Search form

Engaging communities. Influencing change.

What does representation mean to me.

Representation Matters!

This year, we celebrate Women’s History Month 2022 with a familiar concept for many, but let’s look closely to examine why Representation Matters and what it means for NIH. Allow us to engage, educate, and inspire while acknowledging the power of identity, inclusion, and belonging. Everyone should experience a sense of belonging in the workplace regardless of color, ability, race, national origin, sex, age, or any social construct. We aim to create and nurture belongingness at NIH. Join us as we explore the impact of representation on women in our community and beyond.

Tara Schwetz, Ph.D.

Acting principal deputy director national institutes of health, representation is critical..

Representation is critical. It can serve as a means of support and validation, it illustrates what is possible, and it helps to break down stereotypes. However, representation is only one milestone on the road to equity, and it must be prioritized to move toward the ultimate destination.

Early in my career at NIH, I interacted with a female IC leader who was unapologetically herself. She was a straight shooter, honest and unafraid to speak her mind, not to mention a fabulous mentor who lifted me up in the best way. While I had seen men in equivalent roles take a similar approach, I had never noticed a female leader doing so. I found this incredibly refreshing, eye-opening, and inspiring.

Observing women with significant authority.

During my 15 plus years at NIH, I have interacted with exceptional individuals who have helped shape my career and motivated me to strive for leadership roles across the agency. For me, there is warmth and a sense of belonging when I can attend meetings and see other women, particularly women of color, leading them, contributing to them, and helping to shape the outcomes that will inevitably follow. I clearly recall a day early in my tenure at NIH when I went to a symposium at Natcher Auditorium and watched as several directors and deputy directors of the institutes and centers took their places at the front of the room. At the time, it was primarily men walking down the aisle, but I noticed the women who were interspersed among them. Despite being few in number, it was clear each of these women had significant authority and decision-making roles, spoke to their science, and were well received by the audience. That picture has remained in my head and given me a vision and understanding of what could be possible—a seat in the front row.

Courtney F. Aklin, Ph.D.

Acting associate deputy director national institutes of health.

Lisa L. Cunningham, Ph.D.

Scientific director national institute on deafness and other communication disorders (nidcd), empowering through representation..

Most of my scientific advisors and career advocates have been men, which illustrates that you don’t have to be a woman to support and encourage women; in fact, it’s critical that we don’t exclude half the population as potential career advocates and mentors. That said, there is clearly a special relationship when someone personally understands our experiences and makes a conscious effort to support us. Throughout each stage of my career, I have been lucky enough to have peer groups of strong, smart, accomplished, ambitious, infinitely capable women. When I was a post-doctoral fellow, there were five women graduate students and post-docs in the lab, all of whom are full professors now. The five of us ate lunch together most days—we shared experiences, complained together, and encouraged each other. When I started my first independent lab, I again had the benefit of being part of a large group of approximately 12 women, mostly junior faculty members. We met regularly and exchanged victories and injustices, providing insight and support for one another. It was empowering to have this community of women who were at a similar career stage to me, figuring out how to make it work as scientists and have lives beyond our jobs. When I arrived at NIH, I was again surrounded by incredibly capable women scientists, some of whom were my own mentees. Last year I became a Scientific Director, and the other women SDs reached out to offer support, encouragement, and the benefit of their experiences. I cannot overemphasize the importance of women peer mentors throughout my career. It takes a real generosity of spirit for someone to go beyond what is required for their own success and offer support and community to those around them, but at times, this has been the critical element that kept me moving forward. I am grateful for all the very talented women who have shown me this generosity.

Because of them, we can.

I am fortunate—I started life with a wonderful female role model, my mother. She was an African American physician in private practice long before there were HMOs and hospital practices. My medical career benefited from the example she set. Nonetheless, as my career evolved, I found myself to be the one expected in many settings to represent my race and sex. Knowing that my mother had succeeded was an inspiration. I hope the current generation of aspiring physician scientists appreciate the doors that were opened by our predecessors.

Marie A. Bernard, M.D.

Chief officer scientific workforce diversity.

Jennifer Cyriaque-Webster, D.D.S., Ph.D

Deputy director national institute of dental and craniofacial research (nidcr), if you see her, you can be her..

In my life, I have been a beneficiary of representation on multiple levels and have been a representative for some in the pathway. In my mind, representation equals can do. A picture or visual is worth a thousand words. However, when it comes to empowerment, confidence, and belief that something is achievable, the recognition that someone that you share characteristics with has accomplished the potential desired goal is invaluable. To borrow from the vernacular: “if you can see her, you can be her.”

A kaleidescope of experiences.

This term encompasses a kaleidoscope of experiences for me:

The bidirectional benefits of mentoring and being mentored; a balance between accomplishing visions and dealing with reality; knowing that becoming the person I was meant to be required being purposeful, intentional, and resilient but always able to embrace serendipity and the magic that intersections of ideas bring; loving life while learning to live it fully; the cumulative effects of a journey filled with laughter to signify my joy in existence and tears to unite me with those with broken hearts.

Rena D’Souza, D.D.S., MS, Ph.D

Director nidcr.

Tonia Awoniyi, J.D.

Director nih ethics office, paying it forward..

I cannot think of just one woman who was a great role model. For as long as I can remember, a woman has always encouraged and helped me be my best. My mother, aunts, grandmothers, teachers, friends, classmates, sorority sisters, colleagues, and supervisors all played a role in my professional journey and guided me to where I am today. I try to emulate all my role models and help pave the road for someone else. As Director of the NIH Ethics Office, I intend to encourage the next generation of leaders.

Female mentorship is key.

When I started at NIH in 1991, my first impression was that the overwhelming majority of the leadership I saw as I walked down the halls was composed of men. As the years went by, I met more and more women in leadership positions. While I found that both men and women were supportive of my career, I discovered several key women who saw something in me and who wanted me to succeed. Through these female mentors, I was presented with chance opportunities throughout my NIH career to step up and work hard at new positions. What I learned was that successful leaders sincerely look to help their staff excel and give them the tools to do their jobs. I believe it is now my responsibility as a female and minority leader to also nurture other NIH employees in expanding their opportunities, while celebrating their diverse backgrounds, to help them reach their career goals. Certainly, it was this mindset of my mentors and leaders that ensured I was prepared to get to the next level. As I look back on my career, to quote Louis Pasteur, it is clear that “chance favors only the prepared mind.”

Olga Acosta

Executive officer division of management services, national institute of nursing research (ninr).

Why does representation matter to you? Join the conversation on our social media channels this month. Tell us what posts resonate the most with you or any additional content you’d like to see. Feel free to drop us a DM, too!

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

representation

Definition of representation

Examples of representation in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'representation.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

15th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1

Phrases Containing representation

- proportional representation

- self - representation

Dictionary Entries Near representation

representant

representationalism

Cite this Entry

“Representation.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/representation. Accessed 31 May. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of representation, legal definition, legal definition of representation, more from merriam-webster on representation.

Thesaurus: All synonyms and antonyms for representation

Nglish: Translation of representation for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of representation for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about representation

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - may 31, pilfer: how to play and win, 9 superb owl words, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, your favorite band is in the dictionary, games & quizzes.

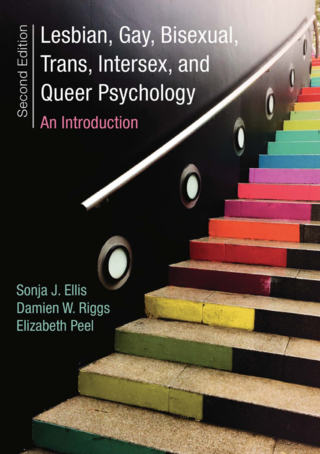

Transgender

The importance of representation in psychology, the inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer people..

Posted November 3, 2019

This blog post was written by Damien W. Riggs, Elizabeth Peel and Sonja Ellis.

For over a century, the psy disciplines have sought to grapple with the topics of sex, gender and sexuality diversity. Starting with the work of Freud , and continuing through to the addition of sex, gender, and sexuality diversity into various versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, the psy disciplines have, for better or worse, had a prominent voice in how lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender , intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) people are understood.

In psychology specifically, early research largely adopted a pathologizing approach, seeking to demonstrate familial ‘causes’ of homosexuality or gender diversity. Whilst there are notable exceptions to this, such as in the work of Evelyn Hooker and June Hopkins, psychology in the mid 20th Century was a breeding ground for theories that were either less than positive or entirely pathologizing of lesbians and gay men in particular. In this same period of time, psychologists played an increasing role in gatekeeping transgender people’s access to services.

In terms of representation, then, psychology’s early forays into the lives of LGBTIQ people were largely negative and served to enshrine within the public imaginary stereotypes about LGBTIQ people that continue to this day. These include assumptions of promiscuity amongst gay men and bisexual people, the view that assigned sex determines gender, the belief that gender and sexuality diversity can be ‘corrected’ through therapy , and the assumption that homosexuality constitutes a mental disorder.

From the 1980s onwards, however, a new stream of psychology developed, one that took as its central aim the affirmation of LGBTIQ people’s lives. Often (though not always) led by LGBTIQ researchers and clinicians themselves, this affirming strand of psychology challenged the stereotypes outlined above, and advocated for change both within the discipline and within society more broadly. In this same time period, psychological associations formed their own groups, networks and formal structures that aimed to recognize the study of LGBTIQ people’s lives as a distinct field of psychology.

In many ways, the second edition of our textbook Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Intersex and Queer Psychology: An Introduction signals a significant moment in the trajectory of this field of psychology. It serves to highlight how much has been gained since the initial developments of affirming psychological approaches to LGBTIQ people’s lives. It also highlights how much further we have to go, especially with regard to inclusive and affirming representations of the lives of people born with intersex variations, people who have non-binary genders, and queer people.

Central to our book is a focus on representation: how LGBTIQ people’s lives are represented within psychology, how psychology can play an important advocacy role in terms of producing positive and affirming representations of LGBTIQ people, and how psychology itself as a discipline understands its relationship to the field of LGBTIQ psychology. Representation, as we argue, is not simply a matter of more. Rather, it is a matter of better, more and critical representations of LGBTIQ people: representations that challenge the idea that there is one singular LGBTIQ narrative, representations that recognize diversity across the lives of LGBTIQ people, and representations that hold to account the discipline of psychology for its historical (and in some cases ongoing) less than positive representations.

Importantly, and as we suggested in the first edition of our book, a heterosexual and/or cisgender psychologist or researcher can be an ‘LGBTIQ psychologist’. Whilst, as we suggested above, the field of LGBTIQ has largely been led by LGBTIQ people, this does not limit the field to any certain group, and certainly heterosexual and/or cisgender people have made vital contributions to the psychological study of LGBTIQ people’s lives. Indeed, we would suggest that for representation within psychology to be truly inclusive of LGBTIQ people, it requires the voices of all.

In conclusion, we have come a long way within the psy disciplines, and psychology in particular, in terms of the representation of LGBTIQ people. We have, to differing extents, come to understand the harms that have been done, and have sought to be accountable for this. We also know that in some contexts harms continue, and it is the role of the discipline to continue to speak out when injustices occur, particularly those that occur in the name of psychology. As an evidence based profession, we have a strong base from which to counter negative representations, and instead to produce and advocate for representations that take as their central premise the importance of a just world, in which LGBTIQ people have equitable access to wellbeing.

Damien Riggs, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at Flinders University and an Australian Research Council Future Fellow.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

representation

[ rep-ri-zen- tey -sh uh n , -z uh n- ]

- the act of representing.

- the state of being represented.

- the expression or designation by some term, character, symbol, or the like.

- action or speech on behalf of a person, group, business house, state, or the like by an agent, deputy, or representative.

to demand representation on a board of directors.

- Government. the state, fact, or right of being represented by delegates having a voice in legislation or government.

- the body or number of representatives, as of a constituency.

- the act of speaking or negotiating on behalf of a state.

- an utterance on behalf of a state.

- presentation to the mind, as of an idea or image.

- a mental image or idea so presented; concept.

- the act of portrayal, picturing, or other rendering in visible form.

- a picture, figure, statue, etc.

- the production or a performance of a play or the like, as on the stage.

- Often representations. a description or statement, as of things true or alleged.

- a statement of facts, reasons, etc., made in appealing or protesting; a protest or remonstrance.

a representation of authority.

/ ˌrɛprɪzɛnˈteɪʃən /

- the act or an instance of representing or the state of being represented

- anything that represents, such as a verbal or pictorial portrait

- anything that is represented, such as an image brought clearly to mind

- the principle by which delegates act for a constituency

- a body of representatives

- contract law a statement of fact made by one party to induce another to enter into a contract

- an instance of acting for another, on his authority, in a particular capacity, such as executor or administrator

- a dramatic production or performance

- often plural a statement of facts, true or alleged, esp one set forth by way of remonstrance or expostulation

phonetic representation

Discover More

Other words from.

- nonrep·re·sen·tation noun

- over·repre·sen·tation noun

- prerep·re·sen·tation noun

- self-repre·sen·tation noun

- under·repre·sen·tation noun

Word History and Origins

Origin of representation 1

Example Sentences

It was a metaphorical statement of giving and withdrawing consent for a show rooted in a literal representation of Coel being assaulted.

The mathematically manipulated results are passed on and augmented through the stages, finally producing an integrated representation of a face.

I hope this list—a representation of the most consequential changes taking places in our world—is similarly useful for you.

“Given the moment we are in, I can only hope our institutions really understand what this failure of representation means to our city,” he said.

The voters don’t want to have an elected city attorney on the, and representation said, that’s fine.

With all that said, representation of each of these respective communities has increased in the new Congress.

As this excellent piece in Mother Jones describes, however, Holsey had outrageously poor representation during his trial.

During that time days, Livvix went through court hearings without legal representation.

What do you think prompted the change in comic book representation of LGBTQ characters?

Barbie is an unrealistic, unhealthy, insulting representation of female appearance.

With less intelligent children traces of this tendency to take pictorial representation for reality may appear as late as four.

As observation widens and grows finer, the first bald representation becomes fuller and more life-like.

The child now aims at constructing a particular linear representation, that of a man, a horse, or what not.

He had heard it hinted that allowing the colonies representation in Parliament would be a simple plan for making taxes legal.

But sufficient can be discerned for the grasping of the idea, which seems to be a representation of the Nativity.

Related Words

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of representation noun from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

representation

- the negative representation of single mothers in the media

- The snake swallowing its tail is a representation of infinity.

- The film offers a realistic representation of life in rural Spain.

- There are many ways of generating a two-dimensional representation of an object.

- a book showing graphic representations of the periodic table

- a realistic cinematic representation of the Depression

- artistic representations of the parent/child relationship

- contemporary media representations of youth

- the written representation of a spoken text

- a form of representation

- a means of representation

Take your English to the next level

The Oxford Learner’s Thesaurus explains the difference between groups of similar words. Try it for free as part of the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary app

In theatre, I have seen many brilliant examples of representation in theatre, and can understand the importance of it all. Look at the recent Gender swapped production of Company for example. With Amy becoming Jamie, a gay couple were given a spotlight in a hugely popular show, and these characters quickly became a hit with the audience. Those in the LGBT Community may have been able to see themselves represented in the characters of Jamie and Paul.

In terms of the representation of colour and ethnicity, we sadly have to talk about a of negative points. With Aladdin, Motown and Dreamgirls all closing in the West end in the last year, the number of shows with a largely coloured cast has dramatically dropped. I have seen a number of jokey comments online about the upcoming production of The Prince Of Egypt being needed to raise west end diversity. When Big the musical announced it’s cast, many questions were asked when it was revealed that it was a completely white cast. For a show set in New York, perhaps one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the world, they could have been much more inclusive in it’s casting. It’s a touchy subject for many.

Something that I have noticed recently when seeing shows is a change in the look of the cast in general. Have you noticed that not everyone is slim anymore, not everyone has that ideal body shape that instagram and other social media tries to drill into us. And I think that it is a wonderful thing. I’m not little, I don’t have that perfect body shape, but to see performers with a body shape like me on stage is incredibly empowering. I see someone bigger dancing, performing and amazing the audience and think ‘wow look at them, they are just like me’. That is why representation matters.

What do you think? Why does representation on stage matter to you?

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Definition of 'representation'

- representation

representation in British English

Representation in american english, examples of 'representation' in a sentence representation, cobuild collocations representation, trends of representation.

View usage for: All Years Last 10 years Last 50 years Last 100 years Last 300 years

In other languages representation

- American English : representation / rɛprɪzɛnˈteɪʃən /

- Brazilian Portuguese : representação

- Chinese : 代表

- European Spanish : representación

- French : représentation

- German : Vertretung

- Italian : rappresentanza

- Japanese : 代表

- Korean : 대표

- European Portuguese : representação

- Latin American Spanish : representación

- Thai : การมีตัวแทน

Browse alphabetically representation

- represent value

- representamen

- representant

- representation of reality

- representational

- representational painting

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'R'

Related terms of representation

- ensure representation

- equal representation

- exact representation

- fair representation

- false representation

- View more related words

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

What does Representation mean to you?

The Diatribe teaching artists talk about representation and what it means to them. What does representation mean to you?

Related Lessons

Teamwork: Dealing with Disagreements

The creators of Minecraft Education Edition discuss the rules they use to work as a team.

How Teamwork Works

Join the creators of Minecraft Education Edition to get in inside look at how their teamwork works.

What does Normal mean?

Diatribe teaching artists talk about what "normal" means to them.

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

descriptions

See all related overviews in Oxford Reference »

More Like This

Show all results sharing this subject:

representation

Quick reference.

[Latin repraesentare ‘to make present or manifest’]

1. Depicting or ‘making present’ something which is absent (e.g. people, places, events, or abstractions) in a different form: as in paintings, photographs, films, or language, rather than as a replica . See also description; compare absent presence.

2. The function of a sign or symbol of ‘standing for’ that to which it refers (its referent).

3. The various processes of production involved in generating representational texts in any medium, including the mass media (e.g. the filming, editing, and broadcasting of a television documentary). Such framings of the concept privilege authorial intention. See also auteur theory; authorial determinism; sender-oriented communication.

4. A text (in any medium) which is the product of such processes, usually regarded as amenable to textual analysis (‘a representation’).

5. What is explicitly or literally described, depicted, or denoted in a sign, text, or discourse in any medium as distinct from its symbolic meaning, metaphoric meaning, or connotations: its manifest referential content, as in ‘a representation of…’ See also mimesis; naturalism; referentiality.

6. How (in what ways) something is depicted. However ‘realistic’ texts may seem to be, they involve some form of transformation. Representations are unavoidably selective (none can ever ‘show the whole picture’), and within a limited frame, some things are foregrounded and others backgrounded: see also framing; generic representation; selective representation; stylization. In factual genres in the mass media, critics understandably focus on issues such as truth, accuracy, bias, and distortion ( see also reflectionism), or on whose realities are being represented and whose are being denied. See also dominant ideology; manipulative model; stereotyping; symbolic erasure.

7. The relation of a sign or text in any medium to its referent. In reflectionist framings, the transparent re- presentation, reflection, recording, transcription, or reproduction of a pre-existing reality ( see also imaginary signifier; mimesis; realism). In constructionist framings, the transformation of particular social realities, subjectivities, or identities in processes which are ostensibly merely re- presentations ( see also constitutive models; interpellation; reality construction). Some postmodern theorists avoid the term representation completely because the epistemological assumptions of realism seem to be embedded within it.

8. A cycle of processes of textual and meaning production and reception situated in a particular sociohistorical context ( see also circuit of communication; circuit of culture). This includes the active processes in which audiences engage in the interpretation of texts ( see also active audience theory; beholder's share; picture perception). Semiotics highlights representational codes which need to be decoded ( see also encoding/decoding model; photographic codes; pictorial codes; realism), and related to a relevant context ( see also Jakobson's model).

9. (narratology) Showing as distinct from telling (narration).

10. (mental representation) The process and product of encoding perceptual experience in the mind: see dual coding theory; gestalt laws; mental representation; perceptual codes; selective perception; selective retention.

11. A relationship in which one person (a representative) acting on behalf of another (as in law), or a political principle in which one person acts, in some sense, on behalf of a group of people, normally having been chosen by them to do so (as in representative democracies).

From: representation in A Dictionary of Media and Communication »

Subjects: Media studies

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries, representation, problems.

View all reference entries »

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'representation' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 01 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.150.64]

- 185.80.150.64

Character limit 500 /500

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Political Representation

The concept of political representation is misleadingly simple: everyone seems to know what it is, yet few can agree on any particular definition. In fact, there is an extensive literature that offers many different definitions of this elusive concept. [Classic treatments of the concept of political representations within this literature include Pennock and Chapman 1968; Pitkin, 1967 and Schwartz, 1988.] Hanna Pitkin (1967) provides, perhaps, one of the most straightforward definitions: to represent is simply to “make present again.” On this definition, political representation is the activity of making citizens’ voices, opinions, and perspectives “present” in public policy making processes. Political representation occurs when political actors speak, advocate, symbolize, and act on the behalf of others in the political arena. In short, political representation is a kind of political assistance. This seemingly straightforward definition, however, is not adequate as it stands. For it leaves the concept of political representation underspecified. Indeed, as we will see, the concept of political representation has multiple and competing dimensions: our common understanding of political representation is one that contains different, and conflicting, conceptions of how political representatives should represent and so holds representatives to standards that are mutually incompatible. In leaving these dimensions underspecified, this definition fails to capture this paradoxical character of the concept.

This encyclopedia entry has three main goals. The first is to provide a general overview of the meaning of political representation, identifying the key components of this concept. The second is to highlight several important advances that have been made by the contemporary literature on political representation. These advances point to new forms of political representation, ones that are not limited to the relationship between formal representatives and their constituents. The third goal is to reveal several persistent problems with theories of political representation and thereby to propose some future areas of research.

1.1 Delegate vs. Trustee

1.2 pitkin’s four views of representation, 2. changing political realities and changing concepts of political representation, 3. contemporary advances, 4. future areas of study, a. general discussions of representation, b. arguments against representation, c. non-electoral forms of representation, d. representation and electoral design, e. representation and accountability, f. descriptive representation, other internet resources, related entries, 1. key components of political representation.

Political representation, on almost any account, will exhibit the following five components:

- some party that is representing (the representative, an organization, movement, state agency, etc.);

- some party that is being represented (the constituents, the clients, etc.);

- something that is being represented (opinions, perspectives, interests, discourses, etc.); and

- a setting within which the activity of representation is taking place (the political context).

- something that is being left out (the opinions, interests, and perspectives not voiced).

Theories of political representation often begin by specifying the terms for the first four components. For instance, democratic theorists often limit the types of representatives being discussed to formal representatives — that is, to representatives who hold elected offices. One reason that the concept of representation remains elusive is that theories of representation often apply only to particular kinds of political actors within a particular context. How individuals represent an electoral district is treated as distinct from how social movements, judicial bodies, or informal organizations represent. Consequently, it is unclear how different forms of representation relate to each other. Andrew Rehfeld (2006) has offered a general theory of representation which simply identifies representation by reference to a relevant audience accepting a person as its representative. One consequence of Rehfeld’s general approach to representation is that it allows for undemocratic cases of representation.

However, Rehfeld’s general theory of representation does not specify what representative do or should do in order to be recognized as a representative. And what exactly representatives do has been a hotly contested issue. In particular, a controversy has raged over whether representatives should act as delegates or trustees .

Historically, the theoretical literature on political representation has focused on whether representatives should act as delegates or as trustees . Representatives who are delegates simply follow the expressed preferences of their constituents. James Madison (1787–8) describes representative government as “the delegation of the government...to a small number of citizens elected by the rest.” Madison recognized that “Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm.” Consequently, Madison suggests having a diverse and large population as a way to decrease the problems with bad representation. In other words, the preferences of the represented can partially safeguard against the problems of faction.

In contrast, trustees are representatives who follow their own understanding of the best action to pursue. Edmund Burke (1790) is famous for arguing that

Parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests, which interest each must maintain, as an agent and advocate, against other agents and advocates; but Parliament is a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole… You choose a member, indeed; but when you have chosen him he is not a member of Bristol, but he is a member of Parliament (115).

The delegate and the trustee conception of political representation place competing and contradictory demands on the behavior of representatives. [For a discussion of the similarities and differences between Madison’s and Burke’s conception of representation, see Pitkin 1967, 191–192.] Delegate conceptions of representation require representatives to follow their constituents’ preferences, while trustee conceptions require representatives to follow their own judgment about the proper course of action. Any adequate theory of representation must grapple with these contradictory demands.

Famously, Hanna Pitkin argues that theorists should not try to reconcile the paradoxical nature of the concept of representation. Rather, they should aim to preserve this paradox by recommending that citizens safeguard the autonomy of both the representative and of those being represented. The autonomy of the representative is preserved by allowing them to make decisions based on his or her understanding of the represented’s interests (the trustee conception of representation). The autonomy of those being represented is preserved by having the preferences of the represented influence evaluations of representatives (the delegate conception of representation). Representatives must act in ways that safeguard the capacity of the represented to authorize and to hold their representatives accountable and uphold the capacity of the representative to act independently of the wishes of the represented.

Objective interests are the key for determining whether the autonomy of representative and the autonomy of the represented have been breached. However, Pitkin never adequately specifies how we are to identify constituents’ objective interests. At points, she implies that constituents should have some say in what are their objective interests, but ultimately she merely shifts her focus away from this paradox to the recommendation that representatives should be evaluated on the basis of the reasons they give for disobeying the preferences of their constituents. For Pitkin, assessments about representatives will depend on the issue at hand and the political environment in which a representative acts. To understand the multiple and conflicting standards within the concept of representation is to reveal the futility of holding all representatives to some fixed set of guidelines. In this way, Pitkin concludes that standards for evaluating representatives defy generalizations. Moreover, individuals, especially democratic citizens, are likely to disagree deeply about what representatives should be doing.

Pitkin offers one of the most comprehensive discussions of the concept of political representation, attending to its contradictory character in her The Concept of Representation . This classic discussion of the concept of representation is one of the most influential and oft-cited works in the literature on political representation. (For a discussion of her influence, see Dovi 2016). Adopting a Wittgensteinian approach to language, Pitkin maintains that in order to understand the concept of political representation, one must consider the different ways in which the term is used. Each of these different uses of the term provides a different view of the concept. Pitkin compares the concept of representation to “ a rather complicated, convoluted, three–dimensional structure in the middle of a dark enclosure.” Political theorists provide “flash-bulb photographs of the structure taken from different angles” [1967, 10]. More specifically, political theorists have provided four main views of the concept of representation. Unfortunately, Pitkin never explains how these different views of political representation fit together. At times, she implies that the concept of representation is unified. At other times, she emphasizes the conflicts between these different views, e.g. how descriptive representation is opposed to accountability. Drawing on her flash-bulb metaphor, Pitkin argues that one must know the context in which the concept of representation is placed in order to determine its meaning. For Pitkin, the contemporary usage of the term “representation” can signficantly change its meaning.

For Pitkin, disagreements about representation can be partially reconciled by clarifying which view of representation is being invoked. Pitkin identifies at least four different views of representation: formalistic representation, descriptive representation, symbolic representation, and substantive representation. (For a brief description of each of these views, see chart below.) Each view provides a different approach for examining representation. The different views of representation can also provide different standards for assessing representatives. So disagreements about what representatives ought to be doing are aggravated by the fact that people adopt the wrong view of representation or misapply the standards of representation. Pitkin has in many ways set the terms of contemporary discussions about representation by providing this schematic overview of the concept of political representation.

1. Formalistic Representation : Brief Description . The institutional arrangements that precede and initiate representation. Formal representation has two dimensions: authorization and accountability. Main Research Question . What is the institutional position of a representative? Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . None. ( Authorization ): Brief Description . The means by which a representative obtains his or her standing, status, position or office. Main Research Questions . What is the process by which a representative gains power (e.g., elections) and what are the ways in which a representative can enforce his or her decisions? Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . No standards for assessing how well a representative behaves. One can merely assess whether a representative legitimately holds his or her position. pdf include--> ( Accountability ): Brief Description . The ability of constituents to punish their representative for failing to act in accordance with their wishes (e.g. voting an elected official out of office) or the responsiveness of the representative to the constituents. Main Research Question . What are the sanctioning mechanisms available to constituents? Is the representative responsive towards his or her constituents’ preferences? Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . No standards for assessing how well a representative behaves. One can merely determine whether a representative can be sanctioned or has been responsive.

Brief Description . The ways that a representative “stands for” the represented — that is, the meaning that a representative has for those being represented.

Main Research Question . What kind of response is invoked by the representative in those being represented?

Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . Representatives are assessed by the degree of acceptance that the representative has among the represented.

Brief Description . The extent to which a representative resembles those being represented.

Main Research Question . Does the representative look like, have common interests with, or share certain experiences with the represented?

Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . Assess the representative by the accuracy of the resemblance between the representative and the represented.

Brief Description . The activity of representatives—that is, the actions taken on behalf of, in the interest of, as an agent of, and as a substitute for the represented.

Main Research Question . Does the representative advance the policy preferences that serve the interests of the represented?

Implicit Standards for Evaluating Representatives . Assess a representative by the extent to which policy outcomes advanced by a representative serve “the best interests” of their constituents.

One cannot overestimate the extent to which Pitkin has shaped contemporary understandings of political representation, especially among political scientists. For example, her claim that descriptive representation opposes accountability is often the starting point for contemporary discussions about whether marginalized groups need representatives from their groups.

Similarly, Pitkin’s conclusions about the paradoxical nature of political representation support the tendency among contemporary theorists and political scientists to focus on formal procedures of authorization and accountability (formalistic representation). In particular, there has been a lot of theoretical attention paid to the proper design of representative institutions (e.g. Amy 1996; Barber, 2001; Christiano 1996; Guinier 1994). This focus is certainly understandable, since one way to resolve the disputes about what representatives should be doing is to “let the people decide.” In other words, establishing fair procedures for reconciling conflicts provides democratic citizens one way to settle conflicts about the proper behavior of representatives. In this way, theoretical discussions of political representation tend to depict political representation as primarily a principal-agent relationship. The emphasis on elections also explains why discussions about the concept of political representation frequently collapse into discussions of democracy. Political representation is understood as a way of 1) establishing the legitimacy of democratic institutions and 2) creating institutional incentives for governments to be responsive to citizens.

David Plotke (1997) has noted that this emphasis on mechanisms of authorization and accountability was especially useful in the context of the Cold War. For this understanding of political representation (specifically, its demarcation from participatory democracy) was useful for distinguishing Western democracies from Communist countries. Those political systems that held competitive elections were considered to be democratic (Schumpeter 1976). Plotke questions whether such a distinction continues to be useful. Plotke recommends that we broaden the scope of our understanding of political representation to encompass interest representation and thereby return to debating what is the proper activity of representatives. Plotke’s insight into why traditional understandings of political representation resonated prior to the end of the Cold War suggests that modern understandings of political representation are to some extent contingent on political realities. For this reason, those who attempt to define political representation should recognize how changing political realities can affect contemporary understandings of political representation. Again, following Pitkin, ideas about political representation appear contingent on existing political practices of representation. Our understandings of representation are inextricably shaped by the manner in which people are currently being represented. For an informative discussion of the history of representation, see Monica Brito Vieira and David Runican’s Representation .

As mentioned earlier, theoretical discussions of political representation have focused mainly on the formal procedures of authorization and accountability within nation states, that is, on what Pitkin called formalistic representation. However, such a focus is no longer satisfactory due to international and domestic political transformations. [For an extensive discussion of international and domestic transformations, see Mark Warren and Dario Castioglione (2004).] Increasingly international, transnational and non-governmental actors play an important role in advancing public policies on behalf of democratic citizens—that is, acting as representatives for those citizens. Such actors “speak for,” “act for” and can even “stand for” individuals within a nation-state. It is no longer desirable to limit one’s understanding of political representation to elected officials within the nation-state. After all, increasingly state “contract out” important responsibilities to non-state actors, e.g. environmental regulation. As a result, elected officials do not necessarily possess “the capacity to act,” the capacity that Pitkin uses to identify who is a representative. So, as the powers of nation-state have been disseminated to international and transnational actors, elected representatives are not necessarily the agents who determine how policies are implemented. Given these changes, the traditional focus of political representation, that is, on elections within nation-states, is insufficient for understanding how public policies are being made and implemented. The complexity of modern representative processes and the multiple locations of political power suggest that contemporary notions of accountability are inadequate. Grant and Keohane (2005) have recently updated notions of accountability, suggesting that the scope of political representation needs to be expanded in order to reflect contemporary realities in the international arena. Michael Saward (2009) has proposed an innovative type of criteria that should be used for evaluating non-elective representative claims. John Dryzek and Simon Niemayer (2008) has proposed an alternative conception of representation, what he calls discursive representation, to reflect the fact that transnational actors represent discourses, not real people. By discourses, they mean “a set of categories and concepts embodying specific assumptions, judgments, contentions, dispositions, and capabilities.” The concept of discursive representation can potentially redeem the promise of deliberative democracy when the deliberative participation of all affected by a collective decision is infeasible.

Domestic transformations also reveal the need to update contemporary understandings of political representation. Associational life — social movements, interest groups, and civic associations—is increasingly recognized as important for the survival of representative democracies. The extent to which interest groups write public policies or play a central role in implementing and regulating policies is the extent to which the division between formal and informal representation has been blurred. The fluid relationship between the career paths of formal and informal representatives also suggests that contemporary realities do not justify focusing mainly on formal representatives. Mark Warren’s concept of citizen representatives (2008) opens up a theoretical framework for exploring how citizens represent themselves and serve in representative capacities.

Given these changes, it is necessary to revisit our conceptual understanding of political representation, specifically of democratic representation. For as Jane Mansbridge has recently noted, normative understandings of representation have not kept up with recent empirical research and contemporary democratic practices. In her important article “Rethinking Representation” Mansbridge identifies four forms of representation in modern democracies: promissory, anticipatory, gyroscopic and surrogacy. Promissory representation is a form of representation in which representatives are to be evaluated by the promises they make to constituents during campaigns. Promissory representation strongly resembles Pitkin’s discussion of formalistic representation. For both are primarily concerned with the ways that constituents give their consent to the authority of a representative. Drawing on recent empirical work, Mansbridge argues for the existence of three additional forms of representation. In anticipatory representation, representatives focus on what they think their constituents will reward in the next election and not on what they promised during the campaign of the previous election. Thus, anticipatory representation challenges those who understand accountability as primarily a retrospective activity. In gyroscopic representation, representatives “look within” to derive from their own experience conceptions of interest and principles to serve as a basis for their action. Finally, surrogate representation occurs when a legislator represents constituents outside of their districts. For Mansbridge, each of these different forms of representation generates a different normative criterion by which representatives should be assessed. All four forms of representation, then, are ways that democratic citizens can be legitimately represented within a democratic regime. Yet none of the latter three forms representation operates through the formal mechanisms of authorization and accountability. Recently, Mansbridge (2009) has gone further by suggesting that political science has focused too much on the sanctions model of accountability and that another model, what she calls the selection model, can be more effective at soliciting the desired behavior from representatives. According to Mansbridge, a sanction model of accountability presumes that the representative has different interests from the represented and that the represented should not only monitor but reward the good representative and punish the bad. In contrast, the selection model of accountability presumes that representatives have self-motivated and exogenous reasons for carrying out the represented’s wishes. In this way, Mansbridge broadens our understanding of accountability to allow for good representation to occur outside of formal sanctioning mechanisms.

Mansbridge’s rethinking of the meaning of representation holds an important insight for contemporary discussions of democratic representation. By specifying the different forms of representation within a democratic polity, Mansbridge teaches us that we should refer to the multiple forms of democratic representation. Democratic representation should not be conceived as a monolithic concept. Moreover, what is abundantly clear is that democratic representation should no longer be treated as consisting simply in a relationship between elected officials and constituents within her voting district. Political representation should no longer be understood as a simple principal-agent relationship. Andrew Rehfeld has gone farther, maintaining that political representation should no longer be territorially based. In other words, Rehfeld (2005) argues that constituencies, e.g. electoral districts, should not be constructed based on where citizens live.

Lisa Disch (2011) also complicates our understanding of democratic representation as a principal-agent relationship by uncovering a dilemma that arises between expectations of democratic responsiveness to constituents and recent empirical findings regarding the context dependency of individual constituents’ preferences. In response to this dilemma, Disch proposes a mobilization conception of political representation and develops a systemic understanding of reflexivity as the measure of its legitimacy.

By far, one of the most important shifts in the literature on representation has been the “constructivist turn.” Constructivist approaches to representation emphasize the representative’s role in creating and framing the identities and claims of the represented. Here Michael Saward’s The Representative Claim is exemplary. For Saward, representation entails a series of relationships: “A maker of representations (M) puts forward a subject (S) which stands for an object (O) which is related to a referent (R) and is offered to an audience (A)” (2006, 302). Instead of presuming a pre-existing set of interests of the represented that representatives “bring into” the political arena, Saward stresses how representative claim-making is a “deeply culturally inflected practice.” Saward explicitly denies that theorists can know what are the interests of the represented. For this reason, the represented should have the ultimate say in judging the claims of the representative. The task of the representative is to create claims that will resonate with appropriate audiences.

Saward therefore does not evaluate representatives by the extent to which they advance the preferences or interests of the represented. Instead he focuses on the institutional and collective conditions in which claim-making takes place. The constructivist turn examines the conditions for claim-making, not the activities of particular representatives.

Saward’s “constructivist turn” has generated a new research direction for both political theorists and empirical scientists. For example, Lisa Disch (2015) considers whether the constructivist turn is a “normative dead” end, that is, whether the epistemological commitments of constructivism that deny the ability to identify interests will undermine the normative commitments to democratic politics. Disch offers an alternative approach, what she calls “the citizen standpoint”. This standpoint does not mean taking at face value whomever or whatever citizens regard as representing them. Rather, it is “an epistemological and political achievement that does not exist spontaneously but develops out of the activism of political movements together with the critical theories and transformative empirical research to which they give rise” (2015, 493). (For other critical engagements with Saward’s work, see Schaap et al, 2012 and Nässtrom, 2011).

There have been a number of important advances in theorizing the concept of political representation. In particular, these advances call into question the traditional way of thinking of political representation as a principal-agent relationship. Most notably, Melissa Williams’ recent work has recommended reenvisioning the activity of representation in light of the experiences of historically disadvantaged groups. In particular, she recommends understanding representation as “mediation.” In particular, Williams (1998, 8) identifies three different dimensions of political life that representatives must “mediate:” the dynamics of legislative decision-making, the nature of legislator-constituent relations, and the basis for aggregating citizens into representable constituencies. She explains each aspect by using a corresponding theme (voice, trust, and memory) and by drawing on the experiences of marginalized groups in the United States. For example, drawing on the experiences of American women trying to gain equal citizenship, Williams argues that historically disadvantaged groups need a “voice” in legislative decision-making. The “heavily deliberative” quality of legislative institutions requires the presence of individuals who have direct access to historically excluded perspectives.

In addition, Williams explains how representatives need to mediate the representative-constituent relationship in order to build “trust.” For Williams, trust is the cornerstone for democratic accountability. Relying on the experiences of African-Americans, Williams shows the consistent patterns of betrayal of African-Americans by privileged white citizens that give them good reason for distrusting white representatives and the institutions themselves. For Williams, relationships of distrust can be “at least partially mended if the disadvantaged group is represented by its own members”(1998, 14). Finally, representation involves mediating how groups are defined. The boundaries of groups according to Williams are partially established by past experiences — what Williams calls “memory.” Having certain shared patterns of marginalization justifies certain institutional mechanisms to guarantee presence.

Williams offers her understanding of representation as mediation as a supplement to what she regards as the traditional conception of liberal representation. Williams identifies two strands in liberal representation. The first strand she describes as the “ideal of fair representation as an outcome of free and open elections in which every citizen has an equally weighted vote” (1998, 57). The second strand is interest-group pluralism, which Williams describes as the “theory of the organization of shared social interests with the purpose of securing the equitable representation … of those groups in public policies” ( ibid .). Together, the two strands provide a coherent approach for achieving fair representation, but the traditional conception of liberal representation as made up of simply these two strands is inadequate. In particular, Williams criticizes the traditional conception of liberal representation for failing to take into account the injustices experienced by marginalized groups in the United States. Thus, Williams expands accounts of political representation beyond the question of institutional design and thus, in effect, challenges those who understand representation as simply a matter of formal procedures of authorization and accountability.

Another way of reenvisioning representation was offered by Nadia Urbinati (2000, 2002). Urbinati argues for understanding representation as advocacy. For Urbinati, the point of representation should not be the aggregation of interests, but the preservation of disagreements necessary for preserving liberty. Urbinati identifies two main features of advocacy: 1) the representative’s passionate link to the electors’ cause and 2) the representative’s relative autonomy of judgment. Urbinati emphasizes the importance of the former for motivating representatives to deliberate with each other and their constituents. For Urbinati the benefit of conceptualizing representation as advocacy is that it improves our understanding of deliberative democracy. In particular, it avoids a common mistake made by many contemporary deliberative democrats: focusing on the formal procedures of deliberation at the expense of examining the sources of inequality within civil society, e.g. the family. One benefit of Urbinati’s understanding of representation is its emphasis on the importance of opinion and consent formation. In particular, her agonistic conception of representation highlights the importance of disagreements and rhetoric to the procedures, practices, and ethos of democracy. Her account expands the scope of theoretical discussions of representation away from formal procedures of authorization to the deliberative and expressive dimensions of representative institutions. In this way, her agonistic understanding of representation provides a theoretical tool to those who wish to explain how non-state actors “represent.”

Other conceptual advancements have helped clarify the meaning of particular aspects of representation. For instance, Andrew Rehfeld (2009) has argued that we need to disaggregate the delegate/trustee distinction. Rehfeld highlights how representatives can be delegates and trustees in at least three different ways. For this reason, we should replace the traditional delegate/trustee distinction with three distinctions (aims, source of judgment, and responsiveness). By collapsing these three different ways of being delegates and trustees, political theorists and political scientists overlook the ways in which representatives are often partial delegates and partial trustees.

Other political theorists have asked us to rethink central aspects of our understanding of democratic representation. In Inclusion and Democracy Iris Marion Young asks us to rethink the importance of descriptive representation. Young stresses that attempts to include more voices in the political arena can suppress other voices. She illustrates this point using the example of a Latino representative who might inadvertently represent straight Latinos at the expense of gay and lesbian Latinos (1986, 350). For Young, the suppression of differences is a problem for all representation (1986, 351). Representatives of large districts or of small communities must negotiate the difficulty of one person representing many. Because such a difficulty is constitutive of representation, it is unreasonable to assume that representation should be characterized by a “relationship of identity.” The legitimacy of a representative is not primarily a function of his or her similarities to the represented. For Young, the representative should not be treated as a substitute for the represented. Consequently, Young recommends reconceptualizing representation as a differentiated relationship (2000, 125–127; 1986, 357). There are two main benefits of Young’s understanding of representation. First, her understanding of representation encourages us to recognize the diversity of those being represented. Second, her analysis of representation emphasizes the importance of recognizing how representative institutions include as well as they exclude. Democratic citizens need to remain vigilant about the ways in which providing representation for some groups comes at the expense of excluding others. Building on Young’s insight, Suzanne Dovi (2009) has argued that we should not conceptualize representation simply in terms of how we bring marginalized groups into democratic politics; rather, democratic representation can require limiting the influence of overrepresented privileged groups.

Moreover, based on this way of understanding political representation, Young provides an alterative account of democratic representation. Specifically, she envisions democratic representation as a dynamic process, one that moves between moments of authorization and moments of accountability (2000, 129). It is the movement between these moments that makes the process “democratic.” This fluidity allows citizens to authorize their representatives and for traces of that authorization to be evident in what the representatives do and how representatives are held accountable. The appropriateness of any given representative is therefore partially dependent on future behavior as well as on his or her past relationships. For this reason, Young maintains that evaluation of this process must be continuously “deferred.” We must assess representation dynamically, that is, assess the whole ongoing processes of authorization and accountability of representatives. Young’s discussion of the dynamic of representation emphasizes the ways in which evaluations of representatives are incomplete, needing to incorporate the extent to which democratic citizens need to suspend their evaluations of representatives and the extent to which representatives can face unanticipated issues.

Another insight about democratic representation that comes from the literature on descriptive representation is the importance of contingencies. Here the work of Jane Mansbridge on descriptive representation has been particularly influential. Mansbridge recommends that we evaluate descriptive representatives by contexts and certain functions. More specifically, Mansbridge (1999, 628) focuses on four functions and their related contexts in which disadvantaged groups would want to be represented by someone who belongs to their group. Those four functions are “(1) adequate communication in contexts of mistrust, (2) innovative thinking in contexts of uncrystallized, not fully articulated, interests, … (3) creating a social meaning of ‘ability to rule’ for members of a group in historical contexts where the ability has been seriously questioned and (4) increasing the polity’s de facto legitimacy in contexts of past discrimination.” For Mansbridge, descriptive representatives are needed when marginalized groups distrust members of relatively more privileged groups and when marginalized groups possess political preferences that have not been fully formed. The need for descriptive representation is contingent on certain functions.

Mansbridge’s insight about the contingency of descriptive representation suggests that at some point descriptive representatives might not be necessary. However, she doesn’t specify how we are to know if interests have become crystallized or trust has formed to the point that the need for descriptive representation would be obsolete. Thus, Mansbridge’s discussion of descriptive representation suggests that standards for evaluating representatives are fluid and flexible. For an interesting discussion of the problems with unified or fixed standards for evaluating Latino representatives, see Christina Beltran’s The Trouble with Unity .

Mansbridge’s discussion of descriptive representation points to another trend within the literature on political representation — namely, the trend to derive normative accounts of representation from the representative’s function. Russell Hardin (2004) captured this trend most clearly in his position that “if we wish to assess the morality of elected officials, we must understand their function as our representatives and then infer how they can fulfill this function.” For Hardin, only an empirical explanation of the role of a representative is necessary for determining what a representative should be doing. Following Hardin, Suzanne Dovi (2007) identifies three democratic standards for evaluating the performance of representatives: those of fair-mindedness, critical trust building, and good gate-keeping. In Ruling Passions , Andrew Sabl (2002) links the proper behavior of representatives to their particular office. In particular, Sabl focuses on three offices: senator, organizer and activist. He argues that the same standards should not be used to evaluate these different offices. Rather, each office is responsible for promoting democratic constancy, what Sabl understands as “the effective pursuit of interest.” Sabl (2002) and Hardin (2004) exemplify the trend to tie the standards for evaluating political representatives to the activity and office of those representatives.

There are three persistent problems associated with political representation. Each of these problems identifies a future area of investigation. The first problem is the proper institutional design for representative institutions within democratic polities. The theoretical literature on political representation has paid a lot of attention to the institutional design of democracies. More specifically, political theorists have recommended everything from proportional representation (e.g. Guinier, 1994 and Christiano, 1996) to citizen juries (Fishkin, 1995). However, with the growing number of democratic states, we are likely to witness more variation among the different forms of political representation. In particular, it is important to be aware of how non-democratic and hybrid regimes can adopt representative institutions to consolidate their power over their citizens. There is likely to be much debate about the advantages and disadvantages of adopting representative institutions.

This leads to a second future line of inquiry — ways in which democratic citizens can be marginalized by representative institutions. This problem is articulated most clearly by Young’s discussion of the difficulties arising from one person representing many. Young suggests that representative institutions can include the opinions, perspectives and interests of some citizens at the expense of marginalizing the opinions, perspectives and interests of others. Hence, a problem with institutional reforms aimed at increasing the representation of historically disadvantaged groups is that such reforms can and often do decrease the responsiveness of representatives. For instance, the creation of black districts has created safe zones for black elected officials so that they are less accountable to their constituents. Any decrease in accountability is especially worrisome given the ways citizens are vulnerable to their representatives. Thus, one future line of research is examining the ways that representative institutions marginalize the interests, opinions and perspectives of democratic citizens.

In particular, it is necessary for to acknowledge the biases of representative institutions. While E. E. Schattschneider (1960) has long noted the class bias of representative institutions, there is little discussion of how to improve the political representation of the disaffected — that is, the political representation of those citizens who do not have the will, the time, or political resources to participate in politics. The absence of such a discussion is particularly apparent in the literature on descriptive representation, the area that is most concerned with disadvantaged citizens. Anne Phillips (1995) raises the problems with the representation of the poor, e.g. the inability to define class, however, she argues for issues of class to be integrated into a politics of presence. Few theorists have taken up Phillip’s gauntlet and articulated how this integration of class and a politics of presence is to be done. Of course, some have recognized the ways in which interest groups, associations, and individual representatives can betray the least well off (e.g. Strolovitch, 2004). And some (Dovi, 2003) have argued that descriptive representatives need to be selected based on their relationship to citizens who have been unjustly excluded and marginalized by democratic politics. However, it is unclear how to counteract the class bias that pervades domestic and international representative institutions. It is necessary to specify the conditions under which certain groups within a democratic polity require enhanced representation. Recent empirical literature has suggested that the benefits of having descriptive representatives is by no means straightforward (Gay, 2002).

A third and final area of research involves the relationship between representation and democracy. Historically, representation was considered to be in opposition with democracy [See Dahl (1989) for a historical overview of the concept of representation]. When compared to the direct forms of democracy found in the ancient city-states, notably Athens, representative institutions appear to be poor substitutes for the ways that citizens actively ruled themselves. Barber (1984) has famously argued that representative institutions were opposed to strong democracy. In contrast, almost everyone now agrees that democratic political institutions are representative ones.

Bernard Manin (1997)reminds us that the Athenian Assembly, which often exemplifies direct forms of democracy, had only limited powers. According to Manin, the practice of selecting magistrates by lottery is what separates representative democracies from so-called direct democracies. Consequently, Manin argues that the methods of selecting public officials are crucial to understanding what makes representative governments democratic. He identifies four principles distinctive of representative government: 1) Those who govern are appointed by election at regular intervals; 2) The decision-making of those who govern retains a degree of independence from the wishes of the electorate; 3) Those who are governed may give expression to their opinions and political wishes without these being subject to the control of those who govern; and 4) Public decisions undergo the trial of debate (6). For Manin, historical democratic practices hold important lessons for determining whether representative institutions are democratic.

While it is clear that representative institutions are vital institutional components of democratic institutions, much more needs to be said about the meaning of democratic representation. In particular, it is important not to presume that all acts of representation are equally democratic. After all, not all acts of representation within a representative democracy are necessarily instances of democratic representation. Henry Richardson (2002) has explored the undemocratic ways that members of the bureaucracy can represent citizens. [For a more detailed discussion of non-democratic forms of representation, see Apter (1968). Michael Saward (2008) also discusses how existing systems of political representation do not necessarily serve democracy.] Similarly, it is unclear whether a representative who actively seeks to dismantle democratic institutions is representing democratically. Does democratic representation require representatives to advance the preferences of democratic citizens or does it require a commitment to democratic institutions? At this point, answers to such questions are unclear. What is certain is that democratic citizens are likely to disagree about what constitutes democratic representation.