Evidence-Based Reviews: Trends in Nephrology Nursing

Affiliations.

- 1 Nurse Practitioner, Hemodialysis, London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario, Canada.

- 2 Member of the ANNA Research Committee.

- 3 member of ANNA's MichigANNA Chapter.

- 4 Research Assistant, London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario, Canada.

- PMID: 31009191

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is one of the essential components of nephrology nursing. Reviews of such evidence are important as a means to synthesize research findings into one meaningful form of data. Publication trends of evidence reviews in nephrology nursing are unknown. The purpose of this systematic review was to identify trends in publications of evidence reviews in the Nephrology Nursing Journal. Titles of all publications in the Nephrology Nursing Journal from January 2003 to September/October 2018 were reviewed. A total of 23 evidence reviews were identified and formed the basis of this systematic review. Narrative analysis and concept mapping were used to synthesize data. There was a trend toward systematic reviews of quantitative studies, as well as evidence reviews that focused on the topics of quality of life and access to health services. The need for systematic rigorous reporting is recommended for EBP, as well as future reviews on identified priority areas of research.

Keywords: evidence-based practice; literature review; nursing research; systematic review.

Copyright© by the American Nephrology Nurses Association.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Evidence-Based Nursing*

- Nephrology Nursing / trends*

- Periodicals as Topic*

- Publications / trends*

Volume 17 Number 2

Sustaining the renal nursing workforce.

Kathy Hill, Kim Neylon, Kate Gunn, Shilpa Jesudason, Greg Sharplin, Anne Britton, Fiona Donnelly, Irene Atkins and Marion Eckert

Keywords Renal, workforce, nurse, nephrology

For referencing Hill K et al. Sustaining the renal nursing workforce. Renal Society of Australasia Journal 2021; 17(2):5-11.

DOI https://doi.org/10.33235/rsaj.17.2.5-11 Submitted 20 May 2021 Accepted 27 July 2021

Background The prevalence of kidney disease continues to increase, as does the acuity of kidney care. Patients with kidney failure are older, sicker and less mobile. Health systems are under more pressure to manage growing care needs and capacity constraints. This is likely to have an impact on nursing workforce experiences.

Aims The aim of this research was to examine nephrology nursing in South Australia to understand the impact of increasing acuity and organisational factors that may support and sustain the workforce.

Methods An exploratory semi-structured qualitative approach, facilitating eight focus groups with 36 nephrology nurses across six public metropolitan renal units was applied. Data were thematically analysed.

Findings Three central themes relating to nursing culture, patient acuity and organisational factors that impact the nursing workforce were identified. Sub-themes identified were pride and passion, teamwork and collegiality, increasing patient acuity and the lack of clinical rationalisation in kidney care, the value of a ‘flat’ hierarchy, and vulnerability during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Consequently, we identified a disconnect between institutional expectations and what the participants considered pragmatic reality. Participants reported sustained workplace pressure, a ‘triage’ approach to care, and a sense of work left undone.

Conclusion Nephrology nurses experience a gap between ‘supply and demand’ on their time, resources and workload. These findings highlight the need for further exploration of the root causes and the development of new systems to provide quality, safe and rewarding care for patients and to reduce the risk of workforce moral distress and burnout.

Introduction

The burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Australia and New Zealand is high; it is estimated to affect one in 10 people over the age of 18 (Kidney Health Australia, 2020). As reported by the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA, 2019), 26,746 Australian and New Zealanders received kidney replacement therapy (KRT) for kidney failure in 2019. The provision of KRT (haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis and transplantation) nursing care is a highly specialised field (Wolfe, 2014).

However, limited research has been undertaken in the nephrology specific nursing workforce and the unmet workplace needs of nephrology nurses are not well reported (Brown et al., 2013).The shortage in the nephrology nursing workforce has largely been considered a “subset of overall supply” (Wolfe, 2014); however, with a significant number of vacancies in positions globally and increases in population level kidney failure, the nephrology nursing specialty is under additional pressure (Wolfe, 2014). Nurses in kidney care have a unique relationship with the people that they care for because of the lengthy and intensive context of care (Brown et al., 2013; Wolfe, 2014). Evidence suggests that the intensity of job burnout resulting from high stress environments is particularly high among dialysis nurses (Hayes, Douglas, & Bonner, 2015) and that job satisfaction and “organisational justice” is a critical factor that can ameliorate the negative effects of burnout (Hayes, Douglas, & Bonner, 2014; Kavurmacı, Cantekin, & Tan, 2014). Stress in nephrology nursing occurs due to increased pressure in the workplace without an associated increase in satisfaction with the job (Jones, 2014), the complexity of care, and unrealistic patient expectations (Dermody & Bennett, 2008). Inadequate staffing has been cited as a driver of stress and burnout and is correlated with nursing turnover. In turn, nursing turnover can disrupt care continuity and increase adverse events for patients (Gardner et al., 2007). Therefore, workforce renewal will be required to sustain this vitally important skilled nursing workforce and reduce turnover into the future.

The aim of this research was to examine nephrology nursing experiences in South Australia in order to understand the impact of increasing acuity on the workforce and on patients, and determine organisational factors that may support and sustain the nursing workforce.

Research methodology

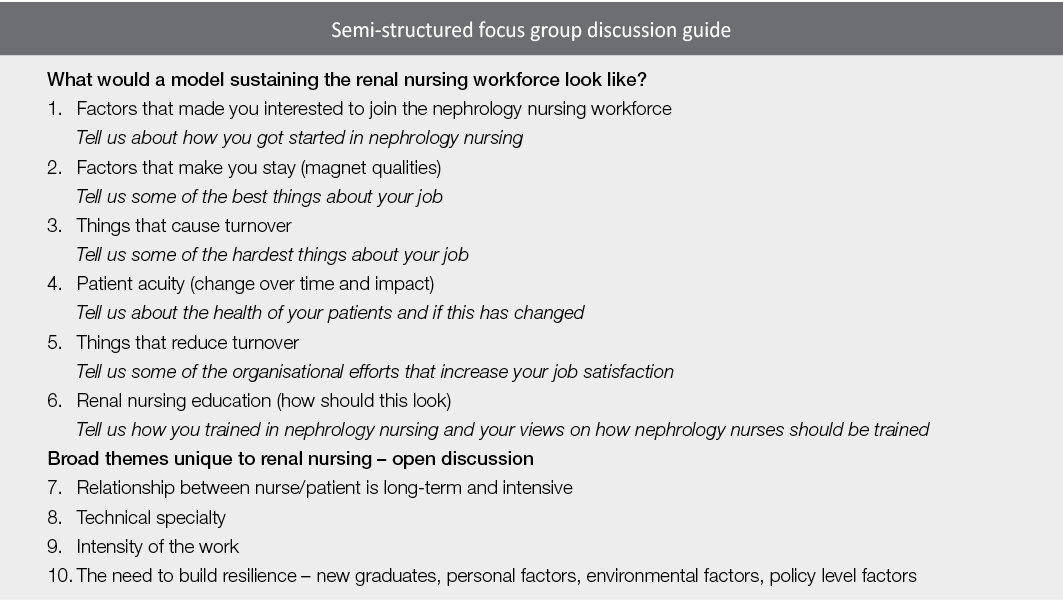

This research used a qualitative focus group methodology with nephrology nurses in both acute and satellite care settings utilising a semi-structured method (Jayasekara, 2012). A focus group discussion guide (Figure 1) was used to explore how factors such as patient acuity, complex care, workplace culture, values, time, finances, shift work, overtime, and professional development opportunities affect decision making about and satisfaction with work, while also allowing participants to raise topics they considered most important. The focus group discussion guide was developed following an extensive review of the existing literature on this topic.

Figure 1. Semi-structured focus group discussion guide

The focus groups were conducted in six South Australian renal units; they were 1–2 hours in duration and audio-recorded, and field notes were also taken. A private room in the renal unit setting was booked ahead of time to allow participants to leave their workplace to participate. Two members of the research team facilitated the focus groups, one a senior renal nurse [KH PhD], the other a qualitative ethnographic researcher with no renal expertise [KN PhD]. The benefits of dual facilitators reduced perceived prior knowledge ‘leading’ the discussion.

Participants self-selected to participate by responding to a flyer advertising the research.

Data analysis

The audio recordings were de-identified and professionally transcribed verbatim; the researchers used NVivo 12™ to support coding trees and discourse analysis to code the data into common themes (Liamputtong, 2011). Discourse analysis uses not only the words in the transcripts but also the relationships seen between participants in the focus groups using the extensive field notes taken during the discussion. This analysis was conducted in the first instance independently by the focus group facilitators and then jointly examined for correlating themes. Data saturation was confirmed by the determination of several similar themes in all of the focus groups.

Ethical considerations

The research received approval from a human research ethics committee (CALHN HREC 12818) and all participants gave informed written consent. They were also assured of anonymity of both their identity and the specific renal unit in the reporting of the findings. Key findings in an abbreviated form were discussed with the units involved and all members of the research team before the analysis was finalised.

Thirty-six renal nurses participated in eight focus groups across six public metropolitan renal units, and included those working in leadership roles, haemodialysis, renal wards, peritoneal dialysis, transplantation and clinical trials. Participants had a range of experience in renal nursing from new graduates in their first year, mid-career nurses and those with over 30 years’ experience. Participants were predominantly female (97%, n=35).

Three broad themes were identified from the data: nursing culture, workforce education and professionalism; patient-related factors impacting on the workforce; and macroenvironmental factors impacting on the workforce.

Nursing culture, workforce education and professionalism

This theme explored the sustainability of the nephrology nursing workforce in relation to nursing culture, training modules and succession planning.

Experience versus recognised qualification: a false dichotomy in renal nurse training

There are currently two models of renal nurse education available to South Australian nursing clinicians. Trainees either undertake a university-accredited postgraduate qualification offered remotely from another state, or a hospital-based training program offered here in South Australia. Participants described fundamental flaws in this hybrid model that presents a false dichotomy:

That’s why nursing did go into the university sector to bring up the professionalism but often forgetting that it is a hands on role and we do a lot of our learning with our patients, you know, actually getting our hands dirty so to speak [FG 2].

Nurses also described the gradual and total erosion of renal specific in-place education opportunities in their units as patient numbers and acuity increased. No participants were able to describe any recent workplace-dedicated education sessions for nephrology nurses.

Training the future workforce in difficult working environments

In South Australia the three universities train a large number of undergraduate student nurses every year to address a predicted future workforce shortfall. This creates pressure on renal units already overwhelmed to find time to train the future workforce:

I could hear myself sometimes when say a student or someone would ask me something and I love teaching, I love working with students, I love working with the new grads, and I could hear this voice sometimes that was a bit snappy. I thought that’s not me, that’s awful [FG 4].

There was, however, a keen sense of the importance of developing early career nurses to sustain the renal nursing workforce, particularly given the increasing age of the nursing workforce overall.

Pride, enjoyment and passion

Nephrology nurses in South Australia consistently described themselves as proud of the work they do. They describe the capacity to “make a difference” and a passion for their specialty. Many of the more senior nurses described entering renal nursing almost by accident but “falling in love” with the specialty with very little intention of leaving:

I mean, it’s a fantastic area to work in. I didn’t know anything about renal at all before I came here. I love it. I’m passionate about renal. I love it. It’s very rewarding [FG 8].

Teamwork and collegiality

Whilst describing their challenges in an open way, participants also reported pride in their collegiality, teamwork and capacity to support each other:

Sometimes you just make yourself even later home by having a chat in the car park. Sometimes we stand in the wind and the rain and we don’t care [FG 3].

Supporting each other and working as a team is described as integral to a successful shift, especially after a challenging day. There was also consistent evidence of the extreme dedication that renal nurses have towards each other and towards their patients:

To be honest, even though I get annoyed about the staffing levels and whatever I get annoyed about that sort of side of it, it’s the patients you stay for and it’s the staff members that you stay for. Because we have got some beautiful patients and we’ve got some beautiful staff members [FG 8].

Patient-related factors impacting on the workforce

This theme explored the patient-related factors that supported the workforce culture or were a negative aspect of care.

The long-term trajectory of the patient/nurse relationship

A consistent theme raised by participants when discussing patient satisfaction was the longevity of patient/nurse relationships. Participants in all focus groups described how the long-term nature of the patient/nurse relationship generates a sense of closeness:

It’s like a family. In maintenance dialysis unit. The nurse/patient relationship is there but it’s more like a family. You’re caring like your family member [FG 2].

The nurses described continuity of care and emotional connection to their long-term patients in positive and endearing terms, often highlighting this as the most appealing aspect of renal nursing. While participants were saddened when seeing patients “at their worst” and witnessing the inevitable downward trajectory of their renal journey, their experience helping the patient and their families through that journey was often seen as a privilege and a highlight of their nursing careers. However, participants also indicated significant frustration and regret that increased patient acuity, ageing patients, and nurse/patient ratios limited their capacity to connect significantly with all patients.

Increased patient acuity, acute deterioration risk and safety

All participants reported experiencing a significant increase in patient acuity over the past few years, describing a much older, more frail dialysis population:

Patients are living longer. We have about four patients from nursing homes that come in, that you question why you even dialyse them. But the acuity of the patient is so much, is so different to what it used to be years ago. So different. They have so many more comorbidities. They yeah, they’re just more difficult. They have heart conditions that you can’t even dialyse them. You can’t even remove their fluid, so they’re in and out of hospital all the time [FG 5].

Many of the participants described patients that met medical emergency team (MET) criteria before dialysis treatment had even commenced. There was a strong sense that the units were struggling to find ways to manage these unwell patients, along with the rest of their patient group, and the use of the word ‘safe’ frequently occurred:

Just the increase in their acuity and all the comorbidities that they have and they’re getting sicker, they’re getting older, and we’re still in the process of finding ways to manage patient and staff safety and wellbeing [FG 3].

Participants also described a major change in the mobility of the patients, discussing the scene “ten or so years ago” when most people needing treatment walked into the unit and physically participated in their care. Participants remarked that this is simply no longer the case, with descriptions of lifting and carrying patients:

Three to four sling lifters, to chair lifters, it all takes time. So, let’s say we organise half an hour slots for putting on a (dialysis) patient, sometimes we might take 20 minutes to even get the stand lifters and get them into chair, let alone another 10 minutes to put on (dialysis) [FG 6].

Caseload pressure and limitations for patient care

Participants described a “conveyor belt” mentality in the dialysis units, with a sense of urgency to get people “in, on, and out” due to high caseloads. Staff described the pressing need for three shifts of patients per day and internal pressure to move patients through, and pressure on patients to rush the discharge; these factors reduced job satisfaction considerably:

I would say it was more stressful and I’d also say it impacts on your job satisfaction because you go home feeling like you haven’t done a good job even though you have and that you would have worked well within parameters. You go home and you think, on reflection, I don’t think you’re satisfied. I think you feel inept [FG 3].

Nurse/patient ratios in the setting of changing acuity

Renal nurses in South Australia accepted a standardised State-wide model for nurse-to-patient ratios several years ago that is still used to supply staff to renal units. Many of the focus group participants expressed regret regarding this agreement, as they believe it no longer reflects the actual nursing care hours needed due to the increased complexity of the people undergoing dialysis:

You do this many treatments therefore there’s this many staff and that is your barrier that you have to fight and prove that you require that extra staff member because why do you need that because you’ve only got this many patients, well that’s because this person is nearly dead and if I leave his side he’s going to be [FG 1].

Stress and responsibility

Participants overwhelmingly described a culture of chronic stress in the workplace. This was not just in dialysis units, but also in renal wards:

Like, it was so scary. Everybody was so sick and sometimes you had very little support and it was very intimidating looking after these very sick patients and sometimes you could be that second to most senior nurse as a graduate or the most senior on a night shift [FG 2].

On an afternoon shift, you never have a meal break, ever [FG 8].

Whilst all participants described nursing leadership support, they struggled to identify any organisational support for the difficulties and challenges centred within the specialty area. Participants across the board described having to source their own replacement staff to cover sick leave or work overtime, and at times the inability to support the team:

As a Shift Coordinator you just, you can see someone and you desperately want to help them but you’ve got 7 million other things you’re trying to deal with, it’s horrible, really, really horrible, it’s just like you spend a whole day trying to put out whatever fire is burning the most at that second and it’s awful [FG 4].

The patient as an expert

Renal nurses described the uniqueness of the renal patient and their “expertise”. This was genuinely viewed as a partnership for successful treatment. An ideal model of care was seen to involve an active patient:

A lot of, most of them are a knowledgeable group about their own healthcare so they can be quite strong advocates for themselves and are willing to question and I think the staff actually like that. We all like that these patients are questioning and challenging [FG 2].

However, participants also raised a downside to this, namely patient reliance on individual staff members, as long-term relationships facilitated trust or distrust in particular staff, particularly new staff members. Newly graduated nurses described being intimidated by patients that refused to allow them to perform tasks, for example to cannulate a fistula, because of a lack of trust in their ability:

Oh, who is this person, I’ve never seen you. Do you know how to needle? I don’t think you want to needle me [FG 6].

Overall, participants described the capacity to gain trust, and the sense that the patient as an active participant in managing their chronic condition was welcomed by the nursing staff.

Macroenvironmental factors impacting on the workforce

This theme explored factors that were impacting on the workforce that were organisational and external to the participants.

Lack of clinical rationalisation in kidney care impacting on nursing morale

A factor described as increasing the pressure on the nursing workforce was their perceived powerlessness when it comes to assessing a patient as “too unwell for dialysis” and the decision not being supported by the medical staff. Participants felt that, once a dialysis pathway is chosen, irrespective of the nurses’ beliefs about the patient’s capacity to cope with that treatment, there is pressure on the nursing staff from the medical team to find a way to complete the dialysis treatment:

We have patients here that, once upon a time, wouldn’t dialyse. They are so hypotensive, for example, and you’ll ring the renal registrar but the expectation in many cases is you dialyse them [FG 3].

Sentiments surrounded the way that the participants experienced the increasingly complex ageing population, the increasing burden of all that was expected from them with patients that they felt would have been considered too unwell previously. This theme described a despondent workforce that sometimes felt that they are unable to meet the needs of all deteriorating patients at all times.

A “flat hierarchy” and respect in the workplace

Several units described a “flat hierarchy” where nephrology nurses were respected and valued by the medical teams; this created a very positive workplace culture and increased job satisfaction:

And it’s always been strongly encouraged that if you’re not happy with something miss out the middle man, women, go straight to the consultant, and I think every renal nurse would have no qualms in, whether it’s the middle of the night if they felt something unsafe was happening, giving the consultant a call [FG 2].

Many nurses attributed this to the positive attitudes of doctors towards nurses and described close collegial relationships between the nursing and medical staff; this was celebrated as a positive aspect of nephrology nursing and care coordination.

The “old model for the new reality”: physical space constraints

There is a large degree of commonly felt dissatisfaction with the physical space provisions in renal units, described here as “the old model for a new reality”. Many units report simply having inadequate space and this relates to increased patient numbers, increased use of mobility aids, and increasing numbers of patients requiring dialysis, many of whom are so ill they are in a bed that is much larger than the space designed for the treatment. This was echoed in the units that had a central nursing station and patient stations placed in a circle around this, a model commonly seen in renal units:

And you’re now putting beds in there and sometimes it could look like a war zone [FG 7].

COVID‑19 and workforce vulnerability

This research was conducted in South Australia during the COVID‑19 pandemic which, whilst creating logistic difficulties in terms of research access and social distancing, brought additional insights into the pressure on the nephrology nursing workforce as participants considered the consequences of a potential outbreak in a dialysis facility:

I guess the difference is you can’t get someone else to come and cover from anywhere else. No one else can lend a hand [FG 3].

However, participants also described a common sense of purpose in upskilling as much of the nursing workforce as possible in preparation for the pandemic:

So, that’s where we’re concentrating because we had massive changes with the COVID happening and we had lots of people coming through upskilling. So, that was a major breakthrough for us in opening our eyes into saying, “Yes, we can do this. Yes, we can change things around” [FG 6].

The global COVID‑19 pandemic brought recognition to participants of their own strong commitment to nursing, but also a perceived increased recognition of the vulnerable position nurses put themselves in to help others in the wider community:

But COVID’s been the perfect example. Like we’ve been thanked so many times. I don’t think we’ve ever been thanked, well not as many times [FG 2].

This research found that nephrology nurse participants felt pride in their work, but often felt overwhelmed or “powerless” in the face of a rapidly changing renal patient population. Maintaining a professional identity is a strong predictor of personal accomplishment and the driving force “to keep going” (Georgios et al., 2017) and was expressed keenly by the participants of this research. However, increasing patient numbers, increasing patient acuity and physical space constraints led to the staff trying manage an old model of a dialysis unit based upon a smaller, younger and more independent cohort of patients around which renal units were designed, and not being able to successfully manage this. There is also evidence of sustained workplace pressure and a sense of work left “undone”, leading to increasing job dissatisfaction. White, Aiken and McHugh (2019) have previously discussed the interdependent concepts of working in an under-resourced setting creating stress and moral distress due to missed care in nursing (White et al., 2019), something which was evidenced in our focus group discussions.

In addition, Bong (2019) identified that the attrition rate for new graduates is a result of “moral distress”, a concept whereby the carer knows the right thing to do but is unable to do this due to institutional or resource constraints, and this is compelling enough to cause staff turnover. Whilst we spoke to graduates that were happy with their choice of specialty, senior staff indicated limitations in the training of graduates and students, particularly time restraints, that limited recruitment generally. This research also found that renal nurses wanted organisational acknowledgement, both of the new reality of renal care (compared to 20–30 years ago) and of their endeavours to combat structural constraints, to feel a sense of workplace achievement.

Hospital organisational culture has been found to be a dominant predictor of the quality of nursing care, and nurses, being a caring profession, are drawn to organisations that address “daily census” with appropriate staff patient ratios to increase the quality of care (Mudallal et al., 2017). Whilst intrinsic factors can reduce the impact of stress and burnout, critical to supporting nurses to cope with stress is addressing the macroenvironment with “adequate staffing, appropriate skill mix and support to manage extremely unwell patients” (Jones, 2014). Challenges were evident in participant experiences throughout the state, as they reported feelings of helplessness in the face of growing numbers, patient acuity and time constraints. This was most evident in concerns raised regarding patient safety and the pressure in maintaining visible composure in a chaotic environment. Nevertheless, participants overwhelmingly demonstrated pride in their work and a passion for renal care despite these structural constraints.

This research also provides evidence of a disconnect between the model of care utilised by hospitals and the increasing complexity of renal care. It highlights a need to consider alternative approaches to the delivery of renal care rather than a ‘business as usual’ service delivery that participants describe as inadequate and lowering both staff satisfaction and the quality of care for renal patients. This finding is particularly pertinent for renal staff here in South Australia, as the supply demand gap is widening, resulting in burnout and turnover (Halter et al., 2017). However, its impact could be applicable to renal nursing elsewhere where renal units may be experiencing the same increased acuity and structural constraints.

Whilst we acknowledge the inherent challenges of generalising from qualitative research, the four key findings from this research include:

- The renal nursing workforce has a strong internal supportive culture.

- The working environment and professional development opportunities need to be re-considered (larger spaces and increased training opportunities required).

- Changing patient acuity management requires modifications to the nurse/patient ratio model.

- Attracting nurses to the renal specialty is reliant on changes to the current education model and strategies to attract early career nurses to the speciality.

Limitations and strengths

We acknowledge a limitation of the focus group methodology is that participants self-selected, that senior and junior staff were interviewed together, and that being interviewed as teams could prioritise dominant voices and silence passive ones. Potentially the impact of COVID‑19 on the health system and staff could also confound some of the findings due to the contemporary pressures of the global pandemic. The strength of this research is participants from multiple sites with varying degrees of experience and the experienced facilitators.

In conclusion, the nephrology nurse focus groups undertaken across metropolitan South Australia found evidence of a dedicated and highly specialised nursing profession who described caring for a much larger and more complex cohort of patients under markedly different circumstances than the hospital renal unit structures and systems were designed to cope with. Consequently, a disconnect between institutional expectations and the pragmatic reality perceived by nurses caused these clinicians to feel unsupported and forced into what could be described as a ‘triage’ approach to care. Workplace culture was reported as particularly important with regard to the respect and recognition showed by senior staff both within the nursing teams, other staff such as doctors, other wards whose work intersected with renal, and the institution as a whole. This appeared to be crucial to job satisfaction and a sense of control and had an impact on their patient care. Overall, this research highlights the need for further study into the causes of changing workplace pressures and opportunities for organisations to explore and address key issues that are currently negatively impacting upon patient care and staff retention in this important nursing specialty.

Future work in this area

In addressing the nephrology nursing supply and demand issue that is emerging, research needs to focus on not just the current situation but in developing strategies to create solutions. This is vital to inform organisations how best to support the nephrology nursing workforce to ensure its sustainability. Phase 2 of our research will be investigating the sustainability of the nephrology nursing workforce using a discrete choice quantitative methodology (DCM) via a national workforce survey informed by the findings of this study. The themes developed in this qualitative work will guide the development of a DCM survey that will help us to work towards developing quantitative workforce models to understand and develop strategies to sustain the nephrology nursing workforce. Phase 2 is funded by Kidney Transplant Diabetes Research Australia and will be used to inform the National Strategic Action Plan on Kidney Disease.

Acknowledgements / Funding statement

The researchers would like to thank all of the renal nurses who participated in this study for their time, thoughts, ideas and expert opinions. This research was funded by a project specific grant from the Rosemary Bryant Foundation South Australia. Would also like to acknowledge the Rosemary Bryant AO Research Centre, University of South Australia for their support in progressing this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Dr Kathy Hill PhD MPH Grad Cert (Neph) BN RN Lecturer in Nursing University of South Australia, SA, Australia

Dr Kim Neylon PhD University of South Australia, SA, Australia

Dr Kate Gunn PhD University of South Australia, SA, Australia

Dr Shilpa Jesudason MBBS, FRACP, PhD Central Northern Adelaide Renal Transplantation Service (CNARTS), SA, Australia

Greg Sharplin Mpsych (Org & HF) MSc (Epi) University of South Australia, SA, Australia

Anne Britton Clinical Practice Director, Central Northern Adelaide Renal Transplantation Service (CNARTS), SA, Australia Fiona Donnelly MNP Central Northern Adelaide Renal Transplantation Service (CNARTS), SA, Australia

Irene Atkins CNM Renal Unit FMC SALHN, SA, Australia

Professor Marion Eckert PhD University of South Australia, SA, Australia

Correspondence to Dr Kathy Hill, Lecturer in Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery City East Campus University of South Australia Email [email protected]

Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA). (2019). Annual report. South Australia: ANZDATA.

Bong, H. E. (2019). Understanding moral distress: How to decrease turnover rates of new graduate pediatric nurses. Pediatric Nursing, 45 , 109–114.

Brown, S., Bain, P., Broderick, P., & Sully, M. (2013). Emotional effort and perceived support in renal nursing: A comparative interview study. Journal of Renal Care, 39, 246–255.

Dermody, K., & Bennett, P. N. (2008). Nurse stress in hospital and satellite haemodialysis units. Journal of Renal Care, 34 (1), 28–32.

Gardner, J. K., Thomas-Hawkins, C., Fogg, L., & Latham, C. E. (2007). The relationships between nurses’ perceptions of the hemodialysis unit work environment and nurse turnover, patient satisfaction, and hospitalizations. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 34, 271–81.

Georgios, M., Theodora, K., Eugenia, M., Christos, T., Smaragdi, K., Athina, K., & Alexandra, D. (2017). Is self-esteem actually the protective factor of nursing burnout? International Journal of Caring Sciences, 10, 1348–1359.

Halter, M., Boiko, O., Pelone, F., Beighton, C., Harris, R., Gale, J., Gourlay, S., & Drennan, V. (2017). The determinants and consequences of adult nursing staff turnover: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research, 17, 824–824.

Hayes, B., Douglas, C., & Bonner, A. (2014). Predicting emotional exhaustion among haemodialysis nurses: A structural equation model using Kanter’s structural empowerment theory. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 2897–2909.

Hayes, B., Douglas, C., & Bonner, A. (2015). Work environment, job satisfaction, stress and burnout among haemodialysis nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 23, 588–598.

Jayasekara, R. S. (2012). Focus groups in nursing research: Methodological perspectives. Nursing Outlook, 60, 411–416.

Jones, C. (2014). Stress and coping strategies in renal staff. Nursing Times, 110, 22–25.

Kavurmacı, M., Cantekin, I., & Tan, M. (2014). Burnout levels of hemodialysis nurses. Renal Failure, 36, 1038–1042.

Kidney Health Australia. (2020). Chronic kidney disease management in primary care (4th ed). Melbourne: Kidney Health Australia.

Liamputtong, P. (2011). Focus group methodology: Principles and practice. London: Sage Publishing.

Mudallal, R. H., Saleh, M. Y. N., Al-Modallal, H. M., & Abdel-Rahman, R. Y. (2017). Quality of nursing care: The influence of work conditions, nurse characteristics and burnout. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 7, 24–30.

White, E. M., Aiken, L. H., & McHugh, M. D. (2019). Registered nurse burnout, job dissatisfaction, and missed care in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 67, 2065–2071.

Wolfe, W. A. (2014). Are word-of-mouth communications contributing to a shortage of nephrology nurses? Nephrology Nursing Journal, 41, 371–378.

Previous Article

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 30 July 2020

The current and future landscape of dialysis

- Jonathan Himmelfarb ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3319-1224 1 , 2 ,

- Raymond Vanholder ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2633-1636 3 ,

- Rajnish Mehrotra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2833-067X 1 , 2 &

- Marcello Tonelli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0846-3187 4

Nature Reviews Nephrology volume 16 , pages 573–585 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

86k Accesses

258 Citations

130 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Haemodialysis

- Health care economics

- Health services

- Medical ethics

The development of dialysis by early pioneers such as Willem Kolff and Belding Scribner set in motion several dramatic changes in the epidemiology, economics and ethical frameworks for the treatment of kidney failure. However, despite a rapid expansion in the provision of dialysis — particularly haemodialysis and most notably in high-income countries (HICs) — the rate of true patient-centred innovation has slowed. Current trends are particularly concerning from a global perspective: current costs are not sustainable, even for HICs, and globally, most people who develop kidney failure forego treatment, resulting in millions of deaths every year. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop new approaches and dialysis modalities that are cost-effective, accessible and offer improved patient outcomes. Nephrology researchers are increasingly engaging with patients to determine their priorities for meaningful outcomes that should be used to measure progress. The overarching message from this engagement is that while patients value longevity, reducing symptom burden and achieving maximal functional and social rehabilitation are prioritized more highly. In response, patients, payors, regulators and health-care systems are increasingly demanding improved value, which can only come about through true patient-centred innovation that supports high-quality, high-value care. Substantial efforts are now underway to support requisite transformative changes. These efforts need to be catalysed, promoted and fostered through international collaboration and harmonization.

The global dialysis population is growing rapidly, especially in low-income and middle-income countries; however, worldwide, a substantial number of people lack access to kidney replacement therapy, and millions of people die of kidney failure each year, often without supportive care.

The costs of dialysis care are high and will likely continue to rise as a result of increased life expectancy and improved therapies for causes of kidney failure such as diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease.

Patients on dialysis continue to bear a high burden of disease, shortened life expectancy and report a high symptom burden and a low health-related quality of life.

Patient-focused research has identified fatigue, insomnia, cramps, depression, anxiety and frustration as key symptoms contributing to unsatisfactory outcomes for patients on dialysis.

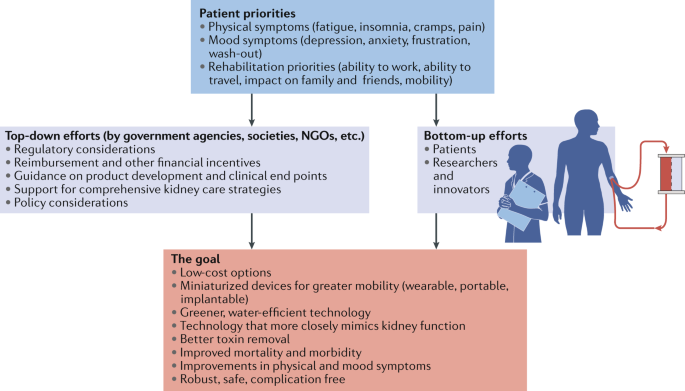

Initiatives to transform dialysis outcomes for patients require both top-down efforts (that is, efforts that promote incentives based on systems level policy, regulations, macroeconomic and organizational changes) and bottom-up efforts (that is, patient-led and patient-centred advocacy efforts as well as efforts led by individual teams of innovators).

Patients, payors, regulators and health-care systems increasingly demand improved value in dialysis care, which can only come about through true patient-centred innovation that supports high-quality, high-value care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Long-term kidney outcomes of semaglutide in obesity and cardiovascular disease in the SELECT trial

Acute kidney injury

An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success

Introduction.

Haemodialysis as a treatment for irreversible kidney failure arose from the pioneering efforts of Willem Kolff and Belding Scribner, who together received the 2002 Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award for this accomplishment. Kolff treated his first patient with an artificial kidney in 1943 — a young woman who was dialysed 12 times successfully but ultimately died because of vascular access failure. By 1945, Kolff had dialysed 15 more patients who did not survive, when Sofia Schafstadt — a 67-year-old woman who had developed acute kidney injury — recovered, becoming the first long-term survivor after receipt of dialysis. In 1960, Belding Scribner, Wayne Quinton and colleagues at the University of Washington, WA, USA, designed shunted cannulas, which prevented the destruction of blood vessels and enabled repeated haemodialysis sessions. The first patient who received long-term treatment (named Clyde Shields) lived a further 11 years on haemodialysis. In their writings, both Kolff and Scribner eloquently described being motivated by their perception of helplessness as physicians who had little to offer for the care of young patients who were dying of uraemia and stated that the goal of dialysis was to achieve full rehabilitation to an enjoyable life 1 .

The potential to scale the use of dialysis to treat large numbers of patients with kidney failure created great excitement. At the 1960 meeting of the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs (ASAIO), Scribner introduced Clyde Shields to physicians interested in dialysis, and Quinton demonstrated fabrication of the shunt. The following decade saw rapid gains in our understanding of kidney failure, including the discovery of uraemia-associated atherogenesis and metabolic bone disease, and in virtually every aspect of haemodialysis, including improvements in dialyser technology, dialysate composition, materials for haemocompatibility and water purification systems. The Scribner–Quinton shunt rapidly became an historical artefact once Brescia and colleagues developed the endogenous arteriovenous fistula in 1966 (ref. 2 ), and prosthetic subcutaneous interpositional ‘bridge’ grafts were developed shortly thereafter. Concomitant with these pioneering efforts, in 1959, peritoneal dialysis (PD) was first used successfully to sustain life for 6 months. Within 2 years a long-term PD programme was established in Seattle, WA, USA, and within 3 years the first automated PD cycler was developed 3 .

In 1964, Scribner’s presidential address to the ASAIO described emerging ethical issues related to dialysis, including considerations for patient selection, patient self-termination of treatment as a form of suicide, approaches to ensure death with dignity and selection criteria for transplantation 4 . Indeed, the process of selecting who would receive dialysis contributed to the emergence of the field of bioethics. The early success of dialysis paradoxically created social tensions, as access to this life-sustaining therapy was rationed by its availability and the ‘suitability’ of patients. In the early 1970s, haemodialysis remained a highly specialized therapy, available to ~10,000 individuals, almost exclusively in North America and Europe, with a high frequency of patients on home haemodialysis. In a portentous moment, Shep Glazer, an unemployed salesman, was dialysed in a live demonstration in front of the US Congress House Ways and Means Committee. Soon thereafter, in October 1972, an amendment to the Social Security Act creating Medicare entitlement for end-stage renal disease (now known as kidney failure), for both dialysis and kidney transplantation, was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Nixon.

The resulting expansion of dialysis, previously described as “from miracle to mainstream” 5 , set in motion dramatic changes 6 , including the development of a for-profit outpatient dialysis provider industry; relaxation of stringent patient selection for dialysis eligibility in most HICs; a move away from home towards in-centre dialysis; efforts on the part of single payors such as Medicare in the USA to restrain per-patient costs through the introduction of bundled payments and the setting of composite rates; the development of quality indicators — such as adequate urea clearance per treatment — that were readily achievable but are primarily process rather than outcome measures; consolidation of the dialysis industry, particularly in the USA owing to economies of scale, eventually resulting in a duopoly of dialysis providers; the development of joint ventures and other forms of partnerships between dialysis providers and nephrologists; the globalization of dialysis, which is now available, albeit not necessarily accessible or affordable in many low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs); and finally, a dramatic slowing in the rate of true patient-centred innovation, with incremental gains in dialysis safety and efficiency replacing the pioneering spirit of the early innovators.

The population of patients receiving dialysis continues to grow rapidly, especially in LMICs, as a result of an increase in the availability of dialysis, population ageing, increased prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and toxic environmental exposures. However, despite the global expansion of dialysis, notable regional differences exist in the prevalence of different dialysis modalities and in its accessibility. Worldwide, a substantial number of people do not have access to kidney replacement therapy (KRT), resulting in millions of deaths from kidney failure each year. Among populations with access to dialysis, mortality remains high and outcomes suboptimal, with high rates of comorbidities and poor health-related quality of life. These shortcomings highlight the urgent need for innovations in the dialysis space to increase accessibility and improve outcomes, with a focus on those that are a priority to patients. This Review describes the current landscape of dialysis therapy from an epidemiological, economic, ethical and patient-centred framework, and provides examples of initiatives that are aimed at stimulating innovations in dialysis and transform the field to one that supports high-quality, high-value care.

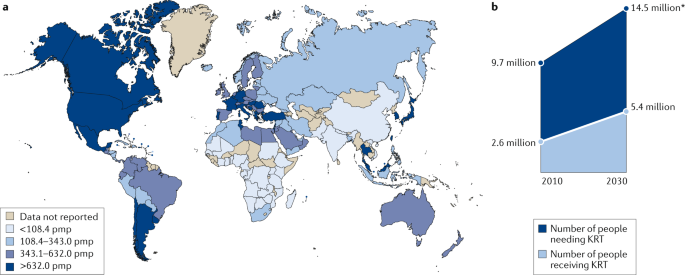

Epidemiology of dialysis

Kidney failure is defined by a glomerular filtration rate <15 ml/min/1.73 m 2 (ref. 7 ) and may be treated using KRT (which refers to either dialysis or transplantation) or with supportive care 8 . The global prevalence of kidney failure is uncertain, but was estimated to be 0.07%, or approximately 5.3 million people in 2017 (ref. 9 ), with other estimates ranging as high as 9.7 million. Worldwide, millions of people die of kidney failure each year owing to a lack of access to KRT 10 , often without supportive care. Haemodialysis is costly, and current recommendations therefore suggest that haemodialysis should be the lowest priority for LMICs seeking to establish kidney care programmes. Rather, these programmes should prioritize other approaches, including treatments to prevent or delay kidney failure, conservative care, living donor kidney transplantation and PD 11 . Nonetheless, haemodialysis is the most commonly offered form of KRT in LMICs, as well as in high-income countries (HICs) 12 , and continued increases in the uptake of haemodialysis are expected worldwide in the coming decades. Here, we review the basic epidemiology of kidney failure treated with long-term dialysis and discuss some of the key epidemiological challenges of the future (Fig. 1a ).

Growth is continuously outpacing the capacity of kidney replacement therapy (KRT), defined as maintenance dialysis or kidney transplant, especially in low-income and middle-income countries. a | Global prevalence of chronic dialysis. b | Estimated worldwide need and projected capacity for KRT by 2030. pmp, per million population. Adapted with permission from the ISN Global Kidney Health Atlas 2019.

Prevalence of dialysis use

Prevalence of haemodialysis.

Worldwide, approximately 89% of patients on dialysis receive haemodialysis; the majority (>90%) of patients on haemodialysis live in HICs or the so-called upper middle-income countries such as Brazil and South Africa 12 , 13 . The apparent prevalence of long-term dialysis varies widely by region but correlates strongly with national income 14 . This variation in prevalence in part reflects true differences in dialysis use 12 , 15 but also reflects the fact that wealthier countries are more likely than lower income countries to have comprehensive dialysis registries. Of note, the prevalence of haemodialysis is increasing more rapidly in Latin America (at a rate of ~4% per year) than in Europe or the USA (both ~2% per year), although considerable variation between territories exists in all three of these regions, which again correlates primarily (but not exclusively) with wealth 16 , 17 . The prevalence of haemodialysis varies widely across South Asia, with relatively high prevalence (and rapid growth) in India and lower prevalence in Afghanistan and Bangladesh 18 . Limited data are available on the prevalence of dialysis therapies in sub-Saharan Africa 19 . A 2017 report suggests that haemodialysis services were available in at least 34 African countries as of 2017, although haemodialysis was not affordable or accessible to the large majority of resident candidates 13 .

Prevalence of peritoneal dialysis

Worldwide, PD is less widely available than haemodialysis. In a 2017 survey of 125 countries, PD was reportedly available in 75% of countries whereas haemodialysis was available in 96% 20 . In 2018, an estimated 11% of patients receiving long-term dialysis worldwide were treated with PD; a little over half of these patients were living in China, Mexico, the USA and Thailand 21 .

Large variation exists between territories in the relative use of PD for treating kidney failure; in Hong Kong for example, >80% of patients on dialysis receive PD, whereas in Japan this proportion is <5% 22 . This variation is, in part, determined by governmental policies and the density of haemodialysis facilities 23 . In some countries such as the USA, rates of PD utilization also vary by ethnicity with African Americans and Hispanics being much less likely than white Americans to receive PD 24 . Disparate secular trends in PD use are also evident, with rapid growth in the use of PD in some regions such as the USA, China and Thailand and declining or unchanging levels of PD use in other regions, for example, within Western Europe 22 . As for haemodialysis, access to PD is poor in many LMICs for a variety of reasons, as comprehensively discussed elsewhere 25 .

Incidence of dialysis use

Following a rapid increase in dialysis use over a period of approximately two decades, the incidence of dialysis initiation in most HICs reached a peak in the early 2000s and has remained stable or slightly decreased since then 22 , 26 , 27 . Extrapolation of prevalence data from LMICs suggests that the incidence of dialysis initiation seems to be steadily increasing in LMICs 10 , 28 , 29 , 30 , with further increases expected over the coming decades. However, incidence data in LMICs are less robust than prevalence data, although neither reflect the true demand for KRT given the lack of reporting.

Of note, the incidence of dialysis initiation in HICs is consistently 1.2-fold to 1.4-fold higher for men than for women, despite an apparently higher risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in women 31 . Whether this finding reflects physician or health system bias, different preferences with regard to KRT, disparities in the competing risk of death, variation in rates of kidney function loss in women versus men, or other reasons is unknown and requires further study. Few data describe the incidence of haemodialysis by sex in LMICs.

Dialysis outcomes

Mortality is very high among patients on dialysis, especially in the first 3 months following initiation of haemodialysis treatment. Approximately one-quarter of patients on haemodialysis die within a year of initiating therapy in HICs, and this proportion is even higher in LMICs 32 , 33 , 34 . Over the past two decades, reductions in the relative and absolute risk of mortality have seemingly been achieved for patients on haemodialysis. Data suggest that relative gains in survival may be greater for younger than for older individuals; however, absolute gains seem to be similar across age groups 35 . Although controversial, improvements in mortality risk seem to have been more rapid among patients on dialysis than for the general population 36 , suggesting that better care of patients receiving dialysis treatments rather than overall health gains might be at least partially responsible for these secular trends. The factors responsible for these apparent trends have not been confirmed, but could include better management of comorbidities, improvements in the prevention or treatment of dialysis-related complications such as infection, and/or better care prior to the initiation of dialysis (which may translate into better health following dialysis initiation). Historically, although short-term mortality was lower for patients treated with PD than for those treated with haemodialysis, the long-term mortality risk was higher with PD 37 , 38 . In the past two decades, the reduction in mortality risk has been greater for patients treated with PD than with haemodialysis, such that in most regions the long-term survival of patients treated with PD and haemodialysis are now similar 39 , 40 , 41 .

Despite these improvements, mortality remains unacceptably high among patients on dialysis and is driven by cardiovascular events and infection. For example, a 2019 study showed that cardiovascular mortality among young adults aged 22–29 years with incident kidney failure was 143–500-fold higher than that of otherwise comparable individuals without kidney failure, owing to a very high burden of cardiovascular risk factors 42 . The risk of infection is also markedly greater among patients on dialysis than in the general population, in part driven by access-related infections in patients on haemodialysis with central venous catheters and peritonitis-related infections in patients on PD 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 . Hence, strategies to reduce the risk of infection associated with dialysis access should continue to be a high clinical priority.

The risk of mortality among patients on dialysis seems to be influenced by race. In the USA, adjusted mortality is lower for African American patients than for white patients on dialysis, although there is a significant interaction with age such that this observation held only among older adults, and the converse is actually true among younger African American patients aged 18 to 30 years 48 . A similar survival advantage is observed among Black patients compared with white patients or patients of Asian heritage on haemodialysis in the Netherlands 49 . In Canada, dialysis patients of indigenous descent have higher adjusted mortality, and patients of South Asian or East Asian ethnicity have lower adjusted mortality than that of white patients. In addition, between-region comparisons indicate that mortality among incident dialysis patients is substantially lower for Japan than for other HICs. Whether this difference is due to ethnic origin, differences in health system practices, a combination of these factors or other, unrelated factors is unknown 30 . No consistent evidence exists to suggest that mortality among incident adult dialysis patients varies significantly by sex 50 , 51 , 52 .

Other outcomes

Hospitalization, inability to work and loss of independent living are all markedly more common among patients on dialysis than in the general population 53 , 54 , 55 . In contrast to the modest secular improvements in mortality achieved for patients on dialysis, health-related quality of life has remained unchanged for the past two decades and is substantially lower than that of the general population, due in part to high symptom burden 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 . Depression is also frequent among patients on dialysis 60 , and factors such as high pill burden 61 , the need to travel to dialysis sessions and pain associated with vascular access puncture all affect quality of life 62 .

Future epidemiological challenges

The changing epidemiology of kidney failure is likely to present several challenges for the optimal management of these patients. For example, the ageing global population together with continuing increases in the prevalence of key risk factors for the development of kidney disease, such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension, mean that the incidence, prevalence and costs of kidney failure will continue to rise for the foreseeable future. This increased demand for KRT will undoubtedly lead to an increase in the uptake of haemodialysis, which will pose substantial economic challenges for health systems worldwide. Moreover, as growth in demand seems to be outpacing increases in KRT capacity, the number of deaths as a result of kidney failure is expected to rise dramatically (Fig. 1b ).

The same risk factors that drive the development of kidney disease will also increase the prevalence of multimorbidities within the dialysis population. These comorbidities will in turn require effective management in addition to the management of kidney failure per se 63 and will require technical innovations of dialysis procedures, as well as better evidence to guide the management of comorbidities in the dialysis population.

Finally, the particularly rapid increases in the incidence and prevalence of kidney failure among populations in LMICs will place considerable strain on the health systems of these countries. The associated increases in mortality resulting from a lack of access to KRT will create difficult choices for decision makers. Although LMIC should prioritize forms of KRT other than haemodialysis, some haemodialysis capacity will be required 11 , for example, to manage patients with hypercatabolic acute kidney injury or refractory PD-associated peritonitis, which, once available, will inevitably increase the use of this modality.

Health economy-related considerations

The cost of dialysis (especially in-centre or in-hospital dialysis) is high 64 , and the cost per quality-adjusted life-year associated with haemodialysis treatment is often considered to be the threshold value that differentiates whether a particular medical intervention is cost-effective or not 65 . Total dialysis costs across the population will probably continue to rise, owing to increases in life expectancy of the general population and the availability of improved therapeutics for causes of kidney failure such as diabetes mellitus, which have increased the lifespan of these patients and probably will also increase their lifespan on dialysis. KRT absorbs up to 5–7% of total health-care budgets, despite the fact that kidney failure affects only 0.1–0.2% of the general population in most regions 66 . Although societal costs for out-of-centre dialysis (for example, home or self-care haemodialysis, or PD) are in general lower than that of in-centre haemodialysis in many HICs, these options are often underutilized 67 , adding to the rising costs of dialysis.

Reimbursement for haemodialysis correlates with the economic strength of each region 68 , but in part also reflects willingness to pay . In most regions, the correlation curve for PD or reimbursement with respect to gross domestic product projects below that of in-centre haemodialysis, which in part reflects the lower labour costs associated with PD 68 . Unfortunately, little clarity exists with regard to the aggregated cost of single items that are required to produce dialysis equipment for both PD and haemodialysis and the labour costs involved in delivering haemodialysis 69 , which makes it difficult for governments to reimburse the real costs of haemodialysis.

Although increasing reimbursement of home dialysis strategies would seem to be an appropriate strategy to stimulate uptake of these modalities, evidence from regions that offer high reimbursement rates for PD suggests that the success of this strategy is variable 23 , 68 . However, financial incentives may work. In the USA, reimbursement for in-centre and home dialysis (PD or home haemodialysis) has for a long time been identical. The introduction of the expanded prospective payment system in 2011 further enhanced the financial incentives for PD for dialysis providers, which led to a doubling in both the absolute number of patients and the proportion of patients with kidney failure treated with PD 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 .

Although in countries with a low gross domestic product, dialysis consumes less in absolute amounts, it absorbs a higher fraction of the global health budget 68 , likely at the expense of other, potentially more cost-effective interventions, such as prevention or transplantation. Although society carries most of the costs associated with KRT in most HICs, some costs such as co-payment for drugs or consultations are borne by the individual, and these often increase as CKD progresses. In other regions, costs are covered largely or entirely by the patient’s family, leading to premature death when resources are exhausted 74 . In addition, costs are not limited to KRT but also include the costs of medication, hospitalizations and interventions linked to kidney disease or its complications (that is, indirect costs), as well as non-health-care-related costs such as those linked to transportation or loss of productivity.

Dialysis also has an intrinsic economic impact. Patients on dialysis are often unemployed. In the USA, >75% of patients are unemployed at the start of dialysis, compared with <20% in the general population 53 . Unemployment affects purchasing power but also lifestyle, self-image and mental health. Moreover, loss of productivity owing to unemployment and/or the premature death of workers with kidney failure also has economic consequences for society 75 . Therefore, continued efforts to prevent kidney failure and develop KRT strategies that are less time consuming for the patient and allow more flexibility should be an urgent priority. Concomitantly, employers must also provide the resources needed to support employees with kidney failure.

Hence, a pressing need exists to rethink the current economic model of dialysis and the policies that direct the choice of different treatment options. The cost of dialysis (especially that of in-centre haemodialysis) is considerable and will continue to rise as the dialysis population increases. Maintaining the status quo will prevent timely access to optimal treatment for many patients, especially for those living in extreme poverty and with a low level of education and for patients living in LMICs.

Ethical aspects

A 2020 review by a panel of nephrologists and ethicists appointed by three large nephrology societies outlined the main ethical concerns associated with kidney care 76 . With regard to management of kidney failure (Box 1 ), equitable access to appropriate treatment is probably the most important ethical issue and is relevant not only in the context of haemodialysis but also for the other modalities of kidney care (including transplantation, PD and comprehensive conservative care) 76 . Of note, conservative care is not equivalent to the withdrawal of treatment, but rather implies active management excluding KRT.

As mentioned previously, access to such care is limited in many countries 10 , 77 . Inequities in access to dialysis at the individual level are largely dependent on factors such as health literacy, education and socio-economic status, but also on the wealth and organization of the region in which the individual lives. Even when dialysis itself is reimbursed, a lack of individual financial resources can limit access to care. Moreover, elements such as gender, race or ethnicity and citizenship status 78 , 79 can influence an individual’s ability to access dialysis 80 . These factors impose a risk that patients who are most vulnerable are subject to further discrimination. In addition, without necessarily being perceived as such, dialysis delivery may be biased by the financial interests of dialysis providers or nephrologists, for example, by influencing whether a patient receives in-centre versus home dialysis, or resulting in the non-referral of patients on dialysis for transplantation or conservative care 81 , 82 .

A potential reason for the high utilization of in-centre haemodialysis worldwide is a lack of patient awareness regarding the alternatives. When surveyed, a considerable proportion of patients with kidney failure reported that information about options for KRT was inadequate 83 , 84 . Patient education and decision support could be strengthened and its quality benchmarked, with specific attention to low health literacy, which is frequent among patients on dialysis 85 . Inadequate patient education might result from a lack of familiarity with home dialysis (including PD) and candidacy bias among treating physicians and nurses. Appropriate education and training of medical professionals could help to solve this problem. However, the first step to increase uptake of home dialysis modalities is likely policy action undertaken by administrations, but stimulated by advocacy by patients and the nephrology community, as suggested by the higher prevalence of PD at a lower societal cost of regions that already have a PD-first policy in place 68 .

Although the provision of appropriate dialysis at the lowest possible cost to the individual is essential if access is to be improved 86 , approaches that unduly compromise the quality of care should be minimized or avoided. General frameworks to deal with this challenge can be provided by the nephrology community, but trade-offs between cost and quality may be necessary and will require consultation between authorities, medical professionals and patient representatives. Consideration must also be given to whether the societal and individual impact of providing dialysis would be greater than managing other societal health priorities (for example, malaria or tuberculosis) or investing in other sectors to improve health (for example, access to clean drinking water or improving road safety).

The most favourable approach in deciding the most appropriate course of action for an individual is shared decision-making 87 , which provides evidence-based information to patients and families about all available therapeutic options in the context of the local situation. Providing accurate and unbiased information to support such decision-making is especially relevant for conservative care, to avoid the perception that this approach is being recommended to save resources rather than to pursue optimal patient comfort. Properly done, shared decision-making should avoid coercion, manipulation, conflicts of interest and the provision of ‘futile dialysis’ to a patient for whom the harm outweighs the benefits, life expectancy is low or the financial burden is high 88 . However, the views of care providers do not always necessarily align with those of patients and their families, especially in multicultural environments 89 . Medical professionals are often not well prepared for shared decision-making, and thus proper training is essential 90 . Policy action is also required to create the proper ethical consensus and evidence-based frameworks at institutional and government levels 91 to guide decision-making in the context of dialysis care that can be adapted to meet local needs.

Box 1 Main ethical issues in dialysis

Equity in access to long-term dialysis

Inequities in the ability to access kidney replacement therapy exist worldwide; however, if dialysis is available, the ability to transition between different dialysis modalities should be facilitated as much as possible. Specific attention should be paid to the factors that most prominently influence access to dialysis, such as gender, ethnicity, citizenship status and socio-economic status

Impact of financial interests on dialysis delivery

Financial interests of dialysis providers or nephrologists should in no way influence the choice of dialysis modality and/or result in the non-referral of patients for transplantation or conservative care

Cost considerations

Local adaptations are needed to ensure that the costs of dialysis provision are as low as possible without compromising quality of care

The high cost of dialysis means that consideration must be given to whether the benefits obtained by dialysis outweigh those obtained by addressing other health-care priorities, such as malaria or tuberculosis

Shared decision-making

Shared decision-making, involving the patient and their family, is recommended as an approach to allow an informed choice of the most appropriate course to follow

Approaches to shared decision-making must be evidence based and adapted to local circumstances

Futile dialysis should be avoided

Proper training is required to prepare physicians for shared decision-making

Clinical outcomes to measure progress

Over the past six decades, the availability of long-term dialysis has prolonged the lives of millions of people worldwide, often by serving as a bridge to kidney transplantation. Yet, patients on dialysis continue to bear a high burden of disease, both from multimorbidity and owing to the fact that current dialysis modalities only partially replace the function of the native kidney, resulting in continued uraemia and its consequences. Thus, although dialysis prevents death from kidney failure, life expectancy is often poor, hospitalizations (particularly for cardiovascular events and infection) are frequent, symptom burden is high and health-related quality of life is low 22 , 92 , 93 .

Given the multitude of health challenges faced by patients on dialysis, it is necessary to develop a priority list of issues. For much of the past three decades, most of this prioritization was performed by nephrology researchers with the most effort to date focusing on approaches to reducing all-cause mortality and the risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events. However, despite the many interventions that have been tested, including increasing the dose of dialysis (in the HEMO and ADEMEX trials 94 , 95 ), increasing dialyser flux (in the HEMO trial and MPO trial 94 , 96 ), increasing haemodialysis frequency (for example, the FHN Daily and FHN Nocturnal trials 97 , 98 ), use of haemodiafiltration (the CONTRAST 99 , ESHOL 100 and TURKISH-OL-HDF trials 101 ), increasing the haemoglobin target (for example, the Normal Haematocrit Trial 102 ), use of non-calcium-based phosphate binders (for example, the DCOR trial 103 ), or lowering of the serum cholesterol level (for example, the 4D, AURORA and SHARP trials 104 , 105 , 106 ), none of these or other interventions has clearly reduced all-cause or cardiovascular mortality for patients on dialysis. These disappointments notwithstanding, it is important that the nephrology community perseveres in finding ways to improve patient outcomes.

In the past 5 years, nephrology researchers have increasingly engaged with patients to understand their priorities for meaningful outcomes that should be used to measure progress. The overarching message from this engagement is that although longevity is valued, many patients would prefer to reduce symptom burden and achieve maximal functional and social rehabilitation. This insight highlights the high symptom burden experienced by patients receiving long-term dialysis 92 , 93 , 96 , 107 . These symptoms arise as a consequence of the uraemic syndrome. Some of these symptoms, such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath and confusion or encephalopathy, improve with dialysis initiation 108 , 109 , 110 , but many other symptoms, such as depression, anxiety and insomnia do not. Moreover, other symptoms, such as post-dialysis fatigue, appear after initiation of haemodialysis.

Of note, many symptoms of uraemic syndrome might relate to the persistence of protein-bound uraemic toxins and small peptides (so-called middle molecules) that are not effectively removed by the current dialysis modalities. The development of methods to improve the removal of those compounds is one promising approach to improving outcomes and quality of life for patients on dialysis, as discussed by other articles in this issue.

Patients on dialysis report an average of 9–12 symptoms at any given time 92 , 93 , 107 . To determine which of these should be prioritized for intervention, the Kidney Health Initiative used a two-step patient-focused process involving focus groups and an online survey to identify six symptoms that should be prioritized by the research community for intervention. These include three physical symptoms (fatigue, insomnia and cramps) and three mood symptoms (depression, anxiety and frustration) 111 . Parallel to these efforts, the Standardizing Outcomes in Nephrology Group (SONG) workgroup for haemodialysis ( SONG-HD ) has identified several tiers of outcomes that are important to patients, caregivers and health-care providers. Fatigue was identified as one of the four core outcomes, whereas depression, pain and feeling washed out after haemodialysis were identified as middle-tier outcomes 112 , 113 , 114 . Along these same lines, the SONG workgroup for PD ( SONG-PD ) identified the symptoms of fatigue, PD pain and sleep as important middle-tier outcomes 115 , 116 . Despite the importance of these symptoms to patients on dialysis, only a few studies have assessed the efficacy of behavioural and pharmacological treatments on depression 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 . Even more sobering is the observation that very few, if any, published studies have rigorously tested interventions for fatigue or any of the other symptoms. The nephrology community must now develop standardized and psychometrically robust measures that accurately capture symptoms and outcomes that are important to patients and ensure that these are captured in future clinical trials 122 , 123 .

Approaches to maximizing functional and social rehabilitation are also important to patients with kidney failure. In addition to the above-mentioned symptoms, SONG-HD identified ability to travel, ability to work, dialysis-free time, impact of dialysis on family and/or friends and mobility as important middle-tier outcomes 112 , 113 , 114 . SONG-PD identified life participation as one of five core outcomes, and impact on family and/or friends and mobility as other outcomes that are important to patients 115 , 116 . Given the importance of these outcomes to stakeholders, including patients, it is imperative that nephrology researchers develop tools to enable valid and consistent measurement of these outcomes and identify interventions that favourably modify these outcomes.

Fostering innovation

As described above, the status quo of dialysis care is suboptimal. Residual symptom burden, morbidity and mortality, and economic cost are all unacceptable, which begs the question of what steps are needed to change the established patterns of care. Patients are currently unable to live full and productive lives owing to the emotional and physical toll of dialysis, its intermittent treatment schedule, the dietary and fluid limitations, and their highly restricted mobility during treatment. Current technology requires most patients to travel to a dialysis centre, and current modalities are non-physiological, resulting in ‘washout’, which is defined as extensive fatigue, nausea and other adverse effects, caused by the build-up of uraemic toxins between treatments and the rapid removal of these solutes and fluids over 4-h sessions in the context of haemodialysis. LMICs face additional difficulties in the provision of dialysis owing to infrastructural requirements, the high cost of this treatment, the need for a constant power supply and the requirement for high volumes of purified water. For LMICs, innovations that focus on home-based, low-cost therapies that promote rehabilitation would be especially beneficial.

We contend that initiatives to transform dialysis outcomes for patients require both top-down efforts (for example, those that involve systems changes at the policy, regulatory, macroeconomic and organizational levels) and bottom-up efforts (for example, patient-led and patient-centred advocacy and individual teams of innovators). Top-down efforts are required to support, facilitate and de-risk the work of innovators. Conversely, patient-led advocacy is essential for influencing governmental and organizational policy change. Here, by considering how selected programmes are attempting to transform dialysis outcomes through innovation in support of high-value, high-quality care, we describe how top-down and bottom-up efforts can work synergistically to change the existing ecosystem of dialysis care (Fig. 2 ). The efforts described below are not an exhaustive list; rather, this discussion is intended to provide a representative overview of how the dialysis landscape is changing. Additional articles in this issue describe in more detail some of the bottom-up efforts of innovators to create wearable 124 , portable 125 , more environmentally friendly 126 and more physiological dialysis systems 127 , 128 , priorities from the patients’ perspective 129 , and the role of regulators in supporting innovation in the dialysis space 130 .

Initiatives to transform dialysis outcomes for patients require both top-down efforts (for example, those that involve systems-level changes at the policy, regulatory, macroeconomic and organizational level) and bottom-up efforts (for example, patient-led and patient-centred advocacy efforts and efforts from individual teams of innovators). Both of these efforts need to be guided by priorities identified by patients. Such an approach, focused on patient-centred innovation, has the potential to result in meaningful innovations that support high-quality, high-value care. NGOs, non-governmental organizations.

The Kidney Health Initiative