Groupthink: Definition, Signs, Examples, and How to Avoid It

Derek Schaedig

Outreach Specialist

B.A., Psychology, Harvard University

Derek Schaedig, who holds a B.A. in Psychology from Harvard University, is a mental health advocate. His lived experience with mental illness has been showcased in various podcasts and articles. He currently serves as a part-time outreach specialist for the Mental Health Foundation of West Michigan.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Groupthink refers to the tendency for certain types of groups to reach decisions that are extreme and which tend to be unwise or unrealistic

Groupthink occurs when individuals in cohesive groups fail to consider alternative perspectives because they are motivated to reach a consensus which typically results in making less-than-desirable decisions.

For example, group members may ignore or discount information that is inconsistent with their chosen decision and express strong disapproval against any group member who might disagree.

Janis (1971, 1982) popularized the term groupthink; however, he did not originate the concept. That is generally accredited to George Orwell as he describes the psychological phenomenon as “crimethink” or “doublethink” in his famous dystopian novel titled 1984 (Orwell, 1949).

Janis described groupthink early on as “the mode of thinking that persons engage in when concurrence seeking becomes so dominant in a cohesive ingroup that it tends to override realistic appraisal of alternative courses of action” (1972, p. 9).

Groupthink typically connotes a negative effect. In fact, Janis described it originally in his book published in 1972 titled Victims of Groupthink: A psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes as “a deterioration of mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment that results from in-group pressures” (Janis, 1972, p. 9).

Lack of diversity in groups : Groups that have members who are very similar to one another can be a cause of groupthink. With a lack of diverse perspectives, the group fails to consider outside perspectives.

Furthermore, these group embers may engage in more negative attitudes towards outgroup members, which can exacerbate groupthink.

Lack of impartial leadership : Groups with particularly powerful leaders who fail to seriously consider perspectives other than their own are prone to groupthink as well.

These leaders can overpower group members’ opinions that oppose their own ideas.

Stress : Placing a decision-making group under stress in scenarios such as one where there are moral dilemmas can increase the chances of groupthink occurring.

These groups may try to reach a consensus irrationally.

Time constraints : Related to stress, placing time constraints on a decision being made can increase the amount of anxiety, also leading to groupthink.

Highly cohesive groups : Groups that are particularly close-knit typically display more groupthink symptoms than groups that are not.

Lack of outside perspectives : Only considering the perspectives of in-group members can lead to groupthink as well.

Motivation to maintain group members’ self-esteem : If group members are motivated to maintain each other’s self-esteem, they may not raise their voices against the group consensus.

In Janis’s first book, he cited eight symptoms of groupthink to look out for in order to avoid the phenomena from occurring (Janis, 1972).

Invulnerability : When groups begin to believe their decisions and actions are untouchable or that the group is invincible, they ignore warnings or signs of danger that run contrary to their consensus.

Rationale : Groups that engage in groupthink rationalize their decisions even in the face of obvious warning signs or negative feedback that they receive.

This is typically thought to be the case because if the group took into further consideration these pushbacks, the group members’ egos, as well as the time needed to make the decision, may be harmed.

Morality : Groups may also believe that their group is inherently morally correct, and they may therefore ignore potential moral or ethical consequences of their decision.

Stereotypes : People or groups that oppose the group engaging in groupthink may be rendered enemies as well. This results in mislabeling the enemy group as “stupid” or “weak” when they may not be.

Pressure : Groups may directly pressure members of the group who contradict the policy advocated by the group.

This forces them to not be able to push back against any arguments being made. This can leave groups prone to making irrational decisions.

Self-censorship : Members of groups can sometimes censor themselves too.

These individuals may hold off on raising an opinion contrary to the group consensus or convince themselves their opposing viewpoint is unimportant for fear of judgment from the group.

Unanimity : Sometimes, the false assumption can be made that if everyone in the group is silent, then everyone must agree with what is being put forth.

Mindguards : This term refers to when members of the group appoint themselves as protectors of the leader or other important group members.

Mindguards dismiss information that contradicts popular opinion or about past decisions to maintain group self-esteem.

Consequences

Poor decisions : Potentially, the largest overall impact groupthink can have on decision-making groups is that they are more prone to making poor decisions.

The effects of groupthink can be especially harmful in the military, medical, and political courses of action.

Self-censorship : Individuals within the group affected by groupthink may not be as effective as possible when helping make decisions because they may hold back their potentially helpful opinions if they run contrary to the group’s popular opinion.

Inefficient problem solving : Because groups who experience the effects of groupthink fail to consider alternative perspectives, they can sometimes fail to consider ways to solve problems that deviate from their original plan of action.

This can lead to inefficiencies in the group’s problem-solving capabilities.

Harmful stereotypes can develop : Groups may begin to believe that their group is inherently morally right.

They, therefore, consider themselves the “in-group” and label others as outsiders or the “out-group,” which can become harmful to those on the outside as irrational thoughts about them begin to develop.

Lack of creativity : Because members of these groups may self-censor themselves or have pressure put on them by the group to conform, a lack of creativity may result due to the group not encouraging different ideas than the norm.

Blindness to negative outcomes : Since groups affected by groupthink can sometimes believe they are inherently correct, they may be unable to see the potentially negative outcomes of their decisions.

They, therefore, will not be able to plan accordingly if a negative outcome occurs.

Lack of preparation to manage negative outcomes : Because these groups can be overconfident in their decisions, they are more likely to be ill-prepared if their plan does not succeed.

Inability to see other solutions : Groupthink can lead to the group failing to consider other opinions or ideas. This leads to the group viewing only the group consensus as the correct solution.

Obedience to authority without question : Members of the group are more likely to follow their leaders blindly, never raising their opinion against whether the actions the group agrees on are moral or the correct course of action.

Can Groupthink Ever be a Good Thing?

Groupthink is generally considered a negative phenomenon.

Groups generally can benefit from hearing a diverse set of perspectives and information, and failing to do so can result in suboptimal decisions being made.

However, it is true that groups who engage in groupthink can make decisions quickly (although they may not be the best decision possible).

Also, anxiety can be reduced in the group because the group believes their decisions cannot be flawed. Groups who suffer from groupthink view themselves as untouchable (Janis, 1972).

Furthermore, groups rationalize the decision they made, whether it was the best option or not, and therefore convince themselves that the risks they are assuming are not as great as they truly are.

Lastly, the group may also believe that they are inherently morally right, which helps the members of the group cease to feel shame or guilt.

Overall though, groups should take precautions to avoid groupthink as much as possible.

Real-Life Scenarios

The social and political consequences of groupthink may be far-reaching, and history has many examples of major blunders that have been the result of decisions reached in this way.

Many case scenarios have been analyzed, such as the Invasion of Iraq (Badie, 2010), the attempt to rescue the American prisoners in the Vietnam War in the Son Tay raid (Amidon, 2005), and fraudulent behavior at WorldCom (Scharff, 2005) among many other flawed decisions cited for failing due to groupthink.

However, the original real-life scenarios of groupthink discussed by Janis were the escalation of the Vietnam War, the Bay of Bigs Scandal, and the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

The Vietnam War

Elected United States (U.S.) government officials during Vietnam showed signs of invulnerability (Janis, 1972).

The U.S. suffered multiple failures and setbacks, but they continued with their war efforts ignoring the danger and warning signs because they believed they would win no matter what.

Furthermore, the U.S. leaders rationalized their escalated bombing campaigns ignoring the negative feedback that they continuously received.

The U.S. also viewed their decisions as inherently morally right. President Johnson considered the same four factors every Tuesday: the military advantage of the U.S., the risk to American aircraft and pilots, the danger of forcing other countries into the fighting, and the danger of heavy civilian causalities. By engaging in this ritualization, they failed to effectively consider the morality of their decisions.

President Lyndon B. Johnson’s domino theory was an example of stereotyping as well. By viewing the enemy and its surrounding countries as too incompetent to make their own correct decisions, the U.S. administration made decisions that escalated the war.

Reportedly, Johnson once pressured former White House Press Secretary Bill Moyers to stop pushing back against the U.S. bombing campaign. Once, when Moyers entered a meeting, Johnson said of Moyers, “Well, here comes Mr. Stop-the-bombings.”

Bay of Pigs

President John F. Kennedy’s administration suffered from the illusion of invulnerability as well. Despite the plans to invade the Bay of Pigs leaking out, Kennedy’s administration proceeded with the plans ignoring the negative warning signs (Janis, 1972).

Historian Arthur J. Schlesinger expressed his strong objections against the war to both President Kennedy and Secretary of State Dean Rusk individually, but when it came to the group discussions on the decision to invade or not, Schlesinger stayed quiet.

He fell prey to believing that the ingroup was inherently moral, so Janis argued and kept his qualms quiet.

Another symptom of groupthink that Kennedy and his group experienced was stereotyping (Janis, 1972). Kennedy and his team made three assumptions about the capabilities of Fidel Castro’s administration that proved to be incorrect.

Kennedy’s administration assumed that Castro’s forces were so weak that a small group of U.S. troops could establish a beachhead at the Bay of Pigs. Secondly, the U.S. administration thought that just a fleet of B-26s could knock out Castro’s entire air force. The third assumption was that Castro was not smart enough to stop any internal uprisings.

Kennedy and his team were wrong in all three assumptions because they negatively stereotyped the enemy and made faulty assumptions.

Many members of the group self-censored as well. It seemed as if there was a unanimous decision within the ingroup to continue with the Bay of Pigs invasion, but Rusk failed to voice his contrary opinion even when three government officials outside of the group expressed their concerns.

Pearl Harbor

Despite warning signs, the U.S. government failed to prepare for the attack on Pearl Harbor because they were subject to the illusion of invulnerability (Janis, 1972). They believed they were invincible against any attacks from the Japanese.

The U.S. leaders also rationalized that the Japanese would never dare to attack the U.S. because that would be an act of war, and the U.S. believed they would win and that their opponent viewed this the same.

This stereotype and failure to view the situation from the enemy’s point of view led to the poor decision to not adequately prepare for the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Opposition to the Theory

Despite a lot of support for the theory over the years, it has received some pushback as well. Sally Fuller and Ramon Aldag argue that being in a cohesive group has been proven to be effective (Aldag & Fuller, 1993; Fuller S.R. & Aldag R.J., 1998).

They also argue that Janis’s theory is not empirically supported and can be inconsistent. Robert Baron reflects on the many years of research conducted on groupthink and concludes that the body of evidence has largely failed to support the theory (Baron, 2005).

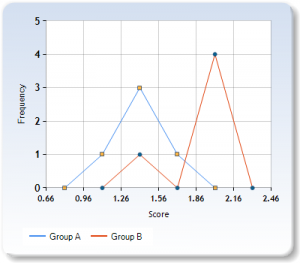

There has been a large body of experimental research conducted on groupthink, especially in the years directly following the introduction of the theory. Notably, one study found mixed support for the theory (Flowers, 1977).

Aligning with the groupthink theory, the groups in the study with directive leaders came up with fewer solutions, shared less information, and utilized fewer facts about the case before making a decision.

On the other hand, the more surprising finding was that the more cohesive groups did not perform worse than the less cohesive ones.

Opposing the group cohesion aspect of the groupthink theory as well, John Courtright found that group cohesion had no effect on a number of factors, including creativity, feasibility, significance, competence, and a number of possible solutions (Courtright, 1978).

Another set of researchers found similar results when it comes to group cohesion (Fodor & Smith, 1982).

Furthermore, both Callaway and Esser reported that both group cohesion and whether or not groups were told to consider all of the possible alternatives or given no instruction had no effect on task performance (Callaway & Esser, 1984).

However, despite the opposition, many researchers have advocated for the theory in their work as well, and groupthink is widely cited today (Hensley & Griffin, 1986; Tetlock, 1979).

Also, many scholars have adjusted the theory to address the opposition’s findings, including the ubiquity model (Baron, 2005), the general group problem-solving model (GGPS) (Aldag & Fuller, 1993), and the sociocognitive theory (Tsoukalas, 2007) to name a few.

How to Avoid Groupthink

To avoid groupthink, leaders and group members alike can take a variety of steps to help prevent the phenomenon from occurring. Some potential solutions are below.

Leaders or impactful group members should create a safe space for discussion. They should be open to opposition to the group consensus, accept criticism, and encourage new ideas regardless of a person’s status within the organization (Janis, 1972, 1982).

Key members of the group and leaders should hold back their opinions initially to reduce their influence over the group consensus.

Outside groups could be set up to work on the same problem to compare potential solutions.

If setting up an entire outside group is not feasible, the ingroup should discuss its ideas with experts outside of the group.

Another way to reduce groupthink is by having a “devil’s advocate” or someone who raises ideas contrary to the ones presented despite their own opinion to help produce debates, create new ideas, or help determine the strength of an existing idea.

Considering the opposing groups’ points of view is key as well.

Groups can be split up into smaller subgroups and asked to create their own possible solutions. These groups can then be reconvened to discuss the various options collectively.

After the group has reached a preliminary decision, the group could hold another meeting which gives group members one more chance to raise opposition to the consensus.

When possible, allow as much time as possible to make a decision.

Educating groups about the groupthink phenomenon can be helpful as well.

Lastly, it’s important to have a diverse set of group members in order to have different perspectives, which can help reach a more balanced, optimal conclusion.

Learning check

Which statement about groupthink is correct?

- Groupthink always occurs in small groups.

- Groupthink helps to maintain peace and avoid conflict within the group.

- Groupthink is a phenomenon where the desire for group consensus leads to the suppression of dissenting viewpoints.

- Groupthink tends to maximize the effectiveness of a team’s performance.

Answer : The correct statement is 3. Groupthink is a phenomenon where the desire for group consensus leads to the suppression of dissenting viewpoints.

Derek’s team is struggling to come to a consensus because several people are unwilling to share their thoughts. What would be the best question for the group to ask themselves to avoid groupthink?

Answer : “Are we creating an environment where everyone feels safe to express their honest opinions and concerns without fear of judgment or backlash?” This encourages open dialogue and reduces the risk of groupthink.

What is groupthink in psychology?

Groupthink in psychology is a phenomenon where the desire for group consensus and harmony leads to poor decision-making.

Members suppress dissenting viewpoints, ignore external views, and may take irrational actions that devalue independent critical thinking.

What causes groupthink?

Groupthink is often caused by group pressure, strong directive leadership, high group cohesion, and isolation from outside opinions.

It is also more likely in stressful situations where decision-making becomes rushed and critical evaluation is minimized.

What are the common results of groupthink?

Common groupthink results include poor decision-making, lack of creativity, ignored alternatives, suppressed dissent, and potentially irrational actions.

It may also lead to overlooking risks, not considering all possible outcomes, and failing to re-evaluate initially rejected options.

Further Information

Lunenburg FC. Group decision making: The potential for groupthink. International Journal of Management, Business, and Administration. 2010;13(1).

Bang, D., & Frith, C. D. (2017). Making better decisions in groups. Royal Society open science, 4(8), 170193.

Rose, J. D. (2011). Diverse perspectives on the groupthink theory–a literary review. Emerging Leadership Journeys, 4(1), 37-57.

Aldag, R. J., & Fuller, S. R. (1993). Beyond Fiasco: A Reappraisal of the Groupthink Phenomenon and a New Model of Group Decision Processes. Psychological Bulletin, 113 (3), 533–552. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.533

Amidon, M. (2005). Groupthink, politics, and the decision to attempt the Son Tay rescue. Parameters (Carlisle, Pa.), 35(3), 119.

Badie, D. (2010). Groupthink, Iraq, and the War on Terror: Explaining US Policy Shift toward Iraq: Groupthink, Iraq, and the War on Terror. Foreign Policy Analysis, 6 (4), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-8594.2010.00113.x

Baron, R. S. (2005). So Right It’s Wrong: Groupthink and the Ubiquitous Nature of Polarized Group Decision Making. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 37, pp. 219–253). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(05)37004-3

Callaway, M. R., & Esser, J. K. (1984). Groupthink: Effects of Cohesiveness and Problem-Solving Procedures on Group Decision Making. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 12 (2), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.1984.12.2.157

Courtright, J. A. (1978). A laboratory investigation of groupthink. Communication Monographs, 45 (3), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637757809375968

Flowers, M. L. (1977). A laboratory test of some implications of Janis’s groupthink hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(12), 888–896. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.35.12.888

Fodor, E. M., & Smith, T. (1982). The power motive as an influence on group decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42 (1), 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.178

Fuller S.R. & Aldag R.J. (1998). Organizational Tonypandy: Lessons from a Quarter Century of the Groupthink Phenomenon. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 73 (23), 163–184.

Hensley, T. R., & Griffin, G. W. (1986). Victims of Groupthink: The Kent State University Board of Trustees and the 1977 Gymnasium Controversy. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 30 (3), 497–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002786030003006

Janis, I. (1971, November). Groupthink. Psychology Today, 84–89.

Janis, I. (1972). Victims of groupthink: A psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascoes (pp. viii, 277). Houghton Mifflin.

Janis, I. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:734003

Orwell, G. (1949). 1984. Signet Classic.

Raven, B. H. (1998). Groupthink, Bay of Pigs, and Watergate reconsidered: Theoretical perspectives on groupthink: a twenty-fifth anniversary appraisal. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 73 (2–3), 352–361.

Scharff, M. M. (2005). WorldCom: A Failure of Moral and Ethical Values. The Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, 10(3), 35-.

Tetlock, P. E. (1979). Identifying victims of groupthink from public statements of decision makers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37 (8), 1314–1324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.8.1314

Tsoukalas, I. (2007). Exploring the Microfoundations of Group Consciousness. Culture & Psychology, 13 (1), 39–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X07073650

Related Articles

Social Science

Hard Determinism: Philosophy & Examples (Does Free Will Exist?)

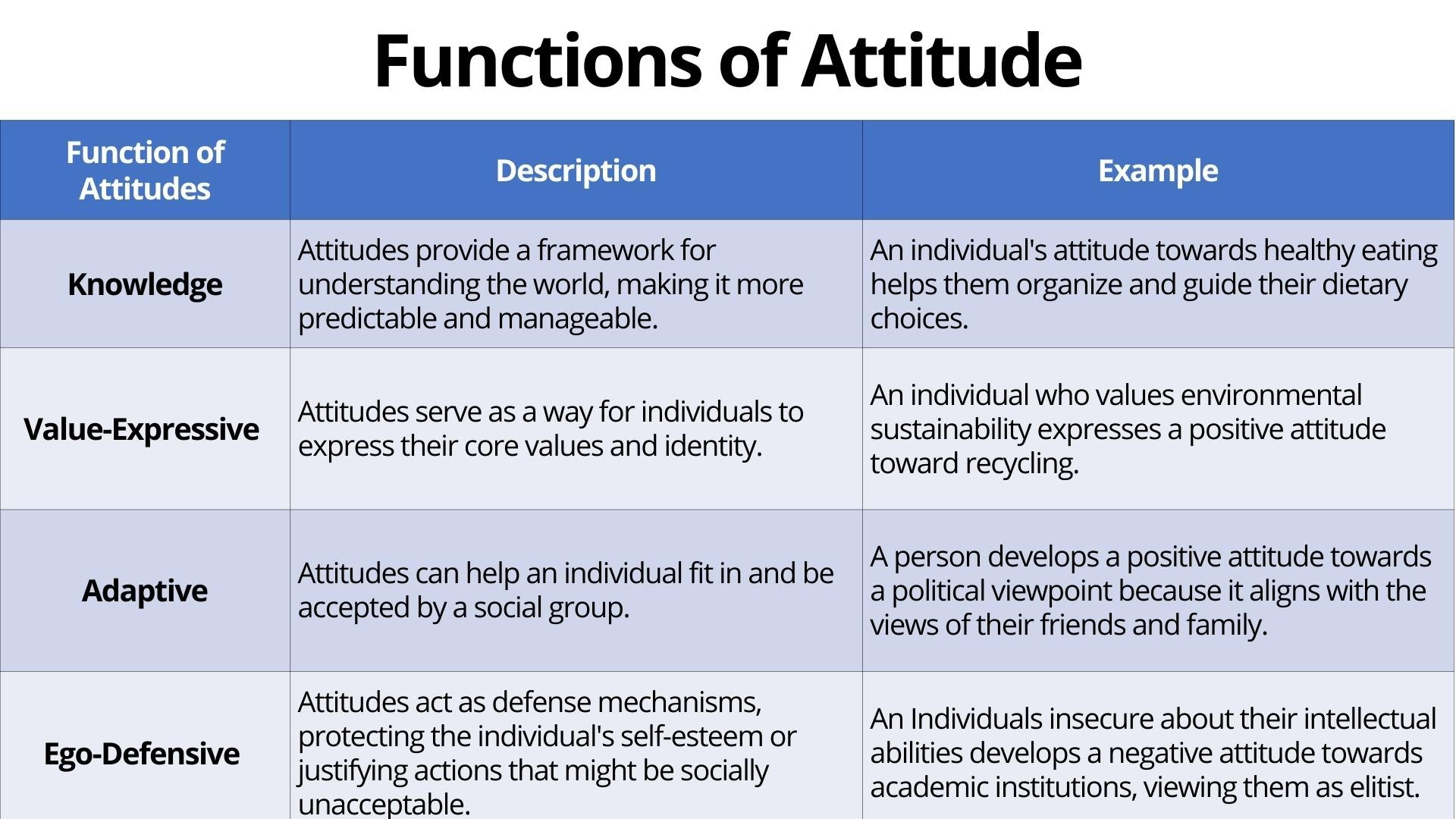

Functions of Attitude Theory

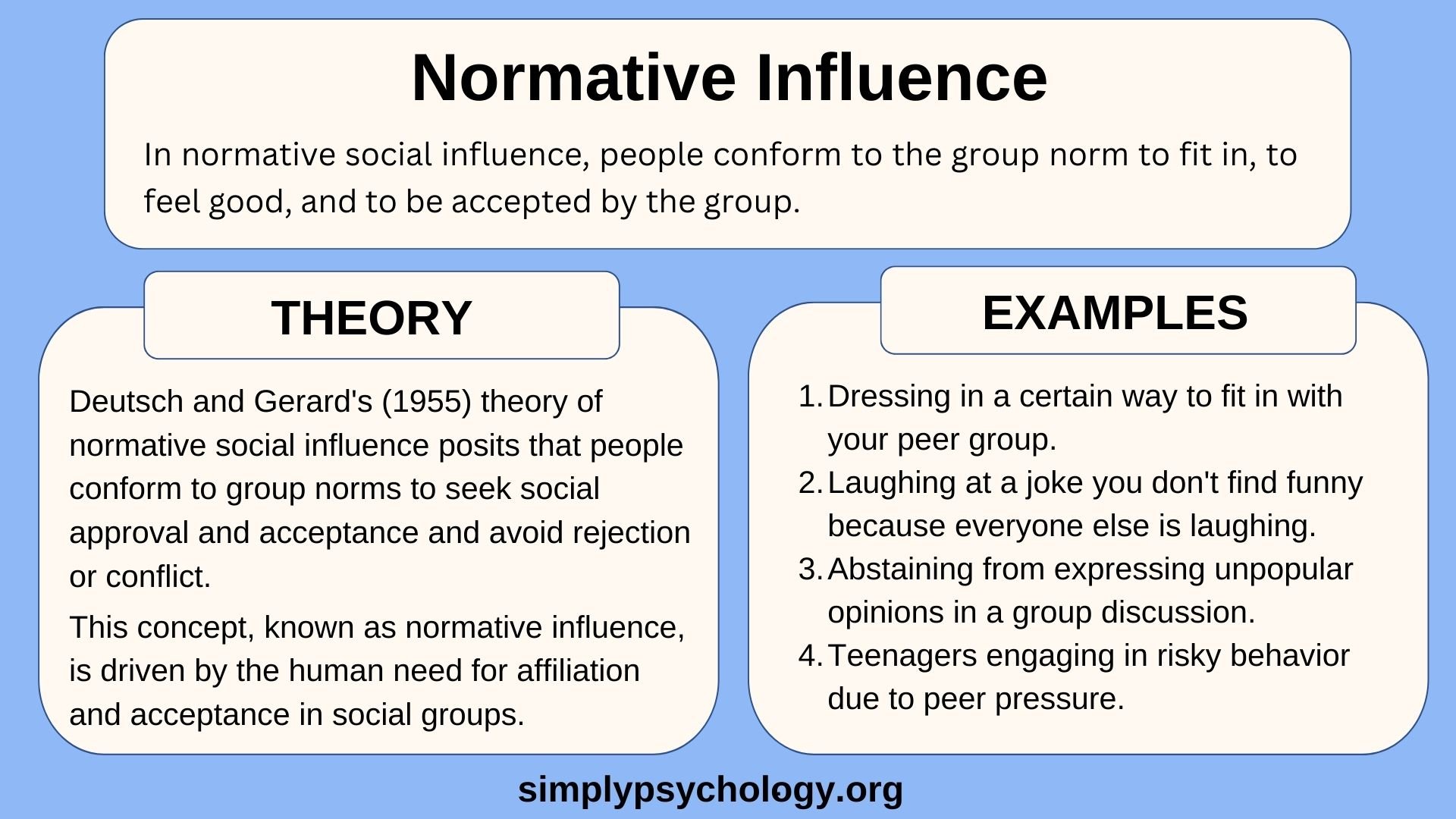

Understanding Conformity: Normative vs. Informational Social Influence

Social Control Theory of Crime

Emotions , Mood , Social Science

Emotional Labor: Definition, Examples, Types, and Consequences

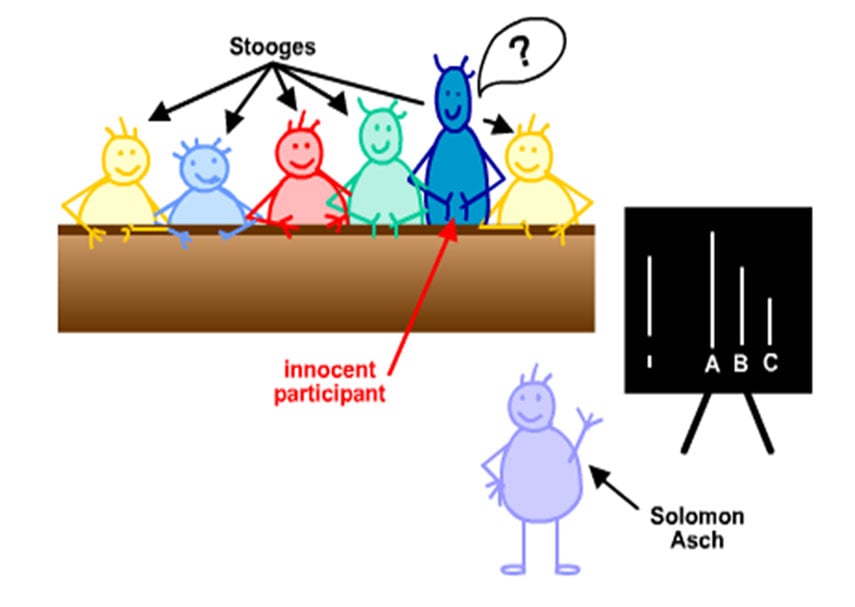

Famous Experiments , Social Science

Solomon Asch Conformity Line Experiment Study

Groupthink among health professional teams in patient care: A scoping review

Affiliations.

- 1 Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- 2 Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, NY, USA.

- 3 Samuel J. Wood Library & C.V. Starr Biomedical Information Center, Weill Cornell Medicine, NY, USA.

- 4 Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD, USA.

- PMID: 34641741

- PMCID: PMC9972224

- DOI: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1987404

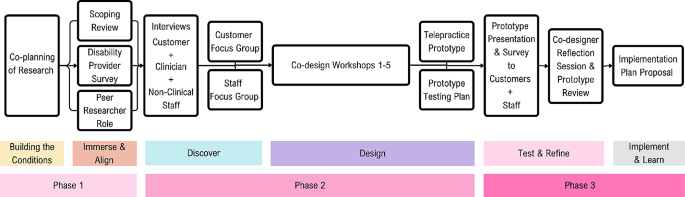

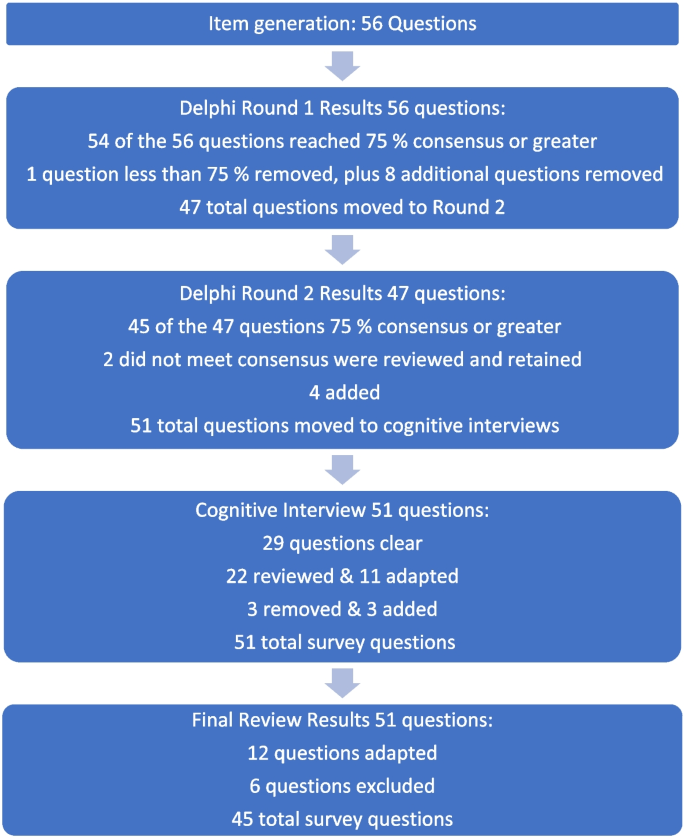

There is emerging interest in understanding group decision making among a team of health professionals. Groupthink , a term coined by Irving Janis to depict premature consensus seeking in highly cohesive groups, is a theory that has been widely discussed in disciplines outside health care. However, it remains unclear how it has been conceptualized, studied, and mitigated in the context of health professionals conducting patient care. This scoping review aimed to examine the conceptualization of groupthink in health care, empirical research conducted in healthcare teams, and recommendations to avoid groupthink. Eight databases were systematically searched for articles focusing on groupthink among health professional teams using a scoping review methodology. A total of 22 articles were included-most were commentaries or narrative reviews with only four empirical research studies. This review found that focus on groupthink and group decision making in medicine is relatively new and growing in interest. Few empirical studies on groupthink in health professional teams have been performed and there is conceptual disagreement on how to interpret groupthink in the context of clinical practice. Future research should develop a theoretical framework that applies groupthink theory to clinical decision making and medical education, validate the groupthink framework in clinical settings, develop measures of groupthink, evaluate interventions that mitigate groupthink in clinical practice, and examine how groupthink may be situated amidst other emerging social cognitive theories of collaborative clinical decision making.

Keywords: Groupthink; errors; group decision making; healthcare team; scoping review.

Publication types

- Decision Making

- Health Personnel*

- Patient Care

- Patient Care Team*

Grants and funding

- KL2 TR002385/TR/NCATS NIH HHS/United States

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

7 Strategies for Better Group Decision-Making

- Torben Emmerling

- Duncan Rooders

What we’ve learned from behavioral science.

There are upsides and downsides to making decisions in a group. The main risks include falling into groupthink or other biases that will distort the process and the ultimate outcome. But bringing more minds together to solve a problem has its advantages. To make use of those upsides and increase the chances your team will land on a successful solution, the authors recommend using seven strategies, which have been backed by behavioral science research: Keep the group small, especially when you need to make an important decision. Bring a diverse group together. Appoint a devil’s advocate. Collect opinions independently. Provide a safe space to speak up. Don’t over-rely on experts. And share collective responsibility for the outcome.

When you have a tough business problem to solve, you likely bring it to a group. After all, more minds are better than one, right? Not necessarily. Larger pools of knowledge are by no means a guarantee of better outcomes. Because of an over-reliance on hierarchy, an instinct to prevent dissent, and a desire to preserve harmony, many groups fall into groupthink .

- Torben Emmerling is the founder and managing partner of Affective Advisory and the author of the D.R.I.V.E.® framework for behavioral insights in strategy and public policy. He is a founding member and nonexecutive director on the board of the Global Association of Applied Behavioural Scientists ( GAABS ) and a seasoned lecturer, keynote speaker, and author in behavioral science and applied consumer psychology.

- DR Duncan Rooders is the CEO of a Single Family Office and a strategic advisor to Affective Advisory . He is a former B747 pilot, a graduate of Harvard Business School’s Owner/President Management program. He is the founder of Behavioural Science for Business (BSB) and an advisor to several international organizations in strategic and team decision-making.”, and a consultant to several international organizations in strategic and financial decision making.

Partner Center

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Groupthink is a phenomenon that occurs when a group of well-intentioned people makes irrational or non-optimal decisions spurred by the urge to conform or the belief that dissent is impossible. The problematic or premature consensus that is characteristic of groupthink may be fueled by a particular agenda—or it may be due to group members valuing harmony and coherence above critical thought.

- Why Groupthink Happens

- Avoiding Groupthink

The term “groupthink” was first introduced in the November 1971 issue of Psychology Today by psychologist Irving Janis. Janis had conducted extensive research on group decision-making under conditions of stress .

Since then, Janis and other researchers have found that in a situation that can be characterized as groupthink, individuals tend to refrain from expressing doubts and judgments or disagreeing with the consensus. In the interest of making a decision that furthers their group cause, members may also ignore ethical or moral consequences. While it is often invoked at the level of geopolitics or within business organizations, groupthink can also refer to subtler processes of social or ideological conformity , such as participating in bullying or rationalizing a poor decision being made by one's friends.

Groups that prioritize their group identity and behave coldly toward “outsiders” may be more likely to fall victim to groupthink. Organizations in which dissent is discouraged or openly punished are similarly likely to engage in groupthink when making decisions. High stress is another root cause, as is time pressure that demands a fast decision.

Even in minor cases, groupthink triggers decisions that aren’t ideal or that ignore critical information. In highly consequential domains—like politics or the military—groupthink can have much worse consequences, leading groups to ignore ethics or morals, prioritize one specific goal while ignoring countless collateral consequences, or, at worst, instigate death and destruction.

Groupthink, by definition, results in a decision that is irrational or dangerous. It is possible, however, for teams to make decisions harmoniously and with little disagreement, in ways that are not necessarily indicative of groupthink. While well-functioning teams can (and should) have some conflict , debate (as long as it's respectful) is antithetical to groupthink.

Groupthink and conformity are related but distinct concepts. Groupthink specifically refers to a process of decision-making; it can be motivated by a desire to conform, but isn’t always. Conformity , on the other hand, pertains to individuals who (intentionally or unintentionally) shift their behaviors, appearances, or beliefs to sync up to those of the group.

Risky or disastrous military maneuvers, such as the escalation of the Vietnam War or the invasion of Iraq, are commonly cited as instances of groupthink. In Janis’ original article, he highlighted groupthink during the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion .

To recognize groupthink, it's useful to identify the situations in which it's most likely to occur. When groups feel threatened—either physically or through threats to their identity —they may develop a strong “us versus them” mentality. This can prompt members to accept group perspectives, even when those perspectives don’t necessarily align with their personal views. Groupthink may also occur in situations in which decision-making is rushed—in some cases, with destructive outcomes.

To minimize the risk, it's critical to allow enough time for issues to be fully discussed, and for as many group members as possible to share their thoughts. When dissent is encouraged, groupthink is less likely to occur. Learning about common cognitive biases, as well as how to identify them, may also reduce the likelihood of groupthink.

Individual members of the group self-censoring —especially if they fear being shunned or derided for speaking their mind—is one potential sign that the group may engage in groupthink. If those who do dissent are pressured to recant or conform to the majority view, it may similarly signal groupthink. Groups that actively deride “outsiders” may be more likely to fall prey.

Since groupthink often occurs because group members fear disagreeing with the leader , it can be beneficial for the leader to temporarily step back and allow members to debate the issue themselves. One member of the team can be appointed as “devil’s advocate,” who will argue against the consensus to highlight potential flaws.

Healthy dissent has been linked to more creative thinking and ultimately greater innovation within organizations . Asking one person to deliberately play devil’s advocate and argue with the solutions proposed by the majority is one strategy that has been shown to be effective against groupthink.

Diversity—both demographic diversity and diversity of thought— has been shown to reduce the possibility of groupthink . Group members’ different backgrounds, beliefs, or personality traits can all spawn unique ideas that can inspire innovation. It’s critical, though, that all group members—regardless of their position or demographics—be allowed to contribute to group decision-making.

Organizations that want to support critical thinking, creativity , and innovation should first foster a culture where dissent is allowed and encouraged. They should reward risk-taking , be open to ideas from all group members—regardless of their experience or position—and create regular opportunities for individuals to share their ideas , big and small.

Here’s a way to understand how attachment and bonding in infancy shape one’s sense of self, degree of emotional security, and capacity for independent thinking.

Conspiracy theories seem to be everywhere nowadays—but believing in them can be bad for your physical and mental health. Here's what to know when you talk to a true believer.

Humans have been engaging in tribalistic "us versus them" behavior for millennia. These dynamics are responsible for a great deal of human suffering. How do we move past them?

Despite groupthink’s negative connotations, it can have beneficial aspects in some complex, urgent, and high-stakes project environments.

Polish Nobel Laureate Czesław Miłosz wrote "The Captive Mind" in 1953 as an exploration of the psyche under Soviet oppression. What can it teach us about movements like MAGA today?

What if the quality of the education your child receives largely comes down to luck? This is an idea proposed by Dr. David Steiner in his new book.

Here’s how to improve your critical thinking—enabling you to make better everyday decisions while helping you make sense of an increasingly complex and confusing world.

Five ways algorithms in social media might be affecting how we relate to each other.

Hundreds have perished during their selfie sessions. What’s going on?

Are we becoming an increasingly divided society with a growing distrust of “the other side”? Read on to learn about 3 levels of polarization and strategies to overcome this trend.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Groupthink Impacts Our Behavior

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Yuri Arcurs / Getty Images

How Groupthink Works

Examples of groupthink, impact of groupthink, potential pitfalls, tips for avoiding groupthink.

Groupthink is a psychological phenomenon in which people strive for consensus within a group. In many cases, people will set aside their own personal beliefs or adopt the opinion of the rest of the group. The term was first used in 1972 by social psychologist Irving L. Janis.

People opposed to the decisions or overriding opinions of the group frequently remain quiet, preferring to keep the peace rather than disrupt the uniformity of the crowd. The phenomenon can be problematic, but even well-intentioned people are prone to making irrational decisions in the face of overwhelming pressure from the group.

Signs of Groupthink

Groupthink may not always be easy to discern, but there are some signs that it is present. There are also some situations where it may be more likely to occur. Janis identified a number of different "symptoms" that indicate groupthink.

- Illusions of unanimity lead members to believe that everyone is in agreement and feels the same way. It is often much more difficult to speak out when it seems that everyone else in the group is on the same page.

- Unquestioned beliefs lead members to ignore possible moral problems and not consider the consequences of individual and group actions.

- Rationalizing prevents members from reconsidering their beliefs and causes them to ignore warning signs.

- Stereotyping leads members of the in-group to ignore or even demonize out-group members who may oppose or challenge the group's ideas. This causes members of the group to ignore important ideas or information.

- Self-censorship causes people who might have doubts to hide their fears or misgivings. Rather than sharing what they know, people remain quiet and assume that the group must know best.

- "Mindguards" act as self-appointed censors to hide problematic information from the group. Rather than sharing important information, they keep quiet or actively prevent sharing.

- Illusions of invulnerability lead members of the group to be overly optimistic and engage in risk-taking. When no one speaks out or voices an alternative opinion, it causes people to believe that the group must be right.

- Direct pressure to conform is often placed on members who pose questions, and those who question the group are often seen as disloyal or traitorous.

Four of the main characteristics of groupthink include pressure to conform, the illusion of invulnerability, self-censorship, and unquestioned beliefs.

Why does groupthink occur? Think about the last time you were part of a group, perhaps during a school project. Imagine that someone proposes an idea that you think is quite poor.

However, everyone else in the group agrees with the person who suggested the idea, and the group seems set on pursuing that course of action. Do you voice your dissent or do you just go along with the majority opinion?

In many cases, people end up engaging in groupthink when they fear that their objections might disrupt the harmony of the group or suspect that their ideas might cause other members to reject them .

A number of factors can influence this psychological phenomenon. Some causes:

- Group identity : It tends to occur more in situations where group members are very similar to one another. When there is strong group identity, members of the group tend to perceive their group as correct or superior while expressing disdain or disapproval toward people outside of the group.

- Leader influences : Groupthink is also more likely to take place when a powerful and charismatic leader commands the group.

- Low knowledge : When people lack personal knowledge of something or feel that other members of the group are more qualified, they are more likely to engage in groupthink.

- Stress : Situations where the group is placed under extreme stress or where moral dilemmas exist also increase the occurrence of groupthink.

Contributing Factors

Janis suggested that groupthink tends to be the most prevalent in conditions:

- When there is a high degree of cohesiveness.

- When there are situational factors that contribute to deferring to the group (such as external threats, moral problems, difficult decisions).

- When there are structural issues (such as group isolation and a lack of impartial leadership ).

Groupthink has been attributed to many real-world political decisions that have had consequential effects. In his original descriptions of groupthink, Janis suggested that the escalation of the Vietnam War, the Bay of Pigs invasion, and the failure of the U.S. to heed warnings about a potential attack on Pearl Harbor were all influenced by groupthink.

Other examples where decision-making is believed to be heavily influenced by groupthink include:

- The Watergate scandal

- The Challenger space shuttle disaster

- The 2003 invasion of Iraq

- The 2008 economic crisis

- Internet cancel culture

In more everyday settings, researchers suggest that groupthink might play a part in decisions made by professionals in healthcare settings.

In each instance, factors such as pressure to conform, closed-mindedness, feelings of invulnerability, and the illusion of group unanimity contribute to poor decisions and often devastating outcomes.

Groupthink can cause people to ignore important information and can ultimately lead to poor decisions . This can be damaging even in minor situations but can have much more dire consequences in certain settings. Medical, military, or political decisions, for example, can lead to unfortunate outcomes when they are impaired by the effects of groupthink.

The phenomenon can have high costs. These include:

- The suppression of individual opinions and creative thought can lead to inefficient problem-solving .

- It can contribute to group members engaging in self-censorship. This tendency to seek consensus above all else also means that group members may not adequately assess the potential risks and benefits of a decision.

- Groupthink also tends to lead group members to perceive the group as inherently moral or right. Stereotyped beliefs about other groups can contribute to this biased sense of rightness.

Groupthink vs. Conformity

It is important to note that while groupthink and conformity are similar and related concepts, there are important distinctions between the two. Groupthink involves the decision-making process.

On the other hand, conformity is a process in which people change their own actions so they can fit in with a specific group. Conformity can sometimes cause groupthink, but it isn't always the motivating factor.

While groupthink can generate consensus, it is by definition a negative phenomenon that results in faulty or uninformed thinking and decision-making. Some of the problems it can cause include:

- Blindness to potentially negative outcomes

- Failure to listen to people with dissenting opinions

- Lack of creativity

- Lack of preparation to deal with negative outcomes

- Ignoring important information

- Inability to see other solutions

- Not looking for things that might not yet be known to the group

- Obedience to authority without question

- Overconfidence in decisions

- Resistance to new information or ideas

Group consensus can allow groups to make decisions, complete tasks, and finish projects quickly and efficiently—but even the most harmonious groups can benefit from some challenges. Finding ways to reduce groupthink can improve decision-making and assure amicable relationships within the group.

There are steps that groups can take to minimize this problem. First, leaders can give group members the opportunity to express their own ideas or argue against ideas that have already been proposed.

Breaking up members into smaller independent teams can also be helpful. Here are some more ideas that might help prevent groupthink.

- Initially, the leader of the group should avoid stating their opinions or preferences when assigning tasks. Give people time to come up with their own ideas first.

- Assign at least one individual to take the role of the "devil's advocate."

- Discuss the group's ideas with an outside member in order to get impartial opinions.

- Encourage group members to remain critical. Don't discourage dissent or challenges to the prevailing opinion.

- Before big decisions, leaders should hold a "second-chance" meeting where members have the opportunity to express any remaining doubts.

- Reward creativity and give group members regular opportunities to share their ideas and thoughts.

- Assign specific roles to certain members of the group.

- Establish metrics or definitions to make sure that everyone is basing decisions or judgments on the same information.

- Consider allowing people to submit anonymous comments, suggestions, or opinions.

Diversity among group members has also been shown to enhance decision-making and reduce groupthink.

When people in groups have diverse backgrounds and experiences, they are better able to bring different perspectives, information, and ideas to the table. This enhances decisions and makes it less likely that groups will fall into groupthink patterns.

Lunenburg FC. Group decision making: The potential for groupthink . International Journal of Management, Business, and Administration. 2010;13(1).

Bang D, Frith CD. Making better decisions in groups . R Soc Open Sci . 2017;4(8):170193. doi:10.1098/rsos.170193

Rose JD. Diverse perspectives on the groupthink theory - A literary review . Emerging Leadership Journeys . 2011;4(1):37-57.

DiPierro K, Lee H, Pain KJ, Durning SJ, Choi JJ. Groupthink among health professional teams in patient care: A scoping review . Med Teach . 2022;44(3):309-318. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2021.1987404

Gokar H. Groupthink principles and fundamentals in organizations . Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business. 2013;5(8):225-240.

Janis IL. Victims of Groupthink: A Psychological Study of Foreign-Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin; 1972.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

10 Groupthink Examples (Plus Definition & Critique)

Groupthink is a type of thinking when members of a group accept the group consensus uncritically. It can lead to disastrous conclusions because moral and logical thinking is suspended.

Group members often take the group’s competence and unity for granted, thereby failing to use their own individual thought. Alternatively, they might not want to avoid punishments associated with expressing dissent.

Groupthink might lead groups to reach more extreme or wrong decisions that only some members genuinely support.

Groupthink Definition and Theoretical Origins

The term “groupthink” was coined in 1952 by William Whyte to describe the perils of “rationalized conformity”.

However, American psychologist Irving Janis introduced the comprehensive theory of groupthink in 1972.

It emerged from his effort to understand why knowledgeable political groups often made disastrous decisions (especially in foreign policy). Janis defined groupthink as:

“…the mode of thinking that persons engage in when concurrence seeking becomes so dominant in a cohesive ingroup that it tends to override realistic appraisal of alternative courses of action.” (1972, p. 9)

Essentially, a lack of conflict or opposing viewpoints leads to poor decisions. The group doesn’t fully analyse possible alternatives, gather external information, or seek external advice to make an informed decision.

Groupthink then has negative effects. It marks “a deterioration of mental efficiency, reality testing, and moral judgment that results from ingroup pressures” (Janis, 1972, p. 9).

Key Characteristics of Groupthink

According to Janis, the key characteristics of groupthink are:

- The illusion that a group is invulnerable, fully competent, and coherent

- The rationalization of collective decisions

- An unquestioned belief in the group’s integrity,

- Stereotyping group adversaries or outsiders,

- The existence of “mindguards” blocking alternative information and options which leads to belief perseverance ,

- Self-censorship

10 Groupthink Examples

Real-world examples.

- American officials did not anticipate or adequately prepare for the Pearl Harbor bombing in 1941. They ignored external information that the Japanese were planning an attack, thinking they would never dare to fight the American “superpower”.

- The escalation of the Vietnam War in the 1960s resulted from the U.S. government’s feelings of invincibility, underestimating the opponent’s abilities, and ignoring opposing viewpoints.

- The Challenger disaster. In 1986, miscalculations regarding the launch of the Challenger shuttle claimed the lives of 7 people. Space shuttle engineers knew about the shuttle’s faulty parts but they did not block the launch because of public pressure.

- The Bay of Pigs invasion . Suffering from the illusion of invulnerability and based on faulty assumptions the Kennedy administration launched an unsuccessful attack against Cuba.

- A homogenous (yet experienced) team of American decisionmakers decided to go to war in Iraq . Their illusion of invulnerability and moral righteousness led them to disregard intelligence information about weapons of mass destruction.

Fictional examples

- Employees not speaking up in a work meeting because they don’t want to seem unsupportive of their team’s efforts.

- Students not opposing to a strict professor’s views or behavior because they’re concerned about how this might affect their grades.

- A political organization has a firm ideological agenda. Their sources of information are limited to those aligned with their ideology. This group might come to distrust and even inflict violence on outgroup members with different political views.

- Members of a close-knit group might ignore or underestimate information that challenges their decisions. They might try to shut down any group member who brings a different perspective.

- Launching an offensive advertising campaign for a consumer product because employees don’t articulate their dissent. They were worried about how this could impact their career. However, their view could save the company/organization from making a mistake.

Case Studies

1. the challenger disaster.

In the 1980s, NASA earlier debuted a space shuttle program that would be accessible to the public. They have even planned for more than 50 affordable flights a year.

The first shuttle, name Challenger was planned to take off in January 1986. Space shuttle engineers knew about certain faulty parts before the take-off.

And yet, they did not block the launch because of public pressure to proceed. In its effort to avoid negative press, NASA’s Challenger mission claimed seven lives—while the nation was watching.

2. The Bay of Pigs invasion

A famous example of Groupthink is the ultimately unsuccessful attack against Cuba in 1961.

The J. F. Kennedy administration launched the attack by accepting negative stereotypes about the Cubans and Fidel Castro’s incompetence (Janis, 1972). They did not question whether the Central Intelligence Agency information was accurate.

Beyond stereotyping, Kennedy’s administration thought itself untouchable. Although the plans to invade the Bay of Pigs had leaked out, they carried on ignoring the adverse warning signs (Janis, 1972).

Also, individual members, like Secretary of State Dean Rusk, did not voice their contrary opinion in group discussions.

The Bay of Pigs Invasion showcases three characteristics of groupthink: (i) the illusion of invulnerability , (ii) stereotyping of the opponent and (iii) self-censorship .

3. The bombing of Pearl Harbour

Another real-life scenario of groupthink discussed by Janis is the bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941.

Japanese messages had been intercepted. And yet, many senior officials at Pearl Harbor did not pay attention to the warnings from Washington DC about a potential Japanese attack.

They didn’t act or prepare because they rationalised that the Japanese wouldn’t never attempt such an invasion. They were sure that the Japanese would see the “obvious” futility of entering a war with the US.

Thus, they failed to prepare for the bombing of Pearl Harbour, which claimed many lives.

The symptoms of groupthink are: (i) stereotyping the adversary’s ineptitude, (ii) illusions of invincibility leading to excessive risk taking (Janis, 1972),.

4. The escalation of the Vietnam War

The escalation of the Vietnam War was also studied by Janis as a manifestation of dysfunctional group dynamics .

First, U.S. government officials during the war considered themselves untouchable despite having suffered multiple failures and financial/human losses. They ignored the dangers and negative feedback, blindly trusting the military advantage of the U.S.

They also stereotyped their enemies, deeming them unable to make correct decisions.

President Johnson felt that the U.S. was leading a “just war”, defending its ally, South Vietnam, from the Soviet threat. They saw the escalation of war as morally correct.

The ultimate purpose was to show to the rest of the world the unanimity of the Americans in fighting again Communist expansionism.

5. An offensive marketing campaign

A modern example of Groupthink is a politically incorrect marketing campaign, imagine a company seeking to launch a new marketing campaign for a consumer product. Other team members appear excited about and pleased with the campaign, but you have some concerns. You feel it might be offensive to some demographic groups.

You don’t speak up because you like your colleagues and want to avoid putting them in an awkward position by challenging their idea. You also want your team to succeed. Anyway no one seems to consider other possible marketing plans, while the dynamic team leader firmly pushes for this campaign.

At that point, you choose to go along with the group and start doubting that your idea is correct. This fictional example illustrates key symptoms of groupthink: (i) group cohesion , (ii) self – censorship , (ii) the “ mindguard ” (team leader) banning alternative opinions .

Causes of Groupthink

It should be clear from the above that the main causes of groupthink are:

- Highly cohesive and/or non-diverse groups

- An influential leader who feels “infallible” and suppresses dissenting information

- Decision-making under stress or time constraints

- Non-consideration of outside perspectives

- Efforts to maintain/boost group members’ self-confidence

Criticisms of Groupthink Theory

Despite the significant uptake of Janis’ Groupthink model in the social sciences, many scholars have criticized its validity (Kramer, 1998). Scholars have found that decision-making processes only sometimes define ultimate outcomes.

Not all poor group decisions result from groupthink. Similarly, not all cases of groupthink result in failures or ‘fiascoes’ to use Janis’ wording. In some cases, scholars have found that being in a cohesive group can be effective; it can boost members’ self-esteem and speed up decision-making (Fuller & Aldag, 1998).

Indeed, previous research has challenged Janis’ model. However, groupthink has been very influential in understanding group dynamics and poor decision-making processes in a much broader range of settings than initially imagined (Forsyth, 1990).

Groupthink is a process in which the motivation for consensus in a group causes poor decisions—made by knowledgeable people.

Instead of expressing dissent and risking losing a sense of group unity, members stay silent. They subscribe to views/decisions they disagree with. Therefore, groupthink prioritizes group harmony over independent judgment and might rationalize immoral actions.

Although groupthink often leads to bad (even unethical) decisions, group leaders should try avoid groupthink by creating diverse and inclusive groups, enabling members to voice their views without fear, and considering opposing views seriously.

Forsyth, D. (1990). Group dynamics (2nd ed.). Pacific Grove, Calif: Brooks/Cole.

Fuller S.R, & Aldag R.J. (1998). Organizational Tonypandy: Lessons from a Quarter Century of the Groupthink Phenomenon. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 73(23), 163-184.

Janis, I. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes (2nd ed.). Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin.

Kramer, R. M. (1998). Revisiting the Bay of Pigs and Vietnam Decisions 25 Years Later: How Well Has the Groupthink Hypothesis Stood the Test of Time?. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 73(2-3), pp. 236-271.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Animism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Magical Thinking Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Social-Emotional Learning (Definition, Examples, Pros & Cons)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is Educational Psychology?

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Do Your Students Know How to Analyze a Case—Really?

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Student Engagement

J ust as actors, athletes, and musicians spend thousands of hours practicing their craft, business students benefit from practicing their critical-thinking and decision-making skills. Students, however, often have limited exposure to real-world problem-solving scenarios; they need more opportunities to practice tackling tough business problems and deciding on—and executing—the best solutions.

To ensure students have ample opportunity to develop these critical-thinking and decision-making skills, we believe business faculty should shift from teaching mostly principles and ideas to mostly applications and practices. And in doing so, they should emphasize the case method, which simulates real-world management challenges and opportunities for students.

To help educators facilitate this shift and help students get the most out of case-based learning, we have developed a framework for analyzing cases. We call it PACADI (Problem, Alternatives, Criteria, Analysis, Decision, Implementation); it can improve learning outcomes by helping students better solve and analyze business problems, make decisions, and develop and implement strategy. Here, we’ll explain why we developed this framework, how it works, and what makes it an effective learning tool.

The Case for Cases: Helping Students Think Critically

Business students must develop critical-thinking and analytical skills, which are essential to their ability to make good decisions in functional areas such as marketing, finance, operations, and information technology, as well as to understand the relationships among these functions. For example, the decisions a marketing manager must make include strategic planning (segments, products, and channels); execution (digital messaging, media, branding, budgets, and pricing); and operations (integrated communications and technologies), as well as how to implement decisions across functional areas.

Faculty can use many types of cases to help students develop these skills. These include the prototypical “paper cases”; live cases , which feature guest lecturers such as entrepreneurs or corporate leaders and on-site visits; and multimedia cases , which immerse students into real situations. Most cases feature an explicit or implicit decision that a protagonist—whether it is an individual, a group, or an organization—must make.

For students new to learning by the case method—and even for those with case experience—some common issues can emerge; these issues can sometimes be a barrier for educators looking to ensure the best possible outcomes in their case classrooms. Unsure of how to dig into case analysis on their own, students may turn to the internet or rely on former students for “answers” to assigned cases. Or, when assigned to provide answers to assignment questions in teams, students might take a divide-and-conquer approach but not take the time to regroup and provide answers that are consistent with one other.

To help address these issues, which we commonly experienced in our classes, we wanted to provide our students with a more structured approach for how they analyze cases—and to really think about making decisions from the protagonists’ point of view. We developed the PACADI framework to address this need.

PACADI: A Six-Step Decision-Making Approach

The PACADI framework is a six-step decision-making approach that can be used in lieu of traditional end-of-case questions. It offers a structured, integrated, and iterative process that requires students to analyze case information, apply business concepts to derive valuable insights, and develop recommendations based on these insights.

Prior to beginning a PACADI assessment, which we’ll outline here, students should first prepare a two-paragraph summary—a situation analysis—that highlights the key case facts. Then, we task students with providing a five-page PACADI case analysis (excluding appendices) based on the following six steps.

Step 1: Problem definition. What is the major challenge, problem, opportunity, or decision that has to be made? If there is more than one problem, choose the most important one. Often when solving the key problem, other issues will surface and be addressed. The problem statement may be framed as a question; for example, How can brand X improve market share among millennials in Canada? Usually the problem statement has to be re-written several times during the analysis of a case as students peel back the layers of symptoms or causation.

Step 2: Alternatives. Identify in detail the strategic alternatives to address the problem; three to five options generally work best. Alternatives should be mutually exclusive, realistic, creative, and feasible given the constraints of the situation. Doing nothing or delaying the decision to a later date are not considered acceptable alternatives.

Step 3: Criteria. What are the key decision criteria that will guide decision-making? In a marketing course, for example, these may include relevant marketing criteria such as segmentation, positioning, advertising and sales, distribution, and pricing. Financial criteria useful in evaluating the alternatives should be included—for example, income statement variables, customer lifetime value, payback, etc. Students must discuss their rationale for selecting the decision criteria and the weights and importance for each factor.

Step 4: Analysis. Provide an in-depth analysis of each alternative based on the criteria chosen in step three. Decision tables using criteria as columns and alternatives as rows can be helpful. The pros and cons of the various choices as well as the short- and long-term implications of each may be evaluated. Best, worst, and most likely scenarios can also be insightful.

Step 5: Decision. Students propose their solution to the problem. This decision is justified based on an in-depth analysis. Explain why the recommendation made is the best fit for the criteria.

Step 6: Implementation plan. Sound business decisions may fail due to poor execution. To enhance the likeliness of a successful project outcome, students describe the key steps (activities) to implement the recommendation, timetable, projected costs, expected competitive reaction, success metrics, and risks in the plan.

“Students note that using the PACADI framework yields ‘aha moments’—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.”

PACADI’s Benefits: Meaningfully and Thoughtfully Applying Business Concepts

The PACADI framework covers all of the major elements of business decision-making, including implementation, which is often overlooked. By stepping through the whole framework, students apply relevant business concepts and solve management problems via a systematic, comprehensive approach; they’re far less likely to surface piecemeal responses.

As students explore each part of the framework, they may realize that they need to make changes to a previous step. For instance, when working on implementation, students may realize that the alternative they selected cannot be executed or will not be profitable, and thus need to rethink their decision. Or, they may discover that the criteria need to be revised since the list of decision factors they identified is incomplete (for example, the factors may explain key marketing concerns but fail to address relevant financial considerations) or is unrealistic (for example, they suggest a 25 percent increase in revenues without proposing an increased promotional budget).

In addition, the PACADI framework can be used alongside quantitative assignments, in-class exercises, and business and management simulations. The structured, multi-step decision framework encourages careful and sequential analysis to solve business problems. Incorporating PACADI as an overarching decision-making method across different projects will ultimately help students achieve desired learning outcomes. As a practical “beyond-the-classroom” tool, the PACADI framework is not a contrived course assignment; it reflects the decision-making approach that managers, executives, and entrepreneurs exercise daily. Case analysis introduces students to the real-world process of making business decisions quickly and correctly, often with limited information. This framework supplies an organized and disciplined process that students can readily defend in writing and in class discussions.

PACADI in Action: An Example

Here’s an example of how students used the PACADI framework for a recent case analysis on CVS, a large North American drugstore chain.

The CVS Prescription for Customer Value*

PACADI Stage

Summary Response

How should CVS Health evolve from the “drugstore of your neighborhood” to the “drugstore of your future”?

Alternatives

A1. Kaizen (continuous improvement)

A2. Product development

A3. Market development

A4. Personalization (micro-targeting)

Criteria (include weights)

C1. Customer value: service, quality, image, and price (40%)

C2. Customer obsession (20%)

C3. Growth through related businesses (20%)

C4. Customer retention and customer lifetime value (20%)

Each alternative was analyzed by each criterion using a Customer Value Assessment Tool

Alternative 4 (A4): Personalization was selected. This is operationalized via: segmentation—move toward segment-of-1 marketing; geodemographics and lifestyle emphasis; predictive data analysis; relationship marketing; people, principles, and supply chain management; and exceptional customer service.

Implementation

Partner with leading medical school

Curbside pick-up

Pet pharmacy

E-newsletter for customers and employees

Employee incentive program

CVS beauty days

Expand to Latin America and Caribbean

Healthier/happier corner

Holiday toy drives/community outreach

*Source: A. Weinstein, Y. Rodriguez, K. Sims, R. Vergara, “The CVS Prescription for Superior Customer Value—A Case Study,” Back to the Future: Revisiting the Foundations of Marketing from Society for Marketing Advances, West Palm Beach, FL (November 2, 2018).

Results of Using the PACADI Framework

When faculty members at our respective institutions at Nova Southeastern University (NSU) and the University of North Carolina Wilmington have used the PACADI framework, our classes have been more structured and engaging. Students vigorously debate each element of their decision and note that this framework yields an “aha moment”—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.

These lively discussions enhance individual and collective learning. As one external metric of this improvement, we have observed a 2.5 percent increase in student case grade performance at NSU since this framework was introduced.

Tips to Get Started

The PACADI approach works well in in-person, online, and hybrid courses. This is particularly important as more universities have moved to remote learning options. Because students have varied educational and cultural backgrounds, work experience, and familiarity with case analysis, we recommend that faculty members have students work on their first case using this new framework in small teams (two or three students). Additional analyses should then be solo efforts.

To use PACADI effectively in your classroom, we suggest the following:

Advise your students that your course will stress critical thinking and decision-making skills, not just course concepts and theory.

Use a varied mix of case studies. As marketing professors, we often address consumer and business markets; goods, services, and digital commerce; domestic and global business; and small and large companies in a single MBA course.

As a starting point, provide a short explanation (about 20 to 30 minutes) of the PACADI framework with a focus on the conceptual elements. You can deliver this face to face or through videoconferencing.

Give students an opportunity to practice the case analysis methodology via an ungraded sample case study. Designate groups of five to seven students to discuss the case and the six steps in breakout sessions (in class or via Zoom).

Ensure case analyses are weighted heavily as a grading component. We suggest 30–50 percent of the overall course grade.

Once cases are graded, debrief with the class on what they did right and areas needing improvement (30- to 40-minute in-person or Zoom session).

Encourage faculty teams that teach common courses to build appropriate instructional materials, grading rubrics, videos, sample cases, and teaching notes.

When selecting case studies, we have found that the best ones for PACADI analyses are about 15 pages long and revolve around a focal management decision. This length provides adequate depth yet is not protracted. Some of our tested and favorite marketing cases include Brand W , Hubspot , Kraft Foods Canada , TRSB(A) , and Whiskey & Cheddar .

Art Weinstein , Ph.D., is a professor of marketing at Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He has published more than 80 scholarly articles and papers and eight books on customer-focused marketing strategy. His latest book is Superior Customer Value—Finding and Keeping Customers in the Now Economy . Dr. Weinstein has consulted for many leading technology and service companies.

Herbert V. Brotspies , D.B.A., is an adjunct professor of marketing at Nova Southeastern University. He has over 30 years’ experience as a vice president in marketing, strategic planning, and acquisitions for Fortune 50 consumer products companies working in the United States and internationally. His research interests include return on marketing investment, consumer behavior, business-to-business strategy, and strategic planning.

John T. Gironda , Ph.D., is an assistant professor of marketing at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. His research has been published in Industrial Marketing Management, Psychology & Marketing , and Journal of Marketing Management . He has also presented at major marketing conferences including the American Marketing Association, Academy of Marketing Science, and Society for Marketing Advances.

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Home » Business » 25 Most Famous Groupthink Examples in History and Pop Culture

25 Most Famous Groupthink Examples in History and Pop Culture

What is groupthink? This concept was first spoken about by social psychologist Irving Janis and journalist William H. Whyte. According to them, it’s a phenomenon where members of a group begin to think erroneously.

This happens because group members want to keep a feeling of overall unity and/or harmony within the group, and this leads to dissenting voices being silenced. Unfortunately, it also leads to a situation where team members end up making poor decisions. To make this easier to understand, here is a deeper explanation and some real-world examples of groupthink.

Top Characteristics of Groupthink

- An illusion of invulnerability

- An illusion of unanimity

- Pressure to conform

- Closed mindedness

- Isolation of the group

- Pressure to self-censor

Best Known Examples of Groupthink

1. the bay of pigs invasion.

As mentioned, the theory of groupthink was first spoken about by Yale psychologist Irving Janis. He wrote about this phenomenon in the 1972 publication titled Victims of Groupthink a Psychological Study of Foreign-policy Decisions and Fiascoes. In this book, he provides the reader with several examples of poor group decision-making.

One of these examples is the Bay of Pigs Invasion. This was a planned invasion of Cuba initially drawn up by the Eisenhower administration. Once President Kennedy came into power, the plan was immediately put into action.

The government did this without questioning the basic assumptions of this plan and without undertaking any further investigation. The invasion ended up being an enormous failure, and people directly blamed the Kennedy administration. What’s also interesting to note is that this event paved the way for the Cuban Missile Crisis.

2. The Pearl Harbor Attack

This is an excellent example of groupthink theory. Weeks before the attack, hundreds of communications were intercepted from Japan. These communications confirmed that an attack was imminent. Despite this, the Pearl Harbor command didn’t actually believe that the Japanese would attack. Why would they risk war with a much stronger enemy?

The command was also more concerned with Japanese citizens living in Hawaii – who they believed were a far bigger threat to Pearl Harbor. As we now know, the United States’ decision to ignore this critical information proved was an immense disaster.

3. The Challenger Space Shuttle Disaster

Here’s another famous example of groupthink. Engineers of the space shuttle repeatedly voiced concerns about the safety of the Challenger. Despite this, group leaders within NASA choose to ignore these warnings.

This was mostly because they wanted to launch the shuttle on schedule. More specifically, it was because members of the team who designed the shuttle felt that the testing efforts were adequate.

4. Kony 2012 Viral Video

Kony 2012 was a documentary that focused on Ugandan war criminal and militia leader Joseph Kony. The purpose of this film was supposedly to start an international movement that would bring him to justice. The movie was highly successful and quickly went viral. It spread like wildfire over social media and had millions of views within days. In fact, it was actually the first video in the history of YouTube to break one million views.

In spite of this success, it was later discovered that most of the information in the film was incorrect. When this news hit the headlines, it proved to have dire consequences for the people behind the film (some were even arrested.) Not only was Kony 2012 a stunning example of the theory of groupthink in action, but it also shows how easily social networks can manipulate the public.

5. Insolvency of Swissair

The Swiss national carrier was once renowned for its financial stability. Due to high levels of liquidity, it was even known as the “flying bank.” During the 1990s, things started to change. Overconfidence and hubris led to a series of bad decisions, which eventually caused the airline to collapse.