How to Write an Effective Persuasive Speech Outline: 5 Key Elements

- The Speaker Lab

- April 14, 2024

Table of Contents

If you’re a speaker, you are probably well familiar with the path from initial speech drafts to the day you actually present. By its nature, speech delivery is a journey filled with obstacles, yet it’s simultaneously an adventure in persuasion. With a well-crafted persuasive speech outline , you can do more than just present facts and figures to your audience. You can weave them into a narrative that captivates, convinces, and converts.

A meticulously planned persuasive speech outline isn’t just helpful; it’s essential. Crafting this blueprint carefully lets you deliver your message more effectively, making sure each point lands with the impact you’re aiming for. To help you achieve this impact, we have some tips and tricks for you to try.

Writing an Effective Persuasive Speech Outline

When we talk about persuasive speeches , we’re diving into the art of convincing others to see things from a certain point of view. Your speech is your one shot to grab attention, build your case, and inspire action. Your secret weapon for achieving this is your speech outline. In your speech outline, you want to touch on several key elements.

- Pick your fight: Start by zeroing in on what you really want to change or influence with this speech.

- Support your claim with evidence: Identify those key points that back up your stance to appeal to your audience’s rational side .

- The emotional hook: Weave in stories or facts that hit home emotionally .

- Avoid the kitchen sink approach: Don’t throw everything at them hoping something sticks. Be selective and strategic with the info you share.

- Nail that closer: Your conclusion isn’t just goodbye; it’s where you charge your audience with a call to action.

These elements form the backbone of your persuasive speech. By including these in your talk’s outline, you can’t go wrong.

Find Out Exactly How Much You Could Make As a Paid Speaker

Use The Official Speaker Fee Calculator to tell you what you should charge for your first (or next) speaking gig — virtual or in-person!

Establishing Your Main Objective and Structuring Your Points

Now that you have a general idea of what goes into a persuasive speech outline, let’s break a couple of these pieces down and look at them a little more closely.

Identifying the Purpose of Your Persuasive Speech

When writing your speech, you first need to nail down why you’re doing this in the first place. In other words, identify your main objective. After all, choosing to speak up isn’t merely about the desire to express oneself; it’s deeply rooted in understanding the effect you hope your discourse will unleash. Do you hope to sway opinions towards the belief that animal experimentation is a relic of the past? Or perhaps persuade them that social media does more good than harm? Whatever your cause, identifying your main objective will help keep you on track and avoid rambling.

Organizing Key Points for Maximum Impact

Once you’ve determined what you want to persuade your audience of, you can start building your argument. Specifically, you can determine your key points. Key points support your position on a topic, proving to your audience that you have actual reasons for taking your position.

To pack the most punch, arrange these key points in a logical order. Consider how you might connect your key points. Are there some that can be grouped together? The flow of your argument matters just as much as the argument itself, and a disjointed argument won’t do anyone any favors. As you organize your key points, consider these tips:

- Lead with strength, but don’t throw all your cards out at once.

- Build upon each point; important transitions between them can make or break audience engagement.

- Finish strong by tying back everything to the emotional chord you struck at the beginning.

Nailing these steps will ensure that when you speak, your message doesn’t just echo—it resonates.

Selecting Compelling Topics for Your Persuasive Speeches

Let’s face it, picking the right topic for your persuasive speech outline is half the battle. But what makes a topic not just good, but great? First off, it needs to spark interest, both yours and your audience’s. If you’re not fired up about it, chances are they won’t be either. Second, make sure the topic is something relevant. It should resonate with your listeners’ experiences or touch on their concerns and aspirations. Lastly, your topic has to be something you can research and back up with solid facts and expert opinions.

For ideas to get you started, check out a variety of speech topics here .

Enhancing Persuasion Through Rhetorical Appeals

The art of persuasion is something that’s been studied since ancient Greece. Back then, Greek philosopher Aristotle came up with the three rhetorical appeals . Each one described a different way of convincing your audience of your position. Together, these appeals help you form a rock-strong argument, making them worth learning.

Building Credibility with Ethos

To get people on your side, you first need to win their trust. That’s where ethos comes into play. Demonstrating to your listeners that you’re both trustworthy and deserving of their attention hinges on transparency about your qualifications, genuine self, and the wisdom gained from occasional setbacks. Letting folks know why they should listen can make all the difference.

Connecting with the Audience Through Pathos

At some point, we’ve all been moved by a story or an ad because it hit right in the feels. That sort of emotional appeal is called pathos , and it’s powerful stuff. If you want people really invested in what you’re saying, then be sure to use this appeal in your presentation. To harness the power of pathos, try telling a story , especially one your audience can relate to. The key is authenticity—sharing true experiences resonates more than anything fabricated ever could.

Strengthening Arguments with Logos

Last but not least, we have logos, our logical appeal. Oftentimes, this logical appeal entails facts and data points, which are used to back up what you’re selling, turning skeptics into believers. But just because you’re listing facts and figures doesn’t mean this part has to be boring. To keep your audience engaged, craft persuasive narratives and then ground them in robust proof. Giving your story to go with your numbers doesn’t just help keep them engaged, it also helps the information stick.

The Importance of Supporting Evidence and Counterarguments

In your persuasive speech outline, you need to note compelling evidence for each key point. In addition, you’ll want to address opposing views.

Gathering and Presenting Convincing Evidence

No matter how trustworthy you seem, or how compelling your stories are, most people need tangible proof. That’s where concrete evidence steps into the spotlight. To fortify your argument and boost its believability, sprinkle in a mix of hard data, customer stories, numerical evidence, and endorsements from authorities. To illustrate this data for your audience, you may find it helpful to create a slideshow . Supporting every assertion with research is an essential part of any persuasive speech. Without it, arguments inevitably sound flimsy and unconvincing.

Addressing Opposing Views Effectively

Although it may seem counterintuitive, address counter-arguments head-on in your persuasive speech outline. It might feel like walking into enemy territory but it actually strengthens your own argument. By acknowledging opposing views, you’re showing that not only do you know what they are, but also that they don’t scare you.

When you address these counter-arguments, demonstrate your understanding. Again, this is where your good research skills are going to come in handy. Present the facts, and ditch biased explanations. In other words, don’t mock or belittle the other side’s viewpoint or you’ll undermine your own trustworthiness. Instead, explain opposing viewpoints with neutrality.

Adopting this strategy not only neutralizes possible objections but also enhances your stance. Plus, this makes for an engaging dialogue between both sides of any debate, which keeps audience members hooked from start to finish.

In essence, tackling counter-arguments is less about winning over naysayers and more about enriching discussions around hot-button issues. At its core, persuasion isn’t just convincing folks; it’s sparking conversations worth having.

Crafting a Captivating Introduction and Conclusion

Now that you have the body of your persuasive speech outline, it’s time to talk beginning and end. To really hit your message home, you want to grab your audience’s attention at the beginning and call them to action at the end.

Creating an Engaging Hook to Capture Attention

The opening of your speech is where you need a good first impression. To hook your audience, consider starting with an intriguing question, a surprising fact, or even a short story related to your topic. Whatever route you choose, keep it interesting and concise, so that you can transition into the rest of your persuasive speech outline.

Concluding with a Strong Call to Action

Crafting strong conclusions is about leaving your readers feeling pumped and ready to jump into action. After all, if you’ve argued convincingly enough, your audience should be ready to act. To channel this energy, urge listeners towards specific actions. Here are some strategies:

- Suggest clear next steps: Don’t leave your audience hanging wondering what’s next. Give them concrete steps they can take immediately after reading.

- Create urgency: Why wait? Let folks know why now is the perfect time to act.

- Show benefits: Paint vivid pictures of how taking action will positively impact their lives or solve their problems.

With that captivating hook and a decisive call-to-action, you are one step closer to presenting an unforgettable speech.

Utilizing Monroe’s Motivated Sequence for Persuasive Structure

As you finish off your persuasive speech outline, you may be wondering how best to structure your speech. If that’s you, then Purdue University professor Alan H. Monroe has some answers. In his book “Monroe’s Principles of Speech,” the professor outlines Monroe’s Motivated Sequence, the best structure for persuasive speeches. Each step is broken down below.

Attention: Grabbing the Audience’s Focus

You’ve got something important to say. But first, you need them to listen. Start with a bang. Throwing out a shocking truth, posing a thought-provoking query, or sharing an enthralling tale could work magic in grabbing their attention. It’s all about making heads turn and ears perk up.

Need: Highlighting the Issue at Hand

Now that they’re listening, show them there’s a gaping hole in their lives that only your message can fill. Paint a vivid picture of the problem your speech addresses.

Satisfaction: Proposing a Solution

This is where you come in as the hero with a plan. Introduce your solution clearly and convincingly. How does it patch things up? Why does it outshine merely applying quick fixes to deep-rooted issues? Give your audience hope.

Visualization: Helping the Audience Visualize Benefits

Show them life on the other side of adopting your idea or product—brighter, easier, better. Use vivid imagery and relatable scenarios so they can see themselves reaping those benefits firsthand.

Action: Encouraging Audience Action

Last step: nudge them from “maybe” to “yes.” Make this part irresistible by being clear about what action they should take next—and why now’s the time to act. Whether signing up, voting, or changing behavior, make sure they know how easy taking that first step can be.

Learn more about Monroe’s Motivated Sequence here .

Free Download: 6 Proven Steps to Book More Paid Speaking Gigs in 2024

Download our 18-page guide and start booking more paid speaking gigs today!

Overcoming Public Speaking Fears for Effective Delivery

Let’s face it, the thought of public speaking can turn even the most confident folks into a bundle of nerves. But hey, you’ve got this. Dive into these expert strategies and you’ll find yourself delivering speeches like a seasoned orator in no time.

Techniques to Build Confidence in Public Speaking

If you’re feeling nervous on the big day, these three techniques are perfect for you. Take a look!

- Breathe: Deep breathing is your secret weapon against those pesky nerves. It tells your brain that everything is going to be okay.

- Pose like a superhero: Stand tall and strike a power pose before you go on stage. This isn’t just fun; science backs it up as a confidence booster .

- Kick perfectionism to the curb: Aim for connection with your audience, not perfection. Mistakes make you human and more relatable.

The goal here is to calm yourself enough to be able to deliver your persuasive speech outline with confidence. Even if you still feel a little nervous, you can still present an awesome speech. You just don’t want those nerves running the show.

Practicing Your Speech for Perfect Execution

If you know that you tend to get nervous when public speaking, then you don’t want to be running through you speech for the first time on the big day. Instead, practice beforehand using these techniques.

- The mirror is your friend: Practice in front of a mirror to catch any odd gestures or facial expressions.

- Vary your voice: As you deliver your speech, let your voice rise and fall to match what you’re sharing. Avoid speaking in a monotone.

- Say no to memorization: Rather than memorizing every word, learn key points by heart. You want to sound natural out there.

Remembering these steps won’t just help you tackle public speaking fear, but will also polish those all-important public speaking skills .

Once you’ve honed the skills you need to write a persuasive speech outline, the only thing left to do is to get out there and practice them. So take the rhetorical appeals—ethos, logos, and pathos—and practice weaving each element into your speech. Or take Monroe’s Motivated Sequence and work on structuring your outline accordingly.

Prepare well and when you hit the stage, you have not just a well-prepared persuasive speech outline, but also the power to alter perspectives, challenge the status quo, or even change lives.

- Last Updated: April 11, 2024

Explore Related Resources

Learn How You Could Get Your First (Or Next) Paid Speaking Gig In 90 Days or Less

We receive thousands of applications every day, but we only work with the top 5% of speakers .

Book a call with our team to get started — you’ll learn why the vast majority of our students get a paid speaking gig within 90 days of finishing our program .

If you’re ready to control your schedule, grow your income, and make an impact in the world – it’s time to take the first step. Book a FREE consulting call and let’s get you Booked and Paid to Speak ® .

About The Speaker Lab

We teach speakers how to consistently get booked and paid to speak. Since 2015, we’ve helped thousands of speakers find clarity, confidence, and a clear path to make an impact.

Get Started

Let's connect.

Copyright ©2023 The Speaker Lab. All rights reserved.

Counterarguments

A counterargument involves acknowledging standpoints that go against your argument and then re-affirming your argument. This is typically done by stating the opposing side’s argument, and then ultimately presenting your argument as the most logical solution. The counterargument is a standard academic move that is used in argumentative essays because it shows the reader that you are capable of understanding and respecting multiple sides of an argument.

Counterargument in two steps

Respectfully acknowledge evidence or standpoints that differ from your argument.

Refute the stance of opposing arguments, typically utilizing words like “although” or “however.”

In the refutation, you want to show the reader why your position is more correct than the opposing idea.

Where to put a counterargument

Can be placed within the introductory paragraph to create a contrast for the thesis statement.

May consist of a whole paragraph that acknowledges the opposing view and then refutes it.

- Can be one sentence acknowledgements of other opinions followed by a refutation.

Why use a counterargument?

Some students worry that using a counterargument will take away from their overall argument, but a counterargument may make an essay more persuasive because it shows that the writer has considered multiple sides of the issue. Barnet and Bedau (2005) propose that critical thinking is enhanced through imagining both sides of an argument. Ultimately, an argument is strengthened through a counterargument.

Examples of the counterargument structure

- Argument against smoking on campus: Admittedly, many students would like to smoke on campus. Some people may rightly argue that if smoking on campus is not illegal, then it should be permitted; however, second-hand smoke may cause harm to those who have health issues like asthma, possibly putting them at risk.

- Argument against animal testing: Some people argue that using animals as test subjects for health products is justifiable. To be fair, animal testing has been used in the past to aid the development of several vaccines, such as small pox and rabies. However, animal testing for beauty products causes unneeded pain to animals. There are alternatives to animal testing. Instead of using animals, it is possible to use human volunteers. Additionally, Carl Westmoreland (2006) suggests that alternative methods to animal research are being developed; for example, researchers are able to use skin constructed from cells to test cosmetics. If alternatives to animal testing exist, then the practice causes unnecessary animal suffering and should not be used.

Harvey, G. (1999). Counterargument. Retrieved from writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/counter- argument

Westmoreland, C. (2006; 2007). “Alternative Tests and the 7th Amendment to the Cosmetics Directive.” Hester, R. E., & Harrison, R. M. (Ed.) Alternatives to animal testing (1st Ed.). Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry.

Barnet, S., Bedau, H. (Eds.). (2006). Critical thinking, reading, and writing . Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Contributor: Nathan Lachner

When you write an academic essay, you make an argument: you propose a thesis and offer some reasoning, using evidence, that suggests why the thesis is true. When you counter-argue, you consider a possible argument against your thesis or some aspect of your reasoning. This is a good way to test your ideas when drafting, while you still have time to revise them. And in the finished essay, it can be a persuasive and (in both senses of the word) disarming tactic. It allows you to anticipate doubts and pre-empt objections that a skeptical reader might have; it presents you as the kind of person who weighs alternatives before arguing for one, who confronts difficulties instead of sweeping them under the rug, who is more interested in discovering the truth than winning a point.

Not every objection is worth entertaining, of course, and you shouldn't include one just to include one. But some imagining of other views, or of resistance to one's own, occurs in most good essays. And instructors are glad to encounter counterargument in student papers, even if they haven't specifically asked for it.

The Turn Against

Counterargument in an essay has two stages: you turn against your argument to challenge it and then you turn back to re-affirm it. You first imagine a skeptical reader, or cite an actual source, who might resist your argument by pointing out

- a problem with your demonstration, e.g., that a different conclusion could be drawn from the same facts, a key assumption is unwarranted, a key term is used unfairly, certain evidence is ignored or played down;

- one or more disadvantages or practical drawbacks to what you propose;

- an alternative explanation or proposal that makes more sense.

You introduce this turn against with a phrase like One might object here that... or It might seem that... or It's true that... or Admittedly,... or Of course,... or with an anticipated challenging question: But how...? or But why...? or But isn't this just...? or But if this is so, what about...? Then you state the case against yourself as briefly but as clearly and forcefully as you can, pointing to evidence where possible. (An obviously feeble or perfunctory counterargument does more harm than good.)

The Turn Back

Your return to your own argument—which you announce with a but, yet, however, nevertheless or still —must likewise involve careful reasoning, not a flippant (or nervous) dismissal. In reasoning about the proposed counterargument, you may

- refute it, showing why it is mistaken—an apparent but not real problem;

- acknowledge its validity or plausibility, but suggest why on balance it's relatively less important or less likely than what you propose, and thus doesn't overturn it;

- concede its force and complicate your idea accordingly—restate your thesis in a more exact, qualified, or nuanced way that takes account of the objection, or start a new section in which you consider your topic in light of it. This will work if the counterargument concerns only an aspect of your argument; if it undermines your whole case, you need a new thesis.

Where to Put a Counterargument

Counterargument can appear anywhere in the essay, but it most commonly appears

- as part of your introduction—before you propose your thesis—where the existence of a different view is the motive for your essay, the reason it needs writing;

- as a section or paragraph just after your introduction, in which you lay out the expected reaction or standard position before turning away to develop your own;

- as a quick move within a paragraph, where you imagine a counterargument not to your main idea but to the sub-idea that the paragraph is arguing or is about to argue;

- as a section or paragraph just before the conclusion of your essay, in which you imagine what someone might object to what you have argued.

But watch that you don't overdo it. A turn into counterargument here and there will sharpen and energize your essay, but too many such turns will have the reverse effect by obscuring your main idea or suggesting that you're ambivalent.

Counterargument in Pre-Writing and Revising

Good thinking constantly questions itself, as Socrates observed long ago. But at some point in the process of composing an essay, you need to switch off the questioning in your head and make a case. Having such an inner conversation during the drafting stage, however, can help you settle on a case worth making. As you consider possible theses and begin to work on your draft, ask yourself how an intelligent person might plausibly disagree with you or see matters differently. When you can imagine an intelligent disagreement, you have an arguable idea.

And, of course, the disagreeing reader doesn't need to be in your head: if, as you're starting work on an essay, you ask a few people around you what they think of topic X (or of your idea about X) and keep alert for uncongenial remarks in class discussion and in assigned readings, you'll encounter a useful disagreement somewhere. Awareness of this disagreement, however you use it in your essay, will force you to sharpen your own thinking as you compose. If you come to find the counterargument truer than your thesis, consider making it your thesis and turning your original thesis into a counterargument. If you manage to draft an essay without imagining a counterargument, make yourself imagine one before you revise and see if you can integrate it.

Gordon Harvey (adapted from The Academic Essay: A Brief Anatomy), for the Writing Center at Harvard University

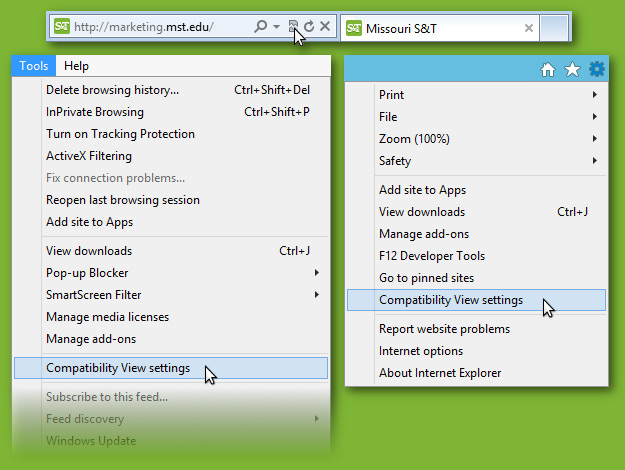

Your version of Internet Explorer is either running in "Compatibility View" or is too outdated to display this site. If you believe your version of Internet Explorer is up to date, please remove this site from Compatibility View by opening Tools > Compatibility View settings (IE11) or clicking the broken page icon in your address bar (IE9, IE10)

Missouri S&T Missouri S&T

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- writingcenter.mst.edu

- Online Resources

- Writing Guides

- Counter Arguments

Writing and Communication Center

- 314 Curtis Laws Wilson Library, 400 W 14th St Rolla, MO 65409 United States

- (573) 341-4436

- [email protected]

Counter Argument

One way to strengthen your argument and demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the issue you are discussing is to anticipate and address counter arguments, or objections. By considering opposing views, you show that you have thought things through, and you dispose of some of the reasons your audience might have for not accepting your argument. Ask yourself what someone who disagrees with you might say in response to each of the points you’ve made or about your position as a whole.

If you can’t immediately imagine another position, here are some strategies to try:

- Do some research. It may seem to you that no one could possibly disagree with the position you are taking, but someone probably has. Look around to see what stances people have and do take on the subject or argument you plan to make, so that you know what environment you are addressing.

- Talk with a friend or with your instructor. Another person may be able to play devil’s advocate and suggest counter arguments that haven’t occurred to you.

- Consider each of your supporting points individually. Even if you find it difficult to see why anyone would disagree with your central argument, you may be able to imagine more easily how someone could disagree with the individual parts of your argument. Then you can see which of these counter arguments are most worth considering. For example, if you argued “Cats make the best pets. This is because they are clean and independent,” you might imagine someone saying “Cats do not make the best pets. They are dirty and demanding.”

Once you have considered potential counter arguments, decide how you might respond to them: Will you concede that your opponent has a point but explain why your audience should nonetheless accept your argument? Or will you reject the counterargument and explain why it is mistaken? Either way, you will want to leave your reader with a sense that your argument is stronger than opposing arguments.

Two strategies are available to incorporate counter arguments into your essay:

Refutation:

Refutation seeks to disprove opposing arguments by pointing out their weaknesses. This approach is generally most effective if it is not hostile or sarcastic; with methodical, matter-of-fact language, identify the logical, theoretical, or factual flaws of the opposition.

For example, in an essay supporting the reintroduction of wolves into western farmlands, a writer might refute opponents by challenging the logic of their assumptions:

Although some farmers have expressed concern that wolves might pose a threat to the safety of sheep, cattle, or even small children, their fears are unfounded. Wolves fear humans even more than humans fear wolves and will trespass onto developed farmland only if desperate for food. The uninhabited wilderness that will become the wolves’ new home has such an abundance of food that there is virtually no chance that these shy animals will stray anywhere near humans.

Here, the writer acknowledges the opposing view (wolves will endanger livestock and children) and refutes it (the wolves will never be hungry enough to do so).

Accommodation:

Accommodation acknowledges the validity of the opposing view, but argues that other considerations outweigh it. In other words, this strategy turns the tables by agreeing (to some extent) with the opposition.

For example, the writer arguing for the reintroduction of wolves might accommodate the opposing view by writing:

Critics of the program have argued that reintroducing wolves is far too expensive a project to be considered seriously at this time. Although the reintroduction program is costly, it will only become more costly the longer it is put on hold. Furthermore, wolves will help control the population of pest animals in the area, saving farmers money on extermination costs. Finally, the preservation of an endangered species is worth far more to the environment and the ecological movement than the money that taxpayers would save if this wolf relocation initiative were to be abandoned.

This writer acknowledges the opposing position (the program is too expensive), agrees (yes, it is expensive), and then argues that despite the expense the program is worthwhile.

Some Final Hints

Don’t play dirty. When you summarize opposing arguments, be charitable. Present each argument fairly and objectively, rather than trying to make it look foolish. You want to convince your readers that you have carefully considered all sides of the issues and that you are not simply attacking or caricaturing your opponents.

Sometimes less is more. It is usually better to consider one or two serious counter arguments in some depth, rather than to address every counterargument.

Keep an open mind. Be sure that your reply is consistent with your original argument. Careful consideration of counter arguments can complicate or change your perspective on an issue. There’s nothing wrong with adopting a different perspective or changing your mind, but if you do, be sure to revise your thesis accordingly.

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students

- ★ The Writing Workshop

- Dissertation ECoach

- Fellows Seminar

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Rackham / Sweetland Workshops

- Dissertation Writing Institute

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- Teaching Support and Services

- Support for FYWR Courses

- Support for ULWR Courses

- Writing Prize Nominating

- Alums Gallery

- Commencement

- Giving Opportunities

- How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument?

- How Do I Make Sure I Understand an Assignment?

- How Do I Decide What I Should Argue?

- How Can I Create Stronger Analysis?

- How Do I Effectively Integrate Textual Evidence?

- How Do I Write a Great Title?

- What Exactly is an Abstract?

- How Do I Present Findings From My Experiment in a Report?

- What is a Run-on Sentence & How Do I Fix It?

- How Do I Check the Structure of My Argument?

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph?

- How Do I Incorporate Quotes?

- How Can I Create a More Successful Powerpoint?

- How Can I Create a Strong Thesis?

- How Can I Write More Descriptively?

- How Do I Check My Citations?

See the bottom of the main Writing Guides page for licensing information.

One way to build credibility in crafting persuasive arguments is to make use of possible well-reasoned objections to your argument. Sometimes when we spend so much time coming up with a persuasive argument, we tend to want to avoid even acknowledging its possible flaws, for fear of weakening our stance. We may just avoid bringing them up altogether in order to ensure the apparent solidity of our argument. Even when we decide to reckon with possible objections, we tend to rely on one primary method of including them—the paragraph right before the conclusion in a five-paragraph essay. This can feel boring if you’ve been doing it for a long time. The good news is, there are actually more options available to you, and you should make a decision about which to use based on your argument’s audience and purpose.

General Considerations

A counterargument is a type of rebuttal..

Rebuttals are your way of acknowledging and dealing with objections to your argument, and they can take two different forms:

- Refutations: Refutations are an often more confrontational form of rebuttal that work by targeting the weaknesses in a possible objection to your argument. Think of refutations as the more sophisticated and mature older sibling of, “that’s not true!” Generally, they work by pointing out weaknesses with the solidity or rationale of the objection’s claim itself (what the objector says about the argument) or of its evidence (the support offered for the claim).

- Counterarguments: Counterarguments are a more cooperative form of rebuttal . In counterarguments, a writer acknowledges the strengths or validity of someone else’s argument, but then makes a case for why their approach is still the best/most effective/most viable

Incorporating counterarguments helps you build your credibility as a writer.

Once you learn how to seek out possible objections or counters to your own arguments and incorporate them fairly, you increase your power to build credibility with your readers. Refutations can feel satisfying (“No, you’re just wrong!”), and there are certainly situations in which they are the best or only ethical approach. However, most of the time counterarguments bring your readers to your side more effectively. This is because they are empathetic and invitational by nature (“I can see where in situation XYZ, what you suggest would make the most sense; however, in this situation, my approach works best because ABC…”)

In Practice

Rebuttals: not just for the penultimate paragraph anymore.

Structurally, incorporating rebuttals can be done in a few ways:

- The tried and true paragraph or section before the conclusion that explicitly addresses possible objections by acknowledging and then dispatching with them;

- A possible objection and response with for each claim in the essay; or

- An entire argument can even be structured as a rebuttal to someone else’s argument.

Seek out opposing views

1. What reasonable claims have others made that contradict your argument? If you don’t know any, FIND SOME. (We promise: they exist.) Write them down in complete sentences.

a. Try writing a refutation to the claims. Is there any way in which the claims themselves are weak? Articulate them. Are there underlying assumptions behind the claims that might be faulty? Articulate them.

b. Try writing a counterargument to the claims. In what conditions might the claims others make be justified? How so? How is this instance different from those conditions? Why does your claim make more sense here and now? Is there anything you can incorporate from those claims to strengthen your own?

2. If you were to launch your own rebuttal to your argument, what would that look like? How would you then overcome that rebuttal?

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

17.3 Organizing Persuasive Speeches

Learning objectives.

- Understand three common organizational patterns for persuasive speeches.

- Explain the steps utilized in Monroe’s motivated sequence.

- Explain the parts of a problem-cause-solution speech.

- Explain the process utilized in a comparative advantage persuasive speech.

Steven Lilley – Engaged – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Previously in this text we discussed general guidelines for organizing speeches. In this section, we are going to look at three organizational patterns ideally suited for persuasive speeches: Monroe’s motivated sequence, problem-cause-solution, and comparative advantages.

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

One of the most commonly cited and discussed organizational patterns for persuasive speeches is Alan H. Monroe’s motivated sequence. The purpose of Monroe’s motivated sequence is to help speakers “sequence supporting materials and motivational appeals to form a useful organizational pattern for speeches as a whole” (German et al., 2010).

While Monroe’s motivated sequence is commonly discussed in most public speaking textbooks, we do want to provide one minor caution. Thus far, almost no research has been conducted that has demonstrated that Monroe’s motivated sequence is any more persuasive than other structural patterns. In the only study conducted experimentally examining Monroe’s motivated sequence, the researchers did not find the method more persuasive, but did note that audience members found the pattern more organized than other methods (Micciche, Pryor, & Butler, 2000). We wanted to add this sidenote because we don’t want you to think that Monroe’s motivated sequence is a kind of magic persuasive bullet; the research simply doesn’t support this notion. At the same time, research does support that organized messages are perceived as more persuasive as a whole, so using Monroe’s motivated sequence to think through one’s persuasive argument could still be very beneficial.

Table 17.1 “Monroe’s Motivated Sequence” lists the basic steps of Monroe’s motivated sequence and the subsequent reaction a speaker desires from his or her audience.

Table 17.1 Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

The first step in Monroe’s motivated sequence is the attention step , in which a speaker attempts to get the audience’s attention. To gain an audience’s attention, we recommend that you think through three specific parts of the attention step. First, you need to have a strong attention-getting device. As previously discussed in Chapter 9 “Introductions Matter: How to Begin a Speech Effectively” , a strong attention getter at the beginning of your speech is very important. Second, you need to make sure you introduce your topic clearly. If your audience doesn’t know what your topic is quickly, they are more likely to stop listening. Lastly, you need to explain to your audience why they should care about your topic.

In the need step of Monroe’s motivated sequence, the speaker establishes that there is a specific need or problem. In Monroe’s conceptualization of need, he talks about four specific parts of the need: statement, illustration, ramification, and pointing. First, a speaker needs to give a clear and concise statement of the problem. This part of a speech should be crystal clear for an audience. Second, the speaker needs to provide one or more examples to illustrate the need. The illustration is an attempt to make the problem concrete for the audience. Next, a speaker needs to provide some kind of evidence (e.g., statistics, examples, testimony) that shows the ramifications or consequences of the problem. Lastly, a speaker needs to point to the audience and show exactly how the problem relates to them personally.

Satisfaction

In the third step of Monroe’s motivated sequence, the satisfaction step , the speaker sets out to satisfy the need or solve the problem. Within this step, Monroe (1935) proposed a five-step plan for satisfying a need:

- Explanation

- Theoretical demonstration

- Reference to practical experience

- Meeting objections

First, you need to clearly state the attitude, value, belief, or action you want your audience to accept. The purpose of this statement is to clearly tell your audience what your ultimate goal is.

Second, you want to make sure that you clearly explain to your audience why they should accept the attitude, value, belief, or action you proposed. Just telling your audience they should do something isn’t strong enough to actually get them to change. Instead, you really need to provide a solid argument for why they should accept your proposed solution.

Third, you need to show how the solution you have proposed meets the need or problem. Monroe calls this link between your solution and the need a theoretical demonstration because you cannot prove that your solution will work. Instead, you theorize based on research and good judgment that your solution will meet the need or solve the problem.

Fourth, to help with this theoretical demonstration, you need to reference practical experience, which should include examples demonstrating that your proposal has worked elsewhere. Research, statistics, and expert testimony are all great ways of referencing practical experience.

Lastly, Monroe recommends that a speaker respond to possible objections. As a persuasive speaker, one of your jobs is to think through your speech and see what counterarguments could be made against your speech and then rebut those arguments within your speech. When you offer rebuttals for arguments against your speech, it shows your audience that you’ve done your homework and educated yourself about multiple sides of the issue.

Visualization

The next step of Monroe’s motivated sequence is the visualization step , in which you ask the audience to visualize a future where the need has been met or the problem solved. In essence, the visualization stage is where a speaker can show the audience why accepting a specific attitude, value, belief, or behavior can positively affect the future. When helping people to picture the future, the more concrete your visualization is, the easier it will be for your audience to see the possible future and be persuaded by it. You also need to make sure that you clearly show how accepting your solution will directly benefit your audience.

According to Monroe, visualization can be conducted in one of three ways: positive, negative, or contrast (Monroe, 1935). The positive method of visualization is where a speaker shows how adopting a proposal leads to a better future (e.g., recycle, and we’ll have a cleaner and safer planet). Conversely, the negative method of visualization is where a speaker shows how not adopting the proposal will lead to a worse future (e.g., don’t recycle, and our world will become polluted and uninhabitable). Monroe also acknowledged that visualization can include a combination of both positive and negative visualization. In essence, you show your audience both possible outcomes and have them decide which one they would rather have.

The final step in Monroe’s motivated sequence is the action step , in which a speaker asks an audience to approve the speaker’s proposal. For understanding purposes, we break action into two distinct parts: audience action and approval. Audience action refers to direct physical behaviors a speaker wants from an audience (e.g., flossing their teeth twice a day, signing a petition, wearing seat belts). Approval, on the other hand, involves an audience’s consent or agreement with a speaker’s proposed attitude, value, or belief.

When preparing an action step, it is important to make sure that the action, whether audience action or approval, is realistic for your audience. Asking your peers in a college classroom to donate one thousand dollars to charity isn’t realistic. Asking your peers to donate one dollar is considerably more realistic. In a persuasive speech based on Monroe’s motivated sequence, the action step will end with the speech’s concluding device. As discussed elsewhere in this text, you need to make sure that you conclude in a vivid way so that the speech ends on a high point and the audience has a sense of energy as well as a sense of closure.

Now that we’ve walked through Monroe’s motivated sequence, let’s look at how you could use Monroe’s motivated sequence to outline a persuasive speech:

Specific Purpose: To persuade my classroom peers that the United States should have stronger laws governing the use of for-profit medical experiments.

Main Points:

- Attention: Want to make nine thousand dollars for just three weeks of work lying around and not doing much? Then be a human guinea pig. Admittedly, you’ll have to have a tube down your throat most of those three weeks, but you’ll earn three thousand dollars a week.

- Need: Every day many uneducated and lower socioeconomic-status citizens are preyed on by medical and pharmaceutical companies for use in for-profit medical and drug experiments. Do you want one of your family members to fall prey to this evil scheme?

- Satisfaction: The United States should have stronger laws governing the use of for-profit medical experiments to ensure that uneducated and lower-socioeconomic-status citizens are protected.

- Visualization: If we enact tougher experiment oversight, we can ensure that medical and pharmaceutical research is conducted in a way that adheres to basic values of American decency. If we do not enact tougher experiment oversight, we could find ourselves in a world where the lines between research subject, guinea pig, and patient become increasingly blurred.

- Action: In order to prevent the atrocities associated with for-profit medical and pharmaceutical experiments, please sign this petition asking the US Department of Health and Human Services to pass stricter regulations on this preying industry that is out of control.

This example shows how you can take a basic speech topic and use Monroe’s motivated sequence to clearly and easily outline your speech efficiently and effectively.

Table 17.2 “Monroe’s Motivated Sequence Checklist” also contains a simple checklist to help you make sure you hit all the important components of Monroe’s motivated sequence.

Table 17.2 Monroe’s Motivated Sequence Checklist

Problem-Cause-Solution

Another format for organizing a persuasive speech is the problem-cause-solution format. In this specific format, you discuss what a problem is, what you believe is causing the problem, and then what the solution should be to correct the problem.

Specific Purpose: To persuade my classroom peers that our campus should adopt a zero-tolerance policy for hate speech.

- Demonstrate that there is distrust among different groups on campus that has led to unnecessary confrontations and violence.

- Show that the confrontations and violence are a result of hate speech that occurred prior to the events.

- Explain how instituting a campus-wide zero-tolerance policy against hate speech could stop the unnecessary confrontations and violence.

In this speech, you want to persuade people to support a new campus-wide policy calling for zero-tolerance of hate speech. Once you have shown the problem, you then explain to your audience that the cause of the unnecessary confrontations and violence is prior incidents of hate speech. Lastly, you argue that a campus-wide zero-tolerance policy could help prevent future unnecessary confrontations and violence. Again, this method of organizing a speech is as simple as its name: problem-cause-solution.

Comparative Advantages

The final method for organizing a persuasive speech is called the comparative advantages speech format. The goal of this speech is to compare items side-by-side and show why one of them is more advantageous than the other. For example, let’s say that you’re giving a speech on which e-book reader is better: Amazon.com’s Kindle or Barnes and Nobles’ Nook. Here’s how you could organize this speech:

Specific Purpose: To persuade my audience that the Nook is more advantageous than the Kindle.

- The Nook allows owners to trade and loan books to other owners or people who have downloaded the Nook software, while the Kindle does not.

- The Nook has a color-touch screen, while the Kindle’s screen is black and grey and noninteractive.

- The Nook’s memory can be expanded through microSD, while the Kindle’s memory cannot be upgraded.

As you can see from this speech’s organization, the simple goal of this speech is to show why one thing has more positives than something else. Obviously, when you are demonstrating comparative advantages, the items you are comparing need to be functional equivalents—or, as the saying goes, you cannot compare apples to oranges.

Key Takeaways

- There are three common patterns that persuaders can utilize to help organize their speeches effectively: Monroe’s motivated sequence, problem-cause-solution, and comparative advantage. Each of these patterns can effectively help a speaker think through his or her thoughts and organize them in a manner that will be more likely to persuade an audience.

- Alan H. Monroe’s (1935) motivated sequence is a commonly used speech format that is used by many people to effectively organize persuasive messages. The pattern consists of five basic stages: attention, need, satisfaction, visualization, and action. In the first stage, a speaker gets an audience’s attention. In the second stage, the speaker shows an audience that a need exists. In the third stage, the speaker shows how his or her persuasive proposal could satisfy the need. The fourth stage shows how the future could be if the persuasive proposal is or is not adopted. Lastly, the speaker urges the audience to take some kind of action to help enact the speaker’s persuasive proposal.

- The problem-cause-solution proposal is a three-pronged speech pattern. The speaker starts by explaining the problem the speaker sees. The speaker then explains what he or she sees as the underlying causes of the problem. Lastly, the speaker proposes a solution to the problem that corrects the underlying causes.

- The comparative advantages speech format is utilized when a speaker is comparing two or more things or ideas and shows why one of the things or ideas has more advantages than the other(s).

- Create a speech using Monroe’s motivated sequence to persuade people to recycle.

- Create a speech using the problem-cause-solution method for a problem you see on your college or university campus.

- Create a comparative advantages speech comparing two brands of toothpaste.

German, K. M., Gronbeck, B. E., Ehninger, D., & Monroe, A. H. (2010). Principles of public speaking (17th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, p. 236.

Micciche, T., Pryor, B., & Butler, J. (2000). A test of Monroe’s motivated sequence for its effects on ratings of message organization and attitude change. Psychological Reports, 86 , 1135–1138.

Monroe, A. H. (1935). Principles and types of speech . Chicago, IL: Scott Foresman.

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Improve your practice.

Enhance your soft skills with a range of award-winning courses.

Persuasive Speech Outline, with Examples

March 17, 2021 - Gini Beqiri

A persuasive speech is a speech that is given with the intention of convincing the audience to believe or do something. This could be virtually anything – voting, organ donation, recycling, and so on.

A successful persuasive speech effectively convinces the audience to your point of view, providing you come across as trustworthy and knowledgeable about the topic you’re discussing.

So, how do you start convincing a group of strangers to share your opinion? And how do you connect with them enough to earn their trust?

Topics for your persuasive speech

We’ve made a list of persuasive speech topics you could use next time you’re asked to give one. The topics are thought-provoking and things which many people have an opinion on.

When using any of our persuasive speech ideas, make sure you have a solid knowledge about the topic you’re speaking about – and make sure you discuss counter arguments too.

Here are a few ideas to get you started:

- All school children should wear a uniform

- Facebook is making people more socially anxious

- It should be illegal to drive over the age of 80

- Lying isn’t always wrong

- The case for organ donation

Read our full list of 75 persuasive speech topics and ideas .

Preparation: Consider your audience

As with any speech, preparation is crucial. Before you put pen to paper, think about what you want to achieve with your speech. This will help organise your thoughts as you realistically can only cover 2-4 main points before your audience get bored .

It’s also useful to think about who your audience are at this point. If they are unlikely to know much about your topic then you’ll need to factor in context of your topic when planning the structure and length of your speech. You should also consider their:

- Cultural or religious backgrounds

- Shared concerns, attitudes and problems

- Shared interests, beliefs and hopes

- Baseline attitude – are they hostile, neutral, or open to change?

The factors above will all determine the approach you take to writing your speech. For example, if your topic is about childhood obesity, you could begin with a story about your own children or a shared concern every parent has. This would suit an audience who are more likely to be parents than young professionals who have only just left college.

Remember the 3 main approaches to persuade others

There are three main approaches used to persuade others:

The ethos approach appeals to the audience’s ethics and morals, such as what is the ‘right thing’ to do for humanity, saving the environment, etc.

Pathos persuasion is when you appeal to the audience’s emotions, such as when you tell a story that makes them the main character in a difficult situation.

The logos approach to giving a persuasive speech is when you appeal to the audience’s logic – ie. your speech is essentially more driven by facts and logic. The benefit of this technique is that your point of view becomes virtually indisputable because you make the audience feel that only your view is the logical one.

- Ethos, Pathos, Logos: 3 Pillars of Public Speaking and Persuasion

Ideas for your persuasive speech outline

1. structure of your persuasive speech.

The opening and closing of speech are the most important. Consider these carefully when thinking about your persuasive speech outline. A strong opening ensures you have the audience’s attention from the start and gives them a positive first impression of you.

You’ll want to start with a strong opening such as an attention grabbing statement, statistic of fact. These are usually dramatic or shocking, such as:

Sadly, in the next 18 minutes when I do our chat, four Americans that are alive will be dead from the food that they eat – Jamie Oliver

Another good way of starting a persuasive speech is to include your audience in the picture you’re trying to paint. By making them part of the story, you’re embedding an emotional connection between them and your speech.

You could do this in a more toned-down way by talking about something you know that your audience has in common with you. It’s also helpful at this point to include your credentials in a persuasive speech to gain your audience’s trust.

Obama would spend hours with his team working on the opening and closing statements of his speech.

2. Stating your argument

You should pick between 2 and 4 themes to discuss during your speech so that you have enough time to explain your viewpoint and convince your audience to the same way of thinking.

It’s important that each of your points transitions seamlessly into the next one so that your speech has a logical flow. Work on your connecting sentences between each of your themes so that your speech is easy to listen to.

Your argument should be backed up by objective research and not purely your subjective opinion. Use examples, analogies, and stories so that the audience can relate more easily to your topic, and therefore are more likely to be persuaded to your point of view.

3. Addressing counter-arguments

Any balanced theory or thought addresses and disputes counter-arguments made against it. By addressing these, you’ll strengthen your persuasive speech by refuting your audience’s objections and you’ll show that you are knowledgeable to other thoughts on the topic.

When describing an opposing point of view, don’t explain it in a bias way – explain it in the same way someone who holds that view would describe it. That way, you won’t irritate members of your audience who disagree with you and you’ll show that you’ve reached your point of view through reasoned judgement. Simply identify any counter-argument and pose explanations against them.

- Complete Guide to Debating

4. Closing your speech

Your closing line of your speech is your last chance to convince your audience about what you’re saying. It’s also most likely to be the sentence they remember most about your entire speech so make sure it’s a good one!

The most effective persuasive speeches end with a call to action . For example, if you’ve been speaking about organ donation, your call to action might be asking the audience to register as donors.

Practice answering AI questions on your speech and get feedback on your performance .

If audience members ask you questions, make sure you listen carefully and respectfully to the full question. Don’t interject in the middle of a question or become defensive.

You should show that you have carefully considered their viewpoint and refute it in an objective way (if you have opposing opinions). Ensure you remain patient, friendly and polite at all times.

Example 1: Persuasive speech outline

This example is from the Kentucky Community and Technical College.

Specific purpose

To persuade my audience to start walking in order to improve their health.

Central idea

Regular walking can improve both your mental and physical health.

Introduction

Let’s be honest, we lead an easy life: automatic dishwashers, riding lawnmowers, T.V. remote controls, automatic garage door openers, power screwdrivers, bread machines, electric pencil sharpeners, etc., etc. etc. We live in a time-saving, energy-saving, convenient society. It’s a wonderful life. Or is it?

Continue reading

Example 2: Persuasive speech

Tips for delivering your persuasive speech

- Practice, practice, and practice some more . Record yourself speaking and listen for any nervous habits you have such as a nervous laugh, excessive use of filler words, or speaking too quickly.

- Show confident body language . Stand with your legs hip width apart with your shoulders centrally aligned. Ground your feet to the floor and place your hands beside your body so that hand gestures come freely. Your audience won’t be convinced about your argument if you don’t sound confident in it. Find out more about confident body language here .

- Don’t memorise your speech word-for-word or read off a script. If you memorise your persuasive speech, you’ll sound less authentic and panic if you lose your place. Similarly, if you read off a script you won’t sound genuine and you won’t be able to connect with the audience by making eye contact . In turn, you’ll come across as less trustworthy and knowledgeable. You could simply remember your key points instead, or learn your opening and closing sentences.

- Remember to use facial expressions when storytelling – they make you more relatable. By sharing a personal story you’ll more likely be speaking your truth which will help you build a connection with the audience too. Facial expressions help bring your story to life and transport the audience into your situation.

- Keep your speech as concise as possible . When practicing the delivery, see if you can edit it to have the same meaning but in a more succinct way. This will keep the audience engaged.

The best persuasive speech ideas are those that spark a level of controversy. However, a public speech is not the time to express an opinion that is considered outside the norm. If in doubt, play it safe and stick to topics that divide opinions about 50-50.

Bear in mind who your audience are and plan your persuasive speech outline accordingly, with researched evidence to support your argument. It’s important to consider counter-arguments to show that you are knowledgeable about the topic as a whole and not bias towards your own line of thought.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Responding to Counterarguments

Basics of counterarguments.

When constructing an argument, it is important to consider any counterarguments a reader might make. Acknowledging the opposition shows that you are knowledgeable about the issue and are not simply ignoring other viewpoints. Addressing counterarguments also gives you an opportunity to clarify and strengthen your argument, helping to show how your argument is stronger than other arguments.

Incorporating counterarguments into your writing can seem counterintuitive at first, and some writers may be unsure how to do so. To help you incorporate counterarguments into your argument, we recommend following the steps: (a) identify, (b) investigate, (c) address, and (d) refine.

Identify the Counterarguments

First you need to identify counterarguments to your own argument. Ask yourself, based on your argument, what might someone who disagrees counter in response? You might also discover counterarguments while doing your research, as you find authors who may disagree with your argument.

For example, if you are researching the current opioid crisis in the United States, your argument might be: State governments should allocate part of the budget for addiction recovery centers in communities heavily impacted by the opioid crisis . A few counterarguments might be:

- Recovery centers are not proven to significantly help people with addiction.

- The state’s money should go to more pressing concerns such as...

- Establishing and maintaining a recovery center is too costly.

- Addicts are unworthy of assistance from the state.

Investigate the Counterarguments

Analyze the counterarguments so that you can determine whether they are valid. This may require assessing the counterarguments with the research you already have or by identifying logical fallacies . You may also need to do additional research.

In the above list, the first three counterarguments can be researched. The fourth is a moral argument and therefore can only be addressed in a discussion of moral values, which is usually outside the realm of social science research. To investigate the first, you could do a search for research that studies the effectiveness of recovery centers. For the second, you could look at the top social issues in states around the country. Is the opioid crisis the main concern or are there others? For the third, you could look for public financial data from a recovery center or interview someone who works at one to get a sense of the costs involved.

Address the Counterarguments

Address one or two counterarguments in a rebuttal. Now that you have researched the counterarguments, consider your response. In your essay, you will need to state and refute these opposing views to give more credence to your argument. No matter how you decide to incorporate the counterargument into your essay, be sure you do so with objectivity, maintaining a formal and scholarly tone .

Considerations when writing:

- Will you discredit the counteragument by bringing in contradictory research?

- Will you concede that the point is valid but that your argument still stands as the better view? (For example, perhaps it is very costly to run a recovery center, but the societal benefits offset that financial cost.)

- Placement . You can choose to place the counterargument toward the beginning of the essay, as a way to anticipate opposition, or you can place it toward the end of the essay, after you have solidly made the main points of your argument. You can also weave a counterargument into a body paragraph, as a way to quickly acknowledge opposition to a main point. Which placement is best depends on your argument, how you’ve organized your argument, and what placement you think is most effective.

- Weight . After you have addressed the counterarguments, scan your essay as a whole. Are you spending too much time on them in comparison to your main points? Keep in mind that if you linger too long on the counterarguments, your reader might learn less about your argument and more about opposing viewpoints instead.

Refine Your Argument

Considering counterarguments should help you refine your own argument, clarifying the relevant issues and your perspective. Furthermore, if you find yourself agreeing with the counterargument, you will need to revise your thesis statement and main points to reflect your new thinking.

Templates for Responding to Counterarguments

There are many ways you can incorporate counterarguments, but remember that you shouldn’t just mention the counterargument—you need to respond to it as well. You can use these templates (adapted from Graff & Birkenstein, 2009) as a starting point for responding to counterarguments in your own writing.

- The claim that _____ rests upon the questionable assumption that _____.

- X may have been true in the past, but recent research has shown that ________.

- By focusing on _____, X has overlooked the more significant problem of _____.

- Although I agree with X up to a point, I cannot accept the overall conclusion that _____.

- Though I concede that _____, I still insist that _____.

- Whereas X has provided ample evidence that ____, Y and Z’s research on ____ and ____ convinces me that _____ instead.

- Although I grant that _____, I still maintain that _____.

- While it is true that ____, it does not necessarily follow that _____.

Graff, G., & Birkenstein, C. (2009). They say/I say: The moves that matter in academic writing (2 nd ed.). Norton.

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Addressing Assumptions

- Next Page: Revising

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 Persuasive Speaking

Adapted from:

Tucker, Barbara and Barton, Kristin, “Exploring Public Speaking” (2016). Communication Open Textbooks. Book 1. http://oer.galileo.usg.edu/communication-textbooks/1

Learning Objectives

- Define and explain persuasion.

- Understand three main types of persuasive appeals.

Every day we are bombarded with persuasive messages. Some messages are mediated and designed to get us to purchase specific products or vote for a particular candidate, while others might come from our loved ones and are designed to get us to help around the house or join the family for game night. Whatever the message being sent, we are constantly being persuaded and persuading others. In this chapter, we are going to focus on persuasive speaking. We will first talk about persuasion as a general concept. We will then examine four different types of persuasive speeches, and finally, we’ll look at three organizational patterns that are useful for persuasive speeches.

Why Persuasion?

NBS NewsHour – Podium – CC BY-NC 2.0.

We defined persuasion earlier in this text as an attempt to get a person to behave in a manner, or embrace a point of view related to values, attitudes, and beliefs, that he or she would not have done otherwise. Perloff (2003) defines persuasion as :

A symbolic process in which communicators try to convince other people to change their attitudes or behavior regarding an issue through the transmission of a message, in an atmosphere of free choice. (p. 8)

First, notice that persuasion is symbolic, that is, uses language or other symbols (even graphics can be symbols), rather than force or other means. Second, notice that it is an attempt, not always entirely successful. Third, there is an “atmosphere of free choice,” in that the persons being persuaded can choose not to believe or act. And fourth, notice that the persuader is “trying to convince others to change.”

Some of this may sound like splitting hairs, but these are four important points. The fact that audience members have a free choice means that they are active participants in their own persuasion. They can choose whether the speaker is successful. For our purposes in this class, it calls on the student speaker to be ethical and truthful. Sometimes students will say, “It is just a class assignment, I can lie in this speech,” but that is not a fair way to treat your classmates.

Perloff’s definition distinguishes between “attitude” and “behavior,” meaning that an audience may be persuaded to think, to feel, or to act. Finally, persuasion is a process. Successful persuasion actually takes a while. One speech can be effective, but usually, other messages influence the listener in the long run.

Two Definitions of Persuasion

Persuasion is an attempt to get a person to behave in a manner, or embrace a point of view related to values, attitudes, and beliefs, that he or she would not have done otherwise.

Perloff’s definition of persuasion is, persuasion is a symbolic process in which communicators try to convince other people to change their attitudes or behavior regarding an issue through the transmission of a message, in an atmosphere of free choice.

Change Attitudes, Values, and Beliefs

The first type of persuasive public speaking involves a change in someone’s attitudes, values, and beliefs. An attitude is defined as an individual’s general predisposition toward something as being good or bad, right or wrong, or negative or positive. Maybe you believe that local curfew laws for people under twenty-one are a bad idea, so you want to persuade others to adopt a negative attitude toward such laws.

You can also attempt to persuade an individual to change her or his value of something. A value refers to an individual’s perception of the usefulness, importance, or worth of something. We can value a college education or technology or freedom. Values, as a general concept, are fairly ambiguous and tend to be very lofty ideas. Ultimately, what we value in life motivates us to engage in a range of behaviors. For example, if you value technology, you are more likely to seek out new technology or software on your own. On the contrary, if you do not value technology, you are less likely to seek out new technology or software unless someone, or some circumstance, requires you to.

Lastly, you can attempt to get people to change their personal beliefs. Beliefs are propositions or positions that an individual holds as true or false without positive knowledge or proof. Typically, beliefs are divided into two basic categories: core and dispositional. Core beliefs are beliefs that people have actively engaged in and created over the course of their lives (e.g. belief in a higher power or belief in extraterrestrial life forms). Dispositional beliefs , on the other hand, are beliefs that people have not actively engaged in but rather judgments that they make, based on their knowledge of related subjects, and when they encounter a proposition. For example, imagine that you were asked the question, “Can stock cars reach speeds of one thousand miles per hour on a one-mile oval track?” Even though you may never have attended a stock car race or even seen one on television, you can make split-second judgments about your understanding of automobile speeds and say with a fair degree of certainty that you believe stock cars cannot travel at one thousand miles per hour on a one-mile track. We sometimes refer to dispositional beliefs as virtual beliefs (Frankish, 1998).

When it comes to persuading people to alter core and dispositional beliefs, persuading audiences to change core beliefs is more difficult than persuading audiences to alter dispositional beliefs. For this reason, you are very unlikely to persuade people to change their deeply held core beliefs about a topic in a five- to ten-minute speech. However, if you give a persuasive speech on a topic related to an audience’s dispositional beliefs, you may have a better chance of success. While core beliefs may seem to be exciting and interesting, persuasive topics related to dispositional beliefs are generally better for novice speakers with limited time allotments.

An attitude is defined as an individual’s general predisposition toward something as being good or bad, right or wrong, or negative or positive.

A value refers to an individual’s perception of the usefulness, importance, or worth of something.

Beliefs are propositions or positions that an individual holds as true or false without positive knowledge or proof.

Core beliefs are beliefs that people have actively engaged in and created over the course of their lives (e.g. belief in a higher power or belief in extraterrestrial life forms).

Dispositional beliefs are beliefs that people have not actively engaged in but rather judgments that they make, based on their knowledge of related subjects, and when they encounter a proposition.

Change Behavior

The second type of persuasive speech is one in which the speaker attempts to persuade an audience to change their behavior. Behaviors come in a wide range of forms, so finding one you think people should start, increase, or decrease shouldn’t be difficult at all. Speeches encouraging audiences to vote for a candidate, sign a petition opposing a tuition increase, or drink tap water instead of bottled water are all behavior-oriented persuasive speeches. In all these cases, the goal is to change the behavior of individual listeners.

Why Persuasion Matters

Frymier and Nadler enumerate three reasons why people should study persuasion (Frymier & Nadler, 2007). First, when you study and understand persuasion, you will be more successful at persuading others. If you want to be a persuasive public speaker, then you need to have a working understanding of how persuasion functions.

Second, when people understand persuasion, they will be better consumers of information. As previously mentioned, we live in a society where numerous message sources are constantly fighting for our attention. Unfortunately, most people just let messages wash over them like a wave, making little effort to understand or analyze them. As a result, they are more likely to fall for half-truths, illogical arguments, and lies. When you start to understand persuasion, you will have the skill set to pick apart the messages being sent to you and see why some of them are good and others are not.

Lastly, when we understand how persuasion functions, we’ll have a better grasp of what happens around us in the world. We’ll be able to analyze why certain speakers are effective persuaders and others are not. We’ll be able to understand why some public speakers can get an audience eating out of their hands, while others flop.

Furthermore, we believe it is an ethical imperative in the twenty-first century to be persuasively literate. We believe that persuasive messages that aim to manipulate, coerce, and intimidate people are unethical, as are messages that distort information. As ethical listeners, we have a responsibility to analyze messages that manipulate, coerce, and/or intimidate people or distort information. We also then have the responsibility to combat these messages with the truth, which will ultimately rely on our own skills and knowledge as effective persuaders.

Why is Persuasion Hard?

Persuasion is hard mainly because we have a bias against change. As much as we hear statements like “The only constant is change” or “Variety is the spice of life,” the evidence from research and from our personal experience shows that, in reality, we do not like change. Recent research, in risk aversion, points to how we are more concerned about keeping from losing something than with gaining something. Change is often seen as a loss of something rather than a gain of something else. Change is a step into the unknown, a gamble (Vedantam & Greene, 2013).

In the 1960s, psychiatrists, Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe, wanted to investigate the effect of stress on life and health. As explained on the Mindtools website: