- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Developmental Psychology Research Methods

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Jose Luis Pelaez Inc/Getty Images

Cross-Sectional Research Methods

Longitudinal research methods, correlational research methods, experimental research methods.

There are many different developmental psychology research methods, including cross-sectional, longitudinal, correlational, and experimental. Each has its own specific advantages and disadvantages. The one that a scientist chooses depends largely on the aim of the study and the nature of the phenomenon being studied.

Research design provides a standardized framework to test a hypothesis and evaluate whether the hypothesis is correct, incorrect, or inconclusive. Even if the hypothesis is untrue, the research can often provide insights that may prove valuable or move research in an entirely new direction.

At a Glance

In order to study developmental psychology, researchers utilize a number of different research methods. Some involve looking at different cross-sections of a population, while others look at how participants change over time. In other cases, researchers look at how whether certain variables appear to have a relationship with one another. In order to determine if there is a cause-and-effect relationship, however, psychologists much conduct experimental research.

Learn more about each of these different types of developmental psychology research methods, including when they are used and what they can reveal about human development.

Cross-sectional research involves looking at different groups of people with specific characteristics.

For example, a researcher might evaluate a group of young adults and compare the corresponding data from a group of older adults.

The benefit of this type of research is that it can be done relatively quickly; the research data is gathered at the same point in time. The disadvantage is that the research aims to make a direct association between a cause and an effect. This is not always so easy. In some cases, there may be confounding factors that contribute to the effect.

To this end, a cross-sectional study can suggest the odds of an effect occurring both in terms of the absolute risk (the odds of something happening over a period of time) and the relative risk (the odds of something happening in one group compared to another).

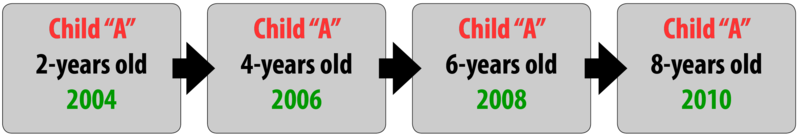

Longitudinal research involves studying the same group of individuals over an extended period of time.

Data is collected at the outset of the study and gathered repeatedly through the course of study. In some cases, longitudinal studies can last for several decades or be open-ended. One such example is the Terman Study of the Gifted , which began in the 1920s and followed 1528 children for over 80 years.

The benefit of this longitudinal research is that it allows researchers to look at changes over time. By contrast, one of the obvious disadvantages is cost. Because of the expense of a long-term study, they tend to be confined to a smaller group of subjects or a narrower field of observation.

Challenges of Longitudinal Research

While revealing, longitudinal studies present a few challenges that make them more difficult to use when studying developmental psychology and other topics.

- Longitudinal studies are difficult to apply to a larger population.

- Another problem is that the participants can often drop out mid-study, shrinking the sample size and relative conclusions.

- Moreover, if certain outside forces change during the course of the study (including economics, politics, and science), they can influence the outcomes in a way that significantly skews the results.

For example, in Lewis Terman's longitudinal study, the correlation between IQ and achievement was blunted by such confounding forces as the Great Depression and World War II (which limited educational attainment) and gender politics of the 1940s and 1950s (which limited a woman's professional prospects).

Correlational research aims to determine if one variable has a measurable association with another.

In this type of non-experimental study, researchers look at relationships between the two variables but do not introduce the variables themselves. Instead, they gather and evaluate the available data and offer a statistical conclusion.

For example, the researchers may look at whether academic success in elementary school leads to better-paying jobs in the future. While the researchers can collect and evaluate the data, they do not manipulate any of the variables in question.

A correlational study can be appropriate and helpful if you cannot manipulate a variable because it is impossible, impractical, or unethical.

For example, imagine that a researcher wants to determine if living in a noisy environment makes people less efficient in the workplace. It would be impractical and unreasonable to artificially inflate the noise level in a working environment. Instead, researchers might collect data and then look for correlations between the variables of interest.

Limitations of Correlational Research

Correlational research has its limitations. While it can identify an association, it does not necessarily suggest a cause for the effect. Just because two variables have a relationship does not mean that changes in one will affect a change in the other.

Unlike correlational research, experimentation involves both the manipulation and measurement of variables . This model of research is the most scientifically conclusive and commonly used in medicine, chemistry, psychology, biology, and sociology.

Experimental research uses manipulation to understand cause and effect in a sampling of subjects. The sample is comprised of two groups: an experimental group in whom the variable (such as a drug or treatment) is introduced and a control group in whom the variable is not introduced.

Deciding the sample groups can be done in a number of ways:

- Population sampling, in which the subjects represent a specific population

- Random selection , in which subjects are chosen randomly to see if the effects of the variable are consistently achieved

Challenges in Experimental Resarch

While the statistical value of an experimental study is robust, it may be affected by confirmation bias . This is when the investigator's desire to publish or achieve an unambiguous result can skew the interpretations, leading to a false-positive conclusion.

One way to avoid this is to conduct a double-blind study in which neither the participants nor researchers are aware of which group is the control. A double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) is considered the gold standard of research.

What This Means For You

There are many different types of research methods that scientists use to study developmental psychology and other areas. Knowing more about how each of these methods works can give you a better understanding of what the findings of psychological research might mean for you.

Capili B. Cross-sectional studies . Am J Nurs . 2021;121(10):59-62. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000794280.73744.fe

Kesmodel US. Cross-sectional studies - what are they good for? . Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand . 2018;97(4):388–393. doi:10.1111/aogs.13331

Noordzij M, van Diepen M, Caskey FC, Jager KJ. Relative risk versus absolute risk: One cannot be interpreted without the other . Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2017;32(S2):ii13-ii18. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfw465

Kell HJ, Wai J. Terman Study of the Gifted . In: Frey B, ed. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation . Vol. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2018. doi:10.4135/9781506326139.n691

Curtis EA, Comiskey C, Dempsey O. Importance and use of correlational research . Nurse Res . 2016;23(6):20–25. doi:10.7748/nr.2016.e1382

Misra S. Randomized double blind placebo control studies, the "Gold Standard" in intervention based studies . Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS . 2012;33(2):131-4. doi:10.4103/2589-0557.102130

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Lifespan Developmental Research Methodologies

Ellen Skinner; Julia Dancis; and The Human Development Teaching & Learning Group

Learning Objectives: Lifespan Developmental Methodologies

- Explain the importance of complementary multidisciplinary methodologies and converging operations.

- Recognize the steps in deductive , inductive , and collaborative methodologies.

- Be familiar with the many methods developmentalists use to gather information, including observations and self-reports, psychological tests and assessments, laboratory tasks, psychophysiological assessments, archival data or artifacts, case studies, and enthnographies.

- Identify the general strengths and limitations of different methods (e.g., reactivity, social desirability, accessibility, generalizability).

Because interventionists and practitioners use bodies of scientific evidence to transform systems and change practices in the world, it is crucial that researchers produce the highest quality evidence possible, and evaluate and critique it thoughtfully. The tools that scientists use to generate such knowledge are called research methods or methodologies. Many textbooks describe “the” scientific method, as if there were only one way of knowing scientifically. Just as lifespan development spans multiple disciplines, each with their own preferred epistemologies and methodologies, we believe that there are multiple scientific methods, or multiple perspectives, each one providing a complementary line of sight on a given target phenomenon. Social and developmental sciences have been critiqued for our reliance on a narrow range of methodologies, favoring methods that quantify observations (e.g., via surveys, ratings, or numerical codings) and control extraneous variables or confounds, either statistically or, for example, by bringing people into the lab. Social scientists often seem to favor these more quantitative methods, and to discount methodologies that are more situated, contextualized, and wholistic, sometimes called qualitative methods.

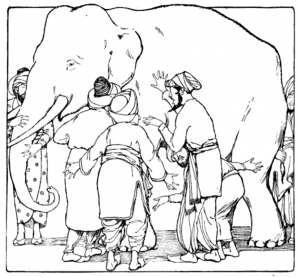

However, it has become clear that these methodologies are not antagonistic. Instead, they are complementary ways of knowing or lines of sight on target phenomena, each whole and important in its own right, but incomplete. We think about these multiple perspectives the same way that they are described in the parable of the six blind men and the elephant. In this story, each person makes contact with a different part of the elephant and comes to his own conclusions– the one who encounters its legs explains that elephants are tree trunks, the ears reveal it to be a fan, the flank a wall, the tail a rope, the trunk a snake, and the tusk a spear.

Each one’s understanding is correct, but unknown to all of them, each is also incomplete. They need the views from all of these perspectives, what we sometimes call 360 o lines of sight, to fully appreciate the elephant in its wholeness and complexity. In the same way, multiple cross-disciplinary, inter-disciplinary, and multi-disciplinary methodologies are needed to understand our developmental phenomena in their wholeness and complexity. We find a lifespan developmental systems perspective especially useful in articulating this view (Baltes, Reese, & Nesselroade, 1977; Cairns, Elder, & Costello, 2001; Lerner, 2006; Overton, 2010; Overton & Molenaar, 2015; Skinner, Kindermann, & Mashburn, 2019). The best research and graduate training programs in human development teach their doctoral students about a wide range of epistemologies and methodologies and see them all as parts of “ converging operations .”

What is meant by converging operations?

This was an idea, brought to the attention of developmentalists almost 50 years ago (Baer, 1973), to help deal with the unsettling realization that every method ever devised to conduct scientific studies has serious shortcomings. The main idea is that good science needs a wide variety of differing methodologies, so that the strengths of one can compensate for the limitations of others. From this perspective, a body of evidence is much stronger when findings from multiple complementary methodologies converge on the same conclusions. That is why we favor developmental science that incorporates methodologies from many disciplines, and continues to question and critique those methodologies as part of its reflective practice.

Deductive Methodologies

In discussions of scientific methods, the procedure that is often highlighted is the deductive method — in which a scientist starts with a falsifiable hypothesis and then conducts a series of observations to test whether the specifics on the ground are consistent with this hypothesis. In this process, the scientist foregrounds “thinking” (the theory) and follows this up with figuring out how to “look” (i.e., conduct the study or observation) in ways that test the validity of this theory. This process unfolds in multiple recursive or circular steps, including:

- Review previous studies (known as a literature review) to determine what has been found to date

- Identify the deficiencies or gaps in previous research

- Formulate a working theory of the target phenomenon and propose a hypothesis

- Who? Sampling . Determine the people to be included

- What? Measurement . Determine the measures to be used to capture the phenomena of interest

- Where? Setting . Determine the setting where the study will take place

- How? and When? Design . Determine the study design

- Consider the limitations of the study

- Draw conclusions, including rejecting the hypothesis and revising the original theory

- Suggest future studies

- Share information with the scientific community

- Invite scrutiny of work by other experts

Inductive Methodologies

A second set of procedures is more inductive . This process, often called grounded theory , starts with a general question and then constructs a theory of the phenomenon based, not on the scientific community’s or researcher’s preconceived notions, but on the researcher’s actual observations of many specific experiences on the ground. As you can see, in the process, the scientist foregrounds “looking” (the observations and experiences in the target setting) and uses this process to scaffold “thinking” (i.e., theorizing or building a mental model of what has been observed). This process also unfolds in multiple recursive or circular steps, including:

- Review the literature to justify the importance of the problem

- See how the problem fits into a larger set of issues

- Identify the deficiencies or gaps in other work on the topic

- Who? and Where? Gain entrance into a group and natural setting relevant to the problem of study

- What? Ask open-ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing and observing participants; focus on participant perspectives

- How? Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities or other areas of interest; collect artifacts, pictures

- Reflect . Modify research questions as the study evolves and follow the emergent questions

- Note own participation and biases

- Note patterns or consistencies, uncover themes, categories, interrelationships

- Focus on centrality of meaning of the participants

- Explore new areas deemed important by participants

- Check back in with participants to get their perspectives on your interpretations

Collaborative Methodologies

A third set of methodologies is based on the assumption that knowledge, research, and effective social action can best be co-constructed among researchers and community participants, incorporating the strengths and perspectives of all the stakeholders involved in a particular set of issues. This approach, often called community-based participatory action research , holds that complex social issues cannot be well understood or resolved by “expert” research, pointing to interventions from outside of the community which often have disappointing results or unintended side effects. In collaborative approaches, researchers and community partners build a genuine trusting relationship, and this cooperative partnership is the basis on which all decisions about the project are made: from articulating a set of research questions, to identifying data collection strategies, analysis and interpretation of information, and dissemination and application of findings.

The process is inherently:

- Community-based. Researchers build a collaborative partnership with community members who are already living with, involved in, or working on the problem of interest. Hence, this work is situated within neighborhoods and community organizations or groups, and builds on their strengths and priorities. Instead of taking individuals out of communities and into lab settings for study or providing individualized therapy to “fix” broken individuals, the goal of this work is to help facilitate change within the community itself, making it a more supportive context for all its inhabitants.

- Participatory . As the collaboration develops, members discuss and learn more about each other so that together they can co-create and frame a common agenda for research and action. These projects incorporate researchers’ expertise and goals, but they foreground the knowledge, concerns, and needs of community partners. For example, researchers interested in homeless youth could reach out to youth-serving organizations and begin conversations exploring whether they would like to work together. These conversations would also soon involve the homeless youth themselves, consistent with the slogan popularized by the disability rights movement, “Nothing about us without us!” Community knowledge is considered irreplaceable as it provides key insights about target issues.

- Action. All research activities are anchored and oriented by the larger goal of enhancing strategic action that leads to social change and community transformation as part of the research program. Community action make take the form of public education surrounding community issues (e.g., information campaigns, teach-ins), changing existing policies that harm groups of people (e.g., harsh discipline policies at school), creating new public spaces (e.g., community gardens and farmers’ markets), and so on.

- Research. The community action plan is informed by organizing existing information and collecting new information from key stakeholders relevant to the community issues under scrutiny. Methods to conduct these studies are planned together in ways that researchers believe will produce high quality information and that collaborators believe will be useful to them in making progress on their agenda. All partners are also involved in the scrutiny, visualization, discussion, and interpretation of data, and make joint decisions about how it should be disseminated and used going forward. These efforts feed into next steps in both research and action.

- Ongoing collaboration. Such university-community partnerships typically last for many years. Researchers are thoughtful about how to bring them successfully to a close, making sure that an ongoing goal of the collaboration is to build capacity within the community partnership so members can sustain collective action after the research team leaves.

A good way to become more familiar with these collaborative, inductive, and deductive research methods is to look at journal articles. You will see that they are written in sections that follow the steps in the scientific process. In general, the structure includes: (1) abstract (summary of the article), (2) introduction or literature review, (3) methods explaining how the study was conducted, (4) results of the study, (5) discussion and interpretation of findings, and (6) references (a list of studies cited in the article).

Methods of Gathering Information

“Methods” is also a name given to many different procedures scientists use to make their observations or collect information. Since developmentalists are interested in a wide range of human capacities, they want to know not only about people’s actions and thoughts, as expressed in words and deeds, but also about underlying processes, like abilities, emotions, desires, intentions, and motivations. Moreover, they want to go deeper, looking into biological and neurophysiological processes, and they want to consider many factors outside the person of study, looking at social relationships and interactions, as well as environmental materials, tasks, and affordances, and societal contexts. And, as lifespan researchers, they want to study these capacities at all ages, from the tiniest babies to the oldest grandmothers. No wonder developmental scientists need so many tools, and are inventing more all the time.

Every time you come across a conclusion in a textbook or research article (for example, when you read that “18-month-olds do not yet have a sense of self”), you should stop and ask, “How do you know that?” That is a great question. And a great scientific attitude. Over and over, we will want to scrutinize the evidence scientists are using to make their conclusions, considering carefully the extent to which the methods scientists use justify the conclusions they make. If a baby can’t yet talk, how would we know whether they have a sense of self? And even when a child can talk, what is the connection between what they are telling us and what they are truly thinking? You can be sure that these kinds of questions stoke lively debates in scientific circles.

As with methodologies more generally, science is strengthened by the use of a variety of approaches to collecting information. The shortcomings of one can be compensated for by the strengths of others. If we find that a new mother says that she is feeling stressed, and her best friend agrees, and we see elevated cortisol levels, and her survey results are higher than usual, and she becomes irritated when her two-year-old makes a mess– well, we think we have captured something meaningful here. We are always in favor of multiple sources of data, and we especially appreciate methods that get us thick, rich information, as close to lived experience in context as possible.

Here are some examples of methods commonly used in developmental research today:

Observations: Looking at People and their Actions

Often considered the basic building blocks of developmental science, observational methods are those in which the researcher carefully watches participants, noting what they are doing, saying, and expressing, both verbally and nonverbally. Researchers can observe participants doing just about anything, including working on tasks, playing with toys, reading the newspaper, or interacting with others. Observations are ideal for gathering information about people’s verbal and physical behavior, but it is less clear whether internal states, like emotions and intentions, can be unambiguously discerned through observation.

- Naturalistic observations take place when researchers conduct observations in the regular settings of everyday life. This method allows researchers to get very close to the phenomenon as it actually unfolds, but researchers worry that their participation may impact participants’ behaviors (a problem called reactivity ). And, since researchers have little control over the environment, they realize that the different behaviors they observe may be due to differences in situational factors.

- Laboratory observations , in contrast, take place in a specialized setting created by the researcher, that is, the lab. For example, researchers bring babies and their caregivers to the lab in a systematic procedure known as the strange situation, which you will learn about in the section on attachment. Observing in the lab allows researchers to set up a specific space and to have control over situational factors. However, researchers worry that the artificial nature of the situation may have an impact on people’s behavior, and that the behaviors people show in the lab are not typical of the ones they show in regular contexts of daily life (a problem called generalizability ).

- Video or audio observations can be gathered using automatic recording devices that collect information even when a researcher is not present. For example, researchers ask caregivers to record family dinners or teachers to tape class sessions; or place a small recording device on a young child’s chest that records every word the child says or hears. These records can then be watched or listened to by researchers. Such procedures reduce reactivity, but the resultant recordings are narrower in scope than what researchers could hear or see if they were present observing in the actual context.

- Local expert observers can provide researchers with information about the verbal and non-verbal behavior of participants they have observed or interacted with many times. For example, caregivers and teachers can report on their children and students, and even children can provide their perspectives. Reports from others typically incorporate many more observations than a researcher could collect (e.g., a teacher sees a child in class every week day), so the information is more representative of the target’s typical behavior. However, researchers worry that information could be distorted, for example, because reporters are biased or are not trained to observe or categorize the behaviors they have witnessed.

- Participant observations, which are especially common in anthropology and sociology, take place when researchers gain entrance into a setting, not as an observer, but as a participant, with the aim of gaining a close and intimate familiarity with a given group of individuals or a particular community, and their behaviors, relationships, and practices. These observations are usually conducted over an extended period of time, sometimes months or years, which means that the observer can directly observe variations and changes in actions and interactions. Such observations provide rich and detailed information, but are limited to the specific setting.

Self-reports: Listening to People and their Thoughts

When researchers are studying people, one of the most common ways of gathering information about them is by asking them, via self-report methods. These can range from informal open-ended interviews or requests for participants to write responses to prompts, all the way to surveys, when participants can only choose among researcher-generated options. Self-report data are ideal for learning about people’s inner thoughts or opinions, but researchers worry that participants may distort the truth to present themselves in a favorable light (a problem called social desirability ). There is also debate about whether participants have access to some of their internal processes, like their genuine motivations.

- Surveys gather information using standardized questionnaires, which can be administered either verbally or in writing. Surveys capture an enormous range of psychological and social processes, and their items can be tested for their reliability and validity (called psychometric properties ), but they typically yield only surface information. Researchers worry that participants may misinterpret questions and realize that the information so collected is restricted to exactly those pre-packaged questions and responses.

- Standardized, structured, or semi-structured interviews involve researchers directly asking a series of predetermined questions. Because researchers are present, they can ask follow up questions and participants can ask for clarification. This allows researchers to learn more from participants than they could from standardized questionnaires, but researchers worry that their presence could cause reactivity , such as when participants want to provide more socially desirable responses in a face-to-face setting than on an anonymous survey.

- Open-ended interviews typically use targeted questions or prompts to get the conversation flowing, and then follow the interview where ever it leads. This allows for more customized questioning and in-depth answers, as researchers probe responses for greater clarity and understanding. However, since each respondent participates in a different interview conversation, it can be difficult to compare responses from person to person.

- Focus groups involve group open-ended interviews, in which a small number of people (6-10) discuss a series of questions or prompts in guided or open discussion with a trained facilitator. In this format, focus group members listen and can react to each other’s comments and build discussion at the group level.

- Responses to prompts are used when researchers ask participants to write down their thoughts. These can range from relatively unstructured free writes to short answers to a series of well-structured questions. Daily diaries , often organized electronically, allow participants to respond to online questions or prompts many days in a row.

Psychological Tests and Assessments: Mental Capacities and Conditions

Most of us are familiar with tests that measure, for example, IQ or other mental abilities, and with diagnostic assessments that classify people according to psychological conditions. When you read about the aging of intelligence, for example, some of those studies utilize measures of crystalized and fluid intelligence. Tests to measure mental abilities have been created for people of all ages, although it is not always clear how the measures used at different ages are connected to each other.

Laboratory Tasks: Interactions that Elicit or Capture Psychological Processes

Researchers create and invent all manner of tasks for participants to work on, either in the lab or in real life settings (e.g., at home or school). These tasks allow researchers to set up activities that can assess a range of psychological attributes for people of all ages, ranging from problem-solving abilities to regulatory capacities (e.g., using the “ Heads, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes ” task), prosocial behaviors, learned helplessness, theories of mind, social information processing, rejection sensitivity, and so on. Many YouTube videos show children and adolescents participating in these tasks, and it is instructive to try to figure out exactly what is captured in each one. If you would like to see an example, you can watch a video of The Shopping Cart Study (not required, bonus information).

Psychophysiological Assessment: Underlying Neurophysiological Functioning

Researchers also use a range of methods to capture information about neurophysiological functioning across the lifespan, including technology that can measure heart rate, blood pressure, hormone levels, and many kinds of brain activity to help explain development. These assessments provide information about what is happening “under the skin,” and researchers can see how these biological processes are connected to behavioral development. Usually connections are bidirectional– neurophysiology contributes to the development of behavior, and behaviors shape physiological functioning and development.

Archival Data or Artifacts: Information from Business as Usual

Researchers sometimes utilize information that has already been collected as a regular part of daily life. Such data include, for example, students’ grades and achievement tests scores, documents or other media, drawings, work products, or other materials that might provide information about participants’ developmental progress or causal factors contributing to their development. These kinds of data have the advantage of low reactivity and high authenticity, in that they were created or gathered in the normal course of events, but it is sometimes unclear exactly what they mean or what constructs they measure.

Case Study: All of the Above with Carefully Selected Participants or Settings

One of the best ways to gather in depth information about a person or group of people (e.g., a classroom, school, or neighborhood) is through a research methodology called the case study . Researchers focus on only one or a small number of target units, usually carefully selected for specific characteristics (e.g., an individual identified as wise, a homeless teenager, a very effective school, or a workplace with high turnover rates), and amass everything they can about that person or place. Researchers typically conduct in-depth open-ended interviews with people, including friends or family of the target person, and collect archival data and artifacts, which they might discuss in depth with participants. For example, they might go through the person’s photo albums and discuss memories of their early life. Classical examples of case studies are the so-called baby diaries , in which researchers like Jean Piaget and William Stern conducted extensive observations on their individual children and took detailed notes about every aspect of their behavior and development. They also tested some of their hypotheses about development, by giving their babies toys to play with or engaging them in interesting tasks. These case studies were conducted over years. When case studies also extend into the past of the individual (for example, when researchers are interested in life review processes), they can be called biographical methods .

Sometimes researchers who focus on a group of individuals or a setting are particularly interested in the cultural context and its functioning. These studies can be called ethnographies . Drawn originally from anthropology, ethnographic methods describe an approach in which researchers carefully study and document people and their cultural settings, usually through extensive participant-observation, interviews, and engagement in the setting. In these studies, as in all scientific investigations, researchers are the students and the people in the setting are the teachers. Researchers strive to create a wholistic, higher-order narrative account that privileges the perspectives of the people studied.

Take Home Messages about Lifespan Developmental Methodologies

We would highlight four main themes from this section:

- Because interventionists and practitioners use bodies of scientific evidence to transform systems and change practices in the world, it is crucial that researchers produce the highest quality evidence possible , and evaluate and critique it thoughtfully.

- Developmental science incorporates multiple methodologies from many disciplines, and these deductive, inductive, and collaborative methodologies make our conclusions stronger because they provide complementary lines of sight on our target phenomena.

- Science is also strengthened by the use of a variety of approaches (or methods) for collecting information , including observations, self-reports, and other strategies, because together they provide a richer picture of our target developing phenomena.

- The advantages of using multiple methodologies and sources of information are highlighted by the idea of “ converging operations, ” which points out that this practice allows the shortcomings of one method to be compensated for by the strengths of others, and reminds us that bodies of evidence are stronger when findings from multiple complementary methodologies and sources of information converge on the same conclusions.

Baer, D. M. (1973). The control of developmental process: Why wait? In J. R. Nesselroade & H. W. Reese (Eds.), Lifespan developmental psychology: Methodological issues (pp. 187-193). New York: Academic Press.

Baltes, P. B., Reese, H. W., & Nesselroade, J. R. (1977). Life-span developmental psychology: Introduction to research methods . Oxford, England: Brooks/Cole.

Cairns, R. B., Elder, G. H., & Costello, E. J. (Eds.). (2001). Developmental science . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lerner, R. M. (2006). Developmental science, developmental systems, and contemporary theories of human development. In R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.) and R. M. Lerner & W. E. Damon (Eds-in-Chief.). Handbook of child psychology: Vol 1, Theoretical models of human development (pp. 1-17). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Overton, W. F. (2010). Life‐span development: Concepts and issues. In W. F. Overton (Vol. Ed.) R.M. Lerner (Ed.-in-Chief), The handbook of life-span development: Vol. 1. Cognition, biology, and methods (pp. 1-29). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Overton, W. F., & Molenaar, P. (2015). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (R. M. Lerner, Ed.-in-Chief) : Vol 1, Theory and method . John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, & Mashburn, A. J. (2019). Lifespan developmental systems: Meta-theory, methodology, and the study of applied problems. An Advanced Textbook . New York, NY: Routledge.

Media Attributions

- Blind_men_and_elephant

Lifespan Developmental Research Methodologies Copyright © 2020 by Ellen Skinner; Julia Dancis; and The Human Development Teaching & Learning Group. All Rights Reserved.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.2 Research Methods

Learning objectives.

- Describe methods for collecting research data (including observation, survey, case study, content analysis, and secondary content analysis)

We have just learned about some of the various models and objectives of research in lifespan development. Now we’ll dig deeper to understand the methods and techniques used to describe, explain, or evaluate behavior.

All types of research methods have unique strengths and weaknesses, and each method may only be appropriate for certain types of research questions. For example, studies that rely primarily on observation produce incredible amounts of information, but the ability to apply this information to the larger population is somewhat limited because of small sample sizes. Survey research, on the other hand, allows researchers to easily collect data from relatively large samples. While this allows for results to be generalized to the larger population more easily, the information that can be collected on any given survey is somewhat limited and subject to problems associated with any type of self-reported data. Some researchers conduct archival research by using existing records. While this can be a fairly inexpensive way to collect data that can provide insight into a number of research questions, researchers using this approach have no control on how or what kind of data was collected.

Types of Descriptive Research

Observation.

Observational studies , also called naturalistic observation, involve watching and recording the actions of participants. This may take place in the natural setting, such as observing children at play in a park, or behind a one-way glass while children are at play in a laboratory playroom. The researcher may follow a checklist and record the frequency and duration of events (perhaps how many conflicts occur among 2-year-olds) or may observe and record as much as possible about an event as a participant (such as attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and recording the slogans on the walls, the structure of the meeting, the expressions commonly used, etc.). The researcher may be a participant or a non-participant. What would be the strengths of being a participant? What would be the weaknesses?

In general, observational studies have the strength of allowing the researcher to see how people behave rather than relying on self-report. One weakness of self-report studies is that what people do and what they say they do are often very different. A major weakness of observational studies is that they do not allow the researcher to explain causal relationships. Yet, observational studies are useful and widely used when studying children. It is important to remember that most people tend to change their behavior when they know they are being watched (known as the Hawthorne effect ) and children may not survey well.

Case Studies

Case studies involve exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Information may be gathered with the use of observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation. Case studies are helpful when investigating unusual situations such as brain trauma or children reared in isolation. And they are often used by clinicians who conduct case studies as part of their normal practice when gathering information about a client or patient coming in for treatment. Case studies can be used to explore areas about which little is known and can provide rich detail about situations or conditions. However, the findings from case studies cannot be generalized or applied to larger populations; this is because cases are not randomly selected and no control group is used for comparison. (Read The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat by Dr. Oliver Sacks as a good example of the case study approach.)

Surveys are familiar to most people because they are so widely used. Surveys enhance accessibility to subjects because they can be conducted in person, over the phone, through the mail, or online. A survey involves asking a standard set of questions to a group of subjects. In a highly structured survey, subjects are forced to choose from a response set such as “strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, strongly agree”; or “0, 1-5, 6-10, etc.” Surveys are commonly used by sociologists, marketing researchers, political scientists, therapists, and others to gather information on many variables in a relatively short period of time. Surveys typically yield surface information on a wide variety of factors, but may not allow for an in-depth understanding of human behavior.

Of course, surveys can be designed in a number of ways. They may include forced-choice questions and semi-structured questions in which the researcher allows the respondent to describe or give details about certain events. One of the most difficult aspects of designing a good survey is wording questions in an unbiased way and asking the right questions so that respondents can give a clear response rather than choosing “undecided” each time. Knowing that 30% of respondents are undecided is of little use! So a lot of time and effort should be placed on the construction of survey items. One of the benefits of having forced-choice items is that each response is coded so that the results can be quickly entered and analyzed using statistical software. The analysis takes much longer when respondents give lengthy responses that must be analyzed in a different way. Surveys are useful in examining stated values, attitudes, opinions, and reporting on practices. However, they are based on self-report, or what people say they do rather than on observation, and this can limit accuracy. Validity refers to accuracy and reliability refers to consistency in responses to tests and other measures; great care is taken to ensure the validity and reliability of surveys.

In this video, Harvard psychologist Dan Gilbert explains survey research that was conducted to explore the way our preferences change over time.

You can view the transcript for “The psychology of your future self | Dan Gilbert” here (opens in new window) .

Content Analysis

Content analysis involves looking at media such as old texts, pictures, commercials, lyrics or other materials to explore patterns or themes in culture. An example of content analysis is the classic history of childhood by Aries (1962) called “Centuries of Childhood” or the analysis of television commercials for sexual or violent content or for ageism. Passages in text or television programs can be randomly selected for analysis as well. Again, one advantage of analyzing work such as this is that the researcher does not have to go through the time and expense of finding respondents, but the researcher cannot know how accurately the media reflects the actions and sentiments of the population.

Secondary content analysis, or archival research, involves analyzing information that has already been collected or examining documents or media to uncover attitudes, practices or preferences. There are a number of data sets available to those who wish to conduct this type of research. The researcher conducting secondary analysis does not have to recruit subjects but does need to know the quality of the information collected in the original study. And unfortunately, the researcher is limited to the questions asked and data collected originally.

Link to Learning: Data on Human Development

U.S. Census Data is available and widely used to look at trends and changes taking place in the United States (visit the United States Census website and check it out). There are also a number of other agencies that collect data on family life, sexuality, and on many other areas of interest in human development (go to the NORC at the University of Chicago website or the Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation website and see what you find.).

- Psyc 200 Lifespan Psychology. Authored by : Laura Overstreet. Located at : http://opencourselibrary.org/econ-201/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- magnifying glass. Authored by : nachar. Located at : https://pixabay.com/en/magnifying-glass-magnifier-glass-189254/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Survey. Authored by : Andreas Breitling. Located at : https://pixabay.com/images/id-1594962/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- The psychology of your future self | Dan Gilbert. Provided by : TED. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XNbaR54Gpj4 . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

3.2 Research Methods Copyright © by Meredith Palm is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Topic Guides

- Human Development Research Resources

- Introduction

Human Development Research Resources: Introduction

- Finding Information

- Evaluating Information

- Ethical Information Use

- Getting Help

Human Development studies how humans learn and develop, from birth through old age and in many specific contexts. Researchers might look at how children are affected when their parents are incarcerated or how close friendships change as we grow older. The field mixes principles of psychology, sociology, and health to study and improve people's daily life experiences.

Writing in Human Development

Scholars and professionals in human development write in a variety of genres. Scholars may write literature reviews, journal articles, book reviews, and books. All of this writing will be based on and incorporate scholarly literature and human development theory. Professionals working in human services will often need to write content related to their jobs, such as client reports, reports for an organization, client histories, and grant applications.

As a student in human development, you'll be asked to read and to write in a range of these genres.

- Next: Finding Information >>

- Last Updated: Apr 20, 2020 2:10 PM

Research in Developmental Psychology

What you’ll learn to do: examine how to do research in lifespan development.

How do we know what changes and stays the same (and when and why) in lifespan development? We rely on research that utilizes the scientific method so that we can have confidence in the findings. How data are collected may vary by age group and by the type of information sought. The developmental design (for example, following individuals as they age over time or comparing individuals of different ages at one point in time) will affect the data and the conclusions that can be drawn from them about actual age changes. What do you think are the particular challenges or issues in conducting developmental research, such as with infants and children? Read on to learn more.

Learning outcomes

- Explain how the scientific method is used in researching development

- Compare various types and objectives of developmental research

- Describe methods for collecting research data (including observation, survey, case study, content analysis, and secondary content analysis)

- Explain correlational research

- Describe the value of experimental research

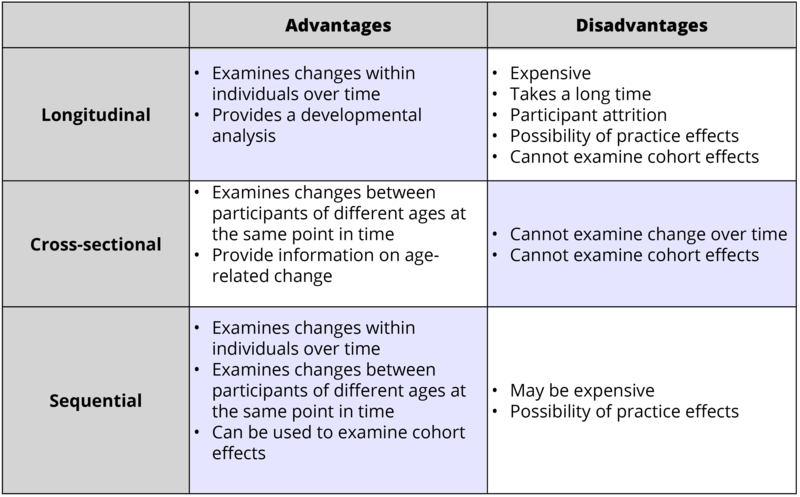

- Compare the advantages and disadvantages of developmental research designs (cross-sectional, longitudinal, and sequential)

- Describe challenges associated with conducting research in lifespan development

Research in Lifespan Development

How do we know what we know.

An important part of learning any science is having a basic knowledge of the techniques used in gathering information. The hallmark of scientific investigation is that of following a set of procedures designed to keep questioning or skepticism alive while describing, explaining, or testing any phenomenon. Not long ago a friend said to me that he did not trust academicians or researchers because they always seem to change their story. That, however, is exactly what science is all about; it involves continuously renewing our understanding of the subjects in question and an ongoing investigation of how and why events occur. Science is a vehicle for going on a never-ending journey. In the area of development, we have seen changes in recommendations for nutrition, in explanations of psychological states as people age, and in parenting advice. So think of learning about human development as a lifelong endeavor.

Personal Knowledge

How do we know what we know? Take a moment to write down two things that you know about childhood. Okay. Now, how do you know? Chances are you know these things based on your own history (experiential reality), what others have told you, or cultural ideas (agreement reality) (Seccombe and Warner, 2004). There are several problems with personal inquiry or drawing conclusions based on our personal experiences.

Our assumptions very often guide our perceptions, consequently, when we believe something, we tend to see it even if it is not there. Have you heard the saying, “seeing is believing”? Well, the truth is just the opposite: believing is seeing. This problem may just be a result of cognitive ‘blinders’ or it may be part of a more conscious attempt to support our own views. Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for evidence that we are right and in so doing, we ignore contradictory evidence.

Philosopher Karl Popper suggested that the distinction between that which is scientific and that which is unscientific is that science is falsifiable; scientific inquiry involves attempts to reject or refute a theory or set of assumptions (Thornton, 2005). A theory that cannot be falsified is not scientific. And much of what we do in personal inquiry involves drawing conclusions based on what we have personally experienced or validating our own experience by discussing what we think is true with others who share the same views.

Science offers a more systematic way to make comparisons and guard against bias. One technique used to avoid sampling bias is to select participants for a study in a random way. This means using a technique to ensure that all members have an equal chance of being selected. Simple random sampling may involve using a set of random numbers as a guide in determining who is to be selected. For example, if we have a list of 400 people and wish to randomly select a smaller group or sample to be studied, we use a list of random numbers and select the case that corresponds with that number (Case 39, 3, 217, etc.). This is preferable to asking only those individuals with whom we are familiar to participate in a study; if we conveniently chose only people we know, we know nothing about those who had no opportunity to be selected. There are many more elaborate techniques that can be used to obtain samples that represent the composition of the population we are studying. But even though a randomly selected representative sample is preferable, it is not always used because of costs and other limitations. As a consumer of research, however, you should know how the sample was obtained and keep this in mind when interpreting results. It is possible that what was found was limited to that sample or similar individuals and not generalizable to everyone else.

Scientific Methods

The particular method used to conduct research may vary by discipline and since lifespan development is multidisciplinary, more than one method may be used to study human development. One method of scientific investigation involves the following steps:

- Determining a research question

- Reviewing previous studies addressing the topic in question (known as a literature review)

- Determining a method of gathering information

- Conducting the study

- Interpreting the results

- Drawing conclusions; stating limitations of the study and suggestions for future research

- Making the findings available to others (both to share information and to have the work scrutinized by others)

The findings of these scientific studies can then be used by others as they explore the area of interest. Through this process, a literature or knowledge base is established. This model of scientific investigation presents research as a linear process guided by a specific research question. And it typically involves quantitative research , which relies on numerical data or using statistics to understand and report what has been studied.

Another model of research, referred to as qualitative research, may involve steps such as these:

- Begin with a broad area of interest and a research question

- Gain entrance into a group to be researched

- Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities, or other areas of interest

- Ask open-ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing subjects

- Modify research questions as the study continues

- Note patterns or consistencies

- Explore new areas deemed important by the people being observed

- Report findings

In this type of research, theoretical ideas are “grounded” in the experiences of the participants. The researcher is the student and the people in the setting are the teachers as they inform the researcher of their world (Glazer & Strauss, 1967). Researchers should be aware of their own biases and assumptions, acknowledge them, and bracket them in efforts to keep them from limiting accuracy in reporting. Sometimes qualitative studies are used initially to explore a topic and more quantitative studies are used to test or explain what was first described.

A good way to become more familiar with these scientific research methods, both quantitative and qualitative, is to look at journal articles, which are written in sections that follow these steps in the scientific process. Most psychological articles and many papers in the social sciences follow the writing guidelines and format dictated by the American Psychological Association (APA). In general, the structure follows: abstract (summary of the article), introduction or literature review, methods explaining how the study was conducted, results of the study, discussion and interpretation of findings, and references.

Link to Learning

Brené Brown is a bestselling author and social work professor at the University of Houston. She conducts grounded theory research by collecting qualitative data from large numbers of participants. In Brené Brown’s TED Talk The Power of Vulnerability , Brown refers to herself as a storyteller-researcher as she explains her research process and summarizes her results.

Research Methods and Objectives

The main categories of psychological research are descriptive, correlational, and experimental research. Research studies that do not test specific relationships between variables are called descriptive, or qualitative, studies . These studies are used to describe general or specific behaviors and attributes that are observed and measured. In the early stages of research, it might be difficult to form a hypothesis, especially when there is not any existing literature in the area. In these situations designing an experiment would be premature, as the question of interest is not yet clearly defined as a hypothesis. Often a researcher will begin with a non-experimental approach, such as a descriptive study, to gather more information about the topic before designing an experiment or correlational study to address a specific hypothesis. Some examples of descriptive questions include:

- “How much time do parents spend with their children?”

- “How many times per week do couples have intercourse?”

- “When is marital satisfaction greatest?”

The main types of descriptive studies include observation, case studies, surveys, and content analysis (which we’ll examine further in the module). Descriptive research is distinct from correlational research , in which psychologists formally test whether a relationship exists between two or more variables. Experimental research goes a step further beyond descriptive and correlational research and randomly assigns people to different conditions, using hypothesis testing to make inferences about how these conditions affect behavior. Some experimental research includes explanatory studies, which are efforts to answer the question “why” such as:

- “Why have rates of divorce leveled off?”

- “Why are teen pregnancy rates down?”

- “Why has the average life expectancy increased?”

Evaluation research is designed to assess the effectiveness of policies or programs. For instance, research might be designed to study the effectiveness of safety programs implemented in schools for installing car seats or fitting bicycle helmets. Do children who have been exposed to the safety programs wear their helmets? Do parents use car seats properly? If not, why not?

Research Methods

We have just learned about some of the various models and objectives of research in lifespan development. Now we’ll dig deeper to understand the methods and techniques used to describe, explain, or evaluate behavior.

All types of research methods have unique strengths and weaknesses, and each method may only be appropriate for certain types of research questions. For example, studies that rely primarily on observation produce incredible amounts of information, but the ability to apply this information to the larger population is somewhat limited because of small sample sizes. Survey research, on the other hand, allows researchers to easily collect data from relatively large samples. While this allows for results to be generalized to the larger population more easily, the information that can be collected on any given survey is somewhat limited and subject to problems associated with any type of self-reported data. Some researchers conduct archival research by using existing records. While this can be a fairly inexpensive way to collect data that can provide insight into a number of research questions, researchers using this approach have no control over how or what kind of data was collected.

Types of Descriptive Research

Observation.

Observational studies , also called naturalistic observation, involve watching and recording the actions of participants. This may take place in the natural setting, such as observing children at play in a park, or behind a one-way glass while children are at play in a laboratory playroom. The researcher may follow a checklist and record the frequency and duration of events (perhaps how many conflicts occur among 2-year-olds) or may observe and record as much as possible about an event as a participant (such as attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and recording the slogans on the walls, the structure of the meeting, the expressions commonly used, etc.). The researcher may be a participant or a non-participant. What would be the strengths of being a participant? What would be the weaknesses?

In general, observational studies have the strength of allowing the researcher to see how people behave rather than relying on self-report. One weakness of self-report studies is that what people do and what they say they do are often very different. A major weakness of observational studies is that they do not allow the researcher to explain causal relationships. Yet, observational studies are useful and widely used when studying children. It is important to remember that most people tend to change their behavior when they know they are being watched (known as the Hawthorne effect ) and children may not survey well.

Case Studies

Case studies involve exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Information may be gathered with the use of observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation. Case studies are helpful when investigating unusual situations such as brain trauma or children reared in isolation. And they are often used by clinicians who conduct case studies as part of their normal practice when gathering information about a client or patient coming in for treatment. Case studies can be used to explore areas about which little is known and can provide rich detail about situations or conditions. However, the findings from case studies cannot be generalized or applied to larger populations; this is because cases are not randomly selected and no control group is used for comparison. (Read The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat by Dr. Oliver Sacks as a good example of the case study approach.)

Surveys are familiar to most people because they are so widely used. Surveys enhance accessibility to subjects because they can be conducted in person, over the phone, through the mail, or online. A survey involves asking a standard set of questions to a group of subjects. In a highly structured survey, subjects are forced to choose from a response set such as “strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, strongly agree”; or “0, 1-5, 6-10, etc.” Surveys are commonly used by sociologists, marketing researchers, political scientists, therapists, and others to gather information on many variables in a relatively short period of time. Surveys typically yield surface information on a wide variety of factors, but may not allow for an in-depth understanding of human behavior.

Surveys are useful in examining stated values, attitudes, opinions, and reporting on practices. However, they are based on self-report, or what people say they do rather than on observation, and this can limit accuracy. Validity refers to accuracy and reliability refers to consistency in responses to tests and other measures; great care is taken to ensure the validity and reliability of surveys.

Content Analysis

Content analysis involves looking at media such as old texts, pictures, commercials, lyrics, or other materials to explore patterns or themes in culture. An example of content analysis is the classic history of childhood by Aries (1962) called “Centuries of Childhood” or the analysis of television commercials for sexual or violent content or for ageism. Passages in text or television programs can be randomly selected for analysis as well. Again, one advantage of analyzing work such as this is that the researcher does not have to go through the time and expense of finding respondents, but the researcher cannot know how accurately the media reflects the actions and sentiments of the population.

Secondary content analysis, or archival research, involves analyzing information that has already been collected or examining documents or media to uncover attitudes, practices, or preferences. There are a number of data sets available to those who wish to conduct this type of research. The researcher conducting secondary analysis does not have to recruit subjects but does need to know the quality of the information collected in the original study. And unfortunately, the researcher is limited to the questions asked and data collected originally.

Correlational and Experimental Research

Correlational research.

When scientists passively observe and measure phenomena it is called correlational research . Here, researchers do not intervene and change behavior, as they do in experiments. In correlational research, the goal is to identify patterns of relationships, but not cause and effect. Importantly, with correlational research, you can examine only two variables at a time, no more and no less.

So, what if you wanted to test whether spending money on others is related to happiness, but you don’t have $20 to give to each participant in order to have them spend it for your experiment? You could use a correlational design—which is exactly what Professor Elizabeth Dunn (2008) at the University of British Columbia did when she conducted research on spending and happiness. She asked people how much of their income they spent on others or donated to charity, and later she asked them how happy they were. Do you think these two variables were related? Yes, they were! The more money people reported spending on others, the happier they were.

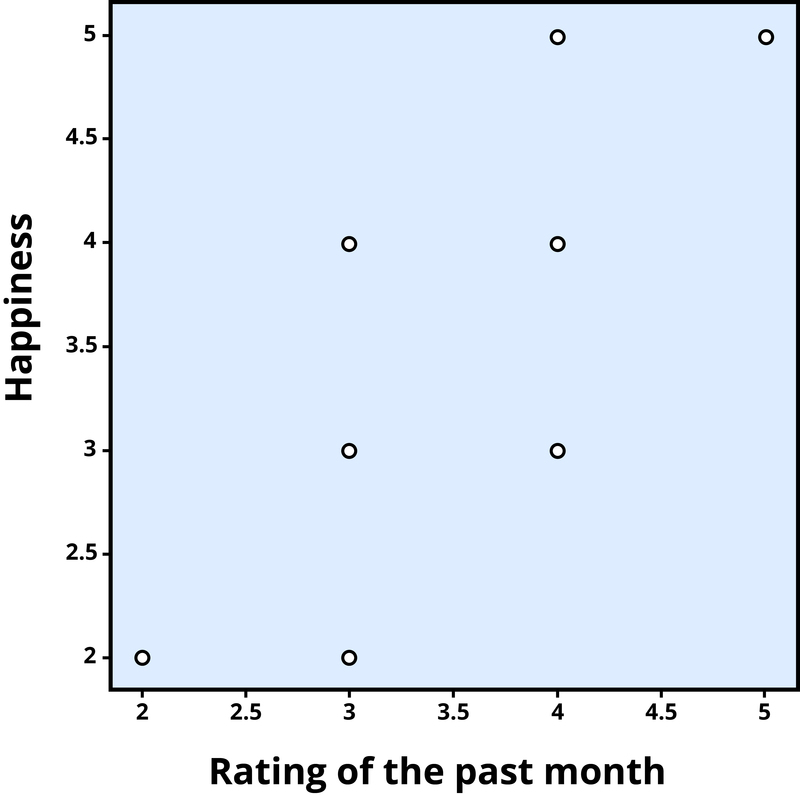

Understanding Correlation

With a positive correlation , the two variables go up or down together. In a scatterplot, the dots form a pattern that extends from the bottom left to the upper right (just as they do in Figure 1). The r value for a positive correlation is indicated by a positive number (although, the positive sign is usually omitted). Here, the r value is .81. For the example above, the direction of the association is positive. This means that people who perceived the past month as being good reported feeling happier, whereas people who perceived the month as being bad reported feeling less happy.

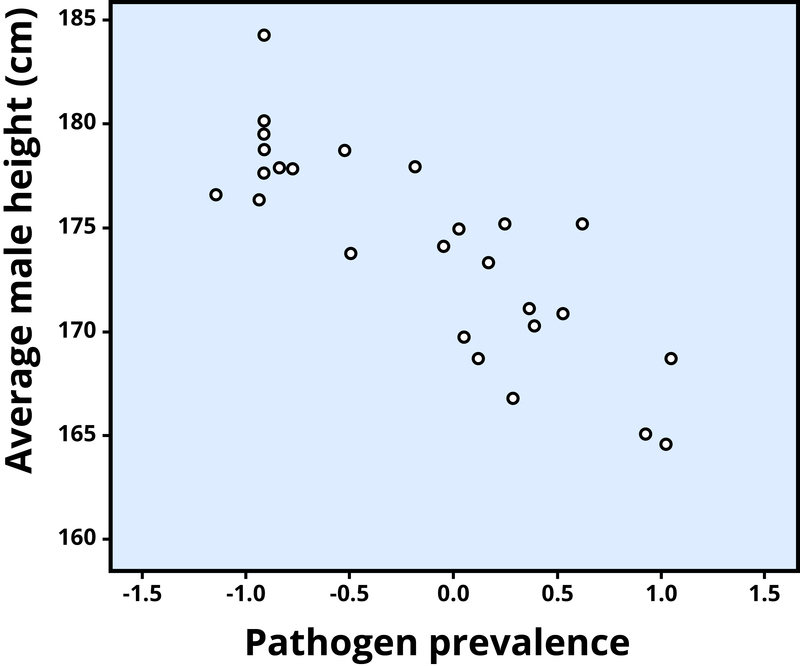

A negative correlation is one in which the two variables move in opposite directions. That is, as one variable goes up, the other goes down. Figure 2 shows the association between the average height of males in a country (y-axis) and the pathogen prevalence (or commonness of disease; x-axis) of that country. In this scatterplot, each dot represents a country. Notice how the dots extend from the top left to the bottom right. What does this mean in real-world terms? It means that people are shorter in parts of the world where there is more disease. The r-value for a negative correlation is indicated by a negative number—that is, it has a minus (–) sign in front of it. Here, it is –.83.

Experimental Research

Experiments are designed to test hypotheses (or specific statements about the relationship between variables ) in a controlled setting in an effort to explain how certain factors or events produce outcomes. A variable is anything that changes in value. Concepts are operationalized or transformed into variables in research which means that the researcher must specify exactly what is going to be measured in the study. For example, if we are interested in studying marital satisfaction, we have to specify what marital satisfaction really means or what we are going to use as an indicator of marital satisfaction. What is something measurable that would indicate some level of marital satisfaction? Would it be the amount of time couples spend together each day? Or eye contact during a discussion about money? Or maybe a subject’s score on a marital satisfaction scale? Each of these is measurable but these may not be equally valid or accurate indicators of marital satisfaction. What do you think? These are the kinds of considerations researchers must make when working through the design.

The experimental method is the only research method that can measure cause and effect relationships between variables. Three conditions must be met in order to establish cause and effect. Experimental designs are useful in meeting these conditions:

- The independent and dependent variables must be related. In other words, when one is altered, the other changes in response. The independent variable is something altered or introduced by the researcher; sometimes thought of as the treatment or intervention. The dependent variable is the outcome or the factor affected by the introduction of the independent variable; the dependent variable depends on the independent variable. For example, if we are looking at the impact of exercise on stress levels, the independent variable would be exercise; the dependent variable would be stress.

- The cause must come before the effect. Experiments measure subjects on the dependent variable before exposing them to the independent variable (establishing a baseline). So we would measure the subjects’ level of stress before introducing exercise and then again after the exercise to see if there has been a change in stress levels. (Observational and survey research does not always allow us to look at the timing of these events which makes understanding causality problematic with these methods.)

- The cause must be isolated. The researcher must ensure that no outside, perhaps unknown variables, are actually causing the effect we see. The experimental design helps make this possible. In an experiment, we would make sure that our subjects’ diets were held constant throughout the exercise program. Otherwise, the diet might really be creating a change in stress level rather than exercise.

A basic experimental design involves beginning with a sample (or subset of a population) and randomly assigning subjects to one of two groups: the experimental group or the control group . Ideally, to prevent bias, the participants would be blind to their condition (not aware of which group they are in) and the researchers would also be blind to each participant’s condition (referred to as “ double blind “). The experimental group is the group that is going to be exposed to an independent variable or condition the researcher is introducing as a potential cause of an event. The control group is going to be used for comparison and is going to have the same experience as the experimental group but will not be exposed to the independent variable. This helps address the placebo effect, which is that a group may expect changes to happen just by participating. After exposing the experimental group to the independent variable, the two groups are measured again to see if a change has occurred. If so, we are in a better position to suggest that the independent variable caused the change in the dependent variable . The basic experimental model looks like this:

The major advantage of the experimental design is that of helping to establish cause and effect relationships. A disadvantage of this design is the difficulty of translating much of what concerns us about human behavior into a laboratory setting.

Developmental Research Designs

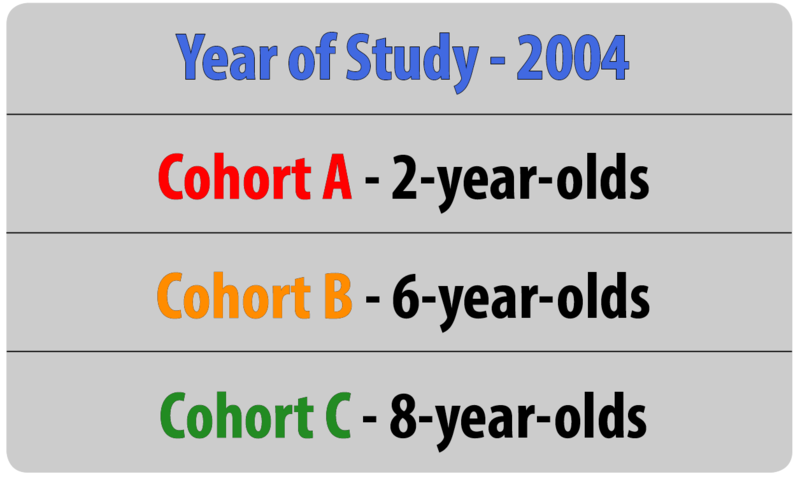

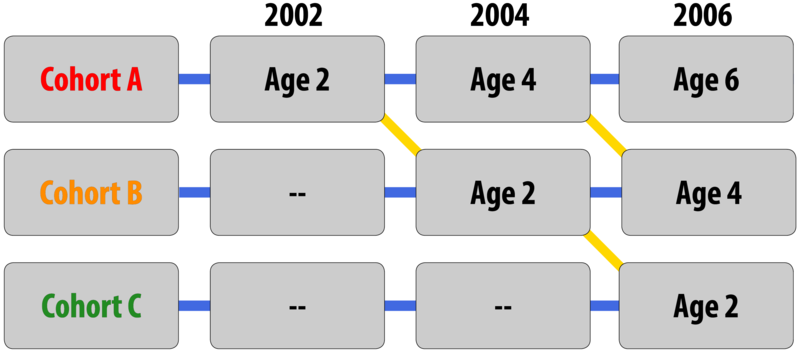

Now you know about some tools used to conduct research about human development. Remember, research methods are tools that are used to collect information. But it is easy to confuse research methods and research design. Research design is the strategy or blueprint for deciding how to collect and analyze information. Research design dictates which methods are used and how. Developmental research designs are techniques used particularly in lifespan development research. When we are trying to describe development and change, the research designs become especially important because we are interested in what changes and what stays the same with age. These techniques try to examine how age, cohort, gender, and social class impact development.

Cross-sectional designs

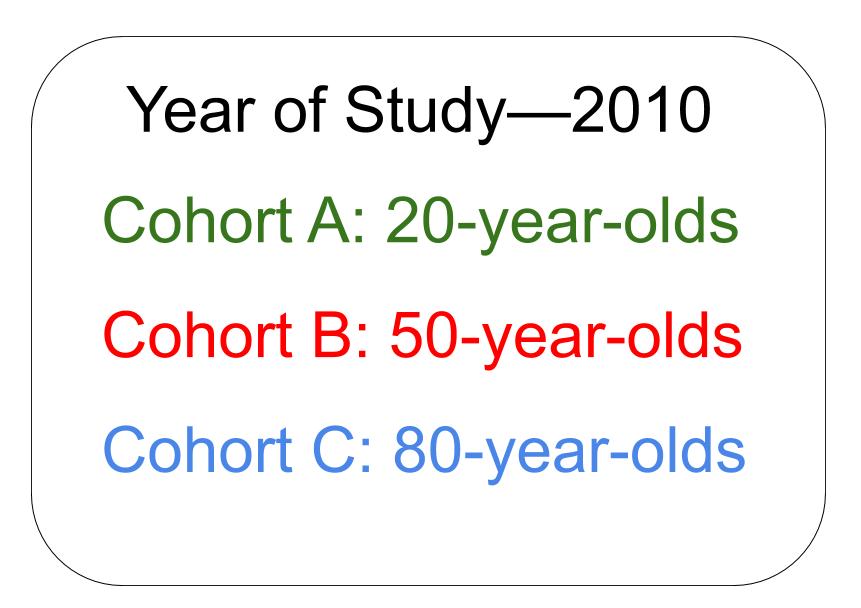

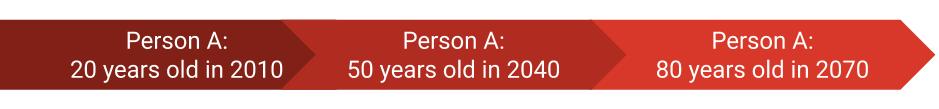

The majority of developmental studies use cross-sectional designs because they are less time-consuming and less expensive than other developmental designs. Cross-sectional research designs are used to examine behavior in participants of different ages who are tested at the same point in time. Let’s suppose that researchers are interested in the relationship between intelligence and aging. They might have a hypothesis (an educated guess, based on theory or observations) that intelligence declines as people get older. The researchers might choose to give a certain intelligence test to individuals who are 20 years old, individuals who are 50 years old, and individuals who are 80 years old at the same time and compare the data from each age group. This research is cross-sectional in design because the researchers plan to examine the intelligence scores of individuals of different ages within the same study at the same time; they are taking a “cross-section” of people at one point in time. Let’s say that the comparisons find that the 80-year-old adults score lower on the intelligence test than the 50-year-old adults, and the 50-year-old adults score lower on the intelligence test than the 20-year-old adults. Based on these data, the researchers might conclude that individuals become less intelligent as they get older. Would that be a valid (accurate) interpretation of the results?

No, that would not be a valid conclusion because the researchers did not follow individuals as they aged from 20 to 50 to 80 years old. One of the primary limitations of cross-sectional research is that the results yield information about age differences not necessarily changes with age or over time. That is, although the study described above can show that in 2010, the 80-year-olds scored lower on the intelligence test than the 50-year-olds, and the 50-year-olds scored lower on the intelligence test than the 20-year-olds, the data used to come up with this conclusion were collected from different individuals (or groups of individuals). It could be, for instance, that when these 20-year-olds get older (50 and eventually 80), they will still score just as high on the intelligence test as they did at age 20. In a similar way, maybe the 80-year-olds would have scored relatively low on the intelligence test even at ages 50 and 20; the researchers don’t know for certain because they did not follow the same individuals as they got older.

It is also possible that the differences found between the age groups are not due to age, per se, but due to cohort effects. The 80-year-olds in this 2010 research grew up during a particular time and experienced certain events as a group. They were born in 1930 and are part of the Traditional or Silent Generation. The 50-year-olds were born in 1960 and are members of the Baby Boomer cohort. The 20-year-olds were born in 1990 and are part of the Millennial or Gen Y Generation. What kinds of things did each of these cohorts experience that the others did not experience or at least not in the same ways?

You may have come up with many differences between these cohorts’ experiences, such as living through certain wars, political and social movements, economic conditions, advances in technology, changes in health and nutrition standards, etc. There may be particular cohort differences that could especially influence their performance on intelligence tests, such as education level and use of computers. That is, many of those born in 1930 probably did not complete high school; those born in 1960 may have high school degrees, on average, but the majority did not attain college degrees; the young adults are probably current college students. And this is not even considering additional factors such as gender, race, or socioeconomic status. The young adults are used to taking tests on computers, but the members of the other two cohorts did not grow up with computers and may not be as comfortable if the intelligence test is administered on computers. These factors could have been a factor in the research results.

Another disadvantage of cross-sectional research is that it is limited to one time of measurement. Data are collected at one point in time and it’s possible that something could have happened in that year in history that affected all of the participants, although possibly each cohort may have been affected differently. Just think about the mindsets of participants in research that was conducted in the United States right after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

Longitudinal research designs

Longitudinal research involves beginning with a group of people who may be of the same age and background (cohort) and measuring them repeatedly over a long period of time. One of the benefits of this type of research is that people can be followed through time and be compared with themselves when they were younger; therefore changes with age over time are measured. What would be the advantages and disadvantages of longitudinal research? Problems with this type of research include being expensive, taking a long time, and subjects dropping out over time. Think about the film, 63 Up , part of the Up Series mentioned earlier, which is an example of following individuals over time. In the videos, filmed every seven years, you see how people change physically, emotionally, and socially through time; and some remain the same in certain ways, too. But many of the participants really disliked being part of the project and repeatedly threatened to quit; one disappeared for several years; another died before her 63rd year. Would you want to be interviewed every seven years? Would you want to have it made public for all to watch?