What Is Sexism? Defining a Key Feminist Term

Compassionate Eye Foundation / Monashee Frantz / Getty Images

- History Of Feminism

- Important Figures

- Women's Suffrage

- Women & War

- Laws & Womens Rights

- Feminist Texts

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- J.D., Hofstra University

- B.A., English and Print Journalism, University of Southern California

Sexism means discrimination based on sex or gender, or the belief that because men are superior to women, discrimination is justified. Such a belief can be conscious or unconscious . In sexism, as in racism, the differences between two (or more) groups are viewed as indications that one group is superior or inferior. Sexist discrimination against girls and women is a means of maintaining male domination and power. The oppression or discrimination can be economic, political, social, or cultural.

Elements of Sexism

- Sexism includes attitudes or ideology, including beliefs, theories, and ideas that hold one group (usually male) as deservedly superior to the other (usually female), and that justify oppressing members of the other group on the basis of their sex or gender.

- Sexism involves practices and institutions and the ways in which oppression is carried out. These need not be done with a conscious sexist attitude but may be unconscious cooperation in a system that has been in place already in which one sex (usually female) has less power and fewer goods in the society.

Oppression and Domination

Sexism is a form of oppression and domination. As author Octavia Butler put it:

"Simple peck-order bullying is only the beginning of the kind of hierarchical behavior that can lead to racism, sexism, ethnocentrism, classism, and all the other 'isms' that cause so much suffering in the world."

Some feminists have argued that sexism is the primal, or first, form of oppression in humanity and that other oppressions are built on the foundation of oppression of women. Feminist Andrea Dworkin holds that position, stating:

"Sexism is the foundation on which all tyranny is built. Every social form of hierarchy and abuse is modeled on male-over-female domination."

Feminist Origins of the Word

The word "sexism" became widely known during the women's liberation movement of the 1960s. At that time, feminist theorists explained that the oppression of women was widespread in nearly all human society, and they began to speak of sexism instead of male chauvinism. Whereas male chauvinists were usually individual men who expressed the belief that they were superior to women, sexism referred to collective behavior that reflected society as a whole.

Australian writer Dale Spender noted that she was:

"...old enough to have lived in a world without sexism and sexual harassment. Not because they weren’t everyday occurrences in my life but because THESE WORDS DIDN’T EXIST. It was not until the feminist writers of the 1970s made them up, and used them publicly and defined their meanings—an opportunity that men had enjoyed for centuries—that women could name these experiences of their daily life."

Many women in the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s (the so-called second wave of feminism) came to their consciousness of sexism via their work in social justice movements. Social philosopher Bell Hooks argues:

"Individual heterosexual women came to the movement from relationships where men were cruel, unkind, violent, unfaithful. Many of these men were radical thinkers who participated in movements for social justice, speaking out on behalf of the workers, the poor, speaking out on behalf of racial justice. However, when it came to the issue of gender they were as sexist as their conservative cohorts."

How Sexism Works

Systemic sexism, like systemic racism, is the perpetuation of the oppression and discrimination without necessarily any conscious intention. The disparities between men and women are simply taken as givens and are reinforced by practices, rules, policies, and laws that often seem neutral on the surface but in fact disadvantage women.

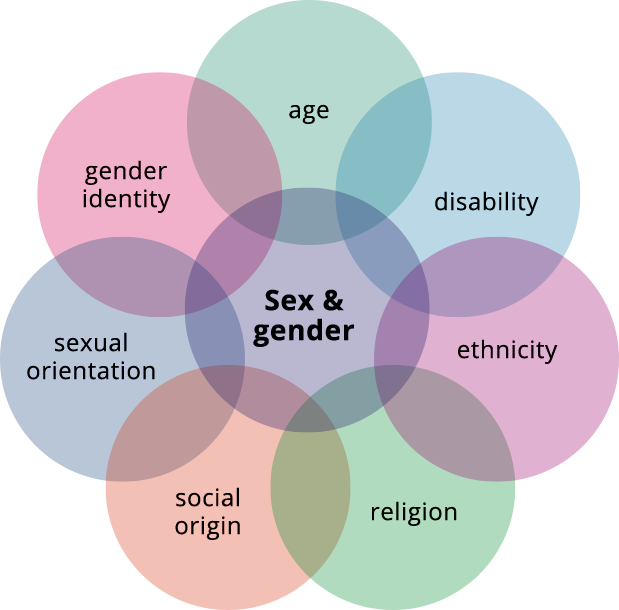

Sexism interacts with racism, classism, heterosexism, and other oppressions to shape the experience of individuals. This is called intersectionality . Compulsory heterosexuality is the prevailing belief that heterosexuality is the only "normal" relationship between the sexes, which, in a sexist society, benefits men.

Women as Sexists

Women can be conscious or unconscious collaborators in their own oppression if they accept the basic premises of sexism: that men have more power than women because they deserve more power than women. Sexism by women against men would only be possible in a system in which the balance of social, political, cultural, and economic power was measurably in the hands of women, a situation which does not exist today.

Men May Be Oppressed by Sexism

Some feminists have argued that men should be allies in the fight against sexism because men, too, are not whole in a system of enforced male hierarchies. In a patriarchal society , men are themselves in a hierarchical relationship to each other, with more benefits to the males at the top of the power pyramid.

Others have argued that the benefit males derive from sexism—even if that benefit is not consciously experienced or sought—is more weighty than whatever negative effects those with more power may experience. Feminist Robin Morgan put it this way:

"And let's put one lie to rest for all time: the lie that men are oppressed, too, by sexism—the lie that there can be such a thing as 'men's liberation groups.' Oppression is something that one group of people commits against another group specifically because of a 'threatening' characteristic shared by the latter group—skin color or sex or age, etc."

Quotes on Sexism

Bell Hooks : "Simply put, feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression... I liked this definition because it did not imply that men were the enemy. By naming sexism as the problem it went directly to the heart of the matter. Practically, it is a definition that implies that all sexist thinking and action is the problem, whether those who perpetuate it are female or male, child, or adult. It is also broad enough to include an understanding of systemic institutionalized sexism. As a definition it is open-ended. To understand feminism it implies one has to necessarily understand sexism."

Caitlin Moran : “I have a rule for working out if the root problem of something is, in fact, sexism. And it is this: asking 'Are the boys doing it? Are the boys having to worry about this stuff? Are the boys the center of a gigantic global debate on this subject?”

Erica Jong : "Sexism kind of predisposes us to see men's work as more important than women's, and it is a problem, I guess, as writers, we have to change."

Kate Millett : "It is interesting that many women do not recognize themselves as discriminated against; no better proof could be found of the totality of their conditioning."

- Feminist Theory in Sociology

- 12 Types of Social Oppression

- Patriarchal Society According to Feminism

- Womanist: Definition and Examples

- Combahee River Collective in the 1970s

- The Core Ideas and Beliefs of Feminism

- What Is Radical Feminism?

- What Is Compulsory Heterosexuality?

- Socialist Feminism vs. Other Types of Feminism

- Cultural Feminism

- The Women's Liberation Movement

- Socialist Feminism Definition and Comparisons

- 10 Important Feminist Beliefs

- Top 20 Influential Modern Feminist Theorists

- Oppression and Women's History

- Definition of Intersectionality

Sexism at work: how can we stop it?

What is sexism.

Sexism is linked to beliefs around the fundamental nature of women and men and the roles they should play in society. Sexist assumptions about women and men, which manifest themselves as gender stereotypes , can rank one gender as superior to another. Such hierarchical thinking can be conscious and hostile, or it can be unconscious, manifesting itself as unconscious bias . Sexism can touch everyone, but women are particularly affected.

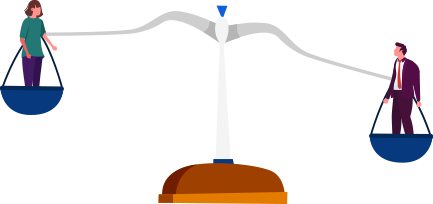

Despite legal frameworks set up across the EU to prevent discrimination and promote equality, women are still under-represented in decision-making roles, left out of certain sectors of the economy, primarily responsible for unpaid care work, paid less than men and disproportionately subject to gender-based violence [1] . Sexist attitudes, practices and behaviour contribute to these inequalities.

Within the European institutions there is no specific definition of sexism. Sexist behaviour is partly covered under Article 12a of the Staff Regulations on psychological and sexual harassment, where sexual harassment is defined as:

… conduct relating to sex which is unwanted by the person to whom it is directed and which has the purpose or effect of offending that person or creating an intimidating, hostile, offensive or disturbing environment [2] .

Sexist practices are prohibited under Article 1(d) of the Staff Regulations, which prohibits discrimination based on sex (among other forms of discrimination), as well as under Article 21 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU.

However, while some sexist behaviour may breach these anti-harassment and anti-discrimination rules, some does not reach that threshold . Additionally, the European Court of Auditors has found that while the ethical frameworks of the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission are largely adequate and staff rate their own ethical knowledge highly, less than a quarter believe their colleagues would not hesitate to report unethical behaviour [3] .

Definition: sexism

Sexism is linked to power in that those with power are typically treated with favour and those without power are typically discriminated against. Sexism is also related to stereotypes since discriminatory actions or attitudes are frequently based on false beliefs or generalisations about gender, and on considering gender as relevant where it is not.

Source: EIGE [4]

[1] Directive 2006/54/EC on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation outlines provisions Member States are obligated to take to stop sexual harassment in the workplace, as well as direct and indirect discrimination

[2] Regulation No 31 (EEC), 11 (EAEC), laying down the Staff Regulations of Officials and the Conditions of Employment of Other Servants of the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community ( https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A01962R0031-20140501 ).

[3] European Court of Auditors, Special Report – The ethical frameworks of the audited EU institutions: scope for improvement, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2019 ( https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/SR19_13/SR_ethical_frameworks_EN.pdf ).

[4] https://eige.europa.eu/thesaurus/terms/1367

The Effects of Sexism on American Women: The Role of Norms vs. Discrimination

Based on bfi working paper no. 2018-56, “the effects of sexism on american women: the role of norms vs. discrimination,” by kerwin kofi charles, professor, uchicago’s harris school of public policy; jonathan guryan, professor, northwestern university; and jessica pan, associate professor, national university singapore.

- Sexism experienced during formative years stays with girls into adulthood

- These background norms can influence choices that women make and affect their life outcomes

- In addition, women face different levels of sexism and discrimination in the states where they live as adults

- Sexism varies across states and can have a significant impact on a woman’s wages and labor market participation, and can also influence her marriage and fertility rates

What type of life experiences will these women have in terms of the work they do and the wages they earn? Will they get married and, if so, how young? If they have children, when will they start to raise a family? How many children will they have? According to the authors of the new BFI working paper, “The Effects of Sexism on American Women: The Role of Norms vs. Discrimination,” the answers to those questions depend crucially on where women are born and where they choose to live their adult lives.

Kerwin Kofi Charles, professor at the Harris School of Public Policy, and his colleagues employ a novel approach that examines how prevailing sexist beliefs shape life outcomes for women. Essentially, they find that sexism affects women through two channels: one is their own preferences that are shaped by where they grow up, and the other is the sexism they experience in the place they choose to live as adults.

On average, not all states are average The average American woman’s socioeconomic outcomes have improved dramatically over the past 50 years. Her wages and probability of employment, relative to the average man’s, have risen steadily over that time. She is also marrying later and bearing children later, as well as having fewer total children. However, these are national averages and these phenomena do not hold in all states across America. Indeed, the gap between men and women that existed in a particular state 50 years ago is largely the same size today. In other words, if a state exhibited less gender discrimination 50 years ago, it retains that narrower gap today; a state that exhibited more discrimination in 1970 has a similarly wide gap today. Much research over the years has focused on broad national trends when measuring sexism and its effect on women’s lives. A primary contribution of this paper is that it documents cross-state differences in women’s outcomes and incorporates non-market factors, like cultural norms. The focus of the authors’ analysis are the four outcomes described above: wages, employment, marriage, and fertility. Of the many forms sexism might take, the authors focus on negative or stereotypical beliefs about whether women should enter the workplace or remain at home. Specifically, sexism prevails in a market when residents believe that:

• women’s capacities are inferior to men;

• families are hurt when women work;

• and men and women should adhere to strict roles in society.

These cultural norms are not only forces that occur to women from external sources, but they are forces that also exist within women, and are strongly affected by where a woman is raised. For example, a girl may grow up within a culture that prizes stay-at-home mothers over working moms, as well as early marriages and large families. These are what the authors describe as background norms, and they are able to estimate the influence of these background norms throughout adulthood by comparing women who were born in one place and moved to different places, and those who were born in different places and moved to the same place. Once a woman reaches adulthood and chooses a place to live, she is then influenced by discrimination in the labor market and by what the authors term residential sexism, or those current norms that they experience in their new hometown. On the question of who engages in sexist behavior, men and/ or women, the authors are clear: men are the purveyors of discrimination in the market (whether women are hired for or promoted to certain jobs), and women determine norms (or residential sexism) that influence such outcomes as marriage and fertility.

The authors conduct a number of rigorous tests based on a broad array of data to reach their conclusions about women’s wages, their labor force participation relative to men, and the ages at which women aged 20-40 married and had their first child. For example, their information on sexism comes from the General Social Survey (GSS), which is a nationally representative survey that asks respondents various questions, among others, about their attitudes or beliefs about women’s place in society.

Sexism affects women through two channels: one is their own preferences that are shaped by where they grow up, and the other is the sexism they experience in the place they choose to live as adults.

The authors reveal how prevailing sexist beliefs about women’s abilities and appropriate roles affect US women’s socioeconomic outcomes. Studying adults who live in one state but who were born in another, they show that sexism in a woman’s state of birth and in her current state of residence both lower her wages and likelihood of labor force participation, and lead her to marry and bear her first child sooner. The sexism a woman experiences where she was raised, or background sexism, affects a woman’s outcomes even after she is an adult living in another place through the influence of norms that she internalized during her formative years. Further, the sexism present where a woman lives (residential sexism) affects her non-labor market outcomes through the influence of prevailing sexist beliefs of other women where she lives. By contrast, residential sexism’s effects on her labor market outcomes seem to operate chiefly through the mechanism of market discrimination by sexist men. Finally, and importantly, the authors find sound evidence that prejudice-based discrimination, undergirded by prevailing sexist beliefs that vary across space, may be an important driver of women’s outcomes in the US.

CLOSING TAKEAWAY By studying adults who were born in one place but live in another, the authors reveal the effects of sexism on women’s outcomes in the market through discrimination (wages and jobs), as well as in non-market settings through cultural norms (marriage and fertility).

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of sexism

Examples of sexism in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'sexism.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

sex entry 1 + -ism (as in racism )

1963, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Dictionary Entries Near sexism

sex-intergrade

Cite this Entry

“Sexism.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sexism. Accessed 27 May. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of sexism, more from merriam-webster on sexism.

Nglish: Translation of sexism for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of sexism for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about sexism

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - may 24, flower etymologies for your spring garden, 9 superb owl words, 'gaslighting,' 'woke,' 'democracy,' and other top lookups, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, games & quizzes.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 Feminism and Sexism

Learning objectives.

- Define feminism, sexism, and patriarchy.

- Discuss evidence for a decline in sexism.

- Understand some correlates of feminism.

Recall that more than one-third of the public (as measured in the General Social Survey) agrees with the statement, “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” Do you agree or disagree with this statement? If you are like the majority of college students, you disagree.

Today a lot of women, and some men, will say, “I’m not a feminist, but…,” and then go on to add that they hold certain beliefs about women’s equality and traditional gender roles that actually fall into a feminist framework. Their reluctance to self-identify as feminists underscores the negative image that feminists and feminism hold but also suggests that the actual meaning of feminism may be unclear.

Feminism and sexism are generally two sides of the same coin. Feminism refers to the belief that women and men should have equal opportunities in economic, political, and social life, while sexism refers to a belief in traditional gender role stereotypes and in the inherent inequality between men and women. Sexism thus parallels the concept of racial and ethnic prejudice discussed in Chapter 7 “Deviance, Crime, and Social Control” . Both women and people of color are said, for biological and/or cultural reasons, to lack certain qualities for success in today’s world.

Feminism as a social movement began in the United States during the abolitionist period before the Civil War. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott were outspoken abolitionists who made connections between slavery and the oppression of women.

The US Library of Congress – public domain; The US Library of Congress – public domain.

In the United States, feminism as a social movement began during the abolitionist period preceding the Civil War, as such women as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, both active abolitionists, began to see similarities between slavery and the oppression of women. This new women’s movement focused on many issues but especially on the right to vote. As it quickly grew, critics charged that it would ruin the family and wreak havoc on society in other ways. They added that women were not smart enough to vote and should just concentrate on being good wives and mothers (Behling, 2001).

One of the most dramatic events in the women’s suffrage movement occurred in 1872, when Susan B. Anthony was arrested because she voted. At her trial a year later in Canandaigua, New York, the judge refused to let her say anything in her defense and ordered the jury to convict her. Anthony’s statement at sentencing won wide acclaim and ended with words that ring to this day: “I shall earnestly and persistently continue to urge all women to the practical recognition of the old revolutionary maxim, ‘Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God’” (Barry, 1988).

After women won the right to vote in 1920, the women’s movement became less active but began anew in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as women active in the Southern civil rights movement turned their attention to women’s rights, and it is still active today. To a profound degree, it has changed public thinking and social and economic institutions, but, as we will see coming up, much gender inequality remains. Because the women’s movement challenged strongly held traditional views about gender, it has prompted the same kind of controversy that its 19th-century predecessor did. Feminists quickly acquired a bra-burning image, even though there is no documented instance of a bra being burned in a public protest, and the movement led to a backlash as conservative elements echoed the concerns heard a century earlier (Faludi, 1991).

Several varieties of feminism exist. Although they all share the basic idea that women and men should be equal in their opportunities in all spheres of life, they differ in other ways (Lindsey, 2011). Liberal feminism believes that the equality of women can be achieved within our existing society by passing laws and reforming social, economic, and political institutions. In contrast, socialist feminism blames capitalism for women’s inequality and says that true gender equality can result only if fundamental changes in social institutions, and even a socialist revolution, are achieved. Radical feminism , on the other hand, says that patriarchy (male domination) lies at the root of women’s oppression and that women are oppressed even in noncapitalist societies. Patriarchy itself must be abolished, they say, if women are to become equal to men. Finally, an emerging multicultural feminism emphasizes that women of color are oppressed not only because of their gender but also because of their race and class (Andersen & Collins, 2010). They thus face a triple burden that goes beyond their gender. By focusing their attention on women of color in the United States and other nations, multicultural feminists remind us that the lives of these women differ in many ways from those of the middle-class women who historically have led U.S. feminist movements.

The Growth of Feminism and the Decline of Sexism

What evidence is there for the impact of the women’s movement on public thinking? The General Social Survey, the Gallup Poll, and other national surveys show that the public has moved away from traditional views of gender toward more modern ones. Another way of saying this is that the public has moved toward feminism.

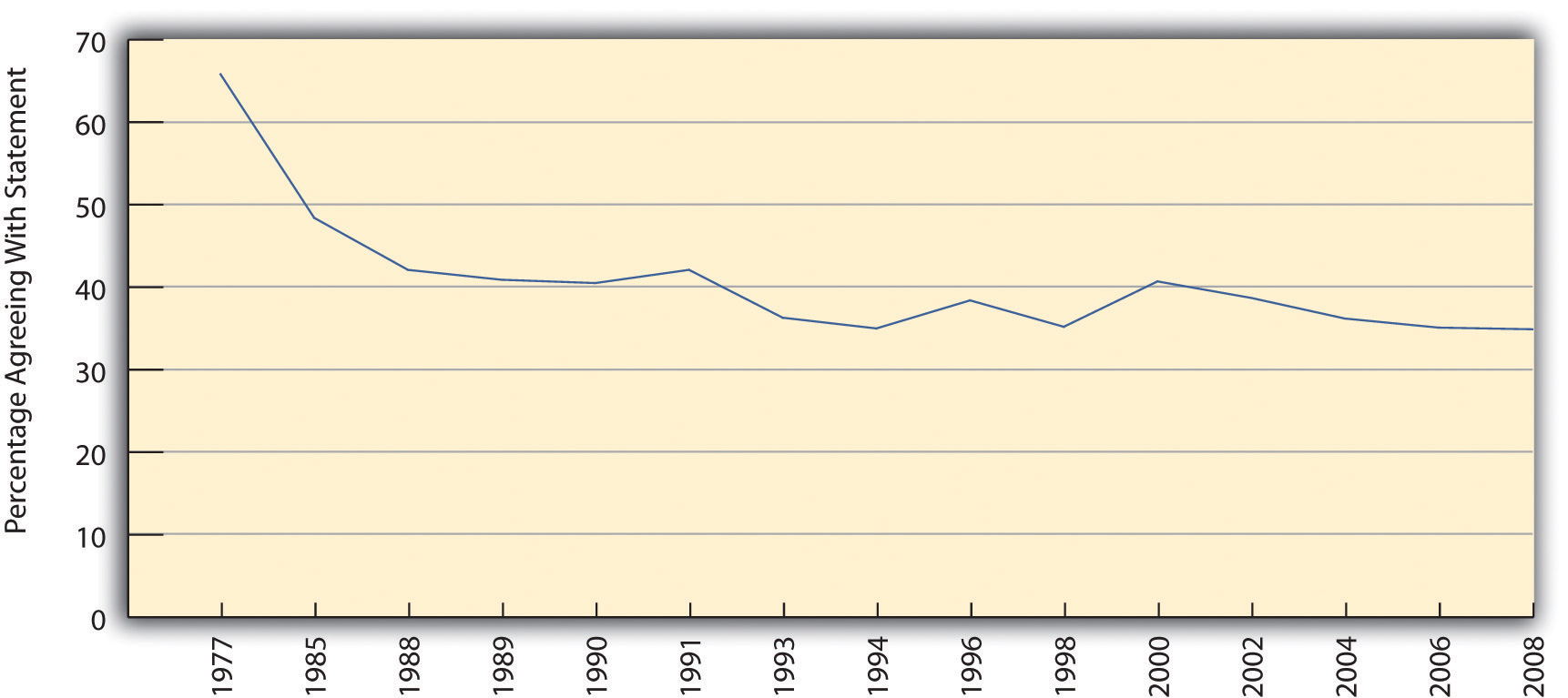

To illustrate this, let’s return to the General Social Survey statement that it is much better for the man to achieve outside the home and for the woman to take care of home and family. Figure 11.4 “Change in Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family, 1977–2008” shows that agreement with this statement dropped sharply during the 1970s and 1980s before leveling off afterward to slightly more than one-third of the public.

Figure 11.4 Change in Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family, 1977–2008

Percentage agreeing that “it is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.”

Source: Data from General Social Survey.

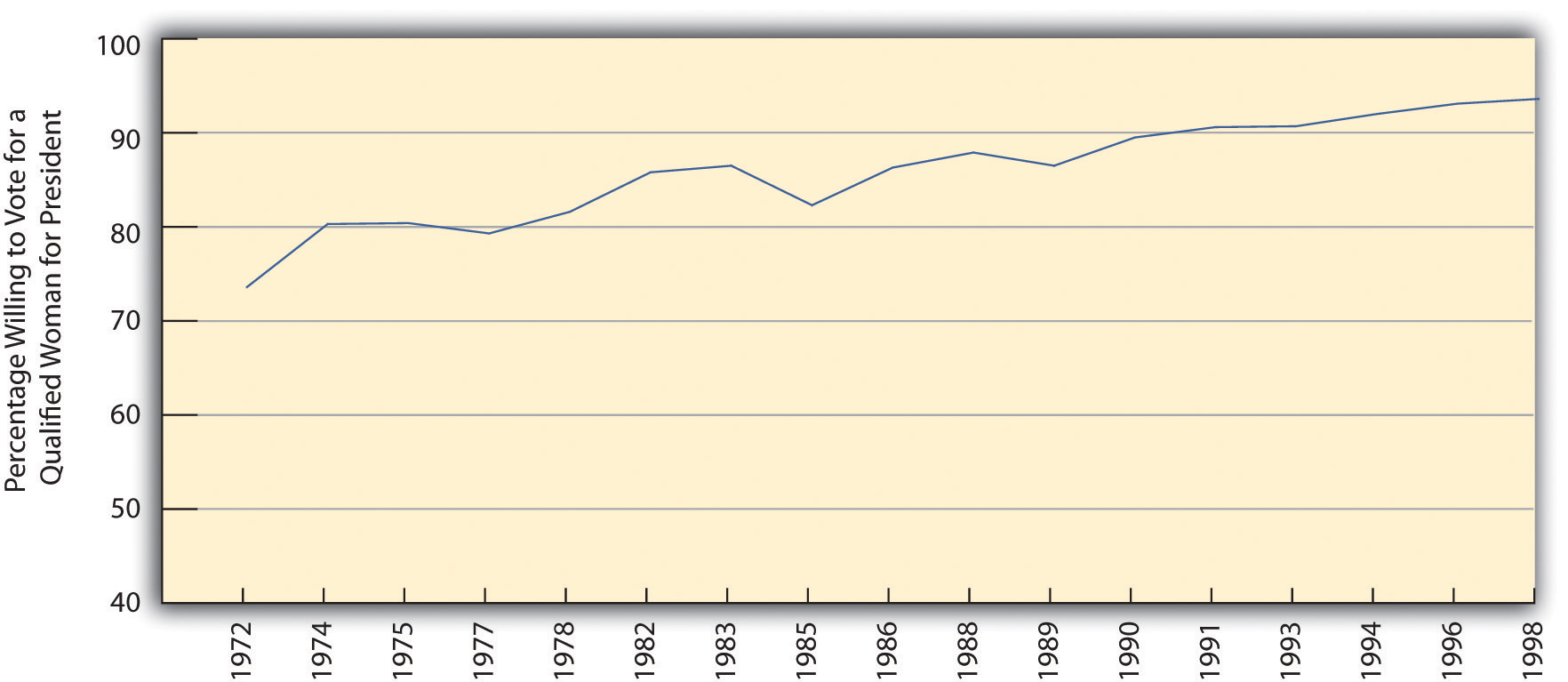

Another General Social Survey question over the years has asked whether respondents would be willing to vote for a qualified woman for president of the United States. As Figure 11.5 “Change in Willingness to Vote for a Qualified Woman for President” illustrates, this percentage rose from 74% in the early 1970s to a high of 94.1% in 2008. Although we have not yet had a woman president, despite Hillary Rodham Clinton’s historic presidential primary campaign in 2007 and 2008 and Sarah Palin’s presence on the Republican ticket in 2008, the survey evidence indicates the public is willing to vote for one. As demonstrated by the responses to the survey questions on women’s home roles and on a woman president, traditional gender views have indeed declined.

Figure 11.5 Change in Willingness to Vote for a Qualified Woman for President

Correlates of Feminism

Because of the feminist movement’s importance, scholars have investigated why some people are more likely than others to support feminist beliefs. Their research uncovers several correlates of feminism (Dauphinais, Barkan, & Cohn, 1992). We have already seen one of these when we noted that religiosity is associated with support for traditional gender roles. To turn that around, lower levels of religiosity are associated with feminist beliefs and are thus a correlate of feminism.

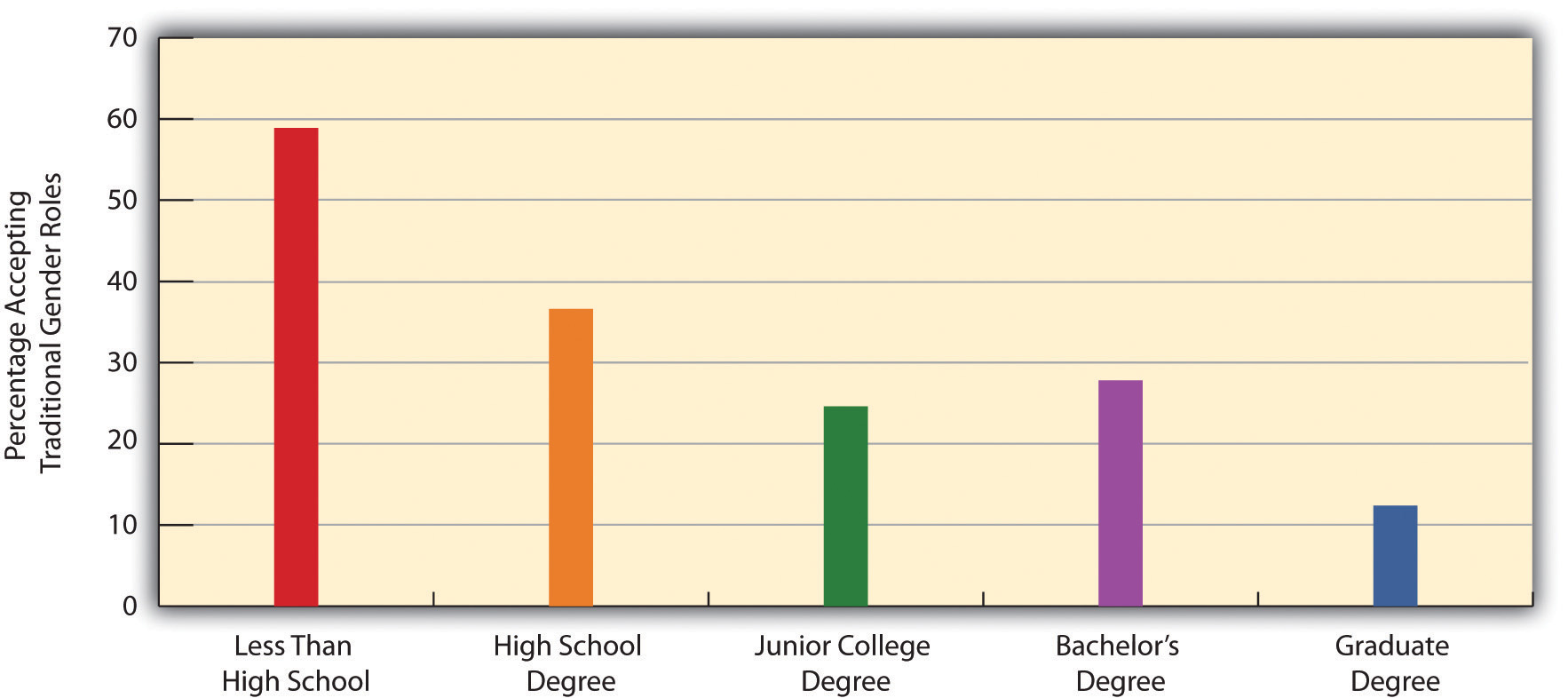

Several other such correlates exist. One of the strongest is education: the lower the education, the lower the support for feminist beliefs. Figure 11.6 “Education and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family” shows the strength of this correlation by using our familiar General Social Survey statement that men should achieve outside the home and women should take care of home and family. People without a high school degree are almost 5 times as likely as those with a graduate degree to agree with this statement.

Figure 11.6 Education and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2008.

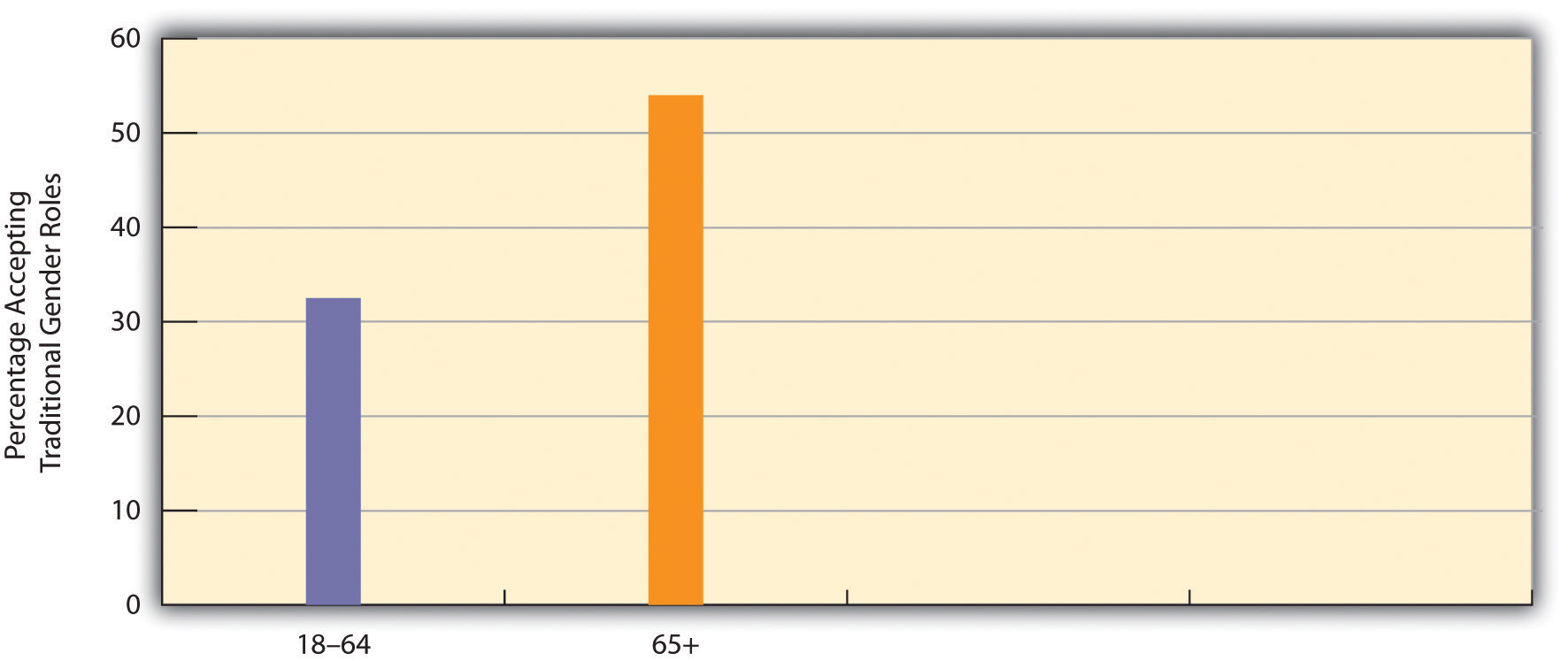

Age is another correlate, as older people are more likely than younger people to believe in traditional gender roles. Again using our familiar statement about traditional gender roles, we see an example of this relationship in Figure 11.7 “Age and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family” , which shows that older people are more likely than younger people to accept traditional gender roles as measured by this statement.

Figure 11.7 Age and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family

Key Takeaways

- Feminism refers to the belief that women and men should have equal opportunities in economic, political, and social life, while sexism refers to a belief in traditional gender role stereotypes and in the inherent inequality between men and women.

- Sexist beliefs have declined in the United States since the early 1970s.

- Several correlates of feminist beliefs exist. In particular, people with higher levels of education are more likely to hold beliefs consistent with feminism.

For Your Review

- Do you consider yourself a feminist? Why or why not?

- Think about one of your parents or of another adult much older than you. Does this person hold more traditional views about gender than you do? Explain your answer.

Andersen, M. L., & Collins, P. H. (Eds.). (2010). Race, class, and gender: An anthology (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Barry, K. L. (1988). Susan B. Anthony: Biography of a singular feminist . New York, NY: New York University Press.

Behling, L. L. (2001). The masculine woman in America, 1890–1935 . Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Dauphinais, P. D., Barkan, S. E., & Cohn, S. F. (1992). Predictors of rank-and-file feminist activism: Evidence from the 1983 General Social Survey. Social Problems, 39 , 332–344.

Faludi, S. (1991). Backlash: The undeclared war against American women . New York, NY: Crown.

Lindsey, L. L. (2011). Gender roles: A sociological perspective (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Share full article

Advertisement

This Is How Everyday Sexism Could Stop You From Getting That Promotion

By Jessica Nordell and Yaryna Serkez Oct. 14, 2021

By Jessica Nordell Graphics by Yaryna Serkez

Jessica Nordell is a science and culture journalist. Yaryna Serkez is a writer and a graphics editor for Opinion.

When the computer scientist and mathematician Lenore Blum announced her resignation from Carnegie Mellon University in 2018, the community was jolted. A distinguished professor, she’d helped found the Association for Women in Mathematics, and made seminal contributions to the field. But she said she found herself steadily marginalized from a center she’d help create — blocked from important decisions, dismissed and ignored. She explained at the time : “Subtle biases and microaggressions pile up, few of which on their own rise to the level of ‘let’s take action,’ but are insidious nonetheless.”

It’s an experience many women can relate to. But how much does everyday sexism at work matter? Most would agree that outright discrimination when it comes to hiring and advancement is a bad thing, but what about the small indignities that women experience day after day? The expectation that they be unfailingly helpful ; the golf rounds and networking opportunities they’re not invited to ; the siphoning off of credit for their work by others; unfair performance reviews that penalize them for the same behavior that’s applauded in men; the “ manterrupting ”?

When I was researching my book “The End of Bias: A Beginning” I wanted to understand the collective impact of these less visible forms of bias, but data were hard to come by. Bias doesn’t happen once or twice; it happens day after day, week after week. To explore the aggregate impact of routine gender bias over time, I teamed up with Kenny Joseph, a computer science professor at the University at Buffalo, and a graduate student there, Yuhao Du, to create a computer simulation of a workplace. We call our simulated workplace “NormCorp.” Here’s how it works.

NormCorp is a simple company. Employees do projects, either alone or in pairs. These succeed or fail, which affects a score we call “promotability.” Twice a year, employees go through performance reviews, and the top scorers at each level are promoted to the next level.

NormCorp employees are affected by the kinds of gender bias that are endemic in the workplace. Women’s successful solo projects are valued slightly less than men’s , and their successful joint projects with men accrue them less credit . They are also penalized slightly more when they fail . Occasional “stretch” projects have outsize rewards, but as in the real world, women’s potential is underrecognized compared with men’s, so they must have a greater record of past successes to be assigned these projects. A fraction of women point out the unfairness and are then penalized for the perception that they are “self-promoting.” And as the proportion of women decreases, those that are left face more stereotyping .

We simulated 10 years of promotion cycles happening at NormCorp based on these rules, and here is how women’s representation changed over time.

Simulation of Normcorp promotions over 10 years, with female performance undervalued by 3 percent

Simulation results over time

These biases have all been demonstrated across various professional fields. One working paper study of over 500,000 physician referrals showed that women surgeons receive fewer referrals after successful outcomes than male surgeons. Women economists are less likely to receive tenure the more they co-author papers with men. An analysis at a large company found that women’s, as well as minority men’s, performance was effectively “discounted” compared with that of white men.

And women are penalized for straying from “feminine” personality traits. An analysis of real-world workplace performance evaluations found that more than three-quarters of women’s critical evaluations contained negative comments about their personalities, compared with 2 percent of men’s. If a woman whose contributions are overlooked speaks up, she may be labeled a self-promoter, and consequently face further obstacles to success . She may also become less motivated and committed to the organization . The American Bar Association found that 70 percent of women lawyers of color considered leaving or had left the legal profession entirely, citing being undervalued at work and facing barriers to advancement.

Our model does not take into account women, such as Lenore Blum, who quit their jobs after experiencing an unmanageable amount of bias. But it visualizes how these penalties add up over time for women who stay, so that by the time you reach more senior levels of management, there are fewer women left to promote. These factors not only prevent women from reaching the top ranks in their company but for those who do, it also makes the career path longer and more demanding.

Small change, big difference

Even a tiny increase in the amount of gender bias could lead to dramatic underrepresentation of women in leadership roles over time..

Women’s performance is valued 3 percent less

Women’s performance is valued 5 percent less

Half as many women at level 7 and

only 2 percent of women at C-suite.

Half as many women at level 7 and only 2 percent of women at C-suite.

Women’s performance is valued 3% less

Women’s performance is valued 5% less

When we dig into the trajectory of individual people in our simulation, stories begin to emerge. With just 3 percent bias, one employee — let’s call her Jenelle — starts in an entry-level position, and makes it to the executive level, but it takes her 17 performance review cycles (eight and a half years) to get there, and she needs 208 successful projects to make it. “William” starts at the same level but he gets to executive level much faster — after only eight performance reviews and half Jenelle’s successes at the time she becomes an executive.

Our model shows how large organizational disparities can emerge from many small, even unintentional biases happening frequently over a long period of time. Laws are often designed to address large events that happen infrequently and can be easily attributed to a single actor—for example, overt sexual harassment by a manager — or “pattern and practice” problems, such as discriminatory policies. But women’s progress is hindered even without one egregious incident, or an official policy that is discriminatory.

Women’s path to success might be longer and more demanding

Career paths for employees that reached level 7 by the end of the simulation..

successful projects

“William”

started at the entry-level and reached level 7 in 4 years.

It took “Jenelle”

8.5 years to get

to the same level.

Entry level

1 year of promotions

started at the entry-

level and reached level 7 in 4 years.

8.5 years to get to the same level.

It took “Jenelle” 8.5 years to get to the same level.

Gender bias takes on different dimensions depending on other intersecting aspects of a person’s identity, such as race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability and more. Another American Bar Association study found that white women and men of color face similar hurdles to being seen as competent, but women of color face more than either group.

Backlash, too, plays out differently for women of different racial groups, points out Erika Hall, an Emory University management professor. A survey of hundreds of women scientists she helped conduct found that Asian American women reported the highest amount of backlash for self-promotion and assertive behavior. An experimental study by the social psychologist Robert Livingston and colleagues, meanwhile, found that white women are more penalized for demonstrating dominant behavior than Black women. Our model does not account for the important variations in bias that women of different races experience.

So what’s to be done? Diversity trainings are common in companies, educational institutions and health care settings, but these may not have much effect when it comes to employees’ career advancement. The sociologists Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev found that after mandatory diversity trainings, the likelihood that women and men of color became managers either stayed the same or decreased , possibly because of backlash. Some anti-bias trainings have been shown to change behavior, but any approach needs to be evaluated, as psychologist Betsy Levy Paluck has said, “on the level of rigorous testing of medical interventions.”

We also explored a paradox. Research shows that in many fields, a greater proportion of men correlates with more bias against women . At the same time, in fields or organizations where women make up the majority, men can still experience a “glass escalator,” being fast-tracked to senior leadership roles. School superintendents, who work in the women-dominated field of education but are more likely to be men, are one example. To make sense of this, we conceptualized bias at work as a combination of both organizational biases that can be influenced by organizational makeup and larger societal biases.

What we found was that if societal biases are strong compared with those in the organization, a powerful but brief intervention may have only a short-term impact. In our simulation, we tested this by introducing quotas — requiring that the majority of promotions go to women — in the context of low, moderate, or no societal bias. We made the quotas time-limited, as real world efforts to combat bias often take the form of short-term interventions.

Our quotas changed the number of women at upper levels of the corporate hierarchy in the short term, and in turn decreased the gender biases against women rising through the company ranks. But when societal biases were still a persistent force, disparities eventually returned, and the impact of the intervention was short-lived.

Quotas may not be enough

In the presence of societal biases, the effect of a short-term program of quotas disappears over time..

Societal bias has moderate effect

100% of executives

Quotas are introduced. 70% of all promotions go to women.

Majority of executives are men

YEARS OF PROMOTIONS

Societal bias has no effect

Equal representation

representation

What works? Having managers directly mentor and sponsor women improves their chance to rise. Insisting on fair, transparent and objective criteria for promotions and assignments is essential, so that decisions are not ambiguous and subjective, and goal posts aren’t shifting and unwritten. But the effect of standardizing criteria, too, can be limited, because decision-makers can always override these decisions and choose their favored candidates.

Ultimately, I found in my research for the book, the mindset of leaders plays an enormous role. Interventions make a difference, but only if leaders commit to them. One law firm I profiled achieved 50 percent women equity partners through a series of dramatic moves, from overhauling and standardizing promotion criteria, to active sponsorship of women, to a zero-tolerance policy for biased behavior. In this case, the chief executive understood that bias was blocking the company from capturing all the available talent. Leaders who believe that the elimination of bias is essential to the functioning of the organization are more likely to take the kind of active, aggressive, and long-term steps needed to root out bias wherever it may creep into decision making.

Sexism: Gender, Class and Power Essay

Introduction.

Sexism is one of the challenges that most societies in the contemporary world have struggled to address without any meaningful progress. It refers to discriminatory or abusive behavior towards members of the opposite sex. Although anybody is vulnerable to sexism, it is majorly documented as a problem faced by women and girls. According to psychologists, the challenge of sexism is necessitated by factors such as gender roles and stereotypes across various societies (Dawson, 2018).

Over the years, various human rights groups have made an effort to create awareness about sexism and the probable dangers the victims might be exposed to if effective management strategies are not put in place. Research has established that in societies where sexism is highly rooted, victims are often vulnerable to rape and sexual harassment (Brewington, 2013). Cases of sexism against women are very common in the workplace.

Women are very vulnerable to sexual harassment in the workplace as their male colleagues and bosses often ask for sexual favors in exchange for promotions and salary reviews (Tulshyan, 2016). Women also argue that they are often overlooked in leadership positions because men are considered to have a better chance of succeeding. Sexism is a deep-rooted societal vice that ought to be eliminated in order to promote the value of humanity.

Since the turn of the century, people are more vocal with regard to the danger of sexism. Social networking sites are one of the platforms that people have used to highlight the challenges faced by victims of sexism and offer solutions to the problem. In 2012, the infamous Everyday Sexism project was launched with an aim to expose the numerous acts of sexism across the United Kingdom. The project quickly got the attention of the world as people gave shocking reactions to the degree to which the vice was rampant, especially in the streets (Brewington, 2013).

According to research, social media, as well as print and electronic media, have contributed greatly to the advancement of sexism regardless of the fact that they are also being used to fight the vice. For example, the contemporary hip-hop music industry in the United States has been accused of promoting sexism through their music videos. The genre has led to women being viewed more from a sexual angle because of the way they appear in the music videos.

These videos are aired across major television channels and readily available for consumption by the global audience through YouTube. Fashion magazines have also contributed to the growing challenge of sexism, especially towards women, because the artistic presentation of the female body is angled in a sexual manner (Brewington, 2013).

Apart from the inappropriate portrayal of human bodies by media, sexism is highly prevalent in modern society in several other ways. In the workplace, women often complain of the general assumption that men are more qualified and knowledgeable compared to women (Tulshyan, 2016). It is frustrating for women when a colleague seeks advice or clarification from a male peer when they know that they are in a better position to do the same. Women also consider the inability of an employer to allocate a certain task to them simply because they are physically demanding as an act of sexism (Dawson, 2018).

Women go to the gym and participate in various sports just as men do. Thus, it is wrong to assume they cannot meet the physical demands of a task. Psychologists argue that sexism is a relative concept with regard to the way various societies explain and comprehend it. This is evidenced in the different actions or elements that are considered as being sexist. In some societies, the fact that women are made to change their surname when they get married is considered sexism. Women feel that it is not necessary for them to give up their last name because of a process that even men undergo, yet they get to retain theirs (Brewington, 2013).

Another common form of sexism is sexist language. Studies have established that men are less vulnerable compared to women when it comes to sexual objectification when being addressed. It is important for people to use gender-sensitive language, especially in situations where both men and women are involved. For example, it is wrong to use masculine generics such as “Chairman” when referring to a female leader. Instead, one should use a gender-sensitive term such as chairperson (Lipman, 2018).

It is also an act of sexism to refer to a group of people with both men and women as “Guys” because it creates an impression that women are a category below men as human beings. It is also a common occurrence to hear men referring to adult women as girls. This often infantilizes a woman because it makes one feel like the person addressing her is giving an indication that they are not mature.

The most unfortunate thing about sexist language is the casual manner in which it has been used over the years, to the extent that it has become part of the conventional glossary. This is one of the major challenges facing the fight against sexism. Objectification of women through sexist language is rooted in the stereotypes the society develops from the way girls are raised and theories about their beauty (Evans, 2016). Over the years, women have been used to market products through various forms of advertisements. This has influenced girls to believe that they are as valuable as they look. Therefore, any woman whose beauty fails to meet societal standards tends to feel less valuable.

Sexism has robbed women of their safety, comfort, and voice. Many women who have been a victim of street harassment from men argue that such experiences act as an affirmation that their bodies are owned by the society (Brewington, 2013). Due to laxity within the society, women are made to unwillingly take street harassment as intended compliments rather than abuse. Domestic violence is a form of sexism that has taken away the voice of women.

In many societies, many cases of domestic violence against men and women end up unreported because the victims know they will not get any help with ease. It’s a human rights violation that often demeans the victim because the violator perceives the victim as being weak (Evans, 2016). Unfortunately, domestic violence is legal in places such as the United Arab Emirates, where husbands are allowed to discipline their wives as long as they do not inflict visible injuries.

South Asia is common for practicing a form of sexism called Gendercide. It involves the killing of children of a specific gender. It is close to gender-selective-abortion, where women are forced to terminate their pregnancies depending on the sex of the unborn child. In these practices, girls are targeted more than boys. The same case applies to female genital mutilation, which human rights groups consider as the gravest form of sexism (Evans, 2016).

In contemporary society, technology is widely abused to advance sexist agendas. Women always complain of suffering rape anxiety because people use phone calls and social media posts to deliver threats. No one chooses to be a victim of sexism; thus, avoiding walking in the streets unaccompanied or with people of the same gender is not enough. Cyberbullying is a strategy widely used by sexist people to harass their targets. The internet has turned the world into a global village.

Thus cultural interaction has been greatly heightened (Brewington, 2013). This effect is manifested a lot in the fashion industry, where the dres’ codes for men and women have undergone a huge transformation. Psychologists argue that dres’ codes are sexist in nature. They often limit the power and confidence of women, depending on the societal perception of a certain trend. The style of women wearing pants started in the developed countries as a way of helping women address the threat of rape. Several decades later, it has become a global trend. Some women argue that their lies in wearing dresses, but they are often forced to wear pants for safety purposes (Evans, 2016).

The concept of sexism is very broad and cannot be explained exhaustively. However, it is common knowledge that there is an urgent need to address this global challenge in order to achieve the common good. Gender equality and sensitivity is a right of every human being, thus the need to ensure that we create a more inclusive society. In order to achieve this feat, a change in attitude with regard to the way different genders perceive each other is very important. Men need to understand that they are not biologically programmed to harass women or objectify them.

Brewington, C. (2013). The sacred place of exile: Pioneering women and the need for a new women’s missionary movement . New York, NY: Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Dawson, T. (2018). Gender, class and power: An analysis of pay inequalities in the workplace . New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Evans, M. (2016). The persistence of gender inequality . New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Lipman, J. (2018). That’s what she said: What men need to know and women need to tell them about working together . New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Tulshyan, R. (2016). The diversity advantage: Fixing gender inequality in the workplace . New York, NY: Create Space Independent Publishing Platform.

- When Men Experience Sexism Article by Berlatsky

- Canadian Society: Sexism and the Persistent Woman Question

- Misogyny and Sexism in Policing

- The Restricted Status of Women in Pakistan

- Diversity Organizations and Gender Issues in the US

- Gender Discrimination in the United States

- Gender Inequality Index 2013 in the Gulf Countries

- Feminist Perspective: “The Gender Pay Gap Explained”

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, May 7). Sexism: Gender, Class and Power. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/

"Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." IvyPanda , 7 May 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Sexism: Gender, Class and Power'. 7 May.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

1. IvyPanda . "Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Sexism: Gender, Class and Power." May 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sexism-gender-class-and-power/.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Belief in sexism shift: Defining a new form of contemporary sexism and introducing the belief in sexism shift scale (BSS scale)

Miriam k. zehnter.

1 Department of Work, Economic, and Social Psychology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Francesca Manzi

2 Department of Social, Health, and Organisational Psychology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Patrick E. Shrout

3 Department of Psychology, New York University, New York, New York, United States of America

Madeline E. Heilman

Associated data.

All data, analyses, and R code are available on the Open Science Framework via https://www.doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2DGTE

The belief that the target of sexism has shifted from women to men is gaining popularity. Yet despite its potential theoretical and practical importance, the belief that men are now the primary target of sexism has not been systematically defined nor has it been reliably measured. In this paper, we define the belief in sexism shift (BSS) and introduce a scale to measure it. We contend that BSS constitutes a new form of contemporary sexism characterized by the perception that anti-male discrimination is pervasive, that it now exceeds anti-female discrimination, and that it is caused by women’s societal advancement. In four studies (N = 666), we develop and test a concise, one-dimensional, 15-item measure of BSS: the BSS scale. Our findings demonstrate that BSS is related to, yet distinct from other forms of sexism (traditional, modern, and ambivalent sexism). Moreover, our results show that the BSS scale is a stable and reliable measure of BSS across different samples, time, and participant gender. The BSS scale is also less susceptible to social desirability concerns than other sexism measures. In sum, the BSS scale can be a valuable tool to help understand a new and potentially growing type of sexism that may hinder women in unprecedented ways.

Introduction

“Man has been the dominant sex since , well , the dawn of mankind . But for the first time in human history , that is changing–and with shocking speed . ” [ 1 ].

In 2016, two former Yahoo employees filed independent lawsuits alleging that the company had discriminated against them because of their gender [ 2 ]. These were not isolated cases. Several large corporations and educational institutions (e.g., Google, Yale University) were recently confronted with similar claims of gender discrimination [ 3 , 4 ]. These allegations were surprising not because of the nature of the complaint–thousands of gender-based discrimination suits are filed each year in the US alone [ 5 ]–but because of the gender of the complainants: All of the plaintiffs were men. Notably, many of these lawsuits were filed in domains that remain heavily male-dominated.

The belief that men are now the disadvantaged gender has gained traction, sparking debates both in popular culture and academia [ 6 – 8 ]. Data indicate that men, in particular, believe that they are more likely than ever before to suffer gender-based discrimination [ 9 , 10 ]. About two thirds of men claim to have faced at least some discrimination due to their gender [ 11 ]. Even some women share these beliefs. In the United States, 9% women (and 15% men) believe that women have better job opportunities than men [ 12 ], and 5% of women (and 14% of men) think that it is now easier to be a woman than a man [ 13 ].

Taken together, these data suggest that there is an increasing number of men and women who believe that “the tables have turned”–that is, that the target of sexism has shifted from women to men, and that anti-male discrimination is now a pervasive social issue. Recent efforts have been made to begin to understand this emerging belief as well as its potential causes and consequences [ 14 – 16 ]. However, the literature to date has not yet offered a systematic definition of what this belief entails, nor have researchers provided a reliable way to measure it.

The aim of this paper is to introduce and formally define the belief in sexism shift (BSS) and to develop a scale to measure it: the BSS scale. We first provide a definition of BSS and place it in the broader context of contemporary anti-female sexism. We then present research on the development and validation of the BSS scale, a 15-item self-report measure reflecting the perceptions of anti-male discrimination that comprise BSS. Finally, we discuss how the BSS scale may help advance our understanding of sexism, in general, and enable future research on BSS, in particular.

Defining belief in sexism shift

The belief in sexism shift centers around the victimization of men. It is characterized by the belief that men have become the primary victims of sexism, that male victimization is pervasive, and that this new form of discrimination is the result of women’s societal advancement.

As its name suggests, those who endorse BSS perceive a shift or transition from anti-female sexism to anti-male sexism. This shift is thought to have occurred recently and to have increased to a point where men now suffer more discrimination than women [ 9 , 10 ]. Men are not merely seen as additional victims of rigid gender norms alongside women; but rather, as the primary target of gender discrimination.

Importantly, male victimization is not limited to contexts where men may actually be discriminated against, such as female-dominated professions or traditionally feminine roles [ 17 ]. Rather, individuals who endorse BSS perceive anti-male discrimination to be ubiquitous, manifesting in multiple settings (e.g., the workplace, politics), through multiple perpetrators (e.g., the media, feminists), and in multiple ways (e.g., political correctness, devaluation of masculinity; [ 18 – 20 ]).

In addition, BSS entails that it is women’s societal advancement that has, to a great extent, led to anti-male discrimination. Instead of viewing women’s progress as a step towards greater gender equality for both women and men, those endorsing BSS assume that women’s gains entail losses for men [ 9 , 14 , 21 ]. This zero-sum perspective on gender discrimination is important: it differentiates individuals who endorse BSS from those who perceive that all genders may suffer from some form of discrimination [ 22 – 24 ].

Belief in sexism shift as a contemporary form of anti-female sexism

On the surface, the focus of BSS is on men and not on women. Thus, the idea that BSS constitutes a new form of anti-female sexism may seem counterintuitive. We argue, however, that BSS is consistent with both the definition and function of anti-female sexism.

Sexism has been defined as discriminatory and prejudicial attitudes, beliefs and practices directed against a person based on their sex and/or gender [ 25 ]. In the case of BSS, negative attitudes towards women are concealed through a narrative of male victimization where men’s disadvantages are the product of a system that has relentlessly favored women. By implying that women’s progress has been attained through favoritism, BSS subtly discounts women’s abilities and downplays their merits in their own advancement.

Further, like other forms of anti-female sexism, the function of BSS is to sustain a gender hierarchy that places men over women [ 26 ]. However, BSS fulfills this function in new and specific ways. Namely, BSS diverts attention from ongoing discrimination against women by redirecting the focus, placing men as the targets of an ostensibly anti-male system. Not only does BSS obscure anti-female discrimination, but it also goes a step further, positing that women now have an unjust advantage over men. This implies that any measure to further advance women is unnecessary and effectively hurts men.

In sum, BSS serves to uphold men’s higher social status by providing an unprecedented rationale for prioritizing men’s rights over women’s rights. From the perspective of those who endorse BSS, efforts to attain gender equality should effectively move away from women’s issues to instead focus solely on the protection of men’s rights.

Differences between belief in sexism shift and other forms sexism

BSS, although a manifestation of sexism against women, differs from the most well-studied forms of anti-female sexism in critical ways.

Traditional sexism

Traditional or “old-fashioned” sexism focuses on the social roles that women and men should fulfill [ 27 , 28 ]: While intellectual and leadership roles are ascribed to men, housekeeping and caregiving roles are ascribed to women. Thus, traditional sexism serves to justify the unequal treatment of women and men by overtly upholding conventional gender roles [ 27 , 28 ]. Unlike traditional sexism, upholding BSS does not require a traditional view of gender. Instead, the outward focus of BSS is on gender equality–albeit to advance men. In this way, BSS provides a more modern and socially acceptable narrative to justify placing men over women and is thus a much more subtle form of sexism than traditional sexism.

Ambivalent sexism

Ambivalent sexism assigns both negative (hostile sexism) and positive (benevolent sexism) attributes to women. While blatant hostility is directed towards non-traditional and feminist women, traditional women are seen as needing and worthy of protection [ 29 ]. BSS does not explicitly address any particular subgroup of women–all women are seen as benefitting from anti-male discrimination. Like hostile sexists, those who endorse BSS hold negative views of women. However, BSS is much less blatant: it conceals negative attitudes towards women behind a narrative of male victimhood. Thus, unlike hostile sexism, BSS may not be readily recognized as anti-female, making it a more insidious form of contemporary sexism. In addition, although both benevolent sexism and BSS are subtle forms of sexism, they each obscure anti-female attitudes in markedly different ways. While the former uses paternalism and praise, the latter achieves this goal by shifting the focus towards the victimization of men.

Modern sexism

Rather than focusing on women’s roles or attributes, modern sexism centers around the current state of gender discrimination. Indeed, modern sexism is defined by the denial of structural discrimination against women [ 28 ]. Although modern sexists do not explicitly belittle women, denying anti-female discrimination allows them to subtly trace back the causes for women’s social stagnation to women’s own shortcomings, rendering further measures for the advancement of women obsolete. BSS, also, focuses on the state of gender discrimination. But unlike modern sexists, those endorsing BSS posit that gender discrimination is an ongoing societal issue, albeit with different victims. Moreover, if the current victims of discrimination are now men, measures to ensure women’s advancement are not only seen as obsolete, but also as a barrier to attaining true gender equality. Thus, those who uphold BSS see measures to promote men (over women) as both legitimate and necessary.

Overview of the present research

The goal of this research is to provide a reliable self-report measure of the tendency to endorse the belief in sexism shift and to build a case for its validity. This is a first and essential step for future research on BSS, its psychological underpinnings, and its downstream consequences. In the following sections, we present four studies designed to develop and test a concise, one-dimensional, 15-item measure–the BSS scale. In a pilot study, we use principal component analysis (PCA) to assess the plausibility of a one-dimensional structure of BSS in an initial pool of 75 items. We also begin to reduce the item pool. In Study 1, we use exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to identify the items that are related to the core construct. After selecting 15 items that balance conceptual relevance and psychometric credentials, we use confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for a preliminary examination of the fit of a one-dimensional psychometric model. In Study 2, we use CFA to assess the factor structure of the BSS scale with a new sample. Then, we assess the BSS scale’s convergent and discriminant validity. In addition, we examine the test-retest reliability of the BSS scale over a time span of two weeks. Finally, in Study 3, we perform analyses of measurement invariance (AMI) to assess whether the BSS items have the same psychometric structure among women and men. An overview of the four studies’ aims and statistical analyses is provided in Table 1 .

General method

Before presenting our results, we will identify methodological aspects that were consistent across all studies.

Research participants

Six hundred and sixty-six adults were involved in the studies reported here. Of these participants, 288 (43%) identified as women, 376 (56%) identified as men, and two (<1%) identified as non-binary. All participants were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) and paid between 0.75 and 2.00 US Dollars. Given the language and wording of some of the scale items (e.g., “In the US, discrimination against men is on the rise”), participants were also required to reside in the United States and to be at least 18 years of age.

Identification of careless responses

Although MTurk generally produces high-quality data [ 30 ], we took additional steps to identify careless responses. Following recommendations [ 31 ] we included one instructed-response item per 50 to 100 items (e.g., “Reading the items carefully is critical, if you are paying attention please choose ‘ I strongly agree’ ”). We also computed a psychometric antonym index by correlating item pairs with opposite content (e.g., “Feminism is about favoring women over men” and “Feminism does not discriminate against men” ) . Since such items are expected to correlate negatively, positive indices indicate careless response [ 31 ]. In addition, we screened the responses of participants who completed the questionnaire suspiciously fast, that is, those with an average response time of under two seconds per item [ 32 ]. Individuals were excluded from data analysis either for incorrect response(s) to the instructed response item(s), or for rushed response times in combination with a psychometric antonym index above .30.

Table 2 provides a summary of the sample characteristics, including socio-demographic information, by study.

1 Note. The retest response rate was 65 percent.

2 Note. This sample was obtained by collapsing responses from the Pilot Study, Study 1, and Study 2.

3 Note. Two additional participants indicating non-binary gender were excluded from analysis of measurement invariance.

The research presented here was approved by New York University’s Internal Review Board (NYU IRB). All studies were conducted on MTurk and introduced as a study on “people’s opinions about current issues”. Upon providing informed consent, participants were asked to complete one or more questionnaires and to provide basic demographic information (gender, race/ethnicity, and age). The order of the items and questionnaires (when applicable) was randomized in every study. After completing the study, participants were fully debriefed.

Item generation

We used various approaches to develop items for the BSS scale. First, we invited a group of experts on gender and intergroup relations to brainstorm items that could reflect potential manifestations of BSS. Our second approach involved the examination of relevant websites (e.g., avoiceformen.com), online forums (e.g., reddit), and recent media articles and debates [ 33 , 34 ] for “real-world” examples of BSS. In a third and final approach, we turned to the literature on sexism and related constructs. Several items were inspired by recent work on current perceptions of gender discrimination [ 10 ]. We also rephrased items from previous sexism scales, such as the Modern Sexism Scale [ 28 ] and the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory [ 29 ], to reflect BSS. For example, the modern sexism item “Women often miss out on good jobs due to sexual discrimination” was adapted to read “Men often miss out on good jobs due to affirmative action for women”.

This process resulted in an initial list of 75 items reflecting male victimization, the central characteristic of BSS. The items were created to describe beliefs about anti-male discrimination on a general level (e.g., “In the US, discrimination against men is on the rise”) as well as specific examples of its multiple manifestations, perpetrators, and expressions (e.g., “Nowadays, men don’t have the same chances in the job market as women”). They also included statements reflecting zero-sum beliefs about gender discrimination (e.g., “Giving women more rights often requires taking away men’s rights”). All items were worded as statements, and responses were coded using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = I strongly disagree , 7 = I strongly agree ). 16 items were reverse-coded to provide within-scale attention checks.

The goal of the pilot study was to assess the plausibility of a one-dimensional structure of BSS in the initial item pool of 75 items. We also sought to select a subset of items that were strongly related to the dominant dimension.

Participants and procedure

We analyzed the responses of one hundred and twelve participants (for detailed sample characteristics, see Table 2 ). The sample size was chosen to provide an initial check on how highly correlated the item-responses were. With this sample size, the 95% confidence bound on a sample correlation of zero was ±.19 (and narrower for positive correlations), giving us the ability to identify the items that were clearly uncorrelated with the first principle component of the item set. The structure of the selected items was verified in subsequent studies with larger sample sizes.

Data analysis

Because the sample size was relatively small, we analyzed the item correlation matrix using principal components analysis (PCA) rather than factor analysis. The pattern of eigenvalues from PCA reveals the extent to which the items reflect overlapping variance. Corresponding to the first eigenvalue is an eigenvector, which gives an approximation to factor loadings from a one-factor model. We computed the eigenvalues of the 75 by 75 item matrix and determined the number of components by examining the scree plot of the eigenvalues and using Horn’s parallel analysis [ 35 ]. Then, we performed PCA on a one-component and a two-component solution. Adhering to a theory-driven approach, we checked to see if items that are key markers of the BSS construct had high loadings on the first eigenvector. Specifically, we examined whether the items reflecting male victimization on a general level loaded highly on the first component. We then selected a subset of items that balanced conceptual relevance and psychometric credentials. Of the items that reflected male victimization on a general level, we selected the items with the highest component loadings. Then we selected items representing specific manifestations of male victimization, including different settings, perpetrators, and expressions. For each manifestation (e.g., male victimization in the media, male victimization by feminists), we again selected the items with the highest component loadings. We also selected the highest loading items illustrating zero-sum beliefs about gender discrimination. Lastly, we selected the reverse-coded items with the highest component loadings to provide within-scale attention checks. All analyses were conducted in R using the psych package [ 36 ].

The analysis of the eigenvalues and the scree plot ( Fig 1 ) supported a one-dimensional structure of the proposed latent construct (i.e., BSS), with the first eigenvalue being considerably larger than the subsequent eigenvalues. As Horn’s parallel analysis suggested that a second component might be evident, we examined a one-component and a two-component solution. However, while the first component explained 57% of variance, a second component explained merely 4.3% of additional variance. In addition, 67 items (89.3%) loaded highly on the first component (i.e., loadings > |.60|; [ 37 , 38 ]), indicating that one component was a good representation of the BSS construct. We then reduced the list of 75 items to 28 items. We selected 3 items reflecting male victimization on a general level, 22 items describing specific manifestations of anti-male discrimination, and 3 items reflecting zero-sum beliefs about gender discrimination. Six of the 28 selected items were reverse-coded. See S1 Table for the component loadings of the 75 items included in the Pilot Study.

Note: The number of components shown here was limited to 20. The real maximum number of components was 75.

In Study 1, we assessed the psychometric properties of the reduced subset of 28 items identified in the pilot study and selected a subset of 15 items that represented the BSS construct. We then examined the plausibility of a one-dimensional structure of the final set of items.

We analyzed the responses of two hundred and nineteen participants (see Table 2 for sample characteristics). To determine sample size, we conducted power analyses based on the results from the pilot study. Specifically, we selected the item with the lowest factor loading, the item with the highest factor loading, and one item with an average factor loading. We then estimated the power that each of these items had achieved in the pilot study. The selected items had high test power (>.80) despite the small sample size. We thus felt confident that a similarly sized sample (n ≥ 112) would be sufficiently well-powered. We initially recruited 120 individuals for Study 1. However, after making slight changes to the wording of one item, we recruited 120 additional participants to ensure that rewording did not change the perceived meaning of the item. Given that the means of the reworded item were not significantly different across the two samples, we decided to collapse the two samples for subsequent analyses, t (217) = -1.72, p = .09.

We used a maximum likelihood EFA to examine the psychometric properties of the 28 items selected using pilot study results. We computed the eigenvalues of the 28 by 28 item matrix and again determined the number of factors by examining the scree plot of the eigenvalues and conducting a parallel analysis. Then, we performed EFA on a one-factor and a two-factor solution. In the two-factor EFA, we used Promax to rotate the solution (an oblique rotation that allows factors to be correlated). EFA was performed in R using the fa function in the psych package [ 36 ].

Fifteen of the 28 items were selected to represent the BSS scale based on conceptual and statistical considerations. Specifically, we chose the items with the highest factor loadings within three conceptual domains, male victimization on a general level, specific manifestations of male victimization (e.g., specific contexts, perpetrators, and expressions), and zero-sum beliefs about gender discrimination. Finally, we selected the reverse-coded items with the highest factor loadings.

As a preliminary analysis of the psychometric structure of the final sets of items, we performed maximum likelihood CFA on a one-factor model. Model fit was assessed through chi-square, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR). We expected that a well-fitting model would meet most of the following criteria: RMSEA < .06, CFI > .95, TLI > .95, and SRMR < .08 [ 39 ]. CFA was performed in R using the lavaan package for latent variable analyses [ 40 ].

Consistent with the results from the pilot study, the scree plot suggested a one-dimensional solution ( Fig 2 ). Also in line with the pilot study, parallel analysis suggested that a second or third factor might be evident. To explore that possibility, we examined both the one- and two-factor EFA solutions. The one-factor solution explained 58%, and the two-factor solution explained merely 2% of additional variance. For the one-factor solution, the fit indices were, RMSR = .05, TLI = .89, RMSEA = .09, 90% CI [.08, .09], whereas for the two-factor solution they were RMSR = .04, TLI = .92, RMSEA = .08, 90% CI [.06, .08]. The LR chi square for the one-factor model was LR (350) = 867.33 and for the two-factor model it was LR (323) = 686.51. The difference between them was LR (72) = 180.82, p < .0001.

Note: The number of factors shown here was limited to 20. The real maximum number of factors was 28.

All item loadings from the one factor solution were in the expected direction, ranging in magnitude from .91 to .33, with a median loading of .79. The loadings in the Promax-rotated two-factor solution were also in the expected direction, with seventeen items loading highest on a factor reflecting male victimization on a general level and ten items loading on a factor marked by zero-sum beliefs about gender discrimination. A final item was weakly related to both factors. However, the two Promax-rotated factors correlated strongly in a positive direction, r = .82, supporting the notion that these two specific dimensions are aspects of the more general BSS dimension.