21 Advantages & Disadvantages of New Media (College Essay Ideas)

When writing a college essay on new media, make sure you cover the following points. These points can help you add depth and detail to your essay.

To write a strong essay, I recommend paraphrasing the following points and turning each point into a full paragraph . Provide clear examples and reference a source for each paragraph. You can use the sources listed below, but remember to use your college’s referencing style when citing your sources.

There are both pros and cons of new media. So it’s important to give a well-rounded analysis that shows you have considered your essay from both old and new media perspectives.

Old Media vs New Media

Here’s the difference between old and new media:

- Old media are media that were owned and controlled by large companies and disseminated through one-way communication methods. Examples include newspapers, film and television.

- New media are media that can be produced and distributed digitally by anyone with an internet connection and generally involve two-way communication. Examples include blogs, social media (like Facebook and Twitter) and online forums.

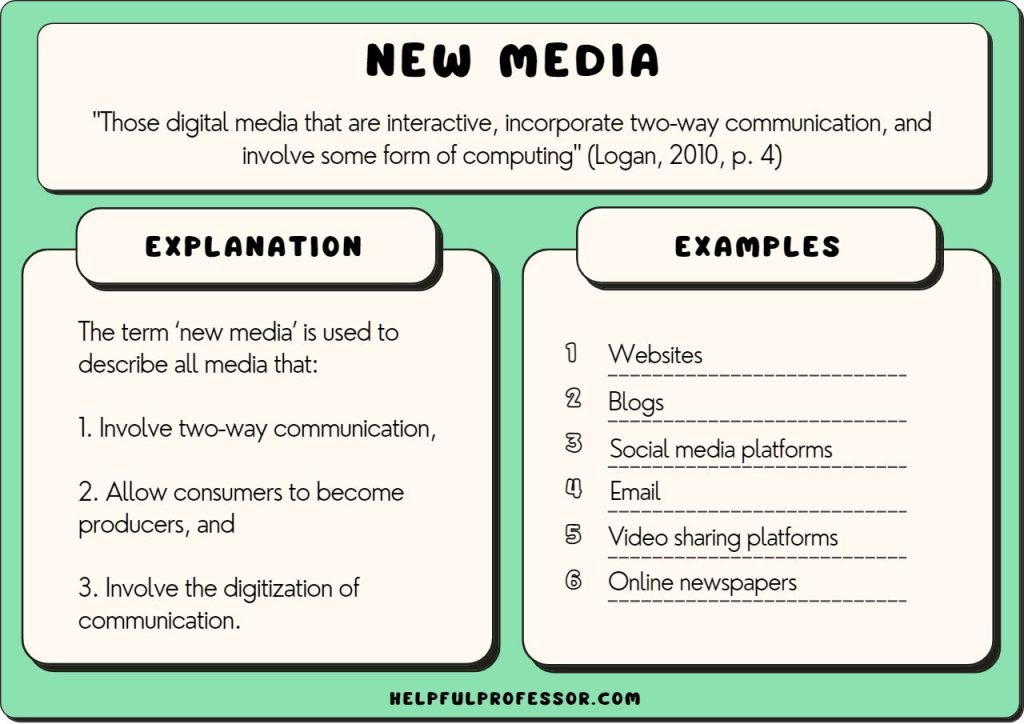

My favorite definition is from Logan (2010, p. 4) :

“The term ‘new media’ will generally refer to those digital media that are interactive, will incorporate two-way communication, and involve some form of computing.”

New media like Facebook and Twitter have made communication, socialization, sharing and interacting easier for people with an internet connection. We can now not only be the consumers of information but also information producers . Sharing news, thoughts and opinions to a global audience is no longer something only the rich and powerful can do. Anyone with a Twitter handle how has global reach.

Advantages of Old Media

1. Old media have broad reach. Old media were designed as a form of mass communication that was to be broadcast to the masses. From the invention of the printing press in 1440 to the 1980s, print media such as newspapers, then radio, and finally television, followed this same broadcast formula. One message was broadcast to an entire population of a nation. People of all ages got their news from a small amount of publications that had extremely broad reach across a population.

2. Urgent information is broadly dispersed. A follow-up benefit of this broad reach of old media was that information of public importance was distributed rapidly. Still today, when a public disaster occurs, most people turn to old media of television and radio to get important information from authorities. This information is often controlled by, distributed by, and policed by the government so everyone gets the same information about how to protect themselves during times of emergency.

3. The people who control news dissemination are authorities and experts. Old media has important gatekeepers (Carr, 2012) to ensure the quality and authenticity of information. Published information is parsed by editors and producers to ensure it is true. People along the information supply train are trained and experienced journalists, and their editors provide checks and balances to what is distributed in newspaper, radio and television broadcasts. By contrast, new media can be produced and disseminated by anybody with an internet connection, leading to misinformation. This is one possible con of the internet .

4. Extreme views do not spread easily. Because of the control that gatekeepers exert over old media, unfettered media bias , extreme and radical opinions are curtailed. Untrue information can be prevented and filtered and offensive information can be bleeped out to protect children. Unfortunately with the rise of social media, our world has become increasingly polarized and radicalized (Thompson, 2011) . This is largely due to the fact those gatekeepers aren’t there to provide quality control for information anymore.

5. A sense of community and social cohesion develops. Benedict Anderson (1983) theorized that the emergence of the printing press led to the concept of the ‘nation’. He said that when people of a nation all started to read the same information each day, they began to see themselves as a community. Before then, our sense of community was to people in our villages. After that, we saw ourselves as an “imagined community” who share a common set of values and culture.

Related: Imagined Communities Pros and Cons

Disadvantages of Old Media

6. Minority views can be marginalized. There is extensive literature that shows that people of color, women, and other minorities have had their views curtailed and silenced in old media. Instead, dominant views are perpetuated by old media. Critical theory and post-structuralism (inspired in large part by Michel Foucault) have long stressed that media has produced unfair stereotypes and narratives about minorities. Old media were complicit in the reproduction and normalization of ‘dominant discourses’, and have long silenced minority or unpopular opinions.

7 The government and oligarchs often control the message. Throughout the 20th Century, the ability to share information was controlled by a small group of people. This helped them to maintain their power. In Manufacturing Consent , Herman and Chomsky (2010) highlight how corporate America and media oligarchs (such as Rupert Murdoch) have had a mutually beneficial relationship where they perpetuated untruths and propaganda in order to maintain their positions of power in society. To a greater extreme, in socialist nations, governments literally censor the ‘old’ press and only allow favorable media coverage.

8. Old media don’t get much instant feedback. Today, when you broadcast something on the internet, it gets comments and re-tweets to provide the writer with instantaneous feedback. This isn’t the case with traditional media like television , which broadcast information without an instantaneous response (one exception might be talk back radio). Interestingly, many major communication models in the 20th Century that had a linear structure (e.g. the Laswell model and the Shannon-Weaver model ) are largely outdated due to the two-way communication features of new media.

9. People don’t listen to or respect old media anymore. The declining trust in expertise and authority is widely a result of the emergence of new media. As previously marginalized and even extreme voices have been magnified by new media, people have started turning away from old media and considering it to be elitist and untrue. Whether these claims are accurate or not, the declining trust in old media means it doesn’t have the clout it once did.

Advantages of New Media

10. Information production is no longer just for the elites. In the era of blogs, social media , and instant communication, elites and the powerful no longer hold a monopoly on mass dissemination of information. Anyone with an internet connection can now have their beliefs and opinions broadcast to anyone around the world who wants to listen. This removal of gatekeepers has allowed us to become not just information consumers, but also information producers.

11. People can find their ‘tribe’. With the rise of the internet, people can connect to people who share their interests from around the world. This has led to the rise of a multitude of internet subcultures where people get together on forums and associate with their ‘tribe’. Now, subculture groups (goths, LGBTQI youth, punks, etc.) who feel out of place among their friends from school can go online and connect with people who share their experiences.

12. National borders are less of a barrier. In the 20th Century, our ability to communicate was often restricted to people in our local community. This limited who we could associate with. The rise of dispersed tribes could have the effect of undermining traditional cultural groups (based around national identities, etc.) and instead allow us to link up with our dispersed sub-cultural groups around the world.

13. Minority views and opinions can gain traction. People from minority groups that were traditionally excluded from old mass media platforms have found platforms to share their opinions online. Together, they have been able to form groups large enough to have their voices heard. Silenced voices have risen up – from the #metoo movement to the Arab Spring – to change our world for the better.

14. We can stay in touch. Prior to social media platforms like Facebook, we often lost touch with people form out past. But now, thanks to social media, we can watch people from a distance and share our major achievements, milestones and life changes to stay in touch with people on our distant periphery.

15. News is instantaneous. Thanks to news apps, Twitter, etc., news spreads faster than ever. We no longer need to wait until the 6pm news to access our news. As part of this instantaneous access to knowledge, we now have what’s known as the “24 hour news cycle”. Consumers have an insatiable appetite for news, so new media have to pump out an ongoing stream of ever more sensationalized news articles.

16. News producers get instant feedback. As soon as a piece of news is pumped out, tweets fling back and comments are provided to show feedback. Digital analytics software identifies which headlines get the most clicks and can show how long people spend reading each article . These qualitative and quantitative big data coalesce to help news producers to create content that best serves their consumers.

Disadvantages of New Media

17. Misinformation spreads like wildfire. Without traditional gatekeepers of knowledge such as editors and publishing houses, there is nobody controlling which information is disseminated. Misinformation has become widespread in the 21st Century thanks to social media (Allcott, Gentzkow & Yu, 2019). This causes fringe conspiracy theories and even doctored images to influence people’s political and social views.

18. We can live in an ideological bubble. New media often allow us to ‘subscribe’ to our own news networks and favorite information producers. Without the need to have widespread mass appeal, new media target dispersed niche and ideological markets. Conservatives begin to only consume conservative media; and liberals only consume liberal media. People begin to only reinforce their personal views, causing social polarization.

19. There is fierce media competition. While in the past there were three or four major news organizations, now there are diverse and numerous sources for news. Small news websites with fresh takes for niche audiences popped up, crowding the market with information. In this crowded media market, there is competition in all niches, and brands need to have a fresh take to get attention.

20. There is a wider customer base for companies large and small. While competition is more fierce than ever, there is also a bigger customer base than ever before. Websites target global audiences and have global reach. A savvy media producer or social media marketer can expand their market globally – beyond what traditional media was generally capable of.

21. Children can access inappropriate information more easily. New media gives on-demand access to information. While in the past adult content was broadcast late at night, today it can be accessed day and night. Scholars like Neil Postman (1985) argue that there is a “disappearance of childhood” as a result of how media is changing. As children have greater access to adult information, the innocence of childhood is being decayed earlier than ever.

For your essay you might have to take a position on whether new media has been a ‘positive’ or a ‘negative’ force in society. In reality, there is no clear answer here: it’s been both positive and negative, in different ways. But we can clearly see that it has changed society significantly. It plays a huge role in political campaigns and changing how companies communicate with potential consumers. By outlining all the different facets of the advantages and disadvantages of new media, you can show the person grading your paper your deep and nuanced knowledge of the impact of new media on society.

Allcott, H., Gentzkow, M., & Yu, C. (2019). Trends in the diffusion of misinformation on social media. Research & Politics , 6 (2).

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism . New York: Verso books.

Carr, J. (2012). No laughing matter: the power of cyberspace to subvert conventional media gatekeepers. International journal of communication , 6 , 21.

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (2010). Manufacturing consent: The political economy of the mass media . New York: Random House.

Kellner, D., Dines, G., & Humez, J. M. (2011). Gender, race, and class in media: A critical reader. New York: Sage.

Logan, R. K. (2010). Understanding new media: extending Marshall McLuhan . New York: Peter Lang.

Postman, N., (1985). The disappearance of childhood. Childhood Education , 61 (4), pp.286-293.

Thompson, R. (2011). Radicalization and the use of social media. Journal of strategic security , 4 (4), 167-190.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Holistic Education: Definition, Benefits & Limitations

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Humanism in Education: Definition, Pros & Cons

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Behaviorism in Education: Definition, Pros and Cons

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 31 Major Learning Theories in Education, Explained!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

documents continued

top of page

Online Students

For All Online Programs

International Students

On Campus, need or have Visa

Campus Students

For All Campus Programs

What is New Media?

Know before you read At SNHU, we want to make sure you have the information you need to make decisions about your education and your future—no matter where you choose to go to school. That's why our informational articles may reference careers for which we do not offer academic programs, along with salary data for those careers. Cited projections do not guarantee actual salary or job growth.

This article was updated on Aug. 30, 2023 with additional contributions by Mars Girolimon.

New media doesn’t necessarily refer to a specific mode of communication. Some types, such as an online newspaper, are also “old media” in the form of a traditional printed newspaper. Others are entirely new, such as a podcast or smartphone app. It becomes even more complicated to define when you consider that as technology continues to advance, the definition continually changes.

New media is any media — from newspaper articles and blogs to music and podcasts — that are delivered digitally. From a website or email to mobile phones and streaming apps, any internet-related form of communication falls under its umbrella.

“I think a degree in new media is of value because it helps hone the skills necessary to succeed in this industry, like writing, graphic design, video production and marketing,” said Christine Bord , an adjunct instructor in Southern New Hampshire University’s (SNHU) liberal arts program . “This is also a very competitive field, and many employers are looking for candidates who have a degree in media and marketing.”

What Are Examples of New Media?

According to PCMag , new media refers to the "forms of communicating in the digital world, which is primarily online via the Internet." The term encompasses all content accessed through computers, smartphones and tablets.

That's in contrast to “ old media ,” which PCMag defines as all forms of communication that came before digital technology, including “radio and TV and printed materials such as books and magazines.”

It also constantly changes. As new technology is developed and widely adopted, what is considered "new" continues to morph. Once upon a time, DVDs and CDs were the latest way to watch movies and listen to music. Now, streaming services such as Netflix and Spotify are more popular.

Just a few examples of new media include:

- Mobile apps

- Social media networks

- Streaming services

- Virtual and augmented reality

“I think the most important thing to know about new media is that it is always changing,” Bord said. “Though this does make it a challenging field because professionals have to be aware of the constant changes in trends and technologies, it also makes it a very exciting and dynamic field to enter.”

Careers in New Media

But you don’t have to work in one of these roles to leverage skills you develop in a new media degree program. Robert Krueger is an adjunct in SNHU’s master's degree in communication . He said students often go on to work in communication roles at government agencies, hospitals and nonprofits.

“We also see a lot of journalists making the transition to communications, as well as high school teachers taking the next step by aspiring to become a professor at the college level,” Krueger said.

Thanks to developments of the internet age, you can earn an online degree at your own pace to launch a career working with digital content.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) tracks many positions that new media professionals work in, including:

Social Media Specialist

Social media specialists are experts at representing a company or brand in the public sphere through social media networks such as Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, Instagram and more. They create and post content and communicate with customers.

Working in social media requires an ongoing commitment to learning and professional development because the landscape is constantly changing. There are always new tools to discover or new platforms to explore, so it's important to keep upskilling and stay on top of the latest trends.

Social media specialists usually have a bachelor’s degree in social media marketing or a related program, and they have familiarity with social media platforms and best practices. If you already have a degree in a different field, you might opt for a graduate certificate in social media marketing to learn the skills you'll need to move into a role as a social media specialist.

Moving up the career ladder, you could also become a social media manager and oversee social media marketing campaigns.

According to BLS, specialists working in marketing roles made a median salary of $78,880 in 2021.*

Graphic Designer

Because graphic design is performed virtually, the career is inherently tied to new media. However, the digital images graphic designers create have applications throughout new and old media alike.

As a graphic designer, you would be charged with creating visual images using computer software to market products and services and to tell stories. You would work with images and text and decide how they work together to effectively communicate via a website, for example, according to BLS.

In 2021, graphic designers made a median salary of $50,710 , BLS reports.*

To become a graphic designer , you'll typically need a degree in graphic design or a related field, according to BLS.

While earning this degree, you'll delve into branding and web design and learn to use graphic design software like Photoshop. You'll also create a portfolio of work and prepare to land a job or find clients as a freelancer.

"Since graduating, I already accomplished a goal and dream with my degree," said Navarro. "I had the honor of being a part of a company's rebrand and designed the logo that is now on their storefront building."

She said everything she learned from her degree program came into play during this experience, and now the storefront is like a marker of her achievements.

"Any time that I drive past Small Town Couture, I am reminded that this opportunity, the logo design for their store, my capabilities, potential and success were gained from my degree at SNHU," Navarro said.

Marketing Manager

Marketing managers are executives who plan marketing and advertising campaigns based on market research and analysis and develop strategies to promote products and services to customers. As a marketing manager, you might also be charged with hiring promotions and marketing staff, meeting with clients and collaborating with other executives in a company — including public relations, sales and product development — to coordinate the role of marketing strategies within the larger company goals.

Marketing managers need a bachelor’s degree and usually have prior experience working in other marketing, promotions or advertising roles, according to BLS. Some employers emphasize the need for strong analytical, decision-making, organizational and communication skills and creativity.

Marketing managers made a median salary of $133,380 in 2021, and the position is expected to grow by 10% through 2031, according to BLS.*

The dawn of the internet age inspired so many developments in the field of marketing, and the field only keeps evolving along with technology and culture.

Through a digital marketing degree , you'll learn about all the different types of digital marketing , from search engine optimization (SEO), pay per click and social media marketing, to content marketing, email marketing and affiliate marketing. There are so many avenues to explore and roles associated with each specialization.

In addition to those positions, Krueger said the value of a new media degree can open up some industries that might not be obvious to you.

“Just as the saying goes about every business needs an accountant, I think that no business exists without a communications professional,” he said. “Most recently, I have come across many new media professionals who work in-house for large financial institutions and law firms.”

Bord agreed and said virtually every business needs to have a digital presence and should be interested in hiring media professionals.

“If you can think of an industry, chances are there is a new media position available within it,” she said.

Before Olivia Backus '23 started her bachelor's in marketing at SNHU, she was working in cosmetology and looking for a change.

"The schedule just did not work and I realized I liked the marketing process more than the job," said Backus.

With this realization, Backus decided to earn a degree that would help her transition to a new career in marketing — and that's exactly what she did.

"I graduated in January and I got a marketing coordinator job right out of school," she said.

From here, Backus hopes to move up into a position as a marketing director, but she's enjoying the benefits of her current role for now — including its salary.

"I can now financially provide for my family and that is something I have not been able to do before," Backus said.

Photographer

Photographers are a good example of a profession that has had to adapt from “old media” as technology evolved. Instead of film and a developing room, photographers today are armed with digital cameras and are adept at working with a wide range of computer software.

There also are several types of photography you can specialize in, such as:

- Aerial or drone photography

- Commercial photography

- Fine art photography

- News photography

- Portrait photography

As a photographer, you might work for a business or even start your own business and work for yourself.

Before you get started as a professional photographer, you'll need to learn how to compose a shot, work with lighting and use photo editing software like Photoshop and Lightroom.

While a college degree isn’t required, many aspiring photographers choose to attend post-high school training programs to develop their skills. Many entry-level photojournalist positions do require a photography degree , according to BLS, and business and marketing degrees can also be helpful for self-employed photographers.

In 2021, photographers made a median salary of $38,950 with a higher than average 9% job growth through 2031, according to BLS.*

Public Relations Specialist

Public relations (PR) specialists also help maintain and improve a company’s public reputation and image but generally do so by working with media members in person and via press releases and other measures. They can take a lead role in corporate communications, too, including speeches given by company leaders.

To work in PR, you'll likely need a public relations degree or an education in a related field, such as journalism, communications, English or business, according to BLS. You'll also rely heavily on interpersonal, organizational and communication skills .

If you're passionate about communicating with the public, PR might be your calling.

"I really love public relations," said Analiece Clark '23 . After earning her communication degree from SNHU, Clark said her workplace is helping her move to a public relations role. She's hoping to move up from there and also is interested in international relations.

Video Editor

The internet has opened so many doors to create, upload and share video content — with that in mind, the growing opportunities for video editors should come as no surprise.

BLS reports a much higher than average 12% growth rate for film and video editors and camera operators from 2021-2031, who earned a median annual salary of $60,360 in 2021 and typically hold bachelor's degree in a related field.*

Not only do video editors work on the shows and movies you watch on streaming services like Disney+ or Netflix, many work with content creators and influencers on YouTube videos and TikTok reels, too. There are also roles for video editors to work with these platforms and others in the digital marketing world.

According to BLS , video editors typically hold a bachelor's degree in communication or a related field.

While there are still some opportunities to work in print media, many writers today find work in the digital sphere.

In addition to writing online articles, blogs and newsletters, there are growing opportunities in scriptwriting thanks to the internet. That not only includes screenwriting for TV and movies on streaming services but writing for video advertisements, podcasts, YouTube videos and other types of audio or video content.

If you have a mind for marketing, you could also become a copywriter and work on advertisements, product descriptions, integrated campaigns and other marketing materials.

According to BLS, writers and authors, including scriptwriters and copywriters, made a median salary of $69,510 in 2021 with average growth in the profession projected through 2031.*

After earning her MFA in Creative Writing at SNHU, Emily Jones '20MFA said she overcame her impostor syndrome and developed the expertise needed to move forward in her career.

"I now know exactly how to apply for a teaching job. I know exactly how to pursue freelance clients and budget and market myself," Jones said.

Writers often work from home and many with advanced writing degrees like Jones also teach online writing courses.

New Media Skills

By studying and working in new media, professionals in the field can develop strong and marketable skills that are valuable across a vast range of industries. From writing, editing and design to marketing and public relations, these skills can help you market yourself to too many types of employers to list.

“While studying new media, students will learn theoretical and tactical skills in social media, video, digital marketing, public relations and other areas of communication,” Krueger said. “We look to prepare students to be leaders in their field, which is why we focus on how to strategize and offer consultation to CEOs and C-suite members when given a seat at the table.”

As a professional in this field, you can bring value to a company or organization by applying your technical and soft skills to adapt to an ever-changing digital landscape.

“Students in this area bring know-how in the art of messaging and that intersection with technology,” Krueger said. “As a professor who also works for a large global company, I assure you these are the skills that make communicators succeed out in the field.”

Discover more about SNHU’s online communication degree : Find out what courses you'll take, skills you’ll learn and how to request information about the program.

*Cited job growth projections may not reflect local and/or short-term economic or job conditions and do not guarantee actual job growth. Actual salaries and/or earning potential may be the result of a combination of factors including, but not limited to: years of experience, industry of employment, geographic location, and worker skill.

Joe Cote is a staff writer at Southern New Hampshire University. Follow him on X, formerly known as Twitter @JoeCo2323 .

Mars Girolimon '21 '23G is a writer with a master's in English and creative writing from Southern New Hampshire University. Connect with them on LinkedIn and X, formerly known as Twitter .

Explore more content like this article

Is a History Degree Worth It?

Why is History Important?

Why is Poetry Important? Celebrating National Poetry Month

About southern new hampshire university.

SNHU is a nonprofit, accredited university with a mission to make high-quality education more accessible and affordable for everyone.

Founded in 1932, and online since 1995, we’ve helped countless students reach their goals with flexible, career-focused programs . Our 300-acre campus in Manchester, NH is home to over 3,000 students, and we serve over 135,000 students online. Visit our about SNHU page to learn more about our mission, accreditations, leadership team, national recognitions and awards.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.3 The Evolution of Media

Learning objectives.

- Identify four roles the media performs in our society.

- Recognize events that affected the adoption of mass media.

- Explain how different technological transitions have shaped media industries.

In 2010, Americans could turn on their television and find 24-hour news channels as well as music videos, nature documentaries, and reality shows about everything from hoarders to fashion models. That’s not to mention movies available on demand from cable providers or television and video available online for streaming or downloading. Half of U.S. households receive a daily newspaper, and the average person holds 1.9 magazine subscriptions (State of the Media, 2004) (Bilton, 2007). A University of California, San Diego study claimed that U.S. households consumed a total of approximately 3.6 zettabytes of information in 2008—the digital equivalent of a 7-foot high stack of books covering the entire United States—a 350 percent increase since 1980 (Ramsey, 2009). Americans are exposed to media in taxicabs and buses, in classrooms and doctors’ offices, on highways, and in airplanes. We can begin to orient ourselves in the information cloud through parsing what roles the media fills in society, examining its history in society, and looking at the way technological innovations have helped bring us to where we are today.

What Does Media Do for Us?

Media fulfills several basic roles in our society. One obvious role is entertainment. Media can act as a springboard for our imaginations, a source of fantasy, and an outlet for escapism. In the 19th century, Victorian readers disillusioned by the grimness of the Industrial Revolution found themselves drawn into fantastic worlds of fairies and other fictitious beings. In the first decade of the 21st century, American television viewers could peek in on a conflicted Texas high school football team in Friday Night Lights ; the violence-plagued drug trade in Baltimore in The Wire ; a 1960s-Manhattan ad agency in Mad Men ; or the last surviving band of humans in a distant, miserable future in Battlestar Galactica . Through bringing us stories of all kinds, media has the power to take us away from ourselves.

Media can also provide information and education. Information can come in many forms, and it may sometimes be difficult to separate from entertainment. Today, newspapers and news-oriented television and radio programs make available stories from across the globe, allowing readers or viewers in London to access voices and videos from Baghdad, Tokyo, or Buenos Aires. Books and magazines provide a more in-depth look at a wide range of subjects. The free online encyclopedia Wikipedia has articles on topics from presidential nicknames to child prodigies to tongue twisters in various languages. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has posted free lecture notes, exams, and audio and video recordings of classes on its OpenCourseWare website, allowing anyone with an Internet connection access to world-class professors.

Another useful aspect of media is its ability to act as a public forum for the discussion of important issues. In newspapers or other periodicals, letters to the editor allow readers to respond to journalists or to voice their opinions on the issues of the day. These letters were an important part of U.S. newspapers even when the nation was a British colony, and they have served as a means of public discourse ever since. The Internet is a fundamentally democratic medium that allows everyone who can get online the ability to express their opinions through, for example, blogging or podcasting—though whether anyone will hear is another question.

Similarly, media can be used to monitor government, business, and other institutions. Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle exposed the miserable conditions in the turn-of-the-century meatpacking industry; and in the early 1970s, Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered evidence of the Watergate break-in and subsequent cover-up, which eventually led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon. But purveyors of mass media may be beholden to particular agendas because of political slant, advertising funds, or ideological bias, thus constraining their ability to act as a watchdog. The following are some of these agendas:

- Entertaining and providing an outlet for the imagination

- Educating and informing

- Serving as a public forum for the discussion of important issues

- Acting as a watchdog for government, business, and other institutions

It’s important to remember, though, that not all media are created equal. While some forms of mass communication are better suited to entertainment, others make more sense as a venue for spreading information. In terms of print media, books are durable and able to contain lots of information, but are relatively slow and expensive to produce; in contrast, newspapers are comparatively cheaper and quicker to create, making them a better medium for the quick turnover of daily news. Television provides vastly more visual information than radio and is more dynamic than a static printed page; it can also be used to broadcast live events to a nationwide audience, as in the annual State of the Union address given by the U.S. president. However, it is also a one-way medium—that is, it allows for very little direct person-to-person communication. In contrast, the Internet encourages public discussion of issues and allows nearly everyone who wants a voice to have one. However, the Internet is also largely unmoderated. Users may have to wade through thousands of inane comments or misinformed amateur opinions to find quality information.

The 1960s media theorist Marshall McLuhan took these ideas one step further, famously coining the phrase “ the medium is the message (McLuhan, 1964).” By this, McLuhan meant that every medium delivers information in a different way and that content is fundamentally shaped by the medium of transmission. For example, although television news has the advantage of offering video and live coverage, making a story come alive more vividly, it is also a faster-paced medium. That means more stories get covered in less depth. A story told on television will probably be flashier, less in-depth, and with less context than the same story covered in a monthly magazine; therefore, people who get the majority of their news from television may have a particular view of the world shaped not by the content of what they watch but its medium . Or, as computer scientist Alan Kay put it, “Each medium has a special way of representing ideas that emphasize particular ways of thinking and de-emphasize others (Kay, 1994).” Kay was writing in 1994, when the Internet was just transitioning from an academic research network to an open public system. A decade and a half later, with the Internet firmly ensconced in our daily lives, McLuhan’s intellectual descendants are the media analysts who claim that the Internet is making us better at associative thinking, or more democratic, or shallower. But McLuhan’s claims don’t leave much space for individual autonomy or resistance. In an essay about television’s effects on contemporary fiction, writer David Foster Wallace scoffed at the “reactionaries who regard TV as some malignancy visited on an innocent populace, sapping IQs and compromising SAT scores while we all sit there on ever fatter bottoms with little mesmerized spirals revolving in our eyes…. Treating television as evil is just as reductive and silly as treating it like a toaster with pictures (Wallace, 1997).” Nonetheless, media messages and technologies affect us in countless ways, some of which probably won’t be sorted out until long in the future.

A Brief History of Mass Media and Culture

Until Johannes Gutenberg’s 15th-century invention of the movable type printing press, books were painstakingly handwritten and no two copies were exactly the same. The printing press made the mass production of print media possible. Not only was it much cheaper to produce written material, but new transportation technologies also made it easier for texts to reach a wide audience. It’s hard to overstate the importance of Gutenberg’s invention, which helped usher in massive cultural movements like the European Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. In 1810, another German printer, Friedrich Koenig, pushed media production even further when he essentially hooked the steam engine up to a printing press, enabling the industrialization of printed media. In 1800, a hand-operated printing press could produce about 480 pages per hour; Koenig’s machine more than doubled this rate. (By the 1930s, many printing presses could publish 3,000 pages an hour.)

This increased efficiency went hand in hand with the rise of the daily newspaper. The newspaper was the perfect medium for the increasingly urbanized Americans of the 19th century, who could no longer get their local news merely through gossip and word of mouth. These Americans were living in unfamiliar territory, and newspapers and other media helped them negotiate the rapidly changing world. The Industrial Revolution meant that some people had more leisure time and more money, and media helped them figure out how to spend both. Media theorist Benedict Anderson has argued that newspapers also helped forge a sense of national identity by treating readers across the country as part of one unified community (Anderson, 1991).

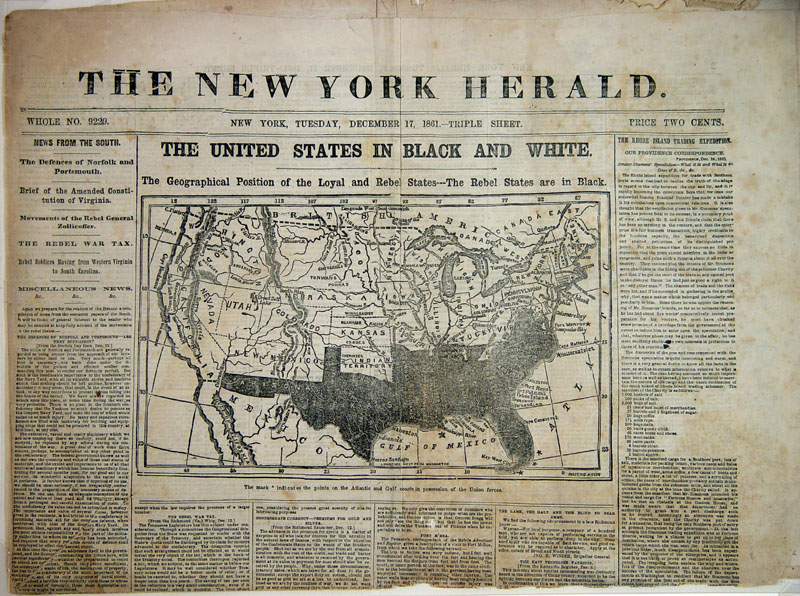

In the 1830s, the major daily newspapers faced a new threat from the rise of penny papers, which were low-priced broadsheets that served as a cheaper, more sensational daily news source. They favored news of murder and adventure over the dry political news of the day. While newspapers catered to a wealthier, more educated audience, the penny press attempted to reach a wide swath of readers through cheap prices and entertaining (often scandalous) stories. The penny press can be seen as the forerunner to today’s gossip-hungry tabloids.

The penny press appealed to readers’ desires for lurid tales of murder and scandal.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

In the early decades of the 20th century, the first major nonprint form of mass media—radio—exploded in popularity. Radios, which were less expensive than telephones and widely available by the 1920s, had the unprecedented ability of allowing huge numbers of people to listen to the same event at the same time. In 1924, Calvin Coolidge’s preelection speech reached more than 20 million people. Radio was a boon for advertisers, who now had access to a large and captive audience. An early advertising consultant claimed that the early days of radio were “a glorious opportunity for the advertising man to spread his sales propaganda” because of “a countless audience, sympathetic, pleasure seeking, enthusiastic, curious, interested, approachable in the privacy of their homes (Briggs & Burke, 2005).” The reach of radio also meant that the medium was able to downplay regional differences and encourage a unified sense of the American lifestyle—a lifestyle that was increasingly driven and defined by consumer purchases. “Americans in the 1920s were the first to wear ready-made, exact-size clothing…to play electric phonographs, to use electric vacuum cleaners, to listen to commercial radio broadcasts, and to drink fresh orange juice year round (Mintz, 2007).” This boom in consumerism put its stamp on the 1920s and also helped contribute to the Great Depression of the 1930s (Library of Congress). The consumerist impulse drove production to unprecedented levels, but when the Depression began and consumer demand dropped dramatically, the surplus of production helped further deepen the economic crisis, as more goods were being produced than could be sold.

The post–World War II era in the United States was marked by prosperity, and by the introduction of a seductive new form of mass communication: television. In 1946, about 17,000 televisions existed in the United States; within 7 years, two-thirds of American households owned at least one set. As the United States’ gross national product (GNP) doubled in the 1950s, and again in the 1960s, the American home became firmly ensconced as a consumer unit; along with a television, the typical U.S. household owned a car and a house in the suburbs, all of which contributed to the nation’s thriving consumer-based economy (Briggs & Burke, 2005). Broadcast television was the dominant form of mass media, and the three major networks controlled more than 90 percent of the news programs, live events, and sitcoms viewed by Americans. Some social critics argued that television was fostering a homogenous, conformist culture by reinforcing ideas about what “normal” American life looked like. But television also contributed to the counterculture of the 1960s. The Vietnam War was the nation’s first televised military conflict, and nightly images of war footage and war protesters helped intensify the nation’s internal conflicts.

Broadcast technology, including radio and television, had such a hold on the American imagination that newspapers and other print media found themselves having to adapt to the new media landscape. Print media was more durable and easily archived, and it allowed users more flexibility in terms of time—once a person had purchased a magazine, he or she could read it whenever and wherever. Broadcast media, in contrast, usually aired programs on a fixed schedule, which allowed it to both provide a sense of immediacy and fleetingness. Until the advent of digital video recorders in the late 1990s, it was impossible to pause and rewind a live television broadcast.

The media world faced drastic changes once again in the 1980s and 1990s with the spread of cable television. During the early decades of television, viewers had a limited number of channels to choose from—one reason for the charges of homogeneity. In 1975, the three major networks accounted for 93 percent of all television viewing. By 2004, however, this share had dropped to 28.4 percent of total viewing, thanks to the spread of cable television. Cable providers allowed viewers a wide menu of choices, including channels specifically tailored to people who wanted to watch only golf, classic films, sermons, or videos of sharks. Still, until the mid-1990s, television was dominated by the three large networks. The Telecommunications Act of 1996, an attempt to foster competition by deregulating the industry, actually resulted in many mergers and buyouts that left most of the control of the broadcast spectrum in the hands of a few large corporations. In 2003, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) loosened regulation even further, allowing a single company to own 45 percent of a single market (up from 25 percent in 1982).

Technological Transitions Shape Media Industries

New media technologies both spring from and cause social changes. For this reason, it can be difficult to neatly sort the evolution of media into clear causes and effects. Did radio fuel the consumerist boom of the 1920s, or did the radio become wildly popular because it appealed to a society that was already exploring consumerist tendencies? Probably a little bit of both. Technological innovations such as the steam engine, electricity, wireless communication, and the Internet have all had lasting and significant effects on American culture. As media historians Asa Briggs and Peter Burke note, every crucial invention came with “a change in historical perspectives.” Electricity altered the way people thought about time because work and play were no longer dependent on the daily rhythms of sunrise and sunset; wireless communication collapsed distance; the Internet revolutionized the way we store and retrieve information.

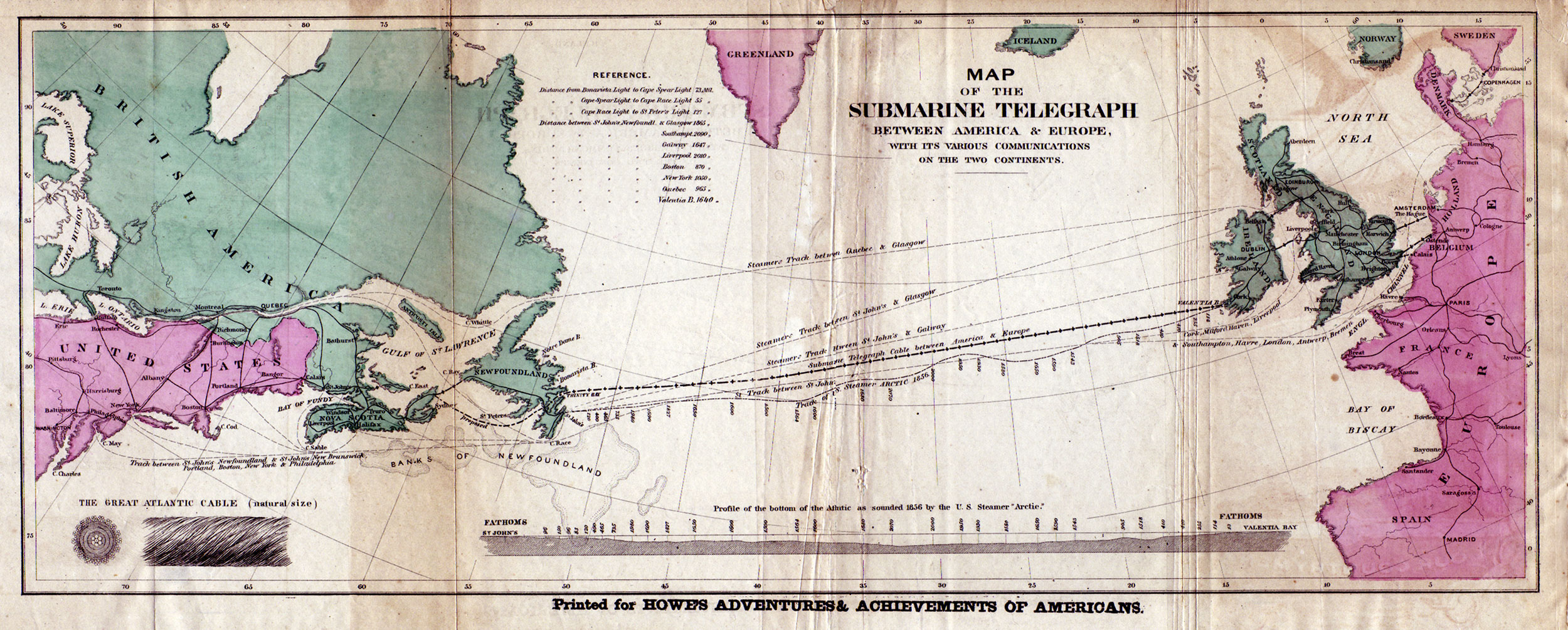

The transatlantic telegraph cable made nearly instantaneous communication between the United States and Europe possible for the first time in 1858.

Amber Case – 1858 trans-Atlantic telegraph cable route – CC BY-NC 2.0.

The contemporary media age can trace its origins back to the electrical telegraph, patented in the United States by Samuel Morse in 1837. Thanks to the telegraph, communication was no longer linked to the physical transportation of messages; it didn’t matter whether a message needed to travel 5 or 500 miles. Suddenly, information from distant places was nearly as accessible as local news, as telegraph lines began to stretch across the globe, making their own kind of World Wide Web. In this way, the telegraph acted as the precursor to much of the technology that followed, including the telephone, radio, television, and Internet. When the first transatlantic cable was laid in 1858, allowing nearly instantaneous communication from the United States to Europe, the London Times described it as “the greatest discovery since that of Columbus, a vast enlargement…given to the sphere of human activity.”

Not long afterward, wireless communication (which eventually led to the development of radio, television, and other broadcast media) emerged as an extension of telegraph technology. Although many 19th-century inventors, including Nikola Tesla, were involved in early wireless experiments, it was Italian-born Guglielmo Marconi who is recognized as the developer of the first practical wireless radio system. Many people were fascinated by this new invention. Early radio was used for military communication, but soon the technology entered the home. The burgeoning interest in radio inspired hundreds of applications for broadcasting licenses from newspapers and other news outlets, retail stores, schools, and even cities. In the 1920s, large media networks—including the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS)—were launched, and they soon began to dominate the airwaves. In 1926, they owned 6.4 percent of U.S. broadcasting stations; by 1931, that number had risen to 30 percent.

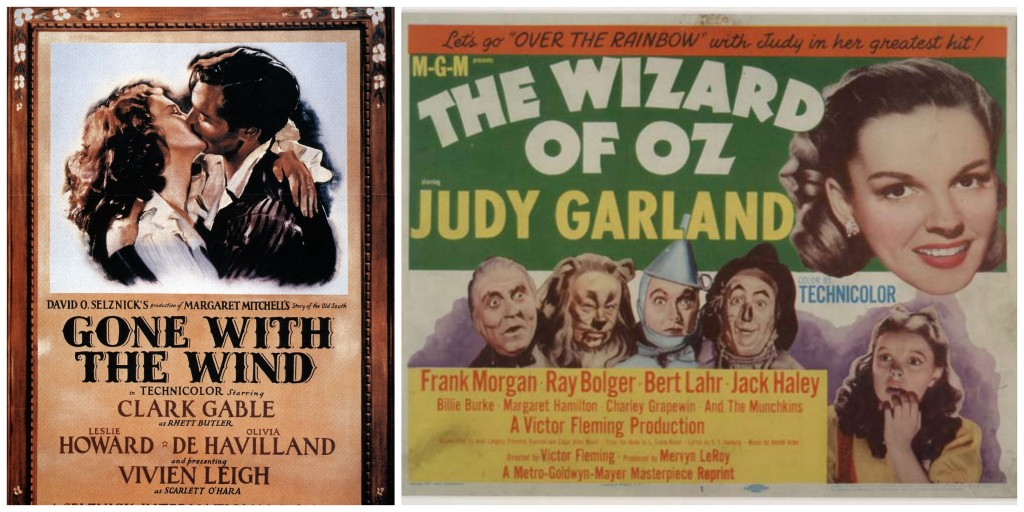

Gone With the Wind defeated The Wizard of Oz to become the first color film ever to win the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1939.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain; Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

In addition to the breakthroughs in audio broadcasting, inventors in the 1800s made significant advances in visual media. The 19th-century development of photographic technologies would lead to the later innovations of cinema and television. As with wireless technology, several inventors independently created a form of photography at the same time, among them the French inventors Joseph Niépce and Louis Daguerre and the British scientist William Henry Fox Talbot. In the United States, George Eastman developed the Kodak camera in 1888, anticipating that Americans would welcome an inexpensive, easy-to-use camera into their homes as they had with the radio and telephone. Moving pictures were first seen around the turn of the century, with the first U.S. projection-hall opening in Pittsburgh in 1905. By the 1920s, Hollywood had already created its first stars, most notably Charlie Chaplin; by the end of the 1930s, Americans were watching color films with full sound, including Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz .

Television—which consists of an image being converted to electrical impulses, transmitted through wires or radio waves, and then reconverted into images—existed before World War II, but gained mainstream popularity in the 1950s. In 1947, there were 178,000 television sets made in the United States; 5 years later, 15 million were made. Radio, cinema, and live theater declined because the new medium allowed viewers to be entertained with sound and moving pictures in their homes. In the United States, competing commercial stations (including the radio powerhouses of CBS and NBC) meant that commercial-driven programming dominated. In Great Britain, the government managed broadcasting through the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). Funding was driven by licensing fees instead of advertisements. In contrast to the U.S. system, the BBC strictly regulated the length and character of commercials that could be aired. However, U.S. television (and its increasingly powerful networks) still dominated. By the beginning of 1955, there were around 36 million television sets in the United States, but only 4.8 million in all of Europe. Important national events, broadcast live for the first time, were an impetus for consumers to buy sets so they could witness the spectacle; both England and Japan saw a boom in sales before important royal weddings in the 1950s.

In the 1960s, the concept of a useful portable computer was still a dream; huge mainframes were required to run a basic operating system.

In 1969, management consultant Peter Drucker predicted that the next major technological innovation would be an electronic appliance that would revolutionize the way people lived just as thoroughly as Thomas Edison’s light bulb had. This appliance would sell for less than a television set and be “capable of being plugged in wherever there is electricity and giving immediate access to all the information needed for school work from first grade through college.” Although Drucker may have underestimated the cost of this hypothetical machine, he was prescient about the effect these machines—personal computers—and the Internet would have on education, social relationships, and the culture at large. The inventions of random access memory (RAM) chips and microprocessors in the 1970s were important steps to the Internet age. As Briggs and Burke note, these advances meant that “hundreds of thousands of components could be carried on a microprocessor.” The reduction of many different kinds of content to digitally stored information meant that “print, film, recording, radio and television and all forms of telecommunications [were] now being thought of increasingly as part of one complex.” This process, also known as convergence, is a force that’s affecting media today.

Key Takeaways

Media fulfills several roles in society, including the following:

- entertaining and providing an outlet for the imagination,

- educating and informing,

- serving as a public forum for the discussion of important issues, and

- acting as a watchdog for government, business, and other institutions.

- Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press enabled the mass production of media, which was then industrialized by Friedrich Koenig in the early 1800s. These innovations led to the daily newspaper, which united the urbanized, industrialized populations of the 19th century.

- In the 20th century, radio allowed advertisers to reach a mass audience and helped spur the consumerism of the 1920s—and the Great Depression of the 1930s. After World War II, television boomed in the United States and abroad, though its concentration in the hands of three major networks led to accusations of homogenization. The spread of cable and subsequent deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s led to more channels, but not necessarily to more diverse ownership.

- Transitions from one technology to another have greatly affected the media industry, although it is difficult to say whether technology caused a cultural shift or resulted from it. The ability to make technology small and affordable enough to fit into the home is an important aspect of the popularization of new technologies.

Choose two different types of mass communication—radio shows, television broadcasts, Internet sites, newspaper advertisements, and so on—from two different kinds of media. Make a list of what role(s) each one fills, keeping in mind that much of what we see, hear, or read in the mass media has more than one aspect. Then, answer the following questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- To which of the four roles media plays in society do your selections correspond? Why did the creators of these particular messages present them in these particular ways and in these particular mediums?

- What events have shaped the adoption of the two kinds of media you selected?

- How have technological transitions shaped the industries involved in the two kinds of media you have selected?

Anderson, Benedict Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism , (London: Verso, 1991).

Bilton, Jim. “The Loyalty Challenge: How Magazine Subscriptions Work,” In Circulation , January/February 2007.

Briggs and Burke, Social History of the Media .

Briggs, Asa and Peter Burke, A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2005).

Kay, Alan. “The Infobahn Is Not the Answer,” Wired , May 1994.

Library of Congress, “Radio: A Consumer Product and a Producer of Consumption,” Coolidge-Consumerism Collection, http://lcweb2.loc.gov:8081/ammem/amrlhtml/inradio.html .

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man , (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964).

Mintz, Steven “The Jazz Age: The American 1920s: The Formation of Modern American Mass Culture,” Digital History , 2007, http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?hhid=454 .

Ramsey, Doug. “UC San Diego Experts Calculate How Much Information Americans Consume” UC San Diego News Center, December 9, 2009, http://ucsdnews.ucsd.edu/newsrel/general/12-09Information.asp .

State of the Media, project for Excellence in Journalism, The State of the News Media 2004 , http://www.stateofthemedia.org/2004/ .

Wallace, David Foster “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction,” in A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again (New York: Little Brown, 1997).

Understanding Media and Culture Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 21 February 2018

Media use and brain development during adolescence

- Eveline A. Crone 1 &

- Elly A. Konijn 2

Nature Communications volume 9 , Article number: 588 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

188k Accesses

190 Citations

256 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cognitive neuroscience

The current generation of adolescents grows up in a media-saturated world. However, it is unclear how media influences the maturational trajectories of brain regions involved in social interactions. Here we review the neural development in adolescence and show how neuroscience can provide a deeper understanding of developmental sensitivities related to adolescents’ media use. We argue that adolescents are highly sensitive to acceptance and rejection through social media, and that their heightened emotional sensitivity and protracted development of reflective processing and cognitive control may make them specifically reactive to emotion-arousing media. This review illustrates how neuroscience may help understand the mutual influence of media and peers on adolescents’ well-being and opinion formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mechanisms linking social media use to adolescent mental health vulnerability

Diverse adolescents’ transcendent thinking predicts young adult psychosocial outcomes via brain network development

Windows of developmental sensitivity to social media

Introduction.

Media play a tremendously important role in the lives of today’s youth, who grow up with tablets and smartphones, and do not remember a time before the internet, and are hence called ‘digital natives’ 1 , 2 . The current generation of the adolescents lives in a media-saturated world, where media is used not only for entertainment purposes, such as listening to music or watching movies, but is also used increasingly for communicating with peers via WhatsApp, Instagram, SnapChat, Facebook, etc. Taken together, these media-related activities comprise roughly 6–9 h of an American youth’s day, excluding home- and schoolwork ( https://www.commonsensemedia.org/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens-infographic ) 3 , 4 . Social media enable people to share information, ideas or opinions, messages, images and videos. Today, all kinds of media formats are constantly available through portable mobile devices such as smartphones and have become an integrated part of adolescents’ social life 5 .

Adolescence, which is defined as the transition period between childhood and adulthood (approximately ages 10–22 years, although age bins differ between cultures), is a developmental stage in which parental influence decreases and peers become more important 6 . Being accepted or rejected by peers is highly salient in adolescence, also there is a strong need to fit into the peer group and they are highly influenced by their peers 7 . Therefore, it is imperative that we understand how adolescents process media content and peers’ feedback provided on such platforms. Adolescents’ social lives in particular seem to occur for a large part through smartphones that are filled with friends with whom they are constantly connected (cf. “A day not wired is a day not lived” 5 , 8 ). This is where they monitor their peer status, check peers’ feedback, rejection and acceptance messages, and encounter peers as (idealized) images 9 on screens 5 , 8 , 10 . Likely, this plays an important role in adolescent development, and we therefore focus primarily on adolescents’ social media use 11 . Most media research to date is based on correlational and self-report data, and would be strengthened by integrating experimental paradigms and more objectively assessed behavioral, emotional, and neural consequences of experimentally induced media use.

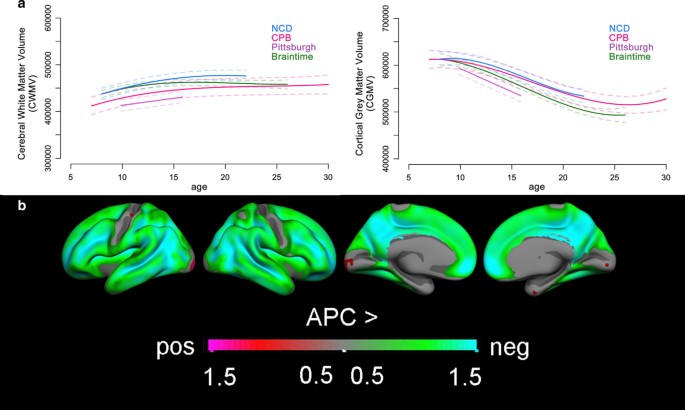

Recently, cognitive neuroscience studies have used structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine how the adolescent brain changes over the course of the adolescent years 6 . The results of several studies demonstrate that cognitive and socio-affective development in adolescence is accompanied by extensive changes in the structure and function of the adolescent brain 6 . Structurally, white matter connections increase, allowing for more successful communication between different areas of the brain 12 . The maturation of these connections is related to behavioral control, for example, connections between the prefrontal cortex and the subcortical striatum mediate age-related improvements in the ability to wait for a reward 13 . In addition to these changes in white matter connections, neurons in the brain grow in number between conception and childhood, with greatest synaptic density in early childhood. This increase in synaptic density co-occurs with synaptic pruning, and pruning rates increase in adolescence, resulting in a decrease in synaptic density in late childhood and adolescence 14 . Structural MRI research revealed that the peak in grey matter volume probably occurs before the age of 10 years, but dynamic non-linear changes in grey matter volume continue over the whole period of adolescence, and the timing is region-specific 15 . Interestingly, changes in grey matter volume are observed most extensively in brain regions that are important for social understanding and communication such as the medial prefrontal cortex, superior temporal cortex and temporal parietal junction 16 . Figure 1 displays the extensive changes in the human cortex during adolescence.

Longitudinal changes in brain structure across adolescence (ages 8–30). a Consistent patterns of change across four independent longitudinal samples (391 participants, 852 scans), with increases in cerebral white matter volume and decreases in cortical grey matter volume (adapted from Mills et al., 2016, NeuroImage 105 ). b Of the two main components of cortical volume, surface area and thickness, thinning across ages 8 to 25 years is the main contributor to volume reduction across adolescence, here displayed in the Braintime sample (209 participants, 418 scans). Displayed are regional differences in annual percentage change (APC) across the whole brain, the more the color changes in the direction of green to blue, the larger the annual decrease in volume (adapted from Tamnes et al., 2017, J Neuroscience 15 )

Given that brain regions involved in many social aspects of life are undergoing such extensive changes during adolescence, it is likely that social influences—which also occur through the use of social media as the internet connects adolescents to many people at once—are particularly potent at this age in coalescence with their media use. Also, subcortical brain regions undergo pronounced changes during adolescence 17 . There is evidence that the density of grey matter volume in the amygdala, a structure associated with emotional processing, is related to larger offline social networks 18 , as well as larger online social networks 19 , 20 . This suggests an important interplay between actual social experiences, both offline and online, and brain development.

This review brings together research on media use among adolescents with neural development during adolescence. We will specifically focus on the following three aspects of media exposure of interest to adolescent development 21 : (1) social acceptance or rejection, (2) peer influence on self-image and self-perception, and (3) the role of emotions in media use. Finally, we discuss new perspectives on how the interplay between media exposure and sensitive periods in brain development may make some individuals more susceptible to the consequences of media use than others.

Being accepted or rejected online

Experiencing acceptance or rejection when communicating via digital media is an impactful social experience. Extensive research, including large meta-analyses, has demonstrated that social rejection in a computerized environment can be experienced similarly as face-to-face rejection and bullying, although the prevalence of cyberbullying is generally lower 22 , 23 (and studies vary widely: prevalence rates depend on how cyberbullying is defined and measured). In all, cyberbullying peaks during adolescence 24 and large overlap has been found between victims and bullies. In part, this overlap could be explained by victimized adolescents seeking exposure to antisocial and risk behavior media content 25 . The next subsections will describe recent discoveries in neuroscience on the neural responses to online rejection and acceptance.

Neural responses to online social rejection

The emotional and neural effects of being socially excluded have been well captured by research involving the Cyberball Paradigm 26 ( https://cyberball.wikispaces.com/ ). Cyberball is a virtual ball-toss game in which the study participant tosses a ball with two simulated players (so-called confederates) via a screen. After a round of fair play, the confederates, who only throw the ball to each other, exclude the participant in the rejection condition. This results in pronounced negative effects on the participants’ feeling to belong, ostracism, sense of control, and self-esteem 26 . Even though the paradigm was not designed to study online rejection as it occurs today on social media, the findings of prior Cyberball studies may provide an important starting point for understanding the processes involved in online rejection. In fact, inspired by Cyberball, a Social Media Ostracism paradigm has recently been developed by applying a Facebook format to study the effects of online social exclusion 27 .

Using functional MRI (fMRI), researchers have observed increased activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and insula after participants experienced exclusion, possibly signaling increased arousal and negative affect 28 . In addition, stronger activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is observed in adolescents and young adults with a history of being socially excluded 29 , maltreated 30 , or insecure attachment, whereas spending more time with friends reduced ACC response in adolescents to social exclusion 31 . This may possibly protect adolescents against the negative influence of ostracism or cyberbullying, although all these studies are correlational. Therefore, it remains to be determined whether environment influences brain development or vice versa. Moreover, ACC and insula activity have also been explained as signaling a highly significant event because the same regions are also active when participants experience inclusion 32 . Furthermore, studies with adolescents observed specific activity in the ventral striatum 33 , and in the subgenual ACC when adolescents were excluded in the online Cyberball computer game 34 , 35 , the latter region is often implicated in depression 36 . Thus, being rejected was associated with activity in brain regions that are also activated when experiencing salient emotions 37 , 38 . These studies may indicate a specific window of sensitivity to social rejection in adolescence, which may be associated with the enhanced activity of striatum and subgenual ACC in adolescence 33 , 36 .

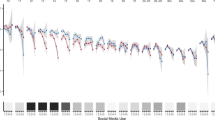

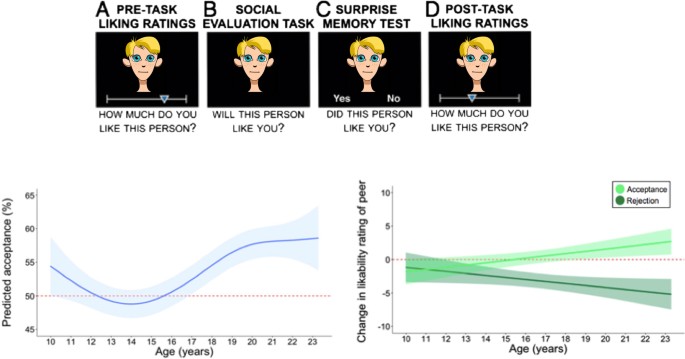

Social rejection has also been studied using task paradigms that mirror online communication more specifically. In the social judgment paradigm, participants enter a chat room, where others can judge their profile pictures based on first impression 39 . This can result in being rejected or accepted by others in a way that is directly comparable to social media environments where individuals connect based on first impression (for example,’liking’ on Instagram). A developmental behavioral study (participants between 10 and 23 years) showed that young adults expected to be accepted more than adolescents. Moreover, these adults, relative to adolescents, adjusted their evaluations of others more based on whether others accepted or rejected them, possibly indicating self-protecting biases 40 (Fig. 2 ). Neuroimaging studies revealed that, being rejected based only on one’s profile pictures resulted in increased activity in the medial frontal cortex, in both adults 41 and children 42 , and studies in adolescents showed enhanced pupil dilation, a response to greater cognitive load and emotional intensity, to rejection 43 .

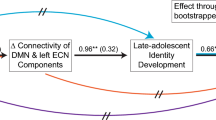

Adolescents’ expectations and adjustments of being liked and liking others. Social evaluation study in which participants between ages 10 and 23 years rated other peers on whether they liked the other person, whether they believed the other would like them, and a post scan rating of liking the other person after having received acceptance or rejection feedback from the other person. The faces used in this adaptation of figure are cartoon approximations of the original stimuli used in ref. 40 ; to see the original stimuli, please refer to ref. 40 . The left graph shows that adolescents expect least to be liked by the other before receiving feedback (question B). The right graph shows a developmental increase in distinguishing between liking and disliking based on feedback from the other person (question D). (Adapted with permission from Rodman, 2017, PNAS 40 )

Taken together, these studies suggest that adolescents show stronger rejection expectation than adults, and subgenual ACC and medial frontal cortex are critically involved when processing online exclusion or rejection. In the next section, we describe how the brain of adolescents and adults respond to receiving positive feedback and likes from others.

Neural responses to online social acceptance

The positive feeling of social acceptance online is endorsed through the receipt of likes, one’s cool ratio (i.e., followers > following; Business Insider, 11 June 2014: http://www.businessinsider.com/instagram-cool-ratio-2014–6?international=true&r=US&IR=T .) or popularity, positive comments and hashtags, among other forms of reward 44 , 45 . Neuropsychological research showed that being accepted evokes activation in similar brain regions, as when receiving other rewards such as money or pleasant tastes 38 . Most pronounced activity was found in the ventral striatum, together with the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and ventral tegmental area, which is consistently reported as a key region in the brain for the subjective experience of pleasure and reward 46 , including social rewards 47 . Likewise, being socially accepted through likes in the chat room task resulted in increased activity in the ventral striatum in children 42 , adolescents 48 , 49 and adults 41 , 50 . This response is blunted in adolescents who experience depression 36 , or who have experienced a history of maternal negative affect 51 . Apparently, prior social experiences—such as parental relations—are an important factor for understanding which adolescents are more sensitive to the impact of social media 51 . In this regard, media research showed that popularity moderates depression 10 and that attachment styles and loneliness increases the likelihood to seek socio-affective bonding with media figures 52 .

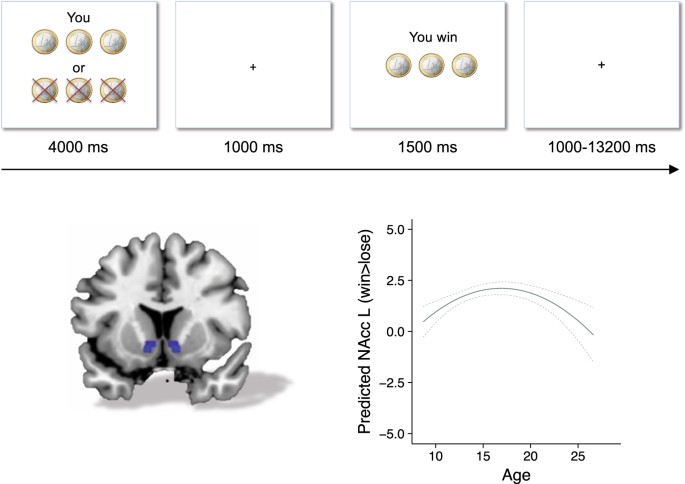

Interestingly, several studies and meta-analyses using gambling and reward paradigms have reported that activity in the ventral striatum to monetary rewards peaks in mid-adolescence 53 , 54 , 55 (Fig. 3 ; see Box 1 for views on adolescent risk taking in various contexts). These findings may suggest general reward sensitivity in adolescence such that reward centers that respond to monetary reward may also show increased sensitivity to social reward in adolescence. Social reward sensitivity may be a strong reinforcer in social media use. A prior study in adults showed that activity in the ventral striatum in response to an increase in one’s reputation, but not wealth, predicted frequency of Facebook use 56 . In a similar vein, adolescents showed sensitivity to “likes” of peers on social media 44 , 57 . In a controlled experimental study, adolescents showed more activity in the ventral striatum when viewing images with many vs. few likes, and this activation was stronger for older adolescents and college students compared to younger adolescents 57 . Thus, the same region that is active when being liked on the basis of first impression of a profile picture 48 , is also activated when viewing images that are liked by others, especially in mid-to-late adolescence, possibly extending into adulthood 57 (see also ref. 58 for similar findings on music preference). These findings suggest that heightened reward sensitivity in mid-adolescence that was previously observed for monetary rewards 53 may also be present for social rewards such as likes on Instagram. However, further research is needed to examine whether this is a specific sensitivity in early, mid or late adolescence, or perhaps this social reward sensitivity emerges in adolescence and remains in adulthood.

Longitudinal neural developmental pattern of reward activity in adolescence. Longitudinal two-wave neural developmental pattern of nucleus accumbens activation during winning vs. losing, based on 249, and 238 participants who were included on the first and second time point, respectively (leading to 487 included brain scans in total). A quadratic pattern of brain activity was observed in the nucleus accumbens for the contrast winning > losing money in a gambling task, with highest reward activity in mid-adolescence. (Adapted with permission from Braams et al. 55 )

Online peer influence

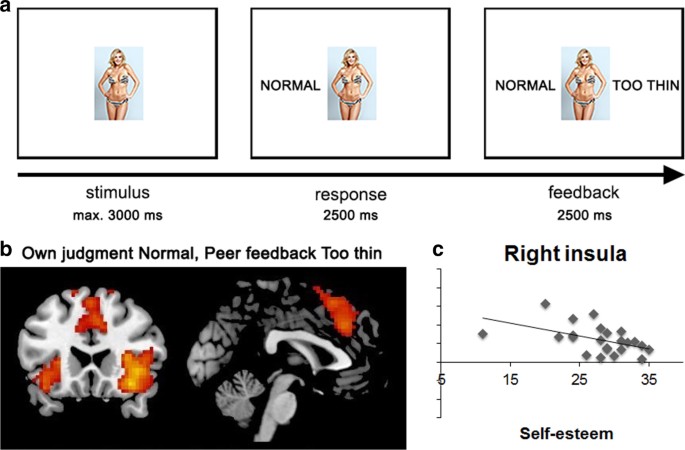

In addition to adolescents’ sensitivity to the feeling of belonging to the peer group 59 , the peer group also has a strong influence on opinions and decision-making 60 . Peers can exert a strong influence on adolescents through user-generated content on social media 5 , 61 . Co-viewing, sharing, and discussing media content with peers is common practice among adolescents in line with their developmental stage in which peers become more important than others. For example, adolescent girls often share pictures and comment on the “ideal” degree of slimness of the models they see via media when deciding how a ‘normal’ body should actually look 62 , 63 . Several recent neuroimaging studies, summarized below, have examined how the adolescent brain responds to peer comments about others and self, and subsequent behavioral adjustments and opinion changes. Even though not all of these designs were specific for online environments, the findings provide important starting points for understanding how adolescents are influenced by peer feedback in an online environment.

Neural responses to online peer feedback

Neuroimaging studies in adolescents showed that peer feedback indeed influences adolescents’ behavior. Neural correlates may provide more insight in the specific parts of the feedback that drives these behavioral sensitivities 64 . One way this is demonstrated is by having individuals rate certain products such as music preference or facial attractiveness. After their initial rating, participants received feedback from others, which was either congruent or incongruent with their initial rating. Afterwards, individuals made their ratings again, and the researchers analyzed whether behavior changed in the direction of the peer feedback. Indeed, both adults and adolescents adjusted their behavior towards the group norm 58 , 64 , demonstrating general sensitivity to peer influence. Furthermore, when receiving peer feedback that did not match their own initial rating, participants showed enhanced activity in the ACC and insula, two regions involved in detecting norm violations 58 , 65 . More specifically, increased ACC activity was associated with more adjustment to fit peer feedback norms in adolescents 58 .

Peer feedback effects are not only found for how individuals rate products, but also can strongly influence how they view themselves. Girls are especially sensitive to pressure for media’s thin-body ideal, and peer feedback supporting this ideal is associated with more body dissatisfaction 62 , 63 . We recently showed that norm-deviating feedback on ideal body images resulted in activity in the ACC-insula network in young females (18–19-years), which was stronger for females with lower self-esteem 66 (Fig. 4 ). Interestingly, the girls also adjusted their ratings on what they believed was a normal or too-thin looking body in the direction of the group norm. Together, these findings suggest that peer feedback through social media can influence the way adolescents look at themselves and others.

The Body Image Paradigm to study combined media and peer influence. This paradigm is designed for experiments to study the influence of peers on body image perception. a Participants are presented with a bikini model, and they can make a judgment whether the model is too thin or of normal weight. Their response appears on the left side of the model. Then, they are presented with ostensible peer feedback (the peer norm). b When this feedback deviates from their own judgment, this is associated with increased activity in dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and bilateral insula, regions often implicated in processing norm violations. c Responses are larger for participants with lower self-esteem (Adapted from Van der Meulen et al. 66 )

Neural responses to prosocial peer feedback