Trending Today

Spending Too Much Time on Homework Linked to Lower Test Scores

A new study suggests the benefits to homework peak at an hour a day. After that, test scores decline.

Samantha Larson

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/58/e3587081-d161-4c6e-b4f9-a94b3520c60d/homework.jpg)

Polls show that American public high school teachers assign their students an average of 3.5 hours of homework a day . According to a recent study from the University of Oviedo in Spain, that’s far too much.

While doing some homework does indeed lead to higher test performance, the researchers found the benefits to hitting the books peak at about an hour a day. In surveying the homework habits of 7,725 adolescents, this study suggests that for students who average more than 100 minutes a day on homework, test scores start to decline. The relationship between spending time on homework and scoring well on a test is not linear, but curved.

This study builds upon previous research that suggests spending too much time on homework leads to higher stress, health problems and even social alienation. Which, paradoxically, means the most studious of students are in fact engaging in behavior that is counterproductive to doing well in school.

Because the adolescents surveyed in the new study were only tested once, the researchers point out that their results only indicate the correlation between test scores and homework, not necessarily causation. Co-author Javier Suarez-Alvarez thinks the most important findings have less to do with the amount of homework than with how that homework is done.

From Education Week :

Students who did homework more frequently – i.e., every day – tended to do better on the test than those who did it less frequently, the researchers found. And even more important was how much help students received on their homework – those who did it on their own preformed better than those who had parental involvement. (The study controlled for factors such as gender and socioeconomic status.)

“Once individual effort and autonomous working is considered, the time spent [on homework] becomes irrelevant,” Suarez-Alvarez says. After they get their daily hour of homework in, maybe students should just throw the rest of it to the dog.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Samantha Larson | | READ MORE

Samantha Larson is a freelance writer who particularly likes to cover science, the environment, and adventure. For more of her work, visit SamanthaLarson.com

Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement?

- Share this story on facebook

- Share this story on twitter

- Share this story on reddit

- Share this story on linkedin

- Get this story's permalink

- Print this story

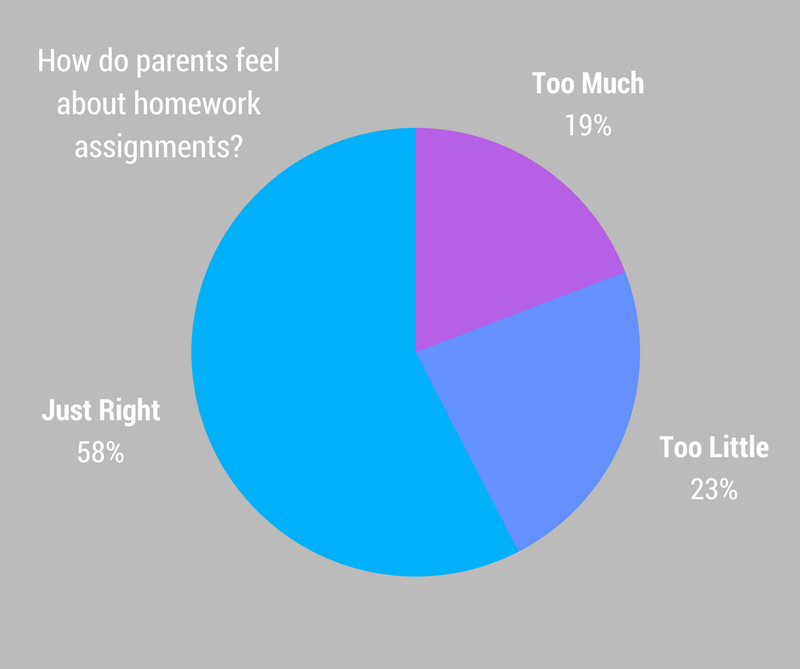

Educators should be thrilled by these numbers. Pleasing a majority of parents regarding homework and having equal numbers of dissenters shouting "too much!" and "too little!" is about as good as they can hope for.

But opinions cannot tell us whether homework works; only research can, which is why my colleagues and I have conducted a combined analysis of dozens of homework studies to examine whether homework is beneficial and what amount of homework is appropriate for our children.

The homework question is best answered by comparing students who are assigned homework with students assigned no homework but who are similar in other ways. The results of such studies suggest that homework can improve students' scores on the class tests that come at the end of a topic. Students assigned homework in 2nd grade did better on math, 3rd and 4th graders did better on English skills and vocabulary, 5th graders on social studies, 9th through 12th graders on American history, and 12th graders on Shakespeare.

Less authoritative are 12 studies that link the amount of homework to achievement, but control for lots of other factors that might influence this connection. These types of studies, often based on national samples of students, also find a positive link between time on homework and achievement.

Yet other studies simply correlate homework and achievement with no attempt to control for student differences. In 35 such studies, about 77 percent find the link between homework and achievement is positive. Most interesting, though, is these results suggest little or no relationship between homework and achievement for elementary school students.

Why might that be? Younger children have less developed study habits and are less able to tune out distractions at home. Studies also suggest that young students who are struggling in school take more time to complete homework assignments simply because these assignments are more difficult for them.

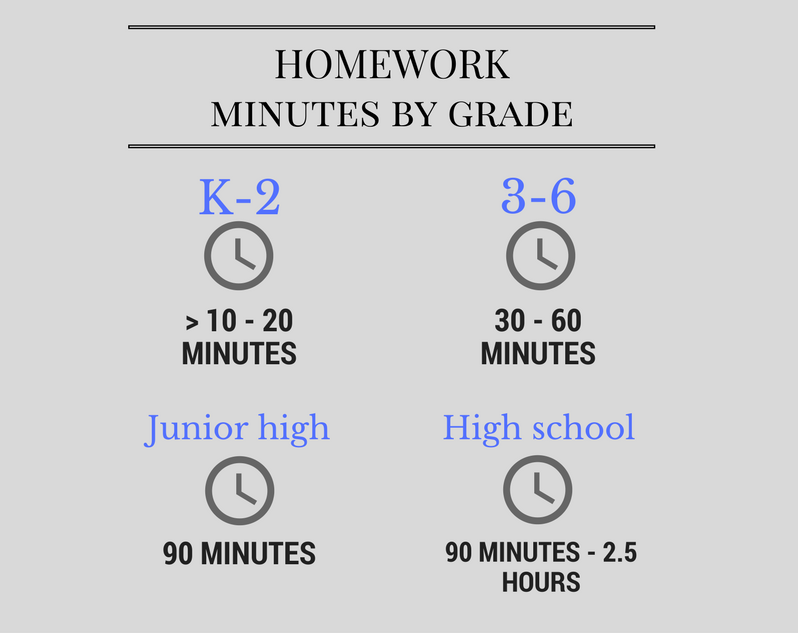

These recommendations are consistent with the conclusions reached by our analysis. Practice assignments do improve scores on class tests at all grade levels. A little amount of homework may help elementary school students build study habits. Homework for junior high students appears to reach the point of diminishing returns after about 90 minutes a night. For high school students, the positive line continues to climb until between 90 minutes and 2½ hours of homework a night, after which returns diminish.

Beyond achievement, proponents of homework argue that it can have many other beneficial effects. They claim it can help students develop good study habits so they are ready to grow as their cognitive capacities mature. It can help students recognize that learning can occur at home as well as at school. Homework can foster independent learning and responsible character traits. And it can give parents an opportunity to see what's going on at school and let them express positive attitudes toward achievement.

Opponents of homework counter that it can also have negative effects. They argue it can lead to boredom with schoolwork, since all activities remain interesting only for so long. Homework can deny students access to leisure activities that also teach important life skills. Parents can get too involved in homework -- pressuring their child and confusing him by using different instructional techniques than the teacher.

My feeling is that homework policies should prescribe amounts of homework consistent with the research evidence, but which also give individual schools and teachers some flexibility to take into account the unique needs and circumstances of their students and families. In general, teachers should avoid either extreme.

Link to this page

Copy and paste the URL below to share this page.

Too Much Homework Can Lower Test Scores, Researchers Say

By: Natalie Wolchover Published: 03/30/2012 09:42 AM EDT on Lifes Little Mysteries

Piling on the homework doesn't help kids do better in school. In fact, it can lower their test scores.

That's the conclusion of a group of Australian researchers, who have taken the aggregate results of several recent studies investigating the relationship between time spent on homework and students' academic performance.

According to Richard Walker, an educational psychologist at Sydney University, data shows that in countries where more time is spent on homework, students score lower on a standardized test called the Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA. The same correlation is also seen when comparing homework time and test performance at schools within countries. Past studies have also demonstrated this basic trend.

Inundating children with hours of homework each night is detrimental, the research suggests, while an hour or two per week usually doesn't impact test scores one way or the other. However, homework only bolsters students' academic performance during their last three years of grade school. "There is little benefit for most students until senior high school (grades 10-12)," Walker told Life's Little Mysteries .

The research is detailed in his new book, "Reforming Homework: Practices, Learning and Policies" (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

The same basic finding holds true across the globe, including in the U.S., according to Gerald LeTendre of Pennsylvania State University. He and his colleagues have found that teachers typically give take-home assignments that are unhelpful busy work. Assigning homework "appeared to be a remedial strategy (a consequence of not covering topics in class, exercises for students struggling, a way to supplement poor quality educational settings), and not an advancement strategy (work designed to accelerate, improve or get students to excel)," LeTendre wrote in an email. [ Kids Believe Literally Everything They Read Online, Even Tree Octopuses ]

This type of remedial homework tends to produce marginally lower test scores compared with children who are not given the work. Even the helpful, advancing kind of assignments ought to be limited; Harris Cooper, a professor of education at Duke University, has recommended that students be given no more than 10 to 15 minutes of homework per night in second grade, with an increase of no more than 10 to 15 minutes in each successive year.

Most homework's neutral or negative impact on students' academic performance implies there are better ways for them to spend their after school hours than completing worksheets. So, what should they be doing? According to LeTendre, learning to play a musical instrument or participating in clubs and sports all seem beneficial , but there's no one answer that applies to everyone.

"These after-school activities have much more diffuse goals than single subject test scores," he wrote. "When I talk to parents … they want their kids to be well-rounded, creative, happy individuals — not just kids who ace the tests."

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover . Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries , then join us on Facebook .

- Easy Answers to the Top 5 Science Questions Kids Ask

- Smart Answers for Crazy Hypothetical Questions

- Pointing Your Finger Makes You Credible to Kids

Copyright 2012 Lifes Little Mysteries, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

It's another trump-biden showdown — and we need your help, the future of democracy is at stake, your loyalty means the world to us.

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

The 2024 election is heating up, and women's rights, health care, voting rights, and the very future of democracy are all at stake. Donald Trump will face Joe Biden in the most consequential vote of our time. And HuffPost will be there, covering every twist and turn. America's future hangs in the balance. Would you consider contributing to support our journalism and keep it free for all during this critical season?

HuffPost believes news should be accessible to everyone, regardless of their ability to pay for it. We rely on readers like you to help fund our work. Any contribution you can make — even as little as $2 — goes directly toward supporting the impactful journalism that we will continue to produce this year. Thank you for being part of our story.

It's official: Donald Trump will face Joe Biden this fall in the presidential election. As we face the most consequential presidential election of our time, HuffPost is committed to bringing you up-to-date, accurate news about the 2024 race. While other outlets have retreated behind paywalls, you can trust our news will stay free.

But we can't do it without your help. Reader funding is one of the key ways we support our newsroom. Would you consider making a donation to help fund our news during this critical time? Your contributions are vital to supporting a free press.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our journalism free and accessible to all.

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. Would you consider becoming a regular HuffPost contributor?

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. If circumstances have changed since you last contributed, we hope you'll consider contributing to HuffPost once more.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

Before You Go

Popular in the community, from our partner, more in science.

More From Forbes

Why homework doesn't seem to boost learning--and how it could.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Some schools are eliminating homework, citing research showing it doesn’t do much to boost achievement. But maybe teachers just need to assign a different kind of homework.

In 2016, a second-grade teacher in Texas delighted her students—and at least some of their parents—by announcing she would no longer assign homework. “Research has been unable to prove that homework improves student performance,” she explained.

The following year, the superintendent of a Florida school district serving 42,000 students eliminated homework for all elementary students and replaced it with twenty minutes of nightly reading, saying she was basing her decision on “solid research about what works best in improving academic achievement in students.”

Many other elementary schools seem to have quietly adopted similar policies. Critics have objected that even if homework doesn’t increase grades or test scores, it has other benefits, like fostering good study habits and providing parents with a window into what kids are doing in school.

Those arguments have merit, but why doesn’t homework boost academic achievement? The research cited by educators just doesn’t seem to make sense. If a child wants to learn to play the violin, it’s obvious she needs to practice at home between lessons (at least, it’s obvious to an adult). And psychologists have identified a range of strategies that help students learn, many of which seem ideally suited for homework assignments.

For example, there’s something called “ retrieval practice ,” which means trying to recall information you’ve already learned. The optimal time to engage in retrieval practice is not immediately after you’ve acquired information but after you’ve forgotten it a bit—like, perhaps, after school. A homework assignment could require students to answer questions about what was covered in class that day without consulting their notes. Research has found that retrieval practice and similar learning strategies are far more powerful than simply rereading or reviewing material.

One possible explanation for the general lack of a boost from homework is that few teachers know about this research. And most have gotten little training in how and why to assign homework. These are things that schools of education and teacher-prep programs typically don’t teach . So it’s quite possible that much of the homework teachers assign just isn’t particularly effective for many students.

Even if teachers do manage to assign effective homework, it may not show up on the measures of achievement used by researchers—for example, standardized reading test scores. Those tests are designed to measure general reading comprehension skills, not to assess how much students have learned in specific classes. Good homework assignments might have helped a student learn a lot about, say, Ancient Egypt. But if the reading passages on a test cover topics like life in the Arctic or the habits of the dormouse, that student’s test score may well not reflect what she’s learned.

The research relied on by those who oppose homework has actually found it has a modest positive effect at the middle and high school levels—just not in elementary school. But for the most part, the studies haven’t looked at whether it matters what kind of homework is assigned or whether there are different effects for different demographic student groups. Focusing on those distinctions could be illuminating.

A study that looked specifically at math homework , for example, found it boosted achievement more in elementary school than in middle school—just the opposite of the findings on homework in general. And while one study found that parental help with homework generally doesn’t boost students’ achievement—and can even have a negative effect— another concluded that economically disadvantaged students whose parents help with homework improve their performance significantly.

That seems to run counter to another frequent objection to homework, which is that it privileges kids who are already advantaged. Well-educated parents are better able to provide help, the argument goes, and it’s easier for affluent parents to provide a quiet space for kids to work in—along with a computer and internet access . While those things may be true, not assigning homework—or assigning ineffective homework—can end up privileging advantaged students even more.

Students from less educated families are most in need of the boost that effective homework can provide, because they’re less likely to acquire academic knowledge and vocabulary at home. And homework can provide a way for lower-income parents—who often don’t have time to volunteer in class or participate in parents’ organizations—to forge connections to their children’s schools. Rather than giving up on homework because of social inequities, schools could help parents support homework in ways that don’t depend on their own knowledge—for example, by recruiting others to help, as some low-income demographic groups have been able to do . Schools could also provide quiet study areas at the end of the day, and teachers could assign homework that doesn’t rely on technology.

Another argument against homework is that it causes students to feel overburdened and stressed. While that may be true at schools serving affluent populations, students at low-performing ones often don’t get much homework at all—even in high school. One study found that lower-income ninth-graders “consistently described receiving minimal homework—perhaps one or two worksheets or textbook pages, the occasional project, and 30 minutes of reading per night.” And if they didn’t complete assignments, there were few consequences. I discovered this myself when trying to tutor students in writing at a high-poverty high school. After I expressed surprise that none of the kids I was working with had completed a brief writing assignment, a teacher told me, “Oh yeah—I should have told you. Our students don’t really do homework.”

If and when disadvantaged students get to college, their relative lack of study skills and good homework habits can present a serious handicap. After noticing that black and Hispanic students were failing her course in disproportionate numbers, a professor at the University of North Carolina decided to make some changes , including giving homework assignments that required students to quiz themselves without consulting their notes. Performance improved across the board, but especially for students of color and the disadvantaged. The gap between black and white students was cut in half, and the gaps between Hispanic and white students—along with that between first-generation college students and others—closed completely.

There’s no reason this kind of support should wait until students get to college. To be most effective—both in terms of instilling good study habits and building students’ knowledge—homework assignments that boost learning should start in elementary school.

Some argue that young children just need time to chill after a long day at school. But the “ten-minute rule”—recommended by homework researchers—would have first graders doing ten minutes of homework, second graders twenty minutes, and so on. That leaves plenty of time for chilling, and even brief assignments could have a significant impact if they were well-designed.

But a fundamental problem with homework at the elementary level has to do with the curriculum, which—partly because of standardized testing— has narrowed to reading and math. Social studies and science have been marginalized or eliminated, especially in schools where test scores are low. Students spend hours every week practicing supposed reading comprehension skills like “making inferences” or identifying “author’s purpose”—the kinds of skills that the tests try to measure—with little or no attention paid to content.

But as research has established, the most important component in reading comprehension is knowledge of the topic you’re reading about. Classroom time—or homework time—spent on illusory comprehension “skills” would be far better spent building knowledge of the very subjects schools have eliminated. Even if teachers try to take advantage of retrieval practice—say, by asking students to recall what they’ve learned that day about “making comparisons” or “sequence of events”—it won’t have much impact.

If we want to harness the potential power of homework—particularly for disadvantaged students—we’ll need to educate teachers about what kind of assignments actually work. But first, we’ll need to start teaching kids something substantive about the world, beginning as early as possible.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Stanford research shows pitfalls of homework

A Stanford researcher found that students in high-achieving communities who spend too much time on homework experience more stress, physical health problems, a lack of balance and even alienation from society. More than two hours of homework a night may be counterproductive, according to the study.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

• Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

• Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

• Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

clock This article was published more than 11 years ago

Study: Homework linked to better standardized test scores

Researchers who looked at data from more than 18,000 10th-graders found there was little correlation between the time students spent doing homework and better grades in math and science courses. But, according to a study on the researc h, they did find a positive relationship between standardized test performance and the amount of time spent on homework.

The study , called ”When Is Homework Worth the Time?: Evaluating the Association Between Homework and Achievement in High School Science and Math,” was conducted by Adam Maltese, assistant professor of science education at the Indiana University School of Education; Robert H. Tai, associate professor of science education at the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia, and Xitao Fan, dean of education at the University of Macau.

According to a news release by Indiana University, the researchers looked at survey and transcript data from the students in an effort to explain their academic performance and concluded that despite earlier research to the contrary, homework time did not correlate to the final course grade that students received in math and science classes.

The value of homework has been the subject of various research studies over the years, yet there is still no conclusive evidence that it makes a big difference in helping students improve achievement. The most often-cited studies are those that conclude that there is virtually no evidence that it helps in elementary school but some evidence that it does improve academic performance in later grades. Yet this newest study looked at 10th graders and found no correlation.

The study did, however, find a positive association between time spent on homework and student scores on standardized tests. It doesn’t directly conclude that the homework actually affected the test scores, but the university release quotes Maltese as saying that “if students are spending more time on homework, they’re getting exposed to the types of questions and the procedures for answering questions that are not so different from standardized tests.”

That, of course, would depend on the kind of homework students receive. Maltese is further quoted as saying, “”We’re not trying to say that all homework is bad. It’s expected that students are going to do homework. This is more of an argument that it should be quality over quantity. So in math, rather than doing the same types of problems over and over again, maybe it should involve having students analyze new types of problems or data. In science, maybe the students should write concept summaries instead of just reading a chapter and answering the questions at the end.”

The co-authors also recommend that education policymakers better evaluate homework — the kinds of assignments that are most useful and the time required to make the work effective.

You may also be interested in this : 3 Healthy Guidelines for Homework

Study: Homework Doesn’t Mean Better Grades, But Maybe Better Standardized Test Scores

Robert H. Tai, associate professor of science education at UVA's Curry School of Education

The time students spend on math and science homework doesn’t necessarily mean better grades, but it could lead to better performance on standardized tests, a new study finds.

“When Is Homework Worth The Time?” was recently published by lead investigator Adam Maltese, assistant professor of science education at Indiana University, and co-authors Robert H. Tai, associate professor of science education at the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education , and Xitao Fan, dean of education at the University of Macau. Maltese is a Curry alumnus, and Fan is a former Curry faculty member.

The authors examined survey and transcript data of more than 18,000 10th-grade students to uncover explanations for academic performance. The data focused on individual classes, examining student outcomes through the transcripts from two nationwide samples collected in 1990 and 2002 by the National Center for Education Statistics.

Contrary to much published research, a regression analysis of time spent on homework and the final class grade found no substantive difference in grades between students who complete homework and those who do not. But the analysis found a positive association between student performance on standardized tests and the time they spent on homework.

“Our results hint that maybe homework is not being used as well as it could be,” Maltese said.

Tai said that homework assignments cannot replace good teaching.

“I believe that this finding is the end result of a chain of unfortunate educational decisions, beginning with the content coverage requirements that push too much information into too little time to learn it in the classroom,” Tai said. “The overflow typically results in more homework assignments. However, students spending more time on something that is not easy to understand or needs to be explained by a teacher does not help these students learn and, in fact, may confuse them.

“The results from this study imply that homework should be purposeful,” he added, “and that the purpose must be understood by both the teacher and the students.”

The authors suggest that factors such as class participation and attendance may mitigate the association of homework to stronger grade performance. They also indicate the types of homework assignments typically given may work better toward standardized test preparation than for retaining knowledge of class material.

Maltese said the genesis for the study was a concern about whether a traditional and ubiquitous educational practice, such as homework, is associated with students achieving at a higher level in math and science. Many media reports about education compare U.S. students unfavorably to high-achieving math and science students from across the world. The 2007 documentary film “Two Million Minutes” compared two Indiana students to students in India and China, taking particular note of how much more time the Indian and Chinese students spent on studying or completing homework.

“We’re not trying to say that all homework is bad,” Maltese said. “It’s expected that students are going to do homework. This is more of an argument that it should be quality over quantity. So in math, rather than doing the same types of problems over and over again, maybe it should involve having students analyze new types of problems or data. In science, maybe the students should write concept summaries instead of just reading a chapter and answering the questions at the end.”

This issue is particularly relevant given that the time spent on homework reported by most students translates into the equivalent of 100 to 180 50-minute class periods of extra learning time each year.

The authors conclude that given current policy initiatives to improve science, technology, engineering and math, or STEM, education, more evaluation is needed about how to use homework time more effectively. They suggest more research be done on the form and function of homework assignments.

“In today’s current educational environment, with all the activities taking up children’s time both in school and out of school, the purpose of each homework assignment must be clear and targeted,” Tai said. “With homework, more is not better.”

Media Contact

Rebecca P. Arrington

Office of University Communications

[email protected] (434) 924-7189

Article Information

November 20, 2012

/content/study-homework-doesn-t-mean-better-grades-maybe-better-standardized-test-scores

What Test Scores Actually Tell Us

- Posted November 6, 2019

- By Jill Anderson

Professor Andrew Ho thinks test scores often simplify how we view student performance, school effectiveness, and really educational opportunity. By taking a more comprehensive look at data like test scores and learning rates in districts, we may be able to better identify and contextualize how well a school is really performing. In this episode of the Harvard EdCast, Ho discusses his work with the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford University and how it provides data to help scholars, policymakers, educators, and parents learn to improve educational opportunity for all children.

Jill Anderson: I'm Jill Anderson. This is the Harvard EdCast. We love and perhaps even loathe test scores, but it's how so many of us choose where to send our kids to school. Then how good a job a school might be doing and how we compare schools. Harvard professor Andrew Ho wants us to think more about what test scores actually tell us. He studies how we design educational test scores, use them, and whether there's better ways to judge academic performance and educational opportunity. He's involved in the recently launched Educational Opportunity Project based at Stanford, where people can go to get a more comprehensive look at their school district. I wanted to know more about that project and what educational opportunity really means.

At edopportunity.org we're measuring test scores and test scores are not the complete measure of what we want for our kids. Nonetheless, if you look at all of these state tests, what do they measure? Mathematics proficiency and reading and those are quantitative reasoning, as well as a kid's ability to read are really important. You need to read to be able to learn. And so they are important measure as well we also recognize they're not the sum total of everything we hope schools to do and hope for our kids. So that's what we mean Ed Opportunity as we operationalize it on the website as test scores, but they are strongly correlated with a number of other measures that we do care about, right? So while recognizing that they're incomplete, we also believe they're important.

Jill Anderson: What our test scores actually tell us about a school and the students there?

Andrew Ho: I got into this field because I recognized as a teacher in high school and also in middle school and as an observer of schools and particularly in Japan where I spent my junior year abroad, just how powerful test scores were as a lever for policy and curricular change. Everyone was saying, "We have to teach this because it's on the test." And that I realized was both very, very sad and an incredible opportunity to improve test scores and to improve the design of tests, not just to make them more relevant, but to make the results more actionable. And that's how I sort of got into this, this whole enterprise was a belief that we weren't designing tests right and using test scores right and that we could do a better job.

So I, and many other psychometricians, measurement folks, have really mixed feelings about tests. We want to improve them, we believe that they're powerful, but we believe they're also just sort of too powerful sometimes and people simplify what educational quality and opportunity is to a single number that is useful but imperfect. And so it's with that sort of humility but also recognizing this incredible promise that I went into this project thinking, "All right, how can we take the 350 million test scores that we've accumulated over the past 9, 10 years or so, and put them to good use to enable people to understand how complicated and variable educational opportunity as measured by test scores, is in this country?"

And so what I would recommend is for any given subject or grade, every State in this country makes test score items, the questions we ask of kids available. And I think we can be skeptical and should be skeptical of tests, but if you look at most of these questions, you sort of say to yourself, "Actually, I kind of want my kid to be able to answer this correctly. I kind of would like them to be able to understand vocabulary words, use them in context and be able to reason with numbers and algebra and geometry." These are abilities and skills and dispositions that we really do want our kids to have. Are they perfect? Are they everything? Do they encompass social, emotional aspects? No, they are incomplete, but they are still desirable. And so it's with that sort of humility, but also recognizing the importance of being able to communicate, being able to reason that we believe that these are incomplete but important measures.

Jill Anderson: Do you think the public understands the complexities of this? There's a lot of websites in the world that compare test score results from one community, one school, to another, and that's all you're getting. You might get some other ratios, demographics, that kind of thing, but it's fairly limited information.

Andrew Ho: Right. This is the problem we're trying to solve. The learning goals of this project are to appreciate just how different are test scores from changes in test scores because isn't that what education is about? Not just a score, but how we improve that score, right? Not just my daughter's ability to read, but how she gets better at reading and what I can do to improve that reading. And so that's the story of learning. And for us to be able to distinguish between those two, between test scores and learning changes in test scores, right? Or another way to put it is between proficiency and growth is a key learning goal of the website. And so, no, I don't think we as a society and even among folks in education communities, we are able to distinguish enough between what is good in terms of a level and what is good in terms of progress. So I hope that we can keep both in mind. It's not to say that performance doesn't matter and learning is all that matters, right? We should say that both matter. We can want high levels and we also want progress.

Jill Anderson: One of the things that is introduced through that Educational Opportunity Project is the learning rate. What is a learning rate?

Andrew Ho: When we say like, "There are good schools there," let's unpack that a bit. There are at least two answers there, 50 that we should consider, but at least two criteria that we want to really drill down in this project. And the first is to get people on the hook with what they already think they know, right? Which is about average test scores. And usually when you say, "There are good schools there," you think to yourself about average test scores. And of course the first thing you see when you click into that chart, we call it the Galaxy Chart because it looks kind of like the Milky Way at night, right? So that scatterplot there that shows that striking strong correlation between socioeconomic status and test scores, right? That's what we want to complexify, they are average test scores.

But now wait, look. Look at that tab over there and all of a sudden you see learning rates. Now what are learning rates? There's a difference between saying kids are above average in third grade, above average in eighth grade and coming in below average in third grade and ending eighth grade above average. So how would we describe those two schools where you come in in third grade above average, leave in eighth grade above average versus a school where you start below average but end above average? How would you describe those? They're both having kids that leave in eighth grade well above average, but wouldn't you say, "Wow, there's really something going on with that school that's bringing in kids at third grade who are below average and they're leaving at eighth grade above average."

So that's what learning is, and I think it's striking to realize that if we were to just to take an average, we would rank that school that's doing such a good job of bringing kids at the third grade who are below average, all the way up to above average, we'd rank that school below the other, right? One school is, you might say it's like polishing bright apples. It's like you get all these kids with high socioeconomic status and you bring them in and you keep them there. Congratulations. And here's another school that's taking students who have not had much early childhood opportunity, or early great opportunity and they're launching them to really high levels.

Shouldn't we recognize that as opposed to penalizing that school for having low third grade test scores? Shouldn't we care that there's a ton of learning happening at one school and not at another? And we have to recognize at a snapshot that if you just look at the districts that are polishing bright apples, should we be giving them credit for that? Or should we also recognize a second criterion, which is how much learning is going on in these schools?

Jill Anderson: I can imagine people hearing this and Googling this and they're pulling up their community and they're seeing negative 12% learning rates, for the district, for the whole community and hitting the panic button.

Andrew Ho: What negative means here is below average, right? It does not mean that kids know less this year. In what ways would we want them to be concerned, right? You know that your school has high or low test scores on average, does that mean anything about what you can say about their learning rates? And the answer is you don't know anything. All this knowledge that we have in our heads about what good schools and not so good schools are based on these averages, which don't really tell you about learning. In a way I hope it forces people to reconsider their notion of what a good school is and then ask, "Wait a second, how can we do better? How can we make sure that our kids who are coming in above average and might be leaving more close to average, what can we do about that?" And the answer is that there's a whole bunch of schools and districts out there that have really high learning rates, perhaps we should learn from them.

And so I hope that the panic isn't from this notion that a school that has below average learning will always be such, and the work of anyone who deals with numbers to take an improvement mindset to them. To say that these are not fixed features of schools, these are not fixed features of districts. These are things we can change and all of us at the graduate school of education, whoever all about, it's like, "Learn to change the world," we say. So yeah, let's think about what we can do better. And so I hope the panic is not the paralyzing panic, it's the productive panic, right? It's like, "Okay, let's get to work," and figure out why there's so much variation in achievement and in progress and learning across these schools and districts and learn from the best of them so that that negative 12% becomes positive 12% in the future.

Jill Anderson: So we do want to look at learning rates more?

Andrew Ho: Well, for what purpose? Again, one of the stories in our discoveries is that gaps correlate strongly with segregation. And so one of the things we deeply do not want to do is encourage parents to use this to select the quote best schools on any metric, right? As opposed to saying, "This helps me to discover what every school in every district can do better." Because again, these numbers are malleable, right? We can do something about them. So yes, I think the level one goal is to complexify the notions of school quality, right? And to say that there are actually multiple criteria we might want to consider when we're thinking about how to figure out if a school is doing well.

But then, once we figure out if a school is doing well, the solution isn't to send all the kids to just those schools. That is our sort of darkest fear out of all of this. We do not want to simply resort everybody into high quality schools, however defined, we want to say there are lessons to learn in all of these schools that we could apply broadly so that everyone, to use the Lake Wobegon metaphor, everyone should be above average, right? So everyone should be continuously improving. And if you look under the hood of the data, what we've done is we've managed, again, we described it as like a patchwork quilt where each State and every year is its own little patch. And what we've done is through our methods and statistical and psychometric methods, we've managed to stitch all these different patches together into sort of a big picture.

I think it's only when you have that context, the silos create this kind of... You have these blinders on and you're only looking at Massachusets and you're only looking at 2019. You don't see change and progress and you don't get to contextualize it in a nine year history of spanning grades three through eight. And so what I'm really proud of is that we've managed to the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, right? It's like we can see through the stitching the dramatic variability in test scores and in learning rates, and that I think is what we hope along the lines what we've seen is like, "Yeah, we've always known about proficiency and growth, but it's never been presented in a way where you can see all the constellations, all the pieces of the puzzle," and that's what we hope this project does.

Jill Anderson: Andrew Ho is a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. I'm Jill Anderson. This is the Harvard EdCast produced by the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Thanks for listening.

An education podcast that keeps the focus simple: what makes a difference for learners, educators, parents, and communities

Related Articles

Where Have All the Students Gone?

Student Testing, Accountability, and COVID

Testing, Crime, and Punishment

Student GPA and test score gaps are growing—and could be slowing pandemic recovery

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, tom swiderski and tom swiderski postdoctoral research associate, epic - university of north carolina at chapel hill sarah crittenden fuller sarah crittenden fuller research associate professor - unc-chapel hill and epic @sarahcfuller1.

November 6, 2023

- Administrative data from North Carolina shows that while students’ state exam scores have declined since pre-pandemic, their course grades are similar to pre-pandemic levels.

- This growing gap between student GPAs and achievement could be contributing to parents’ confusion about the extent of their children’s needs for pandemic recovery supports and an under-utilization of recovery programs.

- Strong communication between schools and communities will be key to ensuring the success of recovery efforts at the scale needed to reverse pandemic learning losses.

The harm to student learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has been well documented , and an incredible influx of resources—including $260 billion in federal government investment—has been dedicated to support schools’ recovery. Much of this money has been spent developing and expanding academic recovery efforts such as after-school tutoring and summer learning programs. Yet participation in recovery programs has been disappointingly low , often reaching no more than 20% to 30% of targeted students.

Although some students may not participate in recovery programs due to barriers related to program accessibility , experts suggest there may also be an “ urgency gap ” among parents, who may be underestimating the extent to which their children are behind. Surveys of parents have found that while the vast majority recognize that the pandemic harmed students’ math and reading achievement in general, most also report far more positive outlooks for their own children’s academic progress.

Understanding the urgency gap is vital. While tutoring and other recovery programs can be effective at improving student achievement, students cannot benefit if they do not participate, potentially slowing the pace of academic recovery.

In this piece, we describe one possible reason for the urgency gap – that while students’ test scores have fallen dramatically, their GPAs have not. And because parents often rely on report card grades to interpret how their children are doing in school, this growing gap between student GPAs and achievement may be contributing to parents’ confusion about the extent of their children’s needs for recovery supports.

Comparing post-pandemic grades and test scores

We begin by showing how students’ grades and test scores have changed since the onset of the pandemic using student-level data from North Carolina. 1 Figure 1 compares the percentage of students who earned an A or B in their math class and the percentage who met proficiency benchmarks on their end-of-grade state math exam in 2018-19 and 2021-22. In 2018-19, the percentage of students who earned an A or B in math was the same as the proficiency rate (54%). However, by 2021-22, there was a sizable gap between these metrics, as proficiency rates decreased much more than grades. As of 2021-22, the proficiency rate had fallen by 11 percentage points (to 43%) while the percentage of students earning As or Bs had fallen by just 3 points (to 51%).

Figure 2 examines this data another way, depicting the average test scores of students in 2018-19 and 2021-22 disaggregated by the letter grade they received in math. At every letter grade, post-pandemic students averaged lower scores on state exams than pre-pandemic peers who received the same grade in math. The average test score of students who earned an A in math in 2021-22 was 0.20 standard deviations lower than the scores of pre-pandemic peers who earned an A. For students who earned a B, the gap was 0.25 standard deviations, and similar results can be observed for all other letter grades. This highlights that even students with high course grades are scoring much lower on state exams than pre-pandemic peers who earned similar grades.

Understanding the difference between grades and test scores

Differences between standardized test scores and grades are not unexpected, as these are different measures that provide different insights into students’ performance in school. Standardized test scores offer a consistent criterion of students’ performance over time that is comparable across large populations and cohorts—a feature that makes them very useful for understanding pandemic impacts and recovery. At the same time, test scores provide only a snapshot of a student’s knowledge at a single point in time, which can be influenced by factors such as students’ wellness on the day of a test, general feelings of test anxiety, and ability to guess multiple choice questions. As a result, many students and parents may feel that test scores do not fully represent their or their child’s skills, knowledge, and efforts.

On the other hand, course grades reflect a mix of students’ mastery of content covered by their instructor, as measured by exams and quizzes, as well as positive participation and effort, such as speaking up in class, completing homework, and generally behaving well. Course grades are a more holistic measure of student performance, and research shows this can make them a better predictor of postsecondary success than test scores. However, this means that grades and test scores can diverge over time for many reasons, due to either students’ or teachers’ actions. For example, students might increase effort, or teachers might slow instructional pacing to cover less content, introduce more lenient grading policies, or grade on a curve. Course grades are therefore less useful for understanding COVID-19 recovery because it is not clear how these practices—including grading standards—may have changed over time.

“Grade inflation” is a term often used to describe the phenomenon where GPAs rise faster than test scores over time, which was occurring pre-pandemic . This provides a useful frame of reference for understanding the post-pandemic trends we observe in North Carolina and which have also been observed nationally . However, the post-pandemic version has also taken a very different form than pre-pandemic. Post-pandemic grade inflation has resulted from GPAs not decreasing despite drops in test scores rather than GPAs rising despite stagnant test scores. The post-pandemic gap between grades and test scores opened up in a much more pronounced and sudden way than was occurring pre-pandemic. And post-pandemic grades are holding steady despite the fact that not only has achievement worsened, but so have other indicators of student engagement, such as attendance and reported behavior problems .

Importantly, the post-pandemic version of grade inflation may also be due to very different—and potentially more transient—underlying motivations than pre-pandemic. Some degree of grade inflation could be reasonable in the current moment for many reasons. It may be appropriate to provide some additional leniency towards students given the events of recent years, perhaps even more so given the poor state of youth mental health . Dramatically increasing course failure rates could create a crisis of its own by decreasing student morale and engagement, potentially leading to higher dropout rates, whereas rewarding students’ efforts to get back on track could be beneficial for increasing engagement. Further, because of the impacts of the pandemic, teachers may be spending more time reviewing old content, leading them to be unable to cover all grade-level standards. If so, it may be unfair to grade students poorly if they are learning the material that is covered in class but display gaps in knowledge on state tests that are more comprehensive.

At the same time, this trend is not without consequences. Most importantly, one likely consequence that we see is that parents, who often rely on their children’s grades to interpret their performance in school, are severely underestimating how far behind their children are. This, in turn, may be contributing to an under-utilization of recovery programs and, ultimately, a slow and stalling recovery.

Moving forward

To ensure that parents are fully informed about the impacts of the pandemic on their children, states, districts, and schools should aim to make sure that parents receive clear, consistent, and regular feedback about how their children are performing on work they are completing this year as well as how they are performing compared to historic norms and benchmarks. This may mean working to make sure that parents see how test scores and grades provide different, valuable insights into student performance, know how to interpret test scores, and ultimately recognize that their children may need recovery services even if they are receiving As and Bs (indeed, students themselves should understand this as well).

Meanwhile, state and federal government investment into recovery services should not end without a stronger understanding of why programs are being underutilized, particularly given that students will likely need years of additional support to return to pre-pandemic achievement levels. If barriers to program take-up can be addressed, services could reach more students and have a greater impact on recovery. State and federal investment should support schools and districts to conduct more outreach to better understand the needs, concerns, and beliefs about the impacts of the pandemic within their communities.

Recovering from the pandemic remains a monumental challenge requiring substantial investment from students, parents, educators, and policymakers alike. Failing to achieve a strong recovery may hinder not only students’ educational prospects, but also life course outcomes related to employment, health, and well-being. Strong communication between schools and communities will be key to ensuring the success of recovery efforts at the scale needed to reverse pandemic losses.

Related Content

Douglas N. Harris

August 29, 2023

Umut Özek, Louis T. Mariano

March 27, 2023

Megan Kuhfeld, Karyn Lewis

January 30, 2023

- Specifically, we use individual-level course transcript and test score records from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. We focus on grade 6 math, grade 7 math, grade 8 math, and Math 1 because these exams remained equivalently scaled between 2018-19 and 2021-22 (reading exams were rescaled between 2018-19 and 2021-22). To compare standardized scores across cohorts, we standardized the 2018-19 cohort’s scale scores (within exam) and then anchored post-pandemic cohorts’ scale scores to this distribution; in other words, we assigned post-pandemic students to have the standardized score that their scale score received in the 2018-19 cohort. We converted course grades to a 0-4 GPA scale following North Carolina state guidelines (e.g., an ‘A’ or a numeric grade of 90 percent or greater was coded as 4.0). North Carolina has made no statewide changes to grading standards outside of emergency measures in place for Spring 2020 only.

Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

U.S. States and Territories

Brown Center on Education Policy

Katharine Meyer

May 7, 2024

Jamie Klinenberg, Jon Valant, Nicolas Zerbino

Thinley Choden

May 3, 2024

Low Test Scores Have Educators Worried, Survey Shows

- Share article

A majority of educators say their schools’ or districts’ standardized test results from last spring are lower than they were pre-pandemic—and that they find the numbers concerning.

Those are the findings from a recent nationally representative EdWeek Research Center survey of teachers, principals, and district administrators. The survey was administered in late October and early November, with 977 respondents.

Of survey-takers who had received their schools’ spring state test results, 70 percent said that scores were down across the board from where they were before COVID, or were down in some areas and held steady in others.

In math, 80 percent of respondents said elementary scores were concerning and 81 percent said the same of secondary scores. Numbers were similar in English/language arts, with 76 percent of educators concerned by elementary scores and 74 percent for secondary scores.

About a quarter of respondents said they hadn’t received state test results from last spring (the survey sample also included teachers who taught in untested subjects).

These results add to the growing stream of data demonstrating that students’ academic progress stalled over the 2020-21 school year, amid the pandemic’s interruptions to instruction. Just earlier this month, for example, curriculum and assessment provider Curriculum Associates released results from its reading and math diagnostic tests this fall , showing that fewer students in grades 1 through 8 are on grade level in reading and math than in years past.

But state standardized test results, specifically, come with several caveats, assessment experts have said. As Education Week’s Catherine Gewertz reported last month , disruptions to testing-as-usual during the 2020-21 school year could affect the validity of the scores.

Some states allowed students to test remotely, making it difficult to compare their results to those of students who tested in person. And many states reported lower-than-average participation rates, meaning that the results might not reflect the student population.

Even in districts where most students tested in person, some educators say that the results have limited usefulness this year.

In the past, Andrew McDaniel might have compared results at his school to others in the state, to see if he could learn from similar schools that had better scores in certain areas. But this year there are too many variables at play—how much time kids spent in buildings, or how much support they had from families at home—to glean much useful information from that kind of comparison, said McDaniel, the principal of Southwood Junior/Senior High School in Wabash, Ind.

“It’s important, but it’s not the only data point that we look at,” he said of state test scores.

Scores aren’t ‘fine-grained enough to guide instruction’

State standardized test scores only capture one moment in time, a point that critics of using them for accountability purposes have long emphasized. But this fact makes scores especially hard to interpret during the pandemic, as students’ learning environments keep shifting, McDaniel said.

For example, at Southwood Junior/Senior High School, some students were remote during the 2020-21 school year while others attended school in person. Many of those who were in person still had to leave the building for weeks at a time due to quarantining requirements. Lots of students struggled with online learning, McDaniel said.

“Our numbers for failing grades were just off the charts.” And that was reflected in the school’s state test scores, which were lower than in years’ past.

This year, though, the district isn’t offering a remote option, so all students are in the building. The district has also changed the quarantining policy, so that parents can choose to keep sending children to school if they’ve been exposed to someone who tested positive, as long as the student isn’t showing symptoms. (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that all unvaccinated students who have been exposed should quarantine, though some schools have started to remove these requirements or put other policies in place during the 2021-22 school year.)

Students are spending a lot more time in the building this year than they did last year, and they’re already making academic progress, McDaniel said. The 2020-21 test scores, while low, aren’t his biggest concern in this new landscape. Instead, it’s behavior and social-emotional skills, as students re-learn the routines of school.

Other educators say that their students’ scores from last year reflect persisting academic needs.

Mike Huler, the secondary mathematics curriculum specialist in Westerville City Schools in Ohio, said that scores were “considerably worse in the last testing cycle” than in years’ past. He attributes the dips to a few factors. Instructional mode in the district shifted throughout the year, between hybrid and in-person learning, causing disruptions. And the spring shutdowns in 2020 pushed teachers to play catch-up with the previous year’s content at the start of the 2020-21 school year, rather than moving on to grade-level work.

“It’s very difficult to convince teachers to stay on grade-level standards and scaffold in when needed, as opposed to, ‘We didn’t cover that at the end of last year and we need to do that first,’” he said. “So there was much more backfilling than I would have liked before we even knew what [students] needed.”

Still, he doesn’t think that state assessment from last spring can provide much of a roadmap for how to support students now. “The information that we get from the state isn’t really fine-grained enough to guide instruction,” Huler said.

Instead, he’s supporting teachers in using a combination of quantitative and qualitative data at the classroom and school levels.

Math teachers are using a supplemental online learning program to diagnose and fill gaps in grade-level skills. The district has also started doing “learning rounds,” sending groups of teachers and school- and district-level administrators out to schools to observe what practices teachers are using.

These groups are looking for the kinds of practices that will set students up for success in high school, like math conversation, persistence through complex problems, and working on tasks that require reasoning and could have more than one solution.

“I’m more concerned with preparing kids for the long run,” Huler said.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

The Cult of Homework

America’s devotion to the practice stems in part from the fact that it’s what today’s parents and teachers grew up with themselves.

America has long had a fickle relationship with homework. A century or so ago, progressive reformers argued that it made kids unduly stressed , which later led in some cases to district-level bans on it for all grades under seventh. This anti-homework sentiment faded, though, amid mid-century fears that the U.S. was falling behind the Soviet Union (which led to more homework), only to resurface in the 1960s and ’70s, when a more open culture came to see homework as stifling play and creativity (which led to less). But this didn’t last either: In the ’80s, government researchers blamed America’s schools for its economic troubles and recommended ramping homework up once more.

The 21st century has so far been a homework-heavy era, with American teenagers now averaging about twice as much time spent on homework each day as their predecessors did in the 1990s . Even little kids are asked to bring school home with them. A 2015 study , for instance, found that kindergarteners, who researchers tend to agree shouldn’t have any take-home work, were spending about 25 minutes a night on it.

But not without pushback. As many children, not to mention their parents and teachers, are drained by their daily workload, some schools and districts are rethinking how homework should work—and some teachers are doing away with it entirely. They’re reviewing the research on homework (which, it should be noted, is contested) and concluding that it’s time to revisit the subject.

Read: My daughter’s homework is killing me

Hillsborough, California, an affluent suburb of San Francisco, is one district that has changed its ways. The district, which includes three elementary schools and a middle school, worked with teachers and convened panels of parents in order to come up with a homework policy that would allow students more unscheduled time to spend with their families or to play. In August 2017, it rolled out an updated policy, which emphasized that homework should be “meaningful” and banned due dates that fell on the day after a weekend or a break.

“The first year was a bit bumpy,” says Louann Carlomagno, the district’s superintendent. She says the adjustment was at times hard for the teachers, some of whom had been doing their job in a similar fashion for a quarter of a century. Parents’ expectations were also an issue. Carlomagno says they took some time to “realize that it was okay not to have an hour of homework for a second grader—that was new.”

Most of the way through year two, though, the policy appears to be working more smoothly. “The students do seem to be less stressed based on conversations I’ve had with parents,” Carlomagno says. It also helps that the students performed just as well on the state standardized test last year as they have in the past.

Earlier this year, the district of Somerville, Massachusetts, also rewrote its homework policy, reducing the amount of homework its elementary and middle schoolers may receive. In grades six through eight, for example, homework is capped at an hour a night and can only be assigned two to three nights a week.

Jack Schneider, an education professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell whose daughter attends school in Somerville, is generally pleased with the new policy. But, he says, it’s part of a bigger, worrisome pattern. “The origin for this was general parental dissatisfaction, which not surprisingly was coming from a particular demographic,” Schneider says. “Middle-class white parents tend to be more vocal about concerns about homework … They feel entitled enough to voice their opinions.”

Schneider is all for revisiting taken-for-granted practices like homework, but thinks districts need to take care to be inclusive in that process. “I hear approximately zero middle-class white parents talking about how homework done best in grades K through two actually strengthens the connection between home and school for young people and their families,” he says. Because many of these parents already feel connected to their school community, this benefit of homework can seem redundant. “They don’t need it,” Schneider says, “so they’re not advocating for it.”

That doesn’t mean, necessarily, that homework is more vital in low-income districts. In fact, there are different, but just as compelling, reasons it can be burdensome in these communities as well. Allison Wienhold, who teaches high-school Spanish in the small town of Dunkerton, Iowa, has phased out homework assignments over the past three years. Her thinking: Some of her students, she says, have little time for homework because they’re working 30 hours a week or responsible for looking after younger siblings.

As educators reduce or eliminate the homework they assign, it’s worth asking what amount and what kind of homework is best for students. It turns out that there’s some disagreement about this among researchers, who tend to fall in one of two camps.

In the first camp is Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. Cooper conducted a review of the existing research on homework in the mid-2000s , and found that, up to a point, the amount of homework students reported doing correlates with their performance on in-class tests. This correlation, the review found, was stronger for older students than for younger ones.

This conclusion is generally accepted among educators, in part because it’s compatible with “the 10-minute rule,” a rule of thumb popular among teachers suggesting that the proper amount of homework is approximately 10 minutes per night, per grade level—that is, 10 minutes a night for first graders, 20 minutes a night for second graders, and so on, up to two hours a night for high schoolers.

In Cooper’s eyes, homework isn’t overly burdensome for the typical American kid. He points to a 2014 Brookings Institution report that found “little evidence that the homework load has increased for the average student”; onerous amounts of homework, it determined, are indeed out there, but relatively rare. Moreover, the report noted that most parents think their children get the right amount of homework, and that parents who are worried about under-assigning outnumber those who are worried about over-assigning. Cooper says that those latter worries tend to come from a small number of communities with “concerns about being competitive for the most selective colleges and universities.”

According to Alfie Kohn, squarely in camp two, most of the conclusions listed in the previous three paragraphs are questionable. Kohn, the author of The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing , considers homework to be a “reliable extinguisher of curiosity,” and has several complaints with the evidence that Cooper and others cite in favor of it. Kohn notes, among other things, that Cooper’s 2006 meta-analysis doesn’t establish causation, and that its central correlation is based on children’s (potentially unreliable) self-reporting of how much time they spend doing homework. (Kohn’s prolific writing on the subject alleges numerous other methodological faults.)

In fact, other correlations make a compelling case that homework doesn’t help. Some countries whose students regularly outperform American kids on standardized tests, such as Japan and Denmark, send their kids home with less schoolwork , while students from some countries with higher homework loads than the U.S., such as Thailand and Greece, fare worse on tests. (Of course, international comparisons can be fraught because so many factors, in education systems and in societies at large, might shape students’ success.)

Kohn also takes issue with the way achievement is commonly assessed. “If all you want is to cram kids’ heads with facts for tomorrow’s tests that they’re going to forget by next week, yeah, if you give them more time and make them do the cramming at night, that could raise the scores,” he says. “But if you’re interested in kids who know how to think or enjoy learning, then homework isn’t merely ineffective, but counterproductive.”

His concern is, in a way, a philosophical one. “The practice of homework assumes that only academic growth matters, to the point that having kids work on that most of the school day isn’t enough,” Kohn says. What about homework’s effect on quality time spent with family? On long-term information retention? On critical-thinking skills? On social development? On success later in life? On happiness? The research is quiet on these questions.

Another problem is that research tends to focus on homework’s quantity rather than its quality, because the former is much easier to measure than the latter. While experts generally agree that the substance of an assignment matters greatly (and that a lot of homework is uninspiring busywork), there isn’t a catchall rule for what’s best—the answer is often specific to a certain curriculum or even an individual student.

Given that homework’s benefits are so narrowly defined (and even then, contested), it’s a bit surprising that assigning so much of it is often a classroom default, and that more isn’t done to make the homework that is assigned more enriching. A number of things are preserving this state of affairs—things that have little to do with whether homework helps students learn.

Jack Schneider, the Massachusetts parent and professor, thinks it’s important to consider the generational inertia of the practice. “The vast majority of parents of public-school students themselves are graduates of the public education system,” he says. “Therefore, their views of what is legitimate have been shaped already by the system that they would ostensibly be critiquing.” In other words, many parents’ own history with homework might lead them to expect the same for their children, and anything less is often taken as an indicator that a school or a teacher isn’t rigorous enough. (This dovetails with—and complicates—the finding that most parents think their children have the right amount of homework.)

Barbara Stengel, an education professor at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College, brought up two developments in the educational system that might be keeping homework rote and unexciting. The first is the importance placed in the past few decades on standardized testing, which looms over many public-school classroom decisions and frequently discourages teachers from trying out more creative homework assignments. “They could do it, but they’re afraid to do it, because they’re getting pressure every day about test scores,” Stengel says.

Second, she notes that the profession of teaching, with its relatively low wages and lack of autonomy, struggles to attract and support some of the people who might reimagine homework, as well as other aspects of education. “Part of why we get less interesting homework is because some of the people who would really have pushed the limits of that are no longer in teaching,” she says.

“In general, we have no imagination when it comes to homework,” Stengel says. She wishes teachers had the time and resources to remake homework into something that actually engages students. “If we had kids reading—anything, the sports page, anything that they’re able to read—that’s the best single thing. If we had kids going to the zoo, if we had kids going to parks after school, if we had them doing all of those things, their test scores would improve. But they’re not. They’re going home and doing homework that is not expanding what they think about.”