Researching Banned or Challenged Books: Resources for Challenge Research

- Resources for Challenge Research

- Was Winnie the Pooh Banned?

Key Resource

The key resource for researching why a particular title was challenged or banned are the publications of ALA's Office for Intellectual Freedom. The Office maintains information on which books are challenged and why and regularly publishes this information in the Journal of Intellectual Freedom and Privacy , where there may also be discussion of the events surrounding a challenge, and in a compilation published about every three years, most recently in Banned Books: Defending our Freedom to Read , edited by Robert P. Doyle. (Before 2016, similar information was in the Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom.)

Doyle and others used histories of censorship to compile the initial listing of challenged or banned books; this bibliography is in the Guide , as well as included on a list of books on censorship maintained by the ALA Library.

More recent entries are derived from the Journal of Intellectual Freedom and Privacy or Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom.

This publication is available in many libraries around the country, or may be ordered from the ALA Store..

- Books on Censorship Bibliography supporting research on censorship, banned and challenged books, and intellectual freedom. For researching why a particular book has been challenged, we recommend the Banned Books Resource Guide, which is represented on this list by the most recent editions, as well as the entry for the serial comprised of all the editions.

- Journal of Intellectual Freedom and Privacy The official journal of the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom (OIF). JIFP is a double-blind peer reviewed publication, topically focused on practical, moral, ethical, philosophical, and theoretical issues of intellectual freedom and informational privacy within the United States and globally. Published quarterly. more... less... Two most current issues are available by subscription only. Older issues are made available via open access at the link above. ISSN 2474-7459

- Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom Superceded by the Journal Of Intellectual Freedom and Privacy. The Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom was the only journal that reported attempts to remove materials from school and library shelves across the country. The NIF was the source for the latest information on intellectual freedom issues.

Additional ALA Resources

The Banned Books Week pages on the ALA website offer many ways to look at the challenge data that has been collection. The links provided here will be of use to students doing research.

- Challenged Classics (with reasons) The classics in the Radcliffe Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of the 20th century, with challenge reports from the 2010 edition of "Banned Books."

- Frequently Challenged Books Most current top ten, with links to statistical analyses and subsets.

- Mapping Censorship This map is drawn from cases documented by ALA and the Kids' Right to Read Project, a collaboration of the National Coalition Against Censorship and the American Booksellers Foundation for Free Expression. Details are available in ALA's "Books Banned and Challenged 2007-2008; 2008-2009; 2009-2010; 2010-2011; 2011-2012; and 2012-2013," and the "Kids' Right to Read Project Report." “Mapping Censorship” was created by Chris Peterson of the National Coalition Against Censorship and Alita Edelman of the American Booksellers Foundation for Free Expression.

- Read Banned Books YouTube Channel Videos of Virtual Read-Outs and other videos from ALA OIF.

- Timeline: 30 Years of Librerating :Literature Since 1982, Banned Books Week has rallied librarians, booksellers, authors, publishers, teachers, and readers of all types to celebrate and defend the freedom to read. To commemorate 30 years of Banned Books Week and enter our 31st year of protecting readers' rights, ALA prepared l this timeline of significant banned and challenged books. Timeline powered by Tiki-Toki.

Where else to look....

If your library does not have "Banned Books," use the library catalog to locate books on censorship. Useful subject headings are "Challenged books--United States" or "Censorship--United States."

Many libraries offer databases enabling access to periodicals and newspapers. Ask your librarian about accessing these--or visit your library's website, library card in hand, to access.

Use newspaper indexes such as the following to read coverage of book challenges in the communities where they occurred.

- LexisNexis - Full-text access to magazines and newspapers, including the New York Times.

- NewsBank - Full-text articles from major metropolitan newspapers.

- ProQuest Historical Newspapers™ - Digital archive offering full-text and full-image articles for significant newspapers dating back to the eighteenth century.

Use literature databases such as the following to seek out biographies of authors, book synopses, bibliographies, and critical analysis.

- Booklist Online - Reviews, awards information, some author information in editorial content

- Gale Literature Resource Center - Has full-text articles and book reviews, biographical essays.

- Library and Information Science Source - Full-text and indexed entries from library science literature, including major review sources

- NovelList - Includes reviews and reading recommendations, reading levels, summaries, and awards books have received.

Often, a general web search of < "[book title]" and (banned or challenged) > will yield up useful articles and blog posts about challenges. For example, < "looking for alaska" (banned or challenged) > will bring up newspaper coverage--as well as a video by the author--on the censorship challenges faced by Looking for Alaska , by John Green.

Other websites

- Banned Books that Shaped America The Library of Congress created an exhibit, "Books that Shaped America," that explores books that "have had a profound effect on American life." Below is a list of books from that exhibit that have been banned/challenged.

- Banned Books Week The Banned Books Week Coalition is a national alliance of diverse organizations joined by a commitment to increase awareness of the annual celebration of the freedom to read. The Coalition seeks to engage various communities and inspire participation in Banned Books Week through education, advocacy, and the creation of programming about the problem of book censorship.

- Books Challenged or Banned in 2014-2015 A bibliography representing books challenged, restricted, removed, or banned in 2014 and 2015 as reported in the Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom from May 2014 to March 2015 and in American Libraries Direct (AL Direct), by Robert P. Doyle.

- National Coalition Against Censorship Resources for School Teachers and Students Background on the legal and practical questions surrounding school censorship controversies.

- NCTE Intellectual Freedom Center Censorship Challenge Reports Teachers, librarians, school administrators, and parents call upon NCTE for advice and materials regarding censorship challenges in their schools or districts.

- University of Pennsylvania Library "Banned Books Online" A special exhibit of books that have been the objects of censorship or censorship attempts, linking to free e-books.

- Wikipedia's "List of books banned by governments" Tabular listing, alphabetical by title, of books banned by governments, worldwide.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Was Winnie the Pooh Banned? >>

- Last Updated: Mar 14, 2024 10:24 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ala.org/Researchingchallengedbooks

Morris Library

- 618-453-1455

- [email protected]

Banned Books: Protect Your Freedom to Read

- Protect Your Freedom to Read

- The Banned Book Collection in Morris

Banned Books Week is celebrated annually, with sponsorship from the American Library Association (ALA), the National Association of College Stores, and many other organizations. According to the ALA, "Banned Books Week highlights the benefits of free and open access to information while drawing attention to the harms of censorship by spotlighting actual or attempted bannings of books across the United States."

A Worrisome Trend

ALA's Office for Intellectual Freedom documented 1,269 demands to censor library books and resources in 2022, the highest number of attempted book bans since ALA began compiling data about censorship in libraries more than 20 years ago. The unparalleled number of reported book challenges in 2022 nearly doubles the 729 book challenges reported in 2021. Censors targeted a record 2,571 unique titles in 2022 , a 38% increase from the 1,858 unique titles targeted for censorship in 2021. Of those titles, the vast majority were written by or about members of the LGBTQIA+ community or by and about Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color.

- Censorship by the Numbers Resources documenting the number and locations of censorship attempts against libraries and materials compiled by ALA's Office of Intellectual Freedom.

- Book Ban Data, ALA Latest numbers from ALA about book bans and challenges in the United States, including preliminary data from the first half of 2023. TL;DR: They're up. A lot.

- Banned and Challenged Books ALA's page devoted to censorship attempts and the annual Banned Books Week celebration.

- Book Bans, PEN America Resources and commentary related to book bans in the U.S., including a comprehensive list of successful school bans, assembled by a national writer's association.

- Ralph E. McCoy Collection of the Freedom of the Press Housed in the Special Collections Research Center on the first floor of Morris Library, the McCoy Collection offers the opportunity to explore issues of censorship and freedom of expression from a historical perspective. It is one of the world's best collections of rare books highlighting the history of First Amendment freedoms. It includes examples of many books that have been banned in the United States and Europe over the centuries. Many of the books listed below part of this collection. more... less... used in Overview of African American history collections in SCRC on Resources for the Study of African American History in Southern Illinois: Overview of Special Collections

- Beacon for Freedom of Expression The Beacon for Freedom project maintains an extensive database of censored publications and publications about censorship.

Banned Books Club and Books Unbanned

The Banned Books Club is a collaboration between libraries and sponsors to make banned books available online and at libraries for free. The University of Chicago and the Digital Public Library of America are offering free access to all Illinois residents through the Palace app.

- Banned Book Club Program to provide free access to electronic copies of banned books. Follow the steps to "Access Banned Books" to get your free card and start reading.

- Banned Books Club at the Palace Project Jump straight to the app the Banned Book Club uses to provide access to available titles.

A number of public libraries nationwide have joined the Books Unbanned initiative, offering free access to commonly challenged or banned titles in eBook form to readers age 13-26. If you fall in that age bracket, sign up for a free temporary library card and read banned books!

- Boston Public Library Books Unbanned Program

- Brooklyn Public Library Books Unbanned Program

- Seattle Public Library Books Unbanned Program

Top Ten Challenged Books from the Last Five Years

Banned in 2021 - 2022

According to PEN America, 1,636 different books were banned—not only challenged, but actually removed from shelves—in classrooms, schools, or libraries in the U.S. for at least a portion of the time between July 1, 2021, and June 30, 2022. The following is a list of these banned titles available through Morris Library.

- Next: The Banned Book Collection in Morris >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2024 11:55 AM

- URL: https://libguides.lib.siu.edu/bannedbooks

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Current Events

Banned Books, Censored Topics: Teaching About the Battle Over What Students Should Learn

Suggestions for using recent Times and Learning Network articles, videos, podcasts, student forums and more.

By Katherine Schulten

Parents, activists, school board officials and lawmakers are challenging books at a pace not seen in decades. At the same time, schools are mired in debates over what students should learn about in U.S. history. In the last two years, dozens of state legislatures introduced bills that would limit what teachers can say about race, gender, sexuality and inequality.

All of this is part of a larger debate over politics in public school education. Across the United States, parents have demanded more oversight over curriculums, and school board meetings have erupted into fiery discussions.

How much do your students know and understand about these battles? To what extent have they affected your community, school and students? Why do they matter?

Below, we have collected articles, podcasts, videos and essays, from both The Times and other sources, that can help students think about these issues, and consider what they can do in response. We have also linked to our own related lesson plans, as well as to our Student Opinion forums , where your students are invited to join young people around the world to discuss their opinions.

And though we are publishing this collection during Banned Books Week , these issues are relevant far beyond one week in September. With the approach of midterm elections, for example, challenges to books and the conflicts that surround them are only likely to escalate. And, of course, all of these battles raise deeper questions about education, democracy and citizenship. We hope your students will find something in this collection that will engage them.

What’s happening right now and why?

True or False?

Attempts to ban books in the United States surged in 2021 to the highest level since the American Library Association began tracking book challenges 20 years ago.

The top 10 most-targeted books last year were all classics like “To Kill a Mockingbird” and “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.”

Polls show a majority of Americans support banning books.

Police reports have been filed this year against library staff over the books on their shelves.

A Florida law limits teaching on race and racism, including prohibiting instruction that would compel students to feel responsibility, guilt or anguish for what other members of their race did in the past.

(Answers: True ; False ; False ; True ; True )

How would your students do on that quiz? Invite them to brainstorm what they know — or think they know — about book bans and curriculum challenges around the country. As they work, ask them to be as specific as possible: Which books and topics have come under scrutiny? Why? They can also compile a list of the questions they have about these bans and challenges.

Depending on the time you have to devote, here are several ways to provide an overview:

Watch the video embedded above, from PBS News Hour.

Read this New York Times that summarizes the issue from September 2022: “ Attempts to Ban Books Are Accelerating and Becoming More Divisive .”

Use some of the statistics, charts, summaries and more in this comprehensive report from Pen America, “ Banned in the USA: The Growing Movement to Censor Books in Schools .”

Or, to understand the implications of these battles through the story of one small town, read or listen to an article from The Times Magazine, “ How Book Bans Turned a Texas Town Upside Down .”

Finally, if your students are ready, they can join young people around the world to post their thoughts in our Student Opinion forum that asks, What Is Your Reaction to the Growing Fight Over What Young People Can Read? You can also have them read and react to a selection of student comments responding to that prompt . (Or, they can view the answers students gave in 2019 to our question, Have You Ever Read a Book You Weren’t Supposed to Read? or to our 2017 question, Are There Books That Should Be Banned From Your School Library? )

Where do your students stand?

A December 2021 lesson plan, written in response to the Times article “ In Texas, a Battle Over What Can Be Taught, and What Books Can Be Read ,” includes an exercise in which students are given a series of statements adapted from the article and asked to decide to what extent they agree or disagree with them. Here are some of them:

Public schools are where a society transmits values and beliefs, so it makes sense that in this fraught and deeply divided time these kinds of arguments are happening.

Books or topics that make students feel discomfort, guilt or anguish because of race, gender or sexuality should not be taught in school.

Understanding our country’s history — including failures to live up to the promises of democracy — is an important part of education.

Teachers should explore contentious subjects in a manner free from political bias.

Lawmakers, politicians and parents should be able to tell teachers which books, articles, videos and other materials they are allowed to use in their classrooms.

It is the responsibility of schools to prepare students emotionally and intellectually with a diversity of voices, including some that challenge dominant historical and literary narratives.

Depending on your students’ background knowledge, the sensitivity of these issues in your community, and other considerations, you might do a similar exercise, either with these statements or with others.

You might distribute the statements to students and have them determine individually to what extent they “strongly agree,” “agree,” “disagree,” “strongly disagree” or are neutral or unsure. If you want them to turn these answers in to you, you might allow students to be anonymous. Or, if your class is ready to discuss these topics as a group, you can use the statements as a “ Four Corners ” exercise; as a “ Big Paper ” silent conversation in writing; or as prompts for partner, small group or whole-class discussions.

We are suggesting this exercise here as a kind of “warm-up” to deeper conversations, but it could also be used after your students have delved into any of the topics below.

What should we read in English class?

Listen to ‘The Argument’: What Should High Schoolers Read?

Kaitlyn greenidge and esau mccaulley on why america’s schools can’t get on the same page about required reading lists..

It’s “The Argument.” I’m Jane Coaston.

What should high schoolers read? It seems like a simple question, but it’s not. Book bans are at a historic high. Recently, the free-speech group, PEN America, has recorded more than 1,500 examples of books being banned to remove from schools. This isn’t new, exactly. There have been debates over “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” or “To Kill a Mockingbird.” But now, contemporary books like “Gender Queer,” by Maia Kobabe, and “The Hate U Give,” by Angie Thomas, are under scrutiny too.

What students can access at school matters. To me, English class is one of the few spaces we have left where students are forced to wrestle with big ideas, especially with people who disagree with them. So today, I want to get into what we’re really talking about when we debate high school reading. What ideas and experiences are we saying are OK, or not, to teach in the classroom? My guests today are Kaitlyn Greenidge and Esau McCaulley. Kaitlyn is a contributing opinion writer and the author of two novels, including “Libertie.” She’s helped design English curriculum for schools and taught writing for nearly 15 years. Esau is also a contributing opinion writer and a professor at Wheaton College. He’s the author of “Reading While Black: African-American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope.”

Hi Kaitlyn. Hi, Esau.

Thank you so much for joining me to talk about school. It’s funny, you know, when I graduated from high school, I was like, great, never have to talk about school again, never have to wake up at 6:30 in the morning again. Here we are.

So I thought it would be helpful to start out the conversation with a throwback question just to get us grounded. Kaitlyn, what was high school English class like for you?

Oh, that’s a great question. So I went to a really tiny high school in Boston where there’s only, like, 30 people in each class — in each grade, I should say. So it was sort of like college-seminar style. We all sat around a really big, grand table and what we read was very traditional, kind of like the great 19th-century novels.

Every term we read at least one Shakespeare play. And when you started in the school, every single person had to read the “Odyssey” over the summer. And then, the first semester you were there you were just talking about the “Odyssey.” So that was what high school English was like.

Wow. Esau, what was high school English class like for you?

I went to a school that was a lot bigger. It had about a thousand students in it. It was inner city, which is often code for Black. It was like a Black high school in Huntsville, Alabama. And so I went into Advanced English, mostly because I wanted to have some space to discuss things. And in some ways, it was similar.

I had two English teachers. One was a Black English teacher. And then, later, I had a white English teacher. And the Black English teacher really focused on our ability to read well, to write well and to argue well. And the same thing with the white teacher, but the Black teacher made it almost like a point of racial pride that you will read and write well for the people.

And so I remember English as a place where I fell in love with reading and ideas. And we read some of the traditional stuff as well. And we read Shakespeare, but I think we also squeezed in some Black novels here and there.

So I went to an all-girls private school in Cincinnati, Ohio. It’s a Catholic school, which in Cincinnati, which is very Catholic city, is very common. I went to Ursuline Academy. Go Lions. And I remember being — it’s an all-girls school, so every other girl in my class loved “Pride and Prejudice.” And I loved “Catch-22.” And I was like, we are not the same.

But I actually never had a Black teacher while I was in high school. It was a majority white high school. I grew up having access to all of my parents’ books. My dad is a retired librarian. So I just read all the time, and my dad brought home books all the time.

But we’re going to be talking about what kinds of books we think should be taught in the classroom. And I think my perspective is very, like, teach them all, teach everything. But I want to give some context to where we’re each coming from. So let’s start with this. What do you think is the goal of high school English class? Kaitlyn, do you want to start?

Sure. I mean, I think the goal of high school English is, number one, learning how to read a text, learning how to distinguish in a text between different figures of speech. You know, I taught writing to this age group, to high school students, off and on for about 15 years. I was like a creative writing instructor in various modes in Boston and New York. And I also used to write curriculum for a for-profit company for a number of years.

And through my work as a novelist, I often get asked to go to a lot of classrooms and interact with a lot of high school students around texts. And so I think, particularly in this moment, the most important thing is sort of, number one, learning how to read a text and understanding different modes of communication. So what’s the difference between hyperbole versus what is being used in metaphorical language versus literal language? All those things that —

What is satire?

What is satire.

Which seems to be something we fail at all the time.

Right, right, what is satire. All these modes of address that are used interchangeably throughout our culture constantly, throughout different forms constantly, that many people sort of maybe have heard the word of and think they understand, but most of us are using either incorrectly or misunderstanding. And I think that’s a really important skill that I see people who have PhDs who don’t seem to be able to do that.

So, to me, it’s a really important issue because I think it decides so much of our public discourse. When you lose those abilities, when you lose that tendency, all else is lost. You can’t really have conversations. And you especially can’t have conversations across class lines, across race lines, across gender lines, if you don’t have those skills.

I mean, that’s one of the amazing things about American culture is all of our subcultures that have these particular languages and ways of speaking. And if you don’t have the ability to even just appreciate that that’s a fact, you are going to have a really hard time moving forward in this country.

Right. Can you give me an example of when you’ve seen, as you mentioned, people with PhDs, failing to close read?

Well, in that instance, I think it’s probably, for me, I think the thing that pops into my mind right now is the continual denigration of a word like woke, which Black people keep saying, like, this is the history of where this word came from. This is why we came up with this word. This is why we came up with this language around this word to describe a very particular experience of living in America that we have tracked since we’ve been here, that’s been a part of our literary tradition since we’ve been here.

And we also know, knowing that tradition, that it is also a tradition for white dominant cultures to come in and to corrupt our language and to turn it into something else. And that’s what’s happening here.

But that word is very seductive for a very large portion of white America to just sort of throw everywhere.

And so I think the arguments or the conversation you could have around what do you actually mean when you’re saying that word would be — I don’t think they’d be easier, but they would be — we could maybe have a little bit more traction if people had the ability to understand and talk about figurative language, the uses of language, how people have used language both as resistance and as self-determination.

And I think if you can talk about texts, and if teachers can have the ability and freedom to talk about texts in those sorts of ways, students can be prepared when they enter into the larger world to enter into these discussions in actually intelligent ways.

Esau, what do you think is the goal of high school English?

I think that she did a great job of capturing the discussion of the skills necessary and how those things are going to help you in life. But I want to speak a little bit about what I think texts do and how a text changed my life. When I think of reading a work, it’s like I’m entering into the narrative world of the writer. And normally, the writer has something to say about life, what it means to be human, about love, about joy, about sorrow.

And I think that great fiction writers and great fiction are driven by this question about making sense of the world. And so I think a good English class — this may be overly simplistic — it’s to get our students to lift their head above the question of how can I make the most money or acquire the most things, to ask the deeper questions of meaning.

And as a teacher — and I taught high school and I teach in college now — the hardest thing to do is to get the student to think. And so great literature and great English class just makes the students engage. It overcomes that cynicism. Cynicism, I think, is a manifestation of insecurity because you’re afraid to care. And if you care and you fail, then you hurt.

And so I think that the goal of good English is to get the students to think. Every time I read a book or I read an article, I’m opening myself up to someone who thinks differently than me, who can better inform how I live and move and breathe.

I think that’s really important. And I just want to add, the reason why great literature is great literature is because it’s often about people who hold vast contradictions in themselves, in which there are no easy answers, in which there is no real clear resolution, in which whenever you come back to that text, you find new questions to ask yourself. You know, there’s that famous James Baldwin quote, art is supposed to be asking you sort of continual questions.

And so I think probably for many people who have bad experiences in English classes, it’s because your teacher, or your curriculum, or your school is ignoring all those things. And it’s sort of treating literature as a moral high ground or treating literature as a place where you can’t have those questions, or you can’t dissent, or you can’t say I hate this book because it does X. I think those are probably the places where most people, when you ask them what book did you hate reading in high school, and everybody is sort of like, I hated “Catcher in the Rye” because I was the only person who understood Holden wasn’t an a-hole or whatever. Which you’re like —

Holden Caulfield was a giant jerk.

And I feel as if —

— we don’t talk about that enough.

But that’s the whole point of the book, right? The whole point of the book is, he’s a 13-year-old, or however he’s supposed to be year-old, a-hole who’s grown up rich and privileged. The author knows that.

They know that when they put that on the page. And so I think it’s a detriment to how that book is taught that so many people feel like that’s somehow a new revelation that nobody has talked about before, when, hopefully, a teacher teaches that book as like, this guy is an a-hole. We’re going to read about him. He’s going to piss you off. And we’re going to talk about how the author made that happen on the page and what are the things that are making you mad about this character. And then, hopefully, the next level is, you’re all the same age as this character, so what are the things that this character is doing that’s similar to what you are doing right now —

— that you may not particularly be happy or proud about in your own life. That, to me, is the entry point into a novel or getting a teenager into talking about a book. So then you can talk about those bigger things like metaphor, like imagery, like what is Salinger doing here on this page when he’s doing — like, that’s the entry conversation that you have into that book, to be able to have that higher-level conversation about how a book actually is built and operates.

Right. And I think that that gets to the conversation that we’re having about English class as a place to learn critical thinking skills, even about yourself, to think critically about yourself and the role that you play in the world, versus English class as a place to think about the big questions, which I kind of think it’s both.

And I remember my own experience with English class. And I think one of the most useful parts was being exposed to some of the classics because I felt as if I was connected to everyone else had ever read those books. Especially when we have so many different experiences of living in the same country, these books give us something to share and a common language to have.

And I think that that gets actually at why these conversations about what kids read in school are as contentious as they are. But I also think that the debates that we have about what we read in English class are actually debates about what kinds of communal values we hold as a country. What do you think, Kaitlyn?

I think that’s true. I think when you’re talking about what we should read in English class, you’re really talking about how to make a common language for people to talk across. And if we are such a diverse nation racially, economically, culturally, regionally, there has to be some sort of touchstone for people to be able to have common ways to talk about the human experience and to talk about themselves.

And a very good curriculum would do that, would have books sort of across the spectrum and books by people across time and across different cultures. Because I think what often tends to happen, too, is when we say we want books with big universal themes, a lot of times people interpret that to mean books in which Black people and people of color are not present because we are not universal. Our experiences are somehow not universal, right?

So, like, Jane Austen is universal. Toni Cade Bambara is not, right? That’s kind of the distinction that people make. And I think that when we say we want sort of like a big universal curriculum, we have to be really specific about what that means. And for me, the universality comes from taking texts from all of these different cultures and comparing texts across cultures to find a common denominator. I understand why we had to read the “Odyssey” in ninth grade. I’m grateful for it. I think it was very helpful. I also think it would have been really helpful to read alongside it epics from Mali and from precolonial India and other places to be able to understand the epic tradition. I think that would have been a more interesting class.

The Western canon was created before Black people got a vote. And after it was established, as society has progressed, we’ve tried to sneak in the occasional Black author. And now Zora Neale Hurston is often included there. Toni Morrison is often included there. But it’s a corrective. It’s almost like there’s not enough space because so much of the space was taken up before they really considered other voices.

And so I do I believe that we need to reconsider who and what makes up a common language, which seems to be impossible right now in a country that seems to be ripping itself apart around identity issues.

But I also want to say that there’s something to be said about the limits of something like a universal canon. So I think that it might be important, if I’m in the South, where I grew up, I might have two or three extra books about what it means to be in that region of the country, and literature that is distinctly Southern.

So I think there might needs to be a universal — like a shared canon with some kind of regional emphases. And I would also suggest that it is not so much that we all have read the same books, but if we could kind use our regional literature as a way of asking these questions, and then we’re bringing out people who have more empathy. Like, everybody can read the same books and come out equally racist or sexist, right?

Right. I’m always struck by how we talk about the canon. And I’m so glad that you brought that up. I am attracted to the idea that there is a set of texts that is so universally important and also so universally applicable that everyone should read them, even just to understand what we’re all talking about.

I talk all the time about how I think that reading religious texts as literature — Esau, you’ll get this — that there are times in which I make what I believe to be bog-standard biblical references, and people just have no idea what I’m talking about. And I’m just like, you know, like, the Prodigal Son.

Yeah, like, anyway, he left. It’s fine. But I’m curious, Esau, how do you define the canon, such as it exists?

Oh, man, I’m going to have to leave that statement that you tossed out about reading biblical text to the side because there’s probably no other thing plaguing America more than our poor reading of our religious texts, which is an issue for another day.

I would define that canon as those books that, by their very merit, stick with us. And we have to ask the question, why do we keep reading Tolstoy? And I think we keep reading Tolstoy because he’s amazing. And so part of it is something about quality. But there’s also times where books, they so much capture a moment in time and in history that you can’t talk about that portion of American life or world history without them.

So I think that the canon is those books.

And I don’t so much begrudge the — I call it the pre-integration canon, like the white canon that was constructed and given to students with little regard to Black people, except for the fact that we did not reconsider that, as a community, when we came of age. In other words, it was a settled group of texts to which you could then add a few Black voices here and there and then a few Latino voices here and there. But I think that we really need to step back and say, OK, now that we recognize that this was rooted in a hierarchy in which white culture is at the top and Black culture is at the bottom, what is our new understanding of what is valuable, and what are some of those books that we thought that we had to read that could actually be captured just as well by authors from other cultures?

I would also just add to that, books are not created in a vacuum. They’re written in the historical tensions of the times that they were written. So I think, even if you were to say we’re going to just stick with the Western canon that was created pre-integration or whatever, you can teach those books by talking about what is in them and what has been left out.

So you can teach “Persuasion” and point out that, when it was being written, there’s a whole question in the larger British empire of what’s going to happen around slavery and emancipation and the intense wealth that came from slavery for many of these characters. And that’s the subtext of all these questions about who’s getting married or whatever. They’re really talking about who’s transferring blood money from place to place.

What if we talked about “Persuasion” in that sort of way, and how everybody who is a part of that culture knows that that’s where the money is coming from? And how does that affect people’s sort of like interior lives, or doesn’t it affect their interior lives? I would make the argument that that’s perhaps where a lot of the emotional construction comes from in those cultures, is knowing that you can’t actually name sort of the great terror that is propping up your whole life.

That’s me as a novelist going off and way, way psychoanalyzing. But there’s a way where you could make that argument around those texts. And I keep thinking about there was the terrible shooting at the supermarket in Buffalo. And the shooter was talking about the Great Replacement theory. And at first, the sort of thing was like, this is such a fringe theory, fringe theory. And you know, you have to point out, they talk about the great replacement theory in “The Great Gatsby.” That is a important subplot of “The Great Gatsby,” that Daisy’s husband is a white supremacist, is afraid that white people are dying off.

So like, why aren’t we talking about that in those texts? That doesn’t have to be the sole discussion you have about “The Great Gatsby.” But that’s a really important point to talk about, that that was sort of like the milieu that this book was written in, and that fear of losing white power is a huge theme in the book. That’s what “The Great Gatsby” is about.

So I think we can talk about these books in a much more nuanced way. And unfortunately, I think a big part of it that we’re not saying is that now teachers have very, very good reason to fear even pointing those things out.

Right. And I think that that context is so important. I know that, in my entire life, there’s been this debate about taking out “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” from readings. And part of it is because, I think, of that lack of context in which Finn decides that he is not going to return Jim, the runaway slave, to his owners.

And he believes, in the context in which he is living, that the line is, all right, then, I’ll go to hell. This idea that if I have to decide between following societal norms and returning a runaway slave, who was believed, in his context, to be property, I would go to work and steal Jim out of slavery again. And as long as I was in, I would go whole hog.

And I think about that a lot and about how it seems to be very difficult to talk about the context in which these books are written. It’s difficult to talk about how “The Great Gatsby” is written at a time of both immense white success but immense white fear about what immigration means. Because in many ways, they’re not necessarily even talking about Black people.

No, they’re just talking about other slightly less white white people.

They’re talking about, like, Italians. Like, the passing of the great race is —

Spicy whites, yes, spicy whites.

The passing of the great race is like, we might have too many Czechoslovakians.

So what I’m hearing, Kaitlyn, is that this is not necessarily about the books. This is about the teaching.

Yeah, I think — you brought up “Huckleberry Finn.” That’s a fantastic example because that is a question of teaching. And the flip side of this great question of what Finn is doing is, I think, every single Black person who you talk to, who has gone to a school with mostly white teachers or with all white students, has a story about being forced to say the n-word by a teacher in reading that text out loud.

Yes, exactly.

So we have to talk about that part of it, of text used in domination by white teachers over students of color and Black students, in a very particular way. Which I think is the other side of this that people feel really strongly about the canon because of those white supremacist teaching techniques that are built into our education system and that many white teachers, both vindictively and thinking that they’re doing the right thing, force students into these interactions.

This is the thing that I think that people get wrong in this conversation if they think they can settle the proper formation of our students by the books that they choose to put in the canon. But I do want to say that a lot of this comes down to the formation of our teachers and the ways in which they teach students to engage text. And that’s something that you can’t do by the canon. You can’t have a book that a teacher can’t ruin.

So I guess one of the experiences that I remember being most traumatizing is, this book is so good that we need to just ignore the racism —

Uh-huh, yes.

— and look at it as literature. And it’s such great literature, let’s just ignore this kind of — no, no, no.

“Heart of Darkness,” yeah.

Like, it’s so good, ignore the racism. I was like, well, no, that is the thing that is making me feel uncomfortable in class. And had you sat down with me in that class and said, OK, we’ll have a session or two where we talk about this problematic aspect and then we can talk about their use of metaphor. OK, fine, right?

But I think that one of the things that is underneath that is this fear that if we acknowledge the racism that is in our literature and we make that a point of emphasis, then that reality runs through all of American history and culture.

In other words, you can’t tell the story of any aspect of American greatness without saying the place or that it’s tainted by racism. And when you speak about that tainting by racism, people feel like the greatness is all gone. And so they say, let’s just downplay the racist part and look at the glory. And I just can’t help but see the racism.

And so I think that’s what makes the discussions around the canon complicated. Because the teacher has to be able to see these texts as both powerful and profoundly broken because they’re written by humans who often have those contradictions in themselves.

Yeah, and I think another detriment to how teachers are supported is that, oftentimes, there is no space even to have that conversation and to point out that people have been noticing this about this book for generations. You’re not the first reader to notice this. So, you know, how helpful would it be if you were to read “Heart of Darkness,” say, and your teacher had the time and space to also put Chinua Achebe’s essay critiquing it beside you?

So I think one of the reasons why that doesn’t happen is, number one, teachers don’t have any space and time and money for it. And number two, subconsciously, to know that you are not the first person pointing this out, to know, in fact, that there’s a whole tradition of writers of color and Black writers who, for centuries, have pointed to places in the canon and said, actually, no, this is what is wrong. Actually, no, this seems to be here. Actually, no, I’m going to fill this space with something else.

That’s very, very, very profound and cuts sort of like at the heart of white supremacist culture. And so it’s much easier, in many ways, to say to a student, yeah, you’re the only one who noticed that “Heart of Darkness” is racist, instead of saying, you’re part of a long lineage of people who noticed this and who did work to try and point it out.

I think it’s worth acknowledging, and we know this, that the canon is always evolving, whether we like it or not. And some works become more meaningful over time, and some lose resonance. I remember when I was in sixth grade, we read “Our American Cousin,” which is the play that Abraham Lincoln was seeing when he was assassinated. Friends, it has —

it has not stood the test of time, because most things don’t. Our canon changes. Sometimes the book is going to last the test of time. Sometimes it’s going to be “Avatar.” So what do you see as the goal of revising the canon? Should it be to mirror what’s taking place or mirror what should be taking place? How do you think about this?

I think, in order to reform the canon, we have to get underneath this American fear as to relate to both the power and the limitations of books. So for example, I read “Crime and Punishment,” and I didn’t become Orthodox.

I read Malcolm X and I didn’t join the Nation of Islam. A book can be powerful, and it can change you, and you don’t have to adopt everything in the book. So I think that we overestimate the power of literature as it relates to an ideology. So I think that the first thing we have to do is get underneath this American fear of control and producing certain kinds of citizens that we think are going to help us be who we’re going to be, and just open ourselves up to great literature from wherever it arises.

When we begin to think about the canon, I think the first question is underrepresentation. Who have we historically underrepresented? And who from that community can lift those works up and say we missed it?

Yeah, I just want to say, you said so eloquently, Esau, this question of control, which is such a ribbon through American culture that just really corrupts so much, this desire to control. And so I think, again, thinking of the canon as a gateway and as a tool, and less as sort of like a prescriptive or as a way to judge who knows and who doesn’t know what’s in the canon, or a way to judge have you been taught correctly or are you an imbecile.

If we think of the canon as simply like a tool to help us, I think that opens up a lot, sort of thing. But ultimately making any sort of canon is propaganda. That’s just, like, the name of the game.

So I think this question of opening up, yeah, control, and understanding that students are going to come to the text in any sort of way that they come to it, and that’s part of what reading is. If someone’s takeaway is different than yours, that doesn’t mean that the text has failed or that the canon is corrupting people or the canon isn’t good anymore. It just means that you are two humans reading a book, and you came to different conclusions.

Esau, you brought this up, about how people seem to think that if you read a book, you will immediately be inculcated by what the book is telling you, which just like — if that’s how school worked, school would be very different.

And I would also argue — and I hate this term — but I do think, in some ways, historically, what we want kids to read in schools is often a form of signaling to other people, a form of virtue signaling even. And I actually see, in some ways, that the recent wave of attempted book bans, I think that there are some where people are like, oh, this book is too complicated for this age group, or something like that.

But at a same point, these gestures are kind of symbolic. Kids can find these books elsewhere or find them on the internet. So these bans actually say more about what ideas adults are afraid of their children getting exposed to, whether it’s the existence of racism or whether it is discussions of L.G.B.T. issues —

I just push back on it, them being symbolic. They actually affect the bottom line of what children’s and middle-grade literature will be published in the coming years because children in middle-grade literature marketplace is mostly libraries and schools. So when they are banned in a civic place like that, that means that those places won’t order those things, and book publishers will lose that very huge part of revenue. So it actually is not symbolic. It actually affects book acquisition and which books will be published about what subjects, three, four, five years down the line.

That’s a good point. But, Esau, you brought up that it’s hard to tell whether kids think about these books this way at all. So I’m curious about how should we think about the kinds of moral conversations that books are or aren’t able to offer us?

I have a teenager and now a soon-to-be teenager in my house. They’re my children. And so I used to have this idea of, like, that — I don’t know why you lie to yourself once you get older. Because once you have children, you begin to think that you have more influence over them than you do.

And so what I realized with my children, even my son, who’s the oldest, I can present opportunities for him to think about the world via stories that I tell, books that we engage, but ultimately, he has to make the decision for himself, the kind of person that he is going to be. And I’m his parent.

And I think that, in a similar way, and probably even a lesser way, teachers have that same responsibility. They can’t control what students become. They can present them options. And if there was a simple answer to what people are going to become, we would all become that thing.

And so what literature is are these different explorations into what it means to figure out how to be a human. And I think that a good teacher doesn’t say, I’ve solved the problem. It’s like, these were books that were formative to me as I began to make sense of myself. And I think that once we recognize how open the human person is, then we might begin to be a little bit less fearful.

And I’m sorry, this might be a strange analogy, but the Black experience is paradigmatic of that. They tried to convince us for hundreds of years. They limited our reading. They did everything to convince Black people that God wanted us to be enslaved and God wanted us to be submissive. And Black people said, nah, I’m good with that. We refused the propaganda.

And I think the human spirit refuses to believe something that it doesn’t know to be true. And so once we recognize that, we recognize the limits of any form of education and literature. And so then we begin to see education as a guided journey of discovery, where we present to students things that we or the world has found helpful in that process.

I would just say that one of the things that happens, especially around book banning, around, I would say, queer and L.G.B.T.Q. books, is the idea that you’re the only person who’s felt a certain way, or had certain feelings, or looked at the world in a certain way is very seductive for some people. But the negative side of that is the intense isolation that comes from it.

So I think, as much as it is about morals, it’s also about really trying to not let queer children know that their experience is a part of the human experience. Like, that’s what it’s about, right? It’s hoping to say, you can’t go to a book to know that, five years ago or 10 years ago or right now, someone is having these same feelings. You’re just going to suffer alone. And you’re going to stew in that shame and ignorance and sadness about yourself into adulthood. And maybe you’ll be able to figure it out then, but we’re not going to try and give you the tools to talk about any of the complications of that feeling now.

And that’s a real political project, right?

And that’s where, I think, this is where it’s an all-hands-on-deck type of situation. Public education in this country is why this country has done anything good. Let’s just be really clear. That’s the only reason, in this broken nation, why anything good has happened is because we’ve had public education for the last 160 years, or since Reconstruction, essentially.

So I think this is an all-hands-on-deck situation where, if you care about these things, you want to figure out how you can support the public school teachers in your community to make that happen. A teacher needs to feel that their community is going to stand behind them against these sort of outsized astroturfed assaults on what they’re doing.

This has been an incredibly insightful conversation. Kaitlyn, Esau, thank you so much for coming on the show. [MUSIC]

I love talking with you, Esau. I love talking with you, Jane. Thank you.

Thank you for having us.

Kaitlyn Greenidge is a contributing Opinion writer and the features director at “Harper’s Bazaar.” Her latest novel is “Libertie.” Esau McCaulley is a contributing Opinion writer, an associate professor of New Testament at Wheaton College, and a theologian-in-residence at Progressive Baptist Church in Chicago.

This episode is part of a series Times Opinion is doing right now, called “What is School For?” You can find a link to the other stories from parents, teachers and students, and more, in our episode notes.

“The Argument” is a production of New York Times Opinion. It’s produced by Kristin Lin, Phoebe Lett and Vishakha Darbha. Edited by Alison Bruzek and Anabel Bacon, with original music by Isaac Jones and Pat McCusker; mixing by Pat McCusker. Fact-checking by Kate Sinclair and Michelle Harris. Audience strategy by Shannon Busta, with editorial support from Kristina Samulewski.

What is the purpose of English class? Why do we read and talk about books together? What books should we read? Why?

In this podcast, for which you can also find a transcript , the host Jane Coaston interviews Kaitlyn Greenidge and Esau McCaulley, writers who have also been high school teachers. Their conversation is wide-ranging and full of possibilities for class discussion.

For instance, here is a snippet of a section on the questions of what to teach and why:

Kaitlyn Greenidge I think when you’re talking about what we should read in English class, you’re really talking about how to make a common language for people to talk across. And if we are such a diverse nation racially, economically, culturally, regionally, there has to be some sort of touchstone for people to be able to have common ways to talk about the human experience and to talk about themselves. And a very good curriculum would do that, would have books sort of across the spectrum and books by people across time and across different cultures. Because I think what often tends to happen, too, is when we say we want books with big universal themes, a lot of times people interpret that to mean books in which Black people and people of color are not present because we are not universal. Our experiences are somehow not universal, right?

What do your students think? What do they read in your class, and who or what determines that mix? What would they say should be the purpose of English class?

What ideas from this episode resonate with them — and with you?

What is the purpose of teaching U.S. history?

In the section above, we used a Times podcast to focus on the question of what English class is for. Now we turn to a Times video interactive that poses similar questions about U.S. history classes.

In the last year, 17 states have imposed laws or rules to limit how race and discrimination can be taught in public school classrooms. Some of the discussion has been fueled by the 1619 Project , developed by The New York Times Magazine, which argues that “the country’s very origin” traces to when the first ship carrying enslaved people touched Virginia’s shore that year. “Out of slavery — and the anti-Black racism it required — grew nearly everything that has truly made America exceptional,” it explains.

In response to bans on teaching with the 1619 Project in states like Florida and Texas, the editor in chief of the Times Magazine, Jake Silverstein, wrote an essay called “ The 1619 Project and the Long Battle Over U.S. History .” Here he describes how these bans seem to see history as somehow fixed and immutable:

In privileging “actual fact” over “narrative,” the governor [Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida], and many others, seem to proceed from the premise that history is a fixed thing; that somehow, long ago, the nation’s historians identified the relevant set of facts about our past, and it is the job of subsequent generations to simply protect and disseminate them. This conception denies history its own history — the dynamic, contested and frankly pretty thrilling process by which an understanding of the past is formed and reformed. The study of this is known as historiography, and a knowledge of American historiography, in particular the way our historical profession evolved to take fuller account of the role of slavery and racism in our past, is critical to understanding the debates of the past two years.

Many of these laws have also taken aim at what has been labeled critical race theory — an academic legal framework for understanding racism in the United States developed during the 1980s — while others are crafted more broadly to address what Republicans call “divisive concepts.”

What should students learn about our country’s history? What, if anything, shouldn’t they learn? In our recent lesson plan we quote a teacher from the video interactive and pose these questions for students:

“It’s the job of a history teacher to tell the full and complex story of U.S. history.” What does that mean to you? Do you think you have learned the “full and complex story” of U.S. history? If not, what do you think has been missing?

Here are three recent Learning Network lesson plans that can help you go further:

Lesson: The Debate Over the Teaching of U.S. History

Lesson: ‘Critical Race Theory: A Brief History’

Lesson: ‘Two States. Eight Textbooks. Two American Stories.’

And here are two Student Opinion forums to which your students are invited to contribute their thoughts — or read the responses of other young people:

What Is the Purpose of Teaching U.S. History?

What Is Your Reaction to Efforts to Limit Teaching on Race in Schools?

Were your students’ minds ever “disturbed by a book”?

Before your students read Viet Thanh Nguyen’s essay, “ My Young Mind Was Disturbed by a Book. It Changed My Life. ” you might ask them to write or talk about questions like these:

What book have you read, in or out of school, recently or when you were younger, that elicited a strong emotional reaction in you?

You might have felt joy, sorrow, anger or hope. You might have recognized yourself and your world in this book — or it might have introduced you to new ideas and worlds. How did it affect you?

To follow up, you might ask them: Can a book be dangerous? Can a book harm a reader? How? If books can be harmful, is it appropriate for schools to protect students from them, either by taking them out of the curriculum or off library shelves? What examples can you offer?

In the essay, Mr. Nguyen writes about how, as a Vietnamese American teenager, he came across Larry Heinemann’s 1977 novel, “Close Quarters,” about the war in Vietnam, and “was not prepared for the racism, the brutality or the sexual assault.” He writes about how the book affected him, and how, years later, he wrote his own novel, “The Sympathizer,” about that war.

He continues:

Books can indeed be dangerous. Until “Close Quarters,” I believed stories had the power to save me. That novel taught me that stories also had the power to destroy me. I was driven to become a writer because of the complex power of stories. They are not inert tools of pedagogy. They are mind-changing, world-changing. But those who seek to ban books are wrong no matter how dangerous books can be. Books are inseparable from ideas, and this is really what is at stake: the struggle over what a child, a reader and a society are allowed to think, to know and to question. A book can open doors and show the possibility of new experiences, even new identities and futures.

As this essay points out, the questions around banning books “aren’t just political; they’re also deeply personal and intimate.” How have they affected your students? What stories can they tell about the role of a book, or some other form of culture, in their lives? Where do they stand on the idea that “those who seek to ban books are wrong no matter how dangerous books can be”?

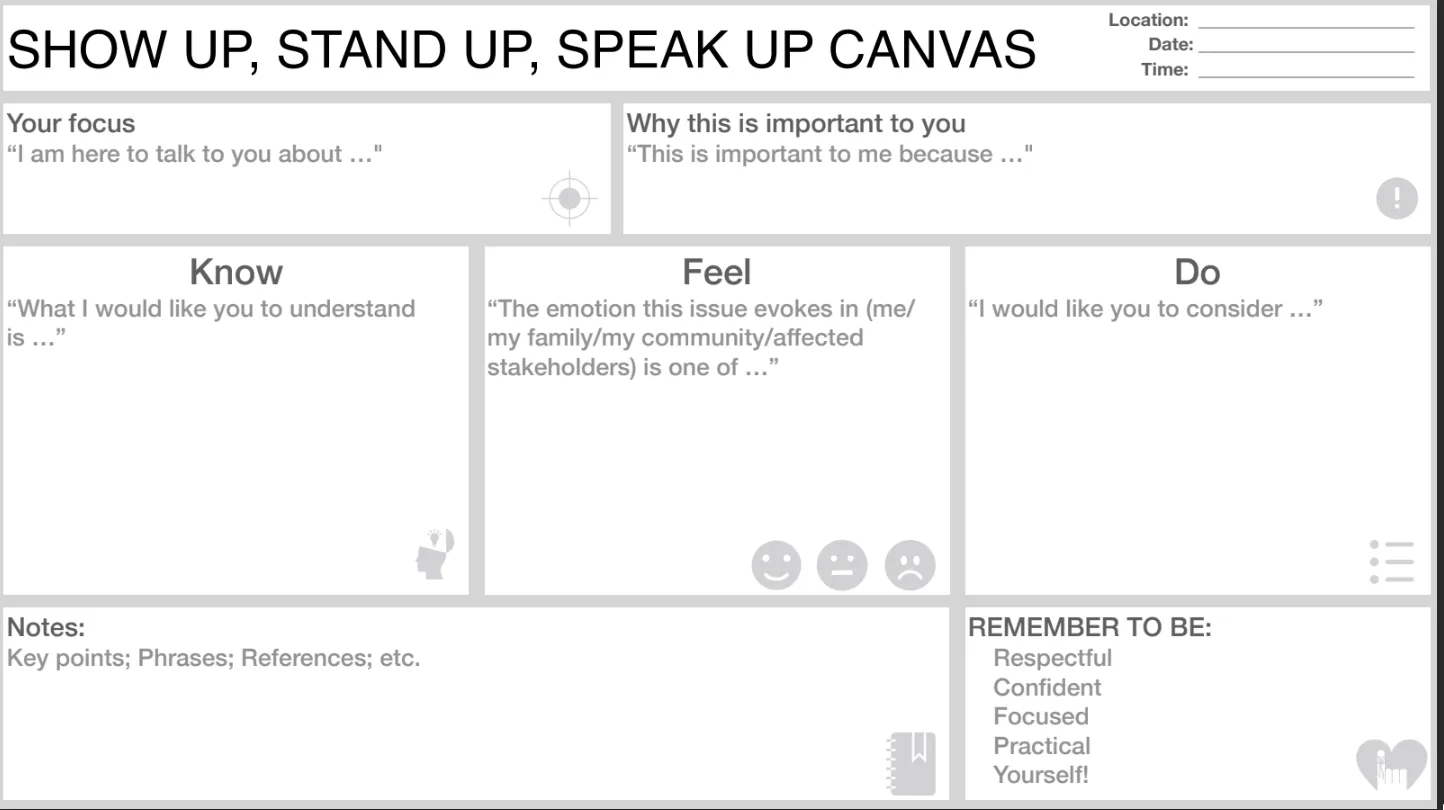

What rights do your students have to speak up about these issues?

An A.C.L.U. “toolkit” for students called “ Right to Learn: Your Guide to Combatting Classroom Censorship ” states: “All young people have a First Amendment right to learn free from censorship or discrimination,” including a “right to read, learn and share ideas free from viewpoint-based censorship.” And, indeed, a famous 1969 Supreme Court decision declared that neither students nor teachers “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

But in 1988, the Supreme Court placed a limit on the types of speech protected by the First Amendment in a school setting. As this site summarizes , “The case, Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, began with student journalists looking to push the envelope with articles they believed their classmates would relate to. And it ended with the Supreme Court creating a new rule on student speech.” Though courts since then have made it clear that school officials do not have an unlimited license to censor, the Hazelwood decision was, according to the Poynter Institute, “ a giant step back for student press and speech rights. ”

Recently, for instance, a Nebraska school shut down its student newspaper rather than allow it to focus on L.G.B.T.Q. issues. The Times article puts that news into context:

The shuttering of the paper was the latest instance of students contending with school officials seeking to prevent the distribution of yearbooks or the publication of articles , particularly in cases dealing with L.G.B.T.Q. issues. In May, school officials in Longwood, Fla., ordered stickers to be placed over a photo spread in the Lyman High School yearbook showing students protesting a new state law that prohibits classroom instruction and discussion about sexual orientation and gender identity in some elementary school grades. Last August, school officials in Arkansas removed a two-page year-in-review spread from one high school’s yearbook that mentioned the pandemic, the murder of George Floyd and the 2020 election. “It’s something we’re definitely seeing more of,” Mr. Hiestand said.

But, as the article points out, at least 16 states have “New Voices” laws intended to safeguard school publications from interference and counteract the Hazelwood decision. To learn more, visit the Student Press Law Center’s section about these laws .

After the 2018 Parkland shootings, planned student walkouts to protest gun violence again raised questions of students’ First Amendment rights. This A.C.L.U. guide addresses the question, “Do I have First Amendment rights in school?” in that context, pointing out that students have the rights to speak out, hand out fliers and wear expressive clothing “as long as you don’t disrupt the functioning of the school or violate the school’s content-neutral policies.”

Invite your students to investigate what laws and guidelines determine student speech and expression in their school. Do they feel they can comfortably speak their minds in their classes, no matter what their political viewpoints? Why or why not? Has their school ever faced a situation in which students were prevented by school administrators from saying, doing or writing something? Do your students think the move was necessary to protect students — or did it cross the line into stifling free speech?

What is published in their school newspaper and yearbook? How much freedom do students journalists who work on those publications have? Is your school in a state that has adopted a “New Voices” law? If so, what are the implications for student publications?

You might also ask them to think about broader questions like, Why would a school want to control student speech? When, if at all, do they think that is appropriate? For instance, are there any topics that should be off limits in school newspapers? Should these publications be allowed to criticize the school administration, investigate teachers or write about sensitive subjects like teenage sexuality and school shootings? Why or why not?

To help with some of these questions, we have a 2018 lesson plan that links to many resources:

Lesson: The Power to Change the World: A Teaching Unit on Student Activism in History and Today

We also have several related Student Opinion forums to which students might contribute — or read what other students have to say:

Should Schools Be Allowed to Censor Student Newspapers?

What Do You Wish Lawmakers Knew About How Anti-L.G.B.T.Q. Legislation Affects Teenagers?

How Comfortably Can You Speak Your Mind at School?

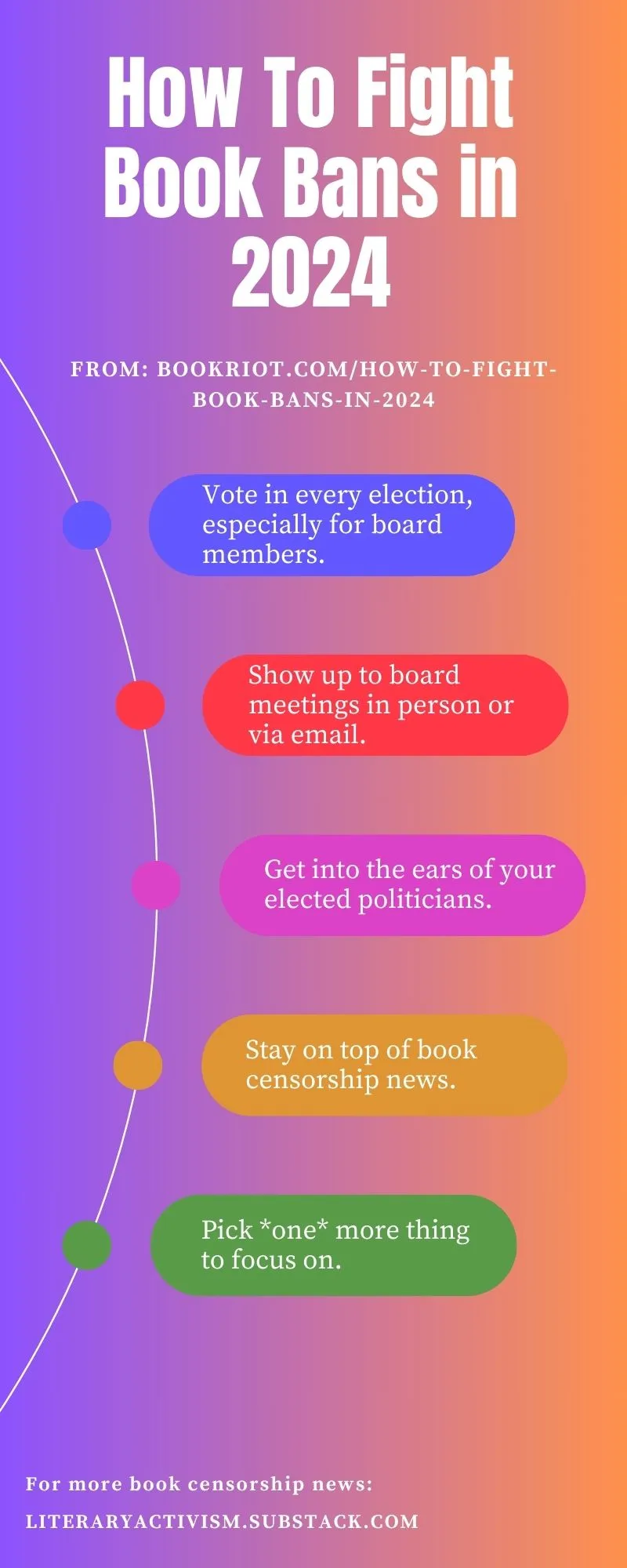

What can young people do?

In 2021, Edha Gupta and Christina Ellis, two high school seniors in York County, Pa., were furious when they read in a local paper that their teachers had been effectively banned from using hundreds of books, documentary films and articles in their classrooms. This article describes what they did in response. In August 2022, the two gave a TEDx talk called “ How a Book Ban Helped Us Find Our Voice .”

Looking for another first-person account from a teenager? This article from School Library Journal, “ Uniting Against Censorship: A First-Person Account from Banned Books Week Youth Honorary Chair .”

If your students are interested in raising their voices on any of the issues they’ve investigated thus far, they can learn from students like these, or find out more from the following resources:

American Library Association: Unite Against Book Bans

We Need Diverse Books: How to Support Diverse Books During a Book Ban

A.C.L.U.: Right to Learn: Your Guide to Combatting Classroom Censorship

Pen America: The organization is keeping a regularly-updated Google Doc called “ The PEN America Index of Educational Gag Orders. ”

Find more lesson plans and teaching ideas here.

Katherine Schulten has been a Learning Network editor since 2006. Before that, she spent 19 years in New York City public schools as an English teacher, school-newspaper adviser and literacy coach. More about Katherine Schulten

Banned Books: Freedom to Read

- Read Banned Books

- Banned Books Week

Most Challenged Books of 2022

- Data & Reports

- Get Involved

- Public Library Access

- USC Libraries Help

- Top 13 Most Challenged Books of 2022 (American Library Association) This page lists the 13 most challenged books of 2023 and what each book was challenged for. ALA documented 1,269 demands to censor library books and resources in 2022, the highest number of attempted book bans since ALA began compiling data about censorship in libraries more than 20 years ago.

- Top 100 Most Banned and Challenged Books: 2010-2019 (American Library Association) List of the most banned and challenged books from 2010-2019 compiled by the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom.

- << Previous: Banned Books Week

- Next: Data & Reports >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 2:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/bannedbooks

Banned Books 2023: Let Freedom Read: Home

Celebrate Banned Books Week - October 1-7, 2023

Why Banned Books Week?

- Statement from the American Library Association

- Definitions

Banned Books Week is an annual event celebrating the freedom to read. Highlighting the value of free and open access to information, Banned Books Week brings together the entire book community –- librarians, booksellers, publishers, journalists, teachers, and readers of all types –- in shared support of the freedom to seek, to publish, to read, and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular.

By focusing on efforts across the country to remove or restrict access to books, Banned Books Week draws national attention to the harms of censorship. The books featured during Banned Books Week have all been targeted for removal or restrictions in libraries and schools. While books have been and continue to be banned, part of the Banned Books Week celebration is the fact that, in a majority of cases, the books have remained available. This happens only thanks to the efforts of librarians, teachers, students, and community members who stand up and speak out for the freedom to read. –- Banned Books Week Q&A

Book Challenge vs. Book Ban

An attempt to remove or restrict materials, based upon the objections of a person or group.

Challenges do not simply involve a person expressing a point of view; rather, they are an attempt to remove material from the curriculum or library, thereby restricting the access of others.

A book banning is the actual removal of those materials .

A change in the access status of material, based on the content of the work and made by a governing authority or its representatives. Such changes include exclusion, restriction, removal, or age/grade level changes.

Intellectual Freedom

The right of every individual to both seek and receive information from all points of view without restriction. It provides for free access to all expressions of ideas through which any and all sides of a question, cause or movement may be explored.

Read Banned Books @ St. Kate's Library

My Sister's Keeper

The Qur'an [al-Quran al-hakim]

The Hunger Games

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

In the Night Kitchen

Intellectual Freedom Issues in School Libraries

Intellectual Freedom Manual

Intellectual Freedom Stories from a Shifting Landscape

It's Perfectly Normal

The Kite Runner

Looking for Alaska

Maus I: a Survivor's Tale

Me and Earl and the dying girl

Melissa (formerly Published As GEORGE)

The Holy Bible : Revised Standard Version, Catholic edition

Nasreen's Secret School

Of Mice and Men

Out of Darkness

The Perks of Being a Wallflower

Skippyjon Jones

Slaughterhouse-Five

Something Happened in Our Town

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You

This book is gay

To Kill a Mockingbird

A Universal History of the Destruction of Books

Captain Underpants and the Attack of the Talking Toilets

The 1619 Project

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian Collector's Edition

All American Boys

All Boys Aren't Blue

Almost Perfect

And Tango Makes Three

The Annotated Huckleberry Finn

Banned books: defending our freedom to read

Beyond Banned Books

Beyond Magenta

The Bluest Eye

Book Banning in 21St-Century America

Books under Fire

Brave New World

100 Banned Books

A Court of Mist and Fury

The Color Purple

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

Dear Martin

A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo

Dreaming in Cuban

Felix Ever After

Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl

Gender Queer: a Memoir

The Glass Castle

His Dark Materials: the Golden Compass (Book 1)

The Handmaid's Tale

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone

The Hate U Give

A History of ALA Policy on Intellectual Freedom

A year in review.

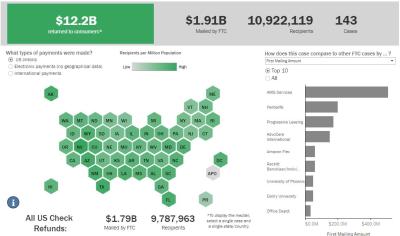

- More Than 4,000 Unique Titles Challenged: ALA Releases 2023 Censorship Data From Unite Against Book Bans, March 14, 2024

- Spineless Shelves: Two Years of Book Banning PEN America - December 2023

- I Made the Most Banned Book in America The Nib - September 1, 2023

- State Laws Supercharge Book Suppression in Schools PEN America - April 20, 2023

- American Library Association releases preliminary data on 2022 book bans ALANews & Press Center - Sept. 16, 2022

- Banned in the USA: The Growing Movement to Censor Books in Schools PEN America

- Book banning in U.S. schools has reached an all-time high: What this means, and how we got here GRID - Aug. 27, 2022

Top 13 Most Challenged Books of 2022

Book Bans in the News

- Red states threaten librarians with prison — as blue states work to protect them Washington Post, 4/16/24

- Florida law led school district to pull 1,600 books — including dictionaries Washington Post, 1/14/24

- The Post reviewed 1,000 school book challenges. Here’s what we found. Washington Post, 12/23/23

- Publishing industry heavy-hitters sue Iowa over state's new school book-banning law Washington Post, 11/30/23

- 'To Be Destroyed': Documentary examines Rapid City's attempted book ban Rapid City Journal, 10/26/23

- North Carolina Retracts Ban on Banned Books Week The Guardian - September 30, 2023

- Senate Hearing Discusses Book Bans The Hill - September 12, 2023

- Public Libraries are the Latest Front in Culture War Battle Over Books Washington Post - July 25, 2023

- Florida Readers Push Back Against Book Bans WUSF Public Media - June 10, 2023

Guide Feedback

- Guide feedback We welcome your feedback! Use this form to suggest changes/additions to this guide.

Censorship and Book Challenges by the Numbers

- Who Challenges

- For What Reason(s)

- Mapping Censorship

From the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom

- During the first half of the 2022-23 school year PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans lists 1,477 instances of individual books banned, affecting 874 unique titles , an increase of 28 percent compared to the prior six months, January – June 2022. That is more instances of book banning than recorded in either the first or second half of the 2021-22 school year. Over this six-month timeline, the total instances of book bans affected over 800 titles; this equates to over 100 titles removed from student access each month.

- Overwhelmingly, book banners continue to target stories by and about people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals. In this six-month period, 30% of the unique titles banned are books about race, racism, or feature characters of color. Meanwhile, 26% of unique titles banned have LGBTQ+ characters or themes

- The full impact of the book ban movement is greater than can be counted, as “wholesale bans” are restricting access to untold numbers of books in classrooms and school libraries. This school year, numerous states enacted “wholesale bans” in which entire classrooms and school libraries have been suspended, closed, or emptied of books, either permanently or temporarily. This is largely because teachers and librarians in several states have been directed to catalog entire collections for public scrutiny within short timeframes, under threat of punishment from new, vague laws. These “wholesale bans,” have involved the culling of books that were previously available to students, in ways that are impossible to track or quantify.

The most common themes in book challenges include:

- Books that have to do with LGBTQ topics or characters.

- Books that have to do with sex, abortion, teen pregnancy or puberty.

- Books that have to do with race and racism, or that center on protagonists of color.

- Books that have to do with history, specifically that of Black people.

- EveryLibrary Institute Dr. Tasslyn Magnusson is an independent researcher focused on the networks, organizations, and individual actors who are leading book banning and book challenge efforts in our nation's school libraries and public libraries. Dr. Magnusson's spreadsheet of book bans and challenges has been available online since October 2021 to aid library organizations, library staff, education stakeholders, and concerned parents. Her findings have helped numerous school libraries and public libraries.

- Youth Censorship Database The National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) database of K-12 student censorship incidents includes book challenges in schools and libraries, as well as censorship of student art, journalism, and other types of student expression in schools. The map can be filtered based on Reason, State, and other options, along with additional information and links to incident reports.

Freedom to Read Statement

Seventy years ago, leaders from across the literary world joined together in writing to condemn attacks on free expression. The statement at the heart of that endeavor, the Freedom to Read Statement ,was authored by the American Library Association and Association of American Publishers over a period of several days. It begins with this timeless observation:

The freedom to read is essential to our democracy. It is continuously under attack.

Read the full Freedom to Read Statement.

From Unite Against Book Bans, 2023

The Fiery History of Banned Books Week

Advocacy and Activism around Banned Books

Whether by providing legal support, educational resources for parents, teachers, and librarians, or opportunities to organize on the grassroots level, there are many organizations which fight against efforts to ban books in school libraries and beyond, and many more which fight censorship more broadly.

Learn more about some of these organizations, and/or get involved, below:

- How to Fight Book Bans: A Tip Sheet for Students From PEN America

- American Library Association, Fight Censorship