- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Why Publish with HGS?

- Advance Articles

- About Holocaust and Genocide Studies

- About the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Daniel Magilow Helene Sinnreich

Book Review Editors

Golan Moskowitz

About the journal

The major forum for scholarship on the Holocaust and other genocides, Holocaust and Genocide Studies is an international journal featuring research articles, interpretive essays, and book reviews in the social sciences and humanities …

Latest articles

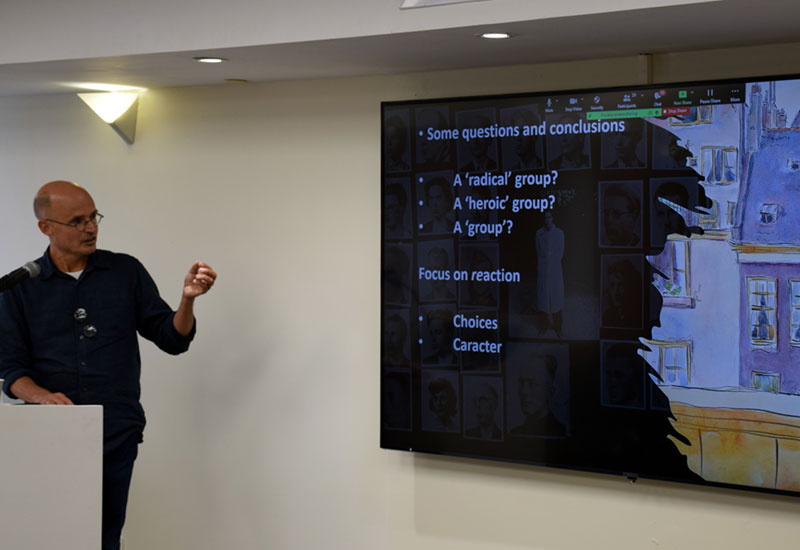

Call for Papers: “Beyond Cumulative Radicalization? A Comparative Perspective”

How and why do policies of mass violence and genocide emerge? This special issue aims to builds on and challenge an influential model developed in Holocaust Studies, that of “cumulative radicalization,” by placing that model in comparative perspective. Deadline for Submissions: July 1, 2024.

Submit your research

- The Holocaust in Ukraine

In 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the massive humanitarian crisis it unleashed has once again brought Europe’s second largest country—and one of its poorest—to the forefront of international discourse. For this virtual issue, the editors of Holocaust and Genocide Studies have selected articles produced over the past nine years that provide insights into the Holocaust in Ukraine. Read more

Postwar Justice Virtual Issue

The editors of Holocaust and Genocide Studies offer this special virtual issue on Postwar Justice to advance debate on the efficacy of the legal reckoning with Nazi criminals and their anti-Jewish crimes.

Virtual issues

Read the newest virtual issue from Holocaust and Genocide Studies :

Explore past virtual issues from Holocaust and Genocide Studies .

- Postwar Justice

- Holocaust-era American Antisemitism

- The Armenian Genocide

Published on behalf of

Email alerts

Register to receive table of contents email alerts as soon as new issues of Holocaust and Genocide Studies are published online.

Recommend to your library

Fill out our simple online form to recommend Holocaust and Genocide Studies to your library.

Recommend now

Related Titles

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1476-7937

- Print ISSN 8756-6583

- Copyright © 2024 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Holocaust

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 11, 2023 | Original: October 14, 2009

The Holocaust was the state-sponsored persecution and mass murder of millions of European Jews, Romani people, the intellectually disabled, political dissidents and homosexuals by the German Nazi regime between 1933 and 1945. The word “holocaust,” from the Greek words “holos” (whole) and “kaustos” (burned), was historically used to describe a sacrificial offering burned on an altar.

After years of Nazi rule in Germany, dictator Adolf Hitler’s “Final Solution”—now known as the Holocaust—came to fruition during World War II, with mass killing centers in concentration camps. About six million Jews and some five million others, targeted for racial, political, ideological and behavioral reasons, died in the Holocaust—more than one million of those who perished were children.

Historical Anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism in Europe did not begin with Adolf Hitler . Though use of the term itself dates only to the 1870s, there is evidence of hostility toward Jews long before the Holocaust—even as far back as the ancient world, when Roman authorities destroyed the Jewish temple in Jerusalem and forced Jews to leave Palestine .

The Enlightenment , during the 17th and 18th centuries, emphasized religious tolerance, and in the 19th century Napoleon Bonaparte and other European rulers enacted legislation that ended long-standing restrictions on Jews. Anti-Semitic feeling endured, however, in many cases taking on a racial character rather than a religious one.

Did you know? Even in the early 21st century, the legacy of the Holocaust endures. Swiss government and banking institutions have in recent years acknowledged their complicity with the Nazis and established funds to aid Holocaust survivors and other victims of human rights abuses, genocide or other catastrophes.

Hitler's Rise to Power

The roots of Adolf Hitler’s particularly virulent brand of anti-Semitism are unclear. Born in Austria in 1889, he served in the German army during World War I . Like many anti-Semites in Germany, he blamed the Jews for the country’s defeat in 1918.

Soon after World War I ended, Hitler joined the National German Workers’ Party, which became the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), known to English speakers as the Nazis. While imprisoned for treason for his role in the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, Hitler wrote the memoir and propaganda tract “ Mein Kampf ” (or “my struggle”), in which he predicted a general European war that would result in “the extermination of the Jewish race in Germany.”

Hitler was obsessed with the idea of the superiority of the “pure” German race, which he called “Aryan,” and with the need for “Lebensraum,” or living space, for that race to expand. In the decade after he was released from prison, Hitler took advantage of the weakness of his rivals to enhance his party’s status and rise from obscurity to power.

On January 30, 1933, he was named chancellor of Germany. After the death of President Paul von Hindenburg in 1934, Hitler anointed himself Fuhrer , becoming Germany’s supreme ruler.

Concentration Camps

The twin goals of racial purity and territorial expansion were the core of Hitler’s worldview, and from 1933 onward they would combine to form the driving force behind his foreign and domestic policy.

At first, the Nazis reserved their harshest persecution for political opponents such as Communists or Social Democrats. The first official concentration camp opened at Dachau (near Munich) in March 1933, and many of the first prisoners sent there were Communists.

Like the network of concentration camps that followed, becoming the killing grounds of the Holocaust, Dachau was under the control of Heinrich Himmler , head of the elite Nazi guard, the Schutzstaffel (SS) and later chief of the German police.

By July 1933, German concentration camps ( Konzentrationslager in German, or KZ) held some 27,000 people in “protective custody.” Huge Nazi rallies and symbolic acts such as the public burning of books by Jews, Communists, liberals and foreigners helped drive home the desired message of party strength and unity.

In 1933, Jews in Germany numbered around 525,000—just one percent of the total German population. During the next six years, Nazis undertook an “Aryanization” of Germany, dismissing non-Aryans from civil service, liquidating Jewish-owned businesses and stripping Jewish lawyers and doctors of their clients.

Nuremberg Laws

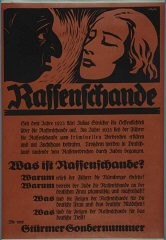

Under the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, anyone with three or four Jewish grandparents was considered a Jew, while those with two Jewish grandparents were designated Mischlinge (half-breeds).

Under the Nuremberg Laws, Jews became routine targets for stigmatization and persecution. This culminated in Kristallnacht , or the “Night of Broken Glass” in November 1938, when German synagogues were burned and windows in Jewish home and shops were smashed; some 100 Jews were killed and thousands more arrested.

From 1933 to 1939, hundreds of thousands of Jews who were able to leave Germany did, while those who remained lived in a constant state of uncertainty and fear.

HISTORY Vault: Third Reich: The Rise

Rare and never-before-seen amateur films offer a unique perspective on the rise of Nazi Germany from Germans who experienced it. How were millions of people so vulnerable to fascism?

Euthanasia Program

In September 1939, Germany invaded the western half of Poland , starting World War II . German police soon forced tens of thousands of Polish Jews from their homes and into ghettoes, giving their confiscated properties to ethnic Germans (non-Jews outside Germany who identified as German), Germans from the Reich or Polish gentiles.

Surrounded by high walls and barbed wire, the Jewish ghettoes in Poland functioned like captive city-states, governed by Jewish Councils. In addition to widespread unemployment, poverty and hunger, overpopulation and poor sanitation made the ghettoes breeding grounds for disease such as typhus.

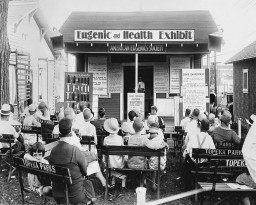

Meanwhile, beginning in the fall of 1939, Nazi officials selected around 70,000 Germans institutionalized for mental illness or physical disabilities to be gassed to death in the so-called Euthanasia Program.

After prominent German religious leaders protested, Hitler put an end to the program in August 1941, though killings of the disabled continued in secrecy, and by 1945 some 275,000 people deemed handicapped from all over Europe had been killed. In hindsight, it seems clear that the Euthanasia Program functioned as a pilot for the Holocaust.

'Final Solution'

Throughout the spring and summer of 1940, the German army expanded Hitler’s empire in Europe, conquering Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France. Beginning in 1941, Jews from all over the continent, as well as hundreds of thousands of European Romani people, were transported to Polish ghettoes.

The German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 marked a new level of brutality in warfare. Mobile killing units of Himmler’s SS called Einsatzgruppen would murder more than 500,000 Soviet Jews and others (usually by shooting) over the course of the German occupation.

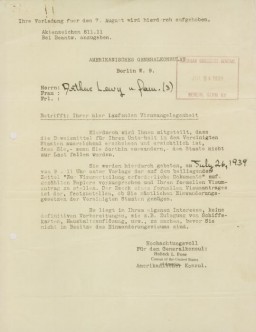

A memorandum dated July 31, 1941, from Hitler’s top commander Hermann Goering to Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the SD (the security service of the SS), referred to the need for an Endlösung ( Final Solution ) to “the Jewish question.”

Yellow Stars

Beginning in September 1941, every person designated as a Jew in German-held territory was marked with a yellow, six-pointed star, making them open targets. Tens of thousands were soon being deported to the Polish ghettoes and German-occupied cities in the USSR.

Since June 1941, experiments with mass killing methods had been ongoing at the concentration camp of Auschwitz , near Krakow, Poland. That August, 500 officials gassed 500 Soviet POWs to death with the pesticide Zyklon-B. The SS soon placed a huge order for the gas with a German pest-control firm, an ominous indicator of the coming Holocaust.

Holocaust Death Camps

Beginning in late 1941, the Germans began mass transports from the ghettoes in Poland to the concentration camps, starting with those people viewed as the least useful: the sick, old and weak and the very young.

The first mass gassings began at the camp of Belzec, near Lublin, on March 17, 1942. Five more mass killing centers were built at camps in occupied Poland, including Chelmno, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek and the largest of all, Auschwitz.

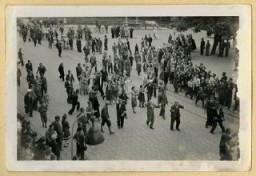

From 1942 to 1945, Jews were deported to the camps from all over Europe, including German-controlled territory as well as those countries allied with Germany. The heaviest deportations took place during the summer and fall of 1942, when more than 300,000 people were deported from the Warsaw ghetto alone.

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

Amid the deportations, disease and constant hunger, incarcerated people in the Warsaw Ghetto rose up in armed revolt.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 19-May 16, 1943, ended in the death of 7,000 Jews, with 50,000 survivors sent to extermination camps. But the resistance fighters had held off the Nazis for almost a month, and their revolt inspired revolts at camps and ghettos across German-occupied Europe.

Though the Nazis tried to keep operation of the camps secret, the scale of the killing made this virtually impossible. Eyewitnesses brought reports of Nazi atrocities in Poland to the Allied governments, who were harshly criticized after the war for their failure to respond, or to publicize news of the mass slaughter.

This lack of action was likely mostly due to the Allied focus on winning the war at hand, but was also partly a result of the general incomprehension with which news of the Holocaust was met and the denial and disbelief that such atrocities could be occurring on such a scale.

'Angel of Death'

At Auschwitz alone, more than 2 million people were murdered in a process resembling a large-scale industrial operation. A large population of Jewish and non-Jewish inmates worked in the labor camp there; though only Jews were gassed, thousands of others died of starvation or disease.

In 1943, eugenics advocate Josef Mengele arrived in Auschwitz to begin his infamous experiments on Jewish prisoners. His special area of focus was conducting medical experiments on twins , injecting them with everything from petrol to chloroform under the guise of giving them medical treatment. His actions earned him the nickname “the Angel of Death.”

Nazi Rule Ends

By the spring of 1945, German leadership was dissolving amid internal dissent, with Goering and Himmler both seeking to distance themselves from Hitler and take power.

In his last will and political testament, dictated in a German bunker that April 29, Hitler blamed the war on “International Jewry and its helpers” and urged the German leaders and people to follow “the strict observance of the racial laws and with merciless resistance against the universal poisoners of all peoples”—the Jews.

The following day, Hitler died by suicide . Germany’s formal surrender in World War II came barely a week later, on May 8, 1945.

German forces had begun evacuating many of the death camps in the fall of 1944, sending inmates under guard to march further from the advancing enemy’s front line. These so-called “death marches” continued all the way up to the German surrender, resulting in the deaths of some 250,000 to 375,000 people.

In his classic book Survival in Auschwitz , the Italian-Jewish author Primo Levi described his own state of mind, as well as that of his fellow inmates in Auschwitz on the day before Soviet troops liberated the camp in January 1945: “We lay in a world of death and phantoms. The last trace of civilization had vanished around and inside us. The work of bestial degradation, begun by the victorious Germans, had been carried to conclusion by the Germans in defeat.”

Legacy of the Holocaust

The wounds of the Holocaust—known in Hebrew as “Shoah,” or catastrophe—were slow to heal. Survivors of the camps found it nearly impossible to return home, as in many cases they had lost their entire family and been denounced by their non-Jewish neighbors. As a result, the late 1940s saw an unprecedented number of refugees, POWs and other displaced populations moving across Europe.

In an effort to punish the villains of the Holocaust, the Allies held the Nuremberg Trials of 1945-46, which brought Nazi atrocities to horrifying light. Increasing pressure on the Allied powers to create a homeland for Jewish survivors of the Holocaust would lead to a mandate for the creation of Israel in 1948.

Over the decades that followed, ordinary Germans struggled with the Holocaust’s bitter legacy, as survivors and the families of victims sought restitution of wealth and property confiscated during the Nazi years.

Beginning in 1953, the German government made payments to individual Jews and to the Jewish people as a way of acknowledging the German people’s responsibility for the crimes committed in their name.

The Holocaust. The National WWII Museum . What Was The Holocaust? Imperial War Museums . Introduction to the Holocaust. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum . Holocaust Remembrance. Council of Europe . Outreach Programme on the Holocaust. United Nations .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Holocaust and Genocide Studies Scholarly Journal

The major forum for scholarship on the Holocaust and other genocides, Holocaust and Genocide Studies is an international journal featuring research articles, interpretive essays, book reviews, a comprehensive bibliography of recently published relevant works in the social sciences and humanties, and an annual list of major research centers specializing in Holocaust studies.

Articles compel readers to:

Confront many aspects of human behavior

Contemplate major moral issues

Consider the role of sciences and technology in human affairs

Reconsider important features of political and social organization

With content from the disciplines of history, literature, economics, religious studies, anthropology, political science, sociology, and others, Holocaust and Genocide Studies also prints work on other genocides and near-genocidal episodes. The journal is published three times a year in cooperation with Oxford University Press.

About the Journal

Current issue.

For information about the journal, including instructions for contributors as well as tables of contents and abstracts of articles going back to volume 1, number 1 (Spring 1986), please visit the Oxford Journals website . Subscribers have access to the entire journal online at Oxford Journals at no additional cost.

Additionally, journal content from 1996 (Volume 10) onward is available at a variety of EBSCO databases covering the fields of history, sociology, and Jewish studies; these are available via institutional subscription. For more information about how your institution can subscribe to these databases, please visit EBSCO Online Research Databases , which posts journal content a year after publication on the Oxford University Press website. Beginning with volume 17 (2003), articles are also available online from Project Muse .

To receive advance electronic notification of future journal contents, sign up for Oxford University Press' contents-alerting service —a free service available to subscribers and non-subscribers alike.

Read Online

Faculty and students can read Holocaust and Genocide Studies through their university’s digital library subscriptions services. Oxford University Press has provided access to five virtual issues and three special issues of the journal. If you are unable to access journal content, please contact Oxford University Press’s customer service team at [email protected] , and they will be able to assist you.

Request Subscriptions and Issues

All requests for Holocaust and Genocide Studies subscriptions, recent single issues, and two back volumes may be placed by telephone or fax using a major credit card. You can also find information about subscriptions and access for non-subscribers on a pay-per-view basis at Oxford Journals . Please contact:

In the Americas

Tel: 800-852-7323 (USA and Canada only) or Tel: 919-677-0977 Fax: 919.677.1714 Email: [email protected] Mail: Journals Customer Service Oxford University Press 2001 Evans Road Cary, NC 27513, USA

In the UK and Europe

Tel: +44 (0)1865 353907 Fax: +44 (0)1865 353485 Email: [email protected] Mail: Journals Customer Service Oxford University Press Great Clarendon Street Oxford OX2 6DP, UK

Tel: +86(0)10-8515-1678 Fax: +86(0)10-8515-1678-105 Email: [email protected] Mail: Oxford University Press, Beijing Office, Unit 1504A, Tower E2, Oriental Plaza Towers No. 1 East Chang An Avenue Dong Cheng District, Beijing, 100738, China

Tel: +81-3-5444-5858 Fax: +81-3-3454-2929 Email: [email protected] Mail: Journals Customer Service Department Oxford University Press 4-5-10-8F Shiba Minato-ku, Tokyo, 108-8386, Japan

Back Issues

Back issues previous to the two back volumes can be obtained from: Periodicals Service Company 351 Fairview Avenue, Suite 300, Hudson, NY 12534 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 518.822.9300 Fax: 518.822.9302

The US Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Center’s mission is to ensure the long-term growth and vitality of Holocaust Studies. To do that, it is essential to provide opportunities for new generations of scholars. The vitality and the integrity of Holocaust Studies requires openness, independence, and free inquiry so that new ideas are generated and tested through peer review and public debate. The opinions of scholars expressed before, during the course of, or after their activities with the Mandel Center are their own and do not represent and are not endorsed by the Museum or its Mandel Center.

This Section

The Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies is a leading generator of new knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust.

- Collections Search

Find anything you save across the site in your account

In the Shadow of the Holocaust

By Masha Gessen

Berlin never stops reminding you of what happened there. Several museums examine totalitarianism and the Holocaust; the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe takes up an entire city block. In a sense, though, these larger structures are the least of it. The memorials that sneak up on you—the monument to burned books, which is literally underground, and the thousands of Stolpersteine , or “stumbling stones,” built into sidewalks to commemorate individual Jews, Sinti, Roma, homosexuals, mentally ill people, and others murdered by the Nazis—reveal the pervasiveness of the evils once committed in this place. In early November, when I was walking to a friend’s house in the city, I happened upon the information stand that marks the site of Hitler’s bunker. I had done so many times before. It looks like a neighborhood bulletin board, but it tells the story of the Führer’s final days.

In the late nineteen-nineties and early two-thousands, when many of these memorials were conceived and installed, I visited Berlin often. It was exhilarating to watch memory culture take shape. Here was a country, or at least a city, that was doing what most cultures cannot: looking at its own crimes, its own worst self. But, at some point, the effort began to feel static, glassed in, as though it were an effort not only to remember history but also to insure that only this particular history is remembered—and only in this way. This is true in the physical, visual sense. Many of the memorials use glass: the Reichstag, a building nearly destroyed during the Nazi era and rebuilt half a century later, is now topped by a glass dome; the burned-books memorial lives under glass; glass partitions and glass panes put order to the stunning, once haphazard collection called “Topography of Terror.” As Candice Breitz, a South African Jewish artist who lives in Berlin, told me, “The good intentions that came into play in the nineteen-eighties have, too often, solidified into dogma.”

Podcast: The Political Scene Masha Gessen talks with Tyler Foggatt.

Among the few spaces where memory representation is not set in apparent permanence are a couple of the galleries in the new building of the Jewish Museum, which was completed in 1999. When I visited in early November, a gallery on the ground floor was showing a video installation called “Rehearsing the Spectacle of Spectres.” The video was set in Kibbutz Be’eri , the community where, on October 7th, Hamas killed more than ninety people—almost one in ten residents—during its attack on Israel, which ultimately claimed more than twelve hundred lives. In the video, Be’eri residents take turns reciting the lines of a poem by one of the community’s members, the poet Anadad Eldan: “. . . from the swamp between the ribs / she surfaced who had submerged in you / and you are constrained not shouting / hunting for the forms that scamper outside.” The video, by the Berlin-based Israeli artists Nir Evron and Omer Krieger, was completed nine years ago. It begins with an aerial view of the area, the Gaza Strip visible, then slowly zooms in on the houses of the kibbutz, some of which looked like bunkers. I am not sure what the artists and the poet had initially meant to convey; now the installation looked like a work of mourning for Be’eri. (Eldan, who is nearly a hundred years old, survived the Hamas attack.)

Down the hallway was one of the spaces that the architect Daniel Libeskind, who designed the museum, called “voids”—shafts of air that pierce the building, symbolizing the absence of Jews in Germany through generations. There, an installation by the Israeli artist Menashe Kadishman, titled “Fallen Leaves,” consists of more than ten thousand rounds of iron with eyes and mouths cut into them, like casts of children’s drawings of screaming faces. When you walk on the faces, they clank, like shackles, or like the bolt handle of a rifle. Kadishman dedicated the work to victims of the Holocaust and other innocent victims of war and violence. I don’t know what Kadishman, who died in 2015, would have said about the current conflict. But, after I walked from the haunting video of Kibbutz Be’eri to the clanking iron faces, I thought of the thousands of residents of Gaza killed in retaliation for the lives of Jews killed by Hamas. Then I thought that, if I were to state this publicly in Germany, I might get in trouble.

On November 9th, to mark the eighty-fifth anniversary of Kristallnacht, a Star of David and the phrase “ Nie Wieder Ist Jetzt! ”—“Never Again Is Now!”—was projected in white and blue on Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate. That day, the Bundestag was considering a proposal titled “Fulfilling Historical Responsibility: Protecting Jewish Life in Germany,” which contained more than fifty measures intended to combat antisemitism in Germany, including deporting immigrants who commit antisemitic crimes; stepping up activities directed against the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (B.D.S.) movement; supporting Jewish artists “whose work is critical of antisemitism”; implementing a particular definition of antisemitism in funding and policing decisions; and beefing up coöperation between the German and the Israeli armed forces. In earlier remarks, the German Vice-Chancellor, Robert Habeck, who is a member of the Green Party, said that Muslims in Germany should “clearly distance themselves from antisemitism so as not to undermine their own right to tolerance.”

Germany has long regulated the ways in which the Holocaust is remembered and discussed. In 2008, when then Chancellor Angela Merkel spoke before the Knesset, on the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of the state of Israel, she emphasized Germany’s special responsibility not only for preserving the memory of the Holocaust as a unique historical atrocity but also for the security of Israel. This, she went on, was part of Germany’s Staatsräson —the reason for the existence of the state. The sentiment has since been repeated in Germany seemingly every time the topic of Israel, Jews, or antisemitism arises, including in Habeck’s remarks. “The phrase ‘Israel’s security is part of Germany’s Staatsräson ’ has never been an empty phrase,” he said. “And it must not become one.”

At the same time, an obscure yet strangely consequential debate on what constitutes antisemitism has taken place. In 2016, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (I.H.R.A.), an intergovernmental organization, adopted the following definition: “Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.” This definition was accompanied by eleven examples, which began with the obvious—calling for or justifying the killing of Jews—but also included “claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor” and “drawing comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis.”

This definition had no legal force, but it has had extraordinary influence. Twenty-five E.U. member states and the U.S. State Department have endorsed or adopted the I.H.R.A. definition. In 2019, President Donald Trump signed an executive order providing for the withholding of federal funds from colleges where students are not protected from antisemitism as defined by the I.H.R.A. On December 5th of this year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a nonbinding resolution condemning antisemitism as defined by the I.H.R.A.; it was proposed by two Jewish Republican representatives and opposed by several prominent Jewish Democrats, including New York’s Jerry Nadler.

In 2020, a group of academics proposed an alternative definition of antisemitism, which they called the Jerusalem Declaration . It defines antisemitism as “discrimination, prejudice, hostility or violence against Jews as Jews (or Jewish institutions as Jewish)” and provides examples that help distinguish anti-Israel statements and actions from antisemitic ones. But although some of the preëminent scholars of the Holocaust participated in drafting the declaration, it has barely made a dent in the growing influence of the I.H.R.A. definition. In 2021, the European Commission published a handbook “for the practical use” of the I.H.R.A. definition, which recommended, among other things, using the definition in training law-enforcement officers to recognize hate crimes, and creating the position of state attorney, or coördinator or commissioner for antisemitism.

Germany had already implemented this particular recommendation. In 2018, the country created the Office of the Federal Government Commissioner for Jewish Life in Germany and the Fight Against Antisemitism, a vast bureaucracy that includes commissioners at the state and local level, some of whom work out of prosecutors’ offices or police precincts. Since then, Germany has reported an almost uninterrupted rise in the number of antisemitic incidents: more than two thousand in 2019, more than three thousand in 2021, and, according to one monitoring group, a shocking nine hundred and ninety-four incidents in the month following the Hamas attack. But the statistics mix what Germans call Israelbezogener Antisemitismus —Israel-related antisemitism, such as instances of criticism of Israeli government policies—with violent attacks, such as an attempted shooting at a synagogue, in Halle, in 2019, which killed two bystanders; shots fired at a former rabbi’s house, in Essen, in 2022; and two Molotov cocktails thrown at a Berlin synagogue this fall. The number of incidents involving violence has, in fact, remained relatively steady, and has not increased following the Hamas attack.

There are now dozens of antisemitism commissioners throughout Germany. They have no single job description or legal framework for their work, but much of it appears to consist of publicly shaming those they see as antisemitic, often for “de-singularizing the Holocaust” or for criticizing Israel. Hardly any of these commissioners are Jewish. Indeed, the proportion of Jews among their targets is certainly higher. These have included the German-Israeli sociologist Moshe Zuckermann, who was targeted for supporting the B.D.S. movement, as was the South African Jewish photographer Adam Broomberg.

In 2019, the Bundestag passed a resolution condemning B.D.S. as antisemitic and recommending that state funding be withheld from events and institutions connected to B.D.S. The history of the resolution is telling. A version was originally introduced by the AfD, the radical-right ethnonationalist and Euroskeptic party then relatively new to the German parliament. Mainstream politicians rejected the resolution because it came from the AfD, but, apparently fearful of being seen as failing to fight antisemitism, immediately introduced a similar one of their own. The resolution was unbeatable because it linked B.D.S. to “the most terrible phase of German history.” For the AfD, whose leaders have made openly antisemitic statements and endorsed the revival of Nazi-era nationalist language, the spectre of antisemitism is a perfect, cynically wielded political instrument, both a ticket to the political mainstream and a weapon that can be used against Muslim immigrants.

The B.D.S. movement, which is inspired by the boycott movement against South African apartheid, seeks to use economic pressure to secure equal rights for Palestinians in Israel, end the occupation, and promote the return of Palestinian refugees. Many people find the B.D.S. movement problematic because it does not affirm the right of the Israeli state to exist—and, indeed, some B.D.S. supporters envision a total undoing of the Zionist project. Still, one could argue that associating a nonviolent boycott movement, whose supporters have explicitly positioned it as an alternative to armed struggle, with the Holocaust is the very definition of Holocaust relativism. But, according to the logic of German memory policy, because B.D.S. is directed against Jews—although many of the movement’s supporters are also Jewish—it is antisemitic. One could also argue that the inherent conflation of Jews with the state of Israel is antisemitic, even that it meets the I.H.R.A. definition of antisemitism. And, given the AfD’s involvement and the pattern of the resolution being used largely against Jews and people of color, one might think that this argument would gain traction. One would be wrong.

The German Basic Law, unlike the U.S. Constitution but like the constitutions of many other European countries, has not been interpreted to provide an absolute guarantee of freedom of speech. It does, however, promise freedom of expression not only in the press but in the arts and sciences, research, and teaching. It’s possible that, if the B.D.S. resolution became law, it would be deemed unconstitutional. But it has not been tested in this way. Part of what has made the resolution peculiarly powerful is the German state’s customary generosity: almost all museums, exhibits, conferences, festivals, and other cultural events receive funding from the federal, state, or local government. “It has created a McCarthyist environment,” Candice Breitz, the artist, told me. “Whenever we want to invite someone, they”—meaning whatever government agency may be funding an event—“Google their name with ‘B.D.S.,’ ‘Israel,’ ‘apartheid.’ ”

A couple of years ago, Breitz, whose art deals with issues of race and identity, and Michael Rothberg, who holds a Holocaust studies chair at the University of California, Los Angeles, tried to organize a symposium on German Holocaust memory, called “We Need to Talk.” After months of preparations, they had their state funding pulled, likely because the program included a panel connecting Auschwitz and the genocide of the Herero and the Nama people carried out between 1904 and 1908 by German colonizers in what is now Namibia. “Some of the techniques of the Shoah were developed then,” Breitz said. “But you are not allowed to speak about German colonialism and the Shoah in the same breath because it is a ‘levelling.’ ”

The insistence on the singularity of the Holocaust and the centrality of Germany’s commitment to reckoning with it are two sides of the same coin: they position the Holocaust as an event that Germans must always remember and mention but don’t have to fear repeating, because it is unlike anything else that’s ever happened or will happen. The German historian Stefanie Schüler-Springorum, who heads the Centre for Research on Antisemitism, in Berlin, has argued that unified Germany turned the reckoning with the Holocaust into its national idea, and as a result “any attempt to advance our understanding of the historical event itself, through comparisons with other German crimes or other genocides, can [be] and is being perceived as an attack on the very foundation of this new nation-state.” Perhaps that’s the meaning of “Never again is now.”

Some of the great Jewish thinkers who survived the Holocaust spent the rest of their lives trying to tell the world that the horror, while uniquely deadly, should not be seen as an aberration. That the Holocaust happened meant that it was possible—and remains possible. The sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman argued that the massive, systematic, and efficient nature of the Holocaust was a function of modernity—that, although it was by no means predetermined, it fell in line with other inventions of the twentieth century. Theodor Adorno studied what makes people inclined to follow authoritarian leaders and sought a moral principle that would prevent another Auschwitz.

In 1948, Hannah Arendt wrote an open letter that began, “Among the most disturbing political phenomena of our times is the emergence in the newly created state of Israel of the ‘Freedom Party’ (Tnuat Haherut), a political party closely akin in its organization, methods, political philosophy, and social appeal to the Nazi and Fascist parties.” Just three years after the Holocaust, Arendt was comparing a Jewish Israeli party to the Nazi Party, an act that today would be a clear violation of the I.H.R.A.’s definition of antisemitism. Arendt based her comparison on an attack carried out in part by the Irgun, a paramilitary predecessor of the Freedom Party, on the Arab village of Deir Yassin, which had not been involved in the war and was not a military objective. The attackers “killed most of its inhabitants—240 men, women, and children—and kept a few of them alive to parade as captives through the streets of Jerusalem.”

The occasion for Arendt’s letter was a planned visit to the United States by the party’s leader, Menachem Begin. Albert Einstein, another German Jew who fled the Nazis, added his signature. Thirty years later, Begin became Prime Minister of Israel. Another half century later, in Berlin, the philosopher Susan Neiman, who leads a research institute named for Einstein, spoke at the opening of a conference called “Hijacking Memory: The Holocaust and the New Right.” She suggested that she might face repercussions for challenging the ways in which Germany now wields its memory culture. Neiman is an Israeli citizen and a scholar of memory and morals. One of her books is called “ Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil .” In the past couple of years, Neiman said, memory culture had “gone haywire.”

Germany’s anti-B.D.S. resolution, for example, has had a distinct chilling effect on the country’s cultural sphere. The city of Aachen took back a ten-thousand-euro prize it had awarded to the Lebanese-American artist Walid Raad; the city of Dortmund and the jury for the fifteen-thousand-euro Nelly Sachs Prize similarly rescinded the honor that they had bestowed on the British-Pakistani writer Kamila Shamsie. The Cameroonian political philosopher Achille Mbembe had his invitation to a major festival questioned after the federal antisemitism commissioner accused him of supporting B.D.S. and “relativizing the Holocaust.” (Mbembe has said that he is not connected with the boycott movement; the festival itself was cancelled because of COVID .) The director of Berlin’s Jewish Museum, Peter Schäfer, resigned in 2019 after being accused of supporting B.D.S.—he did not, in fact, support the boycott movement, but the museum had posted a link, on Twitter, to a newspaper article that included criticism of the resolution. The office of Benjamin Netanyahu had also asked Merkel to cut the museum’s funding because, in the Israeli Prime Minister’s opinion, its exhibition on Jerusalem paid too much attention to the city’s Muslims. (Germany’s B.D.S. resolution may be unique in its impact but not in its content: a majority of U.S. states now have laws on the books that equate the boycott with antisemitism and withhold state funding from people and institutions that support it.)

After the “We Need to Talk” symposium was cancelled, Breitz and Rothberg regrouped and came up with a proposal for a symposium called “We Still Need to Talk.” The list of speakers was squeaky clean. A government entity vetted everyone and agreed to fund the gathering. It was scheduled for early December. Then Hamas attacked Israel . “We knew that after that every German politician would see it as extremely risky to be connected with an event that had Palestinian speakers or the word ‘apartheid,’ ” Breitz said. On October 17th, Breitz learned that funding had been pulled. Meanwhile, all over Germany, police were cracking down on demonstrations that call for a ceasefire in Gaza or manifest support for Palestinians. Instead of a symposium, Breitz and several others organized a protest. They called it “We Still Still Still Still Need to Talk.” About an hour into the gathering, police quietly cut through the crowd to confiscate a cardboard poster that read “From the River to the Sea, We Demand Equality.” The person who had brought the poster was a Jewish Israeli woman.

The “Fulfilling Historical Responsibility” proposal has since languished in committee. Still, the performative battle against antisemitism kept ramping up. In November, the planning of Documenta, one of the art world’s most important shows, was thrown into disarray after the newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung dug up a petition that a member of the artistic organizing committee, Ranjit Hoskote, had signed in 2019. The petition, written to protest a planned event on Zionism and Hindutva in Hoskote’s home town of Mumbai, denounced Zionism as “a racist ideology calling for a settler-colonial, apartheid state where non-Jews have unequal rights, and in practice, has been premised on the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians.” The Süddeutsche Zeitung reported on it under the heading “Antisemitism.” Hoskote resigned and the rest of the committee followed suit. A week later, Breitz read in a newspaper that a museum in Saarland had cancelled an exhibit of hers, which had been planned for 2024, “in view of the media coverage about the artist in connection with her controversial statements in the context of Hamas’ war of aggression against the state of Israel.”

This November, I left Berlin to travel to Kyiv, traversing, by train, Poland and then Ukraine. This is as good a place as any to say a few things about my relationship to the Jewish history of these lands. Many American Jews go to Poland to visit what little, if anything, is left of the old Jewish quarters, to eat food reconstructed according to recipes left by long-extinguished families, and to go on tours of Jewish history, Jewish ghettos, and Nazi concentration camps. I am closer to this history. I grew up in the Soviet Union in the nineteen-seventies, in the ever-present shadow of the Holocaust, because only a part of my family had survived it and because Soviet censors suppressed any public mention of it. When, around the age of nine, I learned that some Nazi war criminals were still on the loose, I stopped sleeping. I imagined one of them climbing in through our fifth-floor balcony to snatch me.

During summers, our cousin Anna and her sons would visit from Warsaw. Her parents had decided to kill themselves after the Warsaw Ghetto burned down. Anna’s father threw himself in front of a train. Anna’s mother tied the three-year-old Anna to her waist with a shawl and jumped into a river. They were plucked out of the water by a Polish man, and survived the war by hiding in the countryside. I knew the story, but I wasn’t allowed to mention it. Anna was an adult when she learned that she was a Holocaust survivor, and she waited to tell her own kids, who were around my age. The first time I went to Poland, in the nineteen-nineties, was to research the fate of my great-grandfather, who spent nearly three years in the Białystok Ghetto before being killed in Majdanek.

The Holocaust memory wars in Poland have run in parallel with Germany’s. The ideas being battled out in the two countries are different, but one consistent feature is the involvement of right-wing politicians in conjunction with the state of Israel. As in Germany, the nineteen-nineties and two-thousands saw ambitious memorialization efforts, both national and local, that broke through the silence of the Soviet years. Poles built museums and monuments that commemorated the Jews killed in the Holocaust—which claimed half of its victims in Nazi-occupied Poland—and the Jewish culture that was lost with them. Then the backlash came. It coincided with the rise to power of the right-wing, illiberal Law and Justice Party, in 2015. Poles now wanted a version of history in which they were victims of the Nazi occupation alongside the Jews, whom they tried to protect from the Nazis.

This was not true: instances of Poles risking their lives to save Jews from the Germans, as in the case of my cousin Anna, were exceedingly rare, while the opposite—entire communities or structures of the pre-occupation Polish state, such as the police or city offices, carrying out the mass murder of Jews—was common. But historians who studied the Poles’ role in the Holocaust came under attack . The Polish-born Princeton historian Jan Tomasz Gross was interrogated and threatened with prosecution for writing that Poles killed more Polish Jews than Germans. The Polish authorities hounded him even after he retired. The government squeezed Dariusz Stola, the head of POLIN , Warsaw’s innovative museum of Polish Jewish history, out of his post. The historians Jan Grabowski and Barbara Engelking were dragged into court for writing that the mayor of a Polish village had been a collaborator in the Holocaust.

When I wrote about Grabowski and Engleking’s case, I received some of the scariest death threats of my life. (I’ve been sent a lot of death threats; most are forgettable.) One, sent to a work e-mail address, read, “If you keep writing lies about Poland and the Poles, I will deliver these bullets to your body. See the attachment! Five of them in every kneecap, so you won’t walk again. But if you continue to spread your Jewish hatred, I will deliver next 5 bullets in your pussy. The third step you won’t notice. But don’t worry, I’m not visiting you next week or eight weeks, I’ll be back when you forget this e-mail, maybe in 5 years. You’re on my list. . . .” The attachment was a picture of two shiny bullets in the palm of a hand. The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, headed by a government appointee, tweeted a condemnation of my article, as did the account of the World Jewish Congress. A few months later, a speaking invitation to a university fell through because, the university told my speaking agent, it had emerged that I might be an antisemite.

Throughout the Polish Holocaust-memory wars, Israel maintained friendly relations with Poland. In 2018, Netanyahu and the Polish Prime Minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, issued a joint statement against “actions aimed at blaming Poland or the Polish nation as a whole for the atrocities committed by the Nazis and their collaborators of different nations.” The statement asserted, falsely, that “structures of the Polish underground state supervised by the Polish government-in-exile created a mechanism of systematic help and support to Jewish people.” Netanyahu was building alliances with the illiberal governments of Central European countries, such as Poland and Hungary, in part to prevent an anti-occupation consensus from solidifying in the European Union. For this, he was willing to lie about the Holocaust.

Each year, tens of thousands of Israeli teen-agers travel to the Auschwitz museum before graduating from high school (though last year the trips were called off over security issues and the Polish government’s growing insistence that Poles’ involvement in the Holocaust be written out of history). It is a powerful, identity-forming trip that comes just a year or two before young Israelis join the military. Noam Chayut, a founder of Breaking the Silence, an anti-occupation advocacy group in Israel, has written of his own high-school trip, which took place in the late nineteen-nineties, “Now, in Poland, as a high-school adolescent, I began to sense belonging, self-love, power and pride, and the desire to contribute, to live and be strong, so strong that no one would ever try to hurt me.”

Chayut took this feeling into the I.D.F., which posted him to the occupied West Bank. One day he was putting up property-confiscation notices. A group of children was playing nearby. Chayut flashed what he considered a kind and non-threatening smile at a little girl. The rest of the children scampered off, but the girl froze, terrified, until she, too, ran away. Later, when Chayut published a book about the transformation this encounter precipitated, he wrote that he wasn’t sure why it was this girl: “After all, there was also the shackled kid in the Jeep and the girl whose family home we had broken into late at night to remove her mother and aunt. And there were plenty of children, hundreds of them, screaming and crying as we rummaged through their rooms and their things. And there was the child from Jenin whose wall we blasted with an explosive charge that blew a hole just a few centimeters from his head. Miraculously, he was uninjured, but I’m sure his hearing and his mind were badly impaired.” But in the eyes of that girl, on that day, Chayut saw a reflection of annihilatory evil, the kind that he had been taught existed, but only between 1933 and 1945, and only where the Nazis ruled. Chayut called his book “ The Girl Who Stole My Holocaust .”

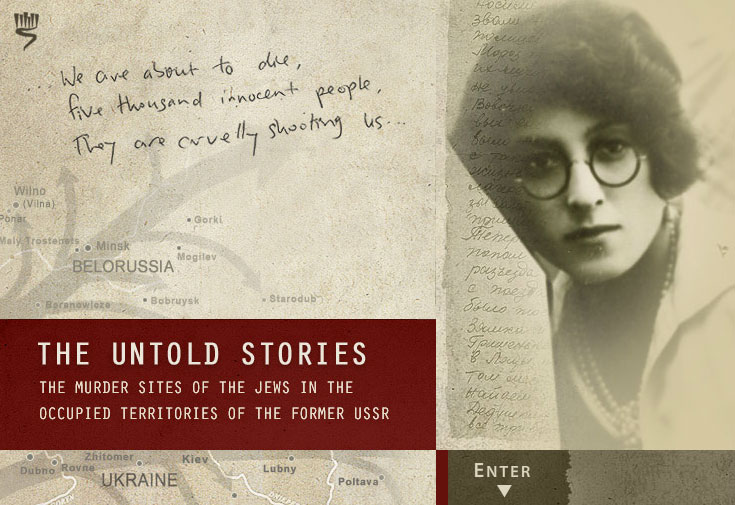

I took the train from the Polish border to Kyiv. Nearly thirty-four thousand Jews were shot at Babyn Yar, a giant ravine on the outskirts of the city, in just thirty-six hours in September, 1941. Tens of thousands more people died there before the war was over. This was what is now known as the Holocaust by bullets. Many of the countries in which these massacres took place—the Baltics, Belarus, Ukraine—were re-colonized by the Soviet Union following the Second World War. Dissidents and Jewish cultural activists risked their freedom to maintain a memory of these tragedies, to collect testimony and names, and, where possible, to clean up and protect the sites themselves. After the fall of the Soviet Union, memorialization projects accompanied efforts to join the European Union. “Holocaust recognition is our contemporary European entry ticket,” the historian Tony Judt wrote in his 2005 book, “ Postwar .”

In the Rumbula forest, outside of Riga, for example, where some twenty-five thousand Jews were murdered in 1941, a memorial was unveiled in 2002, two years before Latvia was admitted to the E.U. A serious effort to commemorate Babyn Yar coalesced after the 2014 revolution that set Ukraine on an aspirational path to the E.U. By the time Russia invaded Ukraine, in February, 2022, several smaller structures had been completed and ambitious plans for a larger museum complex were in place. With the invasion, construction halted. One week into the full-scale war, a Russian missile hit directly next to the memorial complex, killing at least four people. Since then, some of the people associated with the project have reconstituted themselves as a team of war-crimes investigators.

The Ukrainian President, Volodymyr Zelensky, has waged an earnest campaign to win Israeli support for Ukraine. In March, 2022, he delivered a speech to the Knesset, in which he didn’t stress his own Jewish heritage but focussed on the inextricable historical connection between Jews and Ukrainians. He drew unambiguous parallels between the Putin regime and the Nazi Party. He even claimed that eighty years ago Ukrainians rescued Jews. (As with Poland, any claim that such aid was widespread is false.) But what worked for the right-wing government of Poland did not work for the pro-Europe President of Ukraine. Israel has not given Ukraine the help it has begged for in its war against Russia, a country that openly supports Hamas and Hezbollah.

Still, both before and after the October 7th attack, the phrase I heard in Ukraine possibly more than any other was “We need to be like Israel.” Politicians, journalists, intellectuals, and ordinary Ukrainians identify with the story Israel tells about itself, that of a tiny but mighty island of democracy standing strong against enemies who surround it. Some Ukrainian left-wing intellectuals have argued that Ukraine, which is fighting an anti-colonial war against an occupying power, should see its reflection in Palestine, not Israel. These voices are marginal and most often belong to young Ukrainians who are studying or have studied abroad. Following the Hamas attack, Zelensky wanted to rush to Israel as a show of support and unity between Israel and Ukraine. Israeli authorities seem to have other ideas—the visit has not happened.

While Ukraine has been unsuccessfully trying to get Israel to acknowledge that Russia’s invasion resembles Nazi Germany’s genocidal aggression, Moscow has built a propaganda universe around portraying Zelensky’s government, the Ukrainian military, and the Ukrainian people as Nazis. The Second World War is the central event of Russia’s historical myth. During Vladimir Putin’s reign, as the last of the people who lived through the war have been dying, commemorative events have turned into carnivals that celebrate Russian victimhood. The U.S.S.R. lost at least twenty-seven million people in that war, a disproportionate number of them Ukrainians. The Soviet Union and Russia have fought in wars almost continuously since 1945, but the word “war” is still synonymous with the Second World War and the word “enemy” is used interchangeably with “fascist” and “Nazi.” This made it that much easier for Putin, in declaring a new war, to brand Ukrainians as Nazis.

Netanyahu has compared the Hamas murders at the music festival to the Holocaust by bullets. This comparison, picked up and recirculated by world leaders, including President Biden, serves to bolster Israel’s case for inflicting collective punishment on the residents of Gaza. Similarly, when Putin says “Nazi” or “fascist,” he means that the Ukrainian government is so dangerous that Russia is justified in carpet-bombing and laying siege to Ukrainian cities and killing Ukrainian civilians. There are significant differences, of course: Russia’s claims that Ukraine attacked it first, and its portrayals of the Ukrainian government as fascist, are false; Hamas, on the other hand, is a tyrannical power that attacked Israel and committed atrocities that we cannot yet fully comprehend. But do these differences matter when the case being made is for killing children?

In the first weeks of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, when its troops were occupying the western suburbs of Kyiv, the director of Kyiv’s museum of the Second World War, Yurii Savchuk, was living at the museum and rethinking the core exhibit. One day after the Ukrainian military drove the Russians out of the Kyiv region, he met with the commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian armed forces, Valerii Zaluzhnyi, and got permission to start collecting artifacts. Savchuk and his staff went to Bucha, Irpin, and other towns and cities that had just been “deoccupied,” as Ukrainians have taken to saying, and interviewed people who had not yet told their stories. “This was before the exhumations and the reburials,” Savchuk told me. “We saw the true face of war, with all its emotions. The fear, the terror, was in the atmosphere, and we absorbed it with the air.”

In May, 2022, the museum opened a new exhibit, titled “Ukraine – Crucifixion.” It begins with a display of Russian soldiers’ boots, which Savchuk’s team had collected. It’s an odd reversal: both the Auschwitz museum and the Holocaust museum in Washington, D.C., have displayed hundreds or thousands of shoes that belonged to victims of the Holocaust. They convey the scale of loss, even as they show only a tiny fraction of it. The display in Kyiv shows the scale of the menace. The boots are arranged on the floor of the museum in the pattern of a five-pointed star, the symbol of the Red Army that has become as sinister in Ukraine as the swastika. In September, Kyiv removed five-pointed stars from a monument to the Second World War in what used to be called Victory Square—it’s been renamed because the very word “Victory” connotes Russia’s celebration in what it still calls the Great Patriotic War. The city also changed the dates on the monument, from “1941-1945”—the years of the war between the Soviet Union and Germany—to “1939-1945.” Correcting memory one monument at a time.

In 1954, an Israeli court heard a libel case involving a Hungarian Jew named Israel Kastner. A decade earlier, when Germany occupied Hungary and belatedly rushed to implement the mass murder of its Jews, Kastner, as a leader of the Jewish community, entered into negotiations with Adolf Eichmann himself. Kastner proposed to buy the lives of Hungary’s Jews with ten thousand trucks. When this failed, he negotiated to save sixteen hundred and eighty-five people by transporting them by chartered train to Switzerland. Hundreds of thousands of other Hungarian Jews were loaded onto trains to death camps. A Hungarian Jewish survivor had publicly accused Kastner of having collaborated with the Germans. Kastner sued for libel and, in effect, found himself on trial. The judge concluded that Kastner had “sold his soul to the devil.”

The charge of collaboration against Kastner rested on the allegation that he had failed to tell people that they were going to their deaths. His accusers argued that, had he warned the deportees, they would have rebelled, not gone to the death camps like sheep to slaughter. The trial has been read as the beginning of a discursive standoff in which the Israeli right argues for preëmptive violence and sees the left as willfully defenseless. By the time of the trial, Kastner was a left-wing politician; his accuser was a right-wing activist.

Seven years later, the judge who had presided over the Kastner libel trial was one of the three judges in the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Here was the devil himself. The prosecution argued that Eichmann represented but one iteration of the eternal threat to the Jews. The trial helped to solidify the narrative that, to prevent annihilation, Jews should be prepared to use force preëmptively. Arendt, reporting on the trial , would have none of this. Her phrase “the banality of evil” elicited perhaps the original accusations, levelled against a Jew, of trivializing the Holocaust. She wasn’t. But she saw that Eichmann was no devil, that perhaps the devil didn’t exist. She had reasoned that there was no such thing as radical evil, that evil was always ordinary even when it was extreme—something “born in the gutter,” as she put it later, something of “utter shallowness.”

Arendt also took issue with the prosecution’s story that Jews were the victims of, as she put it, “a historical principle stretching from Pharaoh to Haman—the victim of a metaphysical principle.” This story, rooted in the Biblical legend of Amalek, a people of the Negev Desert who repeatedly fought the ancient Israelites, holds that every generation of Jews faces its own Amalek. I learned this story as a teen-ager; it was the first Torah lesson I ever received, taught by a rabbi who gathered the kids in a suburb of Rome where Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union lived while waiting for their papers to enter the United States, Canada, or Australia. In this story, as told by the prosecutor in the Eichmann trial, the Holocaust is a predetermined event, part of Jewish history—and only Jewish history. The Jews, in this version, always have a well-justified fear of annihilation. Indeed, they can survive only if they act as though annihilation were imminent.

When I first learned the legend of Amalek, it made perfect sense to me. It described my knowledge of the world; it helped me connect my experience of getting teased and beaten up to my great-grandmother’s admonitions that using household Yiddish expressions in public was dangerous, to the unfathomable injustice of my grandfather and great-grandfather and scores of other relatives being killed before I was born. I was fourteen and lonely. I knew myself and my family to be victims, and the legend of Amalek imbued my sense of victimhood with meaning and a sense of community.

Netanyahu has been brandishing Amalek in the wake of the Hamas attack. The logic of this legend, as he wields it—that Jews occupy a singular place in history and have an exclusive claim on victimhood—has bolstered the anti-antisemitism bureaucracy in Germany and the unholy alliance between Israel and the European far right. But no nation is all victim all the time or all perpetrator all the time. Just as much of Israel’s claim to impunity lies in the Jews’ perpetual victim status, many of the country’s critics have tried to excuse Hamas’s act of terrorism as a predictable response to Israel’s oppression of Palestinians. Conversely, in the eyes of Israel’s supporters, Palestinians in Gaza can’t be victims because Hamas attacked Israel first. The fight over one rightful claim to victimhood runs on forever.

For the last seventeen years, Gaza has been a hyperdensely populated, impoverished, walled-in compound where only a small fraction of the population had the right to leave for even a short amount of time—in other words, a ghetto. Not like the Jewish ghetto in Venice or an inner-city ghetto in America but like a Jewish ghetto in an Eastern European country occupied by Nazi Germany. In the two months since Hamas attacked Israel, all Gazans have suffered from the barely interrupted onslaught of Israeli forces. Thousands have died. On average, a child is killed in Gaza every ten minutes. Israeli bombs have struck hospitals, maternity wards, and ambulances. Eight out of ten Gazans are now homeless, moving from one place to another, never able to get to safety.

The term “open-air prison” seems to have been coined in 2010 by David Cameron, the British Foreign Secretary who was then Prime Minister. Many human-rights organizations that document conditions in Gaza have adopted the description. But as in the Jewish ghettoes of Occupied Europe, there are no prison guards—Gaza is policed not by the occupiers but by a local force. Presumably, the more fitting term “ghetto” would have drawn fire for comparing the predicament of besieged Gazans to that of ghettoized Jews. It also would have given us the language to describe what is happening in Gaza now. The ghetto is being liquidated.

The Nazis claimed that ghettos were necessary to protect non-Jews from diseases spread by Jews. Israel has claimed that the isolation of Gaza, like the wall in the West Bank, is required to protect Israelis from terrorist attacks carried out by Palestinians. The Nazi claim had no basis in reality, while the Israeli claim stems from actual and repeated acts of violence. These are essential differences. Yet both claims propose that an occupying authority can choose to isolate, immiserate—and, now, mortally endanger—an entire population of people in the name of protecting its own.

From the earliest days of Israel’s founding, the comparison of displaced Palestinians to displaced Jews has presented itself, only to be swatted away. In 1948, the year the state was created, an article in the Israeli newspaper Maariv described the dire conditions—“old people so weak they were on the verge of death”; “a boy with two paralyzed legs”; “another boy whose hands were severed”—in which Palestinians, mostly women and children, departed the village of Tantura after Israeli troops occupied it: “One woman carried her child in one arm and with the other hand she held her elderly mother. The latter couldn’t keep up the pace, she yelled and begged her daughter to slow down, but the daughter did not consent. Finally the old lady collapsed onto the road and couldn’t move. The daughter pulled out her hair … lest she not make it on time. And worse than this was the association to Jewish mothers and grandmothers who lagged this way on the roads under the crop of murderers.” The journalist caught himself. “There is obviously no room for such a comparison,” he wrote. “This fate—they brought upon themselves.”

Jews took up arms in 1948 to claim land that was offered to them by a United Nations decision to partition what had been British-controlled Palestine. The Palestinians, supported by surrounding Arab states, did not accept the partition and Israel’s declaration of independence. Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Transjordan invaded the proto-Israeli state, starting what Israel now calls the War of Independence. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fled the fighting. Those who did not were driven out of their villages by Israeli forces. Most of them were never able to return. The Palestinians remember 1948 as the Nakba, a word that means “catastrophe” in Arabic, just as Shoah means “catastrophe” in Hebrew. That the comparison is unavoidable has compelled many Israelis to assert that, unlike the Jews, Palestinians brought their catastrophe on themselves.

The day I arrived in Kyiv, someone handed me a thick book. It was the first academic study of Stepan Bandera to be published in Ukraine. Bandera is a Ukrainian hero: he fought against the Soviet regime; dozens of monuments to him have appeared since the collapse of the U.S.S.R. He ended up in Germany after the Second World War, led a partisan movement from exile, and died after being poisoned by a K.G.B. agent, in 1959. Bandera was also a committed fascist, an ideologue who wanted to build a totalitarian regime. These facts are detailed in the book, which has sold about twelve hundred copies. (Many bookstores have refused to carry it.) Russia makes gleeful use of Ukraine’s Bandera cult as evidence that Ukraine is a Nazi state. Ukrainians mostly respond by whitewashing Bandera’s legacy. It is ever so hard for people to wrap their minds around the idea that someone could have been the enemy of your enemy and yet not a benevolent force. A victim and also a perpetrator. Or vice versa. ♦

An earlier version of this article incorrectly described what Jan Tomasz Gross wrote. It also misstated when Anna’s parents decided to kill themselves and Anna’s age at the time of those events.

New Yorker Favorites

They thought that they’d found the perfect apartment. They weren’t alone .

After high-school football stars were accused of rape, online vigilantes demanded that justice be served .

The world’s oldest temple and the dawn of civilization .

What happened to the whale from “Free Willy.”

It was one of the oldest buildings left downtown. Why not try to save it ?

The religious right’s leading ghostwriter .

A comic strip by Alison Bechdel: the seven-minute semi-sadistic workout .

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Ruth Margalit

By Jay Caspian Kang

By Susan B. Glasser

By David Remnick

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section History of the Holocaust

Introduction, general overviews.

- Jewish Responses in Germany to Persecution during the Prewar Period, 1933–1941

- The Third Reich, the German Public, and Nazi Anti-Semitism

- Racial Science

- Other Victims

- Final Solution: Decision-Making Process

- Killing by Shooting: Einsatzgruppen and Their Compatriots

- Concentration Camps / Forced Labor

- Extermination Centers

- Perpetrators

- Women in the Holocaust

- Economic Aspects of the Holocaust

- Punishment/Trials

- Church Responses

- Memoirs, Diaries, and Oral Histories as Historical Sources

- Holocaust Historiography

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Holocaust Literature

- (Holocaust) Memorial Books

- Holocaust Museums and Memorials

- Kristallnacht: The November Pogrom 1938 in Nazi Germany

- The Holocaust In Austria

- The Holocaust in France

- The Holocaust in Germany

- The Holocaust in Poland

- The Holocaust in the Netherlands

- The Holocaust in the Soviet Union

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Chofetz Chaim (Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan)

- Jews in Medieval Sicily

- Time in Modern Jewish Thought

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

History of the Holocaust by Deborah Lipstadt LAST REVIEWED: 26 May 2016 LAST MODIFIED: 26 May 2016 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199840731-0127

Many historians consider the Holocaust, the systematic murder of approximately six million Jews during 1941–1945, as one of the defining moments, if not a touchstone, of the political, ethical, and religious discourse of the 20th century. It is the only time that a state, as opposed to an insurgent entity or a group of independent actors, determined to murder every member of a particular group, irrespective of their age, gender, education, location, political or religious outlook, or national identity. Any Jew across the European continent and beyond (e.g., Libya, Crete, and Rhodes) whom the Germans could lay their hands on became a potential victim. As a result of this program, which the Germans called the Final Solution, nearly two-thirds of world Jewry was murdered. The Nazis considered killing the Jews such an urgent and necessary act that even when they were losing the war they pursued this goal. From the earliest history of the Nazi Party in the 1920s, the party cast the Jew as an existential threat to the German nation. While the Nazis made the threat posed by the Jews a cornerstone of their ideology and were intent on murdering all Jews they could find, they also targeted other groups. The first to be mass murdered were those inhabitants of the Reich—“Aryans” and Jews—whom the Nazis deemed to be physically or mentally disabled and consequently “unworthy of life.” German authorities also severely persecuted German homosexuals and murdered many eastern European (particularly Slav and Polish) intellectuals and religious leaders. They also killed two to three million Soviet prisoners of war. Millions of slave laborers, particularly from eastern Europe, served in horrendous conditions, and many died as a result. The mass killings of Jews took part in two phases. The first one started in June 1941, after the invasion of the Soviet Union. Conducted by special German units called the Einsatzgruppen and Ordnungspolizei (Order Police) with extensive aid of the Wehrmacht (German army) and non-German local militia, police, and civilians, these mass shootings resulted in the murder of over a million Jews. By the end of 1941, German authorities, concerned about the emotional toll the shooting was taking on the shooters, introduced gas buses and then gas chambers.

The vast geographic reach of the Holocaust presents a challenge to historians who want to address its broadest contours. There is an immense body of research on a myriad of aspects of the topic. This makes the need for syntheses all the more crucial. Hilberg 1985 is one of the earliest comprehensive studies of the bureaucratic structure of the Final Solution. It is highly detailed and remains a standard. More-readable volumes include Friedländer 1997 and Friedländer 2007 , which take a broader perspective and focus on the victims as well as the perpetrators. Dwork and van Pelt 2002 and Bergen 2009 were written as textbooks for college use, while Longerich 2010 is more recent and includes new archival information. Berenbaum and Peck 2002 and Friedman 2011 are particularly useful in that they each contain a range of articles by leading scholars in the field. Hayes 2015 is a most useful teaching tool with long selections on most of the topics that would be included in an introductory history of the Holocaust. Hayes and Roth 2010 contains articles by leading scholars who both review a particular aspect of the Holocaust and assess the state of the current research on that aspect.

Berenbaum, Michael, and Abraham J. Peck, eds. The Holocaust and History: The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed, and the Reexamined . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002.

This edited volume contains articles by experts in the field on many of the issues central to the history of the Holocaust, including anti-Semitism within Nazi ideology, the bureaucracy of the Nazi state, the background and motivation of the killers, the concentration camp system, Jewish leadership and resistance, rescuers, onlookers, and the survivor experience.

Bergen, Doris L. War & Genocide: A Concise History of the Holocaust . 2d ed. Critical Issues in World and International History. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009.

A concise history of the period that also asks some of the broader and more-theoretical questions. An excellent starting point for those with little background or who want an overview of the history and the underlying theoretical issues.

Dwork, Debórah, and Robert Jan van Pelt. Holocaust: A History . London: John Murray, 2002.

This comprehensive textbook artfully weaves together historical data with memoirs and other firsthand sources. Currently, this is one of the best texts for classroom use or to introduce someone to this vast topic.

Friedländer, Saul. Nazi Germany and the Jews . Vol. 1, The Years of Persecution, 1933–1939 . New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

This is a sweeping, authoritative, and exceptionally readable account of the initial years of Nazi rule. Friedländer weaves together evidence from the perpetrators as well as the victims.

Friedländer, Saul. The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939–1945 . 1st ed. New York: HarperCollins, 2007.

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize in history, this volume elegantly melds the story of the persecution with the experience of the victims.

Friedman, Jonathan C., ed. The Routledge History of the Holocaust . Routledge Histories. New York: Routledge, 2011.

An exceptionally useful edited volume on an array of aspects of the history of the Holocaust, by leading figures in the field. Many of the authors pay particular attention to the evolution of their historical field. The volume serves, therefore, both as a historical and historiographical tool.

Hayes, Peter, ed. How Was It Possible? A Holocaust Reader . Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

Hayes believes the title’s question is answerable. This compendium of highly readable selections from participants, witnesses, and scholars addresses the fundamental issues that ultimately “explain” the Holocaust. It can be a text for a Holocaust history course as well as of interest to those already familiar with the topic.

Hayes, Peter, and John K. Roth, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Holocaust Studies . Oxford Handbooks. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

This profoundly useful book recognizes that study of Holocaust history crosses traditional boundaries of academic disciplines. The forty-seven essays in the book summarize the state of the field at the time of publication and delineate future challenges. Each essay is an excellent starting point for someone interested in exploring a particular topic in depth.

Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews . New York: Holmes & Meier, 1985.