2.4 Developing a Hypothesis

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis it is imporant to distinguish betwee a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition. He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

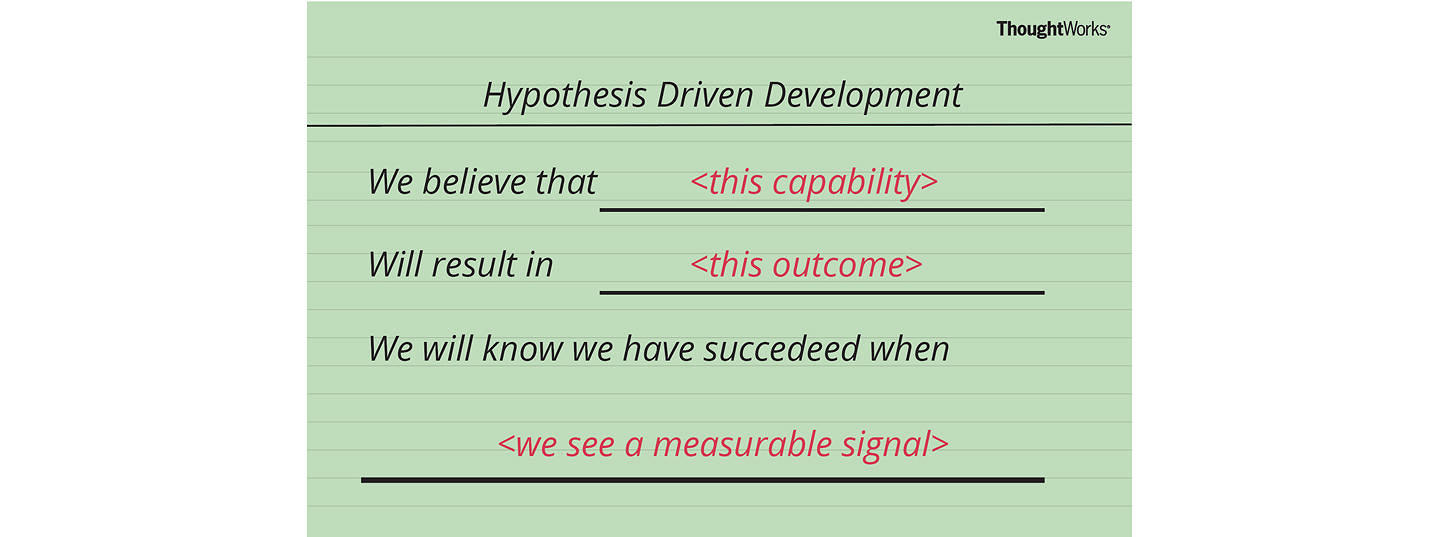

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observation before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [1] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

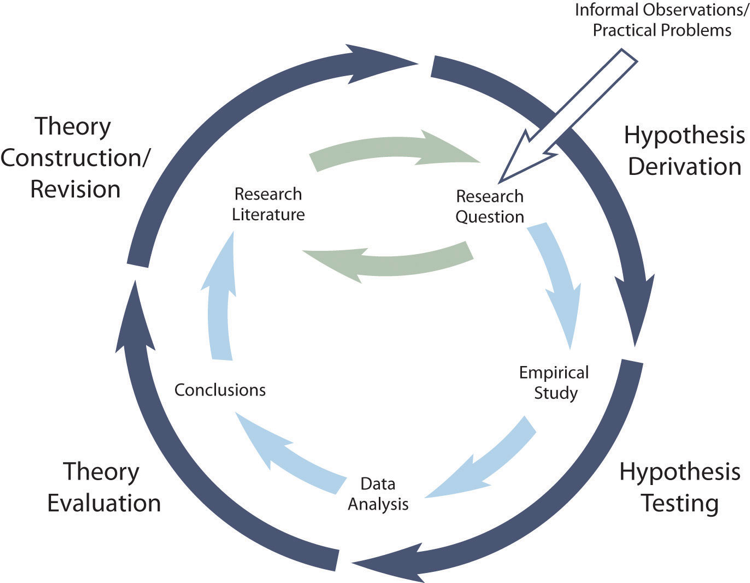

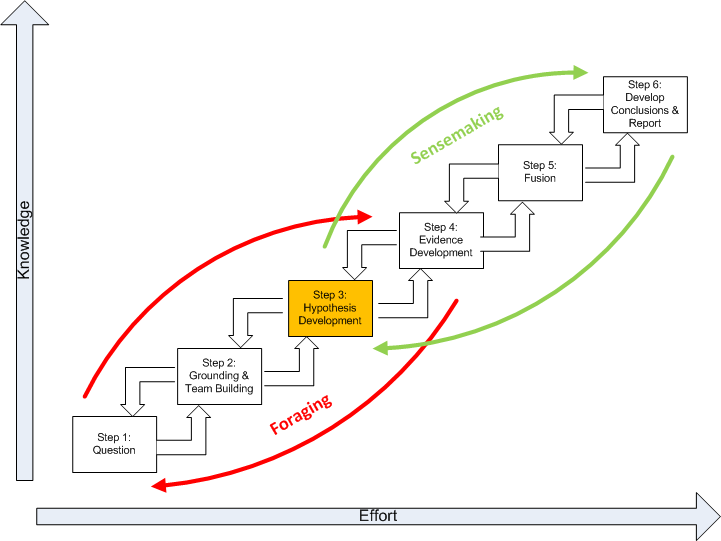

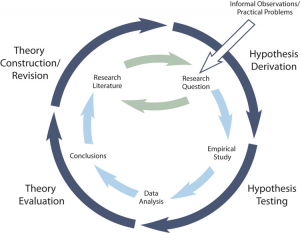

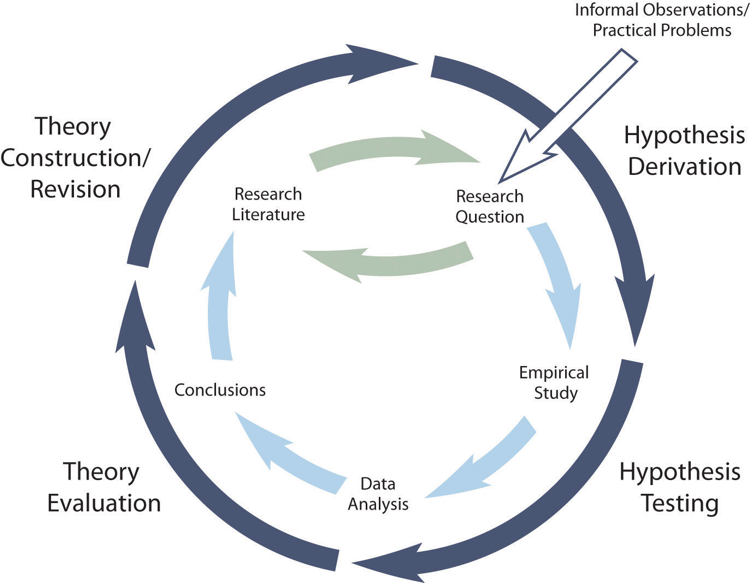

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). A researcher begins with a set of phenomena and either constructs a theory to explain or interpret them or chooses an existing theory to work with. He or she then makes a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researcher then conducts an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, he or she reevaluates the theory in light of the new results and revises it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researcher can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.2 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

Figure 2.2 Hypothetico-Deductive Method Combined With the General Model of Scientific Research in Psychology Together they form a model of theoretically motivated research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [2] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans (Zajonc & Sales, 1966) [3] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that really it does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

Key Takeaways

- A theory is broad in nature and explains larger bodies of data. A hypothesis is more specific and makes a prediction about the outcome of a particular study.

- Working with theories is not “icing on the cake.” It is a basic ingredient of psychological research.

- Like other scientists, psychologists use the hypothetico-deductive method. They construct theories to explain or interpret phenomena (or work with existing theories), derive hypotheses from their theories, test the hypotheses, and then reevaluate the theories in light of the new results.

- Practice: Find a recent empirical research report in a professional journal. Read the introduction and highlight in different colors descriptions of theories and hypotheses.

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Developing a Hypothesis

Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis.

- Discover how theories are used to generate hypotheses and how the results of studies can be used to further inform theories.

- Understand the characteristics of a good hypothesis.

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis, it is important to distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s theory of social facilitation and social inhibition (1965) [1] . He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpracticed tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term theory has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis , on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory but some hypotheses are a-theoretical and only after a set of observations have been made, is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and they explain larger bodies of data. So if our research question is really original then we may need to collect some data and make some observations before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “ If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991) [2] . Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers begin with a set of phenomena and either construct a theory to explain or interpret them or choose an existing theory to work with. They then make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary. This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 2.3 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task. To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc, Heingartner, & Herman, 1969) [3] . The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans [Zajonc & Sales, 1966] [4] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theory. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

To use theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it lends legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviors and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis. First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable . We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and if you’ll recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false. Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning which involves using specific observations or research findings to form a more general hypothesis. Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we don’t set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong, to show that it really does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

- Zajonc, R. B. (1965). Social facilitation. Science, 149 , 269–274 ↵

- Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 195–202. ↵

- Zajonc, R. B., Heingartner, A., & Herman, E. M. (1969). Social enhancement and impairment of performance in the cockroach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13 , 83–92. ↵

- Zajonc, R.B. & Sales, S.M. (1966). Social facilitation of dominant and subordinate responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 2 , 160-168. ↵

A coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena.

A specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate.

A cyclical process of theory development, starting with an observed phenomenon, then developing or using a theory to make a specific prediction of what should happen if that theory is correct, testing that prediction, refining the theory in light of the findings, and using that refined theory to develop new hypotheses, and so on.

The ability to test the hypothesis using the methods of science and the possibility to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false.

Developing a Hypothesis Copyright © by Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Hypothesis n., plural: hypotheses [/haɪˈpɑːθəsɪs/] Definition: Testable scientific prediction

Table of Contents

What Is Hypothesis?

A scientific hypothesis is a foundational element of the scientific method . It’s a testable statement proposing a potential explanation for natural phenomena. The term hypothesis means “little theory” . A hypothesis is a short statement that can be tested and gives a possible reason for a phenomenon or a possible link between two variables . In the setting of scientific research, a hypothesis is a tentative explanation or statement that can be proven wrong and is used to guide experiments and empirical research.

It is an important part of the scientific method because it gives a basis for planning tests, gathering data, and judging evidence to see if it is true and could help us understand how natural things work. Several hypotheses can be tested in the real world, and the results of careful and systematic observation and analysis can be used to support, reject, or improve them.

Researchers and scientists often use the word hypothesis to refer to this educated guess . These hypotheses are firmly established based on scientific principles and the rigorous testing of new technology and experiments .

For example, in astrophysics, the Big Bang Theory is a working hypothesis that explains the origins of the universe and considers it as a natural phenomenon. It is among the most prominent scientific hypotheses in the field.

“The scientific method: steps, terms, and examples” by Scishow:

Biology definition: A hypothesis is a supposition or tentative explanation for (a group of) phenomena, (a set of) facts, or a scientific inquiry that may be tested, verified or answered by further investigation or methodological experiment. It is like a scientific guess . It’s an idea or prediction that scientists make before they do experiments. They use it to guess what might happen and then test it to see if they were right. It’s like a smart guess that helps them learn new things. A scientific hypothesis that has been verified through scientific experiment and research may well be considered a scientific theory .

Etymology: The word “hypothesis” comes from the Greek word “hupothesis,” which means “a basis” or “a supposition.” It combines “hupo” (under) and “thesis” (placing). Synonym: proposition; assumption; conjecture; postulate Compare: theory See also: null hypothesis

Characteristics Of Hypothesis

A useful hypothesis must have the following qualities:

- It should never be written as a question.

- You should be able to test it in the real world to see if it’s right or wrong.

- It needs to be clear and exact.

- It should list the factors that will be used to figure out the relationship.

- It should only talk about one thing. You can make a theory in either a descriptive or form of relationship.

- It shouldn’t go against any natural rule that everyone knows is true. Verification will be done well with the tools and methods that are available.

- It should be written in as simple a way as possible so that everyone can understand it.

- It must explain what happened to make an answer necessary.

- It should be testable in a fair amount of time.

- It shouldn’t say different things.

Sources Of Hypothesis

Sources of hypothesis are:

- Patterns of similarity between the phenomenon under investigation and existing hypotheses.

- Insights derived from prior research, concurrent observations, and insights from opposing perspectives.

- The formulations are derived from accepted scientific theories and proposed by researchers.

- In research, it’s essential to consider hypothesis as different subject areas may require various hypotheses (plural form of hypothesis). Researchers also establish a significance level to determine the strength of evidence supporting a hypothesis.

- Individual cognitive processes also contribute to the formation of hypotheses.

One hypothesis is a tentative explanation for an observation or phenomenon. It is based on prior knowledge and understanding of the world, and it can be tested by gathering and analyzing data. Observed facts are the data that are collected to test a hypothesis. They can support or refute the hypothesis.

For example, the hypothesis that “eating more fruits and vegetables will improve your health” can be tested by gathering data on the health of people who eat different amounts of fruits and vegetables. If the people who eat more fruits and vegetables are healthier than those who eat less fruits and vegetables, then the hypothesis is supported.

Hypotheses are essential for scientific inquiry. They help scientists to focus their research, to design experiments, and to interpret their results. They are also essential for the development of scientific theories.

Types Of Hypothesis

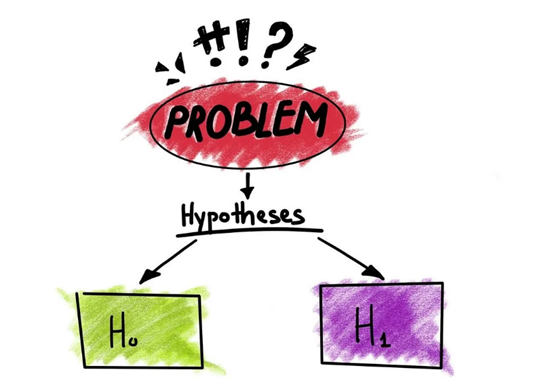

In research, you typically encounter two types of hypothesis: the alternative hypothesis (which proposes a relationship between variables) and the null hypothesis (which suggests no relationship).

Simple Hypothesis

It illustrates the association between one dependent variable and one independent variable. For instance, if you consume more vegetables, you will lose weight more quickly. Here, increasing vegetable consumption is the independent variable, while weight loss is the dependent variable.

Complex Hypothesis

It exhibits the relationship between at least two dependent variables and at least two independent variables. Eating more vegetables and fruits results in weight loss, radiant skin, and a decreased risk of numerous diseases, including heart disease.

Directional Hypothesis

It shows that a researcher wants to reach a certain goal. The way the factors are related can also tell us about their nature. For example, four-year-old children who eat well over a time of five years have a higher IQ than children who don’t eat well. This shows what happened and how it happened.

Non-directional Hypothesis

When there is no theory involved, it is used. It is a statement that there is a connection between two variables, but it doesn’t say what that relationship is or which way it goes.

Null Hypothesis

It says something that goes against the theory. It’s a statement that says something is not true, and there is no link between the independent and dependent factors. “H 0 ” represents the null hypothesis.

Associative and Causal Hypothesis

When a change in one variable causes a change in the other variable, this is called the associative hypothesis . The causal hypothesis, on the other hand, says that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between two or more factors.

Examples Of Hypothesis

Examples of simple hypotheses:

- Students who consume breakfast before taking a math test will have a better overall performance than students who do not consume breakfast.

- Students who experience test anxiety before an English examination will get lower scores than students who do not experience test anxiety.

- Motorists who talk on the phone while driving will be more likely to make errors on a driving course than those who do not talk on the phone, is a statement that suggests that drivers who talk on the phone while driving are more likely to make mistakes.

Examples of a complex hypothesis:

- Individuals who consume a lot of sugar and don’t get much exercise are at an increased risk of developing depression.

- Younger people who are routinely exposed to green, outdoor areas have better subjective well-being than older adults who have limited exposure to green spaces, according to a new study.

- Increased levels of air pollution led to higher rates of respiratory illnesses, which in turn resulted in increased costs for healthcare for the affected communities.

Examples of Directional Hypothesis:

- The crop yield will go up a lot if the amount of fertilizer is increased.

- Patients who have surgery and are exposed to more stress will need more time to get better.

- Increasing the frequency of brand advertising on social media will lead to a significant increase in brand awareness among the target audience.

Examples of Non-Directional Hypothesis (or Two-Tailed Hypothesis):

- The test scores of two groups of students are very different from each other.

- There is a link between gender and being happy at work.

- There is a correlation between the amount of caffeine an individual consumes and the speed with which they react.

Examples of a null hypothesis:

- Children who receive a new reading intervention will have scores that are different than students who do not receive the intervention.

- The results of a memory recall test will not reveal any significant gap in performance between children and adults.

- There is not a significant relationship between the number of hours spent playing video games and academic performance.

Examples of Associative Hypothesis:

- There is a link between how many hours you spend studying and how well you do in school.

- Drinking sugary drinks is bad for your health as a whole.

- There is an association between socioeconomic status and access to quality healthcare services in urban neighborhoods.

Functions Of Hypothesis

The research issue can be understood better with the help of a hypothesis, which is why developing one is crucial. The following are some of the specific roles that a hypothesis plays: (Rashid, Apr 20, 2022)

- A hypothesis gives a study a point of concentration. It enlightens us as to the specific characteristics of a study subject we need to look into.

- It instructs us on what data to acquire as well as what data we should not collect, giving the study a focal point .

- The development of a hypothesis improves objectivity since it enables the establishment of a focal point.

- A hypothesis makes it possible for us to contribute to the development of the theory. Because of this, we are in a position to definitively determine what is true and what is untrue .

How will Hypothesis help in the Scientific Method?

- The scientific method begins with observation and inquiry about the natural world when formulating research questions. Researchers can refine their observations and queries into specific, testable research questions with the aid of hypothesis. They provide an investigation with a focused starting point.

- Hypothesis generate specific predictions regarding the expected outcomes of experiments or observations. These forecasts are founded on the researcher’s current knowledge of the subject. They elucidate what researchers anticipate observing if the hypothesis is true.

- Hypothesis direct the design of experiments and data collection techniques. Researchers can use them to determine which variables to measure or manipulate, which data to obtain, and how to conduct systematic and controlled research.

- Following the formulation of a hypothesis and the design of an experiment, researchers collect data through observation, measurement, or experimentation. The collected data is used to verify the hypothesis’s predictions.

- Hypothesis establish the criteria for evaluating experiment results. The observed data are compared to the predictions generated by the hypothesis. This analysis helps determine whether empirical evidence supports or refutes the hypothesis.

- The results of experiments or observations are used to derive conclusions regarding the hypothesis. If the data support the predictions, then the hypothesis is supported. If this is not the case, the hypothesis may be revised or rejected, leading to the formulation of new queries and hypothesis.

- The scientific approach is iterative, resulting in new hypothesis and research issues from previous trials. This cycle of hypothesis generation, testing, and refining drives scientific progress.

Importance Of Hypothesis

- Hypothesis are testable statements that enable scientists to determine if their predictions are accurate. This assessment is essential to the scientific method, which is based on empirical evidence.

- Hypothesis serve as the foundation for designing experiments or data collection techniques. They can be used by researchers to develop protocols and procedures that will produce meaningful results.

- Hypothesis hold scientists accountable for their assertions. They establish expectations for what the research should reveal and enable others to assess the validity of the findings.

- Hypothesis aid in identifying the most important variables of a study. The variables can then be measured, manipulated, or analyzed to determine their relationships.

- Hypothesis assist researchers in allocating their resources efficiently. They ensure that time, money, and effort are spent investigating specific concerns, as opposed to exploring random concepts.

- Testing hypothesis contribute to the scientific body of knowledge. Whether or not a hypothesis is supported, the results contribute to our understanding of a phenomenon.

- Hypothesis can result in the creation of theories. When supported by substantive evidence, hypothesis can serve as the foundation for larger theoretical frameworks that explain complex phenomena.

- Beyond scientific research, hypothesis play a role in the solution of problems in a variety of domains. They enable professionals to make educated assumptions about the causes of problems and to devise solutions.

Research Hypotheses: Did you know that a hypothesis refers to an educated guess or prediction about the outcome of a research study?

It’s like a roadmap guiding researchers towards their destination of knowledge. Just like a compass points north, a well-crafted hypothesis points the way to valuable discoveries in the world of science and inquiry.

Choose the best answer.

Send Your Results (Optional)

Further Reading

- RNA-DNA World Hypothesis

- BYJU’S. (2023). Hypothesis. Retrieved 01 Septermber 2023, from https://byjus.com/physics/hypothesis/#sources-of-hypothesis

- Collegedunia. (2023). Hypothesis. Retrieved 1 September 2023, from https://collegedunia.com/exams/hypothesis-science-articleid-7026#d

- Hussain, D. J. (2022). Hypothesis. Retrieved 01 September 2023, from https://mmhapu.ac.in/doc/eContent/Management/JamesHusain/Research%20Hypothesis%20-Meaning,%20Nature%20&%20Importance-Characteristics%20of%20Good%20%20Hypothesis%20Sem2.pdf

- Media, D. (2023). Hypothesis in the Scientific Method. Retrieved 01 September 2023, from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-hypothesis-2795239#toc-hypotheses-examples

- Rashid, M. H. A. (Apr 20, 2022). Research Methodology. Retrieved 01 September 2023, from https://limbd.org/hypothesis-definitions-functions-characteristics-types-errors-the-process-of-testing-a-hypothesis-hypotheses-in-qualitative-research/#:~:text=Functions%20of%20a%20Hypothesis%3A&text=Specifically%2C%20a%20hypothesis%20serves%20the,providing%20focus%20to%20the%20study.

©BiologyOnline.com. Content provided and moderated by Biology Online Editors.

Last updated on September 8th, 2023

You will also like...

Gene Action – Operon Hypothesis

Water in Plants

Growth and Plant Hormones

Sigmund Freud and Carl Gustav Jung

Population Growth and Survivorship

Related articles....

RNA-DNA World Hypothesis?

On Mate Selection Evolution: Are intelligent males more attractive?

Actions of Caffeine in the Brain with Special Reference to Factors That Contribute to Its Widespread Use

Dead Man Walking

Research Hypothesis In Psychology: Types, & Examples

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset. It is a key component of the scientific method .

Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding

Some key points about hypotheses:

- A hypothesis expresses an expected pattern or relationship. It connects the variables under investigation.

- It is stated in clear, precise terms before any data collection or analysis occurs. This makes the hypothesis testable.

- A hypothesis must be falsifiable. It should be possible, even if unlikely in practice, to collect data that disconfirms rather than supports the hypothesis.

- Hypotheses guide research. Scientists design studies to explicitly evaluate hypotheses about how nature works.

- For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

- Hypotheses are informed by background knowledge and observation, but go beyond what is already known to propose an explanation of how or why something occurs.

Predictions typically arise from a thorough knowledge of the research literature, curiosity about real-world problems or implications, and integrating this to advance theory. They build on existing literature while providing new insight.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative hypothesis.

The research hypothesis is often called the alternative or experimental hypothesis in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable affects the other).

A hypothesis is a testable statement or prediction about the relationship between two or more variables. It is a key component of the scientific method. Some key points about hypotheses:

- Important hypotheses lead to predictions that can be tested empirically. The evidence can then confirm or disprove the testable predictions.

In summary, a hypothesis is a precise, testable statement of what researchers expect to happen in a study and why. Hypotheses connect theory to data and guide the research process towards expanding scientific understanding.

An experimental hypothesis predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and are significant in supporting the theory being investigated.

The alternative hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference without specifying its nature. It’s what researchers aim to support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable does not affect the other). There will be no changes in the dependent variable due to manipulating the independent variable.

It states results are due to chance and are not significant in supporting the idea being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing no effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast to the research hypothesis in scientific inquiry. It establishes a baseline for statistical testing, promoting objectivity by initiating research from a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining the likelihood of observed results if no true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring that research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific studies, enhancing the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes.

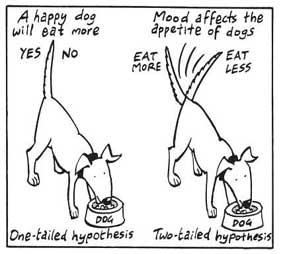

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, predicts that there is a difference or relationship between two variables but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or effect will occur without predicting which group will have higher or lower values.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place. (i.e., greater, smaller, less, more)

It specifies whether one variable is greater, lesser, or different from another, rather than just indicating that there’s a difference without specifying its nature.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” is a directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper , is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory or hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be proven wrong.

It means that there should exist some potential evidence or experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist for a theory, it only takes one counter observation to falsify it. For example, the hypothesis that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan.

For Popper, science should attempt to disprove a theory rather than attempt to continually provide evidence to support a research hypothesis.

Can a Hypothesis be Proven?

Hypotheses make probabilistic predictions. They state the expected outcome if a particular relationship exists. However, a study result supporting a hypothesis does not definitively prove it is true.

All studies have limitations. There may be unknown confounding factors or issues that limit the certainty of conclusions. Additional studies may yield different results.

In science, hypotheses can realistically only be supported with some degree of confidence, not proven. The process of science is to incrementally accumulate evidence for and against hypothesized relationships in an ongoing pursuit of better models and explanations that best fit the empirical data. But hypotheses remain open to revision and rejection if that is where the evidence leads.

- Disproving a hypothesis is definitive. Solid disconfirmatory evidence will falsify a hypothesis and require altering or discarding it based on the evidence.

- However, confirming evidence is always open to revision. Other explanations may account for the same results, and additional or contradictory evidence may emerge over time.

We can never 100% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see if we can disprove, or reject the null hypothesis.

If we reject the null hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but does support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of the results, an alternative hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but it can never be proven to be correct. We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist which could refute a theory.

How to Write a Hypothesis

- Identify variables . The researcher manipulates the independent variable and the dependent variable is the measured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated . Operationalization of a hypothesis refers to the process of making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about to study aggression, you might count the number of punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your prediction . If there is evidence in the literature to support a specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings in the literature regarding the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable : Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language . A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated using clear and straightforward language, ensuring it’s easily understood and testable.

Consider a hypothesis many teachers might subscribe to: students work better on Monday morning than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard of work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving the same group of students a lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon and then measuring their immediate recall of the material covered in each session, we would end up with the following:

- The alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more information on a Monday morning than on a Friday afternoon.

- The null hypothesis states that there will be no significant difference in the amount recalled on a Monday morning compared to a Friday afternoon. Any difference will be due to chance or confounding factors.

More Examples

- Memory : Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a list than those who studied in silence.

- Social Psychology : Individuals who frequently engage in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those who use it infrequently.

- Developmental Psychology : Children who engage in regular imaginative play have better problem-solving skills than those who don’t.

- Clinical Psychology : Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be more effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology : Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will have shorter attention spans on focused tasks than those who single-task.

- Health Psychology : Patients who practice mindfulness meditation will experience lower levels of chronic pain compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology : Employees in open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those in private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology : Rats rewarded with food after pressing a lever will press it more frequently than rats who receive no reward.

Related Articles

Research Methodology

Qualitative Data Coding

What Is a Focus Group?

Cross-Cultural Research Methodology In Psychology

What Is Internal Validity In Research?

Research Methodology , Statistics

What Is Face Validity In Research? Importance & How To Measure

Criterion Validity: Definition & Examples

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.34(45); 2019 Nov 25

Scientific Hypotheses: Writing, Promoting, and Predicting Implications

Armen yuri gasparyan.

1 Departments of Rheumatology and Research and Development, Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust (Teaching Trust of the University of Birmingham, UK), Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands, UK.

Lilit Ayvazyan

2 Department of Medical Chemistry, Yerevan State Medical University, Yerevan, Armenia.

Ulzhan Mukanova

3 Department of Surgical Disciplines, South Kazakhstan Medical Academy, Shymkent, Kazakhstan.

Marlen Yessirkepov

4 Department of Biology and Biochemistry, South Kazakhstan Medical Academy, Shymkent, Kazakhstan.

George D. Kitas

5 Arthritis Research UK Epidemiology Unit, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK.

Scientific hypotheses are essential for progress in rapidly developing academic disciplines. Proposing new ideas and hypotheses require thorough analyses of evidence-based data and predictions of the implications. One of the main concerns relates to the ethical implications of the generated hypotheses. The authors may need to outline potential benefits and limitations of their suggestions and target widely visible publication outlets to ignite discussion by experts and start testing the hypotheses. Not many publication outlets are currently welcoming hypotheses and unconventional ideas that may open gates to criticism and conservative remarks. A few scholarly journals guide the authors on how to structure hypotheses. Reflecting on general and specific issues around the subject matter is often recommended for drafting a well-structured hypothesis article. An analysis of influential hypotheses, presented in this article, particularly Strachan's hygiene hypothesis with global implications in the field of immunology and allergy, points to the need for properly interpreting and testing new suggestions. Envisaging the ethical implications of the hypotheses should be considered both by authors and journal editors during the writing and publishing process.

INTRODUCTION

We live in times of digitization that radically changes scientific research, reporting, and publishing strategies. Researchers all over the world are overwhelmed with processing large volumes of information and searching through numerous online platforms, all of which make the whole process of scholarly analysis and synthesis complex and sophisticated.

Current research activities are diversifying to combine scientific observations with analysis of facts recorded by scholars from various professional backgrounds. 1 Citation analyses and networking on social media are also becoming essential for shaping research and publishing strategies globally. 2 Learning specifics of increasingly interdisciplinary research studies and acquiring information facilitation skills aid researchers in formulating innovative ideas and predicting developments in interrelated scientific fields.

Arguably, researchers are currently offered more opportunities than in the past for generating new ideas by performing their routine laboratory activities, observing individual cases and unusual developments, and critically analyzing published scientific facts. What they need at the start of their research is to formulate a scientific hypothesis that revisits conventional theories, real-world processes, and related evidence to propose new studies and test ideas in an ethical way. 3 Such a hypothesis can be of most benefit if published in an ethical journal with wide visibility and exposure to relevant online databases and promotion platforms.

Although hypotheses are crucially important for the scientific progress, only few highly skilled researchers formulate and eventually publish their innovative ideas per se . Understandably, in an increasingly competitive research environment, most authors would prefer to prioritize their ideas by discussing and conducting tests in their own laboratories or clinical departments, and publishing research reports afterwards. However, there are instances when simple observations and research studies in a single center are not capable of explaining and testing new groundbreaking ideas. Formulating hypothesis articles first and calling for multicenter and interdisciplinary research can be a solution in such instances, potentially launching influential scientific directions, if not academic disciplines.

The aim of this article is to overview the importance and implications of infrequently published scientific hypotheses that may open new avenues of thinking and research.

Despite the seemingly established views on innovative ideas and hypotheses as essential research tools, no structured definition exists to tag the term and systematically track related articles. In 1973, the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) of the U.S. National Library of Medicine introduced “Research Design” as a structured keyword that referred to the importance of collecting data and properly testing hypotheses, and indirectly linked the term to ethics, methods and standards, among many other subheadings.

One of the experts in the field defines “hypothesis” as a well-argued analysis of available evidence to provide a realistic (scientific) explanation of existing facts, fill gaps in public understanding of sophisticated processes, and propose a new theory or a test. 4 A hypothesis can be proven wrong partially or entirely. However, even such an erroneous hypothesis may influence progress in science by initiating professional debates that help generate more realistic ideas. The main ethical requirement for hypothesis authors is to be honest about the limitations of their suggestions. 5

EXAMPLES OF INFLUENTIAL SCIENTIFIC HYPOTHESES

Daily routine in a research laboratory may lead to groundbreaking discoveries provided the daily accounts are comprehensively analyzed and reproduced by peers. The discovery of penicillin by Sir Alexander Fleming (1928) can be viewed as a prime example of such discoveries that introduced therapies to treat staphylococcal and streptococcal infections and modulate blood coagulation. 6 , 7 Penicillin got worldwide recognition due to the inventor's seminal works published by highly prestigious and widely visible British journals, effective ‘real-world’ antibiotic therapy of pneumonia and wounds during World War II, and euphoric media coverage. 8 In 1945, Fleming, Florey and Chain got a much deserved Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery that led to the mass production of the wonder drug in the U.S. and ‘real-world practice’ that tested the use of penicillin. What remained globally unnoticed is that Zinaida Yermolyeva, the outstanding Soviet microbiologist, created the Soviet penicillin, which turned out to be more effective than the Anglo-American penicillin and entered mass production in 1943; that year marked the turning of the tide of the Great Patriotic War. 9 One of the reasons of the widely unnoticed discovery of Zinaida Yermolyeva is that her works were published exclusively by local Russian (Soviet) journals.

The past decades have been marked by an unprecedented growth of multicenter and global research studies involving hundreds and thousands of human subjects. This trend is shaped by an increasing number of reports on clinical trials and large cohort studies that create a strong evidence base for practice recommendations. Mega-studies may help generate and test large-scale hypotheses aiming to solve health issues globally. Properly designed epidemiological studies, for example, may introduce clarity to the hygiene hypothesis that was originally proposed by David Strachan in 1989. 10 David Strachan studied the epidemiology of hay fever in a cohort of 17,414 British children and concluded that declining family size and improved personal hygiene had reduced the chances of cross infections in families, resulting in epidemics of atopic disease in post-industrial Britain. Over the past four decades, several related hypotheses have been proposed to expand the potential role of symbiotic microorganisms and parasites in the development of human physiological immune responses early in life and protection from allergic and autoimmune diseases later on. 11 , 12 Given the popularity and the scientific importance of the hygiene hypothesis, it was introduced as a MeSH term in 2012. 13

Hypotheses can be proposed based on an analysis of recorded historic events that resulted in mass migrations and spreading of certain genetic diseases. As a prime example, familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), the prototype periodic fever syndrome, is believed to spread from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean region and all over Europe due to migrations and religious prosecutions millennia ago. 14 Genetic mutations spearing mild clinical forms of FMF are hypothesized to emerge and persist in the Mediterranean region as protective factors against more serious infectious diseases, particularly tuberculosis, historically common in that part of the world. 15 The speculations over the advantages of carrying the MEditerranean FeVer (MEFV) gene are further strengthened by recorded low mortality rates from tuberculosis among FMF patients of different nationalities living in Tunisia in the first half of the 20th century. 16

Diagnostic hypotheses shedding light on peculiarities of diseases throughout the history of mankind can be formulated using artefacts, particularly historic paintings. 17 Such paintings may reveal joint deformities and disfigurements due to rheumatic diseases in individual subjects. A series of paintings with similar signs of pathological conditions interpreted in a historic context may uncover mysteries of epidemics of certain diseases, which is the case with Ruben's paintings depicting signs of rheumatic hands and making some doctors to believe that rheumatoid arthritis was common in Europe in the 16th and 17th century. 18

WRITING SCIENTIFIC HYPOTHESES

There are author instructions of a few journals that specifically guide how to structure, format, and make submissions categorized as hypotheses attractive. One of the examples is presented by Med Hypotheses , the flagship journal in its field with more than four decades of publishing and influencing hypothesis authors globally. However, such guidance is not based on widely discussed, implemented, and approved reporting standards, which are becoming mandatory for all scholarly journals.

Generating new ideas and scientific hypotheses is a sophisticated task since not all researchers and authors are skilled to plan, conduct, and interpret various research studies. Some experience with formulating focused research questions and strong working hypotheses of original research studies is definitely helpful for advancing critical appraisal skills. However, aspiring authors of scientific hypotheses may need something different, which is more related to discerning scientific facts, pooling homogenous data from primary research works, and synthesizing new information in a systematic way by analyzing similar sets of articles. To some extent, this activity is reminiscent of writing narrative and systematic reviews. As in the case of reviews, scientific hypotheses need to be formulated on the basis of comprehensive search strategies to retrieve all available studies on the topics of interest and then synthesize new information selectively referring to the most relevant items. One of the main differences between scientific hypothesis and review articles relates to the volume of supportive literature sources ( Table 1 ). In fact, hypothesis is usually formulated by referring to a few scientific facts or compelling evidence derived from a handful of literature sources. 19 By contrast, reviews require analyses of a large number of published documents retrieved from several well-organized and evidence-based databases in accordance with predefined search strategies. 20 , 21 , 22

The format of hypotheses, especially the implications part, may vary widely across disciplines. Clinicians may limit their suggestions to the clinical manifestations of diseases, outcomes, and management strategies. Basic and laboratory scientists analysing genetic, molecular, and biochemical mechanisms may need to view beyond the frames of their narrow fields and predict social and population-based implications of the proposed ideas. 23

Advanced writing skills are essential for presenting an interesting theoretical article which appeals to the global readership. Merely listing opposing facts and ideas, without proper interpretation and analysis, may distract the experienced readers. The essence of a great hypothesis is a story behind the scientific facts and evidence-based data.

ETHICAL IMPLICATIONS

The authors of hypotheses substantiate their arguments by referring to and discerning rational points from published articles that might be overlooked by others. Their arguments may contradict the established theories and practices, and pose global ethical issues, particularly when more or less efficient medical technologies and public health interventions are devalued. The ethical issues may arise primarily because of the careless references to articles with low priorities, inadequate and apparently unethical methodologies, and concealed reporting of negative results. 24 , 25

Misinterpretation and misunderstanding of the published ideas and scientific hypotheses may complicate the issue further. For example, Alexander Fleming, whose innovative ideas of penicillin use to kill susceptible bacteria saved millions of lives, warned of the consequences of uncontrolled prescription of the drug. The issue of antibiotic resistance had emerged within the first ten years of penicillin use on a global scale due to the overprescription that affected the efficacy of antibiotic therapies, with undesirable consequences for millions. 26

The misunderstanding of the hygiene hypothesis that primarily aimed to shed light on the role of the microbiome in allergic and autoimmune diseases resulted in decline of public confidence in hygiene with dire societal implications, forcing some experts to abandon the original idea. 27 , 28 Although that hypothesis is unrelated to the issue of vaccinations, the public misunderstanding has resulted in decline of vaccinations at a time of upsurge of old and new infections.

A number of ethical issues are posed by the denial of the viral (human immunodeficiency viruses; HIV) hypothesis of acquired Immune deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) by Peter Duesberg, who overviewed the links between illicit recreational drugs and antiretroviral therapies with AIDS and refuted the etiological role of HIV. 29 That controversial hypothesis was rejected by several journals, but was eventually published without external peer review at Med Hypotheses in 2010. The publication itself raised concerns of the unconventional editorial policy of the journal, causing major perturbations and more scrutinized publishing policies by journals processing hypotheses.

WHERE TO PUBLISH HYPOTHESES

Although scientific authors are currently well informed and equipped with search tools to draft evidence-based hypotheses, there are still limited quality publication outlets calling for related articles. The journal editors may be hesitant to publish articles that do not adhere to any research reporting guidelines and open gates for harsh criticism of unconventional and untested ideas. Occasionally, the editors opting for open-access publishing and upgrading their ethics regulations launch a section to selectively publish scientific hypotheses attractive to the experienced readers. 30 However, the absence of approved standards for this article type, particularly no mandate for outlining potential ethical implications, may lead to publication of potentially harmful ideas in an attractive format.

A suggestion of simultaneously publishing multiple or alternative hypotheses to balance the reader views and feedback is a potential solution for the mainstream scholarly journals. 31 However, that option alone is hardly applicable to emerging journals with unconventional quality checks and peer review, accumulating papers with multiple rejections by established journals.

A large group of experts view hypotheses with improbable and controversial ideas publishable after formal editorial (in-house) checks to preserve the authors' genuine ideas and avoid conservative amendments imposed by external peer reviewers. 32 That approach may be acceptable for established publishers with large teams of experienced editors. However, the same approach can lead to dire consequences if employed by nonselective start-up, open-access journals processing all types of articles and primarily accepting those with charged publication fees. 33 In fact, pseudoscientific ideas arguing Newton's and Einstein's seminal works or those denying climate change that are hardly testable have already found their niche in substandard electronic journals with soft or nonexistent peer review. 34

CITATIONS AND SOCIAL MEDIA ATTENTION

The available preliminary evidence points to the attractiveness of hypothesis articles for readers, particularly those from research-intensive countries who actively download related documents. 35 However, citations of such articles are disproportionately low. Only a small proportion of top-downloaded hypotheses (13%) in the highly prestigious Med Hypotheses receive on average 5 citations per article within a two-year window. 36

With the exception of a few historic papers, the vast majority of hypotheses attract relatively small number of citations in a long term. 36 Plausible explanations are that these articles often contain a single or only a few citable points and that suggested research studies to test hypotheses are rarely conducted and reported, limiting chances of citing and crediting authors of genuine research ideas.

A snapshot analysis of citation activity of hypothesis articles may reveal interest of the global scientific community towards their implications across various disciplines and countries. As a prime example, Strachan's hygiene hypothesis, published in 1989, 10 is still attracting numerous citations on Scopus, the largest bibliographic database. As of August 28, 2019, the number of the linked citations in the database is 3,201. Of the citing articles, 160 are cited at least 160 times ( h -index of this research topic = 160). The first three citations are recorded in 1992 and followed by a rapid annual increase in citation activity and a peak of 212 in 2015 ( Fig. 1 ). The top 5 sources of the citations are Clin Exp Allergy (n = 136), J Allergy Clin Immunol (n = 119), Allergy (n = 81), Pediatr Allergy Immunol (n = 69), and PLOS One (n = 44). The top 5 citing authors are leading experts in pediatrics and allergology Erika von Mutius (Munich, Germany, number of publications with the index citation = 30), Erika Isolauri (Turku, Finland, n = 27), Patrick G Holt (Subiaco, Australia, n = 25), David P. Strachan (London, UK, n = 23), and Bengt Björksten (Stockholm, Sweden, n = 22). The U.S. is the leading country in terms of citation activity with 809 related documents, followed by the UK (n = 494), Germany (n = 314), Australia (n = 211), and the Netherlands (n = 177). The largest proportion of citing documents are articles (n = 1,726, 54%), followed by reviews (n = 950, 29.7%), and book chapters (n = 213, 6.7%). The main subject areas of the citing items are medicine (n = 2,581, 51.7%), immunology and microbiology (n = 1,179, 23.6%), and biochemistry, genetics and molecular biology (n = 415, 8.3%).

Interestingly, a recent analysis of 111 publications related to Strachan's hygiene hypothesis, stating that the lack of exposure to infections in early life increases the risk of rhinitis, revealed a selection bias of 5,551 citations on Web of Science. 37 The articles supportive of the hypothesis were cited more than nonsupportive ones (odds ratio adjusted for study design, 2.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.6–3.1). A similar conclusion pointing to a citation bias distorting bibliometrics of hypotheses was reached by an earlier analysis of a citation network linked to the idea that β-amyloid, which is involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease, is produced by skeletal muscle of patients with inclusion body myositis. 38 The results of both studies are in line with the notion that ‘positive’ citations are more frequent in the field of biomedicine than ‘negative’ ones, and that citations to articles with proven hypotheses are too common. 39

Social media channels are playing an increasingly active role in the generation and evaluation of scientific hypotheses. In fact, publicly discussing research questions on platforms of news outlets, such as Reddit, may shape hypotheses on health-related issues of global importance, such as obesity. 40 Analyzing Twitter comments, researchers may reveal both potentially valuable ideas and unfounded claims that surround groundbreaking research ideas. 41 Social media activities, however, are unevenly distributed across different research topics, journals and countries, and these are not always objective professional reflections of the breakthroughs in science. 2 , 42

Scientific hypotheses are essential for progress in science and advances in healthcare. Innovative ideas should be based on a critical overview of related scientific facts and evidence-based data, often overlooked by others. To generate realistic hypothetical theories, the authors should comprehensively analyze the literature and suggest relevant and ethically sound design for future studies. They should also consider their hypotheses in the context of research and publication ethics norms acceptable for their target journals. The journal editors aiming to diversify their portfolio by maintaining and introducing hypotheses section are in a position to upgrade guidelines for related articles by pointing to general and specific analyses of the subject, preferred study designs to test hypotheses, and ethical implications. The latter is closely related to specifics of hypotheses. For example, editorial recommendations to outline benefits and risks of a new laboratory test or therapy may result in a more balanced article and minimize associated risks afterwards.