Research Methods in Developmental Psychology

Angela Lukowski and Helen Milojevich

Learning Objectives

- Describe different research methods used to study infant and child development

- Discuss different research designs, as well as their strengths and limitations

- Report on the unique challenges associated with conducting developmental research

Introduction

A group of children were playing hide-and-seek in the yard. Pilar raced to her hiding spot as her six-year-old cousin, Lucas, loudly counted, “… six, seven, eight, nine, ten! Ready or not, here I come!”. Pilar let out a small giggle as Lucas ran over to find her – in the exact location where he had found his sister a short time before. At first glance, this behavior is puzzling: why would Pilar hide in exactly the same location where someone else was just found? Whereas older children and adults realize that it is likely best to hide in locations that have not been searched previously, young children do not have the same cognitive sophistication. But why not… and when do these abilities first develop?

Developmental psychologists investigate questions like these using research methods that are tailored to the particular capabilities of the infants and children being studied. Importantly, research in developmental psychology is more than simply examining how children behave during games of hide-and-seek – the results obtained from developmental research have been used to inform best practices in parenting, education, and policy.

This module describes different research techniques that are used to study psychological phenomena in infants and children, research designs that are used to examine age-related changes in developmental processes and changes over time, and unique challenges and special issues associated with conducting research with infants and children.

Research Methods

Infants and children—especially younger children—cannot be studied using the same research methods used in studies with adults. Researchers, therefore, have developed many creative ways to collect information about infant and child development. In this section, we highlight some of the methods that have been used by researchers who study infants and older children, separating them into three distinct categories: involuntary or obligatory responses , voluntary responses , and psychophysiological responses . We will also discuss other methods such as the use of surveys and questionnaires. At the end of this section, we give an example of how interview techniques can be used to study the beliefs and perceptions of older children and adults – a method that cannot be used with infants or very young children.

Involuntary or obligatory responses

One of the primary challenges in studying very young infants is that they have limited motor control – they cannot hold their heads up for short amounts of time, much less grab an interesting toy, play the piano, or turn a door knob. As a result, infants cannot actively engage with the environment in the same way as older children and adults. For this reason, developmental scientists have designed research methods that assess involuntary or obligatory responses. These are behaviors in which people engage without much conscious thought or effort. For example, think about the last time you heard your name at a party – you likely turned your head to see who was talking without even thinking about it. Infants and young children also demonstrate involuntary responses to stimuli in the environment. When infants hear the voice of their mother, for instance, their heart rate increases – whereas if they hear the voice of a stranger, their heart rate decreases (Kisilevsky et al., 2003). Researchers study involuntary behaviors to better understand what infants know about the world around them.

One research method that capitalizes on involuntary or obligatory responses is a procedure known as habituation . In habituation studies, infants are presented with a stimulus such as a photograph of a face over and over again until they become bored with it. When infants become bored, they look away from the picture. If infants are then shown a new picture–such as a photograph of a different face– their interest returns and they look at the new picture. This is a phenomenon known as dishabituation . Habituation procedures work because infants generally look longer at novel stimuli relative to items that are familiar to them. This research technique takes advantage of involuntary or obligatory responses because infants are constantly looking around and observing their environments; they do not have to be taught to engage with the world in this way.

One classic habituation study was conducted by Baillargeon and colleagues (1985). These researchers were interested in the concept of object permanence , or the understanding that objects exist even when they cannot be seen or heard. For example, you know your toothbrush exists even though you are probably not able to see it right this second. To investigate object permanence in 5-month-old infants, the researchers used a violation of expectation paradigm . The researchers first habituated infants to an opaque screen that moved back and forth like a drawbridge (using the same procedure you just learned about in the previous paragraph). Once the infants were bored with the moving screen, they were shown two different scenarios to test their understanding of physical events. In both of these test scenarios, an opaque box was placed behind the moving screen. What differed between these two scenarios, however, was whether they confirmed or violated the solidity principle – the idea that two solid objects cannot occupy the same space at the same time. In the possible scenario, infants watched as the moving drawbridge stopped when it hit the opaque box (as would be expected based on the solidity principle). In the impossible scenario, the drawbridge appeared to move right through the space that was occupied by the opaque box! This impossible scenario violates the solidity principle in the same way as if you got out of your chair and walked through a wall, reappearing on the other side.

The results of this study revealed that infants looked longer at the impossible test event than at the possible test event. The authors suggested that the infants reacted in this way because they were surprised – the demonstration went against their expectation that two solids cannot move through one another. The findings indicated that 5-month-old infants understood that the box continued to exist even when they could not see it. Subsequent studies indicated that 3½- and 4½-month-old infants also demonstrate object permanence under similar test conditions (Baillargeon, 1987). These findings are notable because they suggest that infants understand object permanence much earlier than had been reported previously in research examining voluntary responses (although see more recent research by Cashon & Cohen, 2000).

Voluntary responses

As infants and children age, researchers are increasingly able to study their understanding of the world through their voluntary responses. Voluntary responses are behaviors that a person completes by choice. For example, think about how you act when you go to the grocery store: you select whether to use a shopping cart or a basket, you decide which sections of the store to walk through, and you choose whether to stick to your grocery list or splurge on a treat. Importantly, these behaviors are completely up to you (and are under your control). Although they do not do a lot of grocery shopping, infants and children also have voluntary control over their actions. Children, for instance, choose which toys to play with.

Researchers study the voluntary responses of infants and young children in many ways. For example, developmental scientists study recall memory in infants and young children by looking at voluntary responses. Recall memory is memory of past events or episodes, such as what you did yesterday afternoon or on your last birthday. Whereas older children and adults are simply asked to talk about their past experiences, recall memory has to be studied in a different way in infants and very young children who cannot discuss the past using language. To study memory in these subjects researchers use a behavioral method known as e licited imitation (Lukowski & Milojevich, in press).

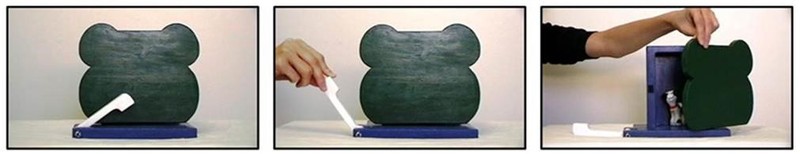

In the elicited imitation procedure, infants play with toys that are designed in the lab to be unlike the kinds of things infants usually have at home. These toys (or event sequences, as researchers call them) can be put together in a certain way to produce an outcome that infants commonly enjoy. One of these events is called Find the Surprise. As shown in Figure 1, this toy has a door on the front that is held in place by a latch – and a small plastic figure is hidden on the inside. During the first part of the study, infants play with the toy in whichever way they want for a few minutes. The researcher then shows the infant how make the toy work by (1) flipping the latch out of the way and (2) opening the door, revealing the plastic toy inside. The infant is allowed to play with the toy again either immediately after the demonstration or after a longer delay. As the infant plays, the researcher records whether the infant finds the surprise using the same procedure that was demonstrated.

Use of the elicited imitation procedure has taught developmental scientists a lot about how recall memory develops. For example, we now know that 6-month-old infants remember one step of a 3-step sequence for 24 hours (Barr, Dowden, & Hayne, 1996; Collie & Hayne, 1999). Nine-month-olds remember the individual steps that make up a 2-step event sequence for 1 month, but only 50% of infants remember to do the first step of the sequence before the second (Bauer, Wiebe, Carver, Waters, & Nelson, 2003; Bauer, Wiebe, Waters, & Bangston, 2001; Carver & Bauer, 1999). When children are 20 months old, they remember the individual steps and temporal order of 4-step events for at least 12 months – the longest delay that has been tested to date (Bauer, Wenner, Dropik, & Wewerka, 2000).

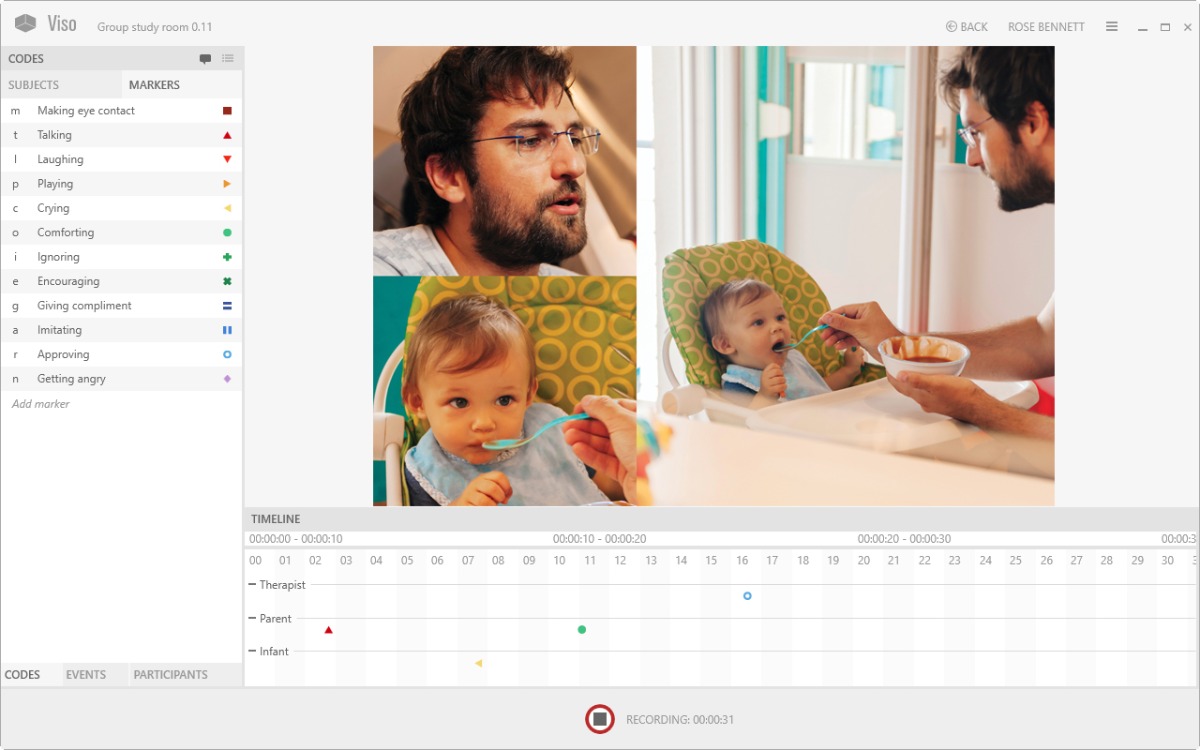

Psychophysiology

Behavioral studies have taught us important information about what infants and children know about the world. Research on behavior alone, however, cannot tell scientists how brain development or biological changes impact (or are impacted by) behavior. For this reason, researchers may also record psychophysiological data, such as measures of heart rate, hormone levels, or brain activity. These measures may be recorded by themselves or in combination with behavioral data to better understand the bidirectional relations between biology and behavior.

One manner of understanding associations between brain development and behavioral advances is through the recording of event-related potentials , or ERPs. ERPs are recorded by fitting a research participant with a stretchy cap that contains many small sensors or electrodes. These electrodes record tiny electrical currents on the scalp of the participant in response to the presentation of particular stimuli, such as a picture or a sound (for additional information on recording ERPs from infants and children, see DeBoer, Scott, & Nelson, 2005). The recorded responses are then amplified thousands of times using specialized equipment so that they look like squiggly lines with peaks and valleys. Some of these brain responses have been linked to psychological phenomena. For example, researchers have identified a negative peak in the recorded waveform that they have called the N170 (Bentin, Allison, Puce, Perez, & McCarthy, 2010). The peak is named in this way because it is negative (hence the N) and because it occurs about 140ms to 170ms after a stimulus is presented (hence the 170). This peak is particularly sensitive to the presentation of faces, as it is commonly more negative when participants are presented with photographs of faces rather than with photographs of objects. In this way, researchers are able to identify brain activity associated with real world thinking and behavior.

The use of ERPs has provided important insight as to how infants and children understand the world around them. In one study (Webb, Dawson, Bernier, & Panagiotides, 2006), researchers examined face and object processing in children with autism spectrum disorders, those with developmental delays, and those who were typically developing. The children wore electrode caps and had their brain activity recorded as they watched still photographs of faces (of their mother or of a stranger) and objects (including those that were familiar or unfamiliar to them). The researchers examined differences in face and object processing by group by observing a component of the brainwave they called the prN170 (because it was believed to be a precursor to the adult N170). Their results showed that the height of the prN170 peak (commonly called the amplitude ) did not differ when faces or objects were presented to typically developing children. When considering children with autism, however, the peaks were higher when objects were presented relative to when faces were shown. Differences were also found in how long it took the brain to reach the negative peak (commonly called the latency of the response). Whereas the peak was reached more quickly when typically developing children were presented with faces relative to objects, the opposite was true for children with autism. These findings suggest that children with autism are in some way processing faces differently than typically developing children (and, as reported in the manuscript, children with more general developmental delays).

Parent-report questionnaires

Developmental science has come a long way in assessing various aspects of infant and child development through behavior and psychophysiology – and new advances are happening every day. In many ways, however, the very youngest of research participants are still quite limited in the information they can provide about their own development. As such, researchers often ask the people who know infants and children best – commonly, their parents or guardians – to complete surveys or questionnaires about various aspects of their lives. These parent-report data can be analyzed by themselves or in combination with any collected behavioral or psychophysiological data.

One commonly used parent-report questionnaire is the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). Parents complete the preschooler version of this questionnaire by answering questions about child strengths, behavior problems, and disabilities, among other things. The responses provided by parents are used to identify whether the child has any behavioral issues, such as sleep difficulties, aggressive behaviors, depression, or attention deficit/hyperactivity problems.

A recent study used the CBCL-Preschool questionnaire (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) to examine preschooler functioning in relation to levels of stress experienced by their mothers while they were pregnant (Ronald, Pennell, & Whitehouse, 2011). Almost 3,000 pregnant women were recruited into the study during their pregnancy and were interviewed about their stressful life experiences. Later, when their children were 2 years old, mothers completed the CBCL-Preschool questionnaire. The results of the study showed that higher levels of maternal stress during pregnancy (such as a divorce or moving to a new house) were associated with increased attention deficit/hyperactivity problems in children over 2 years later. These findings suggest that stressful events experienced during prenatal development may be associated with problematic child behavioral functioning years later – although additional research is needed.

Interview techniques

Whereas infants and very young children are unable to talk about their own thoughts and behaviors, older children and adults are commonly asked to use language to discuss their thoughts and knowledge about the world. In fact, these verbal report paradigms are among the most widely used in psychological research. For instance, a researcher might present a child with a vignette or short story describing a moral dilemma, and the child would be asked to give their own thoughts and beliefs (Walrath, 2011). For example, children might react to the following:

“Mr. Kohut’s wife is sick and only one medication can save her life. The medicine is extremely expensive and Mr. Kohut cannot afford it. The druggist will not lower the price. What should Mr. Kohut do, and why?”

Children can provide written or verbal answers to these types of scenarios. They can also offer their perspectives on issues ranging from attitudes towards drug use to the experience of fear while falling asleep to their memories of getting lost in public places – the possibilities are endless. Verbal reports such as interviews and surveys allow children to describe their own experience of the world.

Research Design

Now you know about some tools used to conduct research with infants and young children. Remember, research methods are the tools that are used to collect information. But it is easy to confuse research methods and research design . Research design is the strategy or blueprint for deciding how to collect and analyze information. Research design dictates which methods are used and how.

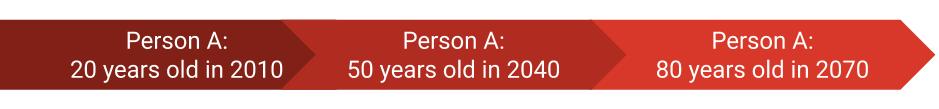

Researchers typically focus on two distinct types of comparisons when conducting research with infants and children. The first kind of comparison examines change within individuals . As the name suggests, this type of analysis measures the ways in which a specific person changes (or remains the same) over time. For example, a developmental scientist might be interested in studying the same group of infants at 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months to examine how vocabulary and grammar change over time. This kind of question would be best answered using a longitudinal research design. Another sort of comparison focuses on changes between groups . In this type of analysis, researchers study average changes in behavior between groups of different ages. Returning to the language example, a scientist might study the vocabulary and grammar used by 12-month-olds, 18-month-olds, and 24-month-olds to examine how language abilities change with age. This kind of question would be best answered using a cross-sectional research design.

Longitudinal research designs

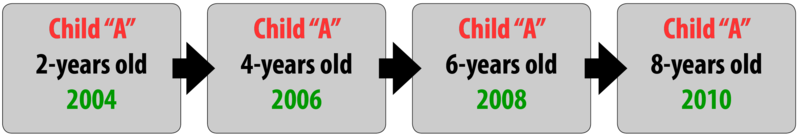

Longitudinal research designs are used to examine behavior in the same infants and children over time. For example, when considering our example of hide-and-seek behaviors in preschoolers, a researcher might conduct a longitudinal study to examine whether 2-year-olds develop into better hiders over time. To this end, a researcher might observe a group of 2-year-old children playing hide-and-seek with plans to observe them again when they are 4 years old – and again when they are 6 years old. This study is longitudinal in nature because the researcher plans to study the same children as they age. Based on her data, the researcher might conclude that 2-year-olds develop more mature hiding abilities with age. Remember, researchers examine games such as hide-and-seek not because they are interested in the games themselves, but because they offer clues to how children think, feel and behave at various ages.

Longitudinal studies may be conducted over the short term (over a span of months, as in Wiebe, Lukowski, & Bauer, 2010) or over much longer durations (years or decades, as in Lukowski et al., 2010). For these reasons, longitudinal research designs are optimal for studying stability and change over time. Longitudinal research also has limitations, however. For one, longitudinal studies are expensive: they require that researchers maintain continued contact with participants over time, and they necessitate that scientists have funding to conduct their work over extended durations (from infancy to when participants were 19 years old in Lukowski et al., 2010). An additional risk is attrition . Attrition occurs when participants fail to complete all portions of a study. Participants may move, change their phone numbers, or simply become disinterested in participating over time. Researchers should account for the possibility of attrition by enrolling a larger sample into their study initially, as some participants will likely drop out over time.

The results from longitudinal studies may also be impacted by repeated assessments. Consider how well you would do on a math test if you were given the exact same exam every day for a week. Your performance would likely improve over time not necessarily because you developed better math abilities, but because you were continuously practicing the same math problems. This phenomenon is known as a practice effect . Practice effects occur when participants become better at a task over time because they have done it again and again; not due to natural psychological development. A final limitation of longitudinal research is that the results may be impacted by cohort effects . Cohort effects occur when the results of the study are affected by the particular point in historical time during which participants are tested. As an example, think about how peer relationships in childhood have likely changed since February 2004 – the month and year Facebook was founded. Cohort effects can be problematic in longitudinal research because only one group of participants are tested at one point in time – different findings might be expected if participants of the same ages were tested at different points in historical time.

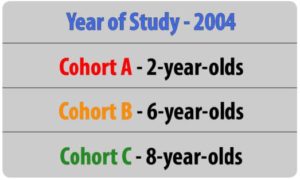

Cross-sectional designs

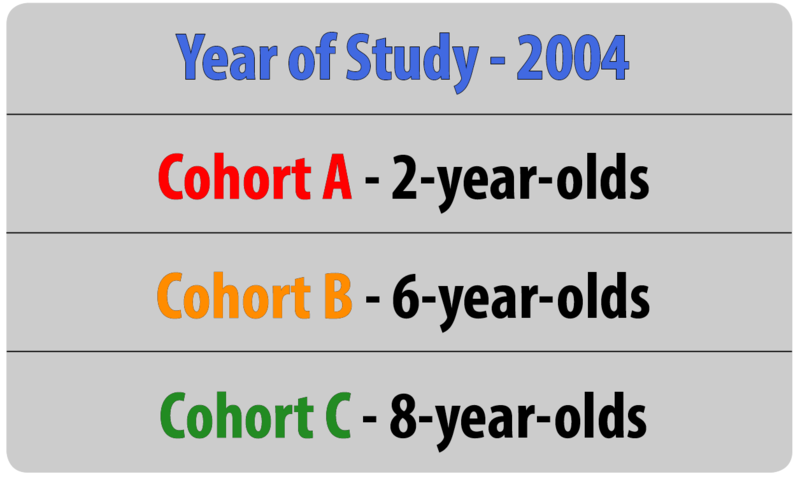

Cross-sectional research designs are used to examine behavior in participants of different ages who are tested at the same point in time. When considering our example of hide-and-seek behaviors in children, for example, a researcher might want to examine whether older children more often hide in novel locations (those in which another child in the same game has never hidden before) when compared to younger children. In this case, the researcher might observe 2-, 4-, and 6-year-old children as they play the game (the various age groups represent the “cross sections”). This research is cross-sectional in nature because the researcher plans to examine the behavior of children of different ages within the same study at the same time. Based on her data, the researcher might conclude that 2-year-olds more commonly hide in previously-searched locations relative to 6-year-olds.

Cross-sectional designs are useful for many reasons. Because participants of different ages are tested at the same point in time, data collection can proceed at a rapid pace. In addition, because participants are only tested at one point in time, practice effects are not an issue – children do not have the opportunity to become better at the task over time. Cross-sectional designs are also more cost-effective than longitudinal research designs because there is no need to maintain contact with and follow-up on participants over time.

One of the primary limitations of cross-sectional research, however, is that the results yield information on age-related change, not development per se . That is, although the study described above can show that 6-year-olds are more advanced in their hiding behavior than 2-year-olds, the data used to come up with this conclusion were collected from different children. It could be, for instance, that this specific sample of 6-year-olds just happened to be particularly clever at hide-and-seek. As such, the researcher cannot conclude that 2-year-olds develop into better hiders with age; she can only state that 6-year-olds, on average, are more sophisticated hiders relative to children 4 years younger.

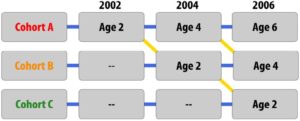

Sequential research designs

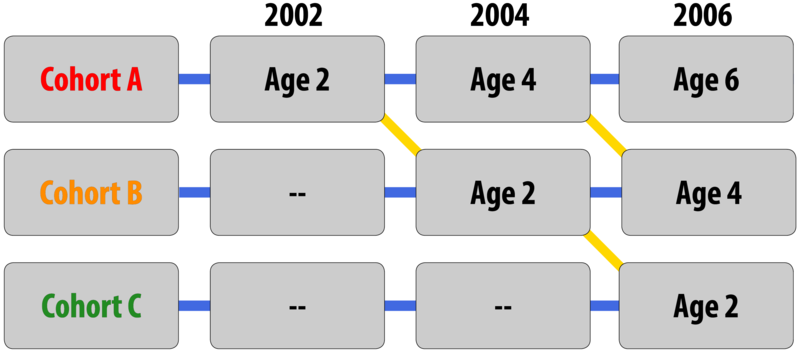

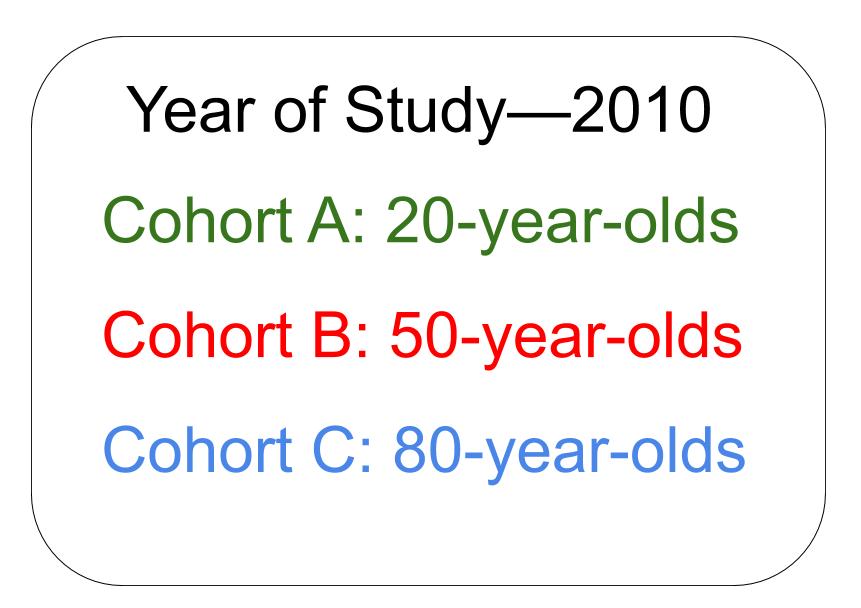

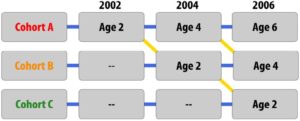

Sequential research designs include elements of both longitudinal and cross-sectional research designs. Similar to longitudinal designs, sequential research features participants who are followed over time; similar to cross-sectional designs, sequential work includes participants of different ages. This research design is also distinct from those that have been discussed previously in that children of different ages are enrolled into a study at various points in time to examine age-related changes, development within the same individuals as they age, and account for the possibility of cohort effects.

Consider, once again, our example of hide-and-seek behaviors. In a study with a sequential design, a researcher might enroll three separate groups of children (Groups A, B, and C). Children in Group A would be enrolled when they are 2 years old and would be tested again when they are 4 and 6 years old (similar in design to the longitudinal study described previously). Children in Group B would be enrolled when they are 4 years old and would be tested again when they are 6 and 8 years old. Finally, children in Group C would be enrolled when they are 6 years old and would be tested again when they are 8 and 10 years old.

Studies with sequential designs are powerful because they allow for both longitudinal and cross-sectional comparisons. This research design also allows for the examination of cohort effects. For example, the researcher could examine the hide-and-seek behavior of 6-year-olds in Groups A, B, and C to determine whether performance differed by group when participants were the same age. If performance differences were found, there would be evidence for a cohort effect. In the hide-and-seek example, this might mean that children from different time periods varied in the amount they giggled or how patient they are when waiting to be found. Sequential designs are also appealing because they allow researchers to learn a lot about development in a relatively short amount of time. In the previous example, a four-year research study would provide information about 8 years of developmental time by enrolling children ranging in age from two to ten years old.

Because they include elements of longitudinal and cross-sectional designs, sequential research has many of the same strengths and limitations as these other approaches. For example, sequential work may require less time and effort than longitudinal research, but more time and effort than cross-sectional research. Although practice effects may be an issue if participants are asked to complete the same tasks or assessments over time, attrition may be less problematic than what is commonly experienced in longitudinal research since participants may not have to remain involved in the study for such a long period of time.

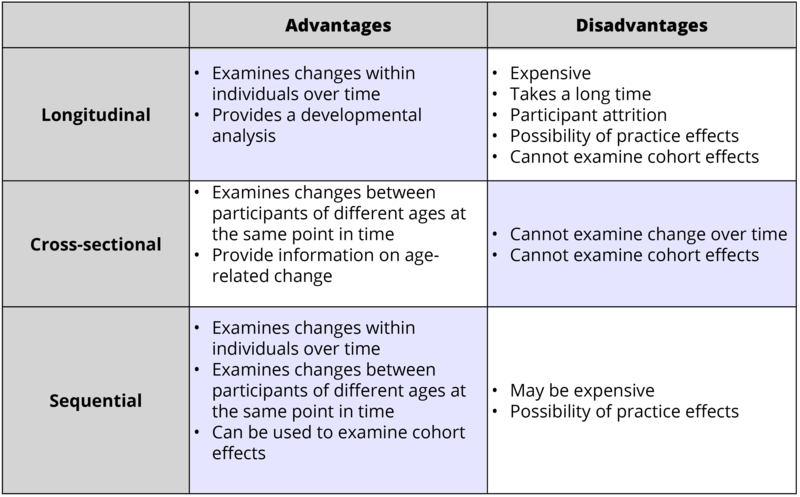

When considering the best research design to use in their research, scientists think about their main research question and the best way to come up with an answer. A table of advantages and disadvantages for each of the described research designs is provided here to help you as you consider what sorts of studies would be best conducted using each of these different approaches.

Challenges Associated with Conducting Developmental Research

The previous sections describe research tools to assess development in infancy and early childhood, as well as the ways that research designs can be used to track age-related changes and development over time. Before you begin conducting developmental research, however, you must also be aware that testing infants and children comes with its own unique set of challenges. In the final section of this module, we review some of the main issues that are encountered when conducting research with the youngest of human participants. In particular, we focus our discussion on ethical concerns, recruitment issues, and participant attrition.

Ethical concerns

As a student of psychological science, you may already know that Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) review and approve of all research projects that are conducted at universities, hospitals, and other institutions. An IRB is typically a panel of experts who read and evaluate proposals for research. IRB members want to ensure that the proposed research will be carried out ethically and that the potential benefits of the research outweigh the risks and harm for participants. What you may not know though, is that the IRB considers some groups of participants to be more vulnerable or at-risk than others. Whereas university students are generally not viewed as vulnerable or at-risk, infants and young children commonly fall into this category. What makes infants and young children more vulnerable during research than young adults? One reason infants and young children are perceived as being at increased risk is due to their limited cognitive capabilities, which makes them unable to state their willingness to participate in research or tell researchers when they would like to drop out of a study. For these reasons, infants and young children require special accommodations as they participate in the research process.

When thinking about special accommodations in developmental research, consider the informed consent process. If you have ever participated in psychological research, you may know through your own experience that adults commonly sign an informed consent statement (a contract stating that they agree to participate in research) after learning about a study. As part of this process, participants are informed of the procedures to be used in the research, along with any expected risks or benefits. Infants and young children cannot verbally indicate their willingness to participate, much less understand the balance of potential risks and benefits. As such, researchers are oftentimes required to obtain written informed consent from the parent or legal guardian of the child participant, an adult who is almost always present as the study is conducted. In fact, children are not asked to indicate whether they would like to be involved in a study at all (a process known as assent ) until they are approximately seven years old. Because infants and young children also cannot easily indicate if they would like to discontinue their participation in a study, researchers must be sensitive to changes in the state of the participant (determining whether a child is too tired or upset to continue) as well as to parent desires (in some cases, parents might want to discontinue their involvement in the research). As in adult studies, researchers must always strive to protect the rights and well-being of the minor participants and their parents when conducting developmental science.

Recruitment

An additional challenge in developmental science is participant recruitment. Recruiting university students to participate in adult studies is typically easy. Many colleges and universities offer extra credit for participation in research and have locations such as bulletin boards and school newspapers where research can be advertised. Unfortunately, young children cannot be recruited by making announcements in Introduction to Psychology courses, by posting ads on campuses, or through online platforms such as Amazon Mechanical Turk . Given these limitations, how do researchers go about finding infants and young children to be in their studies?

The answer to this question varies along multiple dimensions. Researchers must consider the number of participants they need and the financial resources available to them, among other things. Location may also be an important consideration. Researchers who need large numbers of infants and children may attempt to do so by obtaining infant birth records from the state, county, or province in which they reside. Some areas make this information publicly available for free, whereas birth records must be purchased in other areas (and in some locations birth records may be entirely unavailable as a recruitment tool). If birth records are available, researchers can use the obtained information to call families by phone or mail them letters describing possible research opportunities. All is not lost if this recruitment strategy is unavailable, however. Researchers can choose to pay a recruitment agency to contact and recruit families for them. Although these methods tend to be quick and effective, they can also be quite expensive. More economical recruitment options include posting advertisements and fliers in locations frequented by families, such as mommy-and-me classes, local malls, and preschools or day care centers. Researchers can also utilize online social media outlets like Facebook, which allows users to post recruitment advertisements for a small fee. Of course, each of these different recruitment techniques requires IRB approval.

Another important consideration when conducting research with infants and young children is attrition . Although attrition is quite common in longitudinal research in particular, it is also problematic in developmental science more generally, as studies with infants and young children tend to have higher attrition rates than studies with adults. For example, high attrition rates in ERP studies oftentimes result from the demands of the task: infants are required to sit still and have a tight, wet cap placed on their heads before watching still photographs on a computer screen in a dark, quiet room. In other cases, attrition may be due to motivation (or a lack thereof). Whereas adults may be motivated to participate in research in order to receive money or extra course credit, infants and young children are not as easily enticed. In addition, infants and young children are more likely to tire easily, become fussy, and lose interest in the study procedures than are adults. For these reasons, research studies should be designed to be as short as possible – it is likely better to break up a large study into multiple short sessions rather than cram all of the tasks into one long visit to the lab. Researchers should also allow time for breaks in their study protocols so that infants can rest or have snacks as needed. Happy, comfortable participants provide the best data.

Conclusions

Child development is a fascinating field of study – but care must be taken to ensure that researchers use appropriate methods to examine infant and child behavior, use the correct experimental design to answer their questions, and be aware of the special challenges that are part-and-parcel of developmental research. After reading this module, you should have a solid understanding of these various issues and be ready to think more critically about research questions that interest you. For example, when considering our initial example of hide-and-seek behaviors in preschoolers, you might ask questions about what other factors might contribute to hiding behaviors in children. Do children with older siblings hide in locations that were previously searched less often than children without siblings? What other abilities are associated with the development of hiding skills? Do children who use more sophisticated hiding strategies as preschoolers do better on other tests of cognitive functioning in high school? Many interesting questions remain to be examined by future generations of developmental scientists – maybe you will make one of the next big discoveries!

Discussion Questions

- Why is it important to conduct research on infants and children?

- What are some possible benefits and limitations of the various research methods discussed in this module?

- Why is it important to examine cohort effects in developmental research?

- Think about additional challenges or unique issues that might be experienced by developmental scientists. How would they handle the challenges and issues you’ve addressed?

- Work with your peers to design a study to identify whether children who were good hiders as preschoolers are more cognitively advanced in high school. What research design would you use and why? What are the advantages and limitations of the design you selected?

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Baillargeon, R. (1987). Object permanence in 3½- and 4½-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology, 23, 655-664. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.655

Baillargeon, R., Spelke, E., & Wasserman, S. (1985). Object permanence in five-month-old infants. Cognition, 20, 191-208. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(85)90008-3

Barr, R., Dowden, A., & Hayne, H. (1996). Developmental changes in deferred imitation by 6- to 24-month-old infants. Infant Behavior and Development, 19 , 159-170. doi: 10.1016/s0163-6383(96)90015-6

Bauer, P. J., Wenner, J. A., Dropik, P. L., & Wewerka, S. S. (2000). Parameters of remembering and forgetting in the transition from infancy to early childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 65 , 1-204. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.04.001

Bauer, P. J., Wiebe, S. A., Carver, L. J., Waters, J. M., & Nelson, C. A. (2003). Developments in long-term explicit memory late in the first year of life: Behavioral and electrophysiological indices. Psychological Science, 14 , 629-635. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1476.x

Bauer, P. J., Wiebe, S. A., Waters, J. M., & Bangston, S. K. (2001). Reexposure breeds recall: Effects of experience on 9-month-olds’ ordered recall. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 80 , 174-200. doi: 10.1006/jecp.2000.2628

Bentin, S., Allison, T., Puce, A., Perez, E., & McCarthy, G. (2010). Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience , 8, 551-565. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1996.8.6.551

Carver, L. J., & Bauer, P. J. (1999). When the event is more than the sum of its parts: 9-month-olds’ long-term ordered recall. Memory, 7 , 147-174. doi: 10.1080/741944070

Cashon, C. H., & Cohen, L. B. (2000). Eight-month-old infants’ perception of possible and impossible events. Infancy, 1 , 429-446. doi: 10.1016/s0163-6383(98)91561-2

Collie, R., & Hayne, H. (1999). Deferred imitation by 6- and 9-month-old infants: More evidence for declarative memory. Developmental Psychobiology, 35 , 83-90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199909)35:2<83::aid-dev1>3.0.co;2-s

DeBoer, T., Scott, L. S., & Nelson, C. A. (2005). ERPs in developmental populations. In T. C. Handy (Ed.), Event-related potentials: A methods handbook (pp. 263-297) . Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Lukowski, A. F., & Milojevich, H. M. (2016). Examining recall memory in infancy and early childhood using the elicited imitation paradigm. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 110 , e53347.

Lukowski, A. F., Koss, M., Burden, M. J., Jonides, J., Nelson, C. A., Kaciroti, N., … Lozoff, B. (2010). Iron deficiency in infancy and neurocognitive functioning at 19 years: Evidence of long-term deficits in executive function and recognition memory. Nutritional Neuroscience, 13 , 54-70. doi: 10.1179/147683010×12611460763689

Ronald, A., Pennell, C. E., & Whitehouse, A. J. O. (2011). Prenatal maternal stress associated with ADHD and autistic traits in early childhood. Frontiers in Psychology, 1 , 1-8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00223

Walrath, R. (2011). Kohlberg’s theory of moral development. In Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development (pp. 859–860).

Webb, S. J., Dawson, G., Bernier, R., & Panagiotides, H. (2006). ERP evidence of atypical face processing in young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36 , 884-890. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0126-x

Wiebe, S. A., Lukowski, A. F., & Bauer, P. J. (2010). Sequence imitation and reaching measures of executive control: A longitudinal examination in the second year of life. Developmental Neuropsychology, 35 , 522-538. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2010.494751

attribution

Research Methods in Developmental Psychology by Angela Lukowski and Helen Milojevich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Behaviors in which individuals engage that do not require much conscious thought or effort.

Behaviors that a person has control over and completes by choice.

Recording of biological measures (such as heart rate and hormone levels) and neurological responses (such as brain activity) that may be associated with observable behaviors.

A research method in which participants are asked to report on their experiences using language, commonly by engaging in conversation with a researcher (participants may also be asked to record their responses in writing).

The use of thinking to direct muscles and limbs to perform a desired action.

When participants demonstrated decreased attention (through looking or listening behavior) to repeatedly-presented stimuli.

When participants demonstrated increased attention (through looking or listening behavior) to a new stimulus after having been habituated to a different stimulus.

The understanding that objects continue to exist even when they cannot be directly observed (e.g., that a pen continues to exist even when it is hidden under a piece of paper).

A research method in which infants are expected to respond in a particular way because one of two conditions violates or goes against what they should expect based on their everyday experiences (e.g., it violates our expectations that Wile E. Coyote runs off a cliff but does not immediately fall to the ground below).

The idea that two solid masses should not be able to move through one another.

The process of remembering discrete episodes or events from the past, including encoding, consolidation and storage, and retrieval.

A behavioral method used to examine recall memory in infants and young children.

When one variable is likely both cause and consequence of another variable.

The recording of participant brain activity using a stretchy cap with small electrodes or sensors as participants engage in a particular task (commonly viewing photographs or listening to auditory stimuli).

Research methods that require participants to report on their experiences, thoughts, feelings, etc., using language.

A short story that presents a situation that participants are asked to respond to.

The specific tools and techniques used by researchers to collect information.

The strategy (or “blueprint”) for deciding how to collect and analyze research information.

A research design used to examine behavior in the same participants over short (months) or long (decades) periods of time.

A research design used to examine behavior in participants of different ages who are tested at the same point in time.

When a participant drops out, or fails to complete, all parts of a study.

When participants get better at a task over time by “practicing” it through repeated assessments instead of due to actual developmental change (practice effects can be particularly problematic in longitudinal and sequential research designs).

When research findings differ for participants of the same age tested at different points in historical time.

A research design that includes elements of cross-sectional and longitudinal research designs. Similar to cross-sectional designs, sequential research designs include participants of different ages within one study; similar to longitudinal designs, participants of different ages are followed over time.

A committee that reviews and approves research procedures involving human participants and animal subjects to ensure that the research is conducted in accordance with federal, institutional, and ethical guidelines.

The process of getting permission from adults for themselves and their children to take part in research.

When minor participants are asked to indicate their willingness to participate in a study. This is usually obtained from participants who are at least 7 years old, in addition to parent or guardian consent.

Research Methods in Developmental Psychology Copyright © by Angela Lukowski and Helen Milojevich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Utility Menu

Department of Psychology

- https://twitter.com/PsychHarvard

- https://www.facebook.com/HarvardPsychology/

- https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCFBv7eBJIQWCrdxPRhYft9Q

- Participate

- Developmental Psychology

At Harvard's Laboratory for Developmental Studies , faculty and students seek to shed light on the human mind and human nature by studying their origins and development in infants and children, in relation to the mental capacities of non-human animals and of human adults in diverse cultures. Current research interests include studies of the nature and development of knowledge of objects, persons, language, music, space, number, morality, and the social categories that distinguish some human groups from others.

- Clinical Science

- Cognition, Brain, & Behavior

- Social Psychology

Developmental Psychology Faculty

- Elika Bergelson

- Susan E. Carey

- Joe Henrich

- Steven Pinker

- Jesse Snedeker

- Elizabeth S. Spelke

- Ashley Thomas

Developmental Psychology

- Living reference work entry

- Latest version View entry history

- First Online: 06 October 2022

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Moritz M. Daum ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4032-4574 5 , 6 &

- Mirella Manfredi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6549-1993 5

Part of the book series: Springer International Handbooks of Education ((SIHE))

92 Accesses

Developmental Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior from the perspective of change across the entire lifespan. In the present chapter, we provide a comprehensive and modern view on current topics particularly relevant when teaching Developmental Psychology. We start with the attempt to derive a contemporary definition of development and Developmental Psychology. Over historical time, perspectives on development changed. These different perspectives were regularly challenged, and we discuss some of the questions of scientific dispute such as the influence of nature and nurture on the development of an individual from a contemporary perspective. The perspectives often resulted in larger theoretical constructs. We will not describe individual theories comprehensively but rather focus on general issues of theoretical approaches and highlight one recent approach, the dynamic systems theories. Theories need to be supported by empirical evidence. Accordingly, we will briefly describe the major research designs used to measure developmental change. We will conclude the chapter with a focus on one topic particularly relevant when teaching Developmental Psychology, the development of communication, and discuss further topics that can potentially be included in a Developmental Psychology curriculum and describe some ideas on how to teach them. In all, we intend to provide a contemporary overview of the scientific study of developmental change.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Acredolo, L. P., & Goodwyn, S. W. (1990). Sign language among hearing infants: The spontaneous development of symbolic gestures. Springer Series in Language and Communication , 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-74859-2_7

Adolph, K. E., Young, J. W., Robinson, S. R., & Gill-Alvarez, F. (2008). What is the shape of developmental change? Psychological Review, 115 (3), 527–543. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.115.3.527

Article Google Scholar

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1 (2), 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x

Baltes, P. B. (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23 (5), 611–626. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.611

Baron-Cohen, S. (1989). Perceptual role taking and protodeclarative pointing in autism. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 7 (2), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835x.1989.tb00793.x

Baron-Cohen, S. (1995). Mindblindness: An essay on autism and theory of mind . Cambridge, MH: MIT Press.

Book Google Scholar

Baroni, M. R., & Axia, G. (1989). Children’s meta-pragmatic abilities and the identification of polite and impolite requests. First Language, 9 (27), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/014272378900902703

Batki, A., Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Connellan, J., & Ahluwalia, J. (2000). Is there an innate gaze module? Evidence from human neonates. Infant Behavior & Development, 23 (2), 223–229.

Bischof, N. (2020). Life Span an der Lahn. Psychologische Rundschau, 71 (1), 36–38.

Blake, J., & Boysson-Bardies, B. D. (1992). Patterns in babbling: A cross-linguistic study. Journal of Child Language, 19 (1), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000900013623

Bohannon, J. H., & Bonvillian, J. D. (1997). Theoretical approaches to language acquisition. The Development of Language, 4 , 259–316.

Google Scholar

Bowlby, J. (1999). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). Basic Books.

Brooks, R., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2002). The importance of eyes: How infants interpret adult looking behavior. Developmental Psychology, 38 (6), 958–966. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.6.958

Bruner, J. S. (1983). Play, thought, and language. Peabody Journal of Education, 60 (3), 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/01619568309538407

Bushneil, I. W. R., Sai, F., & Mullin, J. T. (1989). Neonatal recognition of the mother’s face. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 7 (1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-835X.1989.tb00784.x

Buskist, W. F., & Benassi, V. A. (Eds.). (2011). Effective college and university teaching: Strategies and tactics for the new professoriate (1st ed.). SAGE.

Callanan, M. A., & Sabbagh, M. A. (2004). Multiple labels for objects in conversations with young children: Parents’ language and children’s developing expectations about word meanings. Developmental Psychology, 40 (5), 746–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.746

Carlson, S. M., & Moses, L. J. (2001). Individual differences in inhibitory control and children’s theory of mind. Child Development, 72 (4), 1032–1053. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00333

Chalmers, D., & Fuller, R. (2012). Teaching for learning at university . Routledge.

Cooper, R. P., & Aslin, R. N. (1990). Preference for infant-directed speech in the first month after birth. Child Development, 61 (5), 1584–1595. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02885.x

Coyle, T. R., & Bjorklund, D. F. (1997). Age differences in, and consequences of, multiple and variable-strategy use on a multitrial sort-recall task. Developmental Psychology, 33 (2), 372–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.2.372

Daum, M. M., Greve, W., Pauen, S., Schuhrke, B., & Schwarzer, G. (2020). Positionspapier der Fachgruppe Entwicklungspsychologie: Versuch einer Standortbestimmung. Psychologische Rundschau, 71 (1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1026/0033-3042/a000465

Daum, M. M., & Manfredi, M. (2021). The history of developmental psychology. PsyArXiv . https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/s2ckp

Davis, B. L., & MacNeilage, P. F. (2000). An embodiment perspective on the acquisition of speech perception. Phonetica, 57 (2–4), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1159/000028476

Davis, H. L., & Pratt, C. (1995). The development of children’s theory of mind: The working memory explanation. Australian Journal of Psychology, 47 (1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049539508258765

Dunn, D., Halonen, J. S., & Smith, R. A. (2008). Teaching critical thinking in psychology a handbook of best practices . Wiley-Blackwell.

Erikson, E. H., & Erikson, J. M. (1998). The life cycle completed . W. W. Norton & Company.

Fantz, R. L. (1963). Pattern vision in newborn infants. Science, 140 (3564), 296–297. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.140.3564.296

Farroni, T., Massaccesi, S., Pividori, D., & Johnson, M. H. (2004). Gaze following in newborns. Infancy, 5 , 39–60.

Fernald, A., & Simon, T. (1984). Expanded intonation contours in mothers’ speech to newborns. Developmental Psychology, 20 (1), 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.20.1.104

Fischer, K. W., & van Geert, P. L. C. (2014). Dynamic development of brain and behavior. In Handbook of developmental systems theory and methodology (pp. 287–315). The Guilford Press.

Freud, S. (1930). Three contributions to the theory of sex: Authorized transl. By AA Brill. With introduction by James J. Putnam, and AA Brill . Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company.

Garton, A. F., & Pratt, C. (1990). Children’s pragmatic judgements of direct and indirect requests. First Language, 10 (28), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/014272379001002804

Gershkoff-Stowe, L., & Smith, L. B. (1997). A curvilinear trend in naming errors as a function of early vocabulary growth. Cognitive Psychology, 34 (1), 37–71. https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.1997.0664

Goldin-Meadow, S. (2000). Beyond words: The importance of gesture to researchers and learners. Child Development, 71 (1), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00138

Gray, K. (2017). How to map theory: Reliable methods are fruitless without rigorous theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617691949

Hamaker, E. L. (2012). Why researchers should think “within-person”: A paradigmatic rationale. In M. R. Mehl & T. S. Connor (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 43–61). Guilford.

Havighurst, R. J. (1972). Developmental tasks and education (3rd ed.). New York: David McKay Company.

Hood, B. M., Willen, J. D., & Driver, J. (1998). Adult’s eyes trigger shifts of visual attention in human infants. Psychological Science, 9 (2), 131–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00024

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology . Holt.

Katz, G. S., Cohn, J. F., & Moore, C. A. (1996). A combination of vocal f0 dynamic and summary features discriminates between three pragmatic categories of infant-directed speech. Child Development, 67 (1), 205. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131696

Kohlberg, L. (1973). Moral development . McGraw-Hill Films.

Kuhl, P. K. (2004). Early language acquisition: Cracking the speech code. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5 (11), 831–843. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1533

Lee, C. S., Kitamura, C., Burnham, D., & McAngus Todd, N. P. (2014). On the rhythm of infant- versus adultdirected speech in Australian English. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 136 (1), 357–365.

Leong, V., Kalashnikova, M., Burnham, D., & Goswami, U. (2017). The temporal modulation structure of infantdirected speech. Open Mind, 1 (2), 78–90.

Lindenberger, U. (2013, September 10). Lifespan psychology: Challenges for the future. 21. Tagung Fachgruppe Entwicklungspsychologie . Tagung der Fachgruppe Entwicklungspsychologie der DGPs, Saarbrücken.

Masataka, N. (1992). Pitch characteristics of Japanese maternal speech to infants. Journal of Child Language, 19 (2), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000900011399

McKee, C., & McDaniel, D. (2004). Multiple influences on children’s language performance. Journal of Child Language, 31 (2), 489–492. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000904006130

McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought . University of Chicago Press.

Meaney, M. J. (2001). Nature, nurture, and the disunity of knowledge. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 935 (1), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03470.x

Meaney, M. J. (2010). Epigenetics and the biological definition of gene × environment interactions. Child Development, 81 (1), 41–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01381.x

Munakata, Y., Snyder, H. R., & Chatham, C. H. (2012). Developing cognitive control: Three key transitions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21 (2), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412436807

Mundy, P., Block, J., Delgado, C., Pomares, Y., Van Hecke, A. V., & Parlade, M. V. (2007). Individual differences and the development of joint attention in infancy. Child Development, 78 (3), 938–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01042.x

Mundy, P., & Newell, L. (2007). Attention, joint attention, and social cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16 (5), 269–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00518.x

Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child . Basic Books.

Plomin, R., DeFries, J. C., Craig, I. W., & McGuffin, P. (2003). Behavioral genetics. In R. Plomin, J. C. DeFries, I. W. Craig, & P. McGuffin (Eds.), Behavioral genetics in the postgenomic era (pp. 3–16). American Psychological Association.

Chapter Google Scholar

Plomin, R., & Spinath, F. M. (2004). Intelligence: Genetics, genes, and genomics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86 (1), 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.112

Przyborski, A., & Wohlrab-Sahr, M. (2013). Qualitative Sozialforschung: Ein Arbeitsbuch . Walter de Gruyter.

Reinert, G. (1976). Grundzüge einer Geschichte der Human-Entwicklungspsychologie . Univ., Fachbereich I, Psychologie.

Reynolds, C. W. (1987). Flocks, herds and schools: A distributed behavioral model. ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics, 21 (4), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1145/37402.37406

Rheingold, H. L., & Adams, J. L. (1980). The significance of speech to newborns. Developmental Psychology, 16 (5), 397–403. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.16.5.397

Rosenthal, M. (1982). Vocal dialogues in the neonatal period. Developmental Psychology, 18 (1), 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.18.1.17

Ross, H. S., & Lollis, S. P. (1987). Communication within infant social games. Developmental Psychology, 23 (2), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.23.2.241

Schacter, D., Gilbert, D., Wegner, D., & Hood, B. M. (2011). Psychology: European edition . Macmillan International Higher Education.

Schaie, K. W. (2015). Cohort sequential designs (convergence analysis). In R. L. Cautin & S. O. Lilienfeld (Eds.), The encyclopedia of clinical psychology (pp. 1–6). American Cancer Society. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp098

Schneider, M., & Mustafić, M. (2015). Gute Hochschullehre: Eine evidenzbasierte Orientierungshilfe: Wie man Vorlesungen, Seminare und Projekte effektiv gestaltet . Springer-Verlag.

Schwarzer, G., & Walper, S. (2016). Entwicklungspsychologie. In Dorsch Lexikon der Psychologie . Verlag Hans Huber. https://m.portal.hogrefe.com/dorsch/gebiet/entwicklungspsychologie/ .

Shaffer, D. R., & Kipp, K. (2010). Developmental psychology: Childhood and adolescence (8th ed.). Wadsworth/Cengage Learning. http://thuvienso.vanlanguni.edu.vn/handle/Vanlang_TV/11689

Siegler, R. S. (2016). Continuity and change in the field of cognitive development and in the perspectives of one cognitive developmentalist. Child Development Perspectives, 10 (2), 128–133. https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cdep.12173 . https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12173

Siegler, R. S., & Jenkins, E. A. (2014). How children discover new strategies . Psychology Press.

Siegler, R. S., & Svetina, M. (2002). A microgenetic/cross-sectional study of matrix completion: Comparing short-term and long-term change. Child Development, 73 (3), 793–809. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00439

Smith, L. B., & Thelen, E. (2003). Development as a dynamic system. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7 (8), 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00156-6

Soderstrom, M. (2007). Beyond babytalk: Re-evaluating the nature and content of speech input to preverbal infants. Developmental Review, 27 (4), 501–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2007.06.002

Spencer, J. P., Thomas, S. C., & McClelland, J. L. (2009). Toward a unified theory of development: Connectionism and dynamic systems theory re-considered . Oxford University Press.

Striano, T., Chen, X., Cleveland, A., & Bradshaw, S. (2006). Joint attention social cues influence infant learning. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 3 (3), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620600879779

Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18 , 643–662.

Tarantino, N., Tully, E. C., Garcia, S. E., South, S., Iacono, W. G., & McGue, M. (2014). Genetic and environmental influences on affiliation with deviant peers during adolescence and early adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 50 (3), 663–673. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034345

Thelen, E., & Smith, L. B. (1996). A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action . MIT Press.

Thelen, E., & Smith, L. B. (2007). Dynamic systems theories. In Handbook of child psychology . American Cancer Society. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0106

Tomasello, M. (1995). Joint attention as social cognition. In C. Moore & P. J. Dunham (Eds.), Joint attention: Its origins and role in development (pp. 103–130). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Trautner, H. M. (2003). Allgemeine Entwicklungspsychologie . Kohlhammer Verlag.

Valenza, E., Simion, F., Cassia, V. M., & Umilta, C. (1996). Face preference at birth. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Human Perception and Performance, 22 (4), 892–903.

van Geert, P. L. C. (1994). Dynamic systems of development: Change between complexity and chaos (p. xii, 300). Harvester Wheatsheaf.

van Geert, P. L. C. (1998). A dynamic systems model of basic developmental mechanisms: Piaget, Vygotsky, and beyond. Psychological Review, 105 (4), 634–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.105.4.634-677

van Geert, P. L. C. (2017). Constructivist theories. In B. Hopkins, E. Geangu, & S. Linkenauger (Eds.), The Cambridge encyclopedia of child development (2nd ed., pp. 19–34). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316216491.005

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher mental processes . Harvard University Press.

Walton, G. E., Bower, N. J. A., & Bower, T. G. R. (1992). Recognition of familiar faces by newborns. Infant Behavior & Development, 15 (2), 269–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-6383(92)80027-R

Werker, J. F., & Hensch, T. K. (2015). Critical periods in speech perception: New directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 66 (1), 173–196. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015104

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Developmental Psychology: Infancy and Childhood, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Moritz M. Daum & Mirella Manfredi

Jacobs Center for Productive Youth Development, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Moritz M. Daum

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Moritz M. Daum .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Education, Univ of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria

Joerg Zumbach

Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, Bonita Springs, FL, USA

Douglas Bernstein

Psychology Learning & Instruction, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen, Germany

Susanne Narciss

DISUFF, University of Salerno, Salerno, Salerno, Italy

Giuseppina Marsico

Section Editor information

University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria

Department of Psychology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

Douglas A. Bernstein

Psychologie des Lehrens und Lernens, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Deutschland

Department of Human, Philosophic, and Education Sciences, University of Salerno, Salerno, Italy

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Daum, M.M., Manfredi, M. (2022). Developmental Psychology. In: Zumbach, J., Bernstein, D., Narciss, S., Marsico, G. (eds) International Handbook of Psychology Learning and Teaching. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26248-8_13-2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26248-8_13-2

Received : 19 July 2021

Accepted : 20 July 2021

Published : 06 October 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-26248-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-26248-8

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

Chapter history

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26248-8_13-2

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26248-8_13-1

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Research in Developmental Psychology

What you’ll learn to do: examine how to do research in lifespan development.

How do we know what changes and stays the same (and when and why) in lifespan development? We rely on research that utilizes the scientific method so that we can have confidence in the findings. How data are collected may vary by age group and by the type of information sought. The developmental design (for example, following individuals as they age over time or comparing individuals of different ages at one point in time) will affect the data and the conclusions that can be drawn from them about actual age changes. What do you think are the particular challenges or issues in conducting developmental research, such as with infants and children? Read on to learn more.

Learning outcomes

- Explain how the scientific method is used in researching development

- Compare various types and objectives of developmental research

- Describe methods for collecting research data (including observation, survey, case study, content analysis, and secondary content analysis)

- Explain correlational research

- Describe the value of experimental research

- Compare the advantages and disadvantages of developmental research designs (cross-sectional, longitudinal, and sequential)

- Describe challenges associated with conducting research in lifespan development

Research in Lifespan Development

How do we know what we know.

An important part of learning any science is having a basic knowledge of the techniques used in gathering information. The hallmark of scientific investigation is that of following a set of procedures designed to keep questioning or skepticism alive while describing, explaining, or testing any phenomenon. Not long ago a friend said to me that he did not trust academicians or researchers because they always seem to change their story. That, however, is exactly what science is all about; it involves continuously renewing our understanding of the subjects in question and an ongoing investigation of how and why events occur. Science is a vehicle for going on a never-ending journey. In the area of development, we have seen changes in recommendations for nutrition, in explanations of psychological states as people age, and in parenting advice. So think of learning about human development as a lifelong endeavor.

Personal Knowledge

How do we know what we know? Take a moment to write down two things that you know about childhood. Okay. Now, how do you know? Chances are you know these things based on your own history (experiential reality), what others have told you, or cultural ideas (agreement reality) (Seccombe and Warner, 2004). There are several problems with personal inquiry or drawing conclusions based on our personal experiences.

Our assumptions very often guide our perceptions, consequently, when we believe something, we tend to see it even if it is not there. Have you heard the saying, “seeing is believing”? Well, the truth is just the opposite: believing is seeing. This problem may just be a result of cognitive ‘blinders’ or it may be part of a more conscious attempt to support our own views. Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for evidence that we are right and in so doing, we ignore contradictory evidence.

Philosopher Karl Popper suggested that the distinction between that which is scientific and that which is unscientific is that science is falsifiable; scientific inquiry involves attempts to reject or refute a theory or set of assumptions (Thornton, 2005). A theory that cannot be falsified is not scientific. And much of what we do in personal inquiry involves drawing conclusions based on what we have personally experienced or validating our own experience by discussing what we think is true with others who share the same views.

Science offers a more systematic way to make comparisons and guard against bias. One technique used to avoid sampling bias is to select participants for a study in a random way. This means using a technique to ensure that all members have an equal chance of being selected. Simple random sampling may involve using a set of random numbers as a guide in determining who is to be selected. For example, if we have a list of 400 people and wish to randomly select a smaller group or sample to be studied, we use a list of random numbers and select the case that corresponds with that number (Case 39, 3, 217, etc.). This is preferable to asking only those individuals with whom we are familiar to participate in a study; if we conveniently chose only people we know, we know nothing about those who had no opportunity to be selected. There are many more elaborate techniques that can be used to obtain samples that represent the composition of the population we are studying. But even though a randomly selected representative sample is preferable, it is not always used because of costs and other limitations. As a consumer of research, however, you should know how the sample was obtained and keep this in mind when interpreting results. It is possible that what was found was limited to that sample or similar individuals and not generalizable to everyone else.

Scientific Methods

The particular method used to conduct research may vary by discipline and since lifespan development is multidisciplinary, more than one method may be used to study human development. One method of scientific investigation involves the following steps:

- Determining a research question

- Reviewing previous studies addressing the topic in question (known as a literature review)

- Determining a method of gathering information

- Conducting the study

- Interpreting the results

- Drawing conclusions; stating limitations of the study and suggestions for future research

- Making the findings available to others (both to share information and to have the work scrutinized by others)

The findings of these scientific studies can then be used by others as they explore the area of interest. Through this process, a literature or knowledge base is established. This model of scientific investigation presents research as a linear process guided by a specific research question. And it typically involves quantitative research , which relies on numerical data or using statistics to understand and report what has been studied.

Another model of research, referred to as qualitative research, may involve steps such as these:

- Begin with a broad area of interest and a research question

- Gain entrance into a group to be researched

- Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities, or other areas of interest

- Ask open-ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing subjects

- Modify research questions as the study continues

- Note patterns or consistencies

- Explore new areas deemed important by the people being observed

- Report findings

In this type of research, theoretical ideas are “grounded” in the experiences of the participants. The researcher is the student and the people in the setting are the teachers as they inform the researcher of their world (Glazer & Strauss, 1967). Researchers should be aware of their own biases and assumptions, acknowledge them, and bracket them in efforts to keep them from limiting accuracy in reporting. Sometimes qualitative studies are used initially to explore a topic and more quantitative studies are used to test or explain what was first described.

A good way to become more familiar with these scientific research methods, both quantitative and qualitative, is to look at journal articles, which are written in sections that follow these steps in the scientific process. Most psychological articles and many papers in the social sciences follow the writing guidelines and format dictated by the American Psychological Association (APA). In general, the structure follows: abstract (summary of the article), introduction or literature review, methods explaining how the study was conducted, results of the study, discussion and interpretation of findings, and references.

Link to Learning

Brené Brown is a bestselling author and social work professor at the University of Houston. She conducts grounded theory research by collecting qualitative data from large numbers of participants. In Brené Brown’s TED Talk The Power of Vulnerability , Brown refers to herself as a storyteller-researcher as she explains her research process and summarizes her results.

Research Methods and Objectives

The main categories of psychological research are descriptive, correlational, and experimental research. Research studies that do not test specific relationships between variables are called descriptive, or qualitative, studies . These studies are used to describe general or specific behaviors and attributes that are observed and measured. In the early stages of research, it might be difficult to form a hypothesis, especially when there is not any existing literature in the area. In these situations designing an experiment would be premature, as the question of interest is not yet clearly defined as a hypothesis. Often a researcher will begin with a non-experimental approach, such as a descriptive study, to gather more information about the topic before designing an experiment or correlational study to address a specific hypothesis. Some examples of descriptive questions include:

- “How much time do parents spend with their children?”

- “How many times per week do couples have intercourse?”

- “When is marital satisfaction greatest?”

The main types of descriptive studies include observation, case studies, surveys, and content analysis (which we’ll examine further in the module). Descriptive research is distinct from correlational research , in which psychologists formally test whether a relationship exists between two or more variables. Experimental research goes a step further beyond descriptive and correlational research and randomly assigns people to different conditions, using hypothesis testing to make inferences about how these conditions affect behavior. Some experimental research includes explanatory studies, which are efforts to answer the question “why” such as:

- “Why have rates of divorce leveled off?”

- “Why are teen pregnancy rates down?”

- “Why has the average life expectancy increased?”

Evaluation research is designed to assess the effectiveness of policies or programs. For instance, research might be designed to study the effectiveness of safety programs implemented in schools for installing car seats or fitting bicycle helmets. Do children who have been exposed to the safety programs wear their helmets? Do parents use car seats properly? If not, why not?

Research Methods

We have just learned about some of the various models and objectives of research in lifespan development. Now we’ll dig deeper to understand the methods and techniques used to describe, explain, or evaluate behavior.

All types of research methods have unique strengths and weaknesses, and each method may only be appropriate for certain types of research questions. For example, studies that rely primarily on observation produce incredible amounts of information, but the ability to apply this information to the larger population is somewhat limited because of small sample sizes. Survey research, on the other hand, allows researchers to easily collect data from relatively large samples. While this allows for results to be generalized to the larger population more easily, the information that can be collected on any given survey is somewhat limited and subject to problems associated with any type of self-reported data. Some researchers conduct archival research by using existing records. While this can be a fairly inexpensive way to collect data that can provide insight into a number of research questions, researchers using this approach have no control over how or what kind of data was collected.

Types of Descriptive Research

Observation.

Observational studies , also called naturalistic observation, involve watching and recording the actions of participants. This may take place in the natural setting, such as observing children at play in a park, or behind a one-way glass while children are at play in a laboratory playroom. The researcher may follow a checklist and record the frequency and duration of events (perhaps how many conflicts occur among 2-year-olds) or may observe and record as much as possible about an event as a participant (such as attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and recording the slogans on the walls, the structure of the meeting, the expressions commonly used, etc.). The researcher may be a participant or a non-participant. What would be the strengths of being a participant? What would be the weaknesses?

In general, observational studies have the strength of allowing the researcher to see how people behave rather than relying on self-report. One weakness of self-report studies is that what people do and what they say they do are often very different. A major weakness of observational studies is that they do not allow the researcher to explain causal relationships. Yet, observational studies are useful and widely used when studying children. It is important to remember that most people tend to change their behavior when they know they are being watched (known as the Hawthorne effect ) and children may not survey well.

Case Studies