- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Overcoming Speech Impediment: Symptoms to Treatment

There are many causes and solutions for impaired speech

- Types and Symptoms

- Speech Therapy

- Building Confidence

Speech impediments are conditions that can cause a variety of symptoms, such as an inability to understand language or speak with a stable sense of tone, speed, or fluidity. There are many different types of speech impediments, and they can begin during childhood or develop during adulthood.

Common causes include physical trauma, neurological disorders, or anxiety. If you or your child is experiencing signs of a speech impediment, you need to know that these conditions can be diagnosed and treated with professional speech therapy.

This article will discuss what you can do if you are concerned about a speech impediment and what you can expect during your diagnostic process and therapy.

FG Trade / Getty Images

Types and Symptoms of Speech Impediment

People can have speech problems due to developmental conditions that begin to show symptoms during early childhood or as a result of conditions that may occur during adulthood.

The main classifications of speech impairment are aphasia (difficulty understanding or producing the correct words or phrases) or dysarthria (difficulty enunciating words).

Often, speech problems can be part of neurological or neurodevelopmental disorders that also cause other symptoms, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) or autism spectrum disorder .

There are several different symptoms of speech impediments, and you may experience one or more.

Can Symptoms Worsen?

Most speech disorders cause persistent symptoms and can temporarily get worse when you are tired, anxious, or sick.

Symptoms of dysarthria can include:

- Slurred speech

- Slow speech

- Choppy speech

- Hesitant speech

- Inability to control the volume of your speech

- Shaking or tremulous speech pattern

- Inability to pronounce certain sounds

Symptoms of aphasia may involve:

- Speech apraxia (difficulty coordinating speech)

- Difficulty understanding the meaning of what other people are saying

- Inability to use the correct words

- Inability to repeat words or phases

- Speech that has an irregular rhythm

You can have one or more of these speech patterns as part of your speech impediment, and their combination and frequency will help determine the type and cause of your speech problem.

Causes of Speech Impediment

The conditions that cause speech impediments can include developmental problems that are present from birth, neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s disease , or sudden neurological events, such as a stroke .

Some people can also experience temporary speech impairment due to anxiety, intoxication, medication side effects, postictal state (the time immediately after a seizure), or a change of consciousness.

Speech Impairment in Children

Children can have speech disorders associated with neurodevelopmental problems, which can interfere with speech development. Some childhood neurological or neurodevelopmental disorders may cause a regression (backsliding) of speech skills.

Common causes of childhood speech impediments include:

- Autism spectrum disorder : A neurodevelopmental disorder that affects social and interactive development

- Cerebral palsy : A congenital (from birth) disorder that affects learning and control of physical movement

- Hearing loss : Can affect the way children hear and imitate speech

- Rett syndrome : A genetic neurodevelopmental condition that causes regression of physical and social skills beginning during the early school-age years.

- Adrenoleukodystrophy : A genetic disorder that causes a decline in motor and cognitive skills beginning during early childhood

- Childhood metabolic disorders : A group of conditions that affects the way children break down nutrients, often resulting in toxic damage to organs

- Brain tumor : A growth that may damage areas of the brain, including those that control speech or language

- Encephalitis : Brain inflammation or infection that may affect the way regions in the brain function

- Hydrocephalus : Excess fluid within the skull, which may develop after brain surgery and can cause brain damage

Do Childhood Speech Disorders Persist?

Speech disorders during childhood can have persistent effects throughout life. Therapy can often help improve speech skills.

Speech Impairment in Adulthood

Adult speech disorders develop due to conditions that damage the speech areas of the brain.

Common causes of adult speech impairment include:

- Head trauma

- Nerve injury

- Throat tumor

- Stroke

- Parkinson’s disease

- Essential tremor

- Brain tumor

- Brain infection

Additionally, people may develop changes in speech with advancing age, even without a specific neurological cause. This can happen due to presbyphonia , which is a change in the volume and control of speech due to declining hormone levels and reduced elasticity and movement of the vocal cords.

Do Speech Disorders Resolve on Their Own?

Children and adults who have persistent speech disorders are unlikely to experience spontaneous improvement without therapy and should seek professional attention.

Steps to Treating Speech Impediment

If you or your child has a speech impediment, your healthcare providers will work to diagnose the type of speech impediment as well as the underlying condition that caused it. Defining the cause and type of speech impediment will help determine your prognosis and treatment plan.

Sometimes the cause is known before symptoms begin, as is the case with trauma or MS. Impaired speech may first be a symptom of a condition, such as a stroke that causes aphasia as the primary symptom.

The diagnosis will include a comprehensive medical history, physical examination, and a thorough evaluation of speech and language. Diagnostic testing is directed by the medical history and clinical evaluation.

Diagnostic testing may include:

- Brain imaging , such as brain computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic residence imaging (MRI), if there’s concern about a disease process in the brain

- Swallowing evaluation if there’s concern about dysfunction of the muscles in the throat

- Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (aka nerve conduction velocity, or NCV) if there’s concern about nerve and muscle damage

- Blood tests, which can help in diagnosing inflammatory disorders or infections

Your diagnostic tests will help pinpoint the cause of your speech problem. Your treatment will include specific therapy to help improve your speech, as well as medication or other interventions to treat the underlying disorder.

For example, if you are diagnosed with MS, you would likely receive disease-modifying therapy to help prevent MS progression. And if you are diagnosed with a brain tumor, you may need surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation to treat the tumor.

Therapy to Address Speech Impediment

Therapy for speech impairment is interactive and directed by a specialist who is experienced in treating speech problems . Sometimes, children receive speech therapy as part of a specialized learning program at school.

The duration and frequency of your speech therapy program depend on the underlying cause of your impediment, your improvement, and approval from your health insurance.

If you or your child has a serious speech problem, you may qualify for speech therapy. Working with your therapist can help you build confidence, particularly as you begin to see improvement.

Exercises during speech therapy may include:

- Pronouncing individual sounds, such as la la la or da da da

- Practicing pronunciation of words that you have trouble pronouncing

- Adjusting the rate or volume of your speech

- Mouth exercises

- Practicing language skills by naming objects or repeating what the therapist is saying

These therapies are meant to help achieve more fluent and understandable speech as well as an increased comfort level with speech and language.

Building Confidence With Speech Problems

Some types of speech impairment might not qualify for therapy. If you have speech difficulties due to anxiety or a social phobia or if you don’t have access to therapy, you might benefit from activities that can help you practice your speech.

You might consider one or more of the following for you or your child:

- Joining a local theater group

- Volunteering in a school or community activity that involves interaction with the public

- Signing up for a class that requires a significant amount of class participation

- Joining a support group for people who have problems with speech

Activities that you do on your own to improve your confidence with speaking can be most beneficial when you are in a non-judgmental and safe space.

Many different types of speech problems can affect children and adults. Some of these are congenital (present from birth), while others are acquired due to health conditions, medication side effects, substances, or mood and anxiety disorders. Because there are so many different types of speech problems, seeking a medical diagnosis so you can get the right therapy for your specific disorder is crucial.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Language and speech disorders in children .

Han C, Tang J, Tang B, et al. The effectiveness and safety of noninvasive brain stimulation technology combined with speech training on aphasia after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(2):e36880. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000036880

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick statistics about voice, speech, language .

Mackey J, McCulloch H, Scheiner G, et al. Speech pathologists' perspectives on the use of augmentative and alternative communication devices with people with acquired brain injury and reflections from lived experience . Brain Impair. 2023;24(2):168-184. doi:10.1017/BrImp.2023.9

Allison KM, Doherty KM. Relation of speech-language profile and communication modality to participation of children with cerebral palsy . Am J Speech Lang Pathol . 2024:1-11. doi:10.1044/2023_AJSLP-23-00267

Saccente-Kennedy B, Gillies F, Desjardins M, et al. A systematic review of speech-language pathology interventions for presbyphonia using the rehabilitation treatment specification system . J Voice. 2024:S0892-1997(23)00396-X. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2023.12.010

By Heidi Moawad, MD Dr. Moawad is a neurologist and expert in brain health. She regularly writes and edits health content for medical books and publications.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Types of Speech Impediments

Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SanjanaGupta-d217a6bfa3094955b3361e021f77fcca.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Phynart Studio / Getty Images

Articulation Errors

Ankyloglossia, treating speech disorders.

A speech impediment, also known as a speech disorder , is a condition that can affect a person’s ability to form sounds and words, making their speech difficult to understand.

Speech disorders generally become evident in early childhood, as children start speaking and learning language. While many children initially have trouble with certain sounds and words, most are able to speak easily by the time they are five years old. However, some speech disorders persist. Approximately 5% of children aged three to 17 in the United States experience speech disorders.

There are many different types of speech impediments, including:

- Articulation errors

This article explores the causes, symptoms, and treatment of the different types of speech disorders.

Speech impediments that break the flow of speech are known as disfluencies. Stuttering is the most common form of disfluency, however there are other types as well.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Disfluencies

These are some of the characteristics of disfluencies:

- Repeating certain phrases, words, or sounds after the age of 4 (For example: “O…orange,” “I like…like orange juice,” “I want…I want orange juice”)

- Adding in extra sounds or words into sentences (For example: “We…uh…went to buy…um…orange juice”)

- Elongating words (For example: Saying “orange joooose” instead of "orange juice")

- Replacing words (For example: “What…Where is the orange juice?”)

- Hesitating while speaking (For example: A long pause while thinking)

- Pausing mid-speech (For example: Stopping abruptly mid-speech, due to lack of airflow, causing no sounds to come out, leading to a tense pause)

In addition, someone with disfluencies may also experience the following symptoms while speaking:

- Vocal tension and strain

- Head jerking

- Eye blinking

- Lip trembling

Causes of Disfluencies

People with disfluencies tend to have neurological differences in areas of the brain that control language processing and coordinate speech, which may be caused by:

- Genetic factors

- Trauma or infection to the brain

- Environmental stressors that cause anxiety or emotional distress

- Neurodevelopmental conditions like attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

Articulation disorders occur when a person has trouble placing their tongue in the correct position to form certain speech sounds. Lisping is the most common type of articulation disorder.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Articulation Errors

These are some of the characteristics of articulation disorders:

- Substituting one sound for another . People typically have trouble with ‘r’ and ‘l’ sounds. (For example: Being unable to say “rabbit” and saying “wabbit” instead)

- Lisping , which refers specifically to difficulty with ‘s’ and ‘z’ sounds. (For example: Saying “thugar” instead of “sugar” or producing a whistling sound while trying to pronounce these letters)

- Omitting sounds (For example: Saying “coo” instead of “school”)

- Adding sounds (For example: Saying “pinanio” instead of “piano”)

- Making other speech errors that can make it difficult to decipher what the person is saying. For instance, only family members may be able to understand what they’re trying to say.

Causes of Articulation Errors

Articulation errors may be caused by:

- Genetic factors, as it can run in families

- Hearing loss , as mishearing sounds can affect the person’s ability to reproduce the sound

- Changes in the bones or muscles that are needed for speech, including a cleft palate (a hole in the roof of the mouth) and tooth problems

- Damage to the nerves or parts of the brain that coordinate speech, caused by conditions such as cerebral palsy , for instance

Ankyloglossia, also known as tongue-tie, is a condition where the person’s tongue is attached to the bottom of their mouth. This can restrict the tongue’s movement and make it hard for the person to move their tongue.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Ankyloglossia

Ankyloglossia is characterized by difficulty pronouncing ‘d,’ ‘n,’ ‘s,’ ‘t,’ ‘th,’ and ‘z’ sounds that require the person’s tongue to touch the roof of their mouth or their upper teeth, as their tongue may not be able to reach there.

Apart from speech impediments, people with ankyloglossia may also experience other symptoms as a result of their tongue-tie. These symptoms include:

- Difficulty breastfeeding in newborns

- Trouble swallowing

- Limited ability to move the tongue from side to side or stick it out

- Difficulty with activities like playing wind instruments, licking ice cream, or kissing

- Mouth breathing

Causes of Ankyloglossia

Ankyloglossia is a congenital condition, which means it is present from birth. A tissue known as the lingual frenulum attaches the tongue to the base of the mouth. People with ankyloglossia have a shorter lingual frenulum, or it is attached further along their tongue than most people’s.

Dysarthria is a condition where people slur their words because they cannot control the muscles that are required for speech, due to brain, nerve, or organ damage.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Dysarthria

Dysarthria is characterized by:

- Slurred, choppy, or robotic speech

- Rapid, slow, or soft speech

- Breathy, hoarse, or nasal voice

Additionally, someone with dysarthria may also have other symptoms such as difficulty swallowing and inability to move their tongue, lips, or jaw easily.

Causes of Dysarthria

Dysarthria is caused by paralysis or weakness of the speech muscles. The causes of the weakness can vary depending on the type of dysarthria the person has:

- Central dysarthria is caused by brain damage. It may be the result of neuromuscular diseases, such as cerebral palsy, Huntington’s disease, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, or Lou Gehrig’s disease. Central dysarthria may also be caused by injuries or illnesses that damage the brain, such as dementia, stroke, brain tumor, or traumatic brain injury .

- Peripheral dysarthria is caused by damage to the organs involved in speech. It may be caused by congenital structural problems, trauma to the mouth or face, or surgery to the tongue, mouth, head, neck, or voice box.

Apraxia, also known as dyspraxia, verbal apraxia, or apraxia of speech, is a neurological condition that can cause a person to have trouble moving the muscles they need to create sounds or words. The person’s brain knows what they want to say, but is unable to plan and sequence the words accordingly.

Symptoms and Characteristics of Apraxia

These are some of the characteristics of apraxia:

- Distorting sounds: The person may have trouble pronouncing certain sounds, particularly vowels, because they may be unable to move their tongue or jaw in the manner required to produce the right sound. Longer or more complex words may be especially harder to manage.

- Being inconsistent in their speech: For instance, the person may be able to pronounce a word correctly once, but may not be able to repeat it. Or, they may pronounce it correctly today and differently on another day.

- Grasping for words: The person may appear to be searching for the right word or sound, or attempt the pronunciation several times before getting it right.

- Making errors with the rhythm or tone of speech: The person may struggle with using tone and inflection to communicate meaning. For instance, they may not stress any of the words in a sentence, have trouble going from one syllable in a word to another, or pause at an inappropriate part of a sentence.

Causes of Apraxia

Apraxia occurs when nerve pathways in the brain are interrupted, which can make it difficult for the brain to send messages to the organs involved in speaking. The causes of these neurological disturbances can vary depending on the type of apraxia the person has:

- Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS): This condition is present from birth and is often hereditary. A person may be more likely to have it if a biological relative has a learning disability or communication disorder.

- Acquired apraxia of speech (AOS): This condition can occur in adults, due to brain damage as a result of a tumor, head injury , stroke, or other illness that affects the parts of the brain involved in speech.

If you have a speech impediment, or suspect your child might have one, it can be helpful to visit your healthcare provider. Your primary care physician can refer you to a speech-language pathologist, who can evaluate speech, diagnose speech disorders, and recommend treatment options.

The diagnostic process may involve a physical examination as well as psychological, neurological, or hearing tests, in order to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other causes.

Treatment for speech disorders often involves speech therapy, which can help you learn how to move your muscles and position your tongue correctly in order to create specific sounds. It can be quite effective in improving your speech.

Children often grow out of milder speech disorders; however, special education and speech therapy can help with more serious ones.

For ankyloglossia, or tongue-tie, a minor surgery known as a frenectomy can help detach the tongue from the bottom of the mouth.

A Word From Verywell

A speech impediment can make it difficult to pronounce certain sounds, speak clearly, or communicate fluently.

Living with a speech disorder can be frustrating because people may cut you off while you’re speaking, try to finish your sentences, or treat you differently. It can be helpful to talk to your healthcare providers about how to cope with these situations.

You may also benefit from joining a support group, where you can connect with others living with speech disorders.

National Library of Medicine. Speech disorders . Medline Plus.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Language and speech disorders .

Cincinnati Children's Hospital. Stuttering .

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick statistics about voice, speech, and language .

Cleveland Clinic. Speech impediment .

Lee H, Sim H, Lee E, Choi D. Disfluency characteristics of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms . J Commun Disord . 2017;65:54-64. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2016.12.001

Nemours Foundation. Speech problems .

Penn Medicine. Speech and language disorders .

Cleveland Clinic. Tongue-tie .

University of Rochester Medical Center. Ankyloglossia .

Cleveland Clinic. Dysarthria .

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Apraxia of speech .

Cleveland Clinic. Childhood apraxia of speech .

Stanford Children’s Hospital. Speech sound disorders in children .

Abbastabar H, Alizadeh A, Darparesh M, Mohseni S, Roozbeh N. Spatial distribution and the prevalence of speech disorders in the provinces of Iran . J Med Life . 2015;8(Spec Iss 2):99-104.

By Sanjana Gupta Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

On this page:

What is stuttering?

Who stutters, how is speech normally produced, what are the causes and types of stuttering, how is stuttering diagnosed, how is stuttering treated, what research is being conducted on stuttering, where can i find additional information about stuttering.

Stuttering is a speech disorder characterized by repetition of sounds, syllables, or words; prolongation of sounds; and interruptions in speech known as blocks. An individual who stutters exactly knows what he or she would like to say but has trouble producing a normal flow of speech. These speech disruptions may be accompanied by struggle behaviors, such as rapid eye blinks or tremors of the lips. Stuttering can make it difficult to communicate with other people, which often affects a person’s quality of life and interpersonal relationships. Stuttering can also negatively influence job performance and opportunities, and treatment can come at a high financial cost.

Symptoms of stuttering can vary significantly throughout a person’s day. In general, speaking before a group or talking on the telephone may make a person’s stuttering more severe, while singing, reading, or speaking in unison may temporarily reduce stuttering.

Stuttering is sometimes referred to as stammering and by a broader term, disfluent speech .

Roughly 3 million Americans stutter. Stuttering affects people of all ages. It occurs most often in children between the ages of 2 and 6 as they are developing their language skills. Approximately 5 to 10 percent of all children will stutter for some period in their life, lasting from a few weeks to several years. Boys are 2 to 3 times as likely to stutter as girls and as they get older this gender difference increases; the number of boys who continue to stutter is three to four times larger than the number of girls. Most children outgrow stuttering. Approximately 75 percent of children recover from stuttering. For the remaining 25 percent who continue to stutter, stuttering can persist as a lifelong communication disorder.

We make speech sounds through a series of precisely coordinated muscle movements involving breathing, phonation (voice production), and articulation (movement of the throat, palate, tongue, and lips). Muscle movements are controlled by the brain and monitored through our senses of hearing and touch.

The precise mechanisms that cause stuttering are not understood. Stuttering is commonly grouped into two types termed developmental and neurogenic.

Developmental stuttering

Developmental stuttering occurs in young children while they are still learning speech and language skills. It is the most common form of stuttering. Some scientists and clinicians believe that developmental stuttering occurs when children’s speech and language abilities are unable to meet the child’s verbal demands. Most scientists and clinicians believe that developmental stuttering stems from complex interactions of multiple factors. Recent brain imaging studies have shown consistent differences in those who stutter compared to nonstuttering peers. Developmental stuttering may also run in families and research has shown that genetic factors contribute to this type of stuttering. Starting in 2010, researchers at the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) have identified four different genes in which mutations are associated with stuttering. More information on the genetics of stuttering can be found in the research section of this fact sheet.

Neurogenic stuttering

Neurogenic stuttering may occur after a stroke, head trauma, or other type of brain injury. With neurogenic stuttering, the brain has difficulty coordinating the different brain regions involved in speaking, resulting in problems in production of clear, fluent speech.

At one time, all stuttering was believed to be psychogenic, caused by emotional trauma, but today we know that psychogenic stuttering is rare.

Stuttering is usually diagnosed by a speech-language pathologist, a health professional who is trained to test and treat individuals with voice, speech, and language disorders. The speech-language pathologist will consider a variety of factors, including the child’s case history (such as when the stuttering was first noticed and under what circumstances), an analysis of the child’s stuttering behaviors, and an evaluation of the child’s speech and language abilities and the impact of stuttering on his or her life.

When evaluating a young child for stuttering, a speech-language pathologist will try to determine if the child is likely to continue his or her stuttering behavior or outgrow it. To determine this difference, the speech-language pathologist will consider such factors as the family’s history of stuttering, whether the child’s stuttering has lasted 6 months or longer, and whether the child exhibits other speech or language problems.

Although there is currently no cure for stuttering, there are a variety of treatments available. The nature of the treatment will differ, based upon a person’s age, communication goals, and other factors. If you or your child stutters, it is important to work with a speech-language pathologist to determine the best treatment options.

Therapy for children

For very young children, early treatment may prevent developmental stuttering from becoming a lifelong problem. Certain strategies can help children learn to improve their speech fluency while developing positive attitudes toward communication. Health professionals generally recommend that a child be evaluated if he or she has stuttered for 3 to 6 months, exhibits struggle behaviors associated with stuttering, or has a family history of stuttering or related communication disorders. Some researchers recommend that a child be evaluated every 3 months to determine if the stuttering is increasing or decreasing. Treatment often involves teaching parents about ways to support their child’s production of fluent speech. Parents may be encouraged to:

- Provide a relaxed home environment that allows many opportunities for the child to speak. This includes setting aside time to talk to one another, especially when the child is excited and has a lot to say.

- Listen attentively when the child speaks and focus on the content of the message, rather than responding to how it is said or interruptng the child.

- Speak in a slightly slowed and relaxed manner. This can help reduce time pressures the child may be experiencing.

- Listen attentively when the child speaks and wait for him or her to say the intended word. Don't try to complete the child’s sentences. Also, help the child learn that a person can communicate successfully even when stuttering occurs.

- Talk openly and honestly to the child about stuttering if he or she brings up the subject. Let the child know that it is okay for some disruptions to occur.

Stuttering therapy

Many of the current therapies for teens and adults who stutter focus on helping them learn ways to minimize stuttering when they speak, such as by speaking more slowly, regulating their breathing, or gradually progressing from single-syllable responses to longer words and more complex sentences. Most of these therapies also help address the anxiety a person who stutters may feel in certain speaking situations.

Drug therapy

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved any drug for the treatment of stuttering. However, some drugs that are approved to treat other health problems—such as epilepsy, anxiety, or depression—have been used to treat stuttering. These drugs often have side effects that make them difficult to use over a long period of time.

Electronic devices

Some people who stutter use electronic devices to help control fluency. For example, one type of device fits into the ear canal, much like a hearing aid, and digitally replays a slightly altered version of the wearer’s voice into the ear so that it sounds as if he or she is speaking in unison with another person. In some people, electronic devices may help improve fluency in a relatively short period of time. Additional research is needed to determine how long such effects may last and whether people are able to easily use and benefit from these devices in real-world situations. For these reasons, researchers are continuing to study the long-term effectiveness of these devices.

Self-help groups

Many people find that they achieve their greatest success through a combination of self-study and therapy. Self-help groups provide a way for people who stutter to find resources and support as they face the challenges of stuttering.

Researchers around the world are exploring ways to improve the early identification and treatment of stuttering and to identify its causes. For example, scientists have been working to identify the possible genes responsible for stuttering that tend to run in families. NIDCD scientists have now identified variants in four such genes that account for some cases of stuttering in many populations around the world, including the United States and Europe. All of these genes encode proteins that direct traffic within cells, ensuring that various cell components get to their proper location within the cell. Such deficits in cellular trafficking are a newly recognized cause of many neurological disorders. Researchers are now studying how this defect in cellular trafficking leads to specific deficits in speech fluency.

Researchers are also working to help speech-language pathologists determine which children are most likely to outgrow their stuttering and which children are at risk for continuing to stutter into adulthood. In addition, researchers are examining ways to identify groups of individuals who exhibit similar stuttering patterns and behaviors that may be associated with a common cause.

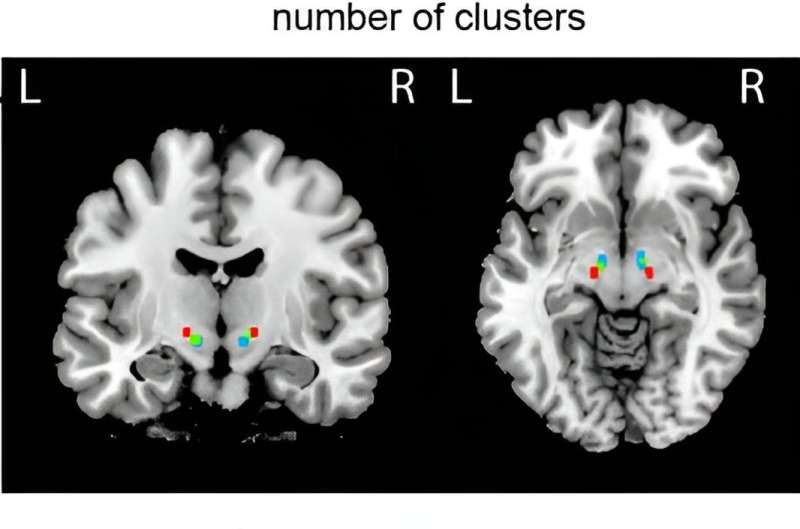

Scientists are using brain imaging tools such as PET (positron emission tomography) and functional MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans to investigate brain activity in people who stutter. NIDCD-funded researchers are also using brain imaging to examine brain structure and functional changes that occur during childhood that differentiate children who continue to stutter from those who recover from stuttering. Brain imaging may be used in the future as a way to help treat people who stutter. Researchers are studying whether volunteer patients who stutter can learn to recognize, with the help of a computer program, specific speech patterns that are linked to stuttering and to avoid using those patterns when speaking.

The NIDCD maintains a directory of organizations that provide information on the normal and disordered processes of hearing, balance, taste, smell, voice, speech, and language.

Use the following keywords to help you find organizations that can answer questions and provide information on stuttering:

- Speech-language pathologists

- Physician/practitioner referrals

For more information, contact us at:

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse 1 Communication Avenue Bethesda, MD 20892-3456 Toll-free voice: (800) 241-1044 Toll-free TTY: (800) 241-1055 Email: [email protected]

NIH Pub. No. 97-4232 February 2016

* Note: PDF files require a viewer such as the free Adobe Reader .

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Communication Skills

- Speaking Skills

How to Get Rid of a Speech Disorder

Last Updated: December 4, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Devin Fisher, CCC-SLP . Devin Fisher is a Speech-Language Pathologist based in Las Vegas, Nevada. Devin specializes in speech and language therapy for individuals with aphasia, swallowing, voice, articulation, phonological social-pragmatic, motor speech, and fluency disorders. Furthermore, Devin treats cognitive-communication impairment, language delay, and Parkinson's Disease. He holds a BS and MS in Speech-Language Pathology from Fontbonne University. Devin also runs a related website and blog that offers speech-language therapy resources and information for clinicians and clients. There are 13 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 330,690 times.

Many people feel insecure about their speech impediments, whether they're dealing with a lisp or an inability to articulate words. Although it may not seem like it—particularly if you have been dealing with this problem for years—you may be able to get rid of or improve your speech impediment with a few speech-training practices and some major confidence-boosters. And don't forget to seek out the professional opinion of a speech and language therapist/pathologist for more information.

Helping Yourself with a Speech Disorder

- One modern approach is to use technology. There are apps that can run on smartphones and tablets that listen to what you say and then give you feedback. For example, on Android there is the free app "Talking English." You can also find similar apps in the Apple App Store.

Stephanie Jeret

Cues and picture boards can help those with aphasia find words and express thoughts. For aphasia or trouble finding words, cues like the first sound can help jog your memory. Picture boards are great too, especially if speaking is very difficult. These tools allow people to communicate their needs and thoughts through other means.

Using Your Body to Improve Speech

- Shoulders relaxed

- Back straight

- Feet steady

- Sit comfortably and with an erect posture. Breathe in deeply through your nose. You should use your hand to feel your stomach expanding like a balloon being inflated. Hold the breath and then release it slowly, feeling your stomach deflating beneath your hand. Repeat this exercise before you have to speak publicly to relieve stress.

Getting Professional Help

- Speech therapy is helpful for correcting your impediment. The therapist will point out the part of speech where you're having problems, and will work with you to correct it. Private speech therapy sessions do not come cheap, although most insurance policies will fund services needed to treat speech disorders.

- There's no substitute for learning and practice when it comes to the proper and effective use of language. Take every opportunity to speak, to practice and brush up on the correct pronunciation and enunciation provided to you by a professional.

- Every time the dentist adjusts your braces (or even dentures), you need to train yourself to talk and to eat properly. It may be quite painful at first, but remember not to go too far, lest you end up with a mouth injury.

- Most braces are used for orthodontic purposes, although some braces can be used as decorations. Braces are rather expensive, and you may need to take out a dental plan or cash in on dental insurance to pay for them.

- Kids and teenagers don't like to wear braces because they're often teased as “metal mouths” or “railroad faces.” The fact is that braces are still the best way to correct a lisp caused by misaligned teeth.

Assessing Your Speech Disorder

- Cleft lips and palates were a major cause of speech impediments until surgery became affordable. Now, children born with clefts can have reconstructive surgery and a multidisciplinary team of providers that help with feeding and speech and language development. [14] X Research source

- Malocclusion is when the teeth do not have the proper normal bite. Malocclusions are usually corrected through braces, although orthodontic surgery is necessary in some cases. Individuals with this condition may talk with a lisp, make a whistle sound when certain words are spoken, or mumble.

- Neurological disorders caused by accidents or brain and nerve tumors can cause a speech disorder called dysprosody. Dysprosody involves difficulty in expressing the tonal and emotional qualities of speech such as inflection and emphasis.

Expert Q&A

- Welcome good speech. Look forward to it, and accept and celebrate even little improvements. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Try to slow down and pronounce each word properly, as this can also help when trying to overcome a speech problem. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- See a Speech Pathologist who maintains their Certification of Clinical Competence from the American Speech and Hearing Association. These professionals are able to evaluate, diagnose and treat speech impairments. Nothing replaces sound medical advice from a specialist. Thanks Helpful 11 Not Helpful 14

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/2018-10/Camperdown%20Program%20Treatment%20Guide%20June%202018.pdf

- ↑ Devin Fisher, CCC-SLP. Speech Language Pathologist. Expert Interview. 15 January 2021.

- ↑ https://www.stutteringhelp.org/sites/default/files/Migrate/Book_0012_tenth_ed.pdf

- ↑ http://www.coli.uni-saarland.de/~steiner/publications/ISSP2014.pdf

- ↑ https://sps.columbia.edu/news/five-ways-improve-your-body-language-during-speech

- ↑ https://www.nhs.uk/mental-health/self-help/guides-tools-and-activities/breathing-exercises-for-stress/

- ↑ http://kidshealth.org/teen/diseases_conditions/sight/speech_disorders.html#

- ↑ https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/stuttering

- ↑ https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001058.htm

- ↑ http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/CleftLip/

- ↑ https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/developmentaldisabilities/language-disorders.html

- ↑ https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=stuttering-90-P02290

- ↑ https://raisingchildren.net.au/preschoolers/development/language-development/stuttering

About This Article

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Bikash Pokharel

Apr 23, 2017

Did this article help you?

Mar 28, 2016

Manisha Singh

Feb 22, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Childhood apraxia of speech

Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) is a rare speech disorder. Children with this disorder have trouble controlling their lips, jaws and tongues when speaking.

In CAS , the brain has trouble planning for speech movement. The brain isn't able to properly direct the movements needed for speech. The speech muscles aren't weak, but the muscles don't form words the right way.

To speak correctly, the brain has to make plans that tell the speech muscles how to move the lips, jaw and tongue. The movements usually result in accurate sounds and words spoken at the proper speed and rhythm. CAS affects this process.

CAS is often treated with speech therapy. During speech therapy, a speech-language pathologist teaches the child to practice the correct way to say words, syllables and phrases.

Children with childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) may have a variety of speech symptoms. Symptoms vary depending on a child's age and the severity of the speech problems.

CAS can result in:

- Babbling less or making fewer vocal sounds than is typical between the ages of 7 to 12 months.

- Speaking first words late, typically after ages 12 to 18 months old.

- Using a limited number of consonants and vowels.

- Often leaving out sounds when speaking.

- Using speech that is hard to understand.

These symptoms are usually noticed between ages 18 months and 2 years. Symptoms at this age may indicate suspected CAS . Suspected CAS means a child may potentially have this speech disorder. The child's speech development should be watched to determine if therapy should begin.

Children usually produce more speech between ages 2 and 4. Signs that may indicate CAS include:

- Vowel and consonant distortions.

- Pauses between syllables or words.

- Voicing errors, such as "pie" sounding like "bye."

Many children with CAS have trouble getting their jaws, lips and tongues to the correct positions to make a sound. They also may have a hard time moving smoothly to the next sound.

Many children with CAS also have language problems, such as reduced vocabulary or trouble with word order.

Some symptoms may be unique to children with CAS , which helps to make a diagnosis. However, some symptoms of CAS are also symptoms of other types of speech or language disorders. It's hard to diagnose CAS if a child has only symptoms that are found both in CAS and in other disorders.

Some characteristics, sometimes called markers, help distinguish CAS from other types of speech disorders. Those associated with CAS include:

- Trouble moving smoothly from one sound, syllable or word to another.

- Groping movements with the jaw, lips or tongue to try to make the correct movement for speech sounds.

- Vowel distortions, such as trying to use the correct vowel but saying it incorrectly.

- Using the wrong stress in a word, such as pronouncing "banana" as "BUH-nan-uh" instead of "buh-NAN-uh."

- Using equal emphasis on all syllables, such as saying "BUH-NAN-UH."

- Separation of syllables, such as putting a pause or gap between syllables.

- Inconsistency, such as making different errors when trying to say the same word a second time.

- Having a hard time imitating simple words.

- Voicing errors, such as saying "down" instead of "town."

Other speech disorders sometimes confused with CAS

Some speech sound disorders often get confused with CAS because some of the symptoms may overlap. These speech sound disorders include articulation disorders, phonological disorders and dysarthria.

A child with an articulation or phonological disorder has trouble learning how to make and use specific sounds. Unlike in CAS , the child doesn't have trouble planning or coordinating the movements to speak. Articulation and phonological disorders are more common than CAS .

Articulation or phonological speech errors may include:

- Substituting sounds. The child might say "fum" instead of "thumb," "wabbit" instead of "rabbit" or "tup" instead of "cup."

- Leaving out final consonants. A child with CAS might say "duh" instead of "duck" or "uh" instead of "up."

- Stopping the airstream. The child might say "tun" instead of "sun" or "doo" instead of "zoo."

- Simplifying sound combinations. The child might say "ting" instead of "string" or "fog" instead of "frog."

Dysarthria is a speech disorder that occurs because the speech muscles are weak. Making speech sounds is hard because the speech muscles can't move as far, as quickly or as strongly as they do during typical speech. People with dysarthria may also have a hoarse, soft or even strained voice. Or they may have slurred or slow speech.

Dysarthria is often easier to identify than CAS . However, when dysarthria is caused by damage to areas of the brain that affect coordination, it can be hard to determine the differences between CAS and dysarthria.

Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) has a number of possible causes. But often a cause can't be determined. There usually isn't an observable problem in the brain of a child with CAS .

However, CAS can be the result of brain conditions or injury. These may include a stroke, infections or traumatic brain injury.

CAS also may occur as a symptom of a genetic disorder, syndrome or metabolic condition.

CAS is sometimes referred to as developmental apraxia. But children with CAS don't make typical developmental sound errors and they don't grow out of CAS . This is unlike children with delayed speech or developmental disorders who typically follow patterns in speech and sounds development but at a slower pace than usual.

Risk factors

Changes in the FOXP2 gene appear to increase the risk of childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) and other speech and language disorders. The FOXP2 gene may be involved in how certain nerves and pathways in the brain develop. Researchers continue to study how changes in the FOXP2 gene may affect motor coordination and speech and language processing in the brain. Other genes also may impact motor speech development.

Complications

Many children with childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) have other problems that affect their ability to communicate. These problems aren't due to CAS , but they may be seen along with CAS .

Symptoms or problems that are often present along with CAS include:

- Delayed language. This may include trouble understanding speech, reduced vocabulary, or not using correct grammar when putting words together in a phrase or sentence.

- Delays in intellectual and motor development and problems with reading, spelling and writing.

- Trouble with gross and fine motor movement skills or coordination.

- Trouble using communication in social interactions.

Diagnosing and treating childhood apraxia of speech at an early stage may reduce the risk of long-term persistence of the problem. If your child experiences speech problems, have a speech-language pathologist evaluate your child as soon as you notice any speech problems.

Childhood apraxia of speech care at Mayo Clinic

- Jankovic J, et al., eds. Dysarthria and apraxia of speech. In: Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2022. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 6, 2023.

- Carter J, et al. Etiology of speech and language disorders in children. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 6, 2023.

- Childhood apraxia of speech. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. https://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/childhood-apraxia-of-speech/. Accessed April 6, 2023.

- Apraxia of speech. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/voice/pages/apraxia.aspx. Accessed April 6, 2023.

- Ng WL, et al. Predicting treatment of outcomes in rapid syllable transition treatment: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 2022; doi:10.1044/2022_JSLHR-21-00617.

- Speech sound disorders. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/SpeechSoundDisorders/. Accessed April 6, 2023.

- Iuzzini-Seigel J. Prologue to the forum: Care of the whole child — Key considerations when working with children with childhood apraxia of speech. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools. 2022; doi:10.1044/2022_LSHSS-22-00119.

- Namasivayam AK, et al. Speech sound disorders in children: An articulatory phonology perspective. 2020; doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02998.

- Strand EA. Dynamic temporal and tactile cueing: A treatment strategy for childhood apraxia of speech. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2020; doi:10.1044/2019_AJSLP-19-0005.

- Ami TR. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. March 13, 2023.

- Kliegman RM, et al. Language development and communication disorders. In: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 6, 2023.

- Adam MP, et al., eds. FOXP2-related speech and language disorder. In: GeneReviews. University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1116. Accessed April 6, 2023.

- How is CAS diagnosed? Childhood Apraxia of Speech Association of North America. https://www.apraxia-kids.org/apraxia_kids_library/how-is-cas-diagnosed/. Accessed April 13, 2023.

- Chenausky KV, et al. The importance of deep speech phenotyping for neurodevelopmental and genetic disorders: A conceptual review. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2022; doi:10.1186/s11689-022-09443-z.

- Strand EA. Dynamic temporal and tactile cueing: A treatment strategy for childhood apraxia of speech. American Journal of Speech Language Pathology. 2020; doi:10.1044/2019_AJSLP-19-0005.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Health Conditions

- Health Products

How to stop or reduce a stutter

Stuttering is a speech disorder. There are various ways to stop or reduce a stutter. These include mindfulness, avoiding triggering words, and speech therapy.

Stuttering affects more than 70 million people worldwide, including more than 3 million people in the United States. It is more common among men than women. Some people refer to stuttering as stammering or childhood onset fluency disorder.

People who stutter may repeat sounds, syllables, or words, or they may prolong sounds. There may also be interruptions to the typical flow of speech, known as blocks, along with unusual expressions or movements.

Approximately 5–10% of all children will stutter at some point in their lives, but most will typically outgrow this within a few months or years. Early intervention can help children overcome stuttering.

For 1 in 4 of these children, however, the problem will persist into adulthood and can become a lifelong communication disorder.

In this article, we describe strategies that people who stutter can use to try to reduce these speech disruptions. We also list ways in which parents and caregivers can help children overcome a stutter.

Quick tips for reducing stuttering

There is no instant cure for stuttering. However, certain situations — such as stress , fatigue , or pressure — can make stuttering worse. By managing these situations, as far as possible, people may be able to improve their flow of speech.

With this in mind, the following tips may be useful:

Practice speaking slowly

Speaking slowly and deliberately can reduce stress and the symptoms of a stutter. It can be helpful to practice speaking slowly every day.

For example, people could try reading aloud at a slow pace when they are on their own. Then, when they have mastered this, they can use this pace when speaking to others.

Another option is to add a brief pause between phrases and sentences to help slow down speech.

Avoid trigger words

People who stutter should not feel as though they have to stop using particular words if this is not their preference.

However, some people may wish to avoid specific words that tend to cause them to stammer. In this case, it might be helpful to make a list of these words and find alternatives to use.

Try mindfulness

Mindfulness is a proven way to reduce anxiety and stress. Research suggests that there is an overlap between the effects of mindfulness and the tools necessary for stuttering management, including:

- decreased use of avoidance strategies, such as speaking less

- improved emotional control

According to the authors of a 2018 case study , adding mindfulness meditation to a treatment program for stuttering may be beneficial for some people.

To practice mindfulness, consider joining a class, downloading a smartphone app, or watching videos online.

Long term treatments

Treatment usually works best when people begin to address stuttering at an early stage. The parents and caregivers of children who stutter should consider taking a child to see a speech therapist if:

- they have stuttered for 3–6 months

- they show signs of struggling with stuttering, such as lip tremors

- there is a family history of stuttering or other communication disorders

Although it may not stop stuttering completely, treatment at any age aims to improve speech fluency, build the person’s confidence, and help them participate in school, work, and social settings.

Treatments for stuttering include:

Speech therapy

A speech therapist can teach people to:

- slow down their rate of speech

- notice when they stutter

- manage situations in which stuttering gets worse

- work on a fluid speech pattern

Research suggests that speech therapy is the best treatment for both adults and children who stutter, with a large body of evidence supporting its efficacy.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

CBT is a type of psychotherapy that helps people change how they think and alter their behavior accordingly. CBT for stuttering may involve:

- direct communication

- educating the person about stuttering

- problem solving

- exercises to extend the length of sounds

- relaxation techniques, including deep breathing

- challenging unhelpful thoughts

CBT may lead to positive changes in thoughts and attitudes around stuttering and reduce stuttering-related anxiety.

Electronic devices

Electronic devices are available to help people manage their speech and improve their fluency. Some of these devices work by assisting people in slowing down their speech. Others mimic speech so that it sounds as though the person is talking in unison with someone else.

According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders , speaking in unison with someone else may temporarily reduce a person’s stuttering.

Some of the medications that doctors prescribe for stuttering include:

- alprazolam (Xanax), an anti-anxiety drug

- citalopram ( Celexa ), an antidepressant

- clomipramine (Anafranil), another antidepressant

However, The Stuttering Foundation advise that these drugs are not effective for the majority of people. Even when they do work, people report the improvements as being modest.

The National Stuttering Foundation suggest that medications may work best when people combine their use with speech therapy.

It is important that parents and caregivers support children who stutter. They can do this by:

- listening attentively and using appropriate eye contact

- refraining from completing words or phrases for a child

- avoiding interrupting, correcting, or criticizing a child

- avoiding focusing on the stutter and using phrases such as “slow down” or “take your time,” as these can make a child feel more self-conscious

- speaking slowly and deliberately to children who stutter, as they may mirror the adult’s pace when they speak

- minimizing stress in the home, as stress can make stuttering worse

- reducing a child’s exposure to situations in which they feel pressured or rushed and those that require them to speak in front of others

- speaking to a teacher if bullying is occurring in school as a result of a child’s stutter

Self-help groups

Connecting with others who stutter can be beneficial for many people. Self-help groups enable people to discover additional resources and supports for stuttering.

For more information, see the National Stuttering Association’s list of local chapters .

Stuttering causes

Researchers do not understand the exact cause of stuttering. Based on current knowledge, they typically class stuttering as one of the following types:

Developmental

Developmental stuttering is the most common type . It occurs in young children who are learning language skills. It is likely to be the result of multiple factors, including genetics.

Due to its genetic component, developmental stuttering can run in families. Approximately 60% of people who stutter have a family member who also stutters.

Neurogenic stuttering can occur due to brain trauma, such as that resulting from a stroke or head injury. The brain then struggles to coordinate the mechanisms that speech involves.

Psychogenic

In the past, scientists believed that all stuttering was psychogenic, meaning that it was due to emotional trauma. Now, they consider this type of stuttering to be rare .

Can a stutter be cured?

There is no cure for stuttering, although early treatment may stop childhood stuttering from persisting into adulthood.

A variety of treatments can help those with a lifelong stutter manage their speech and reduce the frequency and severity of stuttering.

Early intervention is important for children who stutter, most of whom will eventually outgrow it. About 25% will continue to experience stuttering throughout their adult lives, however.

While there is no cure for stuttering, speech therapy can be particularly effective in helping people gain control over their speech. CBT and mindfulness interventions may also help with some aspects of stuttering.

Researchers are continuing to explore the causes of stuttering and potential treatment options. In time, they may be able to identify the children who are more likely to continue stuttering in adulthood.

If scientists can understand the underlying cause of stuttering, they may be able to identify more effective medications or other treatments.

Last medically reviewed on September 9, 2019

- Pediatrics / Children's Health

- Psychology / Psychiatry

- Rehabilitation / Physical Therapy

How we reviewed this article:

- Bernstein Ratner, N. (2014). Stress & stuttering. https://www.stutteringhelp.org/stress-stuttering

- Blomgren, M. (2013). Behavioral treatments for children and adults who stutter: A review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3682852/

- Boyle, M. P. (2011). Mindfulness training in stuttering therapy: A tutorial for speech-language pathologists [Abstract]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21664530

- Brady, J. P., & Ali, Z. (2000). Alprazolam, citalopram, and clomipramine for stuttering. https://www.stutteringhelp.org/alprazolam-citalopram-and-clomipramine-stuttering

- Emge, G., & Pellowski, M. W. (2018). Incorporating a mindfulness meditation exercise into a stuttering treatment program [Abstract]. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1525740118783516?journalCode=cdqc

- F.A.Q.: Stuttering facts and information. (n.d.). https://www.stutteringhelp.org/faq

- Maguire, J. A. (n.d.). Pharmaceuticals for stuttering. https://westutter.org/what-is-stuttering/resources/pharmaceuticals-for-stuttering/

- Perez, H. R., & Stoeckle, J. H. (2016). Stuttering: Clinical and research update. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4907555/

- Reddy, R. P., et al. (2010). Cognitive behavior therapy for stuttering: A case series. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3137813/

- Stuttering. (2017). https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/stuttering

Share this article

Latest news

- Parkinson's: Caffeine may lower risk but doesn't slow progression

- Tattoos may increase blood cancer risk by 21%

- Flavonoid-rich foods and drinks tied to an up to 28% lower risk of type 2 diabetes

- In Conversation: What makes a diet truly heart-healthy?

- Nightmares, 'daymares' could be tell-tale signs of autoimmune disease

Related Coverage

Stuttering, or stammering, is a disruption in speech that causes people to repeat or prolong words, syllables, or phrases. Learn more here.

Even when hiccups last for just a few minutes, they can be annoying. If they last for over 48 hours, they are known as chronic hiccups. Chronic…

Speech therapy provides treatment and support for people with speech disorders and communication problems. Learn more here.

Eye twitching is very common and usually goes away on its own. Learn how to stop eye twitching more quickly and why it happens here.

What is face blindness? Read on to learn more about this neurological condition, including the different types, causes, symptoms, and management…

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Sitio para padres

- Parents Home

- General Health

- Growth & Development

- Diseases & Conditions

- Pregnancy & Baby

- Nutrition & Fitness

- Emotions & Behavior

- School & Family Life

- First Aid & Safety

- Doctors & Hospitals

- Expert Answers (Q&A)

- All Categories

- All Wellness Centers

- Sitio para niños

- How the Body Works

- Puberty & Growing Up

- Staying Healthy

- Staying Safe

- Health Problems

- Illnesses & Injuries

- Relax & Unwind

- People, Places & Things That Help

- Sitio para adolescentes

- Sexual Health

- Food & Fitness

- Drugs & Alcohol

- School & Jobs

Speech Problems

- Listen Play Stop Volume mp3 Settings Close Player

- Larger text size Large text size Regular text size

When you were younger and first began talking, you may have lisped, stuttered, or had a hard time pronouncing words. Maybe you were told that it was "cute," or not to worry because you would soon grow out of it. But if you're in your teens and still stuttering, you may not feel like it's so endearing.

You're not alone. More than 3 million Americans have the speech disorder known as stuttering (or stammering, as it's known in Britain). It's one of several conditions that can affect a person's ability to speak clearly.

Some Common Speech and Language Disorders

Stuttering is a problem that interferes with fluent (flowing and easy) speech. A person who stutters may repeat the first part of a word (as in wa-wa-wa-water ) or hold a single sound for a long time (as in caaaaaaake ). Some people who stutter have trouble getting sounds out altogether. Stuttering is complex, and it can affect speech in many different ways.

Articulation disorders involve a wide range of errors people can make when talking. Substituting a "w" for an "r" ("wabbit" for "rabbit"), omitting sounds ("cool" for "school"), or adding sounds to words ("pinanio" for "piano") are examples of articulation errors. Lisping refers to specific substitution involving the letters "s" and "z." A person who lisps replaces those sounds with "th" ("simple" sounds like "thimple").

Cluttering is another problem that makes a person's speech difficult to understand. Like stuttering, cluttering affects the fluency, or flow, of a person's speech. The difference is that stuttering is a speech disorder , while cluttering is a language disorder. People who stutter have trouble getting out what they want to say; those who clutter say what they're thinking, but it becomes disorganized as they're speaking. So, someone who clutters may speak in bursts or pause in unexpected places. The rhythm of cluttered speech may sound jerky, rather than smooth, and the speaker is often unaware of the problem.

Apraxia (also known as verbal apraxia or dyspraxia) is an oral-motor speech disorder. People with this problem have difficulty moving the muscles and structures needed to form speech sounds into words.

What Causes Speech Problems?

Normal speech might seem effortless, but it's actually a complex process that needs precise timing, and nerve and muscle control.

When we speak, we must coordinate many muscles from various body parts and systems, including the larynx, which contains the vocal cords; the teeth, lips, tongue, and mouth; and the respiratory system .

The ability to understand language and produce speech is coordinated by the brain. So a person with brain damage from an accident, stroke, or birth defect may have speech and language problems.

Some people with speech problems, particularly articulation disorders, may also have hearing problems. Even mild hearing loss can affect how people reproduce the sounds they hear. Certain birth defects, such as a cleft palate, can interfere with someone's ability to produce speech. People with a cleft palate have a hole in the roof of the mouth (which affects the movement of air through the oral and nasal passages), and also might have problems with other structures needed for speech, including the lips, teeth, and jaw.

Some speech problems, like stuttering, can run in families. But in some cases, no one knows exactly what causes a person to have speech problems.

How Are Speech Problems Treated?

The good news is that treatments like speech therapy can help people of any age overcome some speech problems.

If you are concerned about your speech, it's important to let your parents and doctor know. If hearing tests and physical exams don't reveal any problems, some doctors arrange a consultation with a speech-language pathologist (pronounced: puh-THOL-uh-jist).

A speech-language pathologist is trained to observe people as they speak and to identify their speech problems. Speech-language pathologists look for the type of problem (such as a lack of fluency, articulation, or motor skills) someone has. For example, if you stutter, the pathologist will examine how and when you do so.

Speech-language pathologists may evaluate their clients' speech either by recording them on audio or videotape or by listening during conversation. A few clinics that specialize in fluency disorders may use computerized analysis. By gathering as much information as possible about the way someone speaks, the pathologist can develop a treatment plan that meets each individual's needs. The plan will depend on things like a person's age and the type of speech disorder.

If you're being treated for a speech disorder, part of your treatment plan may include seeing a speech therapist , a person who is trained to treat speech disorders.

How often you have to see the speech therapist will vary — you'll probably start out seeing him or her fairly often at first, then your visits may decrease over time. Most treatment plans include breathing techniques, relaxation strategies that are designed to help you relax your muscles when you speak, posture control, and a type of voice exercise called oral-motor exercises . You'll probably have to do these exercises each day on your own to help make your treatment plan as successful as possible.

Dealing With a Speech Problem

People with speech problems know how frustrating they can be. People who stutter, for example, often complain that others try to finish their sentences or fill in words for them. Some feel like people treat them as if they're stupid, especially when a listener says things like "slow down" or "take it easy." (People who stutter are just as intelligent as people who don't.) People who stutter report that listeners often avoid eye contact and refuse to wait patiently for them to finish speaking. If you have a speech problem, it's fine to let others know how you like to be treated when speaking.

Some people look to their speech therapists for advice and resources on issues of stuttering. Your speech therapist might be able to connect you with others in similar situations, such as support groups in your area for teens who stutter.

If you have a speech problem, achieving and keeping control of your speech might be a lifelong process. Although speech therapy can help, you are sure to have ups and downs in your efforts to communicate. But the truth is that the way you speak is only a small part of who you are. Don't be embarrassed to make yourself heard!

- Speech Pathology Master’s Programs: Which is Right for You?

- What Can You Do with a Bachelor’s in Speech Pathology?

- Speech Pathology Doctoral Programs

- Online Masters in Speech Pathology at Emerson College (sponsored program)

- Online Masters in Speech Pathology at New York University (sponsored program)

- How to Become a Speech Pathologist: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Guide to Applying to Speech Pathology School

- How to Make a Career Change to Speech Pathology

- Is a Speech Pathology Degree Worth It?

- 10 Reasons to Love Being a Speech Pathologist

- What Is a CCC-SLP and Why It’s Important

- CCC-SLP Requirements: Become a CCC-SLP

- Guide to Applying for CCC-SLP Certification

- CCC-SLP Salary and Career Outlook

- The Guide to the ASHA Speech Pathology Certification Standards

- State-by-State Guide for Speech Pathology License Requirements

- 8 SLP Certifications that May Help Advance Your Career

- How to Become an Effective ASHA Clinical Fellowship Mentor

- How to Complete the ASHA Clinical Fellowship

- The Guide to Speech Pathology Job and Salary Negotiations

- What to Expect at Your First Speech Pathologist Job

- Bilingual Speech Pathologist Salary and Careers

- Child Speech Therapist Career and Salary Outlook

- Speech Pathology Assistant Careers and Salary Outlook

- How to Choose Your Speech Pathologist Career Setting

- Become a Speech Pathologist in a School Setting

- Become a Speech Pathologist in a Hospital Work Setting

- Opening a Speech Therapy Telepractice: What You Need to Know

- Speech Pathology Internships Guide

- Guide to Speech Therapy Volunteer Opportunities

- Choosing Between Speech Pathology or Occupational Therapy

- How to Become an Audiologist

- Scholarships

- Day in the Life of an SLP Student

- Speech Disorder Resources for College Students

- Common Speech Language Pathology Assessment Tools

- The SLP Guide to Evidence-Based Practice

- When to Take Your Bilingual Child to the Speech Pathologist

- When to Take Your Child to the SLP

Home / Resources

What are the Most Common Speech Disorders?

July 24, 2020

Speech disorders impact millions of people and their ability to communicate. The National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders estimates that 5% of children in the U.S. ages 3 to 17 have had a speech disorder in the past 12 months. Some speech disorders can be overcome, while others are lifelong conditions. In either case, therapy with a speech pathologist can help a person make the most of their speech capabilities and develop alternative methods of communication.

Speech pathologists or speech therapists complete a master’s program to be able to evaluate a person’s speech and communication, create a treatment plan and provide treatment to improve a person’s speech and other communication methods. Some speech pathologists’ careers deal with research and development treatment guidelines for various speech and language disorders.

What Is a Speech Disorder?

Speech is how people make sounds and words , according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). Speech problems can include the inability to make sounds clearly, having a raspy voice or stuttering (repeating sounds or pauses when speaking).

Language is not the same thing as speech; it is the words we use to share ideas. Problems with language can include difficulty understanding, talking, reading or writing.

According to ASHA, a speech disorder is an impairment of the articulation of sounds, fluency or voice. It is one of many types of communication disorders, which also include language and hearing disorders.

Types of Speech Disorders

There are three categories of speech disorders :

- Articulation disorders : An unusual production of speech sounds involving substitutions, omissions, additions or distortions that might interfere with whether the sounds are intelligible to others.

- Fluency disorders : Interruptions in the flow of a person’s speech, such as an uncommon rate, rhythm, or repetition of sounds, syllables, words or phrases.

- Voice disorders : An abnormal production or absence of vocal quality, pitch, volume, resonance or duration that’s inappropriate for the person’s age and sex.

Speech Disorder Causes

The medical community doesn’t know the cause of all speech disorders and, for many, the cause can vary. Potential causes for speech disorders include: