Teaching Methods and Strategies: The Complete Guide

You’ve completed your coursework. Student teaching has ended. You’ve donned the cap and gown, crossed the stage, smiled with your diploma and went home to fill out application after application.

Suddenly you are standing in what will be your classroom for the next year and after the excitement of decorating it wears off and you begin lesson planning, you start to notice all of your lessons are executed the same way, just with different material. But that is what you know and what you’ve been taught, so you go with it.

After a while, your students are bored, and so are you. There must be something wrong because this isn’t what you envisioned teaching to be like. There is.

Figuring out the best ways you can deliver information to students can sometimes be even harder than what students go through in discovering how they learn best. The reason is because every single teacher needs a variety of different teaching methods in their theoretical teaching bag to pull from depending on the lesson, the students, and things as seemingly minute as the time the class is and the subject.

Using these different teaching methods, which are rooted in theory of different teaching styles, will not only help teachers reach their full potential, but more importantly engage, motivate and reach the students in their classes, whether in person or online.

Teaching Methods

Teaching methods, or methodology, is a narrower topic because it’s founded in theories and educational psychology. If you have a degree in teaching, you most likely have heard of names like Skinner, Vygotsky , Gardner, Piaget , and Bloom . If their names don’t ring a bell, you should definitely recognize their theories that have become teaching methods. The following are the most common teaching theories.

Behaviorism

Behaviorism is the theory that every learner is essentially a “clean slate” to start off and shaped by emotions. People react to stimuli, reactions as well as positive and negative reinforcement, the site states.

Learning Theories names the most popular theorists who ascribed to this theory were Ivan Pavlov, who many people may know with his experiments with dogs. He performed an experiment with dogs that when he rang a bell, the dogs responded to the stimuli; then he applied the idea to humans.

Other popular educational theorists who were part of behaviorism was B.F. Skinner and Albert Bandura .

Social Cognitive Theory

Social Cognitive Theory is typically spoken about at the early childhood level because it has to do with critical thinking with the biggest concept being the idea of play, according to Edwin Peel writing for Encyclopedia Britannica . Though Bandura and Lev Vygotsky also contributed to cognitive theory, according to Dr. Norman Herr with California State University , the most popular and first theorist of cognitivism is Piaget.

There are four stages to Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development that he created in 1918. Each stage correlates with a child’s development from infancy to their teenage years.

The first stage is called the Sensorimotor Stage which occurs from birth to 18 months. The reason this is considered cognitive development is because the brain is literally growing through exploration, like squeaking horns, discovering themselves in mirrors or spinning things that click on their floor mats or walkers; creating habits like sleeping with a certain blanket; having reflexes like rubbing their eyes when tired or thumb sucking; and beginning to decipher vocal tones.

The second stage, or the Preoperational Stage, occurs from ages 2 to 7 when toddlers begin to understand and correlate symbols around them, ask a lot of questions, and start forming sentences and conversations, but they haven’t developed perspective yet so empathy does not quite exist yet, the website states. This is the stage when children tend to blurt out honest statements, usually embarrassing their parents, because they don’t understand censoring themselves either.

From ages 7 to 11, children are beginning to problem solve, can have conversations about things they are interested in, are more aware of logic and develop empathy during the Concrete Operational Stage.

The final stage, called the Formal Operational Stage, though by definition ends at age 16, can continue beyond. It involves deeper thinking and abstract thoughts as well as questioning not only what things are but why the way they are is popular, the site states. Many times people entering new stages of their lives like high school, college, or even marriage go through elements of Piaget’s theory, which is why the strategies that come from this method are applicable across all levels of education.

The Multiple Intelligences Theory

The Multiple Intelligences Theory states that people don’t need to be smart in every single discipline to be considered intelligent on paper tests, but that people excel in various disciplines, making them exceptional.

Created in 1983, the former principal in the Scranton School District in Scranton, PA, created eight different intelligences, though since then two others have been debated of whether to be added but have not yet officially, according to the site.

The original eight are musical, spatial, linguistic, mathematical, kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal and naturalistic and most people have a predominant intelligence followed by others. For those who are musically-inclined either via instruments, vocals, has perfect pitch, can read sheet music or can easily create music has Musical Intelligence.

Being able to see something and rearrange it or imagine it differently is Spatial Intelligence, while being talented with language, writing or avid readers have Linguistic Intelligence. Kinesthetic Intelligence refers to understanding how the body works either anatomically or athletically and Naturalistic Intelligence is having an understanding of nature and elements of the ecosystem.

The final intelligences have to do with personal interactions. Intrapersonal Intelligence is a matter of knowing oneself, one’s limits, and their inner selves while Interpersonal Intelligence is knowing how to handle a variety of other people without conflict or knowing how to resolve it, the site states. There is still an elementary school in Scranton, PA named after their once-principal.

Constructivism

Constructivism is another theory created by Piaget which is used as a foundation for many other educational theories and strategies because constructivism is focused on how people learn. Piaget states in this theory that people learn from their experiences. They learn best through active learning , connect it to their prior knowledge and then digest this information their own way. This theory has created the ideas of student-centered learning in education versus teacher-centered learning.

Universal Design for Learning

The final method is the Universal Design for Learning which has redefined the educational community since its inception in the mid-1980s by David H. Rose. This theory focuses on how teachers need to design their curriculum for their students. This theory really gained traction in the United States in 2004 when it was presented at an international conference and he explained that this theory is based on neuroscience and how the brain processes information, perform tasks and get excited about education.

The theory, known as UDL, advocates for presenting information in multiple ways to enable a variety of learners to understand the information; presenting multiple assessments for students to show what they have learned; and learn and utilize a student’s own interests to motivate them to learn, the site states. This theory also discussed incorporating technology in the classroom and ways to educate students in the digital age.

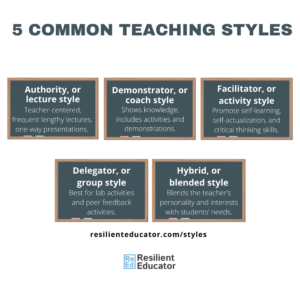

Teaching Styles

From each of the educational theories, teachers extract and develop a plethora of different teaching styles, or strategies. Instructors must have a large and varied arsenal of strategies to use weekly and even daily in order to build rapport, keep students engaged and even keep instructors from getting bored with their own material. These can be applicable to all teaching levels, but adaptations must be made based on the student’s age and level of development.

Differentiated instruction is one of the most popular teaching strategies, which means that teachers adjust the curriculum for a lesson, unit or even entire term in a way that engages all learners in various ways, according to Chapter 2 of the book Instructional Process and Concepts in Theory and Practice by Celal Akdeniz . This means changing one’s teaching styles constantly to fit not only the material but more importantly, the students based on their learning styles.

Learning styles are the ways in which students learn best. The most popular types are visual, audio, kinesthetic and read/write , though others include global as another type of learner, according to Akdeniz . For some, they may seem self-explanatory. Visual learners learn best by watching the instruction or a demonstration; audio learners need to hear a lesson; kinesthetic learners learn by doing, or are hands-on learners; read/write learners to best by reading textbooks and writing notes; and global learners need material to be applied to their real lives, according to The Library of Congress .

There are many activities available to instructors that enable their students to find out what kind of learner they are. Typically students have a main style with a close runner-up, which enables them to learn best a certain way but they can also learn material in an additional way.

When an instructor knows their students and what types of learners are in their classroom, instructors are able to then differentiate their instruction and assignments to those learning types, according to Akdeniz and The Library of Congress. Learn more about different learning styles.

When teaching new material to any type of learner, is it important to utilize a strategy called scaffolding . Scaffolding is based on a student’s prior knowledge and building a lesson, unit or course from the most foundational pieces and with each step make the information more complicated, according to an article by Jerry Webster .

To scaffold well, a teacher must take a personal interest in their students to learn not only what their prior knowledge is but their strengths as well. This will enable an instructor to base new information around their strengths and use positive reinforcement when mistakes are made with the new material.

There is an unfortunate concept in teaching called “teach to the middle” where instructors target their lessons to the average ability of the students in their classroom, leaving slower students frustrated and confused, and above average students frustrated and bored. This often results in the lower- and higher-level students scoring poorly and a teacher with no idea why.

The remedy for this is a strategy called blended learning where differentiated instruction is occurring simultaneously in the classroom to target all learners, according to author and educator Juliana Finegan . In order to be successful at blended learning, teachers once again need to know their students, how they learn and their strengths and weaknesses, according to Finegan.

Blended learning can include combining several learning styles into one lesson like lecturing from a PowerPoint – not reading the information on the slides — that includes cartoons and music associations while the students have the print-outs. The lecture can include real-life examples and stories of what the instructor encountered and what the students may encounter. That example incorporates four learning styles and misses kinesthetic, but the activity afterwards can be solely kinesthetic.

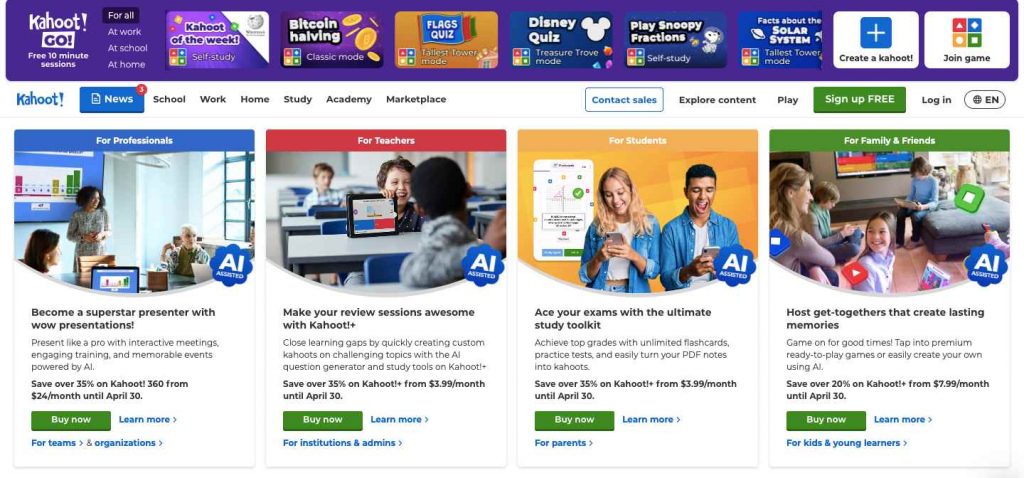

A huge component of blended learning is technology. Technology enables students to set their own pace and access the resources they want and need based on their level of understanding, according to The Library of Congress . It can be used three different ways in education which include face-to-face, synchronously or asynchronously . Technology used with the student in the classroom where the teacher can answer questions while being in the student’s physical presence is known as face-to-face.

Synchronous learning is when students are learning information online and have a teacher live with them online at the same time, but through a live chat or video conferencing program, like Skype, or Zoom, according to The Library of Congress.

Finally, asynchronous learning is when students take a course or element of a course online, like a test or assignment, as it fits into their own schedule, but a teacher is not online with them at the time they are completing or submitting the work. Teachers are still accessible through asynchronous learning but typically via email or a scheduled chat meeting, states the Library of Congress.

The final strategy to be discussed actually incorporates a few teaching strategies, so it’s almost like blended teaching. It starts with a concept that has numerous labels such as student-centered learning, learner-centered pedagogy, and teacher-as-tutor but all mean that an instructor revolves lessons around the students and ensures that students take a participatory role in the learning process, known as active learning, according to the Learning Portal .

In this model, a teacher is just a facilitator, meaning that they have created the lesson as well as the structure for learning, but the students themselves become the teachers or create their own knowledge, the Learning Portal says. As this is occurring, the instructor is circulating the room working as a one-on-one resource, tutor or guide, according to author Sara Sanchez Alonso from Yale’s Center for Teaching and Learning. For this to work well and instructors be successful one-on-one and planning these lessons, it’s essential that they have taken the time to know their students’ history and prior knowledge, otherwise it can end up to be an exercise in futility, Alonso said.

Some activities teachers can use are by putting students in groups and assigning each student a role within the group, creating reading buddies or literature circles, making games out of the material with individual white boards, create different stations within the classroom for different skill levels or interest in a lesson or find ways to get students to get up out of their seats and moving, offers Fortheteachers.org .

There are so many different methodologies and strategies that go into becoming an effective instructor. A consistent theme throughout all of these is for a teacher to take the time to know their students because they care, not because they have to. When an instructor knows the stories behind the students, they are able to design lessons that are more fun, more meaningful, and more effective because they were designed with the students’ best interests in mind.

There are plenty of pre-made lessons, activities and tests available online and from textbook publishers that any teacher could use. But you need to decide if you want to be the original teacher who makes a significant impact on your students, or a pre-made teacher a student needs to get through.

Read Also: – Blended Learning Guide – Collaborative Learning Guide – Flipped Classroom Guide – Game Based Learning Guide – Gamification in Education Guide – Holistic Education Guide – Maker Education Guide – Personalized Learning Guide – Place-Based Education Guide – Project-Based Learning Guide – Scaffolding in Education Guide – Social-Emotional Learning Guide

Similar Posts:

- Discover Your Learning Style – Comprehensive Guide on Different Learning Styles

- 35 of the BEST Educational Apps for Teachers (Updated 2024)

- 15 Learning Theories in Education (A Complete Summary)

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

Support our educational content for free when you buy through links on our site. Learn more

[2023] The Ultimate Guide to Teaching Methods and Strategies: Expert Advice for Classroom Success

- June 11, 2023

- Instructional Coaching

As educators and teachers, we understand that finding the right teaching methods and strategies is crucial for classroom success. With so many different options out there, it can be overwhelming to determine which approach is best. That's why our team at Teacher Strategies™ has compiled the ultimate guide to teaching methods and strategies, filled with expert advice and tips to help you find the best approach for your classroom.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The importance of teaching methods, lecture method, discussion method, demonstration method, cooperative learning method, inquiry-based method, project-based learning method, flipped classroom method, personalized education method, the pros and cons of different teaching methods, direct instruction, inquiry-based learning, cooperative learning, personalized learning, flipped classroom, interactive, self-discovery, instructional methods in education, quick tips and facts.

The success of any classroom largely depends on the effectiveness of the teaching methods and strategies employed by their teachers. Using outdated or ineffective methods can bore and disengage students, while innovative and engaging approaches can inspire learning and foster student success. The goal of this guide is to help you find the best teaching methods and strategies to suit your unique classroom and teaching style.

The right teaching method can make all the difference in student success. Effective teaching methods ensure that information is being delivered in a way that's engaging and meaningful. Not all students learn the same way, and using a variety of teaching methods can help ensure that every student is able to understand and retain information. Additionally, using innovative teaching methods shows students that you care about their learning and are willing to try new approaches to help them succeed.

Different Types of Teaching Methods and Strategies

Lecturing is a popular method of teaching that involves the teacher providing information to the students through a verbal presentation. This method is best suited for delivering large amounts of information in a relatively short amount of time, and it allows students to take notes and ask questions. However, lectures can be a passive form of learning for students and are not always the most engaging method.

The discussion method involves encouraging student participation through group discussions and debates. This method is excellent for developing critical thinking skills, encouraging student engagement, and promoting collaboration. However, it can be difficult to manage and may not be ideal for every subject.

The demonstration method involves teachers demonstrating how to complete a task or solve a problem. This method can be useful for subjects that require hands-on learning, such as science or art. However, it may not be effective for all students and may require more time for preparation.

Cooperative learning involves students working together in groups to achieve a common goal. This method promotes teamwork and collaboration, and can help to develop communication skills. However, it can be difficult to manage and may not work best with all students.

The inquiry-based method involves students exploring a topic or problem on their own, using critical thinking skills and problem-solving strategies. This method promotes self-directed learning and can be highly engaging for students. However, it requires a high level of preparation and may not be suitable for every subject or classroom.

Project-based learning involves students working on a long-term project to achieve a goal or solve a problem. This method promotes creativity, critical thinking, and teamwork. However, it can be difficult to manage and may require more time for preparation.

The flipped classroom method involves students learning material at home through a pre-recorded lecture, while the in-class time is spent on hands-on group activities and projects. This method allows for more personalized learning and fosters student engagement. However, it requires a high level of preparation and may not work best with all students.

Personalized education involves tailoring the learning experience to the individual student's needs, strengths, and interests. This method can be highly effective for engaging students and encouraging critical thinking. However, it requires a high level of preparation and may not be suitable for every subject or classroom.

No method is perfect, and understanding the pros and cons of each approach is essential. Here are a few pros and cons of each method:

- Pros: Fast delivery of information, cost-effective, and easy to implement.

- Cons: Passive form of learning, not suitable for all subjects, and requires the right environment to be successful.

- Pros: Encourages critical thinking, promotes collaboration, and engaging for students.

- Cons: Difficult to manage, can be hard to keep students focused, and not suitable for all subjects.

- Pros: Useful for hands-on learning, can be visual and engaging.

- Cons: Limited in effectiveness, may be costly, and time-consuming to prepare.

- Pros: Promotes teamwork, communication, and critical thinking skills.

- Cons: Can be difficult to manage, may be uncomfortable for some students, and not suitable for all subjects.

- Pros: Promotes critical thinking and creativity, fosters engagement and self-directed learning.

- Cons: High level of preparation, may not work with all students, and can be difficult to manage.

- Pros: Promotes critical thinking, creativity, and teamwork.

- Cons: Can be challenging to manage, may be time-consuming to prepare, and not suitable for all subjects.

- Pros: Allows for personalized learning, fosters student engagement, and promotes critical thinking and collaboration.

- Cons: Requires a high level of preparation, not suitable for all students, and can be difficult to manage.

- Pros: Tailored to individual needs and interests, fosters student engagement and critical thinking.

- Cons: Requires a high level of preparation, not suitable for all students, and can be challenging to manage.

What are the 5 Teaching Approaches?

There are five main teaching approaches that educators can use in the classroom. Understanding each approach can help you determine which is best for your classroom:

Direct instruction is a teacher-centered approach that involves lecture, demonstrations, and other activities designed to deliver large amounts of information to students quickly. This approach is best suited for subjects that require a lot of factual information and can be less engaging for students.

Inquiry-based learning is a student-centered approach that promotes self-directed learning through questioning and investigation. This method promotes critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity.

Cooperative learning involves students working together in groups to achieve a common goal. This approach promotes teamwork, collaboration, and communication skills.

Personalized learning tailors the learning experience to the individual student's needs, strengths, and interests. This approach can be highly engaging for students and encourages critical thinking and self-directed learning.

The flipped classroom approach involves reversing the traditional classroom model, with students learning material at home through a pre-recorded lecture, while the in-class time is spent on hands-on group activities and projects. This approach allows for more personalized learning, fosters student engagement, and promotes critical thinking and collaboration.

The Four Types of Instructional Methods

Instructional methods are the specific techniques or strategies used to deliver information to students. There are four main types of instructional methods:

Expository instructional methods involve lecturing, reading, or demonstrating to impart information to students. This method is best suited for subjects that require a lot of factual information.

Interactive instructional methods involve activities that require students to be actively engaged in the learning process. This method promotes critical thinking and problem-solving.

Mastery instructional methods involve teaching a skill or concept until the student has mastered it. This approach requires targeted instruction and assessment to ensure that students have a strong foundation before moving on to the next topic.

Self-discovery instructional methods involve encouraging students to explore a topic or problem on their own, using critical thinking skills and problem-solving strategies. This method promotes self-directed learning and can be highly engaging for students.

Instructional methods are essential in education, as they define how information is delivered to students. Different methods work best for different subjects, and some may be more effective than others depending on the teacher, curriculum, and goals of the lesson. As teachers, it's essential to approach instruction with an open mind, experimenting with new methods and techniques as needed.

- Understand your students' learning styles to determine which teaching methods will work best.

- Not all teaching methods work for every student or every subject – experimenting with different approaches can help you discover what works best for your classroom.

- Use a combination of teaching methods to keep students engaged and interested.

- Technology can be an effective tool for engaging students and delivering information in new and innovative ways.

What are the different types of teaching methods?

The different types of teaching methods include: lecture, discussion, demonstration, cooperative learning, inquiry-based learning, project-based learning, flipped classroom, and personalized education.

What are the 5 teaching approaches?

The 5 teaching approaches are: direct instruction, inquiry-based learning, cooperative learning, personalized learning, and flipped classroom.

What are the four types of instructional methods?

The four types of instructional methods are expository, interactive, mastery, and self-discovery.

What are some teaching methods and strategies?

Effective teaching methods and strategies include using technology, personalized learning, inquiry-based learning, cooperative learning, and project-based learning.

What are instructional methods in education?

Instructional methods in education are the teaching techniques and strategies used to deliver information to students.

By understanding the different teaching methods and strategies available, you can develop a tailored approach that best suits your classroom and students. Experiment with different methods and techniques, and use technology to your advantage. With the right approach, you can inspire learning and foster student success. As a recommendation, we suggest starting with a mix of cooperative learning, project-based learning, and personalized education. Surveyed teachers have claimed these approaches enhance student engagement, collaboration, and critical thinking. Remember to always approach teaching methods with an open mind, and be willing to try new approaches to discover what works best for your students.

[1] https://learn.org/articles/Edutopia_An_Online_Community_for_Teachers_and_Students.html [2] [3] https://www.knewton.com/ [4] https://www.epa.gov/students [5] https://arapahoe.extension.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2020/05/Denver-STEM-resources-for-parents-and-teachers_.pdf [6] https://www.edutopia.org/technology-integration-guide-importance

Marti is a seasoned educator and strategist with a passion for fostering inclusive learning environments and empowering students through tailored educational experiences. With her roots as a university tutor—a position she landed during her undergraduate years—Marti has always been driven by the joy of facilitating others' learning journeys.

Holding a Bachelor's degree in Communication alongside a degree in Social Work, she has mastered the art of empathetic communication, enabling her to connect with students on a profound level. Marti’s unique educational background allows her to incorporate holistic approaches into her teaching, addressing not just the academic, but also the emotional and social needs of her students.

Throughout her career, Marti has developed and implemented innovative teaching strategies that cater to diverse learning styles, believing firmly that education should be accessible and engaging for all. Her work on the Teacher Strategies site encapsulates her extensive experience and dedication to education, offering readers insights into effective teaching methods, classroom management techniques, and strategies for fostering inclusive and supportive learning environments.

As an advocate for lifelong learning, Marti continuously seeks to expand her knowledge and skills, ensuring her teaching methods are both evidence-based and cutting edge. Whether through her blog articles on Teacher Strategies or her direct engagement with students, Marti remains committed to enhancing educational outcomes and inspiring the next generation of learners and educators alike.

Related Posts

What is core teaching [2024] ✅.

- March 20, 2024

Two Core Teaching Strategies You Must Try for Success in the Classroom [2024] ✅

What are the 4 a’s teaching strategies [2024] ✅.

- March 15, 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Add Comment *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Post Comment

Trending now

Request More Info

Fill out the form below and a member of our team will reach out right away!

" * " indicates required fields

The Complete List of Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods: Not as Simple as ABC

Teaching methods [teacher-centered], teaching methods [student-centered], what about blended learning and udl, teaching methods: a to z, for the love of teaching.

Whether you’re a longtime educator, preparing to start your first teaching job or mapping out your dream of a career in the classroom, the topic of teaching methods is one that means many different things to different people.

Your individual approaches and strategies to imparting knowledge to your students and inspiring them to learn are probably built on your academic education as well as your instincts and intuition.

Whether you come by your preferred teaching methods organically or by actively studying educational theory and pedagogy, it can be helpful to have a comprehensive working knowledge of the various teaching methods at your disposal.

[Download] Get the Complete List of Teaching Methods PDF Now >>

The teacher-centered approach vs. the student-centered approach. High-tech vs. low-tech approaches to learning. Flipped classrooms, differentiated instruction, inquiry-based learning, personalized learning and more.

Not only are there dozens of teaching methods to explore, it is also important to have a sense for how they often overlap or interrelate. One extremely helpful look at this question is offered by the teacher-focused education website Teach.com.

“Teaching theories can be organized into four categories based on two major parameters: a teacher-centered approach versus a student-centered approach, and high-tech material use versus low-tech material use,” according to the informative Teach.com article , which breaks down a variety of influential teaching methods as follows:

Teacher-Centered Approach to Learning Teachers serve as instructor/authority figures who deliver knowledge to their students through lectures and direct instruction, and aim to measure the results through testing and assessment. This method is sometimes referred to as “sage on the stage.”

Student-Centered Approach to Learning Teachers still serve as an authority figure, but may function more as a facilitator or “guide on the side,” as students assume a much more active role in the learning process. In this method, students learn from and are continually assessed on such activities as group projects, student portfolios and class participation.

High-Tech Approach to Learning From devices like laptops and tablets to using the internet to connect students with information and people from around the world, technology plays an ever-greater role in many of today’s classrooms. In the high-tech approach to learning, teachers utilize many different types of technology to aid students in their classroom learning.

Low-Tech Approach to Learning Technology obviously comes with pros and cons, and many teachers believe that a low-tech approach better enables them to tailor the educational experience to different types of learners. Additionally, while computer skills are undeniably necessary today, this must be balanced against potential downsides; for example, some would argue that over-reliance on spell check and autocorrect features can inhibit rather than strengthen student spelling and writing skills.

Diving further into the overlap between different types of teaching methods, here is a closer look at three teacher-centered methods of instruction and five popular student-centered approaches.

Direct Instruction (Low Tech) Under the direct instruction model — sometimes described as the “traditional” approach to teaching — teachers convey knowledge to their students primarily through lectures and scripted lesson plans, without factoring in student preferences or opportunities for hands-on or other types of learning. This method is also customarily low-tech since it relies on texts and workbooks rather than computers or mobile devices.

Flipped Classrooms (High Tech) What if students did the “classroom” portion of their learning at home and their “homework” in the classroom? That’s an oversimplified description of the flipped classroom approach, in which students watch or read their lessons on computers at home and then complete assignments and do problem-solving exercises in class.

Kinesthetic Learning (Low Tech) In the kinesthetic learning model, students perform hands-on physical activities rather than listening to lectures or watching demonstrations. Kinesthetic learning, which values movement and creativity over technological skills, is most commonly used to augment traditional types of instruction — the theory being that requiring students to do, make or create something exercises different learning muscles.

Differentiated Instruction (Low Tech) Inspired by the 1975 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), enacted to ensure equal access to public education for all children, differentiated instruction is the practice of developing an understanding of how each student learns best, and then tailoring instruction to meet students’ individual needs.

In some instances, this means Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) for students with special needs, but today teachers use differentiated instruction to connect with all types of learners by offering options on how students access content, the types of activities they do to master a concept, how student learning is assessed and even how the classroom is set up.

Inquiry-Based Learning (High Tech) Rather than function as a sole authority figure, in inquiry-based learning teachers offer support and guidance as students work on projects that depend on them taking on a more active and participatory role in their own learning. Different students might participate in different projects, developing their own questions and then conducting research — often using online resources — and then demonstrate the results of their work through self-made videos, web pages or formal presentations.

Expeditionary Learning (Low Tech) Expeditionary learning is based on the idea that there is considerable educational value in getting students out of the classroom and into the real world. Examples include trips to City Hall or Washington, D.C., to learn about the workings of government, or out into nature to engage in specific study related to the environment. Technology can be used to augment such expeditions, but the primary focus is on getting out into the community for real-world learning experiences.

Personalized Learning (High Tech) In personalized learning, teachers encourage students to follow personalized, self-directed learning plans that are inspired by their specific interests and skills. Since assessment is also tailored to the individual, students can advance at their own pace, moving forward or spending extra time as needed. Teachers offer some traditional instruction as well as online material, while also continually reviewing student progress and meeting with students to make any needed changes to their learning plans.

Game-Based Learning (High Tech) Students love games, and considerable progress has been made in the field of game-based learning, which requires students to be problem solvers as they work on quests to accomplish a specific goal. For students, this approach blends targeted learning objectives with the fun of earning points or badges, much like they would in a video game. For teachers, planning this type of activity requires additional time and effort, so many rely on software like Classcraft or 3DGameLab to help students maximize the educational value they receive from within the gamified learning environment.

Blended Learning Blended learning is another strategy for teachers looking to introduce flexibility into their classroom. This method relies heavily on technology, with part of the instruction taking place online and part in the classroom via a more traditional approach, often leveraging elements of the flipped classroom approach detailed above. At the heart of blended learning is a philosophy of taking the time to understand each student’s learning style and develop strategies to teach to every learner, by building flexibility and choice into your curriculum.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) UDL incorporates both student-centered learning and the “multiple intelligences theory,” which holds that different learners are wired to learn most effectively in different ways (examples of these “intelligences” include visual-spatial, logical-mathematical, bodily-kinesthetic, linguistic, musical, etc.). In practice, this could mean that some students might be working on a writing project while others would be more engaged if they created a play or a movie. UDL emphasizes the idea of teaching to every student, special needs students included, in the general education classroom, creating community and building knowledge through multiple means.

In addition to the many philosophical and pedagogical approaches to teaching, classroom educators today employ diverse and sometimes highly creative methods involving specific strategies, prompts and tools that require little explanation. These include:

- Appointments with students

- Art-based projects

- Audio tutorials

- Author’s chair

- Book reports

- Bulletin boards

- Brainstorming

- Case studies

- Chalkboard instruction

- Class projects

- Classroom discussion

- Classroom video diary

- Collaborative learning spaces

- Creating murals and montages

- Current events quizzes

- Designated quiet space

- Discussion groups

- DIY activities

- Dramatization (plays, skits, etc.)

- Educational games

- Educational podcasts

- Essays (Descriptive)

- Essays (Expository)

- Essays (Narrative)

- Essays (Persuasive)

- Exhibits and displays

- Explore different cultures

- Field trips

- Flash cards

- Flexible seating

- Gamified learning plans

- Genius hour

- Group discussion

- Guest speakers

- Hands-on activities

- Individual projects

- Interviewing

- Laboratory experiments

- Learning contracts

- Learning stations

- Literature circles

- Making posters

- Mock conventions

- Motivational posters

- Music from other countries/cultures

- Oral reports

- Panel discussions

- Peer partner learning

- Photography

- Problem solving activities

- Reading aloud

- Readers’ theater

- Reflective discussion

- Research projects

- Rewards & recognition

- Role playing

- School newspapers

- Science fairs

- Sister city programs

- Spelling bees

- Storytelling

- Student podcasts

- Student portfolios

- Student presentations

- Student-conceived projects

- Supplemental reading assignments

- Team-building exercises

- Term papers

- Textbook assignments

- Think-tac-toe

- Time capsules

- Use of community or local resources

- Video creation

- Video lessons

- Vocabulary lists

So, is the teacher the center of the educational universe or the student? Does strong reliance on the wonders of technology offer a more productive educational experience or is a more traditional, lower-tech approach the best way to help students thrive?

Questions such as these are food for thought for educators everywhere, in part because they inspire ongoing reflection on how to make a meaningful difference in the lives of one’s students.

Be Sure To Share This Article

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

In our free guide, you can learn about a variety of teaching methods to adopt in the classroom.

- Master of Education

Related Posts

Teaching Plan Templates: Effective Methods For Teaching

August 25th, 2022

Share via Twitter

Share via Facebook

Share via LinkedIn

Amy Stock, MS

Product Specialist

Teaching or lesson plan templates help teachers organize their ideas, assist with time management, and provide an efficient design for organizing content instruction, activities, and assessments.

Here are several examples of teaching plan templates to try:

Class Templates

Elements of an Effective Teaching Plan Template

Teaching plan templates can vary in format and appearance, but will generally contain the same basic elements:

1. Learning Objective

The learning objective details what your students should know or do by the end of the class. This is the most critical part of every lesson and, therefore, of every teaching plan. Establish your curriculum-required learning goals for each lesson and list them at the top of each teaching plan template. The content section will have a place for objectives and might also have a place for a quick-look outline of the lesson.

2. Instruction Time-Planning

Assigning each lesson the number of days to teach it will require a detailed breakdown of everything involved in preparing the content. Include flexible options such as extra activities or shortcuts to maximize instruction time while completing the lesson within the scheduled time frame. An inclusive schedule provides enough information that a substitute or other staff member could follow the directions to deliver the lesson.

3. Subtopics

If the teaching plan covers more extended units, it is essential to establish specific subtopics, each with its own goals, assignments, materials, and assessments. The lessons within the unit should flow smoothly from one topic to the next so that students can successfully understand the material.

4. Assignments and Assessments

Each lesson should include a variety of in-class or at-home work for students to practice or study the material. Periodic assessments evaluate the effectiveness of instruction and student comprehension. Assignments and Assessments are essential to provide additional assistance to students as needed and to modify and adjust for the future based on data collected through assessment.

5. Duration of Lectures

To avoid confusion, teachers should explicitly state the intended duration of direct teaching or lectures on the teaching plan template, especially if class duration varies or when the teaching plan covers an extended period.

6. List of Materials and References

To make it easier to prepare materials, technology, and other resources, list every requirement, material, and all necessary references. This list can also help students ensure they have all the required reading materials or other components for projects and activities.

Three Reasons to Use Teaching Plans

1. Standardizes Lesson Components - Teaching plans can organize thoughts and are helpful when scheduling what to teach each day of the semester. In addition, teaching plans also help substitute teachers fill in and understand the lesson objective to prevent students from missing a day of learning.

2. Saves Work Hours - Depending on the school’s schedule style, teachers may have four to eight classes per semester, and each course requires a teaching plan. Using a teaching plan template streamlines thoughts and saves teachers dozens of work hours so they can spend more time with students or families.

3. Maintains School and State Requirements - Most schools and some states require teachers to keep lesson plans available for administrative or parental oversight. Using a teaching plan template provides the necessary information in an abbreviated format.

Eight Steps to Creating an Effective Teaching Plan

1. Advanced Planning

While a teaching plan template provides a measure of automation to make the lesson plan design process more straightforward, still, it is worthless unless the teacher understands the learning objective and plans for the lesson’s progression, including all activities, assessments, and resources.

2. Time Management Flexibility

When designing a lesson, time management is crucial. Prepare additional activities to ensure students are engaged throughout instruction time, but also have shortcuts in case activities run long. Any class has the potential to run short or long based on many variables, including students who have additional questions, students who are struggling to understand the concepts, or a class that flies through an activity faster than a teacher anticipated.

3. Avoid Repetition and Omission

A well-designed teaching plan aims to ensure that all material is covered effectively without leaving out some part of the lesson or unnecessarily repeating a portion. A teaching template can help keep order out of what could be chaos.

4. Maintain a Results-oriented Approach

A successful lesson plan helps the teacher focus on target learning goals. Working backwards, teachers can develop an assessment to evaluate student knowledge of the learning target and then prepare instruction and activities that provide the students with the tools needed to perform well on that assessment.

Using a teaching plan template that provides sections for each component of the lesson allows teachers to plan the assessment and then work their way up the page to specific activities for maximum effectiveness.

5. Simplify the Content

Like everyone, sometimes teachers miss work. A teaching plan template and user-friendly instructions can be lifesavers for a substitute teacher or anyone who temporarily takes over class instruction.

6. Understand the Content

No matter how great the template or how efficient the lesson plan is, the teacher is still responsible for knowing the material to such an extent that they can field any questions that students may have. Whether on the content itself or to facilitate understanding of a project or activity, take the time to prepare for questions that may arise.

7. Organize Your Resources

Ensure all resources, activities, and other required materials are listed on the teaching plan and are readily available and accessible when needed. A good teaching plan template provides a place to describe lesson requirements, technology, activities, printouts, and assessments.

In Conclusion

Teachers need an effective teaching plan to keep track of every lesson in every unit of each course they teach over a year. Therefore, any opportunity to streamline the process to save time and provide a more efficient end product will improve student education and provide better results.

The teaching plan template is a provably efficient and successful way to organize learning goals and content into manageable chunks while organizing those chunks into a logical order of instruction.

If your school is interested in automating tasks and streamlining processes, Education Advanced offers a suite of tools that may be able to help. For teachers specifically interested in automating their curriculum:

Embarc, our curriculum mapping software , helps teachers quickly analyze whether or not their curriculum is aligned with state and national standards as well as share best practice curriculum plans with other teachers to reduce duplication and with parents to keep everyone up to date.

For schools looking to automate time consuming tasks:

Cardonex, our master schedule software helps schools save time on building master schedules. Many schools used to spend weeks using white boards to organize the right students, teachers, and classrooms into the right order so that students could graduate on time and get their preferred classes. However, can now be used to automate this task and within a couple of days deliver 90% of students first choice classes.

Testhound, our test accommodation software , helps schools coordinating thousands of students across all state and local K-12 school assessments while taking into account dozens of accommodations (reading disabilities, physical disabilities, translations, etc.) for students.

More Great Content

We know you’ll love

Stay In the Know

Subscribe to our newsletter today!

- Try for free

Lesson Methodologies

Jabberwocky

Methodology is the way(s) in which teachers share information with students. The information itself is known as the content ; how that content is shared in a classroom is dependent on the teaching methods.

The following chart lists a wide variety of lesson methodologies appropriate for the presentation of material, which I will discuss here. Notice how these teaching methods move from Least Impact and Involvement (for students) to Greatest Impact and Involvement.

As you look at the chart, you'll notice that lecture, for example, is a way of providing students with basic knowledge. You'll also note that lecture has the least impact on students as well as the lowest level of student involvement. As you move up the scale (from left to right), you'll note how each successive method increases the level of impact and involvement for students. At the top, reflective inquiry has the highest level of student involvement. It also has the greatest impact of all the methods listed.

Knowledge is the basic information of a subject; the facts and data of a topic. Synthesis is the combination of knowledge elements that form a new whole. Performance refers to the ability to effectively use new information in a productive manner.

Across the bottom of the chart are three categories: knowledge, synthesis, and performance. These refer to the impact of each method in terms of how well students will utilize it. For example, lecture is simply designed to provide students with basic knowledge about a topic. Reflective inquiry, on the other hand, offers opportunities for students to use knowledge in a productive and meaningful way.

Now let's take a look at each of those three major categories and the methodologies that are part of each one.

How do you present basic information to your students? It makes no difference whether you're sharing consonant digraphs with your first-grade students or differential calculus with your twelfth-grade students; you must teach them some basic information. You have several options for sharing that information.

Lecture is an arrangement in which teachers share information directly with students, with roots going back to the ancient Greeks. Lecture is a familiar form of information-sharing, but it is not without its drawbacks. It has been overused and abused, and it is often the method used when teachers don't know or aren't familiar with other avenues of presentation. Also, many lecturers might not have been the best teacher role models in school.

Often, teachers assume that lecturing is nothing more than speaking to a group of students. Wrong! Good lecturing also demonstrates a respect for the learner, a knowledge of the content, and an awareness of the context in which the material is presented.

Good lectures must be built on three basic principles:

Knowing and responding to the background knowledge of the learner is necessary for an effective lecture.

Having a clear understanding of the material is valuable in being able to explain it to others.

The physical design of the room and the placement of students impact the effectiveness of a lecture.

Lecture is often the method of choice when introducing and explaining new concepts. It can also be used to add insight and expand on previously presented material. Teachers recommend that the number of concepts (within a single lesson) be limited to one or two at the elementary level and three to five at the secondary level.

It's important to keep in mind that lecture need not be a long and drawn-out affair. For example, the 10-2 strategy is an easily used, amazingly effective tool for all grade levels. In this strategy, no more than 10 minutes of lecture should occur before students are allowed 2 minutes for processing. This is also supportive of how the brain learns (see Effective Learning and How Students Learn ). When 10-2 is used in both elementary and secondary classrooms, the rate of both comprehension and retention of information increases dramatically.

During the 2-minute break, you can ask students several open-ended questions, such as the following:

“What have you learned so far in this lesson?”

“Why is this information important?”

“How does this information relate to any information we have learned previously?”

“How do you feel about your progress so far?”

“How does this data apply to other situations?”

These questions can be answered individually, in small group discussions, or as part of whole class interactions.

The value of the 10-2 strategy is that it can be used with all types of content. Equally important, it has a positive effect on brain growth.

Lectures are information-sharing tools for any classroom teacher. However, it's critically important that you not use lecture as your one and only tool. You must supplement it with other instructional methods to achieve the highest levels of comprehension and utility for your students.

Reading Information

With this method, you assign material from the textbook for students to read independently. You may also choose to have your students read other supplemental materials in addition to the textbook. These may include, but are not limited to children's or adolescent literature, brochures, flyers, pamphlets, and information read directly from a selected website.

In This Article:

Featured high school resources.

Related Resources

About the author

TeacherVision Editorial Staff

The TeacherVision editorial team is comprised of teachers, experts, and content professionals dedicated to bringing you the most accurate and relevant information in the teaching space.

- University News

- Faculty & Research

- Health & Medicine

- Science & Technology

- Social Sciences

- Humanities & Arts

- Students & Alumni

- Arts & Culture

- Sports & Athletics

- The Professions

- International

- New England Guide

The Magazine

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

Class Notes & Obituaries

- Browse Class Notes

- Browse Obituaries

Collections

- Commencement

- The Context

Harvard Squared

- Harvard in the Headlines

Support Harvard Magazine

- Why We Need Your Support

- How We Are Funded

- Ways to Support the Magazine

- Special Gifts

- Behind the Scenes

Classifieds

- Vacation Rentals & Travel

- Real Estate

- Products & Services

- Harvard Authors’ Bookshelf

- Education & Enrichment Resource

- Ad Prices & Information

- Place An Ad

Follow Harvard Magazine:

University News | 3.9.2022

An Expansive Vision for the Future of Teaching and Learning

Post-pandemic, what harvard might try in classrooms, course design, and global education.

A hybrid classroom at Harvard Business School, created to enable in-person and remote instruction during the pandemic. The new task force report assesses innovations like this, and their application to residential, hybrid, and remote teaching and learning in Harvard’s future. Photograph by Hensley Carrasco. Courtesy of Harvard Business School

The Harvard Future of Teaching and Learning Task Force (FTL), organized last year to assess what the University and its faculty members had learned from the pandemic pivot to remote instruction in the spring of 2020 and through the following academic year, released its report today. An ambitious effort, it is meant to spark conversation among professors, deans, and Harvard leaders concerning three overarching subjects, a sort of pedagogical hat trick:

•sustaining and building upon perceived gains in residential, classroom-based teaching and learning; •accelerating the creation and use of “short-form digital content”—learning units, exercises, and assessments that differ from traditional, semester-long courses, but are useful for both campus-based classes and a broad range of online formats; and •exploring Harvard’s prospects for becoming a global educator, using its faculty expertise, pedagogies, and technology to “engage 5 percent of the global population in the shared pursuit of community and learning”—an “aspirational vision” that goes way beyond the 1,650 or so undergraduates enrolled in each new class, or the 22,500 students enrolled in all degree programs of late.

The task force , chaired by Bharat Anand, the vice provost for advances in learning, defined its work in terms of capturing systematically the effects of the changes in teaching and learning forced by the pandemic, applying those to further enhancements, and determining the implications for Harvard’s mission and future learners more broadly.

In fact, he said in a conversation, faculty members’ online and technologically enabled teaching extended back more than a decade to the Harvard-MIT edX venture . The first part of the new report distills what was learned from that initial foray into translating full courses for free online distribution; subsequent, more focused efforts aimed at smaller learner cohorts and different phases of their education ; and extensive, successful online operations at the Extension School.

Together, those efforts familiarized many faculty members with new ways of teaching, even before the pandemic forced all classes off campus. And the more recent experiments brought forth important discoveries about using online tools to engage students, test their command of material frequently, enable them to learn from one another, and form their own learner communities (albeit online): a new form of the collaborative experiences that enrich residential, campus-based learning, for people who do not have the opportunity to access those options.

Finley professor of engineering and applied sciences Michael D. Smith, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences when edX was launched and now a task force member, said that the pandemic forced all faculty members, students, and staff to think creatively and more explicitly about teaching: “We had to!” Even as that experience recedes, he continued, it has sparked continuing conversations among professors across the University, making this “an incredibly generative time for us if we grab this opportunity” to improve the classroom experience and “set up Harvard’s digital footprint.”

The task force divided its work roughly into three parts, including “blended learning” (in classrooms with online elements, and online with in-person elements), led by Harvard Graduate School of Education dean Bridget Terry Long; content, led by Anand; and global reach, led by Smith.

Reimagining the “Classroom”

Anand emphasized that technology’s educational role is as “an enabler. Pedagogy is at the heart of what makes the magic in classrooms.” That said, faculty members suddenly learned a great deal about what actually works when their courses transitioned from the classroom to Zoom.

It had been generally known, from edX and other formats, that a full-length lecture, transmitted and disseminated to a screen (what Anand calls sending the class out like a PDF), results in passive experiences. Most learners haven’t the attention span to stay focused on what is transpiring. As the report puts it, “Long lectures that were familiar in the residential classroom, or to which faculty and students had become accustomed, did not work well online.”

Smith said he and colleagues quickly realized that via Zoom, they had to teach different kinds of content, and less than they would try to convey in a class session. So they broke up their courses into smaller chunks and exercises, and began to use the interactive and communication utilities online to make discussion and problem-solving the focus of class sessions. Overnight, large numbers of faculty members discovered the virtues of “flipping” their classes (with lectures taped for student viewing at any time, “asynchronously,” and active-learning-focused classes live, or “synchronous”). From the student perspective, the direct engagement on Zoom forced them really to engage, and in fact, many reported that the lessened live class content translated, in the flipped, online format, into more demanding courses and more learning .

More broadly, Anand said, “active learning” had become widespread. Professors encouraged students to use the Zoom chat function to pose questions about material as it arose in a lecture or seminar discussion—and teaching assistants or fellow students could pose answers in real time. Technologically-enabled breakout sessions, organized in seconds, can force students to mingle with one another for fresh perspectives, rather than self-selecting the same cohort repeatedly. Students who prefer not to raise their hands, Smith said, were far more likely to engage using these tools. Faculty members and students could collaborate on Google documents or other shared tools, enabling what Anand calls “simultaneous multi-person conversations.”

In some cases, he quickly acknowledged, teachers “don’t need technology” to effect such active engagement—but now they know how to use it when they want to. (Those who do, of course, know that even as they speak, their multitasking students might be conducting a chat. But, on the other hand, students have long emailed and scrolled through websites during in-person classes; the chat exchanges may have the virtue of focusing their split attention on the course material.)

And the technology does enable classes to import other faculty experts, alumni, or speakers from around the world—all without the bother and expense of a subway ride or an airplane flight. Finally, Anand said, the online experiences for Harvard classes “brought to the forefront for all of us as faculty the lives of our students,” and led to widely popular innovations such as virtual office hours.

The common thread, he said, is “the ability of these technologies to bridge space and time.” And that virtue is now reciprocal. When applied in the context of virtual, non-degree courses, such as those Anand developed for Harvard Business School Online, the same tools—exercises, pop-up assessments, “cold calls,” break-out sessions, built-in tools for peer interaction—bring a new dimension of active learning to what was a much more passive experience a decade ago. The result is the holy grail of online education—what the report calls “engagement at scale”: the promise of teaching vast student cohorts without sacrificing the elements of active, participatory learning.

Those inclusive effects are important and large, and are emphasized throughout the report. Dean Long said separately, “One of the biggest takeaways for HGSE from the past two years was that there’s talent everywhere, and we actually have the tools—and the opportunity—to meet talented learners where they are and engage them in our programs. For instance, when our Ed.M. program had to go online for 2020-2021, in response to the pandemic, we decided to open a new round of admissions to that year’s online program—and we drew learners into our classrooms who might otherwise have never come to Harvard. We increased access for them, and they enriched our classroom conversations with new perspectives and experiences grounded in communities around the world.”

The task force report describes all these efforts as “reimagining the classroom,” incorporating “the best of online into residential settings and bringing a residential component to online programs. Blended experiences can offer new ways of teaching, learning, and meeting students where they are. At their fullest, they represent a fundamental shift in mindset beyond the binary alternatives of entirely in-person or entirely online offerings and learning experiences.” The advantages include livelier, more effective residential classes and more effective online ones, with the promise of including learners who cannot afford the time or expense of residential experiences. As Long put it, “We’ve seen that learning does not have to be confined in a traditional residential classroom. We’ve seen the value of community and meaningful connections, and know how powerful it’s been to give students different ways to connect with their instructors and peers and to contribute their ideas. It’s been wonderful to nurture a commitment to meeting students where they are and incorporating technologies that make learning more flexible.” Either way, the result is a focus on learning and education , not on the format of a course, the venue or where it is taught, or the mode of teaching.

Locally, there is something to celebrate here. The report acknowledges forthrightly “the current bifurcations between residential and online courses at Harvard. Consider, for instance, the minimal connections Harvard’s edX courses have with residential learning and campus dynamics.” One aim of edX was to prompt better campus teaching and learning—something the technology and large-format lecture courses proved ill-suited to achieve. But now, a decade on, the gap is closing, in ways faculty members and students both appear to be embracing. (edX courses were also found not to promote engagement among their much larger learner cohorts; the gap between enrollment and completion was vast for most courses.)

Happily, the report concludes, most of these gains can be sustained and more widely adopted through current practices, including informal conversations among teachers, formal gatherings to share pedagogical practices, instructional support, and continuing school and University investments in training, software, and classroom technology.

Enriching Content and Expanding Community

The report’s second and third pillars represent, respectively, a heavier lift and an overarching aspiration. Anand, who has lots of experience from the Business School’s online program, is a champion of what the task force calls “short-form digital content and learning experiences.” Compared to the traditional “unit of analysis for almost every Harvard residential degree program offering and online certificate offering,” the semester-long course, shorter instructional units present two opportunities., according to the report. Such “modular, impactful online learning experiences” can enrich residential, long-form (semester) classes and “meaningfully expand the impact of Harvard’s teaching beyond our physical campus.” (One beneficiary group might be Harvard alumni, who have demonstrated strong interest in maintaining connected to faculty members and academic offerings. If one imagines linking the task force recommendations with Business School dean Srikant Datar’s ambition to develop access to HBS courses, libraries, and research via recommendation tools hosted by Amazon Web Services, one sees the makings of truly lifelong learning in the not-impossibly-distant future.)

What the task force has in mind is strategy for bringing uniformity to the creation and distribution of such chunks of learning, so they can be archived, searched, and plugged into classes or online courses as needed. Such short-form contents might involve multiple media (texts, audio, video), forms (podcasts, for instance), and approaches (asynchronous/synchronous mixed classes, hybrid classes, online classes with occasional residential components), and so on.

To keep from overwhelming busy faculty members, presumably, and to make the material available to interested users, the task force sees the need for “curation, ensuring that content is discoverable, personalizing its use to learners’ needs, and making technology seamless.”

To that end, the task force sees the need for partnerships—including “services such as marketing, distribution, and translation”; incentives for faculty members to participate, especially where outreach “to learners beyond Harvard” is involved; and a new University-wide technological platform for asynchronous learning (development of which is under way).

Being in position to create and deliver such contents matters not only for Harvard’s own educational purposes, but defensively. As the report notes, amidst huge private investments in educational technology and new media, “the demand for short-form content and learning experiences from Harvard faculty has also exploded. Other educational institutions, third-party online learning platforms, training companies, and other organizations are all expressing interest in short-form content from Harvard faculty including masterclasses, executive programs, and podcasts. Serving learners and our faculty well will require leveraging this inbound interest consistently and strategically. Without a coherent Harvard strategy for enabling such activities, Harvard runs the risk of fragmenting its core teaching and learning mission, accelerating brand incoherence, and creating increased competition for our own internal efforts.”

In a broader perspective, how far might the University go in serving wider learner communities? Smith, recalling his earlier experience with edX, said he was particularly interested in “the evolution from getting our educational materials available to a larger part of the world then, to really engaging ” with such learners now. Within the task force, he was an evangelist for beginning a Harvard conversation about how the University can perceive itself participating, digitally, in a “world community.”

In that perspective, Anand said, everything Harvard has learned about teaching and education in the digital era applies: courses are not exclusively residential or online, but both; they are not exclusively long-form or short, but both; and they are driven not by course content but by learner engagement and communities. The Business School’s online courses, he said, incorporated student participation and peer engagement—but did not envision what happened next. The students sustained their relationships, online, beyond and after courses ended, assembling their own learning and “alumni” communities on social-media channels.

The vision for Harvard Global Learning 2.0, as Smith outlined it, is among the longest-range of the report recommendations.

The Challenges Ahead

The report raises, or touches on, matters of University policy and culture that will shape, or even determine, the conversation the task force has now introduced.

• Non-residential degrees. Apart from the Extension School, Harvard requires at least a year in residence for degree programs . Two exceptions have been granted: a hybrid public-health program, approved in 2014-2015; and the Graduate School of Education’s 2020-2021 M.Ed. program (its core degree), when instruction was all online. In both cases, the caliber of applicants, their learning gains, and their subsequent trajectories have proven as satisfactory as those of resident learners. A strategy of promulgating Harvard teaching much more widely will likely involve a reassessment of this policy, if only for a limited number of degrees or degree candidates.

• Outside activities. As the task force noted, many of the new enterprises and instructional channels focusing on online learning have an interest in accessing Harvard faculty members’ expertise. Whether professors wish to participate directly, or through University partnerships, “Many of these activities are restricted by Harvard’s outside activities policies, which were designed to create guidelines for when faculty can teach outside the University and include restrictions on teaching ‘courses’ outside of Harvard. As the lines between outside activities and residential obligations blur, and as organizations sometimes obfuscate the difference between a series of short-form content and long-form courses, the need for Harvard to judiciously implement existing policies while recognizing and facilitating new possibilities for Harvard’s faculty to innovate in teaching is paramount.” And in fact, among the long-term recommendations is pursuing a “faculty-led review of the University’s outside activities policies to modernize guidance for faculty eager to reach audiences beyond academia and to share their expertise through short-form and other innovative formats.” That review is being sponsored by the provost’s office.

• New conceptions of the economics of learning. The report notes that with technologically enabled learning, programs can be designed and targeted to different kinds of learners at different price points, presumably by melding personal instruction with the archived short-form course units. This has certain implications that almost anyone would endorse: for example, training an organization’s leaders in a new skill or strategy, and then introducing managers and other workers to the concepts (something that might not be economic with in-person, residential executive-education classes as the sole option.) The reach and impact are accordingly greater, but the differential pricing of these “cascading learning experiences” may feel strange, at least initially. As the report puts it:

Virtual teaching made it possible to reach people who could not physically come to Harvard because of time, policy, or financial constraints. That has significant implications for workforce learning after the pandemic. For example, although senior-most executives continue to attend traditional in-person sessions, our digital platforms now allow for many layers of managers to attend remote synchronous sessions to economize on time and cost, while large numbers of other staff benefit from entirely asynchronous materials. Combining delivery mechanisms in this way promises greater scale in learning, lower costs, and—perhaps most important—greater alignment of learnings across an organization.

Certainly it is an educational virtue that “As ‘future of learning’ strategies are being rethought everywhere, Harvard has enormous potential to address managerial and workforce reskilling needs through its faculty, online library, and state-of-art platforms.” But the University will need to be careful about how it presents the range of offerings, and the prices it charges, as it enters such markets.

• Defining the University. In the widest perspective, faculty members, as educators, want to teach people. But within the context of a research university, of course, they also want to spend a lot of their time on discovery and creating new knowledge. Increasing demands to teach learners who are not present will not be universally appealing to Harvard faculty members, and opportunities to teach nondegree learners may also be of varying interest. So the market logic of expanding outreach to these new kinds of students—no matter the gains in educating the world, or including more learners—may be at odds with some, or many, faculty members’ professional goals and motivations (and therefore conceptions about what they ought to be paid, or have the opportunity to earn under Harvard auspices).

It will be interesting to see whether the conversation spurred by the task force report proceeds along similar paths within, say, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the home to the liberal arts, and the professional schools. Will there be differences among the humanities faculty and those in engineering and applied sciences, whose HarvardX courses, for example, have attracted very different kinds of followings?

There is plenty to discuss. The task force has taken the experience of the pandemic and used it as a fulcrum to prompt a high-profile, and perhaps high-stakes, conversation—if the faculties are willing to engage. As the introduction to the report notes, “Our lessons draw from our residential teaching experiences, accumulated over 375 years, along with the past decade of online learning experiences.” Indeed they do. Let the conversation begin.

Read a Harvard Gazette Q&A with Bharat Anand, Bridget Terry Long, and Michael Smith here.

Read the task force report here.

You might also like

Faculty Senate Debate Continued

Harvard professors highlight governance concerns.

When to Arrest Protesters

Should civil disobedience merit a police response?

Crimson Cricket?

Taking a Harvard swing at a blossoming sport

Most popular

The Deadliest War

Drew Faust speaks on how the Civil War’s astounding death toll reshaped American society.

Michelle Yeoh’s Three Tips for Success