- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality – An Overview

Rising income inequality is one of the greatest challenges facing advanced economies today. Income inequality is multifaceted and is not the inevitable outcome of irresistible structural forces such as globalisation or technological development. Instead, this review shows that inequality has largely been driven by a multitude of political choices. The embrace of neoliberalism since the 1980s has provided the key catalyst for political and policy changes in the realms of union regulation, executive pay, the welfare state and tax progressivity, which have been the key drivers of inequality. These preventable causes have led to demonstrable harmful outcomes that are not explicable solely by material deprivation. This review also shows that inequality has been linked on the economic front with reduced growth, investment and innovation, and on the social front with reduced health and social mobility, and greater violent crime.

1 Introduction

Income inequality has recently come to be viewed as one of the greatest challenges facing the world today. In recent years, the topic has dominated the agenda of the World Economic Forum (WEF), where the world’s top political and business leaders attend. Their global risks report, drawn from over 700 experts in attendance, pronounced inequality to be the greatest threat to the world economy in 2017 ( Elliott 2017 ). Likewise, the past decade has seen leading global figures such as former American President Barack Obama, Pope Francis, Chinese President Xi Jinping, and the former head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Christine Lagarde, all undertake speeches on the gravity of income inequality and the need to address its rise. This is because, as this research note shows, income inequality engenders harmful consequences that are not explicable solely by material deprivation.

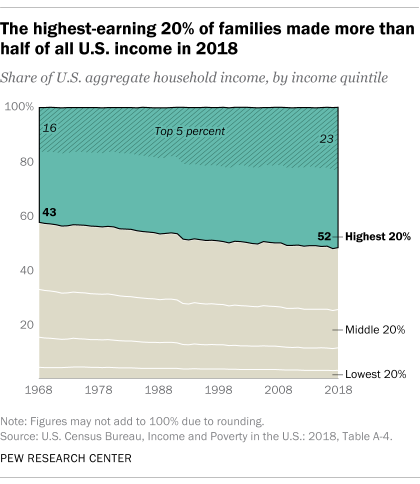

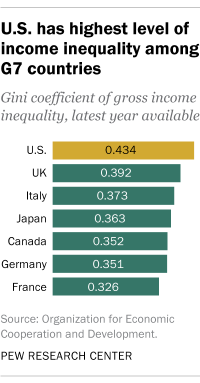

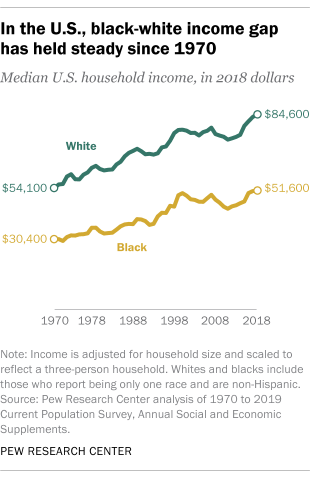

The general dynamics of income inequality include a tendency to rise slowly and fluctuate over time. For instance, Japan had one of the highest rates in the world prior to the Second World War and the United States (US) one of the lowest, which has since completely reversed for both. The United Kingdom (UK) was also the second most equitable large European country in the 1970s but is now the most inequitable ( Dorling 2018 : 27–28).

High rates of inequality are rarely sustained for long periods because they tend to lead to or become punctuated by man-made disasters that lead to a levelling out. Scheidel (2017) posits that there in fact exists a violent ‘Four Horseman of Leveling’ (mass mobilisation warfare, transformation revolutions, state collapse, and lethal pandemics) for inequality, which have at times dramatically reduced inequalities because they can lead to the alteration of existing power structures or wipe out the wealth of elites and redistribute their resources. For instance, the pronounced shocks of the two world wars led to the ‘Great Compression’ of income throughout the West in the post-war years. There is already some evidence that the current global pandemic caused by the novel Coronavirus, has led to greater aversion to income inequality ( Asaria, Costa-Font, and Cowell 2021 ; Wiwad et al. 2021 ).

Thus, greater aversion to inequality has been able to reduce inequality in the past, this is because, as this review also shows, income inequality does not result exclusively from efficient market forces but arises out of a set of rules that is shaped by those with political power. Inequality’s rise is not inevitable, nor beyond the control of governments and policymakers, as they can affect distributional outcomes and inequality through public policy.

It is the purpose of this review to outline the causes and consequences of income inequality. The paper begins with an analysis of the key structural and institutional determinants of inequality, followed by an examination into the harmful outcomes of inequality. It then concludes with a discussion of what policymakers can do to arrest the rise of inequality.

2 Causes of Income Inequality

Broadly speaking, explanations for the increase in income inequality have largely been classified as either structural or institutional. Historically, economists emphasised structural causes of increasing income inequality, with globalisation and technological change at the forefront. However, in recent years opinion has shifted to emphasise more institutional political factors to do with the adoption of neoliberal reforms such as privatisation, deregulation and tax and welfare reductions since the early 1980s. They were first embraced and most heavily championed by the UK and US, spreading globally later, and which provide the crucial catalysts of rising income inequality ( Atkinson 2015 ; Brown 2017 ; Piketty 2020 ; Stiglitz 2013 ). I discuss each of these key factors in turn.

2.1 Globalisation

One of the earliest, and most prominent explanations for the rise of income inequality emphasised the role of globalisation ( Borjas, Freeman, and Katz 1992 ; Revenga 1992 ). Globalisation has led to the offshoring of many goods and services that used to be produced or completed domestically in the West, which has created downward pressures on the wages of lower skilled workers. According to the ‘market forces hypothesis,’ increasing inequality is a response to the rising demand for skills at the top, in which the spread of globalisation and technological progress have been facilitated through reduced barriers to trade and movement.

Proponents of globalisation as the leading cause of inequality have argued that globalisation has constrained domestic state choices and left governments collectively powerless to address inequality. Detractors admit that globalisation has indeed had deep structural effects on Western economies but its impact on the degree of agency available to domestic governments has been mediated by individual policy choices ( Thomas 2016 : 346). A key problem with attributing the cause of inequality to globalisation, is that the extent of the inequality increase has varied considerably across countries, even though they have all been exposed to the same effects of globalisation. The US also has the highest inequality amongst rich countries, but it is less reliant on international trade than most other developed countries ( Brown 2017 : 56). Moreover, a recent meta-analysis by Heimberger (2020) found that globalisation has a “small-to-moderate” inequality-increasing effect, with financial globalisation displaying the largest impact.

2.2 Technology

A related explanation for inequality draws attention to the impact of technology specifically. The advent of the digital age has placed a higher premium on the skills needed for non-routine work and reduced the value placed on lower skilled routine work, as it has enabled machines to replace jobs that could be routinised. This skill-biased technological change (SBTC) has led to major changes in the organisation of work, as many full-time permanent jobs with benefits have given way to part-time flexible work without benefits, that are often centred around the completion of short ‘gigs’ such as a car journey or food delivery. For instance, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimated in 2015 that since the 1990s, roughly 60% of all job creation has been in the form of non-standard work due to technological changes and that those employed in such jobs are more likely to be poor ( Brown 2017 : 60).

Relatedly, a prevailing doctrine in economics is ‘marginal productivity theory,’ which holds that people with greater productivity levels will earn higher incomes. This is due to the belief that a person’s productivity is equated to their societal contribution ( Stiglitz 2013 : 37). Since technology is a leading determinant in the productivity of different skills and SBTC has led to increased productivity, it has also become a justification for inequality. However, it is very difficult to separate any one person’s contribution to society from that of others, as even the most successful businessperson owes their success to the rule of law, good infrastructure, and a state educated workforce ( Stiglitz 2013 : 97–98).

Further criticisms of the SBTC explanation, are that there was still substantial SBTC when inequality first fell dramatically and then stabilised in the period from 1930 to 1980, and it has failed to explain the perpetuation of both the gender and racial wage gap, “or the dramatic rise in education-related wage gaps for younger versus older workers” ( Brown 2017 : 67). Although it is difficult to decouple globalisation and technology, as they each have compounding tendencies, it is most likely that globalisation and technology are important explanatory factors for inequality, but predominantly facilitate and underlie the following more determinant institutional factors that happen to be already present, such as reduced tax progressivity, rising executive pay, and union decline. It is to these factors that I now turn.

2.3 Tax Policy

Taxes overwhelmingly comprise the primary source of revenue that governments can use for redistribution, which is fundamental to alleviating income inequality. Redistribution is defended on economic grounds because the marginal utility of money declines as income rises, meaning that the benefit derived from extra income is much higher for the poor than the rich. However, since the late 1970s, a major rethinking surrounding redistributive policy occurred. This precipitated ‘trickle-down economics’ theory achieving prominence amongst American and British policymakers, whereby the benefits from tax cuts on the wealthy would trickle-down to everyone. Subsequently, expert opinion has determined that tax cuts do not actually spur economic growth ( CBPP 2017 ).

Personal income tax progressivity has declined sharply in the West, as the average top income tax rate for OECD members fell from 62% in 1981 to 35% in 2015 ( IMF 2017 : 11). However, the decline has been most pronounced in the UK and the US, which had top rates of around 90% in the 1960s and 1970s. Corporate tax rates have also plummeted by roughly one half across the OECD since 1980 ( Shaxson 2015 : 4). Recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) research found that between 1985 and 1995, redistribution through the tax system had offset 60% of the increase in market inequality but has since failed to respond to the continuing increase in inequality ( IMF 2017 ). Moreover, in a sample of 18 OECD countries encompassing 50 years, Hope and Limberg (2020) found that tax reforms even significantly increased pre-tax income inequality, while having no significant effect on economic growth.

This decline in tax progressivity has been a leading cause of rising income inequality, which has been compounded by the growing problem of tax avoidance. A complex global web of shell corporations has been constructed by international brokers in offshore tax havens that is able to keep wealth hidden from tax collectors. The total hidden amount in tax havens is estimated to be $7.6 trillion US dollars and rising, or roughly 8% of total global household wealth ( Zucman 2015 : 36). Recent research has revealed that tax havens are overwhelmingly used by the immensely rich ( Alstadsæter, Johannesen, and Zucman 2019 ), thus taxing this wealth would substantially reduce income inequality and increase revenue available for redistribution. The massive reduction in income tax progressivity in the Anglo world, after it had been amongst its leaders in the post-war years, also “probably explains much of the increase in the very highest earned incomes” since 1980 ( Piketty 2014 : 495–496).

2.4 Executive Pay

The enormous rising pay of executives since the 1980s, has also fuelled income inequality and more specifically the gap between executives and their employees. For example, the gap between Chief Executive Officers (CEO) and their workers at the 500 leading US companies in 2016, was 335 times, which is nearly 10 times larger than in 1980. It is a similar story in the UK, with a pay ratio of 131 for large British firms, which has also risen markedly since 1980 ( Dorling 2017 ).

Piketty (2014 : 335) posits that the dramatic reduction in top income tax has had an amplifying effect on top executives pay since it provides them with much greater incentive to seek larger remuneration, as far less is then taken in tax. It is difficult to objectively measure an individual’s contribution to a company and with the onset of trickle-down economics and accompanying business-friendly climate since the 1980s, top executives have found it relatively easy to convince boards of their monetary worth ( Gabaix and Landier 2008 ).

The rise in executive pay in both the UK and US, is far larger than the rest of the OECD. This may partially be explained by the English-speaking ‘superstar’ theory, whereby the global market demand for top CEOs is much higher for native English speakers due to English being the prime language of the global economy ( Deaton 2013 : 210). Saez and Veall (2005) provide support for the theory in a study of the top 1% of earners from the Canadian province of Quebec, which showed that English speakers were able to increase their income share over twice as much as their French-speaking counterparts from 1980 to 2000. This upsurge of income at the top of the labour market has been accompanied by stagnation or diminishing returns for the middle and lower parts of the labour market, which has been affected by the dramatic decline of union influence throughout the West.

2.5 Union Decline

Trade unions have typically been viewed as an important force for moderating income inequality. They “contribute to wage compression by restricting wage decline among low-wage earners” and restrain wage surges among high-wage earners ( Checchi and Visser 2009 : 249). The mere presence of unions can also drive up the wages of non-union employees in similar industries, as employers tend to give in to wage demands to keep unions out. Union density has also been proven to be strongly associated with higher redistribution both directly and indirectly, through its influence on left party governments ( Haddow 2013 : 403).

There had broadly existed a ‘social contract’ between labour and business, whereby collective bargaining establishes a wage structure in many industries. However, this contract was abandoned by corporate America in the mid-1970s when large-scale corporate donations influenced policymakers to oppose pro-union reform of labour law, leading to political defeats for unions ( Hacker and Pierson 2010 : 58–59). The crackdown of strikes culminating in the momentous Air Traffic Controllers’ strike (1981) in the US and coal miner’s strike (1984–85) in the UK, caused labour to become de-politicised, which was self-reinforcing, because as their political power dispersed, policymakers had fewer incentives to protect or strengthen union regulations ( Rosenfeld and Western 2011 ). Consequently, US union density has plummeted from around a third of the workforce in 1960, down to 11.9% last decade, with the steepest decline occurring in the 1980s ( Stiglitz 2013 : 81).

Although the decline in union density is not as steep cross-nationally, the pattern is still similar. Baccaro and Howell (2011 : 529) found that on average the unionisation rate decreased by 0.39% a year since 1974 for the 15 OECD members they surveyed. Increasingly, the decline in the fortunes of labour is being linked with the increase in inequality and the sharpest increases in income inequality have occurred in the two countries with the largest falls in union density – the UK and US. Recent studies have found that the weakening of organised unions accounts for between a third and a fifth of the total rise in income inequality in the US ( Rosenfeld and Western 2011 ), and nearly one half of the increase in both the Gini rate and the top 10%’s income share amongst OECD members ( Jaumotte and Buitron 2015 ).

To illustrate the changing relationship between inequality and unionisation, Figure 1 displays a local polynomial smoother scatter plot of union density by income inequality, for 23 OECD countries, 1980–2018. They are negatively correlated, as countries with higher union density have much lower levels of income inequality. Figure 2 further plots the time trends of both. Income inequality (as measured via the Gini coefficient) has climbed over 0.02 percentage points on average in these countries since 1980, which is roughly a one-tenth rise. Whereas union density has fallen on average from 44 to 35 percentage points, which is over one-fifth.

Gini coefficient by union density, OECD 1980–2018. Data on Gini coefficients from SWIID ( Solt 2020 ); data on union density from ICTWSS Database ( Visser 2019 ).

Gini coefficient by union density, 1980–2018. Data on Gini coefficients from SWIID ( Solt 2020 ); data on union density from ICTWSS Database ( Visser 2019 ).

In sum, income inequality is multifaceted and is not the inevitable outcome of irresistible structural forces such as globalisation or technological development. Instead, it has largely been driven by a multitude of political choices. Tridico (2018) finds that the increases in inequality from 1990 to 2013 in 26 OECD countries, was largely owing to increased financialisation, deepening labour flexibility, the weakening of trade unions and welfare state retrenchment. While Huber, Huo, and Stephens (2019) recently reveals that top income shares are unrelated to economic growth and knowledge-intensive production but is closely related to political and policy changes surrounding union density, government partisanship, top income tax rates, and educational investment. Lastly, Hager’s (2020) recent meta-analysis concludes that the “empirical record consistently shows that government policy plays a pivotal role” in shaping income inequality.

These preventable causes that have given rise to inequality have created socio-economic challenges, due to the demonstrably negative outcomes that inequality engenders. What follows is a detailed analysis of the significant mechanisms that income inequality induces, which lead to harmful outcomes.

3 Consequences of Income Inequality

Escalating income inequality has been linked with numerous negative outcomes. On the economic front, negative results transpire beyond the obvious poverty and material deprivation that is often associated with low incomes. Income inequality has also been shown to reduce growth, innovation, and investment. On the social front, Wilkinson and Pickett’s ground-breaking The Spirit Level ( 2009 ), found that societies that are more unequal have worse social outcomes on average than more egalitarian societies. They summarised an extensive body of research from the previous 30 years to create an Index of Health and Social Problems, which revealed a host of different health and social problems (measuring life expectancy, infant mortality, obesity, trust, imprisonment, homicide, drug abuse, mental health, social mobility, childhood education, and teenage pregnancy) as being positively correlated with the level of income inequality across rich nations and across states within the US. Figure 3 displays the cross-national findings via a sample of 21 OECD countries.

Index of health and social problems by Gini coefficient. Data on health and social problems index from The Equality Trust (2018) ; data on Gini coefficients from OECD (2020) .

3.1 Economic

Income inequality is predominantly an economic subject. Therefore, it is understandable that it can engender pervasive economic outcomes. Foremost economically speaking, it has been linked with reduced growth, investment and innovation. Leading international organisations such as the IMF, World Bank and OECD, pushed for neoliberal reforms beginning in the 1980s, although they have recently started to substantially temper their views due to their own research into inequality. A 2016 study by IMF economists, noted that neoliberal policies have delivered benefits through the expansion of global trade and transfers of technology, but the resulting increases in inequality “itself undercut growth, the very thing that the neo-liberal agenda is intent on boosting” ( Ostry, Loungani, and Furceri 2016 : 41). Cingano’s (2014) OECD cross-national study, found that once a country’s income inequality reaches a certain level it reduces growth. The growth rate in these countries would have been one-fifth higher had income inequality not increased, while the greater equality of the other countries included in the study helped to increase their growth rates.

Consumer spending is good for economic growth but rising income inequality shifts more money to the top of the income distribution, where higher income individuals have a much smaller propensity to consume than lower-income individuals. The wealthy save roughly 15–25% of their income, whereas low income individuals spend their entire income on consumer goods and services ( Stiglitz 2013 : 106). Therefore, greater inequality reduces demand in an economy and is a major contributor to the ‘secular stagnation’ (persistent insufficient demand relative to aggregate private savings) that the largest Western economies have been experiencing since the financial crisis. Inequality also increases the level of debt, as lower-income individuals borrow more to maintain their standard of living, especially in a climate of low interest rates. Combined with deregulation, greater debt increases instability and “was a major contributor to, if not the underlying cause of, the 2008 financial crash” ( Brown 2017 : 35–36).

Another key economic effect of income inequality is that it leads to reduced welfare spending and public investment. Since a greater share of the income distribution is earned by the very wealthy, governments have less income available to fund education, public amenities, and other services that the poor rely heavily on. This creates social separation, whereby the wealthy opt out in publicly funding services because their private equivalents are of better quality. This causes a cycle of increasing income inequality that is likely to eventually lead to a situation of “private affluence and public squalor” ( Marmot 2015 : 39).

Lastly, it has been proven that economic instability is a by-product of increasing inequality, which harms innovation. Both countries and American states with the highest inequality have been found to be the least innovative in terms of the amount of Intellectual Property (IP) patents they produce ( Dorling 2018 : 129–130). Although income inequality is predominantly an economic subject, its effects are so pervasive that it has also been linked to a host of negative health and societal outcomes.

Wilkinson and Pickett found key associations between income inequality for both physical and mental health. For example, they discovered that on average the life expectancy gap is more than four years between the least and most equitable richest nations (Japan and the US). Since their revelations, overall life expectancy has been reported to be declining in the US ( Case and Deaton 2020 ). It has held or declined every year since 2014, which has led to a cumulative drop of 1.13 years ( Andrasfay and Goldman 2021 ). Marmot (2015) has provided evidence that there exists a social gradient whereby differences in affluence translate into increasing health inequalities, which can be shown even down to the neighbourhood level, as more affluent areas have higher life expectancy on average than deprived areas, and a clear gradient appears where life expectancy increases in line with affluence.

Moreover, Marmot’s famous Whitehall studies, which are large-scale longitudinal studies of Whitehall employees of UK central government, found an inverse-relationship between salary grade and ill-health, whereby low-grade workers were four times as likely as high-grade workers to suffer from ill-health ( 2015 : 11). Health steadily improves with rank and the correlation is little affected by lifestyle controls such as tobacco and alcohol usage. However, the leading factor that seems to make the most difference in ill-health is job stress and a person’s sense of control over their work, including the variety of work and the use and development of skills ( Schrecker and Bambra 2015 : 54–55).

‘Psychosocial stresses,’ like those appearing in the Whitehall studies, have been found to be more common and frequent amongst low-income individuals, beyond just the workplace ( Jensen and van Kersbergen 2017 : 24). Wilkinson and Pickett (2019) posit that greater income inequality engenders low self-esteem, chronic stress and depression, stemming from status anxiety. This occurs because more importance is placed on where people fit in a hierarchy with greater inequality. For evidence, they outline a clear relationship of a much higher percentage of the population suffering from mental illness in more unequal countries. Meticulous research has shown that huge inequalities in income result in the poor having feelings of shame across a range of environments. Furthermore, Dickerson and Kemeny’s (2004) meta-analysis of 208 studies found that stress-hormone (cortisol) levels were raised particularly “when people felt that others were making negative judgements about them” ( Rowlingson 2011 : 24).

These effects on both mental and physical health can be best illustrated via the ‘absolute income’ and ‘relative income’ hypotheses ( Daly, Boyce, and Wood 2015 ). The relative income hypothesis posits that when an individual’s income is held constant, the relative income of others can affect a person’s health depending on how they view themselves in comparison to those above them ( Wilkinson 1996 ). This pattern also holds when income inequality increases at the societal level, because if such changes lead to increases in chronic stress, it can increase ill-health nationally. Whereas the absolute income hypothesis predicts that health gains from an extra unit of income diminish as an individual’s income rises ( Kawachi, Adler, and Dow 2010 ). A mean preserving transfer from a richer to poorer individual raises the health of the poorer individual more than it lowers the health of the richer person. This occurs because there is an optimum threshold of income required to maintain good health. Thus, when holding total income constant, a more equal distribution of income should improve overall population health. This pattern also applies at the country-wide level, as the “effect of income on health appears substantial as countries move from about $15,000 to 25,000 US dollars per capita,” but appears non-existent beyond that point ( Leigh, Jencks, and Smeeding 2009 : 386–387).

Income inequality also impacts happiness and wellbeing, as the happiest nations are routinely the ones with low inequality, such as Denmark and Norway. Happiness has been proven to be affected by the law of diminishing returns in economics. It states that higher income incrementally improves happiness but only up to a certain point, as any individual income earned beyond roughly $70,000 US dollars, does not bring about greater happiness ( Deaton 2013 : 53). The negative physical and mental health outcomes that income inequality provoke, also impact key societal areas such as crime, social mobility and education.

Rates of violent crime are lower in more equal countries ( Hsieh and Pugh 1993 ; Whitworth 2012 ). This is largely because more equal countries have less poverty, which leads to less people being desperate about their situation, as lower-income individuals have been shown to commit more crime. Relatedly, according to strain theory, more unequal societies place higher social value in achieving economic success, while providing lower means to achieve it ( Merton 1938 ). This generates strain, which may lead more individuals to pursue crime as a means of attaining financial success. At the opposite end of the income spectrum, the wealthy in more equal countries are also less likely to exploit others and commit fraud or exhibit other anti-social behaviour, partly because they feel less of a need to cut corners to get ahead, or to make money ( Dorling 2017 : 152–153). Homicides also tend to rise with inequality. Daly (2016) reveals that inequality predicts homicide rates better than any other variable and accounts for around half of the variance in murder rates between countries and American states. Roughly 90% of American homicides are committed by men, and since the majority of homicides occur over status, inequality raises the stakes of disputes over status amongst men.

Studies have also shown that there is a marked negative relationship between income inequality and social mobility. Utilising Intergenerational Earnings Elasticity data from Blanden, Gregg, and Machin (2005) , Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) first outline this relationship cross-nationally for eight OECD countries. Corak (2013) famously expanded on this with his ‘Great Gatsby Curve’ for 22 countries using the same measure. I update and expand on these studies in Figure 4 to include all 36 OECD members, utilising the WEF’s inaugural 2020 Social Mobility Index. It clearly shows that social mobility is much lower on average in more unequal countries across the entire OECD.

Index of social mobility by Gini coefficient. Data on social mobility index from World Economic Forum (2020) ; data on Gini coefficients from SWIID ( Solt 2020 ).

A primary driver for the negative relationship between inequality and social mobility, derives from the availability of resources during early childhood. Life chances have been shown to be determined in early childhood to a disproportionately large extent ( Jensen and van Kersbergen 2017 : 29). Children in more equitable regions such as Scandinavia, have better access to resources, as they go to similar schools, receive similar educational opportunities, and have access to a wider range of career options. Whereas in the UK and US, a greater number of jobs at the top are closed off to those at the bottom and affluent parents are far more likely to send their children to private schools and fund other ‘child enrichment’ goods and services ( Dorling 2017 : 26). Therefore, as income inequality rises, there is a greater disparity in the resources that rich and poor parents can invest in their children’s education, which has been shown to substantially affect “cognitive development and school achievement” ( Brown 2017 : 33–34).

4 Conclusions

The causes and consequences of income inequality are multifaceted. Income inequality is not the inevitable outcome of irresistible structural forces such as globalisation or technological development. Instead, it has largely been driven by a multitude of institutional political choices. These preventable causes that have given rise to inequality have created socio-economic challenges, due to the demonstrably negative outcomes that inequality engenders.

The neoliberal political consensus poses challenges for policymakers to arrest the rise of income inequality. However, there are many proven solutions that policymakers can enact if the appropriate will can be summoned. Restoring higher levels of labour protections would aid in reversing the declining trend of labour wage share. Similarly, government promotion and support for new corporate governance models that give trade unions and workers a seat at the table in ownership decisions through board memberships, would somewhat redress the increasing power imbalance between capital and labour that is generating more inequality. Greater regulation aimed at limiting the now dominant shareholder principle of maximising value through share buy-backs and instead offering greater incentives to pursue maximisation of stakeholder value, long-term financial stability and investment, can reduce inequality. Most importantly, tax policy can be harnessed to redress income inequality. Such policies include restoring higher marginal income and corporate tax rates, setting higher corporate tax rates for firms with higher ratios of CEO-to-worker pay, and establishing luxury taxes on spiralling compensation packages. Finally, a move away from austerity, which has gripped the West since the financial crisis, and a move towards much greater government investment and welfare state spending, would also lift growth and low-wages.

Alstadsæter, A., N. Johannesen, and G. Zucman. 2019. “Tax Evasion and Inequality.” American Economic Review 109 (6): 2073–103. 10.3386/w23772 Search in Google Scholar

Andrasfay, T., and N. Goldman. 2021. “Reductions in 2020 US Life Expectancy Due to COVID-19 and the Disproportionate Impact on the Black and Latino Populations.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (5), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2014746118 . Search in Google Scholar

Asaria, M., J. Costa-Font, and F. A. Cowell. 2021. “How Does Exposure to Covid-19 Influence Health and Income Inequality Aversion.” IZA Discussion Paper. no. 14103. Also available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3785067 . 10.2139/ssrn.3907733 Search in Google Scholar

Atkinson, A. B. 2015. Inequality: What Can Be Done? London: Harvard University Press. 10.4159/9780674287013 Search in Google Scholar

Baccaro, L., and C. Howell. 2011. “A Common Neoliberal Trajectory: The Transformation of Industrial Relations in Advanced Capitalism.” Politics & Society 39 (4): 521–63, https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329211420082 . Search in Google Scholar

Blanden, J., P. Gregg, and S. Machin. 2005. Intergenerational Mobility in Europe and North America . London: Centre for Economic Performance. 10.1017/CBO9780511492549.007 Search in Google Scholar

Borjas, G. J., R. B. Freeman, and L. F. Katz. 1992. “On the Labor Market Effects of Immigration and Trade.” In Immigration and the Workforce , edited by G. J. Borjas, and R. B. Freeman, 213–44. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 10.3386/w3761 Search in Google Scholar

Brown, R. 2017. The Inequality Crisis: The Facts and What We Can Do About It . Bristol: Polity Press. 10.2307/j.ctt22p7kb5 Search in Google Scholar

Case, A., and A. Deaton. 2020. Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism . Princeton: Princeton University Press. 10.1515/9780691217062 Search in Google Scholar

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) . 2017. Tax Cuts for the Rich Aren’t an Economic Panacea – and Could Hurt Growth. Also available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/tax-cuts-for-the-rich-arent-an-economic-panacea-and-could-hurt-growth . Search in Google Scholar

Checchi, D., and J. Visser. 2009. “Inequality and the Labor Market: Unions.” In The Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality , edited by B. Nolan, W. Salverda, and T. M. Smeeding, 230–56. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Search in Google Scholar

Cingano, F. 2014. Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth . OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 163. Paris: OECD Publishing. Search in Google Scholar

Corak, M. 2013. “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (3): 79–102, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.27.3.79 . Search in Google Scholar

Daly, M. 2016. Killing the Competition: Economic Inequality and Homicide . Oxford: Routledge. 10.4324/9780203787748 Search in Google Scholar

Daly, M., C. Boyce, and A. Wood. 2015. “A Social Rank Explanation of How Money Influences Health.” Health Psychology 34 (3): 222–30, https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000098 . Search in Google Scholar

Deaton, A. 2013. The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality . Princeton: Princeton University Press. 10.1515/9781400847969 Search in Google Scholar

Dickerson, S. S., and M. Kemeny. 2004. “Acute Stressors and Cortisol Responses: A Theoretical Integration and Synthesis of Laboratory Research.” Psychological Bulletin 130 (3): 355–91, https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355 . Search in Google Scholar

Dorling, D. 2017. The Equality Effect: Improving Life for Everyone . Oxford: New Internationalist Publications Ltd. Search in Google Scholar

Dorling, D. 2018. Do We Need Economic Inequality? Cambridge: Polity Press. Search in Google Scholar

Elliott, L. 2017. “Rising Inequality Threatens World Economy, Says WEF.” The Guardian. Also available at https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/jan/11/inequality-world-economy-wef-brexit-donald-trump-world-economic-forum-risk-report . Search in Google Scholar

Gabaix, X., and A. Landier. 2008. “Why Has CEO Pay Increased So Much?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 123 (1): 49–100, https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.1.49 . Search in Google Scholar

Hacker, J. S., and P. Pierson. 2010. Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer – And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class . New York: Simon & Schuster. Search in Google Scholar

Haddow, R. 2013. “Labour Market Income Transfers and Redistribution.” In Inequality and the Fading of Redistributive Politics , edited by K. Banting, and J. Myles, 381–412. Vancouver: UBC Press. Search in Google Scholar

Hager, S. 2020. “Varieties of Top Incomes?” Socio-Economic Review 18 (4): 1175–98. 10.1093/ser/mwy036 Search in Google Scholar

Heimberger, P. 2020. “Does Economic Globalisation Affect Income Inequality? A Meta‐analysis.” The World Economy 43 (11): 2960–82, https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13007 . Search in Google Scholar

Hope, D., and J. Limberg. 2020. The Economic Consequences of Major Tax Cuts for the Rich . London: London School of Economics and Political Science. Also available at http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/107919/ . Search in Google Scholar

Hsieh, C.-C., and M. D. Pugh. 1993. “Poverty, Inequality and Violent Crime: a Meta-Analysis of Recent Aggregate Data Studies.” Criminal Justice Review 18 (2): 182–202, https://doi.org/10.1177/073401689301800203 . Search in Google Scholar

Huber, E., J. Huo, and J. D. Stephens. 2019. “Power, Policy, and Top Income Shares.” Socio-Economic Review 17 (2): 231–53, https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwx027 . Search in Google Scholar

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2017. Fiscal Monitor: Tackling Inequality . Washington: IMF. Search in Google Scholar

Jaumotte, F., and C. O. Buitron. 2015. “Power from the People.” Finance & Development 52 (1): 29–31. Search in Google Scholar

Jensen, C., and K. Van Kersbergen. 2017. The Politics of Inequality . London: Palgrave. 10.1057/978-1-137-42702-1 Search in Google Scholar

Kawachi, I., N. E. Adler, and W. H. Dow. 2010. “Money, Schooling, and Health: Mechanisms and Causal Evidence.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186 (1): 56–68, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05340.x . Search in Google Scholar

Leigh, A., C. Jencks, and T. Smeeding. 2009. “Health and Economic Inequality.” In The Oxford Book of Economic Equality , edited by W. Salverda, B. Nolan, and T. Smeeding, 384–405. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199606061.013.0016 Search in Google Scholar

Marmot, M. 2015. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World . London: Bloomsbury. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00150-6 Search in Google Scholar

Merton, R. 1938. “Social Structure and Anomie.” American Sociological Review 3 (5): 672–82, https://doi.org/10.2307/2084686 . Search in Google Scholar

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) . 2020. “Income Inequality” (Indicator) . Paris: OECD Publishing. Also available at https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm . Search in Google Scholar

Ostry, J. D., P. Loungani, and D. Furceri. 2016. “ Neoliberalism: Oversold? ” Finance and Development 532: 38–41. Also available at https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2016/06/ostry.htm . Search in Google Scholar

Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century . Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 10.4159/9780674369542 Search in Google Scholar

Piketty, T. 2020. Capital and Ideology . Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 10.4159/9780674245075 Search in Google Scholar

Revenga, A. 1992. “Exporting Jobs? The Impact of Import Competition on Employment and Wages in U.S. Manufacturing.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (1): 255–84, https://doi.org/10.2307/2118329 . Search in Google Scholar

Rosenfeld, J., and B. Western. 2011. “Unions, Norms, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality.” American Sociological Review 78 (4): 513–37. 10.1177/0003122411414817 Search in Google Scholar

Rowlingson, K. 2011. Does Income Inequality Cause Health and Social Problems? York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Search in Google Scholar

Saez, E., and M. Veall. 2005. “The Evolution of High Incomes in Northern America: Lessons from Canadian Evidence.” American Economic Review 95 (3): 831–49, https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828054201404 . Search in Google Scholar

Scheidel, W. 2017. The Great Leveller: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century . Princeton: Princeton University Press. 10.1515/9781400884605 Search in Google Scholar

Schrecker, T., and C. Bambra. 2015. How Politics Makes Us Sick: Neoliberal Epidemics . New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 10.1057/9781137463074 Search in Google Scholar

Shaxson, N. 2015. Ten Reasons to Defend the Corporation Tax . London: Tax Justice Network. Also available at http://www.taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Ten_Reasons_Full_Report.pdf . Search in Google Scholar

Solt, F. 2020. “Measuring Income Inequality across Countries and over Time: The Standardized World Income Inequality Database.” Social Science Quarterly 101 (3): 1183–99. Version 9.0, https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12795 . Search in Google Scholar

Stiglitz, J. 2013. The Price of Inequality . London: Penguin Books. 10.1111/npqu.11358 Search in Google Scholar

The Equality Trust . 2018. “The Spirit Level Data.” London. Also available at https://www.equalitytrust.org.uk/civicrm/contribute/transact?reset=1&id=5 . Search in Google Scholar

Thomas, A. 2016. Republic of Equals: Predistribution and Property-Owning Democracy . Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190602116.001.0001 Search in Google Scholar

Tridico, P. 2018. “The Determinants of Income Inequality in OECD Countries.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 42 (4): 1009–42, https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bex069 . Search in Google Scholar

Visser, J. 2019. ICTWSS Database . Version 6.1. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies (AIAS), University of Amsterdam. Search in Google Scholar

Whitworth, A. 2012. “Inequality and Crime across England: A Multilevel Modelling Approach.” Social Policy and Society 11 (1): 27–40, https://doi.org/10.1017/s1474746411000388 . Search in Google Scholar

Wilkinson, R. 1996. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality . London: Routledge. Search in Google Scholar

Wilkinson, R., and K. Pickett. 2009. The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone . London: Penguin Books. Search in Google Scholar

Wilkinson, R., and K. Pickett. 2019. The Inner Level: How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress, Restore Sanity and Improve Everyone’s Well-Being . London: Penguin Books. Search in Google Scholar

Wiwad, D., B. Mercier, P. K. Piff, A. Shariff, and L. B. Aknin. 2021. “Recognizing the Impact of COVID-19 on the Poor Alters Attitudes towards Poverty and Inequality.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2020.104083 . Search in Google Scholar

World Economic Forum. 2020. The Global Social Mobility Report 2020 . Geneva: World Economic Forum. Also available at https://www3.weforum.org/docs/Global_Social_Mobility_Report.pdf . Search in Google Scholar

Zucman, G. 2015. The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens . Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 10.7208/chicago/9780226245560.001.0001 Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

- X / Twitter

Supplementary Materials

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

Journal and Issue

Articles in the same issue.

Advertisement

The impact of education costs on income inequality

- Research Article

- Open access

- Published: 03 April 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Fa-Hsiang Chang 1

469 Accesses

Explore all metrics

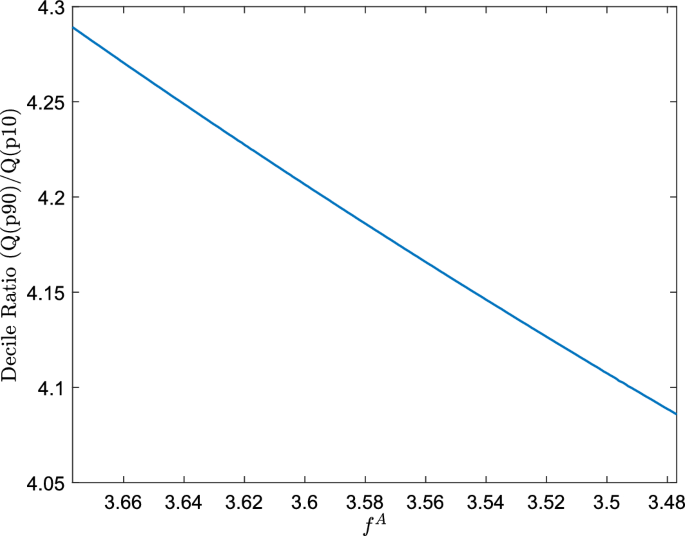

Reducing education costs is a crucial policy element with broad support in the U.S. However, is lowering the cost of learning a panacea for eliminating income inequality? In this paper, I theoretically examine the relationship between income inequality and the cost of education by building a three-stage overlapping generation model with two sectors and two education systems. In contrast to conventional studies treating education as a unified concept or in hierarchical order, I consider two types of education, each targeting the training of workers for different roles in production. Workers who decide to spend time learning and improving creativity skills can work to produce intermediate goods used in current production and illuminate future production technology. Coders who produce industrial robots are one example of workers who receive this type of education. The other type of education only improves workers’ efficiency and helps them become experts in positions. For instance, office clerks who receive computer training can become more productive in dealing with their daily tasks. I pick a reasonable set of parameters, and the simulation result implies that reducing the cost of practical training may end up enlarging income inequality. The key is whether the effect resulting from the wage gap between jobs ( wage effect ) dominates the effect of changing the share of workers in jobs ( composition effect ). Reducing the cost of learning creativity encourages marginal experts to learn creativity and marginal basic workers to receive training, leading to declining wage gaps and income inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Employment Market Effects of Basic Income

Optimal linear income taxes and education subsidies under skill-biased technical change

Make IT Work: The Labor Market Effects of Information Technology Retraining in the Netherlands

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Is lowering the cost of learning a panacea for eliminating income inequality? The answers are highly debatable in economics and vary across countries and time. Back to Schultz ( 1963 ), investing in education is seen as a means to reduce income inequality by enhancing human capital. There are a bunch of empirical findings that support this positive relationship. See Gregorio and Lee ( 2002 ), Sylwester ( 2002 ) and Coady and Dizioli ( 2018 ) for a broad range of countries; Abdullah et al. ( 2015 ) for Africa, for example. However, it is essential to note that the relationship between education and income inequality is complex. According to Knight and Sabot ( 1983 ), education expansion increases the proportion of educated workers ( composition effect ). However, it may lead to a decline in wage premiums ( wage effect ), resulting in an ambiguous effect on inequality. Moreover, in some cases, education may primarily serve as a signal rather than directly reducing inequality (Spence 1973 ). Some empirical findings support that education may have little or even a detrimental effect on income inequality (see Battistón et al. 2014 for most countries in Latin America; Rodríguez-Pose and Tselios 2009 for regions in the European Union; etc.). Ram ( 1989 ) reviews previous theoretical and empirical papers and reaches the same conclusion.

However, the current studies either treat education as a homogeneous concept or categorize it in a hierarchical manner (e.g., Rodríguez-Pose and Tselios 2009 ; Abdullah et al. 2015 ) without considering its categorization based on the labor market objectives. Different jobs require specific and distinct skill sets in today’s technologically advanced world with rapidly evolving knowledge. Some jobs demand creative problem-solving abilities, while others focus on repetitive tasks. As a result, different types of education and training are required and established. This paper theoretically examines the relationship between the cost of training and income inequality, considering the two types of training based on the type of workers they nurture.

Following Becker and Tomes ( 1979 )’s string of thoughts, the income inequality in the economy is composed of inter-generational and within-cohort income differences. In this paper, I establish a three-period overlapping generation model to discuss the inter-generational income differences. In this paper, I do not focus on on-the-job training. I assume that individuals make education decisions when young, work during middle age, and retire in old age. To account for the within-cohort differences, I assume individuals are heterogeneous in endowed learning ability and choose education and occupation endogenously.

Before delving into the detailed model setup, it is worthwhile to elucidate the concept of training and the associated costs in this paper. In this context, the cost of receiving training incurs not only financial expenses but also consumes considerable time and effort, especially in an economy characterized by rapid knowledge iteration. With the higher skill requirements in the labor market, the costs of training increase when the teaching effectiveness remains constant. The reason is that acquiring the necessary knowledge and qualifications can become more challenging and time-consuming.

In this paper, I classify two types of training based on workers’ roles in production. The economy features two representative firms producing two types of final goods, requiring workers in three distinct types of occupations. Footnote 1 The first type of occupation demands workers capable of performing simple, repetitive tasks without extensive training or professional knowledge, referred to as basic workers. For instance, a janitor falls into this category. The other types of occupations require a certain level of extensive experience or training for more efficient work than basic workers. An example is the first-line supervisor, who is considered an expert due to the extensive knowledge required for the role. Candidates often undergo training and promotion from within similar fields. The type of education that increases workers’ production efficiencies is called practical training in this paper. A janitor, for example, can choose to receive practical training to learn structural cleaning techniques and be promoted to a first-line supervisor role, directly overseeing and coordinating the work activities of cleaning personnel. Basic workers and experts serve as inputs in the production of one type of final goods referred to as “non-automatable” goods in my model, such as service goods. The last group of occupations requires workers with solid professional foundations to explore cutting-edge technology or knowledge. Those are workers who receive the second type of education to enhance their creativity so they can produce intermediate goods used in current production and illuminate future production technology. For instance, coders who produce industrial robots are one example of workers who receive this type of education. Hence, the second type of final goods is called “automatable” goods because production requires intermediate goods (e.g., robots) produced by creative workers (e.g., coders) and physical capital (e.g., machines). Unlike “non-automatable” goods, “automatable” goods do not require labor in production directly. For example, cars can be considered “automatable” goods due to the widespread use of robots and machines in their production.

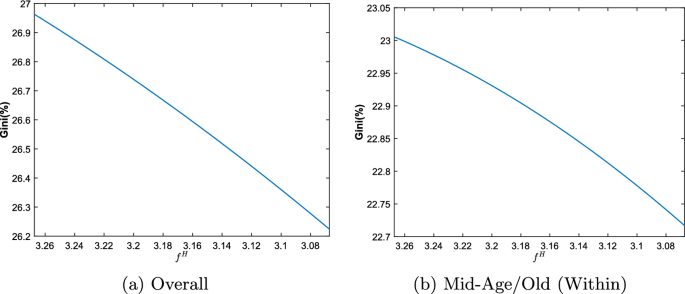

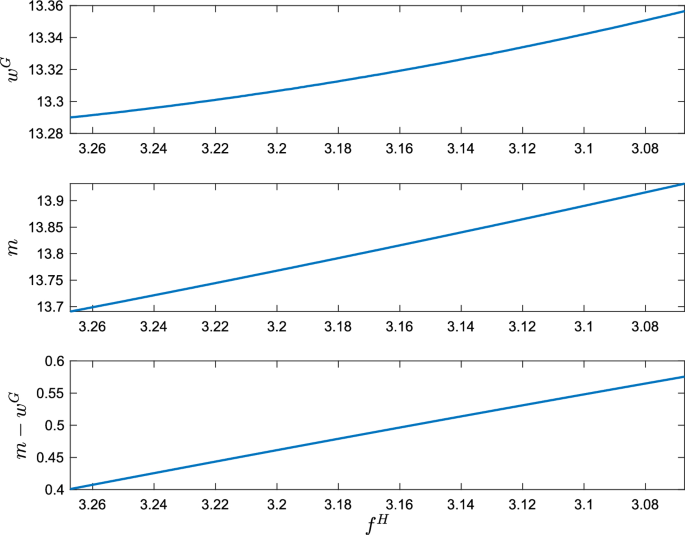

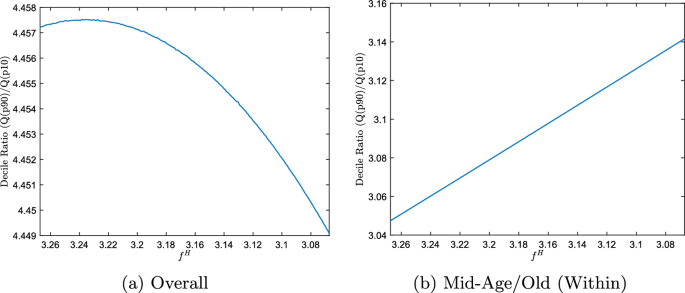

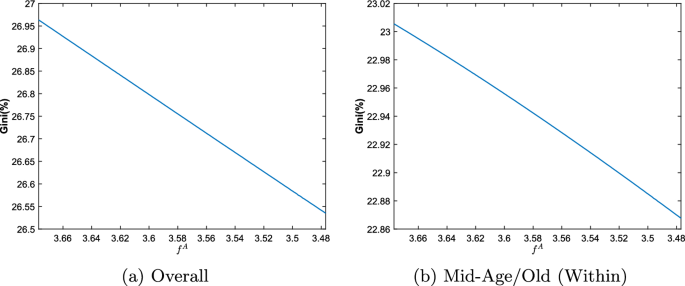

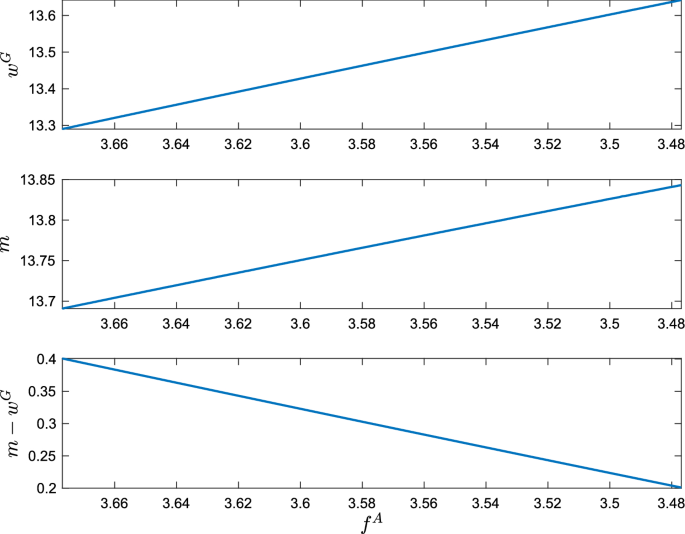

In the U.S., reducing education costs is a key element of policy with broad support. However, my paper argues that the impact of policy on income inequality depends on the targeted type of education. The paper calibrates the U.S. data and simulates the consequences of reducing two types of education costs on income inequality. The results demonstrate that reducing the cost of learning creativity reduces income inequality while reducing the cost of practical training may end up enlarging income inequality. I focus on within-group income inequality, as the simulated income differences between middle-aged and older workers with similar learning abilities do not change remarkably with reduced education costs. The reduction in the cost of learning creativity attracts more experts to become creative workers and also attracts basic workers to receive practical training. Moreover, the wage gap between basic and creative workers shrinks, leading to a decline in within-cohort and overall income inequality. However, reducing practical training costs makes becoming experts an attractive option to both marginal basic workers and marginal creative workers. So, assuming prices do not change when the training costs decline, the share of experts increases, and both the numbers of basic and creative workers shrink. However, the widening wage gap between creative workers and basic workers attracts workers to become creative workers. Thus, only the share of basic workers declines, and the numbers of experts and creative workers rise. Therefore, the effect of the declining cost of practical training on income inequality depends on the predominance of the composition effect and wage effect.

This study presents a novel explanation of the relationship between education and income inequality without asserting the superiority or universality of different educations. Existing literature examines the complex relationship from two perspectives. One perspective focuses on the different returns on education. According to Mincer ( 1974 ), encouraging individuals to pursue higher education may exacerbate income inequality, as the returns to higher education remain relatively higher than that on compulsory education. Other studies highlight the influence of learning ability and parental investment on educational choices. For instance, Yang and Qiu ( 2016 ) analyzes the impact of innate ability, compulsory education (grades 1–9), and non-compulsory education (grades 10–12 and higher education) on income inequality in China, emphasizing the significance of family investment in early education as a determinant of income inequality. Similarly, Prettner and Schaefer ( 2021 ) emphasizes the importance of inheritance flows on education choices and income inequality. This paper does not explicitly model a joint family utility function but assumes resource transfer from middle-aged to young individuals. The second perspective focuses on the signaling theory. For example, Hendel et al. ( 2005 ) explores the signaling role of education combined with households’ credit constraints, suggesting that affordable borrowing or lower tuition can encourage high-ability individuals to leave the unskilled pool, thereby increasing the skill premium. However, these studies generally consider education in a hierarchical order and do not discuss the types of training that lead to different job choices at the same stage of life. This paper fills this gap in the existing literature. It addresses the importance of skill selection in light of labor market polarization, as highlighted by studies such as Autor and Dorn ( 2013 ), Deming ( 2017 ), and Deming and Kahn ( 2018 ). For instance, Autor and Dorn ( 2013 ) emphasizes the reallocation of low-skill workers to service occupations due to the reduced cost of automating routine and codifiable job tasks, leading to earnings growth at the extremes of the income distribution. By incorporating different types of education based on the skills they develop, this paper contributes to understanding the relationship between education and income inequality.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the model setup and some preliminary theoretical results. Section 3 introduces calibration strategies and presents simulation results. Section 4 provides the concluding remarks.

2 The model

I develop a three-stage overlapping generation model featuring endogenous education and occupation choices in the economy with two final goods. All markets are perfectly competitive, and there are no uncertainties. The model incorporates three key features. Firstly, the economy includes two representative firms producing different goods, and each requires different types of workers in the production technology. Secondly, I introduce two education types that are aligned with the skills they impart. Individuals can opt for (1) no education, (2) practical training, or (3) training in creativity skills. Individuals with perfect foresight choose the types of education they pursue during their youth. Different educational backgrounds lead to distinct roles in production, resulting in different labor incomes when they are middle-aged - the only working period in my model. Thirdly, individuals are heterogeneous in my model. Individuals differ in their endowed learning ability \(z \sim F(\cdot )\) . This endowed learning ability does not play a role if individuals choose not to receive education. Thus, the model allows me to discuss the behaviors of workers who receive different types of education across cohorts and how the change in the cost of each type of education impacts them. The model details are introduced in the following sections.

2.1 Firms and technologies

In this economy, two representative firms produce two types of final goods. The first type, referred to as “automatable” goods (e.g., cars), involves tasks in production that do not require manual labor. The firm producing “automatable” goods depends on physical capital and intermediate goods produced by creative workers as inputs. For instance, coders write programs to develop software, and machines are operated on assembly lines to produce the goods. The production of “automatable” goods ( \(Y_t\) ) at time t follows the Cobb-Douglas production function:

where \(D_Y\) represents total factor productivity in “automatable” goods production, \(K_t\) denotes the physical capital stock at time t , and \(A_t\) denotes the stock of intermediate goods produced by creative workers at time t . Here, \(\alpha\) is the output elasticity of capital, with \(0< \alpha < 1\) . In each period t , the production of intermediate goods ( \(A_t\) ) by creative workers follows a linear fashion:

where \(e^A e^{z^i}\) represents the productivity of a creative worker i after receiving training in creativity. \(\bar{z}_{t-1}\) denotes the threshold value of endowed learning ability that divides experts and creative workers for those born at time \(t-1\) and work in period t . This threshold value changes over time in the short run but remains a fixed number in the steady state.

The second type of goods is “non-automatable” goods, such as service goods, where production is dependent only on labor directly. “Non-automatable” goods are produced by workers who do not receive training in creativity skills. I assume the “non-automatable” goods production function is linear, where basic workers and experts are perfect substitutes, and the only difference between basic workers and experts is their productivity. For instance, certified massage therapists can undergo practical training, obtain a license, and transform into licensed massage therapists. Their treatments improve as they acquire knowledge in areas such as anatomy and physiology, ultimately passing the bodywork licensing exam administered by states. In the production function of “non-automatable” goods, I exclude physical capital, as it typically plays a minor role in production. For example, a massage therapist relies more on massage skills than machines to treat customers. Thus, I assume the production function of the “non-automatable” goods is

where \(D_S\) denotes the total factor productivity in the production of “non-automatable” goods, and \(G_t\) is the number of basic workers without training. The endowed learning ability thresholds, \(\underline{z}_{t-1}\) and \(\bar{z}_{t-1}\) , represent the minimum and maximum values for individuals working at time t . Detailed explanations and closed-form expressions for these thresholds are provided in Sect. 2.2.1 .

2.1.1 Firm’s problem

“Automatable” Goods . I assume the “automatable” good is the numeraire. Given all the prices, the representative firm that produces “automatable” goods solves the following maximization problem to determine the capital demand and intermediate goods demand,

where \(m_t\) is the price of the intermediate goods, and \(r_t\) is the rental rate of physical capital. The demands for capital and intermediate goods can be expressed in the following first-order conditions,

“Non-automatable” Goods . Given all prices, the representative firm producing the “non-automatable” good maximizes profit by determining the demand for basic workers and experts:

where \(q_t\) represents the price of the “non-automatable” goods, and \(w_t^G\) is the wage of a basic worker. Given the linear production function, the existence of equilibrium requires the cost of hiring one basic worker and one expert to be equal, clearing the two labor markets,

2.2 Individuals

The economy is populated by overlapping generations of agents, each living for three periods. Within each generation, a continuum of individuals with different learning abilities is born. In this paper, I assume the endowed learning ability of individual i is drawn from a uniform distribution \(z^i \sim U(0,1)\) for simplicity. For each period, the economy includes individuals with the same endowed learning ability but born in different generations. In other words, in period t , the economy includes individuals with the same \(z^i\) but born in generations \(t-2, t-1, t\) . For simplicity, I use subscripts y , m , and o to denote whether the individual is young, middle-aged, or old, respectively, and use t to indicate the current time of the economy.

Individuals in this model value the consumption of two goods throughout their lifetime with a logarithmic utility function. For each individual i born in generation t , the utility is defined as:

where \(0<\kappa <1\) , and c , s denote the consumption of “automatable” goods and “non-automatable” goods separately. \(c^i_{y,t}, s^i_{y,t}\) show the consumption of “automatable” goods and “non-automatable” goods for individual i born in generation t during their young age at time t . Similarly, \(c^i_{m,t+1}, s^i_{m,t+1}\) represent the consumption of “automatable” goods and “non-automatable” goods for the same individual during their middle age at time \(t+1\) . Finally, \(c^i_{o,t+2}, s^i_{o,t+2}\) signify the consumption of “automatable” goods and “non-automatable” goods for individual i during their old age at time \(t+2\) .

Individuals own the factors of production in this economy. They supply physical capital and labor to the firms through factor markets. The physical capital market allows individuals to transfer resources to the next period. Since I assume individuals are heterogeneous, they can engage in borrowing and lending through the trading of one-period capital. In the paper, I assume “automatable” goods can be consumed or invested in each period, but “non-automatable” goods can only be consumed. The conversion rate between “automatable” goods and physical capital is one.

In this model, Individuals endogenously make educational choices when they are young. I assume the young have no initial endowment on the physical capital, so they have to borrow from the capital market in that period to fulfill the needs of consumption and education. Let \(f^i_t\) denote the fixed cost of learning, \(b^i_{y,t+1}\) as the amount of acquired physical capital stock for the agent i in period t when young. The subscript \(t+1\) signifies that the return will be repaid in period \(t+1\) . Here, \(b^i_{y,t+1}<0\) because the young are borrowing capital. Then, the budget constraint for the individual i born in generation t when young is

Agents are assumed to work full-time and can only work when they are in middle age. Based on their educational choices when young, individuals work in different occupations when they are in middle age. Those who receive no education when young become basic workers in middle age to produce the“non-automatable” goods with productivity normalized to one. For the individual i who receives practical training when young becomes an expert in middle age to produce the “non-automatable” goods with productivity \(e^H e^{z^i}\) , and individual i receives training in creativity skill when young becomes a creative worker to produce the intermediate goods in “automatable” goods production with productivity \(e^A e^{z^i}\) . Let \(I^i_{t+1}\) denotes the labor income for individual i born in generation t in the middle age, where

Furthermore, in the economy at time \(t+1\) , middle-aged workers are required to repay \(r_{t+1}\) units of interest for each unit of capital borrowed at youth. An individual i born in generation t also engages in the investment of physical capital since it serves as their sole source of income in old age. The physical capital depreciates at the rate of \(\delta\) ( \(0<\delta <1\) ). Let \(b^i_{m,t+2}\) represent the physical capital stock that will yield the capital return for the individual when they reach old age. Therefore, this middle-aged individual will invest \(b^i_{m,t+2}-(1-\delta )b^i_{y,t+1}\) units of physical capital. Thus, the budget constraint for the middle-aged individual i born in generation t is

When the individual i who was born at generation t becomes old, the only source of income comes from the physical stock of capital. The budget constraint for this individual when old is

2.2.1 Individual’s problem

For each individual i born in generation t , the agent solves the following maximization problem:

The intertemporal budget constraint for this individual can be summarized as follows:

where \(\tilde{r} = r-\delta\) . From the intertemporal budget constraint, the lifetime disposable income matters for allocations across the life cycle. The lifetime disposable income is the subtraction of the present value of income and educational costs. Since \(f^A > f^H\) , the wage of creative workers should be greater than the wage of experts, which requires \(e^A m_{t+1}> e^H w_{t+1}^G\) , to ensure the existence of equilibrium. Let me denote \(z_{1,t} = \frac{(1+\tilde{r}_{t+1})(f^A-f^H)}{e^Am_{t+1}-e^H w^G_t}\) , \(z_{2,t} = \frac{w^G_t + (1+\tilde{r}_{t+1})f^A}{e^Am_{t+1}}\) , \(z_{3,t} = \frac{w^G_t +(1+\tilde{r}_{t+1})f^H}{e^H w^G_t}\) .

Proposition 1

(Occupational & Educational Choices) If \(z_{1,t}>z_{2,t}\) , agents with \(z^i \in \left( \ln (z_{1,t}), 1 \right]\) invests in creativity and become creative workers; agents with \(z^i \in \left[ \ln (z_{3,t}), \ln (z_{1,t})\right]\) are experts with training; and agents with \(z^i\in \left[ 0, \ln (z_{3,t}) \right)\) receive no education and become basic workers. If \(z_{1,t} \le z_{2,t}\) , agents with \(z^i \in \left( \ln (z_{2,t}), 1 \right]\) receive training in creativity and become creative worker; and agents with \(z^i \in \left[ 0, \ln (z_{2,t}) \right]\) receive no education and become basic workers.

See Appendix A.1. \(\square\)

Thus, if \(z_{1,t}>z_{2,t}\) , \(\bar{z}_t = \ln (z_{1,t})\) and \(\underline{z}_t = \ln (z_{3,t})\) (case 1). Otherwise, \(\bar{z}_t =\underline{z}_t = \ln (z_{2,t})\) (case 2). This proposition posts constraints in parameter values, which I use in the calibration section. For the individual i born in generation t , the demands of two types of goods in each period satisfy,

The supply of capital for the individual when young is

The supply of capital for the middle-aged individual is

2.3 Markets clear conditions

This economy has two labor markets, two goods markets, and one capital market. I denote \(G_{t}\) as the demand of basic workers, \(H_{t}\) as the demand of experts by the firm produces “non-automatable” goods at time t , and \(E_{t}\) as the demand of creative workers by the firm produces “automatable” goods at time t . \(C_{y,t}, C_{m,t}, C_{o,t}, S_{y,t}, S_{m,t}, S_{o,t}\) as total consumption of “automatable” goods and “non-automatable” by the young, middle-aged and old individuals at time t respectively. I denote \(B_{m,t}, B_{y,t}\) as the supply of the aggregate capital from young and middle-aged workers in period t , respectively. The market equilibrium conditions can be shown as follows.

Labor Markets.

Goods Markets.

Capital Market.

2.4 Equilibrium

A sequential markets equilibrium consists of allocations \(\{ c^{i}_{m,1},s^{i}_{m,1}, c^{i}_{o,1}, s^{i}_{o,1}, c^{i}_{o,2}, s^{i}_{o,2}\) , \(b^{i}_{y,1}, b^{i}_{m,1}, b^{i}_{m,2},\{c^{i}_{y,t},s^{i}_{y,t}, c^{i}_{m,t+1},s^{i}_{m,t+1}, c^{i}_{o,t+2}, s^{i}_{o,t+2}, f^{i}_t, b^{i}_{y,t+1}, b^{i}_{m,t+2}\}_{i}\) , \(K_t, A_t, Y_t, S_t, G_t, H_t, E_t\} _{t=1}^{\infty}\) and prices \(\left\{ w^G_t,m_t,q_t,r_t\right\} _{t=1}^\infty\) , such that:

Given \(\{w^G_t,m_t,q_t,r_t\}_{t=1}^\infty\) , each generation determines optimal consumption bundles and capital investments across the life cycle, educational and occupational choices as mentioned in Sect. 2.2.1 .

Given \(\{w^G_t,m_t,q_t,r_t\}_{t=1}^\infty\) , two representative firms determine labor demand and capital demand, as mentioned in Sect. 2.1.1 .

Goods markets, labor markets, and capital markets are clear in each period as mentioned in Sect. 2.3 .

In this paper, I focus on the analysis of the steady-state equilibrium. The steady-state equilibrium conditions are summarized in Appendix A.2.

3 Simulation

3.1 calibration strategy.

To conduct numerical analyses, I begin by selecting a model parameterization as detailed below. The model’s steady-state equilibrium is calibrated to the U.S. average statistics from 2002 to 2020. In this model, workers live for three periods, equating each to 25 years to align with real-life data.

There are three types of occupations in the model, and I characterize detailed occupations in Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) into three categories manually based on their job requirements. Basic workers perform simple, repetitive tasks without extensive training, including roles like hand makers, attendants, and helpers. Experts, requiring practical training, manage and adapt to job responsibilities through extensive experience or professional knowledge, often bringing some levels of innovation to their roles; this category includes occupations such as managers, administrators, and superintendents. Creative workers engage in roles that demand a solid professional base and creativity to explore frontier technologies and knowledge, such as directors, artists, and scientists. The appendix A.4 details these categories and lists specific job titles within each.

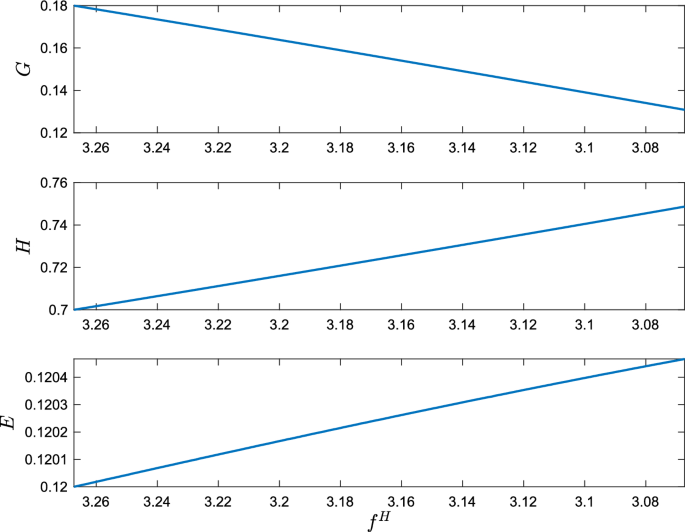

I obtain employment and mean hourly wage data for each occupation from the U.S. Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) program. By calculating the average employment share and hourly wage for each occupational category, it is found that 18% of workers are basic workers, 70% are experts, and 12% are creative workers ( \(G = 0.18, H = 0.70\) , \(E = 0.12\) ), with basic workers earning an average hourly wage of $13.29 ( \(w^G = 13.29\) ). Additionally, I compute the wage premium of experts over basic workers and the wage premium of creative workers over experts, finding the latter exceeds one, indicating \(e^A m> e^H w^G\ \text {and}\ f^A> f^H\) . These wage premiums, however, are not used for calibration but to check the model’s fit.

Additionally, I derive total labor income from the wages and salaries reported in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Footnote 2 In the model, I assume the middle-aged population supplies the total time endowment for work, and the overall population in each generation is normalized to 1 in the economy. Consequently, the income in the model is interpreted as per-hour income. Thus, I divide the total wages and salaries by the total hours worked each year. The total hours worked data is obtained from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). I find the total labor income is $35.34 ( \(TotLI = 35.34)\) . Utilizing occupational employment shares, I then calculate the learning ability threshold values, \(\underline{z} = G = 0.18\) , and \(\bar{z} = 1-E = 0.88\) .

I categorize parameters into two groups: fixed and free. Fixed parameters are derived directly from data or are widely accepted in the literature. Free parameters are determined iteratively by substituting data values into theoretical moments. Table 1 lists all parameters in the model and calibrated values.

Fixed Parameter. I set the discount factor to \(\beta = 0.99^{25} = 0.778\) , following precedents in literature such as Hurd ( 1990 ) and Ludwig and Vogel ( 2010 ). Considering the annual capital depreciation rate of 0.05, as cited by Kulish et al. ( 2010 ) and equating one period in the model to 25 years, I adjust the depreciation rate to \(\delta = 1-(1-0.05)^{25} = 0.723\) . Furthermore, I normalize the total factor productivity for “non-automatable” goods D S to one.

Free Parameter. Due to the indistinguishability of individuals’ outcomes from the costs of two types of education ( \(f^A\) and \(f^H\) ) and the productivity enhancer difference between them ( \(e^H\) and \(e^A\) ), I equate \(e^H\) to \(e^A\) . Using the obtained data and equilibrium conditions, I can calibrate values of all parameters as listed in Table 1 . I first assume \(e^H\) is known, and the calibration process unfolds through three nested loops to determine the capital income ( rK ), the total education spending ( \(TotEdu= f^HH+f^AE\) ), and the net interest rate ( \(\tilde{r}\) ). The methodology and rationale for solving these three variables are discussed in the subsequent paragraphs.

To calibrate \(\alpha\) , which signifies the capital income share in total “automatable” goods production, I compute \(\alpha = \frac{rK}{Y} = \frac{rK}{rK+mA}\) , with \(mA = TotLI-qS\) . Here, TotLI represents the total labor income, and qS shows the income from “non-automatable” goods, equating to the labor income of both basic workers and experts. For a given level of \(e^H\) , I can compute \(qS = w^GG+e^Hw^G(e^{\bar{z}}- e^{\underline{z}})\) by using available data. Therefore, by determining rK , the calibrated value of \(\alpha\) can be obtained.

Then, to calibrate the set \(\{\kappa , f^H, f^A, D_Y\}\) , the focus narrows to solving for total education spending ( \(TotEdu= f^HH+f^AE\) ), and net interest rate ( \(\tilde{r}\) ). \(\kappa\) represents the proportion of consumption expenditure on “non-automatable” goods relative to total consumption, calculated as \(\kappa = \frac{qS}{qS+TotC}\) . Determining \(\kappa\) requires the total consumption on “automatable” goods TotC . For a given level of \(\{e^H, rK, \tilde{r}, TotEdu\}\) , I obtain \(K = \frac{rK}{r} = \frac{rK}{\tilde{r}+\delta }\) . From the “automatable” goods resource constraint, the total number of consumption on the “automatable” goods is \(TotC = Y - \delta K - TotEdu\) , with \(Y = mA + rK\) reflecting the competitive market condition.

Thus, I get the calibrated value of \(\kappa = \frac{qS}{qS+TotC}\) . Moreover, I compute the cost of practical training \(f^H = \frac{(e^H e^{\underline{z}}-1)w^G}{1+\tilde{r}}\) from the basic worker labor market clear condition (Eqn. (A6)), and the cost of receiving training in creativity skill \(f^A = \frac{TotEdu - f^H H}{E}\) from the definition of total spending on education in the economy. Lastly, the total factor productivity in “automatable” goods production, \(D_Y\) , is determined as \(D_Y = \frac{Y}{K^\alpha A^{1-\alpha }}\) , where \(A = e^H(e-e^{\bar{z}})\) .

The following process illustrates how I solve these three key variables through a structured three-layer loop process for a given level of \(e^H\) :

Outer Loop: This step focuses on determining capital income ( rK ) by satisfying the capital market equilibrium condition (Eqn. (A10));

Middle Loop: The objective here is to find the total education spending ( TotEdu ) using the labor market clear condition for creative workers (Eqn. (A8));

Inner Loop: This loop involves calculating the net interest rate ( \(\tilde{r}\) ) to satisfy the “automatable” goods market clear condition (Eqn. (A9)).

I calibrate the value of \(e^H = 1.620\) to ensure the existence of an equilibrium where \(e^Am > e^Hw^G\) , \(f^A > f^H\) , and the capital income share \(\alpha\) are all consistent with the data. Footnote 3