Brought to you by:

Partners Healthcare System (PHS): Transforming Health Care Services Delivery Through Information Management

By: Richard M. Kesner

This case considers the process of organizational transformation undertaken by Partners Healthcare System (PHS) since the 1990s as their hospital and affiliated ambulatory medical practices have…

- Length: 15 page(s)

- Publication Date: Feb 26, 2010

- Discipline: Information Technology

- Product #: 909E23-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

This case considers the process of organizational transformation undertaken by Partners Healthcare System (PHS) since the 1990s as their hospital and affiliated ambulatory medical practices have adopted both EMR and CPOE systems. Encompassing a strategic investment in information technologies, wide-spread process change, and the pervasive use of institutional clinical decision support and knowledge management systems, this story has been 15 years in the making, culminating in 2009 with the network-wide use of EMR and CPOE by all PHS doctors. These developments in turn opened the door to the redefinition of services delivery and to the replacement of established therapies through the leveraging of the knowledge residing in 4.6 million now-digitized PHS patient records. As such, the PHS experience serves as a window into how one organization strove to address the daunting challenges of 21st century health care services information management, as a template for success in the implementation of large-scale information systems among research-based hospitals across the United States, and more broadly as a learning platform for industry executives in their efforts to transform health care delivery through data and knowledge management.

Learning Objectives

This case has a number of useful teaching applications. First and foremost, the PHS case describes the transformation of a health care services organization, enabled by the deployment of major medical informatics systems. This story serves as an example and even a model for similar courses of action across the health care services industry in the coming decade. From this perspective, the instructors and students who use this case study may explore the professional, ethical and business drivers behind the efforts by Partners HealthCare System to implement its version of the EMR, the Longitudinal Medical Record (LMR) system, and the CPOE system. Second and in a broader context, the PHS case is a study in organizational innovation and change in which a strategic investment in information systems aligned with the transformation of core clinical processes to improve the ways PHS delivers health care services. The resultant information technology platform both enabled day-to-day improvements in health care delivery and patient safety and afforded a rich knowledge base to inform best practices and innovation. Here too, students may consider the implications of change management at PHS. Lastly, the PHS case may serve as the basis for various learning exercises for management information systems (MIS) and computer science (CS) classes, where the story may be viewed through the lens of the system development or project management life cycle. In this approach, the instructor may decide to work with the class to address the related themes of successfully deploying enterprise resource planning (ERP), a decision support system (DSS) and a knowledge management system (KMS).

Feb 26, 2010

Discipline:

Information Technology

Geographies:

United States

Industries:

Healthcare service industry

Ivey Publishing

909E23-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Product details

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Sci Rep

- v.4(4); 2021 Dec

Improving primary health care through partnerships: Key insights from a cross‐case analysis of multi‐stakeholder partnerships in two Canadian provinces

Ekaterina loban.

1 St. Mary's Research Centre, Montreal Quebec, Canada

2 Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montreal Quebec, Canada

Catherine Scott

3 Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary Alberta, Canada

Virginia Lewis

4 Australian Institute for Primary Care & Ageing, La Trobe University, Melbourne Victoria, Australia

5 Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto Ontario, Canada

Jeannie Haggerty

Associated data.

The raw data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions given the small sample and the qualitative nature of inquiry.

Background and Aims

Multi‐stakeholder partnerships offer strategic advantages in addressing multi‐faceted issues in complex, fast‐paced, and rapidly‐evolving community health contexts. Synergistic partnerships mobilize partners' complementary financial and nonfinancial resources, resulting in improved outcomes beyond that achievable through individual efforts. Our objectives were to explore the manifestations of synergy in partnerships involving stakeholders from different organizations with an interest in implementing organizational solutions that enhance access to primary health care (PHC) for vulnerable populations, and to describe structures and processes that facilitated the work of these partnerships.

This was a longitudinal case study in two Canadian provinces of two collaborative partnerships involving decision makers, academic representatives, clinicians, health system administrators, patient partners, and representatives of health and social service organizations providing services to vulnerable populations. Document review, nonparticipant observation of partnerships' meetings (n = 14) and semi‐structured in‐depth interviews (n = 16) were conducted between 2016 and 2018. Data analysis involved a cross‐case synthesis to compare the cases and framework analysis to identify prominent themes.

Four major themes emerged from the data. Partnership synergy manifested itself in the following: (a) the integration of resources, (b) partnership atmosphere, (c) perceived stakeholder benefits, and (d) capacity for adaptation to context. Synergy developed before the intended PHC access outcomes could be assessed and acted both as a dynamic indicator of the health of the partnership and a source of energy fuelling partnership improvement and vitality. Synergistic action among multiple stakeholders was achieved through enabling processes at interpersonal, operational, and system levels.

Conclusions

The partnership synergy framework is useful in assessing the intermediate outcomes of ongoing partnerships when it is too early to evaluate the achievement of long‐term intended outcomes. Enabling processes require attention as part of routine partnership assessment.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the environment of increasing demands and limited resources, rapid technological change, and an aging and progressively complex patient population, partnerships involving multiple stakeholders from different sectors offer a meaningful way of tackling complex health care system problems. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Multi‐stakeholder partnerships including community members and representatives of academic institutions are prevalent across multiple disciplines and spheres. 5 To a certain extent, this can be attributed to the role of governments and funding agencies that mandate partnerships as an essential element of the programs and initiatives that they support. 4 , 5 For example, the Canadian Government has promoted collaboration as a means of improving the quality of health care provided to the Canadian population. 6 The partnership approach to health care system change and service redesign has also enjoyed widespread endorsement in other countries, particularly within the context of health and welfare services. 4 , 7

Partnership benefits have been studied from a diverse range of perspectives, disciplines, and communities of practice. 8 , 9 Academic literature outlines what constitutes an effective partnership and describes approaches and strategies to enhance partnership processes and to increase partnership effectiveness. 5 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 In theory, effective partnerships can be useful for overcoming organizational fragmentation and traditional divisions of power, improving communication and access to information, optimizing resource utilization, and helping to avoid a wasteful duplication of effort. 16 In addition, there is evidence to suggest that effective partnerships contribute to more comprehensive interventions, help to contextualize policy, and support the feasibility and relevance of research through direct involvement of knowledge users. 1 , 16 , 17 In primary health care (PHC), cross‐sector partnerships have been used to ensure integrated service delivery. 18 Reported facilitating processes include capitalizing on the diverse perspectives of partners, pooling of resources, promoting a common understanding of issues, forging common action plans, ensuring joint accountability and evaluation of progress, and employing appropriate forms of leadership and coordinating activities to ensure the alignment of efforts. 3 , 19

In practice, however, partnerships are frequently unable to generate effective collaborative advantage and achieve the intended change in systems and/or health outcomes. 19 , 20 Many crumble under challenges such as insufficient resources, significant time commitments, conflicting interests, problems with governance and leadership, lack of necessary skills, insufficient recognition, and lack of buy‐in from key stakeholders. 2 , 5 , 19 , 21 Considering these challenges, there is a growing need for evidence demonstrating the link between the implementation of processes and approaches that are claimed to enhance partnership effectiveness and the achievement of intended outcomes.

The notion of “partnership synergy” has been proposed as a marker or a “proximal outcome” of partnership functioning. 4 (p182) Partnerships are said to be synergistic when they combine resources successfully and mobilize the complementary knowledge and expertise of all the partners. 22 Synergy is reached when the combined efforts of partners enhance the outcomes beyond what could be achieved independently by each stakeholder/stakeholder group working toward the same goals, 23 namely that the whole becomes greater than the sum of the parts. 4 Synergy could manifest itself through creative and holistic ways of thinking, the ability to carry out more comprehensive interventions aimed at target populations, the relationships between partners and relationships of partnerships with the broader community. 4 Lasker et al identified a number of elements of partnership functioning that are likely to influence partnership synergy (Table 1 ) and suggested looking at synergy as a predictor of an effective partnership. 4 Subsequent research conceptualized synergy as being both a process and a product of partnership, and highlighted the dynamic and cumulative nature of partnership synergy demonstrating its capacity to build over time and its role as an evolving indicator of effectiveness and sustainability. 23 , 24 , 25

Determinants of partnership synergy (adapted from Reference 4 )

This study adopted partnership synergy as an umbrella framework for looking at the functioning of two multi‐stakeholder partnerships in two Canadian provinces involving stakeholders from different organizations and constituent groups with an interest in implementing organizational solutions to enhance access to appropriate PHC for vulnerable populations. The overall aim of our study was to gain an in‐depth understanding of the effectiveness of multi‐stakeholder partnerships in addressing complex issues in PHC. PHC is conceptualized here as an approach to health that encompasses continuous and comprehensive care across diverse curative, preventative, education, and rehabilitation services, with a person (micro), community (meso), and population (macro) orientation. 26 , 27 , 28 For the purposes of this paper, we conceptualize “partnership effectiveness” in relation to both the processes and outcomes of partnerships: the quality of the processes and relationships between partners and the health of the partnership on the one hand, and the realization of intended outcomes on the other. We define a multi‐stakeholder partnership as a complex human system based on voluntary collaborative relationships among stakeholders who agree to work together to achieve a common purpose and to share competencies, resources, responsibilities, risks, and benefits (adapted from Reference 29 ). We focused on partnerships involving representatives of different organizations—each bringing their unique perspectives, competencies, organizational mandates, interests and weaknesses, working toward a common goal of transforming PHC service delivery. The main research questions that this study attempted to address were as follows: (a) How does partnership synergy manifest itself in multi‐stakeholder partnerships? and (b) What structures and processes are required to build synergistic action among actors from different sectors?

2.1. Study context

This study was undertaken within a Canada‐Australia research program entitled “Innovative Models Promoting Access‐to‐Care Transformation” (IMPACT) conducted between 2013 and 2018. 30 The aim of this program was to design, implement, and evaluate, through a network of local partnerships, organizational interventions to improve access to appropriate PHC for vulnerable populations in three Australian states (Victoria, South Australia, and New South Wales) and three Canadian provinces (Quebec, Ontario, and Alberta). 30 Each of the six projects entailed identifying, in consultation with a broader set of local stakeholders, PHC access needs, and selecting, adapting, and implementing coordinated actions to best address these needs, within available resources. This study focused on two of the Canadian IMPACT local partnerships, namely the Primary Care Connection Partnership (PCCP) and the Community Health Resources Partnership (CHRP) (Table 2 ).

Overview of interventions in two Canadian IMPACT local partnerships (adapted from References 30 , 31 , 32 )

Abbreviation: PHC ‐ primary health care.

The stakeholders within each partnership included a mix of decision makers, clinicians, health system administrators, service providers, academic members—composed of academic investigators, including principal investigators and co‐investigators, and research coordinators, and, in some cases, members of vulnerable populations. 30 Vulnerable populations were “community members whose demographic, geographic, economic and/or cultural characteristics impeded or compromised their access to PHC.” 30 (p4)

2.2. Study design

This longitudinal case study 33 , 34 involved document review, nonparticipant observation 35 of partnerships' meetings, and semi‐structured in‐depth interviews 36 with a sample of study stakeholders in two partnerships. The study was conducted between August 2016 and September 2018. The rationale for studying both cases longitudinally was to follow their development over time, to understand the evolution of processes, to trace any changes that affected the partnerships, and identify how the partnerships responded to these changes. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research ( COREQ ) were used in the reporting of this study. 37

2.3. Sampling and recruitment

The PCCP stakeholders represented two administrative jurisdictions covered by two regional health networks, two local general practice divisions, community development organizations serving the two neighborhoods, and two universities. The CHRP included stakeholders from one health authority, a university, community and home care services, social and public health services, community health centers, information resources, primary care, and the community.

Interview candidates were selected using purposive sampling with the aim to achieve maximum variation within the sample. 38 The goal of the sampling strategy was to include representatives of each stakeholder group, who varied in seniority in the partnership and nature of engagement. The PCCP interview candidates were identified by the first author based on meeting observations; the CHRP candidates were identified by the CHRP principal investigator.

2.4. Data collection

Preliminary documents reviewed (between August 2016 and May 2017) were minutes of meetings, protocols, and reports produced by the IMPACT program and the two partnerships. The first author subsequently observed (between January 2017 and September 2018) 11 PCCP and three CHRP meetings—all available meetings that took place during this time frame. The document review and observations provided data on the operational elements, contextual factors, participants' roles and responsibilities, the common agenda of each initiative, and how this common agenda and the involvement of different stakeholders evolved since the start of the IMPACT research program in 2013. The first author then conducted (between July 2017 and March 2018) nine interviews with PCCP stakeholders and seven with CHRP stakeholders. Interview candidates were initially invited to participate via e‐mails that were sent by PCCP and CHRP research coordinators. Follow‐up contact by the first author was in person, at the end of partnership meetings, and via e‐mails sent directly to each candidate. The interviews lasted approximately 1 hour, were conducted either in‐person or over the telephone, and were audio‐recorded.

The interview guide (Appendix A ) was developed with reference to the literature on partnership synergy. 4 , 25 Synergy dimensions explored included the organization of partnerships, work sharing, decision‐making/problem‐solving, complementarity of skills, outcomes, and experience. The guide was pilot tested, in both English and French, prior to administration.

2.5. Ethics

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the St Mary's Hospital Centre Research Ethics Committee (No. SMHC‐13‐30C). Authorization to conduct research was obtained from the second participating institution. All participants were provided with written information about the study and consent was obtained prior to data collection.

2.6. Data analysis

Nonparticipant observations (which entailed observing participants without actively participating in their meetings) were recorded as field notes. All interviews were transcribed verbatim, in the original language, with subsequent translation from French into English for quotation purposes. Our analysis of notes and transcripts reflected the dual‐level inquiry of the study: it involved a cross‐case synthesis to describe the cases and generate insights 34 and framework analysis. 39 The strategy used for data analysis involved a hybrid deductive‐inductive approach, 39 , 40 involving assigning data into predefined themes based on the partnership synergy framework, revising themes based on nuances within the data, and identifying new themes arising from the data. The data were coded iteratively, going back and forth from text to themes. NVivo 12 software was used to support data management and analysis. The material was analyzed by the first author. Coding was verified with another co‐author. Emerging findings were discussed at regular team meetings. The final codes were grouped along the dimensions of partnership synergy and six categories of factors likely to foster synergy: structure; partner characteristics; partnership characteristics; relationships among partners; resources; and external environment.

3. FINDINGS

The following paragraphs detail the key findings from this study. Section 3.1 presents the characteristics of the sample. Section 3.2 summarizes the key findings and refers to descriptive cross‐case synthesis (presented in Appendix B ) that is based on observations and accounts of interview respondents. In Section 3.3 we elaborate on four themes that emerged from our data where partnership synergy was apparent, namely resource integration, partnership atmosphere, reported benefits, and partnership's capacity for adaptation to context. Finally, Section 3.4 describes partnership collaborative processes that enabled stakeholders from different organizations to achieve synergistic action.

3.1. Study participants

Interview participants represented a range of organizational expertise (Table 3 ). Academic representatives and decision makers constituted the largest two groups (n = 10, 63%). Participants (n = 16) were predominantly female (n = 13, 81%).

Study sample characteristics (n = 16)

3.2. Cross‐case synthesis

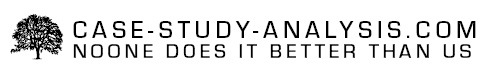

Our key findings are summarized in Figure 1 . It portrays human and material resources as the building blocks of partnerships. These resources are then activated via interpersonal, operational, and system‐level processes to produce partnership synergy. Partnership synergy manifests itself in different ways: in the integration of resources, partnership atmosphere, perceived stakeholder benefits, and the capacity for adaptation to context. It acts as both a dynamic indicator of the health of the partnership, highlighting the likelihood of achieving partnership effectiveness, and as the source of energy fuelling partnership improvement and vitality. The boundaries of the partnership are permeable, reflecting the exchange of influence between the partnership and its context. Appendix B displays how the cases align against the partnership synergy framework and describes how the two partnerships were resourced and structured.

Summary of key findings—relationships among partnership synergy, partnership resources, enabling partnership processes and outcomes

3.3. Partnership synergy

3.3.1. theme 1: resource integration.

There was evidence of partnership synergy in the integration of nonfinancial and financial resources. Nonfinancial resources included the time, knowledge, expertise, and connections that the stakeholders contributed, as well as the relationships and learning that transpired in the course of partnership work. The partnerships demonstrated capacity to recruit stakeholders with a range of perspectives, skills, information, and connections to a broader set of stakeholders and health systems exerting influence over the partnerships. These unique perspectives and insights (Table 4 ) were deemed to be complementary in that they allowed the group to explore the issues of access from various angles, to obtain timely information from different sectors in order to adapt interventions, and to enhance the relevance of interventions: “ I think it ' s a really good mix of people, and you can hear it in the discussion . The very different points of view and they all complement each other very well .” (016, CHRP).

Stakeholder perspectives within two Canadian IMPACT local partnerships

Abbreviation: IMPACT—Innovative Models Promoting Access‐to‐Care Transformation.

I honestly don't think that there's any other way to do it, because it's in primary care and primary care is incredibly complex, there are so many players involved […]. If we didn't have those other people at the table how would we know what's going on. (013, CHRP).

In both cases, the nucleus of the partnership, including the research team and a number of key nonacademic stakeholders, remained consistent over time, while new members were invited to join based on project evolution and the need to attract additional expertise and resources. This heterogeneity and fluidity in the composition of the partnerships reflected the complexity and scope of the tasks at hand, the dynamic nature of the projects and organizational and policy changes in the external context that took place over the years. These composition dynamics, however, necessitated a significant investment of coordination resources and time on the part of the research teams and ongoing attention to and management of stakeholder engagement dynamics.

The CHRP was larger, reflecting a broader array of stakeholders and language groups. Some CHRP interview participants felt that the size of the partnership (23 stakeholders) was too large, potentially inhibiting contribution from some members. The PCCP was smaller (13 members) but had the complexity of involving two independent health authorities, with different organizational cultures and authority structures, with one interview participant describing the partnership's initiative as “ one research project […] with two different speeds ” (011, PCCP). Despite the differences between cases in size and diversity, the mix of stakeholders in both was perceived by interviewees to be optimal for achieving project goals. The composition was described by stakeholders as an “ excellent mixture of people […] from diverse sectors ” (016, CHRP) and as “ driven by the research team, but nourished by the practitioners in the field ” (014, PCCP).

The partnerships demonstrated the ability to effectively combine their nonfinancial resources. In both cases, the level of engagement was deemed by most interview respondents to be appropriate for the stated project objectives and the function of the partnership. All stakeholders had clarity regarding their own roles and what was expected of them. Several participants referred to the alignment of efforts of partners and the richness and integrative nature of collaboration: “ These [partnership] tables are an example of integration . […] We become more integrated and stronger, and there is a certain level of coherence between us .” (020, PCCP); “ It is very rich . […] Not everyone has the same reality, and we inspire each other . In understanding the point of view of the other, we advance the discussion .” (014, PCCP).

Partnership synergy was also apparent in the ways partners leveraged financial resources and sustained partnership activities and interventions despite contextual challenges and funding gaps. The IMPACT research grant included funding for the coordinating infrastructure/research support, including the partnership coordinator position in each site, as well as the evaluation of interventions. There was no funding for intervention implementation, and stakeholders other than research coordinators were not remunerated for participation in partnership activities. Consequently, the successful implementation and sustainability of interventions relied entirely on the local players' capacity to commit to them, provide adequate resources, and maintain them beyond the life of the IMPACT research funding. Both partnerships devised low‐cost lay navigator models to address the needs of the target populations. Both worked toward integrating the interventions into existing health system organizational structures, aligning the proposed models with health system priorities. In the process, the CHRP relied on additional research funding that was secured early on in the project to support a randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness of the developed navigator model.

3.3.2. Theme 2: Partnership atmosphere

Partnership synergy was apparent in the quality of stakeholder relationships, in the perceived value of the initiative, and the general partnership atmosphere, which was described as “ positive ” (011, 018, CHRP), “ dynamic ” (017, CHRP), “ respectful ” (019, CHRP), “ open ” (013, PCCP), “ friendly ” (015, CHRP), “ collaborative ,” “ energising ” and “ engaging ” (013, CHRP): “ Everybody seems to be happy to be involved .” (018, CHRP); “ I usually see it as we all come together, sort of . I don ' t feel a sense of that there ' s some difference between anyone […] . I feel like they do treat me as an equal .” (019, CHRP).

The exchanges are very open. That is to say, when we […] put forth a proposal or a possible solution, it is always well received … not necessarily always accepted, but well received. Lots of openness. That, I find that interesting. (013, PCCP).

These positive collaborative relationships benefitted the partnerships by enabling more open conversations, faster and effective decision‐making, and enhanced project ownership: “ The commitment to the project is higher when you have built it together . […] When you have done it in collaboration, it is closer to your heart and I think that this is one of the advantages .” (012, PCCP).

The synergy in relationships blossomed with time; as the work progressed, participants felt that they could speak more openly, including voicing concerns and disagreement:

I have the impression that we are less afraid of losing our partners, we walk less on eggshells, we are more open […] the partnership is a little more solid and we are more capable of […] exposing a little, being less artificial in our meetings. (011, PCCP).

Participants highlighted the importance of face‐to‐face meetings and having signed letters of understanding with institutions at the start of the project. Despite the fact that membership fluctuated, these letters underscored the credibility of the project and facilitated trust‐building with new members.

3.3.3. Theme 3: Reported benefits

Members in both cases reported a variety of anticipated and actual benefits stemming from their participation in the project, reflecting a core component of partnership synergy. Participants described more professional than personal benefits. Benefits included, but were not limited to the following: learning about the work of other organizations and sectors; understanding how the services in one's organization complement services and approaches in others; learning about how a well‐organized meeting unfolds; devising more effective ways of addressing an issue that the organization had been grappling with; and ensuring system‐wide benefits if the project can demonstrate that the approach that is pursued works. In addition, respondents highlighted the benefits of the partnership approach to delivery of project goals, stating that “ there is no other way to approach it ” (013, PCCP). A number of indirect benefits were also reported, including enhanced visibility of one's own organization and opportunities for face‐to‐face exchange with other key stakeholders under the same organizational umbrella. Partnership members who were early career researchers were less positive about the benefits, citing high demands of participation for limited academic outputs. However, some of them remained committed to the partnership due to the strength of relationships with other stakeholders. While for most members participation in the project had been mandated by their respective organizations, the majority participated willingly, looked forward to meetings and saw a direct fit between the project's objectives and the priorities of the entities they represented. According to most interview respondents, the benefits of participation outweighed the drawbacks, effectively demonstrating positive partnership synergy.

The mutually beneficial nature of the partnerships was apparent as participants described mutual and personal learning and satisfaction with their involvement in the projects:

So to be able to be part of the project […] I think that they had a great idea, it's really smart, and I felt really glad to be part of that. You know because I feel like that's a good project […] very helpful, this is a very […] significant issue for people. And to be able to be part of maybe, you know, exploring why it's a problem and offering my insights, I'm very excited to be able to do that. (019, CHRP).

3.3.4. Theme 4: Capacity for adaptation to context

Partnership activities were unfolding within the context of health care system reforms in both provinces. Both partnerships had to make adaptations to the interventions to respond to evolving contextual opportunities and threats, but the extent of contextual impact and adaptation was far greater in the case of the PCCP, which demonstrated synergy in its ability to adapt to its changing context. During the implementation period, the province's health care system underwent a major reform, 41 , 42 leading to a number of policy changes. In the process, the partnership lost most of its nonacademic members, had to re‐develop relationships with new stakeholders, and had to modify the intervention several times to accommodate new system priorities. Academic partnership participants revealed that the impact of changes was so profound that they feared a complete dissolution of the partnership and termination of the project. These developments reflected weakened partnership synergy. However, the momentum generated through synergy in other areas, namely trust, partnership credibility, and organizational buy‐in, contributed to keeping the project alive:

[…] even though everyone around the table had changed, we have managed to keep representatives roughly the same from each of the organizations that were with us since the beginning. What made it easier was that we had the commitment of people pretty high up in those organizations […] In addition, we managed to establish a climate of trust. So even though the people around the table changed, they knew that the organizations had been there for a while and it was going well. (011, PCCP).

Given that contextual changes were frequent topics of conversation during face‐to‐face PCCP meetings, there were no reported differences in stakeholders' appreciation of the impact of context depending on their roles in the partnership.

The CHRP stakeholders described the context as “ chaotic ” (018, CHRP), with a well‐integrated hospital and specialist sector, poorly organized community health services, and fragmented primary care. At the time of project activities, the province underwent significant changes in its health care system, with services being integrated sub‐regionally based on geographical utilization patterns, within the framework of tight budgets, contract negotiations, and increasing demands on the system. It was felt that the project was timely in terms of addressing some of these challenges posed by changes in the context. The main concern voiced related to the possibility of the intervention duplicating existing services. The research team proactively addressed this concern by incorporating at the start of some partnership meetings a description of how the navigator model was different from and complementary to other services, and by allocating time for dialogue around it. At a closer, organizational, level the CHRP experienced a gap of 1.5 years between partner meetings due to delays in ethics protocols approvals. However, similar to the PCCP, the partnership synergy generated earlier, evidenced in the quality of stakeholder relationships and the importance attributed to the initiative, contributed to sustained stakeholder participation. Overall, the stakeholders' appreciation of the impact of external context on the project and partnership varied depending on their role in the partnership. Decision makers provided a more in‐depth assessment of the context and how it affected the intervention. Most stakeholders felt that contextual changes were inevitable, and the partnership just had to adapt to them: “[…] coping with the environment, the environment is what it is, it ' s a changing environment and you have to adapt ” (018, CHRP).

Interviewees also noted the influence of the partnerships and the interventions on their organizations and the broader context. Decision makers in particular referred to acquiring and sharing within their respective organizations a deeper understanding of the plight of vulnerable populations in relation to access issues. Members of community‐based service organizations referred to generating insights into how to improve their organizations' services, whereas family physicians became more aware of existing services that patients could be referred to.

3.4. Synergy enabling processes

Both partnerships employed specific processes to facilitate the work of the partnerships. The following main categories of processes emerged from our data: (a) interpersonal processes, (b) operational processes, and (c) system‐level processes (Figure 1 ).

3.4.1. Interpersonal processes

At the interpersonal level, participants highlighted the importance of communication processes, relationship building and maintenance, and learning loops. Both partnerships had open and multidirectional channels of communication, mostly confined to regular partnership face‐to‐face meetings and electronic means, to communicate internally with stakeholders within the partnership. Learning loops involved soliciting feedback during meetings around issues related to the project and being transparent about how this input was subsequently incorporated. External communication aimed at increasing the support for interventions, recruiting medical practices, and disseminating information about partnership activities and achievements to wider audiences. While some stakeholders had a history of working together, relationships with other stakeholders had to be built and nurtured. Face‐to‐face meetings were identified as being key to developing relationships.

3.4.2. Operational processes

At the operational level, the processes involved resource management, leadership, administration and management, and decision‐making. Both partnerships utilized a variety of ways to engage respective stakeholders. The partnerships organized deliberative fora involving a broad range of stakeholders, to learn about unmet health care needs of vulnerable populations, relevant community organizations, and available resources to support interventions. The PCCP subsequently involved stakeholders in various aspects of the research process, with a number of nonacademic stakeholders fulfilling tasks outside the partnership meetings. Conversely, the CHRP adopted a research advisory approach to working with stakeholders, with limited contribution of nonacademic stakeholders outside face‐to‐face meetings. Both partnerships used regular meetings to discuss project progress and to engage in collaborative learning. Participants emphasized the added value of acquiring relevant knowledge, having space to exchange with other partners, reflect and innovate (which was not always possible within the stakeholders' respective organizational contexts), as well as educational and capacity‐building opportunities.

The partnerships were largely driven by the research teams responsible for the overall management of the projects, providing strategic direction and facilitating the development of interventions at the local level, through continuous dialogue and learning, as well as sharing of information. The research teams capitalized upon the various strengths and perspectives of stakeholders, by providing sufficient time to discuss pressing issues, soliciting input from all stakeholders, offering stakeholders different mechanisms to contribute, and tailoring tasks to stakeholders' availabilities and interest. The PCCP leveraged the power of leadership distributed among academic and nonacademic stakeholders, while in the CHRP, the leadership was centralized within the research team. However, the CHRP interview participants reported that the research team seemed genuinely interested in hearing from all stakeholders and made efforts to check in with various groups around the partnership table.

A number of leadership processes were common to both cases. Both partnerships had formal and informal academic leaders knowledgeable about the context and skilled at mobilizing the various perspectives of partners. The leaders did not possess all of the required partnership‐related knowledge and skills at the outset, but made intentional efforts to learn from experience and best practices in partnership literature and to acquire additional skills through training. Moreover, as the partnerships evolved and the level of trust within teams increased, the leaders were more transparent about their own gaps in knowledge surrounding the interventions and eagerly welcomed input from different stakeholders. This demonstration of vulnerability contributed to creating further trust.

The PCCP stakeholders reported that the decision‐making process was inclusive and transparent, which was particularly useful in relation to adapting the intervention to its evolving context. Conversely, consistent with the advisory nature of the partnership, the CHRP decision‐making power was centralized within the research team.

3.4.3. System‐level processes

At the system level, participants described processes geared toward making ongoing adaptations to the evolving context. In both cases, responsiveness to external stimuli involved adaptations to the interventions' structure, implementation strategy, and personnel resources. Participants reported that processes such as conducting extensive fieldwork to gather information, having around the table a variety of key stakeholders with medium to high level of decision‐making power in their respective organizations, open dialogue about the evolving context, and, in the case of the PCCP, transparent processes of decision‐making, contributed to the ability of the partnerships to adapt interventions to rapidly changing policy contexts. The situational analysis involved leveraging the knowledge of multiple partners. The active engagement in the partnerships of decision makers and health system planners was critical in this respect, as it contributed to an in‐depth understanding of health system priorities.

4. DISCUSSION

This study illustrated the multidimensional, dynamic nature of partnership synergy and its role not only as a proximal outcome of partnership functioning but also as a facilitator of multi‐stakeholder partnerships in two geographical settings, in the context of tackling challenges in the delivery of high‐quality PHC to vulnerable populations. The study also provided insights into the structures and processes to sustain these partnerships. These two key findings are discussed in more detail below. Although there is a substantial number of quantitative and review studies that have incorporated concepts from the partnership synergy framework, 10 , 22 , 23 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 to our knowledge, empirical studies applying these concepts to frame qualitative research findings are rare, with Brush et al 24 and Corbin and Mittelmark 48 being two examples of such studies, which also proposed synergy models. Employing the partnership synergy lens allowed us to systematically assess its manifestations and to acquire a deeper understanding of this phenomenon. Taking into consideration that the partnerships were in the implementation stage of their interventions, we could not comprehensively assess the intended partnership outcomes. Our data contained preliminary evidence of the positive impacts of the interventions in both cases. However, the sustainability of interventions and partnerships beyond the life of the IMPACT grant was, according to our interview respondents, questionable.

This study will be followed by a quantitative study involving all six IMPACT partnerships that will attempt to measure whether (and how) the partnerships have achieved partnership synergy and whether certain partnership processes contributed to more strategic advantages. The results pertaining to the outcomes of the developed IMPACT interventions will be reported elsewhere. 49

4.1. Partnership synergy

Our first key finding relates to the multidimensional nature of partnership synergy. Our data indicate that partnership synergy manifests itself in different ways. We identified the following four areas where partnership synergy was apparent: (a) the integration of nonfinancial and financial resources, (b) partnership atmosphere, (c) reported benefits, and (d) capacity for adaptation to context. Our analysis revealed the complex interactions among the four areas. The composition that reflected the diversity and complexity of the presenting problem allowed for faster adaptations to contextual stimuli. The generated benefits were critical to the sustained level of stakeholder commitment. The quality of collaborative relationships and positive partnership atmosphere facilitated additional stakeholder recruitment and allowed to maintain momentum. These inter‐connections suggest that synergy components are neither static nor independent; similar to a hologram, 50 they allow us to obtain a more intense picture of partnership synergy. Given the highly contingent nature of partnerships, there will arguably be other areas where synergy might manifest itself, depending on a partnership's objectives and internal and external influences. The original Lasker and Weiss's model (2001), viewing partnership synergy as an outcome, for example, placed more emphasis on outcome elements, such as the ability of developed strategies to address the needs of target populations.

Second, our findings highlight the dynamic nature of partnership synergy. As partnerships progressed, partnership synergy in both partnerships fluctuated. Both partnerships evolved from a group of individuals with common interests (low synergy) into entities with a requisite degree of openness, inter‐dependence, and enhanced understanding of presenting issues (higher synergy)—all of which contributed to deeper decision‐making and effective adaptations to intervention models. Conversely, partnership synergy could weaken, as was illustrated with an example of the profound impact on the PCCP of its volatile context. This finding is broadly consistent with prior research that suggested that synergy was a dynamic health indicator of a collaborative process 24 and that it was more likely to accrue during the formation stage of the partnership but subsequently decrease during the implementation stage. 51

The third characteristic of partnership synergy revealed in our analysis is the contribution of partnership synergy to sustaining partnerships. The composite strength of partnership synergy in the PCCP was sufficient to offset the impact of the destructive contextual circumstances and allowed the partnership to regenerate itself. Analogous to the body's immune system, partnership synergy appeared to provoke a protective response allowing the partnership to persevere in the face of adversity. In addition, partnership synergy contributed to partnership improvement. Given that working in partnership required skills that were different from those employed in the typical running of research studies, the partnerships made strategic financial investments into acquiring these new skills. Instead of outsourcing certain partnership‐related tasks, the partnerships built capacity in‐house through training partnership coordinators in group process facilitation techniques and then providing them with opportunities to facilitate partnership meetings. This investment was not only part of building capacity within the partnership; the coordinators used the training as a springboard for subsequent process improvements and self‐organization that benefitted the partnerships directly, strengthening them and contributing to synergy. The return on this investment was high and contributed to lower effort on the part of academic investigators to facilitate partnership activities.

4.2. Structures and processes

This study adds depth to understanding of partnership resource requirements and demonstrates the centrality of enabling processes at the interpersonal, organizational and system levels to achieve synergistic action among multiple stakeholders. Due to the organizational structure and type of the IMPACT program funding, the two partnerships under investigation were largely driven by the research teams that initiated the partnerships—a finding that is consistent with the literature on collaborative health research partnerships. 17 These research teams and a number of key nonacademic stakeholders constituted a relatively consistent continuous core in each partnership, effectively acting as “champions” keeping the collaboration going. 52 Other members were selected strategically, to attract specific expertise, perspectives, and additional resources. This was supplemented by more organic selection based on emerging needs as the projects unfolded. The dynamic composition allowed for fluidity, complementarity, and heterogeneity that reflected the critical dimensions of the problem to be addressed and of the changing context. Having stakeholders around the table with medium to high level of authority in their respective organizations allowed for timely adaptations to interventions.

The CHRP was larger than the PCCP, reflected more linguistic diversity, and had more permeable organizational boundaries due to receiving additional funding for the second phase of the research project. This independent funding added complexity by broadening the scope of the project and requiring the involvement of additional expertise. The partnership's size necessitated a higher degree of formalization, which was evidenced in the structured ways of organizing meetings and soliciting input from stakeholders. This finding is consistent with the argument from organizational theory that larger organizations tend to require more formalized behavior and more developed administrative components. 53 Different stakeholders were brought in as the needs of the partnership evolved, with relatively consistent representation from the target population. The partnership adopted a research advisory approach, with the decision‐making power centralized with the research team, and a limited contribution of nonacademic stakeholders outside the face‐to‐face meetings. Overall, the project undertaken by the CHRP was deemed by interview respondents to be meaningful and timely.

The PCCP was smaller, with more defined boundaries, but had a higher degree of internal complexity due to working with two local health authorities, each with different organizational cultures and processes. The PCCP exhibited elements of horizontal decentralization 53 and holographic organization, 50 with the diffusion of leadership and decision‐making power among academic and nonacademic stakeholders. All stakeholders participated actively in the co‐construction of the various aspects of the project, and some nonacademic stakeholders fulfilled tasks outside the partnership meetings. The small size and decentralization of power allowed the PCCP to remain nimble and responsive to change. These findings are aligned with organizational theory that states that more complex and dynamic environments necessitate more organic and decentralized structures and decision‐making power. 53

We identified a number of collaborative processes driving the synergy of the two partnerships, at interpersonal, operational, and system levels, each a critical piece of the synergy puzzle, but also a source of potential problems if misaligned with the needs or context. For example, the decentralized form of leadership that contributed to partnership synergy in one partnership may have been counterproductive in the other. In practice, however, the key contributor or threat to partnership synergy cannot be isolated due to the inherent complexity of partnerships within their local contexts. “Because an element in a group can affect other elements, any element or combination of elements could be contributing to the group's ineffectiveness.” 54 Our study demonstrated how contextual adaptation in the case of the PCCP necessitated certain decision‐making processes, appropriate forms of communication, and specific actions from the team that fulfilled the “backbone” 3 coordinating support to the partnership. This interaction of process variables is not confined to the partnership itself, for partnerships are subject to the influences of their constituent organizations and larger contexts. When partnerships experience decreased synergy, our evolving model of synergy (as depicted in Figure 1 ) can support the diagnostic task of identifying the sources of the problem and the task of devising solutions to address it, paying particular attention to the interplay of variables.

The optimal configurations of these processes and their interaction with partnership resources and context can be highly variable, depending on the specifics of each partnership. 43 Indeed, as the IMPACT program progressed, each of the partnerships under our investigation evolved in different ways, based upon the specific context within which it was developing, the local access need that the partnership tried to address, tailored processes and requirements to meet this need, and the relationships that formed to move the work forward. In participatory research terms, the PCCP stakeholder participation exhibited elements of “co‐construction” or “co‐governance,” whereas in the CHRP it was more aligned with “consultation.” 55 Each of these configurations fit the objectives and the needs of the respective partnerships. Our findings support prior research that highlights that partnership as a form of multi‐organizational working relationship is a variable concept and works differently under different circumstances. 56 , 57

It is important to note that an in‐depth exploration of the challenges of partnering was beyond the scope of this study. The main challenges reported by our study participants included the following: considerable time commitments, insufficient credit for investing energy into the partnership, challenges with bridging organizational divides, and difficulties optimizing the involvement of knowledge users (the people affected by the partnership's work). These obstacles affected some stakeholders' motivation, their level of participation, and, subsequently, partnership synergy. These findings indicate the importance of devoting attention to the balance of costs and benefits and recognizing and responding to perceived and actual disengagement throughout the life of the partnership.

4.3. Implications for practice and future research

The partnership synergy framework 4 is useful in assessing the intermediate outcomes of ongoing partnerships when it is too early to evaluate the achievement of long‐term intended outcomes. It should be incorporated into routine partnership evaluation, starting with a baseline assessment. The list of variables offered by the framework allows partnership practitioners and evaluators to select those relevant to a particular partnership, identify the levers of change, and calibrate inputs accordingly in an attempt to increase partnership synergy. Future research should focus on identifying other manifestations of partnership synergy and documenting conditions under which these manifestations emerge. The ultimate objective would be to determine if partnership synergy could indeed become a source of “renewable energy” for a partnership. It would equally be important to document instances of negative partnership synergy or antagony 48 and identify “tipping point” scenarios where the composite partnership synergy no longer offers its protective effect.

4.4. Limitations

This section outlines the limitations of this study and how these limitations were mitigated. First, the study of the partnership aspects was largely conducted by one member of the research team (the first author). Individual biases may have affected the coding and interpretation of data. However, the first author is experienced in qualitative data gathering, coding, and analysis. In addition to being exposed to the partnership phenomena over a prolonged period of time, the following strategies were employed to reduce the effect of investigator bias: (a) triangulation from multiple sources of evidence, and (b) keeping an “audit trail” to document decisions made throughout the research process. 58 Moreover, the coding frames and analytic plan were developed and validated with other members of the research team. Second, participants may have provided a more favorable assessment of the partnerships, given the voluntary nature of engagement and the stage of the partnerships by which those who did not see value in participating would have resigned. We attempted to minimize this limitation through the use of purposive sampling, which enabled the selection for interviews of a mix of seasoned and new partnership participants and those demonstrating high and low levels of participation. In addition, the semi‐structured interview format allowed the interviewer to explore negative cases. Third, this study analyzed only two of the six IMPACT local partnerships and just some of the partnership manifestations. Some important aspects of partnership functioning may not have been captured. The two partnerships were chosen in light of feasibility considerations, and the partnership dimensions were selected in alignment with the chosen theoretical framework. This study will be followed by a quantitative study involving all six IMPACT partnerships. Finally, the study unfolded within the context of a funded program of research with a targeted scope to improve accessibility to PHC for vulnerable populations. Caution is warranted when transferring these results to different, less resourced contexts. Rich contextual descriptions were provided for each of the two IMPACT local partnerships allowing other scholars and practitioners to determine whether and how the results may be applicable in different contexts.

This research would not have been possible without the support of the IMPACT program's funders. IMPACT—Improving Models Promoting Access‐to‐Care Transformation program was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (TTF‐130729) Signature Initiative in Community‐Based Primary Healthcare, the Fonds de recherche du Québec ‐ Santé and the Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute, which was supported by a grant from the Australian Government Department of Health, under the Primary Health Care Research, Evaluation and Development Strategy. Ekaterina Loban would like to acknowledge funding of a doctoral stipend through the IMPACT research program (2015‐2018). The funding bodies played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors of this paper have no conflict of interest to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Ekaterina Loban, Catherine Scott, Virginia Lewis, Susan Law, Jeannie Haggerty.

Data Curation: Ekaterina Loban.

Formal Analysis: Ekaterina Loban.

Funding Acquisition: Catherine Scott, Virginia Lewis, Jeannie Haggerty.

Investigation: Ekaterina Loban.

Methodology: Ekaterina Loban.

Project Administration: Ekaterina Loban.

Resources: Catherine Scott, Virginia Lewis, Jeannie Haggerty.

Supervision: Catherine Scott, Jeannie Haggerty.

Validation: Ekaterina Loban, Catherine Scott, Virginia Lewis, Susan Law, Jeannie Haggerty.

Writing–Original Draft Preparation: Ekaterina Loban.

Writing—Review and Editing: Ekaterina Loban, Catherine Scott, Virginia Lewis, Susan Law, Jeannie Haggerty.

All authors agreed on the order in which their names are listed in the article.

I, Ekaterina Loban (the corresponding author), confirm that I had full access to all of the data in the study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

We confirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research would not have been possible without the support of the IMPACT program research team and all stakeholders who were involved in this study. We also acknowledge the contribution of the following supporting partners: the Department of Family Medicine of McGill University, St. Mary's Research Centre, Université de Sherbrooke, Bruyère Research Institute, PolicyWise for Children & Families, Monash University, La Trobe University, the University of Adelaide, the Bureau of Health Information, and the University of New South Wales.

APPENDIX A. INTERVIEW PROTOCOL

As you are aware, each IMPACT site has established a local innovation partnership (LIP)—partenariat d'innovation local (PLI). These look slightly different in each of the six sites. The first couple of questions are just to get an initial picture or overview of “what” it is and how you are involved.

- When you say “your LIP” or “the LIP” what are you referring to?

- How long have you been involved with your LIP?

Work sharing:

- How is the work divided among the different partners?

- How would you describe the roles of members? How do they contribute?

Decision‐making/problem‐solving:

- 4 Can you name 2 to 3 significant decisions that were made in the past year?

- 5 How are decisions made? How are decisions communicated? (prompts: committee process; voting/consensus; transparency).

- 6 How are challenges resolved/ conflict dealt with?

- 7 Can you name 2 to 3 significant problems encountered in the past year? How were they resolved? (if appropriate: What were the consequences of conflict or efforts to resolve problems [benefits, risks]?)

Complementarity of skills:

- What facilitates member contributions?

- What limits member contributions (barriers)?

- 9 How is the partnership including the views and priorities of the people affected by the partnership's work?

- 10 Has there been any change over time in terms of how team members contribute?

Benefits/value added:

- How do you benefit (professionally/personally)?

- How does your organization benefit (policy/practice/service delivery)?

- 12 How do you perceive that others are benefitting from their participation?

- 13 What sorts of benefits do you perceive that are above and beyond what might have been expected as a result of working in this partnership, as opposed to working independently? If yes, could you provide a few examples? If no, are there any limitations that you can think of?

- 14 What is the LIP trying to achieve?

- 15 Does it seem as if everyone understands and supports these goals (ie, Is everyone headed in the same direction)?

- 16 How would you describe the LIP's progress toward these goals to date?

Experience:

- 17 How would you describe your overall experience of being part of this LIP?

- 18 What has been the most positive aspect of your involvement?

- 19 What has been the most negative aspect of your involvement?

- 20 Do you look forward to the meetings of the LIP? Why or why not?

- 21 What words would you use to describe the general atmosphere of the LIP (eg, level of energy surrounding the LIP)

Synergy‐promoting strategies (enablers and barriers to partnership):

- 22 Describe the processes and approaches that have been used to facilitate the work of the LIP.

- 23 What's working well? How do you know (are there any indicators of success)?

- 24 From your perspective, what might be improved? And how? What would make your LIP more effective?

- 25 Is there anything else that you would like to mention?

APPENDIX B. CROSS‐CASE SYNTHESIS HIGHLIGHTING FACTORS FOSTERING/HINDERING PARTNERSHIP SYNERGY, INCLUDING ILLUSTRATIVE QUOTATIONS

Abbreviation: IMPACT ‐ Innovative Models Promoting Access‐to‐Care Transformation.

Loban E, Scott C, Lewis V, Law S, Haggerty J. Improving primary health care through partnerships: Key insights from a cross‐case analysis of multi‐stakeholder partnerships in two Canadian provinces . Health Sci Rep . 2021; 4 :e397. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.397 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Funding information Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Grant/Award Number: TTF‐130729; Fonds de recherche du Québec ‐ Santé; Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Partners Healthcare System Case Solution & Answer

Home » Case Study Analysis Solutions » Partners Healthcare System

Partners Healthcare System Case Study Analysis

PARTNERS HEALTHCARE SYSTEM (PHS): TRANSFORMING HEALTH CARE SERVICES DELIVERY THROUGH INFORMATION MANAGEMENT

The Partners Healthcare System (PHS) faced a lot of obstacles in implementing the ERP system whose sole responsibility was to make the current processes as efficient as possible. In addition to this, once this information system is along with Computerized Patient Order Entry (CPOE) system then it would help the health care professionals in accessing patient complete profile from the scratch that is the patients’ first visit to the health practitioner. However, there was a lot of resistance regarding the system from the doctors. It is reported that two-third of the doctors had prior links to the hospitals and were hesitant to adopt the latest technology. In addition to this, the same number of doctors who had affiliations with the PHS hospital also met their patients at some other venues.

The already established workforce lacked in its ability to use the advanced technology and was reluctant to this type of system. As they were trained to write prescriptions manually, hence they were not accepting this new mode of data reposition. In addition to a lack in ability to apt the latest technology, they also lacked the basic infrastructure or resources to finance this implementation. Moreover, if the technology gets implemented then the lack for support and after implementation maintenance was another problem. This further declined their ability to pursue new treatment techniques and methods, or prescribe new drugs that would be of great help to the patient rather than giving the traditional prescriptions. As these practitioners were not at all technology savvy, hence, another reason to be concerned was their ability to type and see and the customer. This reflects the practitioner’s inability to be multi-tasker.

In addition, last but not the least is the cost of implementing the module. As calculated through the case study, the cost to implement such ERP coupled with CPOE was $40,000 per doctor, hence, making it hard for a primary physician to afford its integration. Moreover, the existing practitioners found it a threat to the current practices that hurt their profits later. Traditionally, the authority was assumed to be the central figure but after this, implementation was assumed to be decentralized.

Question 02

From a project management perspective, the system deployment factors that appear to be present in case of Partners Healthcare System (PHS) includes value added service to the patient on one hand and on the other hand it would increase the experience of the doctor or practitioner himself. Equipped with the full details of the history of the patient at disposal, the complete description of the patient’s medication and the performance evaluation of the drug on the patient during the treatment through the notes would add value to the doctor’s experience as well. In addition to this, another important factor that was assessed in the implementation of the system is that doctors get advice on the new drugs and the compatibility with the disease being cured that makes the process more helpful for him. The system is updated on a regular basis to incorporate the addition of the new drugs and the subtraction of the obsolete ones from the market that makes the process more efficient.

This system would help the doctor diagnose the disease and the cure in a more technologically updated fashion rather going through the manual process and enhancing their knowledge base for the cost effectiveness of the new therapies. This would also help them in serving the cost related issue of the patients who are unable to afford the expensive therapies. The system would generate the best optimal solution and the therapy for the patient according the patient budget, which is a true reflection of an intelligent system.

This would help the heath care centers speed up the process of data reposition and making the system develop sets of recognized and recommended therapies. This hassle free process, of automation of the health care system was best to become cost effective as it would help boost the patients’ diagnosis and treatment within a few seconds. It would help extraordinary implications in a shorter time frame and help elevate success path for those, who support the change in the organization.

Along with the fringe benefits of this technology, system deployment factors appear to be absent in the implementation that include lack of financial incentives for those who are a part and parcel of the organization for a relatively longer period of time. The Partners Healthcare System (PHS) was a decentralized one, therefore, the change needed to be done to the organization that was centralized in the past. In addition to this, the power to implement the system lies in the hands of the medical practitioner; therefore, before implementing the system it was a pre-requisite to make the management accept the change, which would be the ultimate success of the implementation…………………..

This is just a sample partical work. Please place the order on the website to get your own originally done case solution.

Related Case Solutions:

LOOK FOR A FREE CASE STUDY SOLUTION

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- August 2005 (Revised May 2007)

- HBS Case Collection

Partners Healthcare

- Format: Print

- | Pages: 14

About The Author

Joshua D. Coval

More from the author.

- February 2023

- Faculty Research

Success Academy Charter Schools

- December 2022

Managing Pain in the Midst of an Opioid Epidemic

- Success Academy Charter Schools By: Robin Greenwood, Joshua D. Coval, Denise Han, Ruth Page and Dave Habeeb

- Success Academy Charter Schools By: Robin Greenwood, Joshua Coval and Denise Han

- Managing Pain in the Midst of an Opioid Epidemic By: Joshua D. Coval, Richard S. Ruback and Christopher Diak

Information Management Strategy: PHS Clinic Case Study

Before the introduction of the LMR and the CPOE systems into the company’s framework, the PHS Clinic was an exact representation of a company, whose decision-making process was based on the principles of a traditional, non-computerized approach to data management, which caused numerous issues in data accuracy and patient safety.

The incorporation of the LMR and the CPOE approaches allowed for designing an entirely different strategy for information management, In other words, the latest information technology innovations could be incorporated into the framework of the organization so that the process of information transfer could become easier and safer.

The investment, which the company’s leadership had to make into the process of enhancing the quality of the service delivery and increasing the rates of patient satisfaction, allowed the company to propel itself into a new stage of development, which involved digital communication.

The fact that the organization managed to allocate its costs in a proper manner and, therefore, make a reasonable investment into the further progress, can be viewed as the key factor promoting the further redesign of the information system.

The formalities related to the staff’s affiliation to the PHS management style, the use of out-of-hospital offices by the latter, the absence of the relevant technology and skills among the local doctors, the reluctance of the staff to learn new skills, and a comparatively high cost of the overall change can be viewed as the key impediments to the change.

The transformation in question allowed for making impressive changes in the design of the organization and the attitude of the staff towards technology. Specifically, the incorporation of the IT architectural framework, which helped the staff get accustomed to the alterations, the design of a specific code for the staff to collaborate efficiently, the design of the governing systems, and the integration of quality assurance tools deserve to be mentioned.

Improving the process of data management on an enterprise-wide level is fraught with a range of issues, including the problem of training the staff and making sure that every single member has been made aware of the specifics of the new information management approach.

The process of establishing the decision support system in the specified environment, however, is associated with a range of difficulties, the need for creating the corresponding tools, to design a new approach towards establishing the patient-therapist relationships, and the introduction of the new information management principle into the framework, to name a few.

The integration of an information management platform can definitely be viewed as a major success factor. However, the fact that the staff will have to adapt to significant changes and, therefore, make mistakes in the process, is a huge downgrade.

The elimination of the key risks, which the architectural design allows for, can be explained by the fact that the specified approach helps not only locate the key variable, but also identify the relationships between them instantly.

Reducing the key costs spent on the design of the solutions for addressing specific issues within a community, research and development centres fully justify their existence.

The PHS management will have to locate the ways of promoting change among the reluctant staff. The healthcare practitioners will need to incorporate entirely new approaches into their practice, thus, facing the risk of delivering poor services, while the allied agencies interacting with the PHS may be liable in case the latter fail. Thus, the TCO implications can be considered rather high.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, April 14). Information Management Strategy: PHS Clinic. https://ivypanda.com/essays/partners-healthcare-a-case-study-analysis/

"Information Management Strategy: PHS Clinic." IvyPanda , 14 Apr. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/partners-healthcare-a-case-study-analysis/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Information Management Strategy: PHS Clinic'. 14 April.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Information Management Strategy: PHS Clinic." April 14, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/partners-healthcare-a-case-study-analysis/.

1. IvyPanda . "Information Management Strategy: PHS Clinic." April 14, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/partners-healthcare-a-case-study-analysis/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Information Management Strategy: PHS Clinic." April 14, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/partners-healthcare-a-case-study-analysis/.

- Usability of Computerizes Provider Order Entry Systems

- Safety Score Improvement Plan for St. Vincent Rehabilitation Center

- Paper-Based Methods and E-prescription: Evaluation Project

- The Mitochondria and Autism - Results and Main Function

- Debates on Euthanasia - Opposes the Use

- The Function of Kinase Inhibitor Staurosporine in Healthy and Disease States

- Ways of Improving the Communication Process in Health and Social Care Setting

- Barriers to the Use of Technology to Support Users of Health and Social Care

- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

Partners HealthCare System Inc. (A)

Subjects Covered Capacity planning Competition Mergers Operating systems Organizational change

by Gary P. Pisano, Maryam Golnaraghi

Source: Harvard Business School

23 pages. Publication Date: Feb 16, 1996. Prod. #: 696062-PDF-ENG

Partners HealthCare System, Inc. (A) Harvard Case Study Solution and HBR and HBS Case Analysis

Related Posts

You may also like

Congo River Basin Project: Role for Dr. Beni

Subjects Covered Decision making Nongovernmental organizations Nonprofit organizations Social enterprise Tradeoff analysis by Kathleen L. McGinn, Deborah M. Kolb, Cailin B. Hammer, […]

Financing Entrepreneurial Ventures Business Fundamentals Series

Subjects Covered Business plans Development stage enterprises Entrepreneurial management Venture capital by William A. Sahlman, Howard H. Stevenson, Amar V. Bhide, James […]

Hewlett-Packard: Manufacturing Productivity Division (D) Glossary

Subjects Covered Applications Interdepartmental relations Product development Product lines R&D by Benson P. Shapiro Source: Harvard Business School 2 pages. Publication Date: […]

Kirk Stone (B)

Subjects Covered Career planning Personal strategy & style Values by Vijay V. Sathe, Robert Mueller Jr. Source: Harvard Business School 3 pages. […]

- Predictive Analytics Workshops

- Corporate Strategy Workshops

- Advanced Excel for MBA

- Powerpoint Workshops

- Digital Transformation

- Competing on Business Analytics

- Aligning Analytics with Strategy

- Building & Sustaining Competitive Advantages

- Corporate Strategy

- Aligning Strategy & Sales

- Digital Marketing

- Hypothesis Testing

- Time Series Analysis

- Regression Analysis

- Machine Learning

- Marketing Strategy

- Branding & Advertising

- Risk Management

- Hedging Strategies

- Network Plotting

- Bar Charts & Time Series

- Technical Analysis of Stocks MACD

- NPV Worksheet

- ABC Analysis Worksheet

- WACC Worksheet

- Porter 5 Forces

- Porter Value Chain

- Amazing Charts