Document Analysis

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Benjamin Kutsyuruba 4

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

4921 Accesses

2 Citations

This chapter describes the document analysis approach. As a qualitative method, document analysis entails a systematic procedure for reviewing and evaluating documents through finding, selecting, appraising (making sense of), and synthesizing data contained within them. This chapter outlines the brief history, method and use of document analysis, provides an outline of its process, strengths and limitations, and application, and offers further readings, resources, and suggestions for student engagement activities.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Altheide, D. L. (1987). Ethnographic content analysis. Qualitative Sociology, 10 (1), 65–77.

Article Google Scholar

Altheide, D. L. (1996). Qualitative media analysis . SAGE.

Google Scholar

Altheide, D. L. (2000). Tracking discourse and qualitative document analysis. Poetics, 27 , 287–299.

Atkinson, P. A., & Coffey, A. (1997). Analysing documentary realities. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research: Theory, method and practice (pp. 45–62). SAGE.

Berg, B. L. (2001). Qualitative research methods for social sciences . Allyn and Bacon.

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9 (2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/qrj0902027

Bryman, A. (2003). Research methods and organization studies . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Cardno, C. (2018). Policy document analysis: A practical educational leadership tool and a qualitative research method. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice , 24 (4), 623–640. https://doi.org/10.14527/kuey.2018.016

Caulley, D. N. (1983). Document analysis in program evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 6 , 19–29.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Derrida, J. (1978). Writing and difference . Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Aldine De Gruyter.

Glesne, C., & Peshkin, A. (1992). Becoming qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Longman.

Goode, W. J., & Hatt, P. K. (1952). Methods in social research . McGraw-Hill.

Hodder, I. (2000). The interpretation of documents and material culture. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 703–715). SAGE.

Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. SAGE.

Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., & Bracken, C. C. (2002). Content analysis in mass communication: Assessment and reporting of intercoder reliability. Human Communication Research, 28 , 587–604.

Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., & Bracken, C. C. (2010). Practical resources for assessing and reporting intercoder reliability in content analysis research projects . Retrieved March 20, 2011, from http://matthewlombard.com/reliability/index_print.html

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative social research (Vol. 1(2)). Retrieved March 22, 2011, from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/viewArticle/1089/2385

McMillan, J. H., & Schumacher, S. (2010). Research in education: Evidence-based inquiry (7th ed.). Pearson.

Merriam, S. B. (1988a). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach . Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S. B. (1998b). Case study research in education . Jossey-Bass.

Miller, F. A., & Alvarado, K. (2005). Incorporating documents into qualitative nursing research. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 37 (4), 348–353.

Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook . SAGE.

O’Leary, Z. (2014). The essential guide to doing your research project (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Prior, L. (2003). Using documents in social research . SAGE.

Prior, L. (2008a). Document analysis. In L. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopaedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 231–232). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909

Prior, L. (2008b). Repositioning documents in social research. Sociology, 42 (5), 821–836. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038508094564

Prior, L. (2012). The role of documents in social research. In S. Delamont (Ed.), Handbook of qualitative research in education (pp. 426–438). Edward Elgar.

Salminen, A., Kauppinen, K., & Lehtovaara, M. (1997). Towards a methodology for document analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48 (7), 644–655.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research . SAGE.

Wharton, C. (2006). Document analysis. In V. Jupp (Ed.), The SAGE dictionary of social research methods (pp. 80–81). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020116

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research, design and methods (4th ed.). SAGE.

Additional Reading

Kutsyuruba, B. (2017). Examining education reforms through document analysis methodology. In I. Silova, A. Korzh, S. Kovalchuk, & N. Sobe (Eds.), Reimagining Utopias: Theory and method for educational research in post-socialist contexts (pp. 199–214). Sense.

Kutsyuruba, B., Christou, T., Heggie, L., Murray, J., & Deluca, C. (2015). Teacher collaborative inquiry in Ontario: An analysis of provincial and school board policies and support documents. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 172 , 1–38.

Kutsyuruba, B., Godden, L., & Tregunna, L. (2014). Curbing the early-career attrition: A pan-Canadian document analysis of teacher induction and mentorship programs. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 161 , 1–42.

Segeren, A., & Kutsyuruba, B. (2012). Twenty years and counting: An examination of the development of equity and inclusive education policy in Ontario (1990–2010). Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 136 , 1–38.

Online Resources

Document Analysis: A How To Guide (12:27 min) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vOsE9saR_ck

Document Analysis with Philip Adu (1:16:40 min) https://youtu.be/bLKBffW5JPU

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

Benjamin Kutsyuruba

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Benjamin Kutsyuruba .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Administration, College of Education, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Janet Mola Okoko

Scott Tunison

Department of Educational Administration, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Keith D. Walker

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Kutsyuruba, B. (2023). Document Analysis. In: Okoko, J.M., Tunison, S., Walker, K.D. (eds) Varieties of Qualitative Research Methods. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_23

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_23

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-04396-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-04394-9

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Open Access Articles

- Research Collections

- Review Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Health Policy and Planning

- About the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- HPP at a glance

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, what is document analysis, the read approach, supplementary data, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Document analysis in health policy research: the READ approach

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

Sarah L Dalglish, Hina Khalid, Shannon A McMahon, Document analysis in health policy research: the READ approach, Health Policy and Planning , Volume 35, Issue 10, December 2020, Pages 1424–1431, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa064

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Document analysis is one of the most commonly used and powerful methods in health policy research. While existing qualitative research manuals offer direction for conducting document analysis, there has been little specific discussion about how to use this method to understand and analyse health policy. Drawing on guidance from other disciplines and our own research experience, we present a systematic approach for document analysis in health policy research called the READ approach: (1) ready your materials, (2) extract data, (3) analyse data and (4) distil your findings. We provide practical advice on each step, with consideration of epistemological and theoretical issues such as the socially constructed nature of documents and their role in modern bureaucracies. We provide examples of document analysis from two case studies from our work in Pakistan and Niger in which documents provided critical insight and advanced empirical and theoretical understanding of a health policy issue. Coding tools for each case study are included as Supplementary Files to inspire and guide future research. These case studies illustrate the value of rigorous document analysis to understand policy content and processes and discourse around policy, in ways that are either not possible using other methods, or greatly enrich other methods such as in-depth interviews and observation. Given the central nature of documents to health policy research and importance of reading them critically, the READ approach provides practical guidance on gaining the most out of documents and ensuring rigour in document analysis.

Rigour in qualitative research is judged partly by the use of deliberate, systematic procedures; however, little specific guidance is available for analysing documents, a nonetheless common method in health policy research.

Document analysis is useful for understanding policy content across time and geographies, documenting processes, triangulating with interviews and other sources of data, understanding how information and ideas are presented formally, and understanding issue framing, among other purposes.

The READ (Ready materials, Extract data, Analyse data, Distil) approach provides a step-by-step guide to conducting document analysis for qualitative policy research.

The READ approach can be adapted to different purposes and types of research, two examples of which are presented in this article, with sample tools in the Supplementary Materials .

Document analysis (also called document review) is one of the most commonly used methods in health policy research; it is nearly impossible to conduct policy research without it. Writing in early 20th century, Weber (2015) identified the importance of formal, written documents as a key characteristic of the bureaucracies by which modern societies function, including in public health. Accordingly, critical social research has a long tradition of documentary review: Marx analysed official reports, laws, statues, census reports and newspapers and periodicals over a nearly 50-year period to come to his world-altering conclusions ( Harvey, 1990 ). Yet in much of social science research, ‘documents are placed at the margins of consideration,’ with privilege given to the spoken word via methods such as interviews, possibly due to the fact that many qualitative methods were developed in the anthropological tradition to study mainly pre-literate societies ( Prior, 2003 ). To date, little specific guidance is available to help health policy researchers make the most of these wells of information.

The term ‘documents’ is defined here broadly, following Prior, as physical or virtual artefacts designed by creators, for users, to function within a particular setting ( Prior, 2003 ). Documents exist not as standalone objects of study but must be understood in the social web of meaning within which they are produced and consumed. For example, some analysts distinguish between public documents (produced in the context of public sector activities), private documents (from business and civil society) and personal documents (created by or for individuals, and generally not meant for public consumption) ( Mogalakwe, 2009 ). Documents can be used in a number of ways throughout the research process ( Bowen, 2009 ). In the planning or study design phase, they can be used to gather background information and help refine the research question. Documents can also be used to spark ideas for disseminating research once it is complete, by observing the ways those who will use the research speak to and communicate ideas with one another.

Documents can also be used during data collection and analysis to help answer research questions. Recent health policy research shows that this can be done in at least four ways. Frequently, policy documents are reviewed to describe the content or categorize the approaches to specific health problems in existing policies, as in reviews of the composition of drowning prevention resources in the United States or policy responses to foetal alcohol spectrum disorder in South Africa ( Katchmarchi et al. , 2018 ; Adebiyi et al. , 2019 ). In other cases, non-policy documents are used to examine the implementation of health policies in real-world settings, as in a review of web sources and newspapers analysing the functioning of community health councils in New Zealand ( Gurung et al. , 2020 ). Perhaps less frequently, document analysis is used to analyse policy processes, as in an assessment of multi-sectoral planning process for nutrition in Burkina Faso ( Ouedraogo et al. , 2020 ). Finally, and most broadly, document analysis can be used to inform new policies, as in one study that assessed cigarette sticks as communication and branding ‘documents,’ to suggest avenues for further regulation and tobacco control activities ( Smith et al. , 2017 ).

This practice paper provides an overarching method for conducting document analysis, which can be adapted to a multitude of research questions and topics. Document analysis is used in most or all policy studies; the aim of this article is to provide a systematized method that will enhance procedural rigour. We provide an overview of document analysis, drawing on guidance from disciplines adjacent to public health, introduce the ‘READ’ approach to document analysis and provide two short case studies demonstrating how document analysis can be applied.

Document analysis is a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents, which can be used to provide context, generate questions, supplement other types of research data, track change over time and corroborate other sources ( Bowen, 2009 ). In one commonly cited approach in social research, Bowen recommends first skimming the documents to get an overview, then reading to identify relevant categories of analysis for the overall set of documents and finally interpreting the body of documents ( Bowen, 2009 ). Document analysis can include both quantitative and qualitative components: the approach presented here can be used with either set of methods, but we emphasize qualitative ones, which are more adapted to the socially constructed meaning-making inherent to collaborative exercises such as policymaking.

The study of documents as a research method is common to a number of social science disciplines—yet in many of these fields, including sociology ( Mogalakwe, 2009 ), anthropology ( Prior, 2003 ) and political science ( Wesley, 2010 ), document-based research is described as ill-considered and underutilized. Unsurprisingly, textual analysis is perhaps most developed in fields such as media studies, cultural studies and literary theory, all disciplines that recognize documents as ‘social facts’ that are created, consumed, shared and utilized in socially organized ways ( Atkinson and Coffey, 1997 ). Documents exist within social ‘fields of action,’ a term used to designate the environments within which individuals and groups interact. Documents are therefore not mere records of social life, but integral parts of it—and indeed can become agents in their own right ( Prior, 2003 ). Powerful entities also manipulate the nature and content of knowledge; therefore, gaps in available information must be understood as reflecting and potentially reinforcing societal power relations ( Bryman and Burgess, 1994 ).

Document analysis, like any research method, can be subject to concerns regarding validity, reliability, authenticity, motivated authorship, lack of representativity and so on. However, these can be mitigated or avoided using standard techniques to enhance qualitative rigour, such as triangulation (within documents and across methods and theoretical perspectives), ensuring adequate sample size or ‘engagement’ with the documents, member checking, peer debriefing and so on ( Maxwell, 2005 ).

Document analysis can be used as a standalone method, e.g. to analyse the contents of specific types of policy as they evolve over time and differ across geographies, but document analysis can also be powerfully combined with other types of methods to cross-validate (i.e. triangulate) and deepen the value of concurrent methods. As one guide to public policy research puts it, ‘almost all likely sources of information, data, and ideas fall into two general types: documents and people’ ( Bardach and Patashnik, 2015 ). Thus, researchers can ask interviewees to address questions that arise from policy documents and point the way to useful new documents. Bardach and Patashnik suggest alternating between documents and interviews as sources as information, as one tends to lead to the other, such as by scanning interviewees’ bookshelves and papers for titles and author names ( Bardach and Patashnik, 2015 ). Depending on your research questions, document analysis can be used in combination with different types of interviews ( Berner-Rodoreda et al. , 2018 ), observation ( Harvey, 2018 ), and quantitative analyses, among other common methods in policy research.

The READ approach to document analysis is a systematic procedure for collecting documents and gaining information from them in the context of health policy studies at any level (global, national, local, etc.). The steps consist of: (1) ready your materials, (2) extract data, (3) analyse data and (4) distil your findings. We describe each of these steps in turn.

Step 1. Ready your materials

At the outset, researchers must set parameters in terms of the nature and number (approximately) of documents they plan to analyse, based on the research question. How much time will you allocate to the document analysis, and what is the scope of your research question? Depending on the answers to these questions, criteria should be established around (1) the topic (a particular policy, programme, or health issue, narrowly defined according to the research question); (2) dates of inclusion (whether taking the long view of several decades, or zooming in on a specific event or period in time); and (3) an indicative list of places to search for documents (possibilities include databases such as Ministry archives; LexisNexis or other databases; online searches; and particularly interview subjects). For difficult-to-obtain working documents or otherwise non-public items, bringing a flash drive to interviews is one of the best ways to gain access to valuable documents.

For research focusing on a single policy or programme, you may review only a handful of documents. However, if you are looking at multiple policies, health issues, or contexts, or reviewing shorter documents (such as newspaper articles), you may look at hundreds, or even thousands of documents. When considering the number of documents you will analyse, you should make notes on the type of information you plan to extract from documents—i.e. what it is you hope to learn, and how this will help answer your research question(s). The initial criteria—and the data you seek to extract from documents—will likely evolve over the course of the research, as it becomes clear whether they will yield too few documents and information (a rare outcome), far too many documents and too much information (a much more common outcome) or documents that fail to address the research question; however, it is important to have a starting point to guide the search. If you find that the documents you need are unavailable, you may need to reassess your research questions or consider other methods of inquiry. If you have too many documents, you can either analyse a subset of these ( Panel 1 ) or adopt more stringent inclusion criteria.

Exploring the framing of diseases in Pakistani media

In Table 1 , we present a non-exhaustive list of the types of documents that can be included in document analyses of health policy issues. In most cases, this will mean written sources (policies, reports, articles). The types of documents to be analysed will vary by study and according to the research question, although in many cases, it will be useful to consult a mix of formal documents (such as official policies, laws or strategies), ‘gray literature’ (organizational materials such as reports, evaluations and white papers produced outside formal publication channels) and, whenever possible, informal or working documents (such as meeting notes, PowerPoint presentations and memoranda). These latter in particular can provide rich veins of insight into how policy actors are thinking through the issues under study, particularly for the lucky researcher who obtains working documents with ‘Track Changes.’ How you prioritize documents will depend on your research question: you may prioritize official policy documents if you are studying policy content, or you may prioritize informal documents if you are studying policy process.

Types of documents that can be consulted in studies of health policy

During this initial preparatory phase, we also recommend devising a file-naming system for your documents (e.g. Author.Date.Topic.Institution.PDF), so that documents can be easily retrieved throughout the research process. After extracting data and processing your documents the first time around, you will likely have additional ‘questions’ to ask your documents and need to consult them again. For this reason, it is important to clearly name source files and link filenames to the data that you are extracting (see sample naming conventions in the Supplementary Materials ).

Step 2. Extract data

Data can be extracted in a number of ways, and the method you select for doing so will depend on your research question and the nature of your documents. One simple way is to use an Excel spreadsheet where each row is a document and each column is a category of information you are seeking to extract, from more basic data such as the document title, author and date, to theoretical or conceptual categories deriving from your research question, operating theory or analytical framework (Panel 2). Documents can also be imported into thematic coding software such as Atlas.ti or NVivo, and data extracted that way. Alternatively, if the research question focuses on process, documents can be used to compile a timeline of events, to trace processes across time. Ask yourself, how can I organize these data in the most coherent manner? What are my priority categories? We have included two different examples of data extraction tools in the Supplementary Materials to this article to spark ideas.

Case study Documents tell part of the story in Niger

Document analyses are first and foremost exercises in close reading: documents should be read thoroughly, from start to finish, including annexes, which may seem tedious but which sometimes produce golden nuggets of information. Read for overall meaning as you extract specific data related to your research question. As you go along, you will begin to have ideas or build working theories about what you are learning and observing in the data. We suggest capturing these emerging theories in extended notes or ‘memos,’ as used in Grounded Theory methodology ( Charmaz, 2006 ); these can be useful analytical units in themselves and can also provide a basis for later report and article writing.

As you read more documents, you may find that your data extraction tool needs to be modified to capture all the relevant information (or to avoid wasting time capturing irrelevant information). This may require you to go back and seek information in documents you have already read and processed, which will be greatly facilitated by a coherent file-naming system. It is also useful to keep notes on other documents that are mentioned that should be tracked down (sometimes you can write the author for help). As a general rule, we suggest being parsimonious when selecting initial categories to extract from data. Simply reading the documents takes significant time in and of itself—make sure you think about how, exactly, the specific data you are extracting will be used and how it goes towards answering your research questions.

Step 3. Analyse data

As in all types of qualitative research, data collection and analysis are iterative and characterized by emergent design, meaning that developing findings continually inform whether and how to obtain and interpret data ( Creswell, 2013 ). In practice, this means that during the data extraction phase, the researcher is already analysing data and forming initial theories—as well as potentially modifying document selection criteria. However, only when data extraction is complete can one see the full picture. For example, are there any documents that you would have expected to find, but did not? Why do you think they might be missing? Are there temporal trends (i.e. similarities, differences or evolutions that stand out when documents are ordered chronologically)? What else do you notice? We provide a list of overarching questions you should think about when viewing your body of document as a whole ( Table 2 ).

Questions to ask your overall body of documents

HIV and viral hepatitis articles by main frames (%). Note: The percentage of articles is calculated by dividing the number of articles appearing in each frame for viral hepatitis and HIV by the respectivenumber of sampled articles for each disease (N = 137 for HIV; N = 117 for hepatitis). Time frame: 1 January 2006 to 30 September 2016

Representations of progress toward Millennium Development Goal 4 in Nigerien policy documents. Sources: clockwise from upper left: ( WHO 2006 ); ( Institut National de la Statistique 2010 ); ( Ministè re de la Santé Publique 2010 ); ( Unicef 2010 )

In addition to the meaning-making processes you are already engaged in during the data extraction process, in most cases, it will be useful to apply specific analysis methodologies to the overall corpus of your documents, such as policy analysis ( Buse et al. , 2005 ). An array of analysis methodologies can be used, both quantitative and qualitative, including case study methodology, thematic content analysis, discourse analysis, framework analysis and process tracing, which may require differing levels of familiarity and skills to apply (we highlight a few of these in the case studies below). Analysis can also be structured according to theoretical approaches. When it comes to analysing policies, process tracing can be particularly useful to combine multiple sources of information, establish a chronicle of events and reveal political and social processes, so as to create a narrative of the policy cycle ( Yin, 1994 ; Shiffman et al. , 2004 ). Practically, you will also want to take a holistic view of the documents’ ‘answers’ to the questions or analysis categories you applied during the data extraction phase. Overall, what did the documents ‘say’ about these thematic categories? What variation did you find within and between documents, and along which axes? Answers to these questions are best recorded by developing notes or memos, which again will come in handy as you write up your results.

As with all qualitative research, you will want to consider your own positionality towards the documents (and their sources and authors); it may be helpful to keep a ‘reflexivity’ memo documenting how your personal characteristics or pre-standing views might influence your analysis ( Watt, 2007 ).

Step 4. Distil your findings

You will know when you have completed your document review when one of the three things happens: (1) completeness (you feel satisfied you have obtained every document fitting your criteria—this is rare), (2) out of time (this means you should have used more specific criteria), and (3) saturation (you fully or sufficiently understand the phenomenon you are studying). In all cases, you should strive to make the third situation the reason for ending your document review, though this will not always mean you will have read and analysed every document fitting your criteria—just enough documents to feel confident you have found good answers to your research questions.

Now it is time to refine your findings. During the extraction phase, you did the equivalent of walking along the beach, noticing the beautiful shells, driftwood and sea glass, and picking them up along the way. During the analysis phase, you started sorting these items into different buckets (your analysis categories) and building increasingly detailed collections. Now you have returned home from the beach, and it is time to clean your objects, rinse them of sand and preserve only the best specimens for presentation. To do this, you can return to your memos, refine them, illustrate them with graphics and quotes and fill in any incomplete areas. It can also be illuminating to look across different strands of work: e.g. how did the content, style, authorship, or tone of arguments evolve over time? Can you illustrate which words, concepts or phrases were used by authors or author groups?

Results will often first be grouped by theoretical or analytic category, or presented as a policy narrative, interweaving strands from other methods you may have used (interviews, observation, etc.). It can also be helpful to create conceptual charts and graphs, especially as this corresponds to your analytical framework (Panels 1 and 2). If you have been keeping a timeline of events, you can seek out any missing information from other sources. Finally, ask yourself how the validity of your findings checks against what you have learned using other methods. The final products of the distillation process will vary by research study, but they will invariably allow you to state your findings relative to your research questions and to draw policy-relevant conclusions.

Document analysis is an essential component of health policy research—it is also relatively convenient and can be low cost. Using an organized system of analysis enhances the document analysis’s procedural rigour, allows for a fuller understanding of policy process and content and enhances the effectiveness of other methods such as interviews and non-participant observation. We propose the READ approach as a systematic method for interrogating documents and extracting study-relevant data that is flexible enough to accommodate many types of research questions. We hope that this article encourages discussion about how to make best use of data from documents when researching health policy questions.

Supplementary data are available at Health Policy and Planning online.

The data extraction tool in the Supplementary Materials for the iCCM case study (Panel 2) was conceived of by the research team for the multi-country study ‘Policy Analysis of Community Case Management for Childhood and Newborn Illnesses’. The authors thank Sara Bennett and Daniela Rodriguez for granting permission to publish this tool. S.M. was supported by The Olympia-Morata-Programme of Heidelberg University. The funders had no role in the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of any funder.

Conflict of interest statement . None declared.

Ethical approval. No ethical approval was required for this study.

Abdelmutti N , Hoffman-Goetz L. 2009 . Risk messages about HPV, cervical cancer, and the HPV vaccine Gardasil: a content analysis of Canadian and U.S. national newspaper articles . Women & Health 49 : 422 – 40 .

Google Scholar

Adebiyi BO , Mukumbang FC , Beytell A-M. 2019 . To what extent is fetal alcohol spectrum disorder considered in policy-related documents in South Africa? A document review . Health Research Policy and Systems 17 :

Atkinson PA , Coffey A. 1997 . Analysing documentary realities. In: Silverman D (ed). Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice . London : SAGE .

Google Preview

Bardach E , Patashnik EM. 2015 . Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving . Los Angeles : SAGE .

Bennett S , Dalglish SL , Juma PA , Rodríguez DC. 2015 . Altogether now… understanding the role of international organizations in iCCM policy transfer . Health Policy and Planning 30 : ii26 – 35 .

Berner-Rodoreda A , Bärnighausen T , Kennedy C et al. 2018 . From doxastic to epistemic: a typology and critique of qualitative interview styles . Qualitative Inquiry 26 : 291 – 305 . 1077800418810724.

Bowen GA. 2009 . Document analysis as a qualitative research method . Qualitative Research Journal 9 : 27 – 40 .

Bryman A. 1994 . Analyzing Qualitative Data .

Buse K , Mays N , Walt G. 2005 . Making Health Policy . New York : Open University Press .

Charmaz K. 2006 . Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis . London : SAGE .

Claassen L , Smid T , Woudenberg F , Timmermans DRM. 2012 . Media coverage on electromagnetic fields and health: content analysis of Dutch newspaper articles and websites . Health, Risk & Society 14 : 681 – 96 .

Creswell JW. 2013 . Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design . Thousand Oaks, CA : SAGE .

Dalglish SL , Rodríguez DC , Harouna A , Surkan PJ. 2017 . Knowledge and power in policy-making for child survival in Niger . Social Science & Medicine 177 : 150 – 7 .

Dalglish SL , Surkan PJ , Diarra A , Harouna A , Bennett S. 2015 . Power and pro-poor policies: the case of iCCM in Niger . Health Policy and Planning 30 : ii84 – 94 .

Entman RM. 1993 . Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm . Journal of Communication 43 : 51 – 8 .

Fournier G , Djermakoye IA. 1975 . Village health teams in Niger (Maradi Department). In: Newell KW (ed). Health by the People . Geneva : WHO .

Gurung G , Derrett S , Gauld R. 2020 . The role and functions of community health councils in New Zealand’s health system: a document analysis . The New Zealand Medical Journal 133 : 70 – 82 .

Harvey L. 1990 . Critical Social Research . London : Unwin Hyman .

Harvey SA. 2018 . Observe before you leap: why observation provides critical insights for formative research and intervention design that you’ll never get from focus groups, interviews, or KAP surveys . Global Health: Science and Practice 6 : 299 – 316 .

Institut National de la Statistique. 2010. Rapport National sur les Progrès vers l'atteinte des Objectifs du Millénaire pour le Développement. Niamey, Niger: INS.

Kamarulzaman A. 2013 . Fighting the HIV epidemic in the Islamic world . Lancet 381 : 2058 – 60 .

Katchmarchi AB , Taliaferro AR , Kipfer HJ. 2018 . A document analysis of drowning prevention education resources in the United States . International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion 25 : 78 – 84 .

Krippendorff K. 2004 . Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology . SAGE .

Marten R. 2019 . How states exerted power to create the Millennium Development Goals and how this shaped the global health agenda: lessons for the sustainable development goals and the future of global health . Global Public Health 14 : 584 – 99 .

Maxwell JA. 2005 . Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach , 2 nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage Publications .

Mayring P. 2004 . Qualitative Content Analysis . In: Flick U, von Kardorff E, Steinke I (eds). A Companion to Qualitative Research . SAGE .

Ministère de la Santé Publique. 2010. Enquête nationale sur la survie des enfants de 0 à 59 mois et la mortalité au Niger 2010. Niamey, Niger: MSP.

Mogalakwe M. 2009 . The documentary research method—using documentary sources in social research . Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review 25 : 43 – 58 .

Nelkin D. 1991 . AIDS and the news media . The Milbank Quarterly 69 : 293 – 307 .

Ouedraogo O , Doudou MH , Drabo KM et al. 2020 . Policy overview of the multisectoral nutrition planning process: the progress, challenges, and lessons learned from Burkina Faso . The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 35 : 120 – 39 .

Prior L. 2003 . Using Documents in Social Research . London: SAGE .

Shiffman J , Stanton C , Salazar AP. 2004 . The emergence of political priority for safe motherhood in Honduras . Health Policy and Planning 19 : 380 – 90 .

Smith KC , Washington C , Welding K et al. 2017 . Cigarette stick as valuable communicative real estate: a content analysis of cigarettes from 14 low-income and middle-income countries . Tobacco Control 26 : 604 – 7 .

Strömbäck J , Dimitrova DV. 2011 . Mediatization and media interventionism: a comparative analysis of Sweden and the United States . The International Journal of Press/Politics 16 : 30 – 49 .

UNICEF. 2010. Maternal, Newborn & Child Surival Profile. Niamey, Niger: UNICEF

Watt D. 2007 . On becoming a qualitative researcher: the value of reflexivity . Qualitative Report 12 : 82 – 101 .

Weber M. 2015 . Bureaucracy. In: Waters T , Waters D (eds). Rationalism and Modern Society: New Translations on Politics, Bureaucracy, and Social Stratification . London : Palgrave MacMillan .

Wesley JJ. 2010 . Qualitative Document Analysis in Political Science.

World Health Organization. 2006. Country Health System Fact Sheet 2006: Niger. Niamey, Niger: WHO.

Yin R. 1994 . Case Study Research: Design and Methods . Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage .

Supplementary data

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2237

- Copyright © 2024 The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Documentary Research: What it is, methodology & free examples

Social scientists often conduct documentary research. Its primary use is to assess various documents in the interest of social or historical value. Researchers also conduct documentary research to study multiple documents surrounding events or individuals.

What is documentary research?

Documentary research is the research conducted through the use of official documents or personal documents as the source of information.

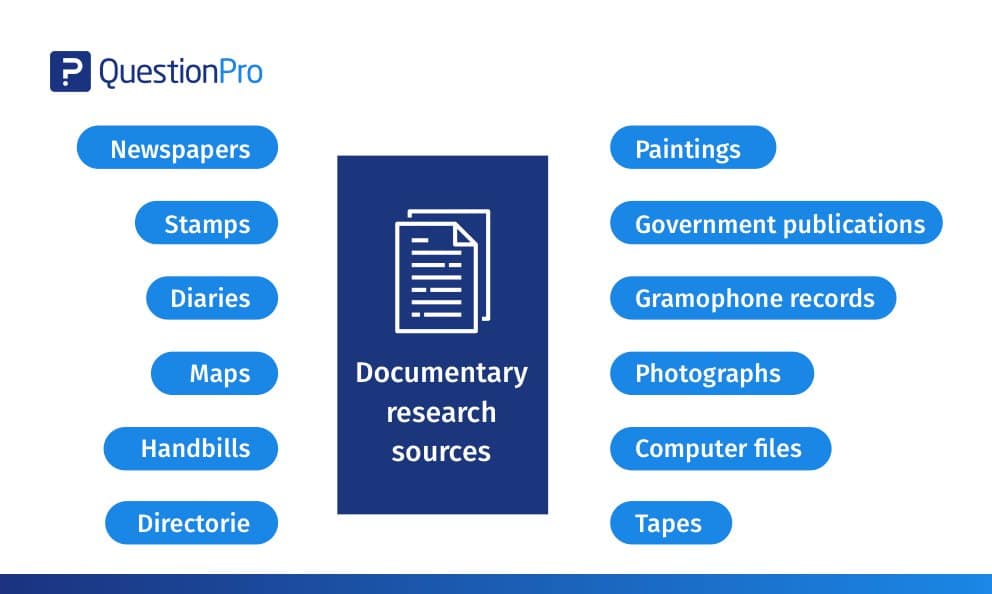

Documents can include anything from the following:

- Directories

- Government statistical publications

- Gramophone records

- Photographs

- Computer files

The above may not fit the traditional bill of a “document”, but companies can use them towards documentary research since they contain information.

Documentary research is similar to content analysis, which involves studying existing information recorded in media, texts, and physical items. Here, data collection from people is not required to conduct research. Hence, this is a prime example of secondary research.

It is essential to consider the quality of the documents while using it as evidence on social relations and social meanings. Keep in mind that, unlike surveys and research interviews, the records are originally published/generated without keeping the purpose of research in mind. It is good practice to cross-verify documents against other similar documents before reaching a decision.

Documentary research examples

Bellow, we can find a few real-life examples of documentary research applied to companies’ daily events.

1. Social research studies

Although documentary research is not used extensively today, it is the go-to research method to conduct social research studies. For example, Karl Marx and Emile Durkheim used documentary research extensively for their research.

Karl Marx used documents like:

- Her Majesty Inspectors of Factories Reports

- Royal Commission

- Inland Revenue Reports

There’s also a record of his use of reports by the Medical Officer of the Privy Council, reports on children’s employment in factories, the Corn-laws, the Banking Acts, and Census Reports for Wales and England to name a few.

Durkheim, one of the founders of Sociology, wrote a book on suicide, which is recognized as the first modern example of a methodical and consistent use of documents for social research.

2. Archival inquiry

The field of sociology has a popular, longstanding tradition of documentary inquiry. Many historians refer to and rely on primary documents for their research. Historians give historical documents more emphasis while conducting research. Of course, as we evolve, virtual documents like emails will play a significant role in research activities conducted by these researchers.

3. Aesthetic interpretation

Documentary research is not limited to text only. Pictures, paintings, videos, audio files, monuments are also used to conduct research. Documentary researchers use these tools in addition to texts while studying social sciences. The use of these tools adds to the authenticity of the textual research, or may very well point out deviations in the findings.

This deviation suggests that investigators research more to draw accurate conclusions.

Documentary research methodology

Documentary research, if conducted thoroughly, can help develop a hypothesis or prove or disprove an existing theory. This of course depends on the methodology applied and the depth of research conducted. The researcher must conduct his/her own secondary research to analyze the contents before extracting it. They must handle the data scientifically.

Follow this four-step approach to control the quality of the content:

The authenticity of the documents

The credibility of the documents

Representativeness of the documents

The meaning derived from the documents

Let’s take a look at these in detail.

Authenticity implies whether the document’s origin is reliable, is the evidence genuine, are the intentions sincere, and what were the commitments to creating the document. The authenticity of the source is the primary criterion of documentary research.

Credibility means the subjective and objective components that make one believe the source of information and whether the data is free from distortion and error. The information must be trustworthy and must have some level of expertise.

Representativeness refers to whether the document represents a more extensive collection of the data point, and it is an aggregation of the topic being studied. That said, documents get distorted with time due to the inclusion of new factors, and a check has to be made to ensure the documents are representative.

Meaning means whether the findings are understandable and clear to be called evidence. The goal of examining documents is to understand its significance and meaning. Researchers must find out whether the document fits within the historical context or not.

Advantages of documentary study

Here are the advantages of the documentary research method:

- Data readily available: Data is readily available in various sources. You only need to know where to look and how to use it. The data is available in different forms, and harnessing it is the real challenge.

- Inexpensive and economical: The data for research is already collected and published in either print or other forms. The researcher does not need to spend money and time like they do to collect market research insights and gather data. They need to search for and compile the available data from different sources.

- Saves time: Conducting market research is time-consuming. Responses will not come in quickly as expected, and gathering global responses will take a huge amount of time. If you have all the reference documents available (or you know where to find them), research is relatively quick.

- Non-bias: Primary data collection tends to be biased. This bias depends on a lot of factors like the age of the respondents, the time they take the survey, their mentality while taking the survey, their gender, their feelings towards certain ideas, to name a few. The list goes on and on when it comes to surveying bias.

- A researcher is not necessary during data collection: The researcher doesn’t need to be present during data collection. It is practically impossible for the researcher to be present at every point of the data source, especially thinking about the various data sources.

- Useful for hypothesis: Use historical data to draw inferences of the current or future events. Conclusions can be drawn from the experience of past events and data available for them.

Disadvantages of the method

Here are the disadvantages of the documentary research method:

- Limited data: Data is not always available, especially when you need to cross-verify a theory or strengthen your argument based on different forms of data.

- Inaccuracies: As the data is historical and published, there is almost no way of ascertaining if the data is accurate or not.

- Incomplete documents: Often, documents can be incomplete, and there is no way of knowing if there are additional documents to refer to on the subject.

- Data out of context: The data that the researcher refers to may be out of context and may not be in line with the concept the researcher is trying to study. Its because the research goal is not thought of when creating the original data. Often, researchers have to make do with the available data at hand.

QuestionPro provides the best market research platform to uncover complex insights that can propel your business to the forefront of your industry.

START A FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Data Information vs Insight: Essential differences

May 14, 2024

Pricing Analytics Software: Optimize Your Pricing Strategy

May 13, 2024

Relationship Marketing: What It Is, Examples & Top 7 Benefits

May 8, 2024

The Best Email Survey Tool to Boost Your Feedback Game

May 7, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

No products in the cart.

The Basics of Document Analysis

Document analysis is the process of reviewing or evaluating documents both printed and electronic in a methodical manner. The document analysis method, like many other qualitative research methods, involves examining and interpreting data to uncover meaning, gain understanding, and come to a conclusion.

What is Meant by Document Analysis?

Document analysis pertains to the process of interpreting documents for an assessment topic by the researcher as a means of giving voice and meaning. In Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method by Glenn A. Bowen , document analysis is described as, “... a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents—both printed and electronic (computer-based and Internet-transmitted) material. Like other analytical methods in qualitative research, document analysis requires that data be examined and interpreted in order to elicit meaning, gain understanding, and develop empirical knowledge.”

During the analysis of documents, the content is categorized into distinct themes, similar to the way transcripts from interviews or focus groups are analyzed. The documents may also be graded or scored using a rubric.

Document analysis is a social research method of great value, and it plays a crucial role in most triangulation methods, combining various methods to study a particular phenomenon.

>> View Webinar: How-To’s for Data Analysis

Documents fall into three main categories:

- Personal Documents: A personal account of an individual's beliefs, actions, and experiences. The following are examples: e-mails, calendars, scrapbooks, Facebook posts, incident reports, blogs, duty logs, newspapers, and reflections or journals.

- Public Records: Records of an organization's activities that are maintained continuously over time. These include mission statements, student transcripts, annual reports, student handbooks, policy manuals, syllabus, and strategic plans.

- Physical Evidence: Artifacts or items found within a study setting, also referred to as artifacts. Among these are posters, flyers, agendas, training materials, and handbooks.

The qualitative researcher generally makes use of two or more resources, each using a different data source and methodology, to achieve convergence and corroboration. An important purpose of triangulating evidence is to establish credibility through a convergence of evidence. Corroboration of findings across data sets reduces the possibility of bias, by examining data gathered in different ways.

It is important to note that document analysis differs from content analysis as content analysis refers to more than documents. As part of their definition for content analysis, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health states that, “Sources of data could be from interviews, open-ended questions, field research notes, conversations, or literally any occurrence of communicative language (such as books, essays, discussions, newspaper headlines, speeches, media, historical documents).

How Do You Do Document Analysis?

In order for a researcher to obtain reliable results from document analysis, a detailed planning process must be undertaken. The following is an outline of an eight-step planning process that should be employed in all textual analysis including document analysis techniques.

- Identify the texts you want to analyze such as samples, population, participants, and respondents.

- You should consider how texts will be accessed, paying attention to any cultural or linguistic barriers.

- Acknowledge and resolve biases.

- Acquire appropriate research skills.

- Strategize for ensuring credibility.

- Identify the data that is being sought.

- Take into account ethical issues.

- Keep a backup plan handy.

Researchers can use a wide variety of texts as part of their research, but the most common source is likely to be written material. Researchers often ask how many documents they should collect. There is an opinion that a wide selection of documents is preferable, but the issue should probably revolve more around the quality of the document than its quantity.

Why is Document Analysis Useful?

Different types of documents serve different purposes. They provide background information, indicate potential interview questions, serve as a mechanism for monitoring progress and tracking changes within a project, and allow for verification of any claims or progress made.

You can triangulate your claims about the phenomenon being studied using document analysis by using multiple sources and other research gathering methods.

Below are the advantages and disadvantages of document analysis

- Document analysis may assist researchers in determining what questions to ask your interviewees, as well as provide insight into what to watch out for during your participant observation.

- It is particularly useful to researchers who wish to focus on specific case studies

- It is inexpensive and quick in cases where data is easily obtainable.

- Documents provide specific and reliable data, unaffected by researchers' presence unlike with other research methods like participant observation.

Disadvantages

- It is likely that the documents researchers obtain are not complete or written objectively, requiring researchers to adopt a critical approach and not assume their contents are reliable or unbiased.

- There may be a risk of information overload due to the number of documents involved. Researchers often have difficulties determining what parts of each document are relevant to the topic being studied.

- It may be necessary to anonymize documents and compare them with other documents.

How NVivo Can Help with Document Analysis

Analyzing copious amounts of data and information can be a daunting and time-consuming prospect. Luckily, qualitative data analysis tools like NVivo can help!

NVivo’s AI-powered autocoding text analysis tool can help you efficiently analyze data and perform thematic analysis . By automatically detecting, grouping, and tagging noun phrases, you can quickly identify key themes throughout your documents – aiding in your evaluation.

Additionally, once you start coding part of your data, NVivo’s smart coding can take care of the rest for you by using machine learning to match your coding style. After your initial coding, you can run queries and create visualizations to expand on initial findings and gain deeper insights.

These features allow you to conduct data analysis on large amounts of documents – improving the efficiency of this qualitative research method. Learn more about these features in the webinar, NVivo 14: Thematic Analysis Using NVivo.

>> Watch Webinar NVivo 14: Thematic Analysis Using NVivo

Learn More About Document Analysis

Watch Twenty-Five Qualitative Researchers Share How-To's for Data Analysis

Recent Articles

Research Methodologies Guide

- Action Research

- Bibliometrics

- Case Studies

- Content Analysis

- Digital Scholarship This link opens in a new window

- Documentary

- Ethnography

- Focus Groups

- Grounded Theory

- Life Histories/Autobiographies

- Longitudinal

- Participant Observation

- Qualitative Research (General)

- Quasi-Experimental Design

- Usability Studies

Documentary Research

According to Scott & Marshall (2015), Documentary Research is

" Research that uses personal and official documents as a source material. Documents... may include such things as newspapers, diaries, stamps, directories, handbills, maps, government statistical publications, photographs, paintings, gramophone records, tapes, and computer files. "

Documentary research is often conducted by social scientists to assess a set of documents for historical or social value, or to create a larger narrative through the study of multiple documents surrounding an event or individual.

Documentary research is often related to Content Analysis research methodologies.

For more information, browse the selected resources below:

Books and articles

- Documentary Research in the Social Sciences by Malcolm Tight Publication Date: 2019 From diaries and letters to surveys and interview transcripts, documents are a cornerstone of social science research. This book guides you through the documentary research process, from choosing the best research design, through data collection and analysis, to publishing and sharing research findings.

- Documentary Research by Gary McCulloch Publication Date: 2004 Documentary sources have become increasingly neglected in education and the social sciences. This book seeks to emphasise their potential value and importance for an understanding of modern societies, while also recognising their limitations, and explores their relationship with other research strategies.

- An Introduction to Documentary Research A brief introduction to documentary research from the American Educational Research Association.

- Documentary Research [Reference] An encyclopedia entry on Documentary Research from the Encyclopedia of Curriculum Studies.

- << Previous: Digital Scholarship

- Next: Ethnography >>

- Last Updated: Dec 19, 2023 2:12 PM

- URL: https://instr.iastate.libguides.com/researchmethods

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, document analysis as a qualitative research method.

Qualitative Research Journal

ISSN : 1443-9883

Article publication date: 3 August 2009

This article examines the function of documents as a data source in qualitative research and discusses document analysis procedure in the context of actual research experiences. Targeted to research novices, the article takes a nuts‐and‐bolts approach to document analysis. It describes the nature and forms of documents, outlines the advantages and limitations of document analysis, and offers specific examples of the use of documents in the research process. The application of document analysis to a grounded theory study is illustrated.

- Content analysis

- Grounded theory

- Thematic analysis

- Triangulation

Bowen, G.A. (2009), "Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method", Qualitative Research Journal , Vol. 9 No. 2, pp. 27-40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2009, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Documentary Research: Definition, Types, Applications & Examples

Introduction

Over the years, social scientists have used documentary research to understand series of events that have occurred or happened in the past. Here, they explore available recovered or existing documents and material to get information and gain insight into a research question or particular topic.

In this article, we would define the concept of documentary research, the various types of documentary research, its applications, and some valid examples.

Let’s dive right in.

What is Documentary Research?

In simple terms, documentary research is a form of research that uses records to get accurate information about a particular subject. It is a systematic investigation and analysis of existing records or documents. These documents can be in written forms, visual/audio materials, photographs, videos books, etc.

Documentary research is a valuable approach used in exploring historical events, cultural phenomena, and societal trends to get deep insight into a topic, subject or research question.

Documentary research is somewhat similar to content analysis, which also entails studying existing information/documents.

One of the most vital considerations when using documentary research is the quality of the material being utilized, hence the danger of falling into the single-story phenomenon.

To forestall this, the documents being reviewed must be assessed thoroughly before it is used. (see John Scott, A Matter of Record, 1990). The criteria for authenticity involves checking the documents thoroughly to ensure their genuineness.

List of Documentary Research Methods

- Social Research Studies: This form of documentary research is commonly used in social research studies. For instance, Karl Max used documentary research extensively for his research and the documents he used include The Royal Commission, Inland revenue reports, and Her Majesty Inspectors of Factory reports, to mention a few. Emile Durkheim one of the founders of sociology authored a book on suicide and his work was recognized as the first modern example of consistent use of documents for social research.

- Archival Inquiry: This is a field of sociology explored in documentary research. It entails using primary source documents stored in archives. This form of research is popular amongst historians and the archival documents are referred to as references in their research.

- Content Analysis: This method involves the examination and interpretation of content in documents like articles, books, and speeches in other to find a connection, verify events, and identify patterns or trends.

- Historical Analysis: This is the study and analysis of occurrences that took place in the past, but were documented in records like newspapers, government records, and diaries to understand past events accurately and use the information to understand the present.

- Textual Analysis: This form of analysis is focused on printed texts, in a bid to understand pictures, symbols, and language in other to understand events or occurrences that happened in the lives of the subject.

- Oral Tradition : Oral history involves gathering information via oral summations of people who had direct experience of the events or subject being researched. These interviews are recorded and transcribed, and then analyzed as documents.

- Ethnographic Research: This form of research involves documenting the daily experiences of people in their natural environment, in other to understand how interactions in their personal space affect or impacts their experiences.

- Comparative Analysis: Comparative analysis entails comparing documents from multiple sources to understand context, and periods and uncover any similarities or differences. The goal is to understand cultural or political variations.

- Cross-Sectional Analysis: Cross-sectional analysis involves reviewing documents from multiple perspectives to understand changes, trends, or developments over a specific period.

- Aesthetic Interpretation: This is analyzing visual documents, like paintings, photographs, and footage from videos. This is often used as a supplement to text to authenticate discoveries uncovered in text documents.

Understanding the Documentary Research Methodology

Documentary research involves several key steps, such as defining the objective or research question, identifying relevant resources, revising them, and drawing up a well-informed and accurate conclusion based on fact.

Here are some key points to help you understand the documentary research methodology:

- Purpose: The essence of documentary research is to review existing documents to have insight into a research problem or question. The documents reviewed include written texts, such as books, articles, letters, diaries, newspapers, official reports, government publications, and archival materials, and non-written materials like videos, audio recordings, photographs, and digital documents.

- Data Collection: This phase is when researchers gather relevant documents required for the research topic. These documents are evaluated carefully based on credibility and relevance.

Explore – Data Collection Methods: Definition + Steps to Do It

- Data Analysis: Here, the gathered documents are analyzed systematically using relevant document research methodologies. This involves reading, grouping similar resources, and extracting information based on similarities, trends, etc.

- Interpretation: After data analysis, the discoveries are interpreted and the answers are applied to the research question or objective.

Read More: What is Data Interpretation? + [Types, Methods & Tools]

- Ethical Considerations: Ethical principles should be considered when carrying out documentary research. Copyright and intellectual property rights should be respected and all necessary permissions should be obtained before using confidential materials.

- Strengths and Limitations: The documentary research methodology has several advantages. One of which is that it helps researchers study past events by providing relevant documentation that sheds light. It also offers rich and detailed insights into social, cultural, and historical contexts. However, as with every good thing, there are limitations, such as some form of biases in the selected documents, which could emanate from the author or source of the document, missing data, and validity of the findings.

Related: What are Ethical Practices in Market Research?

Applications of Documentary Research

The documentary research methodology has a broad range of applications across various disciplines. They include:

- Historical Research : Documentary research is used extensively in historical studies to explore past events, in other to predict the future. Researchers review historical documents, like letters, diaries, government records, newspapers, and photographs, to better understand historical narratives, social and cultural contexts, and see how individuals or communities conducted their activities in the past.

- Social Sciences: In social sciences, documentary research helps investigate social concepts and trends. Documents like surveys, census data, and organization records are studied and analyzed, in other to understand public opinion, social inequality, and organizational behavior.

- Legal Research: Documentary research plays a vital role in legal studies. Lawyers, legal scholars, policymakers, etc analyze legal documents, regulations, court cases, and legal antecedents all in a bid to understand the legal framework and ways in which law evolves. Documentary research can support legal arguments, influence the development of legal theories, and inform policy-making.

- Education Research: Documentary research is used to understand educational policies, curriculum development, and teaching practices. Researchers review educational documents, such as textbooks, educational policies, and assessment materials, to access educational systems, approaches, and the effect of these on learning outcomes.

Examples of Documentary Research

- The Russian Revolution (1891 – 1924), With the aid of newspaper documents and personal diaries Orlando Figes, a British historian narrated the most important milestones of the revolution in that period and proffered a comprehensive portrait of everyday occurrences as it occurred then the book Figes. depicts how the Russian Revolution was a historical process that changed the lives of its people and had its influence globally.

- The Vietnam War . The 990 minutes audiovisual documentary by Ken Burns narrates the Vietnam War (1955-1975). Throughout 10 episodes, the military operations of the Vietnam War were addressed, as well as the opposition to the war by the US.

- Bios . Lives that marked yours: Luis Alberto Spinetta. This two-hour audiovisual documentary, produced by National Geographic, intimate and deeply details the life of Luis Alberto Spineta, an artist referred to as one of the fathers of Argentine rock. His family was part of the production,the100 hours documentary was directed by Catarina Spinetta and she used recordings, and testimonies from family members to review her father’s childhood until his final moments.

- The Secret Decrees of the Dictatorship . This publication was released between March and May 2019, and more than 7000 secret decrees issued by the Military Juntas in Argentina between 1976-1983 were reviewed by the Data Unit of the news portal. These decrees signed by different dictators focused on deportations, the prohibition of books, and the sale of weapons. All of these materials were analyzed and presented along with eight notes, published in 2019.

- World War II in Photographs, David Boyle . This book is an example of aesthetic documentary research. 900 high-quality photographs from various sources were used to portray World War II (1939–1945). The images uncover the scenarios as the warfare took place. The images were arranged in chronological order with images of the steppes of Russia, the deserts of Africa, the jungles of the South Pacific, and the seas of the Arctic and each one of them has a detailed explanation of the course of events.

- The Silence of the Others . This documentary by the Spanish Pedro Almodóvar took 7 years to produce and over 450 hours of review of materials to uncover the crimes carried out during the Franco regime and the plight of the victims seeking justice.

- The Berlin Wall . The border through a city, Thomas Flemming. This is another example of documentary research, with documents, photos, and illustrations, this book illustrates the history of the Berlin Wall. The daily life of the people who lived to the west and east of the city was portrayed in the book as well as the events that led to the fall of the border in 1989.

Purpose of Documentary Research

The purpose of documentary research is to gather verifiable evidence, that can help researchers understand clearly events that occurred in the past/present and also uncover new knowledge by analyzing existing documents and materials. It aids researchers in exploring topics that are difficult to decipher through other research methods and proffers a historical or contextual perspective on the subject being studied.

When to Use Documentary Research

Documentary research is best when researching events that occurred in the past, especially in instances where direct observation is not applicable. Here are some instances where documentary research is particularly useful:

- Historical Studies: Documentary research is ideal when conducting historical research. Researchers can then analyze historical records or documents left behind to better understand past events, chronologically.

- Exploratory Research: In cases where there are gaps in research studies. documentary research can serve as an exploratory method to fill gaps in knowledge by exploring different perspectives that can uncover new knowledge.

- Policy Analysis : Documentary research is useful in examining policies and similar regulations. By analyzing policy documents, over a period, researchers can measure the impact policies had or have on a particular subject. Based on their review of existing documents, they can make recommendations and supervise their implementation. This method is particularly useful in fields such as public policy, education, healthcare, and social welfare.

- Comparative Studies: Documentary research is useful for comparative analysis. Researchers can analyze documents from different sources and geographical locations to identify patterns, verify results or simply identify contradictions and uncover areas that require further investigation.

Characteristics of Documentary Research

- Uses Existing Documents: Documentary research is based on existing documents as a primary source of data. These documents can be written(letters, diaries, articles, books)or unwritten documents(videos, photographs, inscriptions). These documents are analyzed to gain insight and understanding into a specific phenomenon.

- Non-Experimental In Nature: Documentary research does not involve manipulated variables, meaning that the researcher can not change the outcomes by directly intervening in the research. All the results derived are based on phenomena that have d occurred, which have documented records to attest to their occurrence.

- Data Analysis: Documentary research involves rigorous data analysis, as researchers have to carefully read, extract relevant information, categorize data, and use qualitative/quantitative analysis to derive results.

- Interpretation of Findings: After data analysis. The findings of the research must be interpreted in a way that gives insight and deep understanding to anyone reading about the subject being researched. The interpretation phase involves synthesizing and relating the findings to the research questions or objectives.

- Contextual Understanding : Documentary research emphasizes the importance of understanding the social, cultural, and historical, events in the context, in which the documents were recorded, reviewed, and analyzed.By context we mean, the period, cultural norms, political climate, socio-economic factors, etc where the events being studied took place and under what circumstances. This contextual understanding helps to interpret the findings and draw accurate conclusions.

- Cross Reference and Validation: Documentary research is characterized by cross-referencing or triangulation, which involves using multiple sources or methods to corroborate findings. The combination of documentary research with other research methods strengthens the validity and reliability of their findings. This enhances the robustness of the research and helps minimize potential biases or inaccuracies.

- Ethical Considerations: Documentary research requires that researchers respect ethical guidelines and principles. Copyright and intellectual property laws must be adhered to and necessary permissions obtained when using sensitive or confidential documents, as well as the privacy and anonymity of individuals mentioned in the documents.

Advantages of Documentary Research

- Access to Existing Data: In documentary research, existing data is readily available for review and analysis. There is no need to collect new data, via surveys and the like which can take time or require intensive resources. This makes documentary research a cost-effective and efficient method.

- Rich and Dynamic Data: Documents and materials used in documentary research offer a rich pool of information and insights. This method covers a wide range of topics, periods, and perspectives. There is access to primary sources, such as original letters or historical documents, as well as secondary sources like scholarly articles or reports. This variety of data allows for a comprehensive and clear understanding of the research topic.

- Longitudinal and Historical Perspectives: Documentary research allows researchers to study phenomena over extended periods and explore historical contexts. By examining documents spanning different periods, researchers can analyze patterns, trends, changes, and continuity across social, cultural, or organizational aspects.

- Non-Intrusive Method : Since documentary research relies on existing documents, there is no direct involvement with research subjects or settings. Hence there is no need to disturb or manipulate the research environment or intrude on the lives of individuals. This makes it an ethical and practical method, especially for sensitive or personal topics.

- Exploration of Inaccessible or Historical Data: Documentary research allows researchers to access data that cannot be duplicated anymore due to timelapse and changing circumstances. For instance, researchers can analyze archived documents, historical records, or rare texts which provide unique insights into the past or specific contexts.