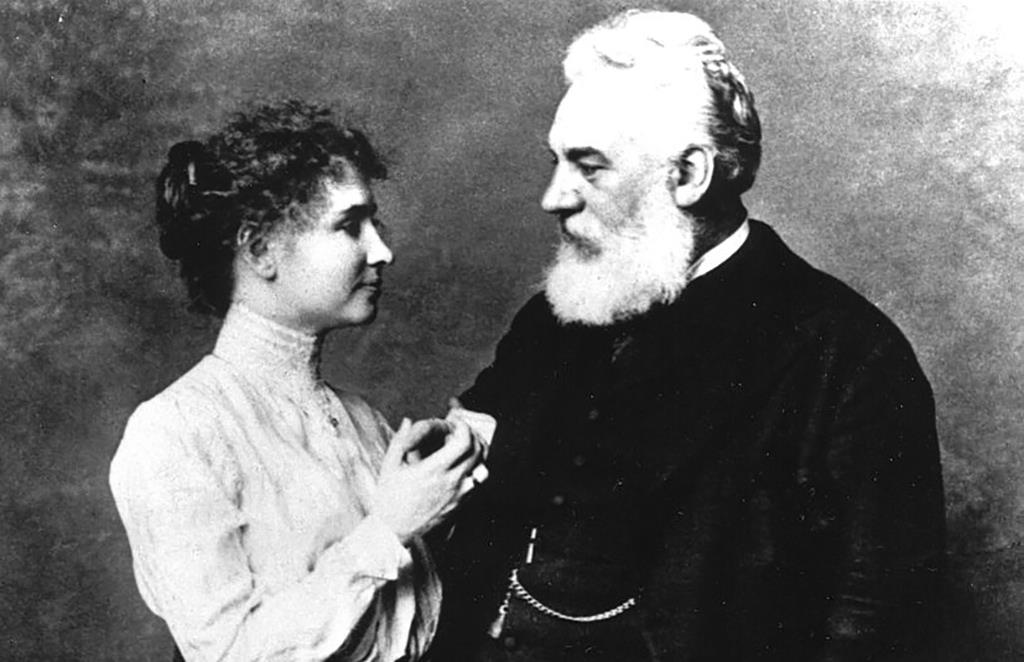

In her autobiography, The Story of My Life , Helen Keller recounts her first twenty years, beginning with the events of the childhood illness that left her deaf and blind. In her childhood, a writer sent her a letter and prophesied, “Someday you will write a great story out of your own head that will be a comfort and help to many.”

In this book, Keller mentions prominent historical personalities, such as Alexander Graham Bell, whom she met at the age of six, and with whom she remained friends for several years. Keller paid a visit to John Greenleaf Whittier , a famous American poet, and shared correspondence with other eminent figures, including Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Mrs. Grover Cleveland. Generally, Keller’s autobiography is about overcoming great obstacles through hard work and pain.

Example #3: Self Portraits: Fictions by Frederic Tuten

In his autobiography, “Self Portraits: Fictions ,” Frederic Tuten has combined the fringes of romantic life with reality. Like postmodern writers, such as Jorge Luis Borges, and Italo Calvino, the stories of Tuten skip between truth and imagination, time and place, without warning. He has done the same with his autobiography, where readers are eager to move through fanciful stories about train rides, circus bears, and secrets to a happy marriage; all of which give readers glimpses of the real man.

Example #4: My Prizes by Thomas Bernhard

Reliving the success of his literary career through the lens of the many prizes he has received, Thomas Bernhard presents a sarcastic commentary in his autobiography, “My Prizes.” Bernhard, in fact, has taken a few things too seriously. Rather, he has viewed his life as a farcical theatrical drama unfolding around him. Although Bernhard is happy with the lifestyle and prestige of being an author, his blasé attitude and scathing wit make this recollection more charmingly dissident and hilarious.

Example #5: The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin by Benjamin Franklin

“The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin ” is written by one of the founding fathers of the United States. This book reveals Franklin’s youth, his ideas, and his days of adversity and prosperity. He is one of the best examples of living the American dream – sharing the idea that one can gain financial independence, and reach a prosperous life through hard work.

Through autobiography, authors can speak directly to their readers, and to their descendants. The function of the autobiography is to leave a legacy for its readers. By writing an autobiography, the individual shares his triumphs and defeats, and lessons learned, allowing readers to relate and feel motivated by inspirational stories. Life stories bridge the gap between peoples of differing ages and backgrounds, forging connections between old and new generations.

Synonyms of Autobiography

The following words are close synonyms of autobiography such as life story, personal account, personal history, diary, journal, biography, or memoir.

Related posts:

- The Autobiography of Malcolm X

Post navigation

- L omas E ditorial

- Autobiographies and Memoirs

- Mental health memoirs

- Agents and Publishers

- Client testimonials

Lomas E ditorial

Ghostwriting, editing and mentoring for writers

How to structure an autobiography to make it readable

Writing your autobiography might feel like it should be the most intuitive thing you’ll ever do. You lived through those experiences, and you know those stories so well. And yet, far too many would-be autobiography writers fall at the first hurdle. Even though they know broadly what they want to say, they never quite work out what to write about in an autobiography.

So, in this article, I want to give you the resources and insight you need to write an autobiography or biography. You’ll see how getting the structure of an autobiography right is key to telling your story effectively and interestingly.

How do you know what to write about in an autobiography? The accumulated stories of your life could probably fill a dozen books. So how do you cram it all into a single volume?

If you want to write a book that focusses in greater detail on a few elements of your life, you should write a memoir . From collections of stories about family or work to stories of struggle and survival, the memoir is the perfect vehicle for books with a smaller remit.

But in this article, we’re focussing on how to write an interesting autobiography, which is a more detailed process. We’re going to break it down into three parts:

- What to write about in an autobiography

The structure of a biography or autobiography

- How to write an interesting autobiography

The good news is that when you know what to write about in an autobiography, it will help you establish a lot about the structure of your autobiography. And, when you’ve got those two things ticked off, you’ll find it significantly easier to write an interesting autobiography.

How do you decide what to write about in an autobiography?

Start by making a long list of the things you could write about in your autobiography. Make your list roughly chronological so that you can see how the incidents connect in your personal timeline. Write anything and everything down at this stage.

I suggest you keep working on your list for several weeks. The more you think about it, and the more often you return to it, the easier it will be to extract every possible story you might want to tell. When you have a comprehensive list, I’d leave it a little longer before you take your next step. Go back to your list days (or even weeks) later and look for clues as to how you can tell your story:

- See if there are there any common themes that bind some of your stories together. It’s easier to build a book if the stories naturally coalesce around a single idea or theme.

- Think about your life’s journey and look for narrative threads that help you tell that story.

- Look for any stories that give the most authentic sense of who you are, and how you want to be remembered.

- Look for – and remove – any stories that don’t feel interesting or relevant.

It’s not just a question of what to write about in an autobiography, you need to consider what not to write about

Given that a biography or autobiography encompasses a whole lifetime of activities, you need to decide what makes the grade in your story and what doesn’t. Knowing who’s going to read your book will help you make the right decisions.

Are you writing your book for family and friends? For a business audience? For a cohort of people who have encountered similar life issues? Keep that audience in mind at all times? Write with them in mind.

If you’re not sure what deserves a place in your autobiography, just picture your readers and ask yourself these questions:

Will this part of my story genuinely interest my readers?

Does this material add anything meaningful to the story I’m telling?

Am I comfortable telling this part of my story?

If the answer to any of these questions is ‘no’ it doesn’t belong in your book.

Distilling your life into the stories that will survive you

If you’re struggling to home in on the events you want to focus on in your autobiography, it might help you to remember that this book will survive you.

The stories you tell will still be there for people to read about years from now. That can help you to home in on the things that really matter; the things that will define the life you’ve lived.

Some people find the easiest way to distil their life story into a cohesive narrative is to write more than they need, and edit out material at the end of the process. That takes a bit more work, but when you can see the whole story written down, it’s generally easier to identify what really belongs in your book, and what doesn’t.

Think carefully about the audience for your book

This question of what to write about in an autobiography gets easier the closer you get to your intended audience.

Run though that list of stories for possible inclusion in your book and see if any of them jump out as being particularly interesting or appropriate for your audience. Equally, there may be some stories that will need to justify their inclusion. For example,

- Will your family be interested in lots of stories from your work life?

- Will a wider audience of people reading your survival-against-the-odds story want to know about your life now? Perhaps, if that gives them hope for their own future.

- Will your children want to know about some of your less savoury stories? They might well do (when they reach an appropriate age) if you present them in a way that will amuse and / or give them the benefit of your reflections on those events.

- Are you comfortable telling certain stories if they’re controversial in your family? Will telling them pour oil on troubled waters or make matters worse?

Don’t just think about what your readers will be interested in now, think about what might interest them in the future. For example, if you’re writing an autobiography for your children (or grandchildren) there will be insights, stories and reflections that will mean more to them as time passes.

If I were writing my autobiography for my (now) teenage children, I know they’d be interested to read my stories of their childhood escapades. And, as time goes on, and they grow up and potentially have their own children, they’ll probably be even more interested to read about my reflections on being a parent.

In other words, there will be a point when your experiences and theirs match. When what you have to say on any given subject might suddenly feel very relevant. So, try and write an autobiography that will stay relevant to your audience.

If you take nothing else from this article, the single most important lesson for how to write an interesting autobiography is this:

Your autobiography can – and should – obey many of the same rules as fiction.

Just because you’re telling a real story, as opposed to a work of fiction, the same elements of structure, tension and release, and story arc will make your book richer and more engaging.

Let’s discuss the actual section-by-section, chapter-by-chapter structure of your book.

When we talk about structure in books, we’re essentially talking about giving your book a beginning, a middle and an end, and about the chapters that fit within that structure.

We’re also talking about making sure your book progresses organically from event to event. Your reader needs to feel like your book is heading somewhere; it flows.

Try a three-act structure

You certainly don’t have to stick to some rigid structure, but it can help to think of your story like a three-act drama. An example of a simple three-act structure for a biography or autobiography would comprise a beginning, concentrating on the early years of your life, a middle featuring the bulk of the events you want to cover, and an end which brings all of the threads of the story together.

You certainly don’t have to divide your book into three parts. But having the idea of a three-act structure in mind can help you to simplify your storytelling.

Remember that the structure could be thematic, rather than chronological. For example, the introductory stage could be meeting the love of your life, the body of the book could be about your life together, and the concluding section could focus on how your family has grown.

Or, the introductory chapter could focus on the emergence of a great difficulty in your life. The second section would focus on your dealing with it. The third section could illustrate how you overcame it and what you learnt from it.

Break the structure

One of the best things about the ‘rules’ governing the structure of a biography or autobiography is that they are there to be broken…

Just because you adopt a three-act structure, it doesn’t mean you have to start your autobiography at the beginning. It can be very effective – and dramatically justified – to start your story at the end.

Or, you can apply a structure, but still break it up with interludes, diversions, and lists that add supplementary information or insights. A couple of examples:

In a book for a client who had travelled extensively, we devised funny little Trip Advisor style summaries of some of her travel destinations, and interspersed them throughout the book.

A fan of the weird and uncanny who had collected stories of some of life’s stranger happenings included them as an interlude in his book, giving readers enough information to go and pursue their own research into any of the stories that interested them.

Take the reader on a journey

Great books – whether they’re narrative non-fiction or fiction – take their readers on a journey. So, rather than simply chronicling the events of your life, you can find a narrative thread to resemble a hero’s journey narrative, or other dramatic form.

Let’s take a closer look at how you can do that…

Find the thread that binds your story together

Make a chronological list of the major (and interesting or exciting) events of your life. Look at your list and ask some questions to help you find the thread that binds your story together:

- How did you get from your childhood to where you are now?

- What were the turning points or moments of crisis along the way?

- Who were the people who helped or hindered you in your journey?

- What are the things in your past that suggested where you were going in the future?

- How did you realise your childhood or youthful dreams?

- How did you overcome a significant adversity in life?

Finding an appropriate story thread makes writing your autobiography significantly easier. You give yourself a set up, a complication or crisis, and a resolution – all essential components of an interesting and well-told story.

One of the hardest parts of writing an autobiography for many people is having far too much information to include and not knowing what to exclude. Working this way helps you to eliminate all of the material that doesn’t contribute to the main storyline.

Think of it like telling the story of a football match that focusses on the actions of a single player. Your reader would still understand the outcome of the match. They’ll still understand how that player interacted with their teammates, and came into conflict with other players. They won’t get a full match report, but they will get a very focussed story of the game from one angle.

Use your chapters to help you write an interesting autobiography

The way you divide your story into chapters is another way of injecting interest into your autobiography. Whether using cliffhangers to keep readers hanging on to see what happens next, or using chapter breaks to signal changes in tone, your chapters are a useful resource.

In terms of structure, remember that each chapter should be like a scene in a film. They should advance your story in some way, and tell a self-contained piece of the story. If you’re telling a part of the story that requires more space than other parts of your story consider splitting your chapter at a critical moment to create your dramatic cliffhanger ending.

You can do interesting things to the structure of your book with your use of chapters. An incredibly short chapter could be an amusing way of skipping over a part of your story that you don’t want to tell, but that you know people are expecting to read about, e.g.

Reader, I married him.

Spoiler alert. It went really badly, really quickly!

Have fun with your chapters. From the way you name them, to the quotes you use to add interest, to the way you format them, all these things can help make your autobiography more interesting and distinctive.

If you’d like to know more, have a look at this article on chapters , covering the optimal length of chapters, when to use chapter breaks, and the issue of how you can use chapters to help you structure your biography or autobiography.

How to write an interesting autobiography? Remember that the principles of telling a traditional story apply

There’s plenty more you can do to keep things interesting for your readers. Remember that, just like fiction, a compelling autobiography will:

Provide good introductions for all the major characters

You don’t have to talk about everyone you reference in depth, but when it comes to the key players in your life story, make sure you introduce them properly.

Hinge on moments of tension and release

This is the basis of all good drama. Even if you have not lived a life of ‘high drama’ that doesn’t mean dramatic, momentous, stressful, or important things haven’t happened to you. And these are all potential sources of drama.

Be truthful

It’s easy to exaggerate our achievements and nobody will object to you using a bit of dramatic license now and then, However, the more honest and truthful your book is, the more powerful it will be.

Tie it all up at the end

In this article, we’ve covered the three areas of 1) what to write about in an autobiography, 2) the structure of a biography or autobiography, and 3) how to write an interesting autobiography. We introduced the subject in broad terms, then drilled down into more detail on each subject, much like you might do in your autobiography.

By this stage, you’ll have a better understanding of how you can write your autobiography in a way that does justice to the life you’ve lived. I hope you find that, as a result, writing your autobiography feels more intuitive.

I’m here to help you edit your autobiography , or you can hire me as a writing mentor . Or, if you’d like me to ghostwrite your life story for you, book a ghostwriting consultation and we’ll talk it over…

Photo by UX Indonesia on Unsplash

Become a subscriber

Join my mailing list and I'll periodically send a round-up of new posts, new book releases that I've worked on (where I'm able to disclose such things) and any other news, offers etc., that you might find interesting or useful.

I consent to my data being used as outlined in the privacy policy

Any other questions?

If you’re considering partnering with a ghostwriter, editor, or writing mentor, then you’re bound to have a few questions.

From process to publishing options, via pricing, I’ve compiled a few FAQs for you. For anything else, please feel free to get in touch for a friendly, no-obligation chat.

Become a Bestseller

Follow our 5-step publishing path.

Fundamentals of Fiction & Story

Bring your story to life with a proven plan.

Market Your Book

Learn how to sell more copies.

Edit Your Book

Get professional editing support.

Author Advantage Accelerator Nonfiction

Grow your business, authority, and income.

Author Advantage Accelerator Fiction

Become a full-time fiction author.

Author Accelerator Elite

Take the fast-track to publishing success.

Take the Quiz

Let us pair you with the right fit.

Free Copy of Published.

Book title generator, nonfiction outline template, writing software quiz, book royalties calculator.

Learn how to write your book

Learn how to edit your book

Learn how to self-publish your book

Learn how to sell more books

Learn how to grow your business

Learn about self-help books

Learn about nonfiction writing

Learn about fiction writing

How to Get An ISBN Number

A Beginner’s Guide to Self-Publishing

How Much Do Self-Published Authors Make on Amazon?

Book Template: 9 Free Layouts

How to Write a Book in 12 Steps

The 15 Best Book Writing Software Tools

What is an Autobiography? Definition, Elements, and Writing Tips

POSTED ON Oct 1, 2023

Written by Audrey Hirschberger

What is an autobiography, and how do you define autobiography, exactly? If you’re hoping to write an autobiography, it’s an important thing to know. After all, you wouldn’t want to mislabel your book.

What sets an autobiography apart from a memoir or a biography? And what type of writing is most similar to an autobiography? Should you even write one? How? Today we will be discussing all things autobiographical, so you can learn what an autobiography is, what sets it apart, and how to write one of your own – should you so choose.

But before we get into writing tips, we must first define autobiography. So what is an autobiography, precisely?

Need A Nonfiction Book Outline?

This Guide to Autobiographies Contains Information On:

What is an autobiography: autobiography meaning defined.

What is an autobiography? It’s a firsthand recounting of an author’s own life. So, if you were to write an autobiography, you would be writing a true retelling of your own life events.

Autobiography cannot be bound to only one type of work. What an autobiography is has more to do with the contents than the format. For example, autobiographical works can include letters, diaries, journals, or books – and may not have even been meant for publication.

An autobiography is what many celebrities, government officials, and important social figures sit down to write at the end of their lives or distinguished careers.

Of course, the work doesn’t have to cover your whole life. You can absolutely write an autobiography in your 20s or 30s if you’ve lived through events worth sharing!

If an autobiography doesn’t cover the entire lifespan of the author, it can start to get confused with another genre of writing. So what’s an autobiography most similar to? And how can you tell it apart from other genres of writing? Let’s dive into the details.

What type of writing is most similar to an autobiography?

A memoir is undoubtedly what type of writing is most similar to an autobiography. So what is the difference between an autobiography vs memoir ?

Simply put, a memoir is a book that an author writes about their own life with the intention of communicating a lesson or message to the reader. It doesn’t need to be written in chronological order, and only contains pieces of the author’s life story.

An autobiography, on the other hand, is the author’s life story from birth to present, and it’s much less concerned with theme than it is with communicating a “highlight reel” of the author’s biggest life events.

In addition to memoirs, there is also some confusion between autobiography vs biography . A biography is a true story about someone’s life, but it is not about the author’s life.

Is an autobiography always nonfiction?

When many people define autobiography, they say it is a true or “nonfiction” telling of an author’s life – but that’s not always the case.

There is actually such a thing as autobiographical fiction .

Autobiographical fiction refers to a story that is based on fact and inspired by the author’s actual experiences…but has made-up characters or events. Any element in the story can be embellished upon or fabricated.

Even the information in a standard “nonfiction” autobiography should be taken with a grain of salt. After all, anything written from the author’s perspective may contain certain biases, distortions, or unconscious omissions within the text.

So if being nonfiction isn’t a defining characteristic of an autobiography, what is an autobiography defined by?

The key elements of an autobiography

What’s an autobiography like from cover to cover? It should contain these key elements:

- A personal narrative : It is a firsthand account of the author's life experiences.

- A chronological structure : An autobiography typically follows a chronological order, tracing the author's life from birth to present.

- Reflection and insight : The book should contain the author's reflections, insights, and emotions about key life events.

- Key life events : The book should highlight significant events, milestones, and challenges in the author's life.

- Setting and context : There should be descriptions of the time period, cultural background, and environment to help the reader understand the author’s life.

- Authenticity : The author should be honest and sincere in presenting their life story.

- A personal perspective : An autobiography is written from the author's unique point of view.

- A strong conclusion : The ending of the book should reflect on the author's current state or outlook.

Famous Autobiography Examples

Now that you know what an autobiography is, let’s look at some famous autobiography examples .

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank (1947)

Perhaps no autobiography is more famous than The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank. Her diary chronicles her profound thoughts, dreams, and fears as she hides with her family in the walls during the Holocaust.

Anne's words resonate with the enduring spirit of hope amid unimaginable darkness.

The Autobiography of Ben Franklin by Benjamin Franklin (1909)

Benjamin Franklin's autobiography follows Franklin’s life from humble origins to one of America's greatest forefathers. While originally intended as a collection of anecdotes for his son, this autobiography has become one of the most famous works of American literature.

Long Walk to Freedom by Nelson Mandela (1994)

Long Walk to Freedom narrates Nelson Mandela's epic odyssey from South African prisoner to revered statesman. This masterpiece of an autobiography is a portrait of resilience against the backdrop of apartheid – and his words are a bastion for courage and human rights.

Now you know what an autobiography is, and some examples of successful autobiographies, so it’s time to discuss what goes into actually writing one.

Who Should Write an Autobiography?

Celebrity autobiographies are popular for a reason – the people who wrote them were already popular.

The main purpose of an autobiography is to portray the life experiences and achievements of the author. If you haven’t made any massive achievements that people are already aware of, an autobiography might not be for you. Instead, you should learn how to write a memoir .

After all, what’s an autobiography worth if no one reads it?

If you have made an important contribution to society, or have amassed a massive following of fans, then writing an autobiography could be a fabulous idea.

An autobiography is what allows you to claim your rightful place in history. It provides a legacy for your life, helps you to better understand your life’s journey, and can even be deeply therapeutic to write.

But then comes the next problem: how to write an autobiography.

Tips on Writing Your Own Autobiography

While memoirs are the books that teach life lessons, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t give your autobiography meaning. The best autobiographies paint a vivid tapestry of personal growth and introspection.

You don’t just want to tell the reader about your life – you want them to feel like they are living it with you.

And it’s not just about painting a picture with your prose. A lot of thought should go into everything from autobiography titles to page count. To get started, here are five tips for writing an autobiography:

- Know your audience : Understand who will read your autobiography and speak to them while writing.

- Be candid and authentic : A life seen through rose-colored glasses isn’t relatable. You should include your failures as well as your triumphs, and humanize yourself so your story resonates with your reader.

- Do your research : Of course you know what happened in your life, but how many details do you actually remember? You may need to sift through photos, archives, and diaries – and interview people close to you. Consider adding the photos to your book.

- Identify key themes : Identify key events and life lessons that have shaped you. Reflect on how these themes have evolved over time.

- Edit and edit again : Write freely first, then edit rigorously. Seek feedback from trusted individuals and consider professional editing to ensure clarity and coherence in your narrative. NO ONE writes perfectly the first time.

So there you have it, you are well on your way to understanding (and writing) an autobiography.

If you'd still like more guidance for writing your autobiography, you can check out our free autobiography template . We can’t wait for you to share your life story with the world.

Related posts

Non-Fiction

Elite Author Lisa Bray Reawakens the American Dream in Her Debut Business Book

Elite author, david libby asks the hard questions in his new book, elite author, kyle collins shares principles to help you get unstuck in his first book.

How to write an Autobiography

A Complete Guide to Writing an Autobiography

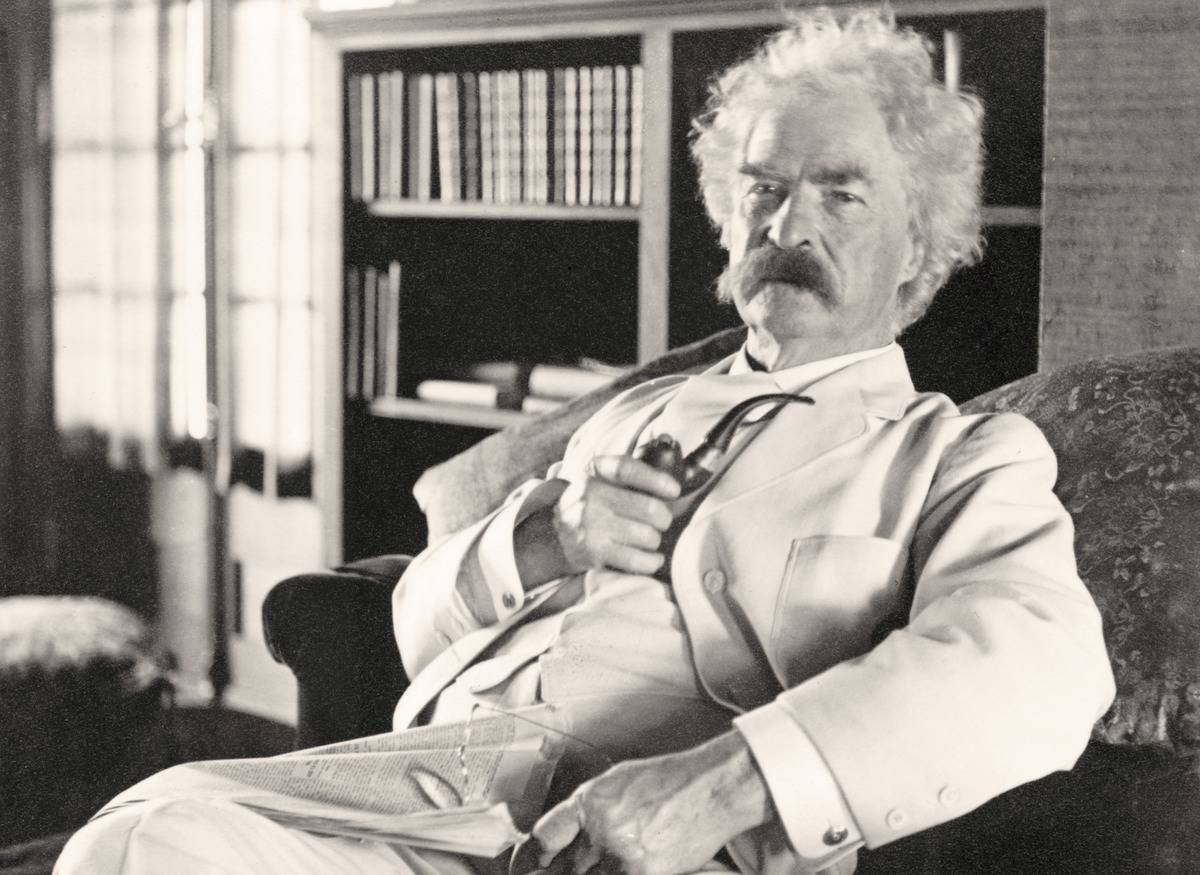

A quick scan of the bestseller lists will quickly reveal that we are obsessed with the lives of other people.

Books by and about actors, politicians, and sports stars regularly top the charts as we seek to catch a glimpse into the lives of remarkable people.

While many of these books are written by professional writers after meticulous research ( biographies ), just as many are written by the person themselves (autobiographies) – albeit often with a ghostwriter’s help.

Today we are going to show you how to write an autobiography that tells a great life story.

WHAT IS AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY?

Autobiography is a subcategory of the biography genre and, strictly speaking, it’s a life story written by the subject themselves.

Autobiographies are sometimes confused with memoirs and it’s no surprise as the two share many features in common. For example, both are written in the first person and contain details of the subject’s life.

However, some clear distinctions can be made between the two.

For example, a memoir usually explores a specific period of a person’s life, whereas an autobiography tends to make an account of the person’s life from their earliest years right up to the time of writing.

Autobiographies aren’t just the preserve of the celebrities among us though, each of our lives is a story in and of itself. Whether or not it’s a good story will depend largely on the telling, which is what this article is all about.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING BIOGRAPHIES

Teach your students to write AMAZING BIOGRAPHIES & AUTOBIOGRAPHIES using proven RESEARCH SKILLS and WRITING STRATEGIES .

- Understand the purpose of both forms of biography.

- Explore the language and perspective of both.

- Prompts and Challenges to engage students in writing a biography.

- Dedicated lessons for both forms of biography.

- Biographical Projects can expand students’ understanding of reading and writing a biography.

- A COMPLETE 82-PAGE UNIT – NO PREPARATION REQUIRED.

WHAT ARE THE MAIN FEATURES OF AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY?

Once students have a good grasp of what an autobiography is, we need to ensure they are familiar with the main features of the genre before they begin writing.

Let’s take a look at some of the main technical elements of an autobiography:

Purpose of an Autobiography:

To give an account of the person’s life so far

Tense: Mostly written in the past tense, but usually ends in the present tense and sometimes shifts into the future tense at the very end.

Structure of an Autobiography:

● Usually written in chronological order

● Uses time connectives such as before, then, after that, finally, etc

● Uses the names of real people and events

● Is specific about times, dates, places, etc

● Includes personal memories and specific details and descriptions

● Reflects on how positive and negative experiences shaped the author

● Gives an insight into the thoughts, feelings, and hopes of the author

● May include some relevant photographs

● Usually ends with a commentary on life, reflections on significant large events, and hopes and plans for the future.

When teaching these specific features, you may wish to compile a checklist with the students that they can subsequently use to assist them when writing their autobiography.

PRACTICAL ACTIVITY:

One great way to help your students to internalize the main features of the genre is to encourage them to read lots of autobiographies. Instruct the students to be conscious of the different features discussed above and to identify them in the autobiography as they read.

If you have compiled a checklist together, students can check off the features they come across as they read.

When they have finished reading, students should consider which features were well done in the book and which were missing or had room for improvement.

TIPS FOR WRITING A GREAT AUTOBIOGRAPHY

As we know, there is more to a genre of writing than just ticking off the main features from a checklist.

To write well takes time and practice, as well as familiarity with the features of the genre. Each genre of writing makes different demands on our skills as a writer and autobiography are no different.

Below, we will look at a step-by-step process for how students can best approach the task of writing their autobiography, along with some helpful hints and tips to polish things up.

Let’s get started!

HOW TO START AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY WRITING TIPS:

Tip #1: brainstorm your autobiography.

The structure of an autobiography is somewhat obvious; it starts at the beginning of the subject’s life, works its way through the middle, and ends in the present day.

However, there’s a lot in a life. Some of it will be fascinating from a reader’s point of view and some of it not so much. Students will need to select which events, anecdotes, and incidents to include and which to leave out.

Before they begin this selection process in earnest, they need to dump out the possibilities onto the page through the process of brainstorming. Students should write down any ideas and sketches of memories that might be suitable onto the page.

While they needn’t write trivial memories that they know definitely won’t make the cut, they should not set the bar so high that they induce writer’s block.

They can remove the least interesting episodes when making the final selection later in the writing process. The main thing at this stage is the generation and accumulation of ideas.

TIP #2: CREATE AN OUTLINE OF YOUR AUTOBIOGRAPHY

After students have selected the most compelling episodes from their brainstorming session, they’ll need to organize them into the form of an outline.

One good way to do this is to lay them out chronologically on a simple timeline. Looking at the episodes in such a visual way can help the students to construct a narrative that leads from the student’s earliest childhood right through to the present day.

Students need to note that an autobiography isn’t just the relating of a series of life events in chronological order. They’ll need to identify themes that link the events in their autobiography together.

Themes are the threads that we weave between the cause and effect of events to bring shape and meaning to a life. They touch on the motivation behind the actions the author takes and fuel the development growth of the person.

Some themes that might be identified in an outline for an autobiography might include:

● Overcoming adversity

● Adjusting to a new life

● Dealing with loss

● The importance of friendship

● The futility of revenge

● The redemptive power of forgiveness.

These themes are the big ideas of a person’s life story. They represent how the events shape the person who is now sitting writing their story. For students to gain these insights will require the necessary time and space for some reflection.

For this reason, autobiography writing works well as a project undertaken over a longer period such as several weeks.

TIP #3: DO THE BACKGROUND RESEARCH ON YOUR AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Even though no one knows more about the topic of an autobiography than the author, research is still a necessary part of the writing process for autobiographies.

Using the outline they have created, students will need to flesh out some of the details of key events by speaking to others, especially when writing about their earliest experiences.

The most obvious resources will be parents and other family members who were privy to the joys of babyhood and their earliest childhood.

However, friends and ex-teachers make excellent sources of information too. They will enable the student to get a different perspective on something they remember, helping to create a more rounded view of past events.

For older and more advanced students, they may even wish to do some research regarding historical and cultural happenings in the wider society during the period they’re writing about. This will help to give depth and poignancy to their writing as they move up and down the ladder of abstraction from the personal to the universal and back again.

When students make the effort to draw parallels between their personal experiences and the world around them, they help to bridge the gap between author and reader creating a more intimate connection that enhances the experience for the reader.

TIP #4: FIND YOUR VOICE

Students need to be clear that autobiography is not mere personal history written dispassionately and subjectively.

For their autobiography to work, they’ll need to inject something of themselves into their writing. Readers of autobiography especially are interested in getting to know the inner workings of the writer.

There is a danger, however. Given that autobiographers are so close to their material, they must be careful not to allow their writing to denigrate into a sentimental vomit. To counter this danger, the student author needs to find a little perspective on their experiences, and following the previous tip regarding research will help greatly here.

A more daunting obstacle for the student can lie in the difficulties they face when trying to find their voice in their writing. This isn’t easy. It takes time and it takes lots of writing practice.

However, there are some simple, helpful strategies students can use to help them discover their authentic voice in their writing quickly.

1. Write to a close friend or family member

All writing is written to be read – with the possible exception of journals and diaries. The problem is that if the student is too conscious of the reader, they can find themselves playing to the audience and getting away from what it is they’re trying to express. Showboating can replace the honesty that is such a necessary part of good writing.

A useful trick to help students overcome this hurdle is to tell them to imagine they are writing their autobiography to an intimate friend or family member. Someone who makes them feel comfortable in their skin when they are around. Students should write like they’re writing to that person to who they can confide their deepest secrets. This will give their writing an honest and intimate tone that is very engaging for the reader.

2. Read the writing out loud

It’s no accident that we talk about the writer’s ‘voice’. We recognize the actual voice of people we know from its many qualities, from its timbre, tone, pacing, accent, word choice, etc. Writing is much the same in this regard.

One great way to help students detect whether their writing captures their authentic voice is to have them read it out loud, or listen to a recording of their work read out loud.

While we don’t necessarily write exactly as we speak – we have more time to craft what we say – we will still be able to recognize whether or not the writing sounds like us, or whether it’s filled with affectation.

As the student listens to their own words, encourage them to ask the following questions:

● Does this sound like me?

● Do the words sound natural in my voice?

● Do I believe in the events related and how they were related?

Finding their real voice in their writing will help students imbue their writing with honesty and personality that readers love.

TIP #5: DRAFT, REDRAFT AND REFINE YOUR AUTOBIOGRAPHY

In the first draft, the brushstrokes will be large and broad, sweeping through the key events. The main notes of the tune will be there but with sometimes too much ornamentation and, at other times, not enough. This is why redrafting is an essential part of the writing process.

Students should understand that every piece of writing needs redrafting, editing , and proofreading to be at its best. There are no masterpieces full-borne into the world in a single draft.

For many, the tightening-up of a piece will involve the merciless cutting out of dead words. But, for some, the redrafting and refining process will demand the adding of more description and detail.

For most, however, it’ll be a little from column A and a little from column B.

Often, it’s difficult for students to get the necessary perspective on their work to be able to spot structural, grammar , punctuation, and spelling errors. In these instances, it can be best to enrol the eyes of a friend or family member in the role of editor or critic.

One effective way of doing this in class is to organize the students into pairs of editing buddies who edit each other’s work in a reciprocal arrangement.

These ‘edit swaps’ can be continued through to the proofreading stage and the final, polished piece.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE

FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE is like “SPECIAL EFFECTS FOR AUTHORS.” It is a powerful tool to create VIVID IMAGERY through words. This HUGE UNIT guides you through completely understanding FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE .

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (26 Reviews)

A Final Thought

Employing the 5 tips above will go a long way to ensuring a well-written and engaging autobiography.

While autobiography is a nonfiction genre, it is clear that with its emphasis on narrative, it has much in common with other fictional genres. So, it’s important when teaching autobiography that students learn to recognize the important role of storytelling in this genre too.

As with all good story-telling, there are some necessary elements to include, including a plot of sorts, a cast of characters, and an exploration of some central themes. For this reason, teaching autobiography often works well after the students have completed a unit on fictional story writing.

When all is said and done, the best way a student can ensure their autobiography is worth a read is to ensure they find the story within their own life.

After all, we’re obsessed with the lives of other people.

ARTICLES RELATED TO HOW TO WRITE AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY

How to Write a Biography

How to Write a Recount Text (And Improve your Writing Skills)

15 Awesome Recount & Personal Narrative Topics

15 meaningful recount prompts for students

Personal Narrative Writing Guide

Learn the essential skills to writing an insightful personal narrative in our complete guide for students and teachers.

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

St Augustine (354—430) Doctor of the Church

Benjamin Franklin (1706—1790) natural philosopher, writer, and revolutionary politician in America

Anne Bradstreet (c. 1612—1672) poet

See all related overviews in Oxford Reference »

More Like This

Show all results sharing this subject:

autobiography

Quick reference.

In its modern form, may be taken as writing that purposefully and self‐consciously provides an account of the author's life and incorporates feeling and introspection as well as empirical detail. In this sense, autobiographies are infrequent in English much before 1800. Although there are examples of autobiography in a quasi‐modern sense earlier than this (e.g. Bunyan's conversion narrative, Grace Abounding, 1666, and Margaret Cavendish', duchess of Newcastle's ‘A True Relation’, 1655–6) it is not until the early 19th cent. that the genre becomes established in English writing: Gibbon's Memoirs (1796) are a notable exception.

From 1800 onwards the introspective Protestantism of an earlier period and the Romantic Movement's displeasure with the fact/feeling distinction of the Enlightenment provided for personal narratives of a largely new kind. They were characterized by a self‐scrutiny and vivid sentiment that produced what is now referred to, following Robert Southey (1809), as autobiography . Early in the 19th cent. Wordsworth gives in The Prelude (1805) a sustained reflection upon the circumstances of he himself being the subject of his own work; and in the second half of the century Newman in his Apologia pro Vita Sua (1864) publicly and originally reveals a personal spiritual journey. This latter, with its public disclosure of the private domain, had a dramatic and far‐reaching influence upon the intelligentsia of late Victorian society.

In the 20th cent. autobiography became increasingly valued not so much as an empirical record of historical events but as providing an epitome of personal sensibility among the intricate vicissitudes of cultural change. Vera Brittain achieved a seriousness of observation and affect to provide in Testament of Youth (1933) a major work on the conduct of the First World War. In the area of more domestic but no less social concerns J. R. Ackerley in his My Father and Myself (1968) constructed an autobiography of painful frankness in a disquisition upon his unusual family relations, his affection for his dog, and the tribulations of his homosexuality. More recently Tim Lott in The Scent of Dead Roses (1996) discussed the suicide of his mother and amalgamated autobiography, family history, and social analysis in a virtuoso performance of control and pathos. The truthfulness or not of autobiography is essentially a matter that must be left to biographers and philosophers. The plausibility of an autobiography, however, must find its authentication by the degree to which it can correspond to some approximation of its context.

From: autobiography in The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature »

Subjects: Literature

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries, autobiography.

View all reference entries »

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'autobiography' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 27 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

Character limit 500 /500

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, autobiography.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Who are you? How have your experiences shaped your sense of what is important or possible? Realize the benefits of using writing to reflect on your life. Read exemplary autobiographies and write about a significant, unusual, or dramatic event in your life.

Autobiographies are stories that people write about themselves. These stories can be factual accounts of significant, unusual, or dramatic events. They can be remembrances of famous or interesting people. And sometimes, when people slip from fact into fiction, they can be fictional stories, what some writers call “faction.”

Why Write an Autobiography?

As we age, we invariably wonder who and what experiences shaped us. One of our most elemental impulses is to define and explore the self. We try to understand who we are and who we can be by examining how we respond to different situations and people. Sometimes we wonder what other people think of us and wonder why we behave the way we do. Sometimes we are perplexed and feel inner discord because our self-images don’t fit with what other people or society seem to expect of us. When we feel the urge to make changes in our lives, we often find that reflecting on our experiences is a prerequisite for change. As Abraham H. Maslow remarks in his thought-provoking book on human development, Personality and Motivation, “One cannot choose wisely for a life unless he dares to listen to himself, his own self, at each moment of life.”

Not all autobiography is about expressive writing. As illustrated by the sample readings, people also tell stories about themselves to sell products or motivate people, to entertain, and to persuade people:

My role in society, or any artist or poet’s role, is to try and express what we all feel. Not to tell people how to feel. Not as a preacher, not as a leader, but as a reflection of us all -John Lennon

In a very real sense, the writer writes in order to teach himself, to understand himself -Alfred Kazin

People write autobiographies for many reasons, and they employ a variety of media while addressing diverse audiences. For some, such as John Lennon, autobiography is a social process, a way of reflecting on our culture, while for others, such as Alfred Kazin, autobiographies are a deeply personal genre, a tool for internal reflection and personal growth.

Diverse Rhetorical Situations