Creating and Scoring Essay Tests

FatCamera / Getty Images

- Tips & Strategies

- An Introduction to Teaching

- Policies & Discipline

- Community Involvement

- School Administration

- Technology in the Classroom

- Teaching Adult Learners

- Issues In Education

- Teaching Resources

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Special Education

- Homeschooling

- M.Ed., Curriculum and Instruction, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

Essay tests are useful for teachers when they want students to select, organize, analyze, synthesize, and/or evaluate information. In other words, they rely on the upper levels of Bloom's Taxonomy . There are two types of essay questions: restricted and extended response.

- Restricted Response - These essay questions limit what the student will discuss in the essay based on the wording of the question. For example, "State the main differences between John Adams' and Thomas Jefferson's beliefs about federalism," is a restricted response. What the student is to write about has been expressed to them within the question.

- Extended Response - These allow students to select what they wish to include in order to answer the question. For example, "In Of Mice and Men , was George's killing of Lennie justified? Explain your answer." The student is given the overall topic, but they are free to use their own judgment and integrate outside information to help support their opinion.

Student Skills Required for Essay Tests

Before expecting students to perform well on either type of essay question, we must make sure that they have the required skills to excel. Following are four skills that students should have learned and practiced before taking essay exams:

- The ability to select appropriate material from the information learned in order to best answer the question.

- The ability to organize that material in an effective manner.

- The ability to show how ideas relate and interact in a specific context.

- The ability to write effectively in both sentences and paragraphs.

Constructing an Effective Essay Question

Following are a few tips to help in the construction of effective essay questions:

- Begin with the lesson objectives in mind. Make sure to know what you wish the student to show by answering the essay question.

- Decide if your goal requires a restricted or extended response. In general, if you wish to see if the student can synthesize and organize the information that they learned, then restricted response is the way to go. However, if you wish them to judge or evaluate something using the information taught during class, then you will want to use the extended response.

- If you are including more than one essay, be cognizant of time constraints. You do not want to punish students because they ran out of time on the test.

- Write the question in a novel or interesting manner to help motivate the student.

- State the number of points that the essay is worth. You can also provide them with a time guideline to help them as they work through the exam.

- If your essay item is part of a larger objective test, make sure that it is the last item on the exam.

Scoring the Essay Item

One of the downfalls of essay tests is that they lack in reliability. Even when teachers grade essays with a well-constructed rubric, subjective decisions are made. Therefore, it is important to try and be as reliable as possible when scoring your essay items. Here are a few tips to help improve reliability in grading:

- Determine whether you will use a holistic or analytic scoring system before you write your rubric . With the holistic grading system, you evaluate the answer as a whole, rating papers against each other. With the analytic system, you list specific pieces of information and award points for their inclusion.

- Prepare the essay rubric in advance. Determine what you are looking for and how many points you will be assigning for each aspect of the question.

- Avoid looking at names. Some teachers have students put numbers on their essays to try and help with this.

- Score one item at a time. This helps ensure that you use the same thinking and standards for all students.

- Avoid interruptions when scoring a specific question. Again, consistency will be increased if you grade the same item on all the papers in one sitting.

- If an important decision like an award or scholarship is based on the score for the essay, obtain two or more independent readers.

- Beware of negative influences that can affect essay scoring. These include handwriting and writing style bias, the length of the response, and the inclusion of irrelevant material.

- Review papers that are on the borderline a second time before assigning a final grade.

- Utilizing Extended Response Items to Enhance Student Learning

- Study for an Essay Test

- How to Create a Rubric in 6 Steps

- Top 10 Tips for Passing the AP US History Exam

- UC Personal Statement Prompt #1

- Tips to Create Effective Matching Questions for Assessments

- Self Assessment and Writing a Graduate Admissions Essay

- 10 Common Test Mistakes

- ACT Format: What to Expect on the Exam

- The Computer-Based GED Test

- GMAT Exam Structure, Timing, and Scoring

- Tips to Cut Writing Assignment Grading Time

- 5 Tips for a College Admissions Essay on an Important Issue

- Ideal College Application Essay Length

- SAT Sections, Sample Questions and Strategies

- What You Need to Know About the Executive Assessment

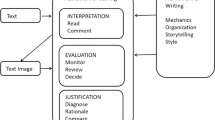

TOPICS A. Fill-in-the-Blank Items B. Essay Questions C. Scoring Options

Assignments

Extended Response

Extended responses can be much longer and complex then short responses, but students should be encouraged to remain focused and organized. On the FCAT, students have 14 lines for each answer to an extended response item, and they are advised to allow approximately 10-15 minutes to complete each item. The FCAT extended responses are scored using a 4-point scoring rubric. A complete and correct answer is worth 4 points. A partial answer is worth 1, 2, or 3 points.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Am J Pharm Educ

- v.83(7); 2019 Sep

Best Practices Related to Examination Item Construction and Post-hoc Review

Michael j. rudolph.

a University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky

Kimberly K. Daugherty

b Sullivan University College of Pharmacy, Louisville, Kentucky

Mary Elizabeth Ray

c The University of Iowa College of Pharmacy, Iowa City, Iowa

Veronica P. Shuford

d Virginia Commonwealth University School of Pharmacy, Richmond, Virginia

Lisa Lebovitz

e University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Baltimore, Maryland

Margarita V. DiVall

f Northeastern University School of Pharmacy, Boston, Massachusetts

g Editorial Board Member, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education , Arlington, Virginia

Objective. To provide a practical guide to examination item writing, item statistics, and score adjustment for use by pharmacy and other health professions educators.

Findings. Each examination item type possesses advantages and disadvantages. Whereas selected response items allow for efficient assessment of student recall and understanding of content, constructed response items appear better suited for assessment of higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. Although clear criteria have not been established, accepted ranges for item statistics and examination reliability have been identified. Existing literature provides guidance on when instructors should consider revising or removing items from future examinations based on item statistics and review, but limited information is available on performing score adjustments.

Summary. Instructors should select item types that align with the intended learning objectives to be measured on the examination. Ideally, an examination will consist of multiple item types to capitalize on the advantages and limit the effects of any disadvantages associated with a specific item format. Score adjustments should be performed judiciously and by considering all available item information. Colleges and schools should consider developing item writing and score adjustment guidelines to promote consistency.

INTRODUCTION

The primary goal of assessment via examination is to accurately measure student achievement of desired knowledge and competencies, which are generally articulated through learning objectives. 1,2 For students, locally developed examinations convey educational concepts and topics deemed important by faculty members, which allows students to interact with those concepts and receive feedback on the extent to which they have mastered the material. 3,4 For faculty members, results provide valuable insight into how students are thinking about concepts, assist with identifying student misconceptions, and often serve as the basis for assigning course grades. Furthermore, examinations allow faculty members to evaluate student achievement of learning objectives to make informed decisions regarding the future use and revision of instructional modalities. 5,6

Written examinations may be effective assessment tools if designed to measure student achievement of the desired competencies in an effective manner. Quality items (questions) are necessary for an examination to have reliability and to draw valid conclusions from the resulting scores. 7,8 Broadly defined, reliability refers to the extent to which an examination or another assessment leads to consistent and reproducible results, and validity pertains to whether the examination score provides an accurate measure of student achievement for the intended construct (eg, knowledge or skill domain). 9,10 However, development of quality examination items, notably multiple choice, can be challenging; existing evidence suggests that a sizeable proportion of items within course-based examinations contain one or more flaws. 7,11 While there are numerous published resources regarding examination and item development, most appear to be aimed towards those with considerable expertise or significant interest in the subject, such as scholars in educational psychology or related disciplines. 2,8-11 Our goal in authoring this manuscript was to provide an accessible primer on test item development for pharmacy and other health professions faculty members. As such, this commentary discusses published best practices and guidelines for test item development, including different item types and the advantages and disadvantages of each, item analysis for item improvement, and best practices for examination score adjustments. A thorough discussion of overarching concepts and principles related to examination content development, administration, and student feedback is contained in the companion commentary article, “Best Practices on Examination Construction, Administration, and Feedback.” 12

General Considerations Before Writing Examination Items

Planning is essential to the development of a well-designed examination. Before writing examination items, faculty members should first consider the purpose of the examination (eg, formative or summative assessment) and the learning objectives to be assessed. One systematic approach is the creation of a detailed blueprint that outlines the desired content and skills to be assessed as well as the representation and intended level(s) of student cognition for each. 12 This will help to determine not only the content and number of items but also the types of items that will be most appropriate. 13,14 Moreover, it is important to consider the level of student experience with desired item formats, as this can impact performance. 15 Students should be able to demonstrate what they have learned, and performance should not be predicated upon their ability to understand how to complete each item. 16 A student should be given formative opportunities to gain practice and experience with various item formats before encountering them on summative examinations, This will enable students to self-identify any test-taking deficiencies and could help to reduce test anxiety. 17 Table 1 contains several recommendations for writing quality items and avoiding technical flaws.

Guidelines That Reflect Best Practices for Writing Quality Test Items 21-24

One of the most important principles when writing examination items is to focus on essential concepts. Examination items should assess the learning objectives and overarching concepts of the lesson, and test in a manner that is in accordance with how students will ultimately use the information. 18 Avoid testing on, or adding, trivial information to items such as dates or prevalence statistics, which can cause construct-irrelevant variance in the examination scores (discussed later in this manuscript). Similarly, because students carefully read and analyze examination items, superfluous information diverts time and attention from thoughtful analysis and can cause frustration when students discover they could have answered the item without reading the additional content. 4,5,19 A clear exception to this prohibition on extraneous information relates to items that are intended to assess the student’s ability to parse out relevant data in order to provide or select the correct answer, as is done frequently with patient care scenarios. However, faculty members should be cognizant of the amount of time it takes for students to read and answer complex problems and keep the overall amount of information on an examination manageable for reading, analysis, and completion.

Each item should test a single construct so that the knowledge or skill deficiency is identifiable if a student answers an item incorrectly. Additionally, each item should focus on an independent topic and multiple items should not be “hinged” together. 4 Hinged items are interdependent, such that student performance on the entire item set is linked to accuracy on each one. This may occur with a patient care scenario that reflects a real-life situation such as performing a series of dosing calculations. However, this approach does not assess whether an initial mistake and subsequent errors resulted from a true lack of understanding of each step or occurred simply because a single mistake was propagated throughout the remaining steps. A more effective way to assess this multi-step process would be to have them work through all steps and provide a final answer (with or without showing their work) as part of a single question, or to present them with independent items that assess each step separately.

Examination Item Types

There is a variety of item types developed for use within a written examination, generally classified as selected response format, where students are provided a list of possible answers, and constructed response format that require students to supply the answer. 4,19 Common selected-response formats include multiple choice (true/false, single best answer, multiple answer, and K-type), matching, and hot spots. Constructed response formats consist of fill-in-the-blank, short answer, and essay/open response. Each format assesses knowledge or skills in a unique way and has distinct advantages and disadvantages, which are summarized in Table 2 . 20,21

Advantages and Disadvantages of Examination Question Types 10,11,20,21,43

The most commonly used item format for written examinations is the multiple-choice question (MCQ), which includes true-false (alternative-choice), one-best answer (ie, standard MCQ), and multiple correct answer items (eg, select all that apply, K-type). 4,19 True-false items ask the examinee to make a judgment about a statement, and are typically used to assess recall and comprehension. 4 Each answer choice must be completely true or false and should only test one dimension, which can be deceptively challenging to write. Flawed true-false items can leave an examinee guessing at what the item writer intended to ask. Faculty members should not be tempted to use true-false extensively as a means of increasing the number of examination items to cover more content or to limit the time needed for examination development. Although an examinee can answer true-false items quickly and scoring is straightforward, there is a 50% chance that an examinee can simply guess the correct answer, which leads to low item reliability and overall examination reliability. Not surprisingly, true-false questions are the most commonly discarded type of item after review of item statistics for standardized examinations. 4 Though it may take additional time to grade, a way to employ true-false items that requires higher-order thinking is to have the examinee identify, fix, or explain any statements deemed “false” as part of the question. 22

One-best-answer items (traditional MCQ) are the most versatile of all test item types as they can assess the test taker’s application, integration, and synthesis of knowledge as well as judgment. 23 In terms of design, these items contain a stem and a lead-in followed by a series of answer choices, only one of which is correct and the other incorrect options serve as distractors. Sound assessment practice for one-best-answer MCQs include: using a focused lead-in, making sure all choices relate to one construct, and avoiding vague terms. A simple means of determining whether a lead-in is focused is to use the “cover-the-options” rule: the examinee should be able to read the stem and lead-in, cover the options, and be able to supply the correct answer without seeing the answer choices. 4 The stem should typically be in the form of a positive or affirmative question or statement, as opposed to a negative one (eg, one that uses a word like “not,” “false,” or “except”). However, negative items may be appropriate in certain situations, such as when assessing whether the examinee knows what not to do (eg, what treatment is contraindicated). If used, a negative word should be emphasized using one or more of the following: italics, all capital letters, underlining, or boldface type.

In addition to the stem and correct answer, careful consideration should also be paid to writing MCQ distractors. Distractors should be grammatically consistent with the stem, similar in length, and plausible, and should not overlap. 24 Use of “all of the above” and “none of the above” should be avoided as these options decrease the reliability of the item. 25 As few as two distractors are sufficient, but it is common to use three to four. Determining the appropriate number of distractors depends largely on the number of plausible choices that can be written. In fact, evidence suggests that using four or more options rather than three does not improve item performance. 26 Additionally, a desirable trait of any distractor is that it should appeal to low-scoring students more than to high-scoring students because the goal of the examination is to differentiate students according to their level of achievement (or preparation) and not their test-taking abilities. 27

Multiple-answer, multiple-response, or “select all that apply” items are composed of groups of true-false statements nested under a single stem and require the test-taker to make a judgment on each answer choice, and may be graded using partial credit or an “all or nothing” requirement. 4 A similar approach, known as K-type, provides the individual answer choices in addition to various combinations (eg, A and B; A and D; B, C, and E). Notably, K-type items tend to have lower reliability than “select all that apply” items because of the greater likelihood that an examinee can guess the correct answer through a process of elimination; therefore, use of K-type items is generally not recommended. 4,24 Should a faculty member decide to use K-type items, we recommend that they include at least one correct answer and one incorrect answer. Otherwise, examinees are apt to believe it is a “trick” question, as they may find it unlikely that all choices are either correct or incorrect. Faculty members should also be careful not to hinge the answer choices within a multiple-answer item; the examinee should be required to evaluate each choice independently.

Matching and hot-spot items are two additional forms of selected-response items, and although they are used less frequently, their complexity may offer a convenient way to assess an examinee’s grasp of key concepts. 28 Matching items can assess knowledge and some comprehension if constructed appropriately. In these items, the stem is in one column and the correct response is in a second column. Responses may be used once or multiple times depending on item design. One advantage to matching items is that a large amount of knowledge may be assessed in a minimum amount of space. Moreover, instructor preparation time is lower compared to the other item types presented above. These aspects may be particularly important when the desired content coverage is substantial, or the material contains many facts that students must commit to memory. Brevity and simplicity are best practices when writing matching items. Each item stem should be short, and the list of items should be brief (ie, no more than 10-15 items). Matching items should also contain items that share the same foundation or context and are arranged in a systematic order, and clear directions should be provided as to whether answers are to be used more than once.

Hot spot items are technology-enhanced versions of multiple-choice items. These items allow students to click areas on an image (eg, identify an anatomical structure or a component of a complex process) and select one or more answers. The advantages and disadvantages of hot spots are similar to those of multiple-choice items; however, there are minimal data currently available to guide best practices for hot spot item development. Additionally, they are only available through certain types of testing platforms, which means not all faculty members may have access to this technology-assisted item type. 29

Some educators suggest that performance on MCQs and other types of selected response items is artificially inflated as examinees may rely on recognition of the information provided by the answer choices. 11,30 Constructed-response items such as fill-in-the-blank (or completion), short answer, and essay may provide a more accurate assessment of knowledge because the examinee must construct or synthesize their own answers rather than selecting them from a list. 5 Fill-in-the-blank (FIB) items differ from short answer and essay items in that they typically require only one- or two-word responses. These items may be more effective to minimize guessing compared to selected response items. However, compared to short answer and essay items, developing FIB items that assess higher levels of learning can be challenging because of the limited number of words needed to answer the item. 28 Fill-in-the-blank items may require some degree of manual grading as accounting for the exact answers students provide or for such nuances as capitalization, spacing, spelling, or decimal places may be difficult when using automated grading tools.

Short-answer items have the potential to effectively assess a combination of correct and incorrect ideas of a concept and measure a student’s ability to solve problems, apply principles, and synthesize information. 10 Short-answer items are also straightforward to write and can reduce student cheating because they are more difficult for other students to view and copy. 31 However, results from short-answer items may have limited validity as the examinee may not provide enough information to allow the instructor to fully discern the extent to which the student knows or comprehends the information. 4,5 For example, a student may misinterpret the prompt and only provide an answer that tangentially relates to the concept tested, or because of a lack of confidence, a student may not write about an area he or she is uncertain about. 5 Grading must be accomplished manually in most cases, which can often be a deterrent to using this item type, and may also be inconsistent from rater to rater without a detailed key or rubric. 10,28

Essay response items provide the opportunity for faculty members to assess and students to demonstrate greater knowledge and comprehension of course material beyond that of other item formats. 10 There are two primary types of essay item formats: extended response and restricted response. Extended response items allow the examinee complete freedom to construct their answer, which may be useful for testing at the synthesis and evaluation levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. Restricted response provides parameters or guides for the response, which allows for more consistent scoring. Essay items are also relatively easy for faculty members to develop and often necessitate that students demonstrate critical thinking as well as originality. Disadvantages include being able to assess only a limited amount of material because of the time needed for examinees to complete the essay, decreased validity of examination score interpretations if essay items are used exclusively, and substantial time required to score the essays. Moreover, as with short answer, there is the potential for a high degree of subjectivity and inconsistency in scoring. 9,11

Important best practices in constructing an essay item are to state a defined task for the examinee in the instructions, such as to compare ideas, and to limit the length of the response. The latter is especially important on an examination with multiple essay items intended to assess a wide array of concepts. Another recommendation is for faculty members to have a clear idea of the specific abilities they wish for students to demonstrate before writing an item. A final recommendation is for faculty members to develop a prompt that creates “novelty” for students so that they must apply knowledge to a new situation. 10 One of two methods is usually employed in evaluating essay responses: an analytic scoring model, where the instructor prepares an ideal answer with the major components identified and points assigned, or a holistic approach in which the instructor reads a student’s entire essay and grades it relative to other students’ responses. 28,30 Analytic scoring is the preferred method because it can reduce subjectivity and thereby lead to greater score reliability.

Literature on Item Types and Student Outcomes

There are limited data in the literature comparing student outcomes by item type or number of distractors. Hubbard and colleagues conducted a cross-over study to identify differences in multiple true-false and free-response examination items. 5 The study found that while correct response rates correlated across the two formats, a higher percentage of students provided correct responses to the multiple true-false items than to the free response questions. Results also indicated that a higher prevalence of students exhibited mixed (correct and incorrect) conceptions on the multiple true-false items vs the free-response items, whereas a higher prevalence of students had partial (correct and unclear) conceptions on free-response items. This study suggests that multiple-true-false responses may direct students to specific concepts but obscure their critical thinking. Conversely, free-response items may provide more critical-thinking assessment while at the same time offering limited information on incorrect conceptions. The limitations of both item types may be overcome by alternating between the two within the same examination. 5

In 1999, Martinez suggested that multiple-choice and constructed-response (free-response items) differed in cognitive demand as well as in the range of cognitive levels they were able to elicit. 32 Martinez notes the inherent difficulty in comparing the two item types because of the fact that each may come in a variety of forms and cover a range of different cognitive levels. Nonetheless, he was able to identify several consistent patterns throughout the literature. First, both types may be used to assess information recall, understanding, evaluating, and problem solving, but constructed response are better suited to assess at the level of synthesis. Second, although they may be used to assess at higher levels, most multiple-choice items tend to assess knowledge and understanding in part because of the expertise involved in writing valid multiple-choice items at higher levels. Third, both types of items are sensitive to examinees’ personal characteristics that are unrelated to the topic being assessed, and these characteristics can lead to unwanted variance in scores. One such characteristic that tends to present issues for multiple-choice items more so than for constructed-response items is known as “testwiseness,” or the skill of choosing the right answers without having greater knowledge of the material than another, comparable student. Another student characteristic that affects student performance is test anxiety, which is often of greater concern when crafting constructed-response items than multiple-choice items. Finally, Martinez concludes that student learning is affected by the types of items used on examinations. In other words, students study and learn material differently depending on whether the examination will be predominantly multiple-choice items, constructed response, or a combination of the two.

In summary, the number of empirical studies looking at the properties, such as reliability or level of cognition, and student outcomes on written examinations based upon use of one item type compared to another is currently limited. The few available studies and existing theory suggest the use of different item types to assess distinct levels of student cognition. In addition to the consideration of intended level(s) of cognition to be assessed, each item type has distinct advantages and disadvantages regarding the amount of faculty preparation and grading time involved, expertise required to write quality items, reliability and validity, and student time required to answer. Consequently, a mixed approach that makes use of multiple types of items may be most appropriate for many course-based examinations. Faculty members could, for example, include a series of multiple-choice items, several fill-in-the-blank and short answer items, and perhaps several essay items. In this way, the instructor can take advantage of each item type while avoiding one or a few perpetual disadvantages associated with a type.

Technical Flaws in Item Writing

There are common technical flaws that may occur when examination items of any type do not follow published best practices and guidelines such as those shown in Table 1 . Item flaws introduce systematic errors that reduce validity and can negatively impact the performance of some test takers more so than others. 7 There are two categories of technical flaws: irrelevant difficulty and “test-wiseness.” 4 Irrelevant difficulty occurs when there is an artificial increase in the difficulty of an item because of flaws such as options that are too long or complicated, numeric data that are not presented consistently, use of “none of the above” as an option, and stems that are unnecessarily complicated or negatively phrased. 2 , 12 These and other flaws can add construct-irrelevant variance to the final test scores because the item is challenging for reasons unrelated to the intended construct (knowledge, skills, or abilities) to be measured. 33 Certain groups of students, for example, those who speak English as a second language or have lower reading comprehension ability, may be particularly impacted by technical flaws, leading to irrelevant difficulty. This “contaminating influence” serves to undermine the validity of interpretations drawn from examination scores.

Test-wise examinees are more perceptive and confident in their test-taking abilities compared to other examinees and are able to identify cues in the item or answer choices that “give away” the answer. 4 Such flaws reward superior test-taking skills rather than knowledge of the material. Test-wise flaws include the presence of grammatical cues (eg, distractors having different grammar than the stem), grouped options, absolute terms, correct options that are longer than others, word repetition between the stem and options, and convergence (eg, correct answer includes the most elements in common with the other options). 4 Because of the potential for these and other flaws, the authors strongly encourage faculty members review Table 1 or the list of item-writing recommendations developed by Haladyna and colleagues when preparing examination items. 24 Faculty members should consider asking a colleague to review their items prior to administering the examination as an additional means of identifying and correcting flaws and providing some assurance of content-related validity, which aims to determine whether the test content covers a representative sample of the knowledge or behavior to be assessed. 34 For standardized or high-stakes examinations, a much more rigorous process of gathering multiple types of validity evidence should be undertaken; however, this is neither required nor practical for the majority of course-based examinations. 15 Conducting an item analysis after students have completed the examination is important as this may identify flaws that may not have been clear at the time the examination was developed.

Overview of Item Analysis

An important opportunity for faculty learning, improvement, and self-assessment is a thorough post-examination review in which an item analysis is conducted. Electronic testing platforms that present item and examination statistics are widely available, and faculty members should have a general understanding of how to interpret and appropriately use this information. 35 Item analysis is a powerful tool that, if misunderstood, can lead to inappropriate adjustments following delivery and initial scoring of the examination. Unnecessarily removing or score-adjusting items on an examination may produce a range of undesirable issues including poor content representation, student entitlement, grade inflation, and failure to hold students accountable for learning challenging material.

One of the most widely used and simplest item statistics is the item difficulty index ( p ), which is expressed as the percent of students who correctly answered the item. 10 For example, if 80% of students answered an item correctly, p would be 0.80. Theoretically, p can range from 0 (if all students answered the item incorrectly) to 1 (if all students answered correctly). However, Haladyna and Downing note that because of students guessing, the practical lower bound of p is 0.25 rather than zero for a four-option item, 0.33 for a three-option item, and so forth. 27 Item difficulty and overall examination difficulty should reflect the purpose of the assessment. A competency-based examination, or one designed to ensure that students have a basic understanding of specific content, should contain items that most students answer correctly (high p value). For course-based examinations, where the purpose is usually to differentiate between students at various levels of achievement, the items should range in difficulty so that a large distribution of student total scores is attained. In other words, little information is obtained about student comprehension of the content if most items were extremely difficult (eg, p <.30) or easy (eg, p >.90). For quality improvement, it is just as important to evaluate items that nearly every student answers correctly as those with a low p. In reviewing p values, one should also consider the expectations for the intended outcome of each item and topic, which can be anticipated through use of careful planning and examination blueprinting as noted earlier. For example, some key concepts that the instructor emphasizes many times or that require simple recall may lead to most students answering correctly (high p ), which may be acceptable or even desirable.

A second common measure of item performance is the item discrimination index ( d ), which measures how well an item differentiates between low- and high-performing students. 36 There are several different methods that can be used to calculate d , although it has been shown that most produce comparable results. 34 One approach for calculating d when scoring is dichotomous (correct or incorrect) is to subtract the percentage of low-performing students who answered a given item correctly from the percentage of high-performing students who answered correctly. Accordingly, d ranges from -1 to +1, where a value of +1 represents the extreme case of all high-scorers answering the item correctly and all low-scorers incorrectly, and -1 represents the case of all high-scorers answering incorrectly and low-scorers correctly.

How students are identified as either “high performing” or “low performing” is somewhat arbitrary, but the most widely used cutoff is the top 27% and bottom 27% of students based upon total examination score. This practice stems from the need to identify extreme groups while having a sufficient number of cases in each group. The 27% represents the location on the normal curve where these two criteria are approximately balanced. 34 However, for very small class sizes (about 50 or fewer), defining the upper and lower groups using the 27% rule may still lead to unreliable estimates for item discrimination. 38 One option for addressing this issue is to increase the size of the high- and low-scoring groups to the upper and lower 33%. In practice, this may not be feasible as faculty members may be limited by the automated output of an examination platform, and we suspect most faculty members will not have the time to routinely perform such calculations by hand or using another platform. Alternatively, one can calculate (or refer to the examination output if available) a phi (ϕ) or point biserial (PBS) correlation coefficient between each student’s response on an item and overall performance on the examination. 34 Regardless of which of these calculation methods is used, the interpretation of d is the same. For all items on a commercial, standardized examination, p should be at least 0.30; however, for course-based assessments it should at least exceed 0.15. 36,37 A summary of the definitions and use of different item statistics, including difficulty and discrimination, as well as exam reliability measures is found in Table 3 .

Definitions of Item Statistics and Examination Reliability Measures to be Used to Ensure Best Practices in Examination Item Construction 18-25,41

Another key factor used in diagnosing item performance, specifically on multiple-choice items, is the number of students who selected each possible answer. Answer choices that few or no students selected do not add value and need revision or removal from future iterations of the examination. 38 Additionally, an incorrect answer choice that was selected as often as (or more often than) the correct answer could indicate an issue with item wording, the potential of more than one correct answer choice, or even miscoding of the correct answer choice.

Examination Reliability

Implications for the quality of each individual examination item extend beyond whether it provides a valid measure of student achievement for a given content area. Collectively, the quality of items affects the reliability and validity of the overall examination scores. For this reason and the fact that many existing electronic testing platforms provide examination reliability statistics, the authors have identified that a brief discussion of this topic is warranted. There are several classic approaches in the literature for estimating the reliability of an examination, including test-retest, parallel forms, and subdivided test. 37 Within courses, the first two are rarely used as they require multiple administrations of the same examination to the same individuals. Instead, one or multiple variants of subdivided test reliability are used, most notably split-half, Kuder-Richardson, or Cronbach alpha. As the name implies, split-half reliability involves the division of examination items into equivalent halves and calculating the correlation of student scores between the two parts. 38 The purpose is to provide an estimate of the accuracy with which an examinee’s knowledge, skills, or traits are measured by the test. Several formulas exist for split-half, but the most common involves the calculation of a Pearson bivariate correlation (r). 37 Several limitations exist for split-half reliability, notably the use of a single instrument and administration as well as sensitivity to speed (timed examinations), both of which can lead to inflated reliability estimates.

The Kuder-Richardson formula, or KR20, was developed as a measure of internal consistency of the items on a scale or examination. It is an appropriate measure of reliability when item answers are dichotomous and the examination content is homogenous. 38 When examination items are ordinal or continuous, Cronbach alpha should be used instead. The KR20 and alpha can range from 0 to 1, with 0 representing no internal consistency and values approaching 1 indicating a high degree of reliability. In general, a KR20 or alpha of at least 0.50 is desired, and most course-based examinations should range between 0.60 and 0.80. 39,40 The KR20 and alpha are both dependent upon the total number of items, standard deviation of total examination scores, and the discrimination of items. 9 The dependence of these reliability coefficients on multiple factors suggests there is not a set minimum number of items needed to achieve the desired reliability. However, the inclusion of additional items that are similar in quality and content to existing items on an examination will generally improve examination reliability.

As noted above, KR20 and alpha are sensitive to examination homogeneity, meaning the extent to which the examination is measuring the same trait throughout. An examination that contains somewhat disparate disciplines or content may produce a low KR20 coefficient despite having a sufficient number of well-discriminating items. For example, an examination containing 10 items each for biochemistry, pharmacy ethics, and patient assessment may exhibit poor internal consistency because a student’s ability to perform at a high level in one of these areas is not necessarily correlated with the student’s ability to perform well in the other two. One solution to this issue is to divide such an examination into multiple, single-trait assessments, or simply calculate the KR20 separately for items measuring each trait. 36 Because of the limitations of KR20 and other subdivided measures of reliability, these coefficients should be interpreted in context and in conjunction with item analysis information as a means of improving future administrations of an examination.

Another means of examining the reliability of an examination is using the standard error of measurement (SEM) of the scores it produces. 34 From classical test theory, it is understood that no assessment can perfectly measure the desired construct or trait in an individual because of various sources of measurement error. Conceptually, if the same assessment were to be administered to the same student 100 times, for example, numerous different scores would be obtained. 41 The mean of these 100 scores is assumed to represent the student’s true score , and the standard deviation of the assessment scores would be mathematically equivalent to the standard error. Thus, a lower SEM is desirable (0.0 is the ideal standard) as it leads to greater confidence in the precision of the measured or observed score.

In practice, the SEM is calculated for each individual student’s score using the standard deviation of test scores and the reliability coefficient, such as the KR20 or Cronbach alpha. Assuming the distribution of test scores is approximately normal, there is a 68% probability that a student’s true score is within ±1 SEM of the observed score, and a 95% probability that it is within ±2 SEM of the observed score. 9 For example, if a student has a measured score of 80 on an examination and the SEM is 5, there is a 95% probability that the student’s true score is between 70 and 90. Although SEM provides a useful measure of the precision of the scores an examination produces, a reliability coefficient (eg, KR20) should be used for the purpose of comparing one test to another. 10

Post-examination Item Review and Score Adjustment

Faculty members should review the item statistics and examination reliability information as soon as it is available and, ideally, prior to releasing scores to students. Review of this information may serve to both identify flawed items that warrant immediate attention, including any that have been miskeyed, and those that should be refined or removed prior to future administrations of the same examination. When interpreting p and d , the instructor should follow published guidelines but avoid setting any hard “cutoff” values to remove or score-adjust items. 39 Another important consideration in the interpretation of item statistics is the length of the examination. For an assessment with a small number of items, the item statistics should not be used because students’ total examination scores will not be very reliable. 42 Moreover, interpretation and use of item statistics should be performed judiciously, considering all available information before making changes. For example, an item with a difficulty of p =.3, which indicates only 30% of students answered correctly, may appear to be a strong candidate for removal or adjustment. This may be the case if it also discriminated poorly (eg, if d =-0.3). In this case, few students answered the item correctly and low scorers were more likely than high scorers to do so, which suggests a potential flaw with the item. It could indicate incorrect coding of answer choices or that the item was confusing to students and those who answered correctly did so by guessing. Alternatively, if this same item had a d = 0.5, the instructor might not remove or adjust the item because it differentiated well between high- and low-scorers, and the low p may simply indicate that many students found the item or content challenging or that less instruction was provided for that topic. Item difficulty and discrimination ranges are provided in Table 4 along with their interpretation and general guidelines for item removal or revision.

Recommended Interpretations and Actions Using Item Difficulty and Discrimination Indices to Ensure Best Practices in Examination Item Construction 36

In general, instructors should routinely review all items with a p <.5-.6. 38,43 In cases where the answer choices have been miscoded (eg, one or more correct responses coded as incorrect), the instructor should simply recode the answer key to award credit appropriately. Such coding errors can generally be identified through examination of both the item statistics and frequency of student responses for each answer option. Again, this type of adjustment does not present any ethical dilemmas if performed before students’ scores are released. In other cases, score adjustment may appear less straightforward and the instructor has several options available ( Table 4 ). A poorly performing item, identified as one having both a low p (<.60) and d (<.15), is a possible candidate for removal because the item statistics suggest those students who answered correctly most likely did so by guessing. 38 This approach, however, has drawbacks because it decreases the denominator of points possible and at least slightly increases the value of those remaining. A similar adjustment is that the instructor could award full credit for the item to all students, regardless of their specific response. Alternatively, the instructor could retain the poorly performing item and award partial credit for some answer choices or treat it as a bonus. Depending upon the type and severity of the issue(s) with the item, either awarding partial credit or bonus points may be more desirable than removing the item from counting towards students’ total scores because these solutions do not take away points from those who answered correctly. However, these types of adjustments should only be done when the item itself is not highly flawed but more challenging or advanced than intended. 38 For example, treating an item as a bonus might be appropriate when p ≤.3 and d ≥ 0.15.

As a final comment on score adjustment, faculty members should note that course-based examinations are likely to contain quite a few flawed items. A study of basic science examinations in a Doctor of Medicine program determined that between 35% and 65% of items contained at least one flaw. 7 This suggests that faculty members will need to find a healthy balance between providing score-adjustments on examinations out of fairness to their students and maintaining the integrity of the examination by not removing all flawed items. Thus, we suggest that examination score adjustments be made sparingly.

Regarding revision of items for future use, the same guidelines discussed above and presented in Table 4 hold true. Item statistics are an important means of identifying and therefore correcting item flaws. The frequency with which answer options were selected should also be reviewed to determine which, if any, distractors did not perform adequately. Haladyna and Downing noted that when less than 5% of examinees select a given distractor, the distractor probably only attracted random guessers. 26 Such distractors should be revised, replaced, or removed altogether. As noted previously, including more options rarely leads to better item performance, and the presence of two or three distractors is sufficient. Examination reliability statistics (the KR20 or alpha) do not offer sufficient information to target item-level revisions, but may be helpful in identifying the extent to which item flaws may be reducing the overall examination reliability. Additionally, the reliability statistics can point toward the presence of multiple constructs (eg, different types of content, skills, or abilities), which may not have been the intention of the instructor.

In summary, instructors should carefully review all available item information before determining whether to remove items or adjust scoring immediately following an examination and consider the implications for students and other instructors. Each school may wish to consider developing a common set of standards or bet practices to assist their faculty members with these decisions. Examination and item statistics may also be used by faculty members to improve their examinations from year to year.

Assessment of student learning through examination is both a science and an art. It requires the ability to organize objectives and plan in advance, the technical skill of writing examination items, the conceptual understanding of item analysis and examination reliability, and the resolve to continually improve one’s role as a professional educator.

Types of Questions in Teacher Made Achievement Tests: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

When it comes to assessing students’ learning, teachers often turn to achievement tests they’ve created themselves. These tests are powerful tools that can provide both educators and learners with valuable insights into academic progress and understanding. But what types of questions make up these teacher-made tests? Understanding the various types of test items is crucial for designing assessments that are not only effective but also fair and comprehensive. Let’s dive into the world of objective and essay-type questions to see how they function and how best to construct them.

Objective Type Test Items

Objective test items are those that require students to select or provide a very short response to a question, with one clear, correct answer. This section will explore the different types of objective test items , their uses, and tips for constructing them.

Supply Type Items

- Short Answer Questions: These require students to recall and provide brief responses.

- Fill-in-the-Blank: Here, students must supply a word or phrase to complete a statement.

- Numerical Problems: Often used in math and science, these items require the calculation and provision of a numerical answer.

When constructing supply type items , clarity is key. Questions should be direct, and the required answer should be unambiguous. Avoid complex phrasing and ensure that the blank space provided is proportional to the expected answer’s length.

Selection Type Items

- Multiple\-Choice Questions \(MCQs\) : Students choose the correct answer from a list of options.

- True\/False Questions : These require students to determine the veracity of a statement.

- Matching Items : Students must pair related items from two lists.

For selection type items , it’s important to construct distractors (wrong answers) that are plausible. This prevents guessing and encourages students to truly understand the material. In multiple-choice questions, for example, the incorrect options should be common misconceptions or errors related to the subject matter.

Essay Type Test Items

Essay test items call for longer, more detailed responses from students. These questions evaluate not just recall of information but also critical thinking, organization of thoughts, and the ability to communicate effectively through writing.

Extended Response Essay Questions

- Exploratory Essays : These require a thorough investigation of a topic, often without a strict length constraint.

- Argumentative Essays : Students must take a stance on an issue and provide supporting evidence.

In extended response essay questions, students should be given clear guidelines regarding the scope and depth of the response expected. Rubrics can be very helpful in setting these expectations and in guiding both the grading process and the students’ preparation.

Restricted Response Essay Questions

- Reflective Essays : These typically involve a shorter response, reflecting on a specific question or scenario.

- Analysis Essays : Students dissect a particular concept or event within a set framework.

Restricted response essay questions are valuable for assessing specific skills or knowledge within a limited domain. When constructing these items, ensure the question is focused and that students are aware of any word or time limits.

Examples and Guidelines for Constructing Effective Test Items

Now that we’ve understood the types of questions, let’s look at some examples and guidelines for creating effective test items.

Objective Item Construction

- Multiple-Choice Example: “What is the capital of France? A) Madrid B) Paris C) Rome D) Berlin” – Ensure there’s only one correct answer.

- True/False Example: “The Great Wall of China is visible from space.” – Provide a statement that is not ambiguously phrased.

When constructing objective items, make sure the question is based on important content, not trivial facts. The length of the test should be sufficient to cover the breadth of the material, and the items should vary in difficulty to gauge different levels of student understanding.

Essay Item Construction

- Extended Response Example: “Discuss the impact of the Industrial Revolution on European society.” – This question allows for a broad exploration of the topic.

- Restricted Response Example: “Describe two methods of conflict resolution and their effectiveness in workplace settings.” – This question limits the scope to two methods and a specific context.

Essay questions should be open-ended to encourage students to think critically and creatively. However, they should also be specific enough to prevent off-topic responses. Providing a clear rubric can help students understand what is expected in their answers and assist teachers in grading consistently.

Teacher-made achievement tests with a mix of objective and essay type questions can provide a comprehensive assessment of student learning. By understanding the different types of questions and following the guidelines for constructing them, educators can create fair, reliable, and valid assessments. This ensures that the results truly reflect students’ knowledge and skills, allowing for targeted feedback and further instructional planning.

What do you think? How can teachers balance the need for comprehensive assessment with the practical limitations of test administration time? Do you think one type of test item is more effective than the other in measuring student learning?

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

Assessment for Learning

1 Concept and Purpose of Evaluation

- Basic Concepts

- Relationships among Measurement, Assessment, and Evaluation

- Teaching-Learning Process and Evaluation

- Assessment for Enhancing Learning

- Other Terms Related to Assessment and Evaluation

2 Perspectives of Assessment

- Behaviourist Perspective of Assessment

- Cognitive Perspective of Assessment

- Constructivist Perspective of Assessment

- Assessment of Learning and Assessment for Learning

3 Approaches to Evaluation

- Approaches to Evaluation: Placement Formative Diagnostic and Summative

- Distinction between Formative and Summative Evaluation

- External and Internal Evaluation

- Norm-referenced and Criterion-referenced Evaluation

- Construction of Criterion-referenced Tests

4 Issues, Concerns and Trends in Assessment and Evaluation

- What is to be Assessed?

- Criteria to be used to Assess the Process and Product

- Who will Apply the Assessment Criteria and Determine Marks or Grades?

- How will the Scores or Grades be Interpreted?

- Sources of Error in Examination

- Learner-centered Assessment Strategies

- Question Banks

- Semester System

- Continuous Internal Evaluation

- Choice-Based Credit System (CBCS)

- Marking versus Grading System

- Open Book Examination

- ICT Supported Assessment and Evaluation

5 Techniques of Assessment and Evaluation

- Concept Tests

- Self-report Techniques

- Assignments

- Observation Technique

- Peer Assessment

- Sociometric Technique

- Project Work

- School Club Activities

6 Criteria of a Good Tool

- Evaluation Tools: Types and Differences

- Essential Criteria of an Effective Tool of Evaluation

- Reliability

- Objectivity

7 Tools for Assessment and Evaluation

- Paper Pencil Test

- Aptitude Test

- Achievement Test

- Diagnostic–Remedial Test

- Intelligence Test

- Rating Scales

- Questionnaire

- Inventories

- Interview Schedule

- Observation Schedule

- Anecdotal Records

- Learners Portfolios and Rubrics

8 ICT Based Assessment and Evaluation

- Importance of ICT in Assessment and Evaluation

- Use of ICT in Various Types of Assessment and Evaluation

- Role of Teacher in Technology Enabled Assessment and Evaluation

- Online and E-examination

- Learners’ E-portfolio and E-rubrics

- Use of ICT Tools for Preparing Tests and Analyzing Results

9 Teacher Made Achievement Tests

- Understanding Teacher Made Achievement Test (TMAT)

- Types of Achievement Test Items/Questions

- Construction of TMAT

- Administration of TMAT

- Scoring and Recording of Test Results

- Reporting and Interpretation of Test Scores

10 Commonly Used Tests in Schools

- Achievement Test Versus Aptitude Test

- Performance Based Achievement Test

- Diagnostic Testing and Remedial Activities

- Question Bank

- General Observation Techniques

- Practical Test

11 Identification of Learning Gaps and Corrective Measures

- Educational Diagnosis

- Diagnostic Tests: Characteristics and Functions

- Diagnostic Evaluation Vs. Formative and Summative Evaluation

- Diagnostic Testing

- Achievement Test Vs. Diagnostic Test

- Diagnosing and Remedying Learning Difficulties: Steps Involved

- Areas and Content of Diagnostic Testing

- Remediation

12 Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation

- Continuous and Comprehensive Evaluation: Concepts and Functions

- Forms of CCE

- Recording and Reporting Students Performance

- Students Profile

- Cumulative Records

13 Tabulation and Graphical Representation of Data

- Use of Educational Statistics in Assessment and Evaluation

- Meaning and Nature of Data

- Organization/Grouping of Data: Importance of Data Organization and Frequency Distribution Table

- Graphical Representation of Data: Types of Graphs and its Use

- Scales of Measurement

14 Measures of Central Tendency

- Individual and Group Data

- Measures of Central Tendency: Scales of Measurement and Measures of Central Tendency

- The Mean: Use of Mean

- The Median: Use of Median

- The Mode: Use of Mode

- Comparison of Mean, Median, and Mode

15 Measures of Dispersion

- Measures of Dispersion

- Standard Deviation

16 Correlation – Importance and Interpretation

- The Concept of Correlation

- Types of Correlation

- Methods of Computing Co-efficient of Correlation (Ungrouped Data)

- Interpretation of the Co-efficient of Correlation

17 Nature of Distribution and Its Interpretation

- Normal Distribution/Normal Probability Curve

- Divergence from Normality

Share on Mastodon

Constructed Response Items

- First Online: 08 February 2023

Cite this chapter

- Mohamed H. Taha ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0808-5590 5

337 Accesses

Constructed response items (CRIs) are types of questions used to assess higher levels of the cognitive domain such as knowledge synthesis, evaluation, and creation. Many formats of CRIs are existing including long essay questions, short answer questions (SAQs), and the modified essay questions (MEQs). The aim of this chapter is to introduce you to CRIs’ different formats, applications, their strengths and weakness, and how to construct them.

By the end of this chapter, the reader is expected to be able to

Discuss the different types of constructed response items’ strengths and weaknesses.

Recognize how to create constructed response items.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Application of LSA to the Evaluation of Questionnaire Responses

Rater cognitive processes in integrated writing tasks: from the perspective of problem-solving

Predicting Reading Comprehension from Constructed Responses: Explanatory Retrievals as Stealth Assessment

Brown GA, Bull J, Pendlebury M. Assessing student learning in higher education. Routledge; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

Edwards BD, Arthur Jr W. An examination of factors contributing to a reduction in subgroup differences on a constructed-response paper-and-pencil test of scholastic achievement. J. Appl. Psychol. American Psychological Association; 2007;92(3):794.

Google Scholar

Rademakers J, Ten Cate TJ, Bär PR. Progress testing with short answer questions. Med. Teach. Taylor & Francis; 2005;27(7):578–82.

Article Google Scholar

Palmer EJ, Devitt PG. Assessment of higher order cognitive skills in undergraduate education: modified essay or multiple choice questions? Research paper. BMC Med. Educ. BioMed Central; 2007;7(1):1–7.

Schuwirth LWT, Van Der Vleuten CPM. Different written assessment methods: what can be said about their strengths and weaknesses? Med. Educ. Wiley Online Library; 2004;38(9):974–9.

Swanwick T. Understanding medical education. Underst. Med. Educ. Evidence, Theory, Pract. Wiley Online Library; 2018;1–6.

Ramesh D, Sanampudi SK. An automated essay scoring systems: a systematic literature review. Artif. Intell. Rev. Springer; 2021;1–33.

Feletti GI. Reliability and validity studies on modified essay questions. J. Med. Educ. 1980;55(11):933–41.

Walubo A, Burch V, Parmar P, Raidoo D, Cassimjee M, Onia R, et al. A model for selecting assessment methods for evaluating medical students in African medical schools. Acad. Med. LWW; 2003;78(9):899–906.

Elander J, Harrington K, Norton L, Robinson H, Reddy P. Complex skills and academic writing: a review of evidence about the types of learning required to meet core assessment criteria. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. Taylor & Francis; 2006;31(1):71–90.

Kim S, Yang JW, Lim J, Lee S, Ihm J, Park J. The impact of writing on academic performance for medical students. BMC Med. Educ. BioMed Central; 2021;21(1):1–8.

Freestone N. Drafting and acting on feedback supports student learning when writing essay assignments. Adv. Physiol. Educ. American Physiological Society; 2009;33(2):98–102.

Puthiaparampil T, Rahman MM. Very short answer questions: a viable alternative to multiple choice questions. BMC Med. Educ. Springer; 2020;20(1):1–8.

Schuwirth LWT, van der Vleuten CPM. Written assessment. Bmj. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2003;326(7390):643–5.

Verma M, Chhatwal J, Singh T. Reliability of Essay Type Questions—effect of structuring. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. Taylor & Francis; 1997;4(2):265–70.

Knox JDE. What is.… a Modified Essay Question? Med. Teach. Taylor & Francis; 1989;11(1):51–7.

Knox JDE. Use modified essay questions. Med. Teach. Taylor & Francis; 1980;2(1):20–4.

Al-Wardy NM. Assessment methods in undergraduate medical education. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. Sultan Qaboos University; 2010;10(2):203.

Bordage G. An alternative approach to PMPs. The" key Featur. concept. Further development in assessing clinical competence, Montreal Can-Heal …; 1987;59–75.

Farmer EA, Page G. A practical guide to assessing clinical decision-making skills using the key features approach. Med. Educ. Wiley Online Library; 2005;39(12):1188–94.

Hamdy H. Blueprinting for the assessment of health care professionals. Clin. Teach. Wiley Online Library; 2006;3(3):175–9.

Hift RJ. Should essays and other “open-ended”-type questions retain a place in written summative assessment in clinical medicine? BMC Med. Educ. BioMed Central; 2014;14(1):1–18.

Sam AH, Field SM, Collares CF, van der Vleuten CPM, Wass VJ, Melville C, et al. Very-short-answer questions: reliability, discrimination and acceptability. Med. Educ. Wiley Online Library; 2018;52(4):447–55.

Hauer KE, Boscardin C, Brenner JM, van Schaik SM, Papp KK. Twelve tips for assessing medical knowledge with open-ended questions: Designing constructed response examinations in medical education. Med. Teach. Taylor & Francis; 2020;42(8):880–5.

Feletti GI, Smith EKM. Modified essay questions: are they worth the effort? Med. Educ. Wiley Online Library; 1986;20(2):126–32.

Downing SM. Assessment of knowledge with written test forms. Int. Handb. Res. Med. Educ. Springer; 2002. p. 647–72.

Patil S. Long essay questions and short answer questions. Mahi Publications, Ahmedabad; 2020.

Hrynchak P, Glover Takahashi S, Nayer M. Key-feature questions for assessment of clinical reasoning: a literature review. Med. Educ. Wiley Online Library; 2014;48(9):870–83.

Fischer MR, Kopp V, Holzer M, Ruderich F, Jünger J. A modified electronic key feature examination for undergraduate medical students: validation threats and opportunities. Med. Teach. Taylor & Francis; 2005;27(5):450–5.

Further Reading

Downing, S. M. (2003). Validity: on the meaningful interpretation of assessment data. Medical education, 37(9), 830-837.

Downing, S. M. (2003). Item response theory: applications of modern test theory in medical education. Medical education, 37(8), 739-745.

Farmer EA, Page G. A practical guide to assessing clinical decision-making skills using the key features approach. Med Educ. 2005;39(12):1188–94.

Hift, R. J. (2014). Should essays and other “open-ended”-type questions retain a place in written summative assessment in clinical medicine?. BMC medical education, 14(1), 1-18.

Knox, J. D. (1989). What is.… a Modified Essay Question?. Medical teacher, 11(1), 51-57.

Knox, J. D. E. (1980). Use modified essay questions. Medical teacher, 2(1), 20-24.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Medicine and Medical Education Centre, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Mohamed H. Taha

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mohamed H. Taha .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Warwick, Coventry, UK

Hosam Eldeen Elsadig Gasmalla

College of Oral and Dental Medicine, Karary University, Khartoum, Sudan

Alaa AbuElgasim Mohamed Ibrahim

Medical Education Department College of Medicine, Qassim University, Buraidah, Saudi Arabia

Majed M. Wadi

College of Medicine and Medical Education, Centre University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Taha, M.H. (2023). Constructed Response Items. In: Gasmalla, H.E.E., Ibrahim, A.A.M., Wadi, M.M., Taha, M.H. (eds) Written Assessment in Medical Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11752-7_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11752-7_4

Published : 08 February 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-11751-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-11752-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Illinois Online

- Illinois Remote

- New Freshmen

- New International Students

- Info about COMPOSITION

- Info about MATH

- Info about SCIENCE

- LOTE for Non-Native Speakers

- Log-in Instructions

- ALEKS PPL Math Placement Exam

- Advanced Placement (AP) Credit

- What is IB?

- Advanced Level (A-Levels) Credit

- Departmental Proficiency Exams

- Departmental Proficiency Exams in LOTE ("Languages Other Than English")

- Testing in Less Commonly Studied Languages

- FAQ on placement testing

- FAQ on proficiency testing

- Legislation FAQ

- 2024 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2024 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2024 Cutoff Scores IMR-Biology

- 2024 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2024 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2024 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2024 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2024 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2024 Cutoff Scores French

- 2024 Cutoff Scores German

- 2024 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2024 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2024 Advanced Placement Program

- 2024 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2024 Advanced Level Exams

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2023 Cutoff Scores IMR-Biology

- 2023 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2023 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2023 Cutoff Scores French

- 2023 Cutoff Scores German

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2023 Advanced Placement Program

- 2023 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2023 Advanced Level Exams

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2022 Cutoff Scores IMR-Biology

- 2022 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2022 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2022 Cutoff Scores French

- 2022 Cutoff Scores German

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2022 Advanced Placement Program

- 2022 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2022 Advanced Level Exams

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2021 Cutoff Scores IMR-Biology

- 2021 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2021 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2021 Cutoff Scores French

- 2021 Cutoff Scores German

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2021 Advanced Placement Program

- 2021 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2021 Advanced Level Exams

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2020 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2020 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2020 Cutoff Scores French

- 2020 Cutoff Scores German

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2020 Advanced Placement Program

- 2020 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2020 Advanced Level Exams

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2019 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2019 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2019 Cutoff Scores French

- 2019 Cutoff Scores German

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2019 Advanced Placement Program

- 2019 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2019 Advanced Level Exams

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2018 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2018 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2018 Cutoff Scores French

- 2018 Cutoff Scores German

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2018 Advanced Placement Program

- 2018 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2018 Advanced Level Exams

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2017 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2017 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2017 Cutoff Scores French

- 2017 Cutoff Scores German

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2017 Advanced Placement Program

- 2017 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2017 Advanced Level Exams

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2016 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2016 Cutoff Scores French

- 2016 Cutoff Scores German

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2016 Advanced Placement Program

- 2016 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2016 Advanced Level Exams

- 2015 Fall Cutoff Scores Math

- 2016 Spring Cutoff Scores Math

- 2015 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2015 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2015 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2015 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2015 Cutoff Scores French

- 2015 Cutoff Scores German

- 2015 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2015 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2015 Advanced Placement Program

- 2015 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- 2015 Advanced Level Exams

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2014 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2014 Cutoff Scores French

- 2014 Cutoff Scores German

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2014 Advanced Placement (AP) Program

- 2014 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- 2014 Advanced Level Examinations (A Levels)

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2013 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2013 Cutoff Scores French

- 2013 Cutoff Scores German

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2013 Advanced Placement (AP) Program

- 2013 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- 2013 Advanced Level Exams (A Levels)

- 2012 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2012 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2012 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2012 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2012 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2012 Cutoff Scores French

- 2012 Cutoff Scores German