Passion doesn’t always come easily. Discover your inner drive and find your true purpose in life.

From learning how to be your best self to navigating life’s everyday challenges.

Discover peace within today’s chaos. Take a moment to notice what’s happening now.

Gain inspiration from the lives of celebrities. Explore their stories for motivation and insight into achieving your dreams.

Where ordinary people become extraordinary, inspiring us all to make a difference.

Take a break with the most inspirational movies, TV shows, and books we have come across.

From being a better partner to interacting with a coworker, learn how to deepen your connections.

Take a look at the latest diet and exercise trends coming out. So while you're working hard, you're also working smart.

Sleep may be the most powerful tool in our well-being arsenal. So why is it so difficult?

Challenges can stem from distractions, lack of focus, or unclear goals. These strategies can help overcome daily obstacles.

Unlocking your creativity can help every aspect of your life, from innovation to problem-solving to personal growth.

How do you view wealth? Learn new insights, tools and strategies for a better relationship with your money.

Rick Rigsby's Iconic Speech: Lessons from A Third Grade Dropout

Rick rigsby's speech - lessons from a third grade dropout.

In this passionate and life-changing speech, Dr. Rick Rigsby -- the former award-winning journalist and college professor at Texas A&M University turned motivational speaker --shares the three words that taught him how to enhance his life and make excellence a habit.

Rick Rigsby's passionate speech on the "Lessons of a third-grade dropout" that his father had bestowed upon him was watched over 200 million times on our Facebook page alone, quickly becoming one of the most passionate inspirational speeches ever heard, mobilizing millions of people to follow his advice: to Make an Impact!

Watch the full speech to learn how you too can make an impact and to soak in the lessons of the wisest third grade dropout -- Dr. Rick Rigsby's father, whose outstanding life lessons can also be found in Rigsby's now best-selling book, " Lessons From a Third Grade Dropout: How the Timeless Wisdom of One Man Can Impact an Entire Generation".

Transcript - Lessons from a Third Grade Dropout speech by Dr. Rick Rigsby:

The wisest person I ever met in my life, a third-grade dropout. Wisest and dropout in the same sentence is rather oxymoronic, like jumbo shrimp. Like Fun Run, ain't nothing fun about it, like Microsoft Works. You all don't hear me. I used to say like country music, but I've lived in Texas so long, I love country music now. I hunt. I fish. I have cowboy boots and cowboy ... You all, I'm a blackneck redneck. Do you hear what I'm saying to you? No longer oxymoronic for me to say country music, and it's not oxymoronic for me to say third grade and dropout.

That third grade dropout, the wisest person I ever met in my life, who taught me to combine knowledge and wisdom to make an impact, was my father, a simple cook, wisest man I ever met in my life, just a simple cook, left school in the third grade to help out on the family farm, but just because he left school doesn't mean his education stopped. Mark Twain once said, "I've never allowed my schooling to get in the way of my education." My father taught himself how to read, taught himself how to write, decided in the midst of Jim Crowism, as America was breathing the last gasp of the Civil War, my father decided he was going to stand and be a man, not a black man, not a brown man, not a white man, but a man. He literally challenged himself to be the best that he could all the days of his life.

I have four degrees. My brother is a judge. We're not the smartest ones in our family. It's a third grade dropout daddy, a third grade dropout daddy who was quoting Michelangelo, saying to us boys, "I won't have a problem if you aim high and miss, but I'm gonna have a real issue if you aim low and hit." A country mother quoting Henry Ford, saying, "If you think you can or if you think you can't, you're right." I learned that from a third grade drop. Simple lessons, lessons like these. "Son, you'd rather be an hour early than a minute late." We never knew what time it was at my house because the clocks were always ahead. My mother said, for nearly 30 years, my father left the house at 3:45 in the morning, one day, she asked him, "Why, Daddy?" He said, "Maybe one of my boys will catch me in the act of excellence."

I want to share a few things with you. Aristotle said, "You are what you repeatedly do." Therefore, excellence ought to be a habit, not an act. Don't ever forget that. I know you're tough. I know you're seaworthy, but always remember to be kind, always. Don't ever forget that. Never embarrass Mama. Mm-hmm (affirmative). If Mama ain't happy, ain't nobody happy. If Daddy ain't happy, don't nobody care, but I'm going to tell you.

Next lesson, lesson from a cook over there in the galley. "Son, make sure your servant's towel is bigger than your ego." I want to remind you cadets of something as you graduate. Ego is the anesthesia that deadens the pain of stupidity. You all might have a relative in mind you want to send that to. Let me say it again. Ego is the anesthesia that deadens the pain of stupidity. Pride is the burden of a foolish person.

John Wooden coached basketball at UCLA for a living, but his calling was to impact people, and with all those national championships, guess what he was found doing in the middle of the week? Going into the cupboard, grabbing a broom and sweeping his own gym floor. You want to make an impact? Find your broom. Every day of your life, you find your broom. You grow your influence that way. That way, you're attracting people so that you can impact them.

Final lesson. "Son, if you're going to do a job, do it right." I've always been told how average I can be, always been criticized about being average, but I want to tell you something. I stand here before you before all of these people, not listening to those words, but telling myself every single day to shoot for the stars, to be the best that I can be. Good enough isn't good enough if it can be better, and better isn't good enough if it can be best.

Let me close with a very personal story that I think will bring all this into focus. Wisdom will come to you in the unlikeliest of sources, a lot of times through failure. When you hit rock bottom, remember this. While you're struggling, rock bottom can also be a great foundation on which to build and on which to grow. I'm not worried that you'll be successful. I'm worried that you won't fail from time to time. The person that gets up off the canvas and keeps growing, that's the person that will continue to grow their influence.

Back in the '70s, to help me make this point, let me introduce you to someone. I met the finest woman I'd ever met in my life. Mm-hmm (affirmative). Back in my day, we'd have called her a brick house. This woman was the finest woman I'd ever seen in my life. There was just one little problem. Back then, ladies didn't like big old linemen. The Blind Side hadn't come out yet. They liked quarterbacks and running back. We're at this dance, and I find out her name is Trina Williams from Lompoc, California. We're all dancing and we're just excited. I decide in the middle of dancing with her that I would ask her for her phone number. Trina was the first ... Trina was the only woman in college who gave me her real telephone number.

The next day, we walked to Baskin and Robbins Ice Cream Parlor. My friends couldn't believe it. This has been 40 years ago, and my friends still can't believe it. We go on a second date and a third date and a fourth date. Mm-hmm (affirmative). We drive from Chico to Vallejo so that she can meet my parents. My father meets her. My daddy. My hero. He meets her, pulls me to the side and says, "Is she psycho?" Anyway, we go together for a year, two years, three years, four years. By now, Trina's a senior in college. I'm still a freshman, but I'm working some things out. I'm so glad I graduated in four terms, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan.

Now, it's time to propose, so I talk to her girlfriends, and it's California. It's in the '70s, so it has to be outside, have to have a candle and you have to some chocolate. Listen, I'm from the hood. I had a bottle of Boone's Farm wine. That's what I had. She said, "Yes." That was the key. I married the most beautiful woman I'd ever seen in my ... You all ever been to a wedding and even before the wedding starts, you hear this? "How in the world?" It was coming from my side of the family. We get married. We have a few children. Our lives are great.

One day, Trina finds a lump in her left breast. Breast cancer. Six years after that diagnosis, me and my two little boys walked up to Mommy's casket and, for two years, my heart didn't beat. If it wasn't for my faith in God, I wouldn't be standing here today. If it wasn't for those two little boys, there would have been no reason for which to go on. I was completely lost. That was rock bottom. You know what sustained me? The wisdom of a third grade dropout, the wisdom of a simple cook.

We're at the casket. I'd never seen my dad cry, but this time I saw my dad cry. That was his daughter. Trina was his daughter, not his daughter-in-law, and I'm right behind my father about to see her for the last time on this Earth, and my father shared three words with me that changed my life right there at the casket. It would be the last lesson he would ever teach me. He said, "Son, just stand. You keep standing. You keep stand ... No matter how rough the sea, you keep standing, and I'm not talking about just water. You keep standing. No matter what. You don't give up." I learned that lesson from a third grade dropout, and as clearly as I'm talking to you today, these were some of her last words to me. She looked me in the eye and she said, "It doesn't matter to me any longer how long I live. What matters to me most is how I live."

I ask you all one question, a question that I was asked all my life by a third grade dropout. How you living? How you living? Every day, ask yourself that question. How you living? Here's what a cook would suggest you to live, this way, that you would not judge, that you would show up early, that you'd be kind, that you make sure that that servant's towel is huge and used, that if you're going to do something, you do it the right way. That cook would tell you this, that it's never wrong to do the right thing, that how you do anything is how you do everything, and in that way, you will grow your influence to make an impact. In that way, you will honor all those who have gone before you who have invested in you. Look in those unlikeliest places for wisdom. Enhance your life every day by seeking that wisdom and asking yourself every night, "How am I living?" May God richly bless you all. Thank you for having me here.

Hot Stories

4th-grader makes a promise to his teacher; 12 years later, the nfl star delivers, mom dining with 2 kids notices stranger sitting nearby - then, he leaves her a note, family rejects $100m offer for their ranch — they saved their community instead, mom is worried what son with autism will do after graduation - comes up with a great idea, landlord leaves student homeless - now, he graduated at the top of his class, 11-year-old steps up to pay off his school's entire lunch debt, teen with down syndrome is invited to her first party ever - this leaves her in tears.

Teen With Down Syndrome Is Thrilled to Be Invited to Party

When you're a teenager, parties can be the event of the year — that is, if you're on the guest list. Chances are, unless you were Regina George, at some point or another we've all been excluded from a party we were dying to go to.

There's no worse feeling than hearing about all your friends having the best night ever when you were stuck at home watching a re-run of Friends (the irony isn't lost on us).

So when one teenager with Down syndrome was invited to her first party ever, she was over the moon..but she had no idea what was in store for her.

A Dream Come True

Macy's life has often been marked by exclusion. According to her mom, Heather Avis, Macy has only been invited to a handful of birthday parties since starting school. So when Macy got into the car one day, clutching an invitation with a look of pure joy, Heather knew this was a moment to cherish.

"Yesterday, Macy showed me an invitation to a birthday party for a friend at school who is also in the life skills program," Heather shared in an Instagram post. "Her joy from this invitation is palpable. WOW! To me, it spoke of a longing fulfilled. All I could do was laugh with her and then cry as I celebrated with her."

A Moment of Pure Joy — "We All Want To Be Wanted"

See on Instagram

In a heartwarming video, Macy's excitement is evident as she waves the invitation, her happiness contagious.

"You got invited to a birthday party?" Heather asks, her voice choked with emotion.

"Yeah!" Macy replies, grinning from ear to ear before letting out a joyful squeal.

Heather's voice breaks as she explains to TODAY.com , "My sweet girl is so elated to be included. It speaks to the common humanity that we all share. We all as humans want to feel like we belong. We all want to be wanted."

A Celebration of Belonging

On May 30, Heather shared an update that highlighted the significance of the birthday party. Macy is seen laughing and clapping, her body language speaking volumes.

"What did you tell me when we were there?" Heather asks.

"I love it here!" Macy responds, her joy undeniable.

Later, Macy adds, "I love birthday parties!"

Heather highlights an important detail: the birthday boy is a disabled student in the life skills class at Macy’s school. "The party was inclusive not because a student in the general education program invited Macy, but because a person with an intellectual disability invited both disabled and non-disabled individuals," Heather wrote. "It was inclusive because people like Macy and the young man we were celebrating, who are often excluded, truly understand how to include others. Let’s reflect on that for a moment!"

A Lesson In Inclusion

Macy's story is a powerful reminder of the importance of inclusion and the simple yet profound joy of being invited and included. It highlights the universal desire to belong and the impact that a single act of kindness can have. As Macy continues to find her place and share her happiness, she serves as an inspiration to create a world where everyone feels wanted and valued.

“We all have the opportunity to be the person to say, ‘I’m going to create a space where everyone can belong,'" she says.

"When I arrived at the party, I didn’t know anyone there. As Macy and I approached the birthday boy’s mom to introduce ourselves and thank her for the invitation, she greeted us with huge hugs and said, 'I’m so happy you’re here!' I confessed that I felt a bit nervous because I didn’t know anyone, and she reassured me, saying, 'Oh, these are our people. This is a safe space for all of us.' And she was absolutely right."

Former Inmate Bumps Into Son She Had Placed For Adoption at Local Walmart

They went to the same university but were strangers - now, they're the world's oldest newlyweds, bride gets a shock at the hair salon on wedding day - leaving her in tears, woman poses a question to dads online - video "backfired" for all the wrong reasons, how tiffany haddish finally found the love she deserved, the disturbing and beautiful story behind danny trejo's salma hayek tattoo, the kardashian redemption - an uncensored documentary, how did betrayal connect jennifer aniston and selena gomez, subscribe to our newsletter, usher opens up on diddy's flavor camp, the great takedown of nickelodeon’s dan schneider - how even small voices have the power for impact, chris gardner beyond the pursuit of happyness: the work begins, 100 powerful motivational quotes to help you rise above, woman can’t afford rent - so she moves in with her 94-year-old nonna.

Woman Moves in With Grandmother With Amazing Results

With the high cost of living, one woman just couldn’t afford to pay for a place of her own. So she moved in with her 94-year-old grandmother, and the heartwarming results prove that sometimes, multigenerational living is the best thing for everyone involved.

Moving in With Nonna

@rachelalbi ❤️❤️❤️ #nonna #italian #italy #italianfood #italiannonna #grandma #grandparentsoftiktok #fyp #queen #nana #italiano #italians #toronto

These days the financial struggles are real, with groceries, housing, and basically everything costing a lot of money . That can make it hard for a young person to live on their own, especially with only one salary to support them.

A woman named Rachel Albi found herself in that situation, so she moved in with her 94-year-old nonna. Some might think that that kind of living arrangement would be a strain on the grandmother and granddaughter alike. However, in a sweet video posted to TikTok, Rachel proved otherwise.

“POV: you can’t afford rent, so you move in with your 94-year-old Italian nonna, and it’s the best decision you’ve ever made,” she wrote in a video montage.

A Mutually Beneficial Decision

In the video, Rachel shared clips of her nonna making fresh pasta and sauce, bringing her tea in bed, and waving farewell from the front door as she drove off. One look at the sweet grandmother’s face and it’s pretty clear that she adores her granddaughter.

In other clips, Rachel celebrates her grandmother’s birthday, chats with her, and helps her make food. Before the 59-second clip is over, it’s hard not to smile at how happy they both seem to be with their new living arrangement. So naturally, the sweet relationship drew plenty of comments.

“You gave Nonna purpose again! No more loneliness ,” wrote one person. “This is how families should be,” wrote someone else. “The younger gaining knowledge and wisdom at the feet of their elders, and the elders feeling and being useful.”

“You can tell Nonna needed this just as much as you did,” added someone else. “You’re still her baby, and she just wants to take care of you.”

The Real Look of Success

Many of us grow up believing that in order to be successful, we need to afford our own place and go out on our own. But there are many parts of the world where grown adults continue to live with their parents, creating communities in the household that are mutually beneficial and full of love.

As parents age, they may need their kids or grandkids in the house to help take care of them. They, in turn, may continue to have drive and purpose by helping to look after the house and others who live in it.

At the end of the day, it’s relationships — not material things — that matter. Everyone’s situation is different, and people need different things. But by redefining our expectations of what success and living situations should look like, we can all embrace the sheer beauty of situations like Rachel and her nonna’s.

Copyright © 2024 Goalcast

Get stories worth sharing delivered to your inbox

High School Dropouts and Their Reasons Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Educational reasons.

Education is an essential phenomenon in the modern world because it provides people with decent opportunities for further personal and professional development. It is believed that graduates of high schools tend to achieve more successful results in their lives compared to their less-educated colleagues. Even though it is difficult to overestimate the significance of high school diplomas, a few students fail to obtain them. Thus, there are many reasons, including educational, psychological, personal, and financial ones, that make students drop out of high schools before their graduation.

It is not a surprise that academic performance is one of the principal aspects that result in a dropout. The fact is that high schools can imply various standards that their students must meet. For some of them, these requirements are almost unachievable, which makes learners fail some courses. When the number of failed courses is high, the student’s future in a particular educational establishment is determined. The outcome above is a result of a few things. On the one hand, it refers to students’ mental abilities. One should note that everyone has their own knowledge and skills, and the same assignment can be either an ordinary task or an impossible problem for different people. On the other hand, poor secondary school preparation is said to be another essential phenomenon for the given topic. It is said that some students enter high schools without having gained the necessary levels of expertise in such general courses as language and mathematics. The information above means that there are a few educational aspects that prevent learners from graduating from high schools.

Financial Reasons

Financial issues are another phenomenon that is behind numerous high school dropouts. These problems are of two different groups, and each of them is significant. Firstly, it refers to tuition fees that can be high in some cases. Thus, if a young man or woman cannot afford their tuition fees, they will be expelled. What is more tragic, the same outcome will arise if a student shows decent or even excellent academic results. One supposes that many gifted learners did not graduate from their educational institutions because of that reason. Secondly, it is a typical case when a student leaves their education because they need to make money to support their families. In this case, the financial issue meets an educational one because many working students tend to show worse academic performance. At this point, these economic reasons represent a severe obstruction to obtaining a high school diploma.

Psychological Reasons

Many students are too young, and this fact creates appropriate mental challenges for them. High schools are a regular stage in the learners’ lives representing many new things and aspects. Thus, if a student is not satisfied with this new environment, they lose interest in education. Besides, some students are undecided about their future, which makes them attend high schools because they have to, rather than because they like it. That is why some of them choose the wrong course that can force them to leave education. All the examples above are summarized as a lack of motivation. In this case, a person does not understand why they should attend classes and what advantages this education can present. As a result, these psychological reasons both prevent students from showing decent academic performance and make them find some phenomena that will be more interesting than education. Both cases lead to situations when these students will be expelled from high schools.

Personal Reasons

The group of personal reasons represents one of the most common issues that make students leave their high schools. One should remember that every learner is a personality with characteristic features, feelings, and emotions. If some of them manage to control their thoughts and actions, others fail with this task. As a result, numerous conflicts occur between students, a student, and a mentor, as well as a student and their parents on an educational basis. When such situations happen regularly, it will make learners drop out of school. Thus, students, their families, and school officials should do their best to decrease this negative impact.

In addition to that, high schools make learners believe that they are adults and may do what they want. Often, it leads them to various problems and dangerous situations. For example, young women can get pregnant; this condition will make it difficult for them to continue their education. Furthermore, both male and female students are vulnerable to many temptations. It refers to the fact that they start smoking and drinking alcohol. It is the first step towards severer problems represented by drug consumption and joining gangs. In this case, it will be difficult for these young people to avoid legal issues. Once they arise, the fact of when a dropout will occur is only a question of time.

Education presents many benefits, but not all students manage to obtain them. It is believed that a significant part of all students drop out of high school before they graduate from them. There are four groups of the reasons, including educational, financial, psychological, and personal ones. It is impossible to state which group is more crucial or which one has made more students leave their education. When they exist, it is not reasonable to ignore the given state of affairs. As a result, it is necessary to eliminate the effect of these phenomena to make more people finish their education.

- Quality Early Childhood Education in Preventing High School Dropouts

- Students at Risk of Dropout: Retention Technique

- What Do You Mean by College Tuition Cost?

- Schools and Parents' Fight Against Cyberbullying

- Partnerships Concepts: Interview Transcription

- School Uniforms: Conflicting Viewpoints

- School Uniforms: Conflicting Opinions

- Scarcity and Student’s Bandwidth

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, June 5). High School Dropouts and Their Reasons. https://ivypanda.com/essays/high-school-dropouts-and-their-reasons/

"High School Dropouts and Their Reasons." IvyPanda , 5 June 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/high-school-dropouts-and-their-reasons/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'High School Dropouts and Their Reasons'. 5 June.

IvyPanda . 2021. "High School Dropouts and Their Reasons." June 5, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/high-school-dropouts-and-their-reasons/.

1. IvyPanda . "High School Dropouts and Their Reasons." June 5, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/high-school-dropouts-and-their-reasons/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "High School Dropouts and Their Reasons." June 5, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/high-school-dropouts-and-their-reasons/.

- About PDK International

- About Kappan

- Issue Archive

- Permissions

- About The Grade

- Writers Guidelines

- Upcoming Themes

- Artist Guidelines

- Subscribe to Kappan

Select Page

Student disengagement: It’s deeper than you think

By Charles Mojkowski, Elliot Washor | May 1, 2014 | Feature Article

American schools are failing to meet the expectations of a wide swath of students, many of them in low-income and rural communities. What’s needed is a new pact putting student expectations at its center.

Even the president is talking about student engagement — or disengagement — in school.

In his 2013 State of the Union Address, President Obama gave special attention to education and particularly to the problem of high school dropouts. This isn’t the first time the President has used a major speech to highlight this problem. In a February 2009 speech to a joint session of Congress, the President said dropping out “is no longer an option.” Sadly, dropping out does remain an option for many young people — 1.3 million students leave high school each year without a diploma.

Like the President, we’ve been paying attention for many years and have come to see the dropout problem as part of a larger and more pervasive one: student disengagement from their schools, communities, and productive learning. This disengagement is particularly strong and pervasive in poor urban and rural communities, where forces of disengagement are more formidable, and the resources for battling them more limited.

In our work with students in these communities, we’ve identified several reasons. Young people feel that who they are and what they want to become doesn’t matter to teachers and schools. While students are required to fit into a restrictive school structure, culture, and curriculum, schools do little to fit themselves to their students.

Many students drop out because of academic failure, behavioral problems, and life issues; many more stay in school but drop out in their heads — gradually disengaging from what schools have to offer. These disengaged students pass the tests and get passing grades, but they limp to a tainted graduation and a diploma that papers over their lack of readiness for successful postsecondary learning and work. Often these disengaged students are just off the radar screens of those early warning systems devised to detect potential dropouts.

Researchers have calculated the cost of dropouts to society, but they’ve missed the significantly larger cost of disengaged students. They are the ones who graduate from high school but are unprepared for lifelong learning. Their talents and potential have been sadly ignored, often because those talents reside just outside the traditional subject-matter bins of a cognitive-abstract curriculum.

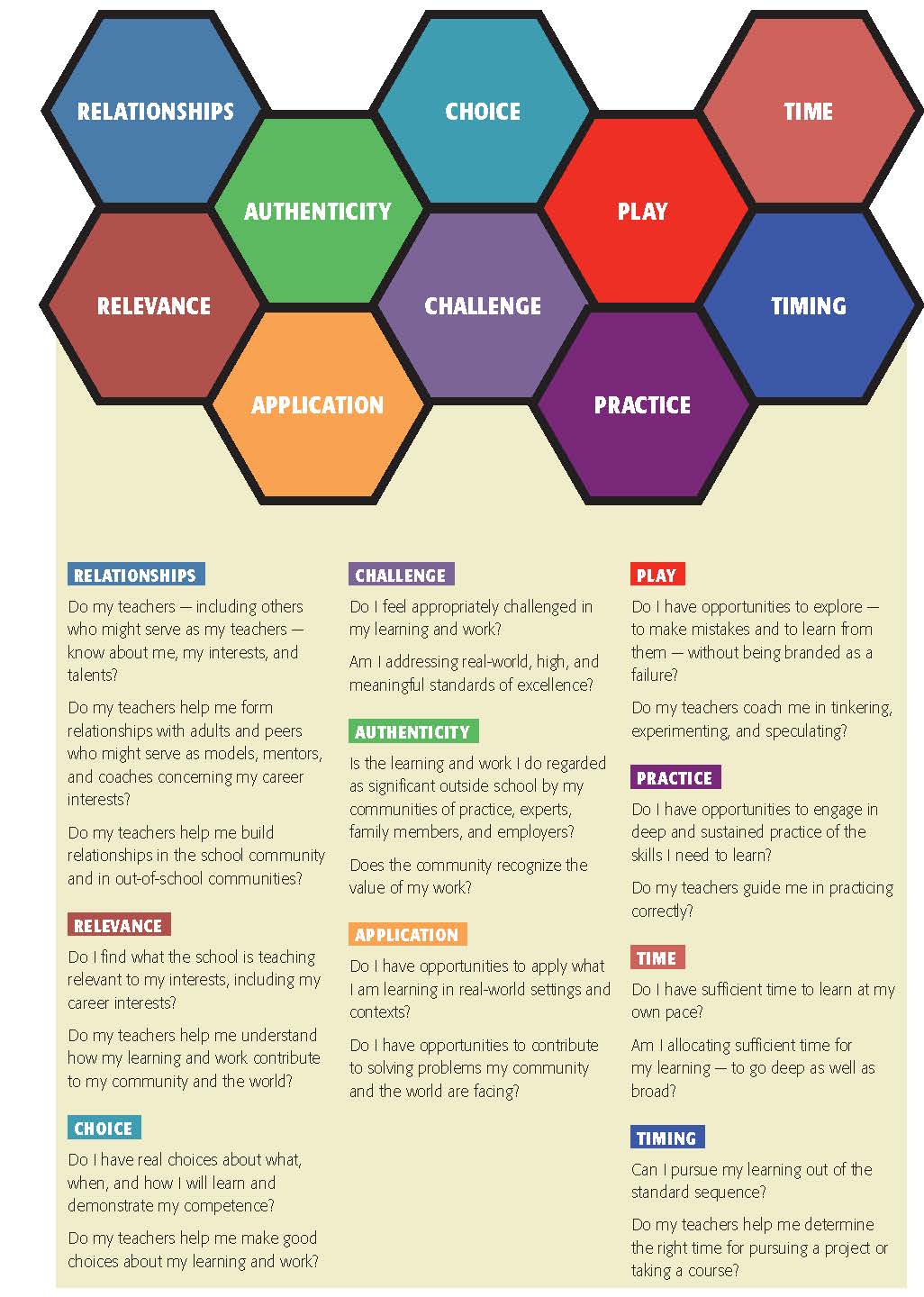

Just as schools have high expectations for students, young people have high expectations for schools. Through our work with young people, we’ve identified 10 such expectations. We believe student expectations constitute the rules for engagement in a new relationship that young people want with school. We frame these expectations in the form of questions that students might — and often do — ask their teachers.

Relationships

Do my teachers — including others who might serve as my teachers — know about me, my interests, and talents?

Do my teachers help me form relationships with adults and peers who might serve as models, mentors, and coaches concerning my career interests?

Do my teachers help me build relationships in the school community and in out-of-school communities?

Relevance

Do I find what the school is teaching relevant to my interests, including my career interests?

Do my teachers help me understand how my learning and work contribute to my community and the world?

Do I have real choices about what, when, and how I will learn and demonstrate my competence?

Do my teachers help me make good choices about my learning and work?

Challenge

Do I feel appropriately challenged in my learning and work?

Am I addressing real-world, high, and meaningful standards of excellence?

Authenticity

Is the learning and work I do regarded as significant outside school by my communities of practice, experts, family members, and employers?

Does the community recognize the value of my work?

Application

Do I have opportunities to apply what I am learning in real-world settings and contexts?

Do I have opportunities to contribute to solving problems my community and the world are facing?

Do I have opportunities to explore — to make mistakes and to learn from them — without being branded as a failure?

Do my teachers coach me in tinkering, experimenting, and speculating?

Do I have opportunities to engage in deep and sustained practice of the skills I need to learn?

Do my teachers guide me in practicing correctly?

Do I have sufficient time to learn at my own pace?

Am I allocating sufficient time for my learning — to go deep as well as broad?

Can I pursue my learning out of the standard sequence?

Do my teachers help me determine the right time for pursuing a project or taking a course?

This list is by no means definitive or even comprehensive, but these student expectations capture what we consider essentials for a student learning experience leading to sustained engagement in deep and productive learning.

The key to addressing the dropout problem is in not addressing the dropout problem alone. We recall the reminder that became a meme — “it’s the economy, stupid,” — popularized by James Carville, President Clinton’s former campaign adviser. Carville’s invocation was a reminder to himself to stay focused on the right issue. And we’ve been reminding ourselves that “it’s disengagement, stupid” that should attract our attention.

The key to addressing the dropout problem is in not addressing the dropout problem alone.

The education system focuses on dropping out, which it attempts to solve by creating early warning systems that tag potential dropouts for special attention. But we should not fool ourselves. This is an old magician’s trick. We’re watching the dropout issue, but we’re being distracted from the deeper and more pervasive problem of student disengagement.

Could the misdirection of our attention be motivated by an unconscious unwillingness to undertake the much more fundamental changes that would be necessary to deliver the student expectations and thereby engage all students in deeper and productive learning? After all, addressing the dropout problem does not require schools to redesign themselves or change how they operate. School life can go on as usual even as schools create a special set of remediations for potential or actual dropouts.

By redesigning themselves to deliver on student expectations, schools can move from remediation to prevention, similar to the approach suggested for American health care, which is so skewed to treatment that an estimated 30% of all diseases are iatrogenic — caused by the doctor or the hospital implementing a treatment.

In a similar vein, many high school dropouts are produced by the system itself. How might educators redesign schools to increase deep and sustained student engagement? We propose a prevention system with student expectations as its design imperative. In such a redesigned school teachers would act as fiduciaries for students, giving serious attention to their choices regarding their education, considering what’s best for each student, and helping each discover what’s best for him or her.

In Leaving to Learn (Heinemann, 2013), we argue that traditional school structures, cultures, programs, curricula, and instructional practices can’t adequately respond to student expectations unless schools develop opportunities for all students to do some learning outside school. To accomplish this, schools must take down the walls that separate learning that students do inside the school from outside of it.

Student expectations describe what students want with respect to learning opportunities and learning environments. Note, however, that teachers can use the expectations as student competencies. For example, with respect to relationships, students ask their teachers to know who they are and to use that knowledge to shape their learning opportunities. By turning the lens 180 degrees, however, it is possible to see the expectation regarding relationships being used by the teacher to push the student to develop deep and meaningful relationships with adults and peers outside the school who are doing learning and work the student wishes to do. Each of the expectations can serve this dual purpose.

Our intention is to develop a suite of tools that teachers, students, and parents can use to assess how well schools and students are doing with respect to each of these expectations. Schools that deliver on these expectations will see high and sustained levels of student engagement in deep and productive learning.

The relationship between schools and their students is deteriorating in our nation’s high schools. Hundreds of charter and alternative schools around the country are attempting to change that relationship, but they only patch a system that requires fundamental redesign, a safety valve that unintentionally reduces the pressure for more fundamental and systemwide reform. By using student expectations as design imperatives, educators can fundamentally reshape their schools.

We look forward to the day when every school posts these student expectations on their web page to signal their new student-centered focus. Indeed, it’s our expectation!

Citation: Washor, E. & Mojkowski, C. (2014). Student disengagement: It’s deeper than you think. Phi Delta Kappan , 95 (8), 8-10.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Charles Mojkowski

CHARLES MOJKOWSKI is a consultant and designer specializing in developing nontraditional, technology-enabled schools, programs, curricula, and instructional practices. He and Elliot Washor are coauthors of Leaving to Learn: How Out-of-School Learning Increases Student Engagement and Reduces Dropout Rates . Portions of this article were published earlier as a blog at the Huffington Post.

Elliot Washor

ELLIOT WASHOR is cofounder of Big Picture Learning in Providence, R.I.

Related Posts

Preventing online radicalization and extremism in boys

March 27, 2023

We need to know more about CTE teachers

February 27, 2023

Security and communication improve community trust

February 1, 2015

The fear of multiple truths: On teaching about racism in a predominantly white school

January 25, 2021

Recent Posts

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Delinquent. Dropout. At-Risk. When Words Become Labels

Anya Kamenetz

Sidney Poitier (right) and Glenn Ford (standing) in the 1955 film Blackboard Jungle. The Kobal Collection hide caption

Sidney Poitier (right) and Glenn Ford (standing) in the 1955 film Blackboard Jungle.

Much of our recent reporting , especially from New Orleans, has focused on young people who are neither in school nor working. There are an estimated 5 1/2 million of them, ages 16 to 24, in the United States.

But what do we call them? The nomenclature has fluctuated widely over the decades. And each generation's preferred term is packed with assumptions— economic, social, cultural, and educational — about the best way to frame the issue. Essentially, each name contains an argument about who's at fault, and where to find solutions.

"I think the name matters," says Andrew Mason, the executive director of Open Meadow , an alternative school in Portland, Ore. "If we're using disparaging names, people are going to have a hard time thinking that you're there to help kids."

Mason has worked in alternative education for more than 23 years and has seen these terms evolve over time.

The New Vocabulary Of Urban Education

To delve deeper into just how much the taxonomy has changed, I used Google's Ngram Viewer tool to track mentions of some of the most popular phrases in published books. I started at the year 1940. Back then, the prevailing term was:

Juvenile Delinquent

This is among the oldest terms used to describe this category of young people. It was originally identified with a reformist, progressive view that sought special treatment for them, outside of adult prisons. It lumped together youths who broke a law, "wayward" girls who got pregnant or young people who were simply homeless.

The New York House of Refuge, founded in 1825, has been called the first institution designated exclusively to serve such youth. An 1860 article in The New York Times described its mission as "the reformation of juvenile delinquents."

This was the beginning of the "reform school," aka "industrial school" movement. The primary response to young people in these situations was to institutionalize them, sometimes for years, with varying levels of access to food, shelter, work and education. Meanwhile, the first designated juvenile court was established in 1899 in Cook County, Ill.

The Ngram graph shows rising interest in "juvenile delinquents" throughout the 1950s and 1960s — reflected in pop culture images like West Side Story and Rebel Without A Cause. A series of Supreme Court cases in the late '60s and early '70s established that courts could not have carte blanche in institutionalizing young defendants; their rights should be similar to those of adults.

Nell Bernstein, a journalist who has written several books about juvenile justice, points out that the term "juvenile" is more commonly used to refer to animals than people. "I have two teenage children, but I don't call them juveniles," she says. "It's dehumanizing."

The concept of a high school dropout was nonsensical through the early 20th century. That's because so few people graduated from high school in the first place. There was a concerted government effort to increase high school enrollment through the Great Depression. But graduation rates topped 50 percent of the population only by 1940 .

As we can see here, the drumbeat about a "dropout crisis" rose steeply in the 1960s and reached a peak in the early 1970s. Part of that was due to demographics. The baby boom had subsided into a "birth dearth," and enrollment was flattening for the first time in U.S. history. In the meantime, the economic benefits of an education continued to grow.

Bernstein says that in her experience, the rise in use of the term dropout was tied to psychedelic pioneer Timothy Leary's famous slogan, "Turn on, tune in, drop out."

This image of dropping out as a cultural or social choice has persisted, she says. "When I did research on homeless youth, there was a strong misconception that they were '60s-style dropouts who had left in pursuit of freedom and because they couldn't do as many drugs at home."

Bernstein favors also using the term "pushout," which, she says, "opens up the possibility that the onus isn't entirely on the dropout" and "looks at root causes." In our New Orleans reporting we often found people talking about students getting "pushed out" of school.

Concern about dropouts soared again in the 1990s. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush set a a national goal of cutting the dropout rate to 10 percent.

However, says Russell Rumberger, director of the California Dropout Research Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara, high school graduation rates kept declining, to a modern-day low of 69 percent by 2002.

It has since rebounded to an all-time high.

But, he says, "I worry about emphasis on this one statistic, because it masks variations that are quite important." He cites a Brookings Institution study that says that to raise your chances of becoming middle class by age 40, it's necessary to avoid jail, avoid becoming pregnant as a teen and pass high school with at least a 2.5 GPA.

At-Risk Youth

The term "at-risk youth" gained currency in the wake of the 1983 publication of the policy report A Nation At Risk . The report cautioned that America's way of life was threatened by a "rising tide of mediocrity" within the school system. The term "at risk" suggests a focus on prevention and intervention, in the form of social services, tutoring and related programs. According to the Ngram, it seems to have risen in popularity just as "juvenile delinquent" declined.

"Delinquent" conjures up a state of being, while "at risk" suggests a vulnerable person in need of help. A scholarly paper by Margaret Placier at the University of Missouri, Columbia argues that "at risk" became a buzzword because it was vague enough to be defined broadly or narrowly, depending on the purpose. But Bernstein and Mason both point out that "at risk" also focuses on the negative.

Superpredator

A 1995 article by John J. Dilulio Jr., a professor and author with appointments at Princeton University, the Brookings Institution and the Manhattan Institute, was titled, "The Coming of the Super-Predators." It predicted a rising tide of youth violence: a burgeoning generation of homicidal thugs without a conscience, "elementary school youngsters who pack guns instead of lunches," found "in black inner-city neighborhoods." The culprits, Dilulio wrote, were drugs, child abuse and other types of "moral poverty."

More Stories On Opportunity Youth

Falling Through The Cracks: Young Lives Adrift In New Orleans

In New Orleans, A Second-Chance School Tries Again

The concept caught on in the media and among politicians. In the 1990s, as part of a broader "tough on crime" trend, almost every state passed laws that raised the number of young people being tried as adults. But the promised boom in youth crime never arrived — in fact, by the '90s, juvenile offenses had begun to level off, and today they are at their lowest rates ever.

When Gina Womack founded Families And Friends Of Louisiana's Incarcerated Children, an advocacy group, 17 years ago, she had to contend with the image of the aggressive, incorrigible "superpredator." Gradually, she says, it faded. "Kids were thought of, and talked about, as children, and not so much as these horrible monsters."

Bernstein calls the superpredator stereotype "absurd and devastating ... an insult you can't take back." She points out that, like juvenile, it compares people to animals. As the Ngram chart shows, the word never really went away.

Opportunity Youth

Opportunity youth is a phrase of such recent vintage, it doesn't show up in a Google book search.

John Bridgeland, CEO of Civic Enterprises, a public-policy firm in Washington, D.C., coined the term in a 2012 report . It was created with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (which funds education coverage among other areas at NPR). Bridgeland had previously authored a national survey and report on dropouts, titled "The Silent Epidemic."

"I'm not one to paper over reality or hardship," he says. "I don't like buzz terms or jargon." But in talking with young people in these situations, he says, he saw "Extraordinary untapped potential. ... They saw the benefits of finishing school and getting a decent job. They were extremely hopeful, notwithstanding their challenges. My bottom line was, if they can be hopeful, why can't we?"

Bridgeland's "opportunity" had a second meaning. He commissioned economic calculations of the social costs of these young people, as measured in lost wages and increased use of social services. "They cost the economy and our society $93 billion every year," he says. "If you're not compelled by the moral, individual argument, maybe the economic argument will wake you up."

The Aspen Institute , among others, has funded "opportunity youth" initiatives that seek to bring together schools, community groups, foster care programs, family court and the juvenile justice system to help young people find their way back.

"Some folks who do this work like it. Some don't," Melissa Sawyer, whose Youth Empowerment Project serves this population in New Orleans, says of the "opportunity youth" catchphrase. It can be seen as empowering, she says, or condescending. "At one level, it's semantics."

- Insights & Impact

When Students Speak and Educators Listen: Student-Voice Tools for Dropout Prevention

Posted on 02.27.2015

Asked what she would tell adults trying to understand why students drop out of high school, Andrea * quietly responds: “Just because a student wants to drop out of school doesn’t mean she’s stupid or she’s lost hope.

“Listen to her. It might be the best thing you ever do.”

Like a disconcerting number of students across Nevada, Andrea, a teenager in Washoe County School District (WCSD), dropped out of high school. With only 71 percent of the state’s students graduating in the class of 2013, WCSD administrators have tried various strategies to reengage students like Andrea and keep them supported and on track to graduate. But they found that even when, through considerable effort, they could get students who had dropped out to return to school — attending district reengagement centers and receiving academic coaching — the same students often dropped out again.

So WCSD decided to tap into a rich source of data that had been missing from their previous efforts to reduce dropout rates: input from the students themselves.

“To support students in persisting and graduating, we knew we needed a deeper understanding of their reasons for quitting school,” says Jennifer Harris, a WCSD program evaluator. “And to do that, we needed to ask students to tell their personal stories of dropping out and returning to school, and really listen to what they had to say.”

Stress from mental health problems and bullying led Andrea to leave school, but she says that her determination to earn a high school diploma and pursue vocational training helped her decide to reenroll. She shares these insights in a powerful student-produced video in which she and seven other students who reenrolled in WCSD schools speak frankly about why they stopped attending school, the kind of support that would have helped them persevere, and why they came back. The video grew out of a partnership between WCSD and the Regional Educational Laboratory (REL) West at WestEd that focused on collaborating with WCSD students at risk of dropping out in order to better address their unique challenges.

This video has become a powerful tool for raising district- and state-level awareness of the challenges, strengths, and aspirations of individual students who dropped out of high school but later returned, giving themselves another chance to graduate — told in the students’ own words. The student-produced video has been shown to counselors and principals across WCSD, and Nevada’s state superintendent has requested that it be shown to school leaders in the state.

“I usually get calls from principals after it’s shown,” Harris says. “They ask me to show it to their whole staff.”

Finding the right tool for the job

Even though WCSD was committed to the notion of listening to student ideas about school improvement, “we had difficulty imagining what that would look like in our classrooms and schools across the district,” says Harris, who is part of a WCSD team that secured a five-year High School Graduation Initiative (HSGI) grant in 2011 from the U.S. Department of Education to build new pathways to graduation for students at risk of dropping out or for dropouts who return to school.

With momentum from their HSGI projects, in 2013 the WCSD team began to discuss additional practical strategies with BethAnn Berliner, a senior REL West researcher who works with a number of states and local education agencies in making data-based decisions to address dropout prevention and reengagement efforts. Those conversations led to the idea of developing a toolkit designed to elicit student perspectives and engagement — or student voice — to inform districtwide approaches to helping students persist and graduate.

While eliciting student perspectives to guide school improvement initiatives is not necessarily a new strategy, student experiences and ideas are usually “voiced” indirectly through responses to surveys or participation in meetings structured and led by adults, says Berliner. “It’s much less common for students to have authentic opportunities to partner with adults to wrestle with school problems,” she says, “and even rarer for students to plan and lead such efforts.”

Although the toolkit initially focused on dropout prevention, the final version developed and produced by WCSD and REL West, Speak Out, Listen Up! Tools for Using Student Perspectives and Local Data for School Improvement , is designed for use by all grade levels to address local school-improvement-related topics or problems. Berliner notes that students are seen as a key to finding solutions, rather than as a source of school problems. Research on the effectiveness of using student voice to address school change is just emerging, says Berliner, but the literature suggests that listening closely to what students say about their school experiences can help educators better understand and address local challenges and rethink policies and practices.

School climate research corroborates the connection between the use of student input to inform school improvement decisions and positive school outcomes. For example, a 2011 federally funded project to improve the climate of 58 California schools drew heavily on two strategies to incorporate student perspectives: using Student Listening Circles (like the Inside-Outside Fishbowl tool described later in this article) and having students analyze and discuss data from the California Healthy Kids Survey. A WestEd report on the project revealed that after two years, 86 percent of participating schools — which were selected based on their poor climate scores —improved their school climate. Furthermore, a large majority significantly improved their academic performance, as measured by students’ results on statewide standardized tests.

Empowering students to take action

Published by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences, the toolkit comprises three student voice tools, each of which has three essential components: collaboration between adults and students in a school setting, local data gathering and/or analysis on a school issue or problem, and an action step to address school improvement. The tools are:

- ASK (Analyzing Surveys with Kids) : Students analyze and interpret existing local data (like survey results) associated with a school-related topic or problem, then produce explanations and suggestions for school improvement.

- Inside-Outside Fishbowl : Students and educators trade roles as speakers and listeners during a structured discussion of a school-related topic or problem, and jointly develop an action plan.

- S4 (Students Studying Students’ Stories) : Students lead a digital storytelling process in which they produce and analyze videotaped interviews of other students discussing a school-related topic or problem, then host forums with educators to suggest improvements.

The tools vary in complexity, duration, and the amount of student responsibility. For instance, the S4 tool used to produce the WCSD video took a class of students at an alternative high school an entire semester to develop, with support from their teacher and a video editor. Those students — who had themselves dropped out of school and reenrolled — developed the interview questions, interviewed and videotaped the volunteer subjects, created a story line from the raw video footage, and participated in the editing. While they were still attending high school, they also introduced the video at showings for educator groups and participated in structured, reflective discussions afterward.

“The tools can help give disengaged students more responsibility and buy-in for school improvement efforts,” Berliner says, “and can help ensure that changes made to the school environment actually reflect student perspectives and needs.”

Gaining insights and challenging common perceptions

Many student comments in the video interviews confirmed that the reasons for dropping out are varied, complex, and personal. Some examples: mental health challenges not being addressed; special learning needs not being recognized or met; parents who have addiction and other problems; being bullied or in abusive relationships; or other life circumstances that interfere with staying on track to earn a diploma.

A common theme voiced across all the interviews was the fundamental need for a caring adult in the school setting who checks in with them regularly. “One of the reasons these students persisted was because they had caring teachers, coaches, and others in their lives who believed in them,” says Berliner.

Both Harris and Berliner have noticed that the students’ stories are challenging common preconceptions about who these students are as individuals. “They are smart and articulate, they take pride in being students, and they have high aspirations,” says Berliner. “And they want to be happy.”

Five of the eight students in the WCSD video graduated and are now working or in college. Two students are currently working toward a high school diploma, and one student dropped out again.

Using student voice to address a range of local challenges

Beyond offering a practical way to support dropout prevention, the Speak Out, Listen Up! toolkit has become a catalyst in WCSD for a different way of thinking about and acting on a range of school issues and problems. “New conversations are taking place in the district,” Harris says, “on topics like student mental health, the need for stronger wraparound supports for at-risk students, and improving school climate.”

WCSD has launched an interdisciplinary districtwide task force to better incorporate student voice in school improvement efforts. And the toolkit is being introduced to school teams across grade levels through the district’s Social and Emotional Learning Initiative. “Students are better able to realize and practice their social and emotional competencies when they can communicate their views on issues that are important to them,” Says Harris.

“I only fully realized how valuable the toolkit was when we started introducing it to other educators,” Harris says. “Now, when people ask us for support in using student voice to address school-improvement issues, we have solid strategies to offer them.”

For further information about the Speak Out, Listen Up! toolkit, contact BethAnn Berliner at 415.302.4209 or [email protected].

For further information about using the toolkit, including developing and using a student-produced video, contact Jennifer Harris at 775.333.3766 or [email protected].

* Andrea is a pseudonym used to protect this student’s privacy.

- New toolkit elicits student perspectives and engagement to address local school improvement problems.

- Student-voice tools can give disengaged students more responsibility and buy-in for school improvement efforts.

- Washoe County collaborated with students at risk of dropping out in order to better address their unique challenges.

Subscribe to the E-Bulletin for regular updates on research, free resources, services, and job postings from WestEd.

Related Resources

Speak Out, Listen Up! Tools For Using Student Perspectives and Local Data for School Improvement

Listening to student voice — listening closely to what students say about their school experiences — can help educators understand topics or problems and rethink practices to ...

Ask a question, request information, make a suggestion, or sign up for our newsletter.

- WestEd Bulletin

- Equity in Focus

- Areas of Work

- Charters & School Choice

- Comprehensive Assessment Solutions

- Culturally Responsive & Equitable Systems

- Early Childhood Development, Learning, and Well-Being

- Economic Mobility, Postsecondary, and Workforce Systems

- English Learner & Migrant Education Services

- Justice & Prevention

- Learning & Technology

- Mathematics Education

- Resilient and Healthy Schools and Communities

- School and District Transformation

- Special Education Policy and Practice

- Strategic Resource Allocation and Systems Planning

- Supporting and Sustaining Teachers

- Professional Development

- Research & Evaluation

- How We Can Help

- Reports & Publications

- Technical Assistance

- Technical Assistance Services

- Policy Analysis and Other Support

- New Releases

- Top Downloads

- R&D Alert

- Best Sellers

- Board of Directors

- Equity at WestEd

- WestEd Pressroom

- WestEd Offices

- Contracting Opportunities

Work at WestEd

Student Disengagement: It’s Deeper than You Think

- Share article

American schools are failing to meet the expectations of a wide swath of students, many of them in low-income and rural communities. What’s needed is a new pact putting student expectations at its center.

Even the president is talking about student engagement — or disengagement — in school.

In his 2013 State of the Union Address, President Obama gave special attention to education and particularly to the problem of high school dropouts. This isn’t the first time the President has used a major speech to highlight this problem. In a February 2009 speech to a joint session of Congress, the President said dropping out “is no longer an option.” Sadly, dropping out does remain an option for many young people — 1.3 million students leave high school each year without a diploma.

Like the President, we’ve been paying attention for many years and have come to see the dropout problem as part of a larger and more pervasive one: student disengagement from their schools, communities, and productive learning. This disengagement is particularly strong and pervasive in poor urban and rural communities, where forces of disengagement are more formidable, and the resources for battling them more limited.

In our work with students in these communities, we’ve identified several reasons. Young people feel that who they are and what they want to become doesn’t matter to teachers and schools. While students are required to fit into a restrictive school structure, culture, and curriculum, schools do little to fit themselves to their students.

Many students drop out because of academic failure, behavioral problems, and life issues; many more stay in school but drop out in their heads — gradually disengaging from what schools have to offer. These disengaged students pass the tests and get passing grades, but they limp to a tainted graduation and a diploma that papers over their lack of readiness for successful postsecondary learning and work. Often these disengaged students are just off the radar screens of those early warning systems devised to detect potential dropouts.

Researchers have calculated the cost of dropouts to society, but they’ve missed the significantly larger cost of disengaged students. They are the ones who graduate from high school but are unprepared for life-long learning. Their talents and potential have been sadly ignored, often because those talents reside just outside the traditional subject-matter bins of a cognitive-abstract curriculum.

Just as schools have high expectations for students, young people have high expectations for schools. Through our work with young people, we’ve identified 10 such expectations . We believe student expectations constitute the rules for engagement in a new relationship that young people want with school. We frame these expectations in the form of questions that students might — and often do — ask their teachers.

This list is by no means definitive or even comprehensive, but these student expectations capture what we consider essentials for a student learning experience leading to sustained engagement in deep and productive learning.

The key to addressing the dropout problem is in not addressing the dropout problem alone . We recall the reminder that became a meme — “it’s the economy, stupid,” — popularized by James Carville, President Clinton’s former campaign adviser. Carville’s invocation was a reminder to himself to stay focused on the right issue. And we’ve been reminding ourselves that “it’s disengagement, stupid” that should attract our attention.

The education system focuses on dropping out, which it attempts to solve by creating early warning systems that tag potential dropouts for special attention. But we should not fool ourselves. This is an old magician’s trick. We’re watching the dropout issue, but we’re being distracted from the deeper and more pervasive problem of student disengagement.

Could the misdirection of our attention be motivated by an unconscious unwillingness to undertake the much more fundamental changes that would be necessary to deliver the student expectations and thereby engage all students in deeper and productive learning? After all, addressing the dropout problem does not require schools to redesign themselves or change how they operate. School life can go on as usual even as schools create a special set of remediations for potential or actual dropouts.

By redesigning themselves to deliver on student expectations, schools can move from remediation to prevention, similar to the approach suggested for American health care, which is so skewed to treatment that an estimated 30% of all diseases are iatrogenic — caused by the doctor or the hospital implementing a treatment.

In a similar vein, many high school dropouts are produced by the system itself. How might educators redesign schools to increase deep and sustained student engagement? We propose a prevention system with student expectations as its design imperative. In such a redesigned school teachers would act as fiduciaries for students, giving serious attention to their choices regarding their education, considering what’s best for each student, and helping each discover what’s best for him or her.

In Leaving to Learn (Heinemann, 2013), we argue that traditional school structures, cultures, programs, curricula, and instructional practices can’t adequately respond to student expectations unless schools develop opportunities for all students to do some learning outside school. To accomplish this, schools must take down the walls that separate learning that students do inside the school from outside of it.

Student expectations describe what students want with respect to learning opportunities and learning environments. Note, however, that teachers can use the expectations as student competencies. For example, with respect to relationships, students ask their teachers to know who they are and to use that knowledge to shape their learning opportunities. By turning the lens 180 degrees, however, it is possible to see the expectation regarding relationships being used by the teacher to push the student to develop deep and meaningful relationships with adults and peers outside the school who are doing learning and work the student wishes to do. Each of the expectations can serve this dual purpose.

Our intention is to develop a suite of tools that teachers, students, and parents can use to assess how well schools and students are doing with respect to each of these expectations. Schools that deliver on these expectations will see high and sustained levels of student engagement in deep and productive learning.

The relationship between schools and their students is deteriorating in our nation’s high schools. Hundreds of charter and alternative schools around the country are attempting to change that relationship, but they only patch a system that requires fundamental redesign, a safety valve that unintentionally reduces the pressure for more fundamental and system-wide reform. By using student expectations as design imperatives, educators can fundamentally reshape their schools.

We look forward to the day when every school posts these student expectations on their web page to signal their new student-centered focus. Indeed, it’s our expectation!

All articles published in Phi Delta Kappan are protected by copyright. For permission to use or reproduce Kappan articles, please e-mail [email protected] .

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Education

Essay Samples on Dropping Out of School

Weighing the consequences: an exploration of dropping out of high school.

The decision to drop out of high school is a significant and complex one, carrying lasting implications for individuals and society as a whole. This essay delves into the factors that may lead to the choice to drop out, the potential consequences of such a...

- Dropping Out of School

- High School

Solutions to Prevent High School Dropouts

The issue of high school dropouts is a multifaceted challenge that impacts individuals, communities, and society at large. High school education is a critical foundation for future success, and dropping out can lead to limited opportunities, reduced earning potential, and increased social disparities. This essay...

Decision Making: The Presence Of School Dropouts

Why do students dropout of high school? Every year, it becomes more common that thousands of teenagers in America would drop out of high school without diplomas, this is a strong epidemic expressed through the documentary “Dropout Nation,” which visually represents the crippling reasons behind...

Role Of High School Freshman Year In Determining Academic Performance

Initially, freshman year helps determine a student’s risk of failing and dropping out. When you go into high school, you become responsible for yourself. This means people are no longer consistently looking over your shoulder and telling you what to do. As a result, some...

- Performance

Comparative Analysis of Student Dropouts from the 1990s and 2010s

Education is a systematic process where knowledge, experience, and ability are obtained (Parankimalil, 2012). In this process, humans develop their knowledge, personality and behaviour (Farooq, 2012). Through this development people become more independent. They become more aware and have a better understanding on what is...

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

The Effects of Bullying in Schools and How to Prevent It

Impact of Bullying in Schools Research found that harassing harmfully affects student's execution. (Cynthia 2014) contended that refinement in connection between scholarly execution and tormenting level contingent upon student's scholastic accomplishment. Effect of harassing on student's capacity to perform and accomplish scholastically was examined (Block...

Reasons Behind the Increased Suicide Rate Among High School Students

Did you know that the average rate of suicide in high schools has increased from 2005 to 2015(1)? Most people are forced to attend some sort of education throughout their life and for most people it causes severe stress. High School students today are faced...

Best topics on Dropping Out of School

1. Weighing the Consequences: An Exploration of Dropping Out of High School

2. Solutions to Prevent High School Dropouts

3. Decision Making: The Presence Of School Dropouts

4. Role Of High School Freshman Year In Determining Academic Performance

5. Comparative Analysis of Student Dropouts from the 1990s and 2010s

6. The Effects of Bullying in Schools and How to Prevent It

7. Reasons Behind the Increased Suicide Rate Among High School Students

- Importance of Education

- Academic Achievements

- College Education

- Interpretation

- Physical Education

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Student Engagement and School Dropout: Theories, Evidence, and Future Directions

- First Online: 20 October 2022

Cite this chapter

- Isabelle Archambault 3 ,

- Michel Janosz 3 ,

- Elizabeth Olivier 3 &

- Véronique Dupéré 3

3746 Accesses

14 Citations

School dropout is a major preoccupation in all countries. Several factors contribute to this outcome, but research suggests that dropouts mostly have gone through a process of disengaging from school. This chapter aims to present a synthesis of this process according to the major theories in the field and review empirical research linking student disengagement and school dropout. This chapter also presents the common risk and protective factors associated with these two issues, the profiles of students who drop out as well as the disengagement trajectories they follow and leading to their decision to quit school. Finally, it highlights the main challenges as well as the future directions that research should prioritize in the study of student engagement and school dropout.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Afia, K., Dion, E., Dupéré, V., Archambault, I., & Toste, J. (2019). Parenting practices during middle adolescence and high school dropout. Journal of Adolescence, 76 , 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.08.012

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Agirdag, O., Van Houtte, M., & Van Avermaet, P. (2013). School segregation and self-fulfilling prophecies as determinants of academic achievement in Flanders. In S. De Groof & M. Elchardus (Eds.), Early school leaving and youth unemployment (pp. 46e74) . Amsterdam University Press.

Google Scholar

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., & Kabbani, N. S. (2001). The dropout process in life course perspective: Early risk factors at home and school. Teachers College Record, 103 (5), 760–822. https://doi.org/10.1111/0161-4681.00134

Article Google Scholar

Alliance for Excellent Education. (2013). Saving futures, saving dollars: The impact of education on crime reduction and earnings . Retrived from https://mk0all4edorgjxiy8xf9.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/SavingFutures.pdf .

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., & Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the student engagement instrument. Journal of School Psychology, 44 (5), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.04.002

Archambault, I., Pascal, S., Tardif-Grenier, K., Dupéré, V., Janosz, M., Parent, S., & Pagani, L. (2021). The contribution of teacher structure, involvement, and autonomy support on student engagement in low-income elementary schools. Teachers and Teaching, 26 (5–6), 428–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1863208

Archambault, I., & Dupéré, V. (2017). Joint trajectories of behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in elementary school. The Journal of Educational Research, 110 (2), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2015.1060931

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Dupéré, V., Brault, M.-C., & Andrew, M. M. (2017). Individual, social, and family factors associated with high school dropout among low- SES youth: Differential effects as a function of immigrant status. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87 (3), 456–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12159

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Fallu, J.-S., & Pagani, L. S. (2009a). Student engagement and its relationship with early high school dropout. Journal of Adolescence, 32 (3), 651–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.007

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. (2009b). Adolescent behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in school: Relationship to dropout. Journal of School Health, 79 (9), 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00428.x

Basharpoor, S., Issazadegan, A., Zahed, A., & Ahmadian, L. (2013). Comparing academic self-concept and engagement to school between students with learning disabilities and normal. The Journal of Education and Learning Studies, 5 , 47–64.

Bingham, G. E., & Okagaki, L. (2012). Ethnicity and student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 65–95). Springer Science + Business Media). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_4

Chapter Google Scholar

Björklund, A., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Education and family background: Mechanisms and policies. In E. A. Hanushek, S. Machin, & L. Woessmann (Eds.), Handbook in economics of education (Vol. 3, pp. 201–247). Elsevier.

Blondal, K. S., & Adalbjarnardottir, S. (2014). Parenting in relation to school dropout through student engagement: A longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76 (4), 778–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12125

Bowers, A. J., & Sprott, R. (2012). Why tenth graders fail to finish high school: A dropout typology latent class analysis. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 17 (3), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2012.692071

Brault, M.-C., Janosz, M., & Archambault, I. (2014). Effects of school composition and school climate on teacher expectations of students: A multilevel analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 44 , 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.08.008

Brière, F. N., Pascal, S., Dupéré, V., Castellanos-Ryan, N., Allard, F., Yale-Soulière, G., & Janosz, M. (2017). Depressive and anxious symptoms and the risk of secondary school non-completion. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 211 , 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.117.201418

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children: Children and Poverty, 7 (2), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602387

Brozo, W. G., Sulkunen, S., Shiel, G., Garbe, C., Pandian, A., & Valtin, R. (2014). Reading, gender, and engagement. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 57 (7), 584–593. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.291

Buhs, E. S., Koziol, N. A., Rudasill, K. M., & Crockett, L. J. (2018). Early temperament and middle school engagement: School social relationships as mediating processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110 (3), 338–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000224

Buhs, E. S. (2005). Peer rejection, negative peer treatment, and school adjustment: Self-concept and classroom engagement as mediating processes. Journal of School Psychology, 43 (5), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.09.001

Cappella, E., Kim, H. Y., Neal, J. W., & Jackson, D. R. (2013). Classroom peer relationships and behavioral engagement in elementary school: The role of social network equity. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52 (3–4), 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9603-5

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Caraway, K., Tucker, C. M., Reinke, W. M., & Hall, C. (2003). Self-efficacy, goal orientation and fear of failure as predictors of school engagement in high school students. Psychology in the Schools, 40 (4), 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10092