- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

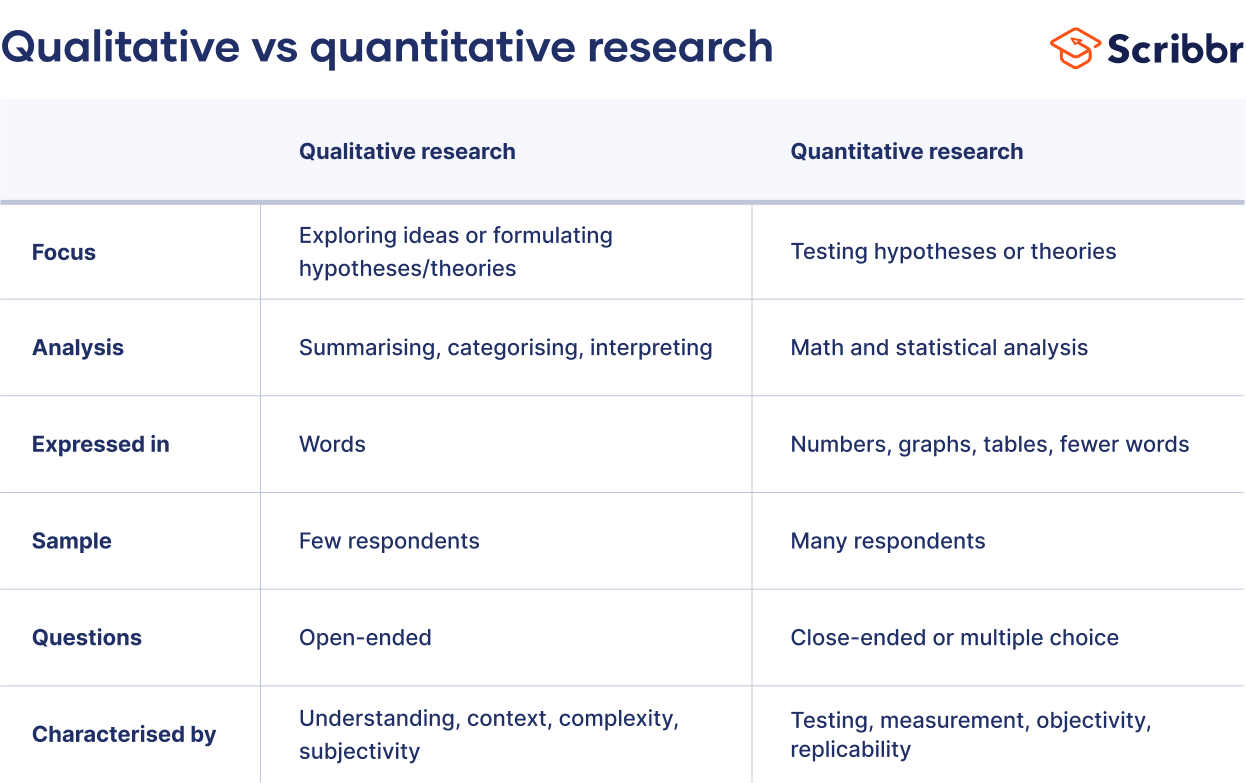

Qualitative and Quantitative Research: Differences and Similarities

Qualitative research and quantitative research are two complementary approaches for understanding the world around us.

Qualitative research collects non-numerical data , and the results are typically presented as written descriptions, photographs, videos, and/or sound recordings.

In contrast, quantitative research collects numerical data , and the results are typically presented in tables, graphs, and charts.

Debates about whether to use qualitative or quantitative research methods are common in the social sciences (i.e. anthropology, archaeology, economics, geography, history, law, linguistics, politics, psychology, sociology), which aim to understand a broad range of human conditions. Qualitative observations may be used to gain an understanding of unique situations, which may lead to quantitative research that aims to find commonalities.

Within the natural and physical sciences (i.e. physics, chemistry, geology, biology), qualitative observations often lead to a plethora of quantitative studies. For example, unusual observations through a microscope or telescope can immediately lead to counting and measuring. In other situations, meaningful numbers cannot immediately be obtained, and the qualitative research must stand on its own (e.g. The patient presented with an abnormally enlarged spleen (Figure 1), and complained of pain in the left shoulder.)

For both qualitative and quantitative research, the researcher's assumptions shape the direction of the study and thereby influence the results that can be obtained. Let's consider some prominent examples of qualitative and quantitative research, and how these two methods can complement each other.

Qualitative research example

In 1960, Jane Goodall started her decades-long study of chimpanzees in the wild at Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania. Her work is an example of qualitative research that has fundamentally changed our understanding of non-human primates, and has influenced our understanding of other animals, their abilities, and their social interactions.

Dr. Goodall was by no means the first person to study non-human primates, but she took a highly unusual approach in her research. For example, she named individual chimpanzees instead of numbering them, and used terms such as "childhood", "adolescence", "motivation", "excitement", and "mood". She also described the distinct "personalities" of individual chimpanzees. Dr. Goodall was heavily criticized for describing chimpanzees in ways that are regularly used to describe humans, which perfectly illustrates how the assumptions of the researcher can heavily influence their work.

The quality of qualitative research is largely determined by the researcher's ability, knowledge, creativity, and interpretation of the results. One of the hallmarks of good qualitative research is that nothing is predefined or taken for granted, and that the study subjects teach the researcher about their lives. As a result, qualitative research studies evolve over time, and the focus or techniques used can shift as the study progresses.

Qualitative research methods

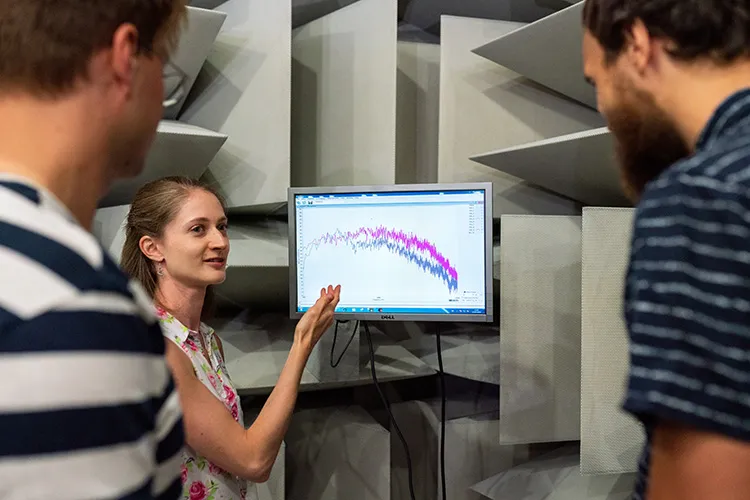

Dr. Goodall immersed herself in the chimpanzees' natural surroundings, and used direct observation to learn about their daily life. She used photographs, videos, sound recordings, and written descriptions to present her data. These are all well-established methods of qualitative research, with direct observation within the natural setting considered a gold standard. These methods are time-intensive for the researcher (and therefore monetarily expensive) and limit the number of individuals that can be studied at one time.

When studying humans, a wider variety of research methods are available to understand how people perceive and navigate their world—past or present. These techniques include: in-depth interviews (e.g. Can you discuss your experience of growing up in the Deep South in the 1950s?), open-ended survey questions (e.g. What do you enjoy most about being part of the Church of Latter Day Saints?), focus group discussions, researcher participation (e.g. in military training), review of written documents (e.g. social media accounts, diaries, school records, etc), and analysis of cultural records (e.g. anything left behind including trash, clothing, buildings, etc).

Qualitative research can lead to quantitative research

Qualitative research is largely exploratory. The goal is to gain a better understanding of an unknown situation. Qualitative research in humans may lead to a better understanding of underlying reasons, opinions, motivations, experiences, etc. The information generated through qualitative research can provide new hypotheses to test through quantitative research. Quantitative research studies are typically more focused and less exploratory, involve a larger sample size, and by definition produce numerical data.

Dr. Goodall's qualitative research clearly established periods of childhood and adolescence in chimpanzees. Quantitative studies could better characterize these time periods, for example by recording the amount of time individual chimpanzees spend with their mothers, with peers, or alone each day during childhood compared to adolescence.

For studies involving humans, quantitative data might be collected through a questionnaire with a limited number of answers (e.g. If you were being bullied, what is the likelihood that you would tell at least one parent? A) Very likely, B) Somewhat likely, C) Somewhat unlikely, D) Unlikely).

Quantitative research example

One of the most influential examples of quantitative research began with a simple qualitative observation: Some peas are round, and other peas are wrinkled. Gregor Mendel was not the first to make this observation, but he was the first to carry out rigorous quantitative experiments to better understand this characteristic of garden peas.

As described in his 1865 research paper, Mendel carried out carefully controlled genetic crosses and counted thousands of resulting peas. He discovered that the ratio of round peas to wrinkled peas matched the ratio expected if pea shape were determined by two copies of a gene for pea shape, one inherited from each parent. These experiments and calculations became the foundation of modern genetics, and Mendel's ratios became the default hypothesis for experiments involving thousands of different genes in hundreds of different organisms.

The quality of quantitative research is largely determined by the researcher's ability to design a feasible experiment, that will provide clear evidence to support or refute the working hypothesis. The hallmarks of good quantitative research include: a study that can be replicated by an independent group and produce similar results, a sample population that is representative of the population under study, a sample size that is large enough to reveal any expected statistical significance.

Quantitative research methods

The basic methods of quantitative research involve measuring or counting things (size, weight, distance, offspring, light intensity, participants, number of times a specific phrase is used, etc). In the social sciences especially, responses are often be split into somewhat arbitrary categories (e.g. How much time do you spend on social media during a typical weekday? A) 0-15 min, B) 15-30 min, C) 30-60 min, D) 1-2 hrs, E) more than 2 hrs).

These quantitative data can be displayed in a table, graph, or chart, and grouped in ways that highlight patterns and relationships. The quantitative data should also be subjected to mathematical and statistical analysis. To reveal overall trends, the average (or most common survey answer) and standard deviation can be determined for different groups (e.g. with treatment A and without treatment B).

Typically, the most important result from a quantitative experiment is the test of statistical significance. There are many different methods for determining statistical significance (e.g. t-test, chi square test, ANOVA, etc.), and the appropriate method will depend on the specific experiment.

Statistical significance provides an answer to the question: What is the probably that the difference observed between two groups is due to chance alone, and the two groups are actually the same? For example, your initial results might show that 32% of Friday grocery shoppers buy alcohol, while only 16% of Monday grocery shoppers buy alcohol. If this result reflects a true difference between Friday shoppers and Monday shoppers, grocery store managers might want to offer Friday specials to increase sales.

After the appropriate statistical test is conducted (which incorporates sample size and other variables), the probability that the observed difference is due to chance alone might be more than 5%, or less than 5%. If the probability is less than 5%, the convention is that the result is considered statistically significant. (The researcher is also likely to cheer and have at least a small celebration.) Otherwise, the result is considered statistically insignificant. (If the value is close to 5%, the researcher may try to group the data in different ways to achieve statistical significance. For example, by comparing alcohol sales after 5pm on Friday and Monday.) While it is important to reveal differences that may not be immediately obvious, the desire to manipulate information until it becomes statistically significant can also contribute to bias in research.

So how often do results from two groups that are actually the same give a probability of less than 5%? A bit less than 5% of the time (by definition). This is one of the reasons why it is so important that quantitative research can be replicated by different groups.

Which research method should I choose?

Choose the research methods that will allow you to produce the best results for a meaningful question, while acknowledging any unknowns and controlling for any bias. In many situations, this will involve a mixed methods approach. Qualitative research may allow you to learn about a poorly understood topic, and then quantitative research may allow you to obtain results that can be subjected to rigorous statistical tests to find true and meaningful patterns. Many different approaches are required to understand the complex world around us.

Related Posts

Creating an Online Course for Your Students: Everything That You Need to Know

6 Steps to Mastering the Theoretical Framework of a Dissertation

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

Qualitative vs Quantitative research: Similarities, differences, pros, and cons

Amirah Khan • 2023-05-15

Qualitative and quantitative research are two popular approaches to data collection and analysis. Both are essential research approaches that are utilised across disciplines, including psychology, business, user research, computer science, and more. In this article, we’ll share the key features, research methods, pros and cons, and use cases of qualitative and quantitative research.

What is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research aims to use non-numerical data to understand, explore, and interpret the way people think, behaviour, and feel. This includes examining experiences, attitudes, and beliefs that exist in our subjective social reality. Qualitative research uses descriptive data to draw rich, in-depth insights into problems, topics, and phenomena. This kind of research focuses on making sense of the subjective, dynamic, and evolving nature of real life. Using this research approach, it is possible to generate new ideas for research, including hypotheses and theories that are rooted in natural settings.

Key Features

Non-Numerical Data: Qualitative data focuses on rich, subjective sources of information including images, videos, text, and audio. This could be documents, observation notes, interview transcripts, audio recordings, video interviews, diaries, personal logs, photographs, and many more descriptive data sources.

Inductive Reasoning: Rather than test existing theories and hypotheses, qualitative research aims to generate new ideas for research. The goal is to take a bottom-up approach and extract rich, in-depth meaning from a specific dataset. Researchers examine unique experiences and aim to draw out common themes or categories to make sense of the topic at hand.

Flexible Research Design: Qualitative research studies have a flexible and emergent design that is data-driven. The research design, including the methods of data collection and analysis, can change throughout the study as findings emerge. This allows the design to develop alongside the study, as long as the research question is answered.

Qualitative Researchers: Due to the subjective nature of qualitative research, the qualitative researchers are considered instruments in the process. This is because their beliefs, attitudes, personal characteristics, and experiences can influence the interpretive data collection and analysis process.

Small Scale: Qualitative research methods can be time-consuming, and the subject matter can sometimes be very specific to a certain group of people. This means qualitative research often features a small sample of participants to be observed, interviewed, or given questionnaires.

Open-Ended Questions: To gather the rich, in-depth data needed for qualitative research, open-ended questions are used throughout the research methods. These kinds of questions allow participants to answer how they want in detail, rather than having to select from a limited range of pre-determined answers.

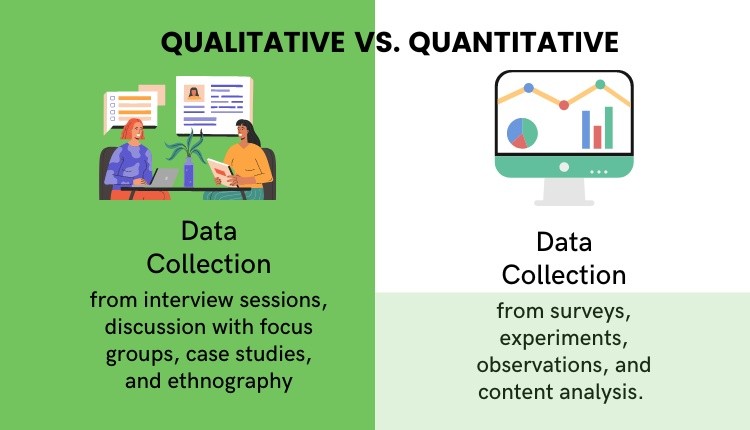

Qualitative Research Methods

For qualitative research, there are five common research methods used for data collection. Researchers often use multiple methods collect data and this depends on their chosen research approach:

Surveys can often be a time-saving, complementary method of data collection. Researchers can collect data using questionnaires with open-ended questions. These can be distributed online or in-person and allows participants to provide detailed responses in their own time.

In-depth interviews are used to collect in-depth insights into a person’s perspective on a problem, event, or topic. Researchers ask open-ended questions in a one-to-one conversation, and can deep-dive into the participants' answers with follow-up questions.

Focus groups are ideal for collecting data from multiple participants in the form of a group discussion. Researchers generate and facilitate discussion using open-ended questions. This research method is good for understanding complex social topics, and examining beliefs and opinions.

Observations occur when researchers go out into natural settings of interest to create records of what they saw, heard, or encountered. This is documented in detailed field notes, and focuses on understanding how people behave.

Secondary data involves using existing data, such as documents, photos, and videos to conduct qualitative research. This can be a more efficient way to approach a research topic, rather than collecting new data.

Pros and Cons of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research produces rich, in-depth insights into problems, issues, and phenomena. The research findings are often full of meaning that explore the ‘why’, ‘how’, and ‘what’ behind processes, behaviours, thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and experiences. This is something that can be hard to obtain from quantitative research. Qualitative research also focuses on real-life settings and people, which can provide a more accurate representation than laboratory based experiments. Finally, the inductive approach of qualitative research allows for new possibilities to be discovered and explored.

However, the subjective nature of qualitative research makes it hard to replicate. Researchers are also key instruments in the process which further reduces replicability. This limits how reliable qualitative findings are, Qualitative research can also be time-consuming, especially during data analysis. Despite using a small sample, there’s often large amounts of data to prepare and analyse. These smaller samples can also make it harder for researchers to generalise their findings beyond their current participants.

When to use Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is ideal if you want to:

- Extract rich, in-depth, and meaningful insights into problems and topics

- Understand how people perceive their own experiences

- Explore a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviours

- Gain insight into social realities of specific individuals, groups, and cultures

- Examine controversial social issues and topics

- Generate new research ideas and possibilities

- Learn about attitudes, beliefs, and opinions

Qualitative Research Questions

- Why are customers unsatisfied with their new product?

- How do teachers feel about students using artificial intelligence?

- What are teenagers' experiences of para-social relationships with influencers?

What is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research focuses on testing hypotheses and theories using numerical data. The aim is to use maths, statistics, and deductive logic to establish facts about behaviour or a phenomena of interest. This type of research aims to understand and measure the causal or correlational relationships between quantifiable variables. Quantitative research data can be transformed into useful graphs and tables using statistics.

Specifically, descriptive statistics are used to summarise data, and describe the relationships or connections between variables. Inferential statistics establish the statistical significance of the given groups of data. For this reason, quantitative research requires a large sample of participants, and a carefully planned research design. This is important for conducting statistical analyses that are reliable and generalisable.

Here are the key features of quantitative research that contrast with the features of qualitative research:

Numerical Data : Quantitative data focuses on variables that can be quantified, measured, and analysed through statistics. This data, which is rooted in numbers and maths, can be displayed using graphs and tables.

Deductive Reasoning: Quantitative research aims to test whether existing theories, hypotheses, or observations can hold up in specific conditions. This allows researchers to determine whether a theory or hypotheses should be confirmed or rejected for that particular condition.

Fixed Research Design: Quantitative research follows a structured process that is well-established. The research design, including the research questions, research methods, and data analysis techniques are often decided at the beginning and rarely changed during the study.

Quantitative Researchers: For quantitative researchers, their approach to the world is objective, and focuses on the quantifiable, measurable aspects of reality. Their goal is to remain as objective as possible and produce results that can be generalised beyond the specific environment of the study.

Large Scale: Statistical analyses require a large amount of data to produce significant and reliable results. For this reason, quantitative research often involves a large sample of participants. This larger sample allows results to be generalised and enables researchers to account for erroneous data.

Close-ended Questions: Quantitative data collection methods use close-ended questions to collect quantifiable, measurable data. Close-ended questions have predetermined responses for people to pick from. This can include yes/no questions, multiple-choice answers, and rating scales of all kinds.

Quantitative Research Methods

Experiments involve manipulating an independent variable and measuring a dependent variable. This is to examine how changes to the independent variable affect the dependent variable. Researchers can use experiments to identify cause and effect relationships between variables.

Observations are used to watch, understand, and investigate quantifiable variables. Instead of manipulating variables, this method focuses on measuring variables. For example, weight, size, and noting the number of times something occurs are measurements. Observations are used for descriptive and correlational research designs .

Surveys are a common and popular research method, also used for descriptive and correlational research designs. This method uses close-ended questions, such as multiple choice, or rating scales to collect data. Surveys can be used to understand how something changes over time, or to get a snapshot of the current moment.

Pros and Cons of Quantitative Research

Quantitative research follows structured, unambiguous, standardised processes that can be easily replicated. This improves the reliability of the study, allowing it to be replicated and proven using the same approach. Unlike qualitative research, quantitative research can be both quick and scientifically objective. Researchers can study phenomena in a timely manner, and utilise sophisticated softwares for rapid, statistical analyses. This allows researchers to process large amounts of data in an efficient way, and produce findings that are generalisable.

If researchers are unable to obtain an adequate sample size, or end up with data that cannot be used, this limits the accuracy and generalisability of the findings. Researchers also require statistical expertise in order to conduct statistical analyses in an accurate manner. Finally, quantitative research can lack meaning and be subject to confirmation bias. That is, researchers can miss emerging phenomena because they are focused on testing a theory of hypothesis.

When to use Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research is best used when you want to:

- Measure or quantify data

- Establish trends and relationships between variables

- Test existing hypotheses and theories

- Describe and predict casual relationships

- Investigate correlational relationships

- Understand the characteristics of a population or phenomena

- Produce visual displays of information, such as graphs or tables

Quantitative Research Questions

- What are the demographics of my target audience on social media?

- How satisfied are customers with my products and services?

- Can mindfulness improve a student's ability to recall information?

See More Posts

Copyright © 2021 Govest, Inc. All rights reserved.

[email protected]

Terms of Service

Privacy Policy

- Qualitative vs Quantitative Data:15 Differences & Similarities

- Data Collection

Research and statistics are two important things that are not mutually exclusive as they go hand in hand in most cases. The role of statistics in research is to function as a tool in designing research, analysing data and drawing conclusions from there.

On the other hand, the basis of statistics is data, making most research studies result in large volumes of data. This data is measured, collected and reported, and analysed (making it information), whereupon it can be visualised using graphs, images or other analysis tools

In this article, we will be discussing data, a very important aspect of statistics and research. We will be touching on its meaning, types and working with them in research and statistics.

What is Data?

Data is a group of raw facts or information collected for research, reference or analysis. They are individual units of information that has been transformed into an efficient form, for easy movement and/or processing.

The plural of the word Datum, which describes a single quantity or quality of an object or phenomenon. It is applicable in different fields of research, business and statistics.

In the case of data analysis, we define it as the process of inspecting, editing, transforming and modelling data to discover useful information, informing conclusion and supporting decision-making. An important part of performing data analysis is knowing the different types of data we have.

There are two types of data, namely; quantitative and qualitative data;

What is Quantitative Data?

Quantitative data is the type of data whose value is measured in the form of numbers or counts, with a unique numerical value associated with each data set. Also known as Numerical data , this data type describes numeric variables.

It has various uses in research and most especially statistics because of its compatibility with most statistical analysis methods. There are different methods of analysing quantitative data depending on its type.

Quantitative data is divided into two types , namely; discrete data and continuous data. Continuous data is then further divided into interval data and ratio data.

What is Qualitative Data?

Qualitative data is the type of data that describes information. Its is a descriptive statistical data type, making it a data that is expressed with groups and categories rather than numbers.

It is also known as categorical data . This data type is relevant to a large extent in research with limited use in statistics due to its incompatibility with most statistical methods.

Qualitative data is divided into two categories, namely; nominal data and ordinal data . Nominal data names or define variables while ordinal data scales them.

Here are the 15 Key differences between quantitative & qualitative data;

- Definitions

Quantitative data is a group of quantifiable information that can be used for mathematical computations and statistical analysis which informs real-life decisions while qualitative data is a group of data that describes information.

Quantitative data is a combination of numeric values which depict relevant information. Qualitative data, on the other hand, uses descriptive approach towards expressing information.

- Another name

Quantitative data is also known as numerical data while qualitative data is also known as categorical data. This is because quantitative data are measured in the form of numbers or counts.for qualitative data, they are grouped into categories.

Quantitative data are of two types namely; discrete data and continuous data. Continuous data is further divided into interval data and ratio data.

Qualitative data, on the other hand, is also divided into two types, namely; nominal data and ordinal data. However, ordinal data is classified as quantitative in some cases.

Some examples of quantitative data include Likert scale, interval sale etc. The Likert scale is a commonly used example of ordinal data and is of different types — 5 point to 7-point Likert scale .

Some qualitative data examples include name, gender, phone number etc. This data can be collected through open-ended questions, multiple-choice or closed open-ended questions.

- Characteristics

The characteristics of quantitative data include the following; it takes the numeric value with numeric properties, it has a standardised order scale, it is visualised using scatter plots, and dot plot, etc.

Qualitative data, on the other hand, may take numeric values but without numeric properties, does not have a standardised order scale And is visualised using a bar chart and pie chart.

Quantitative data analysis is grouped into two, namely; descriptive and inferential statistics. The methods include measures of central tendency, turf analysis, text analysis, conjoint analysis, trend analysis, etc.

Quantitative data analysis methods are however straightforward, where only mean and median analysis can be performed. In some cases, ordinal data analysis use univariate statistics, bivariate statistics, regression analysis etc. which are close substitutes to calculating some mean and standard deviation analysis.

During the collection of qualitative data , researchers use tools like surveys, interviews, focus groups and observations, while Qualitative data is usually collected through surveys and interviews in a few cases. For example, when calculating the average height of students in a class, the students may be interviewed on what their height is instead of measuring the heights again.

- Collection Methods

Quantitative data is collected through closed-ended methods while qualitative data uses open-ended questions, multiple-choice questions, closed-ended and closed open-ended approach. This gives qualitative data a broader collection mode.

Quantitative data is mostly used to carry out statistical calculations involving the use of arithmetic operations. Calculating the CGPA of a student, for example, will require finding the average of all grades.

Quantitative data, on the other hand, deals with descriptive information without adding or performing any operation with it. It is mainly used to collect personal information.

Quantitative data is compatible with most statistical analysis methods and as such is mostly used by researchers. Qualitative data, on the other hand, is only compatible with median and mode, making it have restricted applications.

Although, in some cases, alternative tests are carried out on ordinal data. For example, we use univariate statistics, bivariate statistics, regression analysis etc. as alternatives.

- Disadvantages :

Although very applicable in most statistical analysis, its standardised environment may limit the proper investigation. Quantitative research is strictly based on the researcher’s point of view, thus limiting freedom of expression on the respondent’s end.

This is not the case for qualitative research. Nominal data captures human emotions to an extent through open-ended questions. This may, however, cause the researcher to deal with irrelevant data.

- Question Samples: Quantitative research questions always have preset answers . This is not always the case in qualitative data.

Qualitative question example

In which of the following interval does your height fall in centimetres?

This is an interval data example .

Quantitative question example 2

Kindly enter your National identification number below.

This is a nominal data example .

- Examples: Below are some examples of quantitative data and qualitative data.

Quantitative Data Examples

- Mean height in a class

- Measurement of physical objects

- The probability of an event occurring

- Random number generation

- Calculation of student’s CGPA

Qualitative Data Examples

- Likert scale

- Data collected from a competitive analysis survey.

- Oral-job interview responses.

- Student biodata .

- Phone number

- Statistical compatibility

Quantitative data is compatible with most statistical methods, but qualitative data isn’t. This may pose issues for researchers when performing data analysis.

This is part of the reason why researchers prefer using quantitative data for research.

- User-friendliness

Quantitative data collection methods are more user-friendly compared to that of qualitative data. Although open-ended questions may give the researchers much-needed information, it may get stressful for respondents.

Respondents like spending as little time as possible filling out surveys, and when it takes time, they may abandon it.

Are there any similarities between quantitative & qualitative data?

Both quantitative and qualitative data has an order or scale to it. That is while ordinal data is sometimes classified under quantitative data. Qualitative data do not, however, have a standardised scale.

Quantitative and qualitative data are both used for research and statistical analysis. Although, through different approaches, they can both be used for the same thing. Consider two organisations investigating the purchasing power of its target audience through the method below.

Organisation A

What is your monthly income? ____

Organisation B

In which interval does your monthly income fall?

- €1000 – €5000

- €5001 – €10000

- €10001 – €15000

The first is a qualitative data collection example while the second is a quantitative data collection example.

- Quantitative Value

Both quantitative data and qualitative data takes a numeric value. Qualitative data takes numeric values like phone number, postal code, national identification number, etc. The difference, however, is that arithmetic operations cannot be performed on qualitative data.

- Collection tools

Both qualitative and quantitative data can be collected through surveys/questionnaires and interviews . Although through different approaches, they use similar tools.

When to Choose Quantitative Over Qualitative Data

The different types of data have their usefulness and advantages over the other. These advantages are why they are chosen over the other in some cases depending on the purpose of data collection. Here are some cases where quantitative data should be chosen over qualitative data.

- When conducting scientific research

Quantitative data is more suitable for scientific research due to its compatibility with most statistical analysis methods. It also has numerical properties which allow for the performance of arithmetic operations on it.

- When replicating research

Quantitative research has a standardised procedure to it. Hence, it is easy to replicate past research, build on it and even edit research procedures.

- When dealing with large data

Large data sets are best analysed using quantitative data. This is why some researchers turn qualitative data into quantitative data before analysis.

It is called the quantification of qualitative data. This way, they don’t have to be sweeping through a large string of texts for analysis.

- During laboratory-based research

Due to its standard procedure of analysis, it is the most suitable data type for laboratory analysis.

- When dealing with sensitive data

Research that involve sensitive data is best processed using quantitative data. This helps eliminate cases of bias due to familiarity or leaking sensitive information.

When to Choose Qualitative Over Quantitative Data

Although not compatible with most statistical analysis methods, qualitative data is preferable in certain cases. It is mostly preferred when collecting data for real-life research processes. Here are some cases where qualitative data should be chosen over quantitative data.

- During customer experience research

The main purpose of customer experience research is to know how customers feel about an organisation’s service and get information on what they can do to improve their service. Therefore, to achieve this, organisations need to assess human feelings and emotions. This is something that can only be done with qualitative data.

- Job interviews

Especially with this ever-changing workplace culture, recruiters are now more interested in the applicant’s attitude, emotional intelligence, etc. than the skills they have to offer. For them to properly assess these traits, qualitative data about the applicant should be collected through an interview.

- Competitive analysis

Organisations perform competitive analysis to assess their competition’s popularity and what they did to gain such popularity. Quantitative data do not give detailed information about this unlike how qualitative does.

- Security questions

Many web-based companies ask personal questions like, “What is your pet’s name?” or “What is your mother’s maiden name?” as a means of extra security on user’s account. Numbers are usually hard to memorise, which is why some people to find it difficult to memorise their phone number to date. Personal questions (qualitative data) like this is hard to forget and therefore better for security questions.

- Dating website

Dating websites collect personal Information (usually nominal data) of users to properly match them with their type.

What is the best tool to collect quantitative and qualitative data?

Formplus as a data collection tool was built with the notion that proper data collection is the first step towards efficient and reliable research. Therefore, the makers of Formplus form builder software have added necessary features to help you collect your data.

Quantitative and qualitative data is best collected with Formplus because it not only helps you collect proper data but also arrange them for analysis. You no longer have to deal with data that is difficult to read when performing data validation process.

Each data is properly matched to the corresponding variables, making it easy to identify missing or inconsistent data.

How to collect Qualitative and Quantitative Data with Formplus Survey Tools

To collect qualitative data using Formplus builder, follow these steps:

Step 1: Register or Sign up

- Visit www.formpl.us on your desktop or mobile device.

- Sign up through your Email, Google or Facebook in less than 30 seconds…

Step 2: Start Creating Forms: Formplus gives you a 21-day free trial to test all features and start collecting quantitative data from online surveys. Pricing plan starts after trial expiration at $20 monthly, with reasonable discounts for Education and Non-Governmental Organizations.

- Click on the Create form button to start creating forms for free.

- You can also click on the Upgrade Now button to upgrade to a pricing plan at $20 monthly.

Step 3: Collect Qualitative Data

We will be creating a sample qualitative data collection form that inputs name (nominal data) and happiness level (ordinal data) of a respondent.

- Edit form title and click on the input section of the form builder menu.

- The input sections let you insert features such as small texts for names, numbers, date, email, long text for general feedback. Click on the Name tab and edit in the settings

- Click on the choice options section of the form builder menu. Then, click on the Radio tab.

- the choice options let respondents choose from different options. Use Radio choice to ask your respondents to choose a single option from a shortlist.

Step 4: Collect Quantitative Data

We will be creating a sample quantitative data collection form that inputs the courses offered by a student and their score, then output their average score.

- Click on the Advanced inputs section of the builder menu, then click on the Table tab.

- Click on the Labeled Text tab in the inputs section to output the result of our quantitative data calculation.

- Click on Add Calculations in the Advanced inputs tab and use the formula Score/COUNT() to calculate the average score.

The Add Calculations tab lets you perform arithmetic operations on numerical data.

Conclusion

Qualitative and quantitative data do have their key differences and similarities, and understanding them is very important as it helps in choosing the best data type to work with. It also helps in proper identification, so as not to miscategorise data.

These two data types also have their unique advantages over the other, which is why researchers use a particular data type for research and use the other for another research. However, quantitative data remains the more popular data type when compared to qualitative data.

As we have done in this article, understanding data types are the first step towards proper usage.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- examples of primary data

- qualitative data

- qualitative data examples

- quantitative data

- quantitative qualitative data

- types of data

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

What is Primary Data? + [Examples & Collection Methods]

Ultimate guide on Primary Data, it’s meaning, collection methods, examples, advantages and disadvantage.

Primary vs Secondary Data:15 Key Differences & Similarities

Simple guide on secondary and primary data differences on examples, types, collection tools, advantages, disadvantages, sources etc.

What is Qualitative Data? + [Types, Examples]

qualitative data definitions, types; in ordinal and nominal data, examples, data analysis, interpretations, advantages and disadvantages

What is Data Interpretation? + [Types, Method & Tools]

Everything you need to know about data interpretation, visualization techniques and analysis. I.e Charts, Graphs, Tables and question examples.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Methods & Data Analysis

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

What is the difference between quantitative and qualitative?

The main difference between quantitative and qualitative research is the type of data they collect and analyze.

Quantitative research collects numerical data and analyzes it using statistical methods. The aim is to produce objective, empirical data that can be measured and expressed in numerical terms. Quantitative research is often used to test hypotheses, identify patterns, and make predictions.

Qualitative research , on the other hand, collects non-numerical data such as words, images, and sounds. The focus is on exploring subjective experiences, opinions, and attitudes, often through observation and interviews.

Qualitative research aims to produce rich and detailed descriptions of the phenomenon being studied, and to uncover new insights and meanings.

Quantitative data is information about quantities, and therefore numbers, and qualitative data is descriptive, and regards phenomenon which can be observed but not measured, such as language.

What Is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data, such as language. Qualitative research can be used to understand how an individual subjectively perceives and gives meaning to their social reality.

Qualitative data is non-numerical data, such as text, video, photographs, or audio recordings. This type of data can be collected using diary accounts or in-depth interviews and analyzed using grounded theory or thematic analysis.

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 2)

Interest in qualitative data came about as the result of the dissatisfaction of some psychologists (e.g., Carl Rogers) with the scientific study of psychologists such as behaviorists (e.g., Skinner ).

Since psychologists study people, the traditional approach to science is not seen as an appropriate way of carrying out research since it fails to capture the totality of human experience and the essence of being human. Exploring participants’ experiences is known as a phenomenological approach (re: Humanism ).

Qualitative research is primarily concerned with meaning, subjectivity, and lived experience. The goal is to understand the quality and texture of people’s experiences, how they make sense of them, and the implications for their lives.

Qualitative research aims to understand the social reality of individuals, groups, and cultures as nearly as possible as participants feel or live it. Thus, people and groups are studied in their natural setting.

Some examples of qualitative research questions are provided, such as what an experience feels like, how people talk about something, how they make sense of an experience, and how events unfold for people.

Research following a qualitative approach is exploratory and seeks to explain ‘how’ and ‘why’ a particular phenomenon, or behavior, operates as it does in a particular context. It can be used to generate hypotheses and theories from the data.

Qualitative Methods

There are different types of qualitative research methods, including diary accounts, in-depth interviews , documents, focus groups , case study research , and ethnography.

The results of qualitative methods provide a deep understanding of how people perceive their social realities and in consequence, how they act within the social world.

The researcher has several methods for collecting empirical materials, ranging from the interview to direct observation, to the analysis of artifacts, documents, and cultural records, to the use of visual materials or personal experience. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 14)

Here are some examples of qualitative data:

Interview transcripts : Verbatim records of what participants said during an interview or focus group. They allow researchers to identify common themes and patterns, and draw conclusions based on the data. Interview transcripts can also be useful in providing direct quotes and examples to support research findings.

Observations : The researcher typically takes detailed notes on what they observe, including any contextual information, nonverbal cues, or other relevant details. The resulting observational data can be analyzed to gain insights into social phenomena, such as human behavior, social interactions, and cultural practices.

Unstructured interviews : generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

Diaries or journals : Written accounts of personal experiences or reflections.

Notice that qualitative data could be much more than just words or text. Photographs, videos, sound recordings, and so on, can be considered qualitative data. Visual data can be used to understand behaviors, environments, and social interactions.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative research is endlessly creative and interpretive. The researcher does not just leave the field with mountains of empirical data and then easily write up his or her findings.

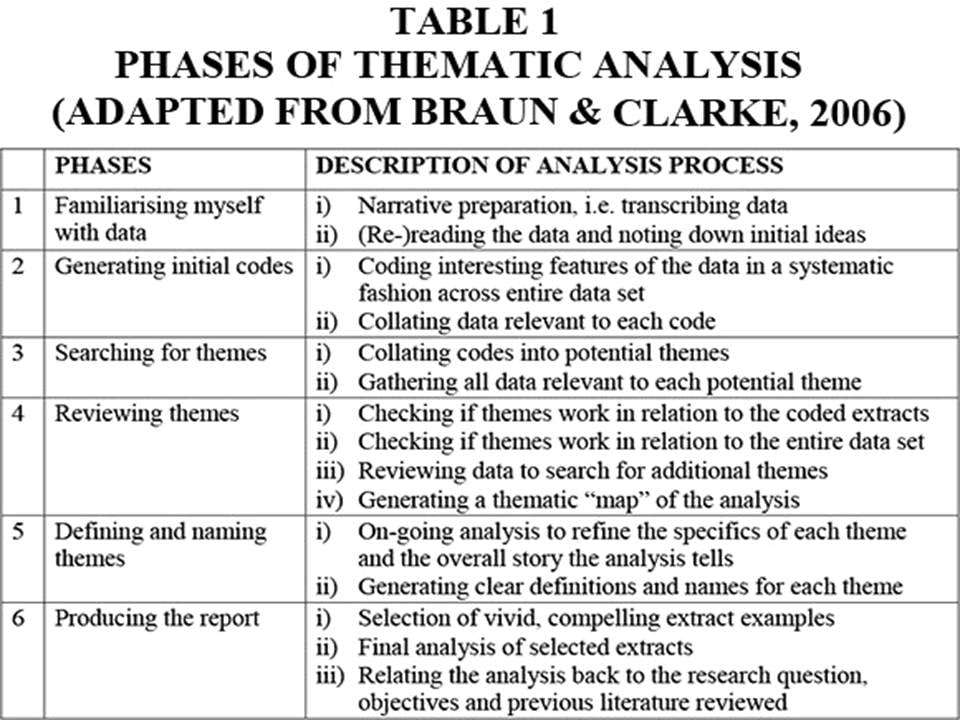

Qualitative interpretations are constructed, and various techniques can be used to make sense of the data, such as content analysis, grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), or discourse analysis.

For example, thematic analysis is a qualitative approach that involves identifying implicit or explicit ideas within the data. Themes will often emerge once the data has been coded .

Key Features

- Events can be understood adequately only if they are seen in context. Therefore, a qualitative researcher immerses her/himself in the field, in natural surroundings. The contexts of inquiry are not contrived; they are natural. Nothing is predefined or taken for granted.

- Qualitative researchers want those who are studied to speak for themselves, to provide their perspectives in words and other actions. Therefore, qualitative research is an interactive process in which the persons studied teach the researcher about their lives.

- The qualitative researcher is an integral part of the data; without the active participation of the researcher, no data exists.

- The study’s design evolves during the research and can be adjusted or changed as it progresses. For the qualitative researcher, there is no single reality. It is subjective and exists only in reference to the observer.

- The theory is data-driven and emerges as part of the research process, evolving from the data as they are collected.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Because of the time and costs involved, qualitative designs do not generally draw samples from large-scale data sets.

- The problem of adequate validity or reliability is a major criticism. Because of the subjective nature of qualitative data and its origin in single contexts, it is difficult to apply conventional standards of reliability and validity. For example, because of the central role played by the researcher in the generation of data, it is not possible to replicate qualitative studies.

- Also, contexts, situations, events, conditions, and interactions cannot be replicated to any extent, nor can generalizations be made to a wider context than the one studied with confidence.

- The time required for data collection, analysis, and interpretation is lengthy. Analysis of qualitative data is difficult, and expert knowledge of an area is necessary to interpret qualitative data. Great care must be taken when doing so, for example, looking for mental illness symptoms.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

- Because of close researcher involvement, the researcher gains an insider’s view of the field. This allows the researcher to find issues that are often missed (such as subtleties and complexities) by the scientific, more positivistic inquiries.

- Qualitative descriptions can be important in suggesting possible relationships, causes, effects, and dynamic processes.

- Qualitative analysis allows for ambiguities/contradictions in the data, which reflect social reality (Denscombe, 2010).

- Qualitative research uses a descriptive, narrative style; this research might be of particular benefit to the practitioner as she or he could turn to qualitative reports to examine forms of knowledge that might otherwise be unavailable, thereby gaining new insight.

What Is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research involves the process of objectively collecting and analyzing numerical data to describe, predict, or control variables of interest.

The goals of quantitative research are to test causal relationships between variables , make predictions, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative researchers aim to establish general laws of behavior and phenomenon across different settings/contexts. Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Quantitative Methods

Experiments typically yield quantitative data, as they are concerned with measuring things. However, other research methods, such as controlled observations and questionnaires , can produce both quantitative information.

For example, a rating scale or closed questions on a questionnaire would generate quantitative data as these produce either numerical data or data that can be put into categories (e.g., “yes,” “no” answers).

Experimental methods limit how research participants react to and express appropriate social behavior.

Findings are, therefore, likely to be context-bound and simply a reflection of the assumptions that the researcher brings to the investigation.

There are numerous examples of quantitative data in psychological research, including mental health. Here are a few examples:

Another example is the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR), a self-report questionnaire widely used to assess adult attachment styles .

The ECR provides quantitative data that can be used to assess attachment styles and predict relationship outcomes.

Neuroimaging data : Neuroimaging techniques, such as MRI and fMRI, provide quantitative data on brain structure and function.

This data can be analyzed to identify brain regions involved in specific mental processes or disorders.

For example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a clinician-administered questionnaire widely used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in individuals.

The BDI consists of 21 questions, each scored on a scale of 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Statistics help us turn quantitative data into useful information to help with decision-making. We can use statistics to summarize our data, describing patterns, relationships, and connections. Statistics can be descriptive or inferential.

Descriptive statistics help us to summarize our data. In contrast, inferential statistics are used to identify statistically significant differences between groups of data (such as intervention and control groups in a randomized control study).

- Quantitative researchers try to control extraneous variables by conducting their studies in the lab.

- The research aims for objectivity (i.e., without bias) and is separated from the data.

- The design of the study is determined before it begins.

- For the quantitative researcher, the reality is objective, exists separately from the researcher, and can be seen by anyone.

- Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Limitations of Quantitative Research

- Context: Quantitative experiments do not take place in natural settings. In addition, they do not allow participants to explain their choices or the meaning of the questions they may have for those participants (Carr, 1994).

- Researcher expertise: Poor knowledge of the application of statistical analysis may negatively affect analysis and subsequent interpretation (Black, 1999).

- Variability of data quantity: Large sample sizes are needed for more accurate analysis. Small-scale quantitative studies may be less reliable because of the low quantity of data (Denscombe, 2010). This also affects the ability to generalize study findings to wider populations.

- Confirmation bias: The researcher might miss observing phenomena because of focus on theory or hypothesis testing rather than on the theory of hypothesis generation.

Advantages of Quantitative Research

- Scientific objectivity: Quantitative data can be interpreted with statistical analysis, and since statistics are based on the principles of mathematics, the quantitative approach is viewed as scientifically objective and rational (Carr, 1994; Denscombe, 2010).

- Useful for testing and validating already constructed theories.

- Rapid analysis: Sophisticated software removes much of the need for prolonged data analysis, especially with large volumes of data involved (Antonius, 2003).

- Replication: Quantitative data is based on measured values and can be checked by others because numerical data is less open to ambiguities of interpretation.

- Hypotheses can also be tested because of statistical analysis (Antonius, 2003).

Antonius, R. (2003). Interpreting quantitative data with SPSS . Sage.

Black, T. R. (1999). Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: An integrated approach to research design, measurement and statistics . Sage.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology . Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3, 77–101.

Carr, L. T. (1994). The strengths and weaknesses of quantitative and qualitative research : what method for nursing? Journal of advanced nursing, 20(4) , 716-721.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The Good Research Guide: for small-scale social research. McGraw Hill.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln. Y. (1994). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications Inc.

Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L., & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nursing research, 17(4) , 364.

Minichiello, V. (1990). In-Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire.

Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. London: Sage

Further Information

- Designing qualitative research

- Methods of data collection and analysis

- Introduction to quantitative and qualitative research

- Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog?

- Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data

- Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach

- Using the framework method for the analysis of

- Qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research

- Content Analysis

- Grounded Theory

- Thematic Analysis

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

Published on 4 April 2022 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on 8 May 2023.

When collecting and analysing data, quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings. Both are important for gaining different kinds of knowledge.

Common quantitative methods include experiments, observations recorded as numbers, and surveys with closed-ended questions. Qualitative research Qualitative research is expressed in words . It is used to understand concepts, thoughts or experiences. This type of research enables you to gather in-depth insights on topics that are not well understood.

Table of contents

The differences between quantitative and qualitative research, data collection methods, when to use qualitative vs quantitative research, how to analyse qualitative and quantitative data, frequently asked questions about qualitative and quantitative research.

Quantitative and qualitative research use different research methods to collect and analyse data, and they allow you to answer different kinds of research questions.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Quantitative and qualitative data can be collected using various methods. It is important to use a data collection method that will help answer your research question(s).

Many data collection methods can be either qualitative or quantitative. For example, in surveys, observations or case studies , your data can be represented as numbers (e.g. using rating scales or counting frequencies) or as words (e.g. with open-ended questions or descriptions of what you observe).

However, some methods are more commonly used in one type or the other.

Quantitative data collection methods

- Surveys : List of closed or multiple choice questions that is distributed to a sample (online, in person, or over the phone).

- Experiments : Situation in which variables are controlled and manipulated to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Observations: Observing subjects in a natural environment where variables can’t be controlled.

Qualitative data collection methods

- Interviews : Asking open-ended questions verbally to respondents.

- Focus groups: Discussion among a group of people about a topic to gather opinions that can be used for further research.

- Ethnography : Participating in a community or organisation for an extended period of time to closely observe culture and behavior.

- Literature review : Survey of published works by other authors.

A rule of thumb for deciding whether to use qualitative or quantitative data is:

- Use quantitative research if you want to confirm or test something (a theory or hypothesis)

- Use qualitative research if you want to understand something (concepts, thoughts, experiences)

For most research topics you can choose a qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods approach . Which type you choose depends on, among other things, whether you’re taking an inductive vs deductive research approach ; your research question(s) ; whether you’re doing experimental , correlational , or descriptive research ; and practical considerations such as time, money, availability of data, and access to respondents.

Quantitative research approach

You survey 300 students at your university and ask them questions such as: ‘on a scale from 1-5, how satisfied are your with your professors?’

You can perform statistical analysis on the data and draw conclusions such as: ‘on average students rated their professors 4.4’.

Qualitative research approach

You conduct in-depth interviews with 15 students and ask them open-ended questions such as: ‘How satisfied are you with your studies?’, ‘What is the most positive aspect of your study program?’ and ‘What can be done to improve the study program?’

Based on the answers you get you can ask follow-up questions to clarify things. You transcribe all interviews using transcription software and try to find commonalities and patterns.

Mixed methods approach

You conduct interviews to find out how satisfied students are with their studies. Through open-ended questions you learn things you never thought about before and gain new insights. Later, you use a survey to test these insights on a larger scale.

It’s also possible to start with a survey to find out the overall trends, followed by interviews to better understand the reasons behind the trends.

Qualitative or quantitative data by itself can’t prove or demonstrate anything, but has to be analysed to show its meaning in relation to the research questions. The method of analysis differs for each type of data.

Analysing quantitative data

Quantitative data is based on numbers. Simple maths or more advanced statistical analysis is used to discover commonalities or patterns in the data. The results are often reported in graphs and tables.

Applications such as Excel, SPSS, or R can be used to calculate things like:

- Average scores

- The number of times a particular answer was given

- The correlation or causation between two or more variables

- The reliability and validity of the results

Analysing qualitative data

Qualitative data is more difficult to analyse than quantitative data. It consists of text, images or videos instead of numbers.

Some common approaches to analysing qualitative data include:

- Qualitative content analysis : Tracking the occurrence, position and meaning of words or phrases

- Thematic analysis : Closely examining the data to identify the main themes and patterns

- Discourse analysis : Studying how communication works in social contexts

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organise your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2023, May 08). Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 27 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/quantitative-qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Introduction: Considering Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Research

- First Online: 24 December 2020

Cite this chapter

- Alistair McBeath 2 &

- Sofie Bager-Charleson 2

1 Citations

In this introduction we will explore some of the differences and similarities between quantitative and qualitative research, and dispel some of the perceived mysteries within research. We will briefly introduce some of the advantages and disadvantages of both approaches. There will also be an introduction to some of the philosophical assumptions that underpin quantitative and qualitative research methods, with specific mention made of ontological and epistemological considerations. These about the nature of existence (ontology) and how we might gain knowledge about the nature of existence (epistemology). We will explore the difference between positivist and interpretivist research, idiographic versus nomothetic, and inductive and deductive perspectives. Finally, we will also distinguish between qualitative, quantitative and mixed method s research, gaining familiarity with attempts to bridge divides between disciplines and research approaches. Throughout this book, the issue of research-supported practice will remain an underlying theme. This chapter aims to support a research-based practice, aided by considering the multiple routes into research. The chapter encourages you to familiarise yourself with approaches ranging from phenomenological experiences to more nomothetic, generalising and comparing foci like outcome measuring and random control trials (RCTs), understood with a basic knowledge of statistics. The book introduces you to a range of research, guided by interest in separate approaches but also inductive—deductive combinations, as in grounded theory together with pluralistic and mixed methods approaches, all with a shared interest in providing support in the field of mental health and emotional wellbeing. Primarily, we hope that the chapter will encourage you to start considering your own research. Enjoy!

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

An Introduction to Qualitative and Mixed Methods Study Designs in Health Research

The Nature of Mixed Methods Research

Bager-Charleson, S., McBeath, A. G., & du Plock, S. (2019). The relationship between psychotherapy practice and research: A mixed-methods exploration of practitioners’ views. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19 (3), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12196 .

Article Google Scholar

Bager-Charleson, S. du Plock, S and McBeath, A.G. (2018) Therapists Have a lot to Add to the Field of Research, but Many Don’t Make it There: A Narrative Thematic Inquiry into Counsellors’ and Psychotherapists’ Embodied Engagement with Research. Psychoanalysis and Language, 7 (1), 4–22.

Google Scholar

Bhaskar, R. (1975). A realist theory of science . Hassocks, England: Harvester Press.

Bhaskar, R. (1998). The possibility of naturalism . London: Routledge.

Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research . London: Sage Publications.

Danermark, B., Ekstrom, M., Jakobsen, L., & Karlsson, J. C. (2002). Explaining society: Critical realism in the social sciences . New York: Routledge.

Denscombe, M. (1998). The good research for small –Scale social research project . Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Department of Health and Social Care (2017). A Framework for mental health research.

Ellis, D., & Tucker, I. (2015). Social psychology of emotions. London, United Kingdom: Sage.

Evered, R., & Louis, R. (1981). Alternative Perspectives in the Organizational Sciences: ‘Inquiry from the Inside’ and ‘Inquiry from the Outside. Academy of Management Review, 6 (3), 385–395.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Landrum, B., & Garza, G. (2015). Mending fences: Defining the domains and approaches of quantitative and qualitative research. Qualitative Psychology, 2 (2), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000030 .

Malterud, K. (2001). The art and science of clinical knowledge: Evidence beyond measures and numbers. The Lancet., 358 , 397–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05548-9 .

McBeath, A. G. (2019). The motivations of psychotherapists: An in-depth survey. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19 (4), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12225 .

McBeath, A. G., Bager-Charleson, S., & Abarbanel, A. (2019). Therapists and Academic Writing: ‘Once upon a time psychotherapy practitioners and researchers were the same people. European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy, 19 , 103–116.

McEvoy, P., & Richards, D. (2006). A critical realist rationale for using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. Journal of Research in Nursing, 11 , 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987106060192 .

Rukeyser, M. (1968). The speed of darkness . New York: Random House.

Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in Nursing and Health, 24 (3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.1025 .

Scotland, J. (2012). Exploring the philosophical underpinnings of research: Relating ontology and epistemology to the methodology and methods of the scientific, interpretive and critical research paradigms. English Language Teaching, 5 (9), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n9p9 .

Smith, J. A., & Osborn, S. (2008). Interpretative phenomenological analysis . In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology (pp. 53–80). London: Sage.

Ukpabi, D. C., Enyindah, C. W., & Dapper, E. M. (2014). Who is winning the paradigm war? The futility of paradigm inflexibility in Administrative Sciences Research. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 16 (7), 13–17.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Metanoia Institute, London, UK

Alistair McBeath & Sofie Bager-Charleson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alistair McBeath .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Sofie Bager-Charleson & Alistair McBeath &

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

McBeath, A., Bager-Charleson, S. (2020). Introduction: Considering Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Research. In: Bager-Charleson, S., McBeath, A. (eds) Enjoying Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55127-8_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55127-8_1

Published : 24 December 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-55126-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-55127-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research: Comparing the Methods and Strategies for Education Research

No matter the field of study, all research can be divided into two distinct methodologies: qualitative and quantitative research. Both methodologies offer education researchers important insights.

Education research assesses problems in policy, practices, and curriculum design, and it helps administrators identify solutions. Researchers can conduct small-scale studies to learn more about topics related to instruction or larger-scale ones to gain insight into school systems and investigate how to improve student outcomes.

Education research often relies on the quantitative methodology. Quantitative research in education provides numerical data that can prove or disprove a theory, and administrators can easily share the number-based results with other schools and districts. And while the research may speak to a relatively small sample size, educators and researchers can scale the results from quantifiable data to predict outcomes in larger student populations and groups.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research in Education: Definitions

Although there are many overlaps in the objectives of qualitative and quantitative research in education, researchers must understand the fundamental functions of each methodology in order to design and carry out an impactful research study. In addition, they must understand the differences that set qualitative and quantitative research apart in order to determine which methodology is better suited to specific education research topics.

Generate Hypotheses with Qualitative Research

Qualitative research focuses on thoughts, concepts, or experiences. The data collected often comes in narrative form and concentrates on unearthing insights that can lead to testable hypotheses. Educators use qualitative research in a study’s exploratory stages to uncover patterns or new angles.

Form Strong Conclusions with Quantitative Research

Quantitative research in education and other fields of inquiry is expressed in numbers and measurements. This type of research aims to find data to confirm or test a hypothesis.

Differences in Data Collection Methods

Keeping in mind the main distinction in qualitative vs. quantitative research—gathering descriptive information as opposed to numerical data—it stands to reason that there are different ways to acquire data for each research methodology. While certain approaches do overlap, the way researchers apply these collection techniques depends on their goal.

Interviews, for example, are common in both modes of research. An interview with students that features open-ended questions intended to reveal ideas and beliefs around attendance will provide qualitative data. This data may reveal a problem among students, such as a lack of access to transportation, that schools can help address.

An interview can also include questions posed to receive numerical answers. A case in point: how many days a week do students have trouble getting to school, and of those days, how often is a transportation-related issue the cause? In this example, qualitative and quantitative methodologies can lead to similar conclusions, but the research will differ in intent, design, and form.

Taking a look at behavioral observation, another common method used for both qualitative and quantitative research, qualitative data may consider a variety of factors, such as facial expressions, verbal responses, and body language.

On the other hand, a quantitative approach will create a coding scheme for certain predetermined behaviors and observe these in a quantifiable manner.

Qualitative Research Methods

- Case Studies : Researchers conduct in-depth investigations into an individual, group, event, or community, typically gathering data through observation and interviews.

- Focus Groups : A moderator (or researcher) guides conversation around a specific topic among a group of participants.

- Ethnography : Researchers interact with and observe a specific societal or ethnic group in their real-life environment.

- Interviews : Researchers ask participants questions to learn about their perspectives on a particular subject.

Quantitative Research Methods

- Questionnaires and Surveys : Participants receive a list of questions, either closed-ended or multiple choice, which are directed around a particular topic.